Figure 1Polyp occurrence in biallelic NTHL1 carriers.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4554

MUTYH-associated polyposis

Nth like DNA glycosylase 1

Pathogenic variants in DNA repair genes have been associated with a greatly increased risk for colon cancer, e.g. tumour predispositions such as MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP) and Lynch syndrome. In 2015, Weren et al. reported seven individuals from three different families with colon polyposis and colorectal carcinoma which could be attributed to pathogenic germline variants in the base excision repair (BER) gene NTHL1 (MANE Select: NM_002528.7) [1]. NTHL1-associated tumour syndrome (NATS), initially also referred to as NTHL1-associated polyposis (NAP), is an autosomal recessive tumour predisposition with a reported phenotype of adenomatous polyposis coli, colorectal cancer and extracolonic manifestations such as breast cancer, endometrial cancer, urothelial cancer and brain tumours [2]. The estimated frequency of NTHL1-associated tumour syndrome in Europe is about 1:114,700, which is approximately five times less frequent than the autosomal recessive MUTYH-associated polyposis, which encodes for another component of the base excision repair system [3].

NTHL1, located on chromosome 16p13.3 next to the tuberous sclerosis 2 (TSC2) gene, consists of six protein-coding exons and encodes a bifunctional DNA N-glycosylase in the base excision repair system. It removes DNA bases damaged by alkylation, deamination or oxidation [4, 5].

Defects in DNA repair pathways such as base excision repair lead to an accumulation of somatic alterations and thus an increased cancer risk in susceptible tissues [6]. The glycosylases in base excision repair, monofunctional and bifunctional alike, recognise the impaired DNA base and remove it. The resulting DNA gap is then repaired by the short-patch or long-patch repair pathway [7]. The glycosylase NTHL1 is mostly responsible for the removal of oxidised pyrimidines such as thymine glycol, formamidopyrimidine lesions (FapyG), 5-hydroxycytosine and 5-hydroxyuracil [4]. Accordingly, NTHL1 deficiency has been found to result in a distinct mutational signature, signature 30 of the COSMIC database, characterised by C>T transitions at non-CpG sites and present across tumours from different organs of biallelic germline NTHL1 carriers [8]. The identification of a Swiss NTHL1 patient in our clinic prompted us to comprehensively gather published genotype and phenotype data on mono- and biallelic NTHL1 carriers reported thus far, and to perform a genotype-phenotype analysis. The goal was to further delineate the clinical phenotype and to review current screening recommendations for carriers of the NTHL1-associated tumour syndrome.

A 44-year-old man underwent colonoscopy as part of an investigation of blood in the stool. Over one hundred polyps were found in the entire colon, as well as a 3 cm wide, moderately differentiated, microsatellite-stable adenocarcinoma in the ascending colon (pT2 pN0 (0/35) L0 V0 Pn0 G2). A right-sided hemicolectomy was performed, showing approximately 15–20 polyps consisting mainly of tubular and tubulovillous adenomas: 1 tubulovillous low-grade adenoma in the cecum (3.5 cm), 8 low-grade tubular adenomas (max. 0.9 cm), a hyperplastic polyp (0.8 cm), as well as approximately 10 histologically uncharacterised polyps. Additionally, 2 serrated lesions of the appendix were identified.

Half a year later, the patient underwent a subtotal colectomy after renewed lower gastrointestinal bleeding and due to the inability to remove the remaining polyps endoscopically because of unstoppable bleeding caused by newly discovered Von Willebrand disease. Among the over 100 polyps found, a high-grade differentiated 0.4 cm wide tubular adenocarcinoma was discovered in the descending colon (pT1 pN0 (0/42) L0 V0 Pn0 G1). The histologically examined polyps consisted of a tubulovillous adenoma with high-grade epithelial dysplasia and multiple tubular low-grade dysplastic adenomas. Additionally, an unspecified number of hyperplastic polyps were observed.

A comprehensive gene panel analysis of 13 polyposis genes (APC, BMPR1A, GREM1, MSH3, MUTYH, NTHL1, POLD1, POLE, PTEN, RNF43, RPS20, SMAD4, STK11) identified the homozygous NTHL1 variant c.244C>T, p.(Gln90Ter). This variant, formerly known as c.268C>T, p.(Gln90Ter) leads to a premature stop codon undergoing nonsense-mediated decay [1, 9].

Except for a paternal aunt, who suffered from an alleged brain tumour at age 45, family history was unremarkable. His healthy, non-consanguineous parents and his two brothers had inconspicuous colonoscopies.

To identify all reported NTHL1 carriers, bi- and monoallelic alike, a literature search covering all published articles from 2015 to 2022 was conducted. PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library were used to gather the pertinent data, as well as additional references listed in the relevant articles. First, an open search without any criteria except the publishing date revealed 253 eligible papers. Second, the search terms were restricted to medical and case reports, to omit merely functional NTHL1 data. More information on the exact search terms is given in appendix table S1. Finally, 30 articles provided the necessary clinical information, such as sex, gene variant, allelic status, clinical manifestations (polyps, colorectal cancer, tumour spectrum, age at onset) and family history. Together with our newly identified Swiss NTHL1 patient, data on a total of 244 individuals from 200 different families were gathered.

To conduct genotype-phenotype analyses, only patients harbouring at least one pathogenic variant (PV) in NTHL1, namely class 4 (likely pathogenic) or class 5 (pathogenic), were included. This led to the exclusion of 14 individuals whose NTHL1 variant was reported as either benign, likely benign or as a variant of unknown significance (VUS) (classes 1, 2, 3). Furthermore, 14 additional patients with variants in genes other than NTHL1 were excluded. Our final cohort thus consisted of 216 individuals from 200 families, 59 biallelic and 157 monoallelic NTHL1 carriers. Appendix table S4 depicts the complete dataset from all 216 individuals.

Polyp numbers were grouped using the following system: “few”, “some” for 1–4 polyps; “multiple”, “numerous”, “several”, “many” for 5–99 polyps; and “massive”, “diffuse”, “carpeted”, “lots” for ≥100 polyps [10].

Statistically, the characteristics of the phenotype and the variant status were compared using the Fisher’s exact and chi-squared test for non-parametric variables. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Stat View v.4.5 (Abacus concepts) and Microsoft Excel 2021 were used to perform the calculations mentioned above.

Except for polyps, only malignant tumours were included in the analysis. The benign tumours are listed in table S4.

A total of 216 individuals with at least one pathogenic variant in the NTHL1 gene were identified, encompassing 59 (27.3%) biallelic carriers, 39 homozygous and 20 compound heterozygous, and 157 monoallelic carriers (72.7%). In contrast to the balanced female-male ratio in biallelic carriers (30:29), females were statistically significantly overrepresented in the monoallelic carrier group (117:33; p = 0.0001).

Although 17 different pathogenic loss-of-function NTHL1 germline variants have been reported to date, c.244C>T p.(Gln90Ter) – formerly known as c.268C>T, p.(Gln90Ter) – was the most frequent in our literature search (81.5% or 176/216) [1, 11]. This nonsense variant was presented at least once in 52 (88.1%)of biallelic and in 125 (79%) of monoallelic carriers (table 1). Furthermore, the c.244C>T p.(Gln90Ter) variant contributed to 76% of all pathogenic mutations found in this cohort (209/275). Except for a (1/59) homozygous NTHL1 carrier harbouring a biallelic splice variant, all other biallelic carriers carried pathogenic variants which are predicted to result in an immediate stop codon. Detailed information on the NTHL1 variants is depicted in table S4.

Table 1Sex distribution and frequency of NTHL1 PV p.Gln90Ter in bi- and monoallelic NTHL1 carriers.

| Distribution | Total n (% of total in category) | Biallelic | |

| Homozygous n (% of biallelic) | Compound heterozygous n (% of biallelic) | ||

| Total | 59 (27.3) | 39 (66.1) | 20 (33.9) |

| Female | 30 (50.8) | 18 (46.2) | 12 (40) |

| Male | 29 (49.2) | 21 (53.8) | 8 (60) |

| NTHL1 PV p.Gln90Ter | 52 (88.1) | 33 (84.6) | 19 (95) |

PV: pathogenic variant.

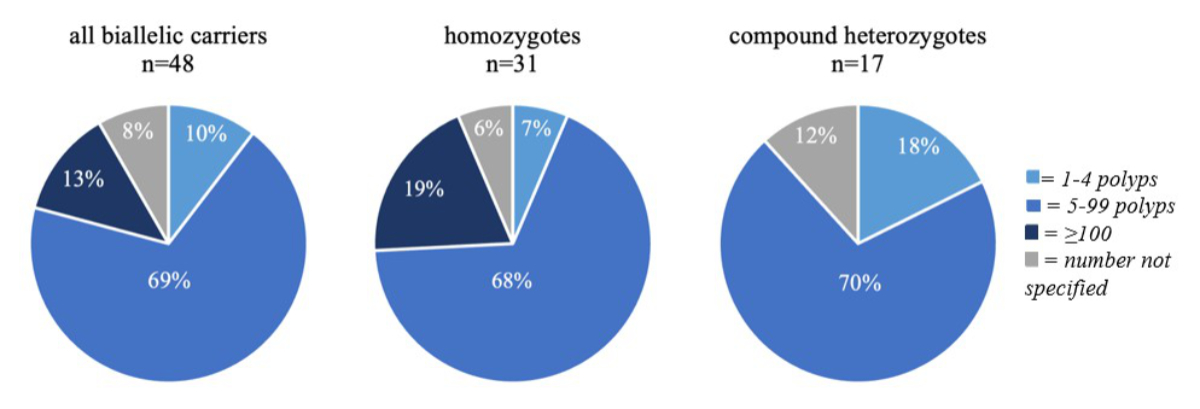

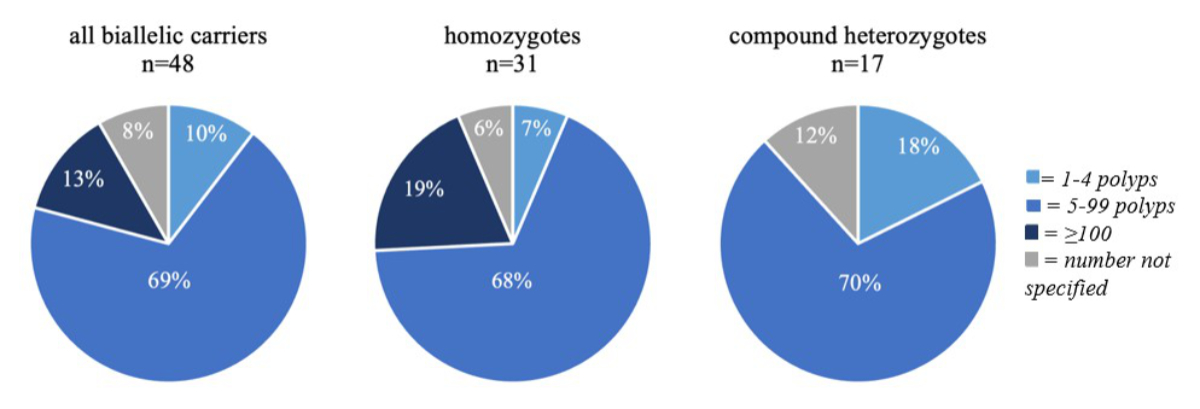

Among biallelic carriers, 52 (88.1%) displayed either colon polyps or colorectal carcinomas (CRC) or both, 2 (3.4%) had an inconspicuous colonoscopy and in 5 (8.5%) no information was given (table 2). Colonic polyps were present in 48 biallelic carriers (81.4%), in 79.5% of homozygotes and 85% of compound heterozygotes, with most individuals (70%) displaying between 5 and 99 polyps, corresponding to an attenuated polyposis phenotype. Another 13% presented with a classical polyposis phenotype (appendix table S2). Interestingly, although not reaching statistical significance (p = 0.0766), patients with more than 100 polyps (classical polyposis) were only observed in the homozygous group (6/31; 19%), but not among the compound heterozygotes (0/17) (figure 1).

Figure 1Polyp occurrence in biallelic NTHL1 carriers.

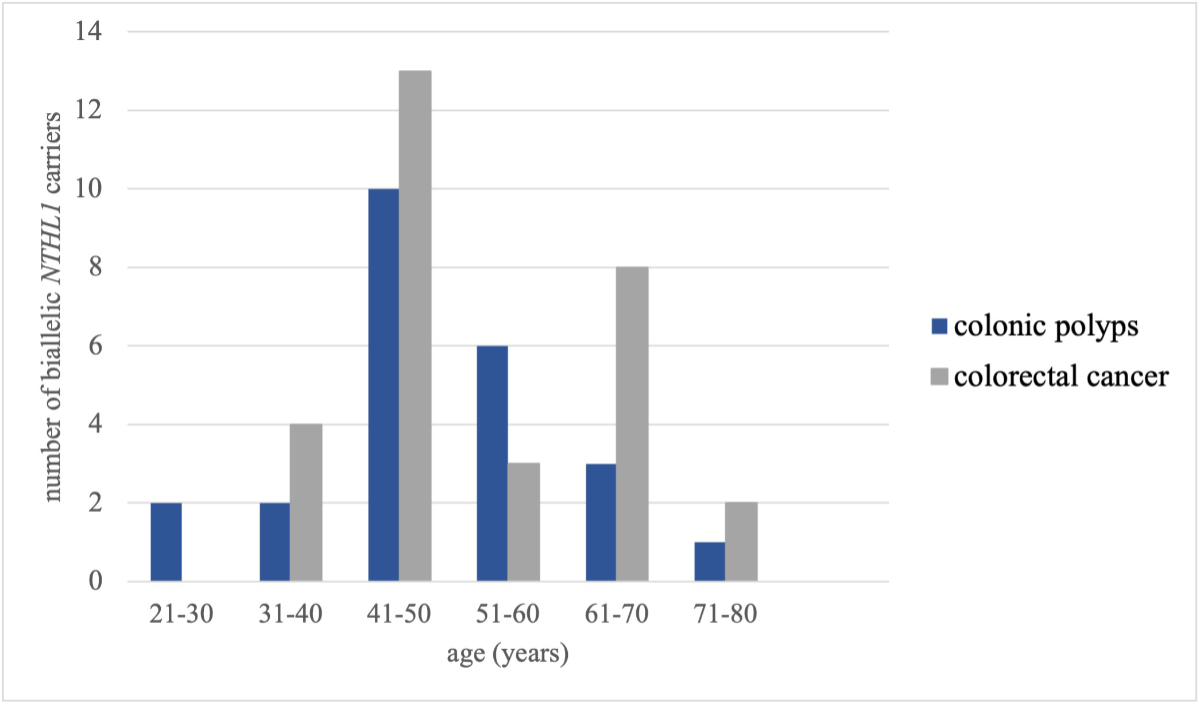

Colorectal carcinoma was reported in 30 (50.8%) patients of the biallelic carrier group; 46.2% of homozygous and 60% of compound heterozygous carriers had developed at least one colorectal carcinoma. Slightly more individuals were diagnosed with colorectal carcinoma before the age of 50 (53.3%). The median age at diagnosis for colorectal carcinoma (49 years, interquartile range [IQR]: 21) was similar to the median age for polyps (48 years, IQR: 14). The age distribution for polyps and colorectal carcinoma is depicted in figure 2.

Figure 2Age at diagnosis of colon polyps and colorectal cancer in biallelic NTHL1 carriers.

Extracolonic malignant tumours occurred in 33 (55.9%; 10 M + 23 F) biallelic carriers, in 56.4% of homozygous and 55% of compound heterozygous individuals (table 2). At 53.3% (16 of 30 female carriers), breast cancer constituted the most frequently reported extracolonic cancer manifestation in women, whereas squamous cell cancer was the most frequent one in male carriers (3/29). More detailed information is depicted in table S4. Interestingly, compound heterozygous biallelic females were diagnosed with breast cancer twice as often (75%; 9/12) as homozygous biallelic females (38.9%; 7/18), albeit not statistically significantly (p = 0.0717) (table 2). The median age at diagnosis of breast cancer was 47 years (IQR: 14.5), with an age range of 36 to 63 years. Skin cancer was reported in 13 (22.0%) patients and at a median age at diagnosis of 49 years (IQR: 21). At 61.5% (8 of 13 biallelic carriers), basal cell carcinoma was the most frequent type of skin cancer reported, occurring at a median age at diagnosis of 47.5 years (IQR: 18.5). Endometrial cancer was observed in 16.7% (5/30) of female biallelic carriers (22% [4/18] of homozygotes and 8.3% [1/12] of compound heterozygotes; p = 0.6221) and at a median age at diagnosis of 57 years (IQR: 10.5) (table 5). Finally, bladder cancer was reported in 5 (8.5%) biallelic carriers (10.3% [4/39] of NTHL1 homozygotes and 5% [1/20] of compound heterozygotes) at a median age of 52 years (IQR: 5.0). The remainder of the reported malignancies (28.8% of biallelic carriers) are listed in table S4.

Table 2Polyp and cancer occurrence in 59 biallelic NTHL1 carriers.

| Manifestation | All NTHL1 biallelic carriers, n = 59 | Homozygotes, n = 39 | Compound, heterozygotes n = 20 | p-value* | ||

| Colon manifestations: polyps and/or CRC (%) | 52 (88.1) | 33 (84.6) | 19 (95) | 0.4045 | ||

| Polyps (%) | 48 (81.4) | 31 (79.5) | 17 (85) | 0.7337 | ||

| Number (%) | 1–5 | 5 (10) | 2 (7) | 3 (18) | ||

| 5–99 | 33 (69) | 21 (68) | 12 (70) | |||

| ≥100 | 6 (13) | 6 (19) | 0 | |||

| Not specified | 4 (8) | 2 (6) | 2 (12) | |||

| Age at diagnosis, in years | Median (IQR) | 48 (14.0) | 48 (12.3) | 44 (20.8) | ||

| Range | 25–72 | 25–72 | 37–63 | |||

| Colorectal cancer (%) | 30 (50.8) | 18 (46.2) | 12 (60) | 0.4118 | ||

| Age at diagnosis, in years | Median (IQR) | 49 (21.0) | 48 (21.3) | 51 (18.5) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 51.9 (12.2) | 51.5 (13) | 52.5 (11.5) | |||

| Range | 31–73 | 31–72 | 37–73 | |||

| Extracolonic cancers** | 33 (55.9) | 22 (56.4) | 11 (55) | >0.999 | ||

| Breast cancer (%)*** | 16 (53.3) | 7 (38.9) | 9 (75) | 0.0717 | ||

| Age at diagnosis, in years | Median (IQR) | 47 (14.5) | 47 (2.5) | 47 (18.3) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 48.1 (8.7) | 46.1 (5.9) | 49.6 (10.5) | |||

| Range | 36–63 | 36–56 | 36–63 | |||

| Skin cancer (%) | 13 (22.0) | 7 (17.9) | 6 (30) | 0.3316 | ||

| Age at diagnosis, in years | Median (IQR) | 49 (21.0) | 50 (23.0) | 49 (14.0) | ||

| Range | 24–68 | 24–68 | 39–63 | |||

| Endometrial cancer (%)*** | 5 (16.7) | 4 (22.2) | 1 (8.3) | 0.6221 | ||

| Age at diagnosis, in years | Median (IQR) | 57 (10.5) | 57 (15.8) | 57 (0.0) | ||

| Range | 53–74 | 53–74 | 57–57 | |||

| Bladder cancer (%) | 5 (8.5) | 4 (10.3) | 1 (5) | 0.6532 | ||

| Age at diagnosis, in years | Median (IQR) | 52 (5.0) | 54.5 (9.5) | 47 (0.0) | ||

| Range | 47–66 | 52–66 | 47–47 | |||

| Other cancers (%)**** | 17 (28.8) | 13 (33.3) | 4 (20) | 0.3698 | ||

| Age at diagnosis, in years | Median (IQR) | 58 (15.5) | 56.5 (24.0) | 58 (5.0) | ||

| Range | 27–70 | 27–70 | 54–62 | |||

* p-value calculated for tumour occurrence in homozygous vs compound heterozygous carriers.

** Further information on all reported extracolonic cancers is shown in appendix figure S2.

*** Number of female biallelic NTHL1 carriers: total = 30, homozygous = 18, compound heterozygous = 12.

**** A detailed list of all reported carcinomas can be found in appendix table S4.

The 157 monoallelic NTHL1 carriers consisted of two subgroups: 22 had been identified through carrier testing because of an affected biallelic relative, whereas 135 individuals were index patients, who were tested because of their phenotype (appendix table S3).

Looking at the subgroup of monoallelic carriers identified through carrier testing, 13.6% (3/22) presented with colon polyps: two of them had fewer than 5 polyps, while no further details were provided for the third individual. No colorectal carcinomas were observed in this subgroup. Two had an inconspicuous colonoscopy. Unfortunately, no data were provided as to whether the remaining 17 had had a colonoscopy or not. Four of the patients (18.2% or 4/22) presented with extracolonic cancers, as follows: renal cancer at age 61 and bladder cancer at age 64; ovarian cancer at age 58; thyroid cancer at age 68; and pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma at age 58 with a smoking history of 67.5 pack-years.

Examining the subgroup of 135 monoallelic carrier index patients, 31.1% (42/135) presented with either colon polyps and/or colorectal carcinoma (table S3). Polyps were present in 21 (15.6%) individuals, the majority (66.7%) reported as having between 5 and 99 polyps. None of the monoallelic carriers in this subgroup presented with a classical polyposis phenotype. Colorectal carcinoma was reported in 28 (20.7%) of monoallelic carriers. The median age at diagnosis for polyps and for colorectal carcinoma was 55 years (IQR for polyps: 12.0, IQR for colorectal carcinoma: 19.3). Extracolonic cancers in this subgroup were reported in 94 patients (69.6%; 13 M + 80 F; one patient's sex unassigned). These malignancies consisted for the most part of breast cancer patients with 56 of the 104 (53.8%) female monoallelic individuals having developed breast cancer. The median age at diagnosis of breast cancer was 51 years (IQR: 23; range: 24–84). Prostate cancer was reported in 25% (6/24) of male monoallelic individuals. Ovarian cancer was found in 10.6% (11/104) and uterine or endometrial cancer in 8.7% (9/104) of female monoallelic NTHL1 carriers (table S3). Further information on extracolonic malignancies in monoallelic NTHL1 carriers is given in table S4.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the clinical manifestations and genotype-phenotype correlations in 216 NTHL1 carriers. It corroborates previous findings, namely that biallelic NTHL1 carriers are at high risk of adenomatous polyposis (81.4%) and consequently colorectal cancer (50.8%) as well as of certain extracolonic malignancies (55.9%) [12]. 70% of the biallelic individuals showed an attenuated polyposis coli phenotype (5–99 polyps), similar to MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP), where about 76% of biallelic carriers have fewer than 100 colon polyps [13]. Interestingly, though not statistically significant, we found that in the compound heterozygous group (n = 20), nobody was actually presenting with a classical polyposis phenotype (>100 polyps), in contrast to 19% (6/31) of biallelic individuals homozygous for the NTHL1 founder variant p.Gln90Ter. It is therefore conceivable that certain NTHL1 variants are associated with a less severe phenotype, i.e. an attenuated polyposis phenotype. Larger, ideally prospective NTHL1 patient cohorts will be necessary to further substantiate this observation.

The median age at diagnosis of colorectal cancer was 49 years, which is almost 20 years earlier than in the general population (USA: 66 years in men and 69 years in women; Switzerland: 71 years in men and 73 years in women) [14, 15]. Therefore, early colorectal cancer screening measures are essential in biallelic NTHL1 carriers. Considering that the earliest colorectal carcinoma diagnosis in our cohort was 31 years (and colon polyposis detected at age 25), the proposal of Grolleman et al. to start screening at age 18–20 with a surveillance interval of 2 years, depending on the polyp burden, appears appropriate [8].

Breast cancer represented the most frequent extracolonic cancer manifestation in female biallelic carriers (53.3%; 16/30). At 47 years, the median age at diagnosis was also considerably earlier than in the general population (USA: 62 years; Switzerland: 64.2 years) [15, 16]. Since the earliest breast cancer in our cohort was diagnosed at age 36, our findings support the recommendation by Kuiper et al. to start annual breast cancer surveillance at age 30 [9]. Moreover, NTHL1 should be considered as a possible cause of early breast cancer in females with inconspicuous results in traditional hereditary breast and ovarian cancer genes such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 [17].

The median age at diagnosis of endometrial cancer, reported in 16.7% of biallelic carriers, was 57 years with an age range from 53 to 74 years. This observation rather argues against the screening suggestion from Kuiper et al., who recommended starting with transvaginal ultrasounds at age 40 (and at an interval of two years) [9]. Based on our findings, surveillance starting around age 45–50 would appear more appropriate, unless the family history suggests otherwise. It should, however, be emphasised that, with only five reported cases of endometrial cancer in biallelic carriers, the data remain too limited to support strong, evidence-based recommendations.

To further assess and substantiate cancer risks for extracolonic malignancies in biallelic NTHL1 carriers, more data will clearly be needed. Intriguingly, the NTHL1-associated tumour syndrome cancer spectrum appears to be largely similar to the one reported in MUTYH-associated polyposis. Both carry an increased risk of attenuated adenomatous polyposis of the colon and colorectal carcinoma. However, extracolonic cancer seems to occur more frequently in NTHL1-associated tumour syndrome than in MUTYH-associated polyposis, even though MUTYH, an adenine DNA glycosylase, is part of the same DNA repair pathway. Vogt at al. observed in their cohort (276 biallelic MUTYH carriers) a 13% occurrence of extracolonic malignant cancers compared to 55.9% in our NTHL1 biallelic carrier cohort. Breast (7% vs 53.3%), skin (5% vs 22%), endometrial (1.7% vs 16.7%) and bladder cancer (1.5% vs 8.5%) were found to be the most frequent tumour manifestations, in addition to ovarian cancer (2.5%) observed in their MUTYH cohort [3, 19]. The risk of gastric cancer appears to be low in both NTHL1-associated tumour syndrome and MUTYH-associated polyposis: no biallelic carriers in our cohort and only 1% of MUTYH patients presented with stomach cancer. Similarly to MUTYH-associated polyposis patients (4%), 3.4% (2/59) of biallelic NTHL1 patients developed cancer of the small intestine [13].

The possible phenotypic impact of monoallelic NTHL1 variants on cancer development remains unclear. Current data suggest that NTHL1 heterozygotes are not at increased risk of colon polyposis or colorectal cancer, thus no specific surveillance is thought to be necessary at present [20, 21]. With regard to breast cancer, however, Li et al. suspect that a low-risk effect in monoallelic carriers might be possible [16]. The high breast cancer occurrence in our literature search (47.9%), however, does not necessarily support this statement. While the female-to-male ratio was balanced among biallelic NTHL1 carriers, monoallelic females were statistically significantly overrepresented (F:M = 117:33). It is likely that this imbalance is due to ascertainment bias since some of the larger studies exclusively focused on genetic testing of female breast cancer patients contributing 73 (62.4%) of monoallelic NTHL1 females [16, 22].

Similarly, the observed variety of other malignancies in NTHL1 heterozygotes may be largely the result of ascertainment error or chance, reflecting differences in environmental exposures, lifestyle and familial differences in individual genetic makeup. Therefore, surveillance measures other than those recommended for the general population do not appear to be justified for monoallelic carriers at this time.

In conclusion, biallelic NTHL1 carriers are at high risk of adenomatous polyposis coli and different malignancies, in particular colorectal and breast cancer before age 50. Timely surveillance measures are important for early cancer detection, treatment and prognosis. International collaborative studies, ideally performed in a prospective manner, are needed to further delineate cancer risks and timely surveillance measures in patients with NTHL1-associated tumour syndrome.

All supporting and used data can be found in the manuscript and the supplementary files.

We would like to thank the patient for participating in this project and the reviewers for their insightful comments.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript was disclosed.

1. Weren RD, Ligtenberg MJ, Kets CM, de Voer RM, Verwiel ET, Spruijt L, et al. A germline homozygous mutation in the base-excision repair gene NTHL1 causes adenomatous polyposis and colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2015 Jun;47(6):668–71.

2. Boulouard F, Kasper E, Buisine MP, Lienard G, Vasseur S, Manase S, et al. Further delineation of the NTHL1 associated syndrome: A report from the French Oncogenetic Consortium. Clin Genet. 2021 May;99(5):662–72.

3. Weren RD, Ligtenberg MJ, Geurts van Kessel A, De Voer RM, Hoogerbrugge N, Kuiper RP. NTHL1 and MUTYH polyposis syndromes: two sides of the same coin? J Pathol. 2018 Feb;244(2):135–42.

4. Krokan HE, Bjørås M. Base excision repair. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013 Apr;5(4):a012583.

5. Imai K, Sarker AH, Akiyama K, Ikeda S, Yao M, Tsutsui K, et al. Genomic structure and sequence of a human homologue (NTHL1/NTH1) of Escherichia coli endonuclease III with those of the adjacent parts of TSC2 and SLC9A3R2 genes. Gene. 1998 Nov;222(2):287–95. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00485-5

6. Das L, Quintana VG, Sweasy JB. NTHL1 in genomic integrity, aging and cancer. DNA Repair (Amst). 2020 Sep;93:102920.

7. Wallace SS, Murphy DL, Sweasy JB. Base excision repair and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2012 Dec;327(1-2):73–89.

8. Grolleman JE, de Voer RM, Elsayed FA, Nielsen M, Weren RD, Palles C, et al. Mutational Signature Analysis Reveals NTHL1 Deficiency to Cause a Multi-tumor Phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2019 Feb;35(2):256–266.e5.

9. Kuiper RP, Nielsen M, De Voer R, Hoogerbrugge N. NTHL1 Tumor Syndrome. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 2020. pp. 1993–2024. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555473/

10. Blatter R, Tschupp B, Aretz S, Bernstein I, Colas C, Evans DG, et al. Disease expression in juvenile polyposis syndrome: a retrospective survey on a cohort of 221 European patients and comparison with a literature-derived cohort of 473 SMAD4/BMPR1A pathogenic variant carriers. Genet Med. 2020 Sep;22(9):1524–32.

11. Stenson PD, Mort M, Ball EV, Chapman M, Evans K, Azevedo L, et al. The Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD®): optimizing its use in a clinical diagnostic or research setting. Hum Genet. 2020 Oct;139(10):1197–207.

12. Beck SH, Jelsig AM, Yassin HM, Lindberg LJ, Wadt KA, Karstensen JG. Intestinal and extraintestinal neoplasms in patients with NTHL1 tumor syndrome: a systematic review. Fam Cancer. 2022 Oct;21(4):453–62.

13. Nielsen M, Infante E, Brand R. MUTYH Polyposis. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 2021. pp. 1993–2024. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK107219/

14. American Cancer Society A. Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2020-2022. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2020. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures-2020-2022.pdf

15. Bundesamt für Statistik / Nationale Krebsregistrierungsstelle. Krebs, Neuerkrankungen und Sterbefälle: Anzahl, Raten, Medianalter und Risiko pro Krebsart 2016-2020 [Internet]. 12.12.2023. Available from: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/rm/home.assetdetail.29145337.html

16. Li N, Zethoven M, McInerny S, Devereux L, Huang YK, Thio N, et al. Evaluation of the association of heterozygous germline variants in NTHL1 with breast cancer predisposition: an international multi-center study of 47,180 subjects. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2021 May;7(1):52.

17. Macklin-Mantia SK, Clift KE, Maimone S, Hodge DO, Riegert-Johnson D, Hines SL. Patient uptake of updated genetic testing following uninformative BRCA1 and BRCA2 results. J Genet Couns. 2023 Jun;32(3):598–606. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jgc4.1665

18. Onkologie L. (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF): S3-Leitlinie Endometriumkarzinom, Langversion 3.0, 2024, AWMF- Registernummer: 032-034OL. Available from: https://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/endometriumkarzinom/

19. Vogt S, Jones N, Christian D, Engel C, Nielsen M, Kaufmann A, et al. Expanded Extracolonic Tumor Spectrum in MUTYH-Associated Polyposis. Gastroenterology. 2009 Dec;137(6):1976-1985.e1-10. DOI: .

20. Belhadj S, Mur P, Navarro M, González S, Moreno V, Capellá G, et al. Delineating the Phenotypic Spectrum of the NTHL1-Associated Polyposis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Mar;15(3):461–2.

21. Elsayed FA, Grolleman JE, Ragunathan A, Buchanan DD, van Wezel T, de Voer RM, et al.; NTHL1 study group. Monoallelic NTHL1 Loss-of-Function Variants and Risk of Polyposis and Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020 Dec;159(6):2241–2243.e6.

22. Kumpula T, Tervasmäki A, Mantere T, Koivuluoma S, Huilaja L, Tasanen K, et al. Evaluating the role of NTHL1 p.Q90* allele in inherited breast cancer predisposition. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2020 Nov;8(11):e1493.

The appendix is available in the pdf version of the article at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4554.