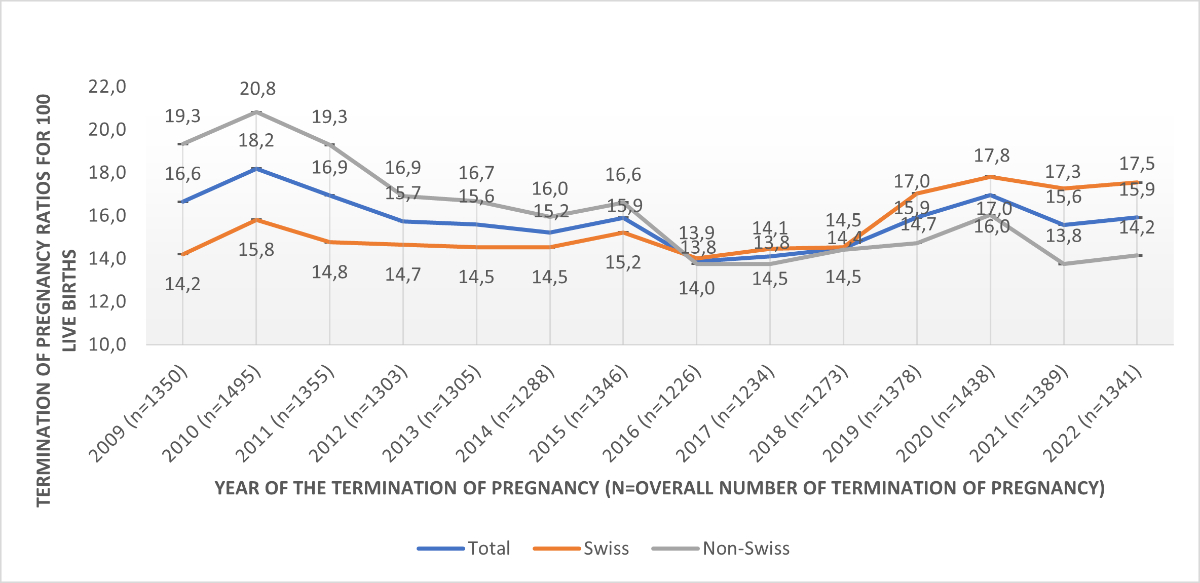

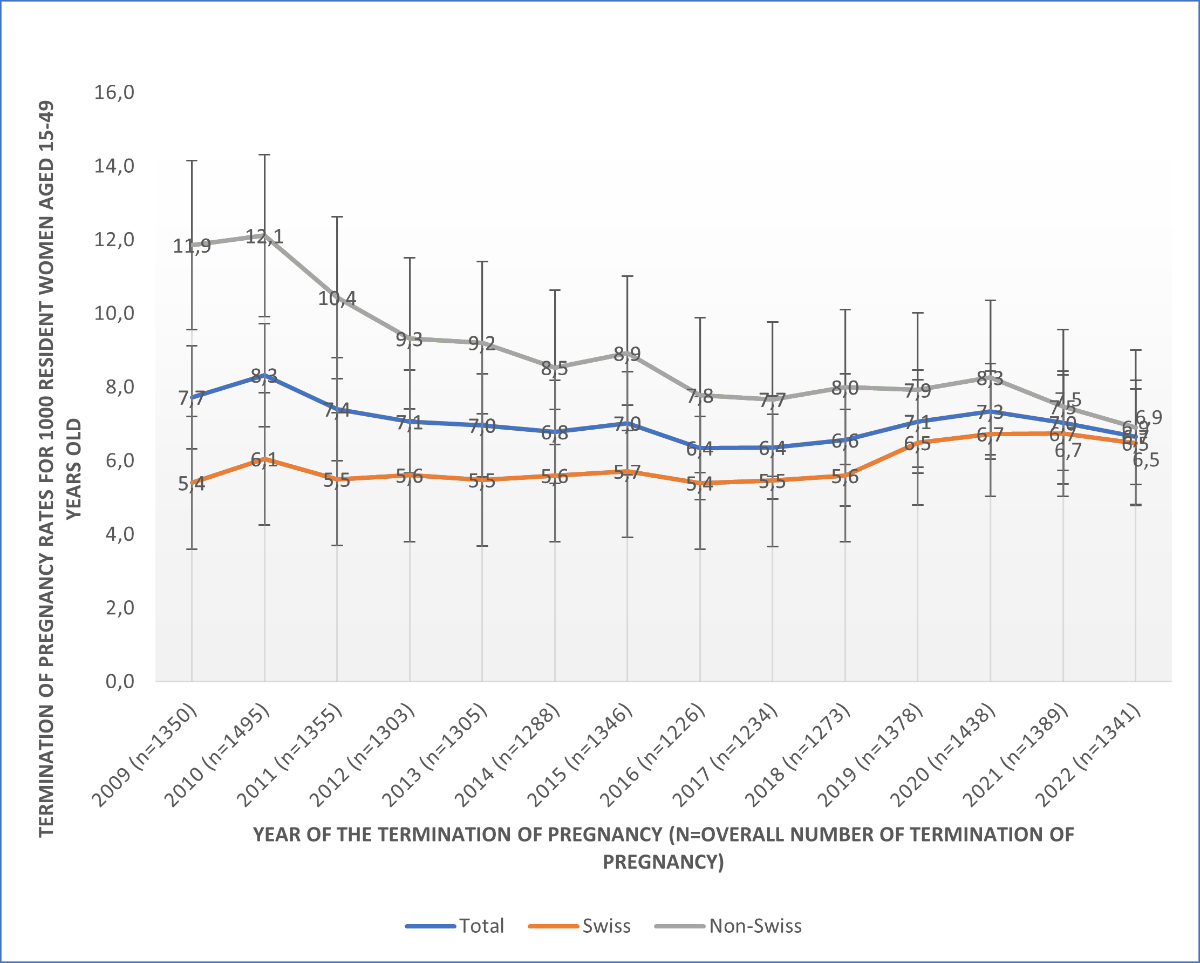

Figure 1Termination of pregnancy rates for 1000 resident women aged 15–49 years in the period 2009–2022, comparing non-Swiss and Swiss women. 95% confidence intervals are shown.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/4461

Termination of pregnancy is a frequent medical procedure and is an essential component of public health [1]. As pointed out by Moseson et al. [2], it occurs in all settings, regardless of its legal status. Data [3] indicate that unintended pregnancy rates (a pregnancy that occurred sooner than desired or not wanted at all) are on the decline around the world, largely due to increased access and use of contraception. Indeed, between 2015 and 2019, the worldwide annual rate of unintended pregnancies was on average 64 per 1000 women aged 15–49, while between 1990 and 1994, the rate was 79 per 1000 [3]. Although the overall rate of unintended pregnancies has declined, a growing proportion of these unintended pregnancies now end in termination of pregnancy [3]. Regarding termination of pregnancy, the rate declined in Europe and North America, but increased in other regions, including Sub-Saharan Africa, and Central and South Asia [3]. The worldwide annual termination of pregnancy rate between 2015 and 2019 was 39 per 1000 women aged 15–49, a rate very similar to the one reported between 1990 and 1994 (40 per 1000). Better access to reproductive services and societal changes driven by women’s empowerment may explain these trends.

The lowest rates of termination of pregnancy are found in high-income countries where termination of pregnancy is legal, with an annual rate of 11 per 1000 women aged 15–49. In contrast, the rate is 32 per 1000 in high-income countries with restrictive laws and 48 per 1000 in middle- and low-income countries. Between 2010 and 2014, more than three quarters of terminations of pregnancy were reported in low- and middle-income countries across all sociodemographic subgroups [4]. Globally, between 2010 and 2014, 20–24 year-old women tended to be those with the highest termination of pregnancy rates [5]. For example, in the United States in 2019, women aged 20–24 and 25–29 represented the majority of terminations of pregnancy (27.6% and 29.3%, respectively) and had the highest termination of pregnancy rates (19.0 and 18.6 per 1000, respectively) [6]. It is important to add that the United States has a high rate of teenage births per 1000 women aged 15–19 compared to other high-income countries [7]. In France, in 2020, the highest termination of pregnancy rate was also observed among 20–29 year-old women [8]. In a global ranking based on estimated rates for the period 2015–2019, Switzerland had the lowest termination of pregnancy rate, equivalent to that of Singapore, right below Japan, Germany and Portugal [9]. Switzerland is divided into 26 cantons (states) and in the national ranking, the canton of Vaud – the scope of the present study – had the third-highest termination of pregnancy rate in Switzerland in 2022, with a rate of 9.7‰ compared to the national average rate of 7.0‰ [10]. However, it is important to note that for the calculation of these rates, all terminations of pregnancy performed in the canton were included in calculations, regardless of the woman’s age and whether she lived in the canton.

In Switzerland, termination of pregnancy is allowed up to 12 weeks of amenorrhoea [11]. A termination of pregnancy after 12 weeks is permitted only if a gynaecologist determines that it is necessary to prevent physical or psychological harm to the pregnant woman. Termination also requires the pregnant woman’s free and informed consent, provided in writing and in person. Two methods are available for terminating a pregnancy: drug-based or surgical [12]. If a drug-based method is used, termination of pregnancy at home has been allowed under certain conditions since 2021 [13].

As pointed out by the Guttmacher Institute in 2018 [5], certain regions, such as some former Soviet Bloc countries or the United States, have implemented restrictions to accessing termination of pregnancy services. For instance, in 2022, termination of pregnancy was banned in 14 states across the United States following a Supreme Court decision [14]. In Switzerland, the right to termination of pregnancy has also faced challenges from popular initiatives seeking to restrict it. However, these were withdrawn in 2023 owing to lack of signatures [15, 16].

There is a lack of data on termination of pregnancy worldwide. As noted by Popinchalk et al. [17], some European countries have incomplete statistics. Furthermore, in a context where access to termination of pregnancy seems to be threatened, it is important to examine the situation in Switzerland and provide an overview of the available termination of pregnancy data. The aim of this article is to present the characteristics of women who had a termination of pregnancy in the canton of Vaud in 2022 and to analyse termination of pregnancy trends over the last decade. In this article, we use the words “woman” or “women” but these data concern anyone who had a termination of pregnancy regardless of gender.

We conducted a cross-sectional study to analyse trends regarding rates, ratios and sociodemographic characteristics of women who underwent a termination of pregnancy in the canton of Vaud over the last decade. In addition to trends, we present data for 2022 (the latest data available at the time of writing) to give an overview of the current situation.

According to the penal code [11], gynaecologists have to declare every termination of pregnancy, including data on the intervention and the woman, to the local Health Authority for statistical and monitoring purposes. This monitoring has evolved over time. Since 2021, the information has been collected through an online form completed by the gynaecologist, whereas previously it was recorded on a paper form that had to be returned by post.

We used data for the period 2009–2022 from the canton of Vaud, the area for which our team is responsible for analysing the data (collected and managed by the Federal Statistical Office).

Data are collected throughout the year and include all women who underwent a termination of pregnancy in the canton of Vaud. However, our analyses focused exclusively on women residents of the canton of Vaud aged 15–49, as the rate and ratio calculations are based on official statistics, which only include permanent and non-permanent residents of the canton.

Population data, used as denominators for some results, were obtained from Federal Statistical Office publications [18].

Sociodemographic characteristics include citizenship, place of residence, marital status, type of household, highest level of education achieved, number of living children and main activity at the time of the termination of pregnancy.

Information regarding the reproductive life of women includes number of previous terminations of pregnancy and last delivery date, if any. Since 2021, women who underwent a termination of pregnancy have also been asked about the contraceptive method used at the time of conception and several answers are possible. We grouped them according to the World Health Organization’s ranking [19] of effectiveness of contraceptive methods. The different categories, from most to least effective, were as follows:

Regarding the answers, when one or more methods were indicated in the form, the others were considered as not being used. When no method at all was reported, the method of contraception was considered as Unknown.

Gestational age was used for measuring the length of pregnancy.

Some data items were compulsory. When they were missing, the person in charge of our team called the gynaecologist to collect the information. For other, optional questions (education, main activity, marital status, household type, number of living children, contraceptive methods), there was an Unknown option on the form. We grouped the Unknown responses with missing data items.

The regional Statistical Office transmits population data (women residents and live births) of the canton of Vaud by age group and by nationality for each year. These indicators make it possible to adjust the number of terminations of pregnancy for differences in population size [6, 20]. The number of births among the permanent and non-permanent resident population according to the mother’s age (between 15 and 49 years old) and citizenship (Swiss versus non-Swiss) was used to calculate the termination of pregnancy ratio per 100 live births. This ratio helps us understand how many pregnancies culminate in termination of pregnancy compared to live births [6].

We used STATA 18.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) for all the analyses.

This work is part of an ongoing state-led epidemiological surveillance programme for public health monitoring. It was not conducted as a research study with a separate study protocol. Therefore, no protocol was registered in a public registry.

No analytical code or datasets are available for open sharing. The work is part of state-led epidemiological surveillance. Analyses were conducted using STATA version 18.0 without the development of reusable custom code.

For each section, we present data for 2022 and trends since 2009. The main trends are described in more detail.

In 2022, 1603 terminations of pregnancy took place in the canton of Vaud among women aged 15–49. Most of them concerned women living in the canton of Vaud (87.3% / n = 1399). Our analyses will only focus on women resident in the canton of Vaud and, as mentioned above, aged 15–49. Furthermore, to be able to compare Swiss and non-Swiss women, terminations of pregnancy by women whose nationality was unknown (n = 58) were removed from these analyses. Therefore, the following results are based on a sample of 1341 women.

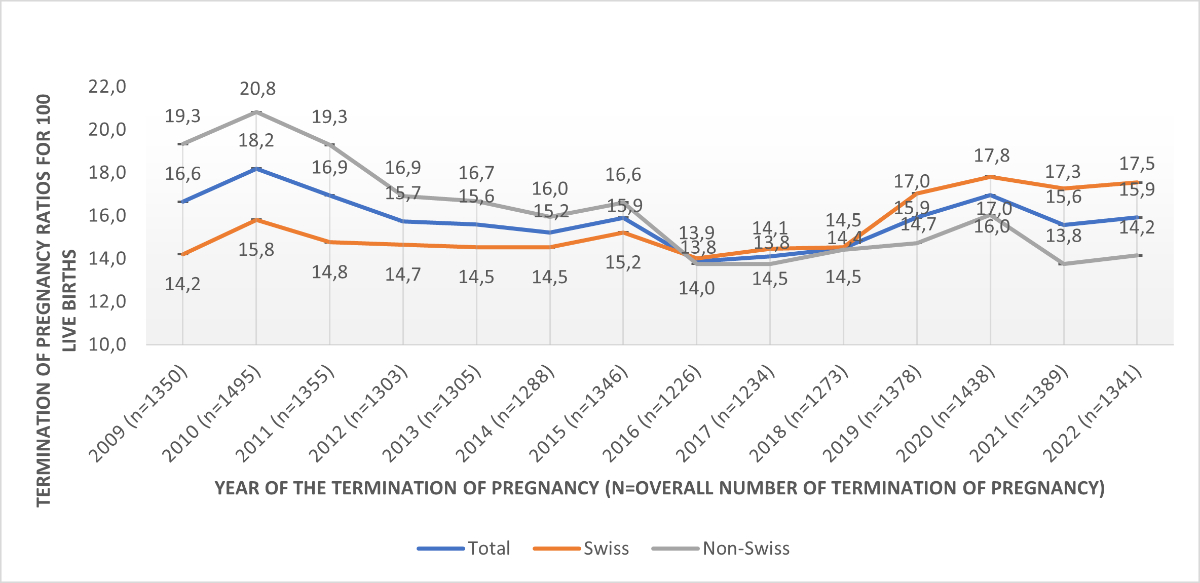

The rate of terminations of pregnancy for resident women was 6.7‰ (n = 1341), and, respectively, 6.5‰ among Swiss women and 6.9‰ among non-Swiss women. More than half of women who underwent a termination of pregnancy were Swiss (57.3%). There were 16.6 terminations of pregnancy for 100 live births, with 17.5 among Swiss women and 14.2 among non-Swiss women. The mean age of women who underwent a termination of pregnancy was 29.6 years (range: 15–47), 29.3 years for Swiss women and 30.1 years for non-Swiss women. The median age was 30 years, 29 years for Swiss women and 30 years for non-Swiss women. Among all women aged 15–49, 1.9% (n = 27) were aged 15–17 (table 1).

Between 2009 and 2022, the gap between Swiss women and those with a foreign origin narrowed (5.4 among Swiss women and 11.9 among non-Swiss women in 2009; 6.5 among Swiss women and 6.9 among non-Swiss women in 2022).

Table 1.Sociodemographic characteristics (n = 1341).

| Nationality | Swiss | 57.3% |

| Non-Swiss | 42.7% | |

| Age range | 15–47 | |

| Age (mean ± standard error) | 29.6 ± 0.18 | |

| Median age | 30.0 | |

| Education | None | 2.6% |

| Compulsory | 17.4% | |

| High school/vocational | 48.5% | |

| Tertiary | 24.4% | |

| Missing/unknown | 7.1% | |

| Main activity | Employed | 60.5% |

| In training | 14.9% | |

| Housewife | 7.8% | |

| Looking for work | 7.2% | |

| Other | 5.2% | |

| Missing/unknown | 4.4% | |

| Marital status | Single | 65.3% |

| Married / registered partnership | 23.7% | |

| Divorced | 6.3% | |

| Other | 1.5% | |

| Missing/unknown | 3.2% | |

| Household type | With a partner and child(ren) | 30.1% |

| With a partner, but no children | 13.3% | |

| Single, with child (ren) | 12.5% | |

| Single, without children | 18.1% | |

| With parents | 15.6% | |

| Other | 6.8% | |

| Missing/unknown | 3.6% | |

| Number of living children | 0 | 52.5% |

| 1 | 18.4% | |

| 2 | 20.4% | |

| 3 | 5.8% | |

| ≥4 | 1.8% | |

| Missing/unknown | 1.1% | |

Figure 1Termination of pregnancy rates for 1000 resident women aged 15–49 years in the period 2009–2022, comparing non-Swiss and Swiss women. 95% confidence intervals are shown.

Figure 2Termination of pregnancy ratios for 100 live births, 2009–2022, comparing non-Swiss and Swiss women. 95% confidence intervals are shown.

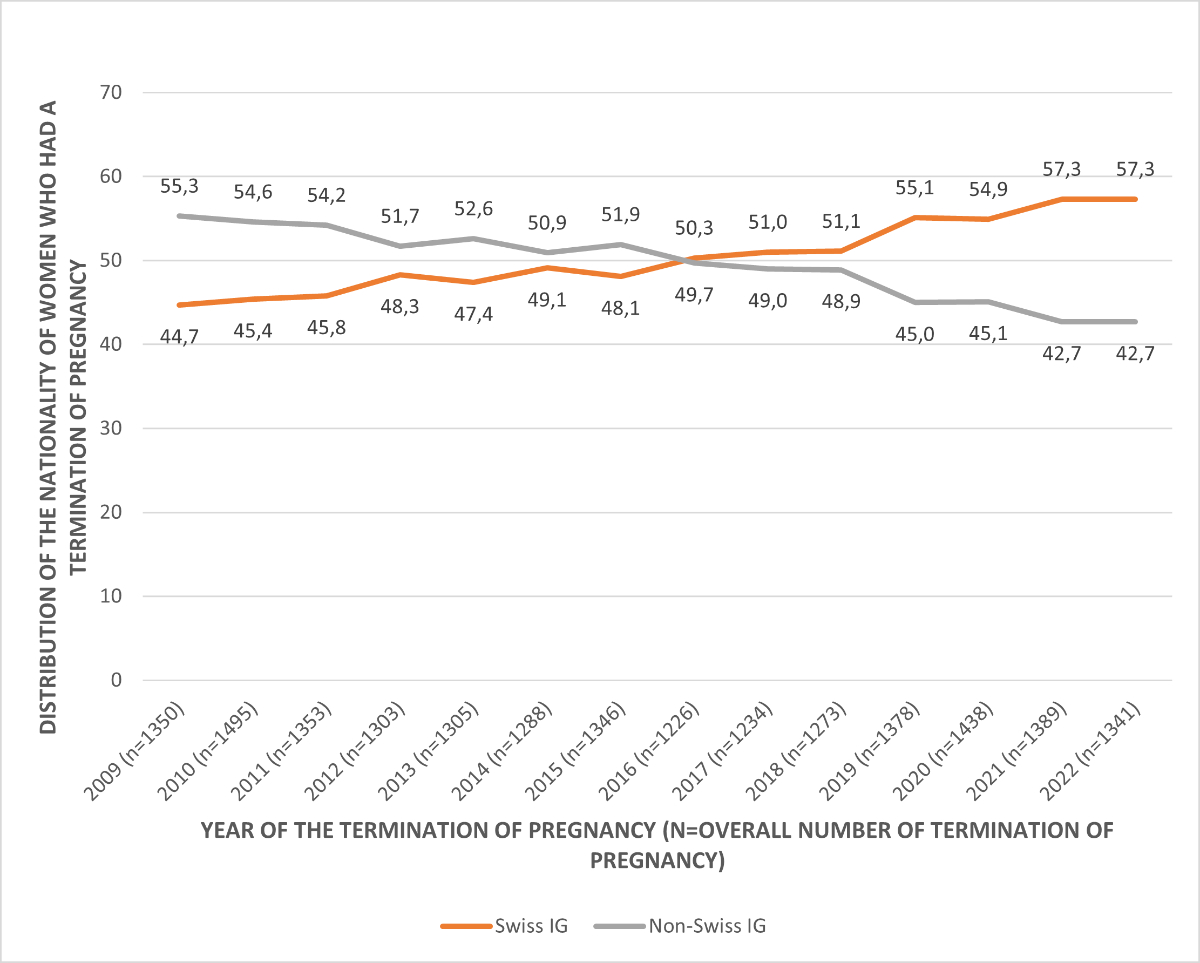

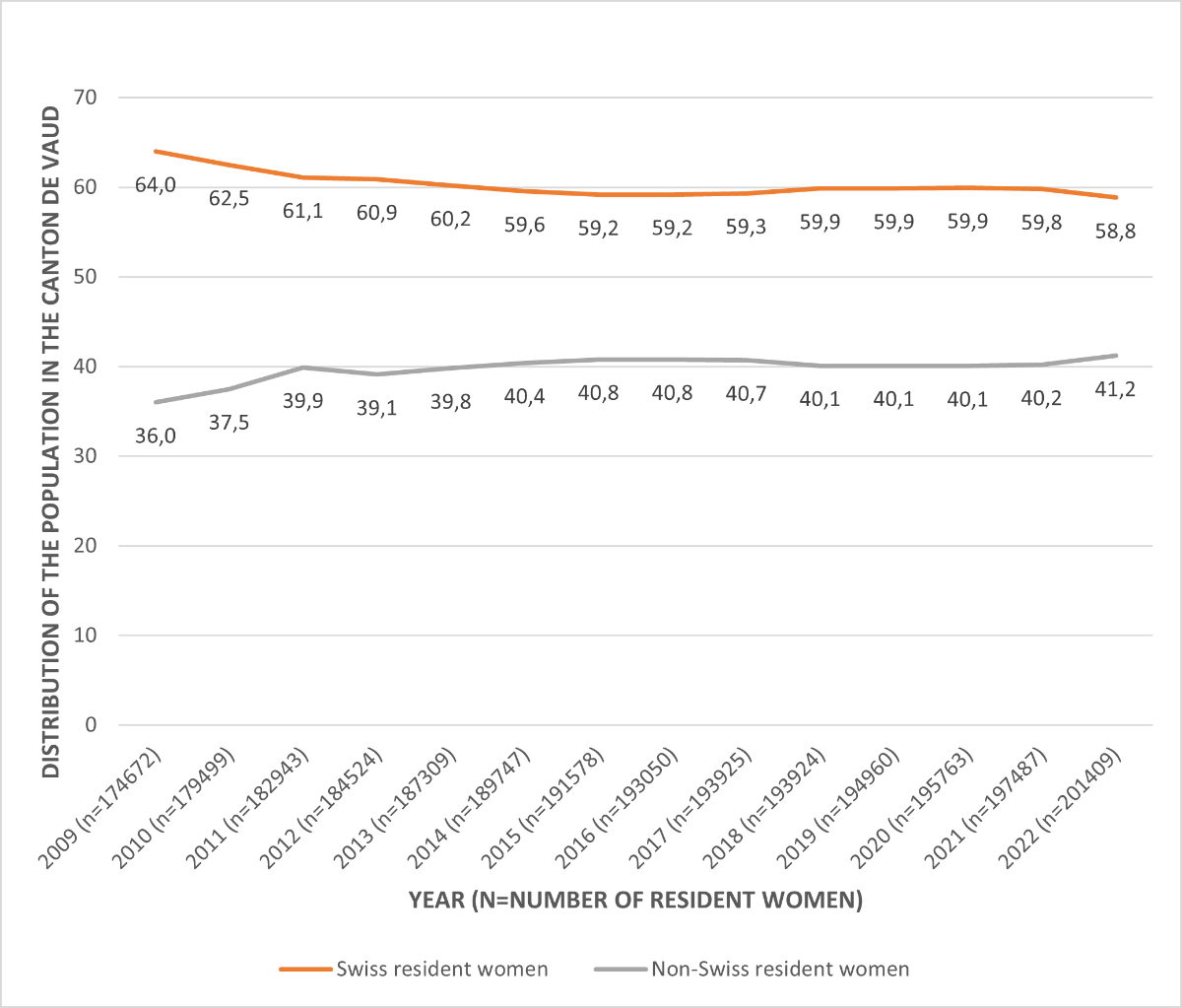

By controlling for the distribution of the population according to the ratio of Swiss and non-Swiss women, the inversion observed in termination of pregnancy rates does not follow an inversion that would have occurred in the population in terms of the distribution between Swiss and non-Swiss women. Indeed, while the distribution between Swiss and non-Swiss resident women remained stable between 2009 and 2022 (around 60% Swiss and 40% foreign) (figure 3), the distribution between Swiss and non-Swiss women in terms of termination of pregnancy underwent a shift in 2016 (figure 4).

Figure 3Distribution of the population in the canton of Vaud.

Figure 4Distribution of the nationality of women who had a termination of pregnancy.

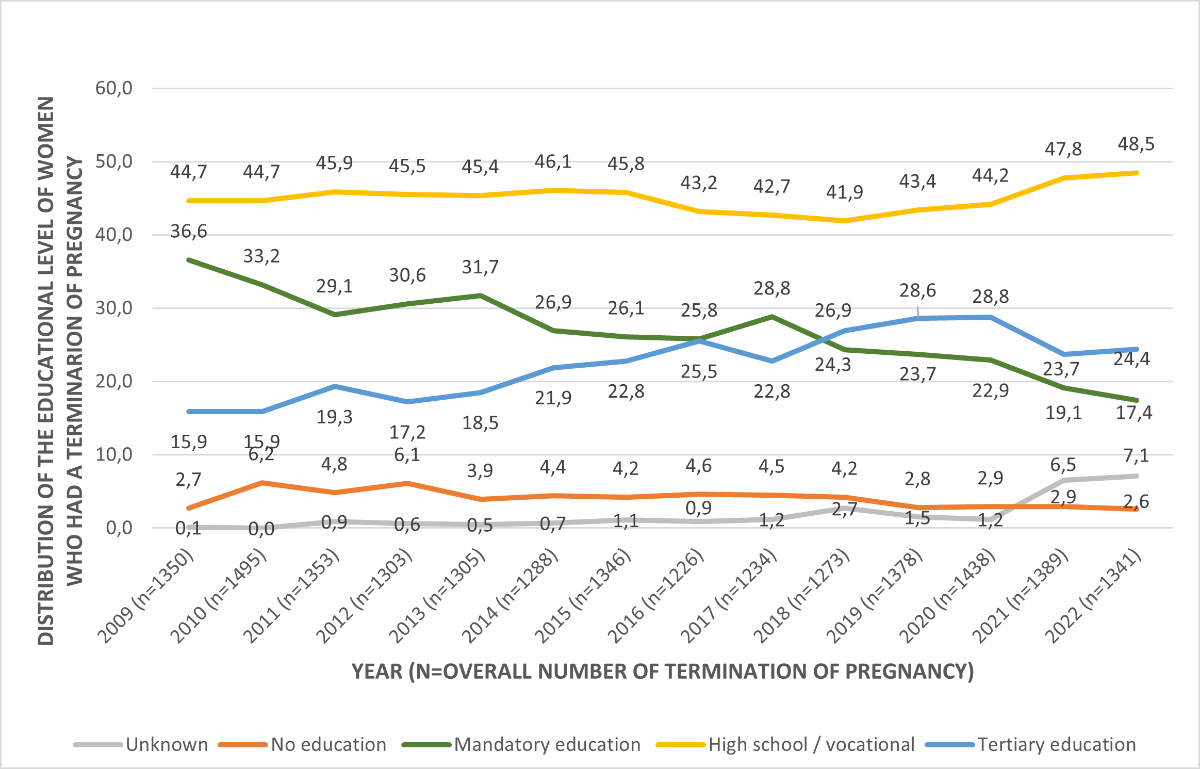

In 2022, among women who underwent a termination of pregnancy, almost half (48.5%) had a degree from a high school/vocational education, a quarter (24.4%) had a tertiary education and one seventh (17.4%) had completed compulsory education (table 1). Between 2009 and 2022, the relative proportion fell for women who completed compulsory education (36.6% to 17.4%) and rose for women who completed tertiary education (15.9% to 24.4%). The proportion of women with no education who went through a termination of pregnancy has remained stable since 2009 (2.7% in 2009 and 2.6% in 2022) (figure 5).

Figure 5Termination of pregnancy rates according to level of education at the time of termination of pregnancy.

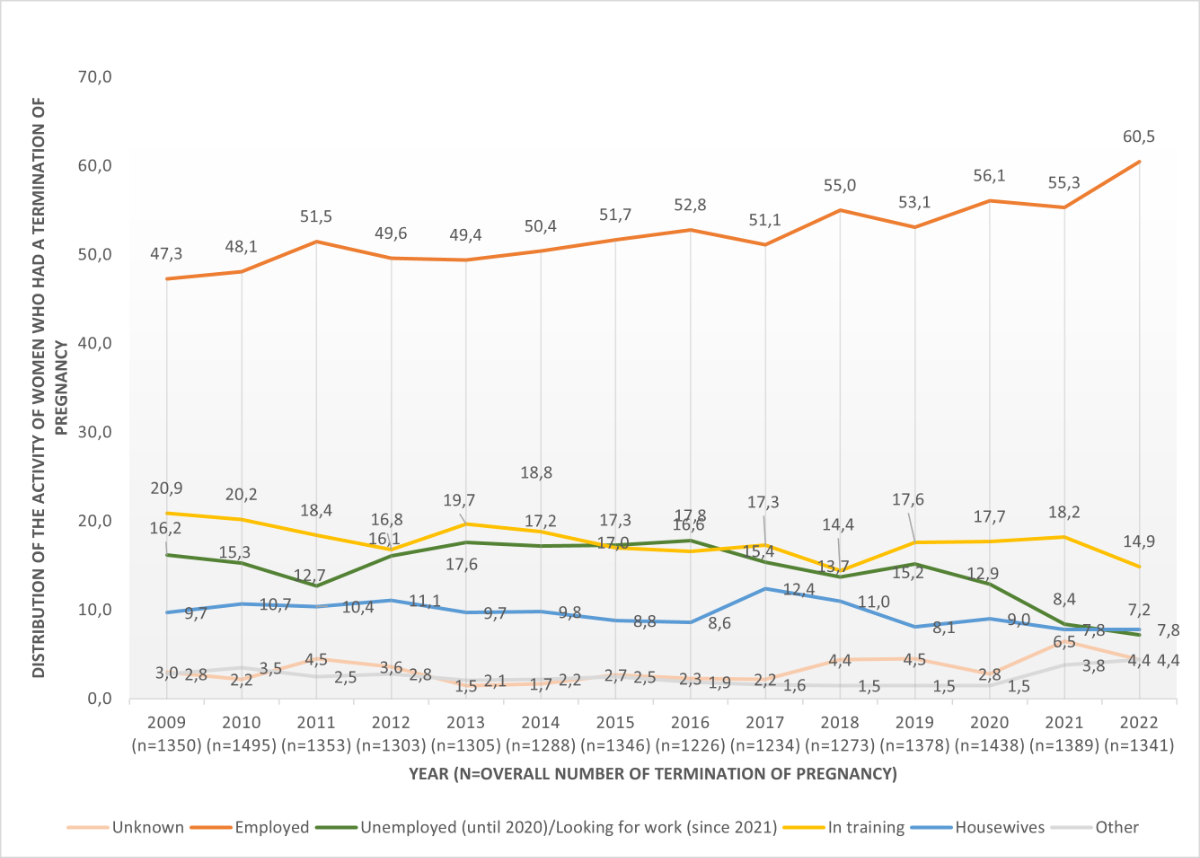

In 2022, almost two thirds were employed (60.3%) and a seventh were in training (14.8%) at the time of the intervention (table 1).

In 2021, the category “Unemployed” was replaced by “Looking for work”. We grouped them into the same category in the figure. Between 2009 and 2022, there were decreases in the proportions of women who were housewives at the time of the intervention (9.8% in 2009 vs 7.6% in 2022), unemployed (the category used until 2020) or looking for work (the category used since 2021) – potentially due to the category change (16.2% in 2009 vs 7.3% in 2022) – or in training (20.9% in 2009 vs 14.8% in 2022); over the same period, the proportion of women in employment increased (from 47.3% in 2009 to 60.5% in 2022) (figure 6).

Figure 6Termination of pregnancy rates by activity at the time of termination of pregnancy.

In 2022, according to the entry at the registry office, two thirds were single (65.3%) and a quarter were married (23.6%). More than a third lived with a partner and child(ren) (29.9%), one fifth lived alone without children (18.5%) and a seventh lived with parent(s) (15.6%). Less than half had living child(ren) (46.4%) (table 1).

Between 2009 and 2022, the proportion of single women increased (from 59.5% in 2009 to 65.3% in 2022) while that of married women decreased (from 27.0% in 2009 to23.6% in 2022), reflecting a general trend in the canton of Vaud, where the rate of marriages per 1000 inhabitants has decreased since 2009 (5.3 in 2009 vs 4.2 in 2022) [21].

The proportion of women who had child(ren) remained stable (47.0% in 2009 and 46.4% in 2022).

The mean gestational age at termination of pregnancy was 8.0 weeks of amenorrhoea (range: 3–29 weeks) and the median was 7.0 weeks. (The wording on the form was slightly ambiguous. It states “Gestational age to be indicated in weeks of pregnancy [WP] at the time of interruption [calculated from the 1st day of the last menstrual period, e.g. 9 = 10th week of pregnancy]”, which is the definition for weeks of amenorrhoea. Nevertheless, as it is customary among professionals to always communicate in weeks of amenorrhoea, it is unlikely that the value provided is in weeks of pregnancy.)

The mean reason for termination of pregnancy was psychosocial (92.7%).

Regarding contraceptive method (multiple answers possible), about 28.1% used external condoms or natural methods (temperature, calendar, etc) at the time of conception. In nearly a quarter of cases (22.1%), no contraception was used. Approximately one seventh (13.9%) used the pill, patch, injection or ring. Less than 5% (4.3%) relied on internal condoms, withdrawal (coitus interruptus) or spermicide. Finally, sterilisation, IUDs or implants were reported in 2.5% of cases. Other methods (emergency contraception, diaphragm/cervical cap) were reported in 1.7% of cases. For 31.2% of women, the method was unknown.

Almost two thirds did not report a previous termination of pregnancy (65.1%). Among women who had already given birth (n = 545), in more than a tenth (12.1%), the termination of pregnancy in 2022 took place within 12 months of a previous childbirth (table 2).

Table 2.Reproductive life (n = 1341).

| Mean gestational age (weeks of amenorrhoea)a | 8.0 | |

| Median gestational age (weeks of amenorrhoea) | 7 | |

| Reason for termination of pregnancy | Psychosocial | 92.7% |

| Other (somatic, financial, rape, etc) | 7.3% | |

| Contraceptive methodb (multiple answers possible)c | Sterilisation, intrauterine device (IUD), implant | 2.5% |

| Pill, ring, patch, injection | 13.9% | |

| Externald condom, natural method (temperature, calendar, etc) | 28.1% | |

| Internal condom, withdrawal (coitus interruptus), spermicide | 4.3% | |

| Other method (emergency contraception, diaphragm/cervical cape) | 1.7% | |

| None | 22.1% | |

| Missing/unknown | 31.2% | |

| Number of previous terminations of pregnancy | 0 | 65.1% |

| 1 | 21.5% | |

| 2 | 6.6% | |

| 3 or more | 3.1% | |

| Missing/unknown | 3.7% | |

| Termination of pregnancy less than a year after childbirth (n = 545) | 12.1% | |

a Ambiguous wording used on form, as follows: “Gestational age to be indicated in weeks of pregnancy (WP) at the time of interruption (calculated from the 1st day of the last menstrual period, e.g. 9 3/7 = 10th week of pregnancy”.

b Categorisation according to practical/real-world effectiveness rather than theoretical effectiveness. Source: World Health Organization and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health / Center for Communication Programs. Family planning: a global handbook for providers, 4th ed. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9780999203705

c When at least one method of contraception was selected, non-selected methods were considered as not being used. When no methods were reported, the method was considered to be unknown.

d The form says “Condom” but we assume it refers to the external condom given that the following response option is “Female condom”.

e Please note that the form places the diaphragm and the cervical cap in the same category even though they do not have the same effectiveness according to the source document used.

In 2022, the termination of pregnancy rate in the canton of Vaud was 6.7 per 1000 resident women aged 15–49. This rate is above the national average, which was 5.8‰ [22]. At the international level, Switzerland is one of the countries with the lowest termination of pregnancy rate in the world, indicating good information, access to termination of pregnancy and use of contraception. The rate is between those of Portugal (6.5‰) and Spain (8.4‰) [23]. However, these comparisons should be treated with caution, as the rates for several countries are still missing or incomplete and are not identical from one source to another. For example, our calculations indicate 6.9 terminations of pregnancy per 1000 resident women in Switzerland in 2020 [24], while Eurostat indicates 5.1‰, without mention of the source used [23]. This demonstrates the importance of strictly monitoring and sourcing data on termination of pregnancy.

Among women who had a termination of pregnancy in 2022, less than half had previously given birth. Of the latter group, more than a tenth had delivered in the year before the termination of pregnancy. In the canton of Vaud, sexual health specialists visit women who have given birth in hospital in the days following childbirth [25]. They discuss with the patient which methods of contraception to use in the future and explain the conditions for using lactational amenorrhoea as a method. One of the aims of the intervention is to prevent unwanted pregnancy in the months following childbirth. Indeed, as pointed out by Liljeblad et al. [26], the need for effective contraception after childbirth is often underestimated. Our findings highlight the importance of continuing to prevent unwanted pregnancies after childbirth. Adequate information must be given to a woman and her partner after childbirth, to help them find a contraceptive method that is desirable for her.

Regarding trends, since 2009, there has been a decrease in the rates of terminations of pregnancy among non-Swiss women, while it has increased among Swiss women. These rates converged in 2022 (6.9‰ among non-Swiss women and 6.5‰ among Swiss women). The rising rate of terminations of pregnancy among Swiss women reflects a trend also observed at the national level, which has increased since 2017 [22]. However, the rates at the national and local levels remain among the lowest in the world. Regarding the decreasing rate of terminations of pregnancy among non-Swiss women, although this hypothesis cannot be verified, it could be that, between 2009 and 2022, the proportion of undeclared foreigners in Switzerland decreased, thereby increasing the total number of foreign people declared and therefore the denominator, leading to a decrease in the rate [27]. Regarding the numerator, that is the number of foreign women who had a termination of pregnancy, according to our data, although the proportion of those without a permit among people who had a termination of pregnancy has decreased since 2013, the rate of women whose residence permit is unknown has unfortunately increased (data not shown), which does not allow us to analyse the proportions in terms of permit type. However, one of the main reasons for this decrease in the terminations of pregnancy rate among non-Swiss could also be better access to information, first, and then to contraceptive methods.

Moreover, a shift has occurred among Swiss and non-Swiss women: in 2016, there were more terminations of pregnancy per 100 live births among Swiss women than non-Swiss women, whereas the opposite was true before 2016. This result may be explained by the fact that among Swiss women, the number of live births remained relatively stable between 2009 and 2022, while the number of terminations of pregnancy increased significantly between 2016 and 2022, leading to an increase in the ratio of terminations of pregnancy per 100 live births. However, among non-Swiss women, the number of births increased between 2009 and 2016, before decreasing, and the number of terminations of pregnancy decreased between 2009 and 2022, which explains why the ratio of terminations of pregnancy per 100 live births decreased from 2009 until 2016, before rising slightly.

The proportion of women with tertiary education among those who had a termination of pregnancy increased between 2009 and 2022. This result reflects a trend in the general population of the canton [28], but also in Switzerland, where the proportion of women with tertiary education also increased in the general population [29]. The growing rate of women in employment among those who had a termination of pregnancy also reflects a trend in the general population. Indeed, over the last 20 years, women living in the canton have significantly increased their participation in the labour market [28]. Finally, the low percentage of women under 18 reflects the importance of comprehensive sexuality education actions that contribute to preventing and reducing unintended pregnancies [30].

Thanks to the compulsory monitoring of terminations of pregnancy in Switzerland, this study provides detailed information on the characteristics of women who have undergone a termination of pregnancy and how this profile has evolved over the years. However, some limitations need to be put forward. First, given that this is an epidemiological monitoring programme that is not governed by our team, we do not choose what is or is not measured. Second, data filling depends on the physician conducting the intervention and his or her understanding of the questions. Some may fill in the questions in a more detailed/systematic manner, while others may not answer all the questions accurately. The way the form is completed, which may vary from one practitioner to another, but also changes in the form, and other factors, may influence the trends, which should therefore be interpreted with caution [27]. It is important to make practitioners aware of the importance of filling in forms as accurately and precisely as possible, to ensure epidemiological follow-up with reliable data but also to have accurate forms with unambiguous answers. Third, due to the structure of the questionnaire (with optional questions), some data are missing. Fourth, since the patient does not complete the questionnaire herself, the risk of a response bias exists. Fifth, since monitoring is not carried out in the same way in every country, data may not necessarily be comparable between regions, including between the different linguistic regions in Switzerland. Finally, one of the limitations of current monitoring systems in Switzerland is the lack of harmonised denominators for rate calculations. Some use the total women population, others only women aged 15–49, making comparisons between cantons and systems difficult. While use of FSO population data allows standardisation, it is not always implemented. Standardised definitions and comparable figures are essential for improving epidemiological surveillance.

This study showed that, overall, the rate of terminations of pregnancy remains stable, with a slight decrease since 2010 and while it decreased among non-Swiss women, it increased among Swiss women. To ensure that the rate of terminations of pregnancy continues to decrease, it is necessary to continue to provide information and services to all populations, regardless of their age, nationality, level of education and main activity. Furthermore, these services must be economically and geographically accessible to everyone. New measures are being introduced to this end. For instance, since January 2024, the Sexual Health Consultation of the PROFA Foundation in the canton of Vaud, the Family Planning Centre, is authorised to perform drug-based termination of pregnancy, thanks to a permit granted by the Cantonal Medical Office and a revision of the directive governing this practice [31]. Such a measure improves access to termination of pregnancy, notably by preventing individuals who initially visit one centre from having to go to another centre to obtain the procedure. Finally, it is also important to provide appropriate information and services according to individual needs and wishes, so that people can choose a contraceptive method that is right for them. For young people, sex education actions are necessary to open discussion and remove taboos on these issues.

Then, measures taken to prevent unwanted pregnancies after childbirth must be maintained, through information and contraceptive methods that are appropriate for individuals.

Furthermore, measures must be taken to ensure that monitoring is accurate and consistent among professionals who complete the pregnancy termination form and among cantons. It is important to have precise forms but also that all people involved in filling in the forms coordinate themselves at least at cantonal level. Cantons should also follow national guidelines so that data can be compared between regions.

The results showed also that termination of pregnancy concerns people of all ages, professions and educational backgrounds. It is important not to stigmatise those who have a termination of pregnancy, and not to consider that it only concerns a certain segment of the population.

Finally, in Switzerland, movements against abortion continue to grow, including political ones. It should be noted that termination of pregnancy is currently regulated by the Swiss Penal Code. This means that it is considered a criminal offence, with some exceptions [32]. In 2022, a parliamentary initiative aiming to remove termination of pregnancy from the Penal Code and treat it as a health issue rather than a criminal matter was rejected by the National Council [33]. Following this initiative, it is important that political measures promote access to termination of pregnancy, respect the free choice of those concerned and combat the stigmatisation of people who have a termination of pregnancy. The medical profession must also continue to receive training to provide the best possible support to those wishing or needing to terminate a pregnancy.

The data underlying this study were collected under a contractual mandate and contain sensitive information. Participants did not provide consent for public or third-party data sharing. For these ethical and legal reasons, the data are not publicly available and cannot be shared.

This research was funded by the General Directorate for Health (Direction Générale de la Santé) of the canton of Vaud.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript was disclosed.

1. Roberts SC, Fuentes L, Berglas NF, Dennis AJ. A 21st-Century Public Health Approach to Abortion. Am J Public Health. 2017 Dec;107(12):1878–82.

2. Moseson H, Herold S, Filippa S, Barr-Walker J, Baum SE, Gerdts C. Self-managed abortion: A systematic scoping review. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2020 Feb;63:87–110.

3. Bearak J, Popinchalk A, Ganatra B, Moller AB, Tunçalp Ö, Beavin C, et al. Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990-2019. Lancet Glob Health. 2020 Sep;8(9):e1152–61.

4. Chae S, Desai S, Crowell M, Sedgh G, Singh S. Characteristics of women obtaining induced abortions in selected low- and middle-income countries. PLoS One. 2017 Mar;12(3):e0172976.

5. Guttmacher Institute. Abortion Worldwide 2017: Uneven Progress and Unequal Access. 2018 [cited 2023; Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/abortion-worldwide-2017

6. Kortsmit, K., et al., Abortion Surveillance - United States. MMWR. Serveillance Summaries. 2018;2020:69–7.

7. Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, Marmot M, Resnick M, Fatusi A, et al. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2012 Apr;379(9826):1641–52.

8. République Française. 232 200 interruptions volontaires de grossesse en 2019, un taux de recours qui atteint son plus haut niveau depuis 30 ans. 2020 24 septembre 2020]; Available from: https://drees.solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/communique-de-presse/232-200-interruptions-volontaires-de-grossesse-en-2019-un-taux-de-recours-qui

9. Bearak JM, Popinchalk A, Beavin C, Ganatra B, Moller AB, Tunçalp Ö, et al. Country-specific estimates of unintended pregnancy and abortion incidence: a global comparative analysis of levels in 2015-2019. BMJ Glob Health. 2022 Mar;7(3):e007151.

10. Office fédéral de la statistique. Nombre et taux d'interruptions de grossesse, selon le canton d'intervention. 2022 [cited 2024 11 January]; Available from: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/sante/etat-sante/reproductive/interruptions-grossesses.assetdetail.26386370.html

11. L’Assemblée fédérale de la Confédération suisse, Code pénal suisse du 21 décembre 1937, Article 119, in Confédération suisse. Berne 2020.

12. Etat de Vaud. Interruption de grossesse. [cited 2024 11 January]; Available from: https://www.vd.ch/themes/sante-soins-et-handicap/pour-les-professionnels/interruption-de-grossesse

13. Département de la santé et de l'action sociale, Directive du 8 juillet 2021 relative à l'interruption de grossesse selon les articles 118, 119 et 120 du Code pénal. 2021.

14. United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. United States: Abortion bans put millions of women and girls at risk, UN experts say. 2023; Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2023/06/united-states-abortion-bans-put-millions-women-and-girls-risk-un-experts-say

15. Confédération Suisse, Initiative populaire fédérale 'Pour la protection des bébés viables en dehors de l'utérus (initiative sauver les bébés viables)'. 2023.

16. Confédération Suisse, Initiative populaire fédérale 'Pour un jour de réflexion avant tout avortement (initiative la nuit porte conseil)'. 2023.

17. Anna P, Cynthia B, Jonathan B. The state of global abortion data: an overview and call to action. BMJ Sexual &amp. Reprod Health. 2022;48(1):3–6.

18. Federal Statistical Office. Population. 2022 [cited 2025; Available from: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/population.html

19. World Health Organization, Family planning: a global handbook for providers. Family planning: a global handbook for providers., 2022.

20. Rey S, et al. Commission sur les données et la connaissance de l’IVG. IVG : État des lieux et perspectives d’évolution du système d’information. 2016, République française. Ministère des affaires sociales et de la santé: Paris.

21. Office fédéral de la statistique. Mariages, par canton et ville, de 1990 à 2022. 2023; Available from: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/asset/fr/27225469

22. Office fédéral de la statistique (OFS). Interruptions de grossesse. 2023 [cited 2024 23 April]; Available from: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/sante/etat-sante/reproductive/interruptions-grossesses.html

23. eurostat. Abortion indicators. 2024 [cited 2024 22 April]; Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/DEMO_FABORTIND/default/table?lang=en&category=demo.demo_fer

24. Office fédéral de la statistique (OFS). Nombre et taux d'interruptions de grossesse, selon le canton d'intervention. 2023 [cited 2024 23 April]; Available from: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/sante/etat-sante/reproductive/interruptions-grossesses.assetdetail.26386370.html

25. Fondation PR. Ateliers pour futurs parents. 2024; Available from: https://www.profa.ch/cp/ateliers#:~:text=Le%20Conseil%20en%20p%C3%A9rinatalit%C3%A9%20de%20la%20Fondation%20PROFA%20propose%20aux,nouveau%20r%C3%B4le%2C%20en%20toute%20s%C3%A9r%C3%A9nit%C3%A9

26. Lichtenstein Liljeblad K, Kopp Kallner H, Brynhildsen J. Risk of abortion within 1-2 years after childbirth in relation to contraceptive choice: a retrospective cohort study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2020 Apr;25(2):141–6.

27. Lociciro S, Spencer B. Evolution de l’interruption de grossesse dans le canton de Vaud 1990-2012. 2016.DOI: https://dx.doi.org/

28. Office fédéral de la statistique (OFS), Marché du travail: femmes et mère plus souvent actives qu'il y a vingt ans, in numerus. 2022.

29. Office fédéral de la statistique (OFS). Niveau de formation. 2023 [cited 2024 22 April]; Available from: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/education-science/indicateurs-formation/themes/effets/niveau-formation.html

30. Myat SM, Pattanittum P, Sothornwit J, Ngamjarus C, Rattanakanokchai S, Show KL, et al. School-based comprehensive sexuality education for prevention of adolescent pregnancy: a scoping review. BMC Womens Health. 2024 Feb;24(1):137. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-024-02963-x

31. Canton de Vaud, Le Canton de Vaud améliore l’accès à l’interruption de grossesse médicamenteuse. 2023.

32. Porchet L. L’avortement, une question de santé publique! 2023; Available from: https://leonoreporchet.ch/avortement-une-question-de-sante-publique/

33. Porchet L. Pour que l’avortement soit d’abord considéré comme une question de santé et non plus une affaire pénale. 2022; Available from: https://www.parlament.ch/fr/ratsbetrieb/suche-curia-vista/geschaeft?AffairId=20220432