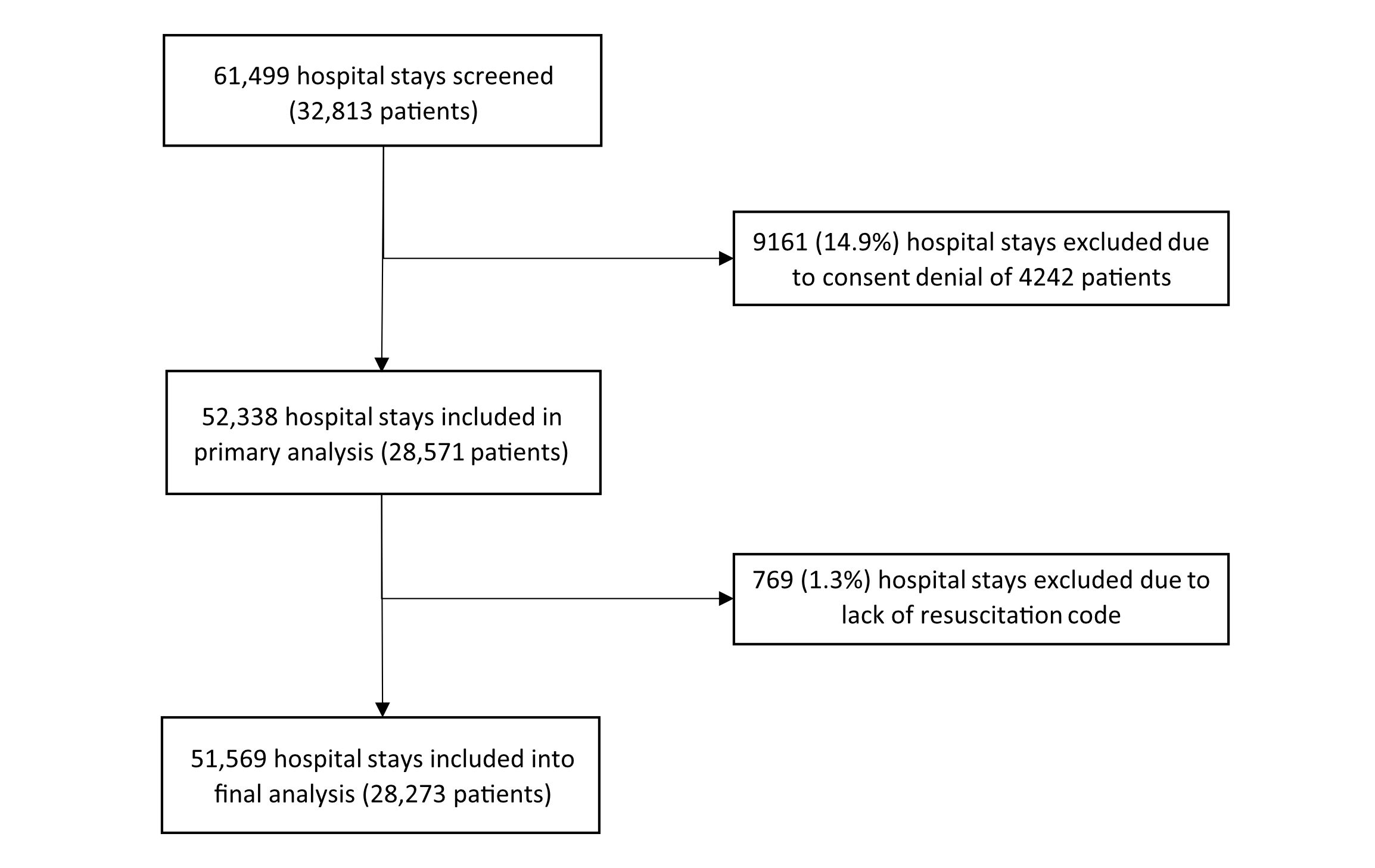

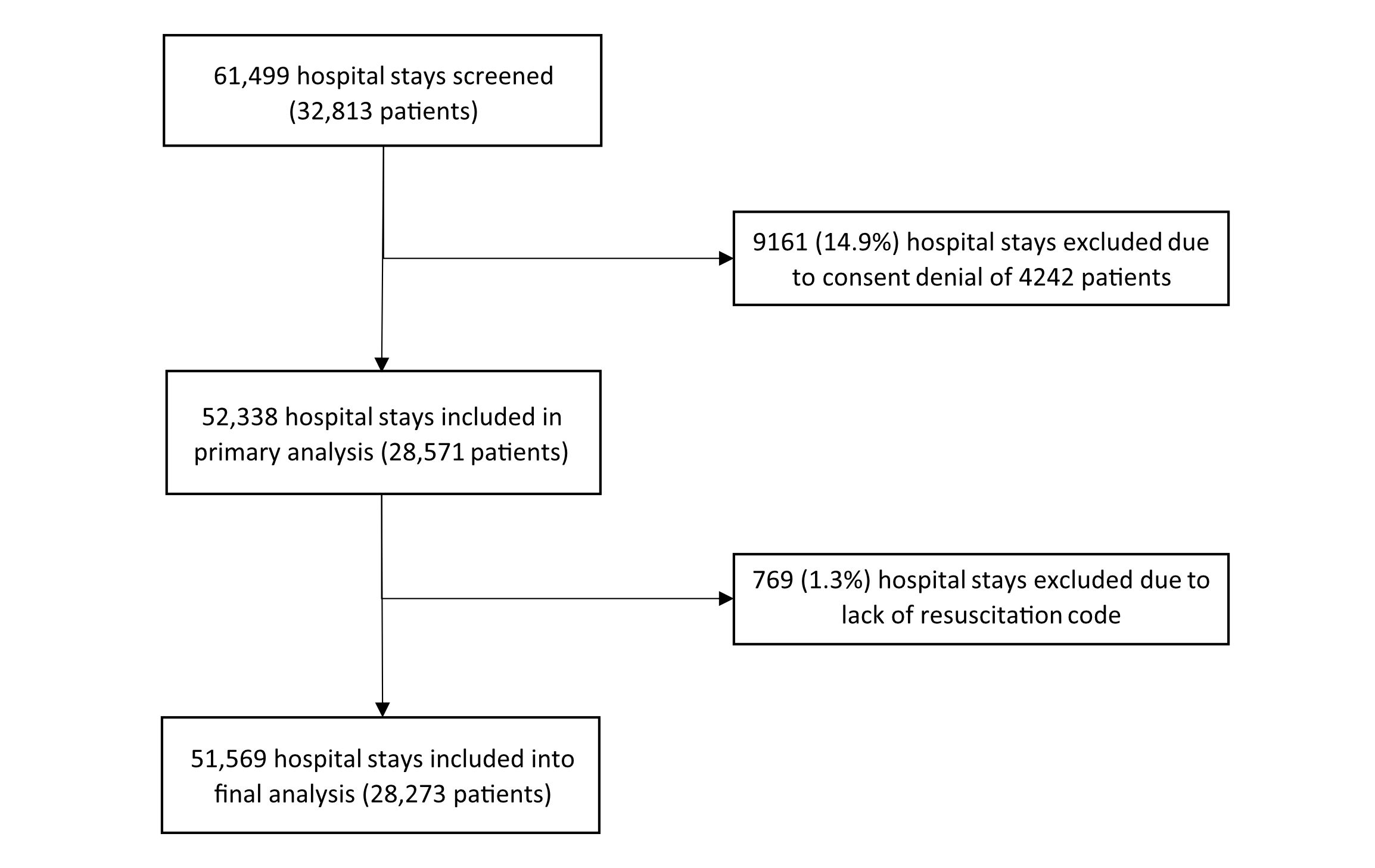

Figure 1Flow diagram.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4477

Limitation of therapeutic effort corresponds to withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining therapeutic measures [1]. Usual care requires that each hospitalised patient has goal of care documentation of which of these treatments should or should not be offered in case of an acute life-threatening event. The decision must be based on a discussion balancing prognosis, risks, benefits and patient preferences. Advance directives can support the establishment of limitation of therapeutic effort in case of loss of capacity of the patient to make health decisions. However, the proportion of the population in Switzerland who have written such directives is low [2]. Limitation of therapeutic efforts classically discussed in hospital are Do Not Resuscitate and Do Not Intubate orders. Other orders needing discussion depending on the clinical situation are intensive care unit (ICU) or intermediate care unit (IMCU) admission (refusals are, respectively, Do Not Admit to ICU and Do Not Admit to IMCU). These orders might determine which life-sustaining measures (such as vasopressor support, non-invasive ventilation, dialysis or artificial feeding) can be provided.

The prevalence of Do Not Resuscitate status varies according to cultural issues [3], clinical setting and hospital ideology [4]. A small (194 patients) study in a Swiss internal medicine service found a 53% prevalence of Do Not Resuscitate in 2013 [5]. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CRP) prognosis has been well studied. Several studies, scores and ethical recommendations have been recently published to help to establish a prognosis and discuss the adequacy or futility of cardiopulmonary resuscitation [6–11]. For example, frailty, defined by a clinical frailty scale ≥5/9, was demonstrated to represent a good predictor of futility of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in older adults [6, 7]. Whether better awareness of this new information contributed to changes in the prevalence of in-hospital Do Not Resuscitate codes is not known.

It is important to note that the incidence of in-hospital cardiac arrest is relatively low, ranging from 1 to 10 per 1000 admissions [12], indicating that the application of resuscitation codes in clinical practice is uncommon. Decisions on whether or not to admit a patient in the ICU are much more frequent, as 6% of hospital stays in Switzerland and up to 26.9% in the USA involve intensive care [13, 14]. Limiting ICU-specific life-sustaining treatments, other than cardiopulmonary resuscitation, is one of the most frequent ethical difficulties encountered by doctors in clinical practice [15], and can be considered as depriving a patient of potential “life-saving” treatments. However, decision-support tools helping to discuss intubation or ICU treatments [16] are scarcer than for resuscitation.

In addition, even though consequences of critical illness are now better described [17], and that many conditions (such as frailty [18], metastatic cancer, haematological malignancies [19], cirrhosis [20], severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [21], advanced heart failure [22] and dementia [23]) have been demonstrated to be associated with lower survival in case of critical illness, no data exist on the role played by these morbidities in the establishment of Do Not Admit to ICU orders in a general internal medicine population.

Furthermore, development of non-invasive ventilation and creation of IMCUs has allowed to successfully treat patients with a Do Not Intubate order outside an ICU, especially for respiratory failure [24] or sepsis [25]. The prevalence of Do Not Intubate orders in case of respiratory failure has risen over the first 20 years of the 21st century, reaching 32% for the 2015–2019 period [26]. Whether this is also the case in a general hospitalised internal medicine population is not known.

Yet, data are lacking about the prevalence of limitations of therapeutic efforts other than Do Not Resuscitate orders, and the reasons for these limitations of therapeutic efforts.

Therefore, the main goal of the study was to determine the prevalence of limitation of therapeutic efforts via Do Not Resuscitate, Do Not Admit to ICU and Do Not Admit to IMCU orders in a general internal medicine hospital and the determinants of their establishment. The primary objective was to measure the evolution of the prevalence of limitation of therapeutic efforts via Do Not Resuscitate, Do Not Admit to ICU and Do Not Admit to IMCU orders from 2013 to 2023 on a yearly basis. The secondary objectives were to evaluate the factors associated with the presence of the different limitations of therapeutic efforts, the incidence of new Do Not Resuscitate codes established during a hospital stay in internal medicine, and the factors associated with new Do Not Resuscitate decisions. We also analysed the potential impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on the prevalence of limitations of therapeutic efforts, given the limitation of ICU capacity during this period.

Understanding how and how many limitations of therapeutic efforts are set in a hospital internal medicine department would represent an important starting point for developing future teaching, guidelines and decision-support tools for their establishment.

The LiTherIM (Limitation of Therapeutic effort in Internal Medicine) study is a retrospective study conducted in the internal medicine department of Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV) in Switzerland. The department has 200 beds with some periodic variations, including IMCU beds (14 to October 2018, 16 since November 2018), with extensions during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Most patients are under the responsibility of the internal medicine medical staff, and some are under the responsibility of one of the specialties geriatrics, pneumology, gastroenterology, immunology, endocrinology or nephrology. The intensive care unit service of the hospital has 35 beds, with extensions during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

The hospital guidelines require the physician in charge of the patient to document a resuscitation code (full-code or Do Not Resuscitate in case of cardiac arrest) in a dedicated folder of the electronic medical record. The resuscitation code and other limitations of therapeutic efforts must be filled in after medical evaluation and discussion with the patient. Relatives or medical representatives are involved in case of loss of capacity of discernment. Within the first 48 hours after admission, a “to redefine” code can be filled in, for example, if discussion with the patient was not possible. This code would be considered as “full-code” in case of cardiac arrest during this period. A Do Not Resuscitate code can be unilaterally decided based on medical evaluation of futility of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, but this decision must be integrated in a discussion with the patient or relatives on the goals of care. Additional emergency instructions can be added if relevant, in particular ICU and IMCU admission or not, by selecting a corresponding checkbox. Until July 2018, only Do Not Admit to ICU and Do Not Admit to IMCU options existed. By the end of July 2018, the options ICU admission “Yes” or “No” and IMCU admission “Yes” or “No” were introduced. Capacity for monitoring and organ support therapy in IMCU versus ICU is provided in appendix table S1.

Inclusion criteria were all hospital stays of adult patients admitted to the internal medicine department between 1 January 2013 and 31 July 2023. Exclusion criteria were explicit refusal of reuse of personal data and absence of a documented resuscitation code.

The analysis was carried out at the level of hospital stays not patients, as a given patient might have multiple hospitalisations over the study period, with clinical and personal evolution such as new diagnoses, leading to a decision of new limitation of therapeutic efforts in subsequent stays. Nevertheless, we used the patient ID as a cluster, as patients present specific characteristics that might influence the decisions.

Since January 2013, all patients hospitalised at CHUV are asked for general consent that allows future use of medical records and blood tests performed during their hospitalisation. For patients who did not give explicit consent, reuse of the data was authorised if there was no clear refusal, according to article 34 of the Swiss law on human research, considering that a large proportion of these participants was deceased at the time of the start of the study protocol, which would imply disproportionate difficulties to contact every participant or relatives, and that the results would be of better reliability, without any detrimental effect for the participants. The study was approved by the ethics committee (CER-VD, 22 January 2024, ref 2023-01828). Data were extracted from the electronic records by a dedicated team and anonymised for the analysis.

As a primary outcome, we calculated the yearly prevalence of the presence of the following limitations of therapeutic efforts: Do Not Resuscitate code, Do Not Admit to ICU order or Do Not Admit to IMCU order. As secondary outcomes, we sought the factors associated with limitations of therapeutic efforts, focusing on age, sex, medical diagnoses, religion, length of stay, ICU or IMCU admission; incidence of new Do Not Resuscitate codes during the hospital stay; factors associated with new Do Not Resuscitate codes; impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on prevalence of limitations of therapeutic efforts.

As a resuscitation code is mandatory for all hospitalised patients, patients were dichotomised into Do Not Resuscitate or “full-code”. “To redefine” codes were considered as “full-code” for the analysis. As Do Not Admit to ICU and Do Not Admit to IMCU are limitations of therapeutic efforts which can be added, any patient without this limitation documented in the medical record was considered free of this limitation of therapeutic effort and labelled “Yes” for the analysis (Do Not Admit to ICU versus “ICU-yes and not documented”; Do Not Admit to IMCU versus “IMCU-yes and not documented”).

In case of multiple documentation of limitation of therapeutic efforts through a single hospital stay, we used the latest documentation to calculate the prevalence and the related factors. The annual prevalence was calculated as a percentage of hospital stays based on the year of admission. To calculate the incidence of new Do Not Resuscitate codes, only patients whose resuscitation code was “full-code” on admission were included, and patients with “to redefine” initial codes were excluded. The incidence was calculated as the percentage of hospital stays during which a change from an admission “full-code” to a Do Not Resuscitate code at the end of the stay was documented.

Demographic and administrative data collected were: age at admission (continuous), sex (male, female), religion (Christian Protestant, Christian Catholic, Muslim, Other, unknown), admission date, hospital length of stay, admission to ICU or IMCU (yes, no) and death during hospital stay (yes, no).

We sought the following main or co-diagnoses based on the coding of the International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (complete list available in appendix table S2): chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart failure, cirrhosis, or chronic hepatic dysfunction (alcohol- or non-alcohol-related), stage IV or V chronic kidney disease, malignant neoplasm, metastatic cancer and dementia. As frailty was not coded as such, we sought diagnoses related to age-acquired frailty: delirium, difficulty in walking and falls, and protein-energy malnutrition.

Analysis was performed using Stata® software version 18.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). Results were expressed as number of hospitalisations (percentage) for categorical variables and as median [interquartile range] for continuous variables. Bivariate analysis of the factors associated with limitations of therapeutic efforts was carried out using the chi-squared test for categorical variables and the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. Multivariable analysis was conducted using a mixed logistic regression model clustering on patient ID and adjusting for year (continuous), sex (male, female), comorbidities (present, absent), religion (Christian Protestant, Christian Catholic, Muslim, Other, without/unknown), length of stay (one day increase) and ICU/IMCU stay (yes, no). Results were expressed as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Statistical significance was considered for a two-sided test with p<0.05.

A total of 61,499 hospital stays (32,813 patients) were screened and 51,569 (28,273 patients) were included in the analysis (figure 1). About a third of patients (36.9% or 10,425) had ≥2 hospital stays and 51.5% were male. The mean age at admission was 70.8years, and the age distribution was stable over the ten observed years. Overall, 6% of stays involved an ICU admission while 19.5% included an IMCU admission, with a stable evolution of ICU admissions through the study period (appendix figure S2) except for an increase in 2020 and 2021 (period of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic). Patient death occurred in 5.7% of hospital stays. The most common comorbidities were malignant neoplasm (22.3% of stays), protein-energy malnutrition (22.0%) and heart failure (20.7%). Complete data of the study sample are shown in table 1 and appendix figures S2, S3 and S4.

Figure 1Flow diagram.

Table 1Characteristics of the study sample, Lausanne University Hospital, 2013–2023. Results are expressed as number of cases (percentage) for categorical variables and as median (interquartile range [IQR]) for continuous variables.

| Characteristic | Value | |

| Hospital stays, n | 51,569 | |

| Patients, n | 28,273 | |

| Hospital stays / patient, median [IQR] | 2 [1–4] | |

| Patients with ≥2 hospital stays, n (%) | 10,425 (36.9) | |

| Age at admission in years, mean ± SD | 70.8 ± 17.6 | |

| Male sex, n (% hospitalisations) | 26,565 (51.5) | |

| Length of stay, median (IQR) | 8.2 (5.1–14.0) | |

| Religion, n (% hospitalisations) | Christian Protestant | 19,520 (37.9) |

| Christian Catholic | 18,957 (36.8) | |

| Muslim | 2322 (4.5) | |

| Other | 2459 (4.8) | |

| Without/unknown | 8311 (16.1) | |

| Hospital stays per year, n (% hospitalisations) | 2013 | 3290 (6.4) |

| 2014 | 3730 (7.2) | |

| 2015 | 3828 (7.4) | |

| 2016 | 4158 (8.1) | |

| 2017 | 4864 (9.4) | |

| 2018 | 5386 (10.4) | |

| 2019 | 5594 (10.9) | |

| 2020 | 5920 (11.5) | |

| 2021 | 5903 (11.5) | |

| 2022 | 5755 (11.2) | |

| 2023 (January–July) | 3141 (6.1) | |

| Primary or secondary diagnoses, n (% hospitalisations) | COPD | 6806 (13.2) |

| Heart failure | 10,685 (20.7) | |

| Alcohol-related cirrhosis or hepatic insufficiency | 2057 (4.0) | |

| Non-alcohol-related cirrhosis or hepatic insufficiency | 2224 (4.3) | |

| Advanced chronic kidney disease (stage IV–V) | 2870 (5.6) | |

| Malignant neoplasm | 11,482 (22.3) | |

| Metastatic cancer | 6245 (12.1) | |

| Dementia | 5343 (10.4) | |

| Delirium | 5967 (11.6) | |

| Falls / tendency to fall / difficulty in walking | 4134 (8.0) | |

| Protein-energy malnutrition | 11,335 (22.0) | |

| Number of diagnoses per patient, median (IQR) | 2 (1–2) | |

| Intensive care unit (ICU) stay during hospital stay, n (% hospitalisations) | 3072 (6.0) | |

| Intermediate care unit (IMCU) stay during hospital stay, n (% hospitalisations) | 10,076 (19.5) | |

| Hospital stay with no ICU or IMCU stay, n (% hospitalisations) | 40,703 (78.9) | |

| Death during hospital stay, n (% hospitalisations) | 2913 (5.7) | |

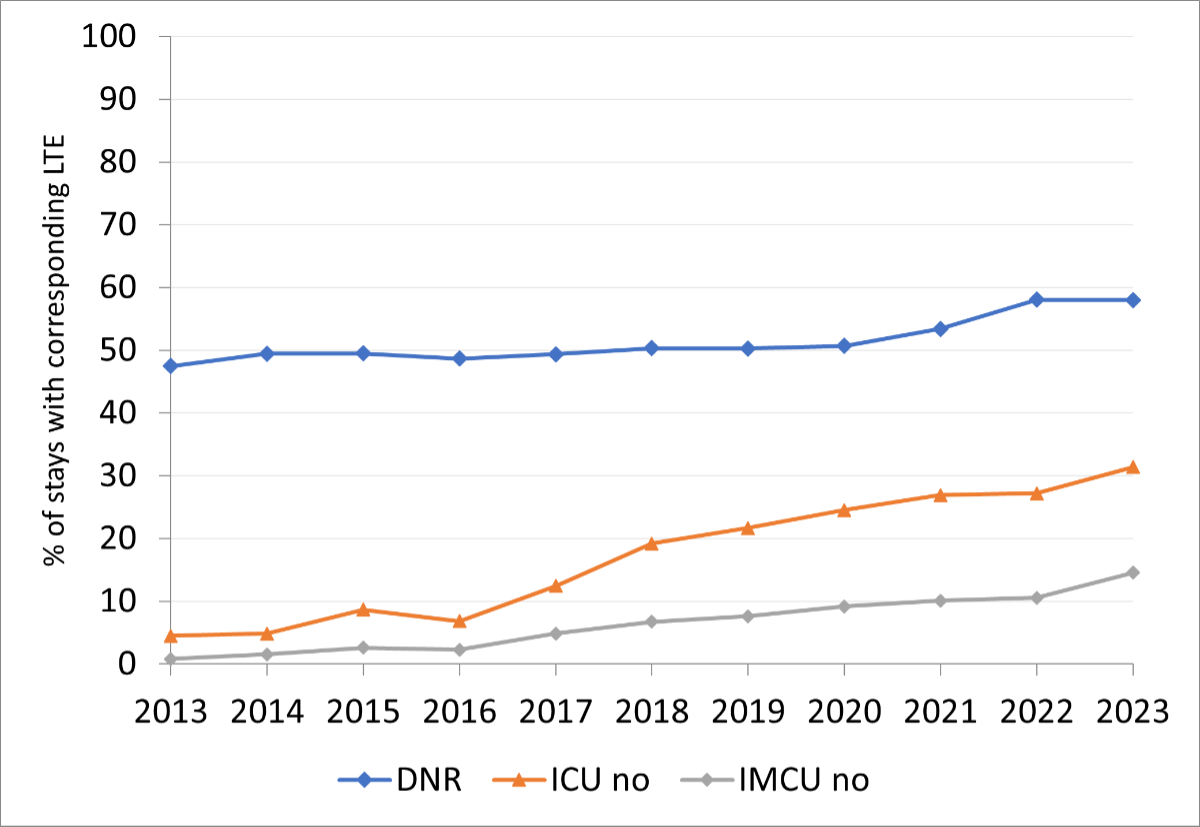

The prevalence of each studied limitation of therapeutic efforts increased over the observation period. The proportion of stays with a Do Not Resuscitate status rose from 47.5% in 2013 to 58.0% in 2023. Similarly, the Do Not Admit to ICU limitation rose progressively from 4.5% to 31.4%, and Do Not Admit to IMCU from 0.8% to 14.6% (figure 2).

Figure 2Yearly prevalence of limitations of therapeutic efforts. DNR: Do Not Resuscitate; ICU no: Do Not Admit to intensive care unit; IMCU no: Do Not Admit to intermediate care unit; LTE: limitation of therapeutic efforts.

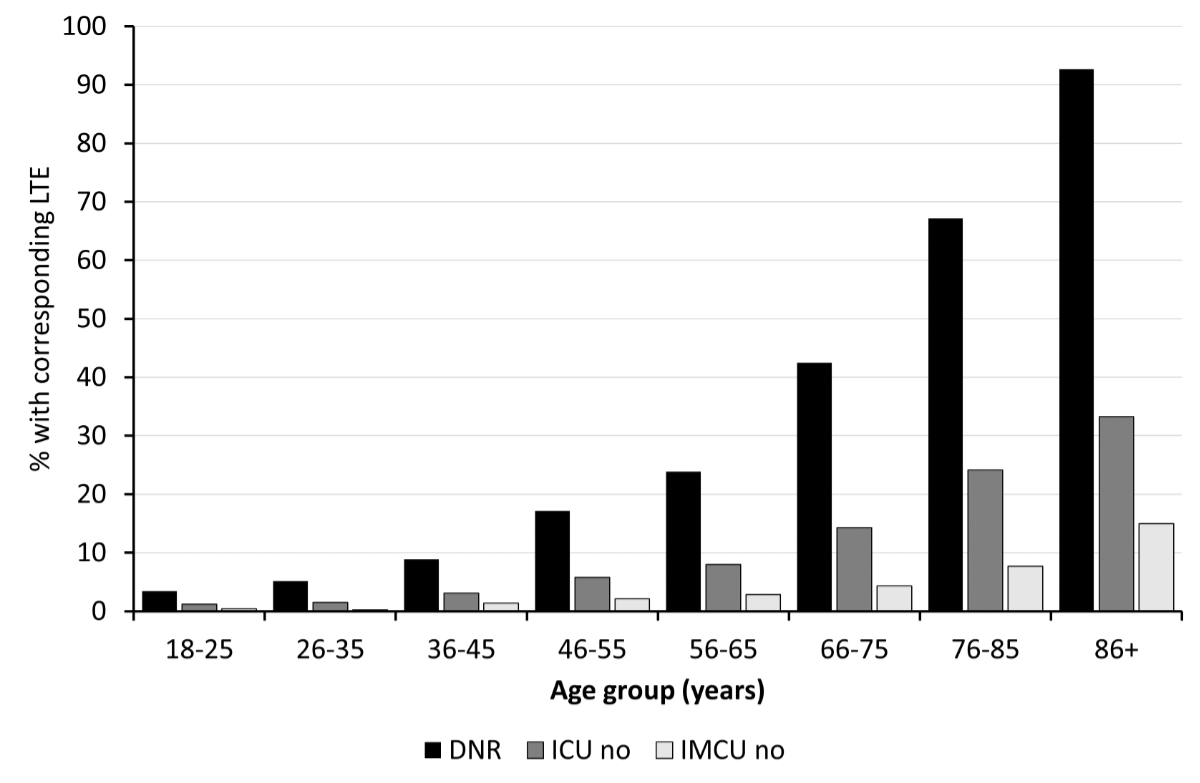

Bivariate (appendix table S3) and multivariable analysis (table 2) showed that the main factor associated with limitation of therapeutic efforts was older age. The prevalence of limitation of therapeutic efforts according to age group is shown in figure 3. In the age group >85 years, Do Not Resuscitate prevalence reached 92.7%, Do Not Admit to ICU 33.3% and Do Not Admit to IMCU 15.0%.

Table 2Multivariable analysis of the factors associated with limitation of therapeutic efforts, Lausanne University Hospital, 2013–2023. Statistical analysis by mixed logistic regression model, clustering for patient ID; results are expressed as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

| Do Not Resuscitate | p-value | ICU no | p-value | IMCU no | p-value | ||

| Year of admission (one year increase) | 1.18 (1.16–1.19) | <0.001 | 1.32 (1.30–1.33) | <0.001 | 1.31 (1.29–1.34) | <0.001 | |

| Age categories | 18–25 | 0.10 (0.06–0.17) | <0.001 | 0.20 (0.12–0.35) | <0.001 | 0.23 (0.09–0.56) | 0.001 |

| 26–35 | 0.15 (0.11–0.22) | <0.001 | 0.23 (0.15–0.35) | <0.001 | 0.11 (0.04–0.31) | <0.001 | |

| 36–45 | 0.26 (0.20–0.33) | <0.001 | 0.42 (0.32–0.55) | <0.001 | 0.54 (0.37–0.81) | 0.003 | |

| 46–55 | 0.57 (0.48–0.68) | <0.001 | 0.75 (0.63–0.89) | 0.001 | 0.78 (0.59–1.02) | 0.07 | |

| 56–65 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||||

| 66–75 | 3.90 (3.43–4.44) | <0.001 | 2.12 (1.89–2.39) | <0.001 | 1.56 (1.29–1.87) | <0.001 | |

| 75–85 | 23.9 (20.6–27.8) | <0.001 | 5.00 (4.46–5.62) | <0.001 | 3.19 (2.67–3.81) | <0.001 | |

| 85+ | 406.4 (329.1–501.7) | <0.001 | 8.98 (7.93–10.2) | <0.001 | 7.52 (6.25–9.05) | <0.001 | |

| Male vs female | 0.66 (0.61–0.72) | <0.001 | 0.83 (0.79–0.88) | <0.001 | 0.84 (0.77–0.92) | <0.001 | |

| Diagnoses | COPD | 1.69 (1.52–1.89) | <0.001 | 1.19 (1.10–1.29) | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.82–1.06) | 0.264 |

| Heart failure | 1.62 (1.48–1.77) | <0.001 | 1.16 (1.08–1.23) | <0.001 | 1.14 (1.04–1.26) | 0.006 | |

| Alcohol-related cirrhosis | 1.50 (1.21–1.86) | <0.001 | 1.37 (1.13–1.65) | 0.001 | 1.41 (1.06–1.89) | 0.019 | |

| Non-alcohol-related cirrhosis | 1.29 (1.06–1.56) | 0.011 | 1.19 (1.00–1.41) | 0.053 | 1.30 (1.01–1.69) | 0.044 | |

| Advanced chronic kidney disease | 2.08 (1.75–2.46) | <0.001 | 1.13 (1.01–1.26) | 0.042 | 1.25 (1.07–1.47) | 0.006 | |

| Malignant neoplasm | 2.23 (1.98–2.50) | <0.001 | 1.46 (1.32–1.60) | <0.001 | 1.70 (1.48–1.96) | <0.001 | |

| Metastatic cancer | 7.59 (6.54–8.82) | <0.001 | 2.19 (1.96–2.45) | <0.001 | 2.13 (1.81–2.50) | <0.001 | |

| Dementia | 5.49 (4.74–6.37) | <0.001 | 1.72 (1.59–1.87) | <0.001 | 2.10 (1.89–2.34) | <0.001 | |

| Delirium | 2.34 (2.09–2.62) | <0.001 | 1.45 (1.35–1.56) | <0.001 | 1.87 (1.69–2.07) | <0.001 | |

| Falls / difficulty in walking | 1.97 (1.71–2.26) | <0.001 | 1.11 (1.02–1.22) | 0.017 | 0.99 (0.88–1.12) | 0.911 | |

| Protein-energy malnutrition | 1.81 (1.66–1.97) | <0.001 | 1.42 (1.34–1.52) | <0.001 | 1.38 (1.26–1.50) | <0.001 | |

| Religion | Christian Protestant | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |||

| Christian Catholic | 0.66 (0.60–0.73) | <0.001 | 0.89 (0.83–0.95) | <0.001 | 0.87 (0.79–0.96) | 0.004 | |

| Muslim | 0.29 (0.23–0.36) | <0.001 | 0.79 (0.66–0.94) | 0.009 | 0.99 (0.76–1.29) | 0.935 | |

| Other | 0.49 (0.40–0.60) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.76–1.02) | 0.084 | 0.76 (0.60–0.95) | 0.017 | |

| Without/unknown | 0.70 (0.62–0.79) | <0.001 | 0.97 (0.89–1.06) | 0.493 | 1.10 (0.97–1.24) | 0.127 | |

| Length of stay (per 1-day increase) | 1.012 (1.009–1.015) | <0.001 | 1.009 (1.007–1.011) | <0.001 | 1.012 (1.009–1.015) | <0.001 | |

| ICU or IMCU stay (yes vs no) | 1.40 (1.28–1.52) | <0.001 | 1.43 (1.33–1.54) | <0.001 | 0.99 (0.88–1.11) | 0.863 | |

ICU no: Do Not Admit to intensive care unit; IMCU no: Do Not Admit to intermediate care unit.

Figure 3Limitation of therapeutic efforts according to age group. DNR: Do Not Resuscitate; ICU no: Do Not Admit to intensive care unit; IMCU no: Do Not Admit to intermediate care unit; LTE: limitation of therapeutic efforts.

The comorbidities most often associated with limitation of therapeutic efforts were metastatic cancer, with ORs for Do Not Resuscitate, Do Not Admit to ICU and Do Not Admit to IMCU of 7.59, 2.19 and 2.13, respectively, followed by dementia with ORs of 5.49, 1.72 and 2.10, respectively. COPD was associated with more Do Not Resuscitate and Do Not Admit to ICU codes, but not with the Do Not Admit to IMCU limitation. Multimorbidity was associated with more limitations of therapeutic efforts as the OR (95% CI) for each additional diagnosis was 2.18 (2.08–2.28), 1.34 (1.30–1.38) and 1.42 (1.36–1.47) for Do Not Resuscitate, Do Not Admit to ICU and Do Not Admit to IMCU, respectively.

Considering sociodemographic factors, male sex was associated with significantly less limitation of therapeutic efforts with ORs for Do Not Resuscitate, Do Not Admit to ICU and Do Not Admit to IMCU of 0.66, 0.83 and 0.84, respectively. Compared to Christian Protestants, Muslim patients had fewer Do Not Resuscitate codes and Do Not Admit to ICU orders, but equivalent Do Not Admit to IMCU orders with ORs of 0.29, 0.79 and 0.99, respectively, while Christian Catholics were statistically associated with a lower likelihood of all limitations of therapeutic efforts: 0.66, 0.89 and 0.87, respectively.

Finally, spending time in the ICU or IMCU during the same hospitalisation was associated with a higher likelihood of Do Not Resuscitate and Do Not Admit to ICU codes with ORs of 1.40 and 1.43, respectively, but not with the Do Not Admit to IMCU limitation.

The incidence of in-hospital new Do Not Resuscitate codes was 18.6% (SD: 18.1–19.2%) of the 18,844 hospital stays coded “full-code” on admission. Factors associated with new Do Not Resuscitate codes were older age with an OR of 21.6 for the >85 year age group compared to the 56–65 year age group, any comorbid condition especially metastatic cancer (OR: 4.19) and dementia (OR: 2.61), and stay in ICU or IMCU during the hospitalisation (OR: 1.55). Male sex (OR: 0.82) and Muslim religion (OR: 0.64) were associated with a lower likelihood of attribution of a new Do Not Resuscitate code (table 3).

Table 3Factors associated with new Do Not Resuscitate codes (multivariate analysis), Lausanne University Hospital, 2013–2023, n = 3514. Statistical analysis by logistic regression; results are expressed as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

| Full code ➪ Do Not Resuscitate | p-value | ||

| Year of admission (one year increase) | 1.08 (1.06–1.10) | <0.001 | |

| Age categories | 18–25 | 0.17 (0.08–0.34) | <0.001 |

| 26–35 | 0.38 (0.25–0.57) | <0.001 | |

| 36–45 | 0.48 (0.36–0.64) | <0.001 | |

| 46–55 | 0.84 (0.69–1.01) | 0.059 | |

| 56–65 | 1 (ref) | ||

| 66–75 | 2.08 (1.81–2.38) | <0.001 | |

| 76–85 | 5.42 (4.71–6.23) | <0.001 | |

| 85+ | 21.6 (18.0–26.0) | <0.001 | |

| Male vs female | 0.82 (0.75–0.89) | <0.001 | |

| Diagnoses | COPD | 1.52 (1.35–1.71) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 1.48 (1.33–1.64) | <0.001 | |

| Alcohol-related cirrhosis | 1.51 (1.22–1.87) | <0.001 | |

| Non-alcohol-related cirrhosis | 1.37 (1.11–1.69) | 0.003 | |

| Advanced chronic kidney disease | 1.39 (1.15–1.68) | 0.001 | |

| Malignant neoplasm | 1.66 (1.45–1.90) | <0.001 | |

| Metastatic cancer | 4.20 (3.58–4.91) | <0.001 | |

| Dementia | 2.61 (2.17–3.14) | <0.001 | |

| Delirium | 1.74 (1.52–2.00) | <0.001 | |

| Falls / difficulty in walking | 1.44 (1.19–1.74) | <0.001 | |

| Protein-energy malnutrition | 1.61 (1.45–1.78) | <0.001 | |

| Religion | Christian Protestant | 1 (ref) | |

| Christian Catholic | 0.92 (0.83–1.01) | 0.085 | |

| Muslim | 0.64 (0.51–0.81) | <0.001 | |

| Other | 0.91 (0.74–1.11) | 0.353 | |

| …Without/unknown | 1.01 (0.89–1.15) | 0.910 | |

| Length of stay (per 1-day increase) | 1.016 (1.013–1.019) | <0.001 | |

| ICU or IMCU stay (Yes vs No) | 1.54 (1.39–1.71) | <0.001 | |

ICU: intensive care unit; IMCU: intermediate care unit.

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic did not appear to be a significant determinant in the prevalence of limitation of therapeutic efforts. The monthly evolution of limitation of therapeutic efforts between 2018 and 2023 showed episodic acute rise of the prevalence of limitation of therapeutic efforts unrelated to pandemic waves and already happening before the pandemic (appendix figure S1). The prevalence of all limitation of therapeutic efforts rose during the pandemic period and continued to rise afterwards (appendix table S4).

Our study shows that the prevalence of limitation of therapeutic efforts rose between 2013 and 2023. While Do Not Resuscitate codes were already highly prevalent in 2013 and rose only slightly, we found a remarkably large increase in limitation of admission to ICU (7-fold increase) and IMCU (18-fold increase). Previous studies in other countries have shown an increase in Do Not Intubate orders over the same period in specific acute settings such as stroke [27] or acute respiratory failure [26]. To our knowledge, our study is the first to show such results in an “all-comers” hospital internal medicine population. As the mean age at admission of the patients and the age distribution were stable over the studied period, population ageing cannot be considered as a reason for this significant rise in limitation of therapeutic efforts.

Limitations of therapeutic efforts are usually welcomed by patients with terminal illnesses who are expected to die in the following days or weeks, but they are harder to take into consideration for doctors, patients or relatives in case of chronic illnesses, where patients can expect to live many years in the absence of an acute critical event. Our results suggest that there may be an increasing awareness in both the general population and among doctors to the limited capacity of recovery of the oldest multimorbid patients after intensive and invasive treatments, and that high-intensity treatments should not be offered blindly to every patient. Recent recommendations on decisions of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, intensive-care interventions and futility by ethical societies, such as the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences [10, 28, 29], might have had an impact on medical positioning. Further studies are needed at national and international levels to see if the evolution observed in our centre is comparable in other hospitals, and correlates to local or general cultural evolution around end-of-life goals of care.

Another factor that might have impacted Do Not Admit to ICU and Do Not Admit to IMCU prevalence is the change in the documentation process that happened in our hospital in mid-2018, namely the new possibility of documenting ICU and IMCU “Yes” in the folder. This might have nudged the physicians to fill in the ICU or IMCU “No” option to provide precision on the adequate level of care in case of a critical event.

Finally, the progressive rise in the prevalence of limitation of therapeutic efforts was not associated with a corresponding decline in ICU or IMCU admissions over the study period. However, Do Not Resuscitate and Do Not Admit to ICU orders are more prevalent in case of ICU or IMCU stays, probably because limitation of therapeutic efforts are often discussed and decided on during or after an ICU or IMCU stay, to prevent ICU readmissions. The impact of limitation of therapeutic efforts documentation on ICU or IMCU admissions and re-admissions should be studied through dedicated research.

Older age was clearly the strongest factor associated with each limitation of therapeutic efforts, with an important and continuous rise of Do Not Resuscitate, Do Not Admit to ICU and Do Not Admit to IMCU for each decade over 65 years old. The extremely high prevalence of Do Not Resuscitate codes in the population aged over 85 might raise ethical interrogations. Indeed, recent guidelines from the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine stated that chronological age should not be used alone as a criterion to limit life-sustaining care and ICU admission [30]. On the other hand, ICU admission was not restricted to >60% of this age group, and prognosis in case of in-hospital cardiac arrest is very poor for elderly patients [31], in particular for frail patients [6, 7]. As frailty is not documented as such, but was assessed through other comorbidities, this might be a confounding factor, as an important proportion of the >85-year-old patients hospitalised in our internal medicine department might be ≥5/9 on the clinical frailty scale.

Unsurprisingly, each comorbid condition was associated with more limitation of therapeutic efforts, especially terminal progressive diseases such as metastatic cancer and dementia. On the other hand, COPD co-diagnosis was associated with more Do Not Resuscitate and Do Not Admit to ICU codes, but not with the IMCU admission limitation, which is consistent with the worse prognosis of these patients in case of endotracheal intubation, but with the better prognosis in case of acute non-invasive ventilation requirement [24, 32]. These elements argue that the impact of the medical evaluation is an important factor in the determination of limitation of therapeutic efforts.

Social factors also have an important role in the acceptance or choice of limitation of therapeutic efforts by the patient. Christian Catholics and Muslim patients were less likely to have Do Not Resuscitate or Do Not Admit to ICU codes than Christian Protestants. This contrasts with a previous study in the Swiss general population which showed no association between religion and resuscitation preferences [3], but is in line with another Swiss in-hospital study, which showed that non-Christian religion was associated with more full-code status in patients with medical cardiopulmonary resuscitation futility [33]. Religion’s impact on limitation of therapeutic efforts has been described in other countries [27, 34], but most studies compared “being religious” to “not being religious”, or one religion to the general population. One study assessed the influence of various religions on end-of-life decision (withdrawing versus withholding) in European ICUs [35]. To our knowledge, our study is the first to describe limitation of therapeutic effort differences in medical wards between multiple religions. However, as religion status is based on administrative records, these results might not reflect the characteristics of actively religious patients.

Sex differences for Do Not Resuscitate codes have already been observed in other studies [33, 36]. We, here, confirm that male patients are less likely to have a Do Not Resuscitate code and observe that they are also less likely to have other limitations of therapeutic efforts. We could hypothesise that in our Western culture, limitation of therapeutic efforts can be viewed as a “weakness” that could be less “masculine”, and that female patients would be more inclined to favour relation and palliative care than invasive technical medicine. Doctors might also be influenced by patient’s sex and offer less invasive treatments to female patients, a reason evoked in a large study in the ICU showing that they were less likely to receive organ support and had more limitation of therapeutic efforts than male patients [37]. However, these hypotheses should be addressed through dedicated research.

Almost one in five patients admitted with a full code received a Do Not Resuscitate order during the hospital stay. Factors associated with new Do Not Resuscitate codes were the same as those related to limitation of therapeutic effort attribution. This highlights the fact that hospitalisation is a crucial moment to define end-of-life goals. Indeed, even though they are recommended, written advanced directives are rare in Switzerland [2]. The choice of a Do Not Resuscitate code might be facilitated by the observation of the functionality of the patient, the experience of hospital internists in taking care of acute or post-acute situations and the time available for discussion in the hospital, which help evaluate and explain prognosis in case of a critical illness.

Contrary to our hypothesis that the prevalence of limitation of therapeutic efforts was higher during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, considering the ICU bed limitation and potential triage strategies, we could not identify a direct impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on the evolution of the prevalence of limitation of therapeutic efforts. The observation that the prevalence of limitation of therapeutic efforts continued to rise during and after the pandemic period argues against any open triage strategy. The increase in prevalence of limitation of therapeutic efforts had already started before the pandemic and might be due to public and medical awareness of the impact of ICU treatments. We can hypothesise that the rise in the prevalence of limitation of therapeutic efforts during and after the pandemic might also have been favoured by the significant public awareness of ICU bed limitation and consequences of critical illness, which might have encouraged the acceptance of Do Not Admit to ICU orders.

Our study has several strengths. Its large sample size, with few exclusions, provides a representative view of everyday clinical practice and prevalence of documented limitation of therapeutic efforts in internal medicine wards. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate limitation of therapeutic efforts other than Do Not Resuscitate in a global hospital internal medicine population. Finally, this study advances understanding of the factors that might encourage the establishment of limitation of therapeutic efforts in a hospital setting. It can be a base to develop further research to understand the real impact of the different factors on the limitation of therapeutic efforts, and to create decision-support tools to implement patient-centred therapeutic goals.

Our study also has several limitations. First, its single-centre design precludes its generalisation to other settings or countries. Second, even though we could find associations between different factors and limitation of therapeutic efforts, we cannot prove a direct implication and don’t know the real motives for the establishment or refusal of a limitation of therapeutic efforts. Third, given that our study was based on analysis of electronic medical records, there might be a documentation bias for the limitation of therapeutic efforts other than Do Not Resuscitate. Indeed, as Do Not Admit to ICU and Do Not Admit to IMCU limitations do not have to be mandatorily documented, it could lead to an underestimation of their prevalence, and the rise in prevalence could be partially explained by an improvement in documentation of limitation of therapeutic efforts rather than patients’ or medical decisions. However, we think that this was documented in the medical record for patients for whom it was the most important to specify such limitations. Fourth, as Do Not Intubate orders are not specifically documented in our hospital wards, we were limited to evaluating the Do Not Admit to ICU limitation, which renders comparison to other studies difficult. However, considering the level of life-sustaining care available in our IMCU, a Do Not Admit to ICU order is comparable to a Do Not Intubate order. Finally, residual confounding cannot be excluded, as several socioeconomic characteristics of the patients and their relatives were unavailable. Also, some groups were relatively small and led to large estimations and confidence intervals, although the magnitude of the latter (i.e. the large ORs among elderly) was comparable to that of other published studies [33].

The prevalence of the limitation of therapeutic efforts Do Not Resuscitate, Do Not Admit to ICU and Do Not Admit to IMCU in a hospital internal medicine population increased significantly between 2013 and 2023. Older age, metastatic cancer and dementia are associated with a higher likelihood of limitation of therapeutic efforts, while demographic and cultural variables such as male sex and religion other than Christian Protestant are associated with a lower likelihood of limitation of therapeutic efforts. Further research should be carried out to understand the real impact of these factors on the decision of establishing limitation of therapeutic efforts.

The data that support the findings of this study (study protocol, individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this article, after deidentification) are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author for investigators whose purposed used has been approved by an ethics committee, for five years after publication of this article. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

The statistical code used to analyse the data is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Author contributions: MB: conceptualisation; investigation; methodology; writing – original draft. CS: supervision; writing – review and editing. PV: writing – review and editing. PMV: data curation; formal analysis; writing – review and editing.

The authors declare that they did not use generative AI when writing the manuscript.

This study received no funding.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript was disclosed.

1. Borsellino P. Limitation of the therapeutic effort: ethical and legal justification for withholding and/or withdrawing life sustaining treatments. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2015 Feb;10(1):5.

2. Vilpert S, Borrat-Besson C, Maurer J, Borasio GD. Awareness, approval and completion of advance directives in older adults in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2018 Jul;148(2930):w14642.

3. Gross S, Amacher SA, Rochowski A, Reiser S, Becker C, Beck K, et al. “Do-not-resuscitate” preferences of the general Swiss population: results from a national survey. Resusc Plus. 2023 Apr;14:100383.

4. Mehta AB, Walkey AJ, Curran-Everett D, Matlock D, Douglas IS. Stability of Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders in Hospitalized Adults: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Crit Care Med. 2021 Feb;49(2):240–9.

5. Chevaux F, Gagliano M, Waeber G, Marques-Vidal P, Schwab M. Patients’ characteristics associated with the decision of “do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation” order in a Swiss hospital. Eur J Intern Med. 2015 Jun;26(5):311–6.

6. Fernando SM, McIsaac DI, Rochwerg B, Cook DJ, Bagshaw SM, Muscedere J, et al. Frailty and associated outcomes and resource utilization following in-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2020 Jan;146:138–44.

7. Ibitoye SE, Rawlinson S, Cavanagh A, Phillips V, Shipway DJ. Frailty status predicts futility of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in older adults. Age Ageing. 2021 Jan;50(1):147–52.

8. O’Brien H, Scarlett S, Brady A, Harkin K, Kenny RA, Moriarty J. Do-not-attempt-resuscitation (DNAR) orders: understanding and interpretation of their use in the hospitalised patient in Ireland. A brief report. J Med Ethics. 2018 Mar;44(3):201–3.

9. Osinski A, Vreugdenhil G, de Koning J, van der Hoeven JG. Do-not-resuscitate orders in cancer patients: a review of literature. Support Care Cancer. 2017 Feb;25(2):677–85.

10. Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences. Decisions on cardiopulmonary resuscitation. [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.samw.ch/dam/jcr:782d6eef-014a-45c0-8f2b-be22e160eeff/guidelines_sams_resuscitation.pdf

11. Mentzelopoulos SD, Couper K, Voorde PV, Druwé P, Blom M, Perkins GD, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: ethics of resuscitation and end of life decisions. Resuscitation. 2021 Apr;161:408–32.

12. Andersen LW, Holmberg MJ, Berg KM, Donnino MW, Granfeldt A. In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Review. JAMA. 2019 Mar;321(12):1200–10.

13. Marquis JF. [Hospitalizations involving an intensive care unit stay, from 2014 to 2021] [Internet]. Office fédéral de la statistique (BFS); 2023 Mar. French. Available from: https://dam-api.bfs.admin.ch/hub/api/dam/assets/24468657/master

14. Barrett ML, Smith MW, Elixhauser A, Honigman LS, Pines JM. Utilization of Intensive Care Services, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #185. [Internet]. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD; 2014 Dec. Available from: http://www.hcupus.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb185-Hospital-Intensive-Care-Units-2011.pdf

15. Hurst SA, Perrier A, Pegoraro R, Reiter-Theil S, Forde R, Slowther AM, et al. Ethical difficulties in clinical practice: experiences of European doctors. J Med Ethics. 2007 Jan;33(1):51–7.

16. Ramos JG, Ranzani OT, Perondi B, Dias RD, Jones D, Carvalho CR, et al. A decision-aid tool for ICU admission triage is associated with a reduction in potentially inappropriate intensive care unit admissions. J Crit Care. 2019 Jun;51:77–83.

17. Herridge MS, Azoulay É. Outcomes after Critical Illness. N Engl J Med. 2023 Mar;388(10):913–24.

18. Muscedere J, Waters B, Varambally A, Bagshaw SM, Boyd JG, Maslove D, et al. The impact of frailty on intensive care unit outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2017 Aug;43(8):1105–22.

19. Munshi L, Dumas G, Rochwerg B, Shoukat F, Detsky M, Fergusson DA, et al. Long-term survival and functional outcomes of critically ill patients with hematologic malignancies: a Canadian multicenter prospective study. Intensive Care Med. 2024 Apr;50(4):561–72.

20. Levesque E, Saliba F, Ichaï P, Samuel D. Outcome of patients with cirrhosis requiring mechanical ventilation in ICU. J Hepatol. 2014 Mar;60(3):570–8.

21. Nyström H, Ekström M, Berkius J, Ström A, Walther S, Inghammar M. Prognosis after Intensive Care for COPD Exacerbation in Relation to Long-Term Oxygen Therapy: A Nationwide Cohort Study. COPD. 2023 Dec;20(1):64–70.

22. Damps M, Gajda M, Stołtny L, Kowalska M, Kucewicz-Czech E. Limiting futile therapy as part of end-of-life care in intensive care units. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2022;54(3):279–84.

23. Zhu B, Chen X, Li W, Zhou D. Effect of Alzheimer Disease on Prognosis of Intensive Care Unit (ICU) Patients: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis. Med Sci Monit. 2022 Apr;28:e935397.

24. Wilson ME, Majzoub AM, Dobler CC, Curtis JR, Nayfeh T, Thorsteinsdottir B, et al. Noninvasive Ventilation in Patients With Do-Not-Intubate and Comfort-Measures-Only Orders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. 2018 Aug;46(8):1209–16.

25. Meaudre E, Nguyen C, Contargyris C, Montcriol A, d’Aranda E, Esnault P, et al. Management of septic shock in intermediate care unit. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2018 Apr;37(2):121–7.

26. Wilson ME, Mittal A, Karki B, Dobler CC, Wahab A, Curtis JR, et al. Do-not-intubate orders in patients with acute respiratory failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2020 Jan;46(1):36–45.

27. Yeh HL, Hsieh FI, Lien LM, Kuo WH, Jeng JS, Sun Y, et al.; Taiwan Stroke Registry Investigators. Patient and hospital characteristics associated with do-not-resuscitate/do-not-intubate orders: a cross-sectional study based on the Taiwan stroke registry. BMC Palliat Care. 2023 Sep;22(1):138.

28. Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences. Intensive-care interventions [Internet]. 2013. Available from: https://www.samw.ch/dam/jcr:99239135-d7e9-4dbd-bcc8-7d55511641ea/guidelines_sams_intensiv_care_2013.pdf

29. Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences. Ineffectiveness and unlikelihood of benefit: dealing with the concept of futility in medicine [Internet]. Swiss Academies of Arts and Sciences; 2021 Nov. Available from: https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.5543448

30. Beil M, Alberto L, Bourne RS, Brummel NE, de Groot B, de Lange DW, et al. ESICM consensus-based recommendations for the management of very old patients in intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2025 Feb;51(2):287–301.

31. Nolan JP, Soar J, Smith GB, Gwinnutt C, Parrott F, Power S, et al.; National Cardiac Arrest Audit. Incidence and outcome of in-hospital cardiac arrest in the United Kingdom National Cardiac Arrest Audit. Resuscitation. 2014 Aug;85(8):987–92.

32. Azoulay E, Kouatchet A, Jaber S, Lambert J, Meziani F, Schmidt M, et al. Noninvasive mechanical ventilation in patients having declined tracheal intubation. Intensive Care Med. 2013 Feb;39(2):292–301.

33. Becker C, Manzelli A, Marti A, Cam H, Beck K, Vincent A, et al. Association of medical futility with do-not-resuscitate (DNR) code status in hospitalised patients. J Med Ethics. 2021 Jan;47(12):e70–70.

34. Zhang Z, Weinberg A, Hackett A, Wells C, Shittu A, Chan C, et al. Sociodemographic Factors Associated with Do-Not-Resuscitate Order Utilization in the Surgical Intensive Care Unit: An Observational Study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2023 Nov;40(11):1212–5.

35. Schefold JC, Ruzzante L, Sprung CL, Gruber A, Soreide E, Cosgrove J, et al.; ETHICUS II Study Group. The impact of religion on changes in end-of-life practices in European intensive care units: a comparative analysis over 16 years. Intensive Care Med. 2023 Nov;49(11):1339–48.

36. Crosby MA, Cheng L, DeJesus AY, Travis EL, Rodriguez MA. Provider and Patient Gender Influence on Timing of Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders in Hospitalized Patients with Cancer. J Palliat Med. 2016 Jul;19(7):728–33.

37. Modra LJ, Higgins AM, Pilcher DV, Bailey M, Bellomo R. Sex Differences in Vital Organ Support Provided to ICU Patients. Crit Care Med. 2024 Jan;52(1):1–10.

The appendix is available in the pdf version of the article at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4477.