Endocrine care of transgender and gender-diverse adults: Swiss recommendations

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/5059

Hüseyin Cihanabc,

Barbara Bischofberger-Baumannd,

Julie Buchere,

Verdiana Caironif,

Fabien Claudeg,

Federico del Ventoh,

Michelle Egloffi,

Niklaus Flütschj,

David Garcia Nuñezc,

Ursula Gobrecht-Kellerk,

Ulrike Itenl,

Martine Jacot-Guillarmodm,

Johannes Kliebhanbc,

Maddalena Masciocchik,

Maria Mavromatin,

Christian Meierb,

Georgios

E. Papadakiso,

Carole Riebene,

Lea Slahorj,

Lorenzo Soldatip,

Maria-Isabelle Streuliq,

Sébastien Thalmannr,

Vincent Vibertp,

Bettina Winzelercs

a Faculty of Medicine,

Zurich University, Zurich, Switzerland

b Department of Endocrinology,

Basel University Hospital, Basel, Switzerland

c Innovation-Focus Gender Variance, Basel

University Hospital, Basel, Switzerland

d Department of Endocrinology, HOCH Health

Ostschweiz, St. Gallen, Switzerland

e EndoDia Centre, Biel, Switzerland

f Department of Endocrinology, Regional

Hospital of Bellinzona and Valli, Bellinzona, Switzerland

g Department of Paediatric Endocrinology,

University Children’s Hospital Basel (UKBB), Basel, Switzerland

h Department of Gynaecology, Geneva

University Hospitals (HUG), Geneva, Switzerland

i Department of Endocrinology, Cantonal

Hospital Baden, Baden, Switzerland

j Department of Endocrinology and

Diabetology, Cantonal Hospital Lucerne, Lucerne, Switzerland

k Department of Reproductive Medicine and

Gynaecological Endocrinology, University Hospital Basel, Basel, Switzerland

l Swiss Society for Endocrinology and

Diabetology (SGED), Baden, Switzerland

m Department of Gynaecology, Lausanne

University Hospital (CHUV), Lausanne, Switzerland

n Department of Endocrinology, Geneva

University Hospitals (HUG), Geneva, Switzerland

o Department of Endocrinology, Diabetology

and Metabolism, Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), Lausanne, Switzerland

p Department of Psychiatry, Geneva

University Hospitals (HUG), Geneva, Switzerland

q Department of Reproductive Medicine and

Gynaecological Endocrinology, Geneva University Hospitals (HUG), Geneva,

Switzerland

r Ärztezentrum Sihlcity, Zurich, Switzerland

s Department of Endocrinology, Zurich

University Hospital, Zurich, Switzerland

Summary

Transgender and gender-diverse

individuals require standardised, evidence-based and culturally sensitive

endocrine care. International guidelines such as

those from the World Professional Association for Transgender

Health

(WPATH) and the Endocrine Society provide a strong foundation. These Swiss recommendations

build on them and offer

context-specific recommendations adapted to Switzerland’s healthcare system, insurance

policies and social considerations.

These recommendations

were developed by the “Working Group Transgender” of the Swiss Society of Endocrinology

and Diabetology (SSED/SGED) in collaboration with multidisciplinary experts. They

primarily focus on gender-affirming hormone therapy, including indications,

monitoring and long-term management. They also address fertility preservation, bone

and sexual health, and relevant psychological and legal aspects.

Interdisciplinary collaboration

among endocrinologists, primary care providers, mental health professionals, reproductive

specialists and surgeons is recommended to ensure cohesive patient-centred care.

Introduction

Transgender and gender-diverse

individuals are those whose gender identity does not align with sex assigned

at birth. For example, transfeminine individuals were assigned male at birth and

transmasculine individuals were assigned female at birth [1, 2].

For many transgender and gender-diverse individuals,

medical transition is an important aspect of aligning their physical characteristics

with their gender identity. Medical transition commonly involves gender-affirming

hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgeries, both of which have

been demonstrated to significantly improve psychological and physical health outcomes

[1, 3, 4]. Two diagnostic terms are used: International Classification of Diseases,

11th Revision (ICD-11) “gender incongruence”, which describes incongruence

between gender identity and sex assigned at birth and includes the desire to undergo

treatment as part of the diagnosis while Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) “gender dysphoria” describes distress

or impairment associated with this incongruence [5–7].

Health systems-based

studies estimate the prevalence of gender incongruence at 0.02–0.1%, while survey-based

studies report 0.3–4.5% [8]. In the 2023 IPSOS survey across 30 countries, the average

proportion of individuals self-identifying as transgender, non-binary, gender non-conforming,

gender-fluid or other gender identities was 3%, with Switzerland having one of the

highest rates at 6% [9]. The growing visibility of transgender and gender-diverse

people has been accompanied by an increasing

demand for equitable, high-quality healthcare. While international

guidelines such as the Standards of Care, Version 8 (SOC 8) from the World Professional

Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) and the Endocrine Society’s “Gender Incongruence

Guideline” offer an evidence-based framework for care, adaptations are required

to account for Switzerland’s healthcare organisation, insurance regulations, legal

gender recognition processes and access to specific medications. The purpose of

this document is to equip healthcare professionals in Switzerland with useful

and practical guidance for transgender care. It integrates international best practices

with Swiss-specific clinical realities, legal frameworks and sociopolitical contexts.

Methods

The “Working Group Transgender” of the Swiss Society of Endocrinology

and Diabetology (SSED/SGED), composed of Swiss endocrinologists with expertise in

transgender

health, developed these recommendations in collaboration with invited multidisciplinary

guest authors. To establish evidence-based recommendations, the authors reviewed

relevant scientific literature, national resources and international guidelines.

Each contributor drafted one or more chapters within their area of expertise, which

were then reviewed by at least one other expert from a different institution or

geographical region.

Following this peer-review

process, members of the editorial board (ME, LS, ST, BW) revised each chapter to

ensure accuracy, consistency and clarity. The complete draft was then circulated

among all contributing authors for critical appraisal and feedback. Revisions were

made iteratively until consensus was achieved. The final version underwent internal

peer review by the SSED/SGED executive committee.

The full recommendations are available on the SSED/SGED website.

Clear terminology in

transgender and gender-diverse healthcare supports respectful and accurate description

of diverse gender identities

[10]. A glossary of terms

to aid clinical communication is provided in table 1.

Table 1Definitions of key terms for clinical communication in gender-affirming care.

| Sex |

Term relating to biological characteristics (i.e.

chromosomes, genitals, hormones) |

| Gender |

Term relating to personal, social and cultural

concepts |

| Sex assigned at birth |

Categorisation at birth, mostly based on phenotypic

presentation (i.e. genitals) |

| Transgender |

Gender identity does not correspond to sex assigned at birth |

| Cisgender |

Gender identity corresponds to sex assigned at

birth |

| Non-binary |

Gender identity outside binary categorisation of women and men |

| Gender-diverse |

Gender identity not constrained by binary concept of

gender |

| Gender-fluid |

Gender identity that is not fixed to a specific

gender and may change over time |

| Gender incongruence |

Marked and persistent incongruence between a person’s

experienced gender and that assigned at birth |

| Gender dysphoria |

Distress caused by gender incongruence |

| Transfeminine |

Feminine identity of someone who was assigned male

at birth. This includes

trans women and other gender identities |

| Transmasculine |

Masculine identity of someone who was assigned

female at birth. This

includes trans men and other gender identities |

A clinical checklist

summarising all key recommendations is provided at the end of the article to facilitate

implementation

in clinical practice.

Diagnosis, mental health and transition support

According

to the World Professional Association for Transgender Health’s SOC 8, healthcare

professionals experienced in transgender medicine may assess adults for gender-affirming

hormone therapy if they can identify co-existing mental health or psychosocial issues,

assess capacity to consent, evaluate clinical aspects of gender dysphoria and engage

in ongoing education. Diagnosis of gender incongruence is based on clinical history,

as no psychometric, laboratory or imaging methods exist for this purpose. Gender-affirming

hormone therapy can be indicated when there is a marked and sustained experience

of incongruence. Gender-affirming hormone therapy repeatedly demonstrated a decrease

in depressive symptoms and psychological discomfort [1]. Medical or psychosocial

conditions that could impact gender-affirming hormone therapy outcomes and the individual’s

expectations must be identified and addressed. The SSED/SGED working group recommends

that an assessment by a mental health professional experienced in gender incongruence

be offered to all individuals before gender-affirming hormone therapy. This evaluation

can help explore personal resources, identify mental health comorbidities and, if

desired, initiate longer-term support. It is particularly recommended in cases of

diagnostic uncertainty where incongruence may be primarily due to underlying psychopathology

rather than a transgender identity per se. Once the diagnosis is established, an

individual medical transition plan is created through shared decision-making [11,

12].

Because the transition process affects core physical, psychological and social factors,

support by a professional experienced in gender incongruence should be offered.

Innovative approaches, such as advanced practice nurse-supported models, can facilitate

coordination among specialists and help adapt the transition plan without pressure

from the medical system [13].

Legal aspects

Since

January 2022, individuals aged over 16 years in Switzerland can legally register

a change of recorded gender and first name by self-declaration at the civil registry

office without medical or psychological assessments [14]. The register

allows only male or female entries. A male gender entry before age 24 requires assessment

by the military medical service to determine compulsory military service eligibility,

considering transition stage and comorbidities [15]. Under the

informed consent model, transgender and gender-diverse individuals can start gender-affirming

therapies without

mandatory psychological evaluation, though such evaluations may

still be recommended.

Costs for medical and surgical procedures are covered by Swiss health insurance

regardless of civil register gender status. Transgender and gender-diverse individuals

are protected from workplace

discrimination under the Swiss gender equality act [16]. While using

correct names, pronouns and appropriate facilities is strongly recommended in schools

and workplaces, no specific anti-discrimination law for transgender and gender-diverse

individuals exists as

of 2025.

Gender-affirming hormone therapy

Indications and general principles of gender-affirming

hormone therapy

The primary indication for gender-affirming

hormone therapy is a diagnosis of gender incongruence. By suppressing endogenous

sex hormones and administering gender-affirming hormones, gender-affirming

hormone therapy supports aligning physical characteristics with gender identity. Gender-affirming

hormone therapy has demonstrated safety and efficacy to achieve desired physical

changes and to reduce gender incongruence for transgender and gender-diverse individuals

in short- and medium-term

follow-up studies [3].

Baseline assessment includes a discussion of expected

physical changes, potential irreversible effects and possible adverse effects. Counselling

on the impact of gender-affirming hormone therapy on fertility, as well as fertility

preservation options, is essential prior to initiation. Table 2 outlines the recommended

assessments at baseline and during follow-up. In the first year, clinical evaluations

are advised every three months, followed by monitoring every 6–12 months. This includes

assessment of body weight, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, cardiovascular

risk and laboratory parameters such as hormone levels, glucose, HbA1c, and renal

and liver function [8, 17].

Table 2Overview of recommended clinical, laboratory and psychosocial evaluations

prior to and during gender-affirming hormone therapy.

| Baseline |

Discuss

expectations from gender-affirming hormone therapy |

| Explain

onset and time course of physical changes including irreversible effects as

well as side effects |

| Provide counselling

for impact on fertility and fertility-preservation options |

| Assess

psychosocial setting and resources |

| Check

relative contraindication (i.e. thromboembolic disease, hormone-sensitive

cancer and for transmasculine individuals erythrocytosis and obstructive

sleep apnoea syndrome) |

| Clinical

evaluation, i.e. measure body weight, BMI, blood pressure; smoking cessation

counselling |

| Laboratory

evaluation: sex hormones, liver and renal parameters, lipids, glucose/HbA1c,

blood count, 25-OH-vitamin D |

| Every 3

months for the 1st year, then every 6–12 months |

Clinical

evaluation to monitor signs of feminisation/virilisation and

undesired/adverse effects |

| Monitor

cardiovascular risk factors such as body weight, body mass

index (BMI), blood pressure; smoking

cessation counselling |

| Laboratory evaluation: sex hormones, liver and renal parameters, lipids,

glucose/HbA1c, blood count |

As gender-affirming hormone therapy represents a

lifelong treatment for most individuals, long-term follow-up is essential. Satisfaction

with therapy should be evaluated continuously through shared decision-making, respecting

patient autonomy and individual preferences.

Feminising hormone therapy

Feminising

hormone therapy aims to suppress endogenous testosterone and induce feminisation.

Therapy uses 17β-oestradiol, usually combined with an anti-androgen [8, 17].

Ethinyl oestradiol and conjugated equine oestrogens are not recommended due to higher

thromboembolism risk (table 3). Clinicians review relative contraindications like

thromboembolic disease, liver dysfunction and hormone-sensitive malignancies before

initiation.

Table 3Summary of oestradiol options used

in feminising hormone regimens, with their pharmacological characteristics.

| Route of administration |

Active ingredient |

Formulation |

Main characteristics |

| Transdermal |

Oestradiol (Estradot®) |

Transdermal patch: 50–300

µg every 72 hours |

Slow

release; oestradiol values stable; avoids first-pass effect; ↓ thrombotic

risk compared to oral oestradiol; half-life 24 hours |

| Oestradiol hemihydricum

(Oestrogel®) |

Transdermal gel: 0.75–3

mg/day (= 1–6 pushes/day) |

| Oral |

Oestradiol valerate

(Progynova®, Estrofem®) |

Oestradiol tablets: 2–6

mg/day |

Accumulation of oestrone as

first-pass effect; fluctuation of plasma levels; half-life 12 hours |

| Parenteral |

Oestradiol valerate or

cypionate |

Not available in

Switzerland |

Transdermal

oestradiol via patches or gels is preferred due to a better thromboembolic risk

profile compared to oral forms [8, 18, 19]. However oral oestradiol remains an option

especially for younger individuals (<45 years) without cardiovascular risks. Parenteral

oestradiol is not available in Switzerland.

Anti-androgens

are generally used in combination with oestradiol, as monotherapy rarely suppresses

testosterone sufficiently [18]. Available agents in Switzerland include

cyproterone acetate, spironolactone and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)

analogues (table 4). Cyproterone acetate is effective but linked to hyperprolactinaemia,

hepatotoxicity and increased meningioma risk with cumulative doses above 10 grams

[20].

Spironolactone blocks androgen receptors and may reduce testosterone synthesis but

can cause hyperkalaemia, especially in older adults or those with renal impairment

[21].

GnRH analogues provide potent suppression but are limited

by cost and need for bone health monitoring. Current guidelines do not give a clear

preference for any of the three options [22].

Table 4Description of available

anti-androgens used to suppress testosterone production in feminising therapy.

| Route of administration |

Active substance |

Dose |

Main characteristics |

Side effects |

| Oral

|

Cyproterone acetate

(Androcur®) |

Approximately 10 mg/day (no

benefit with higher doses); 1/4 of 50 mg every day or every other day if 10 mg

tablets not available |

Hepatic metabolism; half-life 48–72

hours |

Negative effects on lipid

profile, weight; Increase in prolactin values; Increased incidence of

meningiomas |

| Spironolactone (Aldactone®) |

Tablets: 100–300 mg/day |

Hepatic metabolism; half-life 16–22

hours |

Hyperkalaemia (greater in patients >45 years old/with specific risk

factors; dehydration; hyponatraemia |

| Parenteral

|

GnRH agonist: triptorelin (Pamorelin LA®) or leuprolide (Lucrin®) |

3.75 mg/monthly s.c.

injection: 11.25 mg/ every 3 months s.c. injection |

Hepatic metabolism;

half-life 3 hours |

|

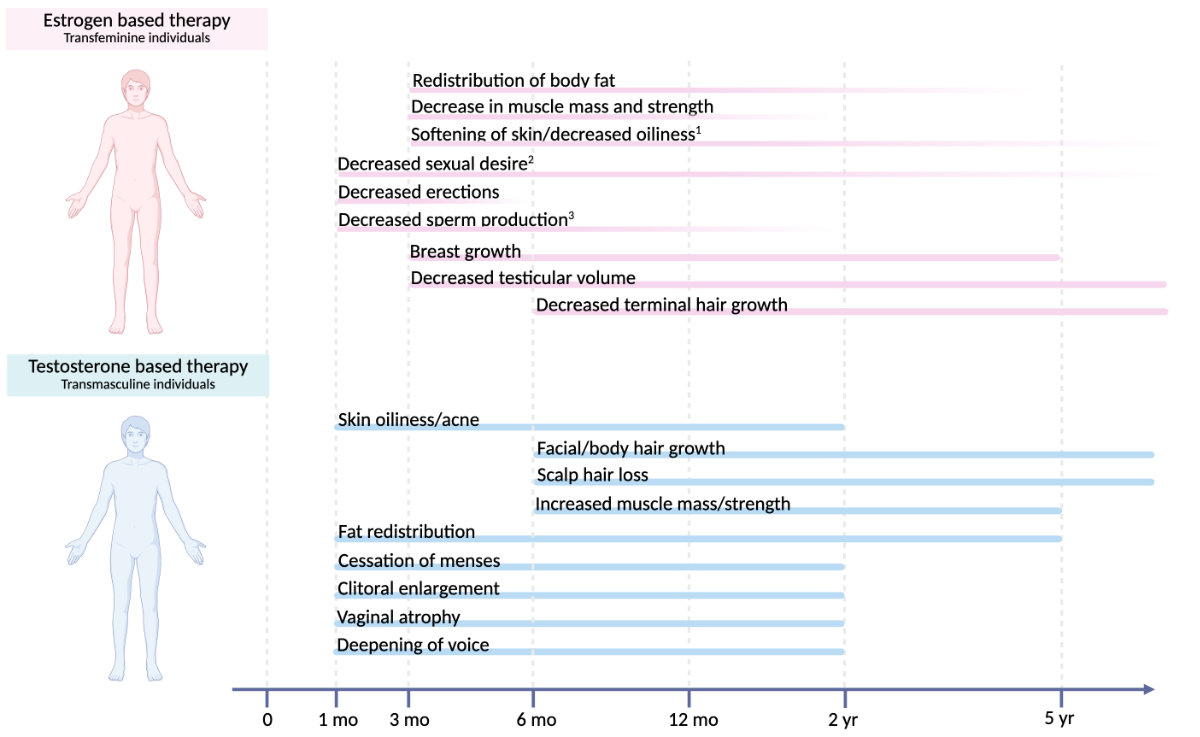

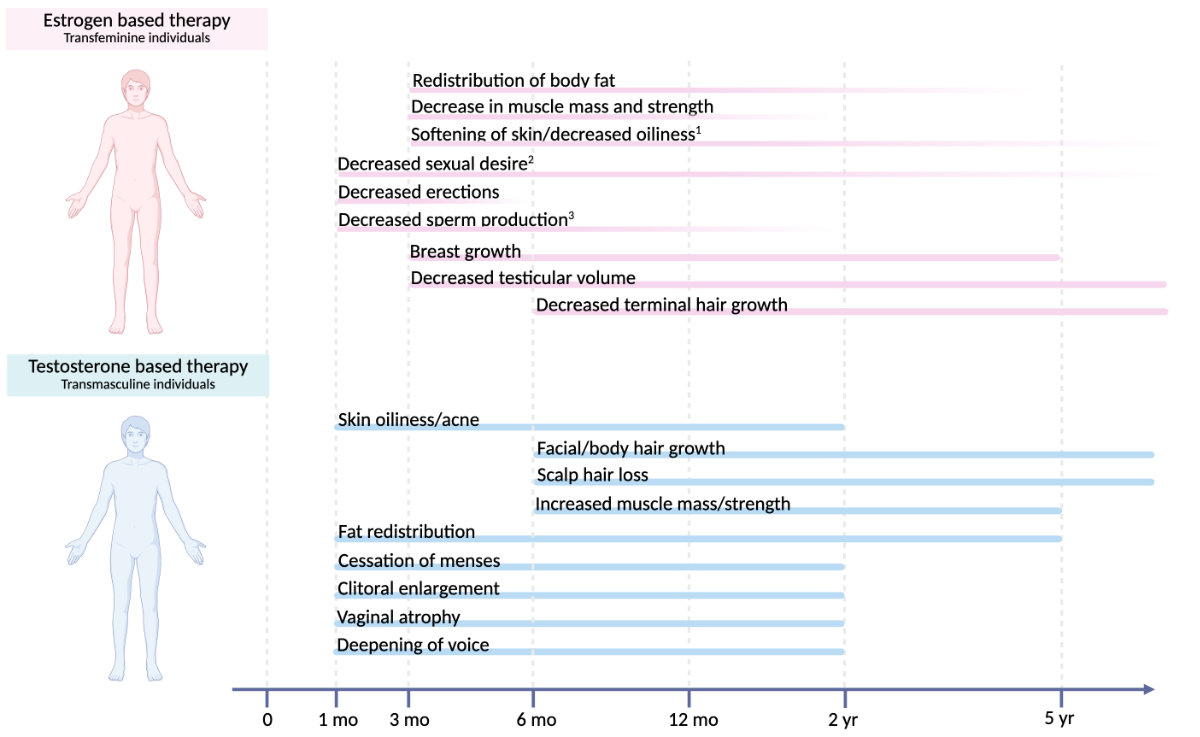

Figure 1Time course of physical changes

in gender-affirming hormone therapy. Estimated onset and time to maximum effect

of common physical changes induced by oestrogen-based therapy in transfeminine individuals

and testosterone-based therapy in transmasculine individuals, showing considerable

interindividual variability (1 maximum effect is unknown, 2 onset is unknown, 3 maximum effect is

variable). Created with BioRender.com.

Follow-up

is essential and includes key parameters such as cardiovascular risk factors, sex

hormones, blood count, and liver and renal function tests. Target serum testosterone

levels are usually below 2 nmol/l, and oestradiol levels between 370–730 pmol/l.

Importantly, laboratory values are used as a guide during treatment, but the goal

is not to reach specific targets; rather, clinical wellbeing and desired physical

changes are prioritised. Feminising effects typically start within 3–6 months, with

maximal changes over 2–5 years (figure 1). Effects include breast development, fat

redistribution, decreased erections, softer skin, and reduced facial and body hair,

which often requires additional measures like laser or electrolysis. Degree and

rate of change vary depending on age, genetic predisposition and adherence. Bone

health surveillance is important, especially on GnRH analogues

or in individuals who stop oestrogen after gonadectomy.

Masculinising hormone therapy

The

approach of masculinising hormone therapy parallels treatment for hypogonadal cisgender

men and includes injectable and transdermal preparations [17, 23, 24].

Testosterone enanthate subcutaneously (monthly) or undecanoate intramuscularly (every

three months) are common regimens, though

intervals vary with individual response. Transdermal preparations like testosterone

gel are other options (table 5) [25, 26].

Table 5Commonly used testosterone

preparations for masculinising hormone therapy.

| Testosterone |

Dose |

| Parenteral |

Testosterone

enanthate (Testoviron®) |

125–250 mg

i.m. every 3–4 weeks |

| Testosterone

undecanoate (Nebido®) |

500–1000 mg

i.m. every 8–14 weeks, then according to plasma testosterone levels |

| Transdermal |

Testosterone

gel (Testogel®, Tostran®) |

10–80 mg

testosterone/day |

Pre-therapy

evaluation should assess cardiovascular risk, haematological parameters, sleep apnoea

and liver function [8]. While testosterone alone is usually sufficient

to suppress ovulation and menstrual cycles, it does not provide contraception, so

counselling is essential.

Physiological

effects begin within 1–6 months and continue over years, including increased lean

mass, decreased fat mass, voice deepening, clitoromegaly, increased hair growth,

cessation of menses and skin changes (figure 1) [17, 27, 28].

About 10% may continue uterine bleeding, and benefit from progestogens or GnRH analogues

in case of distress associated with gender incongruence [28, 29].

Serum

testosterone is monitored every 3 months during titration: for enanthate, mid-cycle

levels should be 14–24 nmol/l; for undecanoate, levels assessed at the end of the

interval <14 nmol/l may indicate a need for interval adjustment; for transdermal

therapy, levels obtained ≥2 hours post-application after ≥1 week of use should demonstrate

stable physiological concentrations. Follow-up also includes haematocrit, lipid

profile, liver enzymes and renal function; see table 3. Haematocrit >0.50–0.54 may

indicate erythrocytosis, an adverse effect which may occur in approximately 11%

[8, 17,

23].

Other

potential adverse effects include hypertension, dyslipidaemia or liver enzyme elevations.

Bone health surveillance is important, especially on GnRH analogues or in individuals

who stop testosterone after gonadectomy [30–33].

Therapy of non-binary people

No

standardised gender-affirming hormone therapy protocols exist specifically for non-binary

individuals. Clinical principles from binary transition can be adapted, recognising

that non-binary people may seek only partial feminisation or masculinisation based

on their goals. Individualised plans may include oestradiol alone or in combination

with low-dose androgen blockers for partial feminisation, and low-dose testosterone

for partial masculinisation. Sometimes suppression of the

menstrual cycle (e.g. with oral, subcutaneous or intrauterine progestogens) may

be sufficient. These approaches aim to achieve specific effects

like breast development, voice deepening or amenorrhoea while avoiding undesired

changes.

Due

to lack of long-term outcome data, therapy should use shared decision-making with

thorough counselling on expected changes, fertility and health risks [8].

Minimal exposure to endogenous or exogenous sex hormones is needed to support bone

and cardiovascular health, maintaining hormone levels at least within the lower

physiological range for cisgender individuals [34].

Fertility protection

Gender-affirming hormone therapy affects fertility; it is therefore strongly

recommended to discuss the topic of fertility preservation early and before initiating

gender-affirming hormone therapy, and to generously refer patients to fertility

preservation experts if indicated [35–37].

In transfeminine individuals, oestrogens and antiandrogens often reduce

spermatogenesis or cause azoospermia, though recovery may occur after stopping therapy

[38]. Standard preservation involves sperm cryopreservation

via masturbation, or testicular sperm extraction if needed [39].

In transmasculine individuals, testosterone and/or GnRH analogues typically induce

anovulation and amenorrhoea. Ovarian function

may return after discontinuation [40]. Fertility

options include spontaneous conception after gender-affirming hormone therapy discontinuation,

oocyte or embryo cryopreservation, and third-party reproduction (surrogate). Cryopreservation

procedures require ovarian stimulation and retrieval, which may be psychologically

distressing and provoke distress related to gender incongruence [41]. Data from transgender

individuals with ovaries

who have used testosterone suggest that testosterone use does not significantly

impact oocyte retrieval, follicular function or oocyte maturation. Notably, the duration

of testosterone use did not correlate with

mature oocyte outcomes [42]. Adnexectomy leads

to irreversible loss of ovarian function, so ovarian tissue cryopreservation before

surgery may be considered [43].

Despite comparable parenthood desires to cisgender individuals, uptake

of fertility preservation is low [35, 36, 44].

Barriers include high costs (not covered by basic health insurance), lack of legal

frameworks and insufficient information.

Long-term management and special populations

Long-term risks of gender-affirming hormone

therapy and cancer screening

Gender-affirming hormone therapy is typically lifelong and generally safe

when properly monitored. However, long-term effects on somatic health and cancer

risk remain under study. No consistent evidence shows gender-affirming hormone

therapy increases overall mortality. Higher morbidity and mortality rates, including

high rates of suicide and homicide, may largely reflect psychosocial factors such

as minority stress, limited access to care and mental health issues. Cause-related

mortality from lung cancer, cardiovascular disease, HIV and suicide does not show

a direct link to hormone therapy, but it does highlight the need to monitor and

manage comorbidities and lifestyle factors [45, 46].

Cancer screening should follow local guidelines based on anatomy and hormone exposure.

In Switzerland, national screening guidelines for breast and cervical cancer are

applicable to all individuals having a uterus or mammary glands, regardless of gender

identity or gender-affirming hormone therapy use. For breast cancer, data suggest

no increased incidence in transfeminine individuals compared to cisgender populations,

though prospective studies are limited. Transfeminine individuals and transmasculine

individuals with retained breast tissue should follow cisgender women’s screening.

After chest masculinisation surgery (mastectomy), annual chest wall exams are recommended

[8, 47]. Cervical cancer screening applies to all transgender and gender-diverse

individuals with a cervix via Pap smear per cisgender women intervals: every three

years from ages 21 to 70, or human papilloma virus (HPV) testing starting at 30

years [48].

For transfeminine individuals on long-term oestrogen, prostate cancer risk

is low but present, and screening should be individualised [49–51]. As shown in table

6, routine screening should

align with general population practices, with attention to individual risks related

to hormones, age and comorbidities.

Table 6Suggested screening procedures

based on present anatomy and hormone exposure in individuals receiving gender-affirming

hormone therapy.

| Screening |

Transfeminine individuals |

Transmasculine individuals |

| Cardiovascular disease |

Screening for risk factors |

Screening for risk factors |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 |

Screening according to cis individuals |

Screening according to cis individuals |

| Dyslipidaemia |

Annual screening |

Annual screening |

| Breast cancer |

Screening according to cis women |

Screening according to cis women in individuals

with breasts not having gender-affirming chest surgery.

After mastectomy: annual sub- and periareolar breast examinations. |

| Cervical cancer |

Not applicable |

Screening according to cis women in sexually

active individuals if cervical tissue is present. |

| Prostate cancer |

Screening according to cis men |

Not applicable |

Cardiovascular health and health risk behaviours

Transgender and gender-diverse individuals are at elevated risk of cardiovascular

disease. A recent meta-analysis of 10 studies (15,781 trans women and 11,304 trans

men) showed a 40% higher risk for major cardiovascular

events in transgender and gender-diverse individuals compared with individuals of

the same birth sex [52]. This increased

risk appears to be multifactorial. While the contribution of gender-affirming

hormone therapy remains uncertain, it intersects with minority stress, lifestyle

behaviours and classic cardiovascular risk factors.

Masculinising therapy is linked to lower HDL and higher

LDL cholesterol and triglycerides. Blood pressure may rise with testosterone, though

findings are inconsistent.

Feminising therapy has variable effects on lipids and blood pressure depending on

the agents used (e.g. cyproterone acetate vs spironolactone), often modestly reducing

LDL cholesterol at the beginning [53, 54].

Important contributing behavioural factors are higher rates of tobacco

use, physical inactivity and obesity. Lifestyle counselling is therefore important,

including encouraging people to quit smoking and engage in regular physical activity

[55–57].

Bone health

Both medical and surgical gender-affirming interventions can influence

bone health [58]. Bone mineral density (BMD) might

be assessed using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) prior to gender-affirming

hormone therapy in individuals at risk particularly in transfeminine individuals,

where studies suggest up to 30% may have low bone mineral density at baseline [59].

Further indications for dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry include planned

gonadectomy without gender-affirming hormone therapy, long-term suppression of endogenous

sex hormones (e.g. via GnRH analogues) and poor adherence

to gender-affirming hormone therapy. The 2019 ISCD Position Paper advises that

z-scores for transgender individuals should be calculated using reference data (mean

and standard deviation) matched to the individual’s affirmed gender [60].

Despite methodological limitations, existing studies indicate that gender-affirming

hormone therapy has a neutral effect on bone mineral density in transmasculine individuals

and may slightly improve bone mineral density at the lumbar spine in transfeminine

individuals [61–63]. In addition, lifestyle counselling

to support bone health should include adequate calcium and vitamin D intake and

weight-bearing exercise, though long-term studies are needed to determine their

impact on fracture risk [64].

The management of osteoporosis diagnosed in transgender and gender-diverse individuals

follows clinical

guidelines that apply to the general population [65, 66].

Treatment of older or medically complex individuals

In

older individuals and those with a history of complex or severe concomitant diseases,

close surveillance of hormonal therapy is essential (table 7). Age is not a contraindication

for initiation of gender-affirming hormone therapy. While studies on gender-affirming

hormone therapy in older trans individuals are limited, evidence suggests that transitioning

improves quality of life in this population [67].

Table 7Recommended modifications of

hormone therapy in the presence of older age, impaired organ function or

elevated cardiovascular and thromboembolic risk.

| Condition |

Masculinising

hormone therapy |

Feminising

hormone therapy |

| Older age; andro-/Menopause |

Monitor for cardiovascular risk factors (see section

“Cardiovascular

health and health risk behaviours”). Monitor for

osteoporosis (see section “Bone health”). Consider dose reduction analogous

cis-individuals. |

Transdermal oestradiol (>45 years). Monitor electrolytes/kidney function with

spironolactone use. Monitor for cardiovascular risk factors (see section

“Cardiovascular

health and health risk behaviours”). Monitor for osteoporosis (see section “Bone health”).

Consider dose reduction analogous cis-individuals |

| Severe liver disease |

Consider dose reduction/adjustment. Consider

estimating free testosterone for therapy guidance |

No

oral oestradiol or cyproterone acetate. No

dose adjustment. |

| Severe kidney disease (eGFR

<30 ml/min) |

Consider measuring free testosterone for therapy guidance

|

Avoid spironolactone. Decrease dose of oestradiol in end-stage renal

disease (eGFR <15 ml/min) |

| Risk factors for venous thromboembolism |

No

dose adjustment. |

Switch to transdermal oestradiol. Avoid cyproterone acetate. Avoid supraphysiological

oestradiol levels. Consider haematology referral. |

| Breast

cancer |

Conflicting

data. Consider stop due to possible aromatisation to oestradiol. Shared decision-making

person/gynaecologic-oncologist. |

Withhold

therapy, refer for shared decision-making with person/gynaecologic oncologist. If

therapy is continued, aim for lowest possible dose of oestradiol. |

| High cardiovascular risk |

Continuation seems safe; see section “Cardiovascular health

and health risk behaviours” |

Switch to transdermal oestradiol oestrogen. See section “Cardiovascular health and

health

risk behaviours”. |

Similar

to physiological changes in cis individuals, a reduction in gender-affirming

hormone therapy dosage may be considered [1].

There are no specific guidelines for discontinuing gender-affirming hormone

therapy at any specific age. In the absence of research evidence, a shared decision-making

approach is recommended to achieve individual goals while minimising potential adverse

effects. Given that approximately 50% of testosterone is metabolised by the liver,

dose reduction should be considered in individuals with severe liver conditions.

Oral forms of testosterone and oestrogen are not recommended. Chronic kidney disease

is associated with mild hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, so a mild dose reduction

might be indicated in cases of severe kidney disease [68].

Comprehensive multidisciplinary care

Collaboration with other disciplines

Successful gender-affirming care relies on ongoing interdisciplinary dialogue

and patient-centred coordination to optimise health outcomes and improve quality

of life [69]. While endocrinologists, gynaecologists

and mental health specialists are typically involved early in the transition process,

many other disciplines contribute to comprehensive care. Dermatologists provide

treatment for unwanted facial and body hair, often through laser or electrolysis,

and also address acne and other hormone-related skin changes [70]. Speech therapists

support transgender and gender-diverse individuals in voice

modification and communication style alignment, working on pitch, resonance and

expression early in transition. Surgeons specialising in maxillofacial, plastic

and reconstructive procedures play a central role in delivering gender-affirming

surgical interventions [8].

In the following sections, we will expand on key aspects of gender-affirming

care, including sexual health, gender-affirming surgery and the importance of collaboration

with paediatric teams to support young adults as they transition to adult care.

Sexual health including sexually transmitted infections

Gender-affirming therapies can profoundly impact sexual health. Before

gender-affirming hormone therapy or surgery, many transgender and gender-diverse individuals

report a negative body image, which may limit their sexual satisfaction. While transition

can improve this, surgeries

may cause loss of erogenous zones and sensory changes affecting pleasure [8, 71, 72].

Providers should engage in patient-centred

discussions about expectations and potential sexual side effects, covering anatomical,

physiological and psychosocial aspects. Counselling and sex therapy can help manage

distress or dysfunction. Pharmacological options like phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors

for erectile dysfunction, topical oestrogen for vaginal dryness or low-dose testosterone

for low sexual desire disorders may support sexual functioning [73, 74].

Routine genital examinations may be distressing and are not necessary unless

there is evidence-based screening [75]. STI screening

is based on personalised risk evaluation, considering sexual practices, anatomy

and behaviours, rather than identity labels. HIV, Chlamydia trachomatis,

Neisseria gonorrhoeae, hepatitis B/C and syphilis are some of the most important

infections to check for [76]. Chlamydia screening

is not routine but may be indicated for sexually active adolescents or symptomatic

individuals. Vaginal self-sampling is preferred while urine testing is less sensitive

and specific. Screening in individuals with neovaginas is questionable, as infections

seem rare. In such cases, anorectal swabs or first-catch morning urine are more reliable

[77, 78].

The Safer Sex Check

tool is a valuable aid to personalised risk assessment and can be consulted in complete

confidentiality [79]. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with emtricitabine/tenofovir

disoproxil (Truvada®)

has been available since 2016 in Switzerland for individuals at high HIV risk and

is relevant in sexually active transgender and gender-diverse populations [80].

Contraceptive counselling is important for all transgender and gender-diverse individuals

engaging

in sexual relations at risk of pregnancy. Of note, testosterone does not reliably

prevent ovulation. No contraceptive method is contraindicated in people undergoing

masculinising hormone therapy as a result of this treatment [81, 82].

Gender-affirming surgery

Gender-affirming surgery is an important part of medical transition for

many transgender and gender-diverse individuals. Endocrinologists involved in gender-affirming

hormone

therapy should be familiar with common procedures and participate in presurgical

assessment and perioperative planning. Gender-affirming surgery varies by gender

identity and may include breast augmentation, facial feminisation, chondrolaryngoplasty,

vocal cord surgery, vaginoplasty or vulvoplasty for transfeminine individuals, and

chest reconstruction, phalloplasty, metoidioplasty or hysterectomy/oophorectomy

for transmasculine individuals [8].

A confirmed diagnosis of persistent, well-documented gender incongruence/dysphoria

is generally required

by health insurance companies, supported by psychiatric and/or endocrinological

reports. Informed shared decision-making is essential and preoperative hormone therapy

is not generally mandatory for surgery, but it may be needed or beneficial for certain

procedures [8, 83].

Preoperative assessments include comorbidities, cardiovascular and cancer

risks, and mental health evaluation. Fertility preservation must be addressed before

gonadectomy if not previously discussed. Surgeon selection is important, with recommended

criteria including experience in transgender and gender-diverse specific procedures,

supervised training and

continuing education.

Perioperative continuation of gender-affirming hormone therapy is generally

safe and does not significantly increase venous thromboembolism risk, though caution

is advised in older or high-risk individuals [84, 85].

Postoperative hormone therapy is needed after gonad removal to prevent hypogonadism

and long-term complications like cardiovascular disease or osteoporosis [47, 86].

Transition from adolescent to adult care

Transitioning transgender and gender-diverse individuals to adult care requires early,

structured

planning, ideally starting ≥2 years before transfer. Multidisciplinary follow-up

during adolescence and joint visits with adult providers help prevent treatment

gaps, especially in those with psychosocial or psychiatric comorbidities [8, 17].

Puberty blockers (GnRH agonists) may be offered to transgender and gender-diverse

adolescents after starting puberty (i.e.

at least Tanner stage 2); gender-affirming hormone therapy may be started later

during adolescence (around age 14–16 or later), and evaluation of indication and

follow-up by a specialised interdisciplinary team of at least paediatric endocrinologists

and mental health specialists are recommended. Fertility

counselling should be offered to all patients. However, genital surgery should be

postponed until the age of majority. Interdisciplinary management must be continued

into adulthood in a process known as “transition”. The transition process concludes

with the transfer of patient care from a specialised team for adolescents to one

for adults. The transition process must be individualised and lead to patient empowerment,

involving both patients and their relatives [87, 88].

Insurance coverage of gender-affirming hormone therapy

In Switzerland, gender-affirming hormone therapy is considered medically

necessary for individuals diagnosed with gender dysphoria and is covered by basic

health insurance.

Coverage includes consultations, medications, follow-up evaluations and laboratory

monitoring [89].

Reimbursement requires that treatment meets criteria for medical necessity

and effectiveness: (1) a medically relevant condition, (2) provision by certified

providers within Switzerland, (3) absence of explicit exclusion from insurance coverage

by legal regulation, and (4) the intervention being efficient and cost-effective [90].

Although coverage is standardised, some insurers may impose additional

requirements not permitted under Swiss law, such as “everyday life tests”, mandatory

sequencing of steps, minimum age limits, prior psychiatric treatments or exclusion

of non-binary individuals [91, 92].

Gender-affirming hormone therapy medications are typically prescribed off-label,

as none currently has formal approval for this indication [93]. Medications on the

official specialty list are

reimbursed without prior authorisation. When off-list or imported medications are

used, such as transdermal testosterone products, some insurers may ask for justification

and it is recommended to confirm reimbursement eligibility in advance [94].

Knowledge gaps and future directions

Additional research is needed to strengthen the evidence base for transgender

healthcare. Main areas include investigating the long-term effects of gender-affirming

hormone therapy on bone density, cardiometabolic health and fertility. Similarly,

more focus needs to be placed on documenting individuals who are ageing and nonbinary,

as well as those who have stopped or paused hormone therapy. The effect of medical

transition on quality of life and other outcomes in patients is also underexplored.

To address these knowledge gaps and advance evidence-based care, Switzerland

would benefit from the establishment of a national data collection infrastructure,

ideally through multicentre cohorts and long-term registries. This method would

allow for systematic surveillance of health outcomes, promote high-quality research

and form a base for clinical guidelines. Collaboration among healthcare providers,

academic institutions, professional organisations and patient advocacy groups will

be needed to promote knowledge exchange and ensure that emerging evidence is rapidly

translated into clinical practice.

Equally important is the integration of transgender health education into

medical school curricula and postgraduate training programmes. Currently, most healthcare

professionals in Switzerland receive little or no formal training in this area.

Improving education would enhance the competence of providers and contribute to

a more equitable and inclusive healthcare system for transgender and gender-diverse

individuals.

Checklist

These recommendations have been created to

provide transgender and gender-diverse people with safe, evidence-based and

affirming care. Every person’s goals, health needs and circumstances should be

taken into consideration when creating a plan for therapy. Flexibility, respect

for autonomy, and shared decision-making are essential.

Communication

- Use clear, affirming

language in all interactions.

- Record and use preferred names and pronouns.

Mental

health

- Offer a mental

health assessment before initiating hormone therapy.

- Explore coping

strategies, resilience and any support needs.

Fertility

preservation

- Discuss fertility

impact of hormone therapy and surgery before starting gender-affirming hormone

therapy and gender-affirming surgeries.

- Review sperm, egg,

embryo or gonadal tissue preservation options.

- If interest shown, refer

promptly to reproductive specialists.

Baseline

evaluation before hormone therapy

- Record weight,

height, BMI and vital signs.

- Perform baseline

labs: hormone levels (oestradiol, testosterone, LH, FSH); full blood count; lipids,

glucose and HbA1c; liver and renal function; electrolytes (especially if considering

spironolactone)

- Review medical

history for cardiovascular risk factors and relative contraindications.

- Advise about weight control

and smoking cessation, if applicable.

- Discuss expected

physical changes, timelines, reversibility and risks.

- Clarify

contraception needs and options (testosterone is not a contraceptive).

Hormone

therapy initiation and regimen

- Tailor dosing to

individual goals, risks and preferences.

- Transfeminine

patients: Prefer transdermal oestradiol if higher clot risk.

- Avoid ethinyl oestradiol

and conjugated oestrogens.

- Oestrogen therapy combined

with antiandrogen (cyproterone, spironolactone or GnRH analogues).

- Transmasculine

patients: Intramuscular or transdermal testosterone regimen based on the patient.

- Discuss menstrual

suppression options if desired.

Non-binary

care considerations

- Offer standard care

or low-dose or partial hormone regimens as appropriate.

- Clearly explain

expected effects and uncertainties.

- Monitor bone health

if prolonged hypogonadism occurs.

Follow-up

monitoring

- Schedule follow-up

visits: every 3 months during the first year; every 6–12 months thereafter.

- At each visit: review goals and satisfaction; measure weight, BMI and blood pressure;

discuss lifestyle behaviours including smoking, nutrition, physical activity; check

hormone levels to confirm targets; monitor lipids, glucose, liver and renal function;

assess for side effects (e.g. erythrocytosis, hyperkalaemia, thromboembolism); adjust

dosing based

on labs and clinical response.

Cancer

screening and preventive care

- Schedule cancer

screening based on retained organs: Breast: follow cis female guidelines if breast

tissue present. Cervix: Pap smears per guideline if cervix present. Prostate: individualise

screening in transfeminine patients.

- Discuss STI

screening tailored to sexual behaviour, not identity labels.

- Offer HIV PrEP if

indicated.

- Provide smoking

cessation counselling if applicable.

Older

or medically complex patients

- Use lower hormone

doses and prefer transdermal preparations.

- Monitor

cardiovascular risks closely.

- Avoid spironolactone

if eGFR <30 ml/min.

- If history of

cancer, coordinate with oncologist before restarting hormones.

Sexual

health support

- Discuss potential

effects on libido, function and sensitivity.

- Offer support for

sexual concerns, including sex therapy if needed.

- Consider

pharmacological options (PDE-5 inhibitors, topical oestrogens, low-dose

testosterone).

Gender-affirming

surgery

- Confirm diagnosis

and readiness with appropriate documentation.

- Ensure fertility

preservation discussed prior to gonadectomy.

- Refer to qualified

surgeons experienced in gender-affirming procedures.

- Plan

perioperative hormone management (generally continue hormones unless high VTE

risk).

Transition

from adolescence to adult care

- Start planning at

least 1–2 years before transfer to adult services.

- Use joint visits

with paediatric and adult teams if possible.

- Ensure continuous

care and clear handover.

Multidisciplinary

coordination

- Involve

endocrinology, primary care, mental health, reproductive health, dermatology,

speech therapy and surgery as needed.

- Assign a care

coordinator if available.

Documentation

and legal aspects

- Provide clear

records supporting medical necessity for insurance reimbursement.

- Confirm coverage for

non-standard treatments.

- Inform patients of

their rights to legal gender recognition and protections.

Research

and continuous improvement

- Encourage

participation in registries or studies when appropriate.

- Support ongoing

professional development in transgender healthcare.

Acknowledgments

Minor

stylistic revisions were assisted by ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4, GPT-5), under the authors’

supervision. The SSED/SGED provided administrative

support for guideline development.

PD Dr med. Bettina Winzeler

Department of Endocrinology, Diabetology and Clinical Nutrition

Zurich University

Hospital

Raemistrasse 100

CH-8091 Zurich

bettina.winzeler[at]usz.ch

References

1. Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, Brown GR, de Vries AL, Deutsch MB, et al. Standards

of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8. Int J

Transgender Health. 2022 Sep;23 Suppl 1:S1–259. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644

2. Fiani CN, Han HJ. Navigating identity: Experiences of binary and non-binary transgender

and gender non-conforming (TGNC) adults. Int J Transgend. 2018;20(2–3):181–94. doi:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32999605/

3. D’hoore L, T’Sjoen G. Gender-affirming hormone therapy: an updated literature review

with an eye on the future. J Intern Med. 2022 May;291(5):574–92. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.13441

4. Cocchetti C, Ristori J, Romani A, Maggi M, Fisher AD. Hormonal Treatment Strategies

Tailored to Non-Binary Transgender Individuals. J Clin Med . 2020 Jun 1;9(6). doi:

/pmc/articles/PMC7356977/

5. Gender incongruence and transgender health in the ICD. [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available

from: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/frequently-asked-questions/gender-incongruence-and-transgender-health-in-the-icd

6. Fernández Rodríguez M. Gender Incongruence is No Longer a Mental Disorder. J Ment

Health Clin Psychol. 2018 Sep;2(5):6–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.29245/2578-2959/2018/5.1157

7. Nokoff NJ. Medical Interventions for Transgender Youth. [Updated 2022 Jan 19]. In:

Feingold KR, Ahmed SF, Anawalt B, et al., editors. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com,

Inc.; 2000. Table 2. [DSM-5 Criteria for Gender Dysphoria]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK577212/table/pediat_transgender.T.dsm5_criteria_for_g/

8. Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, Brown GR, de Vries AL, Deutsch MB, et al. Standards

of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8. Int J

Transgender Health. 2022 Sep;23 Suppl 1:S1–259. 10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644

9. Ipsos. A 30-Country Ipsos Global Advisor Survey LGBT+ PRIDE 2023. 2023 [cited 2025

Aug 6]; Available from: https://www.ipsos.com/en/pride-month-2023-9-of-adults-identify-as-lgbt

10. Bouman WP, Schwend AS, Motmans J, Smiley A, Safer JD, Deutsch MB, et al. Language

and trans health. International Journal of Transgenderism. 2017 Jan 2;18(1):1–6. doi:

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15532739.2016.1262127

11. van de Grift TC, Mullender MG, Bouman MB. Shared Decision Making in Gender-Affirming

Surgery. Implications for Research and Standards of Care. J Sex Med. 2018 Jun;15(6):813–5.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.03.088

12. Clark BA, Virani A, Marshall SK, Saewyc EM. Conditions for shared decision making

in the care of transgender youth in Canada. Health Promot Int. 2021 Apr;36(2):570–80.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaa043

13. Rudolph H, Burgermeister N, Schulze J, Gross P, Hbscher E, Garcia Nuez D. Von der

Psychopathologisierung zum affirmativen Umgang mit Geschlechtervielfalt. Swiss Medical

Forum ‒ Schweizerisches Medizin-Forum. 2023. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367411586_Von_der_Psychopathologisierung_zum_affirmativen_Umgang_mit_Geschlechtervielfalt doi: https://doi.org/10.4414/smf.2023.09300

14. SR 210 - Schweizerisches Zivilgesetzbuch vom 10. Dezember 1907. Fedlex. [cited 2025

Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/24/233_245_233/de

15. Die Gruppe Verteidigung. [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.vtg.admin.ch/de

16. SR 151.1 - Bundesgesetz vom 24. März 1995 über die Gleichstellung von Frau und Mann

(Gleichstellungsgesetz, GlG). Fedlex. [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/1996/1498_1498_1498/de#art_3

17. Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, Hannema SE, Meyer WJ, Murad MH, et al. Endocrine

Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical

Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017 Nov;102(11):3869–903. 10.1210/jc.2017-01658

18. Haupt C, Henke M, Kutschmar A, Hauser B, Baldinger S, Saenz SR, et al. Antiandrogen

or estradiol treatment or both during hormone therapy in transitioning transgender

women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Nov;11(11):CD013138.

19. Glintborg D, T’Sjoen G, Ravn P, Andersen MS. MANAGEMENT OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE: optimal

feminizing hormone treatment in transgender people. Eur J Endocrinol. 2021 Jun;185(2):R49–63.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-21-0059

20. Kuijpers SM, Wiepjes CM, Conemans EB, Fisher AD, T’Sjoen G, den Heijer M. Toward a

Lowest Effective Dose of Cyproterone Acetate in Trans Women: Results From the ENIGI

Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021 Sep;106(10):e3936–45. doi: https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgab427

21. Hayes H, Russell R, Haugen A, Nagavally S, Sarvaideo J. The Utility of Monitoring

Potassium in Transgender, Gender Diverse, and Nonbinary Individuals on Spironolactone.

J Endocr Soc. 2022 Sep;6(11):bvac133. doi: https://doi.org/10.1210/jendso/bvac133

22. Angus LM, Nolan BJ, Zajac JD, Cheung AS. A systematic review of antiandrogens and

feminization in transgender women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2021 May;94(5):743–52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.14329

23. Irwig MS. Testosterone therapy for transgender men. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Apr;5(4):301–11.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(16)00036-X

24. Meriggiola MC, Gava G. Endocrine care of transpeople part I. A review of cross-sex

hormonal treatments, outcomes and adverse effects in transmen. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf).

2015 Nov;83(5):597–606. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.12753

25. Gava G, Mancini I, Cerpolini S, Baldassarre M, Seracchioli R, Meriggiola MC. Testosterone

undecanoate and testosterone enanthate injections are both effective and safe in transmen

over 5 years of administration. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2018 Dec;89(6):878–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.13821

26. Wierckx K, Van de Peer F, Verhaeghe E, Dedecker D, Van Caenegem E, Toye K, et al. Short-

and long-term clinical skin effects of testosterone treatment in trans men. J Sex

Med. 2014 Jan;11(1):222–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12366

27. Fisher AD, Castellini G, Ristori J, Casale H, Cassioli E, Sensi C, et al. Cross-Sex

Hormone Treatment and Psychobiological Changes in Transsexual Persons: Two-Year Follow-Up

Data. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Nov;101(11):4260–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2016-1276

28. van Dijk D, Dekker MJ, Conemans EB, Wiepjes CM, de Goeij EG, Overbeek KA, et al. Explorative

Prospective Evaluation of Short-Term Subjective Effects of Hormonal Treatment in Trans

People-Results from the European Network for the Investigation of Gender Incongruence.

J Sex Med. 2019 Aug;16(8):1297–309. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.05.009

29. Dickersin K, Munro MG, Clark M, Langenberg P, Scherer R, Frick K, et al.; Surgical

Treatments Outcomes Project for Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding (STOP-DUB) Research

Group. Hysterectomy compared with endometrial ablation for dysfunctional uterine bleeding:

a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Dec;110(6):1279–89. Available

from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18055721/ doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000292083.97478.38

30. Antun A, Zhang Q, Bhasin S, Bradlyn A, Flanders WD, Getahun D, et al. Longitudinal

Changes in Hematologic Parameters Among Transgender People Receiving Hormone Therapy.

J Endocr Soc. 2020 Aug;4(11):bvaa119. doi: https://doi.org/10.1210/jendso/bvaa119

31. Hashemi L, Zhang Q, Getahun D, Jasuja GK, McCracken C, Pisegna J, et al. Longitudinal

Changes in Liver Enzyme Levels Among Transgender People Receiving Gender Affirming

Hormone Therapy. J Sex Med. 2021 Sep;18(9):1662–75. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.06.011

32. Stangl TA, Wiepjes CM, Defreyne J, Conemans E, D Fisher A, Schreiner T, et al. Is

there a need for liver enzyme monitoring in people using gender-affirming hormone

therapy? Eur J Endocrinol. 2021 Apr;184(4):513–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-20-1064

33. Kristensen TT, Christensen LL, Frystyk J, Glintborg D. T’Sjoen G, Roessler KK, et

al. Effects of testosterone therapy on constructs related to aggression in transgender

men: A systematic review. Horm Behav. 2021 Feb 1;128. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33309817/

34. Cocchetti C, Ristori J, Romani A, Maggi M, Fisher AD. Hormonal Treatment Strategies

Tailored to Non-Binary Transgender Individuals. J Clin Med. 2020 May;9(6):1609. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9061609

35. Riggs DW, Bartholomaeus C. Fertility preservation decision making amongst Australian

transgender and non-binary adults. Reprod Health. 2018 Oct;15(1):181. 10.1186/s12978-018-0627-z

36. Amir H, Yaish I, Oren A, Groutz A, Greenman Y, Azem F. Fertility preservation rates

among transgender women compared with transgender men receiving comprehensive fertility

counselling. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020 Sep;41(3):546–54. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.05.003

37. Wiepjes CM, Nota NM, de Blok CJ, Klaver M, de Vries AL, Wensing-Kruger SA, et al. The

Amsterdam Cohort of Gender Dysphoria Study (1972-2015): Trends in Prevalence, Treatment,

and Regrets. J Sex Med. 2018 Apr;15(4):582–90. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.01.016

38. de Nie I, van Mello NM, Vlahakis E, Cooper C, Peri A, den Heijer M, et al. Successful

restoration of spermatogenesis following gender-affirming hormone therapy in transgender

women. Cell Rep Med. 2023 Jan;4(1):100858. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100858

39. Sterling J, Garcia MM. Fertility preservation options for transgender individuals.

Transl Androl Urol. 2020 Mar;9(S2 Suppl 2):S215–26. doi: https://doi.org/10.21037/tau.2019.09.28

40. Cho K, Harjee R, Roberts J, Dunne C. Fertility preservation in a transgender man without

prolonged discontinuation of testosterone: a case report and literature review. F

S Rep. 2020 Apr;1(1):43–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xfre.2020.03.003

41. Barbe JE, Del Vento F, Moussaoui D, Crofts VL, Yaron M, Streuli I. Oocyte cryopreservation

for fertility preservation in transgender and gender diverse individuals: a SWOT analysis.

J Assist Reprod Genet. 2025 Jul:1–9. 10.1007/s10815-025-03579-2

42. De Roo C, Schneider F, Stolk TH, van Vugt WL, Stoop D, van Mello NM. Fertility in

transgender and gender diverse people: systematic review of the effects of gender-affirming

hormones on reproductive organs and fertility. Hum Reprod Update. 2025 May;31(3):183–217.

10.1093/humupd/dmae036

43. Park SU, Sachdev D, Dolitsky S, Bridgeman M, Sauer MV, Bachmann G, et al. Fertility

preservation in transgender men and the need for uniform, comprehensive counseling.

F S Rep. 2022 Jul;3(3):253–63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xfre.2022.07.006

44. Durcan E, Turan S, Bircan BE, Yaylamaz S, Okur I, Demir AN, et al. Fertility Desire

and Motivation Among Individuals with Gender Dysphoria: A Comparative Study. J Sex

Marital Ther. 2022;48(8):789–803. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2022.2053617

45. Jackson SS, Brown J, Pfeiffer RM, Shrewsbury D, O’Callaghan S, Berner AM, et al. Analysis

of Mortality Among Transgender and Gender Diverse Adults in England. JAMA Netw Open.

2023 Jan;6(1):e2253687. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.53687

46. de Blok CJ, Wiepjes CM, van Velzen DM, Staphorsius AS, Nota NM, Gooren LJ, et al. Mortality

trends over five decades in adult transgender people receiving hormone treatment:

a report from the Amsterdam cohort of gender dysphoria. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol.

2021 Oct;9(10):663–70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00185-6

47. Robinson IS, Rifkin WJ, Kloer C, Parker A, Blasdel G, Shakir N, et al. Perioperative

Hormone Management in Gender-Affirming Mastectomy: Is Stopping Testosterone before

Top Surgery Really Necessary? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023 Feb;151(2):421–7. [cited 2025

Aug 6] Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/365403495_Perioperative_Hormone_Management_in_Gender-Affirming_Mastectomy_Is_Stopping_Testosterone_Before_Top_Surgery_Really_Necessary doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000009858

48. gynécologie suisse. Algorithmen zum Expertenbrief Nr. 50. 2018. Available from: https://www.sggg.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/Formulardaten/Algorithmen_zum_Expertenbrief_Nr_50_D.pdf

49. Turo R, Jallad S, Prescott S, Cross WR. Metastatic prostate cancer in transsexual

diagnosed after three decades of estrogen therapy. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7(7-8):E544–6.

doi: https://doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.175

50. Miksad RA, Bubley G, Church P, Sanda M, Rofsky N, Kaplan I, et al. Prostate cancer

in a transgender woman 41 years after initiation of feminization. JAMA. 2006 Nov;296(19):2316–7.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.19.2316

51. Nik-Ahd F, De Hoedt AM, Butler C, Anger JT, Carroll PR, Cooperberg MR, et al. Prostate-Specific

Antigen Values in Transgender Women Receiving Estrogen. JAMA. 2024 Jul;332(4):335–7.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2024.9997

52. van Zijverden LM, Wiepjes CM, van Diemen JJ, Thijs A, den Heijer M. Cardiovascular

disease in transgender people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol.

2024 Feb;190(2):S13–24. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/ejendo/lvad170

53. Maraka S, Singh Ospina N, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Davidge-Pitts CJ, Nippoldt TB, Prokop LJ,

et al. Sex Steroids and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Transgender Individuals: A Systematic

Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017 Nov;102(11):3914–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2017-01643

54. Leemaqz SY, Kyinn M, Banks K, Sarkodie E, Goldstein D, Irwig MS. Lipid profiles and

hypertriglyceridemia among transgender and gender diverse adults on gender-affirming

hormone therapy. J Clin Lipidol. 2023;17(1):103–11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2022.11.010

55. Kcomt L, Evans-Polce RJ, Veliz PT, Boyd CJ, McCabe SE. Use of Cigarettes and E-Cigarettes/Vaping

Among Transgender People: Results From the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Am J Prev

Med. 2020 Oct;59(4):538–47. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.03.027

56. Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Cook-Daniels L, Kim HJ, Erosheva EA, Emlet CA, Hoy-Ellis CP,

et al. Physical and mental health of transgender older adults: an at-risk and underserved

population. Gerontologist. 2014 Jun;54(3):488–500. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt021

57. Streed CG Jr, Beach LB, Caceres BA, Dowshen NL, Moreau KL, Mukherjee M, et al.; American

Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Arteriosclerosis,

Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council

on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Hypertension; and Stroke

Council. Assessing and Addressing Cardiovascular Health in People Who Are Transgender

and Gender Diverse: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation.

2021 Aug;144(6):e136–48. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001003

58. Vlot MC, Wiepjes CM, de Jongh RT, T’Sjoen G, Heijboer AC, den Heijer M. Gender-Affirming

Hormone Treatment Decreases Bone Turnover in Transwomen and Older Transmen. J Bone

Miner Res. 2019 Oct;34(10):1862–72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3762

59. Van Caenegem E, Wierckx K, Taes Y, Schreiner T, Vandewalle S, Toye K, et al. Body

composition, bone turnover, and bone mass in trans men during testosterone treatment:

1-year follow-up data from a prospective case-controlled study (ENIGI). Eur J Endocrinol.

2015 Feb;172(2):163–71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-14-0586

60. Rosen HN, Hamnvik OR, Jaisamrarn U, Malabanan AO, Safer JD, Tangpricha V, et al. Bone

Densitometry in Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming (TGNC) Individuals: 2019 ISCD

Official Position. J Clin Densitom. 2019;22(4):544–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocd.2019.07.004

61. Singh-Ospina N, Maraka S, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Davidge-Pitts C, Nippoldt TB, Prokop LJ,

et al. Effect of Sex Steroids on the Bone Health of Transgender Individuals: A Systematic

Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017 Nov;102(11):3904–13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2017-01642

62. Fighera TM, Ziegelmann PK, Rasia da Silva T, Spritzer PM. Bone Mass Effects of Cross-Sex

Hormone Therapy in Transgender People: Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.

J Endocr Soc. 2019 Mar;3(5):943–64. doi: https://doi.org/10.1210/js.2018-00413

63. Wiepjes CM, Vlot MC, Klaver M, Nota NM, de Blok CJ, de Jongh RT, et al. Bone Mineral

Density Increases in Trans Persons After 1 Year of Hormonal Treatment: A Multicenter

Prospective Observational Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2017 Jun;32(6):1252–60. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3102

64. Giacomelli G, Meriggiola MC. Bone health in transgender people: a narrative review.

Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2022 May;13:20420188221099346. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/20420188221099346

65. Ferrari S, Lippuner K, Lamy O, Meier C. 2020 recommendations for osteoporosis treatment

according to fracture risk from the Swiss Association against Osteoporosis (SVGO).

Swiss Med Wkly. 2020 Sep;150(3940):w20352. doi: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2020.20352

66. Verroken C, Collet S, Lapauw B, T’Sjoen G. Osteoporosis and Bone Health in Transgender

Individuals. Calcif Tissue Int. 2022 May;110(5):615–23. 10.1007/s00223-022-00972-2

67. Cai X, Hughto JM, Reisner SL, Pachankis JE, Levy BR. Benefit of Gender-Affirming Medical

Treatment for Transgender Elders: Later-Life Alignment of Mind and Body. LGBT Health.

2019 Jan;6(1):34–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2017.0262

68. Collister D, Saad N, Christie E, Ahmed S. Providing Care for Transgender Persons With

Kidney Disease: A Narrative Review. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2021 Jan;8:2054358120985379.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/2054358120985379

69. Hancock AB, Siegfriedt LL. Transforming Voice and Communication with Transgender and

Gender-Diverse People: An Evidence-Based Process. San Diego (CA): Plural Publishing

Inc.; 2020.

70. Ginsberg BA. Dermatologic care of the transgender patient. Int J Womens Dermatol.

2016 Dec;3(1):65–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijwd.2016.11.007

71. Miroshnychenko A, Ibrahim S, Roldan Y, Kulatunga-Moruzi C, Montante S, Couban R, et

al. Gender affirming hormone therapy for individuals with gender dysphoria aged <26

years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2025 May;110(6):437–45.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2024-327921

72. van de Grift TC, Elaut E, Cerwenka SC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, De Cuypere G, Richter-Appelt H,

et al. Effects of Medical Interventions on Gender Dysphoria and Body Image: A Follow-Up

Study. Psychosom Med. 2017 Sep;79(7):815–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000465

73. Krakowsky Y, Grober ED. A practical guide to female sexual dysfunction: an evidence-based

review for physicians in Canada. Can Urol Assoc J. 2018 Jun;12(6):211–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.4907

74. Steers WD. Pharmacologic treatment of erectile dysfunction. Rev Urol. 2002;4(Suppl

3 Suppl 3):S17–25. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1476024/

75. Qaseem A, Humphrey LL, Harris R, Starkey M, Denberg TD; Clinical Guidelines Committee

of the American College of Physicians. Screening pelvic examination in adult women:

a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern

Med. 2014 Jul;161(1):67–72. doi: https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-0701

76. Bockting WO, Robinson BE, Forberg J, Scheltema K. Evaluation of a sexual health approach

to reducing HIV/STD risk in the transgender community. AIDS Care. 2005 Apr;17(3):289–303.

10.1080/09540120412331299825

77. Aaron KJ, Griner S, Footman A, Boutwell A, Van Der Pol B. Vaginal Swab vs Urine for

Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis: A Meta-Analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2023;21(2):172–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2942

78. Radix AE, Harris AB, Belkind U, Ting J, Goldstein ZG. Chlamydia trachomatis Infection of the Neovagina in Transgender Women. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019 Nov;6(11):ofz470.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofz470

79. Home: LOVE LIFE - Sex aber sicher. [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://lovelife.ch/de

80. Recommendations of the Swiss Federal Commission for Sexual Health (FCSH) on pre-exposure

prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention. [cited 2025 Aug 6]; Available from: www.who.int/hiv/pub/

81. PROFA | Contraception transmasculine: un mémo pour les pros. [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available

from: https://www.profa.ch/contraception-transmasculine

82. Okano SH, Pellicciotta GG, Braga GC. Contraceptive Counseling for the Transgender

Patient Assigned Female at Birth. RBGO Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2022 Sep 1;44(9):884.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-1751063

83. Gelles-Soto D, Ward D, Florio T, Kouzounis K, Salgado CJ. Maximizing surgical outcomes

with gender affirming hormone therapy in gender affirmation surgery. J Clin Transl

Endocrinol. 2024 May;36:100355. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcte.2024.100355

84. Hontscharuk R, Alba B, Manno C, Pine E, Deutsch MB, Coon D, et al. Perioperative Transgender

Hormone Management: Avoiding Venous Thromboembolism and Other Complications. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 2021 Apr;147(4):1008–17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000007786

85. Kozato A, Fox GW, Yong PC, Shin SJ, Avanessian BK, Ting J, et al. No Venous Thromboembolism

Increase Among Transgender Female Patients Remaining on Estrogen for Gender-Affirming

Surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021 Mar;106(4):e1586–90. doi: https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa966

86. Herndon J, Gupta N, Davidge-Pitts C, Imhof N, Gonzalez C, Carlson S, et al. Genital

Surgery Outcomes Using an Individualized Algorithm for Hormone Management in Transfeminine

Individuals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024 Oct;109(11):2774–83. doi: https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgae269

87. Salas-Humara C, Sequeira GM, Rossi W, Dhar CP. Gender affirming medical care of transgender

youth. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2019 Sep;49(9):100683. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2019.100683

88. Mellerio H, Jacquin P, Trelles N, Le Roux E, Belanger R, Alberti C, et al. Validation

of the “Good2Go”: the first French-language transition readiness questionnaire. Eur

J Pediatr. 2020 Jan;179(1):61–71. 10.1007/s00431-019-03450-4

89. SR 832.102 - Verordnung vom 27. Juni 1995 über die Krankenversicherung (KVV). Fedlex.

[cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/1995/3867_3867_3867/de

90. 07 - WZW - SGAIM - SSMIG - SSGIM. [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.sgaim.ch/de/themen/swissdrg-blog/07-wzw

91. SCHLUMPF c. SUISSE. [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/fre#{%22itemid%22:[%22001-90476%22]}

92. Recht | TGNS Transgender Network Switzerland. [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from:

https://www.tgns.ch/de/information/rechtliches/recht/

93. Remuneration of medicinal products in individual cases. [cited 2025 Aug 21]. Available

from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/de/verguetung-von-arzneimitteln-im-einzelfall

94. Fedlex. Verordnung über die Krankenversicherung / Ordonnance

sur l’assurance-maladie. Available from: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/1995/3867_3867_3867/de