Figure 1Patient selection chart.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4490

First-episode psychosis (FEP) can arise from various aetiologies, underscoring the need for an initial comprehensive assessment to identify potentially treatable underlying causes [1]. For instance, approximately 6% of FEP patients exhibit neurological findings that necessitate further assessment, including imaging techniques [2]. Furthermore, in 51% of cases, a drug urine test indicates either acute or chronic cannabis use [3] and cannabis and other substances can lead to exacerbation of schizophrenia spectrum disorders or can induce substance-induced psychosis itself.

All current guidelines emphasise the importance of a comprehensive assessment of FEP patients, yet they differ significantly in their recommendations. Specifically, the S3 guidelines of the DGPPN (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde e.V. / German Society for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics) for schizophrenia recommend detailed patient evaluation including physical and neurological examinations, blood tests, drug screening and structural imaging [4]. On the other hand, the guidelines of the British NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) propose a more selective approach [5]. They suggest conducting imaging tests, such as MRI, only when organic causes are suspected, in cases with acute onset or when delirium is present [6]. In contrast, the guidelines of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) recommend MRI scanning in the initial assessment as well [7, 8].

This disparity between different guidelines underscores the varied opinions among experts concerning the clinical utility and cost-effectiveness of different diagnostic procedures for FEP patients. While abnormal findings on brain MRIs are common in FEP [2], their clinical relevance varies, leading to uncertainty in clinical practice. For example, a recent study concluded that individuals with FEP have higher rates of abnormal findings on brain MRIs [9]. However, only in a small fraction of cases were these abnormalities clinically relevant, and in even fewer instances did they lead to adjustments in treatment strategies [2]. Moreover, these rates also varied across the investigated studies [8]. This likely explains the divergent conclusions in cost-effectiveness analyses regarding the recommendation to conduct a brain MRI for all patients with a FEP [4] or only for those with additional neurological findings [5].

Despite the growing body of research, particularly concerning the role of MRI [8], the evidence supporting the utility of additional procedures like EEG [10] or lumbar puncture [11] remains sparse. As a result, the recommendations in the aforementioned guidelines mostly rely on expert consensus such as in the DGPPN S3 guidelines [4] while most pharmacological recommendations are based on higher grades of evidence. This lack of robust evidence leaves considerable uncertainty in clinical practice. Consequently, the clinical pathways for FEP patients may differ significantly, depending on the interpretation and application of these guidelines by healthcare professionals. While guideline adherence in relation to pharmacotherapy in FEP [12] and its benefits have been investigated in several studies [13, 14], there are only sparse data about adherence to these guidelines in a real-world clinical setting with regard to diagnostic assessment in FEP. An Australian study found high rates of adherence to local guidelines, with 80% of referred patients undergoing a physical assessment and CT brain scans within three months of admission [15]. However, the study population also included individuals with bipolar disorder. Furthermore, it is unclear how these findings translate to a European setting. We conducted a PubMed and Google Scholar search, including German-language publications, but did not identify directly comparable studies from Europe or North America. This highlights the lack of research on diagnostic guideline adherence in first-episode psychosis outside of Australia.

Against this background, the present study aims to address this gap by investigating whether patients with FEP are assessed according to the recommendations of the DGPPN S3 guidelines for schizophrenia [4] in a large academic psychiatric hospital in Switzerland. The second goal was to identify potential factors explaining why these guidelines are not consistently followed, thereby identifying potential systemic barriers in the assessment of individuals with FEP. To achieve these objectives, we conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study including all individuals diagnosed with FEP admitted to the hospital within twelve months, aiming to provide critical insights into the practical application of guideline-based care and to highlight necessary areas for improvement.

We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional study including all FEP patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital over 12 calendar months, namely from 1 October 2022 to 30 September 2023. Data were extracted from the electronic healthcare records (EHR) of first-episode psychosis (FEP) patients admitted to the Psychiatric University Hospital Zurich (PUK). PUK serves as a public healthcare facility, responsible for delivering psychiatric care across a diverse landscape encompassing both urban and rural areas, catering to roughly 500,000 residents. Within the hospital’s framework, the Department of Adult Psychiatry and Psychotherapy operates specialised inpatient units for acute psychiatric admissions as well as a specialised ward for patients with first-episode psychosis. Our investigation specifically focuses on the diagnostic procedures completed during the first hospitalisation of each patient with first-episode psychosis.

The study was designed as a quality assurance project of the Department of Adult Psychiatry and Psychotherapy of the PUK. As a descriptive quality assurance study, no formal primary or secondary outcomes were predefined. The objective was to assess completion rates of diagnostic procedures recommended by DGPPN S3 guidelines [4] and to identify implementation barriers. The ethics committee of the canton of Zurich assessed the study and declared that it did not fall within the scope of the Swiss Human Research Act (BASEC-Nr. Req-2024-00033). Therefore, authorisation from the ethics committee was not required. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

As a quality assurance project, the study did not need to be preregistered. No formal study protocol was prepared prior to data collection, and the study was not registered in any clinical trial registry.

Data were collected using a two-stage procedure aimed at minimising bias by incorporating both individual case examination and subsequent verification. The EHR of all patients meeting the inclusion criteria were screened by a medical professional (a certified psychologist or a physician). If inclusion criteria were met, data were extracted. The screening decisions and extracted data were reviewed by one of the two senior authors to ensure correctness and consistency. Data extraction followed a standardised validation process. One medical doctor extracted data from the EHRs and entered them into a research database. All extracted data were subsequently verified by a second medical doctor. Any discrepancies identified during the validation process were resolved through discussion with the senior authors until consensus was reached. Data were collected between 1 February 2024 and 31 March 2024. The 1-year observation period was chosen as this study was designed as a quality control project, with data from this timeframe considered representative of the institutional clinical care processes and practice patterns, while also ensuring that the most current data were analysed.

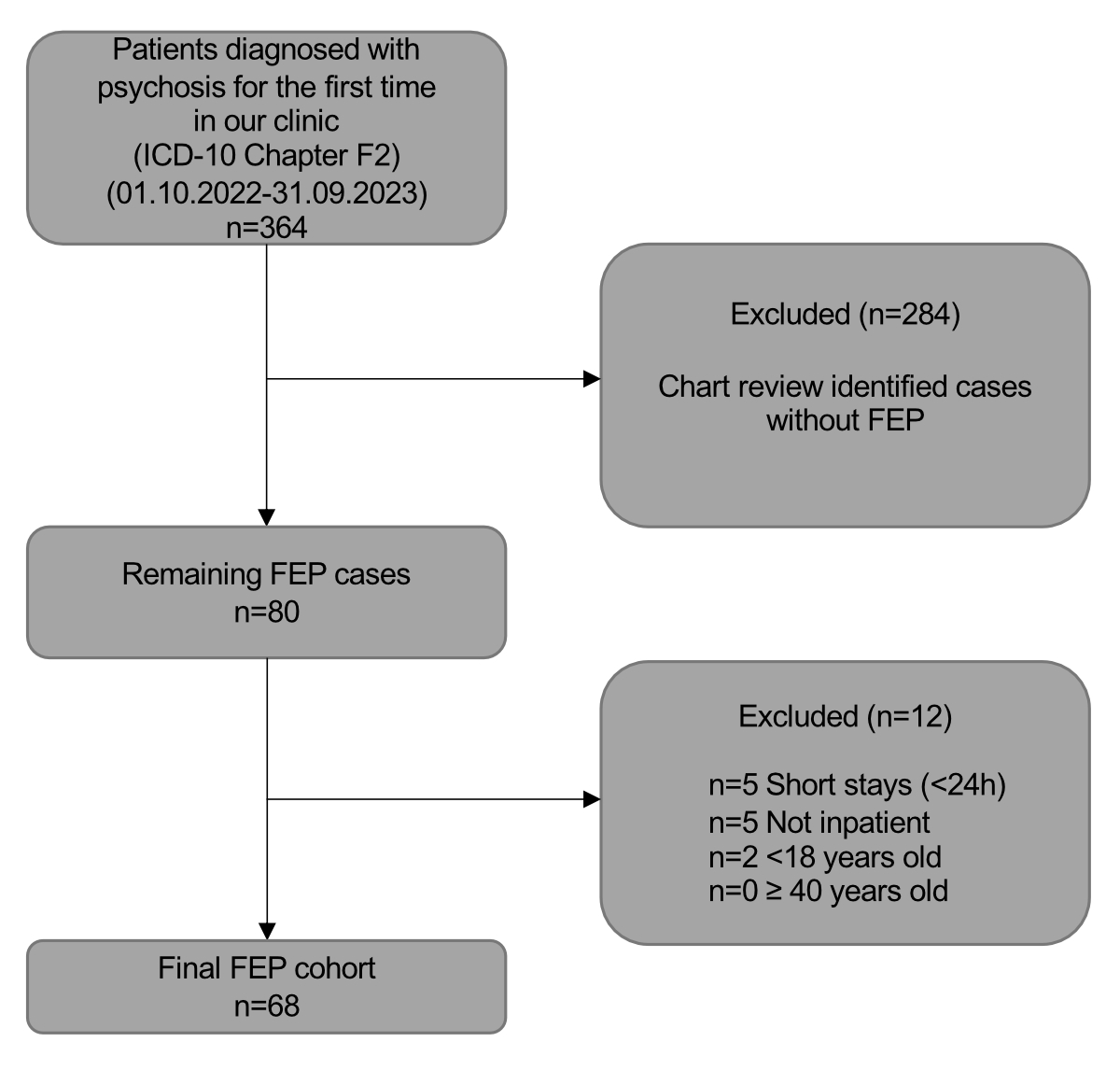

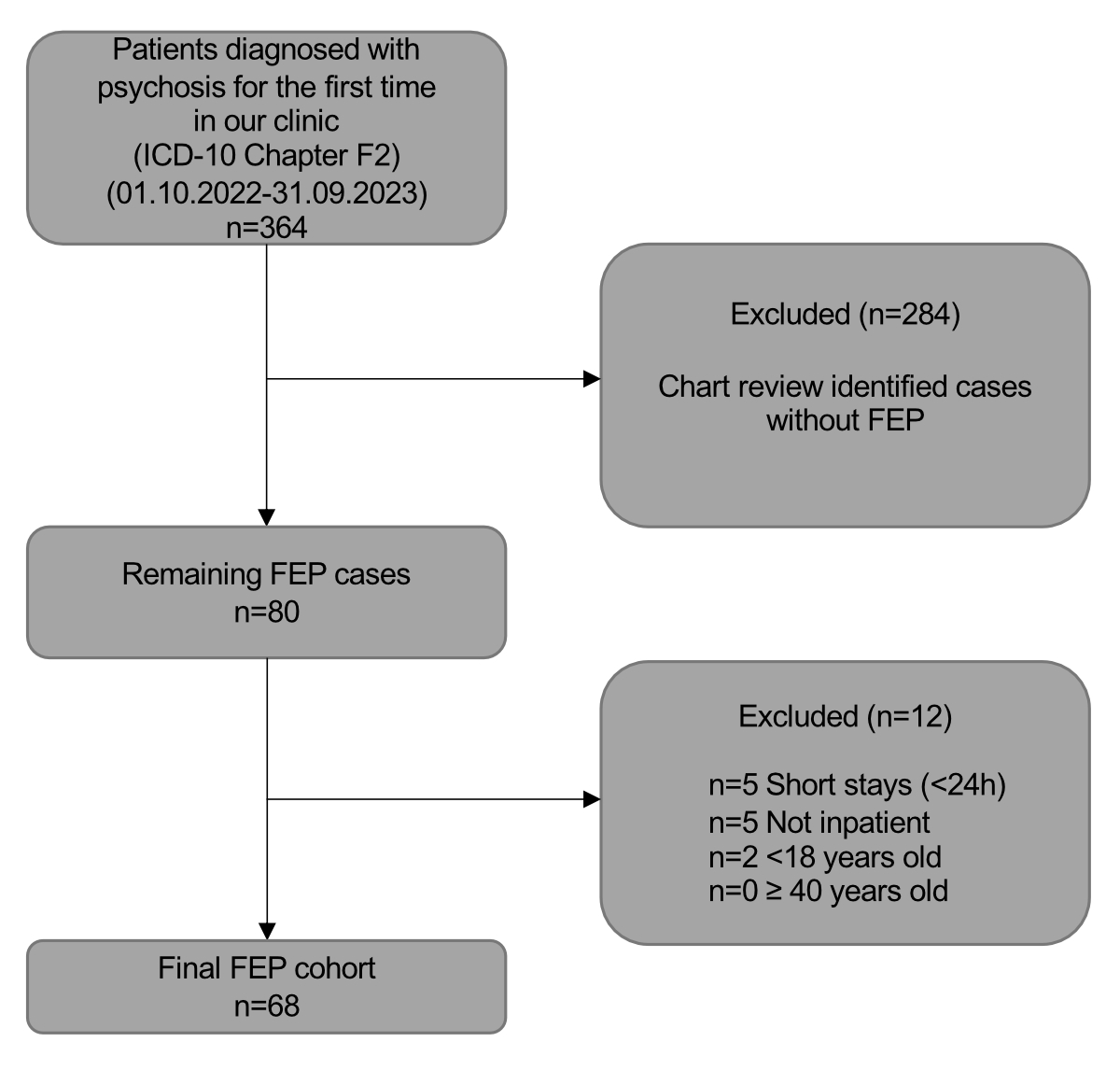

The inclusion criteria for participants were strictly defined to focus on individuals diagnosed with specific ICD-10 codes indicative of psychosis (F06, F09, F20.0–F20.9, F21.X, F23.X, F24.X, F25.X, F28, F29), as documented in their discharge reports. It should be noted that patients with final diagnoses of substance-induced psychotic disorders (F1X.5) were excluded, as our study was focused on schizophrenia spectrum disorders; however, patients initially suspected of substance-induced psychosis were included if the final diagnostic assessment supported a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. To narrow the focus to first-episode psychosis, individuals aged over 40 years at the time of admission or those hospitalised for less than 24 hours were excluded. In addition, only patients experiencing their first hospitalisation for a psychotic episode were included; patients with recurrent hospitalisations due to psychotic episodes were excluded. The age criterion was set based on the typical age range of onset for most psychotic disorders and to maintain a homogeneous study population relevant to the typical clinical presentation of FEP. Figure 1 shows the patient selection process.

Figure 1Patient selection chart.

An S3 guideline is the highest quality level of a clinical guideline and serves as a decision-making tool for the treatment of a specific condition or state. It is developed by an expert group, based on evidence-based medicine and broad consensus among professionals. Regular reviews and updates ensure that it reflects the latest findings and developments in medical practice.

The DGPPN S3 guideline for schizophrenia is an updated expansion of the DGPPN’s previous S3 guideline for schizophrenia. It follows the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF) framework and is patient-centred, evidence-based and consensus-based. It is currently undergoing revision [4].

For FEP, the guideline recommends a battery of examinations that are divided into a compulsory and an optional part. The following are recommended as mandatory: a complete physical and neurological examination including weight, height, temperature, blood pressure and pulse; a detailed blood test encompassing a full blood count, fasting blood glucose, liver and kidney function tests, electrolyte levels, inflammation markers and thyroid function assessment; a urine drug screen; and structural cranial imaging using MRI with T1, T2 and FLAIR sequences or CT if MRI is contraindicated or unavailable.

Further investigations are recommended as optional, each to be performed after clinical differential diagnostic suggesting a secondary somatic origin of the symptoms, for which the guideline specifies criteria. These include a lumbar puncture and a neuropsychological assessment – focusing on attention, learning and memory, executive functions and social cognition – to inform decisions on further treatment and rehabilitation options. Furthermore, an EEG should be considered if clinical signs suggest possible epileptic activity or other specific neurological disorders [4].

Demographic information was obtained including sex (male, female) and age (in years). Basic administrative data included date of admission and discharge, length of stay as well as exposure to compulsory measures (e.g. isolation or compulsory medication). We investigated whether laboratory tests were conducted, including HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B and C screens. We recorded whether urine drug tests were administered and, if so, whether any drugs were detected. Moreover, we checked whether ECGs were performed, and whether a neurological physical examination was carried out to identify any abnormalities. The neurological assessment includes evaluation of motor functions, reflexes, sensory abilities, coordination and cranial nerve functions. Furthermore, cognitive function and gait were assessed to detect neurological deficits, as well as body weight and blood pressure. We noted whether an MRI scan, an EEG or lumbar puncture had been performed. We also investigated whether the diagnostic work-up had led to changes in treatment. A finding of substance use led to appropriate clinical interventions including withdrawal management, substance use counselling, reduction strategies; it also informed differential diagnostic considerations between substance-induced and primary psychotic disorders.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population. All continuous variables (age, length of stay, time to MRI) were summarised using medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) given the sample size and distribution characteristics. Categorical variables, such as sex and the presence of abnormal findings on MRIs, were summarised using counts and percentages. The results are reported following the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guideline. All analyses were conducted between March and May 2024 using R statistical software (version 4.4.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using packages from the tidyverse family [16]. The analytical code is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. Individual patient data cannot be shared due to privacy regulations and the impossibility of adequately anonymising clinical data.

A total of 364 patients younger than 40 years with ICD-10 codes indicative of psychosis were admitted during the observation period. Of those 364, 296 did not meet the criteria for first-episode psychosis, leading to a final sample size of 68. Demographics, length of stay, time to MRI and involuntary treatment rates are summarised in table 1. The assessment completion rates are presented in table 2.

Table 1Demographics and sample characteristics of first-episode psychosis patients (n = 68).

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 29.0 (23.0–33.0) |

| Men, n (%) | 44 (64.7%) |

| Women, n (%) | 24 (35.3%) |

| Length of stay, days, median (IQR) | 22 (12–40) |

| Time to MRI, days, median (IQR)* | 11 (5–18) |

| Voluntary admission, n (%) | 32 (47.1%) |

| Involuntary admission, n (%) | 36 (52.9%) |

| Any compulsory measures, n (%) | 18 (26.5%) |

* Only applicable to patients who received MRI (n = 38)

Table 2Assessment completion rates (n = 68).

| Assessment | n (%) of patients assessed |

| Comprehensive status examination | 66 (97.1%) |

| Pulse / blood pressure | 68 (100.0%) |

| Weight | 64 (94.1%) |

| ECG | 58 (85.3%) |

| Drug urine test | 56 (82.4%) |

| Blood analysis | 66 (97.1%) |

| HIV testing | 33 (48.5%) |

| Syphilis testing | 31 (45.6%) |

| Hepatitis B testing | 28 (41.2%) |

| Hepatitis C testing | 28 (41.2%) |

| MRI | 38 (55.9%) |

| EEG | 26 (38.2%) |

| Lumbar puncture | 4 (5.9%) |

Of the 68 patients included, the majority were men (n = 44 or 64.7%) and their median age was 29 years (IQR: 23.0–33.0). The median length of stay in the sample was 22 days (IQR: 12–40). Just over half of participants (n = 35 or 51%) were admitted to the clinic involuntarily. Furthermore, 18 (26%) participants received at least one compulsory measure. The median time to MRI was 11 days (IQR: 5–18). Nearly all participants (n = 66 or 97.1%) underwent a comprehensive neurological examination. Two participants were only briefly examined due to their violent behaviour. No abnormalities were found in any of the neurological examinations. Drug urine tests were conducted in 56 (82.4%) participants; findings are shown in table 3. Briefly, 25 cases (44.6% of those who underwent a drug urine test) were positive for THC and 13 cases (23.2%) were positive for benzodiazepines (all of which were prescribed during their stay). Blood analyses were performed in 66 (97.1%) cases and ECG in 58 (85.3%) cases. While comprehensive blood analysis was compulsory according to the DGPPN guidelines, infectious disease screening (HIV, hepatitis, syphilis) was performed selectively based on anamnestic or clinical indications as specified in the guidelines; this explains the lower completion rates for these tests. MRI scans were completed for 38 (55.9%) participants. In one (1.4%) case, the MRI showed inflammatory white matter lesions which led to an adjustment in treatment while all other MRIs showed no clinically relevant abnormalities. An MRI was not performed in 28 patients for the following reasons: the participant was discharged on request (16 or 23.5%); patient refusal (10 or 14.7%); one patient was incarcerated and conducting an MRI was not possible in the current setting; for one patient, the reason could not be determined. Similar reasons also accounted for the other measurements, such as weight measurements, not being conducted. EEGs were conducted in 26 (38.2%) cases and lumbar punctures were performed only in 4 (5.9%) cases. EEG and lumbar punctures were performed selectively based on clinical indications as specified in the DGPPN guidelines – for example, suspected epileptic activity for EEG, and clinical, laboratory or imaging findings suggesting an organic aetiology for lumbar puncture – rather than as routine screening procedures.

Table 3Number of patients who underwent a drug urine test / neurological examination / MRI and percentage of abnormal findings for each.

| Variable | n (%) |

| Drug urine test (n = 56) | 56 (100%) |

| … THC | 25 (44.6%) |

| … Benzodiazepine | 13 (23.2%) |

| … Cocaine | 1 (1.8%) |

| … Opioids | 1 (1.8%) |

| Neurological examination (n = 66) | 66 (100%) |

| … Abnormalities | 0 (0.0%) |

| MRI (n = 38) | 38 (100%) |

| … Abnormal findings* | 11 (28.9%) |

| … Finding leading to change of therapy | 1 (2.6%) |

* 6 white matter lesions, 1 vascular, 1 cyst, 3 other

This study evaluated to what extent the diagnostic work-up for first-episode psychosis (FEP) in a Swiss tertiary setting adhered to procedures recommended by the corresponding DGPPN S3 guideline [4]. The setting can be regarded as representative of an urban region with a population of approximately 500,000 due to its primary care mandate and it is also one of the largest academic institutions of its kind in Europe. We found that completion rates for basic assessments, including physical and neurological examinations and blood analyses, were almost 100%. The completion rate of other compulsory assessments was lower: 82.4% for a drug urine test and 55.9% for MRI. The primary reasons for non-completion were patient refusal and early patient-requested discharge, suggesting that lack of insight among patients might be a key factor limiting adherence to existing diagnostic guidelines in a clinical setting.

Notably, our findings corroborate high completion rates for essential diagnostic procedures in FEP patients similar to those reported in an Australian setting [15]. In the Australian study, approximately 50% of participants completed imaging within three weeks of admission, rising to 80% after three months. In contrast, the median hospital length of stay of 22 days in our study yielded comparable imaging rates (55.9%) and consistently high adherence (over 80%) for other mandated assessments (see table 4). This suggests that an integrated approach during initial FEP admissions can expedite crucial investigations, achieving near-complete work-ups in a relatively short time (median of 11 days to MRI). Such comprehensive, early-stage evaluations likely facilitate more targeted treatment planning at the beginning of an illness trajectory [17].

Table 4Overall adherence to mandatory parts of various guidelines.

| DGPPN (2019) | APA (2020) | NICE (2014/2023) | |

| Physical examination | Thorough examination including neurological status recommended | Physical examination required; neurological focus | Comprehensive including vital signs and neurological status |

| Basic laboratory diagnostics | Blood count, liver and kidney values, electrolytes, glucose, TSH, B12, folic acid | Blood count, TSH, liver values, B12/folic acid, if applicable HIV/hepatitis | Blood count, liver values, glucose, lipids, TSH, if applicable HIV/Hepatitis |

| Imaging (MRI/CT) | Mandatory at first manifestation | Recommended if clinically indicated | Not recommended |

| Urine screening (drugs) | Mandatory at first manifestation | Recommended for all first psychoses | Standard recommendation for differential diagnosis of drug-induced psychosis |

| ECG | Recommended before starting antipsychotic therapy (QTc interval) | With cardiac risk or QTc-relevant medications | Mandatory with QT-prolonging medication |

| Infection diagnostics | HIV, syphilis, hepatitis, recommended if clinically indicated | Only if increased risk | Recommended with risk factors (e.g. IV drug use) |

| EEG | Only if suspicion of epilepsy, encephalopathy, etc. | With neurological symptoms or atypical course | Only with red flags |

| Lumbar puncture | Only with suspicion of e.g. autoimmune encephalitis | Only with neurological red flags | Only with justified suspicion |

| Overall adherence with all mandatory parts (%) | 55.9% incl. MRI; 82.4% excl. MRI | 82.4% | 82.4% |

Beyond immediate diagnostic considerations, robust guideline adherence in schizophrenia has been associated with both cost savings and improved quality-adjusted life-years [13]. Beneficial outcomes associated with guideline-compliant pharmacotherapy, such as enhanced work capacity [14], may extend to thorough diagnostic adherence, although this remains to be shown. Cost-effectiveness was not examined in our study, even though this issue underpins many ongoing debates regarding universal neuroimaging in FEP [2, 18, 19]. While neuroimaging may identify treatable abnormalities in only a small fraction of cases (reflecting the structural brain heterogeneity in schizophrenia in general) [20] and there is a bigger fraction of incidental abnormalities of unknown relevance [2, 21], its potential long-term benefits could justify wider application. Overall, our results reinforce that guideline-mandated assessments are feasible within tertiary inpatient care, in particular in a large academic hospital, potentially improving outcomes through timely identification of organic contributors to psychosis.

A secondary observation was that many patients refused or were discharged prior to completing MRI or additional procedures like EEG and lumbar punctures, likely influenced by limited insight. Although we did not formally assess insight, it is well documented that FEP often entails denial of the need for evaluation or treatment [22], posing risks for medication adherence and longer-term clinical outcomes [23, 24]. From an ethical standpoint, compelling patients to undergo investigations without their consent must be carefully balanced against potential benefits. In our cohort, nearly all patients who declined MRI still consented to a physical and neurological examination, indicating a nuanced acceptance of less invasive procedures. This at least enabled the detection of physical or neurological red flags, which could justify more assertive diagnostic steps in rare cases.

Looking forward, targeted educational interventions like structured psychoeducation or motivational interviewing [25, 26] alongside the development of personalised explanatory frameworks could help elucidate the rationale behind comprehensive assessments, thereby enhancing patient engagement. Adopting shared decision-making that respects patient autonomy while emphasising the clinical utility of these evaluations may increase acceptance rates. Future research should investigate strategies to improve insight and acceptance of recommended procedures in FEP, particularly among people who initially refuse them.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, this was a single-centre, retrospective study, which limits the generalisability of our findings to other healthcare settings, such as community clinics or different countries. Second, the relatively small sample size (n = 68) also limits the reliability of our findings. Third, we excluded individuals older than 40 years, thereby omitting late-onset psychosis cases that can present during the well-known second peak of first manifestations of schizophreniform disorders which is often found in female patients [27]. While this cutoff targeted the more common age range for FEP, it limits the applicability of our conclusions to a broader spectrum of individuals with FEP. Furthermore, our reliance on medical records may introduce documentation bias, as not all completed procedures or reasons for non-completion may have been fully recorded. Future multicentre prospective studies that include a wider age range and standardised documentation practices are needed to confirm and extend these findings. Fourth, our focus on schizophrenia spectrum disorders led to the exclusion of patients with substance-induced psychotic disorders, which may limit the generalisability of our findings to the broader population of patients presenting with first-episode psychosis. Fifth, our study focused exclusively on hospitalised patients, while some individuals with first-episode psychosis may be treated initially in outpatient settings. This limitation may affect the generalisability of our findings to the broader population of individuals experiencing first-episode psychosis. Additionally, while we were able to identify reasons for non-completion of MRI procedures, documentation of reasons for non-completion of other diagnostic tests such as drug screening and ECG was insufficient, limiting our ability to distinguish between workflow issues and patient refusal for these procedures.

In conclusion, FEP patients at our Swiss tertiary centre generally received a thorough diagnostic evaluation according to the relevant guideline with non-completion of MRI mainly due to patient refusal. These results confirm that mandated assessments are achievable during acute admissions. Future research should focus on strategies to mitigate refusal and enhance insight, and evaluate whether full adherence translates into better clinical and economic outcomes.

The analytical code is available upon request from the corresponding author. Individual patient data cannot be shared due to privacy regulations and the impossibility of adequately anonymising clinical data.

Author contributions: Conceptualization: KJS, TRS, AB; methodology: KJS, TRS, AB; formals analysis and investigation: KJS, MCK, CC, FCG, ABH, AHH, MM, TRS, AB; project administration: KJS, MCK, CC, FCG, ABH, AHH, MM; supervision: PH, ES; writing – original draft: KJS, TRS, AB; writing – review and editing: all authors

No funding was acquired for this study.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. PH has received grants and honoraria from Novartis, Lundbeck, Takeda, Mepha, Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Neurolite and OM Pharma outside of this work. AB has received honoraria and travel fees from Recordati, Schwabe, Lundbeck and OM Pharma outside of this work. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

1. Freudenreich O, Schulz SC, Goff DC. Initial medical work-up of first-episode psychosis: a conceptual review. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2009 Feb;3(1):10–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7893.2008.00105.x

2. Blackman G, Neri G, Al-Doori O, Teixeira-Dias M, Mazumder A, Pollak TA, et al. Prevalence of Neuroradiological Abnormalities in First-Episode Psychosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023 Oct;80(10):1047–54. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.2225

3. Barnett JH, Werners U, Secher SM, Hill KE, Brazil R, Masson K, et al. Substance use in a population-based clinic sample of people with first-episode psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2007 Jun;190(6):515–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.024448

4. AWMF Leitlinienregister [Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 21]. Available from: https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/038-009

5. Overview | Structural neuroimaging in first-episode psychosis | Guidance | NICE [Internet]. NICE; 2008 [cited 2024 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta136

6. 2 Clinical need and practice | Structural neuroimaging in first-episode psychosis | Guidance | NICE [Internet]. NICE; 2008 [cited 2024 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta136/chapter/2-Clinical-need-and-practice

7. American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines [Internet]. Psychiatry Online. [cited 2024 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.psychiatryonline.org/guidelines

8. Forbes M, Stefler D, Velakoulis D, Stuckey S, Trudel JF, Eyre H, et al. The clinical utility of structural neuroimaging in first-episode psychosis: A systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2019 Nov;53(11):1093–104. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867419848035

9. Borgwardt SJ, Radue EW, Götz K, Aston J, Drewe M, Gschwandtner U, et al. Radiological findings in individuals at high risk of psychosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006 Feb;77(2):229–33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2005.069690

10. Perrottelli A, Giordano GM, Brando F, Giuliani L, Mucci A. EEG-Based Measures in At-Risk Mental State and Early Stages of Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review [Internet]. Front Psychiatry. 2021 May;12:653642. [cited 2024 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.653642/full

11. Pollak TA, Lennox BR. Time for a change of practice: the real-world value of testing for neuronal autoantibodies in acute first-episode psychosis. BJPsych Open. 2018 Jul;4(4):262–4. doi: https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2018.27

12. Drosos P, Brønnick K, Joa I, Johannessen JO, Johnsen E, Kroken RA, et al. One-Year Outcome and Adherence to Pharmacological Guidelines in First-Episode Schizophrenia: Results From a Consecutive Cohort Study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;40(6):534–40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000001303

13. Jin H, Tappenden P, MacCabe JH, Robinson S, McCrone P, Byford S. Cost and health impacts of adherence to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence schizophrenia guideline recommendations. Br J Psychiatry. 2021 Apr;218(4):224–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.241

14. Ito S, Ohi K, Yasuda Y, Fujimoto M, Yamamori H, Matsumoto J, et al. Better adherence to guidelines among psychiatrists providing pharmacological therapy is associated with longer work hours in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia (Heidelb). 2023 Nov;9(1):78. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-023-00407-3

15. Petrakis M, Hamilton B, Penno S, Selvendra A, Laxton S, Doidge G, et al. Fidelity to clinical guidelines using a care pathway in the treatment of first episode psychosis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011 Aug;17(4):722–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01548.x

16. Corp IB. Released 2023. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0.2.0 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

17. Reilly J, Newton R, Dowling R. Implementation of a first presentation psychosis clinical pathway in an area mental health service: the trials of a continuing quality improvement process. Australas Psychiatry. 2007 Feb;15(1):14–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10398560601083027

18. Forbes M, Stuckey S, Kisely S. Concerns Regarding Strength of Conclusions in Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Neuroradiological Abnormalities in First-Episode Psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024 Jan;81(1):107. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.4390

19. Blackman G, Kempton MJ, McGuire P. Concerns Regarding Strength of Conclusions in Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Neuroradiological Abnormalities in First-Episode Psychosis-Reply. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024 Jan;81(1):109. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.4399

20. Omlor W, Rabe F, Fuchs S, Cecere G, Homan S, Surbeck W, et al. Estimating multimodal brain variability in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A worldwide ENIGMA study. bioRxiv. 2023 Nov 2;2023.09.22.559032.

21. Bellani M, Perlini C, Zovetti N, Rossetti MG, Alessandrini F, Barillari M, et al. Incidental findings on brain MRI in patients with first-episode and chronic psychosis. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2022 Oct;326:111518. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2022.111518

22. Baier M. Insight in schizophrenia: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010 Aug;12(4):356–61. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-010-0125-7

23. Buckley PF, Wirshing DA, Bhushan P, Pierre JM, Resnick SA, Wirshing WC. Lack of insight in schizophrenia: impact on treatment adherence. CNS Drugs. 2007;21(2):129–41. doi: https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200721020-00004

24. Lincoln TM, Lüllmann E, Rief W. Correlates and long-term consequences of poor insight in patients with schizophrenia. A systematic review. Schizophr Bull. 2007 Nov;33(6):1324–42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbm002

25. Ertem MY, Duman ZÇ. The effect of motivational interviews on treatment adherence and insight levels of patients with schizophrenia: A randomized controlled study. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2019 Jan;55(1):75–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12301

26. Panchalingam J, Horisberger R, Corda C, Kleisner N, Krasnoff J, Burrer A, et al. Motivational Interviewing in Patients with Acute Psychosis: First Insights from a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. 2024 [cited 2025 Jan 14]; Available from: https://osf.io/x3mub/download

27. Häfner H. From Onset and Prodromal Stage to a Life-Long Course of Schizophrenia and Its Symptom Dimensions: How Sex, Age, and Other Risk Factors Influence Incidence and Course of Illness. Psychiatry J. 2019 Apr;2019:9804836. doi: https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/9804836