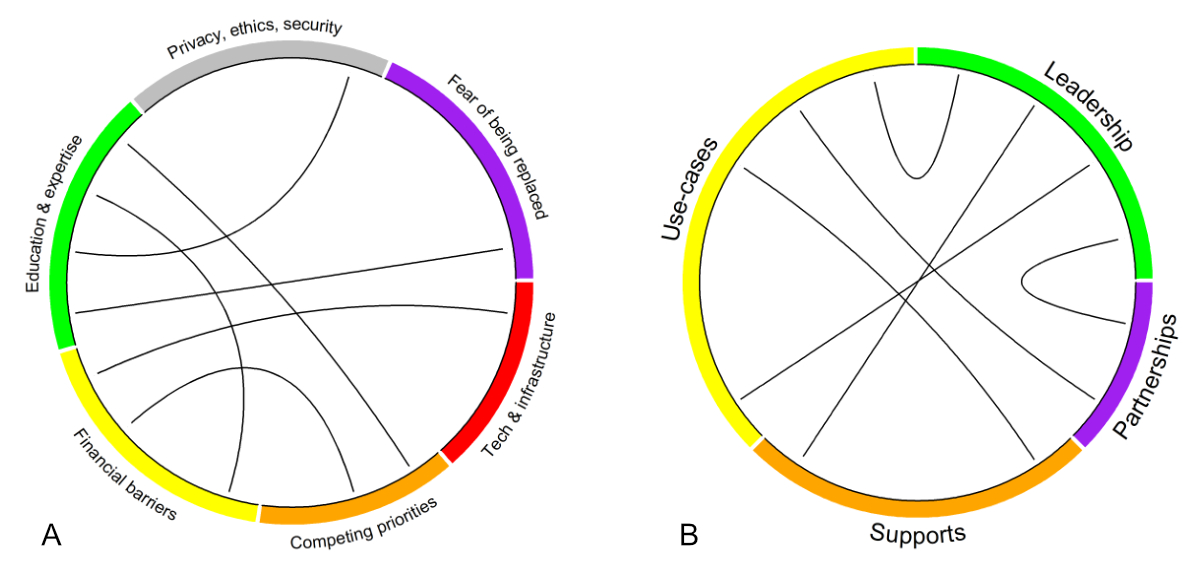

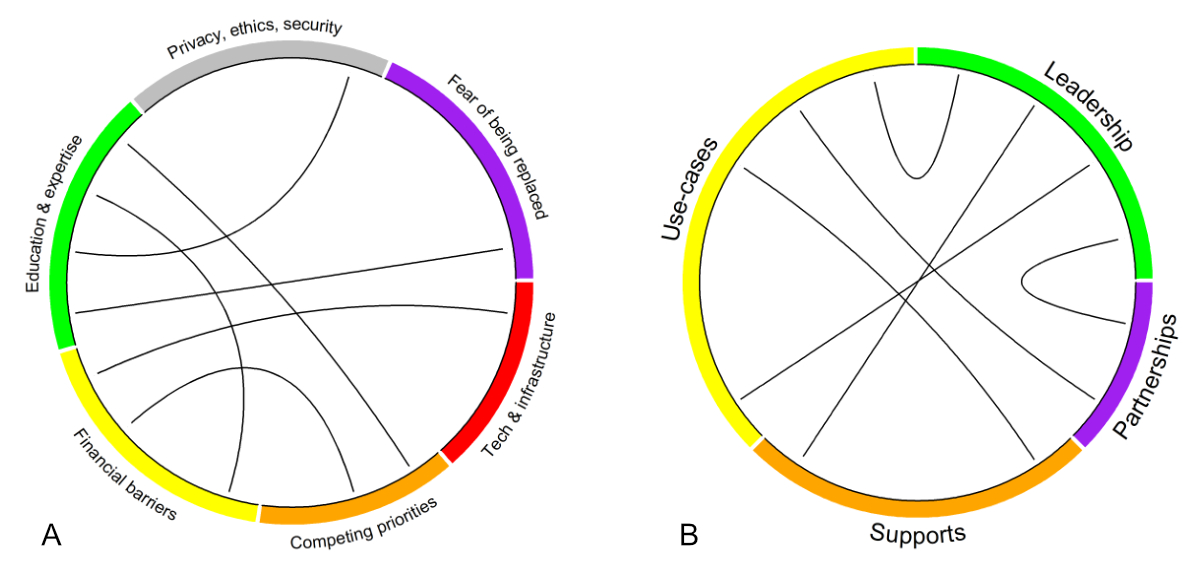

Themes following key informant interviews. Themes were categorised as barriers (A) and enablers (B). Lines connect themes believed to be directly interconnected.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/4942

Recent advances in intelligent agents, entities that can react autonomously based on inputs from their environment, have resulted in widespread adoption of such agents in the private sector [1]. In the public health sector, there is increasing recognition of the need to keep pace with the evolution of data analytics, and this includes machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) [2]. Unlike private sector organisations, public health agencies are more risk-averse and a publicly funded healthcare system is not subjected to the same financial opportunities or pressures as for-profit institutions are.

Regardless of jurisdiction, public sector health organisations strive to improve the health of populations through a wide range of interrelated activities, including disease surveillance; forecasting; health technology assessment; public education; preventive measures for risk reduction; and health and human resource allocation [3]. With such breadth, there are a range of applications for AI/ML that may overlap from one public health organisation to the next. Whether such methods offer advantages (or not) compared with traditional methods grounded in epidemiology, health economics, operations research, qualitative synthesis, and other disciplines remains to be seen. However, governments and public authorities may not be aware of the full range of AI/ML applications, opportunities, risks, as well as barriers and challenges, and the literature is limited on this topic.

The purpose of this study was to understand the barriers and enablers of AI/ML in public sector health organisations in a publicly funded health system. Following key informant interviews, we identified whether (and how) AI/ML was being used (or would like to be used) and make recommendations for advancing AI/ML in the public sector.

For the present study, we use the term artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) broadly. Prior to conducting the interviews, we defined AI/ML as an area of study traditionally within the field of computer science dedicated to solving problems commonly associated with human intelligence, such as learning, problem solving, visual perception, and speech and pattern recognition [4]. AI in public health is the application of these techniques to improve disease surveillance, diagnosis, treatment personalisation, resource allocation and healthcare policy.

This study was conducted from the perspective of public sector health organisations in Ontario, Canada’s most populous province. In Canada, healthcare is provisioned under a single-payer system, and despite national alignment, healthcare is managed at the provincial level. The Ontario Ministry of Health oversees funding and operations of healthcare and public health in the province. In scope of the present study, we chose organisations that reflect different public sector health organisations and conducted key informant interviews with mid-to-senior-level staff and management at Ontario Health, Public Health Ontario and Toronto Public Health.

Ontario Health oversees healthcare planning and coordination across the province, including cancer care, kidney disease, mental health and addiction, organ and tissue donation, and palliative care, delivered across a range of settings including primary care, acute care, long-term care and community services. Ontario Health does not provide clinical services. Public Health Ontario provides scientific evidence and expert guidance on chronic disease prevention, infection control and diseases of public health significance without providing direct clinical services. Toronto Public Health is responsible for preventing the spread of disease, promoting healthy living and advocating for conditions that improve health for residents of Toronto, Ontario’s most populous city. Toronto Public Health provides clinical services focusing on specific health needs like breastfeeding, dentistry, immunisation, sexual health, drug use and harm-reduction supplies.

The present study was approved by the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board (#45652). Interviewees and the organisations they work at will be kept anonymous if not already in the public domain. Any quotations provided in this report were edited for clarity or to ensure anonymity. All opinions are those of the individual and do not necessarily reflect those of their organisation. We follow the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (appendix 2) [5].

Key informant interviews were performed between January 2024 and March 2024. Oral interviews were conducted on a virtual platform (Microsoft Teams) by epidemiologists/methodologists who have worked in the public sector for a total of 25 years, having experience in data analytics, health policy and data-informed decision-making in the public sector. Key informants were identified a priori by interviewers based on institutional knowledge of who would be good candidates as key opinion leaders on the topic of AI/ML in their respective organisations. Interviewees were asked to provide contacts of their peers who may be able to provide additional insights (snowballing approach). This was continued until data saturation was believed to have been achieved, while considering the time investments required to conduct further interviews [6]. The general script used to guide our interviews is provided in appendix 1; briefly, it covered the following topics:

Interviews were conducted, recorded and transcribed using Microsoft Teams. Audio recordings were extracted from the recordings and saved to allow clarification of transcripts if necessary. Each transcript was imported into NVivo14 for coding into themes independently by two investigators (split between SH, TB and JH).

Synthesis followed the post-positivist research paradigm, and we acknowledge that the preconceived notions of the research team are implicitly embedded within the analysis [7]. Coding was both theory-driven (e.g. a result of the subject-matter expertise of the research team; some high-level codes like “enablers” and “barriers” were pre-determined) and data-driven (e.g. researchers created more-specific codes like “financial barriers” or new codes as necessary while reviewing the transcripts) [8,9]. Codes were compiled into themes based on their perceived commonalities, organisational hierarchies and pragmatism, supported using representative quotes.

Intercoder reliability was assessed with percent agreement [10]. First, the transcripts were chunked out into sentences or blocks of sentences reflecting the same stream of thought. This was done because of transcription quality (e.g. pauses in the audio were transcribed into periods and therefore new sentences); interviewee style (e.g. more-elaborate responses with examples would produce more words that can affect character or word overlap rates); idiosyncrasies of individual coders (e.g. one may code a single word from a sentence, while another may have coded the entire sentence to capture the context); and transcript content (e.g. interviewer questions were included). These issues would yield inter-coder reliability statistics unreflective of the actual agreement [10]. We consider a percent agreement >70% to be acceptable [11].

Themes are presented and mapped to the AI Maturity Framework published by Element AI, which classifies an enterprise according to five levels of maturity (exploring > experimenting > formalising > optimising > transforming) across five dimensions (strategy, data, technology, people, governance) [12]. Specific to the public sector, the IBM Center for the Business of Government has released their own framework with six elements divided into technical elements (big data; AI systems; analytical capacity) and organisation elements (innovative climate; governance and ethical frameworks; and strategic visioning) [13].

An in-person workshop was held in Toronto on 15 May 2024. Participation was open to the public, but word-of-mouth invitations were extended to the research team’s peers. Participants did not consent to the collection of their sociodemographic data for reporting, but were from a wide range of roles, including graduate students, managers, directors, scientists and Associate Medical Officers of Health. Following a presentation of the themes identified from the key informant interviews (see results below), attendees were asked to think about, discuss with the other participants seated at their table, and report on a set of questions on “How to build data science functionality in public sector organisations”. A thematic analysis of responses to these questions was not conducted, but the group discussions offered a venue to supplement the findings from the key informant interviews, strengthening the validity of the thematic analysis through triangulation of methods (e.g. in-depth individual interview versus group discussion) [14, 15].

A total of 13 interviews were conducted; the interviewees comprised 5 managers, 3 medical officers, 2 directors, 1 advisor, 1 scientist and 1 biostatistician; 6 of the interviewees were from Toronto Public Health, 4 from Public Health Ontario and 3 from Ontario Health. The mean duration of interviews was 51 minutes (standard deviation: 9.8 minutes). The pair-wise inter-coder reliability was 77%, 79% and 87%. After coding the transcripts, the following themes emerged, which we present as barriers (figure 1A) and enablers (figure 1B).

Themes following key informant interviews. Themes were categorised as barriers (A) and enablers (B). Lines connect themes believed to be directly interconnected.

One barrier is insufficient knowledge, skills, expertise and experience with AI/ML. AI/ML was not featured in the formal training of the existing workforce, and interviewees felt that they do not have the required knowledge to lead an AI initiative without further training. This includes the technical skillset needed for effectively using R and Python for AI/ML, analytics programs recently embraced by public health agencies.

“I'm in the process of learning it [Python] truthfully at the moment thinking that it’s a requirement for future work with AI.” – [Advisor]

Owing to competing priorities and current job demands, there is a perception that there is little time to devote to learning what is perceived as a new field of study (AI), understanding the complexities of building and communicating machine-learning models, and learning unfamiliar syntax (R and Python).

“Data literacy and knowledge of what these terms actually mean in application to our work takes a significant amount of effort.” – [Director]

“I think all of us early adopters are starting to form our own little group at work and we’re connecting. But I think there’s a huge swathe of people within the organisation who don’t understand what all this is.” – [Associate Medical Officer of Health]

There are additional competing priorities that serve as barriers to advancing AI/ML in the public health sector. Even in January to May 2024, public health organisations are re-focusing their efforts on restarting work that was put on hold during the COVID-19 pandemic with little bandwidth to start new projects:

“You know, we’ve been so, you know, heads-down focused in on the pandemic, which coincided with this rapid explosion of AI that, you know, our focus has been recovering from the pandemic and getting our programs running.” – [Manager]

Moreover, people are aware that significant financial investment (time and people) would be required to do things properly and avoid the risk of reputational harm:

“If you don’t do it right the first time, that perception, it’s kind of difficult to erase, right?” – [Manager]

Interviewees shared the sentiment that machine-learning methods require significant amounts of data and computational resources. However, additional education and training would be important to ascertain whether these barriers are merely challenges or are truly insurmountable. For use cases that do require computational power beyond what is currently available, access to such resources may limit public sector health organisations depending on their level of computational maturity. Changing technology in a large organisational structure is difficult, costly and takes time.

“Our tech is archaic. We don’t have the resources for the appropriate technology… I don’t think we have enough staff who know how to code and use the technology.” – [Associate Medical Officer of Health]

Significant and sustained investment is needed to accomplish two complementary aims. The first is to augment the knowledge base of the workforce by hiring staff with the required skillsets (but who may lack subject-matter expertise) and upskill current staff who may have subject-matter and organisational expertise but lack the domain-specific knowledge.

“Even in terms of training people up to be able to do the work right, trying to get decision scientists and data scientists into the organisation, you’re paying a premium for those types of analysts because their skills are in high demand.” – [Manager]

The second is to modernise technology to ensure the right computational requirements and resources are available.

“Technology implementations are not cheap if you want to do them properly.” – [Manager]

“Existing budgets don’t have any space for new funding for AI technology.” – [Manager]

Public health organisations collect personal identifying information (PII) and personal health information (PHI) for the purposes of health system monitoring, health system planning and quality improvement. A lack of education and clarity around the terms “machine learning” and “artificial intelligence” can stoke fear from the perspectives of those whose role is to safeguard the privacy and security of the data. AI/ML can appear “too risky” to a public sector organisation that is culturally risk-averse.

“The culture in this area is pretty risk-averse… And no matter where you’re coming from, these pieces of technology look risky.” – [Associate Medical Officer of Health]

It is not always possible to completely anonymise or pseudonymise data for the needs of public sector health organisations. Examples include parsing through clinic notes (free text), transcribing data directly into the medical charts to reduce administrative burden on physicians, and case-contact management systems for infection control. There is uncertainty around the privacy, ethical and security concerns around cloud-based platforms that are managed by a third-party (external) agency.

“Perception that it is impossible… we still have a lot of people that think the cloud is not secure.” – [Manager]

While there is recognition of the benefits to enable scale, there are data ownership concerns associated with the use of commercial AI platforms. In particular, a public sector health organisation can benefit from the use of a commercial AI platform, but peoples’ health data are used to improve such platforms. The commercial entity recovers the financial rewards of such an improvement, but the data used for the improvement is not theirs.

“Whatever records that I would use to feed into AI need to lack PHI [personal health information]. And it also depends on agreements with AI vendors… so there’s the legal aspects in terms of whether they retain the data, the data models, et cetera.” – [Advisor]

Responsible use is also important. Unsupervised AI/ML models could miss important health issues, incorporate bias or can become less accurate over time. These effects can directly impact population health, necessitating validity checks and periodic re-assessment of accuracy.

“It needs to be done in a way that’s transparent, ethical, accurate and is monitored over time to ensure that there’s no bias in the process.” – [Director]

“We can’t go into the use of AI lightly, especially for something like Communicable Disease Control, where you’re dealing with life and death.” – [Manager]

Lastly, there was some acknowledgement that people may be afraid of losing their jobs, but the interviewees did not share this sentiment given their familiarity with the topic. Education is critical to help staff and leadership understand efficiencies that will be gained, including time that can be better spent elsewhere.

“We can dedicate people’s time to better things.” – [Director]

“I’m not trying to make everyone unemployed here, but I’m just saying there’s a lot of solutions that could create a lot of efficiencies from the business perspective.” – [Associate Medical Officer of Health]

“I don’t think people are worried about losing their jobs, mostly because the way that these presentations are explained. It’s not about replacing somebody, it’s about augmenting them.” – [Advisor]

An organisational strategic plan that specifically mentions AI as a priority would enable it to move forward with the necessary financial support, governance system and encouragement from senior-level champion(s). Developing and disseminating standards, best practices, and legislation governing this work would be valuable to ensure success.

“We need more support from people at a higher senior level to encourage or motivate or support us.” – [Biostatistician]

“Needing to have structure/governance to enable this work to happen, including use cases/organisation priorities.” – [Manager]

“Need to have the commitment from senior management to be willing to walk that road with you and making sure that you’re choosing the right examples or the right proof-of-concepts or the right services.” – [Manager]

Creating partnerships with other public sector organisations and academic organisations with expertise in AI was seen as important for success. Other public sector organisations (not necessarily specific to health) have already implemented an AI/ML solution that others may benefit from or learn from. For select applications that focus on uncommon events of public health importance (e.g. measles infection, mpox infection), pooling data across multiple jurisdictions will enable more robust models for training and testing that can benefit all partners.

“The tools require a lot of data to train to get them better… so we need to collaborate across the province or even across the country.” – [Associate Medical Officer of Health]

Partnerships with academic organisations that have the expertise but not the data or the policy context creates another win-win scenario: public sector health organisations will gain experience and computational proficiency to accomplish their goal, while academicians will have the opportunity to develop their methods further to meet the real-world use cases.

“There is a gap between academia and public health.” – [Scientist]

“We need to partner together instead of going it alone.” – [Manager]

In order to demonstrate the benefit of AI to leadership, successful applications are needed. At the organisational level, gains in efficiency (e.g. freeing up human resources for other important tasks) demonstrate a return on investment, which in turn can fuel further investment. At the population level, success can manifest through better access to information and services to provide the right care when and where it is needed, and lower waiting times for receiving care (e.g. centralised referral systems; higher patient-physician throughput by reducing the administrative burden on physicians). Use cases that arose tended to focus on increasing efficiency of the health system:

“I sometimes feel like they don’t get our day-to-day, and just even advocating for things like AI scribes would literally save hundreds and thousands of person-hours, which we can then invest those human hours into, like connecting with the community and preventing illness.” – [Associate Medical Officer of Health]

“It reduces our use of human resources in low-valued work like answering the phone… Wouldn’t it be great to automate that so that we can use our human resources in areas that are more valued?” – [Associate Medical Officer of Health]

Initial or first use cases are preferably simple so they can be explained to a broad audience and quickly gain confidence and buy-in. Interviewees acknowledged that we don’t need to implement a full solution for a proof-of-concept type project.

“Getting some support to prioritise which use cases have the most impact.” – [Manager]

“Making sure that you’re choosing the right examples or the right proof-of-concepts or the right services.” – [Manager]

This section describes the in-person debriefing exercise to reflect on the findings and discuss specific questions related to themes culminating from the key-informant interviews.

Where do you see the biggest potential for data science applications in your organisations?

One point raised was gaining efficiency from day-to-day tasks or tasks deemed time-consuming and repetitive. General examples include using AI to write code or screen the literature (with or without information extraction) on a specific topic.

Building on what you heard, what are the main obstacles to achieving data science functionality in your organisations / in the public sector?

One obstacle was the fact that AI/ML is still in its infancy from the perspective of public sector health organisations. Those select early innovators are pioneering a few applications, and existing leadership is not knowledgeable enough to fully be able to set a strategy that considers the risks and benefits. Importantly, there is still a lack of clarity on why AI/ML is needed.

What are creative ways we can overcome these barriers?

One issue that was raised was the limited quality of the data that are ultimately used to build AI models. One solution was to use AI to improve the quality of the digitisation of health information at the source (e.g. primary care at the point of care/access). Investing in AI infrastructure and training at those sources may have the most impactful downstream effects.

Privacy has come up a lot as a barrier; how do we move past this?

There was a call to make data more accessible, and a centralised point of access to data has been suggested. Distrust in cloud-based tools was stated as a concern, and one potential solution was to gain a more thorough understanding of the security features that cloud-based tools offer.

Who do we partner with outside the public sector to enable data science? How do we govern these partnerships?

Creating and maintaining partnerships outside the public sector was seen as valuable, but there is a lot of uncertainty because of privacy, governance and organisational policy issues. It is also difficult to govern policy on AI given the frequent changes and variable regulatory environment.

Data science infrastructure will take investment, partnership and accountability – who do you see taking on these roles?

Without standards, people may feel uncomfortable advancing AI/ML in their organisation. Canada’s Artificial Intelligence and Data Act (AIDA) and Bill 194 “Strengthening Cyber Security and Building Trust in the Public Sector Act, 2024”, while not specific to the healthcare industry, is a good start to providing a foundational policy and regulatory context [16, 17]. Learning from other jurisdictions that may be further along the process of AI/ML adoption and understanding the strengths and limitations of AI/ML are important to govern its appropriate use.

Following key informant interviews at three public sector health organisations and a tabletop exercise at an open workshop, we find that health organisations within Ontario’s public sector are “relatively inexperienced” in AI/ML, dependent on motivated staff to take the lead on projects and engage external partners [18].

We identified several barriers and enablers for using AI/ML. These findings align with some of the priorities identified from literature reviews, including data governance; analytic infrastructure; workforce knowledge and skills gap; development of strategic collaborative partnerships; and embracing AI as a tool [18–20]. Although the purpose of this study was not to establish the state of AI Maturity in public sector health organisations, the comments from the key informant interviews suggest that these organisations are either in the exploration/ad hoc phase (e.g. the organisation is learning about AI) or experimentation phase (e.g. assessing proof-of-concepts) of AI maturity [12, 13]. Element AI’s AI Maturity survey was administered to a range of organisations in 2019–2020 [12]. Although focused on the private sector, results are similar to ours with most organisations in the exploration and experimentation phases. The most advanced sector was health, pharma and biotechnology companies, in which 20% of companies reported operating in the formalising (20%), optimising (7%) or transforming phases (7%) [12]. Although a survey of public sector organisations was not reported, our key informant interview responses also align with organisations predominantly in the exploration/ad hoc (phase I), experimentation (phase II), and planning and deployment (phase III) stages of maturity.

To advance AI/ML in the public sector, changes must be made at multiple levels within an organisation, enabled by project management, change management, publication of policies/guidelines and knowledge translation. As a starting point, many organisations working with PHI have begun to adopt analytic programs and reorganise their information technology infrastructure to support AI/ML. Part of the change management process involves giving people time to react and dispelling myths or misconceptions. For example, respondents shared fears about the security of cloud computing, yet most major data organisations are moving their data (or already have) to a cloud provider. This is essential for enabling advanced analytics (e.g. large language models) and growing costs associated with maintaining ever-increasing data repositories [21–23].

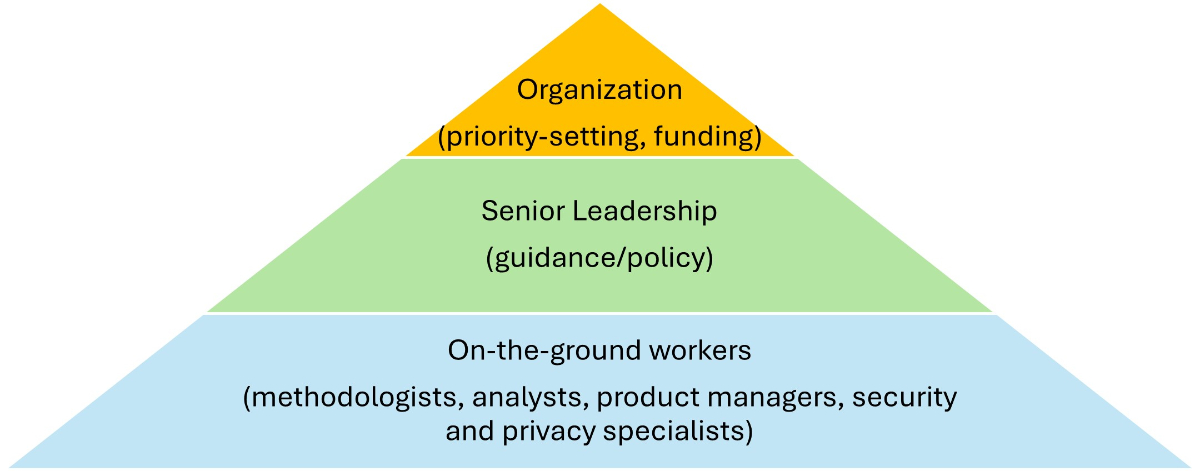

Decisions are made by senior leadership but require organisation-wide restructuring to allow product managers, security specialists and privacy experts to ensure work with PHI is appropriate (figure 2). Moreover, the transition directly affects on-the-ground workers tasked with implantation and use, requiring persistent messaging and support for successful change management [18].

Organisational changes required to enable AI/ML.

Greenhalgh et al. developed a conceptual model for considering the determinants of diffusion (passive spread), dissemination (active and planned efforts for adoption) and implementation (active and planned efforts to convert an innovation into mainstream) of innovations in public sector health organisations [24]. There are many forces influencing whether (and how) an innovation like AI/ML will pervade the public healthcare system, including features of the innovation itself, communication and influence of the people within the organisation, system antecedents, system readiness for innovation, adoption/assimilation and the implementation process [24]. Previous work on performance measurement speaks to the importance of leadership (e.g. formalised prioritisation) and organisational commitment (e.g. dedicated funding) in performance improvement, factors identified by our study as key enablers [25].

The rate at which AI/ML is advancing continues to outpace that of regulation, opening the door for harms that can affect peoples’ lives, jeopardise the reputation of an organisation and thwart potential gains that can otherwise be achieved by using AI/ML [26]. For example, the chatbot Tessa that was meant to serve as a human-free eating disorder hotline was discontinued after giving people bad advice [27]. As another example, racial biases have been recognised as a risk to any predictive model, but is further complicated in the context of AI/ML because even in scenarios when racial data are invisible to the algorithm, algorithms may still not be free of biases [28–30]. Being aware of such biases is important but not always obvious when they occur through unknown or unpredictable mechanisms [28, 31, 32]. Interviewees did not consistently identify bias as a risk for AI/ML, nor did they mention Indigenous data sovereignty or public trust as barriers, suggesting that these areas are not yet fully appreciated. Because public sector health organisations often access and use sensitive and identifiable information on the population they serve, care must be taken to ensure the potential impact of AI on equity is explored and understood, and protected data (e.g. Indigenous identity) are not incidentally unmasked. Transparency and methodological rigour are needed to promote public trust in AI applications, particularly when the methods are not always explainable [33–35]. On 1 December 2024, the Government of Ontario issued the Responsible Use of Artificial Intelligence Directive, which applies to all publicly funded agencies in the province [36]. This directive requires all agencies to create a policy around the use of AI, which includes activities related to ensuring transparent, responsible and accountable use of AI.

From these experiences and the results from the key informant interviews and tabletop discussions, we recommend small-scale use cases that can be used as proof-of-concept with rigorous pilot testing to ensure we understand the risks and limitations before widespread implementation in public sector health organisations. These findings align with recommendations following a survey of eight Swiss public organisations also in an early stage of AI maturity [18]. Another useful construct is to consider formal partnerships and exchanges across policy and academia that can serve to address many of the technical and expertise challenges while ensuring the health and policy relevance.

One of the strengths of this study is the interpretation of the findings in conjunction with existing frameworks. Public sector organisations can directly apply these findings to target specific aspects of their organisational structure, culture and workforce to align with their strategic goals around AI use. For a publicly funded system, efficient and appropriate use of resources is critical to ensure that any investments into AI yield a return, either through improved efficiency, cost savings, or cost-effectiveness, while maintaining fairness, transparency, human resources, and encouraging public trust.

One limitation of the present study is the potential for interviewer biases to overshadow some of the themes that may have been present in the data. However, this may be acknowledged as a fundamental aspect of post-positivist qualitative research that is better to be acknowledged than dismissed [7, 9, 37]. Another limitation is the potential for AI to quickly render some of the themes or comments obsolete. For example, readily accessible large language models having human-like performance for coding in an array of programmatic languages may remove this component as a barrier to AI/ML implementation [38]. Another limitation is the AI environment is changing rapidly. Since the time the interviews were conducted and the time of reading, many of the elements and sub-elements of either AI Maturity Framework examined may have advanced. With the governmental AI Directive in place, all public organisations are mandated to develop their AI policies, which includes AI and data governance, assessing data readiness for AI and educating staff on the risks and policies around AI usage. Formal assessments of AI Maturity are warranted, and these should be repeated more frequently to reflect the pace of AI development and accessibility.

We believe our results are transferrable to industries beyond healthcare that are in a similar state of maturity around AI/ML adoption [39]. Although industry-specific challenges and use cases may arise, the same barriers and enablers would be relevant to applications of AI/ML. Examples include areas such as education where teachers are seeking to leverage AI to assist with day-to-day tasks like scheduling and planning [40]. An interview hosted by Ontario’s Information and Privacy Commissioner’s office on the use of technology in the classroom illustrates the risks around privacy and exploitation of public dollars by “persuasive technology” from third-party vendors integrating their AI products into existing infrastructure [40]. Many of these issues have direct corollaries to public sector health organisations, with AI Scribes being one prominent example and AI-enabled electronic medical records being another [41]. The AI strategy for Canada’s Federal Public Service 2025–2027, which is not specific to the health sector, has identified three of four sector-agnostic priorities with commonalities with our findings: 1) central AI capacity (e.g. identifying use cases, assessing risk); 2) policy, legislation and governance relevant to the AI era; and 3) talent and training [42].

Various barriers to AI implementation in public sector health organisations exist, including 1) knowledge, education and expertise; 2) privacy, ethics and security; 3) technology and infrastructure; 4) financial barriers; 5) competing priorities; and 6) fear of being replaced. Key enablers include 1) partnerships; 2) buy-in and support from senior leadership; 3) management and operational supports; and 4) actionable use cases. Demonstrating success from a few small-scale applications is important to identify risks and opportunities for improvement, but it is also important to share knowledge, experiences, and measure success for the perspectives of different partners within and across different organisations. Partnerships between academic and policy organisations provide one way to overcome limitations raised.

Even with redaction, transcripts can potentially identify the interviewee. Participants therefore did not consent to publishing their transcripts but agreed that representative and de-identified quotes can be published for the purpose of the article.

We acknowledge and thank the key informants for donating their time and opinions for this work.

This work was funded by the Data Science Institute (DSI) and the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript was disclosed.

1. Huang KA, Choudhary HK, Kuo PC. Artificial Intelligent Agent Architecture and Clinical Decision-Making in the Healthcare Sector. Cureus. 2024 Jul;16(7):e64115. doi: https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.64115

2. Gupta A, Singh A. Healthcare 4.0: recent advancements and futuristic research directions. Wirel Pers Commun. 2023;129(2):933–52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11277-022-10164-8

3. Olawade DB, Wada OJ, David-Olawade AC, Kunonga E, Abaire O, Ling J. Using artificial intelligence to improve public health: a narrative review. Front Public Health. 2023 Oct;11:1196397. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1196397

4. Russell S, Norvig P. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, Global Edition 4th.Ed. (4th ed.). Pearson Education. 2021

5. O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014 Sep;89(9):1245–51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

6. Rahimi S, Khatooni M. Saturation in qualitative research: an evolutionary concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud Adv. 2024 Jan;6:100174. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnsa.2024.100174

7. Devers KJ. How will we know “good” qualitative research when we see it? Beginning the dialogue in health services research. Health Serv Res. 1999 Dec;34(5 Pt 2):1153–88.

8. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

9. Byrne D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Quant. 2022 Jun;56(3):1391–412. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

10. O’Connor C, Joffe H. Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines. Int J Qual Methods. 2020;19:19. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919899220

11. Lombard M, Snyder-Duch J, Bracken CC. Content Analysis in Mass Communication: Assessment and Reporting of Intercoder Reliability. Hum Commun Res. 2002 Oct;28(4):587–604. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00826.x

12. Ramakrishnan K, Abuhamad G, Chantry C, Diamond SP, Donelson P, Ebert L, et al. The AI Maturity Framework: A strategic guide to operationalize and scale enterprise AI solutions [Internet]Element AI; 2020.

13. Artificial Intelligence in the Public Sector. A Maturity Model | IBM Center for The Business of Government [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 22]. Available from: https://www.businessofgovernment.org/report/artificial-intelligence-public-sector-maturity-model

14. Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A, Blythe J, Neville AJ. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014 Sep;41(5):545–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.545-547

15. Noble H, Heale R. Triangulation in research, with examples. Evid Based Nurs. 2019 Jul;22(3):67–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2019-103145

16. Artificial Intelligence and Data Act [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 18]. Available from: https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/innovation-better-canada/en/artificial-intelligence-and-data-act

17. Bill 194, Strengthening Cyber Security and Building Trust in the Public Sector Act, 2024 - Legislative Assembly of Ontario [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.ola.org/en/legislative-business/bills/parliament-43/session-1/bill-194

18. Neumann O, Guirguis K, Steiner R. Exploring artificial intelligence adoption in public organizations: a comparative case study. Public Manage Rev. 2024 Jan;26(1):114–41. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2022.2048685

19. Fisher S, Rosella LC. Priorities for successful use of artificial intelligence by public health organizations: a literature review. BMC Public Health. 2022 Nov;22(1):2146. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14422-z

20. Esmaeilzadeh P. Challenges and strategies for wide-scale artificial intelligence (AI) deployment in healthcare practices: A perspective for healthcare organizations. Artif Intell Med. 2024 May;151:102861. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artmed.2024.102861

21. Riedemann L, Labonne M, Gilbert S. The path forward for large language models in medicine is open. NPJ Digit Med. 2024 Nov;7(1):339. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01344-w

22. Sachdeva S, Bhatia S, Al Harrasi A, Shah YA, Anwer K, Philip AK, et al. Unraveling the role of cloud computing in health care system and biomedical sciences. Heliyon. 2024 Apr;10(7):e29044. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29044

23. Kusunose M, Muto K. Public attitudes toward cloud computing and willingness to share personal health records (PHRs) and genome data for health care research in Japan. Hum Genome Var. 2023 Mar;10(1):11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41439-023-00240-1

24. Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82(4):581–629. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x

25. Siu EC, Levinton C, Brown AD. The Value of Performance Measurement in Promoting Improvements in Women’s Health. Healthc Policy. 2009 Nov;5(2):52–67. doi: https://doi.org/10.12927/hcpol.2013.21233

26. Kamyabi A, Iyamu I, Saini M, May C, McKee G, Choi A. Advocating for population health: the role of public health practitioners in the age of artificial intelligence. Can J Public Health. 2024 Jun;115(3):473–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-024-00881-x

27. Chan WW, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, Smith AC, Firebaugh ML, Fowler LA, DePietro B, et al. The Challenges in Designing a Prevention Chatbot for Eating Disorders: observational Study. JMIR Form Res. 2022 Jan;6(1):e28003. doi: https://doi.org/10.2196/28003

28. Chen RJ, Wang JJ, Williamson DF, Chen TY, Lipkova J, Lu MY, et al. Algorithmic fairness in artificial intelligence for medicine and healthcare. Nat Biomed Eng. 2023 Jun;7(6):719–42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-023-01056-8

29. Gentzel M. Biased Face Recognition Technology Used by Government: A Problem for Liberal Democracy. Philos Technol. 2021;34(4):1639–63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-021-00478-z

30. Vyas DA, Eisenstein LG, Jones DS. Hidden in Plain Sight - Reconsidering the Use of Race Correction in Clinical Algorithms. N Engl J Med. 2020 Aug;383(9):874–82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMms2004740

31. Koo C, Yang A, Welch C, Jadav V, Posch L, Thoreson N, et al. Validating racial and ethnic non-bias of artificial intelligence decision support for diagnostic breast ultrasound evaluation. J Med Imaging (Bellingham). 2023 Nov;10(6):061108. doi: https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JMI.10.6.061108

32. Perets O, Stagno E, Ben Yehuda E, McNichol M, Celi LA, Rappoport N, et al. Inherent Bias in Electronic Health Records: A Scoping Review of Sources of Bias. medRxiv [preprint]. 2024 Apr 12;2024.04.09.24305594. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.09.24305594

33. Abujaber AA, Nashwan AJ. Ethical framework for artificial intelligence in healthcare research: A path to integrity. World J Methodol. 2024 Sep;14(3):94071. doi: https://doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v14.i3.94071

34. Park HJ. Patient perspectives on informed consent for medical AI: A web-based experiment. Digit Health. 2024 Apr;10:20552076241247938. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076241247938

35. Panteli D, Adib K, Buttigieg S, Goiana-da-Silva F, Ladewig K, Azzopardi-Muscat N, et al. Artificial intelligence in public health: promises, challenges, and an agenda for policy makers and public health institutions. Lancet Public Health. 2025 May;10(5):e428–32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(25)00036-2

36. Responsible Use of Artificial Intelligence Directive | ontario.ca [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 23]. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/page/responsible-use-artificial-intelligence-directive

37. Braun V, Clarke V. Supporting best practice in reflexive thematic analysis reporting in Palliative Medicine: A review of published research and introduction to the Reflexive Thematic Analysis Reporting Guidelines (RTARG). Palliat Med. 2024 Jun;38(6):608–16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163241234800

38. Hou W, Ji Z. Comparing Large Language Models and Human Programmers for Generating Programming Code. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2025 Feb;12(8):e2412279. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202412279

39. Ahmed SK. The pillars of trustworthiness in qualitative research. J Med Surg Public Health. 2024 Apr;2:100051. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.glmedi.2024.100051

40. S4-Episode 9: Technology in the classroom: Digital education, privacy, and student well-being | Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 20]. Available from: https://www.ipc.on.ca/en/media-centre/podcast/s4-episode-9-technology-classroom-digital-education-privacy-and-student-well-being

41. Ye J, Woods D, Jordan N, Starren J. The role of artificial intelligence for the application of integrating electronic health records and patient-generated data in clinical decision support. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc. 2024 May;2024:459–67.

42. AI Strategy for the Federal Public Service 2025-2027: Priority - Canada.ca [Internet]. []. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/government/system/digital-government/digital-government-innovations/responsible-use-ai/gc-ai-strategy-priority-areas.html

The appendices are available for download as separate files at https://doi.org/10.57187/4942.