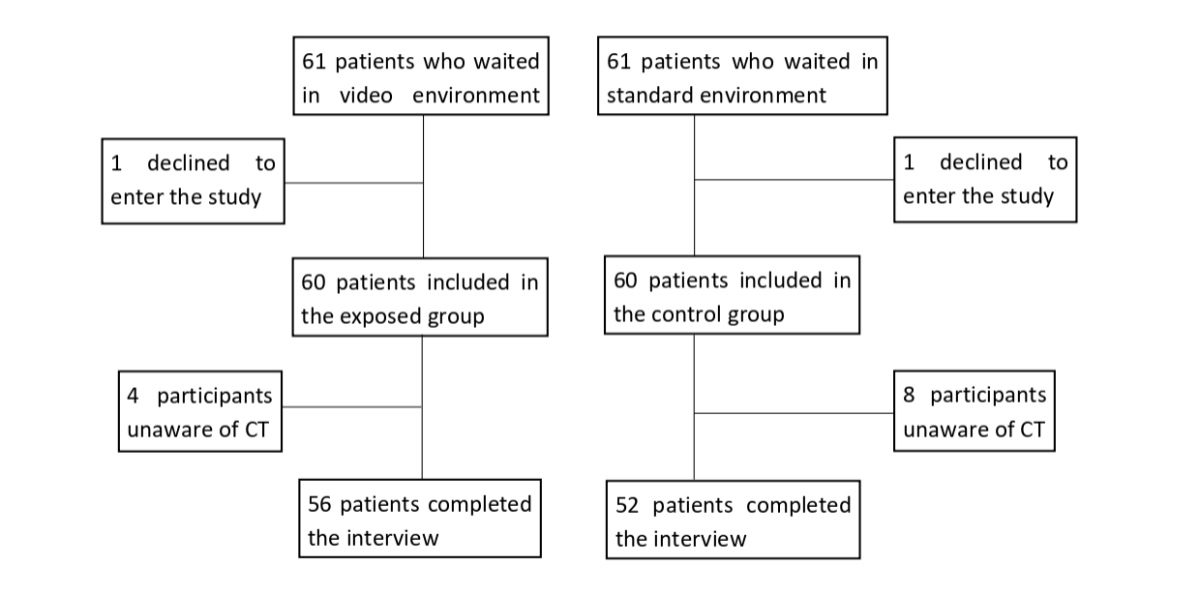

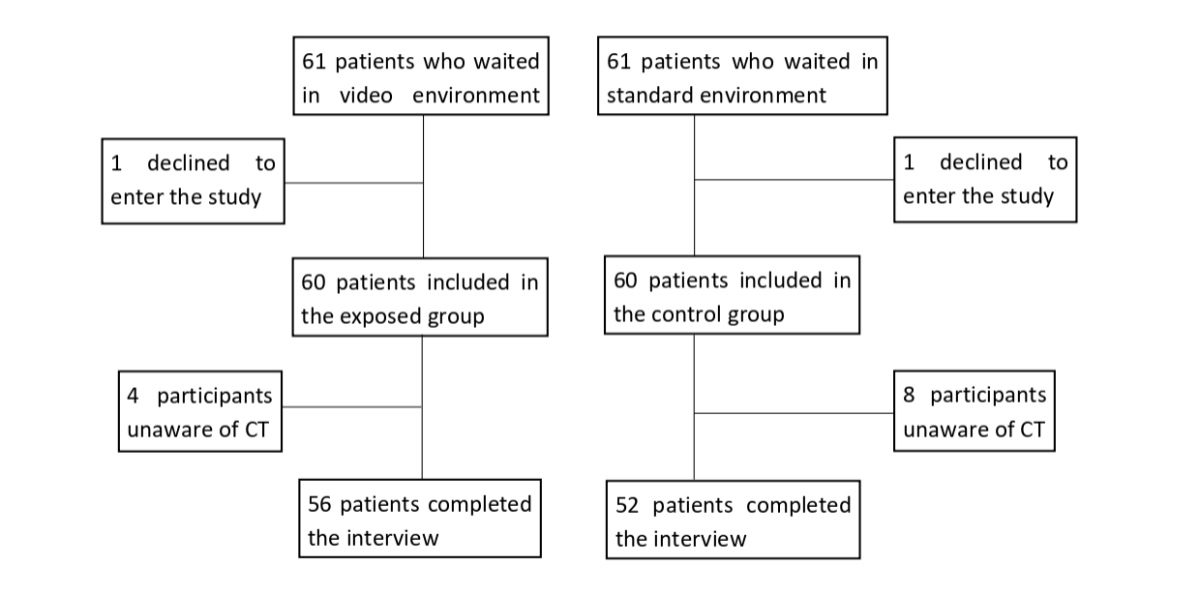

Figure 1Flowchart. CT: Chlamydia trachomatis.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4329

Chlamydia trachomatis is the most common bacterial sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the world, affecting about 3.2% of people aged 15–49 years in 2020 [1]. In French-speaking Switzerland, the disease affected 4.6% of women aged 18 years in 2013 [2]. Young women are over-represented among those diagnosed worldwide [1, 3–8, 14]. This over-representation can be attributed to several factors: their anatomy, which makes them more vulnerable to infections, as well as risky sexual behaviour, such as inconsistent use of condoms. In addition, limited access to sexual health education and preventive care can also contribute to this situation, highlighting the need for increased awareness and targeted health programmes for this population [30].

Chlamydia trachomatis is commonly involved in lower genital tract infections. Although the majority of infected women do not experience any symptoms, 5–30% will develop symptomatic disease ranging from urethritis to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) [9, 10, 31]. Pelvic inflammatory disease increases the risk of tubal infertility, ectopic pregnancy and chronic abdominopelvic pain, even after asymptomatic infection [10–15].

Nucleic acid amplification tests identifying Chlamydia trachomatis in urine or genital swabs is the gold standard diagnostic test [3, 9]. Routine annual screening for Chlamydia trachomatis in young women is recommended in the USA [3] and several European countries [16, 17]. Currently no official national screening recommendation exists in Switzerland, where knowledge surrounding sexually transmitted infections is transmitted through school sex education and healthcare professionals.

The literature reveals that adolescents and young adults have a low level of knowledge on sexually transmitted infections [18–23]. Authors have tried various interventions to improve this situation. Jaworski et al. [24] and Goldsberry et al. [25] showed that in-person educational interventions aimed at preventing sexually transmitted infections have the potential to sustainably improve young peoples’ knowledge of sexually transmitted infections, though pre- and post-intervention infection rates were not measured. Warner et al. [32] are, to our knowledge, the only group to have used a broadcasted video in a waiting room as an educational intervention. They showed a 10% reduction in new infection after exposure to the video among male patients only; patients’ foundational knowledge was not evaluated.

Video intervention is staff-sparing and easy to implement. If this intervention is proven effective, it would be easy to keep it permanently in our service, which would not be the case with a staff-demanding, more-invasive procedure. Screens benefit from great attractiveness within the public space and videos are omnipresent in the media. Thus, the video format appears to be a high-potential tool for prevention of sexually transmitted infections and was chosen to be this study’s centre of interest.

The primary goal of this study was to evaluate participants’ foundational knowledge regarding Chlamydia trachomatis and to assess the impact of an educational video displayed in the waiting room of a gynaecology emergency department on participants’ knowledge. The secondary goal was to explore participants’ perception of existing primary prevention tools for reducing the spread of Chlamydia trachomatis.

The study was performed in the gynaecology emergency department of Lausanne University Hospital in Switzerland. It was a prospective, interventional, controlled, non-randomised study. Participants were recruited between January and June 2022. Neither patients nor the public were involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of the research.

Eligible participants were women aged 15 to 35 years visiting the gynaecology emergency department. Participants with severe pain or serious psychological distress were excluded. Participants who were not able to consent or did not speak French were excluded as the video subtitles are in French. Participants who were completely unaware of the existence of Chlamydia trachomatis were excluded.

The Cantonal Commission for Ethics in Human Research approved the protocol (CER-VD Req-2021-00126).

The intervention consisted of passive exposure to a 2-minute cartoon subtitled in French presenting basic foundational points of Chlamydia trachomatis. It was displayed on a widescreen TV visible to every patient in the waiting room. In between Chlamydia trachomatis videos, 5 minutes of various medical information was displayed. Two A3 posters with the same key messages and QR codes referring to the original video with sound were also hung in the waiting room. The video was shown on alternate days to allow recruitment of the control and intervention groups in the same period. The video was created by a Belgian foundation and used with their permission [29].

The exposed group was recruited on days on which the video was displayed and the control group on days on which it was not displayed. To ensure adequate video exposure, participants of the exposed group had to have been sitting in the waiting room for at least 30 minutes for the intervention to be considered valid. Participants were not explicitly informed of the video’s presence.

All patients meeting the inclusion criteria were directly approached by SP in the waiting room, their number being limited only by logistical constraints (availability of the consulting room, working hours of SP). The total number of patients approached was 122. They were asked if they were interested in participating in a study in the form of a short questionnaire during their waiting time. In case of a positive answer, extended information about the study was then given to potential participants in a separate consulting room and oral consent was requested. The anonymous and voluntary nature of participation was made clear to the participants, as well as the possibility of withdrawing from the study during the interview without needing to provide justification. Participants were informed that withdrawal of consent after entry into the database would not be possible (because data were not identifiable) and that the data collected would still be analysed so as not to prejudice the project.

After the intervention or after a short time in the waiting room for the control group, a three-section in-person interview was performed. The first section focused on the participant’s sociodemographic information and identified participants unaware of the existence of Chlamydia trachomatis. The second section consisted of 40 closed theoretical questions about Chlamydia trachomatis (table 2): 18 questions had been answered in the video, 22 had not. During the third section (qualitative arm), participants were asked to share their personal involvement with Chlamydia trachomatis prevention. All answers were transcribed. The interview was concluded by correcting the participant’s errors and answering their questions related to sexually transmitted infections. Questions were partly inspired by a Swiss study on young people’s knowledge about Chlamydia trachomatis [22].

The primary outcome consisted of two scores from the interview. The first score referred to as the “A score” reflected the answers to the 18 questions whose answers were given in the video and thus potentially influenced by the intervention. A correct answer was scored 1 point and an incorrect answer 0. The total score was rated out of 18.

The secondary score referred as the “B score” reflected the answers to the 22 questions whose answers were not given in the video and thus not influenced by the intervention. A correct answer was scored 1 point and an incorrect answer 0. The total score was rated out of 22.

A low “A score” was defined as a score below the 25th percentile of all answers. A low “B score” was defined similarly.

The secondary outcome matches the qualitative analysis of answers to the third section of the interview.

Participant age was divided into categories: 15–18 years, 19–22 years, 23–26 years, 27–30 years and 31–35 years. Waiting time in the waiting room (in minutes) was collected. Educational level was classified as compulsory school, high school, vocational training or tertiary education. Training or education specifically in the health field and participation in school-based sex education was collected. Information regarding any previous consultations with a gynaecologist or at a sexual health clinic was also collected. Presence or absence of previous sexual intercourse was noted as well as sexual orientation and history of past Chlamydia trachomatis infection concerning the participant or a close relative of hers.

Regarding the third goal, a qualitative thematic analysis was carried out according to Kiger and Varpio [27], i.e.: creation of codes and search for themes through an inductive approach; analysis by re-reading the data […]; […] brief description of each theme; writing up the results. This method of analysis is recommended for understanding experiences and thoughts reported in a database [28].

Baseline characteristics of patients are presented in counts (n) and proportions (%) with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The participants’ mean age was also reported with the associated standard deviation (SD). The mean difference between the average A score of the exposed and the control group was assessed by student’s t-test. The association between the intervention and having a low A and B score was assessed using a univariate logistic regression and reporting an odds ratio. A multivariate regression was then performed using a model adjusted with all covariates that were unbalanced between groups, defined as a standardised difference (Std Diff) greater than 10%. Risk factors of having a low A and B score, defined as a score below the 25th percentile, were explored using a multivariate logistic regression following the selection of variables described by Hosmer and Lemshow [29].

Statistical analyses were performed with the software STATA version 17.0 (StataCorp, USA). A 95% CI and a p-value <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The sample size calculation indicated a minimum number of 120 participants to reveal a significant difference of 30% between the two groups with a power of 0.8 and a double-tailed statistical significance set at p <0.05.

Among 122 patients invited to participate, only two declined (figure 1). A total of 120 participants (60 in the exposed group and 60 in the control group) were recruited during their daytime visit to the gynaecology emergency department. Among them, 10% (12/120) were not aware of the existence of Chlamydia trachomatis and thus did not complete the second part of the interview.

Figure 1Flowchart. CT: Chlamydia trachomatis.

The mean waiting time in the waiting room for the exposed group was 53 minutes (±27).

Demographic data are shown in table 1. The mean age was similar in both groups: 22.4 years (±4.5) in the exposed group and 22.9 years (±4.2) in the control group. School-based sex education had been received by 95% (53) and 92% (48) of participants in the exposed and control group, respectively. Among participants in the exposed group, 30% (17/56) reported that they personally and/or a close relative of theirs had already had Chlamydia trachomatis; as compared to27% (14/52) in the control group. Both groups were similar regarding other sociodemographic variables (table 2). In the exposed group, 22% (25/56) participants viewed the video in its entirety at least once, 35% (16/56) viewed it only partially and 37% (15/56) did not notice it. No participants used the QR code referring to the original video with sound. Half of the participants had been made aware of Chlamydia trachomatis by health professionals (n = 54, 49%), one third by their family, friends and social networks (n = 39, 36%) and one fifth by school (n = 22, 20%).

Table 1Demographic data.

| Total (n = 108) | Exposed group (n = 56) | 95% confidence interval | Control group (n = 52) | 95% confidence interval | |||||

| Age in years | Mean and SD | 22.6 | 4.3 | 22.4 | 4.5 | 22.9 | 4.2 | ||

| Age category, n and % | 15–18 years | 25 | 23% | 16 | 29% | 13–20 | 9 | 17% | 9–11 |

| 19–22 years | 30 | 28% | 14 | 25% | 11–17 | 16 | 31% | 12–20 | |

| 23–26 years | 33 | 31% | 15 | 27% | 12–18 | 18 | 35% | 14–22 | |

| 27–30 years | 16 | 15% | 8 | 14% | 6–10 | 8 | 15% | 6–10 | |

| 31–35 years | 4 | 4% | 3 | 5% | 2–4 | 1 | 2% | 1–2 | |

| Educational level | Compulsory school | 18 | 17% | 11 | 20% | 8–14 | 7 | 13% | 5–9 |

| High school | 36 | 33% | 21 | 38% | 16–25 | 15 | 29% | 11–19 | |

| Vocational training | 20 | 19% | 10 | 18% | 8–13 | 10 | 19% | 7–12 | |

| Tertiary education | 34 | 31% | 14 | 25% | 11–17 | 20 | 38% | 15–24 | |

| Training in the health field | Yes | 12 | 11% | 4 | 7% | 3–5 | 8 | 15% | 6–10 |

| Sexual education at school | Yes | 101 | 94% | 53 | 95% | 48–55 | 48 | 92% | 43–51 |

| Gynaecologist consultation habits | Never | 17 | 16% | 10 | 18% | 8–13 | 7 | 13% | 5–9 |

| At least once | 91 | 84% | 46 | 82% | 39–50 | 45 | 29% | 11–19 | |

| Previous consultation at sexual health clinic | Never | 77 | 71% | 40 | 71% | 33–45 | 37 | 71% | 31–42 |

| At least once | 31 | 29% | 16 | 29% | 13–20 | 15 | 29% | 11–19 | |

| Has ever been sexually active | Heterosexual | 92 | 85% | 44 | 79% | 38–50 | 48 | 92% | 43–51 |

| Homo/bisexual | 6 | 6% | 4 | 7% | 3–5 | 2 | 4% | 2–3 | |

| Positive history of past Chlamydia infection (herself or a close relative) | 31 | 29% | 17 | 30% | 13–21 | 14 | 27% | 11–18 | |

SD: standard deviation.

Answers to the interview questions are provided in table 2. Most questions (70%) had a correct answer rate of 50% or higher in both groups. Four questions had a 100% correct answer rate; all of these were addressed in the video.

Table 2Participants’ answers to the semi-structured interview: knowledge questions, correct answers and correct answer rate. * indicates questions whose answer was contained in the video.

| Question (correct answer) | Exposed group: correct answer rate, % (n) | 95% CI | Control group: correct answer rate, % (n) | 95% CI | |

| 1. Does the infection only affect women? * (No) | 85% (44) | 74–93 | 88% (46) | 77–95 | |

| 2. Do you think that women over 25 are more affected by the infection than those under 25? * (No) | 68% (38) | 56–78 | 73% (38) | 61–83 | |

| 3. How do you think you get Chlamydia? | 3.1. By kissing an infected person? (No) | 57% (32) | 46–67 | 71% (37) | 60–81 |

| 3.2. By unprotected vaginal intercourse? * (Yes) | 100% (56) | 94–100 | 100% (52) | 93–100 | |

| 3.3. By unprotected oral sex? * (Yes) | 68% (38) | 57–78 | 56% (29) | 45–66 | |

| 3.4. Through unprotected anal sex? * (Yes) | 66% (37) | 55–76 | 63% (33) | 52–73 | |

| 3.5. By contact with contaminated blood? (Yes) | 41% (23) | 33–50 | 54% (28) | 44–684 | |

| 3.6. By transmission from mother to child during delivery if the mother is infected? * (Yes) | 50% (28) | 40–60 | 37% (19) | 29–45 | |

| 4. What do you think are the possible symptoms of Chlamydia infection in women? | 4.1. Blood in stool (No) | 16% (9) | 12–20 | 42% (22) | 33–51 |

| 4.2. Burning and pain when urinating (Yes) | 91% (51) | 81–97 | 83% (43) | 71–91 | |

| 4.3. Abnormal or new vaginal discharge (Yes) | 98% (55) | 90–100 | 90% (47) | 79–96 | |

| 4.4. Bleeding outside the period (Yes) | 34% (19) | 27–42 | 50% (26) | 40–60 | |

| 4.5. Pimples or redness on the vulva/genital area (No) | 11% (6) | 8–14 | 8% (4) | 6–10 | |

| 4.6. No symptoms * (Yes) | 88% (49) | 77–95 | 92% (48) | 81–98 | |

| 4.7. Abdominal pain (Yes) | 70% (39) | 58–80 | 65% (34) | 53–75 | |

| 5. In your opinion, do most women who have a Chlamydia infection have symptoms that can alert them? * (No) | 41% (23) | 33–50 | 40% (21) | 32–49 | |

| 6. Do all men infected with Chlamydia have symptoms? * (No) | 77% (43) | 66–86 | 87% (45) | 76–94 | |

| 7. What are the possible consequences of a Chlamydia infection if it is not treated quickly? | 7.1. Long-term abdominal pain (Yes) | 23% (13) | 18–29 | 31% (16) | 24–38 |

| 7.2. Ectopic pregnancy * (Yes) | 59% (33) | 48–69 | 42% (22) | 33–51 | |

| 7.3. Sterility/infertility * (Yes) | 88% (49) | 77–95 | 85% (44) | 74–93 | |

| 7.4. Cervical cancer (No) | 16% (9) | 12–20 | 19% (10) | 15–24 | |

| 7.5. Partner infected * (Yes) | 100% (56) | 94–100 | 100% (52) | 93–100 | |

| 8. Can the infection make men infertile? (No) | 20% (11) | 15–25 | 31% (16) | 24–38 | |

| 9. Can you get Chlamydia again after you have already been treated for it? * (Yes) | 86% (48) | 75–93 | 83% (43) | 71–91 | |

| 10. What are the safe ways to avoid getting Chlamydia? | 10.1. Taking the contraceptive pill (No) | 88% (49) | 77–95 | 96% (50) | 87–100 |

| 10.2. Use condoms * (Yes) | 100% (56) | 94–100 | 100% (52) | 93–100 | |

| 10.3. Avoid having blood and/or semen in the mouth (Yes) | 39% (22) | 31–47 | 37% (19) | 29–45 | |

| 10.4. Wash before sex (No) | 82% (46) | 71–90 | 79% (41) | 67–88 | |

| 10.5. Wash after sex (No) | 70% (39) | 58–80 | 65% (34) | 53–75 | |

| 11. In your opinion, when/where should a person get tested? | 11.1. Any woman under 25 who has ever had sex (Yes) | 63% (35) | 52–73 | 73% (38) | 61–83 |

| 11.2. Any woman under 25 with a new sexual partner (Yes) | 91% (51) | 80–97 | 94% (49) | 84–98 | |

| 11.3. After unprotected sex with a person who does not know if they are infected with Chlamydia or not (Yes) | 100% (56) | 94–100 | 100% (52) | 93–100 | |

| 11.4. If his/her sexual partner has a positive result for another sexually transmitted infection (Yes) | 95% (53) | 85–99 | 98% (51) | 90–100 | |

| 12. How is a Chlamydia test done? | 12.1. By blood test (No) | 14% (8) | 11–18 | 17% (9) | 13–22 |

| 12.2. By urinalysis * (Yes) | 68% (38) | 57–78 | 69% (36) | 57–79 | |

| 12.3. By vaginal smear * (Yes) | 98% (55) | 90–100 | 96% (50) | 87–100 | |

| 13. How is a Chlamydia infection treated? | 13.1. With a cream (No) | 61% (34) | 50–71 | 52% (27) | 42–62 |

| 13.2. With antibiotics * (Yes) | 84% (47) | 73–92 | 90% (47) | 79–96 | |

| 13.3. With vitamins (No) | 86% (48) | 75–93 | 81% (42) | 69–90 | |

| 14. Should the sexual partner(s) of a person who has a Chlamydia infection also be treated? * (Yes) | 100% (56) | 94–100 | 100% (52) | 93–100 | |

Questions with the lowest correct answer rate were about symptoms of Chlamydia trachomatis, potential complications and screening methods. The question “Is blood in stool a symptom of Chlamydia infection?” was the only one to show a significant difference in correct answer rate between the two groups: 16% (95% CI: 7.6–28.2) in the exposed group vs 42% (95% CI: 28.5–56.5) in the control group. This symptom, which is not related to Chlamydia trachomatis, was not discussed in the video.

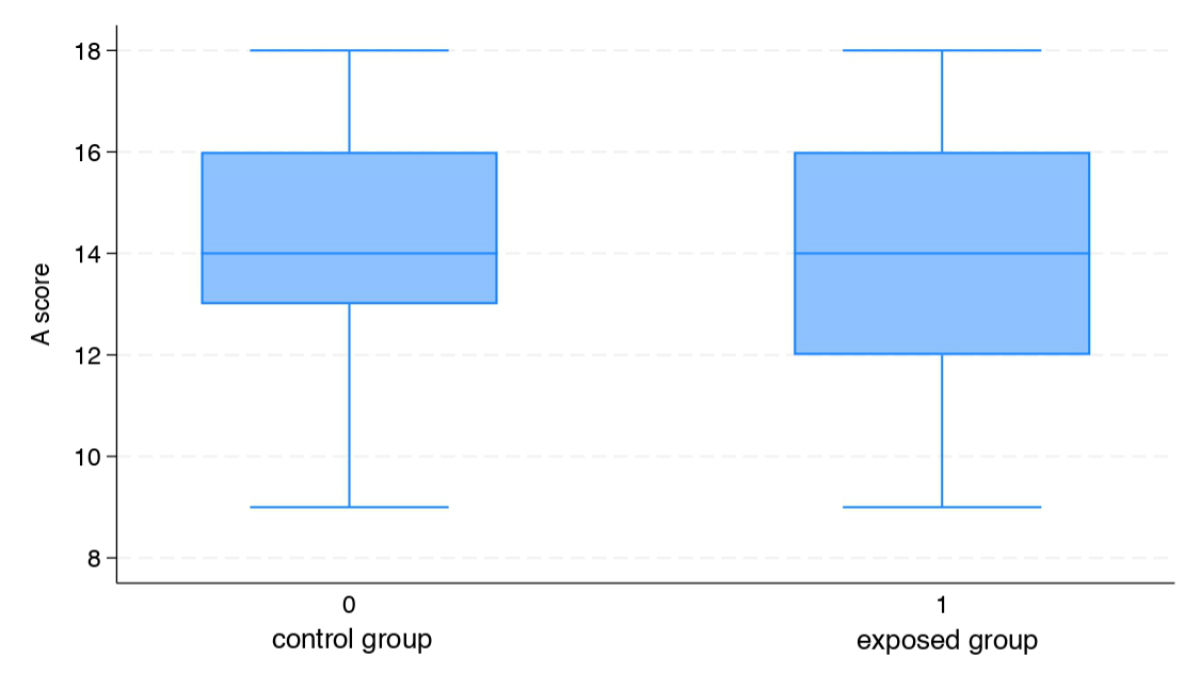

The average A score was 14.2 points (SD: ±2.6) and 14.0 points (SD: ±2.3) out of 18, in the exposed and control group, respectively, and no significant difference was reported when comparing the two groups (p = 0.77) (figure 2).

Figure 2Average A score.

Video exposure was not associated with diminution of lower scores (crude OR: 1.2, 95% CI: 0.5–2.9). In the multivariate model, results were similar with an adjusted OR of 1.02 (95% CI: 0.4–2.61), after adjustment with the unbalanced cofactors, defined as a standardised difference of more than 10% between groups (participants’ age, sexual orientation, consultation habits and level or field of education).

No risk factors of having a low score in the interview – defined as a score below the 25th percentile – were reported among the selected covariates (participants’ age, sexual orientation, consultation habits and level or field of education).

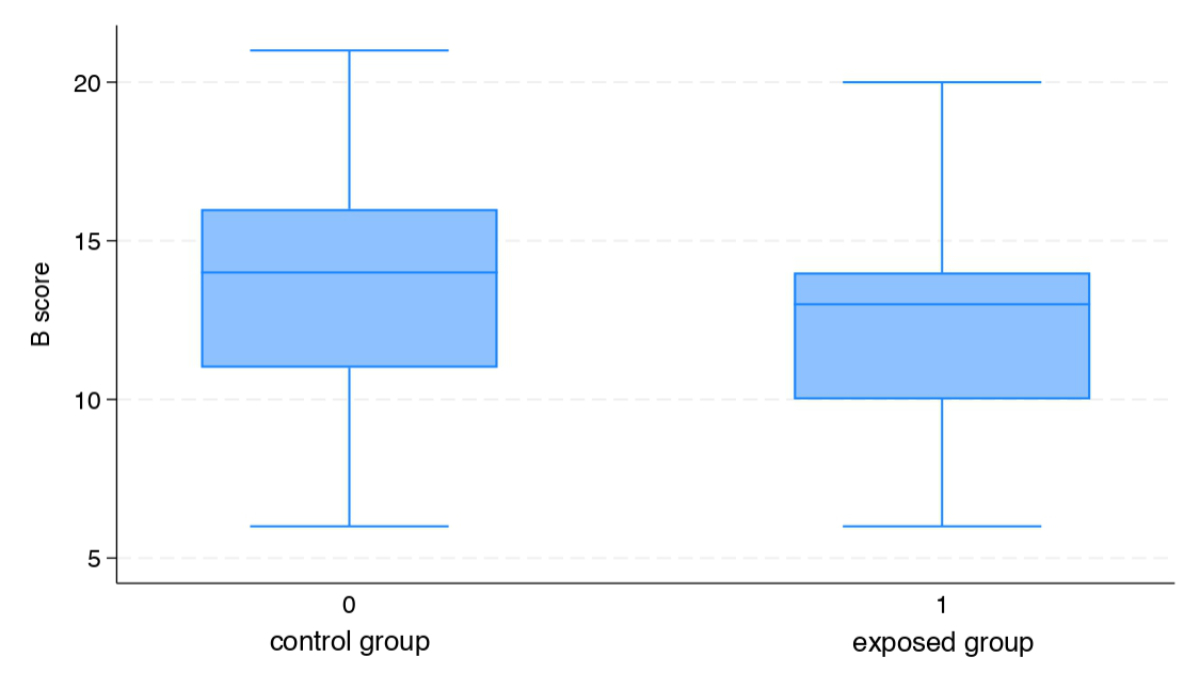

The average B score was 12.6 (SD: ±3.3) and 13.4 (SD: ±3.4) points out of 22 in the exposed and control group, respectively, and no significant difference was reported when comparing the two groups (p = 0.25) (figure 3).

Figure 3Average B score.

No difference was reported between groups regarding the proportion of low scores (crude OR: 1.22, CI 95%: 0.51–2.93). In the multivariate model, results were similar with an adjusted OR of 0.98 (95% CI: 0.38–2.53), after adjustment with the unbalanced cofactors, defined as a standardised difference of more than 10% between groups (participants’ age, sexual orientation, consultation habits and level or field of education).

Termination of education after compulsory school was the only risk factor associated with obtaining a lower score, defined as a score below the 25th percentile (OR: 4, 95% CI: 1.4–11.5; p = 0.01).

Most participants expressed satisfaction and interest in the intervention. The major themes from the thematic analysis are detailed below.

Participants considered that awareness of Chlamydia trachomatis is critical to reduce risky sexual behaviour. According to them, Chlamydia trachomatis is regretfully not treated as a societal subject worthy of interest. Indeed, many had never heard about it outside the context of a medical consultation or a private conversation. Some felt that the dialogue is getting easier, particularly through social networks, allowing opportunities to slowly lift a taboo that perpetuates the impression that the disease is rare. Overall, the participants pleaded for less guilt-laden communication and more prevention.

Participants agreed on the importance of high-quality school-based sex education to raise awareness of sexually transmitted infections. However, few had clear memories of the content of these courses, which were generally described as insufficient. The most frequent suggestion for improvement was to continue school sex education beyond compulsory schooling, in the belief that at the age of first sexual intercourse (16 years in the canton of Vaud [2]), young people would feel more concerned and would retain more information. The participants felt that an increase in the number of hours provided in addition to deepening of the topics covered were necessary for school sex education to fulfil its cardinal preventive role.

No difference in Chlamydia trachomatis infection knowledge was found between the video-exposed group and the control group when analysing questions whose answers were contained in the video. Similarly, no difference was found for questions whose answers were not contained in the intervention video. This suggests that most of the information in the video had already been acquired by the participants, who therefore did not benefit from viewing it. This remains a hypothesis due to the absence of a comparator pre-exposure test.

Excellent knowledge was observed for questions about the transmission of Chlamydia trachomatis through unprotected vaginal sex, the use of condoms as an effective means of protection and the need for testing after unprotected sex with a person of unknown or positive Chlamydia trachomatis infection status. These specific points are valid for other sexually transmitted infections and are likely strongly addressed during sex education as well as in national prevention campaigns targeting HIV. Thus, this finding could be linked to our selection criteria. Indeed, the inclusion criterion “Understands French” excludes non-native speakers, some of whom come from countries with various sexual health politics. Most participants have benefited from a systematic school sex education programme which has been led in the Vaud canton, a pioneer in the French-speaking region, for over 50 years. The rate of participants who has benefited from school sex education is rarely mentioned in other studies concerning young people’s Chlamydia trachomatis awareness. Their results mostly reveal poor knowledge and probably led us to underestimate our high-rate school sex education population’s knowledge. It should also be noted that a third of the participants reported having already been personally infected by Chlamydia trachomatis or having been made aware of it by the infection of a close relative. There is no comparison in the general population for this figure, which suggests a strong level of prior awareness among the participants. Thus, the population is selected and not representative of all women seeking emergency gynaecological care at Lausanne University Hospital.

These results can be generalised to French-speaking young women with previous school sex education visiting an urban gynaecology emergency clinic. The knowledge gaps between this population and the populations visiting a private practice or living in non-urban areas remain unknown.

The lack of awareness regarding the asymptomatic nature of Chlamydia trachomatis and the disease’s possible complications is concerning. Prevention efforts are still needed in these key areas. Patients with less than compulsory schooling should be given special attention in discussions about Chlamydia trachomatis. However, age was surprisingly not found to be associated with a higher risk of poor knowledge. By recency bias, it is possible that the temporal proximity of school sex education among the younger participants compensates for their fewer years of study and medical consultation compared to their elders.

Jaworski et al. and Goldsberry et al. showed significant improvement in knowledge of sexually transmitted infections among college students after a one-session intervention on the topic of sexually transmitted infections and safe sex. In contrast to our study, their intervention consisted of a face-to-face educational session in which students were informed of the research aspect of the process. This intervention seems to have had a greater effect on participants’ knowledge than ours, while requiring the presence and dedication of a health professional and targeting a small chosen group of people. This type of intervention is similar to the school sex education conducted in our country. For these reasons, our results seem difficult to match.

The excellent participation rate and the thematic analysis show that the participants are open to discussions about sexually transmitted infections. However, echoing their own analysis of the taboo aspect of the subject, they believe that the intimacy of the topic coupled with the stress of a medical consultation could make the video unattractive. Nevertheless, they maintain that the discussion should take place in a variety of contexts and reach as many people as possible.

The passive learning intervention described in this study did not improve the participants’ knowledge about Chlamydia trachomatis. During the one-to-one interview, participants were keen to receive information about Chlamydia trachomatis but the quantitative results show that the short video in the waiting room had no impact on their knowledge. Future studies should focus on pre-assessed, randomised, one-to-one or small-group active interventions.

The study lacked a pre-intervention knowledge assessment, which would have allowed a more precise analysis of post-intervention knowledge. The control and intervention groups were not randomised, introducing potential bias in participant characteristics. Regarding potential confounders, this study only included previous school sex education and training in the medical field but no other potential previous exposure to educational material. The questionnaire used in the interview was not validated thus its ability to determine accurate Chlamydia trachomatis knowledge should be considered uncertain. Information about income, occupation and region of residence were not collected. Given the inclusion criteria and participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, the conclusion should be considered valid only for French-speaking young women with previous school sex education visiting an urban gynaecology emergency clinic.

The data that support the findings of this study (population characteristics, interview responses) is available in anonymised form from the first author, SP, upon reasonable request.

We wish to thank the patients who participated in this study and Dr Antoine Garnier-Crussard for his help with statistical work.

Author contributions: SP was the main investigator and wrote the study protocol and the ethics committee submission, conducted the interviews with participants, carried out the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. GF participated in the management of the database, the statistical analysis and the proofreading of the manuscript. KL participated in database creation and statistical analysis. PM participated in the conception of the study and reviewed the final version of the manuscript. MJG took part in the conception of the study and reviewed the manuscript at every stage.

The Gynaecology service of Lausanne University Hospital contributed CHF 500 for video formatting.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript was disclosed.

1. Global progress report on HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections, 2021 n.d. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240027077

2. Jacot-Guillarmod M, Pasquier J, Greub G, Bongiovanni M, Achtari C, Sahli R. Impact of HPV vaccination with Gardasil® in Switzerland. BMC Infect Dis. 2017 Dec;17(1):790.

3. Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, Johnston CM, Muzny CA, Park I, et al. Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021 Jul;70(4):1–187.

4. Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Korenromp E, Low N, Unemo M, Abu-Raddad LJ, et al. Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis: global prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bull World Health Organ. 2019 Aug;97(8):548–562P.

5. Torrone E, Papp J, Weinstock H; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection among persons aged 14-39 years—united States, 2007-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014 Sep;63(38):834–8.

6. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Guidance on chlamydia control in Europe, 2015. LU. Publications Office; 2016.

7. Dielissen PW, Teunissen DA, Lagro-Janssen AL. Chlamydia prevalence in the general population: is there a sex difference? a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2013 Nov;13(1):534.

8. Chlamydia infection - Annual Epidemiological Report for 2018. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control 2020. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/chlamydia-infection-annual-epidemiological-report-2018

9. Lanjouw E, Ouburg S, de Vries HJ, Stary A, Radcliffe K, Unemo M. 2015 European guideline on the management of Chlamydia trachomatis infections. Int J STD AIDS. 2016 Apr;27(5):333–48.

10. Price MJ, Ades AE, Soldan K, Welton NJ, Macleod J, Simms I, et al. The natural history of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women: a multi-parameter evidence synthesis. Health Technol Assess. 2016 Mar;20(22):1–250.

11. Tang W, Mao J, Li KT, Walker JS, Chou R, Fu R, et al. Pregnancy and fertility-related adverse outcomes associated with Chlamydia trachomatis infection: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2020 Aug;96(5):322–9.

12. He W, Jin Y, Zhu H, Zheng Y, Qian J. Effect of Chlamydia trachomatis on adverse pregnancy outcomes: a meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020 Sep;302(3):553–67.

13. Witkin SS, Minis E, Athanasiou A, Leizer J, Linhares IM. Chlamydia trachomatis: the Persistent Pathogen. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2017 Oct;24(10):e00203–17.

14. Haggerty CL, Gottlieb SL, Taylor BD, Low N, Xu F, Ness RB. Risk of sequelae after Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection in women. J Infect Dis. 2010 Jun;201(S2 Suppl 2):S134–55.

15. Baud D, Regan L, Greub G. Emerging role of Chlamydia and Chlamydia-like organisms in adverse pregnancy outcomes. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008 Feb;21(1):70–6.

16. van Bergen JE, Hoenderboom BM, David S, Deug F, Heijne JC, van Aar F, et al. Where to go to in chlamydia control? From infection control towards infectious disease control. Sex Transm Infect. 2021 Nov;97(7):501–6.

17. Low N. Screening programmes for chlamydial infection: when will we ever learn? BMJ. 2007 Apr;334(7596):725–8.

18. Sagor RS, Golding J, Giorgio MM, Blake DR. Power of Knowledge: Effect of Two Educational Interventions on Readiness for Chlamydia Screening. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016 Jul;55(8):717–23.

19. Keizur EM, Bristow CC, Baik Y, Klausner JD. Knowledge and testing preferences for Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis infections among female undergraduate students. J Am Coll Health. 2020 Oct;68(7):754–61.

20. Greaves A, Lonsdale S, Whinney S, Hood E, Mossop H, Olowokure B. University undergraduates’ knowledge of chlamydia screening services and chlamydia infection following the introduction of a National Chlamydia Screening Programme. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2009 Feb;14(1):61–8.

21. Samkange-Zeeb FN, Spallek L, Zeeb H. Awareness and knowledge of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) among school-going adolescents in Europe: a systematic review of published literature. BMC Public Health. 2011 Sep;11(1):727.

22. Grouzmann E, Mathevet P, Jacot-Guillarmod M. L’éradication de l’infection à Chlamydia trachomatis : un objectif quotidien [Chlamydia trachomatis infection’s eradication : a daily goal]. Rev Med Suisse. 2019 Oct;15(668):1926–31.

23. Visalli G, Cosenza B, Mazzù F, Bertuccio MP, Spataro P, Pellicanò GF, et al. Knowledge of sexually transmitted infections and risky behaviours: a survey among high school and university students. J Prev Med Hyg. 2019 Jun;60(2):E84–92.

24. Jaworski BC, Carey MP. Effects of a brief, theory-based STD-prevention program for female college students. J Adolesc Health. 2001 Dec;29(6):417–25. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00271-3

25. Goldsberry J, Moore L, MacMillan D, Butler S. Assessing the effects of a sexually transmitted disease educational intervention on fraternity and sorority members’ knowledge and attitudes toward safe sex behaviors. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2016 Apr;28(4):188–95.

26. "La Chlamydia, c’est quoi? " : l’épisode 2 de “DépISTés.” 2017. [Internet]: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eBaUstjmvso

27. Kiger ME, Varpio L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med Teach. 2020 Aug;42(8):846–54.

28. Braun V, Clarke V. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological. Thematic analysis. APA handbook of research methods in psychology. Volume 2. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2012. pp. 57–71.

29. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. New York: Wiley; 2000. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/0471722146

30. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted infections surveillance, 2023. Report. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/sti-statistics/annual/index.html

31. Herzog SA, Heijne JC, Althaus CL, Low N. Describing the progression from Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae to pelvic inflammatory disease: systematic review of mathematical modeling studies. Sex Transm Dis. 2012 Aug;39(8):628–37.

32. Warner L, Klausner JD, Rietmeijer CA, Malotte CK, O’Donnell L, Margolis AD, et al.; Safe in the City Study Group. Effect of a brief video intervention on incident infection among patients attending sexually transmitted disease clinics. PLoS Med. 2008 Jun;5(6):e135.