What pregnant women are taking: learning from a survey in the Canton of Zurich

Eliane Randecker, Giulia Gantner, Deborah Spiess, Katharina C. Quack Lötscher, Ana Paula Simões-Wüst

During pregnancy, the benefits and risks of medication intake should be particularly carefully weighed up in view of the concomitant exposure of the woman and her unborn child. Possible negative outcomes for the fetus – be they restricted intrauterine development or teratogenicity – should always be considered. The same caution applies to the physiological and biochemical changes that progressively occur in the mother in the gastrointestinal, hepatic, renal, pulmonary and cardiovascular systems. These changes markedly affect pharmacokinetic processes such as absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination of various substances [1]. Despite this complexity and the obvious limitations on clinical research during pregnancy, the number of published studies has increased over the past few years. Currently, the necessity to translate available evidence on pharmacological treatments into recommendations for practice coexists with a strong need for additional research.

In Switzerland, several organisations are engaged in instructing healthcare professionals on prenatal care. The Swiss Academy of Perinatal Pharmacology has organised workshops for health professionals and edited monographs on medication use and substance abuse during pregnancy (SAPP). The Swiss Teratogen Information Service (STIS) has clarified questions on aspects of teratogenicity and contributed to various national and international research projects. The Swiss Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics published recommendations for preconception counselling in 2010, which include suggestions to replace possibly teratogenic medication with less hazardous alternatives, and to stop using alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs [2]. To our knowledge – and at least in the German-speaking part of Switzerland – the website www.embryotox.de/ is often used for counselling.

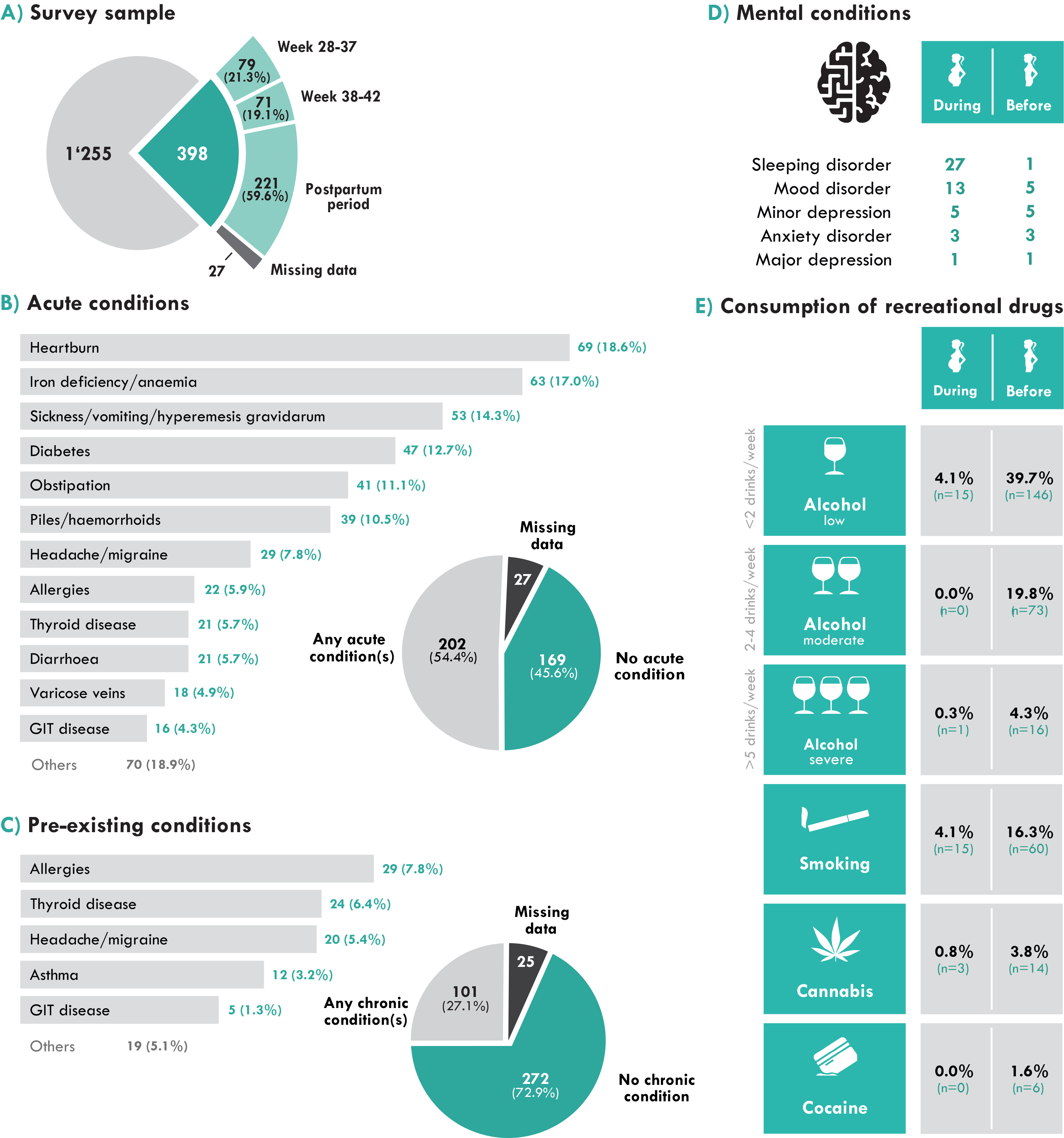

To better inform ongoing efforts, it is important to have an overview of the current habits and needs of pregnant women. We therefore describe here what we learned about health status and use of medication during pregnancy from a group of obstetric patients surveyed between August 2018 and March 2019. The survey was carried out in the Canton of Zurich, whose inhabitants represent one sixth of the entire Swiss population and are often taken as representative of the entire Swiss population with respect to health outcomes. A total of 1653 envelopes – each containing an information sheet, the questionnaire and a post-paid return envelope – were handed out to potential participants in obstetric clinics and birthing centres in the entire canton. Ward clerks, midwives, nursing staff and/or treating obstetricians/gynaecologists were instructed by the study team to distribute the envelopes to patients. Pregnant women or women soon after giving birth were invited to participate in the survey if they were able to read and write German, English, French or Italian and were not in a gestation week earlier than the 28th week. Of the 1653 questionnaires handed out to potential participants, 398 were completed, returned either by post or via collecting boxes in the various institutions and included in the present analysis (see fig. 1A). More than 90% of the questionnaires were completed in German. Most of the women who participated in the survey were between 33 and 37 years old, married, born in Switzerland, employed and had attended a higher professional school or university.

To put our results on medication use in context, participants were asked about current and pre-existing organic and mental conditions or disorders and a few items also dealt with recreational drug intake. As illustrated in figure 1B, the large majority of women had one or more conditions during pregnancy and a wide variety of current organic conditions were named. Heartburn, iron deficiency / anaemia, morning sickness, diabetes, obstipation and piles/haemorrhoids were the most common ones. Other acute conditions mentioned were headache/migraine, allergies, thyroid disease, diarrhoea, varicose veins, gastrointestinal disease, high blood pressure, low blood pressure, urinary tract infection and asthma, as well as single cases of epilepsy, cancer, heart disease, rheumatic disease and kidney disease. Moreover, one quarter of the participants reported pre-existing chronic medical conditions (fig. 1C). In most cases, these were allergies, thyroid disease and headache/migraine, asthma and gastrointestinal disease, but diabetes, epilepsy, cancer, high blood pressure and low blood pressure were also mentioned. Mental conditions were also specifically addressed in the questionnaire, with items including sleep disorders, mood disorders, minor and major depression and anxiety disorders (fig. 1D). Forty-nine women, (12.3% of the participants) reported having at least one of these conditions. The prevalence of all mental conditions during the current pregnancy was therefore comparable to the 16.7% annual rate of mental health care use by perinatal women in Switzerland [3]. Fewer women reported suffering from a mental condition before the current pregnancy. Only a few women stated that they drank alcohol or smoked tobacco or cannabis during pregnancy, though many more had done so before (fig. 1E). The observed numbers are lower than those obtained in previous studies in Switzerland, suggesting an increased awareness in society of the risks of recreational drug consumption during pregnancy [4–6]. This can be seen as positive feedback for the counselling and public health work conducted so far, but the fact that some pregnant women still consume recreational drugs shows that additional efforts are needed.

Figure 1: Health status of survey participants. (A) Characterisation of study sample by circumstances of filling in the questionnaire; (B) acute conditions; (C) pre-existing conditions; (D) mental conditions during and before pregnancy; (E) recreational drug consumption during and before pregnancy. GIT = gastrointestinal tract

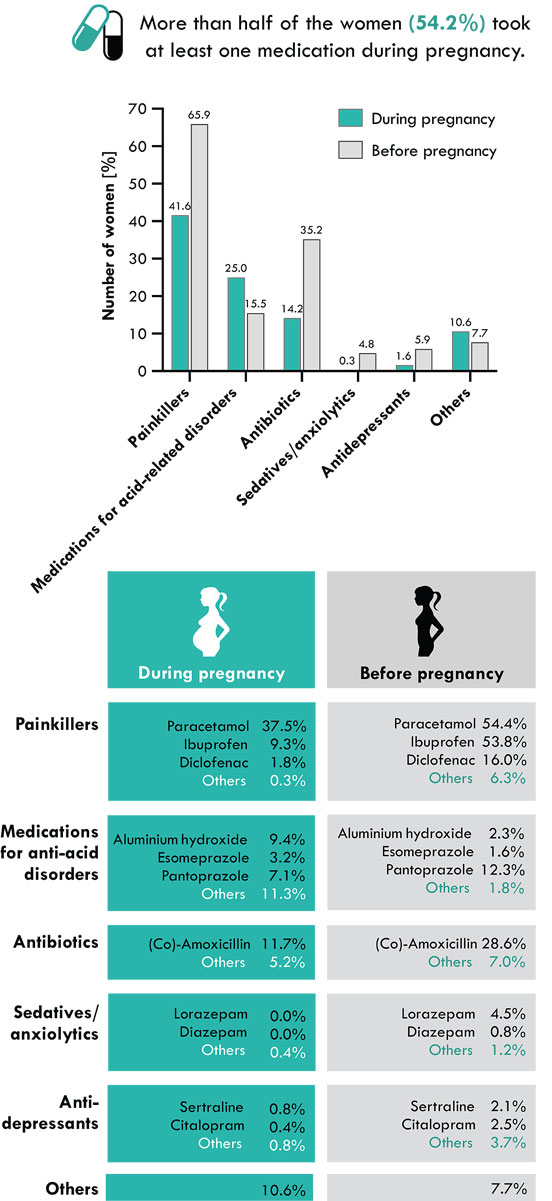

To characterise medication use, participants were asked whether they had taken well-known medications from various medication classes, but they were also able to name additional medication classes and specific medicines. The results show that more than half of the women (54.2%) took at least one medication during pregnancy. This prevalence is comparable to the present medication intake figures for the general population in Switzerland [7], but lower than, for instance, the 73.4% recently reported in the US [8]. It is worth taking a closer look at the classes of the most frequently consumed medications (fig. 2). Painkillers were the most frequently taken type of medication during pregnancy, although their use before pregnancy was even higher. Such an intake reduction suggests that the women tried to refrain from using painkillers upon conception, and is consistent with results of the Swiss Health Surveys from 2007 and 2012 [5]. Paracetamol was the most commonly used painkiller during pregnancy, followed by ibuprofen and diclofenac, which have in addition anti-inflammatory effects. Whereas paracetamol is mentioned in the recommendations of the seven main Swiss perinatal centres for all trimesters, ibuprofen should be avoided during the last trimester and diclofenac is not recommended in the Swiss main perinatal centres. It is worrying that some participants might have taken a painkiller/anti-inflammatory agent that is not recommended, even though there are alternatives.

Figure 2: Medication consumption by survey participants during pregnancy and in the time before.

As is to be expected from the high prevalence of heartburn during pregnancy, medication against acid-related disorders were commonly used. Most of the available medications are efficacious and can be considered harmless during pregnancy. Perhaps for these reasons, a wide range of substances were used. In addition to aluminium hydroxide, esomeprazole and pantoprazole, which were named in the questionnaire, following substances were mentioned: calcium/magnesium carbonate, magaldrate, a combination of sodium alginate, sodium hydrogen carbonate and calcium carbonate, ranitidine (a product withdrawn from sale since 2019), omeprazole and healing earth.

Antibiotics were used at least once during their current pregnancy by 14.2% of the women. The most frequently used antibiotic was amoxicillin (alone or in combination with clavulanic acid), in accordance with existing recommendations for treatment of bacterial infections during pregnancy [9]. In this context, it is important to mention that infections during pregnancy can have serious negative consequences. At the same time, the ongoing efforts – including from the World Health Organization – to restrict the use of antibiotics for bacterial infections, thereby reducing the spread of bacterial resistance, are also pertinent during pregnancy.

Psychoactive medications were also taken by some women during the current pregnancy, which is consistent with findings of the Swiss health surveys from 2007 and 2012 [5]. Comparison with use before the current pregnancy suggests that respondents attenuated or stopped mental disease treatment upon conception. This was true for depression inasmuch as almost four times fewer women reported taking antidepressants during the current pregnancy than before it (5 vs 19). It was also true for sleep problems and anxiety, since no woman took sedatives/anxiolytics during pregnancy, whereas 15 women took these medications before conception. Comparison of the number of pregnant women taking psychoactive medications was compared with the number of women affected by mental disorders, either pre-existing (minor depression, n = 5; mood disorder, n = 5; anxiety disorder, n = 3; major depression, n = 1; sleep disorder, n = 1) or current (sleeping disorder, n = 27; mood disorder n = 13; minor depression, n = 5; anxiety disorder, n = 3; major depression, n = 1) revealed striking differences. Pregnant women seem to avoid taking psychoactive medications. Whether they are relying on additional therapies (e.g., herbal preparations, therapies or counselling) that are often perceived as being safe, the impact of accepting the risks of facing these conditions without treatment or even underreporting psychoactive medication use is unknown and deserves further investigation.

In addition to painkillers/analgesics, medications for acid-related disorders, antibiotics, sedatives/anxiolytics and antidepressants, some participants (10.6%) reported using one or more of (an) additional medicine class(es). Their enumeration reveals the diversity of medications consumed during pregnancy, although their further characterisation would require surveys with higher participant numbers. The medications not shown in figure 2 comprise: hormones, iron supplements, magnesium salts, tocolytics (nifedipine and hexoprenaline), antiemetics (pyridoxine and metoclopramide), insulin, antiasthmatics (budesonide/formoterol), antiplatelet drugs (low dose acetylsalicylic acid, certainly to prevent pregnancy-induced hypertension and pre-eclampsia), cholecalciferol (vitamin D3), progesterone, ursodeoxycholic acid (likely as a treatment for obstetric cholestasis), the anticoagulant heparin (dalteparin), antifibrinolytic (tranexamic acid), antiflatulent (simeticone), antimycotic (fluconazole) and a tumour necrosis factor-alpha-inhibitor (adalimumab).

The high prevalence of conditions or disorders among the pregnant women who participated in the survey revealed a strong demand for appropriate treatments. This is corroborated by the data showing that more than half the women took at least one medication during pregnancy. The variety of conditions and disorders, as well as of medications, reported by the participants illustrates the difficulties arising in daily clinical practice to find the most effective and safest treatments for each case. Whereas some medications may harm the unborn child, insufficient or no treatment of some medical conditions can also negatively impact the health status of the pregnant woman (and therefore her child). Thus, avoiding medications cannot be seen as a feasible alternative to the use of partially harmful medications. Although the level of evidence for several pharmacological treatments during pregnancy is still low, the number of studies is increasing and, in some cases, updated recommendations for treatment during pregnancy are available. A recent comparison of the recommendations developed at the main Swiss obstetric centres revealed a considerable overlap, pointing to a possible national harmonisation [9]. In our opinion, such a harmonisation accompanied by an intensification of research efforts is urgently needed.

Acknowledgments

Most participants were being treated at the University Hospital Zurich, City Hospital Triemli, Hospital Zollikerberg, Hospital Bülach, Paracelsus-Hospital Richterswil, Hospital Limmattal and Delphys Birthing Centre: we thank all professionals who authorised and/or facilitated the distribution of the questionnaires. We are also indebted to all women who filled in the questionnaires and therefore made this survey possible. This survey was initiated to characterise the use of herbal preparations during pregnancy as part of the Swiss National Science Foundation Sinergia project CRSII5_177260; we gratefully acknowledge the SNF for its support. APSW participates in the SAPP steering committee as an observer and thanks the other steering committee members for interesting discussions.

DS contributed to this project while being financially supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Sinergia project CRSII5_177260). No additional funding sources. No conflict of interest declared.

Eliane Randecker, Department of Obstetrics, University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland

Giulia Gantner, Department of Obstetrics, University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland

Deborah Spiess, Department of Obstetrics, University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland

Katharina C. Quack Lötscher, Department of Obstetrics, University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland

Ana Paula Simões-Wüst, Department of Obstetrics, University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland

anapaula.simoes-wuest[at]usz.ch

References

- Schaefer C, Peters PW, Miller RK. Drugs during pregnancy and lactation: treatment options and risk assessment. 3rd edition. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; 2014.

- Bürki RE, Drack G, Hagmann D, Hösli I, Seydoux J, Surbek D. SGGG Expertenbrief No 33 - Aktuelle Empfehlungen zur Präkonzeptionsberatung (14 November 2017). Available from: www.sggg.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/Dokumente/3_Fachinformationen/1_Expertenbriefe/De/33_Praekonzeptionsberatung_2010.pdf2010

- Berger A, Bachmann N, Signorell A, Erdin R, Oelhafen S, Reich O, et al. Perinatal mental disorders in Switzerland: prevalence estimates and use of mental-health services. Swiss Med Wkly. 2017;147:w14417. doi:https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2017.14417. PubMed

- Dupraz J, Graff V, Barasche J, Etter JF, Boulvain M. Tobacco and alcohol during pregnancy: prevalence and determinants in Geneva in 2008. Swiss Med Wkly. 2013;143:w13795. doi:https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2013.13795. PubMed

- Bornhauser C, Quack Lötscher K, Seifert B, Simões-Wüst AP. Diet, medication use and drug intake during pregnancy: data from the consecutive Swiss Health Surveys of 2007 and 2012. Swiss Med Wkly. 2017;147:w14572. PubMed

- Dupraz J, Graff V, Barasche J, Etter J-F, Boulvain M. Tobacco and alcohol during pregnancy: prevalence and determinants in Geneva in 2008. Swiss Med Wkly. 2013;143:w13795. doi:https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2013.13795. PubMed

- Federal Statistics Office. [Swiss Health Survey] Schweizerische Gesundheitsbefragung. 2017. Available from: www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/gesundheit/erhebungen/sgb.html.

- Haas DM, Marsh DJ, Dang DT, Parker CB, Wing DA, Simhan HN, et al. Prescription and Other Medication Use in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(5):789–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002579. PubMed

- Schenkel L, Simões-Wüst AP, Hösli I, von Mandach U. Medikamente in Schwangerschaft und Stillzeit – In den Schweizer Perinatalzentren verwendete Medikamente [Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation - Medications Used in Swiss Obstetrics]. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2018;222(04):152–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-124975. PubMed