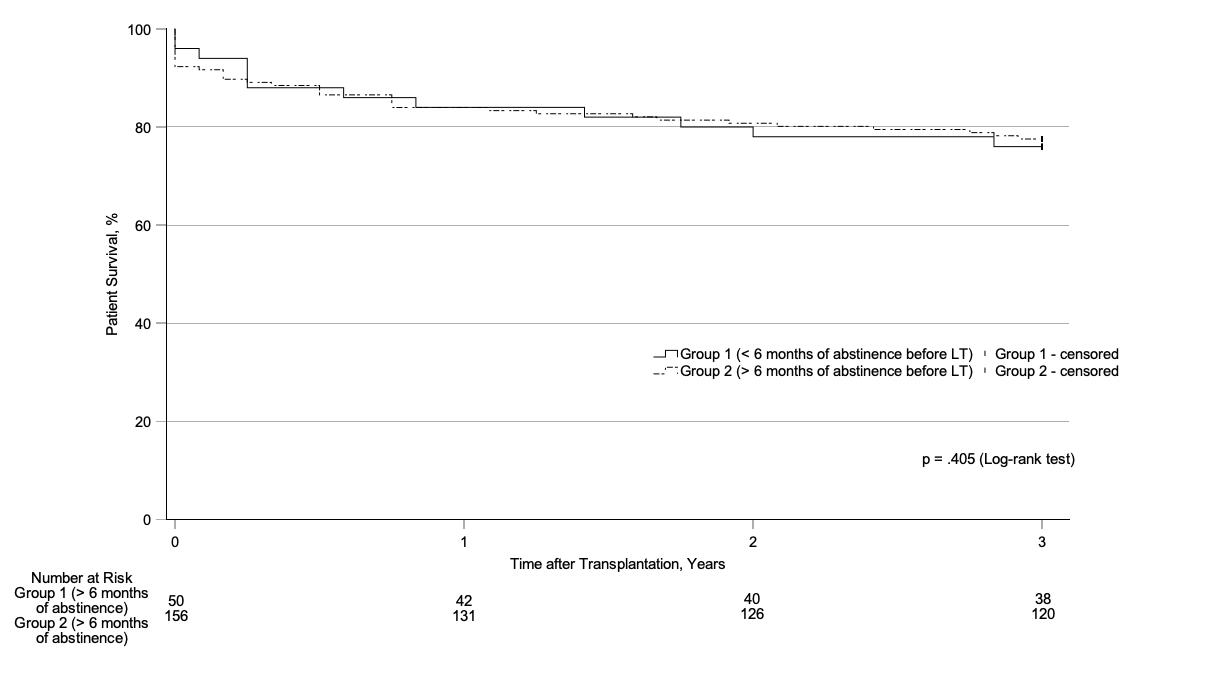

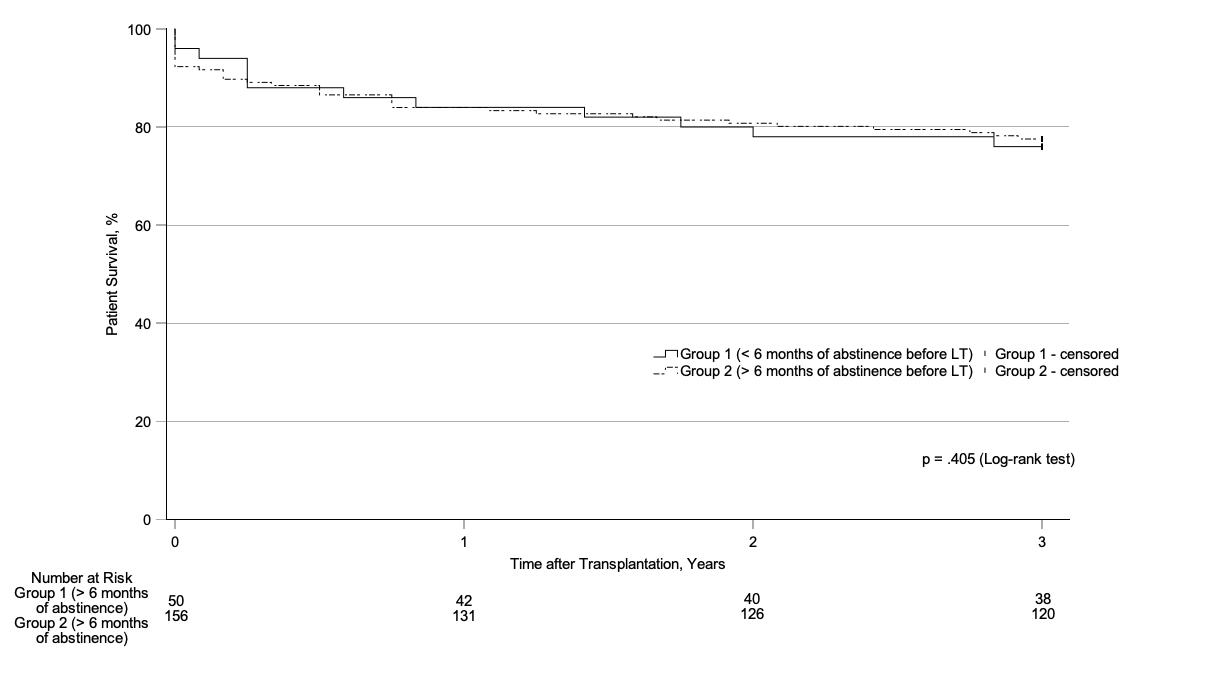

Figure 1Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival among patients with less than (group 1) or more than (group 2) 6 months of alcohol abstinence before listing for liver transplantation.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4381

interquartile range

Model for End-stage Liver Disease

quality of life

Swiss Transplant Cohort Study

Alcohol is a major risk factor for liver disease in general, particularly for alcohol-induced acute-on-chronic liver failure, severe alcohol-related hepatitis, and liver cirrhosis [1]. Alcohol-associated liver diseases are among the most common indications for liver transplantation [2–4]. Problematic alcohol consumption is also relevant to other patient groups requiring liver transplantation [1, 5].

Most European transplant centres require patients to abstain from alcohol for at least 6 months to be included on waiting lists to receive limited donor livers [5]. Although alcohol abstinence before liver transplantation decreases the need for liver transplantation and may be associated with lower rates of re-emerging harmful alcohol consumption after transplantation [6-8], delaying liver transplantation for several months is associated with a significant increase in mortality [8, 9]. Some patients die before or shortly after being placed on the waiting list because of delays due to not meeting the required alcohol abstinence period. For example, in the case of severe alcohol-associated hepatitis, the 6-month mortality rate is approximately 70%, and “early” liver transplantation is the only therapeutic approach that substantially increases survival [8–11]. To our knowledge, no studies have shown that a minimum duration of alcohol abstinence is superior to non-abstinence before listing for liver transplantation. The common requirement of 6 months of alcohol abstinence before listing was determined arbitrarily [12–16].

To date, the success of liver transplantation has been measured primarily by post-liver transplantation patient and graft survival and the occurrence of alcohol consumption, with little focus on patients’ general well-being [15]. However, recommendations from the European Association for the Study of the Liver suggest considering quality of life (QoL) as an outcome measure after liver transplantation, as transplantation aims not only to prolong life but also to restore psychological and social functioning. Moreover, impaired QoL is an early indicator of medical or psychosocial complications, which may affect long-term prognosis and require clinical evaluation and intervention [5].

Therefore, we conducted the first comparison of QoL and survival after liver transplantation between patients with less than (group 1) or more than (group 2) 6 months of alcohol abstinence before being listed for liver transplantation, independent of the primary liver disease. We hypothesised that the duration of alcohol abstinence before listing for transplantation would not significantly affect posttransplant survival and QoL in our study population. Our findings contribute to the debate regarding whether patients with less than 6 months of alcohol abstinence should be categorically excluded from liver transplantation waiting lists.

This retrospective, single-centre cohort study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Declaration of Istanbul [17, 18] and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Canton Zurich, Switzerland (BASEC number 2021-01839). The requirement for informed consent was waived because the study was deemed to pose minimal risk and used data collected as part of routine clinical practice. The research is reported in line with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines [19].

Patients who received their first liver transplant between January 2011 and December 2019 at the Transplantation Centre of the University Hospital Zurich, regardless of the primary indication for transplantation, and who were enrolled in the Swiss Transplant Cohort Study (STCS) were considered for inclusion. The STCS is a prospective, observational, multicentre cohort study enrolling patients undergoing solid organ transplantation in Switzerland, as described in detail elsewhere [20]. The exclusion criteria were age below 18 years at the time of transplantation, medical records indicating refusal to grant use of clinical data for research purposes, missing data, and acute liver failure.

All patients underwent a careful psychiatric examination before being placed on the waiting list for liver transplantation. Patients who had recently consumed alcohol were evaluated for their drinking habits and willingness to abstain from or decrease alcohol consumption to meet the indications for liver transplantation. All patients were offered psychiatric support before and after transplantation. The frequency of psychiatric consultations and the use of psychopharmaceuticals depended solely on the patients’ needs. A multidisciplinary transplant committee, including transplant surgeons, hepatologists, anaesthesiologists, consultation-liaison psychiatrists, and other members, was responsible for decision-making regarding liver transplantation listing. Liver transplantation and postoperative care were performed in line with the current standard of care.

Sociodemographic and medical information was abstracted from the patients’ electronic medical records and augmented by data from the STCS.

The exposure of interest was the duration of alcohol abstinence before placement on the waiting list for liver transplantation. Patients with less than 6 months of abstinence before listing (group 1) were compared with those with more than 6 months of abstinence (group 2). The time of abstinence before listing was determined using consultant psychiatrists’ reports and patients’ medical records. The outcomes of interest were patient survival time after liver transplantation and QoL at 12, 24, and 36 months after liver transplantation. Patient survival time was calculated as the time from the day of transplantation to the day of death and was reported in days. The follow-up period of 3 years began on the day of transplantation. QoL was assessed using a self-reported questionnaire from the STCS, which was completed at 12, 24, and 36 months after transplantation. Patients were asked to rate their QoL as the best reflection of their status during the prior week on a visual analogue scale from 0 (worst imaginable QoL; left) to 100 (perfect QoL; right). This scale is widely used in various settings and has high validity and reliability [21]. The questionnaire was available in English, German, French, and Italian.

Electronic medical records and STCS data were used to obtain information on patients’ sex (binary sex categorisation), age at liver transplantation, relationship status (categorised as single, in a relationship or married, widowed, or divorced) and monthly household net income (categorised as <CHF 4500, CHF 4500–6000, CHF 6000–9000, or >CHF 9000). Psychiatric support was defined as receiving psychiatric consultation at least once per month during the waiting list period and in the first 3 years after liver transplantation and recorded as a binary variable (yes or no). Alcohol consumption in the 6 months before and 3 years after liver transplantation was quantified according to the definitions of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the United States and the World Health Organization (no drinking; drinking in moderation, defined as alcohol consumption without meeting the criteria for heavy drinking; heavy drinking, defined as an average consumption of 50 grams of pure alcohol at least once per week, or 150 grams of pure alcohol per week, in men or 40 grams of pure alcohol at least once per week, or 80 grams of pure alcohol per week, in women) [1].

The following were also assessed: the uncorrected Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score [22] before placement on the waiting list for liver transplantation; the time between placement on the waiting list and liver transplantation; and disease leading to liver transplantation (six categories). Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma were classified according to the primary liver disease.

Race, ethnicity, and postoperative complications were not recorded.

Categorical variables are reported as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables are reported as the median and interquartile range (IQR) because the metric data were not normally distributed. The distribution of variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The assumption of sphericity was validated using Mauchly’s test of sphericity; if this assumption was violated, the Huynh-Feldt correction was applied.

Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Patient survival was analysed using Kaplan–Meier diagrams and log-rank tests. A multivariate Cox regression was used to further identify group effects with respect to patient survival. Changes in QoL were examined with multivariate ANOVA with repeated measures. Age and net monthly household income served as independent variables to assess confounders with respect to QoL. Furthermore, the uncorrected MELD score before liver transplantation and QoL measures at each data selection point, the time between listing and transplantation, and QoL measures were assessed using Spearman correlation to determine relationships between clinical characteristics and QoL.

An ɑ = 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance, and p-values and 95% confidence intervals were two-sided. Because of the study design, no data were missing. Analyses were performed in SPSS version 29.0 (IBM, 2022).

The study group consisted of 206 patients who underwent their first liver transplantation between January 2011 and December 2019 at the Transplantation Centre of the University Hospital Zurich. According to psychiatric examinations, 50 patients (group 1, 24%) had abstained from alcohol for less than 6 months before being listed for liver transplantation, of whom 6 (12%) showed moderate alcohol consumption and 44 (88%) showed heavy alcohol consumption. By contrast, 156 patients (group 2, 76%) had abstained from alcohol for more than 6 months before listing. The study cohort included 155 men (75%) and 51 women with a median (IQR) age at transplantation of 59 (53–64) years.

No significant differences were observed between groups in sex distribution, age at liver transplantation, relationship status, monthly household net income, uncorrected MELD score at listing, time between listing and transplantation, QoL, or alcohol consumption 3 years after liver transplantation. However, significantly more patients requested psychiatric support in the group with less than 6 months of alcohol abstinence before listing for liver transplantation (table 1).

Table 1Characteristics of patients with less than (group 1) or more than (group 2) 6 months of alcohol abstinence before listing for liver transplantation.

| Variable | Group 1 (n = 50) (<6 months of abstinence before listing) | Group 2 (n = 156) (>6 months of abstinence before listing) | p | ||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Sex | 0.110 | ||||

| Male | 42 | (84) | 113 | (72) | |

| Female | 8 | (16) | 43 | (28) | |

| Total | 50 | (100) | 156 | (100) | |

| Age at liver transplantation, years | |||||

| Median [IQR] | 60 | [52–64] | 59 | [53–64] | 0.811 |

| Relationship status | 0.709 | ||||

| Single | 3 | (7) | 13 | (9) | |

| In a relationship or married | 33 | (79) | 109 | (73) | |

| Widowed | 0 | (0) | 4 | (3) | |

| Divorced | 6 | (16) | 23 | (15) | |

| Total | 42 | (100) | 149 | (100) | |

| Monthly household net income | 0.726 | ||||

| <CHF 4500 | 15 | (40) | 53 | (39) | |

| CHF 4500–6000 | 12 | (32) | 40 | (30) | |

| CHF 6000–9000 | 2 | (5) | 31 | (23) | |

| >CHF 9000 | 9 | (24) | 11 | (8) | |

| Total | 38 | (100) | 135 | (100) | |

| Disease leading to liver transplantation | |||||

| Alcohol-related liver disease | 23 | (46) | 36 | (23) | |

| Non-alcohol-related steatohepatitis | 2 | (4) | 18 | (12) | |

| Hepatitis B, C, or D | 18 | (36) | 52 | (33) | |

| Autoimmune liver diseases | 2 | (4) | 25 | (16) | |

| Genetic liver diseases | 2 | (4) | 11 | (7) | |

| Other pathologies | 2 | (4) | 14 | (9) | |

| Total | 50 | (100) | 156 | (100) | |

| Alcohol consumption 6 months before listing | |||||

| No drinking | 0 | (0) | 156 | (100) | |

| Drinking in moderation | 6 | (12) | 0 | (0) | |

| Heavy drinking | 44 | (88) | 0 | (0) | |

| Total | 50 | (100) | 156 | (100) | |

| Alcohol consumption 3 years after liver transplantation | 0.566 | ||||

| No drinking | 36 | (72) | 152 | (98) | |

| Drinking in moderation | 9 | (18) | 3 | (2) | |

| Heavy drinking | 5 | (10) | 1 | (1) | |

| Total | 50 | (100) | 156 | (100) | |

| Psychiatric support | 0.032 | ||||

| No psychiatric support | 11 | (22) | 79 | (51) | |

| With psychiatric support | 39 | (78) | 76 | (49) | |

| Total | 50 | (100) | 156 | (100) | |

| QoL 12 months after liver transplantation | n = 42 | n = 131 | |||

| Median [IQR] | 74 | [58–89] | 78 | [61–88] | 0.551 |

| QoL 24 months after liver transplantation | n = 40 | n = 126 | |||

| Median [IQR] | 75 | [55–93] | 78 | [64–90] | .665 |

| QoL 36 months after liver transplantation | n = 38 | n = 120 | |||

| Median [IQR] | 80 | [56–92] | 78 | [63–90] | 0.701 |

n = sample size; ; CHF = Swiss franc; MELD = Model for End-stage Liver Disease; IQR = interquartile range; QoL = quality of life

Autoimmune liver diseases include primary sclerosing cholangitis, primary biliary cholangitis, and autoimmune hepatitis.

Genetic liver diseases include Wilson’s disease, cystic fibrosis, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, and hemosiderosis.

Other pathologies include secondary sclerosing cholangitis, amyloidosis, oxalosis, cholangiocarcinoma, and polycystic liver disease.

No drinking, defined as no alcohol consumption 6 months before placement on the waiting list for liver transplantation.

Drinking in moderation, defined as alcohol consumption without meeting the criteria for heavy drinking.

Heavy drinking, defined as average consumption of 50 grams of pure alcohol at least once per week, or 150 grams of pure alcohol per week, in men or 40 grams of pure alcohol at least once per week, or 80 grams of pure alcohol per week, in women.

Percentages may not total 100% because of rounding.

Categorical variables were compared using the Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test; continuous variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test.

No significant differences in survival after liver transplantation were observed between patients with less than (group 1) and more than (group 2) 6 months of abstinence before listing for liver transplantation; Chi2(1) = 0.694, p = 0.405 (figure 1).

Patients in both groups had similar 1-year survival (84% [95% CI, 71%; 92%] vs 84% [95% CI, 77%; 89%]), 2-year survival (78% [95% CI, 64%; 87%] vs 81% [95% CI, 74%; 86%]), and 3-year survival (76% [95% CI, 62%; 86%] vs 78% [95% CI, 70%; 83%]). Multivariate Cox regression analysis also indicated no significant effects of group (HR = 0.924, p = 0.814), sex (HR = 0.969, p = 0.928), or age at liver transplantation (HR = 1.030, p = 0.092) with respect to patient survival. In addition, the amount of alcohol consumed 6 months before listing had no influence on survival (supplementary materials 3 in the appendix). However, we could not reliably determine the effect of alcohol consumption after liver transplantation because only 12 patients (6%) reported moderate alcohol consumption and only 6 (3%) reported heavy drinking 3 years after transplantation (supplementary material 5 and 6 in the appendix). Furthermore, an analysis considering only patients undergoing transplantation specifically for alcohol-related liver disease indicated no relevant survival difference between patients with less than versus more than 6 months of abstinence before listing (supplementary material 1 in the appendix).

Figure 1Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival among patients with less than (group 1) or more than (group 2) 6 months of alcohol abstinence before listing for liver transplantation.

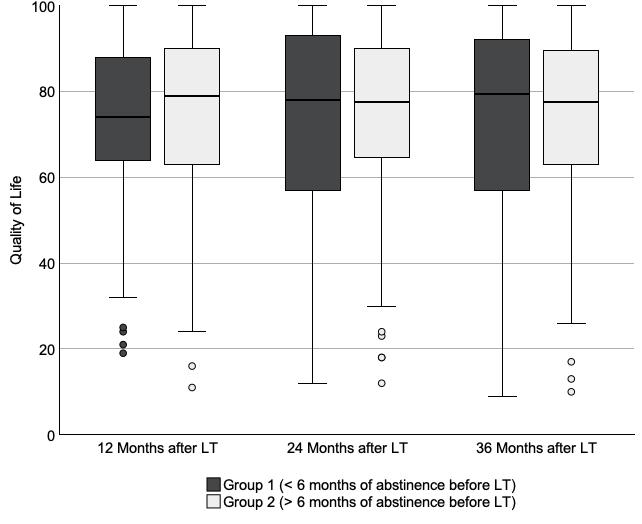

No significant differences in QoL measures were observed at 12, 24, and 36 months after liver transplantation between groups (table 1 and figure 2). In addition, we observed no significant changes in QoL over time within each group (F(2,24) = 0.814, p = 0.435) and no significant within-patient changes in QoL over time (F(2,410) = 0.798, p = 336), and the group effect was not significant (F(1,133) = 0.346, p = 0.557).

Figure 2Quality of life of patients with less than (group 1) and more than (group 2) 6 months of alcohol abstinence before being listed for liver transplantation. The box plots (with bars indicating median and IQR and whiskers indicating 95% confidence intervals) indicate quality of life from 0 (worst imaginable) to 100 (perfect) among study participants in group 1 and group 2 who were alive 12 months after transplantation (42 vs 131), 24 months after transplantation (40 vs 126), and 36 months after transplantation (38 vs 120). Circles (o) on the box plot indicate mild outliers (data points 1.5–3 times the interquartile range from the median). LLT = Liver transplantation.

However, age at liver transplantation (F(1,33) = 7.348, p = 0.008) and monthly household net income (F(1,133) = 7.391, p = 0.007) had a significant effect on QoL. Age at liver transplantation and monthly household net income showed weakly positive correlations with QoL at some time points, whereas higher uncorrected MELD scores and longer waiting times for liver transplantation were not associated with poorer or better QoL after transplantation (table 2).

Table 2Spearman correlations between patient characteristics and quality of life at 12, 24, and 36 months after liver transplantation. An absolute value of r <0.3 indicates a weak correlation.

| QoL at 12 months after liver transplantation | QoL at 24 months after liver transplantation | QoL at 36 months after liver transplantation | |

| Monthly household net income (CHF) | r = 0.195* | r = 0.141 | r = 0.199* |

| Age at liver transplantation (years) | r = 0.133 | r = 0.201* | r = 0.168* |

| Uncorrected MELD score before listing | r = 0.039 | r = –0.085 | r = –0.035 |

| Time between listing and liver transplantation (days) | r = –0.055 | r = 0.002 | r = –0.059 |

QoL = quality of life; CHF = Swiss franc; r = Spearman correlation coefficient; MELD = Model for End-stage Liver Disease

* p <0.05 (two-tailed) indicates a significant correlation

Moreover, we observed no differences between men (mean rank (MR) 12 months after liver transplantation = 84.72; MR 24 months after liver transplantation = 83,59; MR 36 months after liver transplantation = 79.94) and women (MR 12 months after liver transplantation = 93.91; MR 24 months after liver transplantation = 83.24; MR 36 months after liver transplantation = 78.17) in terms of QoL at 12 months (p = 0.297, U = 2498.00, z = -1.044, r = –0.079), 24 months (p = 0.968, U = 2633.50, z = –0.41, r = –0.032), and 36 months (p = 0.834, U = 2268.50, z = –0.210, r = –0.02) after liver transplantation. Likewise, the amount of alcohol consumed before listing for liver transplantation did not show any measurable effects on QoL outcomes (supplementary material 4 in the appendix), whereas QoL (and post-transplant survival) tended to be better among patients who received psychiatric support (supplementary materials 7 and 8 in the appendix).

The results by indication for transplantation revealed mixed QoL findings within these subgroups (supplementary material 2 in the appendix).

This retrospective study showed that survival and QoL in the first 3 years after liver transplantation did not differ between patients with less than or more than 6 months of alcohol abstinence before being listed for liver transplantation.

Although poorer survival was correlated with more advanced age, this trend was not statistically significant, and the age distribution did not significantly differ between cohorts. The 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year post-transplant survivals in our cohort were comparable to the reported survival rates after liver transplantation performed in the past decade in Europe [23]. Data from European transplant registries have also indicated that older patients have poorer survival than younger patients after liver transplantation; however, this finding may be due to the association between advanced age and increased mortality [24]. In previous studies limited to patients with alcohol-associated liver disease, some of which imposed highly restrictive inclusion criteria, patients with more than 6 months of alcohol abstinence also had similar survival rates to those with less than 6 months of abstinence after liver transplantation [8, 25].

The QoL scores in our cohorts remained stable over the study years and were similar to those observed in the general Swiss population, which has a mean QoL value of 75 out of 100 [26]. Although other studies have reported stable QoL scores after liver transplantation, these scores remained lower than those observed in the general population, in contrast to our findings [27, 28]. After liver transplantation, patients often feel abandoned and have difficulty returning to daily life; therefore, this vulnerable group is likely to benefit from psychiatric or psychological support [29–32]. This aspect might explain why the QoL among our study participants, many of whom received psychiatric care, was higher than that reported in the aforementioned studies. We observed that advanced age and high monthly household net income were associated with higher QoL, consistent with findings in the overall Swiss population.

We also found that the amount of alcohol consumed before listing did not affect survival, QoL, or alcohol intake after liver transplantation. However, we observed a trend suggesting that heavy alcohol consumption after transplantation may be associated with poorer outcomes, although this trend was not statistically significant due to the small sample size. This finding is consistent with results from Herrick-Reynolds et al. [25], who conducted a large single-centre cohort study comparing post-transplant patient survival, allograft survival, and relapse-free survival in patients with alcohol-associated liver diseases with less than or more than 6 months of abstinence before liver transplantation. Both groups also showed similar rates of patient and graft survival, as well as comparable alcohol relapse frequencies, but severe relapse was associated with poor post-transplant outcomes. These outcomes appeared to be nuanced and were influenced by alcohol use severity. Both this study and ours indicate that the binary distinction between drinking and non-drinking, as in the 6-month alcohol abstinence rule, is insufficient and that the amount of alcohol intake after liver transplantation should be considered. Because of the risk of patients concealing or underestimating their alcohol consumption due to shame or fear of not being considered for liver transplantation, information on alcohol consumption should ideally be verified with ethyl glucuronide testing in hair samples, as we previously performed in patients whose alcohol intake was uncertain [33].

The results of our study, along with recently published findings, suggest that new outcome variables such as QoL and the amount of alcohol consumed should be incorporated alongside commonly used measures such as survival to better reflect the complex medical and personal situation after liver transplantation [8, 11, 15, 25, 34]. Future studies should investigate interventions that improve post-transplant outcomes [8, 11, 16]. Our findings suggest that comprehensive psychiatric care for patients before and after liver transplantation may improve post-transplant survival and QoL and help reduce alcohol consumption. Notably, a significantly higher proportion of patients in the group with less than six months of alcohol abstinence before being listed for transplantation requested psychiatric support. Taken together, these observations provide a possible explanation for the absence of significant differences in survival and QoL between patients with less than and those with more than six months of alcohol abstinence in our study, but this remains to be confirmed.

In future prospective studies, the effects of various forms of psychotherapy, psychopharmaceuticals, and specialised substance use treatments on the newly defined outcome measures in patients before and after liver transplantation should be examined. Additionally, future investigations should explore how these findings can be applied in countries with less developed healthcare systems.

Our study has several limitations. First, the time of abstinence before listing was based primarily on information provided by the patients. At least 39 of 206 patients (19%) underwent ethyl glucuronide hair testing after providing questionable statements regarding alcohol consumption.

Second, patients in poor health might not have been able to complete the QoL questionnaire [34]. Moreover, because many instruments are available for assessing QoL, the results are difficult to compare across studies [29]. Our use of a widely used measurement method demonstrated to have strong validity and reliability across various settings, despite its simplicity and lack of multidimensionality, ensured the comparability of our QoL scores to those reported in numerous other studies [21].

We investigated patients who underwent liver transplantation for any indication because patients in Switzerland typically must abstain from alcohol for at least 6 months to be included on the waiting list for liver transplantation. To account for the role of alcohol consumption, we conducted subgroup analyses of survival and QoL according to the underlying condition leading to liver transplantation. However, owing to the limited sample size and the restriction of the study to only one centre, robust quantitative analyses were not feasible. Nevertheless, we conducted descriptive analyses to highlight potential trends.

Substantial strengths of our study include the similar patient composition between cohorts, the cohorts’ representativeness of the general Swiss population, and the minimal exclusion criteria.

The duration of alcohol abstinence before being listed for liver transplantation did not affect patients’ survival or QoL in the first 3 years after transplantation in this large Swiss cohort study, calling the 6-month alcohol abstinence requirement into question, as it hinders access to lifesaving transplantation in a large subset of patients. Further efforts are needed to establish new outcome variables such as QoL that holistically reflect patient status after transplantation.

Individual patient data will not be shared. Requests to access data from the Swiss Transplant Cohort Study should be directed to the Swiss Transplant Cohort Study (https://www.stcs.ch).

We thank Frederic Klein (Statistical Consulting; www.statistische-beratung.de; Munich; Germany) for statistical advice and all members of the Swiss Transplant Cohort Study for collecting part of the data used in this study. We thank Medical Journal Editors for English language editing of the manuscript.

Group Members of the Swiss Transplant Cohort Study

The members of the Swiss Transplant Cohort Study are as follows: Patrizia Amico, Adrian Bachofner, Vanessa Banz, Sonja Beckmann, Guido Beldi, Christoph Berger, Ekaterine Berishvili, Annalisa Berzigotti, Isabelle Binet, Pierre-Yves Bochud, Sanda Branca, Anne Cairoli, Emmanuelle Catana, Yves Chalandon, Sabina De Geest, Sophie De Seigneux, Joëlle Lynn Dreifuss, Michel Duchosal, Thomas Fehr, Sylvie Ferrari-Lacraz, Andreas Flammer, Jaromil Frossard, Déla Golshayan, Nicolas Goossens, Fadi Haidar, Dominik Heim, Christoph Hess, Sven Hillinger, Hans Hirsch, Patricia Hirt, Linard Hoessly, Günther Hofbauer, Uyen Huynh-Do, Nina Khanna, Michael Koller, Andreas Kremer, Thorsten Krueger, Christian Kuhn, Bettina Laesser, Frédéric Lamoth, Roger Lehmann, Alexander Leichtle, Oriol Manuel, Hans-Peter Marti, Michele Martinelli, Valérie McLin, Katell Mellac, Aurélia Merçay, Karin Mettler, Nicolas Müller, Ulrike Müller-Arndt, Mirjam Nägeli, Graziano Oldani, Manuel Pascual, Rosmarie Pazeller, Klara Posfay-Barbe, David Reineke, Juliane Rick, Simona Rossi, Fabian Rössler, Silvia Rothlin, Thomas Schachtner, Stefan Schaub, Dominik Schneidawind, Macé Schuurmans, Simon Schwab, Thierry Sengstag, Federico Simonetta, Jürg Steiger, Guido Stirnimann, Ueli Stürzinger, Christian Van Delden, Jean-Pierre Venetz, Jean Villard, Julien Vionnet, Caroline Wehmeier, Madeleine Wick, Markus Wilhelm, and Patrick Yerly.

Author contributions: Felix A. Fries and Andre Richter had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the work as a whole. All authors participated meaningfully in the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

The Swiss Transplant Cohort Study is supported by the Swiss National Foundation (https://www.snf.ch), Unimedsuisse (https://www.unimedsuisse.ch), and the transplant centres. Sena Blümel was supported by fellowships from the University of Zurich (Walter and Gertrud Siegenthaler Fellowship, Hartmann Mueller Foundation and Fonds zur Foerderung des Akademischen Nachwuchses) and from the Novartis Foundation of Biomedical Research (grant number 23A064).

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript was disclosed.

1. World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

2.Cholankeril G, Ahmed A. Alcoholic Liver Disease Replaces Hepatitis C Virus Infection as the Leading Indication for Liver Transplantation in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Aug;16(8):1356–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.11.045

3.Thursz M, Gual A, Lackner C, Mathurin P, Moreno C, Spahr L, et al.; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol. 2018 Jul;69(1):154–81. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.018

4.Haldar D, Kern B, Hodson J, Armstrong MJ, Adam R, Berlakovich G, et al.; European Liver and Intestine Transplant Association (ELITA). Outcomes of liver transplantation for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: A European Liver Transplant Registry study. J Hepatol. 2019 Aug;71(2):313–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2019.04.011

5.Samuel D, De Martin E, Berg T, Berenguer M, Burra P, Fondevila C, et al.; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2024 Dec;81(6):1040–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2024.07.032

6.Schmeding M, Heidenhain C, Neuhaus R, Neuhaus P, Neumann UP. Liver transplantation for alcohol-related cirrhosis: a single centre long-term clinical and histological follow-up. Dig Dis Sci. 2011 Jan;56(1):236–43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-010-1281-7

7.Fung JY. Liver transplantation for severe alcoholic hepatitis-The CON view. Liver Int. 2017 Mar;37(3):340–2. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13286

8.Louvet A, Labreuche J, Moreno C, Vanlemmens C, Moirand R, Féray C, et al.; QuickTrans trial study group. Early liver transplantation for severe alcohol-related hepatitis not responding to medical treatment: a prospective controlled study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 May;7(5):416–25. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00430-1

9.Mathurin P, Moreno C, Samuel D, Dumortier J, Salleron J, Durand F, et al. Early liver transplantation for severe alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2011 Nov;365(19):1790–800. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1105703

10.Lee BP, Mehta N, Platt L, Gurakar A, Rice JP, Lucey MR, et al. Outcomes of early liver transplantation for patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2018 Aug;155(2):422–430.e1. doi: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.009

11.Mathurin P, Lucey MR. Liver transplantation in patients with alcohol-related liver disease: current status and future directions. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 May;5(5):507–14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30451-0

12.Brown RS Jr. Transplantation for alcoholic hepatitis – time to rethink the 6-month “rule”. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(19):1836–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe1110864

13.Dew MA, DiMartini AF, Steel J, De Vito Dabbs A, Myaskovsky L, Unruh M, et al. Meta-analysis of risk for relapse to substance use after transplantation of the liver or other solid organs. Liver Transpl. 2008 Feb;14(2):159–72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.21278

14.Pfitzmann R, Schwenzer J, Rayes N, Seehofer D, Neuhaus R, Nüssler NC. Long-term survival and predictors of relapse after orthotopic liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2007 Feb;13(2):197–205. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.20934

15.Germani G, Mathurin P, Lucey MR, Trotter J. Early liver transplantation for severe acute alcohol-related hepatitis after more than a decade of experience. J Hepatol. 2023 Jun;78(6):1130–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.03.007

16.Addolorato G, Mirijello A, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, D’Angelo C, Vassallo G, et al.; Gemelli OLT Group. Liver transplantation in alcoholic patients: impact of an alcohol addiction unit within a liver transplant center. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013 Sep;37(9):1601–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12117

17.World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013 Nov;310(20):2191–4. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053

18.Abboud O, Abbud-Filho M, Abdramanov K, et al.; International Summit on Transplant Tourism and Organ Trafficking. The declaration of Istanbul on organ trafficking and transplant tourism. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008 Sep;3(5):1227–31. doi: https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.03320708

19.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007 Oct;370(9596):1453–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X

20.Koller MT, van Delden C, Müller NJ, Baumann P, Lovis C, Marti HP, et al. Design and methodology of the Swiss Transplant Cohort Study (STCS): a comprehensive prospective nationwide long-term follow-up cohort. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013 Apr;28(4):347–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-012-9754-y

21.Feng Y, Parkin D, Devlin NJ. Assessing the performance of the EQ-VAS in the NHS PROMs programme. Qual Life Res. 2014 Apr;23(3):977–89. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-013-0537-z

22.Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, Kremers W, Therneau TM, Kosberg CL, et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2001 Feb;33(2):464–70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2001.22172

23.Adam R, Karam V, Cailliez V, O Grady JG, Mirza D, Cherqui D, et al.; all the other 126 contributing centers (www.eltr.org) and the European Liver and Intestine Transplant Association (ELITA). 2018 Annual Report of the European Liver Transplant Registry (ELTR) - 50-year evolution of liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2018 Dec;31(12):1293–317. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/tri.13358

24.Adam R, Karam V, Delvart V, O’Grady J, Mirza D, Klempnauer J, et al.; All contributing centers (www.eltr.org); European Liver and Intestine Transplant Association (ELITA). Evolution of indications and results of liver transplantation in Europe. A report from the European Liver Transplant Registry (ELTR). J Hepatol. 2012 Sep;57(3):675–88. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.015

25.Herrick-Reynolds KM, Punchhi G, Greenberg RS, Strauss AT, Boyarsky BJ, Weeks-Groh SR, et al. Evaluation of Early vs Standard Liver Transplant for Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease. JAMA Surg. 2021 Nov;156(11):1026–34. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.3748

26. OECD. How’s Life? 2020. Paris: OECS Publishing; 2020.

27.Wang GS, Yang Y, Li H, Jiang N, Fu BS, Jin H, et al. Health-related quality of life after liver transplantation: the experience from a single Chinese center. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2012 Jun;11(3):262–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1499-3872(12)60158-1

28.Burra P, Germani G. Long-term quality of life for transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2013 Nov;19 Suppl 2:S40–3. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.23725

29.Onghena L, Develtere W, Poppe C, Geerts A, Troisi R, Vanlander A, et al. Quality of life after liver transplantation: state of the art. World J Hepatol. 2016 Jun;8(18):749–56. doi: https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v8.i18.749

30.Grover S, Sarkar S. Liver transplant-psychiatric and psychosocial aspects. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2012 Dec;2(4):382–92. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jceh.2012.08.003

31.Goetzmann L, Klaghofer R, Wagner-Huber R, et al. Quality of life and psychosocial situation before and after a lung, liver or an allogeneic bone marrow transplant. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136(17-18):281.

32.Chiu NM, Chen CL, Cheng AT. Psychiatric consultation for post-liver-transplantation patients. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009 Aug;63(4):471–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.01987.x

33.Pragst F, Balikova MA. State of the art in hair analysis for detection of drug and alcohol abuse. Clin Chim Acta. 2006 Aug;370(1-2):17–49. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2006.02.019

34.Åberg F. Quality of life after liver transplantation. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;46-47:101684. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2020.101684

35.Tome S, Wells JT, Said A, Lucey MR. Quality of life after liver transplantation. A systematic review. J Hepatol. 2008 Apr;48(4):567–77. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2007.12.013

The appendix is available in the pdf version of the article at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4381.