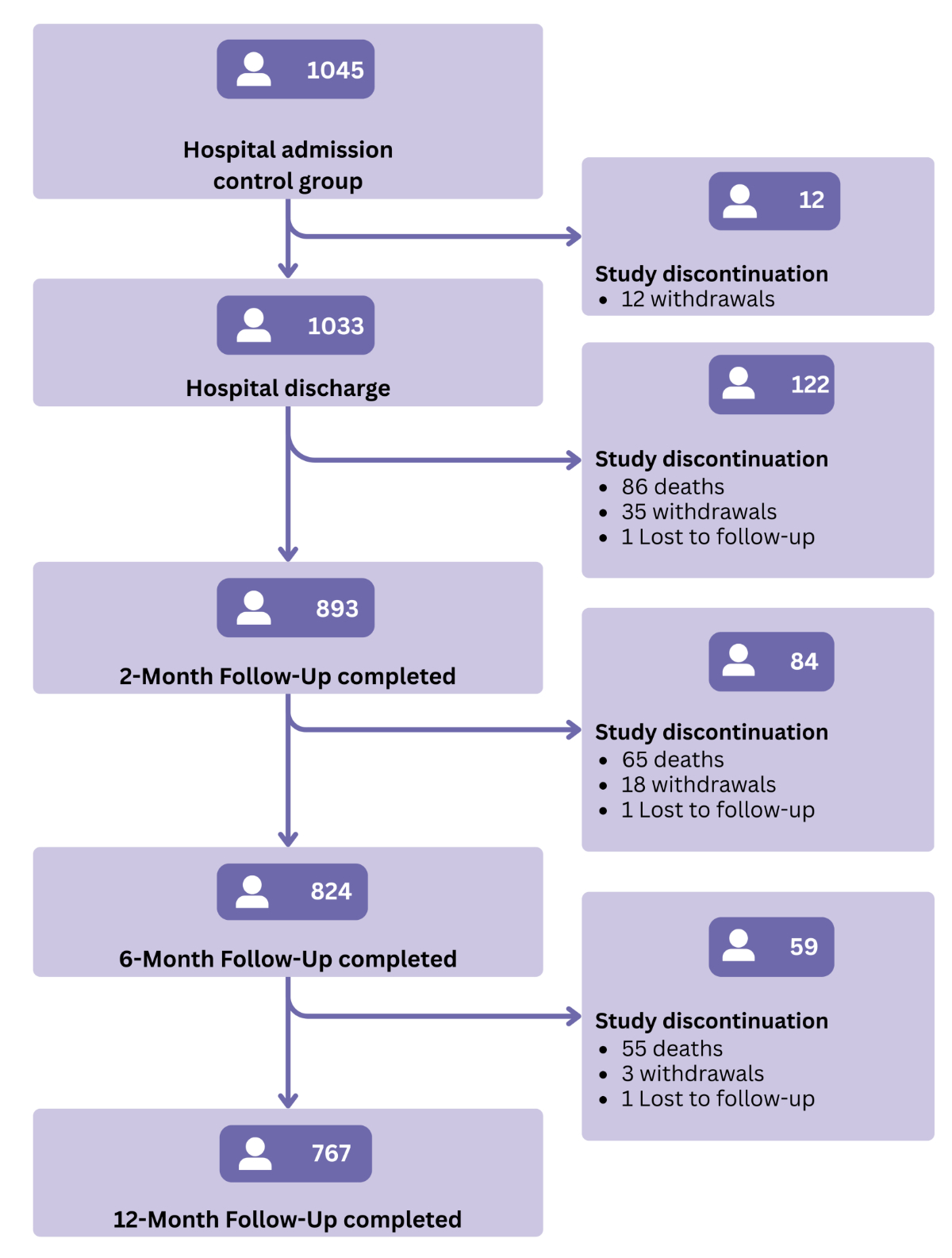

Flowchart of participants in the control group of the OPERAM trial from index hospital admission to 12-month follow-up.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/4892

Polypharmacy, commonly defined as the use of five or more long-term medications, is a growing issue among older adults. Its prevalence is increasing, due to rising multimorbidity associated with population ageing and the implementation of disease-specific guidelines that are mostly not developed for multimorbid older adults [1–4]. While polypharmacy in older people can be appropriate, it is consistently associated with prescribing of potentially inappropriate medications [5–7]. Potentially inappropriate medications are defined as medications for which the risk of an adverse event outweighs their clinical benefit or which are prescribed without a clinical indication [8]. Widely known tools to identify potentially inappropriate medications include the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) Beers Criteria and the STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions) criteria [9, 10]. In addition to increased risk of potentially inappropriate medications, polypharmacy also increases the likelihood of potential prescribing omissions, where clinically indicated medications are not prescribed [11, 12]. Potential prescribing omissions can be assessed using START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment) criteria. Developed in Europe, STOPP/START criteria are validated instruments endorsed by several national guidelines and are widely used to improve prescribing quality in older adults [10]. Potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions, which can be grouped together as potentially inappropriate prescriptions are important to detect as they may contribute to adverse health outcomes, such as adverse drug events, falls, cognitive decline and functional impairment [10, 13]. These issues lead to higher healthcare utilisation and costs [14–16]. Use of STOPP/START criteria may be effective in improving prescribing quality and reducing falls, hospital length of stay, healthcare visits and medication costs [17]. Although these criteria were initially developed for community-dwelling older adults, recent research has shown that they can also help detect potentially inappropriate prescriptions in institutionalised and hospitalised patients [18, 19]. Previous research studies have largely focused on the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescriptions in older adults, often within specific groups or settings, or patients with specific diseases (e.g. patients with Alzheimer’s disease, community-dwelling patients or nursing home residents) and these studies were mostly cross-sectional [20, 21]. Although several studies have examined temporal trends, most have employed repeated cross-sectional designs and focused on overall prevalence [14, 22–27]. However, little is known about longitudinal changes in potentially inappropriate prescriptions within the same patient population of multimorbid older adults with polypharmacy, and about how individual potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions differ across care settings and evolve over time. To address these knowledge gaps, we studied patterns of potentially inappropriate prescriptions in older multimorbid adults with polypharmacy across four European countries over a prospective 12-month period. Using data from the multi-country OPERAM trial (“OPtimising thERapy to prevent Avoidable hospital admissions in Multimorbid older adults”), we compared the prevalence and types of potentially inappropriate prescriptions across predefined patient subgroups by living environment (community-dwelling versus nursing home) and medication burden (polypharmacy versus hyperpolypharmacy) at hospital admission, examined associated patient characteristics, assessed longitudinal changes over time and explored factors associated with these changes [28].

This study employed a longitudinal, exploratory design using data from the OPERAM trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02986425). OPERAM was a multi-country, partially blinded cluster-randomised controlled trial, which investigated the effects of hospital pharmacotherapy optimisation on drug-related hospital admissions in multimorbid (≥3 chronic conditions), older (≥70 years) adults with polypharmacy (≥5 chronic medications). It compared a structured pharmacotherapy optimisation intervention performed by a doctor and a pharmacist, with the support of a clinical decision software system (STRIPA), to usual care [29, 30]. Patients were recruited in medical and surgical wards of four European tertiary-care hospitals (Bern, Brussels, Cork, Utrecht).

OPERAM was approved by the independent research ethics committees at each site (lead ethics committee: Cantonal Ethics Committee Bern, Switzerland: ID 2016-01200; Medical Research Ethics Committee Utrecht, Netherlands: ID 15-522/D; Comité d’Éthique Hospitalo-Facultaire Saint-Luc-UCL: 2016/20JUL/347–Belgian registration No: B403201629175; Cork University Teaching Hospitals Clinical Ethics Committee, Cork, Republic of Ireland: ID ECM 4 (o) 07/02/17), with Swissmedic as the responsible regulatory authority.

For this analysis, we included all 1045 patients who had been randomised to the OPERAM control group and were receiving medication-related care as delivered at that time at the four participating hospitals. Focusing on the combined control group allowed us to examine real-world prescribing practices and outcomes without the influence of the systematic pharmacotherapy optimisation intervention, which influenced prescribing practices in the intervention group [28–30].

We used data collected during the OPERAM trial at multiple time points: hospital admission, discharge, and 2-, 6- and 12-month post-discharge follow-up. Participants were enrolled between December 2016 and October 2018, and follow-up assessments were conducted via telephone interviews by blinded researchers. The START criteria (v2) were used to detect potential prescribing omissions and the STOPP criteria (v2) to detect potentially inappropriate medications [10]. The present study could assess 30 of the 34 START criteria and 63 of the 80 STOPP criteria; the remaining criteria require laboratory and clinical data that were not available and they were therefore excluded. A detailed list of the included and excluded criteria is provided in tables S1–S3 in the appendix. The assessment of potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions was conducted using an R statistical package developed specifically for the OPERAM trial in collaboration with UCLouvain, Belgium and the University of Ioannina, Greece (available at https://github.com/agapiospanos/StartStopp) [31, 32].

The study outcomes were a priori defined as the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescriptions at hospital admission, differences in potentially inappropriate prescriptions between living settings (nursing home versus community-dwelling) and number of medications (polypharmacy [5–9 medications] versus hyperpolypharmacy [≥10 medications]), changes in potentially inappropriate prescriptions over the 12-month follow-up and factors associated with potentially inappropriate prescriptions.

Baseline characteristics were summarised using descriptive statistics. Normality for each variable was assessed using visual inspection of histograms and the Shapiro–Wilk test, which indicated non-normal data distribution; therefore, continuous variables were reported as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) and categorical variables as absolute frequencies with percentages.

First, we described and compared the median number and prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescriptions at admission between living settings (nursing home versus community-dwelling) and number of medications (polypharmacy [5–9 medications] versus hyperpolypharmacy [≥10 medications]) using Mann–Whitney U tests and Pearson’s chi-squared tests, as appropriate. Additionally, the prevalence of the ten most frequent potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions at admission was compared across these subgroups by calculating the percentage of patients meeting each criterion.

Second, we performed multivariable negative binomial regressions to identify patient characteristics associated with the number of potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions at admission. Independent variables were selected based on previously published peer-reviewed literature and included nursing home residency (yes/no), age group (70–74, 75–84, ≥85 years), cognitive impairment (yes/no), history of fall within the past year (yes/no), sex (male/female), hyperpolypharmacy (≥10 medications, yes/no) and the number of comorbidities (continuous) [7, 33–35]. To test for non-linearity, the association between the number of comorbidities and the outcome was assessed using quadratic and fractional polynomial terms, with model fit compared by log-likelihood and deviance. Results are reported as incidence rate ratios (IRRs) with 95% confidence intervals.

Third, we investigated changes in potentially inappropriate prescriptions over the 12-month follow-up period. We calculated, for each patient, whether the number of potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions increased, decreased or did not change between admission and discharge, and 2-month, 6-month and 12-month follow-up. Individual changes were derived as the within-patient difference in total counts of potentially inappropriate prescriptions between admission and subsequent assessments, and patients were categorised into one of three groups for potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions separately: increase, decrease or no change. We further calculated the proportion of patients with at least one potentially inappropriate medication or potential prescribing omission at the respective follow-ups and assessed changes from admission using McNemar’s tests. This part of the analysis included only participants who completed the respective follow-ups (discharge n = 1033; 2-month n = 893; 6-month n = 824; 12-month n = 767; figure 1). Furthermore, we examined changes in the prevalence of the ten most frequent potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions over time, calculating relative differences and using McNemar’s tests.

Flowchart of participants in the control group of the OPERAM trial from index hospital admission to 12-month follow-up.

Finally, we conducted multivariable logistic regression analyses using the same independent variables as in the admission model to identify factors associated with any increase or decrease in the number of potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions from admission to discharge and to the 12-month follow-up. Outcomes were modelled as binary (increase versus no increase and decrease versus no decrease). Results are reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals. Missing data for covariates of the regression models were minimal (<1% for all variables) and were handled by complete-case analysis (n = 1037 for admission; n = 1030 for discharge; n = 766 for 12-month models). As a sensitivity analysis, we additionally performed multinomial logistic regression to simultaneously estimate factors associated with increases and decreases in potentially inappropriate prescriptions, using “no change” as the reference category, and conducted Fine-Gray competing risk regression models to account for death as a competing event when assessing time to first increase or decrease in potentially inappropriate prescriptions within 12 months. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 16 (StataCorp®, College Station, TX, USA) and R version 4.1.2 (Free Software Foundation, Inc., Boston, MA, USA). Within R, we used the packages dplyr (1.1.4; MIT), tidyr (1.3.1; MIT), openxlsx (4.2.7; MIT), haven (2.5.5; GPL-3), readr (2.1.5; MIT) and stringr (1.5.1; MIT) (all from CRAN). For table export in Stata, we employed the user-written package estout/esttab (SSC; GPL). All analyses were considered exploratory and results are presented descriptively, with 95% CIs reported where appropriate.

A total of 1045 patients were included at hospital admission. Follow-up data were available for 1033/1045 (98.9%) patients at hospital discharge, 893/1045 (85.4%) at 2-month follow-up, 824/1045 (78.8%) at 6 months and 767/1045 (73.4%) at 12 months (figure 1). The majority of dropouts (206/277 [74%]) were due to death.

The median age of patients was 79 years (IQR 74–84) and 453 patients (43.3%) were female. The median number of comorbidities was 10 (IQR 8–15) and the median number of prescribed daily long-term medications was 9 (IQR 7–12); hyperpolypharmacy was observed in 47.3% of patients. A total of 114 patients (11.0%) resided in a nursing home prior to admission. The nursing home residents were older than community-dwelling patients (median 82 [IQR 77–87] versus 78 [IQR 74–84] years). A total of 39.0% of patients had experienced at least one fall in the year preceding admission. At admission, 88.3% of patients had at least one potentially inappropriate prescription. Specifically, 63.5% had at least one potentially inappropriate medication and 72.1% had at least one potential prescribing omission (table 1).

Table 1Baseline characteristics and overall prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications/potential prescribing omissions at hospital admission among multimorbid older adults with polypharmacy.

| Variable | Values (n = 1045) |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 79 (74–84) |

| Female, n (%) | 453 (43.3%) |

| Patients per trial site, n (%) | |

| … Bern, Switzerland | 376 (36.0%) |

| … Cork, Republic of Ireland | 208 (19.9%) |

| … Louvain, Belgium | 238 (22.8%) |

| … Utrecht, Netherlands | 223 (21.3%) |

| Nº of comorbiditiesa, median (IQR) | 10 (8–15) |

| … Bern, Switzerland | 15 (11–22) |

| … Cork, Republic of Ireland | 9 (7–11.5) |

| … Louvain, Belgium | 10 (7–14) |

| … Utrecht, Netherlands | 8 (6–10) |

| Nº of drugsb, median (IQR) | 9 (7–12) |

| … Bern, Switzerland | 10 (7–13) |

| … Cork, Republic of Ireland | 9 (7–12) |

| … Louvain, Belgium | 8 (6–10) |

| … Utrecht, Netherlands | 10 (8–14) |

| Patients with hyperpolypharmacyc (≥10 medications), n (%) | 494 (47.3%) |

| Living in nursing home (in the last 6 months before the index admission)d, n (%) | 114 (11.0%) |

| Any fall in the year preceding index admissione, n (%) | 405 (39.0%) |

| Cognitive impairmentf (e.g. dementia), n (%) | 80 (7.7%) |

| Patients with ≥1 PIM or PPOg, n (%) | 923 (88.3%) |

| Patients with ≥1 PIMg, n (%) | 664 (63.5%) |

| Patients with ≥1 PPOg, n (%) | 754 (72.1%) |

| Nº of PIMs or PPOs per patientg, median (IQR) | 2 (1–4) |

| Nº of PIMs per patientg, median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) |

| Nº of PPOs per patientg, median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) |

Missing data: ᵃ n = 1 (0.1%), ᵇ n = 1 (0.1%), ᶜ n = 1 (0.1%), ᵈ n = 5 (0.5%), ᵉ n = 7 (0.7%), ᶠ n = 1 (0.1%), ᵍ n = 1 (0.1%).

Abbreviations: IQR: interquartile range; PIM: potentially inappropriate medication; PPO: potential prescribing omission.

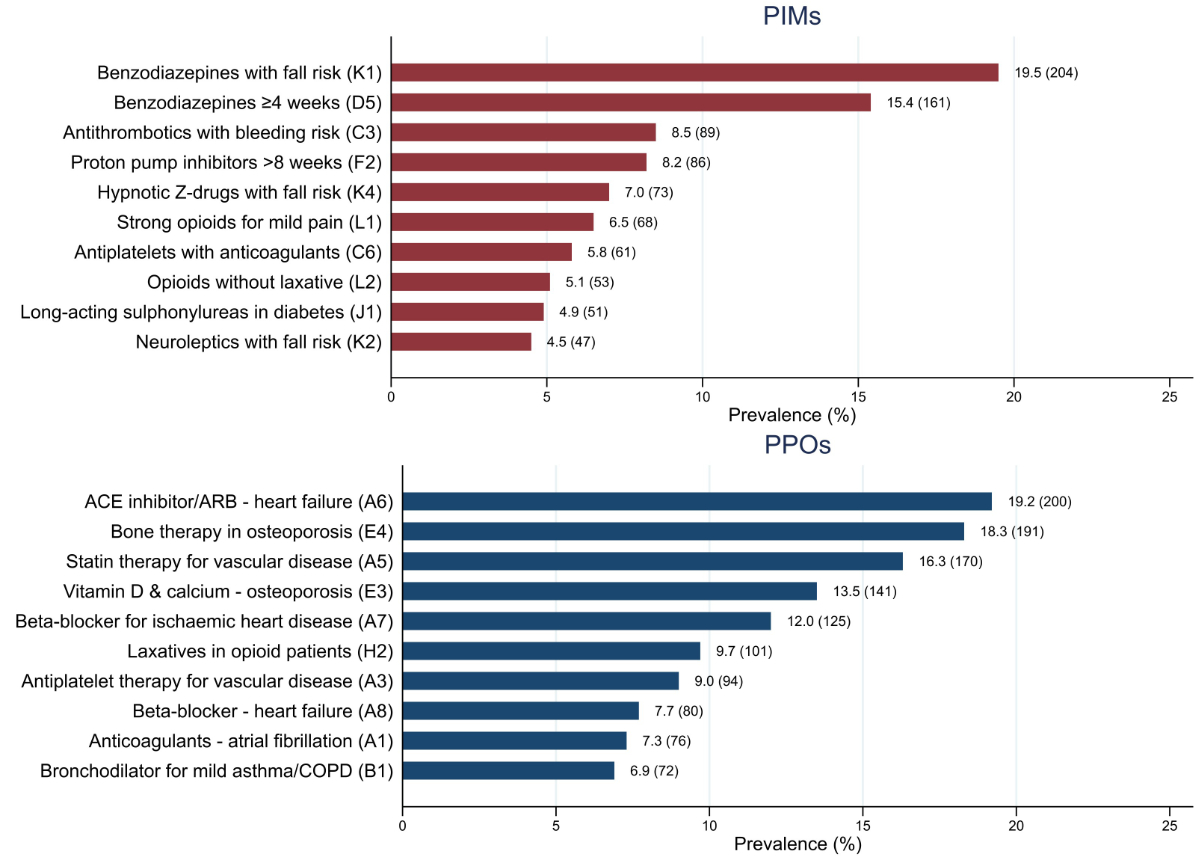

The two most common potentially inappropriate medications were the use of benzodiazepines in patients with risk of falling and long-term benzodiazepine use. The two most frequent potential prescribing omissions were the omission of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) in patients with heart failure and non-prescription of bone-protective therapy in patients with osteoporosis (figure 2, table S4). The prevalence of all potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions is presented in tables S1 and S2 in the appendix.

Figure 1Prevalence of the ten most frequent potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions at admission. Values represent the percentage of patients meeting each criterion, with absolute numbers shown in brackets. Labels such as “Benzodiazepines with fall risk (K1)” refer to the corresponding STOPP/START criterion, where “K1” indicates the specific criterion number as defined in the validated STOPP/START version [10]. Abbreviations: ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker; PIM: potentially inappropriate medication; PPO: potential prescribing omission.

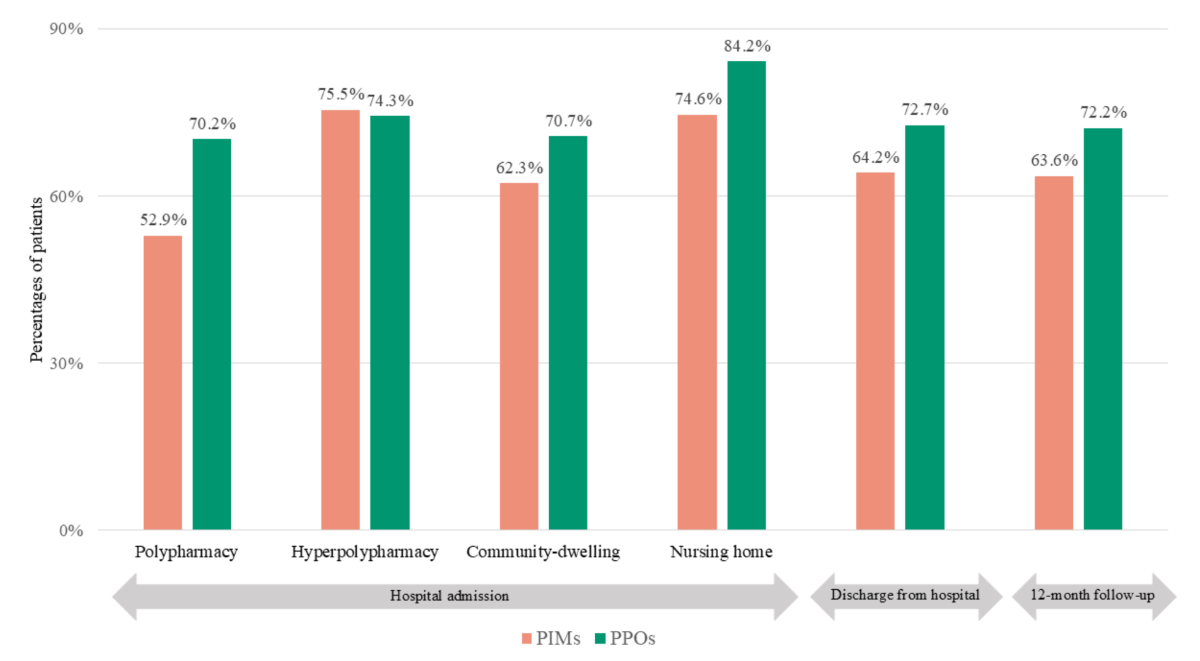

At admission, nursing home residents had a higher prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescriptions compared to community-dwelling patients (figure 3, tables S5 and S6). The greatest difference in potentially inappropriate medication prevalence was observed in the prolonged use of proton-pump inhibitors (figure S1 in the appendix). Among potential prescribing omissions, the greatest difference concerned the potential omission of statin therapy despite known cardiovascular disease (figure S2).

Figure 2 Percentages of patients with at least one potentially inappropriate medication or potential prescribing omission. Values represent percentages of patients with at least one potentially inappropriate medication or potential prescribing omission. Polypharmacy is defined as the use of 5–9 long-term medications; hyperpolypharmacy as the use of ≥10 long-term medications. Abbreviations: PIM: potentially inappropriate medication; PPO: potential prescribing omission.

Patients with hyperpolypharmacy had a higher prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications than those with polypharmacy. Conversely, the prevalence of potential prescribing omissions was not significantly different between the groups (figure 3, tables S5 and S6). The largest difference in potentially inappropriate medications was observed for prevalence of benzodiazepines in patients with risk of falling (figure S1). Among potential prescribing omissions, the greatest difference was found in the omission of laxatives in patients receiving opioid therapy (figure S2).

Multivariable negative binomial regression analysis showed that hyperpolypharmacy, female sex and cognitive impairment were associated with a higher number of potentially inappropriate medications, while nursing home residency, older age, a history of falls, female sex and each additional comorbidity were associated with a higher number of potential prescribing omissions. In contrast, hyperpolypharmacy was associated with fewer potential prescribing omissions (table 2). No evidence of non-linearity was observed for the number of comorbidities. Neither the quadratic nor the fractional polynomial terms improved model fit; thus, a linear specification was retained in the final models.

Table 2Negative binomial regression of the number of potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions at hospital admission (n = 1037).

| Variable | Number of PIMs | Number of PPOs | |||

| IRR | 95% CI | IRR | 95% CI | ||

| Nursing home residency | 1.08 | 0.89, 1.31 | 1.18 | 1.00, 1.39 | |

| Hyperpolypharmacy (≥10 medications) | 1.54 | 1.35, 1.76 | 0.89 | 0.79, 1.00 | |

| Cognitive impairment | 1.44 | 1.16, 1.79 | 0.96 | 0.79, 1.16 | |

| Age group | 70–74 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 75–84 | 1.02 | 0.88, 1.19 | 1.17 | 1.02, 1.34 | |

| ≥85 | 0.95 | 0.79, 1.13 | 1.33 | 1.14, 1.55 | |

| Any fall(s) in the last year | 1.09 | 0.96, 1.24 | 1.22 | 1.09, 1.36 | |

| Number of comorbidities | 1.00 | 0.99, 1.01 | 1.03 | 1.03, 1.04 | |

| Sex | Male | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 1.19 | 1.05, 1.35 | 1.14 | 1.02, 1.27 | |

Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; IRR: incidence rate ratio; PIM: potentially inappropriate medication; PPO: potential prescribing omission.

Continuous variables (number of comorbidities) were modelled per one-unit increase; IRRs indicate the relative change in potentially inappropriate medications or potential prescribing omissions per additional comorbidity. Analyses were based on complete cases (n = 1037/1045 for admission). Missing values for covariates were minimal: nursing home residency: n = 5 (0.5%), hyperpolypharmacy: n = 1 (0.1%), cognitive impairment: n = 1 (0.1%), falls in the last year: n = 7 (0.7%), number of comorbidities: n = 1 (0.1%), age group and sex: n = 0.

During the index hospitalisation and the 12-month follow-up period, the overall prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions remained generally stable (table S6). However, analyses of individual patient data indicated variation over time, with many patients experiencing either an increase or a decrease in their number of potentially inappropriate medications or potential prescribing omissions over time (figure S3). The prevalence of specific potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions changed substantially over time (figure 4).

Figure 3Longitudinal trends of the ten most frequent potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions. Values represent percentages of patients meeting each criterion. Labels such as “Benzodiazepines (K1)” refer to the corresponding STOPP/START criterion, where “K1” indicates the specific criterion number as defined in the validated STOPP/START version [10]. Abbreviations: ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; PIM: potentially inappropriate medication; PPI: proton-pump inhibitor; PPO: potential prescribing omission.

Regarding potentially inappropriate medications, the prevalence of neuroleptic drugs in patients with a history of falls increased over time with a relative increase of 55.6% from admission to 12 months. Conversely, the prevalence of long-term benzodiazepine use initially rose from admission to discharge but then declined at 12 months leading to a relative reduction of 27.3%.

Among potential prescribing omissions, the prevalence of omitted vitamin D and calcium supplementation in patients with osteoporosis showed the largest relative increase from admission to 12-month follow-up. In contrast, the greatest relative decrease was observed for the omission of anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. Additionally, the omission of ACE inhibitors in patients with heart failure increased from admission to discharge and remained elevated at 12 months.

Multivariable logistic regression identified several patient characteristics associated with changes in potentially inappropriate prescriptions over time (tables 3 and 4).

Table 3Multivariable logistic regression of increase and decrease in potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions from admission to discharge (n = 1030). Binary outcomes reflect whether patients had an increase or decrease in the total number of potentially inappropriate medications or potential prescribing omissions compared to admission.

| Admission to discharge | Increase in PIMs | Decrease in PIMs | Increase in PPOs | Decrease in PPOs | |||||

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Nursing home residency | 1.26 | 0.76, 2.09 | 1.12 | 0.67, 1.87 | 1.37 | 0.85, 2.22 | 1.31 | 0.77, 2.24 | |

| Hyperpolypharmacy (≥10 medications) | 0.58 | 0.42, 0.82 | 1.82 | 1.27, 2.61 | 1.52 | 1.09, 2.12 | 0.46 | 0.32, 0.67 | |

| Cognitive impairment | 1.01 | 0.56, 1.82 | 1.55 | 0.88, 2.72 | 1.53 | 0.89, 2.63 | 0.81 | 0.42, 1.56 | |

| Age group | 70–74 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 75–84 | 0.96 | 0.66, 1.39 | 1.04 | 0.67, 1.59 | 0.76 | 0.52, 1.10 | 1.71 | 1.10, 2.67 | |

| ≥85 | 0.88 | 0.56, 1.38 | 1.62 | 1.00, 2.61 | 0.92 | 0.59, 1.44 | 1.61 | 0.96, 2.69 | |

| Any fall(s) in the last year | 1.55 | 1.12, 2.15 | 1.22 | 0.86, 1.73 | 1.19 | 0.85, 1.65 | 1.54 | 1.08, 2.18 | |

| Number of comorbidities | 1.01 | 0.99, 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.00, 1.05 | 1.02 | 1.00, 1.04 | 1.01 | 0.98, 1.04 | |

| Sex | Male | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Female | 1.24 | 0.90, 1.70 | 0.99 | 0.70, 1.41 | 0.75 | 0.54, 1.04 | 1.33 | 0.94, 1.88 | |

Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; IRR: incidence rate ratio; OR: odds ratio; PIM: potentially inappropriate medication; PPO: potential prescribing omission.

Continuous variables (number of comorbidities) were modelled per one-unit increase; ORs indicate the relative change in potentially inappropriate medications or potential prescribing omissions per additional comorbidity. Analyses were based on complete cases (n = 1030/1045 for discharge). Missing values for covariates were minimal: nursing home residency: n = 5 (0.5%), hyperpolypharmacy: n = 1 (0.1%), cognitive impairment: n = 1 (0.1%), falls in the last year: n = 7 (0.7%), number of comorbidities: n = 1 (0.1%), age group and sex: n = 0.

Table 4Multivariable logistic regression of increase and decrease in potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions from admission to 12-month follow-up (n = 766). Binary outcomes reflect whether patients had an increase or decrease in the number of potentially inappropriate medications or potential prescribing omissions compared to admission.

| Admission to 12-month follow-up | Increase in PIMs | Decrease in PIMs | Increase in PPOs | Decrease in PPOs | |||||

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Nursing home residency | 1.94 | 1.12, 3.36 | 1.73 | 0.99, 3.01 | 1.01 | 0.56, 1.82 | 1.40 | 0.77, 2.56 | |

| Hyperpolypharmacy(≥10 medications) | 0.83 | 0.58, 1.20 | 1.93 | 1.36, 2.75 | 1.71 | 1.20, 2.42 | 0.51 | 0.35, 0.74 | |

| Cognitive impairment | 1.50 | 0.83, 2.72 | 0.94 | 0.49, 1.80 | 1.26 | 0.68, 2.34 | 0.63 | 0.31, 1.28 | |

| Age group | 70–74 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 75–84 | 1.22 | 0.81, 1.85 | 1.23 | 0.83, 1.84 | 0.99 | 0.67, 1.46 | 1.37 | 0.91, 2.07 | |

| ≥85 | 1.13 | 0.67, 1.89 | 0.94 | 0.55, 1.58 | 0.81 | 0.48, 1.35 | 1.11 | 0.65, 1.89 | |

| Any fall(s) in the last year | 1.10 | 0.76, 1.58 | 1.01 | 0.71, 1.45 | 0.81 | 0.56, 1.16 | 1.52 | 1.06, 2.18 | |

| Number of comorbidities | 1.02 | 0.99, 1.05 | 1.00 | 0.97, 1.02 | 1.03 | 1.01, 1.06 | 1.00 | 0.97, 1.03 | |

| Sex | Male | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Female | 1.40 | 0.99, 1.99 | 1.40 | 0.99, 1.98 | 1.23 | 0.87, 1.74 | 1.16 | 0.82, 1.66 | |

Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; PIM: potentially inappropriate medication; PPO: potential prescribing omission.

Continuous variables (number of comorbidities) were modelled per one-unit increase; ORs indicate the relative change in potentially inappropriate medications or potential prescribing omissions per additional comorbidity. Analyses were based on complete cases (n = 766/1045 for 12-month follow-up). Missing values for covariates were minimal: nursing home residency: n = 5 (0.5%), hyperpolypharmacy: n = 1 (0.1%), cognitive impairment: n = 1 (0.1%), falls in the last year: n = 7 (0.7%), number of comorbidities: n = 1 (0.1%), age group and sex: n = 0.

Nursing home residency was associated with an increase in potentially inappropriate medications at 12 months. Hyperpolypharmacy was associated with an increase in potential prescribing omissions and a decrease in potentially inappropriate medications at both discharge and 12 months. Patients aged 75–84 years were more likely to experience a decrease in potential prescribing omissions during hospitalisation compared to those aged 70–74 years. A history of falls was associated with a decrease in potential prescribing omissions at discharge and at 12 months, but also an increase in potentially inappropriate medications at discharge. A higher number of comorbidities was associated with an increase in potential prescribing omissions at 12 months. The multinomial sensitivity analyses showed consistent results, with stronger associations for nursing home residency and female sex, and slightly weaker effects for hyperpolypharmacy (table S7). Similarly, the results of the Fine-Gray competing risk regression were consistent with those of the logistic regression, showing slightly attenuated effect estimates for nursing home residency and hyperpolypharmacy after accounting for death as a competing event and event timing (table S8).

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the prevalence, changes and determinants of potentially inappropriate prescriptions in older, multimorbid adults with polypharmacy across four European countries. At hospital admission, 88.3% of patients had at least one potentially inappropriate medication or potential prescribing omission, indicating that potentially inappropriate prescriptions in this at-risk population are highly prevalent, especially in older adults with hyperpolypharmacy (52.9% of whom had at least one potentially inappropriate medication and 70.2% at least one potential prescribing omission) and those living in nursing homes (74.6% with at least one potentially inappropriate medication; 84.2% with at least one potential prescribing omission). Moreover, our analyses indicated variability in the total number of potentially inappropriate prescriptions per patient over the 12-month follow-up period, although the overall prevalence remained consistently high.

The high prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescriptions observed in our study aligns with existing literature and is most probably a consequence of the older age, medication burden and multimorbidity of our study population. A previous systematic review reported potentially inappropriate medication and potential prescribing omission prevalence rates of 51.8% and 64.0%, respectively, in hospitalised patients aged ≥65 years [19]. The even higher prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions identified in the present study are consistent with findings from studies involving more-comparable populations [5, 14, 36]. The most frequent potential prescribing omissions were omissions of ACE inhibitors or ARBs in patients with heart failure and of bone anti-resorptive therapy in osteoporosis; benzodiazepines were the most common potentially inappropriate medications, consistent with previous findings [19, 26].

Nursing home residents had a higher prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions compared to community-dwelling patients, and, as expected, hyperpolypharmacy was associated with more potentially inappropriate medications, reflecting established associations reported in the literature [5–7, 18, 33, 34, 37, 38]. In addition to frailty and multimorbidity, the higher prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescriptions in nursing home residents may also be partly explained by the fact that they were older than community-dwelling patients in our study population.

The most pronounced difference in potential prescribing omission prevalence between nursing home and community-dwelling patients was observed for statin omission in patients with cardiovascular disease. The high rate of statin omissions in this population may reflect rational prescribing in frail patients, based on poor life expectancy and individualised risk-benefit assessments. However, our dataset did not allow us to draw conclusions regarding the clinical rationale relating to possible decisions to deprescribe or whether inappropriate prescription omission may have resulted in technical potential prescribing omissions.

Regarding potentially inappropriate medications, the greatest difference was found in the prolonged use of proton-pump inhibitors, highlighting the high prevalence of non-evidence-based proton-pump inhibitor prescriptions in nursing homes [39]. This may reflect lack of systematic medication review in nursing homes, where medications initially prescribed for a specific indication may not be reassessed or discontinued after the recommended duration.

Our analysis identified several factors associated with the number of potentially inappropriate prescriptions at admission and their increase or decrease over time. Nursing home residency was associated with a higher potential prescribing omission prevalence at admission and increasing potentially inappropriate medications over time, consistent with previous research reporting high and even rising rates of potentially inappropriate prescriptions in nursing homes [18, 40]. Patients with cognitive impairment were at higher risk for potentially inappropriate medications at admission likely due to the frequent use of centrally acting drugs in this population [6, 33, 41]. A history of falls was also associated with more potential prescribing omissions at hospital admission, possibly driven by underuse of osteoprotective medications – a frequent omission also highlighted in our study. While the literature indicates that a higher number of potentially inappropriate medications is linked to an increased risk of falls, it remains unclear whether a history of falls itself is a risk factor for potentially inappropriate prescriptions [13, 42].

Hyperpolypharmacy being associated with more potentially inappropriate medications and fewer potential prescribing omissions at admission, reinforces the well-established and complex relationship between hyperpolypharmacy and potentially inappropriate prescriptions [25, 33, 43, 44]. While the observed association between hyperpolypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication reduction over time likely reflects deprescribing efforts in patients with high medication burden, the association with increasing potential prescribing omissions over time, consistent with previous evidence, raises concern [45, 46]. These findings suggest that efforts to reduce inappropriate medications may inadvertently lead to prescription omissions, strengthening the argument for routine medication reviews addressing both over- and underprescribing, particularly in patients with hyperpolypharmacy.

Female sex was associated with higher prevalences of both potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions, consistent with prior evidence attributing this to a multifactorial interplay of biological, clinical and sociocultural factors, including higher psychotropic drug use among women than men [6, 7, 34, 46–50]. Older age and a greater number of comorbidities were linked to a greater number of potential prescribing omissions at hospital admission, which is consistent with previous research [33, 34, 46, 51]. In older and multimorbid patients, clinical guidelines may be difficult to implement in full, leading to omissions that are not technically inappropriate but might represent pragmatic clinical prioritisation, aiming to avoid drug-drug and drug-disease interactions [3].

Evidence on longitudinal trends in potentially inappropriate prescriptions is mixed. Some studies report rising prevalences of potentially inappropriate prescriptions over time, others find little or no change, consistent with our findings [14, 22, 23, 25, 45, 46, 52–55]. Hospitalisation has been recognised as an opportunity to improve potentially inappropriate prescriptions, particularly in the context of structured interventions [27, 56]. However, in our study, which evaluated standard of care, no consistent improvement in potentially inappropriate prescriptions was observed.

Our findings show that while the overall prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescriptions appears stable over time, this masks potentially individual-level variability, with many patients experiencing increases or decreases in potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions. However, identifying which specific potentially inappropriate prescriptions changed per patient was beyond the scope of this study and should be addressed in future research. Moreover, specific potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions fluctuated considerably. Notably, the omission of ACE inhibitors or ARBs in patients with systolic heart failure increased over time. This may be partly attributable to new diagnoses made during hospitalisation, where initiation of treatment was deferred due to acute clinical circumstances – such as hypotension or renal impairment – and subsequently not initiated or restarted in the outpatient setting. In contrast, inappropriate benzodiazepine use declined over the same period, likely reflecting increased awareness of their classification as potentially inappropriate medications and growing efforts to promote medication optimisation in older adults – a trend also observed in the literature [25, 53, 55, 57].

Interestingly, despite the decline in benzodiazepine use, a converse increase in prevalence of neuroleptic drug prescriptions was observed over the follow-up period. These opposing trends may suggest a compensatory shift in prescribing patterns, a phenomenon previously described in the literature [58, 59]. Such medication substitution effects highlight the need for deprescribing strategies that address medication classes comprehensively.

Our findings suggest that static prevalence rates may not adequately reflect the dynamic and complex nature of prescribing in older patients. As different potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions vary in their clinical relevance, shifts in their type and composition over time could have more meaningful implications for patient outcomes than the overall prevalence would suggest. These observations support the value of individualised, longitudinal medication reviews – particularly in patients at higher risk – focusing on the most clinically relevant potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions. Future research may benefit from incorporating patient-level trajectories and criterion-specific patterns alongside cross-sectional assessments.

This study has several strengths. Firstly, the use of a large, multi-country dataset encompassing four European countries enhances the generalisability of the findings. Data collection was prospective, standardised and nearly complete, contributing to high methodological quality. Furthermore, the broad inclusion criteria support the external validity of our findings. Secondly, the 12-month follow-up of the same patient sample enabled a rare assessment of prescribing trends over time, capturing fluctuations in potentially inappropriate prescriptions. Thirdly, the inclusion of both community-dwelling and nursing home residents offers valuable insight into setting-specific prescribing practices.

Some study limitations should also be acknowledged. Firstly, given the exploratory nature of this study and the large number of comparisons, statistical significance should be interpreted cautiously and all analyses were descriptive and hypothesis-generating. Secondly, not all STOPP/START criteria could be applied due to incomplete clinical or laboratory data. Thirdly, as changes in potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions over time were analysed as binary outcomes in the regression model, the analyses did not capture the full spectrum or magnitude of change, although this was explored in sensitivity analyses using multinomial logistic regression, which showed similar results. In addition, we did not assess which specific potentially inappropriate prescriptions were newly identified or discontinued between time points, nor did we perform item-level transition analyses that would depict such criterion-level changes. Finally, individual prescribing decisions based on clinical judgment or patient preferences could not be assessed, as such contextual information was not captured in the dataset.

Potentially inappropriate prescriptions are common among older, multimorbid adults with polypharmacy and the overall prevalence remains largely unchanged over a 12-month follow-up interval. This apparent stability conceals potential dynamic shifts at an individual patient level and in specific potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions, which likely vary in clinical relevance and impact. The substantial burden of potentially inappropriate prescriptions underscores the need for continuous, structured medication reviews in multimorbid older people exposed to polypharmacy. Such reviews should address both over- and underprescribing. Targeting high-risk groups – such as nursing home residents, individuals with hyperpolypharmacy, advanced age or cognitive impairment – and focusing on the most variable and clinically relevant potentially inappropriate prescriptions may enhance intervention effectiveness. Future research should move beyond aggregate prevalence metrics and explore longitudinal, patient-level trajectories of key potentially inappropriate medications and potential prescribing omissions to identify modifiable targets and inform more precise, individualised interventions that improve prescribing quality.

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data will be made available for scientific purposes for researchers whose proposed use of the data has been approved by the OPERAM publication committee. The analytical code used for this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributions: Katharina Tabea Jungo and Nicolas Rodondi conceived the project. Jonathan Huschka and Carole E. Aubert conducted the project, and analysed and interpreted the data. Jonathan Huschka wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Carole E. Aubert closely supervised manuscript writing. All authors critically revised the manuscript and have approved its final version for publication.

This work is part of the project “OPERAM: OPtimising thERapy to prevent Avoidable hospital admissions in the Multimorbid elderly”, supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement number 634238, and by the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research, and Innovation (SERI) under contract number 15.0137. Jonathan Huschka was partly funded by the project “Discontinuing Statins in Multimorbid Older Adults without Cardiovascular Disease (STREAM)” supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) under grant agreement number IICT 33IC30‐193052 (to Prof. Rodondi). Carole E. Aubert was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Ambizione Grant PZ00P3_201672). Valerie Aponte Ribero was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 325130_204361 / 1). The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the European Commission and the Swiss government. This project was also partially funded by the Swiss National Scientific Foundation (SNSF 320030_188549). The funder of the study had no role in the study design; data collection, analysis and interpretation; or writing of the report.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript was disclosed.

1. Kim S, Lee H, Park J, Kang J, Rahmati M, Rhee SY, et al. Global and regional prevalence of polypharmacy and related factors, 1997-2022: an umbrella review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2024 Sep;124:105465.

2. Guthrie B, Makubate B, Hernandez-Santiago V, Dreischulte T. The rising tide of polypharmacy and drug-drug interactions: population database analysis 1995-2010. BMC Med. 2015 Apr;13(1):74.

3. Hughes LD, McMurdo ME, Guthrie B. Guidelines for people not for diseases: the challenges of applying UK clinical guidelines to people with multimorbidity. Age Ageing. 2013 Jan;42(1):62–9.

4. Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017 Oct;17(1):230.

5. Baré M, Lleal M, Ortonobes S, Gorgas MQ, Sevilla-Sánchez D, Carballo N, et al.; MoPIM study group. Factors associated to potentially inappropriate prescribing in older patients according to STOPP/START criteria: MoPIM multicentre cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2022 Jan;22(1):44.

6. Roux B, Sirois C, Simard M, Gagnon ME, Laroche ML. Potentially inappropriate medications in older adults: a population-based cohort study. Fam Pract. 2020 Mar;37(2):173–9.

7. Nothelle SK, Sharma R, Oakes A, Jackson M, Segal JB. Factors associated with potentially inappropriate medication use in community-dwelling older adults in the United States: a systematic review. Int J Pharm Pract. 2019 Oct;27(5):408–23.

8. O’Connor MN, Gallagher P, O’Mahony D. Inappropriate prescribing: criteria, detection and prevention. Drugs Aging. 2012 Jun;29(6):437–52.

9. By the 2023 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023 Jul;71(7):2052–81.

10. O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, O’Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015 Mar;44(2):213–8.

11. Galvin R, Moriarty F, Cousins G, Cahir C, Motterlini N, Bradley M, et al. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing and prescribing omissions in older Irish adults: findings from The Irish LongituDinal Study on Ageing study (TILDA). Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014 May;70(5):599–606.

12. Kuijpers MA, van Marum RJ, Egberts AC, Jansen PA; OLDY (OLd people Drugs & dYsregulations) Study Group. Relationship between polypharmacy and underprescribing. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008 Jan;65(1):130–3.

13. Mekonnen AB, Redley B, de Courten B, Manias E. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and its associations with health-related and system-related outcomes in hospitalised older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021 Nov;87(11):4150–72.

14. Jungo KT, Streit S, Lauffenburger JC. Utilization and Spending on Potentially Inappropriate Medications by US Older Adults with Multiple Chronic Conditions using Multiple Medications. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2021;93:104326.

15. Weeda ER, AlDoughaim M, Criddle S. Association Between Potentially Inappropriate Medications and Hospital Encounters Among Older Adults: A Meta-Analysis. Drugs Aging. 2020 Jul;37(7):529–37.

16. Malakouti SK, Javan-Noughabi J, Yousefzadeh N, Rezapour A, Mortazavi SS, Jahangiri R, et al. A Systematic Review of Potentially Inappropriate Medications Use and Related Costs Among the Elderly. Value Health Reg Issues. 2021 Sep;25:172–9.

17. Hill-Taylor B, Walsh KA, Stewart S, Hayden J, Byrne S, Sketris IS. Effectiveness of the STOPP/START (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ potentially inappropriate Prescriptions/Screening Tool to Alert doctors to the Right Treatment) criteria: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016 Apr;41(2):158–69.

18. Díaz Planelles I, Navarro-Tapia E, García-Algar Ó, Andreu-Fernández V. Prevalence of Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions According to the New STOPP/START Criteria in Nursing Homes: A Systematic Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2023 Feb;11(3):422.

19. Thomas RE, Thomas BC. A Systematic Review of Studies of the STOPP/START 2015 and American Geriatric Society Beers 2015 Criteria in Patients ≥ 65 Years. Curr Aging Sci. 2019;12(2):121–54.

20. Fralick M, Bartsch E, Ritchie CS, Sacks CA. Estimating the Use of Potentially Inappropriate Medications Among Older Adults in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020 Dec;68(12):2927–30.

21. Tian F, Chen Z, Zeng Y, Feng Q, Chen X. Prevalence of Use of Potentially Inappropriate Medications Among Older Adults Worldwide: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:(8):e2326910-e; https://doi.org/

22. Pan S, Li S, Jiang S, Shin JI, Liu GG, Wu H, et al. Trends in Number and Appropriateness of Prescription Medication Utilization Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults in the United States: 2011-2020. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2024 Jul;79(7):glae108.

23. Thorell K, Midlöv P, Fastbom J, Halling A. Use of potentially inappropriate medication and polypharmacy in older adults: a repeated cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2020 Feb;20(1):73.

24. Moriarty F, Bennett K, Fahey T, Kenny RA, Cahir C. Longitudinal prevalence of potentially inappropriate medicines and potential prescribing omissions in a cohort of community-dwelling older people. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015 Apr;71(4):473–82.

25. Damoiseaux-Volman BA, Medlock S, Raven K, Sent D, Romijn JA, van der Velde N, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing in older hospitalized Dutch patients according to the STOPP/START criteria v2: a longitudinal study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2021 May;77(5):777–85.

26. Jungo KT, Choudhry NK, Chaitoff A, Lauffenburger JC. Associations between sex, race/ethnicity, and age and the initiation of chronic high-risk medication in US older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2024 Dec;72(12):3705–18.

27. Dalleur O, Boland B, Losseau C, Henrard S, Wouters D, Speybroeck N, et al. Reduction of potentially inappropriate medications using the STOPP criteria in frail older inpatients: a randomised controlled study. Drugs Aging. 2014 Apr;31(4):291–8.

28. Blum MR, Sallevelt BT, Spinewine A, O’Mahony D, Moutzouri E, Feller M, et al. Optimizing Therapy to Prevent Avoidable Hospital Admissions in Multimorbid Older Adults (OPERAM): cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2021 Jul;374(1585):n1585.

29. Crowley EK, Sallevelt BT, Huibers CJ, Murphy KD, Spruit M, Shen Z, et al. Intervention protocol: OPtimising thERapy to prevent avoidable hospital Admission in the Multi-morbid elderly (OPERAM): a structured medication review with support of a computerised decision support system. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020 Mar;20(1):220.

30. Adam L, Moutzouri E, Baumgartner C, Loewe AL, Feller M, M’Rabet-Bensalah K, et al. Rationale and design of OPtimising thERapy to prevent Avoidable hospital admissions in Multimorbid older people (OPERAM): a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2019 Jun;9(6):e026769.

31. Panos A. R Package that evaluates patient data for START and STOPP criteria. https://github.com/agapiospanos/StartStopp (2021). Accessed 19.06.2025.

32. Anrys P, Boland B, Degryse JM, De Lepeleire J, Petrovic M, Marien S, et al. STOPP/START version 2-development of software applications: easier said than done? Age Ageing. 2016 Sep;45(5):589–92.

33. Anrys PM, Strauven GC, Foulon V, Degryse JM, Henrard S, Spinewine A. Potentially Inappropriate Prescribing in Belgian Nursing Homes: Prevalence and Associated Factors. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018 Oct;19(10):884–90.

34. Doherty AS, Moriarty F, Boland F, Clyne B, Fahey T, Kenny RA, et al. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in community-dwelling older adults: an application of STOPP/START version 3 to The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). Eur Geriatr Med. 2025 Aug;16(4):1389–402.

35. Tommelein E, Mehuys E, Petrovic M, Somers A, Colin P, Boussery K. Potentially inappropriate prescribing in community-dwelling older people across Europe: a systematic literature review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015 Dec;71(12):1415–27. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-015-1954-4

36. Jungo KT, Ansorg AK, Floriani C, Rozsnyai Z, Schwab N, Meier R, et al. Optimising prescribing in older adults with multimorbidity and polypharmacy in primary care (OPTICA): cluster randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2023 May;381:e074054.

37. Xu Z, Liang X, Zhu Y, Lu Y, Ye Y, Fang L, et al. Factors associated with potentially inappropriate prescriptions and barriers to medicines optimisation among older adults in primary care settings: a systematic review. Fam Med Community Health. 2021 Nov;9(4):e001325.

38. Herr M, Grondin H, Sanchez S, Armaingaud D, Blochet C, Vial A, et al. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medications: a cross-sectional analysis among 451 nursing homes in France. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017 May;73(5):601–8.

39. Rane PP, Guha S, Chatterjee S, Aparasu RR. Prevalence and predictors of non-evidence based proton pump inhibitor use among elderly nursing home residents in the US. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13(2):358–63.

40. Morin L, Laroche ML, Texier G, Johnell K. Prevalence of Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults Living in Nursing Homes: A Systematic Review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016 Sep;17(9):862.e1–9.

41. Redston MR, Hilmer SN, McLachlan AJ, Clough AJ, Gnjidic D. Prevalence of Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Inpatients with and without Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;61(4):1639–52. doi: https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-170842

42. Moon A, Jang S, Kim JH, Jang S. Risk of falls or fall-related injuries associated with potentially inappropriate medication use among older adults with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2024 Aug;24(1):699.

43. Tao L, Qu X, Gao H, Zhai J, Zhang Y, Song Y. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medications among elderly patients in the geriatric department at a single-center in China: A retrospective cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021 Oct;100(42):e27494. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000027494

44. Lopez-Rodriguez JA, Rogero-Blanco E, Aza-Pascual-Salcedo M, Lopez-Verde F, Pico-Soler V, Leiva-Fernandez F, et al.; MULTIPAP group. Potentially inappropriate prescriptions according to explicit and implicit criteria in patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy. MULTIPAP: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2020 Aug;15(8):e0237186.

45. Hansen CR, Byrne S, Cullinan S, O’Mahony D, Sahm LJ, Kearney PM. Longitudinal patterns of potentially inappropriate prescribing in early old-aged people. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018 Mar;74(3):307–13.

46. Moriarty F, Bennett K, Fahey T, Kenny RA, Cahir C. Longitudinal prevalence of potentially inappropriate medicines and potential prescribing omissions in a cohort of community-dwelling older people. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015 Apr;71(4):473–82.

47. Morgan SG, Weymann D, Pratt B, Smolina K, Gladstone EJ, Raymond C, et al. Sex differences in the risk of receiving potentially inappropriate prescriptions among older adults. Age Ageing. 2016 Jul;45(4):535–42.

48. Johnell K, Weitoft GR, Fastbom J. Sex differences in inappropriate drug use: a register-based study of over 600,000 older people. Ann Pharmacother. 2009 Jul;43(7):1233–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1M147

49. Nguyen K, Subramanya V, Kulshreshtha A. Risk Factors Associated With Polypharmacy and Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Ambulatory Care Among the Elderly in the United States: A Cross-Sectional Study. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2023 Sep;10(3):357–62.

50. Boyd A, Van de Velde S, Pivette M, Ten Have M, Florescu S, O’Neill S, et al.; EU-WMH investigators. Gender differences in psychotropic use across Europe: results from a large cross-sectional, population-based study. Eur Psychiatry. 2015 Sep;30(6):778–88.

51. Lang PO, Hasso Y, Dramé M, Vogt-Ferrier N, Prudent M, Gold G, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing including under-use amongst older patients with cognitive or psychiatric co-morbidities. Age Ageing. 2010 May;39(3):373–81.

52. Suzuki Y, Shiraishi N, Komiya H, Sakakibara M, Akishita M, Kuzuya M. Potentially inappropriate medications increase while prevalence of polypharmacy/hyperpolypharmacy decreases in Japan: A comparison of nationwide prescribing data. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2022;102:104733.

53. Oktora MP, Alfian SD, Bos HJ, Schuiling-Veninga CC, Taxis K, Hak E, et al. Trends in polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) in older and middle-aged people treated for diabetes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021 Jul;87(7):2807–17.

54. Bruin-Huisman L, Abu-Hanna A, van Weert HC, Beers E. Potentially inappropriate prescribing to older patients in primary care in the Netherlands: a retrospective longitudinal study. Age Ageing. 2017 Jul;46(4):614–9.

55. Drusch S, Le Tri T, Ankri J, Zureik M, Herr M. Decreasing trends in potentially inappropriate medications in older people: a nationwide repeated cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2021 Nov;21(1):621.

56. Cole JA, Gonçalves-Bradley DC, Alqahtani M, Barry HE, Cadogan C, Rankin A, et al. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023 Oct;10(10):CD008165. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008165.pub5

57. Sibille FX, de Saint-Hubert M, Henrard S, Aubert CE, Goto NA, Jennings E, et al. Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonists Use and Cessation Among Multimorbid Older Adults with Polypharmacy: Secondary Analysis from the OPERAM Trial. Drugs Aging. 2023 Jun;40(6):551–61.

58. Gagliano V, Salemme G, Ceschi A, Greco A, Grignoli N, Clivio L, et al. Antipsychotic, benzodiazepine and Z-drug prescriptions in a Swiss hospital network in the Choosing Wisely and COVID-19 eras: a longitudinal study. Swiss Med Wkly. 2024 Nov;154(11):3409.

59. Weymann D, Gladstone EJ, Smolina K, Morgan SG. Long-term sedative use among community-dwelling adults: a population-based analysis. CMAJ Open. 2017 Mar;5(1):E52–60.

The appendix is available in the pdf version of the article at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4892.