Modelling the health and cost implications of expanded access to HIV, HCV and sexually

transmitted infection testing in Switzerland

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4581

Harsh Vivek Harkareab,

Marina Antillonab,

Axel J. Schmidtc,

Fabrizio Tediosiabd

a Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute,

Allschwil, Switzerland

b University of Basel, Basel,

Switzerland

c Sigma Research, Department of

Public Health, Environments and Society, London School of Hygiene and Tropical

Medicine, London, United Kingdom

d University of Milan, Milan, Italy

Summary

BACKGROUND: This study was conducted as part of the Swiss

National Programme to Stop HIV, Hepatitis B Virus, Hepatitis C Virus and Sexually

Transmitted Infections (NAPS), which aims to reduce the spread of sexually transmitted

infections in Switzerland. The goal was to identify the most effective and cost-efficient

screening strategies to lower the incidence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV),

hepatitis C virus (HCV), syphilis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia

trachomatis by improving access to screening.

METHODS: A Markov model

was developed to assess the impact of various screening strategies among key populations

over two years, including men who have sex with men (MSM), female sex workers

(FSW) and people who inject drugs (PWID). The model further stratifies individuals

based on partner number (MSM) and injection-equipment sharing (PWID). Comprehensive

cost estimates for screening and treatment were derived from insurance data, literature

and expert opinions. The effectiveness of screening interventions was evaluated

by measuring reductions in disease incidence and cost savings, comparing the costs

of screening to those of acute and chronic care for prevented infections.

RESULTS: Increased screening frequency among key populations

led to a reduction in incidence for all five infections studied. The largest effect

was seen in people who inject drugs who share injecting equipment, where HCV incidence

fell by up to 76% with four annual screens. However, only screening for HIV, HCV

and syphilis proved to be cost-saving. Screening for Chlamydia trachomatis

and Neisseria gonorrhoeae consistently incurred net costs due to the high

screening costs and relatively low treatment costs.

CONCLUSION: Targeted expansion of screening among key populations

can reduce the incidence of HIV, HCV and syphilis in Switzerland, with regular screening

offering potential cost savings to insurers under specific coverage and treatment

scenarios.

Abbreviations

- FSW

-

female sex worker

- MSM

-

men who have sex with men

- PWID

-

people who inject drugs

Introduction

The Swiss National Programme to Stop HIV, Hepatitis B Virus, Hepatitis C Virus

and Sexually Transmitted Infections (NAPS) aims to eliminate

HIV and HCV transmission and reduce the spread of sexually transmitted infections

in Switzerland by 2030 [1]. Previous research has shown that increasing screening

frequency can significantly lower the prevalence of certain bacterial sexually

transmitted infections in Switzerland, such as syphilis [2]. However, the optimal

screening intervals for other sexually transmitted infections, such as Neisseria

gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis, remain uncertain. Currently,

sexually transmitted infection screening and testing in Switzerland is not covered

by compulsory health insurance unless symptoms are present or there is a justified

suspicion of infection. HIV testing is covered under provider-initiated counselling

and testing (PICT) guidelines, while HCV screening is not covered [3].

With the increasing recognition of asymptomatic sexually

transmitted infection transmission, assessing the effectiveness of various screening

strategies within the Swiss context has become increasingly important [4]. Previous

studies have highlighted the heightened infection risk among specific populations

such as men who have sex with men (MSM) and female sex workers (FSW) [5, 6]. In

response, NAPS prioritises expanding screening efforts and improving access to testing

for at-risk groups. This includes revising testing strategies based on evidence

and ensuring equitable access for all, including individuals with limited financial

resources.

The present modelling study was conducted with two key objectives:

to assess the impact of increased screening frequencies and to provide guidance

for official sexually transmitted infection screening recommendations by the Swiss

Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH). Currently, screening guidelines are available

only from the Swiss AIDS Federation (Aids-Hilfe Schweiz [AHS]) [7].

The study seeks to identify the most effective screening

strategy, considering key populations and optimal screening frequencies to reduce

the incidence of HIV, HCV, syphilis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia

trachomatis in Switzerland. Additionally, it evaluates the economic impact of

integrating such a strategy into the Swiss compulsory health insurance benefit package.

Methods

Screening strategies

Screening strategies are determined based on a combination

of factors, including key population, type of infection and screening frequency.

Following the recommendations outlined by the Swiss AIDS Federation and considering

data availability, the study focuses on three key populations:

- men who have sex with men (MSM)

- female sex workers (FSW)

- people who inject drugs (PWID)

MSM and PWID were further subdivided into two subgroups: those at higher

risk and those at lower risk of sexually transmitted infections. According to recommendations

from the Swiss AIDS Federation, MSM in Switzerland are considered at higher risk

if they had 12 or more non-steady partners per year [8]. For PWID, the Swiss

Federal Office of Public Health LoveLife campaign defines higher risk of HIV and

HCV as having ever shared needles or injection equipment [9].

Screening frequencies for all five infections under study

– HIV, hepatitis C virus, syphilis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia

trachomatis – were modelled based on the behavioural risk level of each

target group: individuals at lower risk undergo annual screening, while those at

higher risk are screened two to four times per year [7]. All FSW were classified

as being at high risk of sexually transmitted infections due to their typically

high number of partners.

A significant proportion of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

users in Switzerland are enrolled in the Swiss PrEPared study, where they undergo

frequent screening for sexually transmitted infections [10]. Consequently, pre-exposure

prophylaxis users were excluded from our analysis.

We modelled screening for different combinations of key populations

and infections based on Swiss AIDS Federation recommendations [7]. Specifically,

we simulated the impact of screening for all infections except HCV among MSM and

FSW, while for PWID, screening was modelled only for HIV and HCV.

Screening frequencies were defined in increments, starting

from a baseline level (0×) and increasing by one additional annual screen up to

a maximum of four screens per year (4×). The baseline screening frequency (0×) represents

the current status quo of testing within the key populations in Switzerland, without

any interventions offering screening at reduced prices. A 1× screening scenario

refers to the provision of one annual screen for everyone within a given key population,

taking the actual testing uptake rate into account.

Based on the above recommendations, a total of 36 screening

strategies were defined and simulated. Additionally, 16 comparator scenarios were

established, each representing a baseline screening frequency for each disease and

key population, simulating the current observed screening uptake in Switzerland.

The modelling conventions for the key populations are as follows: MSM with higher

partner numbers (MSM_HR), MSM with lower partner numbers (MSM_LR), female sex

workers, people who inject drugs with equipment sharing (PWID_HR) and other PWID

(PWID_LR). A list of all simulated screening frequencies is provided in the appendix

(table S2).

Modelling approach and outcomes

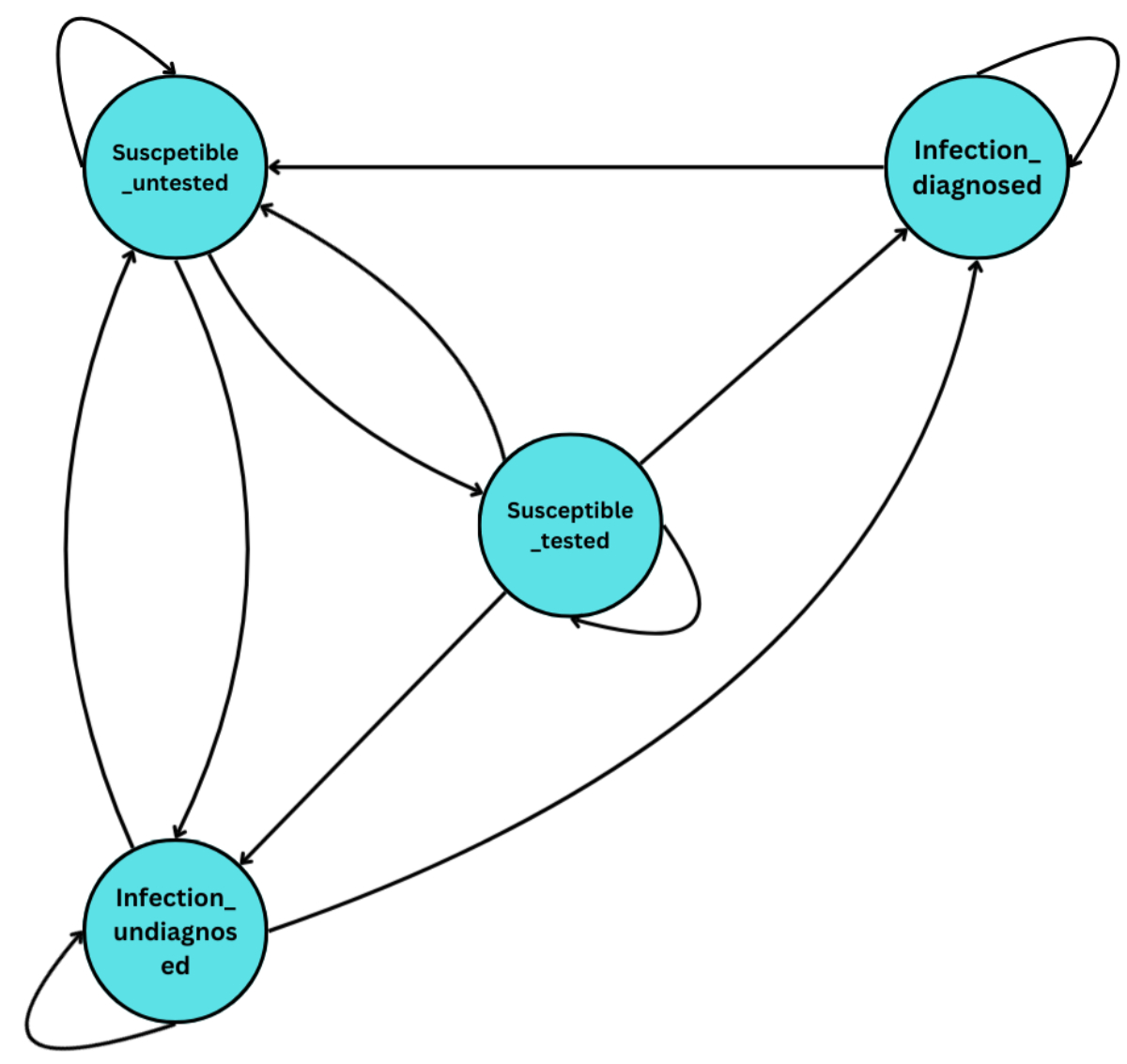

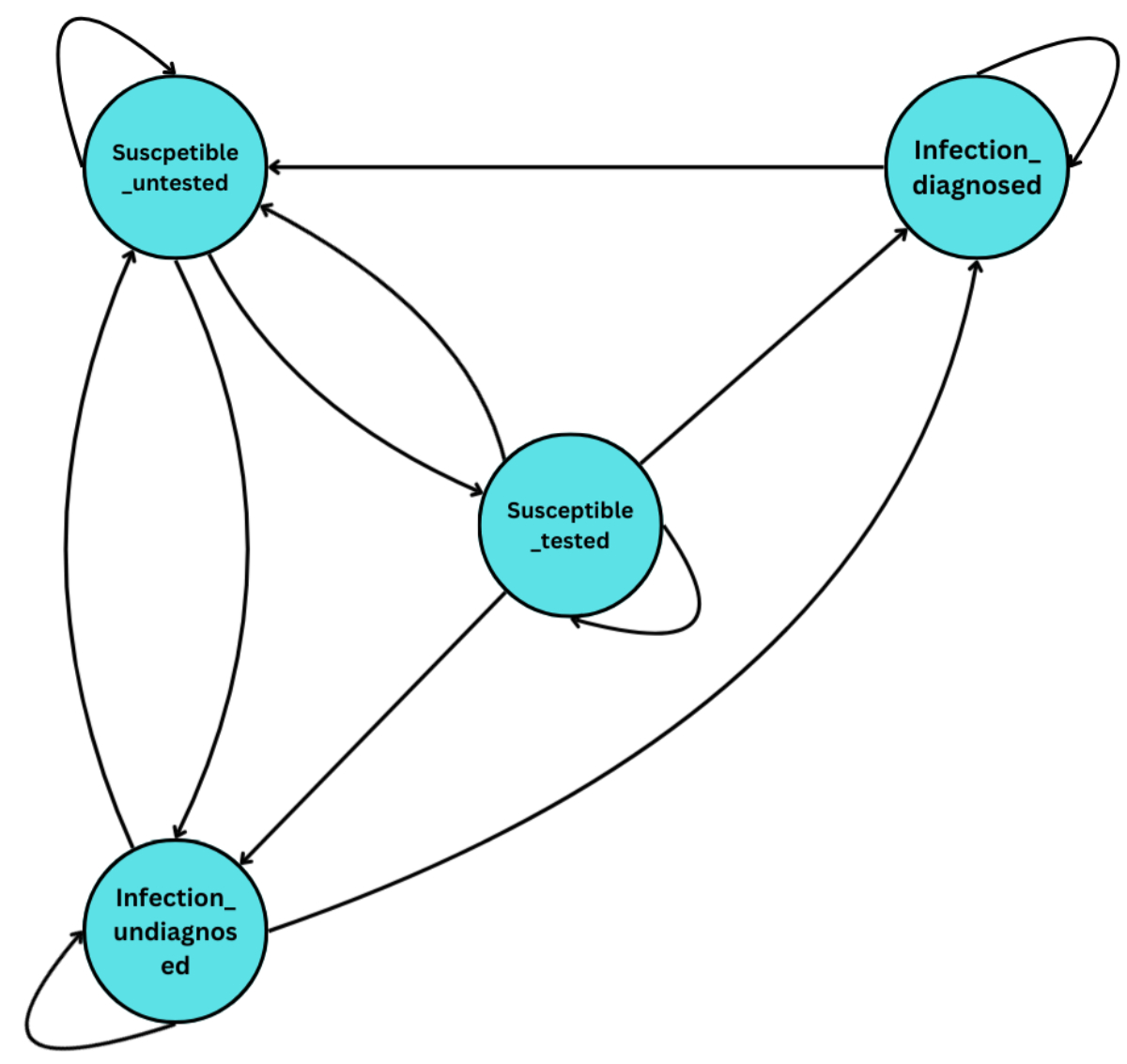

A Markov model was developed to simulate the impact of increased

screening within each target population. The model runs on weekly time steps and

comprises four health states: (1) susceptible, untested, (2) susceptible, tested,

(3) infected, diagnosed, and (4) infected, undiagnosed, as outlined in figure 1.

The transition probabilities for each infection were defined separately and were

informed by a variety of data sources as well as published literature as outlined

in the appendix. The observed values of the population were fitted

to a Dirichlet distribution – a conjugate prior to the multinomial distribution

– and sampled 1000 times to incorporate parameter uncertainty.

Figure 1Markov model structure. The model consists of four health states: (1) susceptible

and untested, (2) susceptible

and tested, (3) infected but undiagnosed, and (4) infected and diagnosed. Individuals

can transition between these states on a weekly basis. Not all infections involve

all transitions. For example, in the case of HIV, the transition from “Infection,

diagnosed” to “Susceptible, untested” is zero, as individuals do not return to an

untested susceptible state after diagnosis. Similarly, transition probabilities

may differ by infection type depending on natural clearance or treatment efficacy.

For each screening strategy, we assessed two primary outcomes:

- Health benefit: Decrease in incidence

of infection in the first and the second year after implementing the expanded screening

strategy, as compared to the baseline incidence under the status quo screening frequency.

- Cost to insurance providers: This

will include comparing the cost of screening with the cost of acute- and chronic-care

treatment for HIV and HCV, or treatment of severe complications for syphilis, Neisseria

gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis.

Healthcare in Switzerland is funded through

mandatory basic insurance, with individuals paying monthly premiums and covering

medical costs up to a set deductible (franchise). Beyond this, insurance covers

expenses minus a co-payment, until a maximum out-of-pocket limit is reached. Except

for HIV, screening for sexually transmitted infections and HCV is covered by insurance

when symptoms are present or an infection is suspected. Otherwise, screening is

subject to the deductible, which may discourage access [11].

To assess the cost implications for insurance providers,

we analysed two distinct scenarios of insurance coverage: one with and one without

the waiver of the deductible component (referred to here as with or without franchise-waiver).

The decision to offer screening with or without a franchise-waiver substantially

affects the estimated financial burden on insurers, as implementing a franchise-waiver

leads to higher costs for them. A screening strategy is considered cost-saving if

its total implementation cost is lower than the projected expenses for treating

the infections it prevents. Additionally, we assumed that the screening uptake rate

remained constant, regardless of whether a franchise-waiver is in place. We considered

the full range of deductible thresholds offered in Switzerland (CHF 300 to CHF 2500)

for the franchise-waiver scenario. Detailed assumptions on the franchise-level enrolment

and insurer cost shares can be found in the appendix.

The cost implications to insurance providers

under different screening evaluation strategies were assessed in terms of their

cost-saving potential. Cost-saving

outcomes were evaluated across four scenarios, ordered by increasing cost assumptions:

(1) acute treatment with franchise-waiver, (2) acute treatment without franchise-waiver,

(3) chronic treatment with franchise-waiver, and (4) chronic treatment without franchise-waiver.

This hierarchical structure reflects the logic that if a screening strategy is cost-saving

under the most conservative assumption (acute treatment with franchise-waiver),

it will also be cost-saving under all less-conservative scenarios. Conversely, if

a strategy is only cost-saving under the final scenario (chronic treatment without

franchise-waiver), it will not be cost-saving under any of the cheaper evaluation

strategies. This framework allows us to assess the robustness of each strategy’s

cost-saving potential across increasing cost assumptions.

To assess the validity of our model,

we compared the model-estimated incidence rates under baseline screening conditions

with empirically observed incidence data for key populations, including MSM and

FSW.

Data sources

Multiple data sources were used to inform model parameters.

Empirical data on screening uptake, test positivity, disease prevalence and risk

behaviours were drawn from BerDa, the Swiss STAR trial and EMIS-2017 [5, 12]. BerDa

is an electronic tool developed by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health for

history-taking, counselling and recording related to HIV, HCV and sexually

transmitted infection [3]. It captures self-reported information on sexual risk,

behaviours and previous infections. Additionally, most test centres using BerDa

also reported laboratory-confirmed diagnoses of HIV, HCV and sexually

transmitted infections. For our analysis, we used BerDa data for one year, from

June 2023 to June 2024. The data was collected from 19 voluntary counselling and

testing centres across Switzerland, of which only two did not report laboratory-confirmed

outcomes. The Swiss STAR trial also provides laboratory-confirmed diagnoses, whereas

EMIS-2017 relies on self-reported data.

Additional parameters – such as treatment

success and uptake rates, diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, proportion of

symptomatic and asymptomatic infections and population estimates – were obtained

from published literature. Population estimates were updated to reflect the current

year based on Switzerland’s overall population growth trend. SWICA provided data

on health expenditure and insurance demographic profiles. For model validation,

empirically observed incidence rates in Switzerland were taken from the most recent

population-specific, laboratory-confirmed incidence estimates available, derived

from the Swiss STAR trial, which was conducted in 2017 [5, 6]. Data from the Swiss

HIV Cohort Study and Swiss PrEPared could not be obtained. A summary of key model

parameters and data sources is presented in table 1, while further details, including

a complete list of model parameters and their sources, are provided in appendix

table S1.

Table 1Overview of modelling parameters and key data sources. Notes:

Exact values for each parameter can be found in appendix table S1.

| Parameter category |

Parameters |

Key data sources |

| Population size |

Size of the populations

of men who have sex with men, female sex workers and people who inject drugs |

Schmidt

& Altpeter (2019) [37]; Vernazza et al. (2020) [6]; Bihl et al. (2021) [35]; UNAIDS

[38] |

| Risk behaviour |

Proportion engaging

in high-risk behaviour (e.g. multiple partners, equipment sharing) |

BerDa EMIS-2017 [39];

Swiss STAR Trial [40] |

| Disease prevalence |

HIV, syphilis, Neisseria

gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, HCV prevalence by group |

Bigler et al. (2023)

[41]; Schmidt & Altpeter (2019) [37]; Swiss STAR Trial [40]; UNODC [42] |

| Screening uptake |

Proportion tested

in past year by infection and risk group |

BerDa EMIS-2017 [39];

Expert opinion |

| Test characteristics |

Test-positivity rate

and diagnostic sensitivity and specificity by infection |

BerDa EMIS-2017 [39]; Nevin et al. (2008) [43]; Park et al. (2020) [44]; Vetter et

al. (2020) [45] |

| Treatment parameters |

Treatment uptake

and success rates by infection |

Expert opinion; Kohler et al. (2015) [46]; Nevin et al. (2008) [43]; Wandeler et al.

(2015) [47] |

| Transmission parameters |

Onward infections

per untreated case |

Garnett et al. (1997, 1999) [48, 49]; Paltiel et al. (2006) [50]; Potterat et al.

(1999) [51] |

| Symptomatology |

Proportion of asymptomatic

infections |

Cui et al. (2024) [52]; ECDC [53]; Maheshwari et al. (2008) [54]; Martin-Sanchez et

al. (2020)

[56] |

| Self-clearance (HCV) |

Proportion of untreated

infections that self-clear |

Grebely et al. (2014)

[56] |

Health insurance cost estimates

To estimate the cost implications of screening and treatment,

we also estimated the cost of a single screening test as well as the costs of acute-care

treatment for all five infections, chronic-care treatment for HIV and HCV, and of

severe complications of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis,

syphilis. The estimated cost of screening is inclusive of the cost of consultation

as well as the actual screening cost. Consultation costs for screening for any test

include 20 minutes of consultation time with an infection specialist as well as

personnel time for blood draw, for preparing the test, and for communicating results

to the patient (appendix table S5). The cost of screening is estimated from data from

SWICA insurance, which covers 20% of the Swiss population and has data on the actual

number of tests undertaken and costs incurred by different test centres. Aggregated

SWICA data from 2021–2022 provide information on insured individuals, completed

screening tests, and associated costs, stratified by age group and franchise level.

The mean and 95% CI of the cost of a single screening test was calculated by aggregating

over the age group, franchise and year. In line with approved practices, costs for

Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis screening include

testing from three separate swab sites [13].

The cost of medication and treatment were added to the cost

of consultation to obtain the final cost of treating one infection. Treatment and

medication costs were derived from the official tariff structure of medical services

and from the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health-mandated costs for speciality

medical products and services [14, 15]. Treatment guidelines for each infection

were taken from the Swiss Society for Infectiology [16].

While the costs used in this analysis are estimated from

a macroeconomic societal perspective, we also calculated the costs of treating a

single infection – both acute and chronic care. A summary of the screening and treatment

costs are tabulated in appendix table S3. The costing methodology and guidelines

are further detailed in the tables S4 and S5 in the appendix.

Sensitivity analysis

To assess the robustness of our model results to variations

in key input parameters, we ran sensitivity analyses, comparing changes to the status

quo values based on the observed data. The choice of these sensitivity analyses

was based on the parameters that had the most uncertainty and the greatest potential

to influence results, as well as with the least available data:

- a

20% increase in the screening uptake rate;

- a

10% increase in the test-positivity rate;

- a

25% decrease in the onward infection transmission rate.

A detailed description of the modelling methods can be found

in the appendix.

Results

Impact on incidence

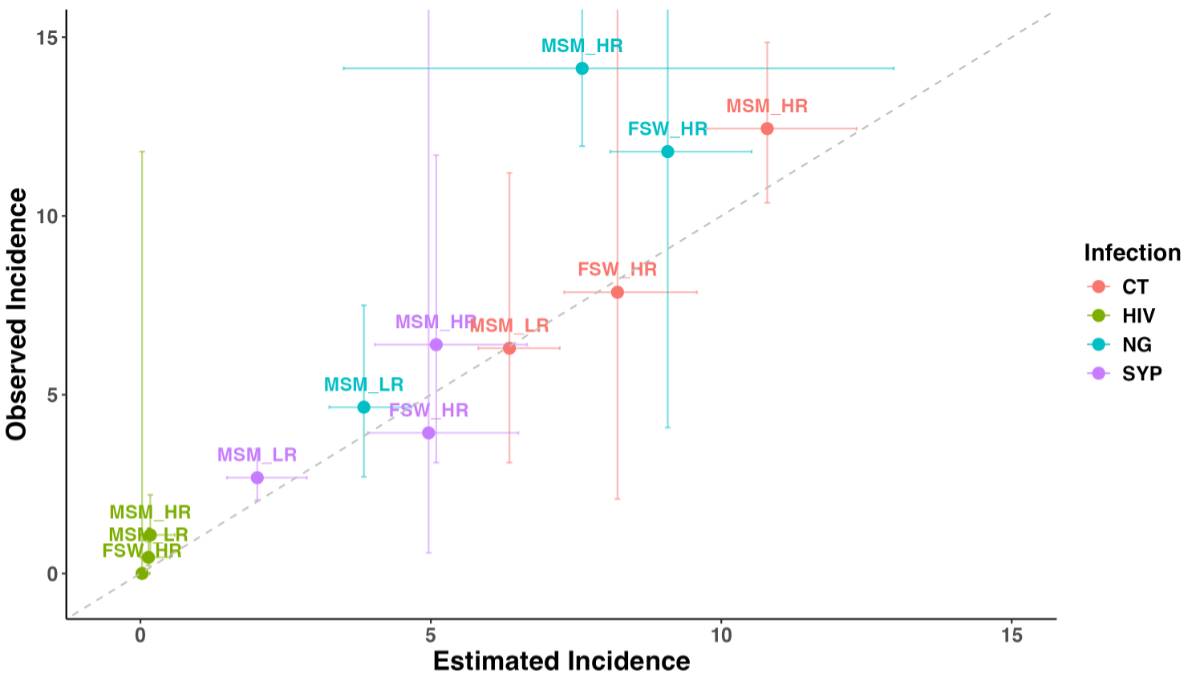

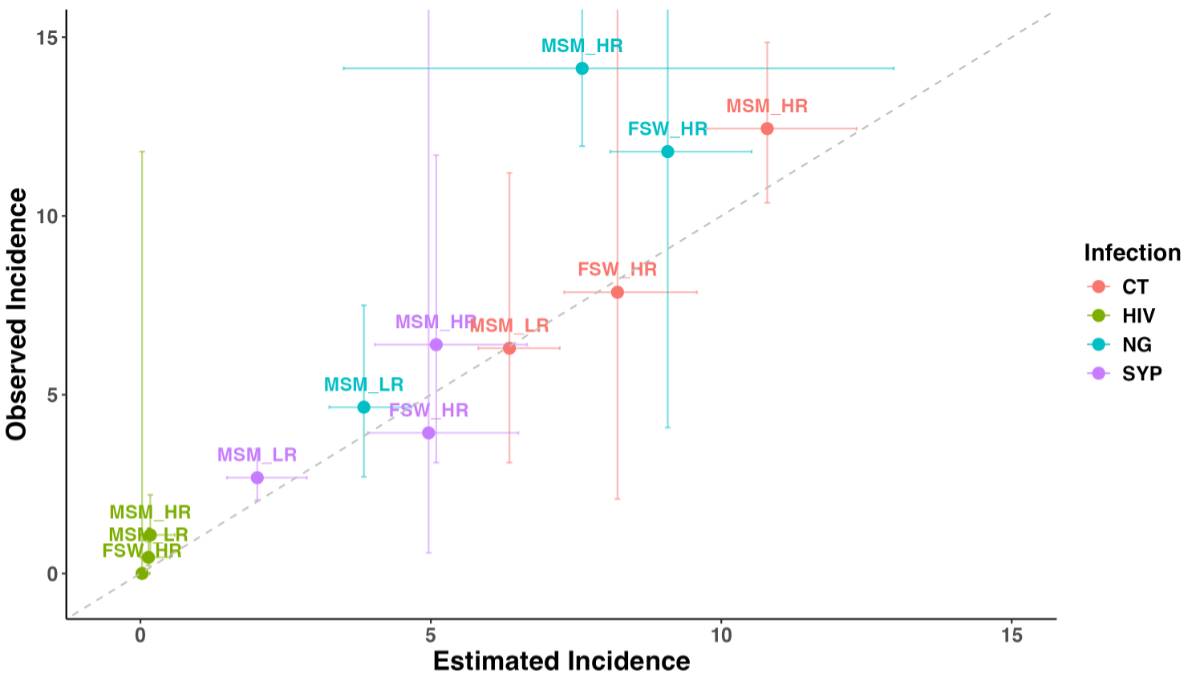

To validate the Markov transition dynamics

of our model, we compared the model-estimated incidence of HIV, syphilis, Neisseria

gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis under the baseline status quo screening

frequency with the incidence observed in the STAR trial for the key populations

of MSM and FSW [5, 6]. Figure 2 presents a comparison of the model-estimated incidence

against the observed incidence. Except for Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the high-partner-number

MSM group, our model accurately estimates the observed incidence. Due to a lack

of data on population-representative incidence estimates, we were unable to compare

our results for PWID.

Figure 2Comparison of model-estimated and observed incidence per 100 person-years.

The model-estimated incidence was compared with observed incidence across

various populations for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), syphilis (SYP),

Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Observed incidence

data was obtained from the Swiss STAR trial. The vertical bars show the 95%

confidence intervals of the incidence in the trial (observed incidence) and the

horizontal bars show the 95% predictive intervals of our model with re-sampling

of parameter values (estimated incidence). FSW: female

sex workers; MSM_HR: men who have sex with men with higher partner numbers; MSM_LR:

men who have

sex with men with lower partner numbers.

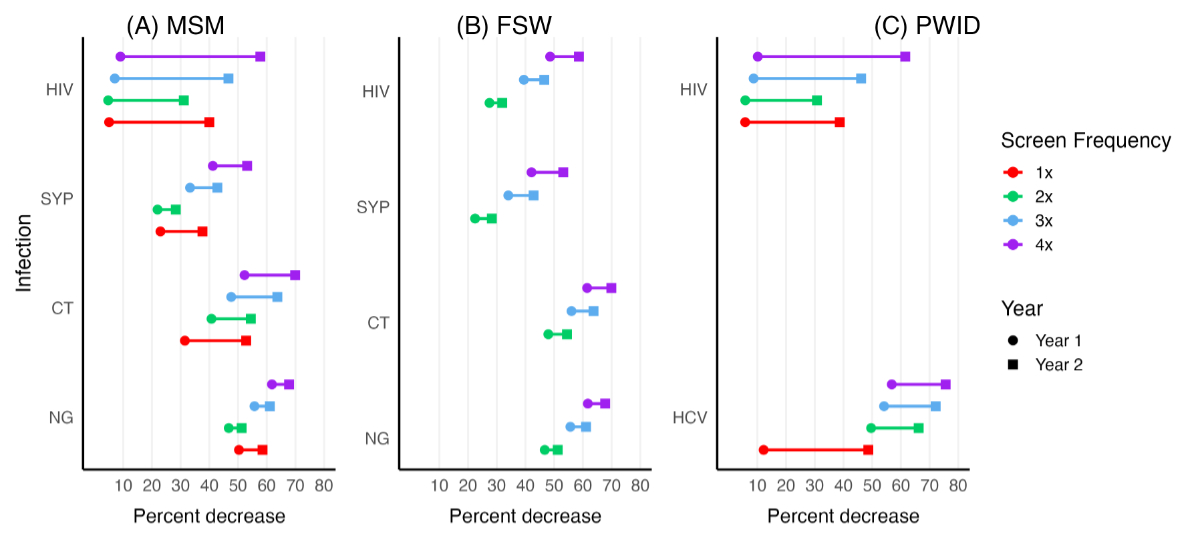

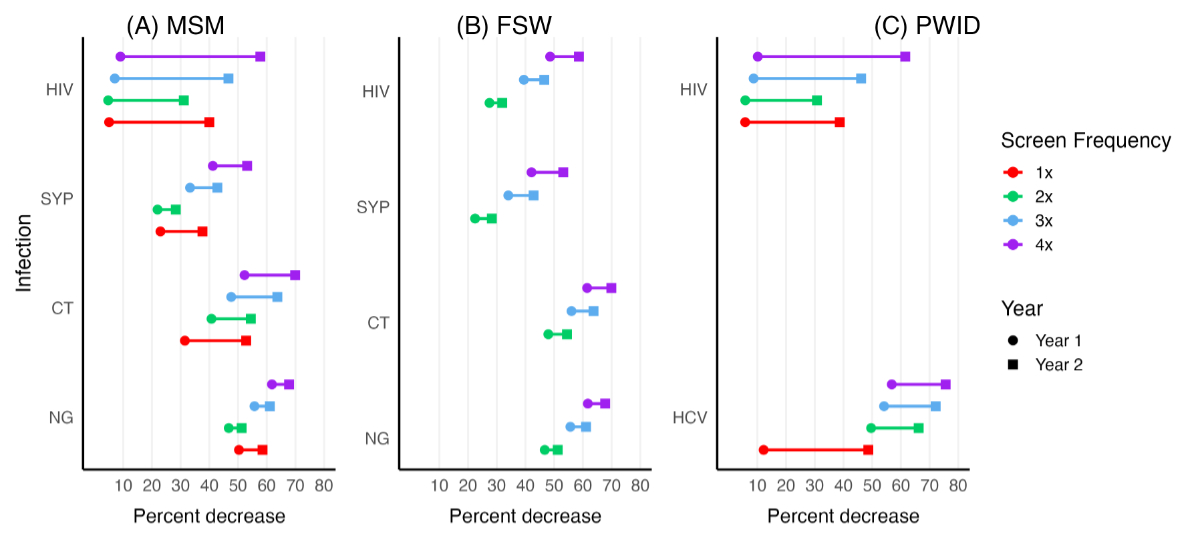

Figure

3 illustrates the impact of expanded sexually transmitted infection screening on

incidence in Switzerland. As the screening frequency increases, incidence declines

across all infections as compared to the baseline incidence under the status quo

screening frequency. The most prominent reduction is observed for HCV among high-risk

PWID: a 76% decrease with 4× annual screens by year 2.

Figure 3Percentage decrease in incidence by infection and key population over time. The percentage

reduction is estimated for different screening frequencies

over a two-year period. In this dumbbell plot, the circle denotes the average

reduction in year 1, while the square represents the corresponding reduction in

year 2. Annual screening (1×) was available exclusively for men who have sex with

men (MSM) and people who inject drugs (PWID) in the low-risk groups, with

no 1× screen provided for the female sex workers (FSW) group. In contrast, screening

frequencies of 2×, 3× and 4× per year were offered only to MSM and PWID in the

high-risk groups and to all FSW. CT: Chlamydia trachomatis; HIV: human

immunodeficiency virus; NG: Neisseria gonorrhoeae; SYP: syphilis.

Among

MSM, Neisseria gonorrhoeae incidence shows a substantial decline, primarily

due to its already high baseline observed incidence. Similarly, HIV also exhibits

a significant reduction, largely driven by the high screening uptake rate. This

effect is, however, smaller in magnitude as compared to other infections due to

its already low prevalence. Screening strategies with 1× annual screening for any

infection have a more pronounced effect on incidence reduction, as they target a

larger population – MSM with lower partner numbers – whereas higher screening frequencies

(2×, 3× and 4×) are limited to MSM with higher partner numbers, a much smaller population.

Among

FSW, where observed incidence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia

trachomatis is high, screening has the greatest impact on reducing incidence

for these two infections. Despite the already low HIV incidence in FSW, the high

testing uptake rate results in a significant reduction in incidence.

For HCV

in PWID, the impact of 1× annual screening is relatively smaller, reflecting the

high test-positivity rate among PWID who don’t report sharing of drug use equipment.

The impact of 1× annual screening on HIV is higher than 2× but smaller than 3× and

4× annual screening because of the larger number of PWID not sharing drug use equipment

as well as the low prevalence in the population.

Impact on costs to insurance providers

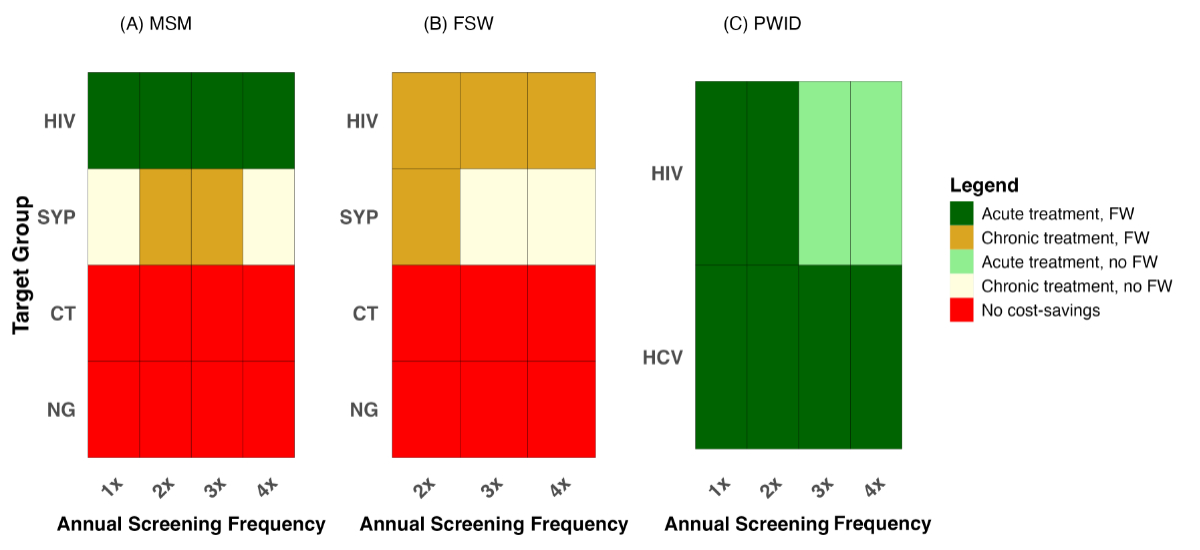

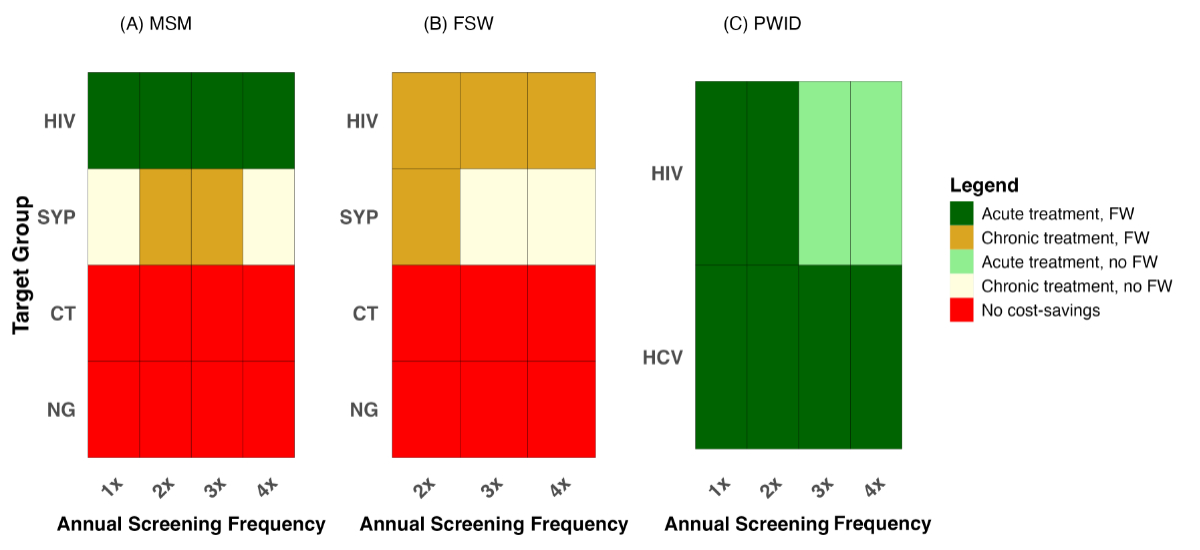

Figure 4 presents the estimated

annual cost savings under different screening strategies by key population from

the perspective of insurers. Cost savings are evaluated based on the type of insurance

coverage – franchise-waiver or no franchise-waiver – and treatment costs (acute

or chronic care). Given that acute-care treatment costs are typically the lowest,

cost-savings are more limited under this framework.

Figure 4Cost savings under different

screening strategies and insurance coverage. Each screening

strategy reflects a combination of screening frequency and infection type. Cost

savings are shown separately for key populations: (A) men who have sex with men

(MSM), (B) female sex workers (FSW) and (C) people who inject drugs (PWID).

Estimates are presented across insurance scenarios – with or without a

franchise-waiver (FW) – and treatment coverage assumptions (acute or chronic

care). Importantly, if a strategy is cost-saving under the “acute treatment, franchise-waiver”

scenario, it remains cost-saving under all other, more expensive combinations.

In contrast, strategies that are only cost-saving under the “chronic treatment,

no franchise-waiver” scenario are not cost-saving in any other case. Red cells

indicate strategies that are not cost-saving. All other colours represent

cost-saving strategies, classified by cost and insurance assumptions as

detailed in the figure legend. Please also note: 1× screening is offered only

to low-risk MSM and PWID groups, which represent larger population segments

compared to their high-risk counterparts. CT: Chlamydia trachomatis; HIV: human

immunodeficiency virus; NG: Neisseria gonorrhoeae; SYP: syphilis.

Cost-saving outcomes were assessed across

four evaluation scenarios, ordered by increasing cost assumptions: (1) acute treatment

with franchise-waiver, (2) acute treatment without franchise-waiver, (3) chronic

treatment with franchise-waiver, and (4) chronic treatment without franchise-waiver.

A strategy deemed cost-saving under a more conservative cost scenario (acute treatment

with franchise-waiver) is also considered cost-saving under all scenarios that are

more costly to insurance providers. In figure 4, dark green indicates strategies

that are cost-saving under the most conservative assumption – acute treatment with

franchise-waiver – and thus also under all other evaluation scenarios. Light green

reflects strategies that are cost-saving under acute treatment without franchise-waiver

and under all subsequent scenarios, but not under the most conservative. Ochre denotes

strategies that are cost-saving under both chronic treatment scenarios but not under

either acute scenario. Pale yellow indicates strategies that are cost-saving only

under the most generous and costly evaluation condition: chronic treatment without

franchise-waiver. Red represents strategies that are not cost-saving under any of

the four evaluation scenarios.

From a macroeconomic societal

perspective, a cost saving is more likely when considering chronic-care costs, as

these are generally higher than acute-care costs – except in the case of Neisseria

gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis. With a franchise-waiver, insurers

bear a larger share of screening costs, making it more challenging for screening

strategies to be cost-saving. Conversely, integrating screening into the health

insurance framework without a franchise-waiver would impose a lower financial burden

on insurers. Thus, strategies that are cost-saving under the “chronic treatment,

no franchise-waiver” scenario are not cost-saving under any other scenario.

Overall, offering 1–4× annual

screens to each key population is expected to be cost-saving for HIV, HCV and syphilis

at different levels of treatment and insurance coverage. However, for Neisseria

gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis, cost savings are not anticipated

under any combination of treatment and insurance coverage. These findings were robust

under the different sensitivity scenarios conducted.

HIV had the lowest reduction

in the absolute number of infections due to its already low prevalence, but the

cost of treatment was the highest, thus making it cost-saving. Despite the large

reductions in incidence for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia

trachomatis, the high screening costs coupled with relatively low treatment

costs make them unlikely to be cost-saving. Detailed results of screening impact

on absolute values of infections prevented, screening and treatment costs are shown

in the appendix in tables S7–S9.

Table 2 presents the estimated annual cost savings (in thousands

of CHF) for each screening strategy, disaggregated by infection, key population,

screening frequency and evaluation scenario over one year. Cost-saving potential

is greatest for HIV, particularly among MSM with fewer than 12 sexual partners a

year (MSM_LR), where annual screening (1×) yields over CHF 261 million in savings

under the chronic treatment without franchise-waiver scenario. Substantial savings

are also observed for high-frequency screening among MSM_HR and for HCV screening

among PWID, especially those not sharing injection equipment. In contrast, screening

for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis consistently results

in net financial losses, reflecting high screening costs relative to treatment costs.

For syphilis, cost savings are modest and scenario-dependent, with benefits observed

primarily under more generous cost evaluation assumptions.

Table 2Estimated cost savings

by comparing screening costs with treatment costs prevented for different

combinations of screening and treatment coverage and screening scenarios over

one year.

| Infection |

Key

population |

Screening frequency |

Estimated

cost savings (in thousands of CHF) |

| Acute

treatment, franchise-waiver screening |

Acute

treatment, no franchise-waiver screening |

Chronic

treatment, franchise-waiver screening |

Chronic

treatment, no franchise-waiver screening |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) |

MSM_LR |

1× |

17,111 |

19,616 |

258,818 |

261,323 |

| MSM_HR |

2× |

6,,203 |

6,940 |

88,700 |

89,437 |

| 3× |

5967 |

6,713 |

86,411 |

87,157 |

| 4× |

5,800 |

6,550 |

84,751 |

85,501 |

| Female sex workers |

2× |

−1,447 |

−493 |

13,111 |

14,065 |

| 3× |

−1,721 |

−760 |

10,411 |

11,372 |

| 4× |

−1,913 |

−945 |

8,539 |

9,507 |

| PWID_LR |

1× |

2,013 |

2,368 |

32,249 |

32,604 |

| PWID_HR |

2× |

631 |

737 |

9,963 |

10,069 |

| 3× |

591 |

698 |

9,550 |

9,657 |

| 4× |

566 |

675 |

9,339 |

9,448 |

| Syphilis |

MSM_LR |

1× |

−7,884 |

−5,221 |

−3,044 |

−381 |

| MSM_HR |

2× |

−2,225 |

−1,440 |

580 |

1,365 |

| 3× |

−2,257 |

−1,471 |

142 |

928 |

| 4× |

−2,278 |

−1,492 |

−162 |

624 |

| Female sex workers |

2× |

−3123 |

−2023 |

702 |

1,802 |

| 3× |

−3171 |

−2070 |

88 |

1,189 |

| 4× |

−3,200 |

−2,098 |

−342 |

760 |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae |

MSM_LR |

1× |

−78,535 |

−53,125 |

−78,821 |

−53,411 |

| MSM_HR |

2× |

−24,873 |

−16,796 |

−25,039 |

−16,962 |

| 3× |

−26,197 |

−17,705 |

−26,334 |

−17,842 |

| 4× |

−26,981 |

−18,243 |

−27,099 |

−18,361 |

| Female sex workers |

2× |

−35,072 |

−23,684 |

−35,306 |

−23,918 |

| 3× |

−36,945 |

−24,968 |

−37,139 |

−25,162 |

| 4× |

−38,045 |

−25,724 |

−38,213 |

−25,892 |

| Chlamydia trachomatis |

MSM_LR |

1× |

−89,210 |

−60,244 |

−89,818 |

−60,852 |

| MSM_HR |

2× |

−28,758 |

−19,411 |

−28,978 |

−19,631 |

| 3× |

−30,273 |

−20,448 |

−30,468 |

−20,643 |

| 4× |

−31,156 |

−21,053 |

−31,334 |

−21,231 |

| Female sex workers |

2× |

−36,976 |

−24,988 |

−37,183 |

−25,195 |

| 3× |

−38,925 |

−26,321 |

−39,100 |

−26,496 |

| 4× |

−40,059 |

−27,098 |

−40,213 |

−27,252 |

| Hepatitis C virus (HCV) |

PWID_LR |

1× |

17,467 |

19,210 |

−2,765 |

−1,022 |

| PWID_HR |

2× |

7,259 |

7,790 |

−620 |

−89 |

| 3× |

6,675 |

7,237 |

−772 |

−210 |

| 4× |

6,281 |

6,861 |

−868 |

−288 |

Savings are maximised under the chronic treatment without franchise-waiver

scenario, which combines high treatment costs with lower insurer contributions to

screening. Chronic treatment costs – such as lifelong antiretroviral therapy or

HCV-related complications – substantially exceed those of acute care, enhancing

the value of prevention. In the absence of a franchise-waiver, screening costs are

partially borne by the insured, further reducing the financial burden on insurers.

Consequently, strategies that prevent high-cost infections while limiting insurer

liability for screening yield the greatest net savings.

However, it is important to note that the acute treatment with

franchise-waiver scenario represents the lowest overall cost to insurers, as outlined

in the aforementioned hierarchy of scenarios for evaluating cost savings. Interpretation

of cost-saving results should therefore be contextualised alongside the absolute

screening and treatment costs presented in tables S8 and S9 in the appendix.

Sensitivity analysis

Figure S1 demonstrates that our findings

are generally robust to variations in assumptions regarding screening uptake rate,

test positivity and onward transmission rate. Among MSM, the results remain unchanged.

For FSW, a 10% increase in the test positivity rate renders syphilis screening

cost-saving. Likewise, for PWID, a 10% increase in test positivity results in screening

becoming cost-saving for HIV under the franchise-waiver scheme.

Discussion

Our model accurately replicates the baseline incidence

of the five infections under study at the current screening uptake rate and simulates

a reduction in incidence across all key populations with increased screening. The

most substantial decline is observed for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) among

men who have sex with men (MSM)

and people who inject drugs (PWID) over time. Incorporating screening for HIV, syphilis

and hepatitis C virus (HCV) into the health insurance framework is expected to be

cost-saving. While screening has a notable impact on the incidence of Neisseria

gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis, it is not enough to offset the

relatively low treatment cost and the high cost of screening. Therefore, integrating

voluntary screening for these infections into the health insurance framework is

unlikely to be cost-saving.

Our findings support the implementation of more frequent

HIV screening for MSM and female sex workers (FSW), as well as at least biannual

screening for people who inject drugs under a franchise-waiver. Although the number

of cases prevented annually is relatively small, the associated cost savings are

significant. The importance of expanding HIV screening coverage, particularly among

vulnerable populations, has been well documented in the literature [17, 18]. Research

also emphasises the benefits of frequent annual screenings in reducing incidence

and improving viral suppression among people living with HIV, particularly within

key populations such as MSM [19, 20]. Additionally, studies underscore the need

for increased screening frequency among groups at higher risk within vulnerable

populations such as MSM [21].

Similarly, for HCV, our results support the provision

of more frequent screening for PWID, aligning with existing literature. Previous

studies have highlighted the benefits of expanded general population screening in

reducing prevalence and mitigating severe complications for individuals who were

infected with contaminated blood products or injectables prior to the discovery

of HCV [22, 23]. Since its discovery in 1989, HCV has primarily been transmitted

through injectables. As a result, targeted and comprehensive screening strategies,

combined with improved access to treatment, have been identified as crucial for

eliminating HCV in vulnerable populations such as PWID and MSM living with HIV [24–26].

Importantly, expanded screening among PWID should be implemented in tandem with

harm-reduction interventions such as needle and syringe programmes and opioid substitution

therapy as these remain the cornerstone of primary prevention efforts [33].

Our study also aligns with findings from a recent

modelling study, which showed that expanding screening from once to twice annually

among HIV-positive MSM resulted in a 63.5% reduction in syphilis incidence. In contrast,

the same increase in screening frequency among HIV-negative MSM led to a 12.8% reduction

in incidence [2]. Similarly, quarterly syphilis screening (four times a year) was

found to be the most effective strategy for reducing syphilis incidence among MSM

with a high frequency of unprotected intercourse [27].

For Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia

trachomatis, although pooled swab testing can help lower screening costs, it

would not be sufficient to make the intervention cost-saving, even with a substantial

reduction in incidence observed in our results. A more targeted strategy is needed

to identify the groups at highest risk within key populations and improve cost-effectiveness

by combining focused screening with lower-cost strategies. The evidence in the literature

on the effectiveness of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia

trachomatis screening is inconclusive. While a hospital-based screening strategy

for rectal Neisseria gonorrhoeae/Chlamydia trachomatis in MSM led

to a 43% reduction in incidence, other studies found no strong evidence that Neisseria

gonorrhoeae / Chlamydia trachomatis screening in MSM significantly impacts

disease prevalence, nor that more frequent screening is more effective than annual

screening [28, 29]. A randomised controlled trial (RCT) further showed no impact

of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis screening on incidence

among pre-exposure prophylaxis-using MSM [30]. For Chlamydia trachomatis

screening in the general population, a separate RCT found a limited impact, suggesting

that broad population-based screening may not be an effective strategy for reducing

incidence [31]. Moreover, some studies have questioned the clinical rationale for

screening Chlamydia trachomatis infections in general, citing a lack of evidence

for preventing long-term sequelae such as infertility, particular in MSM [34].

Notably, many of these studies focused either on

general populations, which would have a lower infection prevalence than the groups

in our study, or on populations with dense sexual networks, such as MSM on pre-exposure

prophylaxis. Our study excludes pre-exposure prophylaxis users from the key populations

and thus does not capture the densest segment of the MSM sexual networks. This distinction

may explain why our results show a stronger impact of screening in reducing Neisseria

gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis prevalence in MSM and FSW who

do not use pre-exposure prophylaxis in Switzerland. These two infections are more

evenly distributed in the overall general MSM and FSW populations compared to syphilis,

which is concentrated among pre-exposure prophylaxis-using and HIV-positive MSM.

Our findings highlight how cost savings from different

screening strategies vary not only by infection type and key population but also

by the structure of insurance coverage and underlying treatment cost assumptions.

A strategy that appears cost-saving under chronic treatment scenarios without a

franchise-waiver may not remain cost-saving under more conservative assumptions,

such as acute care with a franchise-waiver. This gradient underscores the importance

of clearly specifying the evaluation perspective and cost scenario when assessing

the financial implications of sexually transmitted infection screening interventions.

These distinctions are critical for informing health policy decisions and designing

financially sustainable and equitable screening programmes. In addition, while more

frequent screening leads to greater reductions in incidence, these benefits occur

at increasing cost and with diminishing returns.

Cost savings also depend on the underlying incidence

of infection within each key population. For example, HIV screening among MSM remains

cost-saving even under more conservative assumptions, such as acute care with a

franchise-waiver, whereas the same is not true for FSW. This likely reflects the

higher baseline incidence and prevalence of HIV among MSM, which increases the potential

for screening to detect and prevent more cases. Thus, the optimal frequency of screening

should be determined based on local epidemiology, available resources and programme

priorities.

Our study contributes to the growing, albeit small,

body of research evaluating the impact of sexually transmitted infection screening

on disease incidence in the Swiss context [2, 5, 6]. It is the first to examine

this relationship for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis

while considering the cost implications for insurance providers. A key strength

of our model is the use of a common Markov framework to simulate both viral and

bacterial sexually transmitted infections, while accounting for their distinct transmission

dynamics and natural histories. Additionally, we provide a comprehensive cost estimate

for screening five different sexually transmitted infections in Switzerland, as

well as the costs associated with treating both acute and chronic conditions or

complications resulting from these infections. Another strength of our approach

is the incorporation of risk-behaviour stratification within the defined key populations,

enabling a more nuanced analysis of disease dynamics between the two risk groups.

Finally, although pre-exposure prophylaxis users were excluded from the analysis,

this does not compromise the generalisability of our findings within the non–pre-exposure

prophylaxis-using MSM population. While pre-exposure prophylaxis users constitute

a small subgroup – less than 7% of the estimated MSM population in Switzerland –

with higher sexual risk behaviours and sexually transmitted infection prevalence,

they are already systematically screened through established programmes [32]. In

contrast, our analysis focuses on expanding access to screening for vulnerable populations

with limited access to structured sexually transmitted infection screening.

There are also some limitations to our analysis.

First, due to data limitations, we are unable to account for variations in disease

dynamics and behaviour within key populations, which may not accurately capture

the intragroup differences. Second, we do not consider the site of swabbing for

Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis screening, which is

an important factor, as genital infections are more likely to lead to complications

and, therefore, have higher expected treatment costs. Additionally, our assumption

that a reduction in the cost of screening, whether offered with or without a franchise-waiver,

has the same effect on screening behaviour may not hold. Offering asymptomatic screening

without a franchise-waiver through the insurance framework may be more expensive

for the test-takers, potentially leading to a lower impact on screening uptake.

Finally, we assume a linear relationship between screening frequency and its impact

on transition probabilities, due to a lack of data to inform a non-linear relationship,

where increasing screening frequency might result in diminishing returns in uptake.

Future research could focus on more specific subgroups,

particularly for infections with less evidence, such as Neisseria

gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis among HIV-positive or pre-exposure

prophylaxis-using MSM. Additionally, future modelling studies may consider the timing

of screening, as diagnostic sensitivity varies depending on the duration of infection.

Finally, since most decision-making is driven by cost-effectiveness rather than

just cost-savings, a comprehensive cost-effectiveness analysis, especially for Neisseria

gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis, considering both the costs

prevented through case prevention and the quality-of-life improvements from earlier

diagnosis and treatment, could provide stronger evidence for the economic efficiency

of screening these infections.

Conclusion

Expanding access to screening among key populations

in Switzerland can substantially reduce the incidence of HIV, HCV, syphilis, Neisseria

gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis. Our model indicates that incorporating

regular screening for HIV, HCV and, in selected contexts, syphilis into the national

health insurance framework could yield meaningful cost savings for insurers, especially

when long-term treatment costs are considered and screening is offered without a

franchise-waiver by maintaining deductible thresholds for individuals.

Although our model showed a substantial reduction

in Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis incidence with

increased screening, the high screening costs combined with relatively low treatment

costs meant these strategies were not financially viable under the scenarios evaluated.

This highlights the potential value of more targeted screening approaches, possibly

using finer risk stratifications than applied in this study, and the use of cost-saving

diagnostic methods such as pooled testing.

Data sharing statement

The data used in this study was obtained from participating

Voluntary Counselling and Testing centres (VCTs) in Switzerland (BerDa) and were

provided to the research team under strict data use agreements for the duration

of the study. The datasets were deidentified but remain the property of the individual

VCTs and were deleted from our systems following completion of the analysis, in

accordance with these agreements. As such, we are unable to share the data publicly

or upon request. Interested researchers may contact the relevant VCTs directly to

enquire about access, subject to their institutional data governance policies and

approvals. Data dictionaries and related documents are not publicly available.

Open science statement: This study is a secondary analysis of

anonymised data collected through routine sexually transmitted infection testing

and service delivery. As it does not constitute a clinical trial, registration in

a trial registry was not applicable. Although no formal protocol was prepared, a

detailed analysis plan was included in the original funding proposal and shared

with both the funders and collaborating data-providing centres. No deviations from

this analysis plan occurred.

All analytical code used in the study will be made publicly

available via GitHub prior to publication, including details of the software environment,

packages and versioning. The code will be released under an open-source licence

and linked to in the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Athos Staub for his assistance

in organising the study, for offering high-level feedback and for his continued

support with the project. We also acknowledge Barbara Jakopp and the Federal Commission

for Issues relating to Sexually Transmitted Infections, Working Group 3 for their

significant contributions to estimating the costs of screening and treatment for

different infections. We would also like to extend our thanks to Benjamin Hampel

for sharing his expertise on the clinical context of sexually transmitted

infection screening in Switzerland.

We are grateful to Claudia Scheuter and Guido Biscontin

for their guidance in refining the analytical approach and shaping the direction

of the analysis. We also thank Marcel Tanner and Hannah Tough for their high-level

guidance and feedback on the project. Finally, we are grateful to the entire EKSI

for their valuable feedback on the modelling process and results.

Finally, we extend our warmest thanks to the following

voluntary counselling and testing centres for their cooperation with data sharing:

Aids-Hilfe beider Basel, LadyCheck; Aids-Hilfe beider Basel, Checkpoint; Seges,

Sexuelle Gesundheit Aargau; Checkin Zollstrasse, Zurich; Stadtmission ZH / Isla

Victoria; Centre de santé sexuelle Fribourg; Kantonsspital St. Gallen; Unisanté;

Perspektive Thurgau; Générations Séxualités Neuchâtel; Checkpoint Luzern / S&X

Sexuelle Gesundheit Zentralschweiz; Planning Familial (La Chaux de Fonds); Checkpoint

Zürich; Test-in Zürich; Aids-Hilfe Graubünden; Centre Empreinte; Spital Thurgau;

Checkpoint Vaud; and SIPE Valais.

Harsh Vivek Harkare, MSc

Swiss Tropical and

Public Health Institute

Kreuzstrasse 2

CH-4123 Allschwil

harshvivek.harkare[at]swisstph.ch

References

1. Federal Office of Public Health. National Programme on HIV and other STIs [Internet].

2024 [cited 2025 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/strategie-und-politik/nationale-gesundheitsstrategien/nationales-programm-hiv-hep-sti-naps.html

2. Balakrishna S, Salazar-Vizcaya L, Schmidt AJ, Kachalov V, Kusejko K, Thurnheer MC,

et al.; Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS). Assessing the drivers of syphilis among men

who have sex with men in Switzerland reveals a key impact of screening frequency:

A modelling study. PLOS Comput Biol. 2021 Oct;17(10):e1009529. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009529

3. Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH). Voluntary counselling and testing [Internet].

Swiss Confederation; 2024 [cited 2025 Apr 4]. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/krankheiten/krankheiten-im-ueberblick/sexuell-uebertragbare-infektionen/freiwillige-beratung-und-testung.html

4. Schmidt AJ, Marcus U. What’s on the rise in Sexually Transmitted Infections? Lancet

Reg Health Eur. 2023 Oct;34:100764. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2023.100764

5. Schmidt AJ, Rasi M, Esson C, Christinet V, Ritzler M, Lung T, et al. The Swiss STAR

trial - an evaluation of target groups for sexually transmitted infection screening

in the sub-sample of men. Swiss Med Wkly. 2020 Dec;150(5153):w20392. doi: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2020.20392

6. Vernazza PL, Rasi M, Ritzler M, Dost F, Stoffel M, Aebi-Popp K, et al. The Swiss STAR

trial - an evaluation of target groups for sexually transmitted infection screening

in the sub-sample of women. Swiss Med Wkly. 2020 Dec;150(5153):w20393. doi: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2020.20393

7. AIDS.ch. Leitfaden Safer Sex [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 21]. Available from: https://shop.aids.ch/de/A~1911~45/2~110~Shop/Infomaterial/Schutz-vor-HIV-und-STI/Leitfaden-Safer-Sex/deu-fra

8. Dr. Gay. Testing advice [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Feb 14]. Available from: https://drgay.ch/en/safer-sex/tested-and-vaccinated/testing-advice

9. Love Life. STI tests: Important for your sexual health [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025

Feb 14]. Available from: https://lovelife.ch/de/testen

10. SwissPrepared. SwissPrepared: Pandemic preparedness in Switzerland [Internet]. 2025

[cited 2025 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.swissprepared.ch/en/

11. Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH). HIV-Test auf Initiative der Ärztin oder des

Arztes (Provider Initiated Counselling and Testing, PICT): Medizinische Empfehlungen

(BAG Bulletin 21/15) [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Feb 25]. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/dam/bag/de/dokumente/mt/p-und-p/richtlinien-empfehlungen/pict-hiv-test-auf-initiative-des-arztes.pdf.download.pdf/bu-21-15-pict-hiv.pdf

12. Weatherburn P, Hickson F, Reid DS, Marcus U, Schmidt AJ. European Men-Who-Have-Sex-With-Men

Internet Survey (EMIS-2017): design and methods. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2020;17(4):543–57.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-019-00413-0

13. Swissmedic. Swissmedic - The Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products [Internet]. 2024

[cited 2025 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.swissmedic.ch/swissmedic/de/home.html

14. Spezialitätenliste. Spezialitätenliste (SL) und Geburtsgebrechen-Spezialitätenliste

(GGSL) by the BAG/FOPH [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.spezialitätenliste.ch

15. TARMED. Tarifstruktur TARMED by the BAG/FOPH [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Feb 14].

Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/versicherungen/krankenversicherung/krankenversicherung-leistungen-tarife/Aerztliche-Leistungen-in-der-Krankenversicherung/Tarifsystem-Tarmed.html

16. Swiss Society of Infectious Diseases. SSI guidelines [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024

May 11]. Available from: https://ssi.guidelines.ch

17. Wainberg MA, Hull MW, Girard PM, Montaner JS. Achieving the 90-90-90 target: incentives

for HIV testing. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Nov;16(11):1215–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30383-8

18. UNAIDS. 90–90–90: An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic [Internet].

2014 [cited 2025 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en.pdf

19. Neilan AM, Bulteel AJ, Hosek SG, Foote JH, Freedberg KA, Landovitz RJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness

of Frequent HIV Screening Among High-risk Young Men Who Have Sex With Men in the United

States. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 Oct;73(7):e1927–35. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1061

20. Phillips AN, Cambiano V, Miners A, Lampe FC, Rodger A, Nakagawa F, et al. Potential

impact on HIV incidence of higher HIV testing rates and earlier antiretroviral therapy

initiation in MSM. AIDS. 2015 Sep;29(14):1855–62. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000767

21. DiNenno EA, Prejean J, Delaney KP, Bowles K, Martin T, Tailor A, et al. Evaluating

the Evidence for More Frequent Than Annual HIV Screening of Gay, Bisexual, and Other

Men Who Have Sex With Men in the United States: Results From a Systematic Review and

CDC Expert Consultation. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(1):3–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354917738769

22. Cramp ME, Rosenberg WM, Ryder SD, Blach S, Parkes J. Modelling the impact of improving

screening and treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection on future hepatocellular

carcinoma rates and liver-related mortality. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014 Aug;14(1):137.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-14-137

23. Coffin PO, Scott JD, Golden MR, Sullivan SD. Cost-effectiveness and population outcomes

of general population screening for hepatitis C. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 May;54(9):1259–71.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cis011

24. Durham DP, Skrip LA, Bruce RD, Vilarinho S, Elbasha EH, Galvani AP, et al. The impact

of enhanced screening and treatment on hepatitis C in the United States. Clin Infect

Dis. 2016 Feb;62(3):298–304. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ894

25. Houghton M. Discovery of the hepatitis C virus. Liver Int. 2009 Jan;29(s1 Suppl 1):82–8.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01925.x

26. Kusejko K, Salazar-Vizcaya L, Shah C, Stöckle M, Béguelin C, Schmid P, et al.; Swiss

HIV Cohort Study. Sustained Effect on Hepatitis C Elimination Among Men Who Have Sex

With Men in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study: A Systematic Re-Screening for Hepatitis C

RNA Two Years Following a Nation-Wide Elimination Program. Clin Infect Dis. 2022 Nov;75(10):1723–31.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciac273

27. Tuite AR, Fisman DN, Mishra S. Screen more or screen more often? Using mathematical

models to inform syphilis control strategies. BMC Public Health. 2013 Jun;13(1):606.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-606

28. Chesson HW, Bernstein KT, Gift TL, Marcus JL, Pipkin S, Kent CK. The cost-effectiveness

of screening men who have sex with men for rectal chlamydial and gonococcal infection

to prevent HIV Infection. Sex Transm Dis. 2013 May;40(5):366–71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318284e544

29. Tsoumanis A, Hens N, Kenyon CR. Is Screening for Chlamydia and Gonorrhea in Men Who

Have Sex With Men Associated With Reduction of the Prevalence of these Infections?

A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Sex Transm Dis. 2018 Sep;45(9):615–22.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000824

30. Vanbaelen T, Rotsaert A, Van Landeghem E, Nöstlinger C, Vuylsteke B, Platteau T, et

al. Do pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) users engaging in chemsex experience their

participation as problematic and how can they best be supported? Findings from an

online survey in Belgium. Sex Health. 2023 Oct;20(5):424–30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1071/SH23037

31. Hocking JS, Temple-Smith M, Guy R, Donovan B, Braat S, Law M, et al.; ACCEPt Consortium.

Population effectiveness of opportunistic chlamydia testing in primary care in Australia:

a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018 Oct;392(10156):1413–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31816-6

32. Aids-Hilfe Schweiz. Data on HIV and AIDS [Internet]. 2025 Jul 24 [cited 2025 Feb 14].

Available from: https://aids.ch/en/knowledge/topics/data/

33. Platt L, Minozzi S, Reed J, Vickerman P, Hagan H, French C, et al. Needle and syringe

programmes and opioid substitution therapy for preventing HCV transmission among people

who inject drugs: findings from a Cochrane Review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2018 Mar;113(3):545–63.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14012

34. Williams E, Williamson DA, Hocking JS. Frequent screening for asymptomatic chlamydia

and gonorrhoea infections in men who have sex with men: time to re-evaluate? Lancet

Infect Dis. 2023 Dec;23(12):e558–66. 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00356-0

35. Bihl F, Bruggmann P, Castro Batänjer E, Dufour JF, Lavanchy D, Müllhaupt B, et al. HCV

disease burden and population segments in Switzerland. Liver Int. 2021;41(12):2803–14.

10.1111/liv.15111

36. Bruggmann P, Blach S, Deltenre P, Fehr J, Kouyos R, Lavanchy D, et al. Hepatitis C

virus dynamics among intravenous drug users suggest that an annual treatment uptake

above 10% would eliminate the disease by 2030. Swiss Med Wkly. 2017 Nov;147(4546):w14543.

10.4414/smw.2017.14543

37. Schmidt AJ, Altpeter E. The Denominator problem: estimating the size of local populations

of men-who-have-sex-with-men and rates of HIV and other STIs in Switzerland. Sex Transm

Infect. 2019 Jun;95(4):285–91. 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053363

38. UNAIDS. Switzerland [Internet]. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2021 [cited 2024 Mar 5]. Available

from: https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/switzerland

39. EMIS Project. The European Men-Who-Have-Sex-With-Men Internet Survey [Internet]. 2024 Jul 20

[cited 2025 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.emis-project.eu

40. Schmidt AJ, Rasi M, Esson C, Christinet V, Ritzler M, Lung T, et al. The Swiss STAR

trial - an evaluation of target groups for sexually transmitted infection screening

in the sub-sample of men. Swiss Med Wkly. 2020 Dec;150(5153):w20392. doi: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2020.20392

41. Bigler D, Surial B, Hauser CV, Konrad T, Furrer H, Rauch A, et al. Prevalence of STIs

and people’s satisfaction in a general population STI testing site in Bern, Switzerland.

Sex Transm Infect. 2023 Jun;99(4):268–71. 10.1136/sextrans-2022-055596

42. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Ending an epidemic: HCV treatment

for people who inject drugs (PWID) [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Feb 14]. Available

from: https://www.unodc.org/documents/commissions/CND/2019/Contributions/Civil_Society/2018_IAS_Brief_Ending_an_epidemic_HCV_treatment_for_PWID.pdf

43. Nevin RL, Shuping EE, Frick KD, Gaydos JC, Gaydos CA. Cost and effectiveness of Chlamydia

screening among male military recruits: markov modeling of complications averted through

notification of prior female partners. Sex Transm Dis. 2008 Aug;35(8):705–13. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31816d1f55

44. Park IU, Tran A, Pereira L, Fakile Y. Sensitivity and specificity of treponemal-specific

tests for the diagnosis of syphilis. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Jun;71 Suppl 1:S13–20.

10.1093/cid/ciaa349

54. Vetter BN, Ongarello S, Tyshkovskiy A, Alkhazashvili M, Chitadze N, Choun K, et al. Sensitivity

and specificity of rapid hepatitis C antibody assays in freshly collected whole blood,

plasma and serum samples: A multicentre prospective study. PLoS One. 2020 Dec;15(12):e0243040.

10.1371/journal.pone.0243040

46. Kohler P, Schmidt AJ, Cavassini M, Furrer H, Calmy A, Battegay M, et al.; Swiss HIV

Cohort Study. The HIV care cascade in Switzerland: reaching the UNAIDS/WHO targets

for patients diagnosed with HIV. AIDS. 2015 Nov;29(18):2509–15. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000878

47. Wandeler G, Dufour JF, Bruggmann P, Rauch A. Hepatitis C: a changing epidemic. Swiss

Med Wkly. 2015 Feb;145(506):w14093. 10.4414/smw.2015.14093

48. Garnett GP, Aral SO, Hoyle DV, Cates W Jr, Anderson RM. The natural history of syphilis.

Implications for the transmission dynamics and control of infection. Sex Transm Dis.

1997 Apr;24(4):185–200. 10.1097/00007435-199704000-00002

49. Garnett GP, Mertz KJ, Finelli L, Levine WC, St Louis ME. The transmission dynamics

of gonorrhoea: modelling the reported behaviour of infected patients from Newark,

New Jersey. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1999 Apr;354(1384):787–97. 10.1098/rstb.1999.0432 doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1999.0431

50. Paltiel AD, Weinstein MC, Kimmel AD, Seage GR 3rd, Losina E, Zhang H, et al. Expanded

screening for HIV in the United States—an analysis of cost-effectiveness. N Engl J

Med. 2005 Feb;352(6):586–95. 10.1056/NEJMsa042088

51. Potterat JJ, Zimmerman-Rogers H, Muth SQ, Rothenberg RB, Green DL, Taylor JE, et al. Chlamydia

transmission: concurrency, reproduction number, and the epidemic trajectory. Am J

Epidemiol. 1999 Dec;150(12):1331–9. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009965

52. Cui M, Qi H, Zhang T, Wang S, Zhang X, Cao X, et al. Symptomatic HIV infection and

in-hospital outcomes for patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous

coronary intervention from national inpatient sample. Sci Rep. 2024 Apr;14(1):9832.

10.1038/s41598-024-59920-9

53. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Chlamydia infection [Internet].

2024 Aug 5 [cited 2025 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/chlamydia-infection

54. Maheshwari A, Ray S, Thuluvath PJ. Acute hepatitis C. Lancet. 2008 Jul;372(9635):321–32.

10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61116-2

55. Martín-Sánchez M, Fairley CK, Ong JJ, Maddaford K, Chen MY, Williamson DA, et al. Clinical

presentation of asymptomatic and symptomatic women who tested positive for genital

gonorrhoea at a sexual health service in Melbourne, Australia. Epidemiol Infect. 2020 Sep;148:e240.

10.1017/S0950268820002265

56. Grebely J, Matthews S, Causer LM, Feld JJ, Cunningham P, Dore GJ, et al. We have reached

single-visit testing, diagnosis, and treatment for hepatitis C infection, now what? Expert

Rev Mol Diagn. 2024 Mar;24(3):177–91. 10.1080/14737159.2023.2292645

Appendix

The appendix is available in the PDF version of the manuscript at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4581.