Passive RSV immunisation using nirsevimab in neonatal care: a structured multidisciplinary

approach and immunisation data from a Swiss tertiary centre

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4689

Katalin

Kalyaa,

Jehudith

Fontijnb,

Flurina Famosa,

Dirk Basslerb,

Nicole Ochsenbein-Kölblea,

Ladina Vonzuna

a Department of Obstetrics, University Hospital Zurich,

Switzerland

b Department of Neonatology,

University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland

Summary

BACKGROUND: Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection is a major cause of

severe lower respiratory tract infections in newborns and young infants,

especially during the winter season from October to March. In Switzerland, RSV infection

represents a leading cause of hospital admissions among newborns. Since October

2024, a long-acting monoclonal antibody, nirsevimab (Beyfortus®), has been

available in Switzerland for standard care in newborns.

OBJECTIVES: This paper presents a multidisciplinary, standardised protocol for

the administration of nirsevimab, as well as immunisation data

from the first season of application in 2024/25 at a tertiary centre in

Switzerland.

METHODS: A protocol for implementing the RSV immunisation strategy was

developed at University Hospital Zurich by a multidisciplinary team of obstetricians,

neonatologists, nurses, from in- and outpatient services. The focus was on prenatal

counselling during outpatient consultations as well as inpatient procedures on

maternity and neonatology wards. The goal was to provide expectant parents with

consistent information by different healthcare professionals. Neonatal immunisation

data from the first season in 2024/25 (25 October to 31 March ) were retrieved

from patient charts (Yes/No) in a retrospective, quality control, observational

cohort study. All newborns discharged from the maternity ward or the

neonatology unit of our centre were included in the analysis.

RESULTS: The protocol included early and multidisciplinary parental

education, offering consistent oral and written information, as well as

opportunities to discuss their questions regarding the new immunisation, ensured

informed consent and enabled timely administration of nirsevimab by healthcare professionals

in the obstetrics and neonatology units. Over the 2024/25 season, 78% of the newborns

were immunised before leaving hospital care: 78% (588/758) of newborns discharged

home from the maternity ward were immunised and 82% (125/153) of those

discharged home from the neonatology unit were immunised.

CONCLUSION: The implementation of passive RSV immunisation was overall

successful with an immunisation rate of around 80% for the first season in 2024/25.

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a ubiquitous seasonal virus and a leading cause

of bronchiolitis and pneumonia in infants aged below one year, particularly during

the winter season. National and international epidemiological data confirm that RSV

contributes to significant paediatric morbidity, accounting for a large proportion

of hospitalisations among newborns [1]. The clinical burden and risk of severe RSV

infection is particularly high in the first month of life, due to the immature immune

system and narrow airways of newborns. Traditionally prevention has relied on hygiene

measures and administration of monoclonal antibodies approved for high-risk infants

only [2].

The recent development and regulatory approval of nirsevimab (Beyfortus®), a long-acting monoclonal antibody with demonstrated efficacy and safety, provides

a transformative opportunity in neonatal infectious disease prevention. Clinical trials

and observational studies have demonstrated an up to 80% reduction in severe RSV-related

lower respiratory tract infections, 77% fewer hospitalisations and 86% fewer intensive

care admissions among infants who received nirsevimab [3–6]. These benefits were consistent

across populations, including full-term and preterm infants. Safety data from over

3700 infants showed no increase in adverse events compared to placebo [7].

Based on these findings, the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH / Bundesamt für Gesundheit [BAG]) and the Federal Vaccination Commission (FVC / Eidgenössische Kommission für Impffragen [EKIF]) in collaboration with the various expert societies have recommended among

others a routine passive immunisation strategy with nirsevimab for all newborns born

between October and March, to be administered within the first week of life or as

soon as possible thereafter [7]. The costs of nirsevimab are covered by mandatory

health insurance and embedded within the Swiss Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRG) system

[8]. The latter incorporation was confirmed on 5 September 2024, leaving very little

time to inform relevant healthcare workers and expectant parents about, and prepare

them for, this new passive immunisation option for newborns in the upcoming 2024/25

RSV season. To achieve high immunisation coverage without generating extensive workload

in the inpatient setting, clear parental communication and seamless interdisciplinary

collaboration were required.

This paper presents a pragmatic implementation report developed at University Hospital

Zurich, integrating the RSV immunisation strategy into routine perinatal care, emphasising

parental education, interprofessional collaboration and clinical efficiency to minimise

administrative burden. Additionally, immunisation data of the first RSV season with

nirsevimab, 2024/25, are shown and discussed in detail.

Materials and methods

Multidisciplinary implementation strategy for nirsevimab

The protocol for implementation of the RSV immunisation

strategy was developed at University Hospital Zurich by a multidisciplinary and

interprofessional team of obstetricians, neonatologists and nurses regarding in-

and outpatient services. The goal was to achieve, from the first day of the protocol’s

implementation, high immunisation rates with nirsevimab for newborns leaving

our centre. To this end, we focused on the following:

- Consistent

information for the expectant parents by different healthcare workers (doctors,

midwives, nurses), based on existing information material, i.e. the fact sheets

of the Federal Office of Health [9].

- Consistent

information for the expectant parents at multiple time points (prenatally,

after delivery at the ward, during the stay at the maternity ward or

neonatology).

- Activation

of various information channels (oral, written i.e. leaflets, smartphone applications).

- Minimalised

use of administrative and time resources for each discipline (especially

considering primary information and subsequent questions by parents).

- Clinical

efficiency of the workflows of nirsevimab administration (written parental consent).

- Easy

access to nirsevimab for parents who had not reached a decision by the time of

hospital discharge, by implementing an outpatient consultation at University

Hospital Zurich’s neonatology department.

- Reduction

of workload of paediatric outpatient clinics by implementing an

outpatient consultation at University Hospital Zurich’s neonatology department for

undecided parents (this consideration was made with special regard to the beginning

of the programme, where paediatricians in the outpatient practices were responsible

for the vaccination of all children born between April and September 2024 in

their practice).

Nirsevimab immunisation data for the 2024/25 season

This is a retrospective, quality control, observational

cohort study. All newborns born alive at University Hospital Zurich between 25 October

2024 and 31 March 2025, discharged home from the maternity ward as well as all

newborns discharged from the neonatology unit in this time period, were offered

nirsevimab, and were included in this data analysis. Exclusion criteria

included stillbirths, neonatal deaths, newborns receiving palliative care and

those transferred to other hospitals for follow-up.

Following the recommendations of the Swiss

Federal Office of Public Health / Federal Vaccination Commission, all newborns

without contraindications (e.g. haemophilia or thrombocytopenia) were

recommended nirsevimab 50 mg intramuscularly in their first days of life

(application possible immediately after birth or as soon as possible thereafter).

For newborns discharged home from the

maternity ward, data were retrieved every second week from patient charts. For newborns

discharged home from

the neonatology unit, an overall immunisation coverage was calculated, as the length

of stay varied and thus the application of immunisation did not occur in a timely

standardised manner. Documented administration of nirsevimab (Yes/No) before discharge

was coded. Additionally, maternal vaccination with Abrysvo®, the maternal RSV

vaccine, was coded if application occurred between the 32nd and 36th

week of pregnancy and at least two weeks before delivery. If Abrysvo® had been

given according to the mentioned conditions, nirsevimab was not additionally

administered to the newborns and they were coded immunised. Newborns immunised

during their first two weeks of life at the outpatient service of University

Hospital Zurich’s neonatology department, as described in the implementation

strategy, were considered ‘immunised’ for analysis too.

Data were retrieved anonymously from the

electronic patient chart KISIM© (version V5.6.0.14, Cistec AG©) and / or

Perinat (Klinisches Informationssystem, version 7.0.0.89, © University Hospital

Zurich 2025).

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft®

Excel® for Microsoft 365 MSO (Version 2402 Build 16.0.17328.20550) 64-bit. Categorical

data are presented as counts (n) with percentages (%).

This study does not fall within the scope

of the Swiss Human Research Act. The study was reported, but approval of the

project by a Swiss Ethics Committee was not required as it was designed as a retrospective,

quality control, observational study and only targeted anonymous data were

obtained (Req-2025-00202).

Results

Multidisciplinary protocol for nirsevimab

The protocol developed at University Hospital Zurich by a multidisciplinary team from

obstetrics, neonatology, nursing and outpatient services is schematically shown in

figure 1 and its key features are as follows:

Prenatal information and counselling of parents

During pregnancy consultations by obstetricians and/or midwives, all expectant parents

are informed about passive RSV immunisation. Printed fact sheets by the Swiss Federal

Office of Public Health are included in the maternity documents sent by post to every

woman planning to deliver at our centre. Additionally, these fact sheets are placed

in the hospital’s digital maternity pass/application, available to every woman who

has had a consultation at our centre [10].

Delivery and postpartum period in the delivery room

After delivery, however still in the delivery room, midwives reinforce the information

about RSV immunisation during the initial newborn assessments (ideally as a reminder

with the standardised vitamin K administration). Parents receive an RSV consent form,

containing key information about nirsevimab, and are asked to return it signed before

the neonatal routine check before discharge from the hospital. The form contains the

following options for parents to choose from: “Yes, I want nirsevimab to be administered”,

“No, I do not want nirsevimab to be administered” or “I have not decided yet”.

Maternity ward (postpartum care)

Any remaining parental concerns are addressed by the attending obstetricians and/or

nurses/midwives during the daily rounds. Nurses verify that the signed consent form

is present at discharge. At the routine neonatal examination by neonatology before

discharge (usually day two or three after birth), parents are again informed and asked

about their decision concerning nirsevimab administration. If parents agree, nirsevimab

is prescribed and documented in the vaccination booklet by the neonatologist and administered

by the ward nurses/midwives. If parents decline the nirsevimab administration, a note

is made in the report for the paediatrician, asking that the topic be brought up

in the follow-up visits. If parents remain undecided, they are referred to the outpatient

neonatology clinic (see point 5).

Neonatology unit (inpatient newborns)

Parents of hospitalised newborns are informed about RSV immunisation as part of discharge

planning. With consent, nirsevimab is administered prior to discharge.

Outpatient neonatology clinic

For parents who are undecided or prefer more time to consider, an appointment is scheduled

with neonatology specialists within the week after discharge. After counselling, if

consent is obtained, the immunisation is administered and documented in the child’s

immunisation booklet.

Figure 1Schematic presentation of the passive

respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) immunisation strategy for newborns

implemented at University Hospital Zurich in inpatients and outpatients during

the 2024/25 season, with emphasis on parental information by multiple channels,

healthcare workers and time points in pregnancy and postpartum. *FOPH / BAG:

Federal Office of Public Health / Bundesamt für Gesundheit; ** OB/GYN:

obstetrics/gynaecology physicians; *** NEO: neonatology physicians.

RSV immunisation data for the 2024/25 season

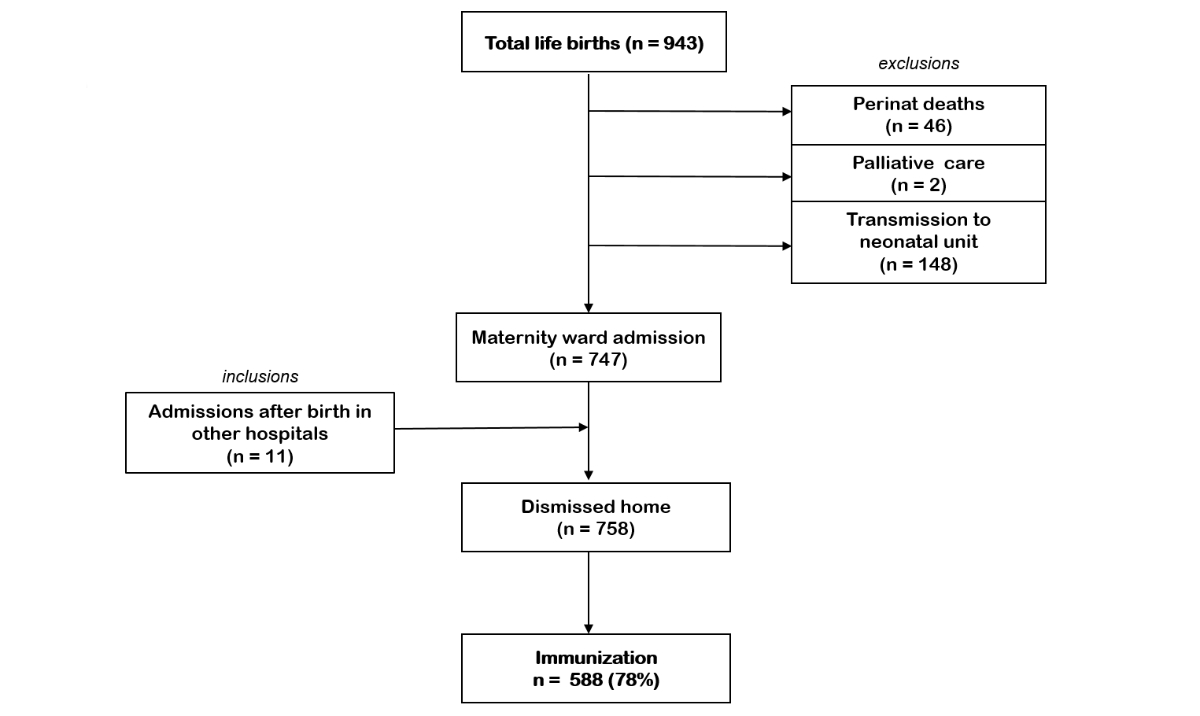

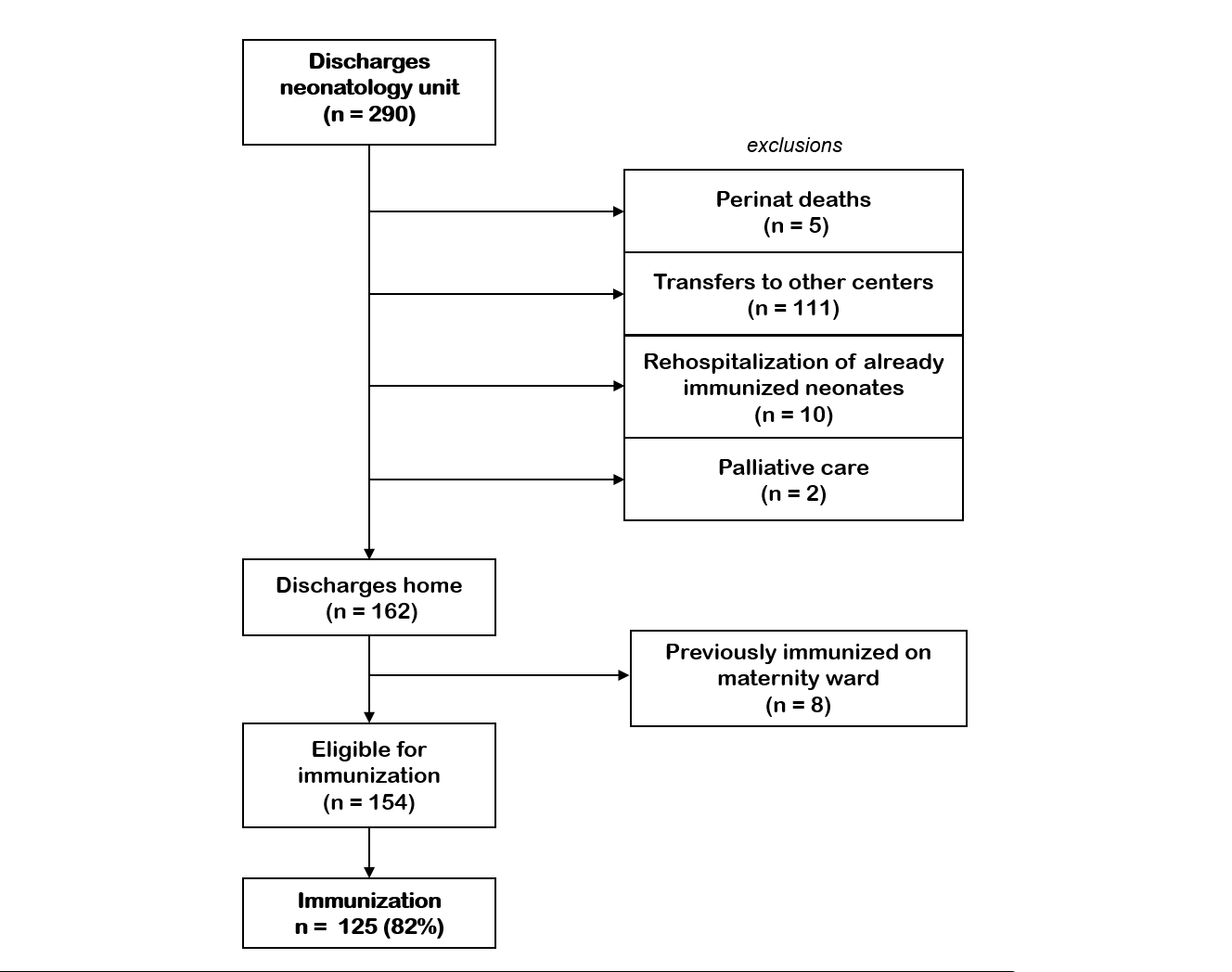

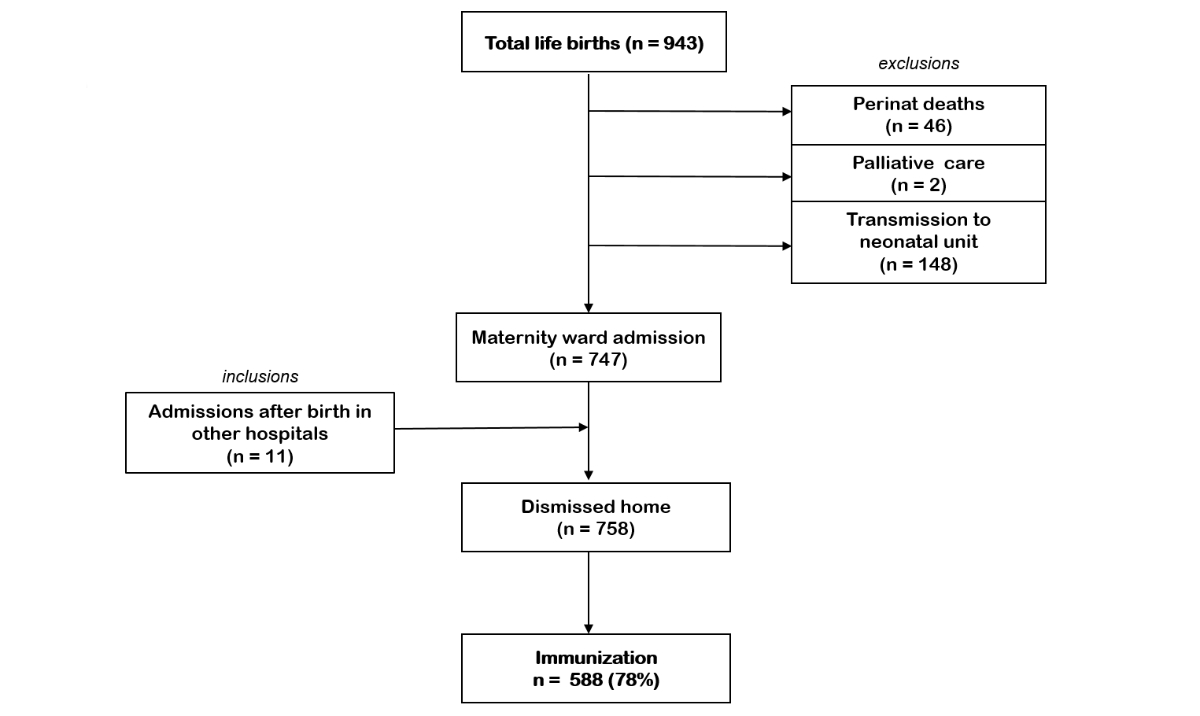

During the study period, 758 newborns were discharged

home from the maternity ward with an RSV immunisation coverage of 78% (n = 588).

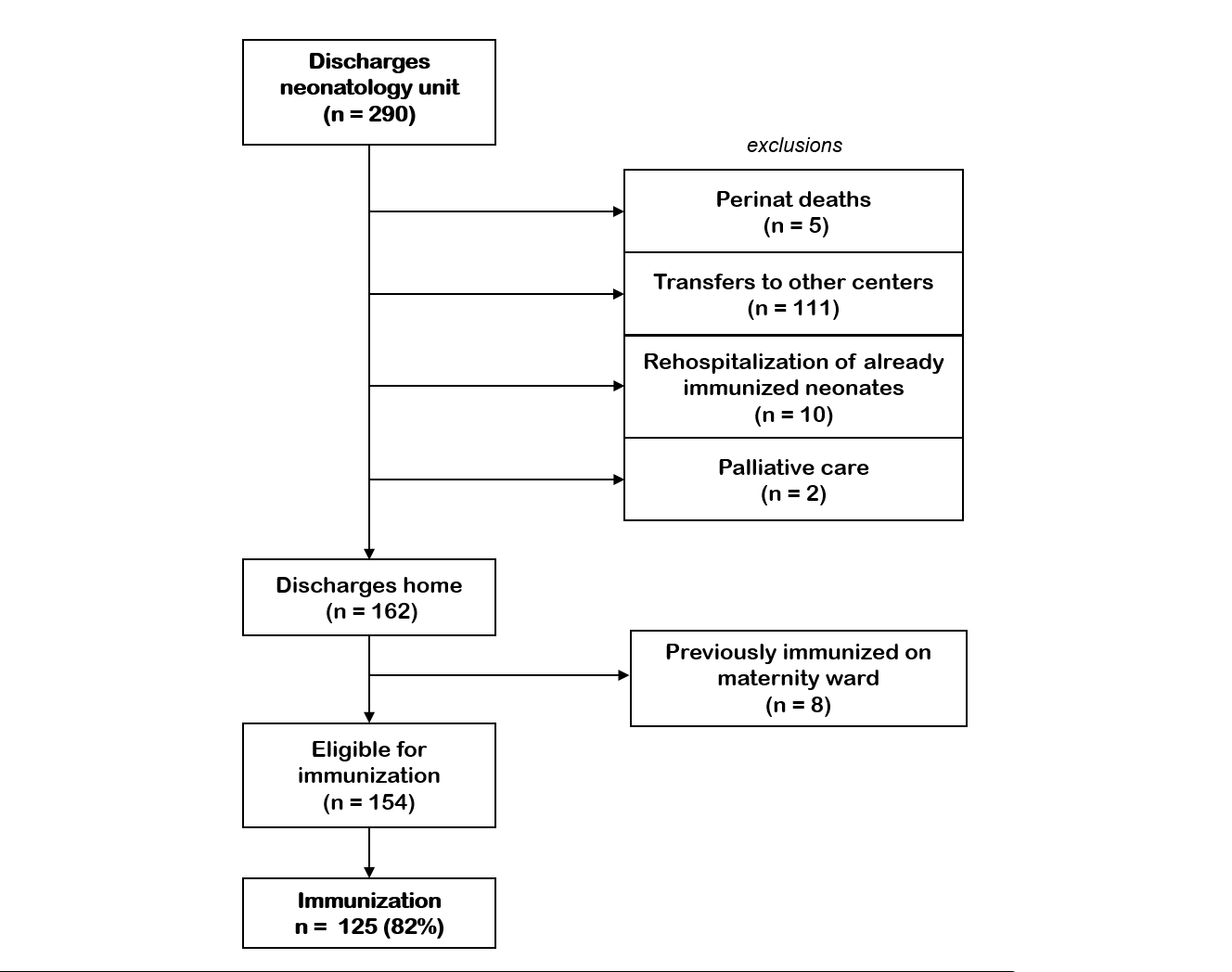

A further 153 newborns were discharged home from the neonatology unit, of whom 125

were immunised (82%) (figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2Inclusions and exclusions of immunisation

with nirsevimab during the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) 2024/25 season in the

maternity ward at University

Hospital Zurich.

Figure 3Inclusions and exclusions of immunisation

with nirsevimab during the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) 2024/25 season in the

neonatology unit at University

Hospital Zurich.

In summary, the overall immunisation rate

of all newborns discharged home from our centre was 78%. Four (0.01%) newborns

were passively immunised by maternal vaccination (Abrysvo®). A small percentage

of all immunisations (1.6% or n = 15) occurred in the outpatient setting.

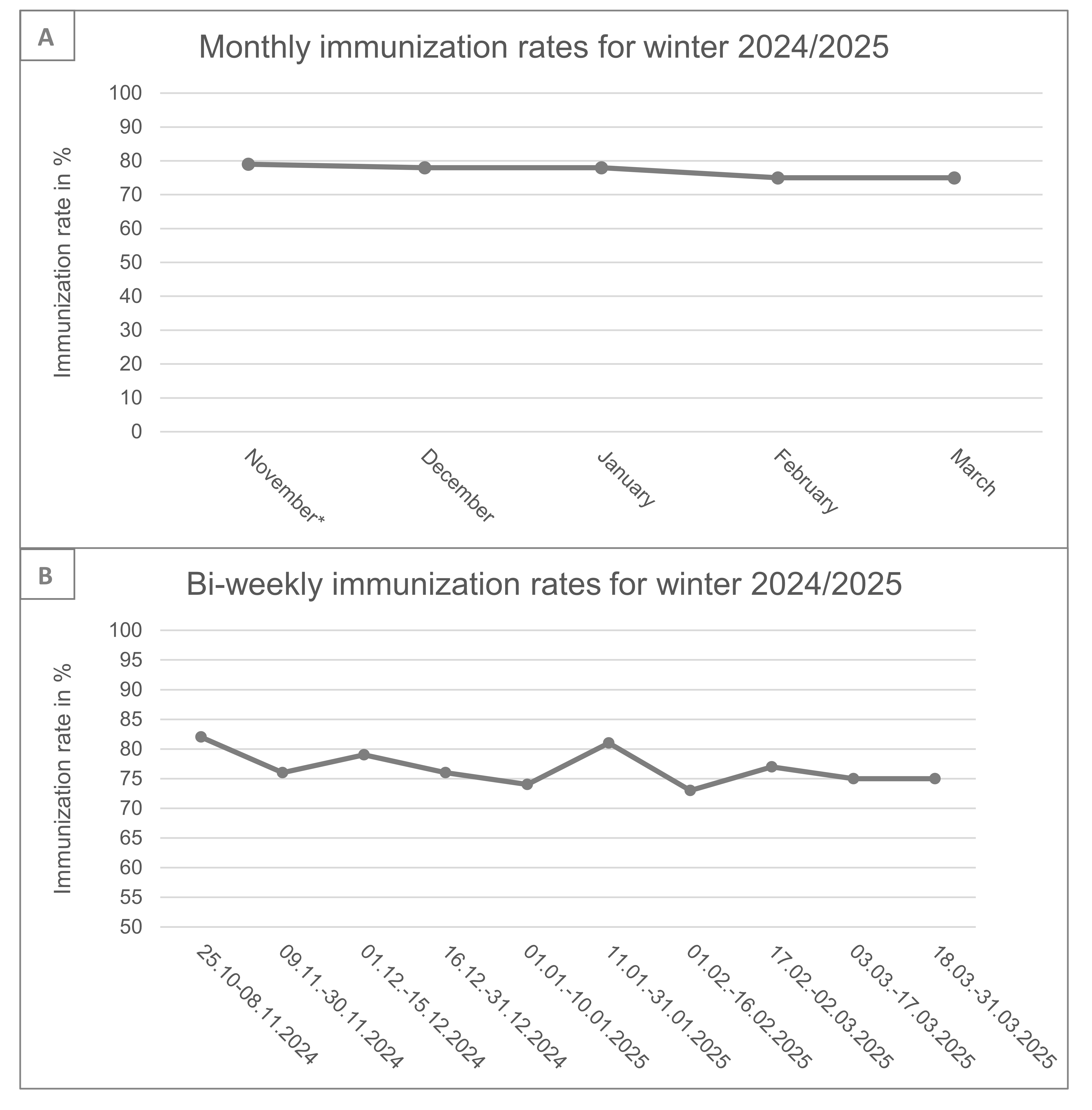

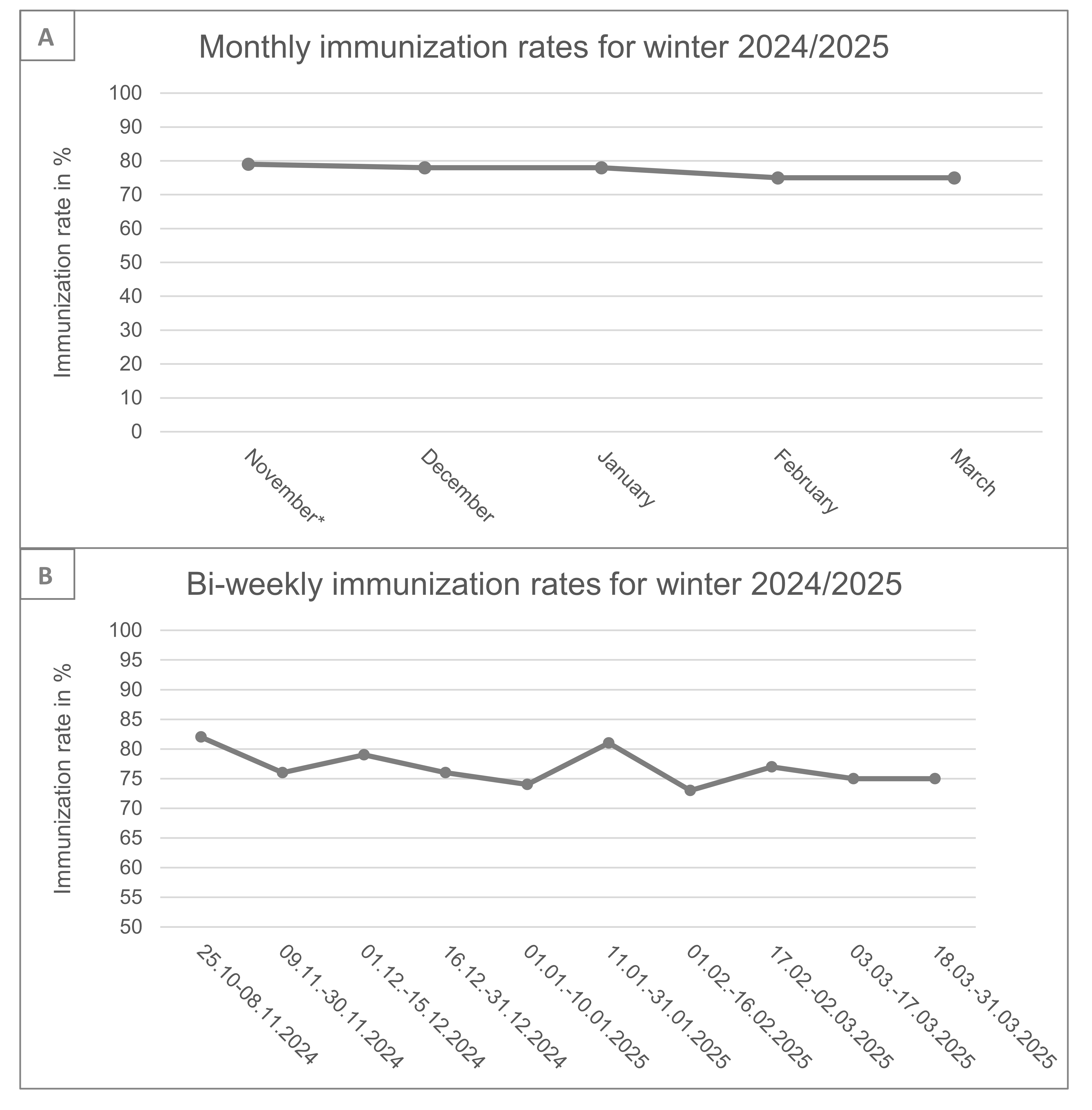

The monthly immunisation rates of the

neonates discharged from the maternity ward are shown in figure 4A. Immunisation

rates in the first weeks of implementation were 82%. The highest rates were

observed in October 2024 and January 2025 – 82% and 81%, respectively – and the

lowest in February 2025 with 73%.

Figure 4Monthly (A) and fortnightly (B) immunisation rates for RSV with nirsevimab or maternal

vaccination (Abrysvo®) in newborns discharged home from the maternity ward during

the 2024/25 winter season at University Hospital Zurich. * includes immunisations

from 28 to 31 October.

Discussion

This study reports on an interdisciplinary and interprofessional implementation strategy

for nirsevimab as well as on the immunisation coverage of newborns born during RSV

season 2024/25 at University Hospital Zurich. The immunisation rate was 78% for the

newborns discharged from the maternity ward and 82% for newborns leaving the neonatology

unit.

Immunisation strategies

The integration of nirsevimab into standard neonatal care represents a major advancement

in RSV infection prevention. Real-world data from the previous RSV season have shown

that it reduces severe RSV infections and related hospitalisations in infants, with

70–83% efficacy across several RCTs [6, 10, 11]. Unlike vaccines, passive immunisation

provides immediate protection, making it particularly valuable for newborns who are

at highest risk during their first months of life. Clearly this made the quick implementation

of nirsevimab essential; however several challenges were to be expected. First, the

particularly short time interval between regulatory approval and financial coverage

of nirsevimab in Switzerland and the start of the RSV season made implementation a

challenge for all disciplines providing care, whether inpatient or outpatient care.

Furthermore, when starting the programme for the newborns, the focus of the paediatricians

had to be the catch-up immunisation of all children born between April and September

2024, thus leaving little space for extra consultations of newborns. On the other

hand, maternity wards and neonatologists faced the challenge of an additional and

potentially time-consuming task, without reimbursement, other than the costs of nirsevimab

itself.

Previous experiences in Switzerland show that vaccine acceptance rates are rather

low in comparison to most neighbouring countries [12, 13]. Among 2-year-olds, full

coverage of the mandatory vaccines (such as measles and diphtheria, pertussis [whooping

cough] and tetanus [DPT]) in Switzerland was reported as under 90%, vs 93% in France

and 92% in Italy. Vaccine hesitancy has been reported to be influenced by a complex

interplay of emotional, cultural, religious, political, logistical and cognitive factors

[12, 14, 15]. While lack of knowledge and insufficient information have been consistently

linked to low vaccination rates, particularly in Switzerland, other elements such

as trust, personal stories and opportunities for dialogue with peers also play a crucial

role [13–16]. Although our study does not allow conclusions to be drawn on the above-mentioned

factors, these may still contribute to hesitancy in certain groups of our patients

and the 20% of parents who did not accept nirsevimab at our centre. Addressing vaccine

hesitancy therefore requires not only factual education but also empathetic and context-sensitive

communication strategies. A framework for open, non-judgemental discussion with vaccine-hesitant

parents from a trusted resource has been shown to positively influence vaccine acceptance

[13, 15].

Taken together, a good and quickly conceptualised strategy had to be brought up in

order to optimise the implementation of the passive immunisation against RSV for newborns.

The introduction of the multidisciplinary and interprofessional strategy at University

Hospital Zurich demonstrates how existing clinical routines can be adapted to incorporate

new preventive measures without significantly increasing workload for any discipline.

Immunisation rates in the first weeks of the programme, as high as 82%, show that

the concept was immediately effective. We believe that a key factor in the successful

implementation was the early and consistent communication with parents, which fostered

understanding and acceptance. Standardised information material endorsed by federal

authorities (Swiss Federal Office of Public Health / Federal Vaccination Commission)

ensured clarity and coherence across disciplines. Additionally, the interprofessional

approach including midwives and nurses might have raised acceptance by the parents.

Even though not specifically studied, subjectively the strategy was quickly incorporated

into routine standard care at our centre. By embedding the administration of nirsevimab

within routine workflows, such as postpartum assessments and discharge planning, the

protocol avoided additional strain on staff while maximising immunisation rates. This

approach may also serve as a model for introducing future innovations in neonatal

care.

RSV immunisation rates of newborns

Overall acceptance of nirsevimab at our centre was very high (80%). This rate is comparable

with the previously reported average overall vaccination rates of 70–90% from Galicia

(Spain), France, Luxembourg and the USA for the 2023/24 winter season [3–5, 17]. Most

likely, some children were additionally immunised at the paediatrician’s practice

at the 1-month follow-up.

The reasons for this high acceptance of the passive RSV immunisation of newborns are

speculative; however it seems likely that the perceived risk and heightened awareness

of contracting RSV can motivate parents to seek immunisation. Previous studies on

influenza vaccination found that the immediate risk of illness influenced individuals’

perception of vaccine efficacy and decision to vaccinate [18–20]. Seasonal interest

for other vaccines has been shown before. Krasselt et al. [14], for example, showed

significantly higher interest in the seasonal tick-born encephalitis vaccine during

the spring and summer months. Our results could be partly explained by these influences,

as we found particularly high immunisation rates at the beginning of the season and

during the peak of RSV in January. Hsieh et. al reported similar observations for

the maternal RSV vaccination in the current season [21]. Fewer observed RSV cases

in their environments might have led parents to decline immunisation in March. On

the other hand, it has been previously observed that health authorities often intensify

vaccination campaigns and public messaging during or leading up to peak disease seasons,

which affects vaccine uptake and reduces vaccination hesitancy [19, 22]. We cannot

rule out the possibility that our campaign was more rigorous at the beginning and

during the RSV peak season and that this led to reduced immunisation uptakes.

Strengths and limitations

This study presents an interdisciplinary and interprofessional approach for implementing

a new RSV immunisation strategy. Overall, high acceptance and immunisation of nirsevimab

was observed. However, the study design does not allow any conclusions to be drawn

on the acceptance of the implementation strategy itself; nor did the design compare

the strategy with other strategies. Furthermore, no direct correlation can be made

with the decreased incidence of severe RSV-related infections or hospitalisations.

Further studies, especially emphasising the individual and socioeconomic burden of

disease over the next two RSV seasons, are needed to respond to this question. Finally

yet importantly, this study does not allow any conclusions to be drawn as to why parents/families

accepted or declined immunisation of their newborn. Further research should specifically

address vaccine hesitancy and its underlying determinants such as language barriers,

parental education and health literacy, prior experiences with the healthcare system

and other relevant sociodemographic variables.

Conclusion

This is a pragmatic report on a feasible multidisciplinary and interprofessional implementation

strategy for neonatal RSV immunisation with nirsevimab that had an immediate high

immunisation rate. This study further presents an overall successful immunisation

rate of nearly 80% for all newborns discharged home from a tertiary centre in Switzerland

during the 2024/25 season.

Data sharing statement

All

data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article and

its supplementary material files. Further enquiries can be directed to the

corresponding author.

PD Dr

med. Ladina Vonzun

Department

of Obstetrics

University

Hospital Zurich

Frauenklinikstrasse 10

CH-8091 Zurich

ladina.vonzun[at]usz.ch

References

1. Mochizuki H, Kusuda S, Okada K, Yoshihara S, Furuya H, Simões EA, et al.; Scientific

Committee for Elucidation of Infantile Asthma. Palivizumab Prophylaxis in Preterm

Infants and Subsequent Recurrent Wheezing. Six-Year Follow-up Study. Am J Respir Crit

Care Med. 2017 Jul;196(1):29–38. doi: https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201609-1812OC

2. Simões EA, Madhi SA, Muller WJ, Atanasova V, Bosheva M, Cabañas F, et al. Efficacy

of nirsevimab against respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infections

in preterm and term infants, and pharmacokinetic extrapolation to infants with congenital

heart disease and chronic lung disease: a pooled analysis of randomised controlled

trials. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2023 Mar;7(3):180–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00321-2

3. Ernst C, Bejko D, Gaasch L, Hannelas E, Kahn I, Pierron C, et al. Impact of nirsevimab

prophylaxis on paediatric respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-related hospitalisations

during the initial 2023/24 season in Luxembourg. Euro Surveill. 2024 Jan;29(4):2400033.

doi: https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2024.29.4.2400033

4. Lassoued Y, Levy C, Werner A, Assad Z, Bechet S, Frandji B, et al. Effectiveness of

nirsevimab against RSV-bronchiolitis in paediatric ambulatory care: a test-negative

case-control study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2024 Jul;44:101007. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2024.101007

5. López-Lacort M, Muñoz-Quiles C, Mira-Iglesias A, López-Labrador FX, Mengual-Chuliá B,

Fernández-García C, et al. Early estimates of nirsevimab immunoprophylaxis effectiveness

against hospital admission for respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract

infections in infants, Spain, October 2023 to January 2024. Euro Surveill. 2024 Feb;29(6):2400046.

doi: https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2024.29.6.2400046

6. Hammitt LL, Dagan R, Yuan Y, Baca Cots M, Bosheva M, Madhi SA, et al.; MELODY Study

Group. Nirsevimab for Prevention of RSV in Healthy Late-Preterm and Term Infants.

N Engl J Med. 2022 Mar;386(9):837–46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2110275

7. Svizzera; P.S.P.S.P., et al., Consensus statement / recommendation on the prevention

of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infections with the monoclonal antibody Nirsevimab

(Beyfortus®) 2024: https://www.infovac.ch

8. Swiss DR. Klarstellung zur Vergütung von Nirsevimab (RSB-Immunisierung für Neugeborene).

2025 15.01.2025]; Available from: https://www.swissdrg.org/application/files/6917/3693/8899/Klarstellung_zur_Verguetung_von_Nirsevimab.pdf

9. Bundesamt für Gesundheit. S., Respiratorisches Synzytial-Virus. RSV; 2024.

10. Drysdale SB, Cathie K, Flamein F, Knuf M, Collins AM, Hill HC, et al.; HARMONIE Study

Group. Nirsevimab for Prevention of Hospitalizations Due to RSV in Infants. N Engl

J Med. 2023 Dec;389(26):2425–35. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2309189

11. Griffin MP, Yuan Y, Takas T, Domachowske JB, Madhi SA, Manzoni P, et al.; Nirsevimab

Study Group. Single-Dose Nirsevimab for Prevention of RSV in Preterm Infants. N Engl

J Med. 2020 Jul;383(5):415–25. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1913556

12. Zürcher SJ, Signorell A, Léchot-Huser A, Aebi C, Huber CA. Childhood vaccination coverage

and regional differences in Swiss birth cohorts 2012-2021: are we on track? Vaccine.

2023 Nov;41(48):7226–33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.10.043

13. Sabatini S, Kaufmann M, Fadda M, Tancredi S, Noor N, Van Der Linden BW, et al. Factors

Associated With COVID-19 Non-Vaccination in Switzerland: A Nationwide Study. Int J

Public Health. 2023 May;68:1605852. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2023.1605852

14. Krasselt J, Robin D, Fadda M, Geutjes A, Bubenhofer N, Suzanne Suggs L, et al. Tick-Talk:

parental online discourse about TBE vaccination. Vaccine. 2022 Dec;40(52):7538–46.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.10.055

15. Lafnitzegger A, Gaviria-Agudelo C. Vaccine Hesitancy in Pediatrics. Adv Pediatr. 2022 Aug;69(1):163–76.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yapd.2022.03.011

16. Wagner A, Juvalta S, Speranza C, Suggs LS, Drava J; COVIDisc study group. Let’s talk

about COVID-19 vaccination: relevance of conversations about COVID-19 vaccination

and information sources on vaccination intention in Switzerland. Vaccine. 2023 Aug;41(36):5313–21.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.07.004

17. Bundesamt für Gesundheit. S., Nirsevimab zur Immunisierung gegen das Respiratorische

Synzytial-Virus (RSV), in BAG-Bulletin, S. Bundesamt für Gesundheit, Editor. 2024.

p. 8-18.

18. Bhugra P, Grandhi GR, Mszar R, Satish P, Singh R, Blaha M, et al. Determinants of

Influenza Vaccine Uptake in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease and Strategies for

Improvement. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021 Aug;10(15):e019671. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.019671

19. Ng QX, Ng CX, Ong C, Lee DY, Liew TM. Examining Public Messaging on Influenza Vaccine

over Social Media: Unsupervised Deep Learning of 235,261 Twitter Posts from 2017 to

2023. Vaccines (Basel). 2023 Sep;11(10):1518. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11101518

20. Chao DL, Dimitrov DT. Seasonality and the effectiveness of mass vaccination. Math

Biosci Eng. 2016 Apr;13(2):249–59. doi: https://doi.org/10.3934/mbe.2015001

21. Jin Hsieh TY, Cheng-Chung Wei J, Collier AR. Investigation of Maternal Outcomes Following

Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccination in the Third Trimester: Insights from a Real-World

U.S. Electronic Health Records Database. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2025.

22. Kafadar AH, Sabatini S, Jones KA, Dening T. Categorising interventions to enhance

vaccine uptake or reduce vaccine hesitancy in the United Kingdom: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2024 Nov;42(25):126092. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2024.06.059