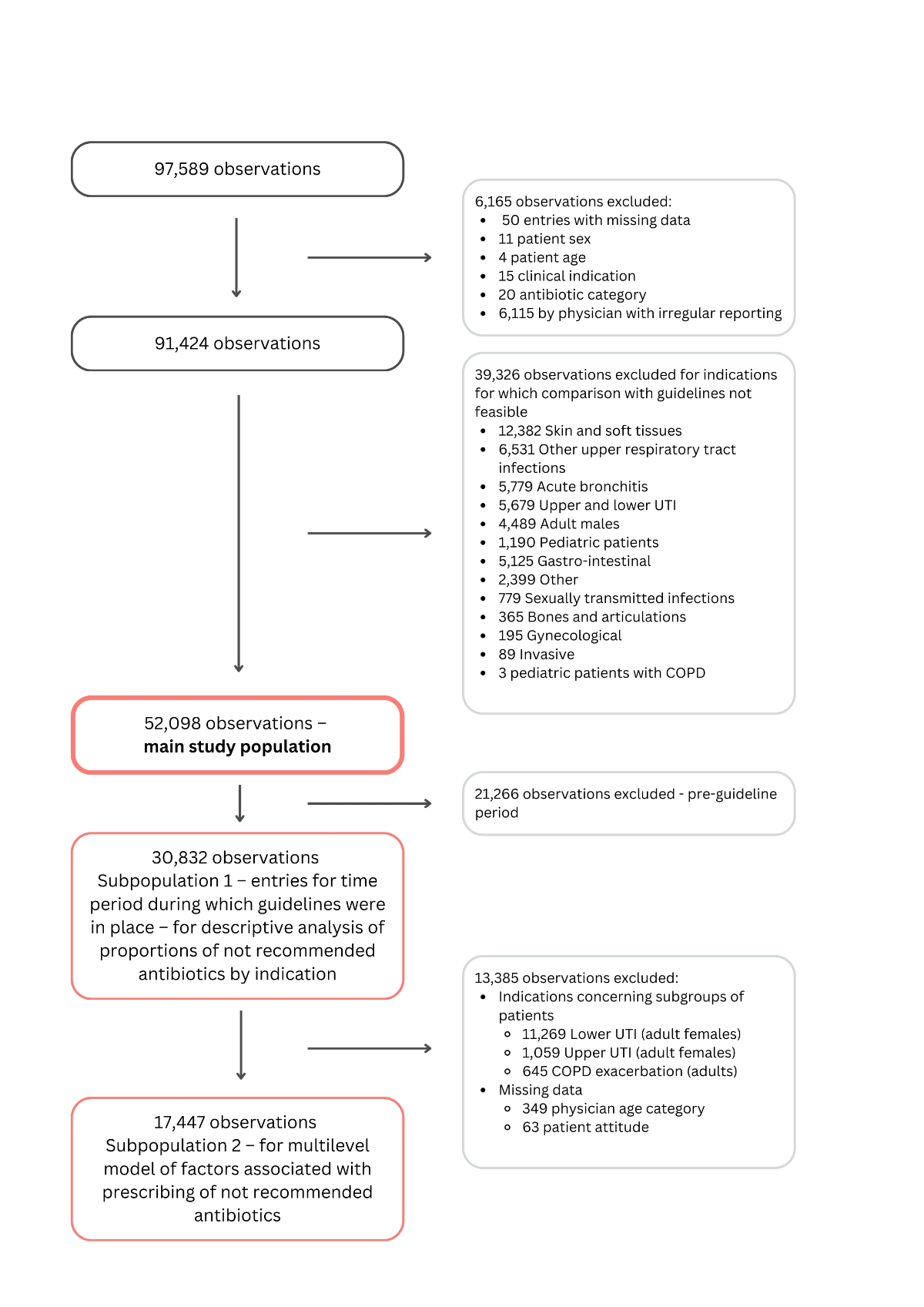

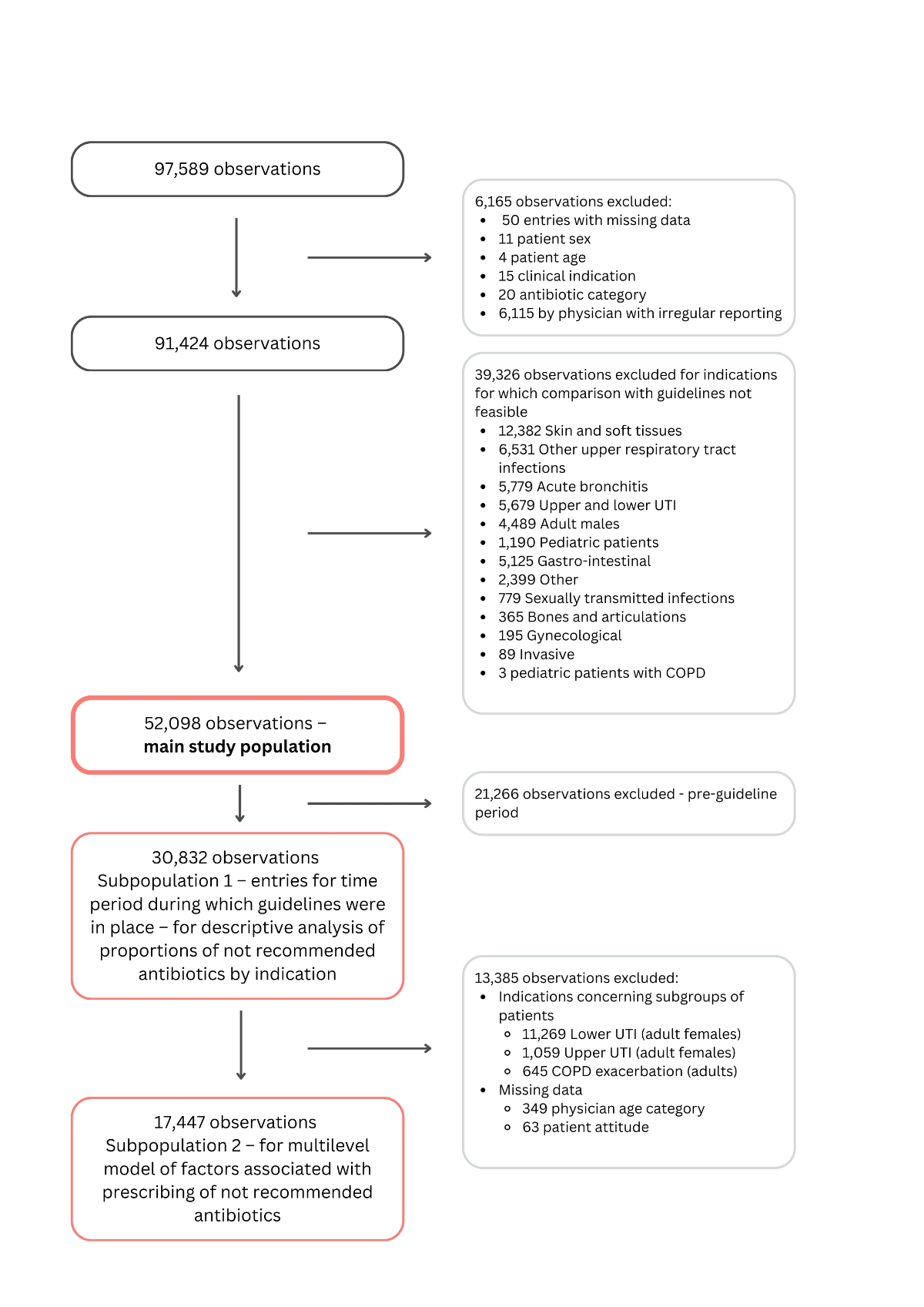

Figure 1Study flowchart. COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; UTI: urinary tract infection.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4234

Antimicrobial resistance causes significant morbidity and mortality worldwide [1]. Misuse of antibiotics contributes to the development of antimicrobial resistance. Appropriate use of antibiotics is defined as prescribing antibiotics according to guidelines or more broadly by the World Health Organization (WHO) and others who emphasise prescribing antibiotics only when necessary, alongside employing a suitable regimen, dosage, mode of delivery and treatment duration [2, 3]. Optimisation of use of antibiotics is one of the objectives of the global action plan on antimicrobial resistance developed by the WHO [4].

Antibiotic prescribing in outpatient care accounts for most antibiotics prescribed in many countries [5–7]. Therefore, the outpatient sector represents an important target for antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) activities aimed at reducing antimicrobial resistance. The proportion of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in outpatient care can reach 71% [8]. Inappropriateness depends on the indication, with higher proportions of inappropriate use for respiratory tract infections (22–71 %) and lower proportions for urinary tract infections (2–37%) [8–12].

In Switzerland, 87% of all antibiotics are prescribed in outpatient care [7] of which most are prescribed for respiratory tract infections, 47%, and urinary tract infections, 32% [13]. In an effort to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing, starting from 2019 the Swiss Society of Infectious Diseases (SSI) introduced national guidelines for common infectious diseases, for both adults and children [14]. However, it remains unclear whether Swiss family physicians and paediatricians prescribe the antibiotics recommended by these guidelines.

Factors associated with increased likelihood of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing include patient-related factors, for example patient’s demand for antibiotic prescription, physician-related factors such as greater work experience, and factors related to professional culture, for example unawareness of the role of primary care in development of antimicrobial resistance, incompleteness of guidelines or guidelines not tailored to the realm of family medicine consultations [15–20].

The aims of this study were to assess whether Swiss family physicians and paediatricians make appropriate antibiotic choices in accordance with national guidelines and to identify physician- and patient-related factors associated with the prescribing of not-recommended antibiotic choices for specific indications.

We conducted a cross-sectional study using antibiotic prescription reports from a sentinel physician surveillance network for the period 2017–2022.

Sentinella is a representative surveillance network consisting of approximately 200 Swiss family physicians and paediatricians who report to the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) on various topics related to infectious disease surveillance, including antibiotic prescribing by clinical indication [21, 22]. The study team was commissioned by the Federal Office of Public Health to analyse data from the Sentinella surveillance network as part of routine surveillance activities. As such, no formal protocol was prepared or published for this study.

Physicians participating in Sentinella report weekly on every patient for whom they have prescribed an antibiotic therapy. While the majority of physicians participating in Sentinella are consistent participants over several years, some rotate in and out annually. Data included a deidentified physician code but no patient identifier, hence it was impossible to determine whether multiple prescribing episodes corresponded to the same patient.

Each observation contained the following information: indication (predefined categories), antibiotic class (predefined categories), patient age in years, consultation date, sex, patient’s attitude towards the prescription according to the physician (neutral, favourable, unfavourable). Physician-level data included deidentified physician code, specialty (general internal medicine or paediatrics), type of practice (individual or group), canton, municipality, urban-rural typology of the practice (urban, rural or intermediate), language region of the practice (French, German or Italian), age (by 5-year category) and sex. Physician age was further grouped into 3 categories: 31–45 years, 46–65 years and 66 years or older. While physicians practicing individually had their own physician code, group-practice physicians could share the same code; therefore for physicians practicing in a group, a mean age category of all physicians of the group practice was determined. Physician’s sex in a group practice was classified as follows: male if all physicians were male, female if all were female and mixed if both male and female physicians were present.

We identified specific indications from the Sentinella dataset where comparisons with national guidelines were feasible. This selection was based on assessing the compatibility of indications, patient age and sex categories. The included indications were pharyngitis, sinusitis, otitis media, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation (limited to adults), pneumonia, and upper and lower urinary tract infections (limited to adult female patients). The Sentinella dataset includes several indications that were excluded from our study due to the absence of corresponding guidelines. Entries from physicians reporting irregularly (fewer than 39 weeks per year) were excluded, in accordance with the methodology used by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health to ensure consistency with national surveillance reports.

For indications where a national guideline was available, we listed the antibiotics mentioned in the guideline and determined a corresponding antibiotic category in the Sentinella dataset (see appendix 1). The guidelines categorise antibiotics into first-line and second-line treatments, with the latter typically reserved for specific cases such as allergies or comorbidities. However, since the dataset had limited information about individual patient characteristics, such as allergies and comorbidities, we combined first-line and second-line treatments into a single “recommended” category for the majority of analyses. Conversely, prescriptions were categorised as “not-recommended” if they involved antibiotic categories that were not mentioned at all in the guideline for the clinical indication in question.

A descriptive analysis was conducted on antibiotic prescription reports, focusing on patient characteristics and physician practice characteristics associated with the prescriptions. Additionally, the most common antibiotic categories by indication, proportions of first- and second-line treatments by indication and the proportion of recommended and not-recommended antibiotics, overall and by indication, were determined, for the period during which guidelines were in place. National guidelines for pharyngitis, sinusitis, otitis media, upper and lower urinary tract infections were introduced by the Swiss Society of Infectious Diseases in 2019, and for pneumonia and COPD exacerbation in 2020.

Given that the treatment section of Swiss Society of Infectious Diseases guidelines provides separate recommendations for adults (16 years and older) and children (15 years and younger), the results for these populations were analysed separately. Proportions of not-recommended antibiotic classes by indication in male and female patients were compared using chi-squared tests. In addition, a chi-squared test was used to compare the proportion of not-recommended antibiotics before and after guideline implementation.

A univariate logistic regression was initially performed to analyse the relationship between prescribing not-recommended antibiotics and predictors at both the physician and patient levels. This analysis used the same outcome and predictors as the subsequent multilevel model. Following the univariate analysis, a multilevel model was conducted to further examine these relationships, treating physician (or group practice) code as a random effect. Physician-level fixed effects included linguistic region, urban-rural typology, practice type, specialty, mean age category and sex. Patient-level fixed effects comprised age group, indication, sex, attitude towards antibiotic prescription perceived by physician and consultation year. Several clinical indications (upper and lower urinary tract infections, COPD) were excluded from this analysis, as entries for these conditions were limited according to age and sex criteria. Covariates were selected based on evidence from the literature [15–20], which identifies key determinants of antibiotic prescribing practices, and the clinical and research expertise of the author team, including specialists in infectious diseases and family medicine.

Model fit was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, null model fitting and deviance testing, as well as classification accuracy via confusion matrix evaluation. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was assessed to quantify the proportion of total variance in prescribing practices attributable to the physician (or group practice) level. Urinary tract infections (upper and lower) and COPD exacerbation were excluded from the model as they were limited to specific patient subgroups (adult females for urinary tract infections and all adults for COPD exacerbation).

Entries missing patient sex, age, indication or antibiotic category were excluded from all analyses. For the multilevel analysis, entries missing mean physician practice age category or patient-level data on attitude towards prescription were also excluded.

Statistical analyses were performed in statistical software R version 4.4.0 [23]. Appendix 2 specifies R packages that were used during the analysis. Differences were considered statistically significant in cases of p-value <0.05. Certain figures generated in R were refined in Canva by adjusting font sizes and incorporating additional labels where necessary to enhance clarity and readability [24].

The study was deemed to be outside the scope of the Swiss Human Research Act by the Cantonal Commission on Research Ethics (CER-VD).

From 1 January 2017 to 30 December 2022, 97,589 antibiotic prescription reports were made to Sentinella by participating physicians. After exclusion of observations with missing patient-level data (n = 50), entries from physicians who do not report regularly (n = 6115), as well as indications for which the comparison between Sentinella data and the guidelines was not feasible (n = 39,326), 52,098 observations were included in the analysis (figure 1). The most common excluded indications were skin and soft tissue infections, upper respiratory tract infections and acute bronchitis.

Figure 1Study flowchart. COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; UTI: urinary tract infection.

The 52,098 observations concerned 35,617 adults and 16,481 children. The median (IQR [interquartile range]) age of adults and children was 57 (IQR: 37–74) and 5 (IQR: 2–7) years, respectively. The patient was female in 79% (n = 28,063) of observations for adults and 47% (n = 7787) of observations for children (table 1). The most common indications in adults were lower urinary tract infection (46%; n = 16,413) and sinusitis (15%; n = 5161). The most common indications for children were otitis media (61%; n = 10,108) and pharyngitis (31%; n = 5123). The most common patient attitude towards antibiotic prescription was a neutral attitude both for adults (82%; n = 29,285) and children (93%; n = 15,254).

Table 1Characteristics of patients.

| Patient characteristics (52,098 entries) | |||

| Adults, n = 35,617 | Children, n = 16,481 | ||

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 57 (37–74) | 5 (2–7) | |

| Sex, n (%) | Female | 28,063 (78.8%) | 7787 (47.2%) |

| Male | 7554 (21.2%) | 8694 (52.8%) | |

| Clinical indication, n (%) | Pharyngitis | 3784 (10.6%) | 5123 (31.1%) |

| Sinusitis | 5161 (14.5%) | 270 (1.6%) | |

| Otitis media | 2151 (6.0%) | 10,108 (61.3%) | |

| Pneumonia | 4438 (12.5%) | 980 (5.9%) | |

| COPD exacerbation | 2044 (5.7%) | NA | |

| Upper urinary tract infection | 1626 (4.6%) | NA | |

| Lower urinary tract infection | 16,413 (46.1%) | NA | |

| Patient’s (or guardian’s) attitude towards antibiotic prescription as perceived and reported by physician, n (%) | Neutral | 29,285 (82.2%) | 15,254 (92.5%) |

| Favourable | 5673 (15.9%) | 811 (4.9%) | |

| Unfavourable | 489 (1.4%) | 381 (2.3%) | |

| Missing | 170 (0.5%) | 35 (0.2%) | |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IQR: interquartile range.

From 2017 to 2022, 219 physician practices contributed to Sentinella (table 2). The majority were group practices (58%; n = 128), specialists in general internal medicine (85%; n = 187), male physicians (62%; n = 135), located in urban settings (74%; n = 162) and in the German-speaking region (65%; n = 142). The most common physician age group was 46–65 years (61%; n = 133).

Table 2Characteristics of physician practices.

| Characteristic | All practice types | Group practices | Solo practices | |

| n = 219 | n = 128 | n = 91 | ||

| Age category* | 31–45 years | 51 (23.3%) | 41 (32.0%) | 10 (11.0%) |

| 46–65 years | 133 (60.7%) | 80 (62.5%) | 53 (58.2%) | |

| 66 years or older | 32 (14.6%) | 6 (4.7%) | 26 (28.6%) | |

| Missing | 3 (0.0%) | 1 (0.0%) | 2 (0.0%) | |

| Specialty | General internal medicine | 187 (85.4%) | 111 (86.7%) | 76 (83.5%) |

| Paediatrics | 32 (14.6%) | 17 (13.3%) | 15 (16.5%) | |

| Sex | Female | 68 (31.1%) | 47 (36.7%) | 21 (23.1%) |

| Male | 135 (61.6%) | 65 (50.8%) | 70 (76.9%) | |

| Mixed** | 16 (7.3%) | 16 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Urban-rural typology | Urban | 162 (74.0%) | 99 (77.3%) | 63 (69.2%) |

| Intermediate | 37 (16.9%) | 22 (17.2%) | 15 (16.5%) | |

| Rural | 20 (9.1%) | 7 (5.5%) | 13 (14.3%) | |

| Linguistic region | German | 142 (64.8%) | 85 (66.4%) | 57 (62.6%) |

| French | 61 (27.9%) | 35 (27.3%) | 26 (28.6%) | |

| Italian | 16 (7.3%) | 8 (6.3%) | 8 (8.8%) | |

* For group practices mean age group was calculated.

** Mixed sex corresponds to group practices where both male and female physicians were practicing.

The overall proportion of not-recommended antibiotic prescriptions was 18% (n = 3897) for adults and 19% (n = 1794) for children.

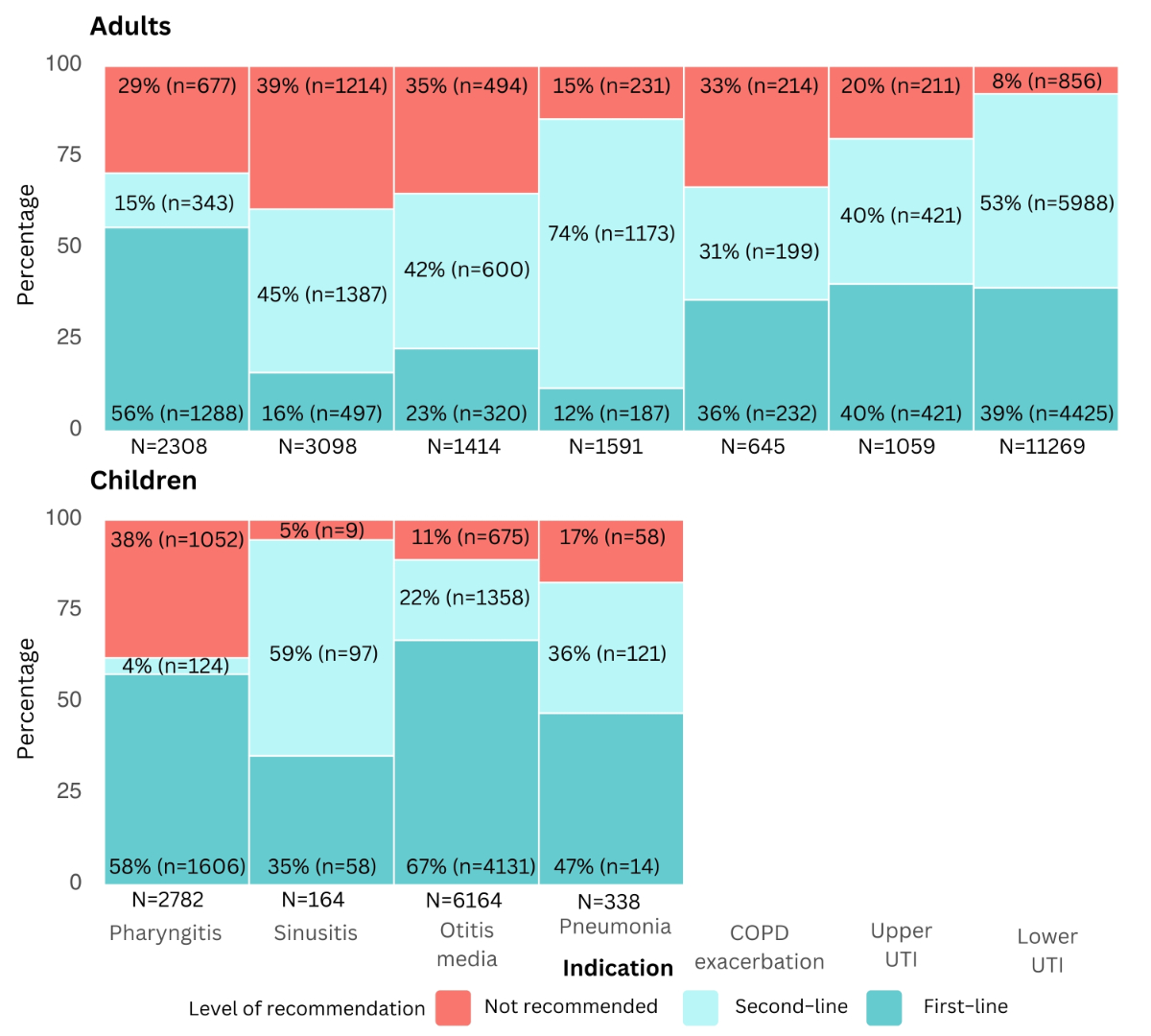

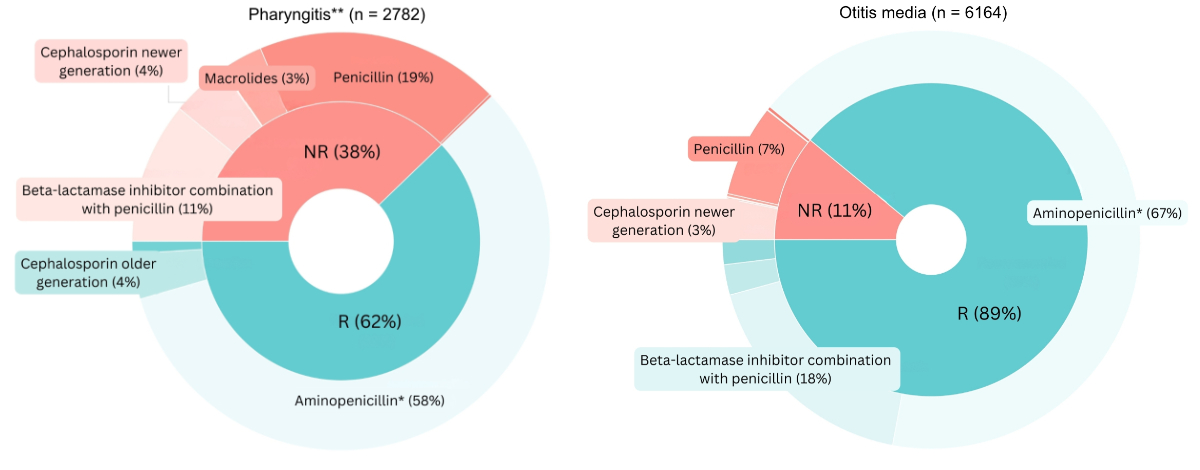

For adults, the proportion of not-recommended antibiotics ranged from 8% for lower urinary tract infections (n = 856) to 39% for sinusitis (n = 1214). In children, the proportion of not- recommended antibiotics was lower than in adults in all indications except for pharyngitis (figure 2). The proportion of first-line treatments was lower than that of second-line treatments across several indications in adult patients. The highest proportion of second-line treatments was observed in pneumonia, where they accounted for 74% (n = 1173) compared to 12% (n = 187) for first-line treatments (figure 2).

Figure 2Proportion of recommended and not-recommended antibiotic prescriptions, by clinical indication since the introduction of national guidelines. Recommended treatments include first- and second-line treatments suggested by the guideline, while not-recommended treatments are treatments not mentioned in the guideline for a given indication. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation, upper and lower urinary tract infection (UTI) were excluded in case of children as there was no corresponding national guideline. For upper UTI and lower UTI, analyses were performed for female patients only. Entries with missing data (n = 50), specifically related to patient sex, age, clinical indications and antibiotic categories, were excluded from all analyses at the first step of the flowchart, without selective exclusion from specific figures. n: total number of prescriptions for a specific indication.

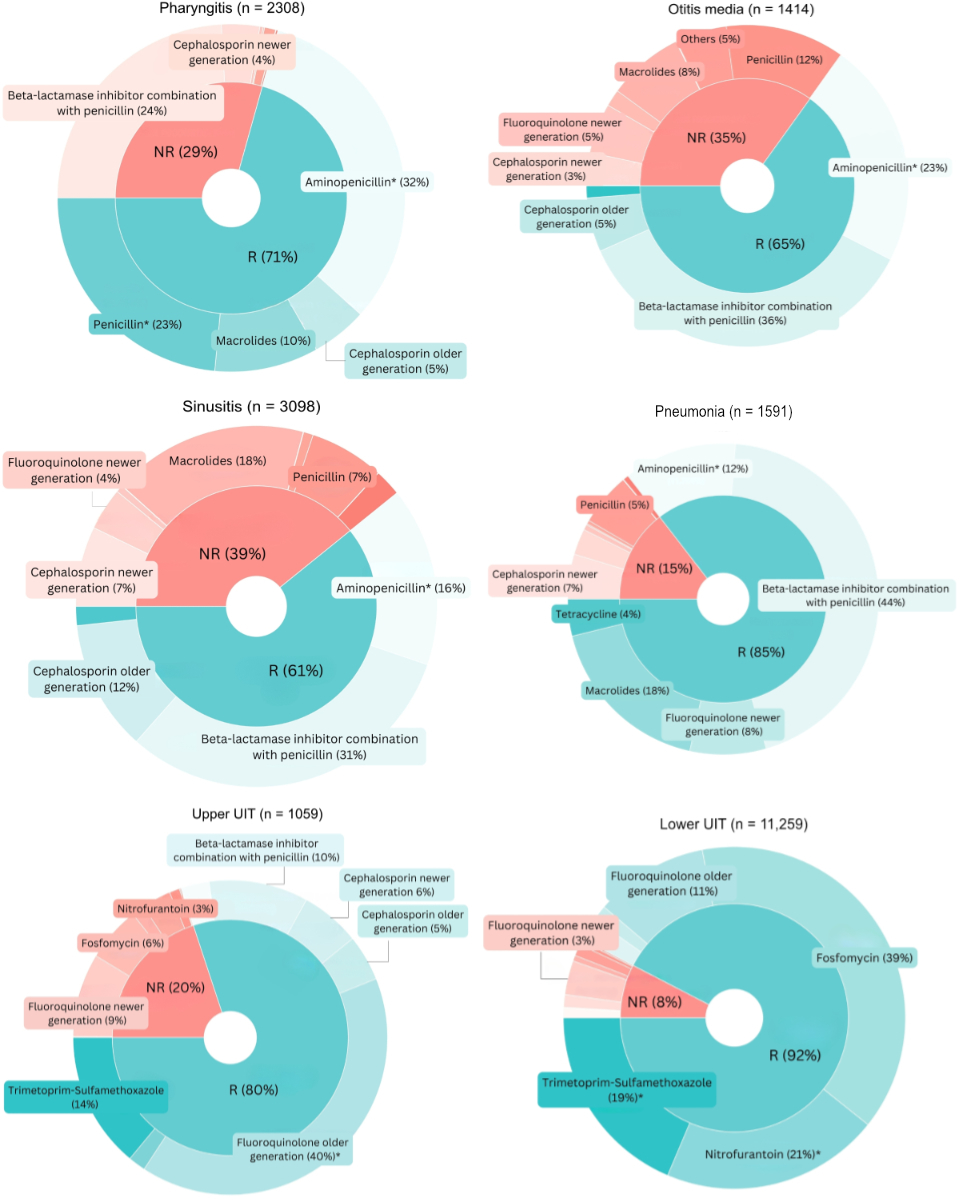

The most common not-recommended antibiotic categories in adults were a beta-lactamase inhibitor in combination with penicillin in case of pharyngitis (24%; n = 556) and a macrolide for sinusitis (18%; n = 543) (figure 3); in children the most common not-recommended antibiotic category was penicillin for pharyngitis (19%; n = 526) (figure 4). Appendix 3 presents the absolute numbers of antibiotic prescriptions for adults and children, along with the distribution of first-line, second-line and not-recommended treatments.

Figure 3Antibiotics by recommendation level by clinical indication in adults. Only indications with more than 1000 observations are displayed. Analyses performed for the period during which guidelines were in place. * First-line treatments according to the guidelines by the Swiss Society of Infectious Diseases (SSI). Antibiotic categories are annotated only if they account for more than 3% of all prescriptions per indication. Entries with missing data (n = 50), specifically related to patient sex, age, clinical indications and antibiotic categories, were excluded from all analyses at the first step of the flowchart, without selective exclusion from specific figures. NR: not recommended; R: recommended.

Figure 4Antibiotics by recommendation level by clinical indication in children. Only indications with more than 1000 observations are displayed. * First-line treatments according to the guidelines by the Swiss Society of Infectious Diseases (SSI). Antibiotic categories are annotated only if they account for more than 3% of all prescriptions per indication. Analyses performed for the period during which guidelines were in place. ** Penicillin is classified as “not-recommended” per current guidelines, which prioritise amoxicillin for its simpler dosing. However, in informal exchanges with this paper’s authors, guideline authors acknowledged penicillin as an acceptable option. Entries with missing data (n = 50), specifically related to patient sex, age, clinical indications and antibiotic categories, were excluded from all analyses at the first step of the flowchart, without selective exclusion from specific figures. NR: not recommended; R: recommended.

There were no statistically significant differences in proportions of not-recommended prescriptions between female and male patients, except for pharyngitis in adults, where the proportion of not-recommended antibiotics was lower in female patients than in male patients (28% vs 32%, p = 0.028) (see table 3).

Table 3Recommendation level by clinical indication and patient sex. Upper and lower urinary tract infections are not present in the table as guidelines were present for female patients only. Analyses performed for the time period during which guidelines were in place.

| Clinical indication | Patient sex | Adults, n = 9056 | Children, n = 9448 | ||||

| Recommended | Not recommended | p value | Recommended | Not recommended | p value | ||

| Pharyngitis | Female | 996 (72.4%) | 380 (27.6%) | 0.028 | 822 (61.7%) | 511 (38.3%) | 0.587 |

| Male | 635 (68.1%) | 297 (31.9%) | 908 (62.7%) | 541 (37.3%) | |||

| Sinusitis | Female | 1242 (61.5%) | 776 (38.5%) | 0.254 | 78 (96.3%) | 3 (3.7%) | 0.322 |

| Male | 642 (59.4%) | 438 (40.6%) | 77 (92.8%) | 6 (7.2%) | |||

| Otitis media | Female | 512 (66.1%) | 263 (33.9%) | 0.385 | 2562 (89.6%) | 296 (10.4%) | 0.165 |

| Male | 408 (63.8%) | 231 (36.2%) | 2927 (88.5%) | 379 (11.5%) | |||

| Pneumonia | Female | 654 (83.8%) | 126 (16.2%) | 0.070 | 137 (84.0%) | 26 (16.0%) | 0.569 |

| Male | 706 (87.1%) | 105 (12.9%) | 143 (81.7%) | 32 (18.3%) | |||

| COPD exacerbation | Female | 215 (70.3%) | 91 (29.7%) | 0.078 | NA | NA | NA |

| Male | 216 (63.7%) | 123 (36.3%) | |||||

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

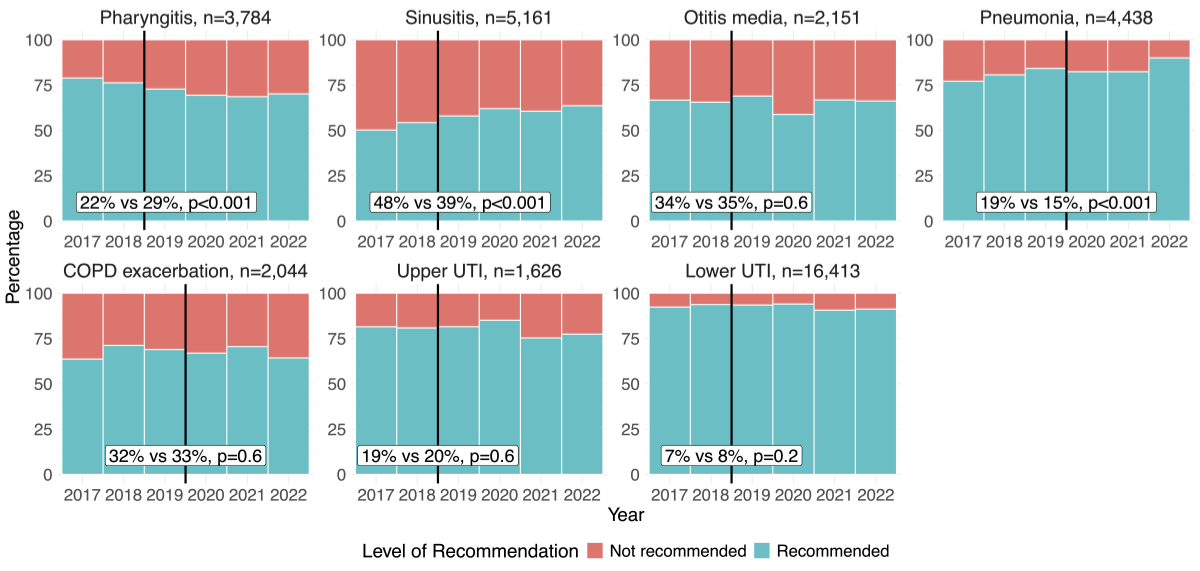

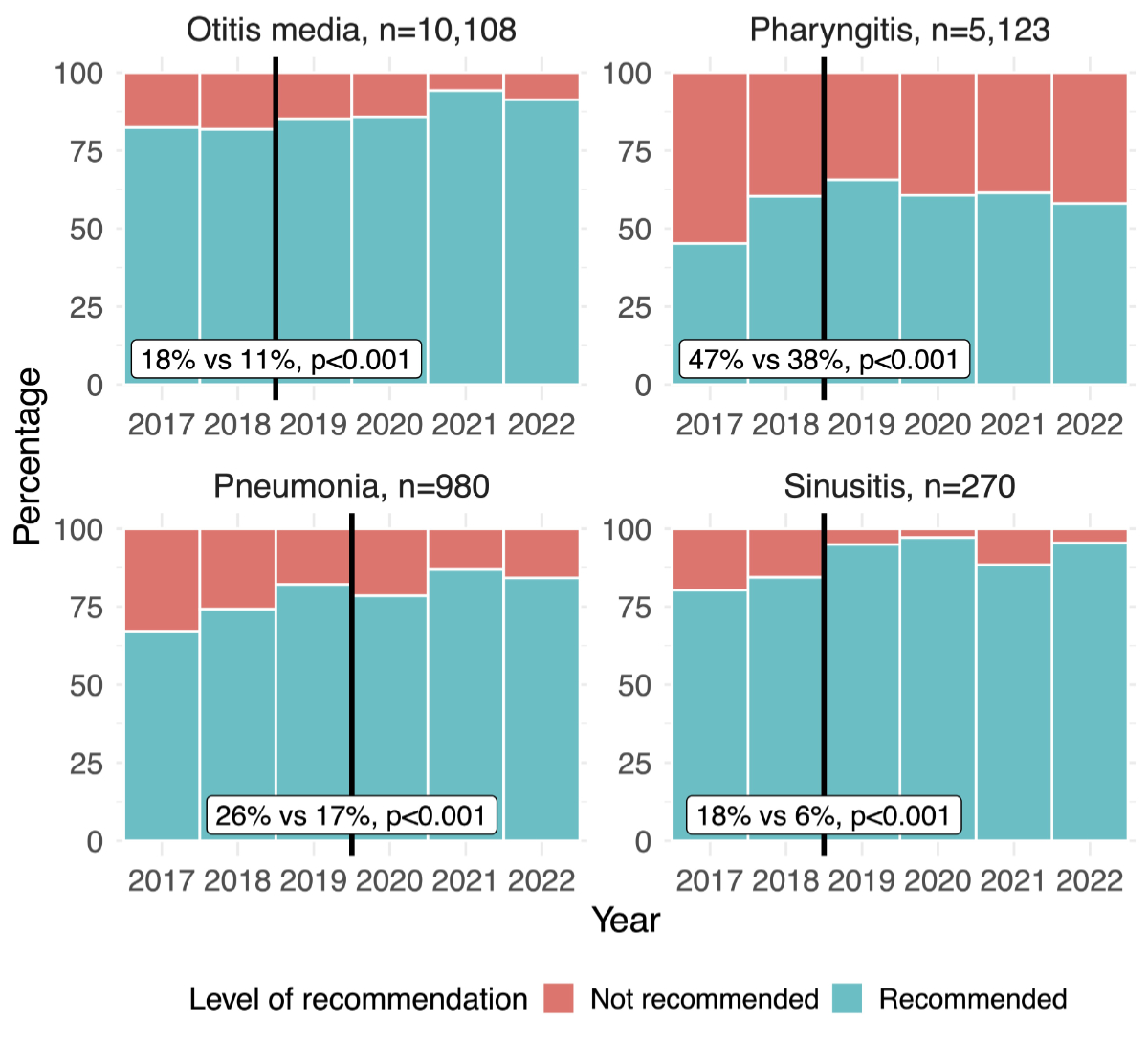

In adults there was a significant decrease in the proportion of not-recommended antibiotic category from before to after guideline implementation for sinusitis (48% vs 39%, p <0.001) and pneumonia (19% vs 15%, p <0.001), while for pharyngitis the proportion increased after the guideline implementation (22% vs 29%, p <0.001, see figure 5 and appendix 4). In children, for all the included indications, there was a significant decrease in the proportion of not-recommended antibiotic category from before to after guideline implementation, with the most marked decrease for pharyngitis (47% vs 38%, p <0.001, see figure 6 and appendix 4).

Figure 5Change in proportions of recommended and not-recommended antibiotic prescriptions before and after the introduction of the guidelines over years in adults by indication. Black vertical lines show the year of introduction of guideline. The percentages in the white boxes denote the proportion of not-recommended antibiotics prescribed before (left) and after (right) the guideline implementation, p-values reflect the significance of changes in adherence over time, calculated for each clinical indication using a Chi-squared test. Entries with missing data (n = 50), specifically related to patient sex, age, clinical indications and antibiotic categories, were excluded from all analyses at the first step of the flowchart, without selective exclusion from specific figures. COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; UTI: urinary tract infection.

Figure 6Change in proportion of recommended and not-recommended antibiotic prescriptions before and after the introduction of the guidelines over years in children by indication. Black vertical lines show the year of introduction of guideline. The percentages in the white boxes denote the proportion of not-recommended antibiotics prescribed before (left) and after (right) the guideline implementation, p-values reflect the significance of changes in adherence over time, calculated for each clinical indication using a Chi-squared test. Entries with missing data (n = 50), specifically related to patient sex, age, clinical indications and antibiotic categories, were excluded from all analyses at the first step of the flowchart, without selective exclusion from specific figures.

Results of univariate logistic regression analyses are presented in table 3. Multilevel logistic regression analysis (see table 4) revealed that among physicians, older age was associated with higher odds of prescribing not-recommended antibiotics (OR: 2.91, 95% CI: 1.35–6.27, p = 0.006, reference: age group 31–45 years), while being a paediatrician was associated with lower odds (OR: 0.53, 95% CI: 0.29–0.96, p = 0.036, reference: general internal medicine specialist). Among patients, higher odds of being prescribed not-recommended antibiotics were associated with indications such as pharyngitis (OR: 3.15, 95% CI: 2.81–3.53, p <0.001, reference: otitis) and sinusitis (OR: 2.91, 95% CI: 2.52–3.36, p <0.001, reference: otitis), favourable patient attitudes towards antibiotic prescriptions perceived by physician (OR: 1.22, 95% CI: 1.05–1.43, p = 0.012, reference: neutral patient attitude) and all the age groups compared to the reference group 16–45 years. Consultation years 2020–2022 compared with year 2019 were associated with lower odds of prescribing a not-recommended antibiotic. The intraclass correlation coefficient for the model was 0.32 (95% CI: 0.26–0.37).

Table 4Factors associated with prescribing of not-recommended antibiotics. Exclusions due to missing data: 349 observations were excluded due to missing physician age category, 63 observations were excluded due to missing patient attitude. Prescription of not-recommended antibiotic: number of observations = 17,447; number of physicians (or group practices) = 189

| Factor | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Specialty (reference: general internal medicine) | Paediatrician | 0.47 | 0.44–0.50 | <0.001 | 0.53 | 0.29–0.96 | 0.036 |

| Physician age category (reference: 31–45 years) | 46–65 years | 1.66 | 1.50–1.83 | <0.001 | 1.65 | 1.00–2.72 | 0.052 |

| ≥66 years | 4.11 | 3.59–4.71 | <0.001 | 2.91 | 1.35–6.27 | 0.006 | |

| Physician sex (reference: female) | Male | 1.73 | 1.58–1.90 | <0.001 | 0.99 | 0.62–1.58 | 0.968 |

| Mixed | 0.79 | 0.69–0.90 | <0.001 | 1.15 | 0.48–2.76 | 0.748 | |

| Practice type (reference: group practice) | Solo practice | 2.05 | 1.91–2.20 | <0.001 | 1.48 | 1.00–2.20 | 0.052 |

| Urban-rural typology (reference: intermediate) | Rural | 2.70 | 2.38–3.08 | <0.001 | 1.51 | 0.66–3.45 | 0.325 |

| Urban | 1.11 | 1.01–1.23 | 0.028 | 1.35 | 0.76–2.40 | 0.311 | |

| Linguistic region (reference: French) | German | 1.77 | 1.63–1.93 | <0.001 | 0.90 | 0.55–1.49 | 0.683 |

| Italian | 0.94 | 0.81–1.09 | 0.4 | 1.02 | 0.45–2.29 | 0.960 | |

| Consultation year (reference: 2019) | 2020 | 0.98 | 0.89–1.07 | 0.7 | 0.85 | 0.75–0.96 | 0.011 |

| 2021 | 0.69 | 0.62–0.77 | <0.001 | 0.85 | 0.74–0.97 | 0.019 | |

| 2022 | 0.76 | 0.69–0.83 | <0.001 | 0.69 | 0.61–0.79 | <0.001 | |

| Patient age group (reference: 16–45 years) | ≤15 years | 1.86 | 1.71–2.02 | <0.001 | 1.34 | 1.11–1.61 | 0.002 |

| 46–65 years | 2.42 | 2.18–2.68 | <0.001 | 1.55 | 1.35–1.77 | <0.001 | |

| ≥66 years | 1.45 | 1.27–1.64 | <0.001 | 1.37 | 1.15–1.64 | <0.001 | |

| Patient sex (reference: female) | Male | 0.93 | 0.81–1.00 | 0.039 | 1.02 | 0.93–1.11 | 0.662 |

| Clinical indication (reference: otitis) | Pharyngitis | 2.77 | 2.55–3.02 | <0.001 | 3.15 | 2.81–3.53 | <0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 0.95 | 0.82–1.10 | 0.5 | 0.77 | 0.63–0.94 | 0.009 | |

| Sinusitis | 3.20 | 2.91–3.52 | <0.001 | 2.91 | 2.52–3.36 | <0.001 | |

| Physician-reported patient attitude towards prescription (reference: neutral) | Unfavourable | 0.63 | 0.46–0.85 | 0.003 | 0.85 | 0.59–1.21 | 0.365 |

| Favourable | 1.43 | 1.28–1.60 | <0.001 | 1.22 | 1.05–1.43 | 0.012 | |

* Model fit: ROC AUC = 0.865; deviance test: chi-squared = 768.64, df = 22, p <0.001 (supports statistical superiority of our model compared to null model); overall accuracy: 82.8%

AUC: area under the curve; CI: confidence interval; df: degrees of freedom; ICC: intraclass correlation coefficient; OR: odds ratio; ROC: Receiver Operating Characteristic.

This cross-sectional study using antibiotic prescription data from physicians and paediatricians of the Sentinella surveillance network demonstrates that for several indications there is a high level of non-adherence to guidelines. Introduction of guidelines did not lead to a meaningful increase in prescribing of recommended antibiotics to adults.

The proportion of not-recommended antibiotics was higher for respiratory tract infections than for urinary tract infections, consistent with findings from other studies [10, 25]. When comparing our results to a nationwide Swiss survey of family physicians with high prescription rates from 2015 [25], which used European Surveillance of Antimicrobial consumption (ESAC) disease-specific quality indicators to define not-recommended antibiotic types, our study found lower proportions of not-recommended antibiotics for several clinical indications, such as pharyngitis, sinusitis, pneumonia and urinary tract infection. Several factors may explain this difference. First, Glinz et al. used ESAC indicators to define not-recommended antibiotic types and the survey, which asked physicians to record data on 44 consecutive patients, had questions regarding allergies and comorbidities, allowing for a finer level of analysis. Moreover, the survey was sent to top prescribers of antibiotics, while physicians volunteering to take part in the communicable disease surveillance network Sentinella might be more interested in antimicrobial stewardship and thus prescribe more appropriate antibiotics. Additionally, our study examines physician prescriptions over multiple years, whereas the study by Glinz et al. collected data from 44 consecutive patients due to its survey-based design. This difference in methodology may also help explain variations in the results. The study by Glinz et al. was conducted before the introduction of guidelines. While our findings suggest some improvement in prescribing patterns, they also demonstrate that the mere introduction of guidelines is not enough to ensure optimal antibiotic use. The continued overuse of second-line antibiotics indicates that prescribing decisions remain misaligned with evidence-based recommendations. This highlights the need for sustained antimicrobial stewardship efforts, clearer clinical guidelines and targeted interventions to curb unnecessary second-line antibiotic use and reinforce first-line treatments as the standard of care whenever appropriate.

Our study also found that the proportions of not-recommended antibiotics were lower in children than in adults across all indications. This aligns with other research indicating that the proportion of inappropriate prescribing in children ranges from 16% to 29%, which is lower than in adults [26–28]. For pharyngitis, the second most common indication in children, 38% of antibiotic prescriptions were not-recommended, with penicillin being the most frequently prescribed among them. After consulting the guideline authors, we learned that while penicillin was omitted due to its more complex regimen compared to amoxicillin, it can still be used to treat pharyngitis. Thus, the proportion of not-recommended antibiotics for this indication is indeed high, but not strictly speaking inappropriate.

There are several possible reasons behind low levels of adherence to guidelines. First, unawareness: a survey of Swiss family physicians has shown that only 53% of them report being aware of national guidelines [29]. Moreover, reasons related to guideline usability and access can contribute to their underutilisation, while access to guidelines that is incorporated in the electronic patient file increases their usability [18]. Access to the national guidelines for a particular indication requires navigation through several steps on the guideline website and might be considered too time-consuming by some physicians. Furthermore, the findings of this study, reflected by an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.32 (95% CI: 0.26–0.37) from the multilevel model examining factors associated with the prescribing of not-recommended antibiotics, highlight that a significant proportion of the differences in prescribing practices can be attributed to factors at the physician or practice level. This study also highlights that introduction of guidelines does not automatically result in their usage by physicians and more effective interventions are needed to improve the adherence to the guidelines. Additionally, effective guideline implementation depends on multiple factors beyond awareness alone. Research indicates that adherence improves when guidelines are clear and easy to implement [30]. Integrating clinical decision support systems into electronic health records has been shown to significantly reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing, particularly for broad-spectrum antibiotics in both paediatric and adult patients [31]. Moreover, targeted implementation efforts that include strategies such as educational outreach, reminders and audit feedback have been associated with modest to moderate improvements in adherence [32]. Additionally, primary care physicians should be involved in the development of guidelines to make sure that they are adapted for use in the field [33].

Given the limited patient information reported by Sentinella physicians, we were unable to determine whether antibiotic prescriptions of second-line treatments proposed in case of allergy or comorbidities were justified. In nearly all clinical indications among adult patients, second-line treatments were prescribed more frequently than first-line options. However, the high proportion of second-line prescriptions suggests that factors beyond true penicillin allergy or relevant comorbidities may be influencing prescribing decisions. For example, in the case of pneumonia, approximately a quarter of patients were prescribed either a macrolide or a fluoroquinolone. However, it is highly unlikely that 25% of patients with pneumonia had a true penicillin allergy [34]. These results suggest overuse of the second-line treatment underscoring the need for targeted antimicrobial stewardship efforts to ensure that first-line treatments are prescribed for the majority of patients, reserving second-line options for cases where they are truly necessary. Our findings suggest that current guidelines for certain indications may need to be revisited to better support physicians in making evidence-based prescribing decisions.

Our findings support prior research showing that older physicians tend to prescribe antibiotics inappropriately [19, 35, 36]. Additionally, they validate the link between patient attitudes and higher rates of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions, consistent with studies highlighting the influence of patient expectations on prescribing decisions [18].

It is already known that antibiotic prescribing decreased during the COVID-19 period [37–39]; however, our study reveals that the years 2020–2022 were specifically associated with lower odds of non-adherent antibiotic prescribing. Another study reported an initial decline in inappropriate antibiotic prescribing following the onset of the pandemic, but a gradual return to pre-pandemic levels over time [40]. These findings highlight the complex interplay of physician characteristics, patient factors and contextual factors in antibiotic prescribing practices.

To our knowledge, this is the first study in Switzerland to examine non-adherence to guidelines for antibiotic prescribing in primary care across a wide range of indications.

Our study quantified proportions of not-recommended antibiotic prescriptions across various indications, pinpointing areas for improvement in outpatient antibiotic prescribing. Specifically, indications like sinusitis and pharyngitis in adults showed a notable proportion of not-recommended treatments. We also identified physician and patient factors associated with prescribing of not-recommended antibiotics and identified prevalent second-line and not-recommended treatments for each indication. These insights enable the development of targeted antimicrobial stewardship activities to address these specific challenges effectively. More specifically, these results could be used by national guideline authors to identify key messages for physicians that could be included in the guidelines to enhance adherence to recommendations. Additionally, they could support effective communication during scientific conferences and educational initiatives.

In our study, we focused on prescribing of antibiotics that are not recommended by the guideline for a given indication, as a proxy for inappropriate prescribing. However different studies use different definitions of inappropriate prescribing. For example there are studies that consider inappropriate all treatments that are not first-line [26], as ours, and studies that consider inappropriate treatments for which antibiotics should never be prescribed, for example viral infections [41], making head-to-head comparisons between studies difficult. We may have overestimated guideline-adherent prescriptions, as we included second-line antibiotics under the category of “in accordance with the guidelines”. Sentinella groups cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones into “older” and “newer” categories instead of using numbered generations, making it impossible to distinguish between different generations. As a result, our analysis is less detailed than it would have been if numbered generations were used.

Also, results regarding patients’ attitudes towards antibiotic prescriptions should be interpreted with caution, as these attitudes were perceived by physicians who filled in the questionnaire according to whether they felt the patients or – in case of child patients– their parents were favourable, neutral or unfavourable towards the antibiotic prescription.

For indications like pharyngitis, sinusitis, otitis media and lower urinary tract infection in women where watchful waiting are proposed as the first option, we could not confirm the presence of strict clinical criteria justifying antibiotic use [14]. Until 2023, Sentinella physicians did not report infection episodes in which they do not prescribe antibiotics. Therefore we were not able to determine whether the percentage of patients prescribed an antibiotic for a given indication was acceptable as proposed by ESAC disease-specific quality indicators [42].

We excluded indications without national guidelines, including acute bronchitis (5779 observations) and other upper respiratory tract infections (6531 observations). However other guidelines such as AWARE guidelines supported by WHO do specify that antibiotics should not be prescribed for acute bronchitis [43].

Prescribing of antibiotics by Swiss family physicians and paediatricians is not aligned with national guidelines for several clinical indications, particularly respiratory tract infections. Guideline introduction only resulted in limited improvements in prescribing to adults. Factors such as older physician age and solo practice settings exacerbate these inappropriate prescribing habits. Knowledge gained can be used by decision-makers for targeted antimicrobial stewardship activities, such as improving guideline dissemination or adoption by, for example, optimising their format to better align with needs of physicians.

The data was provided by the Federal Office of Public Health and cannot be shared by the authors. Given that the data used in this analysis was provided by the Federal Office of Public Health and is subject to strict confidentiality agreements, we regret that we are unable to share the full analytical code. However, we are committed to transparency and open science to the extent possible. Upon request, we can provide isolated, generalised snippets of the code used for specific analyses or visualisations. If needed, these can help replicate similar analyses with alternative datasets.

Lecture at the 8th Annual Spring Congress of the Swiss Society of General Internal Medicine 2024, Basel, Switzerland and poster presentation at the Swiss Public Health Conference 2024, Fribourg, Switzerland.

The authors extend their gratitude to the Federal Office of Public Health and the Sentinella Surveillance Network.

Data was provided by the Federal Office of Public Health (Switzerland).

Financial support: Collège de médecine de premier recours grant (Switzerland), Federal Office of Public Health (Switzerland), Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 212429).

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript was disclosed.

1. EClinicalMedicine. Antimicrobial resistance: a top ten global public health threat. EClinicalMedicine. 2021 Nov;41:101221. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101221

2. Smith DR, Dolk FC, Pouwels KB, Christie M, Robotham JV, Smieszek T. Defining the appropriateness and inappropriateness of antibiotic prescribing in primary care. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018 Feb;73 suppl_2:ii11–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkx503

3. WHO policy guidance on integrated antimicrobial stewardship activities. World Health Organization. 2021.

4. Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. World Health Organization. 2015.

5. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial consumption in the EU/EEA (ESAC-Net) - Annual Epidemiological Report 2022. Stockholm: ECDC; 2023.

6. UK Health Security Agency. English surveillance programme for antimicrobial utilisation and resistance (ESPAUR) Report 2022 to 2023. London: UK Health Security Agency, November 2023. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/english-surveillance-programme-antimicrobialutilisation-and-resistance-espaur-report

7. Federal Office of Public Health and Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office. Swiss Antibiotic Resistance Report 2024. Usage of Antibiotics and Occurrence of Antibiotic Resistance in Switzerland. November 2024. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/das-bag/aktuell/news/news-18-11-2024.html

8. Akkerman AE, Kuyvenhoven MM, van der Wouden JC, Verheij TJ. Determinants of antibiotic overprescribing in respiratory tract infections in general practice. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005 Nov;56(5):930–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dki283

9. Peñalva G, Fernández-Urrusuno R, Turmo JM, Hernández-Soto R, Pajares I, Carrión L, et al.; PIRASOA-FIS team. Long-term impact of an educational antimicrobial stewardship programme in primary care on infections caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in the community: an interrupted time-series analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Feb;20(2):199–207. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30573-0

10. Debets VE, Verheij TJ, van der Velden AW; SWAB’s Working Group on Surveillance of Antimicrobial Use. Antibiotic prescribing during office hours and out-of-hours: a comparison of quality and quantity in primary care in the Netherlands. Br J Gen Pract. 2017 Mar;67(656):e178–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp17X689641

11. Hek K, van Esch TE, Lambooij A, Weesie YM, van Dijk L. Guideline adherence in antibiotic prescribing to patients with respiratory diseases in primary care: prevalence and practice variation. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020 Sep;9(9):571. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics9090571

12. Nowakowska M, van Staa T, Mölter A, Ashcroft DM, Tsang JY, White A, et al. Antibiotic choice in UK general practice: rates and drivers of potentially inappropriate antibiotic prescribing. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019 Nov;74(11):3371–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkz345

13. A Plate, S Di Gangi, S Neuner-Jehle, O Senn. Antibiotic Prescription Patterns in Swiss Primary Care (2012 to 2019) using electronic medical records. Textbox. Federal Office of Public Health and Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office. Swiss Antibiotic Resistance Report 2022. Usage of Antibiotics and Occurrence of Antibiotic Resistance in Switzerland. November 2022.

14. Guidelines. Swiss Society for Infectious Diseases. Available from: https://ssi.guidelines.ch/

15. Grigoryan L, Burgerhof JG, Degener JE, Deschepper R, Lundborg CS, Monnet DL, et al.; Self-Medication with Antibiotics and Resistance (SAR) Consortium. Determinants of self-medication with antibiotics in Europe: the impact of beliefs, country wealth and the healthcare system. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008 May;61(5):1172–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkn054

16. Silverman M, Povitz M, Sontrop JM, Li L, Richard L, Cejic S, et al. Antibiotic prescribing for nonbacterial acute upper respiratory infections in elderly persons. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Jun;166(11):765–74. doi: https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-1131

17. Fletcher-Lartey S, Yee M, Gaarslev C, Khan R. Why do general practitioners prescribe antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections to meet patient expectations: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open. 2016 Oct;6(10):e012244. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012244

18. Sijbom M, Büchner FL, Saadah NH, Numans ME, de Boer MG. Determinants of inappropriate antibiotic prescription in primary care in developed countries with general practitioners as gatekeepers: a systematic review and construction of a framework. BMJ Open. 2023 May;13(5):e065006. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065006

19. Cadieux G, Tamblyn R, Dauphinee D, Libman M. Predictors of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing among primary care physicians. CMAJ. 2007 Oct;177(8):877–83. doi: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.070151

20. O’Doherty J, Leader LF, O’Regan A, Dunne C, Puthoopparambil SJ, O’Connor R. Over prescribing of antibiotics for acute respiratory tract infections; a qualitative study to explore Irish general practitioners’ perspectives. BMC Fam Pract. 2019 Feb;20(1):27. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-019-0917-8

21. Le système de déclaration Sentinella. Federal Office of Public Health. 2018. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/fr/home/krankheiten/infektionskrankheiten-bekaempfen/meldesysteme-infektionskrankheiten/sentinella-meldesystem.html

22. Excoffier S, Herzig L, N’Goran AA, Déruaz-Luyet A, Haller DM. Prevalence of multimorbidity in general practice: a cross-sectional study within the Swiss Sentinel Surveillance System (Sentinella). BMJ Open. 2018 Mar;8(3):e019616. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019616

23. R Core Team. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL: https://www.R-project.org/

24. Canva. Canva – Online design tool. Sydney, Australia: Canva Pty Ltd.; 2024. Available from: https://www.canva.com

25. Glinz D, Leon Reyes S, Saccilotto R, Widmer AF, Zeller A, Bucher HC, et al. Quality of antibiotic prescribing of Swiss primary care physicians with high prescription rates: a nationwide survey. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017 Nov;72(11):3205–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkx278

26. Butler AM, Brown DS, Durkin MJ, Sahrmann JM, Nickel KB, O’Neil CA, et al. Association of inappropriate outpatient pediatric antibiotic prescriptions with adverse drug events and health care expenditures. JAMA network open. 2022;5(5):e2214153-e. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.14153

27. Wattles BA, Smith MJ, Feygin Y, Jawad K, Flinchum A, Corley B, et al., editors. Inappropriate Prescribing of Antibiotics to Pediatric Patients Receiving Medicaid: Comparison of High-Volume and Non-High-Volume Antibiotic Prescribers – Kentucky, 2019. Healthcare. MDPI; 2023.

28. Dekker AR, Verheij TJ, van der Velden AW. Inappropriate antibiotic prescription for respiratory tract indications: most prominent in adult patients. Fam Pract. 2015 Aug;32(4):401–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmv019

29. Schaad S, Dunaiceva J, Peytremann A, Gendolla S, Clack L, Plüss-Suard C, et al. Perception of antimicrobial stewardship interventions in Swiss primary care: a mixed-methods survey. BJGP Open. 2025;BJGPO.2024.0110. doi: https://doi.org/10.3399/BJGPO.2024.0110

30. Francke AL, Smit MC, de Veer AJ, Mistiaen P. Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals: a systematic meta-review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2008 Sep;8(1):38. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-8-38

31. Mainous AG 3rd, Lambourne CA, Nietert PJ. Impact of a clinical decision support system on antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infections in primary care: quasi-experimental trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(2):317–24. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000701

32. Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004 Feb;8(6):iii–iv. doi: https://doi.org/10.3310/hta8060

33. Han L, Zeng L, Duan Y, Chen K, Yu J, Li H, et al. Improving the applicability and feasibility of clinical practice guidelines in primary care: recommendations for guideline development and implementation. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021 Aug;14:3473–82. doi: https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S311254

34. Luintel A, Healy J, Blank M, Luintel A, Dryden S, Das A, et al. The global prevalence of reported penicillin allergy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2025 Feb;90(2):106429. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2025.106429

35. Fernandez-Lazaro CI, Brown KA, Langford BJ, Daneman N, Garber G, Schwartz KL. Late-career physicians prescribe longer courses of antibiotics. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 Oct;69(9):1467–75. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy1130

36. Li C, Cui Z, Wei D, Zhang Q, Yang J, Wang W, et al. Trends and Patterns of Antibiotic Prescriptions in Primary Care Institutions in Southwest China, 2017-2022. Infect Drug Resist. 2023 Sep;16:5833–54. doi: https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S425787

37. Federal Office of Public Health and Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office. Swiss Antibiotic Resistance Report 2022. Usage of Antibiotics and Occurrence of Antibiotic Resistance in Switzerland. November 2022.

38. King LM, Lovegrove MC, Shehab N, Tsay S, Budnitz DS, Geller AI, et al. Trends in US outpatient antibiotic prescriptions during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 Aug;73(3):e652–60. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1896

39. Plüss-Suard C, Friedli O, Labutin A, Gasser M, Mueller Y, Kronenberg A. Post-pandemic consumption of outpatient antibiotics in Switzerland up to pre-pandemic levels, 2018–2023: an interrupted time series analysis. CMI Communications. 2024;1(2):105037. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmicom.2024.105037

40. Chua KP, Fischer MA, Rahman M, Linder JA. Changes in the Appropriateness of US Outpatient Antibiotic Prescribing After the COVID-19 Outbreak: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis of 2016-2021 Data. Clin Infect Dis. 2024 Aug;79(2):312–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciae135

41. Wattles BA, Jawad KS, Feygin Y, Kong M, Vidwan NK, Stevenson MD, et al. Inappropriate outpatient antibiotic use in children insured by Kentucky Medicaid. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2022 May;43(5):582–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2021.177

42. Adriaenssens N, Coenen S, Tonkin-Crine S, Verheij TJ, Little P, Goossens H; The ESAC Project Group. European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption (ESAC): disease-specific quality indicators for outpatient antibiotic prescribing. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011 Sep;20(9):764–72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs.2010.049049

43. Web Annex. Infographics. In: The WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) antibiotic book. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022 (WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2022.02). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

The appendix is available in the pdf version of the article at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4234.