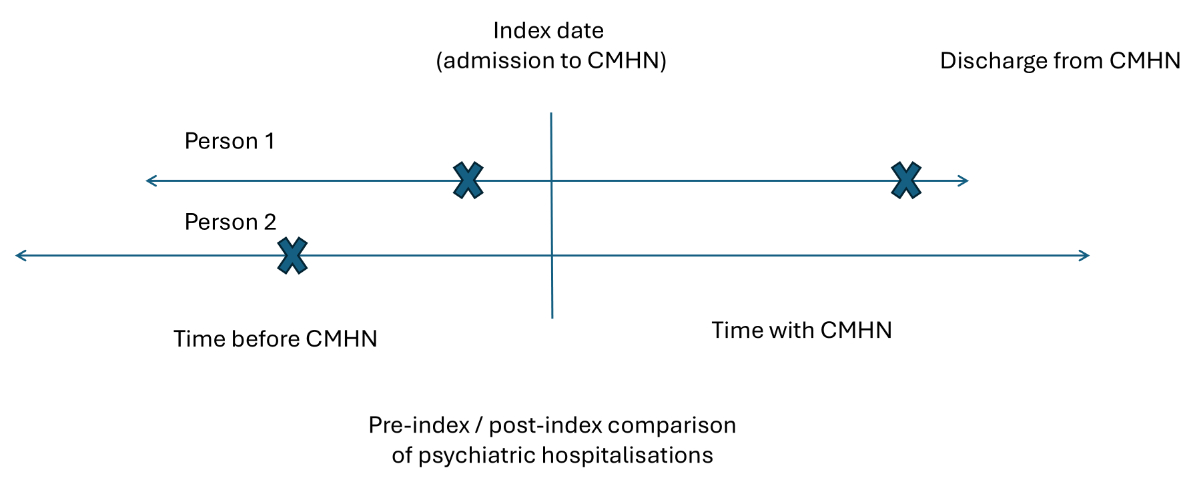

Figure 1Illustration of the mirror-image design used in this study with two exemplary cases. Each “X” represents a hospitalisation.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4692

Community mental health services play an essential role in the care of people with mental disorders. While the number of inpatient psychiatric beds is steadily declining in many countries, the number of psychiatric admissions continues to rise. This development results in high bed turnover rates and reduced average lengths of stay [1]. After discharge, many patients face substantial challenges, including an increased risk of suicide, difficulties managing daily life, stigma and social isolation [2–5]. These factors may contribute to symptom exacerbation or readmission. The risk of readmission is particularly high within the first 30 days after discharge [6, 7].

Factors associated with psychiatric readmissions include clinical aspects (e.g. diagnosis of severe mental disorder; comorbidities; psychotic symptoms; suicidality; and aspects of service use, e.g. previous admissions, non-adherence to medication and limited access to community-based care) and sociodemographic characteristics such as age and living situation [7–11]. In Canada and Europe, 30-day readmission rates vary between 9% and 15% [7, 12]. In Switzerland alone, CHF 849 million – representing 32.2% of all psychiatric health costs covered by compulsory insurance – are spent annually on inpatient psychiatric care [13]. Reducing psychiatric hospitalisations is therefore of both social and economic relevance.

Against this background, community mental health services have gained increasing attention for their potential to reduce the duration and frequency of hospital stays [14, 15], thereby mitigating the negative effects of hospitalisation and relieving pressure on inpatient systems. Studies indicate positive effects of community-based care on reducing psychiatric symptoms and improving psychosocial outcomes [16]. However, evidence is not unequivocal. O’Donnell et al. [16] found that only a minority of reviewed studies examined hospital readmissions and results were inconsistent: while some showed reductions, others did not. Similarly, Bechdolf et al. [17] reported that although home treatment reduced inpatient length of stay compared to hospital-based treatment, it did not lower readmission rates. In line with these mixed findings, Leach et al. [18] concluded that the available evidence on the impact of community mental health nursing on hospitalisation remains inconclusive.

Nurses are key providers within these community mental health services, providing targeted, individualised care that addresses both medical and psychosocial needs [19, 20]. In Switzerland, community mental health nursing has grown significantly in recent years. In addition to a considerable number of freelance community mental health nurses [21], nonprofit home care organisations (‘Spitex’) have expanded their psychiatric services and integrated a growing number of mental health nurses [22]. Access to community mental health nursing services generally requires a prescription by a physician or psychiatrist. Participation is voluntary, and clients may decide whether to accept community mental health nursing services. Eligible clients are individuals of any age group who experience limitations in daily functioning, self-care or social participation due to mental health problems.

Community mental health nursing services provide comprehensive, person-centred support in people’s homes, tailored to their individual situations. Interventions typically include counselling and psychoeducation, support with daily structure and self-management, crisis intervention, medication management and coordination with other health and social services [23]. The overarching goal is to enable people to live as independently as possible, but also to strengthen coping skills, support recovery and foster social participation. Preventing hospitalisation is one possible effect of community mental health nursing, but not its sole or primary aim. Despite the growing relevance of community mental health nursing, there is still limited evidence on its effect on psychiatric (re-)hospitalisations [18, 24]. Further empirical research on community mental health nursing is required to inform the planning and development of community mental health services [18, 25].

To address methodological challenges in evaluating real-world interventions such as community mental health nursing, mirror-image methods offer a valuable approach. As a variant of self-controlled study designs, mirror-image methods compare outcomes before and after the start of an intervention, with each individual serving as their own control [26, 27]. Originally established in pharmacoepidemiology, this design has also been applied to psychosocial interventions [28–30]. Its main advantage lies in its high external validity since it reflects routine care settings. These characteristics make mirror-image designs particularly suitable when randomised controlled trials are unfeasible due to ethical, logistical or financial constraints [26]. In this context, the use of routine observational data is especially valuable, as it enables pragmatic and cost-efficient evaluations at scale, contributing to health systems research and planning [31].

However, mirror-image studies are not without limitations. Results may be biased by regression to the mean or expectation effects – particularly when the intervention is initiated following a crisis such as associated with hospitalisation. In such cases, observed improvements may partly reflect a natural return to baseline rather than the true effect of the intervention. Furthermore, one period of observation is often retrospective, which can introduce recall and selection biases [26]. Nonetheless, mirror-image studies remain a useful and feasible strategy for evaluating complex interventions under real-world conditions.

Against this backdrop, the present study aims to contribute to the evidence base on community mental health nursing by a) evaluating the effect of admission to community mental health nursing services on psychiatric hospitalisation among people with mental disorders, and b) identifying risk factors associated with psychiatric hospitalisations during the course of community mental health nursing care.

We conducted a pre-registered naturalistic observational study (OSF: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/TDG83) and analysed data with mirror-image methods. This self-controlled design compares outcomes during two periods of equal duration – before and after the initiation of an intervention – with each individual serving as their own control [32]. In our study, the start of community mental health nursing care was defined as the index date. For each person, the duration of community mental health nursing care was mirrored backward to define a comparable pre-index period. The length of the periods before and after the initiation of the intervention were exactly the same per person and, thus, overall across all participants in terms of person-time.

Psychiatric hospitalisations were assessed in both timeframes. Figure 1 illustrates the design using two exemplary cases (Person 1 and Person 2), each with different durations of community mental health nursing care. Hospitalisations are indicated by “X” marks. We deviated from the pre-registered study protocol by using Incidence Rate Ratios as outcome measures rather than Wilcoxon Effect Sizes.

Figure 1Illustration of the mirror-image design used in this study with two exemplary cases. Each “X” represents a hospitalisation.

In this study, community mental health nursing was provided through Swiss nonprofit home care organisations (“Spitex”), which deliver both general and psychiatric nursing care and employ nurses and nursing assistants. Community mental health nurses are tertiary-educated and work in an outreach capacity. Interventions are tailored to individual needs and the length, duration and frequency of client visits vary according to their needs. Needs assessment for patients with mental disorders is carried out with the Resident Assessment Instrument Community Mental Health (interRAI CMH) [33], Swiss version [34]. The interRAI CMH was validated in several international studies and is widely used in Switzerland and internationally [35]. The assessment can be used at admission, discharge, every 6 months depending on length of stay, and after a change in the person’s status that requires nursing care plan modification [35]. Based on these assessments, community mental health nurses carry out various interventions including counselling and coordination, medication management, training on coping skills, crisis intervention, and support for daily structure and social functioning.

We used anonymised routine data from the HomeCareData register and merged it with data from the Medical Statistics of Hospitals provided by the Federal Statistical Office (FSO) of Switzerland. Each dataset contains an anonymised personal linkage key, generated by the FSO using a secure encryption process based on patient information. This key is unique to each individual and consistent across datasets, allowing for accurate record linkage without revealing personal identities. The authors obtained written permission to obtain the datasets.

HCD is the only register centralising client-level home care data in Switzerland. The database was implemented in 2016 [36] and includes sociodemographic and clinical data as well as care needs and planned services, assessed by nurses using the interRAI. The transfer of data by nonprofit home care organisations to HCD is not mandatory; therefore, the register contains data from 176 of 492 (36%) nonprofit home care organisations (as of 2022). For this study, we extracted all interRAI CMH first assessments from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2022 and the date of discharge from community mental health nursing services. Data was exported on 30 January 2024 by the University of Bern.

The MS is a mandatory nationwide register containing data on all hospitalisations in Swiss hospitals. The FSO collects sociodemographic information on patients as well as administrative data and medical information. For this study, data was extracted from the MS for HCD patients who had at least one inpatient stay in a psychiatric hospital between 2019 and 2022. The time periods of the two datasets do not overlap completely. The MS dataset also covers the year 2019 in order to include possible hospitalisations and to extend the retrospective observation period.

The primary outcome was psychiatric hospitalisation, defined as an inpatient admission to a psychiatric hospital (as recorded in the MS dataset), regardless of length of stay, type of ward or compulsory status. Each admission was counted as one hospitalisation. For the mirror-image analysis, the outcome was whether a psychiatric hospitalisation occurred during the mirror-image periods before and after the index date. For each person, we identified the psychiatric hospitalisation closest to the index date (start of community mental health nursing care). If multiple hospitalisations were recorded, only the one temporally nearest to the index date was retained. For the regression analysis, the outcome was a binary variable of whether a hospitalisation occurred in the two years prior to community mental health nursing start (Yes/No). Other variables used for regression analyses (sex, age group, diagnosis, living situation, hospitalisation in the last two years, compulsory admission, day structure, crisis intervention) were extracted from the HCD.

The two datasets were linked using the anonymised personal linkage key. The HCD dataset included individuals who entered community mental health nursing care between 2020 and 2022 and had a completed interRAI CMH assessment and were aged at least 18 years. We linked the data from the MS to this dataset, if a person had at least one inpatient stay in a psychiatric hospital between 2019 and 2022. This resulted in a dataset which contained data from people who were and were not hospitalised.

To prepare the datasets for linkage, several preprocessing steps were carried out:

The time difference between community mental health nursing admission and hospitalisations before or after community mental health nursing admission was calculated in MS Excel.

For individuals with no documented community mental health nursing discharge (coded as 99), the last available date of the MS (31 December 2022) was assigned as a censored discharge date. The duration of community mental health nursing care, which also defined the mirror-image period, was calculated by subtracting the community mental health nursing admission date from the discharge or censoring date. To ensure consistency, mirror-image periods were restricted to the observation window (1 January 2019 to 31 December 2022), which could result in shorter periods than the actual community mental health nursing duration.

Psychiatric diagnoses were recorded as free text in the HCD dataset and had to be recoded before analysis. This was conducted primarily using base R (v4.3.0) [37], including regular expression-based text processing to extract ICD-10 F diagnoses from free-text fields. If an F coding (according to ICD-10) was available, this was selected as a priority. Available free-text entries were assigned to the corresponding ICD-10 codes. Missing diagnoses were marked as “NA” (not available).

All analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (v4.5.1) [37]. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the sample and hospitalisation patterns. Some variables contained missing values which are indicated in the respective tables. No imputation or other procedures were applied; all analyses were conducted using available data only. The exception is the secondary analysis as described below.

The primary analysis was a mirror-image analysis of the hospitalisation outcome as defined above. Post-index outcomes were compared with pre-index outcomes for each service user. The mirror-image period was defined as the individual community mental health nursing utilisation period. To minimise the risk of overestimating the intervention effect, we conducted a post-hoc sensitivity analysis excluding individuals who had been hospitalised within 60 days prior to the index date. A similar approach has been used in earlier studies – for instance, Adamus et al. [28] applied a 90-day exclusion window. However, feedback from experts at international conferences suggested that a 90-day exclusion may be too conservative. Given the well-documented elevated risk of readmission within 30 days of discharge [7, 12], we chose a 60-day cut-off as a pragmatic compromise. In figure 1, Person 1’s hospitalisation occurred shortly before community mental health nursing admission and would be excluded in sensitivity analyses due to its proximity (within 60 days) to the index date.

To explore potential risk factors of psychiatric hospitalisation as secondary analysis, we conducted univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses including a range of sociodemographic and clinical variables. The independent variables comprised psychiatric diagnosis (reference category: F5, F7, F8, F9), living alone (Yes/No), male sex (Yes/No), age group (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–65, >65 years), previous psychiatric hospitalisation within the last two years (Yes/No), compulsory admission prior to community mental health nursing start (Yes/No), need for structured daily activities (Yes/No) and whether a crisis intervention had been recorded (Yes/No). Multiple imputation was used to handle missing data, applying the mice package [39] in R with five imputed datasets.

This study is reported in accordance with the RECORD statement to ensure transparency and completeness in the use of routinely collected health data [40].

The cantonal ethics committee of Bern, Switzerland, reviewed and approved the study plan (Project-ID 2023–01529).

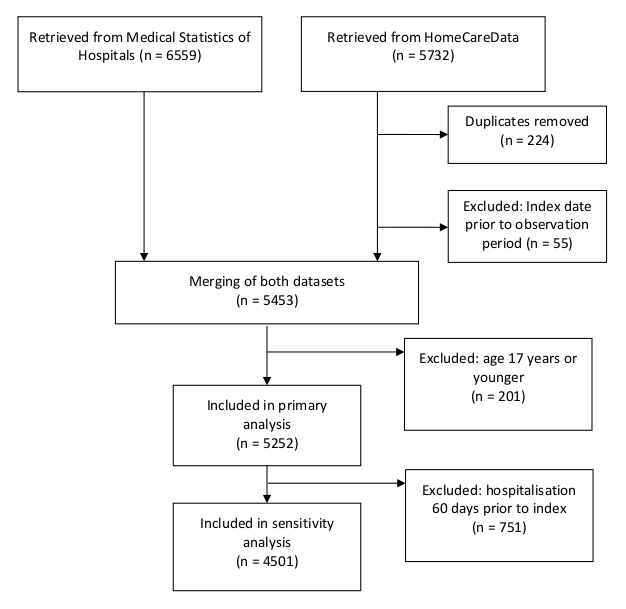

Figure 2 shows the flowchart of the data management process. The sample characteristics are shown in table 1. The study sample consisted of 5252 individuals, with a mean age of 52 years (SD: 18). The majority of participants were female (66%, n = 3460). The most prevalent psychiatric diagnosis was affective disorders (F3), accounting for 31% (n = 1605) of cases. Other common diagnoses were neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders (F4) at 9% (n = 480), schizophrenic or psychotic disorders (F2) at 7% (n = 386) and substance-abuse disorders (F1) at 5% (n = 279). In 37% (n = 1963) of cases, a diagnosis was missing.

Figure 2Flow diagram of data management.

Table 1Demographic and clinical characteristics at community mental health nursing start date (index date) (n = 5252)

| Age in years, mean (SD) | (Whole sample) | 52 (18) |

| Age group, n (%) | 18–24 years | 354 (7%) |

| 25–34 years | 742 (14%) | |

| 35–44 years | 821 (16%) | |

| 45–54 years | 921 (17%) | |

| 55–65 years | 1051 (20%) | |

| >65 years | 1363 (26%) | |

| Sex, n (%) | Female | 3460 (66%) |

| Male | 1788 (34%) | |

| Other | 4 (0%) | |

| ICD-10 diagnosis, n (%) | F0: Organic, incl. symptomatic mental disorder | 105 (2%) |

| F1: Substance-abuse disorder | 279 (5%) | |

| F2: Schizophrenic or psychotic disorder | 386 (7%) | |

| F3: Affective disorder | 1605 (31%) | |

| F4: Neurotic, stress and somatoform disorder | 480 (9%) | |

| F5: Behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors | 51 (1%) | |

| F6: Personality disorder | 237 (5%) | |

| F7: Mental retardation | 19 (0%) | |

| F8: Disorders of psychological development | 27 (1%) | |

| F9: Unspecified mental disorder | 88 (2%) | |

| Other non-psychiatric diagnoses | 12 (0%) | |

| NA | 1963 (37%) | |

| Living situation, n (%) | Alone | 2790 (53%) |

| With partner | 989 (19%) | |

| With partner and children | 624 (12%) | |

| With children only | 340 (6%) | |

| With others | 509 (10%) | |

| Mirror-image period in days, mean (SD) | (Whole sample) | 297 (207) |

| Hospitalisation in 2 years prior to community mental health nursing start, n (%) | Yes | 2900 (55%) |

| No | 2165 (41%) | |

| NA | 187 (4%) | |

| Compulsory admission, n (%) | Yes | 870 (17%) |

| No | 4048 (77%) | |

| NA | 334 (6%) | |

| Crisis intervention necessary, n (%) | Yes | 2112 (40%) |

| No | 3081 (59%) | |

| NA | 59 (1%) | |

| Support in day structure necessary, n (%) | Yes | 3438 (65%) |

| No | 1761 (34%) | |

| NA | 53 (1%) |

NA: not available; SD: standard deviation.

The majority of cases (55%, n = 2000) had a history of psychiatric hospitalisation in the 2 years prior to start of community mental health nursing. Compulsory admissions were reported in 17% (n = 870) of cases.

During the mirror-image period, 18% (n = 965) had a hospitalisation only prior to the index date, while 8% (n = 433) were hospitalised only after the index date. An additional 7% (n = 358) experienced hospitalisations both before and after the index date. The majority of individuals (67%, n = 3496) had no hospitalisations during the mirror-image period (table 2).

Table 2Psychiatric hospitalisations during mirror-image period (n = 5252).

| Hospitalisation | n (%) |

| Pre-index only | 965 (18.4%) |

| Post-index only | 433 (8.2%) |

| Pre- and post-index | 358 (6.8%) |

| No hospitalisation | 3496 (66.6%) |

The incidence rate ratio (IRR) of the mirror-image analyses is presented in table 3. The results indicate a significant reduction in psychiatric hospitalisations. Following the initiation of community mental health nursing, the IRR was 0.60 (95% CI: 0.55–0.65), which translates to a 40% reduction in hospital admissions compared to the pre-index admission rate in the primary analysis. The sensitivity analyses which excluded people with psychiatric admission within 60 days before the index date resulted in a non-significant IRR of 0.97 (95% CI: 0.87–1.09).

Table 3Mirror-image analysis of number of inpatient psychiatric hospitalisations.

| Sample size (n) | Pre-index (n) | Post-index (n) | IRR | 95% CI | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Primary analysis | 5252 | 1323 | 791 | 0.60 | 0.55 | 0.65 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 4501 | 633 | 615 | 0.97 | 0.87 | 1.09 |

CI: confidence interval; IRR: incidence rate ratio; n: number of service users included in the analysis.

The results of the regression analyses are reported in table 4. Male sex (OR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.00–1.43, p = 0.05), a diagnosis of substance-use disorder (F1; OR: 1.69, 95% CI: 1.26–2.28, p <0.001), a diagnosis of schizophrenia and related disorders (F2; OR: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.02–1.72, p = 0.04), a history of hospitalisation in the two years prior to community mental health nursing start (OR: 3.75, 95% CI: 3.12–4.51, p <0.001) and a history of compulsory admission (OR: 2.30, 95% CI: 1.93–2.74, p <0.001) were associated with higher odds of hospitalisation. In addition, requiring help with daily structure (OR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.01–1.38, p = 0.04) and receiving crisis intervention (OR: 1.28, 95% CI: 1.11–1.49, p <0.001) were also associated with an increased risk, while being older than 65 years was associated with lower odds of hospitalisation (OR: 0.77, 95% CI: 0.64–0.92, p <0.001). In contrast, in the multivariable model, only a history of hospitalisation within the two years prior to community mental health nursing start (OR: 3.48, 95% CI: 2.74–4.43, p <0.001) and a history of compulsory admission (OR: 1.57, 95% CI: 1.25–1.99, p <0.001) remained significant independent risk factors.

Table 4Univariable and multivariable logistic regression.

| Univariable logistic regression | Multivariable logistic regression | |||||

| Odds ratio | p-value | 95% confidence interval | Odds ratio | p-value | 95% confidence interval | |

| Sex: male (vs female) | 1.19 | 0.05 | 1.00–1.43 | 1.04 | 0.78 | 0.81–1.34 |

| Age: 18–24 yr | 1.26 | 0.10 | 0.96–1.67 | 1.09 | 0.68 | 0.73–1.62 |

| Age: 25–34 yr | 0.91 | 0.39 | 0.73–1.13 | 0.88 | 0.45 | 0.62–1.23 |

| Age: 35–44 yr | 1.10 | 0.34 | 0.90–1.34 | 0.94 | 0.70 | 0.68–*1.29 |

| Age: 45–54 yr | 1.12 | 0.24 | 0.93–1.35 | 0.90 | 0.51 | 0.66–1.23 |

| Age: 55–65 yr | 1.09 | 0.36 | 0.91–1.30 | 1.03 | 0.86 | 0.76–1.39 |

| Age: >65 yr | 0.77 | 0.00 | 0.64–0.92 | Reference | ||

| Diagnosis: F0 | 0.82 | 0.14 | 0.62–1.07 | 0.91 | 0.73 | 0.52–1.59 |

| Diagnosis: F1 | 1.69 | 0.00 | 1.26–2.28 | 1.31 | 0.27 | 0.78–2.40 |

| Diagnosis: F2 | 1.32 | 0.04 | 1.02–1.72 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 0.57–1.77 |

| Diagnosis: F3 | 0.91 | 0.28 | 0.77–1.08 | 0.93 | 0.76 | 0.58–1.48 |

| Diagnosis: F4 | 0.92 | 0.51 | 0.73–1.17 | 0.94 | 0.82 | 0.58–1.53 |

| Diagnosis: F6 | 1.07 | 0.73 | 0.73–1.57 | 1.07 | 0.83 | 0.57–2.04 |

| Other diagnoses | 0.79 | 0.25 | 0.53–1.18 | Reference | ||

| Living alone (vs not) | 1.02 | 0.84 | 0.88–1.18 | 1.06 | 0.69 | 0.80–1.39 |

| Hospitalisation in 2 years prior to community mental health nursing start (vs not) | 3.75 | 0.00 | 3.12–4.51 | 3.48 | 0.00 | 2.74–4.43 |

| Compulsory admission prior to community mental health nursing start (vs not) | 2.30 | 0.00 | 1.93–2.74 | 1.57 | 0.00 | 1.25–1.99 |

| Day structure necessary (vs not) | 1.18 | 0.04 | 1.01–1.38 | 1.01 | 0.96 | 0.81–1.24 |

| Crisis intervention (vs not) | 1.28 | 0.00 | 1.11–1.49 | 1.10 | 0.33 | 0.91–1.33 |

| Intercept | NA | NA | NA | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.04–0.12 |

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effectiveness of community mental health nursing on psychiatric hospitalisations of people with mental disorders in Switzerland. The findings indicate a significant reduction in psychiatric hospitalisations following the initiation of community mental health nursing. However, this effect was not confirmed in the sensitivity analysis excluding individuals with hospitalisations 60 days prior to the community mental health nursing start date, where the IRR was close to unity.

One of the central limitations of mirror-image studies is the risk of regression to the mean due to natural fluctuations in illness severity [26, 28]. Given our sensitivity analysis results, in our study, we cannot rule out that part of the observed reduction in hospital admissions reflects functional improvements unrelated to community mental health nursing services. Despite the likely regression to the mean, our findings are consistent with previous studies showing that community mental health services can reduce both the duration [14] and frequency [15, 30] of hospitalisations. Earlier reviews have, however, concluded that evidence specific to community mental health nursing remains limited or inconclusive. This observation also applies to our study. Due to the lack of a control group, the study design used here cannot determine exactly how large the regression to the mean effect actually is. We see it as a particular challenge for research in the field of community mental health nursing to find out how significant this effect is, and which service user characteristics are associated with it. Similar to findings from studies on anti-psychotic long-acting injectables, where reductions in hospitalisations observed in pre–post designs may partly reflect regression to the mean but nevertheless also capture real-world effectiveness [41], we hypothesise that community mental health nursing may be particularly beneficial for service users with recent hospitalisations. This assumption should be addressed in secondary analyses or in future studies designed to disentangle regression to the mean effects from true intervention effects. In this context, the choice of the exclusion window is crucial: our sensitivity analysis applied a 60-day cut-off based on clinical considerations and stakeholder feedback, but it remains uncertain whether this adequately captures the period most affected by regression to the mean. Future studies should therefore systematically examine different cut-off dates to assess the robustness of results.

The statistical regression analysis identified a history of psychiatric admissions and compulsory treatments as risk factors for hospitalisations during community mental health nursing care, while sociodemographic and diagnostic factors showed no significant associations. These findings align with existing international research, which consistently highlights prior hospital use as one of the strongest risk factors of future admissions (e.g. [7–10]). The association between compulsory admission history and subsequent hospitalisation points to a subgroup of individuals with potentially more severe or unstable illness trajectories. The results suggest that community mental health nursing services should pay particular attention to individuals with a history of inpatient and compulsory treatment. Tailored care models and early nursing interventions supporting the transitions from hospital to the community may be particularly beneficial for these subgroups to prevent psychiatric hospitalisations [42].

Our findings regarding the sociodemographic characteristics of community mental health nursing service users are in line with previous Swiss studies. Burr and Richter [43] identified several factors associated with use of community mental health nursing services in Switzerland, including difficulties with instrumental activities of daily living, use of informal care, emergency service utilisation, psychotropic medication use, female sex and living without a partner. Similarly, the majority of our sample was female and living alone and frequently required support with day structure. Hegedüs and Abderhalden [21] reported comparable results in their study on freelance mental health nurses in Switzerland: most clients lived alone, around 70% were women and affective disorders were the most common diagnoses. These similarities suggest that both freelance nurses and community mental health nursing services in Switzerland serve largely overlapping client populations. Notably, the high proportion of patients with affective disorders is somewhat unusual for community mental health services. In many countries, patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (F2) are among the most frequent community mental health services utilisers [44, 45]. In Switzerland, however, these patients are typically treated in outpatient clinics [21] rather than by community mental health nursing, which may explain the observed diagnostic imbalance in our sample.

While these patterns provide insight into who currently receives community mental health nursing care, they also raise important questions about who does not and why. Evidence suggests that low utilisation rates of outpatient mental health services may not be primarily driven by patient-related factors. For instance, Jaffe et al. [46] showed that only 23% of inpatients with psychosis or bipolar disorder in a German-speaking region of Switzerland reported receiving outpatient psychotherapy, despite clinical indications. Stulz et al. [47] further demonstrated that outpatient service utilisation decreases significantly with increasing travel time to the outpatient clinic, underscoring the importance of service accessibility. Taken together, these findings highlight the potential of geographically accessible, home-based services such as community mental health nursing to reach underserved populations. Community mental health nursing services, which have increasingly integrated psychiatric nursing in recent years [22], are well-positioned to fill this gap.

This study is based on a large, naturalistic sample drawn from routine healthcare data, enhancing the external validity of the findings. This design allows for generalisations to real-world settings and increases the practical relevance of the results for mental health care; nevertheless, it is important to note that findings are specific to individuals who actually receive community mental health nursing services.

However, several limitations must be considered when interpreting the findings. Comprehensive nationwide data on psychiatric home care is currently lacking in Switzerland [48]. As a result, we relied on the HCD, which has inherent constraints. The data predominantly represents the German- and Italian-speaking regions of Switzerland, where inpatient services are relatively abundant. In contrast, the French-speaking region – with a more outpatient-oriented system and fewer psychiatric inpatient beds – is underrepresented. Moreover, the voluntary nature of data submission to the HCD register introduces a risk of selection bias at the organisational level. It remains unclear whether organisations that contribute data differ systematically from those that do not. This may affect the representativeness of the sample and limit the generalisability of the findings.

In addition, psychiatric diagnoses were missing in a substantial proportion of cases, reflecting inconsistencies in documentation. This may limit the accuracy of diagnostic subgroup analyses in the regression analysis. In order to improve data quality in community mental health nursing, expanding the HCD dataset and improving data quality should be prioritised in future efforts particularly in terms of diagnostic information and regional representation.

Parts of the study period (2020–2022) coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have influenced psychiatric hospitalisation patterns. In contrast to other countries, Switzerland imposed no strict lockdowns, but rather a gradual introduction and relief of measures depending on current pandemic developments. However, access to inpatient care was temporarily restricted and individuals may have avoided hospitalisation due to infection concerns [49]. These factors could have contributed to a general reduction in hospital admissions, independent of community mental health nursing effects.

This study provides novel insights into the effectiveness of community mental health nursing in Switzerland. The findings highlight the potential role of community mental health nursing in reducing psychiatric hospitalisations and underscore its growing relevance within the mental healthcare system. In addition, the study demonstrates the feasibility of using linked routine data to evaluate real-world mental health interventions.

Given the limitations of mirror-image designs, future research should disentangle true intervention effects from regression to the mean, systematically examine different cut-off periods and identify subgroups who benefit most, such as individuals with recent or compulsory hospitalisations.

In addition, future research should investigate whether the observed reductions in hospital admissions also affect the length of inpatient stays, a question that remains unanswered in the current evidence base. Moreover, assessing the economic impact of community mental health nursing – particularly in terms of potential cost savings for the healthcare system – would provide valuable insights for policymakers and service planners.

Considering the psychosocial focus of community mental health nursing, further research should also explore outcomes beyond hospitalisation, such as clients’ ability to structure daily life, maintain social relationships and engage in meaningful community participation. Finally, improving the quality and completeness of national datasets – especially regarding diagnostic information and outpatient care – will be essential for evaluating the full impact of community-based mental health services across Switzerland.

Individual deidentified participant data is not available from the authors. However, the datasets used in this study – drawn from the Swiss HomeCareData (HCD) and Medical Statistics of Hospitals (MS) registers – are accessible for research purposes upon request. Researchers may submit a data access application directly to the respective data providers: Spitex Schweiz (for HCD data) and the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (for MS data). The authors are not permitted to share the data themselves and are required to delete all data upon completion of the project, in accordance with data use agreements. The study protocol is publicly available via the Open Science Framework (OSF) at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/TDG83.

We acknowledge the technical support by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office, Neuchâtel, Switzerland and by SwissRDL - Medical Registries and Data Linkage, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland. We also acknowledge the support by Spitex Switzerland, Bern, Switzerland. Finally, we are grateful to the reviewers whose constructive feedback helped us improve the quality of this manuscript.

AH is supported by a grant from the Stiftung Lindenhof Bern, Switzerland.

Both authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript was disclosed.

1. Thornicroft G, Deb T, Henderson C. Community mental health care worldwide: current status and further developments. World Psychiatry. 2016 Oct;15(3):276–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20349

2. Aaltonen K, Sund R, Hakulinen C, Pirkola S, Isometsä E. Variations in Suicide Risk and Risk Factors After Hospitalization for Depression in Finland, 1996-2017. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024 May;81(5):506–15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.5512

3. Chung D, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Wang M, Swaraj S, Olfson M, Large M. Meta-analysis of suicide rates in the first week and the first month after psychiatric hospitalisation. BMJ Open. 2019 Mar;9(3):e023883. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023883

4. Keogh B, Callaghan P, Higgins A. Managing preconceived expectations: mental health service users experiences of going home from hospital: a grounded theory study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2015 Nov;22(9):715–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12265

5. Redding A, Maguire N, Johnson G, Maguire T. What is the Lived Experience of Being Discharged From a Psychiatric Inpatient Stay? Community Ment Health J. 2017 Jul;53(5):568–77. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-017-0092-0

6. Durbin J, Lin E, Layne C, Teed M. Is readmission a valid indicator of the quality of inpatient psychiatric care? J Behav Health Serv Res. 2007 Apr;34(2):137–50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-007-9055-5

7. Katschnig H, Straßmayr C, Endel F, Berger M, Zauner G, Kalseth J, et al.; CEPHOS-LINK study group. Using national electronic health care registries for comparing the risk of psychiatric re-hospitalisation in six European countries: opportunities and limitations. Health Policy. 2019 Nov;123(11):1028–35. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.07.006

8. Donisi V, Tedeschi F, Salazzari D, Amaddeo F. Pre- and post-discharge factors influencing early readmission to acute psychiatric wards: implications for quality-of-care indicators in psychiatry. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;39:53–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.10.009

9. Sfetcu R, Musat S, Haaramo P, Ciutan M, Scintee G, Vladescu C, et al. Overview of post-discharge predictors for psychiatric re-hospitalisations: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Psychiatry. 2017 Jun;17(1):227. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1386-z

10. Tulloch AD, David AS, Thornicroft G. Exploring the predictors of early readmission to psychiatric hospital. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2016 Apr;25(2):181–93. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796015000128

11. Yamaguchi S, Ojio Y, Koike J, Matsunaga A, Ogawa M, Tachimori H, et al. Associations between readmission and patient-reported measures in acute psychiatric inpatients: a study protocol for a multicenter prospective longitudinal study (the ePOP-J study). Int J Ment Health Syst. 2019 Jun;13(1):40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-019-0298-3

12. Vigod SN, Kurdyak PA, Seitz D, Herrmann N, Fung K, Lin E, et al. READMIT: a clinical risk index to predict 30-day readmission after discharge from acute psychiatric units. J Psychiatr Res. 2015 Feb;61:205–13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.12.003

13. Schuler D, Tuch A, Sturny I, Peter C. Psychische Gesundheit. Kennzahlen 2022. Neuchâtel: Schweizerisches Gesundheitsobservatorium; 2024.

14. Wanchek TN, McGarvey EL, Leon-Verdin M, Bonnie RJ. The effect of community mental health services on hospitalization rates in Virginia. Psychiatr Serv. 2011 Feb;62(2):194–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.62.2.pss6202_0194

15. Lee CC, Liem SK, Leung J, Young V, Wu K, Wong Kenny KK, et al. From deinstitutionalization to recovery-oriented assertive community treatment in Hong Kong: what we have achieved. Psychiatry Res. 2015 Aug;228(3):243–50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.106

16. O Donnell R, Savaglio M, Vicary D, Skouteris H. Effect of community mental health care programs in Australia: a systematic review. Aust J Prim Health. 2020 Dec;26(6):443–51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1071/PY20147

17. Bechdolf A, Bühling-Schindowski F, Nikolaidis K, Kleinschmidt M, Weinmann S, Baumgardt J. [Evidence on the effects of crisis resolution teams, home treatment and assertive outreach for people with mental disorders in Germany, Austria and Switzerland - a systematic review]. Nervenarzt. 2022 May;93(5):488–98. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-021-01143-8

18. Leach MJ, Jones M, Bressington D, Jones A, Nolan F, Muyambi K, et al. The association between community mental health nursing and hospital admissions for people with serious mental illness: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2020 Feb;9(1):35. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01292-y

19. Heslop B, Wynaden D, Tohotoa J, Heslop K. Mental health nurses’ contributions to community mental health care: an Australian study. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2016 Oct;25(5):426–33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12225

20. International Council of Nurses. The global mental health nursing workforce: Time to prioritize and invest in mental health and wellbeing. Geneva, Switzerland: International Council of Nurses; 2022.

21. Hegedüs A, Abderhalden C. [Needs of clients cared for by community mental health nurses]. Psychiatr Prax. 2011 Nov;38(8):382–8.

22. Richter D, Hepp U, Jäger M, Adorjan K. Mental health care services in Switzerland - the post-pandemic state. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2025;37(3-4):315–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2025.2479596

23. Expertengruppe Psychiatriespitex. Grundlagenpapier Ambulante Psychiatrische Pflege. Bern; 2025.

24. Brooker C, Repper J, Booth A. The effectiveness of community mental health nursing: a review. J Clin Effectiveness. 1996;1(1):44–50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/eb020835

25. van Genk C, Roeg D, van Vugt M, van Weeghel J, Van Regenmortel T. Current insights of community mental healthcare for people with severe mental illness: A scoping review. Front Psychiatry. 2023 Apr;14:1156235. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1156235

26. Fagiolini A, Rocca P, De Giorgi S, Spina E, Amodeo G, Amore M. Clinical trial methodology to assess the efficacy/effectiveness of long-acting antipsychotics: randomized controlled trials vs naturalistic studies. Psychiatry Res. 2017 Jan;247:257–64. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.11.044

27. Hallas J, Pottegård A. Use of self-controlled designs in pharmacoepidemiology. J Intern Med. 2014 Jun;275(6):581–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12186

28. Adamus C, Zürcher SJ, Richter D. A mirror-image analysis of psychiatric hospitalisations among people with severe mental illness using Independent Supported Housing. BMC Psychiatry. 2022 Jul;22(1):492. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04133-5

29. Levy E, Mustafa S, Naveed K, Joober R. Effectiveness of Community Treatment Order in Patients with a First Episode of Psychosis: A Mirror-Image Study. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63(11):766- 73. 3 doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743718777389

0. Díaz-Fernández S, Frías-Ortiz DF, Fernández-Miranda JJ. Mirror image study (10 years of follow-up and 10 of standard pre-treatment) of psychiatric hospitalizations of patients with severe schizophrenia treated in a community-based, case-managed programme. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Engl Ed). 2022;15(1):47–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsmen.2022.01.002

31. Djalali S, Markun S, Rosemann T. Routinedaten – das ungenutzte Potenzial in der Versorgungsforschung. Praxis (Bern). 2017;106(7):365–72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1024/1661-8157/a002630

32. Rohde C, Siskind D, de Leon J, Nielsen J. Antipsychotic medication exposure, clozapine, and pneumonia: results from a self-controlled study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2020 Aug;142(2):78–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13142

33. Hirdes JP, Ikegami N, Curtin-Telegdi N, Yamauchi K, Rabinowitz T, Smith TF, et al. interRAI Community Mental Health (CMH) Assessment Form and User’s Manual, (Standard English Edition), 9.22022.

34. Hirdes JP, Ikegami N, Curtin-Telegdi N, Yamauchi K, Rabinowitz T, Smith TF, et al. interRAI Community Mental Health Schweiz (interRAI CMHSchweiz) Bedarfsabklärungsinstrument und Handbuch, Version 9.3.1, Deutschsprachige Ausgabe für die Schweiz. 2022.

35. Hirdes JP, van Everdingen C, Ferris J, Franco-Martin M, Fries BE, Heikkilä J, et al. The interRAI Suite of Mental Health Assessment Instruments: An Integrated System for the Continuum of Care. Front Psychiatry. 2020 Jan;10:926. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00926

36. Wagner A, Schaffert R, Dratva J. Adjusting Client-Level Risks Impacts on Home Care Organization Ranking. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 May;18(11):5502. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115502

37. R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2021.

38. Wickham H, François R, Henry L, Müller K, Vaughan D. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. R package version 114. 2023.

39. van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(3):1–67. doi: https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v045.i03

40. Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, Harron K, Moher D, Petersen I, et al.; RECORD Working Committee. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015 Oct;12(10):e1001885. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885

41. Kishimoto T, Hagi K, Kurokawa S, Kane JM, Correll CU. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis of randomised, cohort, and pre-post studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021 May;8(5):387–404. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00039-0

42. Hegedüs A, Kozel B, Richter D, Behrens J. Effectiveness of Transitional Interventions in Improving Patient Outcomes and Service Use After Discharge From Psychiatric Inpatient Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2020 Jan;10:969. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00969

43. Burr C, Richter D. Predictors of community mental health nursing services use in Switzerland: results from a representative national survey. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021 Dec;30(6):1640–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12917

44. Azimi S, Uddin N, Dragovic M. Access to urban community mental health services: does geographical distance play a role? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2025 Apr;60(4):849–57. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-024-02779-y

45. Iwanaga M, Usui K, Sato S, Nakanishi K, Nishiuchi E, Shimodaira M, et al. Service use patterns in community mental health outreach: A sequence analysis of the first 12-month longitudinal data. PLoS One. 2025 Sep;20(9):e0332437. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0332437

46. Jaffé ME, Loew SB, Meyer AH, Lieb R, Dechent F, Lang UE, et al. Just Not Enough: Utilization of Outpatient Psychotherapy Provided by Clinical Psychologists for Patients With Psychosis and Bipolar Disorder in Switzerland. Health Serv Insights. 2024 Feb;17:11786329241229950. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/11786329241229950

47. Stulz N, Dubno B, Gebhardt R, Hepp U. [Distance Decay Effects in a Swiss Mental Health Services System]. Psychiatr Prax. 2024 Jul;51(5):270–6.

48. Tuch A, Jörg R, Stulz N, Heim E, Hepp U. Angebotsstrukturen in der psychiatrischen Versorgung: Regionale Unterschiede im Versorgungsmix. Neuchâtel: Schweizerisches Gesundheitsobservatorium; 2024.

49. Rachamin Y, Jäger L, Schweighoffer R, Signorell A, Bähler C, Huber CA, et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Healthcare Utilization in Switzerland Was Strongest Among Young Females-Retrospective Study in 2018-2020. Int J Public Health. 2023 May;68:1605839. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2023.1605839