Swiss caesarean section rates according to Robson’s Ten-Group Classification System:

an observational study

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/4231

Stephen Adjahoua,

Gian-Paolo Klinkeb,

Alexandre Valléec,

Benedetta Guania,

Nordine Ben Alia,

Jean-Marc Ayoubic,

Anis Fekia,

Arrigo Fruscalzoa

a Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hospital of Fribourg,

Switzerland

b Federal Statistical Office OFS, Switzerland

c Epidemiology unit and public health, Foch Hospital, Suresnes, France

Summary

STUDY

AIMS: Robson’s Ten-Group Classification System (TGCS) was proposed to describe caesarean

section rates by ten patient-centred risk-specific groups. The aim of the study

was to describe Swiss caesarean section rates according to this classification,

further stratifying it according to region and type of structure where delivery

took place. We also aimed to compare our

results to the standard caesarean section rates, recommended by the World

Health Organization (WHO).

METHODS:

An observational study including all women delivering in health facilities in

Switzerland in the period 2014–2021. A total of 695,733 deliveries were

included. Core variables used for classification were semi-automatically

generated using routine data provided by the Swiss Federal Statistics Office. Caesarean

section rates were reported according to the TGCS. Data were also stratified

according to each of the 26 Swiss cantons, as well as to the typology of

hospital where delivery took place.

RESULTS:

The major relative contributors to the overall caesarean section rate were Group

2 (nulliparous, above 37 weeks, with induction) and Group 5 (women with

previous caesarean section, above 37 weeks with a singleton pregnancy),

respectively accounting for 20.7% and 30.1% of all caesarean sections. We also

showed that the Swiss population was similar to the population considered in the

WHO recommendation. Nonetheless, the caesarean section rate among our

population exceeded that suggested by the WHO recommendations, being respectively

of 44.4% vs 39.9% and 86.0% vs 74.4% for Groups 2 and 5. Large variations were

detected in the caesarean section rate when looking at the different cantons,

ranging from 29.8% to 59.6% for Group 2 and between 58.0% and 100.0% for Group 5.

CONCLUSION:

Routine data collection allowed us to describe caesarean section rates throughout

Switzerland according to the TGCS. The Swiss caesarean section rate was higher than

the caesarean section rate recommended by the WHO, even though the population

characteristics were comparable. Substantial differences were found when

stratifying caesarean section rates according to the canton, as well as to the

type of structure where delivery took place.

Introduction

Caesarean

section is one of the most frequently performed surgeries [1]. However,

its use increases maternal morbidity, due to surgery complications, and health costs

[2].

Furthermore, we know that the first caesarean section will determine the

obstetric life of the parturient and increase the need for a caesarean section

in the future [3]. With the

industrialisation of healthcare, the rate of caesareans has exploded and become

a global epidemic. In the United States, the rate of caesarean sections rose

from 5.8% to 31.9% between 1970 and 2016, becoming the most frequently performed

surgical procedure [4]. A

smaller country such as Switzerland is not spared by this global epidemic. In

2021, our country had a caesarean section rate of 32.8% [5].

Analysing the overall caesarean rate

can be misleading due to the diverse risk profiles within the population. To

facilitate comparative assessments, it is crucial to break down this rate into

risk-specific groups. The Ten-Group Classification System (TGCS), introduced by

Michael Robson in 2001, offers a clinically relevant framework for evaluating

variations in the caesarean rate [6, 7].

Endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO) for comparing caesarean

rates between hospitals, the TGCS is increasingly used for cross-unit and

cross-country rate comparisons, as well as for tracking trends over time [8]. This

classification system categorises women into ten distinct, non-overlapping

groups.

In

1985, the WHO stated that a caesarean section rate higher than 15% could not be

medically justified. In 2015, it recommended use of the TGCS when assessing the

proper use of caesarean sections [8]. Assessing

singleton pregnancies through the lens of the TGCS may lead to better-targeted

interventions and thus decrease the caesarean section rate for deliveries with lower

risks [9].

With

a multicounty survey on maternal and newborn health, the

WHO constituted a reference population from 66 health facilities in 22

countries (the WHO MCS population). Based on this population, a target caesarean

section rate has been proposed by the WHO for each TGCS group [10]. However,

it is questionable whether the population of the included countries could be

compared to that of a high-income country, like Switzerland – calling into question

the target caesarean section rate proposed by the WHO.

The

aim of the present study was to provide a statistical description of caesarean

sections performed in Switzerland in the last decade according to Robson’s TGCS.

We also provided a comparison between the WHO recommended caesarean section

rate and the caesarean section rate of our study and a

comparison between the main characteristics of the reference population and the

population of our study.

Methods

Study design and setting

This

was a retrospective ecological study carried out in cooperation with the Swiss

Federal Statistical Office. The study was approved by the local ethics

committee (Commission cantonale d’étique

de la recherche sur l’être humain, CER-VD, ID-number 2021-01639, 12 October

2021).

Participants

All

women who gave birth in an acute care hospital from January 2014 to December 2021

in Switzerland, starting from the 24th week of gestation, were

included. Home births, stillbirths and pregnancy terminations were excluded

from the analysis.

Data sources

The

Swiss Federal Statistical Office annually collects the diagnoses of discharges

for deliveries that occurred in Swiss hospitals and birth centres. For the

present study, we used this administrative data source for the period 2014 to

2021. Personal insurance numbers were used for this scope. All deliveries

associated with viable newborns that occurred in Switzerland in an inpatient

setting are thus covered. All the data were transmitted and analysed in anonymised

form. The statistical analysis was performed using the STATA-17 software

package.

Outcome measures

The

primary outcome was the cumulative rate of caesarean sections according to Robson’s

Ten-Group Classification System (table 1). The main features of this

classification are that it is fully inclusive and mutually exclusive [6]. To allocate

each delivery to a group, we used the number of previous births, the number of

fetuses during the pregnancy, the fetal presentation, weeks of amenorrhoea at

birth, the presence of a previous uterine scar, the type of labour (spontaneous

or induced) and of delivery (caesarean section or vaginal). This information was

identified by means of procedures and diagnostic information associated with

each discharge, codified respectively with the Swiss classification of surgical

procedures (CHOP) and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases,

10th revision German Modification (ICD-10-GM) codes. To evaluate caesarean

section rates according to the TGCS, we used the algorithm described in the WHO’s

implementation manual [10]. A

semi-automated classification of the category was performed, as suggested by

the WHO guidelines [10]. Data

were presented as suggested by the WHO guidelines. First, a quality control

verification process was performed in order to assess the plausibility of the

data used for classification. Then our population was classed and compared to

the WHO multicountry survey population (WHO MCS) [10]. Finally,

we looked at our caesarean section rate by category. Furthermore, we stratified

the caesarean section rate for each canton, and type of hospital (university

hospitals or other type).

Table 1The caesarean

section classification, according to Robson’s Ten-Group Classification System

(adapted from reference [10]).

| Group

|

Description

|

| 1 |

Nulliparous,

singleton, cephalic, ≥37 weeks, in spontaneous labour |

| 2 |

Nulliparous,

singleton, cephalic, ≥37 weeks, induced labour or pre-labour caesarean |

| 3 |

Multiparous,

without previous caesarean section, singleton, cephalic, ≥37 weeks,

spontaneous labour |

| 4 |

Multiparous,

without previous caesarean section, singleton, cephalic, ≥37 weeks, induced

or pre-labour caesarean |

| 5 |

Previous

caesarean section, singleton, cephalic, ≥37 weeks |

| 6 |

Nulliparous,

singleton, breech |

| 7 |

Multiparous,

singleton, breech (including previous caesarean section) |

| 8 |

Multiple

pregnancies (including previous caesarean section) |

| 9 |

Transverse

or oblique lies (including previous caesarean section) |

| 10 |

Preterm,

singleton, cephalic, <37 weeks (including previous caesarean section) |

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the study population are

presented using means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables,

and counts and proportions for categorical variables. All data

transmitted by the Federal Statistical Office were processed using Stata V17.

Results

The

present study covers a total of 695,733 deliveries occurring in Switzerland

during the study period 2014–2021. We were able to classify 682,680 deliveries

according to the TGCS, accounting for 98.1% of all deliveries.

Among

these, 224,969 corresponded to caesarean section deliveries (33.0% of all

deliveries) and 457,711 corresponded to vaginal births (67.1% of all

deliveries). The mean maternal age over the full period was 31.7 years. The

gravidity and parity were, respectively, 1.0 and 0.7. Women with a previous uterine

scar accounted for 13.8% of the whole population. The characteristics of

the study population are summarised in table 2.

Table 2Maternal and

pregnancy characteristics of the study populations.

| Characteristic |

Overall |

Caesarean section |

Vaginal birth |

| Maternal characteristics: Mean (SD-median) |

Age at

delivery, in years |

31.7 (4.9-32) |

32.6 (5.0-33) |

31.2 (4.8-31) |

| Age at

first child, in years |

30.5 (4.9-31) |

31.6 (5.1-32) |

30 (4.7-30) |

| Pregnancy history |

Number of

previous pregnancies |

1(1.2-1) |

1 (1.2-1) |

1 (1.2-1) |

| Number of

previous deliveries |

0.7 (0.9-1) |

0.7 (0.8-0) |

0.7 (0.9-1) |

| Deliveries distribution: absolute

number (percentage) |

| Total deliveries |

|

682,680 (100%) |

224,969 (32.9%) |

457,711 (67.0%) |

| Fetal position |

Vertex |

630,365 (92.3%) |

179,729 (28.5%) |

450,636 (71.5%) |

| Breech |

34,991 (5.1%) |

33,079 (94.5%) |

1912 (5.5%) |

| Transverse |

17,324 (2.5%) |

12,161 (70.0%) |

5163 (29.0%) |

| Pregnancy type |

Singleton |

670,106 (98.1%) |

215,108 (32.1%) |

454,998 (67.9%) |

| Multiple |

12,574 (1.8%) |

9861 (78.4%) |

2713

(21.6%) |

| Uterine

scar* |

94,267 (13.8%) |

82,435 (87.4%%) |

11,832 (12.5%) |

| Labour type |

Spontaneous |

518,640 (76.0%) |

182,692 (35.2%) |

335,948 (64.8%) |

| Induced |

164,040 (24.0%) |

42,277 (25.7%) |

121,763 (74.2%) |

| Gestational age at delivery |

Premature (<37 weeks) |

41,583 (6.1%) |

23,529 (56.6%) |

18,054 (43.4%) |

| At term (≥37 weeks) |

641,097 (93.9%) |

201,440 (31.4%) |

439,657 (68.6%) |

| Macro-region |

German-speaking |

482,907 (70.7%) |

166,320 (34.4%) |

316,587 (65.6%) |

| French- or

Italian-speaking |

199,773 (29.2%) |

58,649 (29.3%) |

141,124 (70.6%) |

| Institutional characteristics: type

of structure** |

University

hospital |

111,197 (16.3%) |

39,521 (35.5%) |

71,676 (64.5%) |

| Centralised

care (university excluded) |

371,574 (54.4%) |

121,603 (32.7%) |

249,971 (67.3%) |

| Primary

care |

184,948 (27.1%) |

62,645 (33.9%) |

122,303 (66.1%) |

| Gynaecological/obstetric

clinic |

14,961 (2.2%) |

1200 (8.0%) |

13,761

(92.0%) |

We also

performed an analysis of the quality of data collected according to the WHO

recommendations (table 3). We evaluated singleton newborns in transverse or

oblique lie (group 9). The group size accounted for 2.4% of all caesarean

sections (it should be less than 1% ideally; it was found to be 0.4% in the WHO MCS

population) while the caesarean section rate in this group

was 68.8% (it should by definition be 100%); it was found to be 88.6% in the WHO

MCS population.

Table 3Quality of data

according to the WHO’s recommendations.

| Steps |

Interpretation

by Robson |

WHO

MCS population |

Our

results |

| The total

numbers of caesarean sections and of women who delivered |

These

numbers should be identical to the total numbers of caesarean sections and of

women who delivered in your hospital |

NA |

Total

live births |

| FSO |

696,691 |

| Our

study |

682,680

(98.0%) |

| Total

caesarean sections |

| FSO |

224,966 |

| Our

study |

224,969 |

| Size of Group

9 |

Should be

less than 1.0% |

0.4% |

2.4% |

| Group 9 caesarean

section rate |

Should be

100% by convention |

88.6% |

68.8% |

Table 4

illustrates our results according to WHO guidelines. The two

major contributors to the overall caesarean section rate are TGCS Groups 5 and 2,

accounting for a relative contribution of 30.1% and 20.7%, respectively,

responsible for 50.8% of the overall caesarean section rate.

Table 4Results according to

the TGCS report table.

| Group |

Number of caesareans

in group |

Number of

women in group |

Group size

(%) |

Group CS

rate (%) |

Absolute

group contribution to overall CS rate (%) |

Relative group

contribution to overall CS rate (%) |

| 1 |

26,834 |

167,323 |

24.5% |

16.0% |

3.9% |

11.9% |

| 2 |

46,544 |

104,862 |

15.4% |

44.4% |

6.8% |

20.7% |

| 3 |

5406 |

173,318 |

25.4% |

3.1% |

0.8% |

2.4% |

| 4 |

13,520 |

67,487 |

9.9% |

20.0% |

2.0% |

6.0% |

| 5 |

67,708 |

78,753 |

11.5% |

86.0% |

9.9% |

30.1% |

| 6 |

19,764 |

20,450 |

3.0% |

96.6% |

2.9% |

8.8% |

| 7 |

10,566 |

11,426 |

1.7% |

92.5% |

1.5% |

4.7% |

| 8 |

9861 |

12,574 |

1.8% |

78.4% |

1.4% |

4.4% |

| 9 |

11,095 |

16,130 |

2.4% |

68.8% |

1.6% |

4.9% |

| 10 |

13,671 |

30,357 |

4.4% |

45.0% |

2.0% |

6.1% |

| Total |

224,969 |

682,680 |

100% |

|

|

100% |

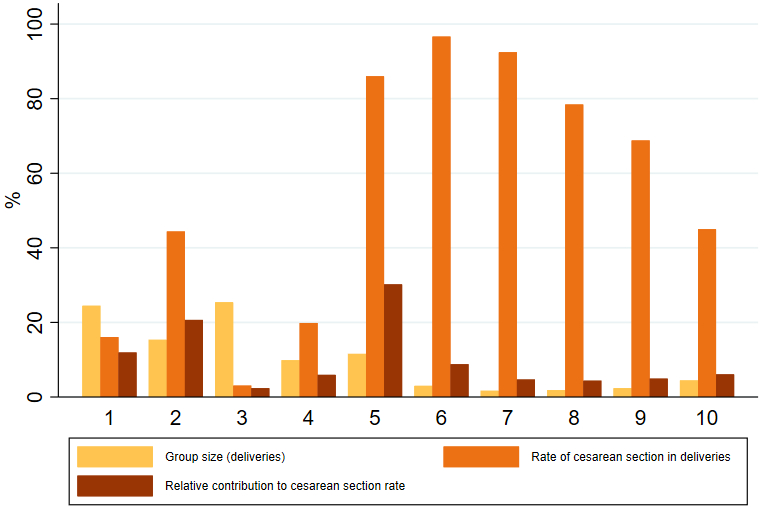

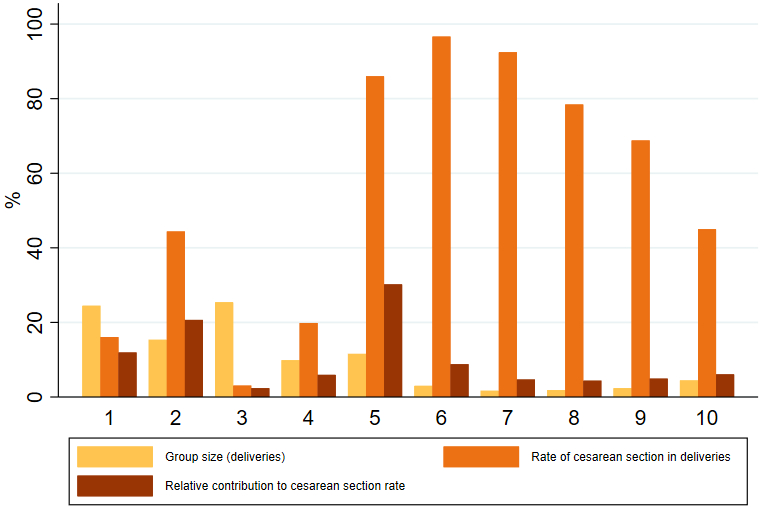

Figure

1 shows the group size, caesarean section rate and relative contribution by TGCS

Group. It reveals that Groups 1 and 3 represented almost half of all our

deliveries. However, the highest caesarean section rate was recorded for the

nulliparous and multiparous breech presentation (Groups 6 and 7, respectively, with

96.6% and 92.5%), followed by Group 5 (previous caesarean section, singleton,

cephalic, ≥37 weeks) then Group 2 (nulliparous, singleton, cephalic, ≥37 weeks,

induced) with a caesarean section rate of 86.0% and 44.4%, respectively.

Considering both the group size and the caesarean section rate, we observe that

the major relative contributors to the overall caesarean section rate were Groups

5 and 2, accounting for 30.1% and 20.7%, respectively, of all caesarean sections.

Figure 1Caesarean

sections in Switzerland between 2014 and 2021, according to Robson’s Ten-Group

Classification System. CS: caesarean section; Group size: The percentage of

patients belonging to the category compared to the overall study population;

Relative contribution of group to overall caesarean section rate: number of caesareans

in the group compared to the overall caesarean sections in the study, as a percentage.

Group 1: Nulliparous, singleton, cephalic, ≥37 weeks in spontaneous labour;

Group 2: Nulliparous, singleton, cephalic, ≥37 weeks, induced or caesarean

section before labour; Group 3: Multiparous (excluding previous caesarean

section), singleton, cephalic, ≥37 weeks in spontaneous labour; Group 4:

Multiparous (excluding previous caesarean section), singleton, cephalic, ≥37

weeks, induced or CS before labour; Group 5: Previous caesarean section,

singleton, cephalic, ≥37 weeks; Group 6: All nulliparous, singleton, breech; Group

7: Multiparous, singleton, breech (including previous caesarean section); Group

8: All multiple births (including previous caesarean section); Group 9: All

singleton, abnormal lie (including previous caesarean section); Group 10: All

singleton, cephalic, ≤36 weeks (including previous caesarean section).

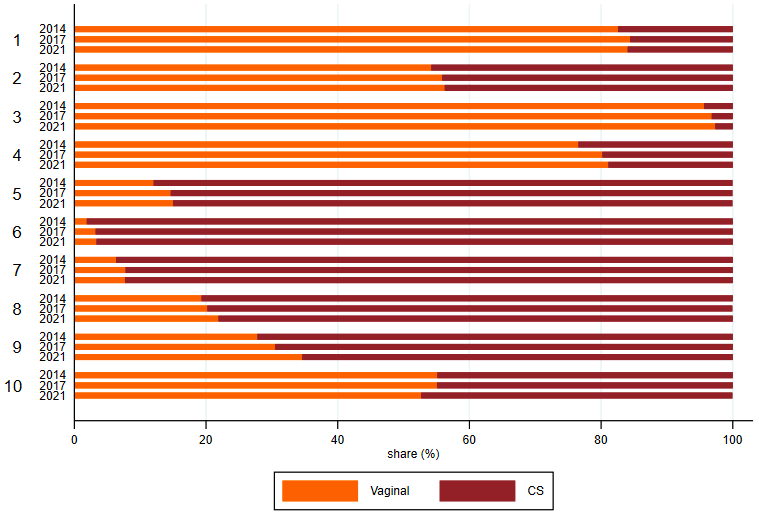

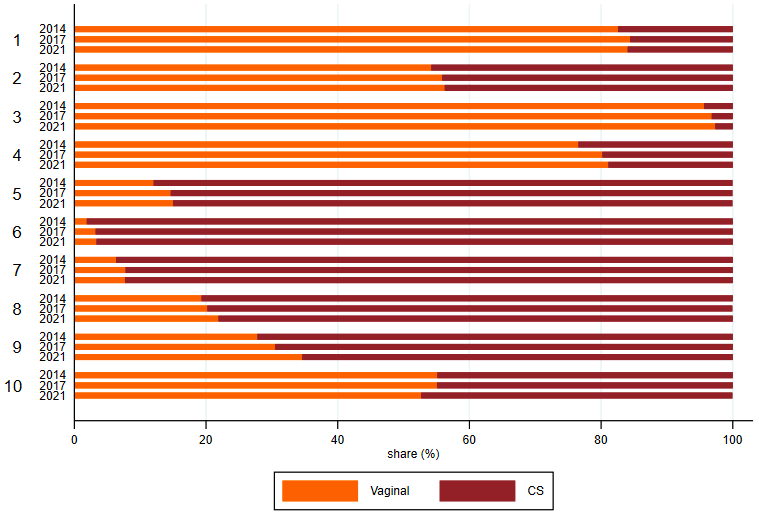

When

evaluating caesarean section trends in our population, we noted a declining

trend in the overall caesarean section rate over the study period. Considering

the ten TGCS Groups, it appears that the caesarean section rate for all Groups has

been decreasing from the year 2014 and 2015 to the year 2021, except for Group 10.

Figure

2 shows the temporal trend in caesarean section rate according to the TGCS.

Figure 2Mode of

delivery by TGCS Groups in 2014, 2015 and 2021.

Table 5

compares our population to the WHO reference population [10]. Our rate of

nulliparous at-term with a cephalic presentation reached 39.9% of the

population, while the rate of multiparous with a cephalic presentation at term

was recorded at 35.3%. The third group in our study consisted of women with a

previous caesarean section, comprising 11.5% of the total. This group also

showed a high induction rate, with a ratio of 1.6 when comparing Groups 1 and

2.

Table 5Characteristics

of the study population compared to the WHO’s reference population.

| Step |

Robson

guideline |

WHO

MCS population |

Our

results (Switzerland) |

| 1. Look at the

size of Groups 1 + 2 (Column 4) |

This

usually represents 35–42% of the obstetric population of most hospitals |

38.1% |

39.9% |

| 2. Look at the

size of

Groups 3 + 4 (Column 4) |

This

usually represents about 30% of women |

46.5% |

35.3% |

| 3. Look at the

size of Group 5 (Column 4) |

This is

related to the overall caesarean section rate. The size of Group 5 is usually

about half of the total caesarean section rate. In settings with low overall caesarean

section rates, it is usually under 10%. |

7.2% |

11.5% |

| 4. Look at the

size of Groups 6 + 7 (Column 4) |

This should

be 3–4% |

2.7% |

4.7% |

| 5. Look at the

size of Group 8 (Column 4) |

This should

be 1.5–2% |

0.9% |

1.8% |

| 6. Look at the

size of Group 10 (Column 4) |

This should

be less than 5% in most normal risk settings |

4.2% |

4.4% |

| 7. Look at the

Ratio of the size of Group 1 vs Group 2 (Divide the size of Group 1 by

the size of Group 2; Column 4) |

This is

usually 2 or higher |

Ratio 3.3 |

1.6 |

| 8. Look at the

Ratio of the size of Group 3 versus Group 4 (Divide the size of Group 3

by the size of Group 4; Column 4) |

This is

always higher than the ratio of Group 1/Group 2 in the same institution, i.e.

larger than 2:1. This is a very reliable finding in confirming data quality

and culture of the organisation. |

2 |

2.6 |

| 9. Look at the

Ratio of the size of Group 6 versus Group 7 (Divide the size of Group 6

by the size of Group 7; Column 4) |

This is

usually 2:1 because breeches are more frequent in nulliparous women than in multiparous

women. |

Ratio 0.8 |

1.8 |

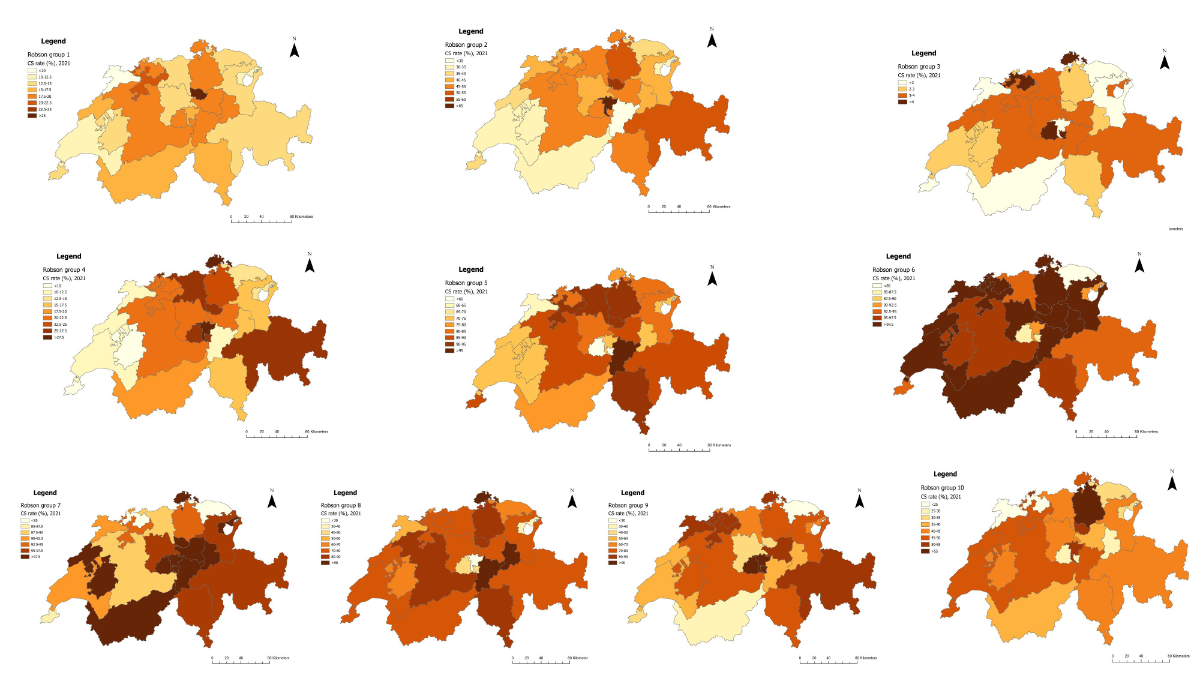

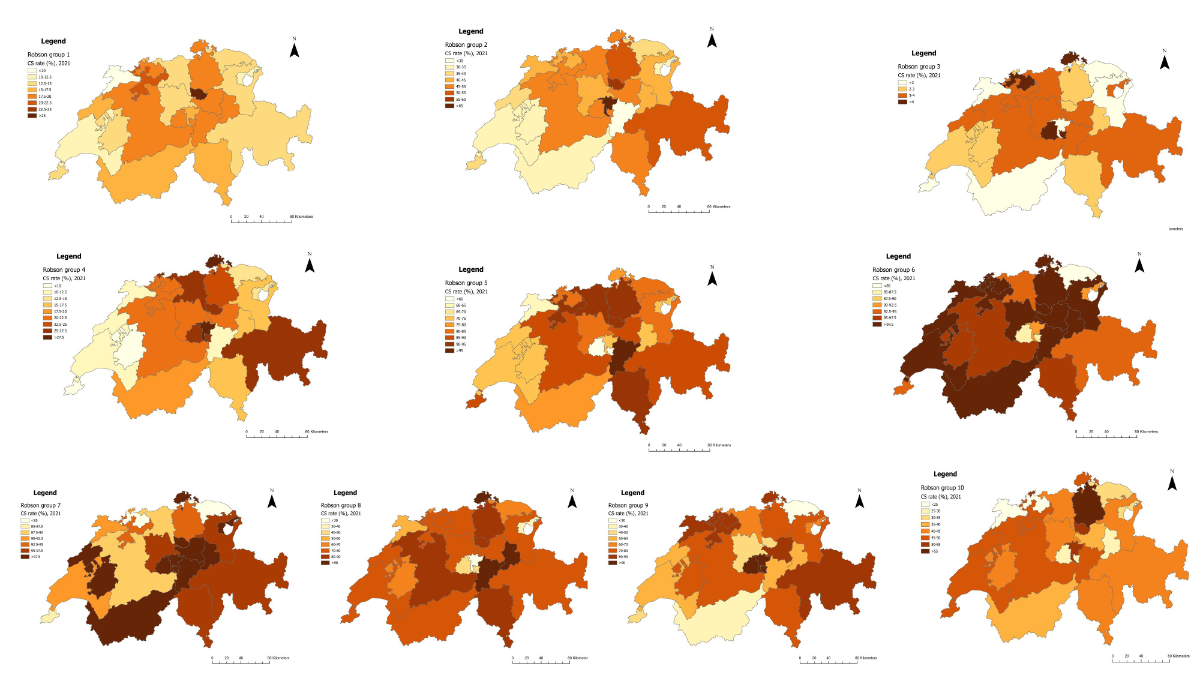

Figure 3 shows the caesarean section rate by TGCS Group in 2021 in the

different regions of Switzerland. These cartographies reveal wide disparities

between different part of our country, especially for the caesarean section

rate for the two main contributors to our overall caesarean section rate, Groups

2 and 5, ranging from 29.8% to 59.6% for Group 2 and between 58.0% and 100% for

Group 5; vs caesarean section rates in Switzerland overall of 44.4% in Group 2 and

86.0% in Group 5.

Figure 3Caesarean

section rate in Switzerland in 2021, according to Robson’s Ten-Group

Classification System. Group 1: Nulliparous, singleton, cephalic,

≥37 weeks in spontaneous labour; Group 2: Nulliparous, singleton, cephalic, ≥37

weeks, induced or caesarean section before labour; Group 3: Multiparous (excluding

previous caesarean section),

singleton, cephalic, ≥37 weeks in spontaneous labour; Group 4: Multiparous (excluding

previous caesarean section),

singleton, cephalic, ≥37 weeks, induced or CS before labour; Group 5: Previous caesarean

section,

singleton, cephalic, ≥37 weeks; Group 6: All nulliparous, singleton, breech; Group

7: Multiparous, singleton, breech (including previous caesarean section);

Group 8: All multiple births (including previous caesarean section);

Group 9: All singleton, abnormal lie (including previous caesarean section);

Group 10: All singleton, cephalic, ≤36 weeks (including previous caesarean section).

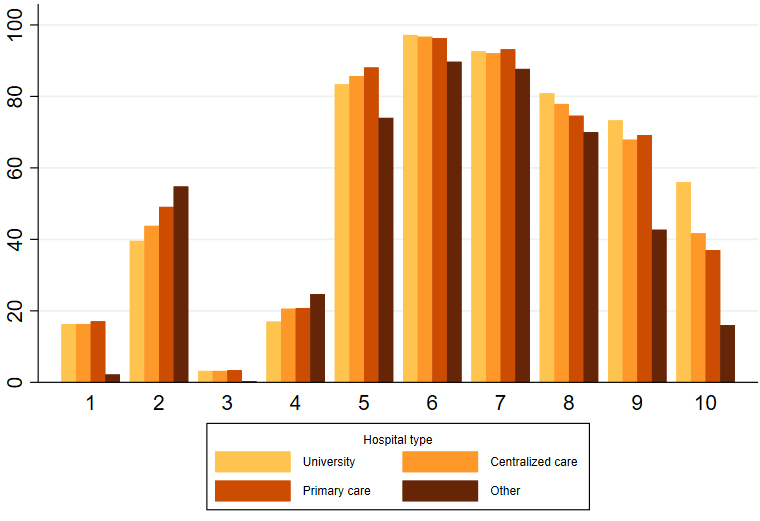

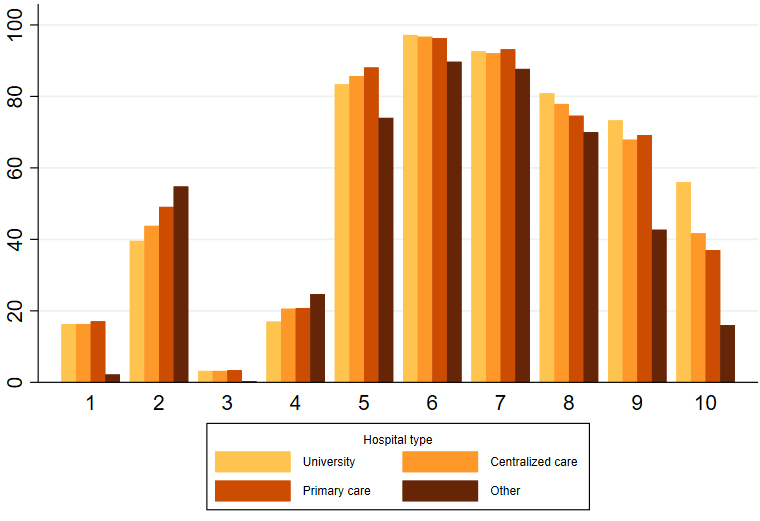

Figure

4 shows the difference in the caesarean section rate between hospitals based on

their size and type of activity. We can observe that for the two main

contributors to our overall caesarean section, namely Groups 2 and 5, the

biggest hospitals tend to have a lower caesarean section rate. The Group 2 caesarean

section rate was 39.6% in university hospitals, while structures with the lowest number

of

patients hospitalised per year had a rate higher than 50%. The same remark can be

made for Group 4:

university hospitals had a caesarean section rate less than a fifth while this rate

climbed to almost a third in

structures with fewer than 9000 hospitalisations

per year. Regarding Group 5, there is a slight increase when comparing

university hospitals with small facilities but all types of hospital had a caesarean

section rate

hovering around 80%. Conversely, for the category of caesarean

section that required neonatal support,

Group 10, it seems that the biggest hospital had a higher caesarean

section rate, 56.0%. Finally, for Group

9, which should have a caesarean section rate of 100%, the biggest facilities seem

to have a better quality of

data entry.

Figure 4Caesarean rate by hospital type. Centralised

care hospitals include hospitals that have between 30,000 and 9000 hospitalisations

per year between all the different services or a high level of training.

Primary care hospitals have fewer than 9000 hospitalisations per year and a

lower level of training. Other hospitals include specialised hospitals where

one specialty is predominant. Group 1: Nulliparous, singleton, cephalic, ≥37

weeks in spontaneous labour; Group 2: Nulliparous, singleton, cephalic, ≥37

weeks, induced or caesarean section before labour; Group 3: Multiparous

(excluding previous caesarean section), singleton, cephalic, ≥37 weeks in

spontaneous labour; Group 4: Multiparous (excluding previous caesarean section),

singleton, cephalic, ≥37 weeks, induced or CS before labour; Group 5: Previous caesarean

section, singleton, cephalic, ≥37 weeks; Group 6: All nulliparous, singleton, breech;

Group 7: Multiparous, singleton, breech (including previous caesarean section);

Group 8: All multiple births (including previous caesarean section); Group 9:

All singleton, abnormal lie (including previous caesarean section); Group 10:

All singleton, cephalic, ≤36 weeks (including previous caesarean section).

Discussion

Main study findings

In

this study, we described caesarean section rates in Switzerland according to Robson’s

Ten-Group Classification System (TGCS). According to these data, the major

contributors were Groups 5 and 2. We also detected

large differences in the distribution of the caesarean section rate according

to the region and the type of hospital considered, without significant trends

during the study period.

Considering

our data, we observed that our population is mainly composed of nulliparous and

multiparous without any obstetric risk, such as the WHO population [10]. We showed

in table 4, a relative contribution of 30.1% from Group 5 and 20.7% from Group 2.

The two groups together account for 50.8% of the overall caesarean section rate.

These results are in accordance with the current literature showing that these

two Groups are those where most efforts should be addressed [3,

12].

When evaluating the caesarean section rate among our population among the most

representative TGCS Groups, we found that it exceeded that suggested by the WHO

recommendations, being 44.4% vs 39.9% and 86.0% vs 74.4%, respectively for Group

2 and Group 5 [10].

When

evaluating caesarean section trends in our population, we noted a stable global

caesarean section rate over the study period. When we look at the different

regions, we can clearly see that some areas reach a caesarean section rate

under the Multi-Country Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health population and

close to the WHO recommendation. For instance, the goal for Group 2 – WHO

recommends a caesarean section rate around 20–35% – is reached by several regions

in our country.

The same observation can be made with Group 4. It is interesting to see the difference

in the caesarean section rate also according to the type of hospital

where delivery took place.

Strengths and limitations

One

of the strengths of this study is that data collected from the Swiss Federal

Statistical Office are population-based and representative of national

practices. They include all deliveries performed in Switzerland, except for home

births, which, according to a national survey published in 2015, accounted for

about 2.5% of all deliveries [13]. We also

chose to perform the study over an 8-year period in order to include a large

number of patients and to evaluate whether variations were detectable during

the study period. The starting period selected was 2014, given that before this

year no distinction was made between planned and emergency caesarean sections.

The absence of this information would affect the classification of these

deliveries to the correct TGCS Group. Using routine data processed by the Swiss

Federal Statistical Office, we were able to classify the great majority of the

deliveries that occurred, thus providing a comprehensive overview of caesarean

section contributors for all Swiss acute care hospitals.

The

main limitations of our study are the type of data collected and its retrospective

nature. In Switzerland, codification is done by non-medical personnel according

to the discharge summary of patients. The variable used for defining the ten TGCS

Groups was extrapolated using the ICD-10 and the Swiss classification of

surgical procedures (CHOP) codes, respectively, for defining the diagnosis and

the procedures performed. Consequently, the quality of data can vary

considerably, increasing the number of misclassifications in the TGCS Groups.This

was reflected by the control

of data quality, performed according to the WHO guidelines; for example,

concerning the number of singleton pregnancies with abnormal

presentation undergoing a vaginal birth. However, in our experience, the most challenging

Group to be

correctly identified was Group 5 (women with a history of caesarean section, singleton,

cephalic, fetus in the ≥37 weeks of gestation), which also represents a

relevant category of caesarean sections in terms of numerosity. Furthermore, according

to the coding system, caesarean

section was indicated for all forms of

uterine scars, including a potential small part of women who have had a

previous myomectomy or other interventions on the uterine wall excluding the caesarean

section.

According to a previous single-centre retrospective

study conducted in Switzerland, the relative rate of caesarean

sections accounting for Group 5

represented the 66.8% of all delivering women with at least one previous caesarean

section[12]. This rate of caesarean

section is much lower than the 86.0% rate

we found in our population but can be linked to a specific population of study

and institutional confounding factors. On the contrary, our data are

superposable with the national data presented in a multicentre study, again,

based on information provided by the national register on the basis of the

standard codification system [14].

In order to reduce misclassifications, we followed up

each woman having already delivered for a period of 10 years before the study

period. Women were tracked by using their personal identity code. We were able

to track 98.0% of all women with a previous history of childbirth. However,

this does not avoid potential errors in classification due to lack of

information or errors in tracking the women. Thus,

according to our experience, there is an urgent need to improve the perinatal

audit in Switzerland. Supporting the use of electronic patient records will

probably help to provide a better collection of routine data, helping to

implement current and future research and medical practice.

Interpretation

The caesarean section rate of 32.9% in Switzerland during the

study period stands notably above the threshold recommended by the World Health

Organization (15%). Although Swiss maternal demographics are broadly comparable

to those in the WHO reference population, the higher caesarean rate suggests

that clinical practice and healthcare system characteristics may be influencing

obstetric outcomes beyond medical necessity.

One of the main insights from our study is the

regional

variability across

the 26 Swiss cantons. For example, caesarean section rates in Group 2

(nulliparous, term, singleton, cephalic pregnancies with induction or pre-labour

caesarean) ranged from 29.8% to 59.6% across regions. Similarly, in Group 5

(women with a previous caesarean), rates ranged from 58.0% to 100%. These

disparities point towards localised differences in obstetric decision-making

and institutional policies rather than clinical risk profiles alone.

This variation is even more evident when analysing the type of

healthcare institution. University

hospitals generally

reported lower caesarean rates, particularly in Groups 2 and 4, compared to primary

care hospitals and smaller clinics.

This suggests that larger institutions, potentially due to greater adherence to

evidence-based protocols or access to multidisciplinary teams, may be more

capable of promoting vaginal deliveries in appropriate cases.

Furthermore, although the TGCS revealed that the main caesarean

drivers in Switzerland are Groups 2 and 5, which is consistent with other

high-income countries, our national rates exceeded WHO’s proposed targets for

these groups. For instance, Swiss caesarean rates reached 44.4% in Group 2 (vs

WHO’s 39.9%) and 86.0% in

Group 5 (vs WHO’s

74.4%). This suggests opportunities for targeted interventions to reduce

unnecessary repeat caesareans and to improve labour management in induced

nulliparous women.

While the WHO’s recommendations are based on data predominantly

collected in low- and middle-income countries, our results affirm that such

international benchmarks can still offer valuable points of comparison for

Switzerland. Several Swiss regions already meet or come close to these targets,

showing that a more

uniform, quality-driven approach to delivery care is feasible within the country.

However, targeting

specific groups by developing adapted strategies for reducing caesarean section

rate can be more challenging than expected. There are many confounding factors

that seem to influence the caesarean section rate, even when considering the TGCS.

They include organisational factors as well as pregnancy-related factors

concerning maternal and fetal conditions, that could impact both the overall and

specific incidence of caesarean sections by TGCS Group [15]. Thus, the TGCS alone

might not be the best tool to

compare different hospitals. Some studies have evaluated the impact of

these confounding factors, showing a potential benefit in including the TGCS when

calculating the adjusted risk for caesarean section [16–18].

Our study also highlights limitations in the current perinatal data collection infrastructure

in Switzerland. The study

revealed poor data quality which was particularly visible for Group 9. This

indicates the need for standardised data acquisition

systems. Strengthening electronic health records and ensuring medically

trained coders are involved in classification would enhance the accuracy and

utility of future audits [19]. We would

also recommend limiting the number of free fields in the patient’s medical

record to multiple-choice pre-established forms, which would make it easier to

obtain clear and complete data.

Conclusions

In

conclusion, Switzerland, while a high-resource and high-performing health

system, still shows considerable variation and overuse of caesarean sections.

Our study underscores the possibility for our country to reach the WHO’s

recommendation. This could be reached by harmonising obstetric practices,

improving institutional protocols and supporting shared decision-making models

across all regions and facility types. National efforts to promote vaginal

birth after caesarean, refine induction protocols, and invest in staff training

could contribute to reducing the caesarean section rate without compromising

maternal or neonatal outcomes.

Data sharing statement

Data of this work belong to the Swiss Federal

Statistical Office and are subject to a data protection contract; they will not

be shared publicly. However, data could be available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Author’s contributions: Conceptualisation:

Arrigo Fruscalzo; Methodology: Arrigo Fruscalzo, S.A., G.P.K.; Validation:

A.V., J-M.A.; Formal analysis: S.A., G.P.K.; Writing—review and editing: S.A.,

G.B., Ben Ali N., Anis Feki, Arrigo Fruscalzo. All authors have read and agreed to

the published version of the manuscript.

Arrigo Fruscalzo

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Hospital of Fribourg

Chemin des Pensionnats 2-6

CH-1708 Fribourg

Arrigo.Fruscalzo[at]h-fr.ch

References

1. McDermott KW, Liang L. Overview of Operating Room Procedures During Inpatient Stays

in U.S. Hospitals, 2018. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical

Briefs [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US);

2006 [cited 2025 Mar 23]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK574416/

2. Souza JP, Gülmezoglu A, Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M, Carroli G, Fawole B, et al.; WHO

Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health Research Group. Caesarean section without

medical indications is associated with an increased risk of adverse short-term maternal

outcomes: the 2004-2008 WHO Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health. BMC Med.

2010 Nov;8(1):71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-8-71

3. Pyykönen A, Gissler M, Løkkegaard E, Bergholt T, Rasmussen SC, Smárason A, et al. Cesarean

section trends in the Nordic Countries - a comparative analysis with the Robson classification.

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017 May;96(5):607–16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13108

4. Antoine C, Young BK. Cesarean section one hundred years 1920-2020: the Good, the Bad

and the Ugly. J Perinat Med. 2020 Sep;49(1):5–16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2020-0305

5. Office fédéral de la statistique, Sections Services de santé, Santé de la population.

Santé reproductive [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/sante/etat-sante/reproductive.html

6. Robson MS. The 10-Group Classification System-a new way of thinking. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

2018 Jul;219(1):1–4. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.05.026

7. Triep K, Torbica N, Raio L, Surbek D, Endrich O. The Robson classification for caesarean

section—A proposed method based on routinely collected health data. Ryckman KK, editor.

PLOS ONE. 2020 Nov 30;15(11):e0242736.

8. Betran A, Torloni M, Zhang J, Gülmezoglu A, the WHO Working Group on Caesarean Section,

Aleem H, et al. Statement on Caesarean Section Rates. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol.

2016 Apr;123(5):667–70.

9. Gu J, Karmakar-Hore S, Hogan ME, Azzam HM, Barrett JF, Brown A, et al. Examining Cesarean

Section Rates in Canada Using the Modified Robson Classification. J Obstet Gynaecol

Can. 2020 Jun;42(6):757–65. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2019.09.009

10. World Health Organization. Robson classification: implementation manual [Internet].

Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017 [cited 2023 Feb 22]. 51 p. Available from:

https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259512

11. Souza JP, Gülmezoglu AM, Vogel J, Carroli G, Lumbiganon P, Qureshi Z, et al. Moving

beyond essential interventions for reduction of maternal mortality (the WHO Multicountry

Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health): a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2013 May;381(9879):1747–55.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60686-8

12. Haydar DA, Vial PY, Baud D. Evolution du taux de césariennes dans une maternité universitaire

suisse selon la classification de Robson. Rev MÉDICALE SUISSE; 2017. p. 5.

13. Erdin R, Schmid M, Pehlke-Milde J. Recensement des activités des sages-femmes indépendantes

de Suisse.

14. Zeitlin J, Durox M, Macfarlane A, Alexander S, Heller G, Loghi M, et al.; Euro-Peristat

Network. Using Robson’s Ten-Group Classification System for comparing caesarean section

rates in Europe: an analysis of routine data from the Euro-Peristat study. BJOG. 2021 Aug;128(9):1444–53.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16634

15. Le Ray C, Blondel B, Prunet C, Khireddine I, Deneux-Tharaux C, Goffinet F. Stabilising

the caesarean rate: which target population? BJOG. 2015 Apr;122(5):690–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13199

16. Quibel T, Rozenberg P, Bouyer C, Bouyer J. Variation between hospital caesarean delivery

rates when Robson’s classification is considered: An observational study from a French

perinatal network. Shamshirsaz AA, editor. PLOS ONE. 2021 Aug 20;16(8):e0251141.

17. Colais P, Fantini MP, Fusco D, Carretta E, Stivanello E, Lenzi J, et al. Risk adjustment

models for interhospital comparison of CS rates using Robson’s ten group classification

system and other socio-demographic and clinical variables. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth.

2012 Jun;12(1):54. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-12-54

18. Muraca GM, Joseph KS, Razaz N, Ladfors LV, Lisonkova S, Stephansson O. Crude and adjusted

comparisons of cesarean delivery rates using the Robson classification: A population-based

cohort study in Canada and Sweden, 2004 to 2016. PLoS Med. 2022 Aug;19(8):e1004077.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004077

19. Robson MS. Known knowns, unknown unknowns and everything in-between - the Ten Group

Classification System (TGCS). BJOG. 2021 Aug;128(9):1454–5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16679