Quality assessment of Andrographis paniculata products reveals significant labelling inaccuracies and contaminations

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4728

Angélique Bourquiab,

Hugo Morincd,

Robin Hubercd,

Chantal Csajkabcd,

Clara Podmorea,

Jean-Luc Wolfendercd,

Emerson Ferreira Queirozcd*,

Pierre-Yves Rodondia*

a Institute

of Family Medicine, Faculty of Science and Medicine, University of Fribourg,

Fribourg, Switzerland

b Centre for Research and Innovation in Clinical Pharmaceutical Sciences, University

Hospital and University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

c School of

Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Geneva, CMU, Geneva, Switzerland

d Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences

of Western Switzerland, University of Geneva, CMU, Geneva, Switzerland

* Equal

contribution as last authors

Summary

BACKGROUND: Andrographis paniculata products

have gained in popularity for the management of respiratory infections since the

COVID-19 pandemic. None of these products holds marketing authorisation and all

are sold as herbal food supplements. Current herbal food supplement regulations

generally do not impose quality assessments prior to commercialisation, such that

the quality of herbal food supplements available to consumers is largely unknown.

STUDY

AIM: To assess the quality, purity and labelling accuracy of A. paniculata-containing

products, focusing on andrographolide content (the pharmaceutically active component)

and the presence of contaminants and residues.

METHODS: Forty A. paniculata-containing

products were purchased from 13 countries: 13 from pharmacies and 27 from online

retailers readily accessible to consumers in Switzerland. Samples were analysed

using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography–ultraviolet (UHPLC-UV) and ultra-high-performance

liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS) based on the European Pharmacopoeia

method. Contaminants and residues were assessed using inductively coupled plasma

mass spectrometry and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, respectively.

RESULTS: All samples except one contained A.

paniculata. The measured daily dose of andrographolide was compared to the labelled dose.

Andrographolide content ranged from 29% to 174% of the labelled dose, with only

2 products accurately labelled, while 20 were underdosed and 1 overdosed. Two products

contained quercetin, which interfered with UHPLC-UV analysis. Additionally, three

online-purchased products contained toxic contaminants, including a heavy metal

(mercury) or pesticides (strychnine, butralin).

CONCLUSION: This study reveals widespread mislabelling

and underdosing in A. paniculata-containing food supplements marketed internationally,

along with the presence of impurities that pose risks to consumers in products bought

online. Regulatory authorities must implement stringent quality controls to ensure

consumer safety and product transparency.

Abbreviations

- A. paniculata

-

Andrographis paniculata

- HPLC

-

high-performance liquid chromatography

- MS

-

mass spectrometry

- UHPLC

-

ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography

Introduction

One in four people in Switzerland take food supplements, including

herbal products [1]. Herbal

products are consumed for a variety of purposes, often driven by the perception

that they are ‘natural’, so less harmful than conventional pharmaceutical medicines.

Herbal products

are considered herbal medicinal products or herbal food supplements depending

on whether they are marketed with a health or with a nutritional claim, respectively,

as well as the dosage of the pharmacologically active substance [2]. This in turn

determines whether they are subject to drug or food regulations [3, 4]. In Europe,

several governments, including Switzerland, hold a list of botanicals that can only

be commercialised as a herbal medicinal product and not a herbal food supplement,

mainly because of safety concerns [5].

Despite their widespread use,

herbal food supplements are generally not subject to safety or quality assessment

before commercialisation, so their quality depends on the manufacturer [3]. Also,

the regulatory framework for herbal food supplements differs from country to country

and is generally less rigorous than that of herbal medicinal products [3]. Concerns

have been raised

about the safety of various herbal products, including unsanitary manufacturing

conditions, adulteration, plant misidentification, contamination with heavy metals

or pesticides, and inaccurate labelling [6, 7]. Despite this, few high-quality studies

have assessed

the quality and safety of herbal food supplements.

Andrographis paniculata is an Asian medicinal plant primarily used in

traditional medicine to treat respiratory infections [8, 9]. A. paniculata is currently available worldwide, but only as a herbal food supplement

[10]. Andrographolide, the

main component and the pharmaceutically active substance, is thought to have anti-inflammatory,

antiviral and immunity-stimulating

properties [11]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials

suggested

that A. paniculata extract (an andrographolide dose of 60 mg/day) may reduce

the severity and frequency of cough symptoms of upper respiratory tract infections

[12, 13], but robust clinical evidence is still lacking [9]. More recently, the

Thai government recommended A. paniculata as a remedy for mild cases of SARS-CoV-2

infections [14], leading to a surge in consumption, including in Western countries

where it was already used for the symptomatic treatment of the common cold [15],

sometimes outpacing regulatory oversight.

We investigated the quality

and purity of herbal products marketed as containing A. paniculata, obtained

from pharmacies or purchased online internationally – including from Switzerland

– focusing on contaminants (heavy metals) and residues (pesticides). We developed

an analytical

approach based on ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) combined with

two independent

detection methods – mass

spectrometry (MS) and ultraviolet (UV) – to analyse 40 commercially available A.

paniculata-containing products.

Materials and methods

The sample of herbal products containing Andrographis paniculata

Between 3 February and 18 August

2023, 40 products containing A. paniculata were purchased by the investigators

and analysed before their expiry date. Of these, 13 were purchased opportunistically

directly from pharmacies (Ph) in seven countries, including Switzerland, and 27

were ordered from online sources (On) accessible from Switzerland (table 1). To

be included in the study, the product had to mention A. paniculata on its

labelling and had to be intended for oral use. One pack of each product was purchased,

and the brand name, place of purchase, formulation, indications, labelled dose of

A. paniculata and andrographolide per serving, recommended dosages, Good

Manufacturing Practice certification from the manufacturer, and cost per pack were

recorded.

Table 1Characteristics of Andrographis

paniculata-containing products obtained from labelling and estimated daily dose

of Andrographis paniculata and andrographolide.

| Product code |

Country of purchase/dispatch |

Formulation |

Manufacturer claims

GMP compliance? |

Number of other ingredients |

Maximum daily dosage |

Daily dose of, mg/day * |

Daily dose of andrographolide,

mg/day * |

| Ph1 |

Switzerland |

Powder |

No |

0 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Ph2 |

Switzerland |

Capsule |

No |

0 |

6 |

720 |

NA |

| Ph3 |

Switzerland |

Tablet |

No |

4 |

2 |

200 |

20 |

| Ph4 |

France |

Capsule |

No |

11 |

4 |

200 |

10 |

| Ph5 |

USA |

Capsule |

Yes |

0 |

1 |

400 |

80 |

| Ph6 |

USA |

Capsule |

No |

0 |

2 |

1600 |

48 |

| Ph7 |

Germany |

Capsule |

No |

0 |

2 |

700 |

35 |

| Ph8 |

USA |

Capsule |

No |

0 |

2 |

800 |

60 |

| Ph9 |

Luxembourg |

Capsule |

No |

0 |

2 |

1000 |

100 |

| Ph10 |

USA |

Capsule |

Yes |

0 |

3 |

1200 |

120 |

| Ph11 |

Thailand |

Capsule |

No |

0 |

3 |

600 |

180 |

| Ph12 |

Canada |

Capsule |

Yes |

0 |

3 |

1200 |

120 |

| Ph13 |

Switzerland |

Liquid |

No |

0 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| On1 |

USA |

Capsule |

Yes |

0 |

6 |

3000 |

NA |

| On2 |

Belgium |

Capsule |

Yes |

0 |

6 |

NA |

NA |

| On3 |

Germany |

Capsule |

No |

0 |

2 |

800 |

NA |

| On4 |

Netherlands |

Capsule |

No |

0 |

2 |

800 |

NA |

| On5 |

UK |

Capsule |

No |

0 |

4 |

1880 |

NA |

| On6 |

Germany |

Capsule |

No |

0 |

10 |

2700 |

NA |

| On7 |

Germany |

Capsule |

No |

0 |

2 |

700 |

35 |

| On8 |

Poland |

Capsule |

No |

0 |

4 |

2000 |

NA |

| On9 |

Austria |

Capsule |

No |

0 |

2 |

700 |

35 |

| On10 |

Germany |

Capsule |

Yes |

0 |

1 |

400 |

40 |

| On11 |

USA |

Capsule |

Yes |

0 |

1 |

400 |

80 |

| On12 |

Lithuania |

Capsule |

Yes |

0 |

2 |

800 |

NA |

| On13 |

USA |

Capsule |

Yes |

0 |

1 |

400 |

40 |

| On14 |

France |

Capsule |

No |

1 |

6 |

2250 |

132 |

| On15 |

USA |

Capsule |

Yes |

0 |

2 |

900 |

150 |

| On16 |

France |

Capsule |

No |

0 |

2 |

1000 |

100 |

| On17 |

Belgium |

Capsule |

No |

0 |

2 |

1000 |

100 |

| On18 |

USA |

Capsule |

Yes |

0 |

4 |

1600 |

40 |

| On19 |

Austria |

Capsule |

No |

0 |

3 |

900 |

90 |

| On20 |

USA |

Capsule |

Yes |

0 |

3 |

1200 |

120 |

| On21 |

France |

Capsule |

No |

0 |

6 |

1800 |

180 |

| On22 |

USA |

Liquid |

No |

0 |

2.8 ml |

700 |

NA |

| On23 |

Austria |

Liquid |

No |

0 |

60 drops |

NA |

NA |

| On24 |

Poland |

Liquid |

No |

0 |

3 ml |

NA |

NA |

| On25 |

USA |

Liquid |

No |

0 |

360 drops |

NA |

NA |

| On26 |

USA |

Liquid |

No |

0 |

80 drops |

2857 |

NA |

| On27 |

USA |

Liquid |

No |

0 |

30 drops |

NA |

NA |

Pharmacy-purchased products

Pharmacies selling products

containing A. paniculata were identified opportunistically in seven countries

in Europe, Asia and North America. Countries, and consequently pharmacies, were

selected based on their proximity to the authors’ places of residence or locations

visited for professional or personal reasons. Researchers, acting as lay customers,

purchased A. paniculata over the counter for health reasons. Pharmacy staff

were unaware that these samples would be analysed for research purposes. Products

were purchased based on the pharmacist’s recommendation; the investigators did not

request a specific brand. In Switzerland, some formulations of A. paniculata

require a medical prescription, so these products were obtained directly by traditional

Chinese medicine physicians or therapists.

Online-purchased products

A. paniculata-containing products were also

ordered online for delivery to Switzerland. The online search was conducted using

three different search engines: Google, Ecosia and Bing. Search terms used were:

“Andrographis”, “Andrographis paniculata”, “Kalmegh” (the Thai name of A. paniculata),

“Buy Andrographis” and “Andrographis dietary supplements”. The first author clicked

on the hyperlinks from the first results page

of each search engine, which led directly to company websites selling A. paniculata-containing

products. All such products available on these websites were purchased, without

setting a maximum number of products per site. Product labels were not considered

during the selection process.

Chemicals and extracts

In this study, the reference

extract of A. paniculata was sourced from the United States Pharmacopeia

(USP; Rockville, MD, United States). Standard reference compounds, including andrographolide,

neoandrographolide and andrographiside, were purchased from Merck Sigma Aldrich

(Saint Louis, MO, United States). Quercetin was procured from Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland).

All references are reported in supplementary file 1 in the appendix, available for

download as separate file at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4728.

Laboratory analyses

For each A. paniculata

product, analyses were performed in triplicate.

Qualitative assessment of Andrographis paniculata

The qualitative evaluation

of A. paniculata was carried out in all 40 products (solids and liquids)

using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography

(UHPLC)–high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), which identifies compounds based

on their retention time (RT) and exact mass (m/z) (method detailed in supplementary

file 2 in the appendix (available for download as a separate file at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4728).

Sample preparation is described in the appendix, supplementary file 3. A reference

extract of A. paniculata was used to authenticate products by providing a

characteristic chemical signature (supplementary file 1 in the appendix). The

identity of the three most intense peaks was confirmed using exact mass and pure

standards of andrographolide, neoandrographolide and andrographiside.

Quantification of andrographolide

The quantity

of andrographolide was measured in 33 solid products, while liquid samples were

excluded due to insufficient content information. Analysis was performed using ultraviolet

and mass spectrometry detection, as detailed in the appendix (supplementary file

4 in the appendix).

HPLC-UV, the European Pharmacopoeia reference method, is widely used by manufacturers

for quantifying bioactive compounds in plant-based supplements due to its accessibility

[16]. Mass spectrometry

detection was employed to resolve co-eluting signals inherent to complex matrices,

ensuring greater selectivity.

Analysis of contaminants and residues

All 40 samples were analysed

for the presence of contaminants and residues. Measurements for heavy metals and

pesticides were performed at an accredited laboratory (ISO 17025). For the identification

and quantification of heavy metals, the samples were prepared using a method involving

high-pressure microwave-assisted acid digestion. Arsenic, lead, cadmium, mercury

and nickel were analysed using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (single-quadrupole

inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry [ICP-MS]). The assay

detection range for arsenic was 0.01–0.4 mg/kg dry matter; for lead, it was 0.003–0.4

mg/kg (dry matter); for cadmium, 0.002–0.4 mg/kg mg/kg (dry matter); for mercury,

0.005–0.4 mg/kg (dry matter); and for nickel, 0.1–0.4 mg/kg (dry matter). More-concentrated

samples were diluted in accordance with these detection ranges. Pesticides were

extracted using the QuEChERS method and subsequently analysed by liquid chromatography-mass

spectrometry/mass spectrometry [17].

Labelled and measured daily doses of andrographolide

For each solid A. paniculata product with

complete labelling, we calculated the labelled daily dose by multiplying the single

serving dose by the maximum daily servings (dosage) given on the labelling. We calculated

the labelled andrographolide daily dose based on its proportion in the extract.

For instance, product Ph10’s labelling indicated 400 mg of A. paniculata

per capsule with 10% andrographolide; with three capsules daily, the labelled doses

were 1200 mg and 120 mg, respectively. Similarly, we calculated the measured daily

dose of andrographolide for each sample using the average of the triplicate values

for both ultraviolet and mass spectrometry methods. For comparison of measured versus

labelled daily dose of andrographolide, and versus the daily therapeutic dose, we

considered results obtained using UHPLC-UV. However, mass spectrometry results were

prioritised when there were substantial differences between these two methods. HPLC-UV

is insufficient when it comes to analysing complex matrices such as those based

on several plant extracts.

Statistical analyses

We first compared andrographolide

quantification results from UHPLC-UV and UHPLC-MS methods by analysing the measured

daily dose of andrographolide using a two-tailed student’s t-test, Pearson correlation

and Bland–Altman analysis, considering p-values <0.05 as statistically significant.

We then compared the measured and labelled daily doses, considering any deviations

beyond the ±10% pharmacopoeial tolerance as inaccurately labelled [18]. Finally,

we assessed whether the measured daily dose in each product met the recommended

therapeutic dose (60 mg/day) for upper respiratory tract infections [8].

Ethics

Ethics approval was not required for this study

as it did not involve human participants, animal subjects or any other ethical concerns.

Results

Andrographis paniculata-containing

products

In this quality control study

of 40 herbal products containing A. paniculata, 13 were purchased from pharmacies

(Ph) and 27 online (On), as detailed in table 1; 24 came from European countries,

15 from the USA or Canada and 1 from Thailand. The cost of a 7-day supply ranged

from CHF 10.30 to 67.15 with an average of CHF 27.40.

The majority of products (33/40) were sold in a

solid form (mainly capsules), while the remaining 7 were in a liquid form. According

to labelling, 37 products had been prepared exclusively with an extract of A.

paniculata, 1 with a mixture of A. paniculata and Eleutherococcus

senticosus (On14) and 2 with a mixture of plants and vitamins (Ph3 and Ph4).

Seventeen products lacked labelling information about the quantity of andrographolide;

14 of these had been purchased online and 3 from pharmacies.

One product (identical brand,

packaging and labelling) was unintentionally purchased three times from three different

sources (On20, Ph12 and Ph10), and three other products were purchased twice (On7

and Ph7; On11 and Ph5; On17 and Ph9). Despite this, each sample was analysed as

an individual product. One product (On1) was received unlabelled, and another product

(solid) was excluded from the analysis as it had expired by the time the quality

control analyses were performed.

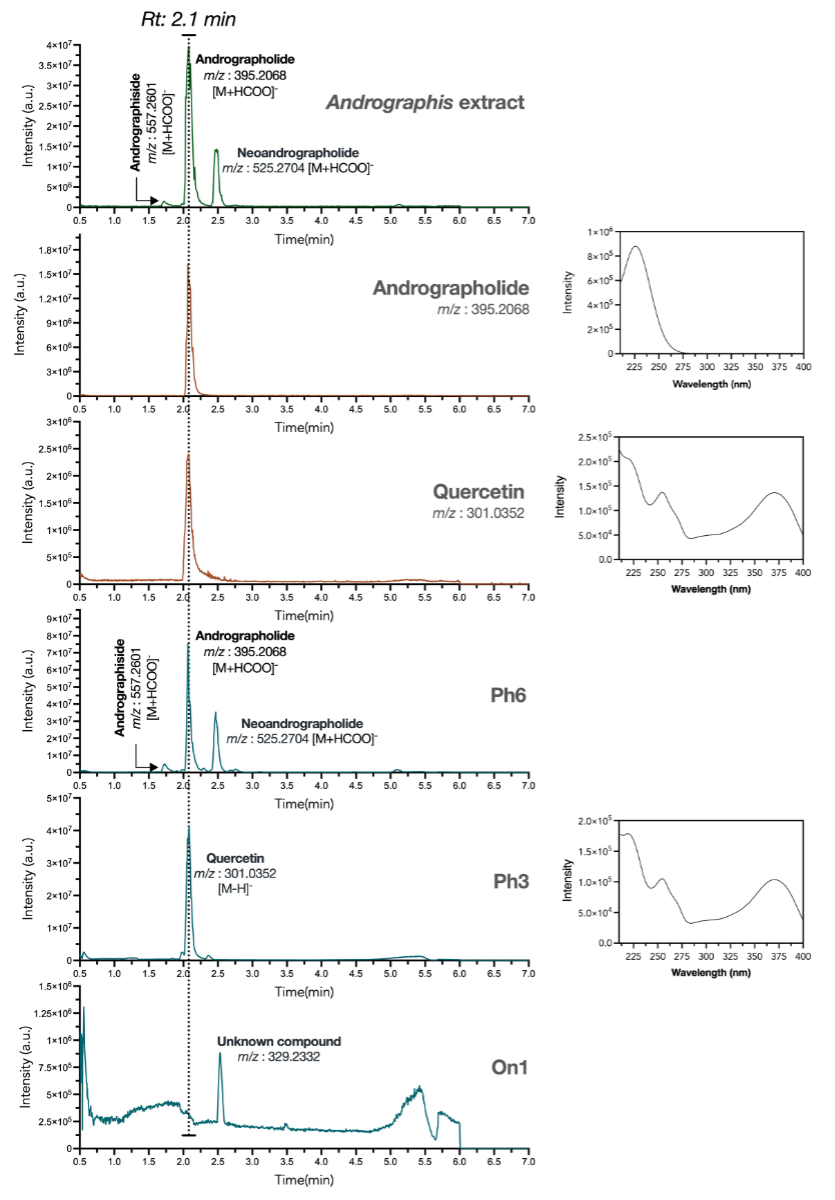

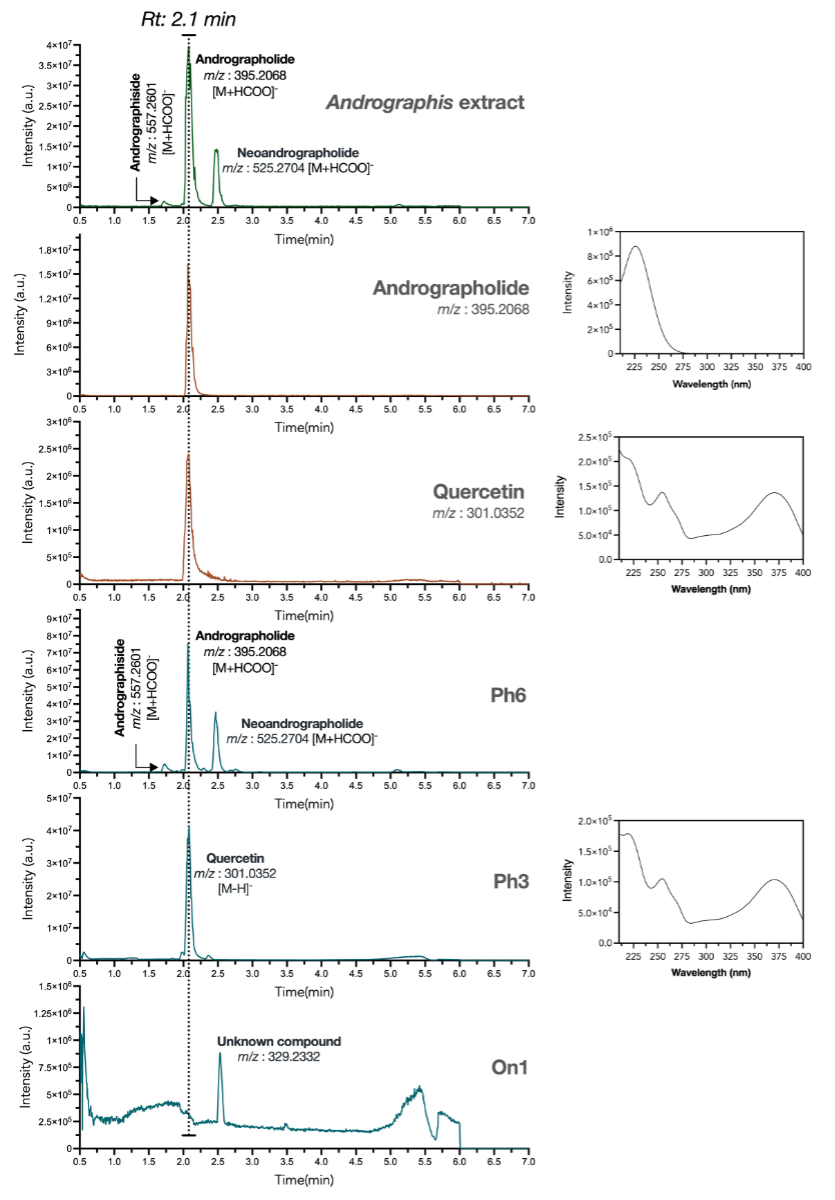

Quality assessment of Andrographis paniculata extract

Before analysing products containing

A. paniculata, we characterised a standardised reference methanolic extract

of this plant using UHPLC-HRMS. This analysis revealed the presence of signals attributable

to characteristic compounds already described from this plant, belonging to the

diterpene lactone chemical family [19] (figure S1 in the appendix,

available for download as a separate file at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4728). The

chromatogram showed andrographolide as the most intense peak (RT = 2.06 min, m/z

395.2070 [M+HCOO]−, Δ: 0.25 ppm), followed by neoandrographolide

(RT = 2.48 min, m/z 525.2706 [M+HCOO]−, Δ: 1.20 ppm) and andrographiside

(RT = 1.73 min, m/z 557.2601 [M+HCOO]−, Δ: 0.54 ppm). These identities

were confirmed by comparisons with pure reference standards. Additionally, ultraviolet

detection at 220 nm highlighted andrographolide as the compound with significant

absorption. Given its status as the literature-established bioactive constituent

and its chromatographic predominance, andrographolide was selected as the primary

chemical marker for quality control of A. paniculata-based products [15].

Among the 40 products analysed,

only one (On1) lacked the 3 characteristic peaks presented in the appendix (supplementary

file 5, figure S1).

Most products had a smaller andrographolide peak and a larger neoandrographolide

peak than the reference standard. In five products (Ph1, Ph2, On2, On12, On25),

neoandrographolide was the most intense analyte.

In addition

to the A. paniculata extract, Ph3 and Ph4 contained an abundant flavonoid,

quercetin. Using high-resolution mass spectrometry, an intense signal of

m/z: 301.0351 ([M−H]−) was recorded at the very same retention

time of andrographolide and unexpectedly corresponded to the exact mass of quercetin.

This was corroborated by the ultraviolet detection, which revealed a typical flavonoid

ultraviolet spectrum for this peak (figure 1). Finally, the injection of a pure

standard of quercetin confirmed co-elution of this compound and andrographolide

(detailed further in the appendix, supplementary file 5). To prevent bias in measurement,

a mass spectrometry detection method was developed in addition to the standard ultraviolet

method.

Figure 1UHPLC-PDA-HRMS chromatograms, comparing

standardised extract of Andrographis paniculata (green trace) vs marketed herbal products

(blue traces) and pure standards (orange traces). Andrographolide and quercetin

were found to elute at the same retention time (rt: 2.1 min) but were unequivocally

discriminated after their exact mass. Various herbal products differed in chemical

content: Ph6 resembled A. paniculata extract, Ph3 contained andrographolide

with a dominant quercetin signal and On1 lacked characteristic A. paniculata

signals. HRMS: high-resolution mass spectrometry; On: online; PDA: photo diode array;

Ph: pharmacy; UHPLC: ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography.

Quantification of andrographolide

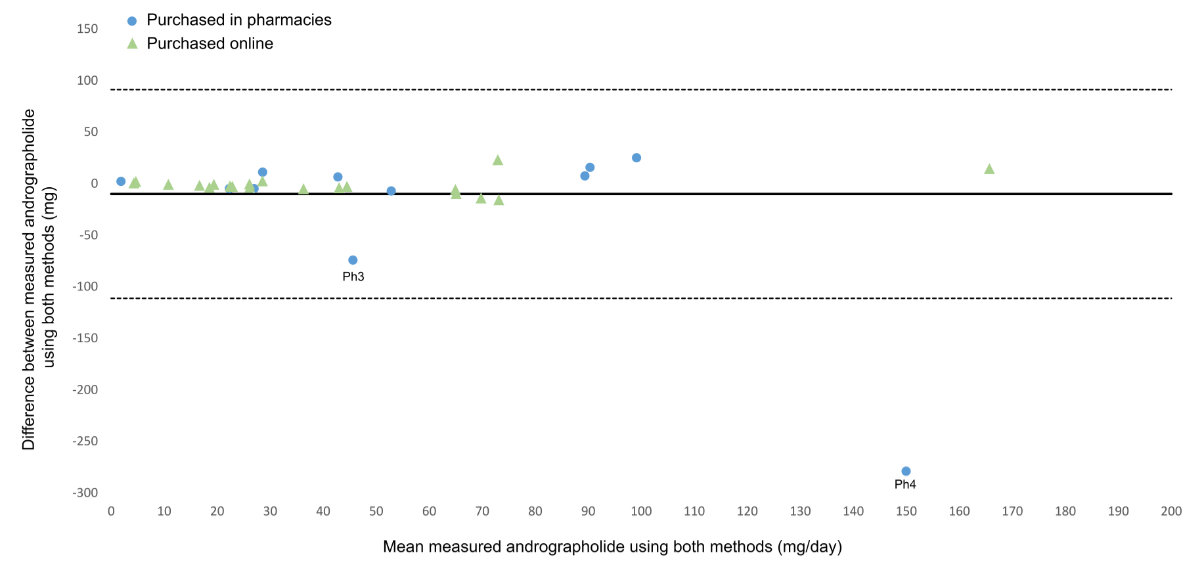

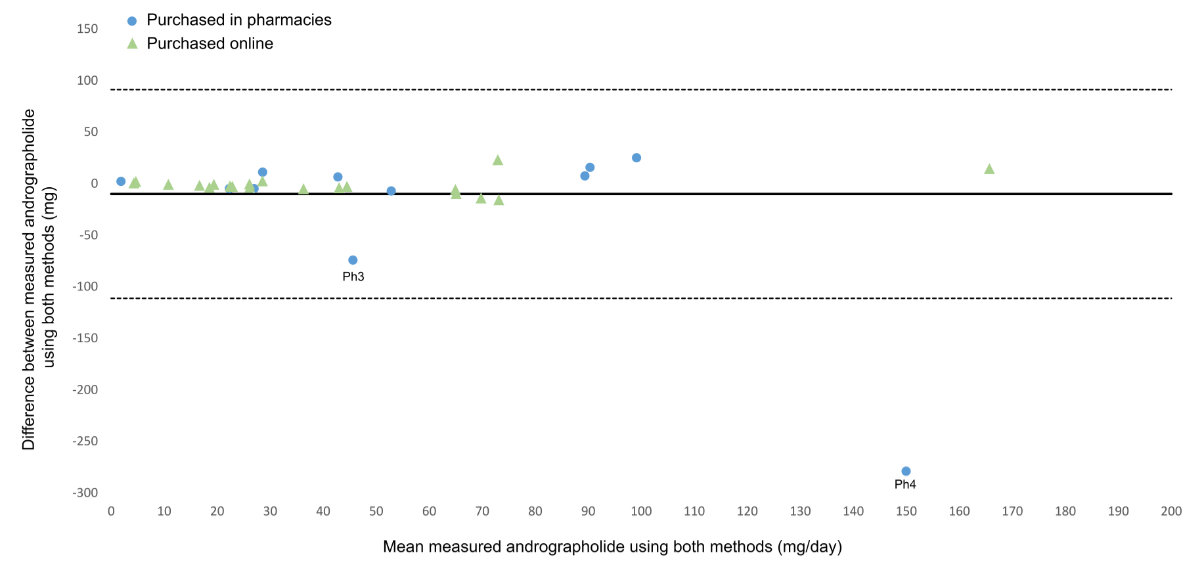

A Bland-Altman plot comparing

the measured daily dose of andrographolide using the UHPLC-UV and UHPLC-MS methods

is presented in figure 2. These results are comparable (t(62) = 0.83, p = 0.39)

using the two methods, except for two products, Ph3 and Ph4. The Pearson correlation

coefficient (r) between the results obtained using the UHPLC-UV and UHPLC-MS methods

was 0.44 overall (p ≤0.01) and 0.97 after removing these two outliers (p <0.01). The

ultraviolet and mass spectrometry methods produced similar results for most products,

independently confirming andrographolide levels (supplementary file 6 in the appendix,

figure S2). The UHPLC-UV method

was deemed reliable for the quantification of andrographolide, except for samples

Ph3 and Ph4, where quercetin interference skewed the results. In such cases, the

UHPLC-MS method proved more accurate.

Figure 2Bland-Altman plot of measured

andrographolide using UHPLC-MS versus UHPLC-UV expressed in daily dose for each

product purchased in a pharmacy or online. The solid line represents the mean difference

and the dashed lines represent the limits of agreement (mean difference ± 1.96 standard

deviations). MS: mass spectrometry; UHPLC: ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography;

UV: ultraviolet.

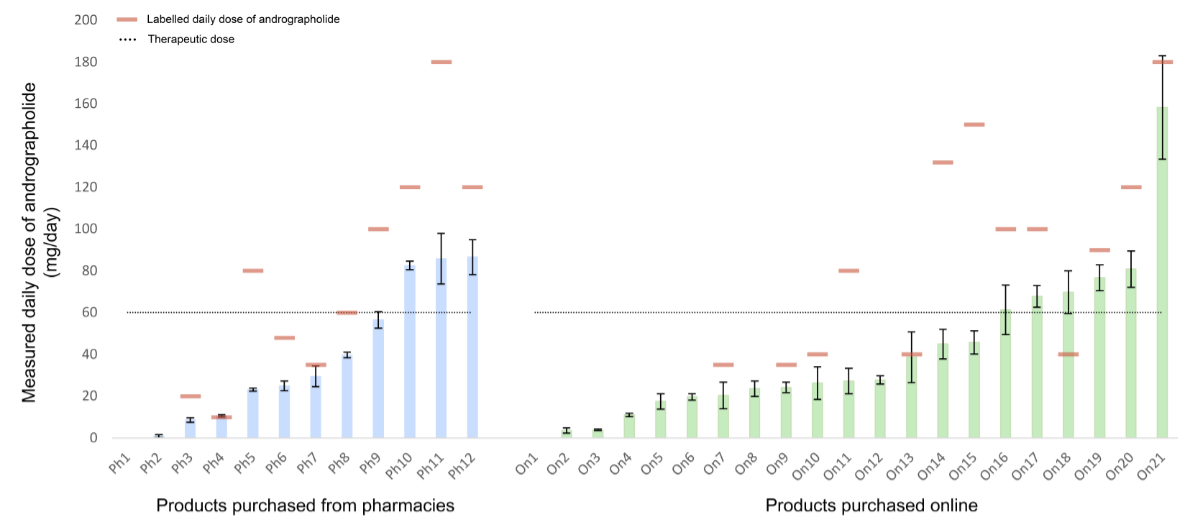

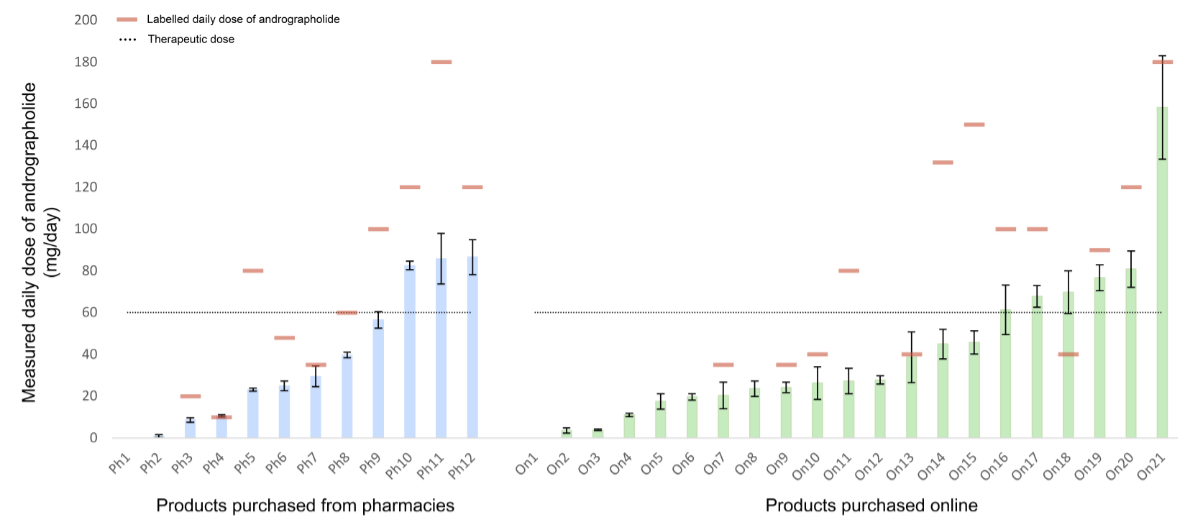

For 20 of 23 products with

complete labelling, the measured daily dose of andrographolide was lower than that

claimed on the labelling (figure 3). Products purchased online had a higher median

labelled daily dose of andrographolide (90 mg/day; range: 35–180 mg) than those

from pharmacies (70 mg/day; range: 10–180 mg). The measured dose of andrographolide

ranged from 29% to 174% of the labelled dose. Only two products (Ph4 and On13) were

accurately labelled, while 91% of products were inaccurately labelled. In one case

(On18), the measured dose exceeded the labelled amount; this discrepancy was not

explained by a high-dosage regimen.

Figure 3Daily dose of andrographolide

measured with UHPLC-UV in pharmacy products (light blue bars) and online products

(light green bars) compared with those on the label (red dash) and with the therapeutic

dose (dotted line). The data are from three product replicates ± standard deviation

(SD). UHPLC: ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography; UV: ultraviolet. * no

information about daily serving; ** no andrographolide detected.

Of the 33 products in solid

form, the labelled daily dose of andrographolide ranged from 10 mg to 180 mg per

day. As displayed in figure 3, the measured daily dose of nine products (27%) reached

at least 60 mg of andrographolide, which is the recommended therapeutic dose for

upper respiratory tract infections [8]. Even though Ph4 and On13were labelled

correctly, they did not reach the therapeutic dose. The daily dose of andrographolide

varied from batch to batch within products of the same brand, as shown with products

On7 and Ph7(20.3 mg vs 29.4 mg); On11 and Ph5 (27.2 mg vs 23.1 mg); On17

and Ph9(67.8 mg vs 56.5 mg). Twelve of the 33 solid products claimed

to have been manufactured in accordance with Good Manufacturing Practice in their

labelling. Of these, only On18 and On20 reached the therapeutic dose of andrographolide,

and On13 was accurately labelled. There was no pattern observed between labelling

accuracy and country of origin.

Analysis of contaminants and residues

Of the 40 A. paniculata-containing

products analysed, we identified levels of mercury that exceeded the maximum authorised

levels in one product and another two products contained contaminants (pesticides)

(table 2). These three products had all been purchased online. Product On5 contained

0.153 mg/kg of mercury (maximum tolerated according to the European legislation:

0.100 mg/kg), product On19 contained 0.023 mg/kg of butralin and On8 contained 0.058

mg/kg of strychnine. Butralin and strychnine are both pesticides banned throughout

Europe [20, 21].

Table 2Levels of heavy metals and pesticide

residues detected in products containing Andrographis paniculata.

| Product code |

Heavy metal (mg/kg) (ICP-MS) |

Pesticides (mg/kg) (LC-MS/MS) |

| Arsenic (As) (max: NA) |

Lead (Pb) (max: 3.0) |

Cadmium (Cd) (max: 1.0) |

Mercury (Hg) (max: 0.1) |

Nickel (Ni) (max: NA) |

Strychnine |

Butralin |

| Ph1 |

0.16 |

0.113 |

0.085 |

0.006 |

2.1 |

ND |

ND |

| Ph2 |

0.17 |

0.116 |

0.086 |

ND |

2.2 |

ND |

ND |

| Ph3 |

0.02 |

0.017 |

ND |

ND |

0.6 |

ND |

ND |

| Ph4 |

0.06 |

0.044 |

0.015 |

0.010 |

0.3 |

ND |

ND |

| Ph5 |

0.03 |

0.098 |

0.005 |

ND |

1.3 |

ND |

ND |

| Ph6 |

0.22 |

0.183 |

0.132 |

ND |

2.2 |

ND |

ND |

| Ph7 |

0.02 |

0.008 |

ND |

ND |

1.0 |

ND |

ND |

| Ph8 |

0.04 |

0.091 |

0.012 |

ND |

1.3 |

ND |

ND |

| Ph9 |

0.07 |

0.015 |

0.004 |

ND |

2.8 |

ND |

ND |

| Ph10 |

0.03 |

0.062 |

0.003 |

ND |

0.3 |

ND |

ND |

| Ph11 |

0.01 |

0.038 |

0.003 |

ND |

1.0 |

ND |

ND |

| Ph12 |

0.18 |

0.177 |

0.018 |

ND |

1.3 |

ND |

ND |

| Ph13 |

0.02 |

0.017 |

0.010 |

ND |

0.3 |

ND |

ND |

| On1 |

0.91 |

1.46 |

0.181 |

0.015 |

2.5 |

ND |

ND |

| On2 |

0.33 |

0.209 |

0.087 |

ND |

2.6 |

ND |

ND |

| On3 |

0.03 |

0.006 |

0.005 |

ND |

1.0 |

ND |

ND |

| On4 |

0.71 |

1.50 |

0.040 |

0.020 |

10.3 |

ND |

ND |

| On5 |

0.14 |

0.766 |

0.051 |

0.153 |

2.3 |

ND |

ND |

| On6 |

0.08 |

0.266 |

0.038 |

0.009 |

1.8 |

ND |

ND |

| On7 |

0.02 |

0.010 |

0.004 |

ND |

1.0 |

ND |

ND |

| On8 |

1.36 |

0.953 |

0.428 |

0.023 |

1.4 |

0.058 |

ND |

| On9 |

0.02 |

0.007 |

0.003 |

ND |

1.0 |

ND |

ND |

| On10 |

0.03 |

0.115 |

0.008 |

ND |

1.2 |

ND |

ND |

| On11 |

0.03 |

0.134 |

0.006 |

ND |

1.7 |

ND |

ND |

| On12 |

0.04 |

0.027 |

ND |

ND |

0.2 |

ND |

ND |

| On13 |

0.08 |

0.023 |

0.010 |

ND |

0.8 |

ND |

ND |

| On14 |

0.11 |

0.054 |

0.096 |

ND |

3.2 |

ND |

ND |

| On15 |

0.17 |

0.052 |

0.107 |

ND |

5.0 |

ND |

ND |

| On16 |

0.03 |

0.056 |

0.005 |

ND |

0.2 |

ND |

ND |

| On17 |

0.07 |

0.017 |

0.005 |

ND |

3.0 |

ND |

ND |

| On18 |

0.03 |

0.065 |

0.004 |

0.007 |

0.4 |

ND |

ND |

| On19 |

0.06 |

0.030 |

0.002 |

ND |

0.9 |

ND |

0.023 |

| On20 |

0.03 |

0.060 |

0.005 |

0.006 |

0.4 |

ND |

ND |

| On21 |

0.03 |

0.056 |

0.004 |

ND |

1.0 |

Below LOQ |

ND |

| On22 |

0.01 |

0.010 |

0.013 |

ND |

0.9 |

ND |

ND |

| On23 |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

| On24 |

ND |

0.003 |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

| On25 |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

0.9 |

ND |

ND |

| On26 |

ND |

0.015 |

0.004 |

ND |

0.4 |

ND |

ND |

| On27 |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

0.2 |

ND |

ND |

Discussion

In this quality control study

of 40 A. paniculata herbal products sourced from pharmacies worldwide and

online retailers available to Swiss consumers, the majority were found to be of poor

quality, including

products claiming to have been made according to Good Manufacturing Practice guidelines.

All products except one, which was delivered without a label, contained A. paniculata.

For most products, the quantity of

andrographolide was substantially lower than that indicated on the product’s labelling

and only one third met the recommended daily therapeutic dose of andrographolide

for upper respiratory tract infection. The presence of quercetin in two products

further complicated accurate andrographolide quantification. Quercetin, which was

listed as an ingredient on the label of these two products, is commonly used as

a food supplement for its potential antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties

and is regarded as safe at moderate doses (≤1000 mg/day) [22]. However, it may have

been used as an

adulterant to falsely enhance the peak of andrographolide, as both compounds share

the same retention time when

analysed with the pharmacopoeial reference method. Alarmingly, three products purchased

online contained toxic contaminants: one exceeded European safety limits for mercury

and two others contained pesticide residues of strychnine and butralin, substances

banned or heavily regulated in the European Union, Switzerland and the US [21].

Even though the measured doses of each contaminant were well below the lethal dose,

this finding represents a serious breach of safety standards [20]. As no safe threshold

has been established for butralin or strychnine, it cannot be excluded that the

two products in which these pesticides were detected may pose health risks, even

at low exposure levels.

The levels of the characteristic

compounds – namely andrographolide, andrographiside and neoandrographolide – varied

among the products analysed. This finding is consistent with previous studies, and

is likely attributable to differences in extraction methods and plant parts used

[23, 24]. Standardising the extraction process would help ensure consistent composition

and quality of plant-based products. Our findings of inaccurate labelling of A.

paniculata-containing products are consistent with previous studies on other

food supplement products purchased online or from a single country. In these studies,

25% to 88% of herbal products, including Curcuma longa (turmeric)and

Lavandula angustifolia (lavender), were inaccurately labelled due to suspected

adulteration and/or a quantity of the active substance that was not within ±10%

of the labelled dose [25–27]. Other studies of products containing Hypericum

perforatum and Rhodiola rosea showed inaccurate labelling and the presence

of contaminants in products sold as herbal food supplements, but not in products

containing the same herb but sold as herbal medicinal products [28, 29]. Regarding

contaminants, a case of strychnine contamination has previously been reported in

Panax ginseng (ginseng)-containing herbal products [30]. In our study, although the

mercury level exceeded the maximum authorised limit in one herbal product, the overall

proportion of affected samples remained lower than that reported in a large-scale

study assessing the quality of herbal products purchased in China, where nearly

one third of products contained at least one heavy metal above safety thresholds

[31]. A similar difference was previously reported, with herbal food supplements

manufactured in China showing higher heavy metal levels than those from North America

[32]. While our findings

only apply to products containing A. paniculata, similar issues are likely

to affect other herbal food supplements.

In most countries, herbal food

supplements can be purchased over the counter in pharmacies, health food stores

or on the internet, like other food supplements. Unlike herbal medicinal products,

which are regulated by the same drug regulators as any other medical drug, herbal

food supplements do not require proof of safety or efficacy before being marketed

in Switzerland, Europe or the US [3]. In addition, once marketed, the quality of

herbal food supplements is not controlled, in contrast to herbal products marketed

as herbal medicinal products. Manufacturers in certain countries such as the US

are expected to comply with Good Manufacturing Practice guidelines and to display

this on their labelling. However, our findings showed that even A. paniculata-containing

products with Good Manufacturing Practice labels can be inaccurate. The distinction

between regulations applied to herbal food supplements and herbal medicinal products

may not be clear to the general public, making it difficult for consumers to assess

the quality of herbal food supplements they buy. Physicians and pharmacists should

be informed of this and educate patients about the risks of buying herbal food supplements

or other products online, particularly due to the risk of ingesting contaminants

and residues that they would not otherwise encounter. Clinicians should also actively

enquire about herbal

food supplement consumption by their patients, particularly in situations of unexplained

symptoms or suspected intoxication. Moreover, it is

possible that a prescribed herbal product fails to have the

expected effect on the clinical course of a disease because

it is underdosed and the prescriber and the patient have no

way of knowing that this is the reason for lack of efficacy.

To improve consumer safety, stronger regulation

of locally marketed herbal food supplements is needed. Since A. paniculata

is only available as a herbal food supplement, introducing a herbal medicinal product

version would ensure higher product quality. However, applying the same strict standards

as herbal medicinal products could disadvantage small manufacturers, reducing product

availability and pushing consumers towards lower-quality alternatives. A balanced

solution would be third-party certification to verify product quality, helping consumers

make informed choices. In the US, voluntary certification programmes such as ConsumerLab.com,

NSF International and US Pharmacopeia already help ensure the quality of herbal

food supplements. Expanding similar initiatives globally could enhance consumer

protection while maintaining accessibility to herbal products.

We acknowledge several limitations of our study.

First, these 40 products are not meant to be representative of all herbal products

sold online or in pharmacies in Switzerland or abroad. The overall sample size was

modest, with most brands of A. paniculata-containing products represented

by only one batch sample, which may not capture overall variability. Second, the

pharmacies and websites where these samples were obtained were selected opportunistically

rather than randomly. While it is not feasible to analyse all such products on the

market at such a high standard, our results indicate a pattern that we believe would

hold with a larger sample size. Additionally, our analyses were conducted with on

an international sample using two robust analytical methods, ensuring the accuracy

and validity of our results. Finally, since we only quantified andrographolide in

solid forms, our findings may not apply to products in other forms.

Our study highlights the poor quality of most A.

paniculata-containing herbal products sold as herbal food supplements, even

when compliance with Good Manufacturing Practice is claimed. The frequent mislabelling

of A. paniculata-containing products should alert clinicians, pharmacists

and regulatory authorities. The general public should be aware of the risks associated

with ordering products online, including ingesting potential contaminants and residues.

We emphasise the need for stricter yet pragmatic regulation of the global herbal

food supplements market and, amid varying regulatory frameworks worldwide, we propose

that a standardised labelling system be used to identify products whose quality

has been independently verified.

Data sharing statement

Deidentified data derived

from analysed samples will be made available upon reasonable request from qualified

researchers whose proposed use of the data has been approved by the investigators

and participating institutions. Data will be shared after publication, under a formal

data sharing agreement, and only for samples collected and processed in accordance

with applicable ethical and regulatory approvals.

Declaration of use of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the authors

– who are not native English speakers – used ChatGPT for proofreading. After using

this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility

for the content of the publication.

Professor Pierre-Yves Rodondi

Institute

of Family Medicine

University

of Fribourg

Route des Arsenaux 4

CH-1700 Fribourg

pierre-yves.rodondi[at]unifr.ch

and

Dr Emerson Ferreira Queiroz

Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences

of Western Switzerland

University of Geneva

CMU

CH-1206 Geneva

emerson.ferreira[at]unige.ch

References

1. Patriota P, Guessous I, Marques-Vidal P. Dietary patterns according to vitamin supplement

use. A cross-sectional study in Switzerland. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2022 Oct;92(5-6):331–41.

10.1024/0300-9831/a000679

2. Health Products Regulatory Authority [Internet]. Herbal medicines: regulatory information

Dublin (Ireland): HPRA; 2014 [cited 2025 Oct 14]. Available from: http://www.hpra.ie/homepage/medicines/regulatory-information/medicines-authorisation/herbal-medicines/information-for-the-public-thmps

3. Directive 2002/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 June 2002

on the Approximation of the Laws of the Member States Relating to Food Supplements. Off

J Eur Union. L 183 No. 51-5 (2002).

4. Directive 2004/24/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 March 2004

amending, as regards traditional herbal medicinal products, Directive 2001/83/EC on

the Community code relating to medicinal products for human use. Off J Eur Union.

L 136 No. 85-90 (2004).

5. Finnish Food Authority [Internet]. Establishing novel food status of a food Helsinki

(Finland): Finnish Food Authority; 2023 [cited 2025 Oct 14]. Available from: https://www.ruokavirasto.fi/en/foodstuffs/food-sector/ainesosat-ja-sisalto/novel-foods/establishing-novel-food-status-of-a-food/

6. Orhan N, Gafner S, Blumenthal M. Estimating the extent of adulteration of the popular

herbs black cohosh, echinacea, elder berry, ginkgo, and turmeric - its challenges

and limitations. Nat Prod Rep. 2024 Oct;41(10):1604–21. 10.1039/d4np00014e doi: https://doi.org/10.1039/D4NP00014E

7. Gafner S, Blumenthal M, Foster S, Cardellina JH 2nd, Khan IA, Upton R. Botanical Ingredient

Forensics: Detection of Attempts to Deceive Commonly Used Analytical Methods for Authenticating

Herbal Dietary and Food Ingredients and Supplements. J Nat Prod. 2023 Feb;86(2):460–72.

10.1021/acs.jnatprod.2c00929

8. Coon JT, Ernst E. Andrographis paniculata in the treatment of upper respiratory tract infections: a systematic review of safety

and efficacy. Planta Med. 2004 Apr;70(4):293–8. 10.1055/s-2004-818938

9. Hu XY, Wu RH, Logue M, Blondel C, Lai LY, Stuart B, et al. Andrographis paniculata (Chuān Xīn Lián) for symptomatic relief of acute respiratory tract infections in

adults and children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017 Aug;12(8):e0181780.

10.1371/journal.pone.0181780

10. Tanwettiyanont J, Piriyachananusorn N, Sangsoi L, Boonsong B, Sunpapoa C, Tanamatayarat P,

et al. Use of Andrographis paniculata (Burm.f.) Wall. ex Nees and risk of pneumonia in hospitalised patients with mild

coronavirus disease 2019: A retrospective cohort study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 Aug;9:947373.

10.3389/fmed.2022.947373

11. Puri A, Saxena R, Saxena RP, Saxena KC, Srivastava V, Tandon JS. Immunostimulant agents

from Andrographis paniculata. J Nat Prod. 1993 Jul;56(7):995–9. 10.1021/np50097a002

12. Songvut P, Suriyo T, Panomvana D, Rangkadilok N, Satayavivad J. A comprehensive review

on disposition kinetics and dosage of oral administration of Andrographis paniculata, an alternative herbal medicine, in co-treatment of coronavirus disease. Front Pharmacol.

2022 Aug;13:952660. 10.3389/fphar.2022.952660

13. Wagner L, Cramer H, Klose P, Lauche R, Gass F, Dobos G, et al. Herbal Medicine for

Cough: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Forsch Komplementmed. 2015;22(6):359–68.

10.1159/000442111

14. Raynor DK, Dickinson R, Knapp P, Long AF, Nicolson DJ. Buyer beware? Does the information

provided with herbal products available over the counter enable safe use? BMC Med.

2011 Aug;9(1):94. 10.1186/1741-7015-9-94

15. Karioti A, Timoteo P, Bergonzi MC, Bilia AR. A Validated Method for the Quality Control

of Andrographis paniculata Preparations. Planta Med. 2017 Oct;83(14-15):1207–13. 10.1055/s-0043-113827

16. Fibigr J, Šatínský D, Solich P. Current trends in the analysis and quality control

of food supplements based on plant extracts. Anal Chim Acta. 2018 Dec;1036:1–15. 10.1016/j.aca.2018.08.017

17. Anastassiades M, Lehotay SJ, Stajnbaher D, Schenck FJ. Fast and easy multiresidue

method employing acetonitrile extraction/partitioning and “dispersive solid-phase

extraction” for the determination of pesticide residues in produce. J AOAC Int. 2003;86(2):412–31.

10.1093/jaoac/86.2.412

18. Allen LV, Bassani GS, Elder EJ, Parr AF. Strength and stability testing for compounded

preparations. Rockville (USA) [USP]. U S Pharmacop. 2015.

19. Kumar S, Singh B, Bajpai V. Andrographis paniculata (Burm.f.) Nees: traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacological properties and

quality control/quality assurance. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021 Jul;275:114054. 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114054

20. Parker AJ, Lee JB, Redman J, Jolliffe L. Strychnine poisoning: gone but not forgotten.

Emerg Med J. 2011 Jan;28(1):84. 10.1136/emj.2009.080879

21. Smith E, Azoulay D, Tuncak B. Lowest common denominator : how the proposed EU-US trade

deal threatens to lower standards of protection from toxic pesticides. London, UK:

Center for International Environmental Law; 2015.

22. Aghababaei F, Hadidi M. Recent Advances in Potential Health Benefits of Quercetin.

Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023 Jul;16(7):1020. 10.3390/ph16071020

23. Avula B, Katragunta K, Tatapudi KK, Wang YH, Ali Z, Chittiboyina AG, et al. Phytochemical

analysis of phenolics and diterpene lactones in Andrographis paniculata plant samples and dietary supplements. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2025 Sep;262:116866.

10.1016/j.jpba.2025.116866

24. Ruan LJ, Yan BX, Song SS, Yun-Qiu W, Liu XH, Yao CY, et al. Harmonizing international

quality standards for Andrographis paniculata: A comparative analysis of content determination methods across pharmacopeias. J

Pharm Biomed Anal. 2024 Mar;240:115924. 10.1016/j.jpba.2023.115924

25. Booker A, Frommenwiler D, Reich E, Horsfield S, Heinrich M. Adulteration and Poor

Quality of Ginkgo biloba Supplements. J Herb Med. 2016;6(2):79–87. 10.1016/j.hermed.2016.04.003

26. Sorng S, Balayssac S, Danoun S, Assemat G, Mirre A, Cristofoli V, et al. Quality assessment

of Curcuma dietary supplements: complementary data from LC-MS and 1H NMR. J Pharm

Biomed Anal. 2022 Apr;212:114631. 10.1016/j.jpba.2022.114631

27. Jalil B, Heinrich M. Pharmaceutical quality of herbal medicinal products and dietary

supplements - a case study with oral solid formulations containing Lavandula species.

Eur J Pharm Sci. 2025 May;208:107042. 10.1016/j.ejps.2025.107042

28. Booker A, Agapouda A, Frommenwiler DA, Scotti F, Reich E, Heinrich M. St John’s wort

(Hypericum perforatum) products - an assessment of their authenticity and quality. Phytomedicine. 2018 Feb;40:158–64.

10.1016/j.phymed.2017.12.012

29. Booker A, Jalil B, Frommenwiler D, Reich E, Zhai L, Kulic Z, et al. The authenticity

and quality of Rhodiola rosea products. Phytomedicine. 2016 Jun;23(7):754–62. 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.10.006

30. Filipiak-Szok A, Kurzawa M, Szłyk E. Determination of toxic metals by ICP-MS in Asiatic

and European medicinal plants and dietary supplements. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2015 Apr;30:54–8.

10.1016/j.jtemb.2014.10.008

31. Luo L, Wang B, Jiang J, Fitzgerald M, Huang Q, Yu Z, et al. Heavy metal contaminations

in herbal medicines: determination, comprehensive risk assessments, and solutions.

Front Pharmacol. 2021 Jan;11:595335. 10.3389/fphar.2020.595335

32. Genuis SJ, Schwalfenberg G, Siy AK, Rodushkin I. Toxic element contamination of natural

health products and pharmaceutical preparations. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e49676. 10.1371/journal.pone.0049676

Appendix

The appendix is available for download as a separate file at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4728.