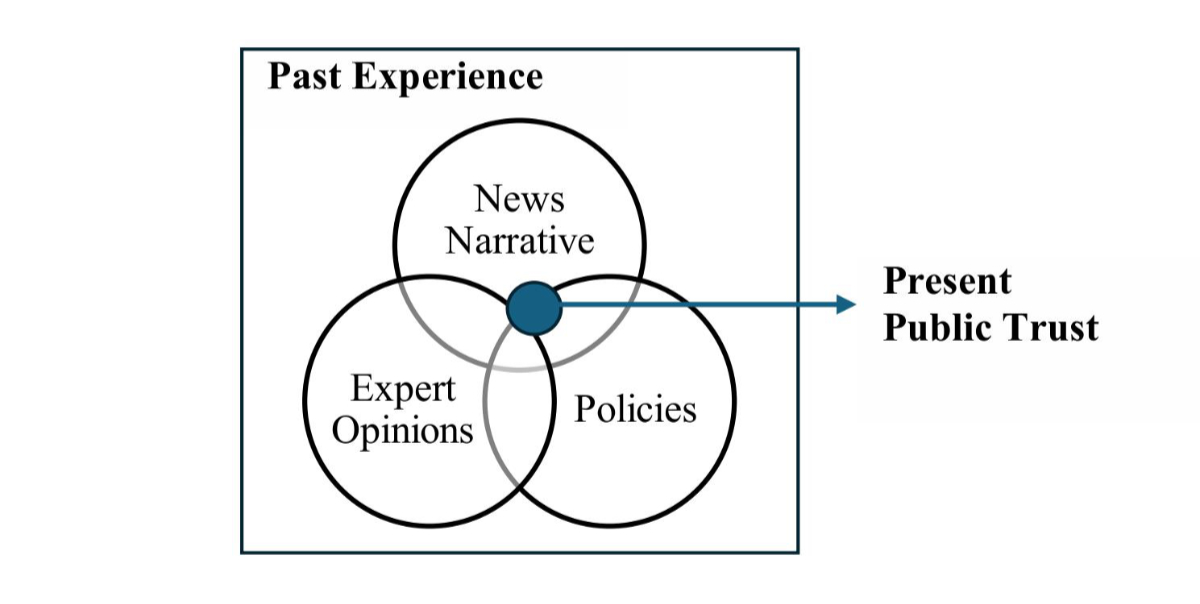

Figure 1Three dimensions shaping past public experience, hence present public trust.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4277

Public trust is essential for the successful implementation of health data sharing initiatives, such as the proposal for the establishment of a Swiss Data Room (SDR) for health-related research in Switzerland and the European Health Data Space (EHDS) across the European Union, as it is closely tied to public participation and healthcare system support [1–3]. Low levels of trust can result in individuals withholding consent to share their data, and professionals opposing these initiatives [1, 4]. Without sufficient levels of public trust, political decision-makers are unable to effectively drive the policy process forward as trust is integral to governmental legitimacy, potentially leading to policy failure [5, 6]. Trust can be defined as “a bet about the future contingent actions of others” [7], and when applied to health data sharing on a system-wide level, public trust involves the expectation that institutions, organisations or individuals responsible for collecting, storing, sharing and working with health data will act with integrity, reliability, competence and in the public’s best interest [1].

The need for public trust for digital transformation and health data sharing initiatives is highlighted by recent experiences of low public trust in Switzerland. Owing to its direct democracy system, low levels of public trust in political initiatives might lead to a call for a citizens’ referendum, as seen in the rejection of the Electronic Identification Services (e-ID) Act in March 2021, which aimed at establishing a state-recognised and secure electronic proof of identification [8]. Similarly, alongside the shortcomings of political and health system actors, low public trust has contributed to the limited adoption of the Electronic Patient Dossier (EPD), introduced in 2015, with a nationwide adoption rate of 0.22% as of April 2023 [4, 9, 10]. The potentially severe effects of low public trust on the success of current and future health data sharing initiatives are acknowledged by Swiss health policymakers. In the Swiss Health 2030 strategy, the “need to build public trust” in the use of health data is identified as a priority to achieve the first objective of the initiative [11]. Similarly, in package four of the Swiss government’s DigiSanté programme for 2025–2034, the development of a Swiss Data Room for health-related research is reported to be carried out with a strong emphasis on trustworthiness [12].

To ensure public acceptance of the Swiss Data Room and the achievement of its goals in the near future, it is crucial to understand the public’s past experiences with health data sharing activities that frame current public trust. Public trust develops in the public sphere through open public discourse on present perceptions of system trustworthiness and future expectations of potential benefits, with familiarity and shared past experiences considered significant determinants of present public trust [1]. The close relationship between past experiences and trust is described by a trust culture arising from “the collective and shared experiences of societal members over time”, defining trust culture as “a product of history” [7]. Conferring trust requires consideration of all previous experiences, as trust can only be placed in a familiar world with a reliable background [13].

We identify three dimensions equally influencing collective past public experiences and, consequently, public trust in health data sharing at present: news narratives, expert opinions and policies (figure 1). News narratives shape public trust through topic framing, reporting tone and story selection [14, 15]; expert opinions provide insights into complex issues, contributing to shaping public trust, although conflicting expert views may undermine it [16, 17]; policies promote among the public a sense of security, certainty and predictability, alleviating concerns and enhancing trust in the system [18–20]. Individual first-hand experiences with national and international data sharing initiatives also contribute to shaping public trust. However, these data sharing initiatives have not yet been fully implemented in Switzerland. For example, personal experience with the EPD is limited to fewer than 20,000 individuals nationwide [9]. Therefore, the factor “personal experiences” is not considered in the current analysis, which argues that the Swiss collective experience is primarily framed by the three dimensions outlined in figure 1. Once health data sharing initiatives are fully operational, individual experiences should be included as a fourth dimension influencing collective experience and public trust in health data sharing.

Figure 1Three dimensions shaping past public experience, hence present public trust.

Building on the proposed interplay between policies, news narratives and expert opinions in shaping past collective experiences and thus public trust at present, we aim to analyse these three dimensions to identify (1) the policy timeline around health data sharing in Switzerland; (2) opinion-shaping and (3) negative events that have influenced public experience and trust in health data sharing over the past 31 years; (4) implementation obstacles and (5) lessons learned during this period. This study constitutes one work stream within an overarching research project entitled “Public Trust in a Swiss Health Data Space” [21] that aims to explore what a trustworthy Swiss health data space might look like from the public’s perspective. The present study contributes to this goal by tracing the evolution of the discourse surrounding health data sharing in Switzerland, while a complementary study involves interviews with members of the public to capture their understanding of trustworthiness, incorporating sociocultural dimensions of trust. The ultimate objective of the present study is to inform DigiSanté’s Swiss Data Room project specifically, as well as Swiss and European policymakers in the design and implementation of future health data sharing initiatives more broadly.

We designed a multi-method study to capture the dimensions of expert opinions, policy and news narratives on health data sharing in Switzerland from 1992 to 2023. No formal study protocol was developed or registered for this research. Our approach, grounded in phenomenology (A.I) and content analysis (A.II, B, C) [22], included three data streams:

(A.I) a thematic analysis of online interviews with key stakeholders and

(A.II) a scoping review of expert opinion papers to capture expert perspectives;

(B) a policy analysis of government policies to understand the political trajectory and trace the policy timeline;

(C) a news search and analysis across Swiss newspapers to trace the evolution of media narratives.

Following an assessment of the quality of data provided by the three data streams, we used the data collected from the interviews as the primary data source for the study, with the other sources providing additional context to these findings. By integrating insights from the interview data with the policy analysis and the scoping review of expert opinion papers, we identified (1) the policy timeline within the current landscape of health data sharing in Switzerland. By combining data from the interviews, news articles and expert opinion papers, we were able to identify (2) opinion-shaping events, (3) negative events, (4) implementation obstacles and (5) key lessons for the future implementation of health data sharing initiatives in Switzerland. We conducted the data collection and analysis from October 2023 to May 2024, using German, French, Italian and English as appropriate, with all languages fluently spoken by research team members. German (61.8% of the population, 2022), French (22.8% of the population, 2022), Italian (7.8% of the population, 2022), and Romansh (0.5% of the population, 2022) are the four official languages of Switzerland [23].

In February and March 2024, FZ conducted semi-structured 30-minute online interviews in English with senior experts in digital health from Switzerland. These experts were purposely sampled from academia, the pharmaceutical industry, the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH), the Federal Statistical Office, the Swiss Personalised Health Network, the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, the Swiss Medical Association, politics and journalism. All potential participants were invited via an email (sent out in February 2024) providing a brief introduction to the research team and the study aim. Before the interview process started, FZ pilot-tested the interview set-up and questions.

In line with Pope and Mays’ guide on designing a topic guide in qualitative research [24], FZ and FG developed five open-ended interview questions to foster discussion and exploration of the topic by interviewees. Questions were formulated based on FZ, FG and PD’s prior research, and were aligned with the study’s objectives (appendix 1). The online interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed using the online software Zoom (version 5.17.11). Transcripts were then uploaded to MaxQDA24, a software for qualitative research, manually reviewed by FZ to remove identifying information (e.g. names, institutions and cities) and to check transcription accuracy. FZ coded the transcripts using a reflexive thematic approach to identify emerging themes [25]. To ensure the quality of the analysis, FG and PD reviewed the codes and reached agreement with FZ on the identified emerging themes. Additional details on the data collection and analysis processes are available in appendix 2, which aligns with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist [26].

The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and obtained clarification of responsibility from the ethics committee of the Canton of Zurich on 8 January 2024 (BASEC Nr: 2023-01518). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

We conducted a scoping review of editorials and viewpoints to trace the evolution of expert opinions on health data sharing in Switzerland from 1998 to 2023. Our approach was guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s [27] 6-step methodological framework for conducting scoping studies (appendix 3). In collaboration with a specialised librarian from the University of Zurich, we developed a search strategy for PubMed, Scopus, Embase and Cochrane (appendix 4). We included Swiss Health Web, Swiss Medical Forum and Swiss Medical Weekly due to the study’s geographical focus. Keyword searches were conducted with “Gesundheitsdaten” (German for “health data”), as well as “Swisstransplant”, “Meineimpfungen” (German for “myvaccination”) and “Patientendossier” (German for “patient dossier”), which emerged from interviews as key events affecting public perception of health data sharing in Switzerland (appendix 4). Searches were conducted in November 2023 and in January 2024, covering publications from 1998 to 2023. We included articles in English, French, German and Italian that focused on Switzerland and health data sharing initiatives. Editorials were included from PubMed, Scopus, Embase and Cochrane, while a broader range of article types – including editorials, commentaries, position papers, themed issues and updates – were included from the Swiss journals. Publications were pasted into an Excel file in their original language, along with their English translations (produced using ChatGPT version 3.5). FZ and FG used an inductive approach to code publications, to identify their topic, date and tone using colour-coded indicators. Expert opinion papers coded in red predominantly conveyed a negative message about the topic, reflecting a potential negative influence on public opinion. Publications coded in yellow were considered as neutral, reflected by their reporting of facts or pros and cons in a balanced approach. Publications coded in green reflected those with a more positive tone on the impact of data sharing initiatives on society. Colour coding was based on the original language text to capture nuances of tone in each language. FZ colour-coded Italian and French articles, while FG colour-coded the ones in German. To mitigate the risk of interpretation bias and to enhance reliability, FZ and FG subsequently independently coded the English translations of the German, Italian and French articles, respectively, then cross-checked the codes against the initially assigned codes. In cases of discrepancy in assigned codes, PD, who is fluent in all four languages, was consulted in order to reach a consensus.

The policy analysis focused on documents tracing the political development of the health data sharing discourse in Switzerland, up to 2023. The first search started with documents in 1998, due to the publication of the Federal Council’s Information Society Strategy on 18 February, which marked the first acknowledgement of the potential of digital data for Switzerland and the need for specific safeguards. Among the identified policy documents, FZ and FG selected the relevant documents pertaining to health data sharing and digitisation of the health system. Following compilation of interview findings, we extended the research timeframe by conducting a second search for documents dating back to 1992. We searched for policy documents on the Swiss Government and Parliament websites (https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home and https://www.parlament.ch). These searches involved the following key terms: “data”, “health data” in Italian (“dati”, “dati sanitari”) and German (“Daten”, “Gesundheitsdaten”); as well as identifying relevant cross-references within the identified policies. We identified broad search terms, and we included different types of documents (acts, strategies, motions, referenda, mandates, press releases, interpellations and postulates) to gain a comprehensive overview of the relevant political developments on health data sharing. Once the list of policy documents deemed influential in the Swiss health data sharing discourse by FZ and FG was compiled in chronological order, the Policy Streams Approach [28] was applied to identify windows of opportunities for health data sharing policies.

We first conducted news searches on the digital news archives “e-newspaperarchives.ch” and “swissdox.ch” using key term searches with the terms “health data” and “electronic health record” in German (“Gesundheitsdaten”, “Patientendossier”). Due to limited results, we opted to search the digital archives of seven leading newspapers in Switzerland across the three language regions: Italian (“Corriere del Ticino”, “La Regione”), French (“Le Temps”, “Tribune de Genève”) and German (“Der Bund”, “Tages-Anzeiger”, “Neue Zürcher Zeitung”). The editorial teams of each newspaper were contacted for advice on the best search methods using their digital search engines. In the case of Neue Zürcher Zeitung, despite subscribing to different plans and contacting the support team, we were unable to access the news articles in a researchable format from their digital archives, resulting in exclusion of this publication from the study. Additionally, we conducted news searches on Medinside and Inside IT, two Swiss digital news platforms that cover healthcare and technology topics, respectively. Broad key search terms in German, Italian and French included “health data” and “electronic health record” from January 1998 to December 2023, as well as “Swisstransplant” and “Meineimpfungen” from January 2020 to December 2023 to capture news related to the two main scandals during that period that emerged from the interviews (appendix 4). The news search was conducted by FZ. Articles were pasted into an Excel file in their original language, alongside their English translations (produced using ChatGPT version 3.5). The accuracy of the translations was verified by the research team. Articles were then coded based on topic, date and tone using colour-coded indicators (see section “Scoping Review of Expert Opinion Papers [A.II]”)

We identified 86 policy documents (appendix 5), 27 expert opinion publications, 528 news articles (appendix 4), and interviewed 11 key stakeholders (appendix 2). From these sources and guided by interview data, we selected:

We identified 44 relevant policy documents and events (table 1) from a total of 86 (appendix 5). These documents represent significant political and legal milestones that have framed the discourse on health data sharing in Switzerland, thereby setting the timeline for the present study. We identified a first policy wave beginning in the late 1990s, coinciding with the initial phase of digital transformation, which primarily focused on establishing the legal foundation for the use of health data for primary purposes. A second policy wave, catalysed by the COVID-19 pandemic, centred on creating the legal framework for the secondary use of health data.

Table 1List of key Swiss policy documents/events shaping the health data sharing political discourse.

| Date | Documents/Events |

| First policy wave – Legal foundation for the primary use of health data | |

| 1992 | SR 235.1 – Federal Act on Data Protection (FADP) |

| SR 431.01 – Federal Statistics Act (FStatA) | |

| 1994 | SR 832.10 – Federal Health Insurance Act (KVG) |

| 1998 | Federal Council’s Information Society Strategy in Switzerland |

| 2001 | Patient Dossier Initiative |

| 2004 | Swiss eHealth Situation Analysis |

| 04.3243 Noser Motion – E-Health. Use of electronic means in healthcare | |

| 2006 | Strategy of the Federal Council for an Information Society in Switzerland (Updated from 1998) |

| 2007 | AS 2007 479 – Ordinance on the Insurance Card for Compulsory Health Insurance (VVK) |

| eHealth Swiss Strategy (2007–2015) | |

| Founding of “eHealth Swiss” | |

| 2010 | SR 818.101 Epidemics Act – entered into force in 2016 |

| 10.3327 Humbel Postulate – Implementation of the e-Health Strategy | |

| Electronic health record: mandate for the development of legal bases | |

| 2011 | SR 810.30 – Human Research Act (HRA) – entered into force in 2014 |

| 2012 | Federal Strategy for Switzerland’s Digital Future |

| 2015 | SR 816.1 – Federal Act on the Electronic Patient Record (EPRA) – entered into force in 2017 |

| 15.4225 Humbel postulate – Better use of health data for high-quality and efficient healthcare | |

| 2016 | SR 818.33 – Cancer Registration Act (CRA) – entered into force in 2018 |

| 2017 | Establishment of the Swiss Personalised Health Network (SPHN) |

| 2018 | eHealth Swiss 2.0 (2018–2024) |

| Establishment of the CARA Association | |

| 18.4328 Wehrli Postulate – Electronic patient record. What else can be done to ensure that it is fully used? | |

| 2019 | Health Policy Strategy 2020–2030 (Health 2030) |

| Second policy wave – Legal foundation for the secondary use of health data | |

| 2020 | Digital Switzerland Strategy (updated from 2018) |

| 20.3243 FDP_SR Motion: COVID-19. Accelerating the Digitalisation in Healthcare | |

| 2021 | Electronic Identity Act (e-ID Act) – Referendum |

| 21.3957 Ettlin Motion – Digital transformation in healthcare. Finally catching up! | |

| 21.4373 Silberschmidt Motion – Introduction of a unique patient identifier | |

| 2022 | Report from the FOPH on improving data management in the healthcare sector |

| Report from the Federal Council following up on 15.4225 Humbel Postulate | |

| Transplantation Act – Referendum | |

| 22.3890 WBK_SR Motion: Framework law for the secondary use of health data | |

| 22.4022 FDP_NR Postulate: Exploiting the potential of digitalisation and data management in the healthcare sector. Switzerland needs an overarching digitalisation strategy | |

| Creation of trustworthy data rooms based on digital self-determination | |

| Swiss Digital Strategy 2023 | |

| 2023 | DigiSanté 2024–2034 – Programme to promote digital transformation in the health system – Commitment credit |

| Code of Conduct for managing trustworthy data spaces based on digital self-determination | |

| SR 235.1 – (New) Federal Act on Data Protection (nFADP) | |

| 2024 | DigiSanté 2024–2034 – Federal Decree on the commitment credit for a programme to promote digital transformation in the healthcare sector for the years 2025–2034 |

| Ongoing | Revision of the EPRA |

| Revision of the Epidemics Act to better manage future public health crises | |

| Revision of the HRA | |

| Implementation of 22.3890 WBK_SR Motion: Framework law for the secondary use of data | |

From the interviews, it emerged that two of the earliest policies instrumental in shaping the political discourse on health data sharing in Switzerland, both published in 1992, were the Federal Act on Data Protection (SR 431.01), which categorised health data as “sensitive personal data” under Article 5 and introduced the concept of explicit consent for the processing of personal data, and the Federal Statistics Act (SR 431.01), which regulated for the first time the linkage of personal data between different databases. In 1994, the Federal Health Insurance Act referred for the first time to the secondary use of data with the involvement of multiple actors. In 1998, the Information Society Strategy became the first policy document to emphasise the potential of digital data for Switzerland and the necessity of establishing specific safeguards. In 2001, five Swiss university hospitals (Basel, Bern, Geneva, Lausanne, Zurich) launched the “Patient Dossier 2003” initiative aimed at enhancing computer utilisation in data management and standardising the dissemination of patient records. This represents the first attempt to systematically disseminate the use of digital patient files [29]. The need for a legal framework for primary health data use emerged in 2004 with the Noser motion 04.3243, which called for a draft law on eHealth to provide Swiss citizens with access to electronic health records. Following the European eHealth Action Plan, in 2004 the Swiss government commissioned a Swiss eHealth situation analysis to assess the implementation status of eHealth in Switzerland, which was described as “heterogeneous”. Based on this analysis, the eHealth Swiss strategy was published in 2007 with the aim of improving the efficiency, quality and security of electronic services in the health sector. Moreover, this strategy set a nationwide objective to gradually implement electronic medical records. In 2010, the Humbel Postulate 10.3327 urged the Federal Council to present the necessary legal basis to support the implementation of the eHealth strategy, leading the Federal Council to instruct the Federal Department of Home Affairs (EDI) to establish the legal framework for the implementation of electronic patient records by September 2011. These policy developments culminated in the publication of the SR 816.1 – Federal Act on Electronic Patient Records (EPRA) in 2015, which provided a legal framework for data sharing for primary use in Switzerland.

While the Human Research Act of 2011 (SR 810.30) introduced general informed consents and established a foundation for health data sharing for research purposes in Switzerland, the COVID-19 pandemic catalysed policymakers’ recognition of the need for a comprehensive strategy in healthcare digitalisation, particularly regarding the use of data for research purposes. This was highlighted in motion 20.3243 FDP_SR, which directed the Federal Council to take necessary measures, in collaboration with relevant stakeholders, to accelerate the digitalisation of the Swiss healthcare system. In January 2022, the FOPH released a report on improving data management in the healthcare sector, drawing on lessons from the pandemic and outlining seven guiding principles for future data management. Subsequently, in May 2022, the Federal Council responded to the 2015 Humbel postulate 15.4225 which emphasised the need for better reuse of health data, by issuing a report that directed the EDI to define the processes and structures of the data system and make the necessary legal adjustments. These developments led to several political initiatives in 2022, including the adoption of motion 22.3890 WBK_SR, which called for a framework law on the secondary use of health data, as well as postulate 22.4022 FDP_NR, which advocated for a comprehensive digitalisation strategy in healthcare. In May 2022, the Federal Council tasked the EDI with developing a programme to enhance the use of digitalisation and data management, integrating existing mandates including the 21.3957 Ettlin motion, the 21.4373 Silberschmidt motion as well as the 15.4225 Humbel postulate. In November 2023, the Federal Council submitted a request for commitment credit to the Federal Assembly to finance the DigiSanté programme, aimed at promoting digital transformation in the healthcare system. This culminated in the Federal Decree on the commitment credit for DigiSanté, covering the years 2025–2034, published on 13 June 2024, thereby formally initiating the programme, which includes in package 4 (“Secondary use for planning, strategic management, and research”) the establishment of the necessary conditions for secondary data use within the Swiss health data space.

The complete list of described policy documents and their references can be found in appendix 5.

From the interviews, four events emerged that contributed to framing the sociopolitical discourse surrounding health data sharing in Switzerland (table 2). Supportive quotes from interviewees can be found in appendix 6.

Table 2Events contributing to the framing of the sociopolitical discourse on health data sharing – chronological order.

| Opinion-shaping events positively influencing the sociopolitical discourse on health data sharing – Interview data |

| 1. Early 2000s – Digitisation of private life |

| 2. 2020 – COVID-19 pandemic |

| 3. Before 2021 – “Myvaccination” solution |

| 4. 2023 – DigiSanté programme |

Interviewees emphasised that the digitisation of private life in the early 2000s, including increased access to internet and mobile devices, has contributed to the data sharing discourse by raising public awareness about the ubiquitous data flows.

Interviewees noted that the pandemic raised public awareness of the critical role of health data and served as a catalyst for policymakers, highlighting the need for a comprehensive health data governance strategy. Additionally, the SwissCovid digital contact tracing app was reported by interviewees as a digital health success in Switzerland, as it was developed quickly and with high standards.

Interviewees reported that, prior to the 2021 data leak [30], “meineimpfungen/myvaccination” was an accepted digital solution that positively contributed to the discourse on health data sharing. The data leak shifted the narrative in a negative direction.

The establishment and initialisation of the DigiSanté programme by the FOPH and the Federal Statistical Office in 2023 was cited by interviewees as a positive development for the digital transformation of the Swiss healthcare sector, demonstrating that governmental bodies are fulfilling their commitments to a solid national digital health strategy.

We identified three main negative events (table 3). Quotes from interviewees can be found in appendix 7.

Table 3Events negatively influencing the sociopolitical discourse on health data sharing – ordered from most to least frequently mentioned.

| Events negatively influencing the sociopolitical discourse on health data sharing – Interview data | |

| 1. Scandals | 2013: Edward Snowden leaked intelligence data from the US National Security Agency. |

| 2018: Cambridge Analytica’s unauthorised processing of personal data from Facebook. | |

| 2021: Data breach of “Myvaccination” platform exposed Swiss citizens’ vaccination records. Rejection of the Electronic Identification Services (e-ID) referendum. | |

| 2022: Data breach of the Swiss Organ Donation register. | |

| 2022: Online leak of medical files in Neuchâtel, Switzerland. | |

| 2. Slow implementation of the Swiss Electronic Patient Dossier initiative (2015–2024). | |

| 3. Switzerland’s reliance on paper-based systems revealed by COVID-19. | |

When investigating events that negatively impacted the sociopolitical discourse on health data sharing in Switzerland, interviewees mentioned (table 3) the 2013 Edward Snowden scandal, which was the biggest intelligence leak in the history of the USA’s National Security Agency (NSA) [31]; the revelation in 2018 of the unauthorised processing of personal data belonging to millions of Facebook users for political advertising by the British consulting firm Cambridge Analytica [32]; the investigation of Swiss platforms “My Vaccination/meineimpfungen” in 2021 [30] and “Organ Donation/Swisstransplant” in 2022 for data protection violations [33]; and the online leakage of medical files belonging to thousands of residents in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, in 2022 [34]. In particular, the 2013 Edward Snowden scandal, “My Vaccination” and “Organ Donation” were the most frequently reported negative events by interviewees. While it was acknowledged that other data leaks occurred over the years that negatively impacted public opinion on health data sharing, interviewees noted that these incidents did not significantly influence the broader public. Additionally, the e-ID referendum in 2021 was noted for sparking debates around government involvement in the governance of sensitive data. Stakeholders reported the outcome of this referendum with negative connotations since it revealed a lack of public trust in the state.

From the analysis of 55 news articles and expert opinion papers on “My Vaccination” and “Organ Donation” scandals covering the timeframe 2020–2023, it emerged that the tone of the articles was predominantly negative (67% and 57%, respectively, coded in red – appendix 8).

Interviewees reported that the negative narrative around the implementation of the EPD over the years has had a more significant impact on the overall public perception of health data sharing in the country compared to national and international scandals.

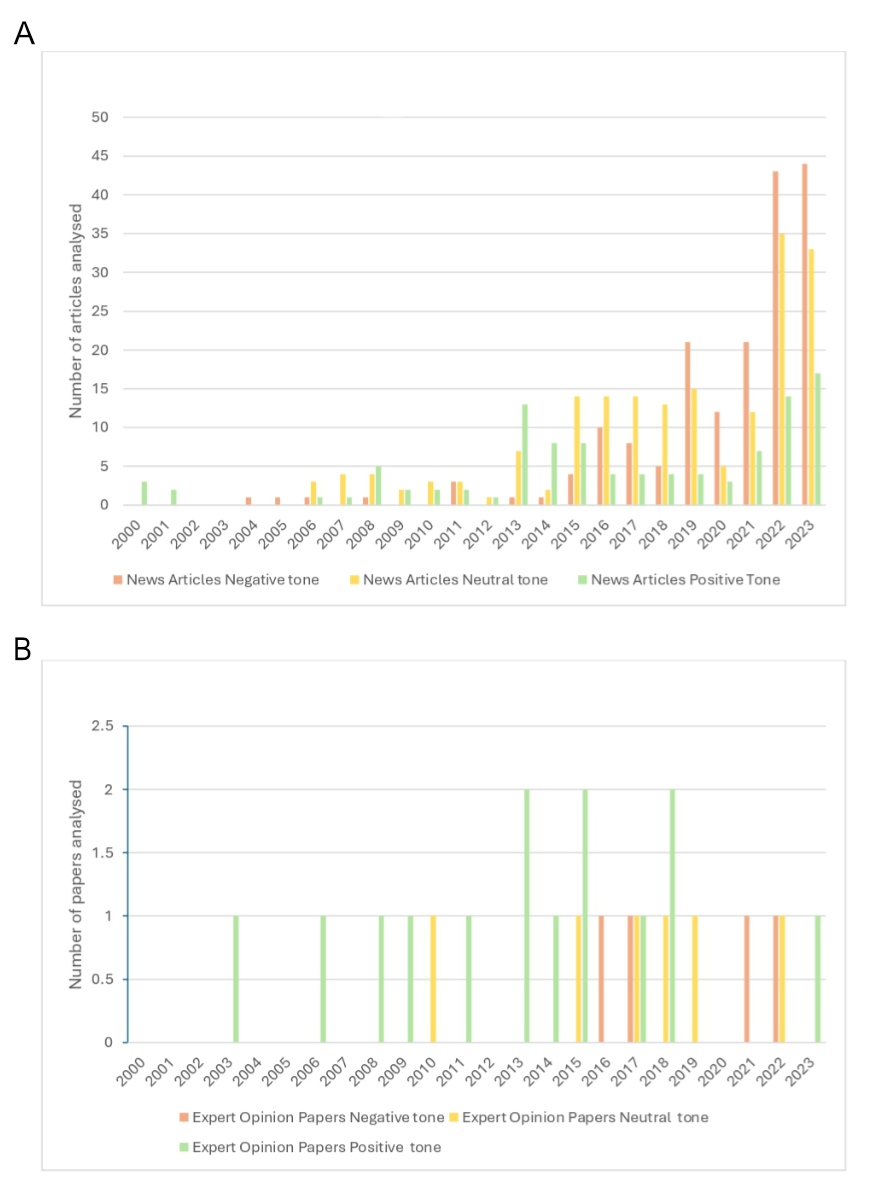

From the analysis of 476 news articles and expert opinion papers on health data sharing and the EPD (keywords: “health data”, “Patientendossier”) covering the timeframe 1998–2023, it emerged that the tone of expert opinion papers was mainly positive (66% coded in green), contrasting with news articles, which tended to adopt a negative to neutral tone (39% red, 38% yellow – appendix 8). Moreover, the tone of news articles gradually turned more negative after the publication (2015) and enforcement (2017) of the Federal Act on the Electronic Patient Dossier (EPRA) (figure 2). From this point onwards, articles began regularly reporting delays in implementation of the EPD, highlighting inefficiencies, raising security concerns, up to accusing the federal government and the cantons of lacking a “holistic vision” [35] and referring to the EPD initiative as “the small failure of a modern state” [36]. A similar trend is visible from the analysis of the tone of expert opinion papers, which underwent a negative shift in tone in the years between 2016 and 2021 (figure 2). In the early 2000s, expert opinion papers typically highlighted the positive impact of the computerised patient record on the improvement of “the quality of care and patient management” [37], with the Swiss Medical Association (FMH) describing the EPRA as “an opportunity” in 2015 [38]. From 2016, the tone of expert opinion papers shifted negatively. In 2016, an editorial from the FMH criticised the too-high regulatory density and requirements of the newly published EPRA [39]. This negative tone persisted in most expert opinion papers in the following years, becoming more neutral in 2018 and 2019. In 2022, the tone turned negative again, culminating in an article referring to the EPD as a “monster that will never work” [40], highlighting the need to not give any further power to the FOPH. The tone then became more neutral towards the end of 2022, as expert opinion papers mentioned the revision of the Federal Act on the Electronic Patient Dossier [41] and positive in 2023 with the launch of a national awareness campaign to accompany the introduction of the EPD [42].

Figure 2The graphs illustrate the tone of news articles (A) and expert opinion papers (B) – negative (red), neutral (yellow) and positive (green) – alongside the total number of articles analysed each year. Publications coded red predominantly conveyed negative messages, yellow reflected a neutral and balanced approach and green emphasised the positive societal impact of data-sharing initiatives.

The COVID-19 pandemic was reported as exposing the Swiss healthcare system’s heavy reliance on paper-based practices, underscoring the significant work needed to advance its digitalisation efforts.

The interview data revealed 15 obstacles to implementing health data sharing initiatives, particularly concerning the EPD. These challenges span the policy process, the public, healthcare professionals and technical issues (table 4). Quotes from interviewees can be found in appendix 9.

Table 4Obstacles that emerged from interviews – ordered from most to least frequently mentioned.

| Obstacles to the implementation of health data sharing initiatives – Interview data | ||

| Policy | Misalignment of stakeholder interests with power dynamics among actors. | |

| Cultural attitudes and individualistic approaches towards data sharing. | ||

| Pace disparity: policy processes lagging behind digitisation. | ||

| Challenges posed by federalism. | ||

| Voluntary participation in data sharing initiatives. | ||

| Limited public involvement in policymaking. | ||

| Absence of legal framework for secondary use of health data. | ||

| Insufficient funding for the implementation of the initiative. | ||

| Public | Lack of public awareness of the potential of their data and the benefits of the solution being implemented. | |

| Lack of public discourse on health data sharing for secondary purposes. | ||

| Resistance to change in a functioning healthcare system. | ||

| Data security and privacy concerns. | ||

| Non-user-friendly interface and complex registration process. | ||

| Healthcare professionals | Lack of support from physicians, negatively impacting patient adoption of the solution being implemented. | Physicians serving as trust anchors for patients, creating a sense of accountability in data handling. |

| Limited perceived benefits from the health data sharing solution being implemented. | ||

| Lack of direct financial incentives to support their digital transition. | ||

| Technical obstacles | Challenges with interoperability (unstructured/siloed data). | |

One of the main obstacles to the implementation of health data sharing initiatives in Switzerland is the lack of alignment of interests among different stakeholders on health data use, including researchers, healthcare professionals and politicians, resulting in power dynamics among various actors. Cultural attitudes towards data sharing emerged as a prominent obstacle, along with reluctance to share data for secondary use due to individualistic reasons such as wanting to keep the benefits for oneself and not recognising the broader benefits of data sharing. Interviewees reported a disparity in pace between technological advancement and policymaking processes, often resulting in delays in the regulation of crucial measures. Federalism emerged as an obstacle to implementing nationwide coordinated health data sharing initiatives in Switzerland, due to a lack of central coordination, resulting in the absence of common standards and a unified strategy. Voluntary participation in the EPD was identified as an obstacle to its implementation, along with limited public involvement in policymaking. Regulatory hurdles and lack of legal clarity on secondary data use slowed down the implementation process, compounded by limited funding resources.

A key obstacle for the implementation of health data sharing solutions is the lack of awareness among the public, healthcare professionals and politicians regarding the initiative and its benefits, with some of the interviewees questioning the current existence of a proper public discourse on health data sharing for secondary purposes. Moreover, interviewees pointed to an underlying cultural resistance to change, given the highly effective Swiss healthcare system. Privacy and security concerns were reported by stakeholders as obstacles, though deemed marginal, for the public to participate in data sharing initiatives as the public fears that their sensitive health data could be accessed by insurance companies, potentially prompting changes in their business practices. Additionally, the non-user-friendly interface of the EPD and the complex registration process were reported as implementation barriers.

The reluctance of healthcare stakeholders to support the EPD had a detrimental impact on public trust. When patients see that healthcare professionals are unwilling to use the EPD, they become suspicious and lose trust, believing that if medical professionals do not trust the system, neither should they. Three main reasons for healthcare professionals’ reluctance towards the EPD emerged from the interviews and expert opinion papers:

(a) Their role as trust anchors for patients, feeling responsible for the handling of health data and the maintenance of patient privacy. This concern has been central also in expert opinion papers since 2010, where trust and confidentiality were identified as “fundamental principles in medicine [...] not negotiable” [43] and as “the foundations of safe and effective patient treatment” [44]. References to Hippocrates and his principle of confidentiality have been cited since 2015, highlighting it as a cornerstone of trust between doctors and patients and, consequently, of the therapeutic relationship and treatment quality [45].

(b) Healthcare professionals perceived limited benefits from the EPD solution due to their poor involvement in its development and the policymaking process, likening it to a storage system for PDF documents. Expert opinion papers since 2017 have criticised the insufficient involvement of medical professionals in the health policy process, pointing out that the FOPH tries “to prevent specialist medical personnel from participating in the development of laws and their implementation”, with the direct consequence being that healthcare professionals have to work with solutions poorly suited to practical implementation [46]. This criticism persisted until 2021, with the FMH affirming that for the EPD to provide added value, “the improvements proposed by doctors – who are the first users of the EPD – must be heard and taken seriously” [47], and that eventually the involvement of health professionals in the policymaking process doesn’t have to be just an “alibi exercise” [47].

(c) The lack of financial support to facilitate healthcare professionals’ digital transition, with the FMH stating in an opinion paper that their tariff requests were disregarded, “missing the opportunity to create financial incentives for the EPD” [47].

Interoperability remains a significant obstacle to overcome for the implementation of health data sharing initiatives in Switzerland, primarily due to non-harmonised, unstructured or siloed data.

From the interviews, 19 key lessons for the future were identified for overcoming implementation barriers for data sharing initiatives, spanning policy, public, healthcare professionals and broader health data sharing solutions (table 5). Relevant quotes are in appendix 10.

Table 5Lessons for the future – ordered from most to least frequently mentioned.

| Key lessons for the future – Interview data | ||

| Policy | Align stakeholders’ interests. | |

| Establish a legal framework for secondary health data use. | ||

| Centralise the coordination of the initiative at federal level. | ||

| Increase funding available to promote the implementation of health data sharing solutions. | ||

| Separate bodies for data storage and use to avoid conflicts of interest. | ||

| Set political priorities after the system’s functionality has been successfully demonstrated. | ||

| Accelerate policymaking to match pace of technology development. | ||

| Public | Illustrate to the public the benefits of the health data sharing initiative being implemented. | |

| Improve public communication (use of ambassadors). | ||

| Involve the public in policymaking. | ||

| Healthcare professionals | Involve healthcare professionals from the start in developing the health data sharing solution. | |

| Explain benefits of the health data sharing solution to healthcare professionals. | ||

| Provide financial support to healthcare professionals. | ||

| Consider a patient-centric approach to data sharing. | ||

| Data sharing solutions | Data security and privacy | Acknowledge risks and enhance data protection measures. |

| Use an external third party for data oversight and ensure transparency on data access. | ||

| Store data in Switzerland. | ||

| Technical features | Align taxonomy of health data. | |

| Use patient identifiers to optimise the secondary use of health data. | ||

| Demand high-quality data from the source | ||

| Ensure the solution works, benefits all actors and is easy to use. | ||

| Establish trust with eID before adding health data – without imposition. | ||

| No one-size-fits-all solution due to diverse public composition. | ||

At the policy level, it is necessary to align stakeholders’ interests by increasing their involvement in the policy process and convening discussions to identify common solutions and advance the system. Interviewees also mentioned the need to establish a legal framework governing the secondary use of health data and the opportunity to consider the centralisation of the coordination of the initiative at the federal level, given the small size of Switzerland, to increase efficiency. Interviewees mentioned the need to increase funding for the initiative’s effective implementation, and the need to have separate bodies for data storage and use to avoid conflicts of interest. It was pointed out that politicians should set priorities and take the lead for the implementation of the initiative once technical officers have demonstrated the system’s functionality. Lastly, there emerged the need to streamline the policy process to adapt more swiftly to digital technological advancements.

Interviewees emphasised the importance of demonstrating the benefits of data sharing initiatives to the public with concrete examples and of investing in educational and communication campaigns to inform citizens about the initiative. Using ambassadors from cancer registries, given their high level of public trust, was suggested as a viable strategy to promote health data sharing initiatives. Lastly, involving the public more in the policymaking process was highlighted as a valuable approach to trust-building.

Interviewees highlighted the importance of involving healthcare professionals in the design of health data sharing solutions, given their role as both users and intermediaries between patients and the system. It also emerged that it is important to explain the benefits of such solutions to them and to provide financial incentives or sanctions for their use or non-use of the implemented system. To alleviate the burden of responsibility on healthcare professionals, some suggested adopting a more patient-centric approach to data sharing, which potentially minimises the involvement of healthcare professionals in the data sharing chain.

Data security and privacy emerged as prominent themes. Interviewees emphasised the need to acknowledge data security risks while demonstrating to the public that every possible measure has been taken to protect the data and enhance privacy. Moreover, identifying an external third party for data oversight while ensuring transparency in data access were suggested as viable strategies to build public trust. Lastly, one interviewee pointed out data should be nationally stored.

Concerning the technical aspects of data sharing solutions, interviewees highlighted that standardising taxonomy is necessary to facilitate interoperability and optimise the secondary use of health data, as well as using patient identifiers to link different datasets. Moreover, it was suggested to establish a competence centre to ensure high-quality data at the source.

Overall, interviewees emphasised that the primary prerequisite for establishing trust in a health data sharing solution is its functionality: it must work effectively, benefit all stakeholders and be easy to use. Regarding implementation, one interviewee highlighted the importance of allowing the public to familiarise themselves and build trust with one initiative at a time, such as starting with the eID and then, as a natural second step, adding health data without any imposition from institutions. It was also suggested that a one-size-fits-all solution for health data sharing may not be appropriate, given the diversity of the public. Instead, citizens should be able to choose from multiple user profiles with varying levels of openness to health data sharing.

In line with the Policy Streams Approach [28], we identified two health data sharing policy waves in Switzerland. The first, starting in the late 1990s, focused on establishing legal frameworks for primary health data use, leading to the Federal Act on the Electronic Patient Dossier in 2015. The second, catalysed by the COVID-19 pandemic, centred on developing the legal framework for the secondary use of health data, leading to the initialisation of the DigiSanté national programme in 2023. In contrast, the negative narrative surrounding the implementation of the EPD has become a significant factor eroding public trust. The sustained negative portrayal of this national initiative, primarily driven by the media, has undermined confidence in the administration’s ability to implement it effectively. Consequently, national and international scandals have exacerbated the downward trend in public trust regarding health data sharing initiatives.

The present study revealed that discussions on the secondary use of health data have not yet permeated public discourse. This presents an opportunity for Switzerland to take a proactive approach by applying the learnings from the implementation of the EPD to avoid encountering similar obstacles that could further erode public trust in health data sharing initiatives. Reflecting on the EPD experience, implementation obstacles resulted in delays that contributed to its negative narrative over the years, which affected public trust in the initiative. These obstacles encompass four main categories: (a) Policy process, (b) Public, (c) Healthcare professionals and (d) Technical aspects.

Although the technical challenges of data sharing initiatives – such as ensuring data security, protecting privacy, and addressing patient identifiers and taxonomy alignment – are acknowledged in this study, these technical challenges have already been discussed in other scientific publications [48–51]. Therefore, our discussion will focus on challenges related to (a) Policy process, (b) Public and (c) Healthcare professionals. Building on these insights, we then propose recommendations to inform DigiSanté’s Swiss Data Room project specifically, as well as Swiss and European policymakers in the design and implementation of future health data sharing initiatives more broadly (table 6).

Table 6Recommendations to address past implementation obstacles and enhance public trust for facilitating the implementation of data rooms in Switzerland and Europe.

| Recommendations | Potential implementation challenges | |

| Policy process | Centralise the coordination of the initiative at Federal level. | Switzerland’s decentralised system may resist centralisation unless it prioritises coordination while preserving cantonal autonomy. |

| Facilitate stakeholder discussions to align interests and promote cooperative efforts towards shared goals. | Diverse and conflicting stakeholder priorities, combined with time pressures, may complicate consensus-building. | |

| Public | Conduct targeted communication campaigns to inform the public about both the risks and benefits of the health data sharing initiative. | Reaching diverse demographic groups and ensuring balanced messaging may be challenging, particularly for linguistic minorities and less digitally literate individuals. |

| Implement an effective, user-friendly data sharing solution that benefits both the public and healthcare providers without adding unnecessary burdens. | Balancing simplicity for users with technical and security requirements could complicate design and implementation, especially given resource constraints. | |

| Consider the narrative surrounding the health data sharing initiative, ensure a contingency plan is in place, and adopt a proactive approach to trust-building. | Managing public perception and maintaining trust during crises or negative events requires significant, ongoing effort and adaptability. | |

| Provide citizens with the autonomy to choose between different data sharing models by selecting various types of consent, avoiding one-size-fits-all solutions. | Designing a flexible consent framework that is both user-friendly and compliant with data protection laws might pose technical and administrative challenges. | |

| Healthcare professionals | Engage healthcare professionals in the development phase to ensure the solution meets their requirements. Provide clear explanations of its benefits so they can effectively communicate these to patients. | Ensuring meaningful engagement with healthcare professionals may be challenging due to time constraints, diverse needs and varying levels of digital literacy among practitioners. |

| Consider offering financial support to facilitate their transition to digital practices. | Providing financial support could face budgetary limitations and require careful allocation to ensure equitable distribution across healthcare providers. | |

Interviews with key stakeholders in digital health in Switzerland revealed a perceived disparity between the pace of digitisation and the Swiss policy process. Digitisation has brought the need to streamline the policy process to adapt more swiftly to technological advancements. Politically, Switzerland’s complex governance structure, characterised by federalism, liberalism and direct democracy, impedes rapid and sweeping reforms, favouring incremental changes over fundamental reforms in health policy [52]. Federalism decentralises and fragments the health system, with responsibility divided among the 26 cantons. Liberalism introduces multiple interest groups, including healthcare professionals, insurers and service providers, all of which must be coordinated in the health policymaking process. The direct democracy system, which requires federal, cantonal and sometimes municipal health policy initiatives to be approved by popular vote (referendum), makes voters and interest groups significant veto players. Federalism and the misalignment of stakeholders’ interests were identified by interviewees as key obstacles to the smooth implementation of health data sharing initiatives in Switzerland, such as the EPD. With multiple stakeholders come diverging interests, unless efforts are made to establish a jointly coordinated approach. Without such coordination, key stakeholders in the Swiss system, as exemplified by the EPD experience, may resist adoption, resulting in delays that perpetuate a negative narrative around the initiative, undermining public trust in both current and future health data sharing initiatives.

To overcome these challenges, interviewees suggested centralising the coordination of health data sharing initiatives at the federal level, by involving stakeholders with varying interests to convene and agree on a shared vision and strategy. This approach is essential to ensure that all parties work constructively towards common goals. Given the peculiarities of Swiss federalism and decentralisation, Switzerland requires a bottom-up approach that actively engages cantonal authorities and local stakeholders in the decision-making process, unlike centralised countries such as France, where directives can be uniformly implemented [53]. In centralised governance structures, uniform policy directives and streamlined decision-making are facilitated at the national level by a central authority – such as the Ministry of Health or specialised agencies like the French Health Data Hub – that oversee the development, implementation and regulation of national health initiatives uniformly applied across regions [54]. In contrast, Switzerland’s decentralisation necessitates coordination mechanisms that respect cantonal autonomy while fostering collaboration at the federal level. The establishment of eHealth Suisse in 2007, a national coordination body for eHealth, was an initial attempt to address the challenges posed by federalism, tasked with promoting interoperability at technical, legal and political levels by integrating federal and cantonal levels of governments [4]. The launch of the DigiSanté programme in 2025 offers a promising step forward, as DigiSanté is envisioned as having a coordinating role, by setting objectives and guiding stakeholders in pursuing a common vision and the goals derived from it. One of the programme’s four strategic objectives is to orchestrate activities for the digital transformation of the healthcare system, ensuring alignment towards common goals and maximising impact by engaging relevant stakeholders in the healthcare sector [3]. Stakeholder involvement and networking within the programme will be facilitated through various channels, including “DigiSanté Roundtables”, a digital exchange format designed to foster informal discussions on the specific challenges of healthcare digitalisation. Additionally, ad hoc events and a newsletter subscription will be available to provide updates on the programme’s progress and milestones [55]. If the FOPH fulfils DigiSanté’s objectives, it could offer a viable solution to overcoming some key obstacles that hindered the EPD initiative in the past.

Low public awareness was cited as a reason for slow EPD implementation. Although the 2007 Swiss e-Health Strategy aimed for full implementation and accessibility of the EPD by 2015, structured public information campaigns only began in June 2023, targeting healthcare professionals, with campaigns for the general population starting in 2024 [42]. Communication is a key principle in trust theory [1]: timely, clear and audience-tailored communication, highlighting the risks and benefits of the data sharing solution, is essential for empowering the public to make informed decisions and ultimately trust the implemented solution. Moreover, ongoing public engagement from the early stages of the policy process is crucial for establishing trust, as it promotes both the co-design of the solution and the awareness-building process.

The study also highlights the importance of monitoring the narratives presented by news outlets and experts regarding the initiative being implemented, as these narratives can directly influence public trust. As interviewees highlighted, scandals erode public trust, but prolonged negative narratives, such as those surrounding the implementation of the EPD, have a more significant long-term impact. Given that the EPD experience serves as a reference point for the Swiss public’s collective experience with national health data sharing initiatives, it is crucial for health policymakers and implementers to establish contingency plans to rebuild public trust in such initiatives. Moreover, proactive trust-building measures should be undertaken when developing and implementing future health data sharing initiatives, such as the Swiss Data Room. Looking at neighbouring countries, France experienced a similar situation to Switzerland’s EPD with the implementation of their “Dossier Médical Personnalisé” (DMP) in 2007. The adoption of the DMP initially faced limitations, delays and criticisms. In 2022, the French Ministry of Health launched “Mon espace santé”, a more user-friendly and comprehensive rebranding of the DMP [56]. This successful relaunch enabled France to reach a participation rate of over 95% of socially insured people as of 2024, accounting for almost 17% of the population [57], compared to the 0.22% of the Swiss population as of April 2023 [9].

Several aspects may have contributed to the success of the French programme Mon espace santé. The programme was implemented using a top-down, user-centric approach. This included iterative developments, regular user testing and citizen workshops from the pilot phase onward. The programme adopted an opt-out model and provided financial incentives to healthcare professionals, facilitating adoption. A major driver of adoption was a three-wave national communication campaign launched in February 2022, aligned with the programme’s rollout. This contrasts with Switzerland, where communication about the EPD began only in June 2023, six years after the EPD regulation’s enforcement. The French campaign emphasised patient-centred benefits through diverse channels including TV, online videos, radio, magazines, social media and in-person promotions at pharmacies, laboratories and healthcare establishments. In addition, the initiative also employed influencer ambassadors to promote Mon espace santé and established a network of nearly 4000 digital advisors and mediators, including professional caregivers, tasked with raising awareness and supporting citizens – especially underrepresented groups or those less familiar with digital technology – through outreach and education [56]. Given Switzerland’s diverse migrant communities, which are recognised as minority groups requiring additional outreach efforts, strategies to engage underrepresented groups should be considered in Switzerland’s upcoming initiatives.

Insights from unpublished studies and the current research underscore that the non-user-friendly interface and complex registration process of the EPD were prominent obstacles to its implementation [41]. Therefore, in order to establish public trust in future health data sharing initiatives, it is crucial, as supported by the Technology Acceptance Model [58], that the implemented data sharing solution is effective, user-friendly and provides clear benefits to both the public and healthcare providers, offering added value for all stakeholders without imposing unnecessary burdens. Interviewees emphasised that a one-size-fits-all solution for the secondary use of health data is not viable, as it is important to give citizens autonomy to choose between different profiles based on their willingness to share certain types of data with specific parties. These profiles could be associated with different consent models, ranging from the broad consent model [59], where data owners consent to multiple future studies from both private and public researchers, the nature and specificities of which are not known at the time of consenting; to a more conservative profile where data owners select which data can be shared and with whom. This latter approach can align with the dynamic consent model, which provides a transparent, flexible and user-friendly means for data owners to consent over time and receive information about the uses of their data [60].

Healthcare professionals, particularly physicians, play a pivotal role in the discourse on health data sharing as they directly influence both the health policy processes and public opinion. Politically, physicians are influential actors in Switzerland, with the FMH serving as a powerful interest group in health policy [61]. From the patient’s perspective, physicians historically serve as the primary point of contact within the healthcare system and are seen as trusted anchors. Patients rely on their expertise and guidance, highly valuing their opinions [62], with healthcare providers playing a role in reducing patient privacy concerns and enhancing their intention to share personal health data [10]. Therefore, physicians act as essential intermediaries between policy and public opinion, serving as gatekeepers in the discourse on health data sharing.

The analysis of news articles, expert opinion papers and interviews revealed that healthcare professionals supported the Electronic Patient Dossier in principle but were not favourable towards its implementation strategy. Three main obstacles emerged: limited perceived benefits of the solution due to their poor involvement in its development and in the policymaking process, resulting in an EPD not reflecting healthcare professionals’ needs; concerns about the trust relationship with patients being endangered by data sharing initiatives; and an anticipated increase in administrative burden, especially in the initial phase of EPD implementation, prompting calls for financial incentives and compensation systems [63]. These obstacles in the EPD experience resulted in limited support from the FMH, with physicians not consistently advocating for the EPD to their patients, who typically follow their doctors’ advice, leading to low adoption rates.

While a patient-centred solution was mentioned as a way to mitigate physicians’ perceived burden of protecting patient data, given the crucial role physicians play in both policy development and shaping public perception, it is advisable to invest in their involvement instead. This can be achieved by actively engaging them from the early stages of policymaking and solution development to ensure the solution meets their requirements, and by clearly explaining its benefits so they can effectively communicate these to patients. Additionally, offering financial incentives will support their digital transition.

The recommendations provided in this study are relevant for health data sharing initiatives in Switzerland and beyond. Policymakers involved in the Swiss DigiSanté programme, as well as those working on the conceptualisation and development of European and national health data spaces, should consider the following:

It is therefore crucial to reflect on each state’s past experiences with health data sharing and to plan strategies to rebuild or maintain public trust. Additionally, the narrative surrounding such initiatives in the media should be closely monitored. Both the public and healthcare professionals should be actively engaged from the outset of these initiatives to ensure that the data sharing solution meets their needs as users. For healthcare professionals specifically, early involvement will enable them to be informed about it and eventually recommend the solution with confidence to the public.

This study represents a novel contribution to the field as it integrates data from four distinct data sources to investigate dimensions of policy, media narrative and expert opinion spanning 31 years. To our knowledge, it is the first study to comprehensively analyse the past experience of the Swiss public in health data sharing, thus informing future data sharing initiatives. Previous research is limited to studies primarily focused on specific policy analysis, such as investigating the process of adopting the Federal Law on Electronic Health Records [4], as well as on legal, ethical and logistical obstacles to health data sharing through literature reviews or stakeholder interviews alone [49, 63, 64].

The accuracy of news searches from newspaper archives might be compromised due to inconsistent search engine performance. The newspaper “Neue Zürcher Zeitung” (NZZ) had to be excluded from the analysis due to the impossibility of accessing and downloading their articles in digital form. This may pose a limitation in the analysis and generalisability of findings from news articles in the German-speaking region of Switzerland, as the inclusion of the centre-right leaning NZZ would have balanced the other two newspapers, “Der Bund” and “Tages Anzeiger”, which are more left-wing.

For the scoping review of expert opinion papers, the limited inclusion of Swiss journals representing all three linguistic regions equally constitutes a limitation of our study. Future research should consider broader inclusion of regionally representative sources to ensure a more comprehensive representation of Switzerland’s multilingual and multicultural context.

The digitisation trend of the early 2000s and the COVID-19 pandemic influenced the sociopolitical discourse on health data sharing in Switzerland, by raising public awareness on the potential of health data and driving two waves of intense policy activity. However, the negative narrative on the EPD, compounded by national and international scandals, largely frames public trust in health data sharing at present, serving as the Swiss public’s reference point for national health data sharing initiatives. It is opportune to learn from the obstacles faced during the EPD implementation, to extract valuable lessons applicable to upcoming health data sharing initiatives. At the policy level, it is recommended to centralise the coordination of initiatives at the federal level, while fostering active collaboration among stakeholders to align interests and promote cooperative efforts towards common goals. At the public level, a comprehensive public engagement strategy is advised, with a focus on implementing effective, user-friendly solutions that offer citizens autonomy of choice, while monitoring the narrative surrounding the initiative and adopting a proactive approach to trust-building. Healthcare professionals should be involved in the development of the solution and the policymaking process from the outset and should receive financial support to facilitate their digital transition. Given the promising health data sharing initiatives in the Swiss pipeline as part of the DigiSanté programme, it is crucial to consider these recommendations. Failing to do so risks implementation delays and the perpetuation of negative narratives, ultimately undermining public trust in both current and future efforts to advance health data sharing in Switzerland, as has occurred in the past.

The anonymised interview data supporting this study are available on Zenodo (10.5281/zenodo.14384120).

We thank Ms Jacqueline Huber, a librarian at the University of Zurich, for her guidance during the scoping review. We extend our appreciation to the advisory board members for their valuable guidance and feedback throughout the study: Sigrid Beer-Borst and Thorsten Kühn from the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, Manuel Kugler from the Swiss Academy of Engineering Sciences (SATW), Mathis Brauchbar from Advocacy AG, Alfred Angerer from the Zurich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW) and Mélanie Levy from the Université de Neuchâtel (UNINE). Sigrid Beer-Borst and Thorsten Kühn, Federal Office of Public Health, provided content-related support in relation to DigiSanté package four.

Author contributions: FZ drafted the manuscript. PD, FG and VvW reviewed and edited the manuscript.

This research project was co-initiated by Novartis and received financial support from Novartis International AG. The research activities and the formulation of policy recommendations were carried out independently of Novartis. The Sanitas health insurance foundation is providing financial support for this project with the aim of initiating a broad sociopolitical discussion about the possible introduction of a Swiss health data space. The funders had no role in the study design and research process. The article was written independently of the funders.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. FG receives funding from Novartis International AG and Sanitas health insurance foundation. FZ is funded by the Digital Society Initiative, University of Zurich. FZ and PD received funding through the project budget of this study by Novartis International AG and Sanitas health insurance foundation. Outside of this work, FG receives funding from the Swiss Academy of Engineering Sciences, Digital Society Initiative, University of Zurich, and the World Health Organization. Unrelated to this project, FG works at the Federal Chancellery of Switzerland, the views expressed in this article are the views of FG alone and not of the Federal Chancellery.

1. Gille F. What Is Public Trust in the Health System?: Insights into Health Data Use. Bristol: Policy Press; 2023.

2. Schmitt T, Cosgrove S, Pajić V, Papadopoulos K, Gille F. What does it take to create a European Health Data Space? International commitments and national realities. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2023 Jun;179:1–7.

3. Federal Office of Public Health. Digisanté: Promozione della Trasformazione Digitale Nel settore sanitario. Bundesamt für Gesundheit. 2024. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/it/home/strategie-und-politik/nationale-gesundheitsstrategien/digisante.html#1104378112

4. De Pietro C, Francetic I. E-health in Switzerland: the laborious adoption of the federal law on electronic health records (EHR) and health information exchange (HIE) networks. Health Policy. 2018 Feb;122(2):69–74.

5. Misztal BA. Trust in Modern Societies. 1st ed. Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers Inc; 1996.

6. Turper S, Aarts K. Political Trust and Sophistication: Taking Measurement Seriously. Soc Indic Res. 2017;130(1):415–34.

7. Sztompka P. Trust a sociological theory. Cambridge cultural, social studies. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press; 1999.

8. Federal Office of Justice. Implementing the eID. 2024. Available from: https://www.digital-public-services-switzerland.ch/en/implementation/egovernment-implementation-plan/implementing-the-eid

9. Federal Office of Public Health. Electronic patient records in figures. 2023. Available from: https://www.newsd.admin.ch/newsd/message/attachments/80391.pdf

10. Cherif E, Bezaz N, Mzoughi M. Do personal health concerns and trust in healthcare providers mitigate privacy concerns? Effects on patients’ intention to share personal health data on electronic health records. Soc Sci Med. 2021 Aug;283:114146.

11. Federal Office of Public Health. The Federal Council’s health policy strategy 2020–2030. 2024. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/strategie-und-politik/gesundheit-2030/gesundheitspolitische-strategie-2030.html#:~:text=With%20its%20health%20policy%20strategy,for%20all%20health%20system%20actors

12. Federal Office of Communications. Code of conduct for operating trustworthy data spaces. 2023. Available from: https://www.bakom.admin.ch/bakom/en/home/digital-und-internet/strategie-digitale-schweiz/datenpolitik/verhaltenskodex.html

13. Luhmann N. Trust and power. Chichester: Wiley; 1979.

14. Mutz DC, Soss J. Reading Public Opinion: The Influence of News Coverage on Perceptions of Public Sentiment. Public Opin Q. 1997;61(3):431.

15. Gunther AC. The Persuasive Press Inference: Effects of Mass Media on Perceived Public Opinion. Communic Res. 1998 Oct;25(5):486–504.

16. Page BI, Shapiro RY, Dempsey GR. What Moves Public Opinion? Am Polit Sci Rev. 1987 Mar;81(1):23–43.

17. Greve-Poulsen K, Larsen FK, Pedersen RT, Albæk E. No Gender Bias in Audience Perceptions of Male and Female Experts in the News: Equally Competent and Persuasive. Int J Press/Polit. 2023 Jan;28(1):116–37.

18. De Benedetto M, Lupo N, Rangone N. The crisis of confidence in legislation: proceedings of the annual conference of the International association of legislation (IAL) in Rome, October 25th, 2019. in International association of legislation, no. 19. Baden-Baden: Nomos; 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.5040/9781509939862

19. Rochel J. Error 404: looking for trust in international law on digital technologies. Law Innov Technol. 2023 Jan;15(1):148–84.

20. Zavattaro F, von Wyl V, Gille F. Examining the Inclusion of Trust and Trust-Building Principles in European Union, Italian, French, and Swiss Health Data Sharing Legislations: A Framework Analysis. Milbank Q. 2024 Dec;102(4):973–1003.

21. Daniore P, Zavattaro F, Gille F. Public Trust in a Swiss Health Data Space. 2024 Oct; doi:

22. Teherani A, Martimianakis T, Stenfors-Hayes T, Wadhwa A, Varpio L. Choosing a Qualitative Research Approach. J Grad Med Educ. 2015 Dec;7(4):669–70.

23. Federal Statistical Office. Languages. Available from: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/population/languages-religions/languages.html

24. Pope C, Mays N. Qualitative Research in Health Care. 4th ed. Newark: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated; 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119410867

25. Braun V, Clarke V, Hayfield N, Terry G. Thematic Analysis. In: Liamputtong P, editor. Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Singapore: Springer; 2018.

26. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007 Dec;19(6):349–57.

27. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005 Feb;8(1):19–32.

28. Kingdon JW. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Longman classics in political science. 2nd ed. New York: Longman; 2003.

29. Ludwig C. Qualitätsstandards für das computerbasierte Patientendossier. Initiative “Patientendossier 2003” der schweizerischen Universitätsspitälter. 2001. Available from: https://saez.swisshealthweb.ch/de/article/doi/saez.2001.07965/

30. Trezzini M. Swiss online vaccine registry probed for data security issues, swissinfo.ch. Available from: https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/politics/swiss-online-vaccine-registry-probed-for-data-security-issues/46471504

31. The Guardian. Edward Snowden: the whistleblower behind the NSA surveillance revelations. 2013. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jun/09/edward-snowden-nsa-whistleblower-surveillance

32. The Guardian. Revealed: 50 million facebook profiles harvested for cambridge analytica in major data breach. na. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/mar/17/cambridge-analytica-facebook-influence-us-election

33. Le Temps. Enquête ouverte après des failles informatiques concernant le registre national du don d’organes. 2022. Available from: https://www.letemps.ch/suisse/enquete-ouverte-apres-failles-informatiques-concernant-registre-national-don-dorganes

34. Seydtaghia A. Les données médicales de milliers de Neuchâtelois ont été mises en ligne. Le Temps. 2022 Mar 30. Available from: https://www.letemps.ch/cyber/donnees-medicales-milliers-neuchatelois-ont-mises-ligne

35. Birrer R. Wir leisten uns zu viel Luxus im Gesundheits¬wesen. Tages-Anzeiger. 2023. Available from: https://www.tagesanzeiger.ch/leitartikel-zum-praemienschock-wir-leisten-uns-zu-viel-luxus-175648144529

36. Zürcher C. Warum das Patientendossier ein Murks ist. Tages-Anzeiger. 2023. Available from: https://www.tagesanzeiger.ch/digitalisierung-des-gesundheitswesens-warum-das-patientendossier-ein-murks-ist-816824845132

37. Lovis C, Geissbühler A. Le dossier de soin: un outil de travail pour les soignants et un instrument de pilotage au service du patient. Swiss Med Inform. 2003 Mar.

38. Stoffel U. La loi sur le dossier électronique du patient: une opportunité. www.swisshealthweb.ch. 2015. Available from: https://www.swisshealthweb.ch/fr/article/doi/bms.2015.04203/

39. Gilli Y. Le dossier électronique du patient traverse une phase critique. Swisshealthweb. 2016. Available from: https://www.swisshealthweb.ch/fileadmin/assets/SAEZ/2016/bms.2016.05000/bms-2016-05000.pdf

40. Huber F. Das Bag soll keine Weiteren Kompetenzen Mehr erhalten. Swisshealthweb. 2022. Available from: https://www.swisshealthweb.ch/de/article/doi/saez.2022.20526/ doi: https://doi.org/10.4414/saez.2022.20526

41. Zimmer A. Das Digitale Gesundheitssystem: Achtung Baustelle. www.swisshealthweb.ch. 2022. Available from: https://www.swisshealthweb.ch/de/article/doi/saez.2022.21300/

42. Zimmer A. Jahresrückblick. www.swisshealthweb.ch. 2023. Available from: https://saez.swisshealthweb.ch/de/article/doi/saez.2023.1282904944/

43. De Haller J. Des données trop séduisantes. www.swisshealthweb.ch. 2010. Available from: https://www.swisshealthweb.ch/fr/article/doi/bms.2010.15648/

44. Printzen G. Loi sur le dossier électronique du patient – enjeux et écueils. www.swisshealthweb.ch. 2013. Available from: https://www.swisshealthweb.ch/fr/article/doi/bms.2013.02128/

45. De Haller J. Données médicales: quelle dose de transparence, à l’avenir? www.swisshealthweb.ch. 2015. Available from: ww.swisshealthweb.ch/fr/article/doi/bms.2015.03245/

46. Gilli Y. Le dossier électronique du patient: la solution miracle? Swisshealthweb. 2017. Available from: https://saez.swisshealthweb.ch/fr/article/doi/bms.2017.06128/

47. Zimmer A. Le dossier électronique du patient vous concerne, nous aussi! www.swisshealthweb.ch. 2021. Available from: https://www.swisshealthweb.ch/fr/article/doi/bms.2021.20157/

48. Gaudet-Blavignac C, Raisaro JL, Touré V, Österle S, Crameri K, Lovis C. A National, Semantic-Driven, Three-Pillar Strategy to Enable Health Data Secondary Usage Interoperability for Research Within the Swiss Personalized Health Network: methodological Study. JMIR Med Inform. 2021 Jun;9(6):e27591.

49. Solmaz G, et al. Enabling data spaces: existing developments and challenges. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Data Economy, Rome Italy: ACM; Dec. 2022. 42–48. doi:

50. Ormond KE, Bavamian S, Becherer C, Currat C, Joerger F, Geiger TR, et al. What are the bottlenecks to health data sharing in Switzerland? An interview study. Swiss Med Wkly. 2024 Jan;154(1):3538.

51. SPHN. The SPHN Semantic Interoperability Framework. Available from: https://sphn.ch/network/data-coordination-center/the-sphn-semantic-interoperability-framework/