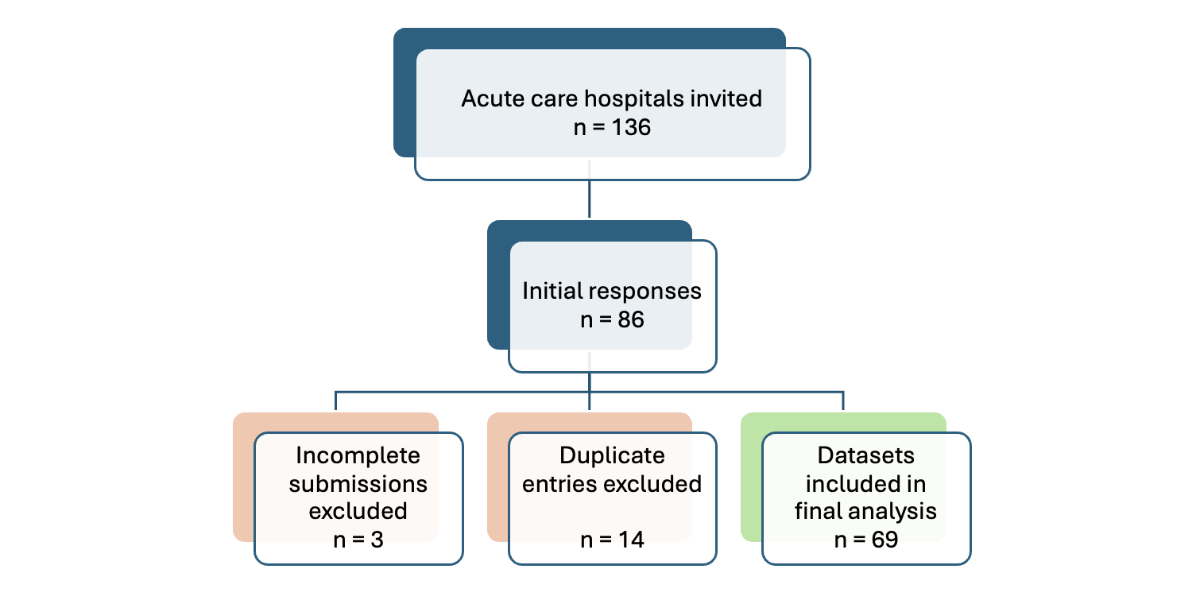

Figure 1 Flow diagram for the nationwide hospital survey depicting the number of institutions invited, exclusions, and final inclusion; based on STROBE [19].

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4860

Antimicrobial resistance is increasing worldwide, compromising patient safety and placing strain on healthcare systems, economies, and broader societal structures [1]. The scarcity of remaining effective antimicrobials makes routine medical procedures riskier and infections harder to diagnose and treat [2]. Inappropriate and excessive antimicrobial use contributes to the development of resistance; therefore, reducing unnecessary antibiotic use is a key strategy to address this global threat [3].

Antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) encompasses evidence-based strategies to optimise antimicrobial use and is recognised as a cornerstone of local, national, and international efforts to contain antimicrobial resistance [4]. In hospital settings, where the majority of broad-spectrum antibiotics are prescribed, antimicrobial stewardship interventions are vital for curbing overuse and improving the quality of prescribing. Local prescribing guidelines help ensure accurate indications and diagnostic workup, as well as the correct choice, dose, administration route, and duration of therapy. Additional antimicrobial stewardship activities include systematic monitoring of antimicrobial use, education and training, audits, and feedback to prescribers [5]. Hospitals should implement these activities as formal stewardship programmes (ASPs) underpinned by strong hospital leadership and a multidisciplinary team (IPC, pharmacy, microbiology, and quality improvement) [6]. In parallel, strengthening local infection prevention and control (IPC) is crucial, as lapses in IPC contribute to the spread of resistant organisms and escalate the risk of antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrobial stewardship programmes are cost-effective, achieving substantial reductions in healthcare costs, inappropriate antibiotic use, length of hospital stays, and adverse events [7, 8].

In Switzerland, approximately one-third of hospitalised patients receive antibiotics at any given time [9]. A recent point prevalence study at Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV) found that in 60% of patients receiving prophylaxis, antibiotics were continued beyond the indicated duration. In a similar proportion of patients treated for infections, at least one opportunity for treatment optimisation was identified, most commonly therapy discontinuation [10]. A study conducted at University Hospital Basel found that nearly 38% of empirical antibiotic prescriptions were inappropriate. Notably, consultation with an infectious diseases specialist was associated with improved prescribing appropriateness [11].

These findings demonstrate the need to strengthen antimicrobial prescribing practices. An early national assessment by Osthoff et al. in 2017, comparable to the present study in survey methodology and sample size yet differing in content, found that antimicrobial stewardship activities in Swiss hospitals were still at an initial stage: only 29% reported having a formal antimicrobial stewardship programme, and key activities such as antimicrobial use monitoring, prescribing guidelines, feedback mechanisms, education, and training were largely absent [12].

The Swiss Strategy on Antibiotic Resistance (StAR) for the human health sector is closely aligned with the National Strategy for the Monitoring, Prevention and Control of Healthcare-Associated Infections (NOSO Strategy) [13, 14]. StAR promotes rational antimicrobial use across the human, veterinary, agriculture, and environment sectors and is jointly implemented by the Federal Offices of Public Health (FOPH), Agriculture (FOAG), and Environment (FOEN), as well as the Food Safety and Veterinary Office (FSVO).

As part of StAR, the FOPH, together with the Swiss Society for Infectious Diseases (SSI) and the Swiss Society for Microbiology (SSM), supported Swissnoso to develop guidance documents and establish a national expert network on antimicrobial stewardship through the StAR-1 and StAR-2 projects [15]. The ongoing StAR-3 project (2023–2026) is conducted by Swissnoso in collaboration with six major professional societies and stakeholder organisations, including the SSI, the Swiss Society for Hospital Hygiene (SSHH), the Swiss Association of Public Health Pharmacists and Hospital Pharmacists (GSASA), the SSM, the Swiss Centre for Antibiotic Resistance (ANRESIS), and the umbrella organisation of Swiss physicians (FMH). The project is also supported by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Research Group (PIGS) (an associated partner) and the three observers: the Conference of Cantonal Health Directors (GDK-CDS), H+ (the association of Swiss hospitals), and the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH), which also provides financial support. The project aims to promote the structured implementation of antimicrobial stewardship programmes in acute care hospitals and establish national monitoring of antimicrobial stewardship activities [16].

This article presents the results of the nationwide antimicrobial stewardship monitoring survey and discusses critical gaps and challenges to guide the development of antimicrobial stewardship in Switzerland.

This study was a national cross-sectional survey targeting all acute care hospitals in Switzerland, with the aim of assessing the current state of implementing antimicrobial stewardship activities at the national level. The instrument was adapted from a validated tool developed by Kallen et al. (2018) for Dutch acute care hospitals [17]. The adaptation process involved contextual adjustments to align the survey content and terminology with the Swiss healthcare system, followed by pilot testing in nine hospitals of different sizes. The final version was reviewed and approved by the StAR-3 steering group. The final questionnaire (referred to as the “helvetised” version) included 54 primarily closed-ended questions covering key aspects of antimicrobial stewardship implementation (Appendix 1). The primary outcome was the presence of a formal antimicrobial stewardship programme; additional information was collected on other organisational characteristics and on whether at least one antimicrobial stewardship activity was implemented. Secondary outcomes included specific stewardship activities, such as monitoring of antimicrobial use, availability of treatment guidelines, education and training activities, formulary restriction, prescription audits and feedback, and internal reporting mechanisms.

In October 2024, 136 acute care hospitals identified from the official register of the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) were invited to participate in the survey [18]. An invitation letter was sent to each hospital director requesting that they forward the materials to the individual responsible for antimicrobial stewardship at their institution. The mailing package included a cover letter in the appropriate language, a letter addressed to the antimicrobial stewardship lead, and an official endorsement letter from the FOPH. A reminder was sent in mid-December 2024, and the survey closed on 10 January 2025.

Hospitals completed the questionnaire on a secure web-based platform (SurveyMonkey®, San Mateo, CA, USA). Only one response set per hospital was accepted. Survey responses were exported and cleaned to remove incomplete or duplicate entries. Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were used to summarise the data. A total of 86 responses were recorded. After excluding 14 duplicate entries (when more than one survey was saved for the same institution because of technical issues, only one entry was retained per hospital) and 3 incomplete responses, a total of 69 datasets were included in the final analysis (shown in the flow diagram in figure 1).

Data were summarised and analysed according to pre-defined criteria, with statistical tests applied to detect differences in the presence of stewardship activities based on whether a formal antimicrobial stewardship programme was in place.

Formal statistical analysis of more granular differences regarding stewardship activities and antimicrobial stewardship programme status (e.g. by language region and hospital type) was not conducted, as the sample size and validity were limited. Depending on the sample size and expected cell counts, two-sided Fisher’s exact or chi-square tests were used to evaluate associations between categorical variables. Data were summarised using descriptive statistics and data management in Microsoft Excel, and statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 18.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

The data quality was high. No responses were missing for 40 closed questions (82%), and only 7 questions (14%) had one or two missing values. Two questions had higher missing rates because of respondent uncertainty, but these were not included in the report.

Figure 1 Flow diagram for the nationwide hospital survey depicting the number of institutions invited, exclusions, and final inclusion; based on STROBE [19].

Of the 136 acute care hospitals invited to participate, 69 completed the survey, yielding a response rate of 51%. Tertiary care hospitals (university and regional referral centres) showed the highest participation at 68% (32/47), compared with 44% (28/63) for regional care hospitals and 35% (9/26) for specialised surgical clinics. This resulted in an over-representation of larger hospitals. However, participating institutions accounted for 916,560 of the 1,363,538 acute care discharges in Switzerland in 2023, representing 67% of all national discharges (73% of tertiary care, 52% of regional care, and 34% of specialised surgery clinic discharges), as shown in appendix 2 (table A).

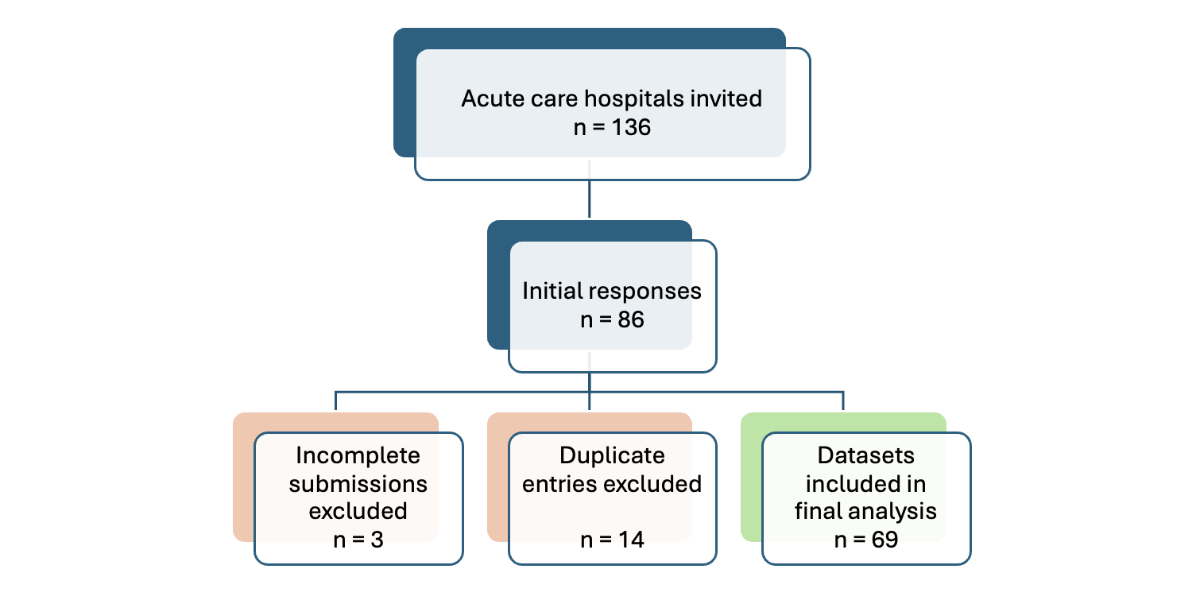

Most participating hospitals reported providing key consult services relevant to antimicrobial stewardship: 93% (64/69) provided infectious diseases specialist consult services, 84% (58/69) provided clinical pharmacy support, and 78% (54/69) provided microbiology advice (on-site, within the hospital group, or through contract with a third-party hospital or lab). The key results are summarised in figure 2 and appendix 2 (table B). Despite this infrastructure, only 41% (28/69) reported having a formal antimicrobial stewardship programme in place (primary outcome). Even fewer (22%, 15/69; not shown) reported explicit hospital management endorsement, either through an appointed board member for antimicrobial stewardship or a written hospital management statement. However, 86% of hospitals (59/69) reported engaging in at least one antimicrobial stewardship activity; these are referred to as “active hospitals”.

Figure 2 Proportion of hospitals (n = 69) reporting selected antimicrobial stewardship structures: providing infectious diseases, clinical pharmacy, microbiology consult services; hospitals with ≥1 stewardship activity and formal antimicrobial stewardship programmes. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Abbreviations: ASP = antimicrobial stewardship programme.

Among the 59 active hospitals (those reporting at least one antimicrobial stewardship activity, i.e. 86% of overall respondents), antimicrobial stewardship responsibilities were mostly embedded within existing infection prevention and control (IPC) or infectious diseases services (28/59, 47%). A formal antimicrobial stewardship team was in place in 14% (8/59), while other hospitals integrated stewardship within pharmacy, quality, or patient safety units. Nine hospitals (15) described their organisational structure for antimicrobial stewardship as unclear. Operational leadership was most assigned to infectious diseases specialists (43/59, 73%), with less frequent leadership roles for pharmacists, microbiologists, or quality and patient safety officers. Only 18% (10/59) had formally assigned FTEs for antimicrobial stewardship; most (43/59, 73%) reported no designated FTEs. Among the 35 hospitals that provided estimates, the average staffing was 0.5 FTE. Fewer than half of active hospitals (27/59, 46%) reported access to dedicated IT support for antimicrobial stewardship; when available, this was mainly used for surveillance activities, such as participation in the national point prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use in Swiss acute care hospitals (CH-PPS HAI).

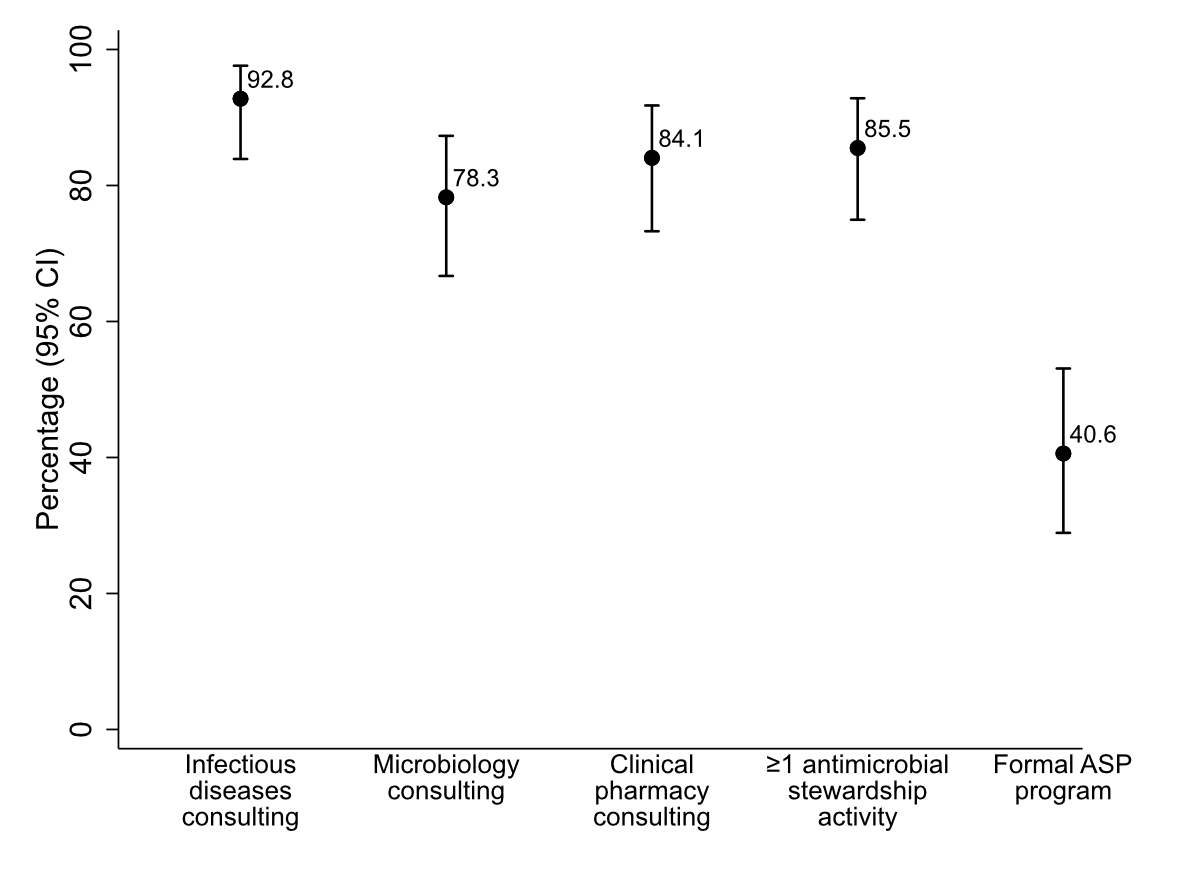

The following section provides an overview of secondary outcomes, namely specific antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) activities implemented in Swiss acute care hospitals. Key findings are summarised in figure 3 and appendix 2 (table C).

Surveillance activities: Monitoring of antimicrobial use and Clostridioides difficile infections were the most frequently reported surveillance activities. The majority (85%, 50/59) reported monitoring antibiotic consumption, typically through the ANRESIS network and covering all inpatient sectors. Most used these data for prescriber feedback, most commonly on an annual basis. Feedback methods included educational sessions, emails, grand rounds, and antimicrobial stewardship team visits or ward rounds. Approximately two-thirds of hospitals monitored Clostridioides difficile infections, tracked antimicrobial resistance trends, and produced annual cumulative susceptibility reports.

Guidelines: Available evidence-based treatment guidelines covering at least common infections and perioperative prophylaxis protocols were reported by 90% of hospitals (53/59). Perioperative prophylaxis protocols were most common (94%), followed by guidelines for common infections such as pneumonia and urinary tract infections (83%). Among hospitals with guidelines, 74% (39/53) had a formal review process. Access was primarily through the hospital intranet; some also used handbooks or apps.

Education and awareness: Antibiotic prescription training for existing staff was provided in more than half of the hospitals (35/59, 59%) and for new staff in one third (19/59, 32%). Training was mainly targeted at prescribers, and less at pharmacists and nurses. A total of 37% (22/59) of the hospitals had conducted antimicrobial stewardship awareness campaigns within the past 24 months.

Prescription practices: Infectious disease specialists participated in intensive care unit (ICU) ward rounds in 53% of active hospitals (31/59). Restrictions on certain antimicrobials were implemented in 34% (20/59), commonly through pharmacy order forms and pre- or post-authorisation. More active control measures (e.g. stop orders, delivery restrictions, post-prescription reviews) were rare. Most hospitals (36/59, 61%) had no restriction policy. Mandatory documentation of treatment indication was uncommon. Although most hospitals used electronic prescribing (47/69, 68%) or a hybrid model (16/69, 23%), some relied partly or entirely on paper-based systems.

CH-PPS HAI, audits, and feedback: All active hospitals had participated in the CH-PPS HAI within the past three years, but only 55% (28/51) reported providing survey results to prescribers. Regular audits of adherence to treatment guidelines or perioperative antibiotic use, referred to as prescription audits, were reported by only 20% (12/59). Most had no prescription audit processes in place.

Figure 3 Proportion of hospitals reporting selected antimicrobial stewardship activities among those with at least one implemented stewardship activity (n = 59): monitoring antimicrobial use, antimicrobial treatment guideline implementation, staff education (new vs existing staff), infectious diseases physician or pharmacist involvement in ICU rounds, antimicrobial prescribing restrictions, and prescription audits. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Abbreviation: AM = antimicrobial.

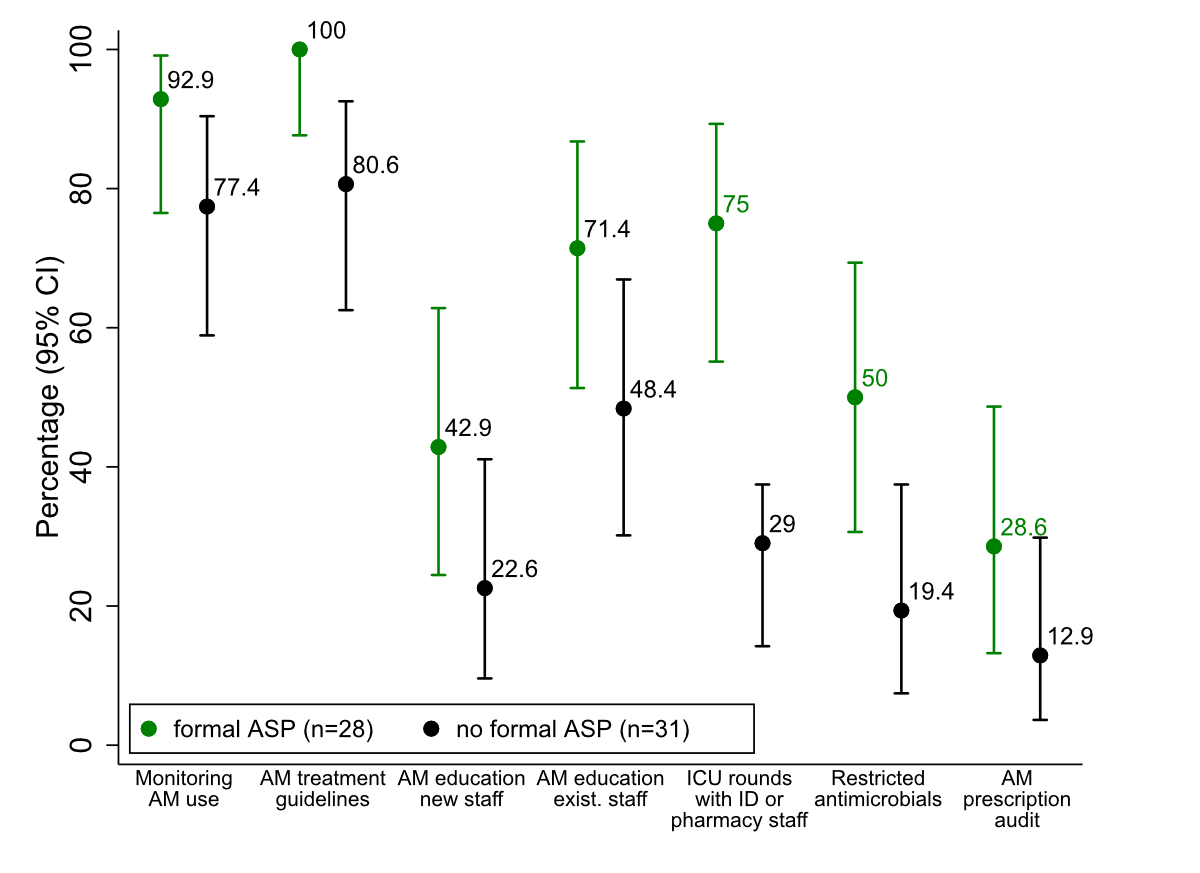

Hospitals with a formal antimicrobial stewardship programme consistently reported more antimicrobial stewardship activities in place (see figure 4 and appendix 2, table D). Although sample sizes were small, the presence of treatment guidelines, ICU rounds with ID or pharmacy staff, and antimicrobial restrictions was significantly higher among hospitals with an antimicrobial stewardship programme compared with those without (P = 0.025, <0.001, and 0.026, respectively; Fisher’s Exact test). For other antimicrobial stewardship activities, the observed differences were not statistically significant.

An ad hoc attempt at further subgroup analysis (beyond stewardship activities and antimicrobial stewardship programme status) confirmed the initial assumption of very small numbers and was not pursued further (no details presented here). Nonetheless, a trend indicated that compared with other hospitals, tertiary hospitals more frequently had a formal antimicrobial stewardship programme in place, used antimicrobial restrictions, and involved infectious diseases or pharmacy staff in ICU rounds, implementing more stewardship activities on average. Furthermore, hospitals in German-speaking regions more frequently had a formal antimicrobial stewardship programme in place.

Figure 4 Proportion of hospitals reporting selected antimicrobial stewardship activities among those with at least one implemented stewardship activity (n = 59), stratified by the presence or absence of a formal antimicrobial stewardship programme: monitoring antimicrobial use, antimicrobial treatment guideline implementation, staff education (new vs existing staff), infectious disease physician or pharmacist involvement in ICU rounds, antimicrobial prescribing restrictions, and prescription audits. Differences were significant for availability of treatment guidelines,ICU rounds with ID or pharmacy staff, and antimicrobial restrictions (P-values of 0.025, <0.001, and 0.026, respectively; Fisher’s Exact test). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Abbreviations: AM = antimicrobial; ASP = antimicrobial stewardship programme.

Following the 2017 early national assessment of antimicrobial stewardship activities by Swissnoso under the StAR-1 project, the present 2024 survey conducted as part of StAR-3 provides an updated and more detailed picture of antimicrobial stewardship programme implementation in Swiss hospitals. The survey, based on an adapted questionnaire derived from a validated Dutch tool [17], provides valuable insights into the current status and progress of antimicrobial stewardship programme implementation in Swiss hospitals. Despite differences in scope and objectives compared with the 2017 assessment, the findings indicate notable progress: the proportion of hospitals with a formal antimicrobial stewardship programme increased from 29% in 2017 to 41% in 2024 [12]. Improvements were also observed in resource allocation, antibiotic use monitoring, C. difficile infection surveillance, and involvement of infectious disease specialist or pharmacists in ICU rounds.

However, important challenges remain. Although most hospitals reported at least one antimicrobial stewardship activity, 14% had no activities in place, and only half had implemented a formal antimicrobial stewardship programme. Subgroup analysis indicated that hospitals with a formal antimicrobial stewardship programme more often applied critical antimicrobial stewardship activities, including antimicrobial use monitoring, staff education, prescription audits, and restriction policies. These results point to a widespread yet fragmented and largely reactive implementation of antimicrobial stewardship, with many hospitals lacking a structured, programmatic approach. Despite this, the positive trend since 2017 is encouraging. The widespread availability of local infectious diseases expertise and antimicrobial guidelines signals a structural readiness for developing an operational and sustainable antimicrobial stewardship programme.

Looking forward, sustained and well-coordinated efforts are essential. Advancing from structural readiness to a fully operational and sustainable antimicrobial stewardship programme will require strong institutional commitment, clear leadership, and dedicated antimicrobial stewardship programme teams, with adequate resources for successful implementation.

The 67 non-participating hospitals may have fewer antimicrobial stewardship resources and activities and likely represent facilities in greater need of targeted support. Notably, smaller hospitals were underrepresented in the survey and appear to have less developed stewardship structures. Interprofessional collaboration, especially among physicians, pharmacists, microbiologists, and nurses, must be strengthened, as this enhances antimicrobial stewardship outcomes and cost-effectiveness [20–22]. Education and training are critical areas for improvement. Postgraduate education and practical, on-the-job training in antimicrobial stewardship, particularly for prescribers and pharmacists, should be actively promoted.

This monitoring study had several limitations. As with most survey-based studies, participation was voluntary and skewed towards larger hospitals. It is likely that more institutions active in antimicrobial stewardship (e.g. ANRESIS and CH-PPS participants) participated. Additionally, there is a risk of social desirability or recall bias. Despite these limitations, the data provide valuable insights into the status and progress of national antimicrobial stewardship implementation.

Overall, Switzerland has made tangible progress in implementing antimicrobial stewardship programmes, largely driven by hospital-level initiatives and supported by the national StAR strategy. This is where the StAR-3 Handbook on antimicrobial stewardship builds upon previous work, providing a programmatic framework tailored to hospitals of all sizes [23, 24]. In line with the StAR-3 consortium’s recommendation, the implementation of a formal antimicrobial stewardship programme in every hospital should now be a priority. To emphasise the urgency of addressing antimicrobial resistance, the FOPH has proposed making formal antimicrobial stewardship programmes a requirement for hospitals in the consultation draft of the revised Epidemics Act. In addition, policy measures have reinforced implementation efforts, including the integration of antimicrobial stewardship into quality contracts under Article 58 KVG. Ongoing national efforts to align and create synergies between IPC and StAR are critical for the success and sustainability of hospital antimicrobial stewardship programmes. The progress, challenges, and priorities described in the Swissnoso Reports on IPC [25] extend beyond infection prevention and carry important implications for antimicrobial stewardship.

This nationwide antimicrobial stewardship survey conducted under StAR-3 establishes an important foundation for continuous monitoring of stewardship activities in Swiss hospitals. The collected data, combined with national-level progress indicators currently under development, will provide a reference point for coordinated national action, policy development, and targeted interventions to advance antimicrobial stewardship implementation.

This nationwide survey demonstrates encouraging progress in antimicrobial stewardship implementation since 2017: most responding hospitals reported engaging in stewardship activities, and nearly half have established a formal antimicrobial stewardship programme. However, significant gaps remain. Effective and sustainable stewardship will require all hospitals to establish antimicrobial stewardship programmes while simultaneously improving surveillance, guideline use, education, training, and prescribing audits with feedback. To expand these efforts, coordinated initiatives by federal and cantonal authorities and national stakeholders are essential to advance the standardised implementation of antimicrobial stewardship programmes across Switzerland.

No study data will be shared, as disclosure of even anonymised survey data could allow re-identification of individual hospitals. Summary data and clarifications are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

We sincerely thank all participating hospitals for taking the time and effort to complete the survey. We are also grateful to the institutions involved in the piloting phase for their valuable input, and in particular to Gaud Catho for her detailed feedback on the questionnaire design.

We acknowledge the Swissnoso StAR-3 steering group for their guidance and contributions, and we thank Simon Gottwalt at the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) for his consistent, constructive input and financial support for this project.

StAR-3 partner organizations and their respective steering group representatives are: Swissnoso: PD Dr. Laurence Senn, Steering group president, and Prof. Dr. Sarah Tschudin-Sutter; Swiss Society for Infectious Diseases (SSI): Prof. Dr. Stefan Kuster and Prof. Dr. Luigia Elzi; Swiss Society for Hospital Hygiene (SSHH): Prof. Dr. Walter Zingg and Dr. Catherine Plüss-Suard; Swiss Society for Microbiology (SSM): Prof. Dr. Dr. Adrian Egli, FAMH and Dr. Linda Müller, PhD, FAMH; Swiss Association for Public Administration and Hospital Pharmacists (GSASA): Dr. Vera Jordan and Dr. Delia Halbeisen; ANRESIS: Prof. Dr. Andreas Kronenberg and Dr. Catherine Plüss-Suard; FMH: Dr. med. Carlos Quinto and Dr. med. Philippe Eggimann. Associated partner: Pediatric Infectious Disease Group of Switzerland (PIGS): Prof. Dr. Julia Bielicki. Observers: GDK-CDS: Dr. Matthias Fügi. FOPH (also providing financial support): Simon Gottwalt

Author contributions: ME, VV, PJ, and LS were involved in the conception and design of the questionnaire and the report, which was approved by the StAR-3 steering group. ME and VV equally contributed as first authors and drafted the original version of the manuscript. VV and AS created data summaries, and AS conducted statistical analysis and created the graphs. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript, with PJ and LS equally contributing as last authors.

Financial support was provided by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health.

1. OECD. Embracing a One Health Framework to Fight Antimicrobial Resistance. OECD Health Policy Studies. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2023.

2. World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance fact sheet [Internet]. 21 November 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance

3. O’Neill J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. 2016. Available from: https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160518_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf

4. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: guidelines by the IDSA and SHEA. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):e51–77.

5. World Health Organization. Guidelines on core components of infection prevention and control programmes at the national and acute health care facility level. 2016. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549929

6. Swissnoso. Handbuch zur Implementierung von Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmen (ASP) in Schweizer Spitälern. 1. Auflage. Bern: Swissnoso; 2024. Available from: https://www.swissnoso.ch/fileadmin/swissnoso/Dokumente/5_Forschung_und_Entwicklung/3_Umsetzung_StAR/StAR_3/Handbook_Deutsch/ASP_Handbook_DE.pdf

7. Huser J, Dörr T, Berger A, Kohler P, Kuster SP. Economic evaluations of antibiotic stewardship programmes 2015-2024: a systematic review. Swiss Med Wkly. 2025 May;155(5):4217. Available from: https://smw.ch/index.php/smw/article/view/4217 doi: https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4217

8. UKHSA. Antimicrobial stewardship – Start smart, then focus (last updated 2023). Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/antimicrobial-stewardship-start-smart-then-focus/start-smart-then-focus-antimicrobial-stewardship-toolkit-for-inpatient-care-settings

9. Swissnoso. Point prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use in Swiss acute-care hospitals 2024. Bern; 2025. https://www.swissnoso.ch/fileadmin/swissnoso/Dokumente/5_Forschung_und_Entwicklung/2_Punktpraevalenzstudie/PPS_Report_2024.pdf

10. Moulin E, Boillat-Blanco N, Zanetti G, et al. Point prevalence study of antibiotic appropriateness and opportunity for early discharge at a Swiss University Hospital. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2022;11:66.

11. Gürtler N, Erba A, Giehl C, Tschudin-Sutter S, Bassetti S, Osthoff M. Appropriateness of antimicrobial prescribing in a Swiss tertiary care hospital: a repeated point prevalence survey. Swiss Med Wkly. 2019 ;149(4142):w20135. doi: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2019.20135

12. Osthoff M, Bielicki J, Widmer AF, For Swissnoso. Evaluation of existing and desired antimicrobial stewardship activities and strategies in Swiss hospitals. Swiss Med Wkly. 2017 Oct;147(4142):w14512.

13. Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH). Swiss Antibiotic Resistance Strategy (StAR). Bern: FOPH; 2024. Available from: https://www.star.admin.ch/en

14. Federal Office of Public Health. National Strategy on Healthcare-Associated Infections (NOSO Strategy). 2022. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/en/noso-strategy-reduce-hospital-and-nursing-home-infections

15. Swissnoso. StAR-Umsetzung: Umsetzung der nationalen Strategie gegen Antibiotikaresistenzen (StAR). Bern: Swissnoso; 2024. Available from: https://www.swissnoso.ch/forschung-entwicklung/umsetzung-star/umsetzung-der-nationalen-strategie-gegen-antibiotikaresistenzen-star

16. Swissnoso. StAR-3 Project. 2024. Available from: https://www.swissnoso.ch/en/forschung-entwicklung/umsetzung-star/umsetzung-der-nationalen-strategie-gegen-antibiotikaresistenzen-star

17. Kallen MC, Prins JM, Opmeer BC. Design and validation of a questionnaire to measure the implementation of antimicrobial stewardship programs in hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(11):3293–300.

18. Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH). Key figures of Swiss hospitals 2022. Statistics on health insurance. Bern: FOPH; March 2024. Available online: German: https://www.bag.admin.ch/kzss

19. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007 Oct;370(9596):1453–7.

20. Ha D. FORTE MB. Actively Involving Nurses in Antibiotic Stewardship. Contagion 2018;24(3):98–102. https://www.contagionlive.com/view/actively-involving-nurses-in-antibiotic-stewardship

21. Gilchrist M, Wade P, Ashiru-Oredope D, Howard P, Sneddon J, Whitney L, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship from policy to practice: experiences from UK antimicrobial pharmacists. Infect Dis Ther. 2015 Sep;4(S1 Suppl 1):51–64.

22. Naylor NR, et al. Cost-effectiveness of antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23(11):806–11.

23. Swissnoso. StAR‑3: Content development of 2nd ed. handbook, Implementing Antimicrobial Stewardship in Swiss Hospitals. Available from: https://www.swissnoso.ch/forschung-entwicklung/umsetzung-star/ausschreibung-ergebnisse

24. Swissnoso. StAR‑3: Implementing Antimicrobial Stewardship in Swiss Hospitals – Call for project proposals (including implementation aids, WP8). Bern: Swissnoso; 2024. Available on request.

25. Swissnoso. Epidemiology and prevention of healthcare-associated infections in Swiss acute care hospitals in 2024. Available from: https://www.swissnoso.ch/guidelines-publikationen/jaehrliche-epidemiologische-berichte-1

Appendix 1 (final questionnaire) and appendix 2 (supplementary tables A-D) are available in the PDF version of the article at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4860.