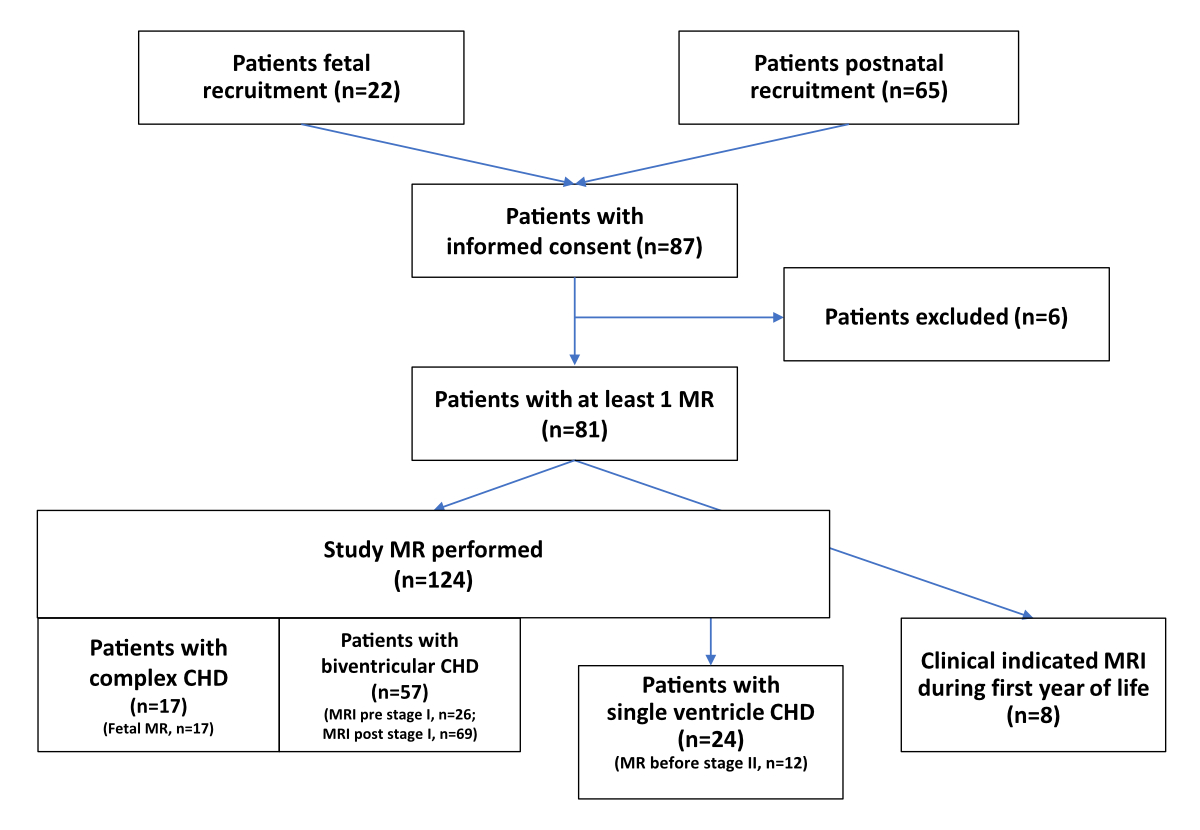

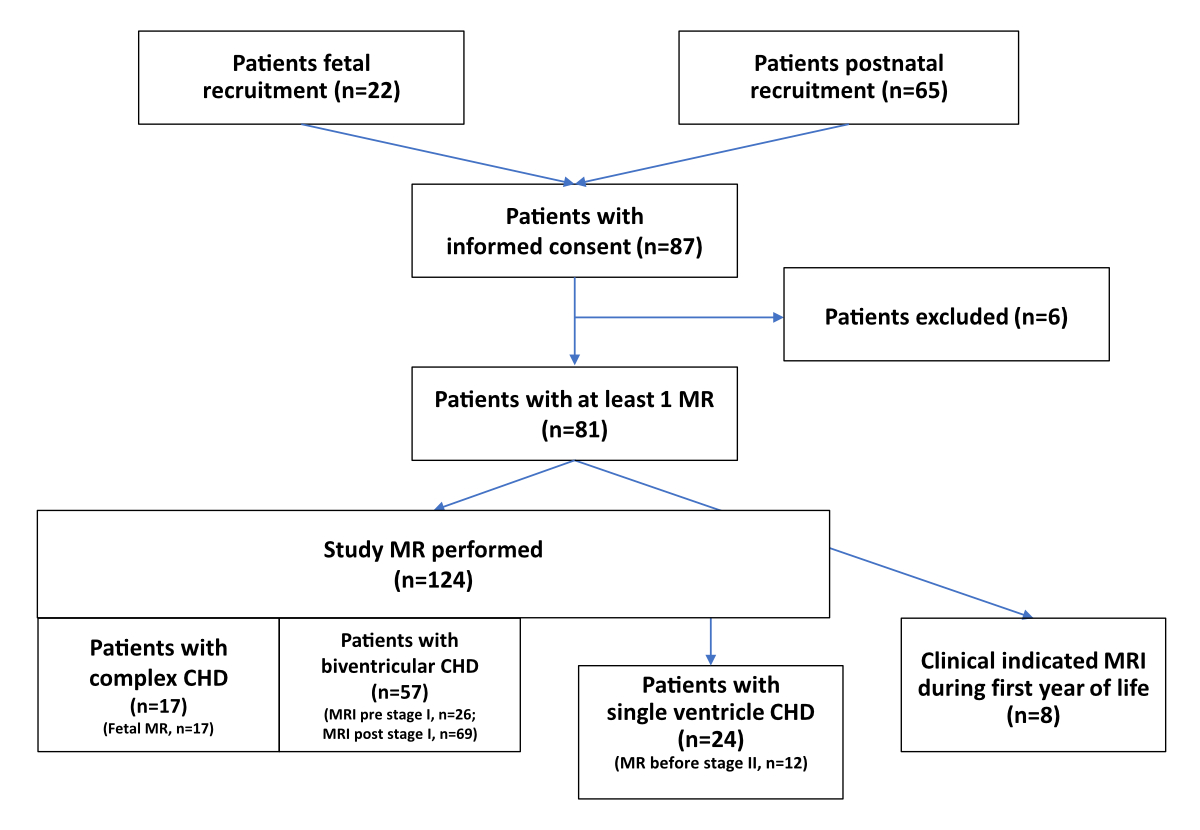

Figure 1Flowchart of patients recruited for brain magnetic resonance (MR) acquisition.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4466

Neurodevelopmental outcomes in high-risk populations, such as preterm infants [1–3] and neonates with complex types of congenital heart disease, remain a major concern [4, 5]. For the congenital heart disease population, multiple factors contribute at various time points to impaired long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes. During foetal life, evidence suggests an increased risk of impaired brain growth and development beginning in utero due to altered haemodynamic physiology [6, 7], and due to an altered maternal-foetal environment with placental dysfunction [8], besides genetic factors and associated extracardiac comorbidities [9]. After birth, this process is further exacerbated by the need for early medical interventions, including neonatal invasive procedures and cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) [10], which are followed by postoperative residual cardiac haemodynamic lesions, low cardiac output syndrome, long-term need for cardiac intensive care including inotropic support, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), ventilation, sedation, infection and pain management [11]. This often leads to long hospital stays with further psychosocial side effects such as parental stress [12] and disrupted parental-child relationship [13], which is often correlated with lower socioeconomic status [14].

Within this multifactorial aetiology of impaired neurodevelopmental outcome in patients with complex congenital heart disease, there is growing evidence that brain development and brain growth are impaired, and that this process starts during the second trimester of pregnancy. This is related to an altered cerebral perfusion leading to impaired oxygen and nutritive supply to the growing brain [15] and continues after birth [16]. Recently, it has been shown that impaired foetal haemodynamics may affect early survival after birth and lead to impaired neurodevelopmental outcome [6]. Therefore, following brain development by serial cerebral neuroimaging using MRI is an important diagnostic approach to better understand the potential impact on neurodevelopmental outcome [17]. Furthermore, potential neuroprotective measures to overcome impaired brain development as a modifiable factor influencing the neurodevelopmental outcome may become an important future direction [18].

In Switzerland, clinical neurodevelopmental outcome programmes exist, such as the Swiss Neonatal Network & Follow-up Group (SwissNeoNet) for a high-risk population of preterm infants, and have been recently established for the congenital heart disease population, for example the Outcome Registry for Children with Severe Congenital Heart Disease (ORCHID) [19]. While the Swiss ORCHID systematically collects cardiac, surgical, intensive care and neurodevelopmental follow-up data, a standardised longitudinal neuroimaging programme for this high-risk population has not yet been included [20].

Therefore, we aimed to systematically assess longitudinal serial magnetic resonance for the high-risk congenital heart disease patients, determining brain development and growth beginning at the last trimester of foetal life, followed by two neonatal perioperative timepoints, before and after the first surgical procedure (stage I), up to a last timepoint before stage II at 3 to 4 months of age (stage II in case of staged palliation for single ventricle congenital heart disease) (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04233775).

This interim analysis aimed to evaluate the study feasibility and first experiences during the establishment of a multicentre magnetic resonance neuroimaging programme, starting at foetal life until the first year of age, covering the most critical period of brain development. We also report on the feasibility and potential limitations of this magnetic resonance neuroimaging programme and the results of the interim analysis of cerebral MRI findings, quantitative measurements and neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Here we report an interim analysis of a prospective multicentre observational study on altered cerebral growth and development in infants with a complex type of congenital heart disease (SNFS 320030_184932). This study was designed as an observational study focusing on brain development from the third trimester of foetal life to one year of age. Participating centres were, in Switzerland, the University Children’s Hospital Zurich, University Hospital Bern, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois in Lausanne; and, in Germany, the Paediatric Heart Centre Giessen and the German Heart Centre Munich. We analysed data of patients included from April 2020 to September 2023. We defined cerebral developmental trajectories, brain growth and time course of brain abnormalities as primary outcome measures and the neurodevelopmental outcome at one year of age as the secondary outcome measure.

The inclusion criteria were patients with severe types of congenital heart disease with the need for neonatal cardiopulmonary bypass surgery or catheter-related procedures within the first six weeks of life (stage I). This encompassed all consecutive and eligible congenital heart disease patients under clinical and haemodynamical stable conditions undergoing biventricular repair, such as arterial switch operation (ASO) for d-transposition of the great arteries (D-TGA) or single ventricle type of congenital heart disease undergoing staged palliation such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome with Norwood stage I procedure followed by bidirectional cava-pulmonary (Glenn) anastomosis (stage II) and Fontan completion (stage III). Patients were recruited during foetal life after cardiac diagnosis had been made by foetal echocardiography or after birth if cardiac diagnosis was made after birth. Due to the high frequency of patients with extracardiac comorbidities, we also included patients with associated genetic anomalies. Furthermore, we recruited healthy controls during foetal life for foetal and postnatal MRI scans. We approached parents or caregivers of patients with a request to participate in the study during the foetal and postnatal period. We also analysed the participation rate at the different timepoints and the reasons for non-participation. Written informed consent was obtained from all parents or caregivers. Exclusion criteria were: patients whose parents or caregivers did not give informed consent, patients with haemodynamic instability and patients with permanent pacemaker or for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, both situations incompatible for cerebral MRI.

Serial brain MRI was scheduled at four timepoints: (1) at 32 ± 2 weeks of gestational age during the foetal period, (2) after birth, before the first invasive procedure (stage I), (3) after the first invasive procedure and (4) before stage II in case of single ventricle palliation. The second and third MRI were performed in natural sleep. The fourth cerebral MRI was conducted under general anaesthesia, combined with cardiac diagnostic catheterisation. We supervised the mothers during foetal cerebral MRI and monitored the infants scanned in natural sleep by electrocardiogram and pulse oximetry. Patients under general anaesthesia were accompanied and monitored by an anaesthesiology team. Noise protection during magnetic resonance was achieved with foam earplugs and earmuffs.

Data from clinically indicated brain MRI scans conducted in the first year of life were also included. Magnetic resonance analysis for this work was performed at the predefined timepoints of this study only.

The following cerebral MRI scanners were used: in Zurich, a 1.5 T GE Signa Discovery MR450 (upgraded to a GE Signa Artist during the study) for foetal scans and a 3 T GE Discovery MR750 MRI scanner using an 8-channel head coil for postnatal scans; in Bern, a 1.5 T Siemens Magnetom Aera for foetal scans and a Siemens 3 T Magnetom Skyra fit for postnatal scans; in Giessen, a 3 T Siemens Magnetom Verio for postnatal scans; in Munich, a 1.5 T Siemens Magnetom Avanto for postnatal scans; and in Lausanne, a Siemens 3 T Prisma scanner for foetal and postnatal scans.

The foetal cerebral MRI scanning protocols included T2-weighted single-shot sequences in three planes (double acquisition due to foetal movement), a T1-weighted sequence in one plane and diffusion tensor imaging. The postnatal magnetic resonance scanning protocols included T2-weighted fast-spin-echo sequences in three planes, a 3D T1-weighted sequence, diffusion tensor imaging, single-voxel short TE magnetic resonance spectroscopy and pseudo-continuous Arterial Spin Labelling (pcASL) sequences (table S1 in the appendix). The MRI scans were analysed at the participating centres or by the paediatric neuroradiologist in the main centre.

Structural cerebral MRI findings were systematically assessed by an experienced paediatric magnetic resonance specialist for the presence of cerebral lesions, and the lesions were categorised according to Stegeman [21] into white matter injury, ischaemic cerebral lesions, intracranial haemorrhage, i.e. intraventricular and subdural haemorrhages, and other lesions, i.e. intraparenchymal cerebral/cerebellar haemorrhages, signs of hypoxic-ischaemic injuries, sinus venous thrombosis and other pathological findings.

To quantify the total brain volume and cerebral tissue volumes for each patient, T2-weighted images were used, which were reconstructed into a single, isotropically scaled 3DT2 image using the Slice-to-Volume Reconstruction Toolkit (SVRTK) super-resolution algorithm [22]. The magnetic resonance protocol and parameters have been published previously [23].

Neurodevelopmental outcome at one year was assessed by the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition (Bayley III) for patients and healthy controls [24]. The test includes cognitive, language and motor composite scores (cognitive composite score [CCS], language composite score [LCS], motor composite score [MCS]). American scoring scales were used, for general applicability. Patients and controls were tested at 12 months by an experienced neurodevelopmental paediatrician.

For a subgroup of patients, early 2-to-6 month neurodevelopment was additionally tested after the first cardiac surgery (or catheter procedure) before hospital discharge using the Hammersmith neonatal neurological examination (HNNE) [25], as well as before the stage II procedure in univentricular patients using the Hammersmith infant neurological examination (HINE) [26].

The congenital heart disease diagnosis was made either during foetal life or after birth by Doppler echocardiography. Genetic analysis was performed in those infants where clinical suspicion of an associated genetic comorbidity was evident, but not as routine clinical practice. Standard treatment included postnatal medical intensive care with prostaglandin E2 in case of duct-dependent pulmonary or systemic perfusion and, if needed, ventilation, inotropic support before and after stage I surgery. Types of stage I surgery included, for example, biventricular repair, such as arterial switch operation for neonates with simple d-transposition of the great arteries, aortic arch surgery for severe forms of aortic arch pathology, or Norwood stage I procedure in hypoplastic left heart syndrome in single ventricle palliation. Beyond surgical stage I procedures, alternative catheter procedures to ensure pulmonary perfusion in case of duct-dependency treated by duct-stenting or stenting of a stenotic right ventricular outflow tract were defined as a stage I procedure. A stage II procedure was defined as the bidirectional cava-pulmonary anastomosis (BDCPA) for single ventricle palliation.

Study data were collected continuously from electronic patient records and study case report forms (CRF) and entered in an electronic data capturing tool, REDCap. Parameters included clinical, imaging and outcome data. We report findings and between-group effects or differences based on a categorisation of the sample cohort into groups of healthy controls, patients with biventricular repair and patients with univentricular palliation.

The cantonal ethics committees approved the study protocol for Zurich, Bern and Lausanne in Switzerland (BASEC 2019-01993). Further ethical approval was obtained for Giessen (AZ 272/19) and Munich (321/21 S-EB).

Continuous data are presented as mean and SD for normally distributed data and median and IQR for non-normally distributed data. Categorical data are presented as count and percentage. Normality of distribution was assessed by visual inspection of histograms and Q-Q plots.

A total of 87 patients were included. Patients were recruited during foetal life (n = 22) or after birth (n = 65). Fifteen healthy controls were recruited for magnetic resonance scans during foetal life and after birth. We performed at least one brain MRI in 81 patients in the five participating centres with a total number of 124 MRIs (figure 1). Eight further cerebral magnetic resonance scans were conducted for clinical indications at other timepoints but not included in the analysis for this study. Foetal cerebral imaging data were included from the Swiss participating centres. For healthy controls, we performed 27 MRI scans (15 foetal and 12 postnatal).

Figure 1Flowchart of patients recruited for brain magnetic resonance (MR) acquisition.

In total, 132 cerebral MRIs were performed in 81 patients (figure 1). Timing of MRI was during the foetal period for the congenital heart disease patients (n = 17), after birth before stage I (n = 26) and after stage I (n = 69) resp. before stage II (n = 12). In terms of number of MRI scans, 38 patients had at least two scans, 32 had two scans and 6 had three scans.

Of the 15 healthy control subjects included, all had a foetal MRI (100%) and 12 scans were performed at neonatal age (80%).

Although we had received informed consent, foetal magnetic resonance scans in congenital heart disease patients were acquired only in 73%, after birth before or after stage I in 59% and before stage II in 50% (figure 1).

We approached parents/caregivers of patients with a request to participate in the study during foetal and postnatal period. Our single-centre (Zurich) analysis of patient recruitment rates showed that the timing was influenced by the time of diagnosis and availability of the parents, leading to an informed consent rate of 71%, which was lower before birth (50%) compared to after birth (74%).

After informed consent for the foetal scan, we performed 34 MRIs at different timepoints including postnatal assessment; after postnatal informed consent, we performed 90 MRIs. Reasons for not performing MRI included (1) maternal safety reasons such as preeclampsia, need for bedrest, feeling of discomfort lying in the magnetic resonance scanner leading to secondary refusal; (2) patient safety reasons such as haemodynamic instability, emergency or elective surgery performed earlier, perioperative foetal demise, MRI-incompatible devices (pacemaker, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation), prolonged need for ICU care (ventilation, oxygen and inotropic dependency, protective isolation); and (3) logistical problems including availability of MRI time slots, limited personal and structural resources and late recruitment. Both, logistical problems and late recruitment were the most frequent reasons for not performing a study MRI.

The congenital heart disease diagnoses confirmed at birth were single ventricle congenital heart disease undergoing staged palliative procedures, biventricular congenital heart disease undergoing definitive repair and borderline left ventricle undergoing staged palliative procedures or biventricular repair (table 1).

Table 1Cardiac diagnosis, surgical procedures and outcome of patients with a complex type of congenital heart disease (CHD) and healthy controls at one year of age.

| CHD type | Cardiac diagnosis | Patients (n = ) | Procedure at stage I | Procedure at stage II | Outcome |

| Single ventricle CHD | Hypoplastic left heart syndrome | 7 | Norwood procedure (n = 5); Giessen procedure (n = 2) | BDCPA (n = 5); Norwood + BDCPA (n = 2) | |

| Non-hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) / Hypoplastic left heart complex (HLHC) (others)* | 14 | PAB (n = 5); Norwood (n = 3); PDA stent (n = 3); Aorto-pulmonary shunt procedure (n = 1) | BDCPA (n = 11); Late stage I (n = 1) | Palliative care (n = 2) | |

| Borderline left ventricle | Hypoplastic left heart complex** | 3 | PAB (n = 3) | BDCPA (n = 2) | Palliative care (n = 1) |

| Hypoplastic left heart complex** | 3 | PAB (n = 2); Partial repair (n = 1) | Biventricular repair (n = 3) | ||

| Biventricular CHD | D-TGA simple | 13 | ASO (n = 13) | ||

| D-TGA complex | 16 | ASO + VSD closure (n = 6); Aortic arch repair (n = 7); Other (n = 3) | |||

| Hypoplastic aortic arch, coarctation of the aortic arch or interrupted aortic arch | 3 | Aortic arch repair*** (n = 3) | |||

| Truncus arteriosus communis | 6 | Primary repair (n = 3); Primary PAB (n = 2) | Repair (n = 2) | Palliative care (n = 1) | |

| PA VSD | 3 | Shunt procedure (n = 3) | Repair (n = 3) | ||

| PA IVS | 1 | Catheter-based procedure (n = 1) | |||

| Others**** | 12 | Primary repair (n = 7); PAB (n = 3); Catheter-based procedure (n = 2) | Secondary repair (n = 3) | Palliative care (n = 1) | |

| Total | 81 |

ASO: arterial switch operation; BDCPA: bidirectional cavo-pulmonary anastomosis (Glenn procedure); D-TGA: d-transposition of great arteries; PAB: pulmonary artery banding (central or bilateral); PA IVS: pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum; PA VSD: pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect; PDA: patent ductus arteriosus; RV-PA: right ventricular to pulmonary artery; VSD: ventricular septal defect.

* Non-hypoplastic left heart syndrome / Hypoplastic left heart complex (others) included double inlet left ventricle (n = 4), mitral atresia, left ventricular hypoplasia (n = 2), pulmonary atresia, right ventricular hypoplasia (n = 3), tricuspid atresia, right ventricular hypoplasia (n = 2), heterotaxy syndrome (n = 1), absent pulmonary valve (n = 1) and dysbalanced atrioventricular septal defect (n = 1).

** Hypoplastic left heart complex included borderline left ventricle (n = 3), dysbalanced atrioventricular septal defect with left ventricular hypoplasia (n = 1) and Shone’s complex (n = 2).

*** Types of complex aortic arch surgery included additional aortic valve reconstruction (n = 1) and pulmonary artery banding (n = 1).

**** Other biventricular congenital heart disease included total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVD) (n = 3), aortic atresia (n = 2), Ebstein anomaly (n = 1), critical aortic/pulmonary valve stenosis (n = 2), large ventricular septal defect (n = 1), coronary anomaly (anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery [ALCAPA]) (n = 1) and aorto-pulmonary window (n = 1).

At birth, we included patients with single ventricle congenital heart disease (25.9%), biventricular congenital heart disease (66.7%) and borderline left ventricular congenital heart disease (7.4%). Most patients (95.8%, n = 77) had a cyanotic congenital heart disease. During follow-up after birth, the patients with borderline left ventricle could be corrected by biventricular repair (n = 3), were palliated by staged procedure with stage II (bidirectional cava-pulmonary anastomosis) (n = 2) or died before stage II (n = 1).

According to the Clancy classification for complex congenital heart disease, we analysed patients with two-ventricle congenital heart disease without (Clancy I; n = 37, 45.7%) or with (Clancy II; n = 20, 24.7%) aortic arch obstruction, or with single ventricle congenital heart disease without (Clancy III; n = 10, 12.3%) or with (Clancy IV; n = 14, 17.3%) aortic arch obstruction.

The most frequent congenital heart disease diagnoses were simple (n = 13) or complex type of d-transposition of the great arteries (n = 16), the latter defined as simple d-transposition of the great arteries with additional surgical procedures to arterial switch operation, such as closure of ventricular septal defect, aortic arch repair or other procedures (table 1).

Patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) (n = 7) included different subtypes of HLHS with aortic atresia / mitral atresia (n = 2), aortic atresia / mitral stenosis (n = 1), aortic stenosis / mitral atresia (n = 1) or aortic stenosis / mitral stenosis (n = 3).

The group of patients with hypoplastic left heart complex (HLHC) (n = 6) were defined as borderline left ventricle with small ascending aorta and hypoplastic aortic arch / aortic coarctation (CoA) and included infants with borderline left ventricle (n = 3), Shone complex (n = 2) and dysbalanced atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) with left ventricle hypoplasia (n = 1).

Additional surgical procedures in complex transposition of the great arteries included patch closure of ventricular septal defect (VSD) (n = 6), aortic arch repair (n = 7), patch VSD closure in double outlet right ventricle (DORV) malposition (n = 3), central pulmonary artery banding (PAB) (n = 1), tricuspid valve reconstruction (n = 2), pulmonary artery branch plasty (n = 2), aberrant subclavian artery reimplantation (n = 1) and aorto-pulmonary shunt procedure (n = 1).

Catheter procedures included stenting of patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) (n = 5), balloon dilation of critical aortic resp. pulmonary valve stenosis (n = 2), and perforation of membranous pulmonary atresia (n = 1) postponing cardiopulmonary bypass surgery beyond the neonatal period (n = 5) or definitive repair (n = 2).

In 57 patients, biventricular repair, and in 24 patients, univentricular palliation was intended.

Biventricular repair was successfully performed in 52 of 54 biventricular congenital heart disease patients (two patients deceased) and 3 borderline left ventricle.

Single ventricle palliation until stage II was successfully performed in 18 of 21 single ventricle congenital heart disease patients (2 deceased) and 2 borderline left ventricle (1 deceased). One single ventricle patient had a late stage I procedure, but no stage II procedure until September 2023. Overall, five patients died within the follow-up period until 1 year of age.

Foetal MRI was performed at a median age of 32.6 (IQR: 31.3–33.3) weeks of gestation. After birth, before stage I, MRI was performed within the first week of life at a median age of 6 days (3–16); after stage I at an age of 26.5 days (18.3–40.8) and before stage II at an age of 116 days (94.5–118.5).

Structural cerebral MRI findings are shown in table 2. On the foetal scan, mild structural changes including small structural cystic formations and asymmetric lateral ventricles were commonly reported. After birth, we found white matter injury before resp. new white matter injury after stage I in 3.8 % resp. 8.7%, ischaemic cerebral lesions 11.5% resp. 11.6%, intraventricular haemorrhage in 7.7% resp. 7.2% and subdural haemorrhage 34.6% resp. 26.1%. Before stage II, new intraventricular haemorrhage 9.1% and new subdural haemorrhage 9.1%. Sinus venous thrombosis was described in one patient, while other MRI findings, i.e. cerebellar haemorrhage or intraparenchymal haemorrhage, were not detected in our cohort. Other non-specific cerebral findings included delayed myelination, mildly enlarged lateral ventricles, microhaemorrhages and smaller cerebral volumes.

Table 2Structural cerebral MRI findings with a complex type of congenital heart disease (CHD) and healthy controls at 1 year of age. New findings in post stage I and pre stage II scan were first diagnosed at this timepoint.

| Patients | Patients with single-ventricle CHD (n = 24) | Patients with biventricular CHD (n = 57) | Healthy controls (n = 15) |

| Foetal scan (n = 32) | Foetal scan (n = 6) | Foetal scan (n = 11) | Foetal scan (n = 15) |

| Periventricular pseudocyst | (n = 1) | – | – |

| Arachnoidal cyst | (n = 1) | – | – |

| Asymmetric lateral ventricles (n = 1) | – | – | (n = 2) |

| Plexus choroideus cyst (n = 1) | – | – | (n = 1) |

| Pre stage I scan (n = 38) | Pre stage I scan (n = 7) | Pre stage I scan (n = 19) | Pre stage I scan (n = 12) |

| White matter injury | – | (n = 1) | – |

| Ischaemic cerebral lesions | (n = 1) | (n = 2) | – |

| Intraventricular haemorrhage | (n = 2) | – | – |

| Subdural haemorrhage | (n = 4) | (n = 5) | (n = 4) |

| Other* | – | (n = 5) | – |

| Post stage I scan (n = 69) | Post stage I scan (n = 17) | Post stage I scan (n = 52) | |

| New white matter injury | (n = 2) | (n = 5) | |

| New ischaemic cerebral lesion | (n = 4) | (n = 4) | |

| New intraventricular haemorrhage | (n = 1) | (n = 4) | |

| New subdural haemorrhage | (n = 3) | (n = 15) | |

| New sinovenous thrombosis | – | (n = 1) | |

| Other* | (n = 9) | (n = 18) | |

| Pre stage II scan (n = 12) | Pre stage II scan (n = 12) | ||

| New white matter injury | – | ||

| New ischaemic cerebral lesion | – | ||

| New intraventricular haemorrhage | (n = 1) | ||

| New subdural haemorrhage | (n = 1) | ||

| Other* | (n = 2) |

* Other included MRI findings of delayed myelination, mildly (a)symmetric enlarged lateral ventricles, diffuse smaller cerebral parenchyma, small cavernoma, enlarged internal and external cerebral spinal fluid spaces, microhaemorrhages.

Automated total brain volume measurements were as follows: Before birth: median 228.9 ml (IQR: 213.1–241.2) in biventricular congenital heart disease (n = 6); 194.4 ml (165.3–223.6) in single-ventricle congenital heart disease (n = 3); 196.4 ml (186.4–235.2) in normal healthy controls (n = 15). After birth before stage I: 337.1 ml (310.3–350.2) in biventricular congenital heart disease (n = 15); 331.6 ml (305.9–350.7) in single-ventricle congenital heart disease (n = 5); 406.8 ml (389.9–438.7) in normal healthy controls (n = 12). After stage I: 367.7 ml (341.8–385.5) in biventricular congenital heart disease (n = 38); 353.6 ml (338.2–375.7) in single-ventricle congenital heart disease (n = 15). Before stage II: 514.1 ml (482.9–554.6) in patients with single-ventricle congenital heart disease (n = 9). All values are expressed as median (IQR).

Data on the neurodevelopmental outcome were available after stage I with the Hammersmith test in 30 (48% of 62 patients in Zurich) patients after stage I and 12 (63% of 19 patients undergoing univentricular palliation in Zurich) before stage II.

Preliminary data of Bayley Composite Scores at one year of age were available in 43 congenital heart disease patients (57% of 76 patients surviving until one year of age) and 9 healthy controls (60% of the 15 controls) by the end of September 2023. For preliminary results of the Bayley test, please see table 3.

Table 3Neurodevelopmental outcome in patients with a complex type of congenital heart disease (CHD) and healthy controls at one year of age. Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

| CHD type | Patients with single-ventricle CHD (n = 14) | Patients with biventricular CHD (n = 29) | Healthy controls (n = 9) | |

| Age at test in months | 12.3 ± 1.6 | 12.5 ± 1.8 | 12.1 ± 0.6 | |

| Bayley III | CCS | 92.9 ± 13.1 | 101.2 ± 11.1 | 113.3 ± 5.6 |

| LCS | 88.5 ± 12.0 | 95.7 ± 13.1 | 102.3 ± 7.9 | |

| MCS | 85.6 ± 14.5 | 87.6 ± 18.0 | 100.7 ± 8.2 | |

CCS: cognitive composite score; LCS: language composite score; MCS: motor composite score.

The long-term neurodevelopmental outcome of children with complex types of congenital heart disease (CHD) remains a major challenge and there is still room for improvement [5]. The aetiology of impaired neurodevelopmental outcome is multifactorial including foetal and postnatal factors [27]. Foetal factors are associated with an altered brain development due to an altered brain perfusion depending on the type of congenital heart disease [28]. To assess this, different foetal cardiac and brain imaging techniques, including foetal cerebral ultrasonography, foetal echocardiography and foetal cardiac and brain MRI, are being used in routine clinical practice and as multimodal imaging for research purposes [29]. Here, we reported our first interim results of patients recruited in three centres in Switzerland and two centres in Germany.

In Switzerland, the neurodevelopmental outcome is systematically assessed in various clinical follow-up programmes, such as the Swiss Outcome Registry for Children with Severe Congenital Heart Disease (ORCHID) [19]. Nevertheless, systematic assessment of neuroimaging data is so far not part of this registry. Recent studies show that foetal brain imaging determining reduced foetal cerebral perfusion and oxygenation has become predictive for morbidity and mortality after birth [6]; in addition, smaller foetal brain volumes are associated with impaired neurodevelopmental outcome at two years of age [30]. Therefore, systematically assessing brain development would be valuable in improving neurodevelopmental outcomes by guiding efforts to optimise care for infants at the highest risk of impairment.

Based on our experience, certain limitations must be considered when implementing cerebral MRI in clinical practice. Before birth, we encountered maternal safety issues, such as the need for bedrest and the discomfort felt while lying in the scanner, besides medical contraindications such as preeclampsia. After birth, the haemodynamic instability of the severely ill infants associated with prolonged ICU care due to dependency for ventilation, oxygen and inotropes may make it impossible to scan them due to patient safety reasons. However we found that logistics-based reasons, e.g. limited staff (for accompaniment and sedation of infants during magnetic resonance) and structural resources (magnetic resonance time slots, limitations due to pandemic restrictions), were the most frequent reasons for MRI scans not being done. These factors limited the number of brain MR examinations.

While the informed consent rate was generally over 70%, we still observed lower recruitment rates before birth, which may be attributed to multiple factors. These include the timing of patients’ recruitment before birth during disease coping or secondary refusal during the last trimester as well as after birth during turbulent perioperative course on the ICU. Haemodynamic instability of the patients before or after neonatal cardiac surgery limited the transfer to the magnetic resonance centre and the magnetic resonance scan. Possible solutions to mitigate this limitation would include dedicated neonatal MRI scanning facilities near the NICU, as well as the use of ultra-low-field or other novel portable MR technologies that allow imaging even in cases of haemodynamic instability [31].

Regarding patient attendance rates for neurodevelopmental outcome assessments, our data showed similar rates across different timepoints. Early neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 to 6 months, assessed using the Hammersmith test after stage I and before stage II, were available for up to 60% of patients. Likewise, 1-year neurodevelopmental outcomes, evaluated using the Bayley Composite Scores, were available for up to 57% of patients, comparable to the 60% attendance rate observed in healthy controls as of September 2023.

In Switzerland, the neurodevelopmental outcome should be systematically examined for most children being operated on for severe types of congenital heart disease, starting with a one-year follow-up. For this, the Swiss ORCHID, a nationwide patient registry, systematically collects medical and surgical data on neurodevelopmental outcome since 2019 [19]. So far, neuroimaging data including brain MR imaging are not part of this registry. Nevertheless, we could include a large population of high-risk patients for altered brain development within this study period.

Several other research initiatives and consortia are working to establish prospective neuroimaging programmes for patients with complex congenital heart disease. The Cardiac Neurodevelopmental Outcome Collaborative (CNOC) was founded as an association of more than fifty institutions with clinicians, researchers, patients and families from North America working together to improve neurodevelopmental outcome, mental health and quality of life of patients with congenital heart disease (https://cardiacneuro.org). The European Association Brain in Congenital Heart Disease (EU-ABC) was formed as a research consortium of five large centres in Europe with a research focus on brain imaging and neurodevelopmental outcome in children operated on for complex congenital heart disease [20, 21, 32, 33].

Foetal brain MRI scans revealed mild structural changes including isolated structural cystic malformations and mild asymmetric ventriculomegaly, with very low clinical relevance, even occurring in healthy controls. Studies showed that symmetric ventriculomegaly rather than asymmetric ventriculomegaly and a higher degree of ventriculomegaly was a prognostic predictor for CNS abnormalities [34]. Isolated intracranial cystic malformations not associated with other foetal anomalies were reported to be rather benign in nature, and do not impair physiological neurodevelopment [35].

After birth, we found white matter injuries, ischaemic cerebral lesions and intraventricular bleedings more frequently after than before stage I surgery. Overall, subdural haemorrhages were the most frequent findings in up to 26.1% of the MRI scans before and after surgery. White matter injury and ischaemic cerebral lesions are well described as the predominant lesions visualised before and after neonatal cardiopulmonary bypass for congenital heart disease [36]. In a recent systematic review, the overall prevalence of brain injury before resp. after surgery ranged between 23% to 61% resp. 20% to 79%, with white matter injury as the predominant finding [37]. The lower rates of new postoperative brain lesions found in our study correspond to the described lower frequency of cerebral lesions described by other groups [21] and a trend towards lower prevalence of postoperative white matter injuries over the last two decades due to the optimisation of intraoperative neuroprotection and perioperative intensive care management [38].

Our preliminary total brain volume measurements are consistent with foetal MRI studies that have reported reduced total brain volume beginning at the 25th week of gestation in cases of biventricular congenital heart disease [39], with a continuous and progressive decline in brain growth throughout the third trimester and after birth in both single-ventricle and biventricular congenital heart disease [16, 39]. Of note, the total brain volumes of the healthy controls were obviously smaller despite a comparable timepoint during foetal MR scan, balanced sex distribution, comparable birthweight and no obvious outliers.

The rate of attendance at the clinical neurodevelopmental follow-up at one year of age in our cohort was more than 50%. As a comparison, in larger clinical follow-up programmes such as the Cardiac Neurodevelopmental Outcome Collaborative analysing data from 16 participating centres in the first two years of life, the attendance rate was 29.0%, which may in part be explained by the hospital-initiated scheduling for the neurodevelopmental follow-up appointment as part of a research study [40]. Our preliminary neurodevelopmental outcome results of the analysed Bayley III scales (table 3) are determined at 12 months of age, and were associated with lower values for patients undergoing single ventricle palliation compared to patients undergoing biventricular repair and healthy controls, as described [41]. Nevertheless, our analysis is the first interim analysis and later timepoints may be more accurate with larger impact on differentiating neurodevelopmental outcome of the different congenital heart disease types. Recent studies have shown that in patients with d-transposition of the great arteries (D-TGA), an early cardiac diagnosis – ideally at the foetal stage – positively impacts neonatal brain volume and is associated with better neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18 months of age [42]. Further analyses are needed to determine whether brain MRI can serve as a reliable predictor of neurodevelopmental outcomes [17].

Currently, various cerebral MRI findings are utilised in secondary analyses of the data acquired, including structural brain injuries (such as white matter injury, cerebral ischaemic lesions and haemorrhages), volumetric changes (total or regional brain volumes) and advanced MR techniques that assess microstructural and functional alterations, such as connectomics, structural covariance networks, diffusion tensor imaging and spectroscopy [43]. Despite these efforts, a definitive prognostic MRI parameter serving as a reliable biomarker for neurodevelopmental outcomes is still lacking [17, 37]. Therefore, establishing a serial neuroimaging programme, potentially utilising MRI sequences beyond morphological imaging, may serve as a key foundation for future research and clinical advancements.

By establishing a serial neuroimaging programme, the lead centre was able to collect data on the majority of patients. However, we have also initiated a multicentre network, including three centres in Switzerland and two in Germany, to gain broader insights into the perioperative course of brain development. Despite this progress, we report only interim findings due to the limited number of patients and the pending completion of neurodevelopmental outcome data at 1 year of age.

Further study limitations include a patient selection bias due to the exclusion of haemodynamically unstable patients, who probably may have a more complicated clinical course with impact on brain maturation and neurodevelopmental outcome.

Additional outcome data at 2 and 5 years will provide a more comprehensive understanding of both clinical and neurodevelopmental trajectories. Further analyses will follow as more data become available.

By examining trajectories of foetal-to-postnatal brain development and patient-individual development in longitudinal studies it should be feasible to combine serial neuroimaging programmes with continuous systematic neurodevelopmental outcome follow-up examinations in children with complex congenital heart disease until adulthood. This may lead to a better understanding of the pathomechanism of the impaired neurodevelopmental outcome, which has recently been shown for the high-risk group of preterms until adolescence [44, 45]. Therefore, real life-long longitudinal multicentre studies with long-term neuroimaging and clinical neuromonitoring are necessary at different timepoints, during infancy, toddlerhood, early childhood, school age, adolescence until adulthood to enhance neurodevelopmental and mental health outcome. Nevertheless, a combination of neuroimaging and neuromonitoring may better predict neurological impairment. This includes either near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) or electroencephalography, or combined neuromonitoring systems [46]. The further impact of biochemical neuromarkers predicting neurodevelopmental outcome remains unclear [47]. Furthermore, serial brain MRI is necessary for evaluating the effectiveness of foetal or postnatal neuroprotective interventions which are scheduled including pharmacological (progesterone, allopurinol, erythropoietin) or psychosocial studies (parental stress reduction programmes).

Due to limitations of the ethics committee decision, there are no open science data sharing options.

This work was supported by the Swiss National Foundation (SNFS 320030_184932). We thank Professor Beatrice Latal and Professor Emanuela Valsangiacomo for their support.

Robert Cesnjevar, Zurich; Hitendu Dave, Zurich; Ruth Etter, Zurich; Maria Feldmann, Zurich; Ji Hui, Zurich; Martin Glöckler, Bern; Cornelia Hagmann, Zurich; Alexander Kadner, Bern; Christian Kellenberger, Zurich; Janet Kelly, Zurich; Oliver Kretschmar, Zurich; Thushi Logeswaran, Giessen; Giancarlo Natalucci, Zurich; Thi Dao Nguyen, Zurich; Kelly Payette, Zurich; René Prêtre, Lausanne; Constance Rippel, Lausanne; Beate Rücker, Zurich; Achim Schmitz, Zurich; Nicole Sekarski, Lausanne

This work was supported by the Swiss National Foundation (SNFS 320030_184932).

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript was disclosed.

1. Katz JA, Levy PT, Butler SC, Sadhwani A, Lakshminrusimha S, Morton SU, et al. Preterm congenital heart disease and neurodevelopment: the importance of looking beyond the initial hospitalization. J Perinatol. 2023 Jul;43(7):958–62. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-023-01687-4

2. Agyeman-Duah J, Kennedy S, O’Brien F, Natalucci G. Interventions to improve neurodevelopmental outcomes of children born moderate to late preterm: a systematic review protocol. Gates Open Res. 2021 Sep;5:78. doi: https://doi.org/10.12688/gatesopenres.13246.1

3. Bora S. Beyond Survival: Challenges and Opportunities to Improve Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Preterm Birth in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Clin Perinatol. 2023 Mar;50(1):215–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2022.11.003

4. De Silvestro A, Reich B, Bless S, Sieker J, Hollander W, de Bijl-Marcus K, et al.; European Association Brain in Congenital Heart Disease. Morbidity and mortality in premature or low birth weight patients with congenital heart disease in three European pediatric heart centers between 2016 and 2020. Front Pediatr. 2024 Apr;12:1323430. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2024.1323430

5. Feldmann M, Bataillard C, Ehrler M, Ullrich C, Knirsch W, Gosteli-Peter MA, et al. Cognitive and Executive Function in Congenital Heart Disease: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2021 Oct;148(4):e2021050875. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-050875

6. Lee FT, Sun L, van Amerom JF, Portnoy S, Marini D, Saini A, et al. Fetal Hemodynamics, Early Survival, and Neurodevelopment in Patients With Cyanotic Congenital Heart Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024 Apr;83(13):1225–39. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2024.02.005

7. De Silvestro AA, Kellenberger CJ, Gosteli M, O’Gorman R, Knirsch W. Postnatal cerebral hemodynamics in infants with severe congenital heart disease: a scoping review. Pediatr Res. 2023 Sep;94(3):931–43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-023-02543-z

8. Nijman M, van der Meeren LE, Nikkels PG, Stegeman R, Breur JM, Jansen NJ, et al.; CHD LifeSpan Study Group ‡. Placental Pathology Contributes to Impaired Volumetric Brain Development in Neonates With Congenital Heart Disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024 Mar;13(5):e033189. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.123.033189

9. Homsy J, Zaidi S, Shen Y, Ware JS, Samocha KE, Karczewski KJ, et al. De novo mutations in congenital heart disease with neurodevelopmental and other congenital anomalies. Science. 2015 Dec;350(6265):1262–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac9396

10. De Silvestro AA, Krüger B, Steger C, Feldmann M, Payette K, Krüger J, et al. Cerebral desaturation during neonatal congenital heart surgery is associated with perioperative brain structure alterations but not with neurodevelopmental outcome at 1 year. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2022 Oct;62(5):ezac138. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezac138

11. O’Byrne ML, Baxelbaum K, Tam V, Griffis H, Pennington ML, Hagerty A, et al. Association of Postnatal Opioid Exposure and 2-Year Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Infants Undergoing Cardiac Surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024 Sep;84(11):1010–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2024.06.033

12. Lepage C, Bayard J, Gaudet I, Paquette N, Simard MN, Gallagher A. Parenting stress in infancy was associated with neurodevelopment in 24-month-old children with congenital heart disease. Acta Paediatr. 2025 Jan;114(1):164–72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.17421

13. Lepage C, Bayard J, Gaudet I, Paquette N, Simard MN, Gallagher A. Parenting stress in infancy was associated with neurodevelopment in 24-month-old children with congenital heart disease. Acta Paediatr. 2025 Jan;114(1):164–72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.17421

14. Cassidy AR, Rofeberg V, Bucholz EM, Bellinger DC, Wypij D, Newburger JW. Family Socioeconomic Status and Neurodevelopment Among Patients With Dextro-Transposition of the Great Arteries. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Nov;7(11):e2445863. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.45863

15. Sun L, Macgowan CK, Sled JG, Yoo SJ, Manlhiot C, Porayette P, et al. Reduced fetal cerebral oxygen consumption is associated with smaller brain size in fetuses with congenital heart disease. Circulation. 2015 Apr;131(15):1313–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013051

16. Ortinau CM, Mangin-Heimos K, Moen J, Alexopoulos D, Inder TE, Gholipour A, et al. Prenatal to postnatal trajectory of brain growth in complex congenital heart disease. Neuroimage Clin. 2018;20:913–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2018.09.029

17. Phillips K, Callaghan B, Rajagopalan V, Akram F, Newburger JW, Kasparian NA. Neuroimaging and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes Among Individuals With Complex Congenital Heart Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023 Dec;82(23):2225–45. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2023.09.824

18. Ottolenghi S, Milano G, Cas MD, Findley TO, Paroni R, Corno AF. Can Erythropoietin Reduce Hypoxemic Neurological Damages in Neonates With Congenital Heart Defects? Front Pharmacol. 2021 Nov;12:770590. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.770590

19. Natterer J, Schneider J, Sekarski N, Rathke V, Adams M, Latal B, et al. ORCHID (Outcome Registry for CHIldren with severe congenital heart Disease) a Swiss, nationwide, prospective, population-based, neurodevelopmental paediatric patient registry: framework, regulations and implementation. Swiss Med Wkly. 2022 Sep;152(3536):w30217. doi: https://doi.org/10.4414/SMW.2022.w30217

20. Feldmann M, Hagmann C, de Vries L, Disselhoff V, Pushparajah K, Logeswaran T, et al. Neuromonitoring, neuroimaging, and neurodevelopmental follow-up practices in neonatal congenital heart disease: a European survey. Pediatr Res. 2023 Jan;93(1):168–75. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-022-02063-2

21. Stegeman R, Feldmann M, Claessens NH, Jansen NJ, Breur JM, de Vries LS, et al.; European Association Brain in Congenital Heart Disease Consortium. A Uniform Description of Perioperative Brain MRI Findings in Infants with Severe Congenital Heart Disease: results of a European Collaboration. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2021 Nov;42(11):2034–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A7328

22. Kuklisova-Murgasova M, Quaghebeur G, Rutherford MA, Hajnal JV, Schnabel JA. Reconstruction of fetal brain MRI with intensity matching and complete outlier removal. Med Image Anal. 2012 Dec;16(8):1550–64. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2012.07.004

23. Meuwly E, Feldmann M, Knirsch W, von Rhein M, Payette K, Dave H, et al.; Research Group Heart and Brain*. Postoperative brain volumes are associated with one-year neurodevelopmental outcome in children with severe congenital heart disease. Sci Rep. 2019 Jul;9(1):10885. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47328-9

24. Bayley, N. 3rd ed. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development Manual; 2006.

25. Dubowitz L, Dubowitz V. The neurologic assessment of the preterm and full-term newborn infant. Clinics in Developmental Medicine. London, UK: Spastics International Medical Publications/William Heinemann Medical Books; 1981.

26. Haataja L, Mercuri E, Regev R, Cowan F, Rutherford M, Dubowitz V, et al. Optimality score for the neurologic examination of the infant at 12 and 18 months of age. J Pediatr. 1999 Aug;135(2 Pt 1):153–61. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3476(99)70016-8

27. Latal B. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of the Child with Congenital Heart Disease. Clin Perinatol. 2016 Mar;43(1):173–85. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2015.11.012

28. McQuillen PS, Miller SP. Congenital heart disease and brain development. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010 Jan;1184(1):68–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05116.x

29. Juergensen S, Liu J, Xu D, Zhao Y, Moon-Grady AJ, Glenn O, et al. Fetal circulatory physiology and brain development in complex congenital heart disease: A multi-modal imaging study. Prenat Diagn. 2024 Jun;44(6-7):856–64. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.6450

30. Sadhwani A, Wypij D, Rofeberg V, Gholipour A, Mittleman M, Rohde J, et al. Fetal Brain Volume Predicts Neurodevelopment in Congenital Heart Disease. Circulation. 2022 Apr;145(15):1108–19. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056305

31. Sien ME, Robinson AL, Hu HH, Nitkin CR, Hall AS, Files MG, et al. Feasibility of and experience using a portable MRI scanner in the neonatal intensive care unit. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2023 Jan;108(1):45–50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2022-324200

32. Neukomm A, Claessens NH, Bonthrone AF, Stegeman R, Feldmann M, Nijman M, et al.; European Association Brain in Congenital Heart Disease (EU-ABC) consortium. Perioperative Brain Injury in Relation to Early Neurodevelopment Among Children with Severe Congenital Heart Disease: results from a European Collaboration. J Pediatr. 2024 Mar;266:113838. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2023.113838

33. Bonthrone AF, Stegeman R, Feldmann M, Claessens NH, Nijman M, Jansen NJ, et al. Risk Factors for Perioperative Brain Lesions in Infants With Congenital Heart Disease: A European Collaboration. Stroke. 2022 Dec;53(12):3652–61. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.122.039492

34. Barzilay E, Bar-Yosef O, Dorembus S, Achiron R, Katorza E. Fetal Brain Anomalies Associated with Ventriculomegaly or Asymmetry: An MRI-Based Study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017 Feb;38(2):371–5. doi: https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A5009

35. Pappalardo EM, Militello M, Rapisarda G, Imbruglia L, Recupero S, Ermito S, et al. Fetal intracranial cysts: prenatal diagnosis and outcome. J Prenat Med. 2009 Apr;3(2):28–30.

36. Miller SP, McQuillen PS, Hamrick S, Xu D, Glidden DV, Charlton N, et al. Abnormal brain development in newborns with congenital heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2007 Nov;357(19):1928–38. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa067393

37. Dijkhuizen EI, de Munck S, de Jonge RC, Dulfer K, van Beynum IM, Hunfeld M, et al. Early brain magnetic resonance imaging findings and neurodevelopmental outcome in children with congenital heart disease: A systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2023 Dec;65(12):1557–72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.15588

38. Peyvandi S, Xu D, Barkovich AJ, Gano D, Chau V, Reddy VM, et al. Declining Incidence of Postoperative Neonatal Brain Injury in Congenital Heart Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023 Jan;81(3):253–66. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.10.029

39. Schellen C, Ernst S, Gruber GM, Mlczoch E, Weber M, Brugger PC, et al. Fetal MRI detects early alterations of brain development in Tetralogy of Fallot. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Sep;213(3):392.e1–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.046

40. Ortinau CM, Wypij D, Ilardi D, Rofeberg V, Miller TA, Donohue J, et al. Factors Associated With Attendance for Cardiac Neurodevelopmental Evaluation. Pediatrics. 2023 Sep;152(3):e2022060995. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-060995

41. Gaynor JW, Stopp C, Wypij D, Andropoulos DB, Atallah J, Atz AM, et al.; International Cardiac Collaborative on Neurodevelopment (ICCON) Investigators. Neurodevelopmental outcomes after cardiac surgery in infancy. Pediatrics. 2015 May;135(5):816–25. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-3825

42. Selvanathan T, Mabbott C, Au-Young SH, Seed M, Miller SP, Chau V; PCNR Study Group. Antenatal diagnosis, neonatal brain volumes, and neurodevelopment in transposition of the great arteries. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2024 Jul;66(7):882–91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.15840

43. Wilson S, Cromb D, Bonthrone AF, Uus A, Price A, Egloff A, et al. Structural Covariance Networks in the Fetal Brain Reveal Altered Neurodevelopment for Specific Subtypes of Congenital Heart Disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024 Nov;13(21):e035880. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.124.035880

44. Rowlands MA, Scheinost D, Lacadie C, Vohr B, Li F, Schneider KC, et al. Language at rest: A longitudinal study of intrinsic functional connectivity in preterm children. Neuroimage Clin. 2016 Jan;11:149–57. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2016.01.016

45. Young JM, Morgan BR, Whyte HE, Lee W, Smith ML, Raybaud C, et al.; Longitudinal Study of White Matter Development and Outcomes in Children Born Very Preterm. Longitudinal Study of White Matter Development and Outcomes in Children Born Very Preterm. Cereb Cortex. 2017 Aug;27(8):4094–105.

46. Variane GF, Chock VY, Netto A, Pietrobom RF, Van Meurs KP. Simultaneous Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) and Amplitude-Integrated Electroencephalography (aEEG): Dual Use of Brain Monitoring Techniques Improves Our Understanding of Physiology. Front Pediatr. 2020 Jan;7:560. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2019.00560

47. Chiperi LE, Tecar C, Toganel R. Neuromarkers which can predict neurodevelopmental impairment among children with congenital heart defects after cardiac surgery: A systematic literature review. Dev Neurorehabil. 2023 Apr;26(3):206–15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17518423.2023.2166618

The appendix is available in the pdf version of the article at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4466.