Molecular epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus in Switzerland 2019–2024 from

nucleic acid testing and whole-genome sequencing

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4600

Alexander Kuznetsovab*,

Rainer Gosertc*,

Ulrich Heiningerd,

Nina Khannae,

Sarah Tschudin-Suttere,

Richard A. Neherab,

Karoline Leuzingerc

a Biozentrum,

University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

b Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Basel,

Switzerland

c Clinical Virology, University Hospital

Basel, Basel, Switzerland

d Paediatric Infectious Diseases and

Hospital Epidemiology, University Children Hospital Basel, Basel, Switzerland

e Infectious Diseases and Hospital

Epidemiology, University Hospital Basel, Basel, Switzerland

* Equal

contribution as first authors

Summary

BACKGROUND

AND AIMS: Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection

is one of the leading causes of hospitalisation in infants, the elderly and

immunocompromised patients, with significant morbidity and mortality rates.

Despite its global impact, epidemiological surveillance of RSV in Switzerland

has historically been limited compared to the USA and European countries. A

significant surge in RSV activity and hospitalisations after the COVID-19

pandemic, along with the introduction of new monoclonal antibodies and RSV

vaccines, has led to an increased interest in the molecular epidemiology of

RSV. To ensure continued efficacy of the new preventive options, monitoring of

the genetic diversity of circulating RSV strains, their evolutionary dynamics

and the potential emergence of resistance mutations is of central importance.

The present study aimed to characterise the genetic diversity and seasonal

trends of RSV dynamics in Switzerland from 2019 to 2024, mainly over the last

two post-pandemic winter seasons (2022/23 and 2023/24).

METHODS: A total of 48,897 respiratory clinical specimens from 30,782 patients

with respiratory tract infections were tested for RSV at a tertiary care centre

in Northwestern Switzerland between July 2019 and June 2024. RSV activity over

these seasons was investigated. Amplicon-based whole-genome sequencing was

performed on 182 selected samples, with 125 high-quality consensus genomes and

phylogenies reconstructed. Lineage distribution and seasonal subtype prevalence

were compared to European data.

RESULTS: RSV activity was absent during the 2020/21 pandemic season, but

surged with an off-season peak in summer 2021. RSV B predominated during the

2022/23 season, while a shift to RSV A occurred in the 2023/24 winter season,

which is in line with neighbouring European countries. Lineage subtype

distribution showed high concordance with circulating European strains. RSV A

exhibited greater diversity (mean pairwise Hamming distance 0.015, SD 0.006)

than RSV B (mean 0.006, 0.003), with all current strains falling within G protein

duplication clades A.D.1, 2, 3 and 5 for RSV A, and B.D.E.1 and B.D.4.1.1 for

RSV B.

CONCLUSION: By contributing 125 newly assembled RSV genome sequences, we have significantly

increased the number of publicly available whole-genome sequences from

Switzerland. Our study provides a genomic surveillance of RSV in Switzerland,

analysing seasonal patterns, alternating subtype dominance, and consistency

with broader European trends. A comprehensive understanding of the molecular

epidemiology of RSV enables healthcare providers and public health authorities

to monitor the effectiveness of current vaccines and monoclonal antibodies,

associate lineages and serotypes with disease severity, implement timely

interventions and detect emerging variants, ultimately reducing the burden of

RSV-related illnesses.

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a

single-stranded RNA virus that causes respiratory tract infections. RSV

infection generally manifests with mild, cold-like symptoms but can cause

severe complications in high-risk groups such as infants, older adults and

immunocompromised patients [1].

Globally, RSV is the most common cause of lower respiratory tract infections in

infants [2].

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, RSV

activity in Switzerland followed a consistent seasonal pattern, typically

commencing in October, peaking in December or January and subsiding by April.

The number of hospitalisations exhibited a two-yearly regularity, where even-to-odd

winter seasons showed significantly more

hospitalisations than preceding ones [3]. However, from the first

implementation of social distancing measures in late February 2020 to the

post-pandemic winter seasons of 2022/23 and 2023/24, significant changes in RSV

epidemiology have been observed [4–6]. These changes include

shifts in the timing, intensity and age distribution of RSV infections,

reflecting the impact of public health measures and the subsequent relaxation

of non-pharmaceutical interventions. While some have hypothesised that these

shifts may be due to increased virulence of circulating RSV strains during the

pandemic [7],

current molecular epidemiological surveillance shows that post-pandemic

circulation is dominated by several lineages with pre-pandemic roots,

suggesting epidemiological rather than virological reasons [8].

With the recent introduction of monoclonal

antibodies and prefusion F protein-based vaccines (RSVpreF) in 2023/24, such as

nirsevimab (Beyfortus®) [9, 10]

by AstraZeneca and Sanofi, Abrysvo® by Pfizer [11] and Arexvy® by

GlaxoSmithKline [12],

options for specific prevention of RSV infections have increased dramatically.

These interventions raise important concerns about the molecular adaptation of

RSV under selective pressure, possibly leading to variants that escape

vaccine-induced immunity or develop resistance to monoclonal antibodies. The

main focus of attention lies on the Fusion (F) protein, the primary antigen in

current recombinant vaccines and a target for monoclonal antibodies [13]. Several

studies so

far have shown little to no elevated levels of polymorphisms in the vaccinees

compared to the control group [14]. However, RSV is a

rapidly evolving virus with a high mutation rate, and continuous monitoring is

crucial to detect potential early signals of adaptation and escape variants

that may arise as vaccines and monoclonal antibodies are rolled out more

widely. A comprehensive understanding of the molecular epidemiology of RSV

enables healthcare providers and public health authorities to monitor the

effectiveness of current vaccines and monoclonal antibodies, assess the

severity of RSV-related diseases, implement timely interventions and detect

emerging variants, ultimately reducing the burden of RSV-related illnesses.

RSV is divided into two major antigenic

subtypes, RSV A and RSV B, with the greatest divergence in the gene coding for

the attachment glycoprotein G (G protein). The estimated common ancestor of the

RSV A and RSV B circulated around 250 years ago [15]. A recent

hierarchical classification by Goya et al. [16] defined 24 and 16

lineages within RSV A and RSV B, respectively, based on phylogeny and amino

acid markers. This novel unified nomenclature is designed to be kept up-to-date

through designation of new lineages with the aim of tracking epidemiologically

relevant viral variants and comparing the circulation of the virus from season

to season and across geographies.

In this study, we present data on RSV

dynamics in Northwestern Switzerland during the pre-pandemic season 2019/20,

the pandemic seasons 2020/21 and 2021/22, and the post-pandemic periods 2022/23

and 2023/24. Throughout this timeframe, we conducted nucleic acid testing and

full-genome sequencing of RSV from symptomatic patients presenting with respiratory

tract infections at our tertiary care hospital.

Methods

Patient cohorts and inclusion criteria

Patients included in our study presented

with acute respiratory tract infections, as defined by at least 1 respiratory

and 1 systemic symptom/sign such as clogged or runny nasal airways, sore

throat, cough, fatigue, fever, headache, chills or myalgia [17]. This clinical

diagnosis is a prerequisite for ordering broad molecular multiplex panel

testing at our tertiary care hospital. The patients presented to the outpatient

or emergency departments of University Hospital Basel or University Children’s

Hospital Basel between July 2019 and June 2024 and underwent RSV-specific

nucleic acid testing. RSV-specific testing was performed using the Biofire FilmArray

RPP (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) and additionally the Xpert®

Xpress-CoV-2/Flu/RSV-Plus system (Cepheid, CA, USA) [18, 19]. The sensitivity

of the Biofire FilmArray RPP for detecting RSV ranges from 95% to 100%, while

specificity exceeds 99%. The corresponding values for the Xpert®

Xpress-CoV-2/Flu/RSV-Plus system are 95–98% sensitivity and >98% specificity [20,

21].

Amplicon-based next-generation sequencing approach

The 500bp-NAT (nucleic acid testing) primers

were designed to match conserved sequences across all publicly available

full-length RSV genome sequences from the NCBI nucleotide database (totalling 3010

as of 1 January 2022, with 2002 RSV A and 1008 RSV B). NAT primers were

designed using the publicly available PRIMAL tool [22] that allows the

design of highly multiplex primer pools. Additionally, 2000bp-NAT primers and

1000bp-RSV A and RSV B subgroup-specific NAT primers were employed from [23], and

used in 2

separate primer pools. All NATs used the Iproof High Fidelity DNA Polymerase kit

(BioRad, CA, USA) with 600 nM end concentration of the different primer pools (appendix

figure S4, supplementary

files 1 and 2). NATs had a reaction volume of 25 µl containing

5 µl of extracted DNA and were run on Veriti™ Thermal Cyclers (Applied

Biosystems, MA, USA) using the thermal cycling protocol specified in the Iproof

High Fidelity DNA Polymerase kit. Library preparation was done by pooling the

six amplicons from the 2000bp, 1000bp and 500bp NAT reactions using the KAPA

HyperPrep Kit (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) following the manufacturers’

instructions. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed on a MiniSeq

platform (Illumina, CA, USA). Raw data, including FASTQ files, were

subsequently processed and organised for downstream analysis.

Genome assembly

Raw sequencing reads were trimmed using

Trim Galore v0.6.10 and mapped to reference genomes with BWA-MEM v0.7.18.

Pileup analysis and consensus sequence construction were performed using custom

scripts adapted from the Enterovirus D68 project [24, 25].

Preprocessing and sample selection

A total of 182 samples were initially

selected for the analysis: 159 from outpatients and 23 from hospitalised

patients with the best coverage (appendix figure S3). Preprocessing included masking

positions with

less than 90% main allele frequency. After applying a coverage threshold of at

least 100× over 80% of the genome, 125 samples (96 RSV A, 29 RSV B) were

retained for the phylogenetic analysis.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic trees were constructed using

the Nextstrain [26]

CLI pipeline v8.5.3, which includes Augur v26.0.0 and Auspice v2.58.0.

Consensus sequences were aligned with background data from the NCBI Virus

database using Nextclade [27]

v3.8.2, and trees were inferred using IQ-TREE [28] v2.3.6. Two trees

were generated: one with no regional or temporal filters for global context and

another focused on recent (last 3 years) European sequences for more detailed

comparison. Diversity was calculated as follows: for each RSV subtype, aligned

consensus sequences were taken; Hamming distance (the number of positions with

different nucleotides for two aligned genomes) for each pair was calculated,

excluding uncertain consensus positions and normalising to the length of the

compared part. All the tools mentioned above are publicly available under

GPL-3.0 or MIT licences.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted according to good

laboratory practice and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and

national and institutional standards, and was approved by the ethics committee

of Northwestern and Central Switzerland (EKNZ 2024-00813).

Results

Pre- and post-pandemic seasonal dynamics of RSV

Patients presenting with symptoms of respiratory

tract infections at the outpatient or emergency departments of University

Hospital Basel or University Children’s Hospital Basel underwent RSV-specific

nucleic acid testing between July 2019 and June 2024 (appendix table S2). RSV-positive

samples with

sufficient residual material further underwent full-genome sequencing,

representing a convenience sample over the whole study period.

A total of 48,897 respiratory clinical

specimens from 30,782 patients with respiratory tract infections – of whom 14,613

(47.5%) were female and 6436 (20.9%) paediatric patients <18 years – were

submitted for routine RSV-specific nucleic acid testing between July 2019 and

June 2024 at our tertiary care hospital in Northwestern Switzerland (table 1, appendix

table S1). The median patient age was 62 years (range: 1 to 106

years).

Table 1Distribution of tested and sequenced samples.

| Demographic |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

Total |

| <18 |

≥18 |

<18 |

≥18 |

<18 |

≥18 |

<18 |

≥18 |

<18 |

≥18 |

<18 |

≥18 |

<18 |

≥18 |

| RSV-positive samples (n) |

43 |

21 |

28 |

43 |

310 |

55 |

481 |

310 |

231 |

123 |

131 |

118 |

1224 |

670 |

| RSV-positive patients (n) |

43 |

21 |

18 |

30 |

252 |

55 |

433 |

248 |

214 |

98 |

117 |

99 |

1077 |

551 |

| RSV sequences (n) |

|

|

|

2 |

|

7 |

|

23 |

69 |

41 |

16 |

24 |

85 |

97 |

| RSV sequences, passed QC (n) |

|

|

|

1 |

|

3 |

|

13 |

56 |

30 |

6 |

16 |

62 |

63 |

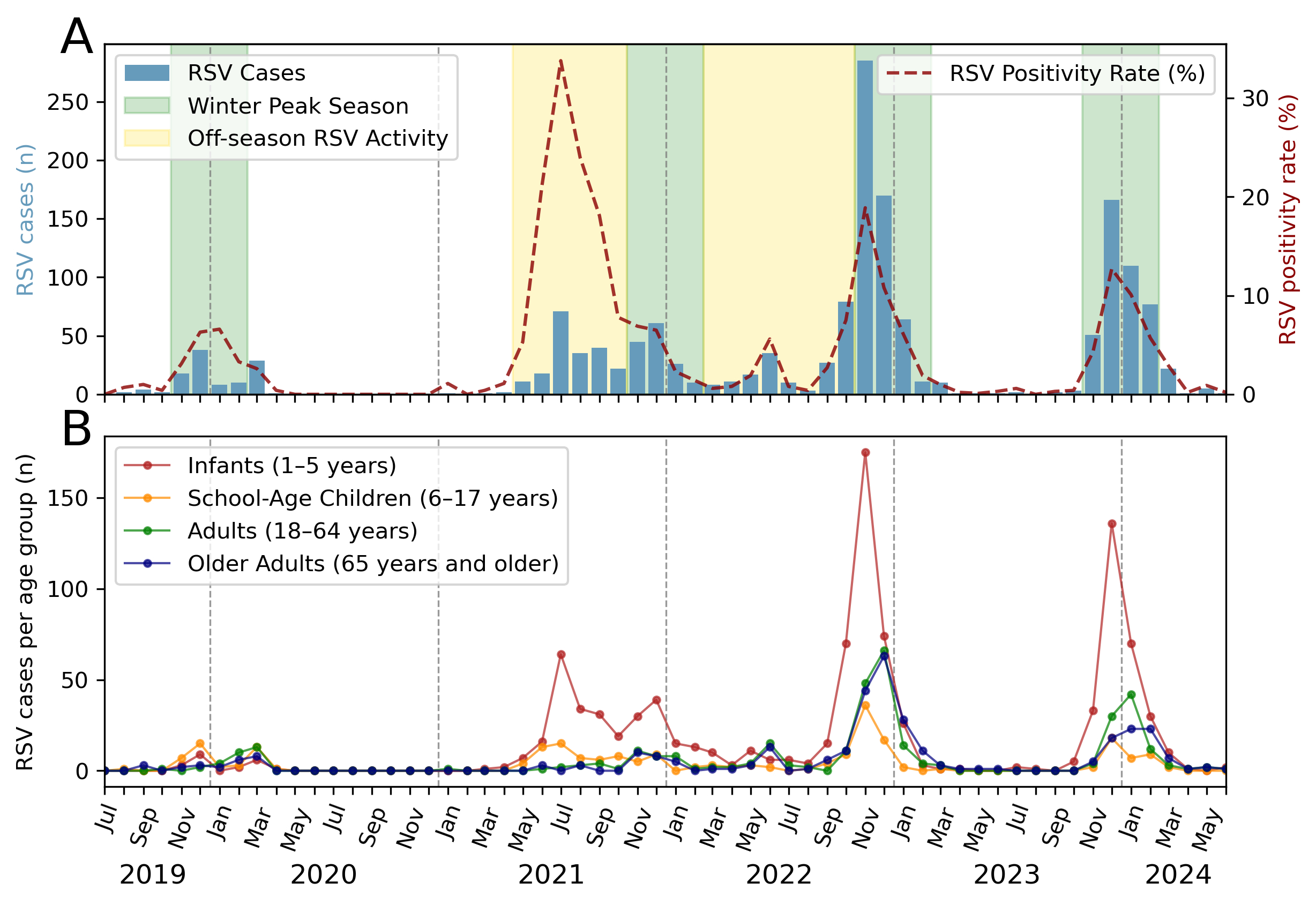

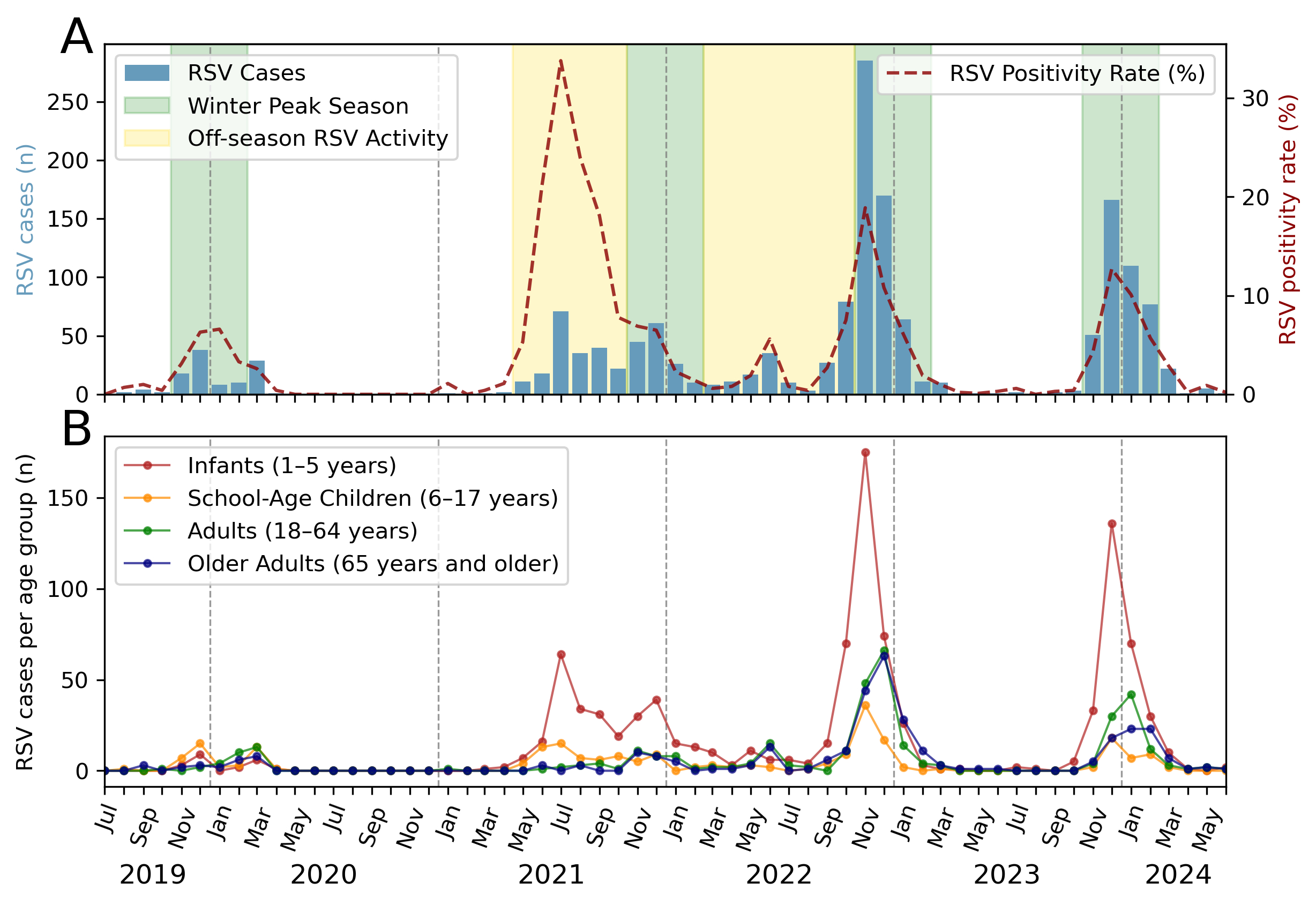

First, we assessed the seasonality and peak

activity of RSV during the study period. In 2019, prior to the COVID-19

pandemic, the number of RSV infections in our catchment area increased in

October and subsided by February 2020, consistent with seasonal patterns

observed before the pandemic [3]. The implementation of non-pharmaceutical

interventions to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in 2020 and 2021, including

travel restrictions, social distancing, mask mandates, and school and business

closures, disrupted this regularity. Notably, during the 2020/21 season, RSV

activity was minimal, with no significant epidemic observed. However, an

atypical early surge occurred in 2021. Cases began to rise in May, peaking in

July, and persisting until January 2022. Subsequent post-pandemic 2022/23 and

2023/24 seasons indicated a return to pre-pandemic seasonality, with activity

commencing in late summer, peaking in November and declining by January (figure

1A).

Figure 1Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) seasonality, peak activity and

demographic distribution. (A) RSV detections during the pandemic seasons

(2019/20, 2020/21, 2021/22) and the post-pandemic period (2022/23, 2023/24).

The green background bar represents the typical RSV winter season, running from

November to February, and the yellow background bar indicates off-season RSV

activity. The number of positive cases per month is indicated by blue bars and

the positive rate is shown as a dashed red line (right axis). (B) Age

distribution of RSV cases by month for the specified period.

The off-season activity in 2021

significantly impacted paediatric patients aged 1 to 5 years, who accounted for

most RSV cases during that period. In subsequent seasons, we observed an

increase in diagnosed RSV infections among adults and older patients aged ≥65

years (figure 1B). In the 2022/23 RSV season, RSV infections in infants and

school-aged children peaked 1–2 months earlier than those in adults, which

suggests that younger populations may have had higher susceptibility in the

first post-pandemic season.

During the 2022/23 and 2023/24 seasons,

adult populations experienced consecutive major RSV epidemics, leading to

significantly increased RSV-related hospitalisations compared to the pandemic

2019/20 and 2020/21 seasons (appendix figure S1). The elevated case numbers in post-pandemic

seasons relative to pre-pandemic seasons can be attributed, in part, to

increased testing rates, as test positivity does not differ as dramatically

between pre- and post-pandemic seasons. Hospitalisation rates for paediatric

patients were not available for this study, but recent data suggest that

immunologically naive children or those with limited prior exposure to RSV

during the COVID-19 pandemic experienced more severe RSV-related illness and faced

a higher risk of hospitalisation compared to pre-pandemic years [5, 29, 30].

Seasonal distribution of RSV subtypes

Respiratory viruses generally show a

similar distribution of genotypes in geographically well-connected regions, but

during the pandemic period with travel restrictions and variable approaches to

social distancing and non-pharmaceutical interventions, resolving the local

diversity of viruses is of particular interest. Furthermore, addressing the

hypotheses that circulating RSV strains after the pandemic may have exhibited

increased virulence (appendix table S3),

potentially contributing to higher transmission rates, increased case numbers

and related hospitalisations, requires whole-genome sequencing of a

sufficiently large number of viral samples to detect or rule out strong

associations between viral genotypes and presentation.

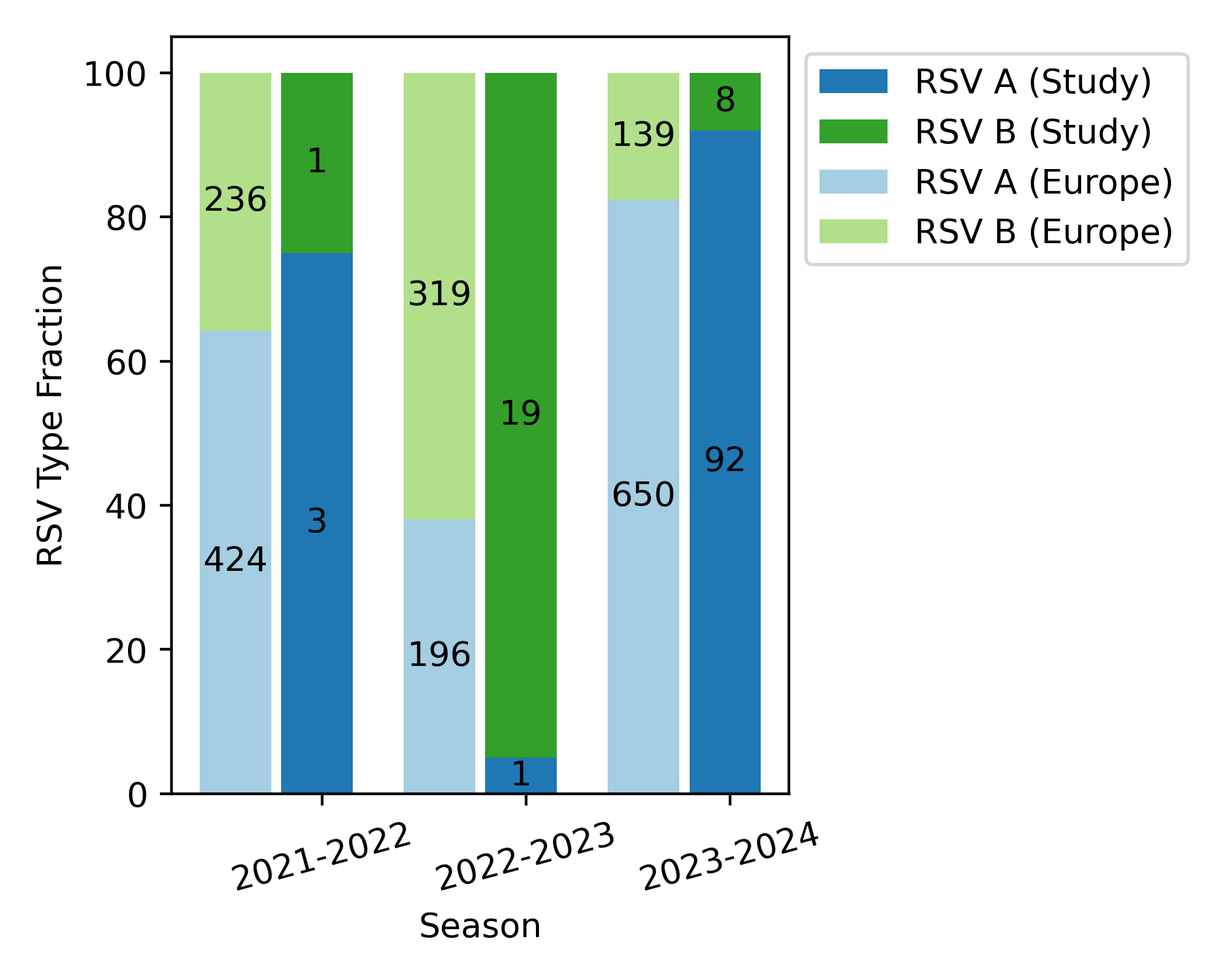

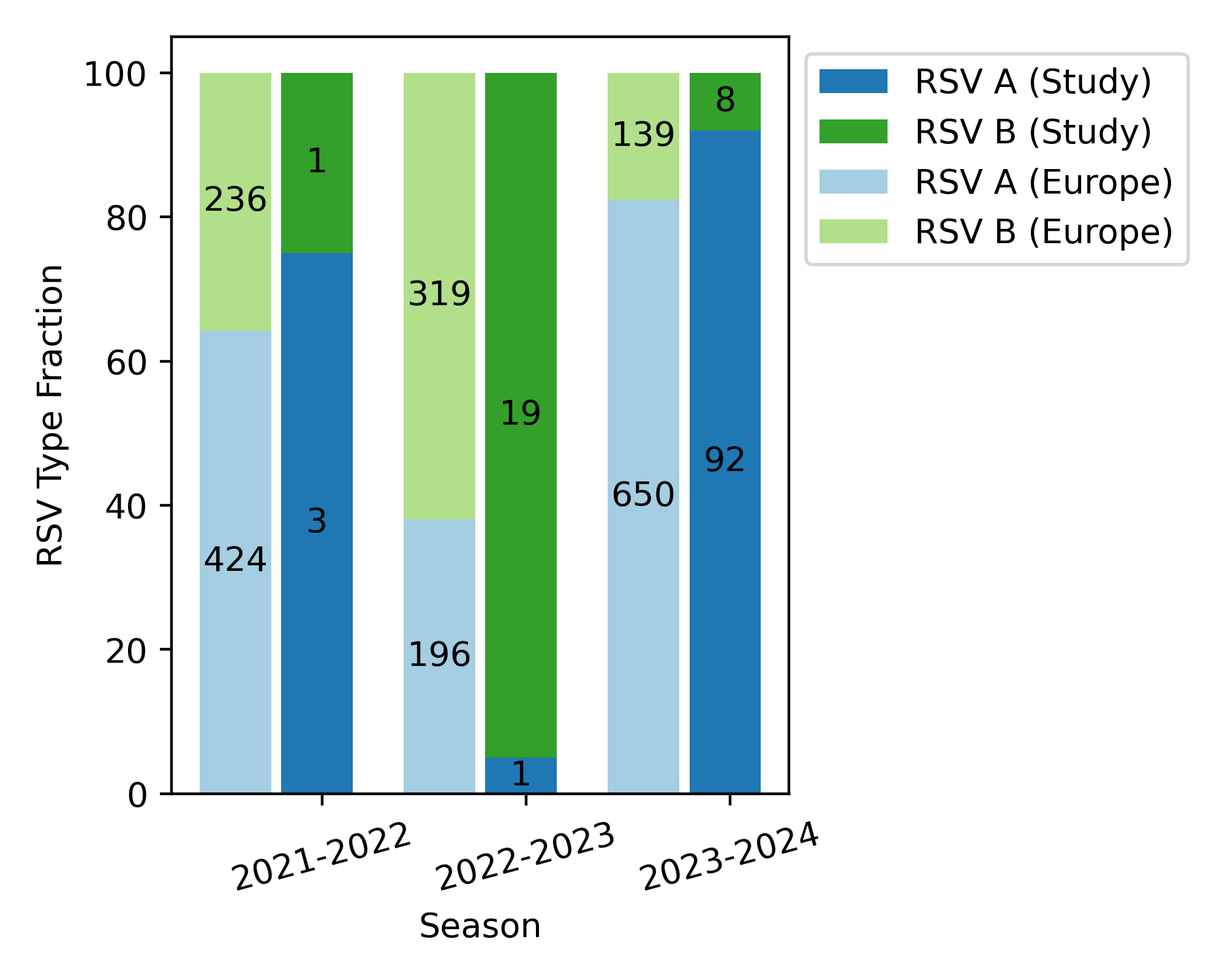

While only a few samples were available for

whole-genome sequencing prior to 2022, we generated 20 full genomes from the

2022/23 season and 100 for the 2023/24 season. As shown in figure 2, RSV B dominated

during the 2022/23 season (19 of 20

samples), while RSV A was the main subtype in the 2023/24 season (92 of 100

samples).

Figure 2Annual distribution of RSV A and RSV B subtypes in Switzerland and Europe

over the 2021/22, 2022/23 and 2023/24 seasons. Numbers inside the bars

display actual numbers of respiratory

syncytial virus (RSV) subtype cases, while heights correspond to

fractions. Stacked bars to the left show same-season RSV subtype distributions

in European samples available in the NCBI virus database.

Phylogenetic analysis of RSV subtypes

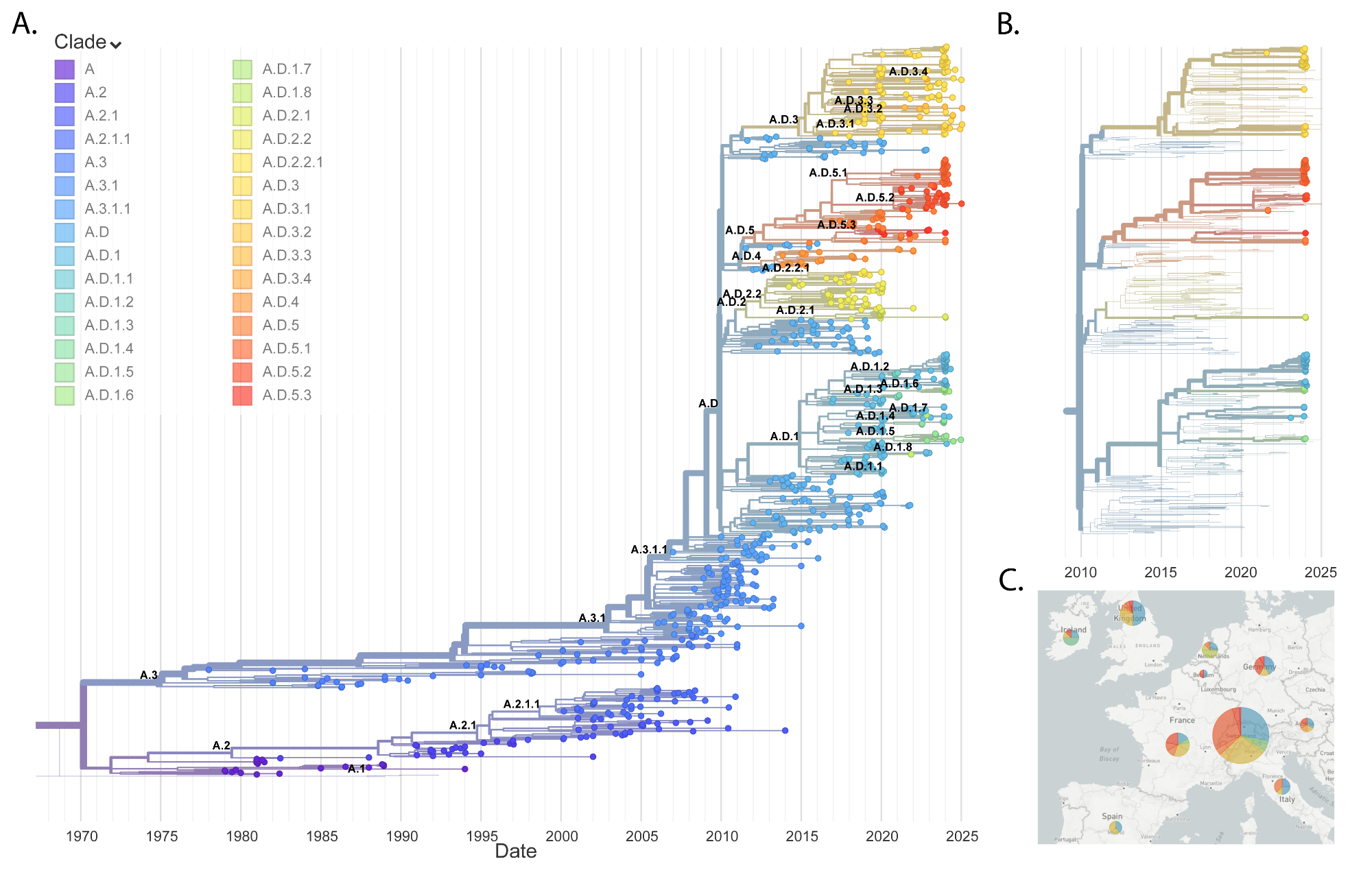

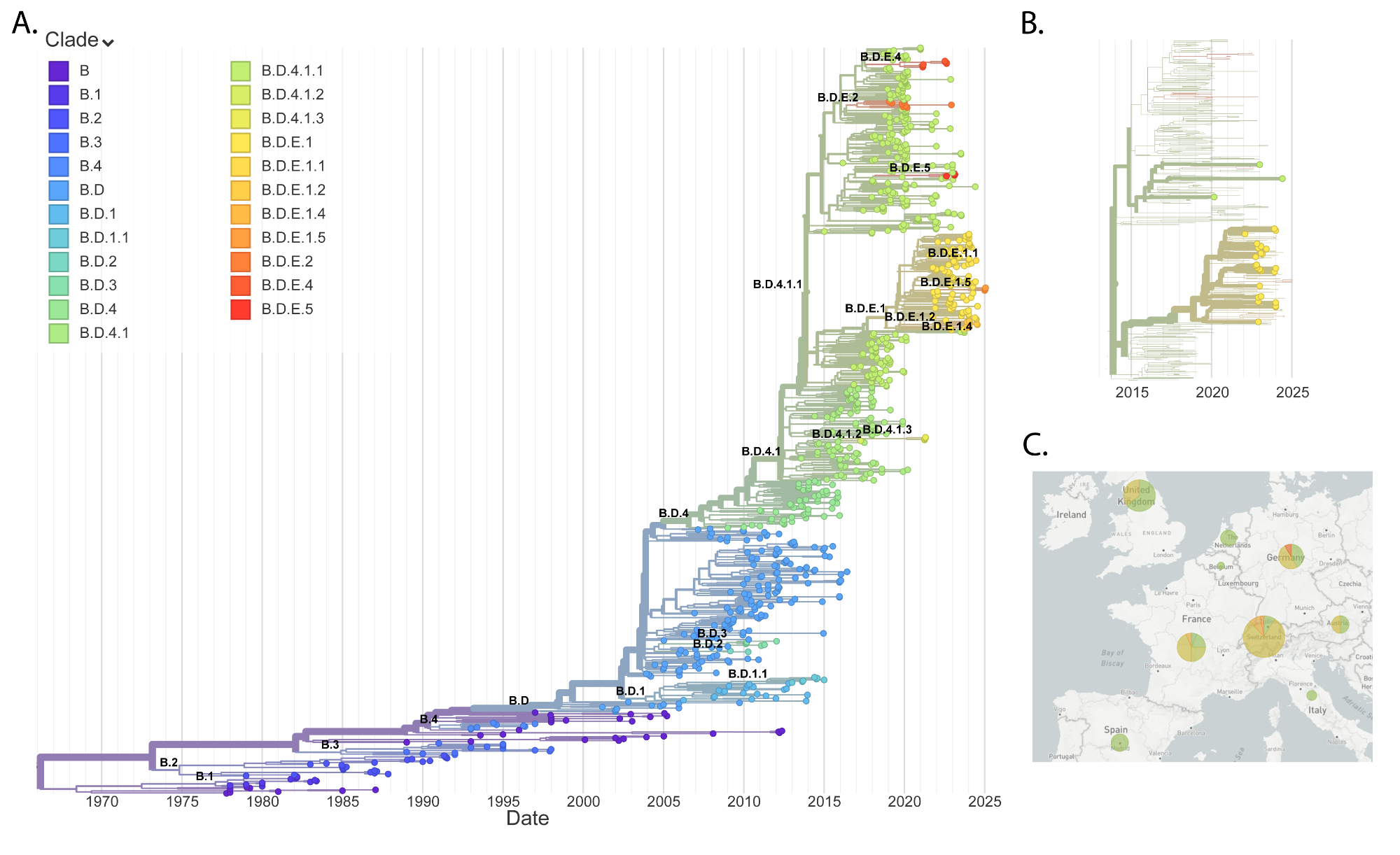

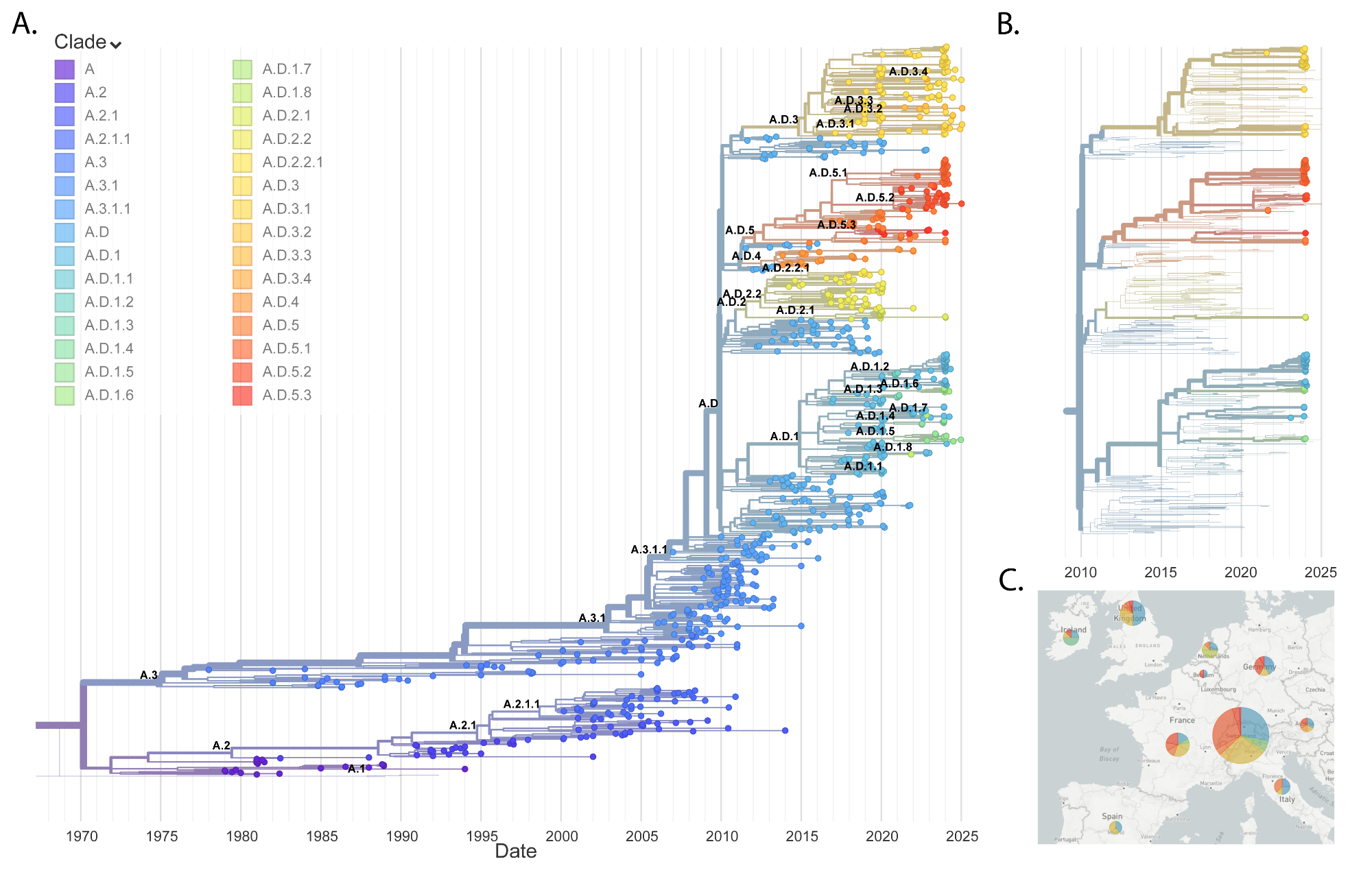

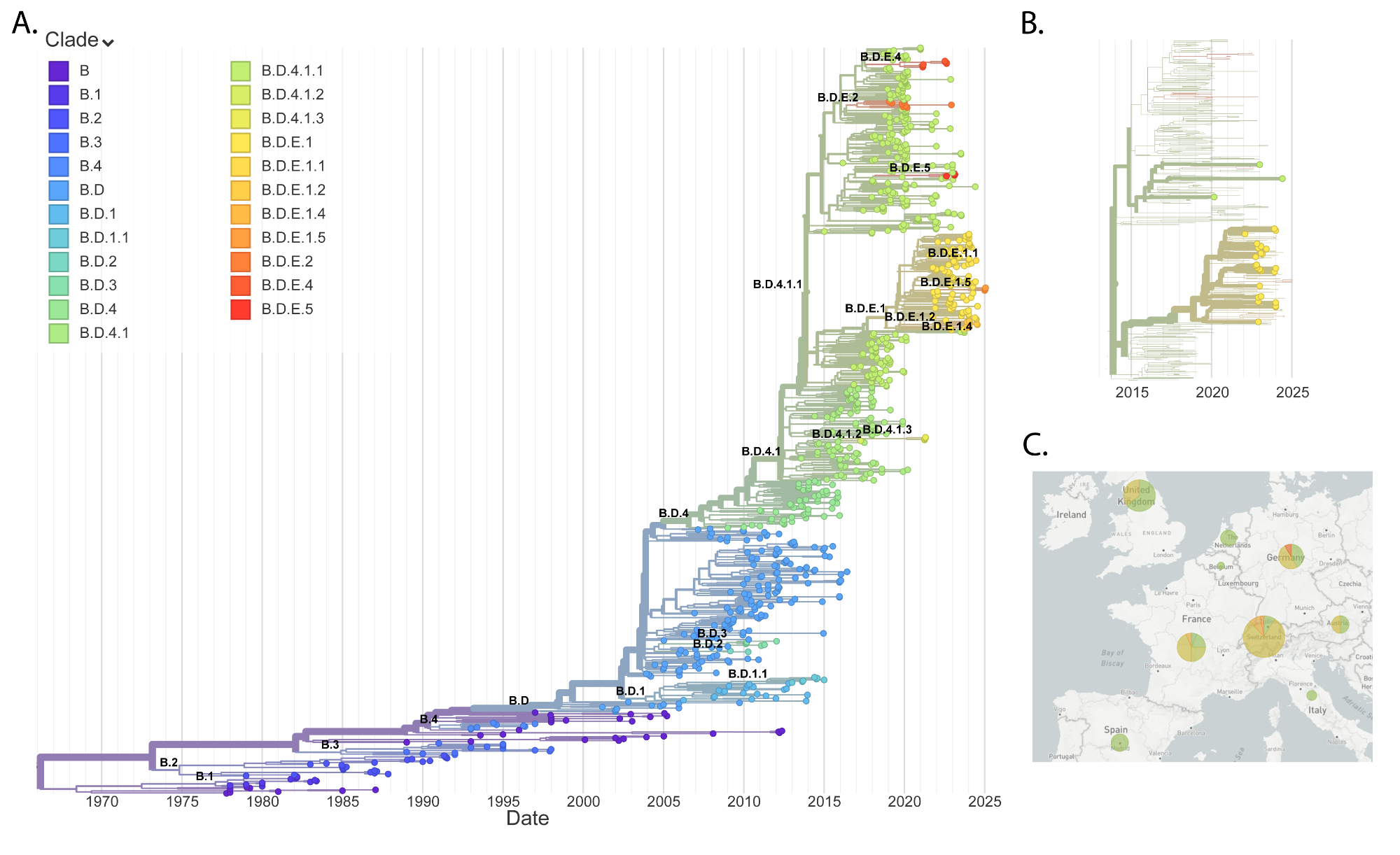

All currently circulating RSV strains

belong to clades with duplications in the G protein (figures 3A and 4A), which

occurred independently in RSV A and RSV B [31, 32] in 2009 and 1996,

respectively, according to the reconstructed phylogenies. These clades are

named A.D and B.D in the new lineage nomenclature [16] and have been

divided into several sublineages.

Figure 3RSV A phylogeny. (A) Global

phylogenetic tree of RSV A sequences. (B) RSV A phylogenetic tree focusing on

the last two years of European data. Bold leaves indicate sequences generated

in this study. (C) Geographic distribution of RSV A clades in Europe over the

last two seasons.

RSV A: Switzerland vs Europe

Phylogenetic analysis of RSV A sequences

revealed a high degree of correspondence between Switzerland and the broader

European context (figures 3B–C). Sequence diversity levels are higher for RSV

A, with mean pairwise Hamming distance of 0.015 and SD 0.006, compared to the

mean of 0.006 and SD 0.003 for RSV B (appendix figure S2). RSV A samples were

found in three main lineages – A.D.1, A.D.3 and A.D.5 – and, to a lesser extent,

in A.D.2. These lineages have been observed across Europe and have a common ancestor

prior to 2015. Therefore, multiple lineages of RSV A have persisted from the

pre-pandemic period and there is no indication that a particular lineage with

distinct properties has emerged that might be associated with a different

presentation. Overall, this diverse RSV A population with high correspondence

to European dynamics suggests that RSV A was introduced into Switzerland

numerous times each season and that there is frequent exchange with neighbouring

countries.

RSV B: Switzerland vs Europe

The RSV B phylogeny also showed high

correspondence with other European countries. Current circulating strains of

RSV B mostly fall within B.D.E.1 and B.D.4.1.1 clades, which is also the case

for our data (figures 4B-C, appendix table S4): 26 samples belong to B.D.E.1 and 3

samples to its

parent clade, B.D.4.1.1. The lineage B.D.E.1 emerged shortly before the

pandemic and has expanded globally over the past 5 years. This recent expansion

explains the lower Hamming distance levels compared to RSV A and the different

clade distribution. Apart from these differences between subtypes, RSV B

samples also display multiple introduction events with many lineages persisting

across many seasons.

Figure 4RSV B phylogeny. (A) Global

phylogenetic tree of RSV B sequences. (B) RSV B phylogenetic tree focusing on

the last two years of European data. Bold leaves indicate sequences generated

in this study. (C) Geographic distribution of RSV B clades in Europe during the

last two seasons.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly

disrupted the typical seasonal patterns of RSV transmission and activity [33]. Public

health

measures implemented to curb the spread of SARS-CoV-2, such as social

distancing, mask-wearing and lockdowns, led to a temporary decline in RSV cases [34].

Here, we reported

on the patterns of RSV infections and hospitalisations during this period in

Northwestern Switzerland. As these measures were relaxed, a notable resurgence

of RSV activity was observed. For example, an unusual outbreak occurred in the

summer of 2021, deviating from the typical winter peak. This was followed by a

strong resurgence of RSV cases and related hospitalisations in the following

2022/23 and 2023/24 seasons after all COVID-19 restrictions were lifted. The

observed patterns of RSV infections generally mirror those observed elsewhere

in Switzerland [5, 6],

but are notably different from those of the neighbouring countries Germany [35–37],

Italy [38–40] and Austria [41], where no summer

wave was observed in 2021. The USA, on the other hand, did observe significant

RSV activity between April 2021 and February 2022 [42]. Considering the

varied resurgence patterns of RSV across Europe, one might anticipate that the

dominant viral type (RSV A vs B) differs between countries, or that different

sublineages of RSV A or B circulated in different regions. To investigate this

hypothesis, we performed whole-genome sequencing on respiratory swabs,

generating a total of 125 RSV genomes. Overall, the dominance patterns of RSV A

and B were consistent with those of neighbouring countries. However, Europe as

a whole demonstrated a moderately more even distribution of both viral types,

which might be due to the much larger and diverse demographic.

Aggregated data from Europe for these two

seasons reveal the presence of the same predominant subtypes. However, the

dominance is less pronounced: RSV B accounted for 62% of the samples in the

2022/23 season (319 of 515) while RSV A comprised 82% of the samples in the

2023/24 season (650 of 789). Data from the neighbouring countries Austria and

Germany indicate a similarly pronounced alternation in subtype dominance,

exhibiting a 90% difference between these seasons [37, 41], akin to the

trends observed in Switzerland. An analysis of wastewater samples in

Switzerland found the same subtype distribution for post-pandemic seasons [43]. In

contrast, the

USA exhibits the opposite pattern in seasonal subtype dynamics: RSV B was

predominant in the 2021/22 and 2023/24 seasons, while RSV A prevailed during

the 2022/23 season [42, 44].

This disparity underscores the necessity for global surveillance of RSV.

Concordance was similarly observed at the

lineage level. For RSV A, these sequenced strains reflect lineages that were

prevalent in Europe during the same period. Most of these lineages have been

circulating in parallel since 2010, predating the pandemic, which implies that

no specific lineage was responsible for the resurgence of cases. Instead,

observed differences in disease presentation and incidence are likely

attributable to epidemiological or immunological factors arising from non-pharmaceutical

interventions and reduced exposure to viral pathogens during periods of social

distancing. Conversely, since the pandemic’s onset, RSV B diversity has

primarily been driven by lineage B.D.E.1 and its descendants, which likely

arose more recently in 2019 [45].

Consequently, RSV B sequences exhibit

greater similarity to one another compared to RSV A sequences. Notably, the

diversity that we observed in Northwestern Switzerland aligns closely with the

circulating strains in neighbouring European countries.

These findings indicate a sufficiently

rapid exchange of RSV among European countries, facilitating alignment of the

circulation patterns, even amid restricted travel and movement. However, on a

broader geographic scale, these patterns exhibit notable differences. For

instance, in the United States, different dominance patterns have been observed

for RSV A and B, reflecting a divergence in the epidemiological behaviour of

the virus compared to Europe [42].

Monitoring the circulating strains of RSV

is crucial, as RSV subtypes A and B co-circulate globally, with shifts in

predominance observed over time. Research has demonstrated that these subtypes

may present different clinical manifestations and disease outcomes. In paediatric

populations, it has been shown that RSV A infections tend to result in more

severe clinical presentations and poorer patient outcomes compared to RSV B [46–48].

Although fewer

studies have focused on adult populations, existing evidence suggests that RSV

A is associated with increased virulence, as indicated by clinical severity

scores [49].

These findings align with our observations, as the RSV A-dominant 2023/24

season coincided with an increase in hospitalisation rates, although causality

cannot be established within the scope of our study. As discussed above, the

genetic diversity of RSV A observed during the post-pandemic resurgence does

not imply that lineages that persisted through the pandemic possessed unique

characteristics.

This highlights the importance of

accurately identifying circulating RSV strains. Understanding which strains are

prevalent allows healthcare providers and public health authorities to better

anticipate potential increases in transmission rates, case numbers and disease

severity, facilitating more effective allocation of healthcare resources and

implementation of targeted interventions.

With the introduction of RSV vaccines for

adults in Switzerland, such as Arexvy and Abryso, alongside monoclonal

antibodies for children, including Beyfortus, monitoring the molecular

epidemiology of RSV and tracking escape or resistance mutations is becoming

increasingly important. While little resistance has been observed in clinical

studies to date, the widespread deployment of these preventive measures may

exert additional pressure on the virus to evolve [50]. Early

identification of such strains is essential for adapting diagnostic tools,

refining prevention strategies and enhancing vaccine strategies to maintain their

effectiveness against RSV infections.

This study has several limitations that

should be acknowledged. The limited catchment area restricts the generalisability

of the findings to broader populations, potentially overlooking regional

variations in RSV circulation. The use of convenience sampling for full genome

analysis may introduce selection bias, as samples are not randomly chosen and

may not accurately represent the entire circulating viral diversity. Additionally,

the coverage bias inherent in next-generation sequencing (NGS) results, which

excludes low-coverage samples from analysis, could influence the observed

lineage distribution by underrepresenting certain variants that are present at

lower abundance. Relying solely on consensus sequences further limits the

detection of intra-host viral diversity and minority variants, potentially

overlooking minor lineages or mutations that could impact viral evolution and

epidemiology. Lastly, detailed clinical information, including patient

outcomes, precise anatomical location of infection (upper and lower respiratory

tract infections) and disease severity, was not available in the scope of this

study. Therefore correlations between viral genotypes and these factors could

not be assessed, limiting epidemiological conclusions to subtype occurrence

analysis only. These methodological constraints may collectively influence the

study’s conclusions regarding RSV lineage dynamics and mask the full spectrum

of viral diversity within the studied population.

In summary, our analysis of RSV

epidemiology of recent seasons in Switzerland outlines the dynamics of case

numbers and subtype prevalence and highlights the importance of sustained

surveillance. Ongoing monitoring is critical to inform public health policies,

guide vaccination strategies and detect the emergence of variants with

potential clinical and epidemiological significance.

Data sharing statement

The consensus genomes generated in this

study have been submitted to the Pathoplexus database under sequence sets

PP_SS_201.2 [51] and PP_SS_202.2 [52] and to NCBI Datasets Virus Data under

Bioprojects PRJEB88486 and PRJEB88624, respectively.

Code availability: The custom algorithms

and scripts developed for this study are openly accessible and can be found in

our GitHub repository at: https://github.com/neherlab/rsv_epidemiology_2025

We encourage researchers and practitioners

to explore and use this resource for further advancements in the field.

Acknowledgments

We thank the biomedical technicians of the

Clinical Virology Department, Laboratory Medicine, University Hospital Basel,

Basel, Switzerland, for expert help and assistance. We also thank Anna Parker

for her support with data submission to the Pathoplexus genomic database.

Author contributions: RG, RAN and KL

contributed to the conceptualisation and study design. Data collection and

clinical contributions were provided by UH, NK and STS. Methodology and

laboratory analyses were conducted by RG and KL. Data analysis and

interpretation were performed by AK, RG, RAN and KL. The original draft of the

manuscript was written by AK and RAN. All authors reviewed and approved the

final manuscript.

PD Dr Karoline Leuzinger

Clinical Virology

University Hospital Basel

Petersgraben 4

CH-4031 Basel

karoline.leuzinger[at]usb.ch

References

1. Kaler J, Hussain A, Patel K, Hernandez T, Ray S. Respiratory syncytial virus: A comprehensive

review of transmission, pathophysiology, and manifestation. Cureus. 2023 Mar;15(3):e36342.

doi: https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.36342

2. Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional

mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic

analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012 Dec;380(9859):2095–128.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0

3. Stucki M, Lenzin G, Agyeman PK, Posfay-Barbe KM, Ritz N, Trück J, et al. Inpatient

burden of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in Switzerland, 2003 to 2021: an analysis

of administrative data. Euro Surveill. 2024 Sep;29(39):2400119. doi: https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2024.29.39.2400119

4. Meslé MM, Sinnathamby M, Mook P, Pebody R, Lakhani A, Zambon M, et al.; WHO European

Region Respiratory Network Group. Seasonal and inter-seasonal RSV activity in the

European Region during the COVID-19 pandemic from autumn 2020 to summer 2022. Influenza

Other Respir Viruses. 2023 Nov;17(11):e13219. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/irv.13219

5. Fischli K, Schöbi N, Duppenthaler A, Casaulta C, Riedel T, Kopp MV, et al. Postpandemic

fluctuations of regional respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization epidemiology:

potential impact on an immunization program in Switzerland. Eur J Pediatr. 2024 Dec;183(12):5149–61.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-024-05785-z

6. Sauteur PM, Plebani M, Trück J, Wagner N, Agyeman PK. Ongoing disruption of RSV epidemiology

in children in Switzerland. Lancet Reg Heal; 2024. p. 45.

7. Rao S, Armistead I, Messacar K, Alden NB, Schmoll E, Austin E, et al. Shifting epidemiology

and severity of respiratory syncytial virus in children during the COVID-19 pandemic.

JAMA Pediatr. 2023 Jul;177(7):730–2. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.1088

8. Abu-Raya B, Viñeta Paramo M, Reicherz F, Lavoie PM. Why has the epidemiology of RSV

changed during the COVID-19 pandemic? EClinicalMedicine. 2023 Jul;61:102089. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102089

9. Hammitt LL, Dagan R, Yuan Y, Baca Cots M, Bosheva M, Madhi SA, et al.; MELODY Study

Group. Nirsevimab for prevention of RSV in healthy late-preterm and term infants.

N Engl J Med. 2022 Mar;386(9):837–46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2110275

10. Griffin MP, Yuan Y, Takas T, Domachowske JB, Madhi SA, Manzoni P, et al.; Nirsevimab

Study Group. Single-dose nirsevimab for prevention of RSV in preterm infants. N Engl

J Med. 2020 Jul;383(5):415–25. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1913556

11. Simões EA, Pahud BA, Madhi SA, Kampmann B, Shittu E, Radley D, et al.; MATISSE (Maternal

Immunization Study for Safety and Efficacy) Clinical Trial Group. Efficacy, Safety,

and Immunogenicity of the MATISSE (Maternal Immunization Study for Safety and Efficacy)

Maternal Respiratory Syncytial Virus Prefusion F Protein Vaccine Trial. Obstet Gynecol.

2025 Feb;145(2):157–67. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000005816

12. Shirley M. RSVPreF3 OA respiratory syncytial virus vaccine in older adults: a profile

of its use. Drugs Ther Perspect. 2025;41(1):1–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-024-01125-1

13. Papi A, Ison MG, Langley JM, Lee DG, Leroux-Roels I, Martinon-Torres F, et al.; AReSVi-006

Study Group. Respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F protein vaccine in older adults.

N Engl J Med. 2023 Feb;388(7):595–608. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2209604

14. Fourati S, Reslan A, Bourret J, Casalegno JS, Rahou Y, Chollet L, et al. Genotypic

and phenotypic characterisation of respiratory syncytial virus after nirsevimab breakthrough

infections: a large, multicentre, observational, real-world study. Lancet Infect Dis.

2024.

15. Saito M, Tsukagoshi H, Sada M, Sunagawa S, Shirai T, Okayama K, et al. Detailed evolutionary

analyses of the F gene in the respiratory syncytial virus subgroup A. Viruses. 2021 Dec;13(12):2525.

doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/v13122525

16. Goya S, Ruis C, Neher RA, Meijer A, Aziz A, Hinrichs AS, et al. Standardized phylogenetic

classification of human respiratory syncytial virus below the subgroup level. Emerg

Infect Dis. 2024 Aug;30(8):1631–41. doi: https://doi.org/10.3201/eid3008.240209

17. Ison MG, Hirsch HH. Community-acquired respiratory viruses in transplant patients:

diversity, impact, unmet clinical needs. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019 Sep;32(4):10–1128.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00042-19

18. Goldenberger D, Leuzinger K, Sogaard KK, Gosert R, Roloff T, Naegele K, et al. Brief

validation of the novel GeneXpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 PCR assay. J Virol Methods. 2020 Oct;284:113925.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviromet.2020.113925

19. Leuzinger K, Roloff T, Gosert R, Sogaard K, Naegele K, Rentsch K, et al. Epidemiology

of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 emergence amidst community-acquired

respiratory viruses. J Infect Dis. 2020 Sep;222(8):1270–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa464

20. Leung EC man, Chow VC ying, Lee MK ping, Tang KP san, Li DK cheung, Lai RW man. Evaluation

of the Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2/Flu/RSV Assay for Simultaneous Detection of SARS-CoV-2,

Influenza A and B Viruses, and Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Nasopharyngeal Specimens.

Hayden R, editor. J Clin Microbiol. 2021 Mar 19;59(4):e02965-20.

21. Mostafa HH, Carroll KC, Hicken R, Berry GJ, Manji R, Smith E, et al. Multicenter Evaluation

of the Cepheid Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2/Flu/RSV Test. McAdam AJ, editor. J Clin Microbiol.

2021 Feb 18;59(3):e02955-20.

22. Quick J, Grubaugh ND, Pullan ST, Claro IM, Smith AD, Gangavarapu K, et al. Multiplex

PCR method for MinION and Illumina sequencing of Zika and other virus genomes directly

from clinical samples. Nat Protoc. 2017 Jun;12(6):1261–76. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2017.066

23. Wang L, Ng TF, Castro CJ, Marine RL, Magaña LC, Esona M, et al. Next-generation sequencing

of human respiratory syncytial virus subgroups A and B genomes. J Virol Methods. 2022 Jan;299:114335.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviromet.2021.114335

24. Dyrdak R, Mastafa M, Hodcroft EB, Neher RA, Albert J. Intra- and interpatient evolution

of enterovirus D68 analyzed by whole-genome deep sequencing. Virus Evol. 2019 Apr;5(1):vez007.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/ve/vez007

25. Hodcroft EB, Dyrdak R, Andrés C, Egli A, Reist J, García Martínez De Artola D, et

al. Evolution, geographic spreading, and demographic distribution of Enterovirus D68.

Elde NC, editor. PLOS Pathog. 2022 May 31;18(5):e1010515. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1010515

26. Hadfield J, Megill C, Bell SM, Huddleston J, Potter B, Callender C, et al. Nextstrain:

real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics. 2018 Dec;34(23):4121–3.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty407

27. Aksamentov I, Roemer C, Hodcroft EB, Neher RA. Nextclade: clade assignment, mutation

calling and quality control for viral genomes. J Open Source Softw. 2021;6(67):3773.

doi: https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.03773

28. Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic

algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2015 Jan;32(1):268–74.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu300

29. Garcia-Maurino C, Brenes-Chacón H, Halabi KC, Sánchez PJ, Ramilo O, Mejias A. Trends

in age and disease severity in children hospitalized with RSV infection before and

during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2024 Feb;178(2):195–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.5431

30. Bourdeau M, Vadlamudi NK, Bastien N, Embree J, Halperin SA, Jadavji T, et al.; Canadian

Immunization Monitoring Program Active (IMPACT) Investigators. Pediatric RSV-associated

hospitalizations before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Oct;6(10):e2336863–2336863.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.36863

31. Eshaghi A, Duvvuri VR, Lai R, Nadarajah JT, Li A, Patel SN, et al. Genetic variability

of human respiratory syncytial virus A strains circulating in Ontario: a novel genotype

with a 72 nucleotide G gene duplication. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32807. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0032807

32. Trento A, Galiano M, Videla C, Carballal G, García-Barreno B, Melero JA, et al. Major

changes in the G protein of human respiratory syncytial virus isolates introduced

by a duplication of 60 nucleotides. J Gen Virol. 2003 Nov;84(Pt 11):3115–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.19357-0

33. Stein RT, Zar HJ. RSV through the COVID-19 pandemic: Burden, shifting epidemiology,

and implications for the future. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2023 Jun;58(6):1631–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.26370

34. Heemskerk S, Baliatsas C, Stelma F, Nair H, Paget J, Spreeuwenberg P. Assessing the

Impact of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions During the COVID-19 Pandemic on RSV Seasonality

in Europe. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2025 Jan;19(1):e70066. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/irv.70066

35. Scholz S, Dobrindt K, Tufts J, Adams S, Ghaswalla P, Ultsch B, et al. The Burden of

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) in Germany: A Comprehensive Data Analysis Suggests

Underdetection of Hospitalisations and Deaths in Adults 60 Years and Older. Infect

Dis Ther. 2024 Aug;13(8):1759–70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-024-01006-0

36. Kiefer A, Pemmerl S, Kabesch M, Ambrosch A. Comparative analysis of RSV-related hospitalisations

in children and adults over a 7 year-period before, during and after the COVID-19

pandemic. J Clin Virol. 2023 Sep;166:105530. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2023.105530

37. Hönemann M, Maier M, Frille A, Thiem S, Bergs S, Williams TC, et al. Respiratory Syncytial

Virus in Adult Patients at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Germany: Clinical Features

and Molecular Epidemiology of the Fusion Protein in the Severe Respiratory Season

of 2022/2023. Viruses. 2024 Jun;16(6):943. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/v16060943

38. Lastrucci V, Pacifici M, Puglia M, Alderotti G, Berti E, Del Riccio M, et al. Seasonality

and severity of respiratory syncytial virus during the COVID-19 pandemic: a dynamic

cohort study. Int J Infect Dis. 2024 Nov;148:107231. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2024.107231

39. Pierangeli A, Nenna R, Fracella M, Scagnolari C, Oliveto G, Sorrentino L, et al. Genetic

diversity and its impact on disease severity in respiratory syncytial virus subtype-A

and -B bronchiolitis before and after pandemic restrictions in Rome. J Infect. 2023 Oct;87(4):305–14.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2023.07.008

40. Cutrera R, Ciofi Degli Atti ML, Dotta A, D’Amore C, Ravà L, Perno CF, et al. Epidemiology

of respiratory syncytial virus in a large pediatric hospital in Central Italy and

development of a forecasting model to predict the seasonal peak. Ital J Pediatr. 2024 Apr;50(1):65.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-024-01624-x

41. Redlberger-Fritz M, Springer DN, Aberle SW, Camp JV, Aberle JH. Respiratory syncytial

virus surge in 2022 caused by lineages already present before the COVID-19 pandemic.

J Med Virol. 2023 Jun;95(6):e28830. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.28830

42. Rios-Guzman E, Simons LM, Dean TJ, Agnes F, Pawlowski A, Alisoltanidehkordi A, et

al. Deviations in RSV epidemiological patterns and population structures in the United

States following the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Commun. 2024 Apr;15(1):3374. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47757-9

43. de Korne-Elenbaas J, Rimaite A, Topolsky I, Dreifuss D, Bürki C, Fuhrmann L, et al. Wastewater-based

sequencing of Respiratory Syncytial Virus enables tracking of lineages and identifying

mutations at antigenic sites. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2025 medRxiv [cited 2025 Mar 7].

p. 2025.02.28.25321637. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.02.28.25321637v1 10.1101/2025.02.28.25321637

44. Yunker M, Fall A, Norton JM, Abdullah O, Villafuerte DA, Pekosz A, et al. Genomic

Evolution and Surveillance of Respiratory Syncytial Virus during the 2023-2024 Season.

Viruses. 2024 Jul;16(7):1122. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/v16071122

45. de Jesus-Cornejo J, Hechanova-Cruz RA, Sornillo JB, Okamoto M, Oshitani H; Viral Etiology

Working Group. Prolonged RSV circulation in 2022 to 2023 associated with the emergence

of a novel RSV-B clade in Biliran, Philippines. J Infect. 2025 Apr;90(4):106467. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2025.106467

46. Jafri HS, Wu X, Makari D, Henrickson KJ. Distribution of respiratory syncytial virus

subtypes A and B among infants presenting to the emergency department with lower respiratory

tract infection or apnea. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013 Apr;32(4):335–40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0b013e318282603a

47. Midulla F, Nenna R, Scagnolari C, Petrarca L, Frassanito A, Viscido A, et al. How

respiratory syncytial virus genotypes influence the clinical course in infants hospitalized

for bronchiolitis. J Infect Dis. 2019 Jan;219(4):526–34. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiy496

48. Jung JA, Wi PH, Kim H. Kim H sol. Comparisons of clinical characteristics between

Respiratory Syncytial Virus A and B infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(2):AB131.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2019.12.520

49. Vos LM, Oosterheert JJ, Kuil SD, Viveen M, Bont LJ, Hoepelman AI, et al. High epidemic

burden of RSV disease coinciding with genetic alterations causing amino acid substitutions

in the RSV G-protein during the 2016/2017 season in The Netherlands. J Clin Virol.

2019 Mar;112:20–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2019.01.007

50. Irwin KK, Renzette N, Kowalik TF, Jensen JD. Antiviral drug resistance as an adaptive

process. Virus Evol. 2016 Jun;2(1):vew014. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/ve/vew014

51. Gosert R, Leuzinger K, Kuznetsov A, Neher RA. Respiratory syncytial virus A amplicon

sequencing dataset, Basel, Switzerland, 2021-2024 [dataset]. 2025 Jun 16 [cited 2025

Sep 23]. Pathoplexus. Available from: 10.62599/PP_SS_201.2

52. Gosert R, Leuzinger K, Kuznetsov A, Neher RA. Respiratory syncytial virus B amplicon

sequencing dataset, Basel, Switzerland, 2020-2024 [dataset]. 2025 Jun 16 [cited 2025

Sep 23]. Pathoplexus. Available from: 10.62599/PP_SS_202.2

Appendix

The appendix is available in the PDF version of the article and the supplementary

files are available for download as separate files at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4600.