Does health insurance status influence surgical complications? An analysis of abdominal,

thoracic and vascular interventions in a Swiss tertiary referral centre

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4179

Maximilian Bleyab*,

Stefan Gutknechta*,

Laurin Burlaa,

Christoph Zindelacd,

Markus Webera,

Simon Wranna

a Department

for Abdominal, Thoracic, and Vascular Surgery, Triemli Hospital Zurich, Zurich,

Switzerland

b Chair

for Gender Medicine, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

c Department

of Orthopaedics, Balgrist University Hospital, University of Zurich, Zurich,

Switzerland

d Division

of Orthopaedics and Trauma Surgery, Department of Surgery, Cantonal Hospital Graubuenden,

Chur, Switzerland

* Equal

contribution as first authors

Summary

STUDY AIMS: In Switzerland, basic health insurance

is compulsory. Supplementary or private health insurance may be arranged, providing

advantages such as hospital comfort and a free choice of doctors. Since there is

limited data on whether insurance status influences the outcome of surgery, this

study aimed to investigate the influence of supplementary insurance status on the

overall complication occurrence in a group of abdominal, thoracic and vascular surgeries.

METHODS: This study is based on surgical

patient data prospectively collected between September 2016 and March 2018 from

one participating Swiss tertiary referral hospital of the StOP?-trial (NCT02428179),

which investigated the effect of structured intraoperative briefings on patient

outcomes. First, additional data, including insurance status, demographic and surgical

parameters within 30 days was collected. Second, due to endogeneity concerns in

the sample driven by selective access to a supplementary insurance, propensity-score

matching (PSM) was used to balance samples for the treatment variable (insurance

status) by demographic parameters and surgical complexity. The primary outcome was

the estimated treatment effect of a supplementary insurance on the occurrence of

surgical complications, categorised by the Clavien-Dindo classification (CDC). Finally,

multiple logistic regression was used to detect further conditional associations

of demographic and surgical variables with the occurrence of complications.

RESULTS: Of all 3173 procedures, 64.3% were

elective, 48.2% had a higher surgical complexity (excluding appendectomies, cholecystectomies,

hernia surgery and lymph node excision) and 18.6% of all patients had supplementary

insurance. The occurrence of complications, including surgical site infection and

postoperative complications, was 30.4%. After matching 591 patients with basic insurance

to 591 patients with a supplementary insurance, no significant association between

insurance status and complications could be found (crude odds ratio [OR] [95%

CI]: 0.97 [0.77–1.23]). In contrast to insurance status, multiple logistic regression

identified

that variables such as surgical complexity (adjusted OR [95% CI]: 1.80 [1.27–2.56]),

contamination (adjusted OR [95% CI]: 1.90 [1.41–2.56]) and duration of surgery (adjusted

OR [95% CI]: 1.008 [1.006–1.009]) were associated with the occurrence of complications.

CONCLUSION: Despite the different cost-liable

insurance levels, there were no significant differences and, therefore, no disadvantages

for basic insured patients regarding the complication rate in this Swiss cohort

undergoing abdominal, thoracic or vascular surgery.

Introduction

In Switzerland, basic health insurance is compulsory

by law. The goal of this compulsory insurance system is that everyone receives the

same quality of medicine [1], meeting the highest standards. This means that market-orientated

healthcare insurance companies cover all standard treatment costs. Many different

providers also offer various supplementary insurance models, which include, e.g.

benefits in advanced hospitality and Swiss-wide choice of attending doctors [2].

Ethically, medical treatment and the implicated

outcome should be independent of financial concerns. Still, studies of the US healthcare

system found disadvantages for surgical outcomes, as measured by mortality and complication

rates of different surgical procedures, between patients with no insurance or public

insurance such as Medicare or Medicaid [3–5]. Similar findings were reported for

surgical site infections [6]. These studies implicate a strong influence of insurance

status on medical treatment outcomes. There is less knowledge about disparities

in European healthcare systems. A Swiss retrospective study of 30,175 trauma patients

suggests a positive effect of supplementary health insurance on surgical complications

[7]. On the contrary, smaller studies in general and abdominal surgery reflect no

benefit on surgical complication [8] or surgical site infections [9]. Despite showing

less importance of the insurance status in the Swiss health system, many factors

are still indistinct. One main uncharted factor in the medical outcome is the

experience of the lead surgeon. This consideration is of major importance, as many

patients raise concerns about not having the option to choose the most experienced

surgeon. The supplementary insurance often allows the treatment by a more experienced

doctor in the clinic [10]. Abdominal, thoracic and vascular surgery may offer highly

complex anatomical relations. Therefore, repetitive intraoperative decision-making

to adjust the surgical procedure may occur. Intraoperative decision-making may be

highly demanding and rely mainly on the lead surgeon’s experience. Surgical experience

could therefore have a strong impact on intra- and postoperative complications.

Given the lack of studies of comprehensive size

in the field of abdominal, thoracic and vascular surgery, the present study aimed

to investigate the estimated treatment effect of supplementary insurance on surgical

complications for patients for this specialty in Switzerland. Furthermore, we wanted

to evaluate the role of potential confounders on this relationship, including demographic

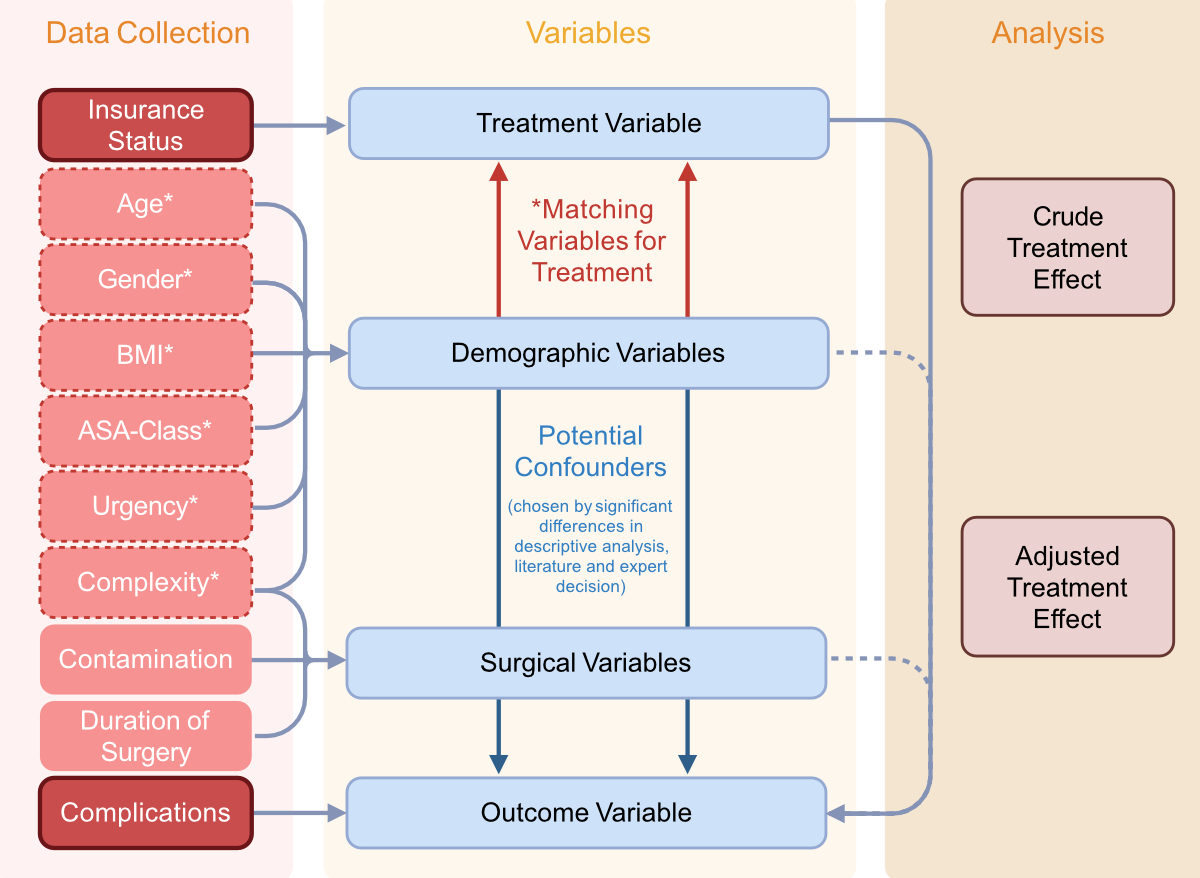

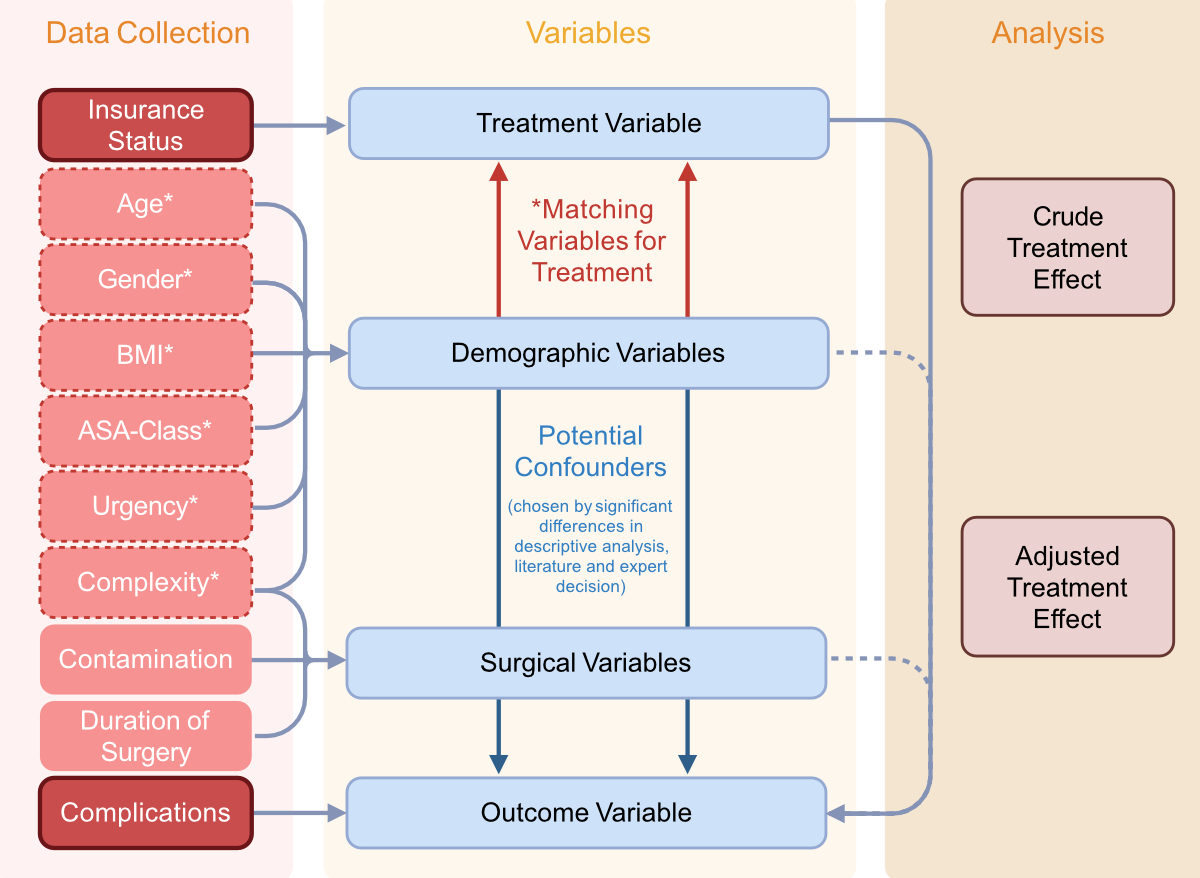

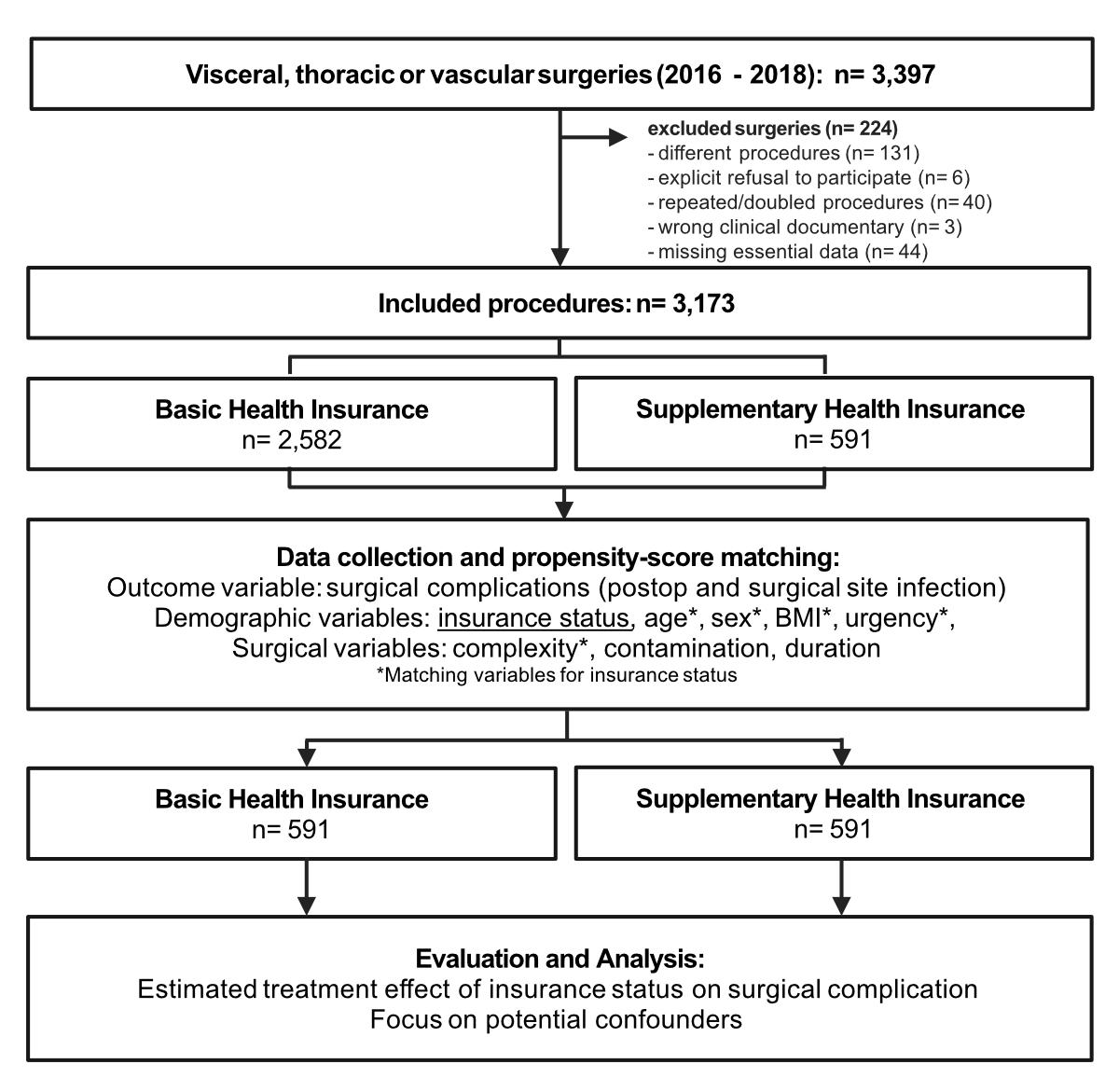

and surgical variables (figure 1).

Figure 1Summary of assessed variables, included

confounders and matching variables. Assessed variables from the StOP-trial and internal

medical records. Matching treatment (insurance) by simulation of a selection process

for insurance along with categories of demographics (age, sex), patient status (body

mass index [BMI], American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score ≥III) and surgical

relevance (urgency, surgical complexity),

which could be potentially influenced by the insurance status. Inclusion of variables

was determined by expected influence for insurance status and occurrence of complications

through the literature, significant differences in first descriptive analysis and

expert decision (SW, SG, MB). Created with BioRender.com.

Methods

Patients

Data from consecutive patients undergoing surgical

procedures at a tertiary referral hospital in Switzerland was collected prospectively

between September 2016 and March 2018 as part of the StOP?-trial (NCT02428179) [11].

In the original multicentre trial, a protocol

for structured pre-surgical communication was tested for influences on surgical

parameters, however, without significant effect for surgical site infection. For

the present study, data of one participating centre (Triemli Hospital, Switzerland)

was used with a focus on patients’ insurance status. Further information about included

patients (demographic and surgical parameters) was obtained from the clinic-internal

digital patient file system. The study was approved by the local ethics committee

before initiation (ID 2020-00265), and general consent was required for the analysis.

The study size depended on the collective of the StOP?-trial of one centre (Triemli

hospital).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients aged over 16 years undergoing surgery

(elective or emergency) in the abdominal, thoracic or vascular surgical department

were included in this study from the StOP?-trial (appendix table S1). This included

patients

with a highly unfavourable prognosis at the time of admission (multiorgan failure

in septic conditions, life-threatening abdominal complications after complex cardiac

surgery, aortic aneurysm rupture, mesenteric ischaemia or other life-threatening

thromboembolic conditions) despite their imminent risk of death within 72 hours,

however without procedures of deliberate termination. Excluded were low-complexity

surgeries, like the opening of a subcutaneous abscess as well as endovascular interventions

and thyroid surgeries, due to their very low degree of surgical site infection.

Additional reasons for exclusion were (b) withdrawal of general consent, (c) repeated

procedures, (d) errors in clinical documentation as well as (e) missing essential

data, such as age, body mass index (BMI) or duration.

Data collection

A summary of included variables is shown in

figure 1. Even though the StOP?-trial concentrated on surgical site infection as

the primary outcome [11], all complications were documented according to the

Clavien-Dindo classification (CDC) as well as other available parameters (e.g.

contamination of the surgical field) used in this analysis. Following the protocol

of the StOP?-trial, all included parameters were collected within 30 days post-surgery

by study nurses and validated independently. Collection of missing values and additional

demographic parameters (insurance status, age, BMI, American Society of Anesthesiologists

[ASA] classification, urgency and duration of surgery) was completed at time of

admission from internal electronic medical records.

Classification of surgical and demographic variables

All patients were separated by their insurance

status into basic insurance (mandatory, public) and additional supplementary insurance

(private) based on their system records. We categorised the surgical procedures

into six groups by their anatomical region

or similar surgical protocol: (a) upper gastrointestinal, (b) hepatic/biliary/pancreatic/splenic,

(c) colorectal, (d) hernia, (e) thoracic and vascular and (f) Other, which

included non-defined exploratory laparotomies or laparoscopies, nephrectomies or

endocrine surgery and lymph node excisions. Furthermore, surgeries were classified

as either “intermediate” or of “major complexity” according to the classification scheme

used by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [12]. The group

of “intermediate complexity” surgeries was represented by

appendectomies, cholecystectomies, hernia surgeries and lymph node excisions. All

other surgeries were classified as surgeries of “major complexity”. Complications

were assessed by study nurses within

30 days post-surgery using the Clavien-Dindo classification [13]. All procedures were

classified into six categories:

free of complications (0), complications without required treatment (I), complications

with required pharmacological treatment (II), complications with requirement of

an intensified intervention (radiological, endoscopic or surgical) (III), life-threatening

complications (IV) and death (V). Additional assessed parameters of the intervention

were patient age in years, sex, BMI

in kg/m2, urgency (elective vs emergency) and duration of surgery in

minutes. The ASA classification was

used as a surrogate parameter to assess the patient’s morbidity, categorising all

patients with a few pre-existing diseases as low morbidity (ASA I–II) and those

with major pre-existing diseases as high morbidity (ASA III–V). The grade of surgical

wound contamination was classified

according to swissnoso (I to IV, clean to dirty-infected), corresponding to the

CDC’s surgical wound classification grades [14].

Outcomes

The primary outcome of this analysis was the

estimated treatment effect of supplementary insurance on the occurrence of complications

(outcome variable) in a comparable population. Furthermore, the association of potential

confounders on the occurrence of complications including surgical parameters such

as complexity, contamination and duration of surgery was assessed (figure 1).

Statistical analysis

Standard descriptive statistics were performed

for analysis of characteristics such as absolute and relative frequencies for categorical

variables and median with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for continuous variables.

For comparisons between basic and supplementary insured patients, Fisher’s exact

tests were used for nominal data and Mann-Whitney tests for continuous data. Two-sided

p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Since the limited access to a supplementary

insurance as well as many different demographic and surgical variables can have

a profound influence on the occurrence of complications, two different approaches

were used to obtain the estimated treatment effect as well as the adjusted association

of several variables (figure 1).

First, given that the endogenous diversity in

our sample of basic and supplementary insured can be attributed, in part, to the

selected access to a supplementary insurance, we used propensity score matching

to balance the probability of being in either insurance group [15]. The matching

variables were chosen according to their potential use in a randomisation protocol

of a clinical trial and as criteria relevant for the insurance selection process

from the perspective of an applicant from an insurance company [16]. Demographic

variables (age, sex, BMI, comorbidities in the form of the ASA classification, and

urgency) were therefore included for matching. Besides these variables, surgical

complexity was used in addition to demographic variables as it could be shown to

be a helpful variable to balance patient characteristics of different included surgeries

(table S2) and therefore allowing a reduction of their heterogeneity for the estimated

treatment effect after matching (appendix figure S1). Furthermore, the complexity

also influences

the choice of insurance status, e.g. through the aim of freely choosing a certain

doctor, making it even more important as a matching variable. With these matching

variables, a propensity score was calculated by logistic regression, estimating

the probability of each patient being in either the treatment or the control group

based on the observed covariates.

We used the R package matchit [15] with

the implemented “1:1 matching” and “nearest” approach for the necessary calculations.

Using 1:1 matching, our model aimed for a straightforward interpretation and increased

comparability. Standardised mean differences (SMD) were used as a balance measure

indicating the success of balancing in matched with a value of <0.1 (table 1)

[17]. However, 1:1 matching led to a substantial reduction in number of patients

with basic insurance, creating potential concerns about reduced generalisability

and robustness. The chosen matching approach was therefore compared to a weighted

“full matching” approach as well as a propensity score-based sensitivity analysis

in a regression model with the treatment variable and propensity score as an independent

variable. For the “full matching”, all procedures were matched with the implemented

function in the matchit package by creating different weights from the observed

matching covariates. Without dropping procedures through 1:1 or k:1 matching, full

matching allows compensation of disadvantages and can achieve balance without dropping

procedures [18]. We used standardised mean differences as well as estimations of

the treatment effect on outcome and surgical variables for comparing the described

matching approaches (table S3 and figure S2). The reduction of standardised

mean difference <0.1 was assumed as a sufficient balancing of either approach

[17]. Comparable estimations of the treatment effect for outcome and surgical variables

between propensity score-based sensitivity analysis, 1:1 and full matching approaches

suggest a robustness of the results despite a loss of numbers in the 1:1 matching

(table S3). Based on these results, 1:1 matching was chosen for the implantation

in our main analysis owing to its advantages in interpretation.

Second, multiple logistic regression was performed

to assess associations of the insurance status, demographic and surgical variables

with the occurrence of complications as shown in figure 1. The pre-defined inclusion

as potential confounders was based on their significant differences in descriptive

analysis, literature research of previous studies [7, 9, 11] or expert decision

(SW, SG, MB). Crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) as well as their 95% CI were reported

for both, unmatched and 1:1 matched samples (figure

3). The multiple regression model

of the matched samples included matching variables in order to account for differences

remaining after matching [19].

The statistical environment R (version 4.1.2)

/ R Studio (version 2024.12.1+563) (session information in supplementary

information) and PRISM (version 10.4.1)

were used for statistical and graphical analyses.

Ethics

All procedures performed in studies involving

human participants complied with ethical standards of the institutional and/or national

research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments

or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved before its initiation by

the local ethics committee (ID 2020-00265).

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in

the study, where appropriate.

Results

Analyses of demographic and surgical parameters before

and after matching

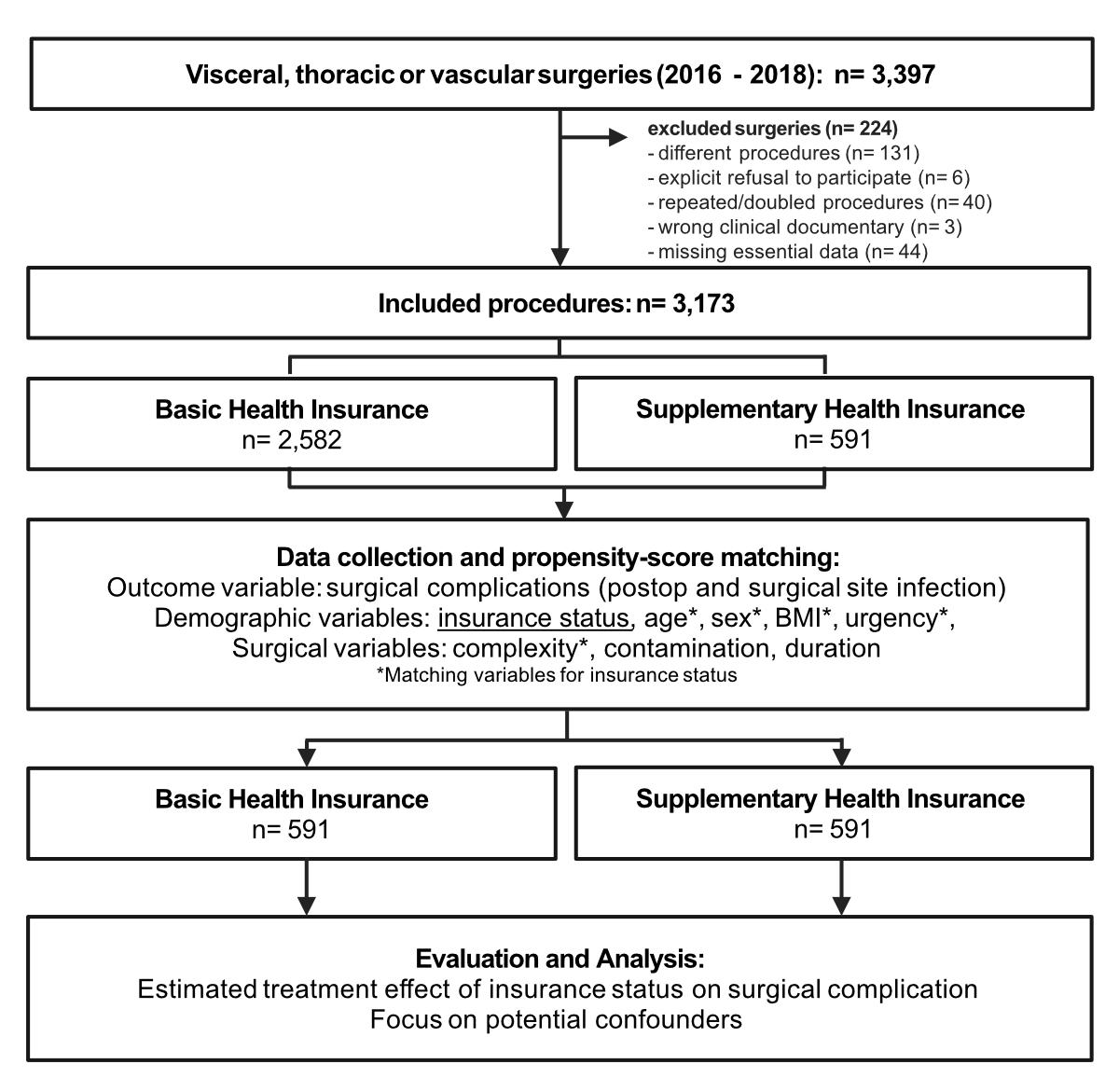

A total of 3397 surgeries meeting the inclusion

criteria were identified (figure 2). Of these 3397 surgeries, 224 were excluded,

giving a final number of 3173 interventions included in the study. Of these, 2645

(83.3%) were abdominal (8.5% upper gastrointestinal, 19.9% hepatic/biliary/pancreatic/

splenic, 20.9% colorectal, 25.3% hernia surgeries) and 528 (16.6%) were thoracic

or vascular surgeries (table S1).

Figure 2Flowchart of study design. Shown

is a summary of included and excluded procedures. After exclusion, 3173 procedures

were analysed, including 2582 with basic health insurance and 591 with supplementary

health insurance. Created with BioRender.com.

In the unmatched population, 2582 (81.4%) had

basic insurance and 591 (18.6%) had supplementary insurance (table 1). Overall,

the median age was 61 years (IQR: 44–73); 1830 were male (57.7%) and 1343 were female

(42.3%). The median BMI for all patients was 25 (IQR: 22–29). The surgeries

were approximately evenly divided between those of “major complexity” (48.2%; n

= 1530) and “intermediate complexity” (51.8%; n = 1643). Two-thirds of surgeries (64.3%;

n = 2039) were electively

planned and 1134 (35.7%) were emergency procedures. One-third (34.0%; n = 1080)

of all patients had major pre-existing diseases with high morbidity (ASA score ≥3).

Interestingly, a significantly higher number of patients with supplementary insurance

had a pre-existing high morbidity (40.0% vs 32.6%). Patients with supplementary

insurance were older: 69 years (IQR: 56–76) vs 59 years (IQR: 42–72). The median

BMI was lower in patients with supplementary insurance: 25.0 (IQR: 23–29) vs 24

(IQR: 22–28). There was an increased rate of “major complexity” surgeries in patients

with supplementary insurance (45.8% vs 58.7%). There were no sex differences between

the basic and supplementary groups. The differences in standardised mean difference

were shown before and after matching by the matching variables. After 1:1 matching,

591 procedures of each insurance status were compared with improved balance, suggested

by the standardised mean difference <0.1 (table 1).

Table 1Demographic and surgical parameters

before and after propensity-score matching. Age and BMI are shown as median with IQR

(interquartile

range); all other categories are shown as counts and %.

| |

Unmatched sample |

Matched sample * |

| Basic |

Supplementary |

Standardised mean

difference (SMD) |

Basic |

Supplementary |

Standardised mean

difference (SMD) |

| Independent variable |

Health insurance |

2582 (81.4) |

591 (18.6) |

|

591 (50.0) |

591 (50.0) |

|

| Matching variables |

*Age in years |

59 (42–72) |

69 (56–76) |

0.477 |

67 (55–78) |

69 (56–76) |

0.004 |

| *Sex: male |

1498 (58.0) |

332 (56.2) |

0.037 |

341 (57.7) |

332 (56.2) |

0.031 |

| *BMI in kg/m2 |

25 (23–29) |

24 (22–28) |

0.219 |

25 (22–28) |

24 (22–27) |

0.026 |

| *Elective cases |

1637 (63.4) |

402 (68.0) |

0.099 |

399 (67.5) |

402 (68.0) |

0.011 |

| *ASA-score ≥III |

|

843 (32.6) |

237 (32.6) |

0.152 |

237 (40.1) |

237 (40.1) |

0.000 |

| ASA I+II |

1739 (67.4) |

354 (59.9) |

|

354 (59.9) |

354 (59.9) |

|

| ASA III |

784 (30.4) |

226 (8.2) |

|

220 (37.2) |

226 (38.2) |

|

| ASA IV |

55 (2.1) |

9 (1.5) |

|

14 (2.4) |

9 (1.5) |

|

| ASA V |

4 (0.1) |

2 (0.3) |

|

3 (0.5) |

2 (0.3) |

|

| *Surgical complexity: major |

1183 (45.8) |

347 (58.7) |

0.262 |

355 (60.1) |

347 (58.7) |

0.028 |

Surgery complication rate, duration and contamination

by insurance status

In total, postsurgical complications occurred

in 964 (30.4%) of all interventions without PS-matching (table 2). Patients with

supplementary insurance had an increased rate of overall postsurgical complications

compared to patients with basic insurance (29.2% vs 35.5%, p = 0.003). The most

relevant difference between basic and supplementary insurance was detectable in

the CDC II group (5.3% vs 8.3%) with a minor difference in mortality (1.8%

vs 2.9%).

In the matched sample, there was no significant

difference in occurrence of complications (35.5% vs 36.2%, p = 0.86). We did not

detect a relevant difference in mortality in the matched sample neither (3.2% vs

2.9%). As shown in table 2, surgeries of patients with supplementary insurance were

shorter compared to their matched procedures (95 min [IQR: 62–172] vs 90 min [IQR:

50–165]; p = 0.005). The number of surgeries with increased contamination was not

significantly different between basic and supplementary insured patients.

Table 2Analysis of surgical complications,

contamination and duration separated by complexity. Complications, assessed by the

Clavien-Dindo classification (CDC), and contamination, assessed by degree (I–IV),

are shown as counts and %, while duration is shown as medians with IQR (interquartile

range).

| |

Unmatched sample |

Matched sample* |

| Basic |

Supplementary

insurance |

p-value** |

Basic |

Supplementary

insurance |

p-value** |

| All

complexities*** |

No

complications |

1828 (70.8) |

381 (64.5) |

0.003 |

377 (63.8) |

381 (64.5) |

0.86 |

| All complications |

|

754 (29.2) |

210 (35.5) |

214 (36.2) |

210 (35.5) |

| CDC I |

341 (13.2) |

85 (14.4) |

|

92 (15.6) |

85 (14.6) |

|

| CDC II |

138 (5.3) |

49 (8.3) |

|

39 (6.6) |

49 (8.3) |

|

| CDC III |

184 (7.1) |

52 (8.8) |

|

47 (8.0) |

52 (8.8) |

|

| CDC IV |

45 (1.7) |

7 (1.2) |

|

17 (2.9) |

7 (1.2) |

|

| CDC V (death) |

46 (1.8) |

17 (2.9) |

|

19 (3.2) |

17 (2.9) |

|

| CDC low (I–II) |

479 (63.5) |

134 (63.8) |

0.99 |

131 (61.2) |

134 (63.8) |

0.62 |

| CDC high (III–V) |

275 (36.5) |

76 (36.2) |

83 (38.8) |

76 (36.2) |

| Duration in min |

85 (55–144) |

90 (50–165) |

0.78 |

95 (62–172) |

90 (50–165) |

0.005 |

| Contamination (II–IV) |

1509

(58.5) |

341

(57.7) |

0.75 |

341 (57.7) |

341 (57.7) |

0.99 |

| Intermediate complexity*** |

No complications |

1190

(85.1) |

208

(85.2) |

0.99 |

191 (80.9) |

208 (85.2) |

0.22 |

| All complications |

|

209

(14.9) |

36

(14.8) |

45 (19.1) |

36 (14.8) |

| CDC I |

118

(8.4) |

19 (7.8) |

|

21 (8.9) |

19 (7.8) |

|

| CDC II |

24 (1.7) |

6 (2.5) |

|

4 (1.7) |

6 (2.5) |

|

| CDC III |

53 (3.8) |

9 (3.7) |

|

13 (5.5) |

9 (3.7) |

|

| CDC IV |

8 (0.6) |

0 (0.0) |

|

5 (2.1) |

0 (0.0) |

|

| CDC V (death) |

6 (0.4) |

2 (0.8) |

|

2 (0.8) |

2 (0.8) |

|

| CDC low (I–II) |

142

(67.9) |

25

(69.4) |

0.99 |

25 (55.6) |

25 (69.4) |

0.25 |

| CDC high (III–V) |

67

(32.1) |

11

(30.6) |

20 (44.4) |

11 (30.6) |

| Duration in minutes |

65 (50–95) |

55 (40–75) |

<0.001 |

65 (50–94) |

55 (40–75) |

<0.001 |

| Contamination (II–IV) |

736

(52.6) |

118

(48.4) |

0.24 |

112 (47.5) |

118 (48.4) |

0.86 |

| Major complexity*** |

No complication |

638

(55.3) |

173

(50.9) |

0.15 |

186 (52.4) |

173 (49.9) |

0.54 |

| All complications |

|

515

(44.7) |

167

(49.1) |

169 (47.6) |

174 (50.1) |

| CDC I |

223

(19.3) |

66

(19.4) |

|

71 (19.4) |

66 (19.0) |

|

| CDC II |

114

(9.9) |

43

(12.7) |

|

35 (10.3) |

43 (12.4) |

|

| CDC III |

131

(11.4) |

43

(12.7) |

|

34 (12.6) |

43 (12.4) |

|

| CDC IV |

7 (0.6) |

0 (0.0) |

|

12 (4.4) |

7 (2.0) |

|

| CDC V (death) |

40 (3.5) |

15 (4.4) |

|

17 (3.8) |

15 (4.3) |

|

| CDC low (I–II) |

337

(61.8) |

65

(62.6) |

0.86 |

106 (62.7) |

109 (62.6) |

0.99 |

| CDC high (III–V) |

208

(38.2) |

66

(37.4) |

63 (37.3) |

65 (37.4) |

| Duration in minutes |

136 (80–225) |

140 (80–222) |

0.88 |

146 (90–235) |

140 (80–222) |

0.33 |

| Contamination (II–IV) |

773

(65.4) |

223

(64.3) |

0.75 |

229 (64.5) |

223 (64.3) |

0.99 |

Surgical complications, contamination and duration

separated by insurance status and surgical complexity

In the matched population, the surgical complexity

was evenly distributed in both insurance groups. In total, 480 (40.6%) interventions

were of intermediate complexity,

while 702 (59.4%) were of major complexity.

Based on the higher frequency of major complexity surgeries, we analysed both groups

of surgical complexity separately

(table 2). Of all 424 complications, 81 (19.1%) appeared in surgeries of intermediate

complexity and 343 (80.9%) in

those of major complexity. Separated

by their surgical complexity and

insurance status, there was a substantial but non-significant trend of reduced occurrence

of complications for patients with supplementary insurance with surgeries of intermediate

complexity (intermediate basic: 45

[19.1%] vs supplementary: 36 [14.8%], p = 0.22). There was no significant difference

in occurrence of complications in the group with major complexity (major basic: 169

[47.6%] vs supplementary 174 [50.1%],

p = 0.54). There were no relevant differences within the grades of complications

or between low- and high-risk complications (CDC I–II vs CDC III–V). The observed

difference in duration of surgery in combined complexity was even more pronounced

in the matched intermediate complexity group (basic: 65 min [IQR: 50–94] vs supplementary:

55 min [IQR: 40–75], p <0.001) without statistical significance in procedures

of major complexity. There was no difference in surgical contamination, either if

separated by the surgical complexity nor

in the overall group.

Estimated treatment effect of insurance status on complication

rate and other variables

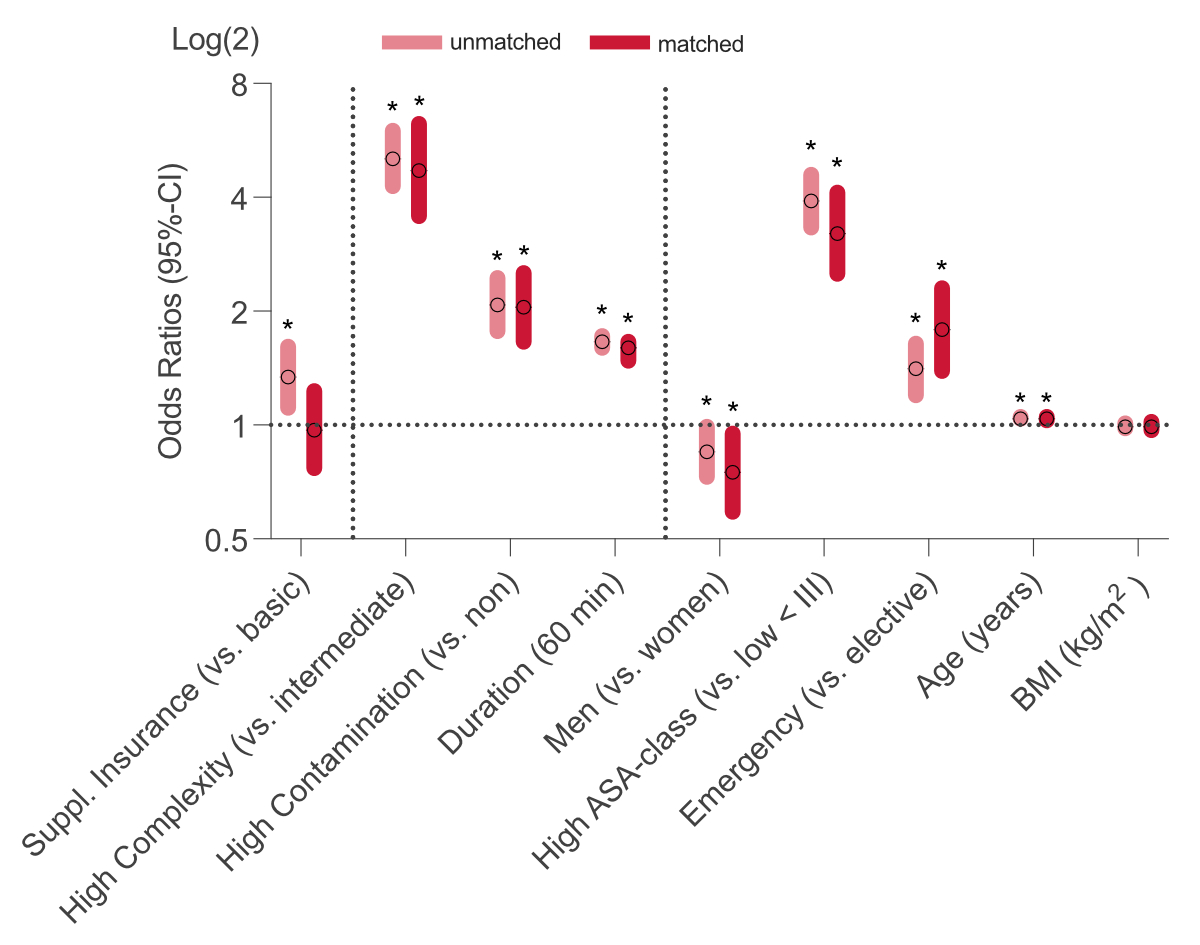

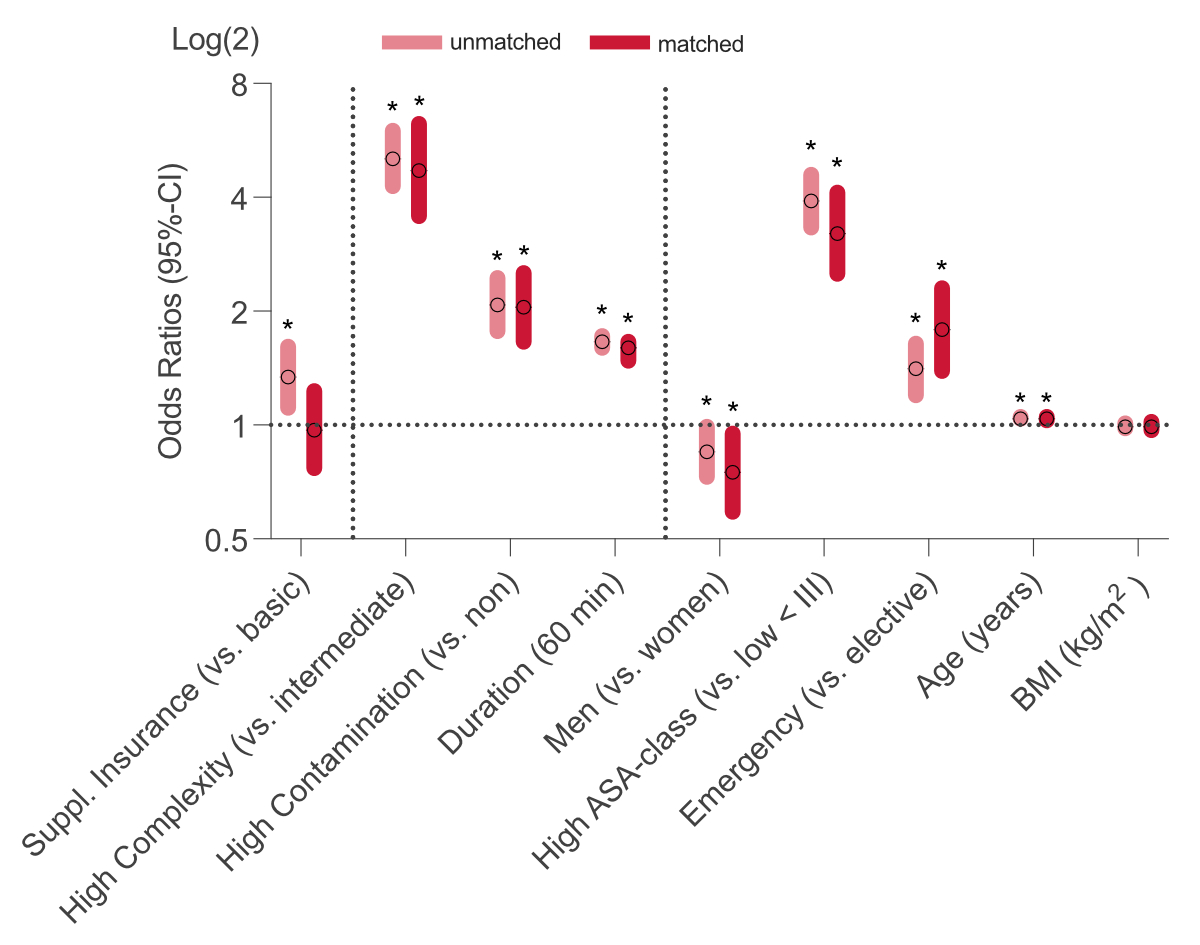

To determine the estimated treatment effect

of insurance status, we compared odds ratios between unmatched and matched samples

of the occurrence of complications (outcome variable) including treatment, surgical

and demographic variables

(figure 3). It was possible to show a change from a significant estimated treatment

effect of insurance status (crude OR [95% CI]: 1.34 [1.11–1.61], p = 0.003) to no

significance by matching (crude OR [95% CI]: 0.97 [0.77–1.23], p = 0.81). There

was no relevant influence of matching on the odds ratios of other variables. The

most pronounced associations with the occurrence of complications were major surgical

complexity (crude OR [95% CI]: 5.06 [4.28–6.00], p <0.001), an increased ASA

classification (crude OR [95% CI]: 3.91 [3.33–4.59], p <0.001) and increased

contamination (crude OR [95% CI]: 2.08 [1.77–2.45], p <0.001).

Figure 3Influence of the treatment (supplementary

insurance) and other variables on the occurrence of complications in unmatched and

matched samples. Shown are associations in odds ratios and 95% confidence interval

(CI) of treatment (insurance status), surgical variables (complexity, contamination,

duration) and demographic variables (sex, American Society of Anaesthesiology [ASA]

classification, urgency, age and body mass index [BMI])

on the occurrence of complications in unmatched (pink) and matched (red) samples.

Statistical significance was set at p <0.05 and is indicated with an

asterisk (*). Analysed variables were included by their expected significance in

first descriptive analysis and expert decision. Binary variables were compared to

a reference level as indicated beside the group.

Association of insurance status, demographic and surgical

variables with occurrence of complications

Based on

the potential confounding of included variables on the occurrence of complications,

multiple logistic regression analyses were performed on

unmatched and matched samples, adjusting for treatment, surgical and demographic

variables (table 3). Similar to the

matching, adjustment for confounding showed no remaining association of insurance

status in the unmatched and matched samples. The following descriptions focus on

associations from the matched sample as both the unmatched and matched samples showed

similar trends after adjustment.

Table 3Logistic regression analyses

of complications of unmatched and propensity-matched surgeries for potential confounding.

| |

Unmatched sample* |

1:1 Matched sample* |

| Unadjusted** |

Adjusted*** |

Unadjusted** |

Adjusted*** |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) |

p-value |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

p-value |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

p-value |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

p-value |

| Treatment variable |

Supplementary insurance (vs basic) |

1.34 (1.11–1.61) |

0.003 |

1.02 (0.81–1.27) |

0.88 |

0.97 (0.77–1.23) |

0.81 |

1.04 (0.79–1.38) |

0.77 |

| Surgical variables |

Major surgical complexity (vs intermediate) |

5.06 (4.28–6.00) |

<0.001 |

2.05 (1.66–2.52) |

<0.001 |

4.71 (3.57–6.26) |

<0.001 |

1.80 (1.27–2.56) |

0.001 |

| Increased contamination (vs non) |

2.08 (1.77–2.45) |

<0.001 |

1.56 (1.28–1.90) |

<0.001 |

2.50 (1.95–3.24) |

<0.001 |

1.90 (1.41–2.56) |

<0.001 |

| Duration in minutes |

1.011 (1.01–1.012) |

<0.001 |

1.008 (1.007–1.009) |

<0.001 |

1.01 (1.008–1.011) |

<0.001 |

1.008 (1.006–1.009) |

<0.001 |

| Matching variables |

Men (vs women) |

0.85 (0.73–0.99) |

0.04 |

0.89 (0.75–1.07) |

0.22 |

0.75 (0.59–0.95) |

0.02 |

0.82 (0.62–1.08) |

0.16 |

| High ASA score (vs low <III) |

3.91 (3.33–4.59) |

<0.001 |

1.56 (1.27–1.91) |

<0.001 |

3.21 (2.51–4.12) |

<0.001 |

1.57 (1.15–2.13) |

0.004 |

| Emergency (vs elective procedure) |

1.41 (1.20–1.64) |

<0.001 |

1.87 (1.54–2.28) |

<0.001 |

1.79 (1.39–2.30) |

<0.001 |

2.14 (1.59–2.91) |

<0.001 |

| Age in years |

1.04 (1.04–1.05) |

<0.001 |

1.03 (1.02–1.03) |

<0.001 |

1.04 (1.03–1.05) |

<0.001 |

1.03 (1.02–1.04) |

<0.001 |

| BMI in kg/m2 |

0.99 (0.98–1.01) |

0.66 |

0.99 (0.97–1.01) |

0.30 |

0.99 (0.97–1.02) |

0.56 |

0.99 (0.96–1.02) |

0.48 |

After adjustment, surgical variables such as

major surgical complexity (adjusted

OR [95% CI]: 1.80 [1.27–2.56], p <0.001), high surgical contamination (adjusted

OR [95% CI]: 1.90 [1.41–2.56], p <0.001) and surgical duration (adjusted OR [95%

CI]: 1.008 [1.006–1.009], p <0.001) remained significantly associated with the

occurrence of surgical complication. Adjustment for demographic variables showed

that a high (≥III) ASA classification (OR [95% CI]: 1.57 [1.15–2.13], p = 0.004),

an

emergency (OR [95% CI]: 2.14 [1.59–2.19], p <0.001) and higher age (OR [95%

CI]: 1.03 [1.02–1.04], p <0.001) were positively associated with the occurrence

of complications. Urgency is the only variable whose association increased after

adjustment (crude OR: 1.79 vs adjusted OR: 2.14). Male sex had a significant association

with a reduced occurrence of complications in the univariate analysis (OR [95%

CI]: 0.75 [0.59–0.95], p = 0.02) without significant association after adjustment

(OR [95% CI]: 0.82 [0.62–1.08], p = 0.16). There was no association between the

BMI and occurrence of complication throughout the analyses.

Discussion

This study provides data

concerning overall complications of surgical

patients undergoing abdominal, thoracic

and vascular surgical interventions in relation to the patient’s insurance

status. We were able to investigate a large cohort of patients acquired prospectively

for 18 months. The cohort represents an average patient population and interventions

of a large Swiss hospital.

We found no evidence for an association between

supplementary insurance and reduced surgical complications. In the analysis of the

unmatched sample, patients with basic insurance had even fewer overall complications

than those with supplementary insurance. To investigate this initial finding, we

used propensity-score matching (PSM) to balance an endogenous diversity of demographic

parameters as we expected a selective access to supplementary imbalances and searched

for other possible confounders of the found association. We showed no significant

estimated treatment effect of a supplementary insurance in a balanced sample with

a comparable patient population. However, demographic parameters, as well as contamination

of the surgical wound according to the standards of swissnoso [14], complexity of

the performed surgeries adapted to the National Institute for Health and Care

Excellence (NICE) classification [12] and duration of surgery were found to be significantly

associated with the occurrence of surgical complications. We conclude therefore

that the statement of comparable standards in healthcare quality in general surgical

patients, regardless of the insurance status, remains valid.

Contextualisation of the study results within the Swiss

healthcare system

Intuitively, benefits regarding complication

rates from a supplementary insurance status in the Swiss healthcare system were

expected, while no such benefits were statistically measurable in this study. A

potential explanation could be that the Swiss healthcare system meets high quality

standards for all general surgical patients. Furthermore, intensive supervision

of surgical residents is standard to provide this quality, and if treatment exceeds

the resident’s experience, the threshold for attending doctors to intervene is low.

Therefore, the expected benefit of supplementary insurance is mainly the direct

care by an experienced attending doctor, which is eliminated by the described intensive

supervision.

In this study, it was impossible to measure

the impact of surgical experience in a statistically reliable manner, and reasoning

would remain hypothetical. However, adjusted to the surgical complexity and influences

such as the emergency status, our results showed no association between surgical

complications and insurance status. Therefore, we can agree with the conclusions

made by Schneider et al. and Duggan et al., which focused on the correlation between

surgical site infection or medical outcomes of oncological surgical procedures and

insurance status in the Swiss healthcare system [8–9]. In their studies, no negative

impact of basic insurance could be found either. In comparison to their studies, our analyses showed

results for a larger spectrum of complications and surgeries, better representing

the real-world situation. Funke et al. showed a significant increase in surgical

complications among trauma patients with basic insurance [7]. However, a direct

comparison of trauma and abdominal surgery remains speculative and can differ in

terms of complexity and variety of surgical procedures. Furthermore, as major surgeries

in the abdominal, thoracic or vascular field require a high level of interdisciplinary

cooperation, for example with intensive care medicine and complex post-operative

management, the number of complications could be less reliant on the experience of

the surgeon alone. Similar to our study,

Funke et al. did not find a difference in mortality associated with health insurance

status [7].

Association of included variables interfering with

the insurance status

Our results emphasise the importance of recognising

external influences when investigating insurance status. Matching our sample by

the probability to have access to a supplementary insurance through balanced co-variables

influenced the estimated treatment effect substantially. We found that age especially

was a relevant factor for the probability of being supplementary insured – which

has also been shown by Altwicker-Hamori [16]. Age is of special importance, as older

patients can be for example more likely to have a supplementary insurance and have

higher rate of ASA-associated physical status, associated with an increased occurrence

of complications. Those results are similar to Funke et al [7]. Another example

could be that supplementarily insured patients also had more surgeries with major

complexity, which was then associated

with a higher occurrence of complications. However, it is also likely that patients

with planned major surgery rely on supplementary insurance for the free choice of

doctors or hospital. In our perspective, it is therefore necessary to acknowledge

both influences, the selected access to health insurances as well as the potential

confounding of different demographic and surgical variables. For future studies,

we support considering other relevant demographic parameters such as education or

income. Another important association that should be considered for future studies

was the significant time reduction of surgeries for patients with supplementary

insurance similar to Schneider et al. and Duggan et al. [8–9]. This time reduction

was especially present within surgeries of intermediate complexity. Whether this result

was a simple expression of a more subtle

difference of complexity in surgery with an intermediate profile or that the surgery

performed by

a senior surgeon just took less time was not evident in our analysis. Our analyses

support that a prolonged duration of surgery, as a surrogate of a more challenging

surgery, was associated with an increased occurrence of complications. However,

we could not detect a significant reduction of complications along with the time

reduction of patients with supplementary insurance.

Generalisability of the study results

The patients themselves might expect a more

beneficial outcome for the additional cost of supplementary insurance. Several studies

in the US healthcare system show an evident difference with private/supplementary

healthcare plans [3–4]. The American system risks creating different classes in

medical treatment. But in contrast to the Swiss healthcare system and our study,

most US studies focus on patients with private health insurance and those without

insurance at all [20]. Especially in Switzerland, fundamental treatment is covered

by compulsory basic healthcare, and the increment to the therapy within a supplementary

healthcare plan is marginal regarding the medical quality [2]. Therefore, a significant

difference in medical treatment and outcome may be expected in the American healthcare

system but not in the universal coverage system of Switzerland. However, political

debates regarding the Swiss health insurance system are omnipresent in Swiss politics.

The fear of a two-tier medical system is a recurring argument in such debates. At

this point, our study indicates no evidence for a two-tier medical system in Switzerland

regarding surgical treatment.

There is also the probability that benefits

offered by supplementary insurances in Switzerland might influence the intended

medical outcome without being reflected by the complication rate. Complications

of surgical patients can only be a surrogate marker for treatment quality but are

not the same as the intended medical outcome, for example the overall survival in

cancer patients. There might be many connections between complications and medical

outcomes without absolute certainty that overcoming complications may affect the

medical outcome. Furthermore, the quality of the management of surgical complications

may outweigh the original impact of the complication.

Limitations

This study is limited in its conclusion as there

is no general definition of medical outcome, and investigations require the assessment

of different surrogate parameters, such as surgical site infection or postsurgical

complications. Thus, making final statements about causality can be challenging

after all and requires comprehensive future guidance to improve robust definitions

which can be summarised in research, such as meta-analyses.

There are different possibilities of selection

biases inherent through the study design. First, this study is limited to the data

of the initial StOP?-trial, which was not randomised, and accumulates a further

selection bias through the focus on one centre and higher complexity surgery. However,

similar to the StOP?-trial, our study tried to increase the generalisability by

a broad inclusion and restricted exclusion. While the inclusion of many different

surgery types can lead to heterogeneity, we tried to minimise it through categorisation

into intermediate and high complexity, matching and statistical adjustment, with

the purpose of reducing the influences of heterogeneity on the outcome variable

(figure S1). Including surgeries typical for a department of abdominal, thoracic

and vascular surgery, we hope to allow increased generalisability and comparison

to a typical Swiss tertiary referral centre. However, it is important to encourage

further studies to focus on a comparison within separate surgery types. Second,

we experienced a high endogenic heterogeneity of patients with basic and supplementary

insurance. We tried to reduce this imbalance and increase plausibility through the

use of propensity-score matching. As already stated in the methods, 1:1 matching

can lead to a selection bias by dropping important residues during the matching

process. In our study, the experienced bias was limited as we could show robustness

of our matching through sensitivity analysis (figure S2 and table S3). However,

there will always be a risk for residual and unmeasured confounding, as the matching

uses a retrospective approach based on observed variables. Third, patients were

excluded when data was missing to simplify the analysis, creating a potential for

selection bias and unknown confounding. It is therefore important to point out that

our results aim not for causality but to reflect associations of treatment on the

outcome translatable to a comparable cohort. Propensity-score matching cannot substitute

for prospective randomisation and a multicentric view to allow casual conclusions

and increased generalisability.

As our study data was limited by the framework

of the StOP?-trial, we want also to address the need for further investigations

of important parameters such as Comprehensive Complication Index (CCI) or surgical

experience, which could not be assessed in this study.

Conclusion

We demonstrated evidence that insurance status

is not associated with surgical complications of abdominal, thoracic and vascular

surgeries within the Swiss healthcare

system. The duration of surgery of intermediate complexity did differ significantly

in favour of patients with supplementary insurance. Nevertheless, basic insurance

status did not increase significantly the occurrence of surgical complications in

a comparable cohort.

Data sharing statement

Upon reasonable request, individual data or codes that support results can be shared

with necessary adjustments for deidentification, ending after 48 months following

publication.

Requests must be approved by the corresponding author as well as an independent

committee for measures of ethical approval.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank for all involved support, especially

Prof. Ulrike Held and Dr Leo Schmallenbach for their help and critical comments.

Author contributions: Study conception and design: SW, LB, SG.

– Acquisition of data: MB, SW, SG, LB, CZ. – Analysis and interpretation of data:

MB, SW, SG. – Drafting of manuscript: MB. – Critical revision of manuscript: All

mentioned authors.

Dr med. Maximilian Bley, MSc

Chair

for Gender Medicine

University

of Zurich

Wagistrasse

12

CH-8952

Schlieren

maximilian.bley[at]uzh.ch

References

1. Swiss Federal Council, Botschaft über die Revision der Krankenversicherung. 1991.

2. Paccagnella O, Rebba V, Weber G. Voluntary private health insurance among the over

50s in Europe. Health Econ. 2013 Mar;22(3):289–315. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.2800

3. Veltre DR, Sing DC, Yi PH, Endo A, Curry EJ, Smith EL, et al. Insurance Status Affects

Complication Rates After Total Hip Arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019 Jul;27(13):e606–11.

doi: https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00635

4. Williams DM, Thirukumaran CP, Oses JT, Mesfin A. Complications and Mortality Rates

Following Surgical Management of Extradural Spine Tumors in New York State. Spine.

2020 Apr;45(7):474–82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000003294

5. Goodair B, Reeves A. The effect of health-care privatisation on the quality of care.

Lancet Public Health. 2024 Mar;9(3):e199–206. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(24)00003-3

6. Manoso MW, Cizik AM, Bransford RJ, Bellabarba C, Chapman J, Lee MJ. Medicaid status

is associated with higher surgical site infection rates after spine surgery. Spine.

2014 Sep;39(20):1707–13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000000496

7. Funke L, Canal C, Ziegenhain F, Pape HC, Neuhaus V. Does the insurance status influence

in-hospital outcome? A retrospective assessment in 30,175 surgical trauma patients

in Switzerland. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022 Apr;48(2):1121–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-021-01689-x

8. Schneider MA, Rickenbacher A, Frick L, Cabalzar-Wondberg D, Käser S, Clavien PA, et

al. Insurance status does not affect short-term outcomes after oncological colorectal

surgery in Europe, but influences the use of minimally invasive techniques: a propensity

score-matched analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2018 Nov;403(7):863–72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-018-1716-8

9. Duggan BT, Roth JA, Dangel M, Battegay M, Widmer AF. Impact of health insurance status

on surgical site infection incidence: A prospective cohort study. Infect Control Hosp

Epidemiol. 2019 Sep;40(9):1063–5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2019.195

10. Sagan A, Thomson S, editors. Voluntary health insurance in Europe: Country experience.

Copenhagen, Denmark; 2016.

11. Tschan F, Keller S, Semmer NK, Timm-Holzer E, Zimmermann J, Huber SA, et al. Effects

of structured intraoperative briefings on patient outcomes: multicentre before-and-after

study. Br J Surg. 2021 Dec;109(1):136–44. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/bjs/znab384

12. NICE. Routine preoperative tests for elective surgery, Guideline [NG45]National Institute

for Health and Care Excellence; 2016.

13. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new

proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann

Surg. 2004 Aug;240(2):205–13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae

14. Ruef, C., M.C. Eisenring, and N. Troillet, Erfassung postoperativer Wundinfektionen.

Nationales Programm durchgeführt von Swissnoso im Auftrag des ANQ, 2013.

15. Little RJ, Rubin DB. Causal effects in clinical and epidemiological studies via potential

outcomes: concepts and analytical approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21(1):121–45.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.121

16. Altwicker-Hámori S, Stucki M. Factors associated with the choice of supplementary

hospital insurance in Switzerland - an analysis of the Swiss Health Survey. BMC Health

Serv Res. 2023 Mar;23(1):264. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09221-0

17. Kuss O. The z-difference can be used to measure covariate balance in matched propensity

score analyses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013 Nov;66(11):1302–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.06.001

18. Heinz P, Wendel-Garcia PD, Held U. Impact of the matching algorithm on the treatment

effect estimate: A neutral comparison study. Biom J. 2024 Jan;66(1):e2100292. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/bimj.202100292

19. Ho DE, Imai K, King G, Stuart EA. Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing

model dependence in parametric causal inference. Polit Anal. 2007;15(3):199–236. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpl013

20. Congress of the United States Congressional Budget Office, Federal Subsidies for Health

Insurance Coverage for People Under Age 65: 2019 to 2029. 2019.

Appendix

The appendix is available in the pdf version of the article at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4179.