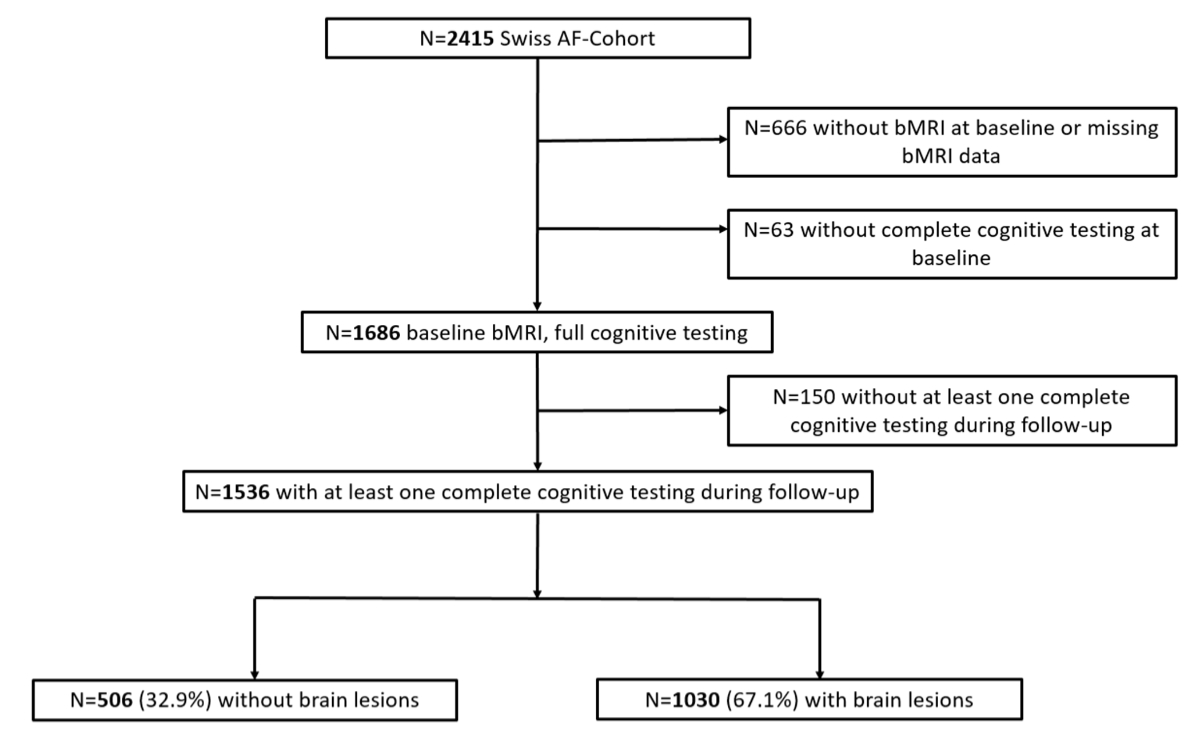

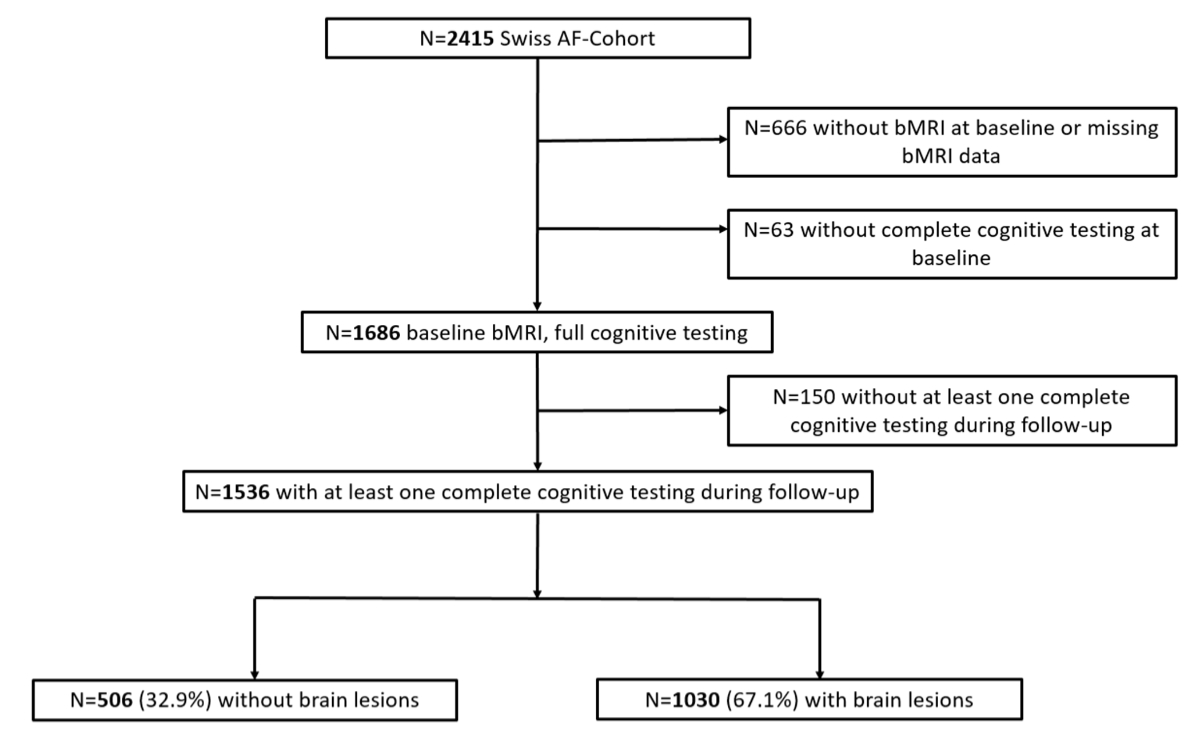

Figure 1Flowchart for patient selection. bMRI: brain magnetic resonance imaging; Swiss-AF: Swiss Atrial Fibrillation cohort study.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4059

The development of cognitive decline and the occurrence of dementia are major health concerns in our ageing society [1–3]. With an expected 74 million patients living with dementia in 2030, it is one of the most important diseases associated with the loss of disability-adjusted life years, as it leads to premature mortality and severe disability [3]. Cognitive decline, Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia and mixed forms of dementia are strongly believed to be of multifactorial origin. Cerebrovascular dysfunction and underlying small-vessel disease contribute to most dementia types [4].

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is strongly associated with cognitive decline and dementia [5–8]. We have previously shown in the Swiss Atrial Fibrillation Cohort Study (Swiss-AF) [9] that atrial fibrillation patients have a high burden of various brain lesions on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These brain lesions include microbleeds, white matter lesions and ischaemic strokes, both clinically overt and covert (brain infarcts without any symptomatic presentation) [10]. All of these lesions are known to potentially contribute to a decline in cognition over time [11, 12]. However, the association between atrial fibrillation, structural brain damage and the development of cognitive decline over time is still poorly understood. A better understanding of these associations may improve our understanding of the functional relevance of brain damage in atrial fibrillation patients and could thus be helpful for the future management of these patients.

Therefore, the aim of this analysis was to investigate the association of prevalent brain lesions with the development of various cognitive functions over time in patients with atrial fibrillation. More precisely, we aimed to investigate whether the presence or absence of brain lesions in atrial fibrillation patients at a specific point in time, i.e. at baseline, would be associated with a decline of various cognitive functions over time.

The Swiss Atrial Fibrillation (Swiss-AF) study is an ongoing prospective multicentre cohort study that enrolled 2415 patients with atrial fibrillation between 2014 and 2017 across 14 centres in Switzerland (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02105844) [9, 10, 13]. The main inclusion criteria were the presence of documented atrial fibrillation and age ≥65 years. A small (10%) group of patients <65 years was enrolled to analyse the effects of atrial fibrillation on work capacity. Patients with secondary causes of atrial fibrillation (e.g. due to surgery), with an acute illness within the past 4 weeks and patients who were unable to provide informed consent were excluded. Detailed information on recruitment and enrolment has previously been provided elsewhere [9].

Of the 2415 patients initially enrolled in the Swiss-AF cohort, 666 did not undergo a baseline brain MRI (mostly due to the presence of implanted devices), and were therefore excluded from the present analysis. An additional 63 patients were excluded because they did not complete all of the cognitive tests at the baseline visit. Another 150 patients were excluded because they did not complete any other cognitive testing after the baseline visit. Therefore, data of 1536 patients were used for this analysis (figure 1). A total of 260 patients died and 103 patients were lost to follow-up, i.e. they were no longer reachable or dropped out. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (EKNZ; 2014-067; PB_2016-00793; 2021-00701) and it complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Figure 1Flowchart for patient selection. bMRI: brain magnetic resonance imaging; Swiss-AF: Swiss Atrial Fibrillation cohort study.

At baseline and at yearly follow-up visits, information concerning patient demographics, medical history (for example history of stroke or heart failure), cardiovascular and lifestyle factors (such as smoking status, alcohol consumption and physical activity) and medication was obtained through standardised case report forms by trained study personnel. Participants’ weight and height were measured. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in metres squared. At baseline, three consecutive blood pressure measurements were obtained and their mean was used for this analysis. Atrial fibrillation type was classified into paroxysmal and non-paroxysmal (persistent and permanent atrial fibrillation), according to guideline recommendations [14].

All brain MRIs were performed locally at the study centres on 1.5 or 3.0 T scanners with a standardised protocol that included 3D T-weighted magnetisation-prepared rapid gradient echo, 2D fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). The scans were analysed by experts at the Medical Image Analysis Centre (MIAC) in Basel, Switzerland, with no knowledge of patient characteristics or of their cognitive function. Ratings were confirmed by certified neuroradiologists. Ischaemic brain lesions were defined as either non-cortical or cortical hyperintense lesions, irrespective of their size. Microbleeds, defined as hypointense, nodular lesions in T2*-weighted or susceptibility-weighted imaging, were identified and counted. White matter lesions (WML) (in the periventricular or deep white matter) were identified as hyperintense lesions in T2*-weighted imaging/FLAIR sequences and graded with the Fazekas scale [15]. Only white matter lesions with a Fazekas score ≥2 (defined as at least “moderate lesion load”) were counted as “brain lesions present”. In our analysis, patients with any of the aforementioned lesion types were compared with patients with no lesions on baseline MRI.

The study personnel at all centres was centrally trained to perform the following standardised neurocognitive assessments: The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [16], Trail Making Test A and B (TMT A and B) [17, 18], Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST) and Semantic Fluency Test (SFT). The assessments were done at baseline and at on-site follow-up visits (follow-ups 1, 2, 3, 4 and 7). Compared to the other neurocognitive tests, the Semantic Fluency Test was available more often since this test could be done during the on-site visits, as well as by phone (follow-ups 5 and 6, as well as with patients who could not attend their on-site visits). Additionally, we used the Cognitive Construct (CoCo) [19] score, which was developed within the Swiss-AF study using principal component analysis. The CoCo score reflects the cognitive performance obtained by all of the abovementioned cognitive tests. More precisely, it is a factor score made up of 17 differently weighted combined items of the previously mentioned neurocognitive tests, with higher scores indicating a better cognitive performance. The CoCo score thus has a high potential to be very sensitive in detecting cognitive change. As depression has been shown to correlate with cognitive performance [20], the geriatric depression scale (GDS) [21] was administered at all on-site visits. Depression was defined as a score of >5 points on the geriatric depression scale [22]. Detailed information concerning the cognitive tests is presented in the supplementary material in the appendix.

Baseline characteristics were stratified according to the presence of any brain lesions on the brain MRI at baseline. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation or as median (interquartile range). Categorical data are presented as counts (percentage). For a sensitivity analysis, the same baseline characteristics were additionally stratified according to whether patients had an event (independently of whether they were still enrolled in the study, died or were lost to follow-up, i.e. were no longer reachable or dropped out), had no event but were still enrolled in the study, had no event and were lost to follow-up, or had no event and died. The event corresponds to cognitive decline on the MoCA.

The primary outcome was cognitive decline, defined as a decline of at least 1 standard deviation of the respective individual baseline value of participants’ age- and education-standardised baseline MoCA or CoCo scores. The MoCA was used as a primary outcome due to its widespread use and high acceptance as a screening tool for mild cognitive impairment [16]. The CoCo score was used as a primary outcome as it combines all the individual tests in one score. Cognitive decline in the other individual cognitive test scores (i.e. Semantic Fluency Test, Digit Symbol Substitution Test, Trail Making Test A and B) were defined as secondary outcomes. Cognitive decline was defined analogously to the definition described for the MoCA and CoCo scores.

Person-years of follow-up were calculated as the time from baseline until cognitive decline, the last visit before study termination (death, drop-out, loss to follow-up) or the last visit for the remaining patients. Incidence rates per 100 patient-years were calculated, and confidence intervals (CIs) for incidence rates were derived using the exact Poisson method. Multivariable adjusted Cox regression models were performed using cognitive decline as the outcome variable and any brain lesion as the exposure of interest. A first model was adjusted for age and sex. A second model was additionally adjusted for BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, atrial fibrillation type, history of coronary heart disease, history of diabetes, history of renal failure, history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA), history of systemic embolism, history of peripheral artery disease, smoking status, physical activity, alcohol consumption, geriatric depression scale score >5, anticoagulation and antithrombotic treatment. As covariate values were only missing for a few patients (n = 12), these patients were removed from the multivariable analysis. We examined the proportional hazards assumptions visually, by inspecting the Schoenfeld residuals and the clog-log transformed data, and by using the Schoenfeld residuals test.

In a sensitivity analysis, the analysis was repeated excluding history of stroke/TIA as an adjusting variable in the second model. In another sensitivity analysis, we additionally adjusted the second model for atrial fibrillation interventions at baseline (history of radiofrequency catheter ablation, history of electrical cardioversion, history of pulmonary vein isolation). To investigate whether the MoCA score at baseline affects cognitive outcome, we performed multivariable adjusted Cox regression models stratified according to the clinically meaningful cutoff score of 26 [16] and added an interaction term. We also conducted sensitivity analyses to explore how patients who died, dropped out or were no longer reachable affected the findings (survival bias). For these analyses, patients who dropped out or were no longer reachable were combined into one category, i.e. lost to follow-up. As the data of the present analysis are interval-censored, patients who did not have an event (i.e. cognitive decline on a cognitive test) were included in our original analysis accordingly. Assuming a worst-case scenario, these patients could potentially have had an event before they died or were lost to follow-up. To take such a scenario into account, we re-analysed our data after giving all patients who died or were lost to follow-up a hypothetical event at the last available visit (scenario 1). In an additional analysis (scenario 2), we excluded all patients who died or were lost to follow-up without cognitive decline from the corresponding cognitive test and repeated our analyses.

All analyses were done using R (version 4.3.2). The following R packages were used for our analyses: survival, ggplot2, survminer, dplyr, tableone, tidyverse.

The mean (SD) age of this atrial fibrillation population was 72.1 (±8.4) years, 286 (27%) were female and any brain lesion was detected on baseline MRI in 1030 patients (67.1%). Baseline characteristics stratified by the presence of any brain lesion are shown in table 1. Compared to patients with no brain lesions, patients with any brain lesion were older (mean 74.5 ± 7.3 versus 67.4 ± 8.4 years), and they more often had cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension (72.9% versus 57.5%) and diabetes (16.4% versus 11.5%). Furthermore, fewer patients with any brain lesion had paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (44.1% versus 51.0%). Sex and depression (geriatric depression scale >5) were equally distributed between the two groups (female sex: 27.8% versus 25.5%; depression: 4.3% versus 4.0%). Most patients were on oral anticoagulation (87.4% without and 91.6% with brain lesions). Detailed information concerning oral anticoagulation at baseline is shown in appendix table S1. Baseline cognitive scores for both groups are presented in appendix table S2. Compared to patients without brain lesions, the baseline MoCA score in patients with any lesions was 25.3 versus 26.3. Participants’ CoCo score ranged from −1.25 to 1.79, with a mean of 0.07 (±0.52). Compared to patients without brain lesions, the CoCo score in patients with any lesion was −0.03 versus 0.28 (table S2).

Table 1Baseline characteristics overall and stratified by the presence of brain lesions on baseline MRI. Physical activity was defined as patients reporting regular sports activity, depression was defined as a geriatric depression scale score over 5 points. Missing data (n): CHA2DS2-VASc = 1, systolic blood pressure = 8, diastolic blood pressure = 8, hypertension = 8, heart rate = 1, baseline rhythm = 5, smoker = 1, physical activity = 1, depression = 1, history of heart failure = 1, antiplatelet therapy = 1. As covariate values were only missing for a few patients (n = 12), they were removed from the multivariable analysis. Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, median [interquartile range] or count (percentage).

| Characteristics | Overall | No brain lesions | Any brain lesions | |

| n | 1536 | 506 (32.9) | 1030 (67.1) | |

| Female sex | 415 (27.0) | 129 (25.5) | 286 (27.8) | |

| Age (years) | 72.1 ± 8.4 | 67.4 ± 8.4 | 74.5 ± 7.3 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.7 ± 4.8 | 28.2 ± 5.0 | 27.5 ± 4.6 | |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 3.2 ± 1.7 | 2.3 ± 1.4 | 3.7 ± 1.6 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 135 ± 18 | 132 ± 16 | 136 ± 19 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 79 ± 12 | 79 ± 11 | 78 ± 12 | |

| Hypertension | 614 (40.2) | 182 (36.2) | 432 (42.1) | |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 66 [58, 77] | 65 [56, 76] | 67 [58, 78] | |

| Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation | 712 (46.4) | 258 (51.0) | 454 (44.1) | |

| Baseline rhythm | Sinus rhythm | 880 (57.5) | 348 (68.8) | 532 (51.9) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 625 (40.8) | 151 (29.8) | 474 (46.2) | |

| Other | 26 (1.7) | 7 (1.4) | 19 (1.9) | |

| Current smoker | 116 (7.6) | 50 (9.9) | 66 (6.4) | |

| Physical activity, yes | 774 (50.4) | 281 (55.6) | 493 (47.9) | |

| Alcohol consumption, yes | 1291 (84.1) | 443 (87.7) | 848 (82.3) | |

| Depression | 64 (4.2) | 20 (4.0) | 44 (4.3) | |

| History of heart failure | 317 (20.7) | 58 (11.5) | 259 (25.2) | |

| History of hypertension | 1042 (67.8) | 291 (57.5) | 751 (72.9) | |

| History of diabetes mellitus | 227 (14.8) | 58 (11.5) | 169 (16.4) | |

| History of stroke/TIA | 309 (20.1) | 40 (7.9) | 269 (26.1) | |

| History of coronary artery disease | 401 (26.1) | 81 (16.0) | 320 (31.1) | |

| History of systemic embolism | 77 (5.0) | 16 (3.2) | 61 (5.9) | |

| Anticoagulation therapy | 1385 (90.2) | 442 (87.4) | 943 (91.6) | |

| Antiplatelet therapy | 268 (17.5) | 65 (12.8) | 203 (19.7) | |

| Antihypertensive therapy | 1088 (70.8) | 302 (59.7) | 786 (76.3) | |

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; TIA: transient ischaemic attack.

CHA2DS2-VASc is a stroke risk assessment tool for atrial fibrillation patients that helps clinicians decide whether patients should receive anticoagulation [14]. It includes congestive heart failure; hypertension; age ≥75 years; diabetes; prior stroke, transient ischaemic attack or thromboembolism; vascular disease; age 65 to 74 years; and sex (female).

Concerning the proportional hazard assumptions, there was no strong indication of major violations with respect to the presence or absence of lesions at baseline for the MoCA, Digit Symbol Substitution Test, Semantic Fluency Test, Trail Making Test A, Trail Making Test B and Trail Making Test B/A as outcomes. With regard to the models with CoCo score as outcome, there was some indication of potential violation of the proportional hazards assumption (p = 0.05 Model 1; p = 0.02 Model 2), suggesting the estimated average hazard ratios for the CoCo score may be less accurate.

The median follow-up time was 5.13 years (95% CI: 4.91–5.30). The incidence rate stratified by any brain lesion and the results of the association between any brain lesion and cognitive decline are presented in table 2. The incidence rate per 100 person-years for cognitive decline using the MoCA score was 3.64 (CI: 3.03–4.34) vs 1.82 (CI: 1.26–2.55) in patients with vs without any lesion. When using the CoCo score, incidence rates were 3.18 (CI: 2.60–3.84) with and 2.00 (CI: 1.41–2.76) without any brain lesion. Age- and sex-adjusted Cox proportional regression analysis revealed that the hazard of identifying a cognitive decline was estimated as 47% higher in patients who had lesions compared to those who did not on both the MoCA (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.47, 95% CI: 0.98–2.20) and the CoCo score (HR: 1.47, 95% CI: 0.98–2.20). After additional adjustments, the HRs (95% CI) for cognitive decline using the CoCo score and the MoCA were 1.45 (95% CI: 0.95–2.20, p = 0.08) and 1.29 (0.85–1.96, p = 0.23), respectively.

Table 2Association of presence of any brain lesion on baseline brain MRI with cognitive decline during follow-up using different neurocognitive tests. Substantial decline of cognitive function was defined, per cognitive test, as a decrease of one age- and education-normalised standard deviation (SD) from each patient’s baseline value. Model 1: adjusted for baseline age and sex; n = 1536. Model 2: additionally adjusted for body mass index, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, history of diabetes, history of stroke/transient ischaemic attack, history of systemic embolism, history of peripheral arterial disease, history of coronary artery disease, history of renal failure, smoking status, physical activity, alcohol consumption, oral anticoagulation, antiplatelet therapy, geriatric depression scale (>5 points = depression) and atrial fibrillation type. n = 1524.

| Baseline brain MRI | Number of events | Patient-years | Incidence rate per 100 patient-years (95% CI) | Cox regression model 1: HR (95% CI), p-value | Cox regression model 2: HR (95% CI), p-value | |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) | No lesions | 34 | 1864 | 1.82 (1.26–2.55) | Reference | Reference |

| Any lesions | 125 | 3434 | 3.64 (3.03–4.34) | 1.47 (0.98–2.20), p = 0.06 | 1.29 (0.85–1.96), p = 0.23 | |

| Cognitive Construct (CoCo) | No lesions | 37 | 1847 | 2.00 (1.41–2.76) | Reference | Reference |

| Any lesions | 107 | 3368 | 3.18 (2.60–3.84) | 1.47 (0.98–2.20), p = 0.06 | 1.45 (0.95–2.20), p = 0.08 | |

| Semantic Fluency Test (SFT) | No lesions | 115 | 2289 | 5.02 (4.15–6.03) | Reference | Reference |

| Any lesions | 273 | 4104 | 6.65 (5.89–7.49) | 1.27 (1.01–1.61), p = 0.04 | 1.28 (1.01–1.64), p = 0.04 | |

| Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST) | No lesions | 34 | 1856 | 1.83 (1.27–2.56) | Reference | Reference |

| Any lesions | 105 | 3403 | 3.09 (2.52–3.74) | 1.51 (1.00–2.28), p = 0.05 | 1.57 (1.02–2.40), p = 0.04 | |

| Trail Making Test (TMT) A | No lesions | 96 | 1709 | 5.62 (4.55–6.86) | Reference | Reference |

| Any lesions | 165 | 3282 | 5.03 (4.29–5.86) | 0.93 (0.70–1.22), p = 0.58 | 0.91 (0.69–1.21), p = 0.52 | |

| Trail Making Test (TMT) B | No lesions | 79 | 1770 | 4.46 (3.53–5.56) | Reference | Reference |

| Any lesions | 163 | 3267 | 4.99 (4.25–5.82) | 1.09 (0.81–1.46), p = 0.56 | 1.13 (0.83–1.52), p = 0.44 | |

| Trail Making Test (TMT) B/A | No lesions | 129 | 1641 | 7.86 (6.56–9.34 ) | Reference | Reference |

| Any lesions | 308 | 2974 | 10.36 (9.23–11.58) | 1.16 (0.93–1.45), p = 0.19 | 1.16 (0.92–1.46), p = 0.21 |

CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

The results of our secondary endpoint tests (Trail Making Tests A and B, Digit Symbol Substitution Test, Semantic Fluency Test) are presented in table 2. The incidence rates per 100 person-years were 6.65 (CI: 5.89–7.49) vs 5.02 (CI: 4.15–6.03) for the Semantic Fluency Test, and 3.09 (2.52–3.74) vs 1.83 (1.27–2.56) for the Digit Symbol Substitution Test in patients with vs without brain lesions, respectively. In an age- and sex-adjusted model, the HRs (95% CI) for cognitive decline defined by the Semantic Fluency Test and the Digit Symbol Substitution Test were 1.27 (1.01–1.61, p = 0.04) and 1.51 (1.00–2.28, p = 0.05), respectively. After multivariable adjustment, the association of any brain lesion with cognitive decline as defined by the Semantic Fluency Test and the Digit Symbol Substitution Test was only slightly modified with HRs (95% CI) of 1.28 (1.01–1.64, p = 0.04) and 1.57 (1.02–2.40, p = 0.04), respectively. There was no significant association of any brain lesion with cognitive decline as defined by the Trail Making Test A, Trail Making Test B or Trail Making Test B/A (table 2).

Detailed information concerning atrial fibrillation interventions at baseline are shown in table S1. Excluding history of stroke as an adjusting variable and adding atrial fibrillation interventions at baseline did not substantially affect the effect sizes, as is shown in appendix tables S3 and S4. Moreover, p for interaction revealed no significant effect modification of the MoCA score at baseline on the association between the presence of brain lesions and cognitive decline (appendix table S5). The additional analyses exploring the survival bias revealed that the effect sizes were slightly changed for both scenarios 1 and 2. However, overall, they go in the same direction as the effect sizes of the original analysis (appendix figure S1, see also appendix table S6 for baseline characteristics stratified according to the presence/absence of events).

In an unselected atrial fibrillation population with the vast majority on oral anticoagulation, the presence of brain lesions was not associated with a higher risk of cognitive decline using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) or the Cognitive Construct (CoCo) score over a median follow-up time of 5.13 years. However, compared to patients without any brain lesions, patients with lesions on baseline MRI had an associated higher risk of cognitive decline over time in more specific cognitive tests.

Based on the findings of the present analysis, it seems likely that brain lesions amplify the risk of cognitive decline in atrial fibrillation patients in some of the measured cognitive functions. This is in line with another study that showed a doubled risk of dementia and decline of cognitive functioning in patients with prevalent covert brain infarcts on brain MRI [23]. Even though the majority of patients in both groups (i.e. with and without brain lesions) was anticoagulated, a residual risk of cognitive decline remained for some of the cognitive functions. This finding is in line with a previous study that found that anticoagulation decreased the risk of dementia, yet with a considerable residual risk not affected by anticoagulation [24]. These results support both the theory that ischaemic brain lesions contribute to cognitive decline and, further, that additional mechanisms are at play. It is therefore crucial to identify such patients at high risk and to find other treatment strategies complementary to anticoagulation.

In the present analysis, we used a variety of different cognitive tests. With this wide panel of cognitive tests, we were able to investigate a differential effect of brain lesions on different cognitive functions. Using the Digit Symbol Substitution Test, we found a significant association of any brain lesion with cognitive decline. The Digit Symbol Substitution Test measures psychomotor speed and overall cognitive operations [25]. Slowing in psychomotor speed is thought to originate from the disconnection of fibres in different brain regions, often due to white matter lesions [26]. As white matter lesions are highly present in our brain lesion group, this may be an explanation for the observed differences. Another explanation could be that white matter lesions might be particularly distributed to brain areas with less redundancy and functional reserve. We did not find any significant results using the Trail Making Test A, which assesses psychomotor speed as well [18]. The Digit Symbol Substitution Test measures other cognitive functions besides psychomotor speed, e.g. executive functions [25, 27, 28]. Thus, it could also be possible that executive functions were affected in our patients.

Interestingly, we found the highest number of patients with cognitive decline using the Semantic Fluency Test and the Trail Making Test B/A. In patients with brain lesions, we also found a significant association between the presence of brain lesions and a higher risk of cognitive decline when using the Semantic Fluency Test. Both the Trail Making Test B/A and the Semantic Fluency Test mainly assess executive functions [17, 29]. Moreover, atrial fibrillation has previously been associated with a decline in executive functions [30]. Executive functions are predominantly located in the prefrontal cortex [31], which has been shown to be a particularly vulnerable area of the brain [32]. Impaired executive functions can critically impact everyday life [33]. Our findings emphasise the importance of differential cognitive testing in atrial fibrillation patients, in particular in those patients with known or at high risk of brain lesions. The Semantic Fluency Test, for example, is a very short and simple test, which has the additional advantage that it can be administered by phone, and does not necessitate an in-person visit. If abnormal test results are detected, impaired cognitive functions (such as executive functions) could then be improved with specific training [33].

Using the MoCA and the CoCo score, we found no significant association between brain lesions and a higher risk of cognitive decline. However, the MoCA and the CoCo test a broader array of cognitive qualities. Given the differential effects of brain lesions on cognitive functions, it is likely that these sum tests are less sensitive due to the possibility of weaknesses in some of the tested cognitive functions being compensated by strengths in others.

Possible clinical implications of our findings could be the early identification of atrial fibrillation patients with brain lesions and thus at high risk of cognitive decline, and the incorporation of cognitive assessments for these patients. Due to the limitations of widespread brain MRI screening, other non-invasive risk assessment strategies are necessary. As previously shown, a combination of biomarkers and clinical variables performed quite well in identifying patients at high risk of silent brain infarcts [34]. Of course, such risk assessments still need further refinement and extension to other types of brain lesions, including microbleeds and white matter lesions. But it would offer another possibility for identifying atrial fibrillation patients at high risk of cognitive decline.

Once patients are identified as being at high risk, preventive measures should be introduced, many of which are also recommended by the Atrial fibrillation Better Care (ABC) holistic pathway [7]. This thus underlines the necessity of a holistic approach for the management of atrial fibrillation patients. Early rhythm control may improve brain perfusion by restoring sinus rhythm, possibly reduce ischaemic brain lesions and thus potentially lead to better cognitive functioning [35–37]. In addition, aggressive management of cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities should be addressed. In our population, the better control of hypertension was associated with a lower presence of various brain lesions [38]. Additionally, stronger or additional anticoagulation including antiplatelets might be beneficial in selected high-risk patients [39]. And finally, in patients with cognitive decline, such as impaired executive functions, specific cognitive training programmes should be considered to preserve and/or improve cognitive function in the long term.

The strengths of this study are the long-term observation period and the large sample size of well-characterised patients with a standardised brain MRI and a battery of repeated standardised cognitive tests assessing different cognitive functions. The generalisability of our findings may be limited due to the predominance of male participants in our study population and the fact that most study participants were of European origin. Moreover, though we previously showed that the CoCo score, which was developed within the Swiss-AF study, is more sensitive than the MoCA score [19], it nevertheless needs further validation. Finally, data of the present analysis were interval-censored. Censoring occurred at the last available visit. If patients died or were lost to follow-up, we do not know how their cognition developed between the last visit and and, e.g., their death.

In our study, patients with brain lesions (clinically overt or covert) on baseline MRI had a higher associated risk of cognitive function loss over time. It seems that rather than affecting overall cognitive functioning, very specific cognitive functions are more likely to be affected.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of restrictions imposed by the Ethics Committee. Requests to access the datasets or the analysis code should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Swiss-AF investigators

University Hospital Basel and Basel University: Stefanie Aeschbacher, Katalin Bhend, Steffen Blum, Leo H. Bonati, Désirée Carmine, David Conen, Ceylan Eken, Urs Fischer, Corinne Girroy, Elisa Hennings, Philipp Krisai, Michael Kühne, Nina Mäder, Christine Meyer-Zürn, Pascal B. Meyre, Andreas U. Monsch, Luke Mosher, Christian Müller, Stefan Osswald, Rebecca E. Paladini, Raffaele Peter, Adrian Schweigler, Anne Springer, Christian Sticherling, Thomas Szucs, Gian Völlmin. Principal Investigator: Stefan Osswald; Local Principal Investigator: Michael Kühne.

University Hospital Bern: Faculty: Drahomir Aujesky, Juerg Fuhrer, Laurent Roten, Simon Jung, Heinrich Mattle; Research fellows: Seraina Netzer, Luise Adam, Carole Elodie Aubert, Martin Feller, Axel Loewe, Elisavet Moutzouri, Claudio Schneider; Study nurses: Tanja Flückiger, Cindy Groen, Lukas Ehrsam, Sven Hellrigl, Alexandra Nuoffer, Damiana Rakovic, Nathalie Schwab, Rylana Wenger, Tu Hanh Zarrabi Saffari. Local Principal Investigators: Nicolas Rodondi, Tobias Reichlin.

Stadtspital Triemli Zurich: Christopher Beynon, Roger Dillier, Michèle Deubelbeiss, Franz Eberli, Christine Franzini, Isabel Juchli, Claudia Liedtke, Samira Murugiah, Jacqueline Nadler, Thayze Obst, Jasmin Roth, Fiona Schlomowitsch, Xiaoye Schneider, Katrin Studerus, Noreen Tynan, Dominik Weishaupt. Local Principal Investigator: Andreas Müller.

Kantonspital Baden: Corinne Friedli, Silke Kuest, Karin Scheuch, Denise Hischier, Nicole Bonetti, Alexandra Grau, Jonas Villinger, Eva Laube, Philipp Baumgartner, Mark Filipovic, Marcel Frick, Giulia Montrasio, Stefanie Leuenberger, Franziska Rutz. Local Principal Investigator: Jürg-Hans Beer.

Cardiocentro Lugano: Angelo Auricchio, Adriana Anesini, Cristina Camporini, Maria Luce Caputo, Rebecca Peronaci, Francois Regoli, Martina Ronchi. Local Principal Investigator: Giulio Conte.

Kantonsspital St. Gallen: Roman Brenner, David Altmann, Karin Fink, Michaela Gemperle. Local Principal Investigator: Peter Ammann.

Hôpital Cantonal Fribourg: Mathieu Firmann, Sandrine Foucras, Martine Rime. Local Principal Investigator: Daniel Hayoz.

Luzerner Kantonsspital: Benjamin Berte, Kathrin Bühler, Virgina Justi, Frauke Kellner-Weldon, Melanie Koch, Brigitta Mehmann, Sonja Meier, Myriam Roth, Andrea Ruckli-Kaeppeli, Ian Russi, Kai Schmidt, Mabelle Young, Melanie Zbinden. Local Principal Investigator: Richard Kobza.

Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale Lugano: Elia Rigamonti, Carlo Cereda, Alessandro Cianfoni, Maria Luisa De Perna, Jane Frangi-Kultalahti, Patrizia Assunta Mayer Melchiorre, Anica Pin, Tatiana Terrot, Luisa Vicari. Local Principal Investigator: Giorgio Moschovitis.

University Hospital Geneva: Georg Ehret, Hervé Gallet, Elise Guillermet, Francois Lazeyras, Karl-Olof Lovblad, Patrick Perret, Philippe Tavel, Cheryl Teres. Local Principal Investigator: Dipen Shah.

University Hospital Lausanne: Nathalie Lauriers, Marie Méan, Sandrine Salzmann, Jürg Schläpfer. Local Principal Investigator: Alessandra Pia Porretta.

Bürgerspital Solothurn: Andrea Grêt, Jan Novak, Sandra Vitelli. Local Principal Investigator: Frank-Peter Stephan.

Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale Bellinzona: Jane Frangi-Kultalahti, Augusto Gallino, Luisa Vicari. Local Principal Investigator: Marcello Di Valentino.

University of Zurich/University Hospital Zurich: Helena Aebersold, Fabienne Foster, Matthias Schwenkglenks.

Medical Image Analysis Center AG Basel: Marco Düring, Tim Sinnecker, Anna Altermatt, Michael Amann, Petra Huber, Manuel Hürbin, Esther Ruberte, Alain Thöni, Jens Würfel, Vanessa Zuber.

Clinical Trial Unit Basel: Michael Coslovsky (Head), Pia Neuschwander, Patrick Simon, Olivia Wunderlin.

Schiller AG Baar: Ramun Schmid, Christian Baumann.

The Swiss‐AF study is supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant numbers 33CS30_148474, 33CS30_177520, 32473B_176178, and 32003B_197524), the Swiss Heart Foundation, the Foundation for CardioVascular Research Basel (FCVR) and the University of Basel.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. – Aeschbacher: received a speaker fee from Roche Diagnostics. – Auricchio: is a consultant for Boston Scientific, Backbeat, Biosense Webster, Cairdac, Corvia, Daiichi-Sankyo, Medtronic, Merit, Microport CRM, Philips and V-Wave. He has received speaker fees from Daiichi-Sankyo, Boston Scientific, Biosense Webster, Medtronic, Microport CRM and Philips. He also participates in clinical trials for Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Microport CRM and Zoll Medical. He also holds intellectual properties with the following: Boston Scientific, Biosense Webster and Microport CRM. – Bonati: received grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (PBBSB-116873, 33CM30-124119, 32003B-156658, 32003B-197524; Berne, Switzerland), the Swiss Heart Foundation (Berne, Switzerland) and the University of Basel (Basel, Switzerland). He received an unrestricted research grant from AstraZeneca, and consultancy or advisory board fees or speaker’s honoraria from Amgen, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Claret Medical, and travel grants from AstraZeneca and Bayer. – Conen: received speaker fees from Servier and BMS/Pfizer, and consulting fees from Roche Diagnostics and Trimedics, all outside of the current work. – Krisai: reports grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Swiss Heart Foundation, the Foundation for CardioVascular Research Basel, the Machaon Foundation and the ProPatient Foundation, outside of the submitted work, and speaker fees from BMS, Pfizer and Biosense Webster. – Kühne: reports personal fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer BMS, Daiichi Sankyo, Medtronic, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Johnson&Johnson and Roche, grants from Bayer, Pfizer, Boston Scientific, BMS, Biotronik, Daiichi Sankyo. – Moschovitis: received advisory board and/or speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Gebro Pharma, Novartis and Vifor, all outside of the submitted work. – Osswald: received research grants from the Swiss Heart Foundation, the Foundation for CardioVascular Research Basel, the Swiss National Science Foundation and from Roche. He has also received educational and speaker office grants from Roche, Bayer, Novartis, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo and Pfizer. – Rodondi: received a grant from the Swiss Heart Foundation. – Beer: reports grants from the Swiss National Foundation of Science, The Swiss Heart Foundation, grants from Bayer, lecture fees from Sanofi Aventis and Amgen, to the institution outside the submitted work. – Sinnecker: is an employee of the Medical Image Analysis Centre Basel, Switzerland. – The other authors stated that they have no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

1. Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, Brodaty H, Fratiglioni L, Ganguli M, et al.; Alzheimer’s Disease International. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. 2005 Dec;366(9503):2112–7.

2. Nichols E, Szoeke CE, Vollset SE, Abbasi N, Abd-Allah F, Abdela J, et al.; GBD 2016 Dementia Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019 Jan;18(1):88–106.

3. Prince MJ. World Alzheimer report 2015: the global impact of dementia. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2015.pdf

4. Raz L, Knoefel J, Bhaskar K. The neuropathology and cerebrovascular mechanisms of dementia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016 Jan;36(1):172–86.

5. Ott A, Breteler MM, de Bruyne MC, van Harskamp F, Grobbee DE, Hofman A. Atrial fibrillation and dementia in a population-based study. The Rotterdam Study. Stroke. 1997 Feb;28(2):316–21. <doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.28.2.316

6. Diener HC, Hart RG, Koudstaal PJ, Lane DA, Lip GY. Atrial Fibrillation and Cognitive Function: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Feb;73(5):612–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.077

7. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist C, et al.; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021 Feb;42(5):373–498.

8. Koh YH, Lew LZ, Franke KB, Elliott AD, Lau DH, Thiyagarajah A, et al. Predictive role of atrial fibrillation in cognitive decline: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 2.8 million individuals. Europace. 2022 Sep;24(8):1229–39.

9. Conen D, Rodondi N, Mueller A, Beer J, Auricchio A, Ammann P, et al. Design of the Swiss Atrial Fibrillation Cohort Study (Swiss-AF): structural brain damage and cognitive decline among patients with atrial fibrillation. Swiss Med Wkly. 2017 Jul;147(2728):w14467.

10. Conen D, Rodondi N, Müller A, Beer JH, Ammann P, Moschovitis G, et al.; Swiss-AF Study Investigators. Relationships of Overt and Silent Brain Lesions With Cognitive Function in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Mar;73(9):989–99.

11. Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, Decarli C, Greenberg SM, Iadecola C, et al.; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, and Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2011 Sep;42(9):2672–713.

12. Silbert LC, Nelson C, Howieson DB, Moore MM, Kaye JA. Impact of white matter hyperintensity volume progression on rate of cognitive and motor decline. Neurology. 2008 Jul;71(2):108–13.

13. Kühne M, Krisai P, Coslovsky M, Rodondi N, Müller A, Beer JH, et al.; Swiss-AF Investigators. Silent brain infarcts impact on cognitive function in atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2022 Jun;43(22):2127–35.

14. Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, Schotten U, Savelieva I, Ernst S, et al.; European Heart Rhythm Association; European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2010 Oct;31(19):2369–429.

15. Fazekas F, Chawluk JB, Alavi A, Hurtig HI, Zimmerman RA. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer’s dementia and normal aging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987 Aug;149(2):351–6.

16. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005 Apr;53(4):695–9.

17. Arbuthnott K, Frank J. Trail making test, part B as a measure of executive control: validation using a set-switching paradigm. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2000 Aug;22(4):518–28. doi: https://doi.org/10.1076/1380-3395(200008)22:4;1-0;FT518

18. Bowie CR, Harvey PD. Administration and interpretation of the Trail Making Test. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(5):2277–81.

19. Springer A, Monsch AU, Dutilh G, Coslovsky M, Kievit RA, Bonati LH, et al.; Swiss-AF Study Investigators. A factor score reflecting cognitive functioning in patients from the Swiss Atrial Fibrillation Cohort Study (Swiss-AF). PLoS One. 2020 Oct;15(10):e0240167.

20. Wang S, Blazer DG. Depression and cognition in the elderly. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2015;11(1):331–60. doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112828

21. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982-1983;17(1):37–49.

22. Laudisio A, Antonelli Incalzi R, Gemma A, Marzetti E, Pozzi G, Padua L, et al. Definition of a Geriatric Depression Scale cutoff based upon quality of life: a population-based study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018 Jan;33(1):e58–64.

23. Vermeer SE, Prins ND, den Heijer T, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Silent brain infarcts and the risk of dementia and cognitive decline. N Engl J Med. 2003 Mar;348(13):1215–22.

24. Friberg L, Andersson T, Rosenqvist M. Less dementia and stroke in low-risk patients with atrial fibrillation taking oral anticoagulation. Eur Heart J. 2019 Jul;40(28):2327–35.

25. Rosano C, Perera S, Inzitari M, Newman AB, Longstreth WT, Studenski S. Digit Symbol Substitution test and future clinical and subclinical disorders of cognition, mobility and mood in older adults. Age Ageing. 2016 Sep;45(5):688–95.

26. Wang S, Jiaerken Y, Yu X, Shen Z, Luo X, Hong H, et al. Understanding the association between psychomotor processing speed and white matter hyperintensity: A comprehensive multi-modality MR imaging study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2020 Feb;41(3):605–16.

27. Jaeger J. Digit Symbol Substitution Test: The Case for Sensitivity Over Specificity in Neuropsychological Testing. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018 Oct;38(5):513–9.

28. Baudouin A, Clarys D, Vanneste S, Isingrini M. Executive functioning and processing speed in age-related differences in memory: contribution of a coding task. Brain Cogn. 2009 Dec;71(3):240–5.

29. Torralva T, Laffaye T, Báez S, Gleichgerrcht E, Bruno D, Chade A, et al. Verbal Fluency as a Rapid Screening Test for Cognitive Impairment in Early Parkinson’s Disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;27(3):244–7.

30. Chen LY, Norby FL, Gottesman RF, Mosley TH, Soliman EZ, Agarwal SK, et al. Association of Atrial Fibrillation With Cognitive Decline and Dementia Over 20 Years: The ARIC-NCS (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive Study). J Am Heart Assoc. 2018 Mar;7(6):e007301.

31. Alvarez JA, Emory E. Executive function and the frontal lobes: a meta-analytic review. Neuropsychol Rev. 2006 Mar;16(1):17–42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-006-9002-x

32. Tullberg M, Fletcher E, DeCarli C, Mungas D, Reed BR, Harvey DJ, et al. White matter lesions impair frontal lobe function regardless of their location. Neurology. 2004 Jul;63(2):246–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1212/01.WNL.0000130530.55104.B5

33. Diamond A, Ling DS. Conclusions about interventions, programs, and approaches for improving executive functions that appear justified and those that, despite much hype, do not. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2016 Apr;18:34–48.

34. Krisai P, Eken C, Aeschbacher S, Coslovsky M, Rolny V, Carmine D, et al.; Swiss-AF study investigators. Biomarkers, Clinical Variables, and the CHA2DS2-VASc Score to Detect Silent Brain Infarcts in Atrial Fibrillation Patients. J Stroke. 2021 Sep;23(3):449–52.

35. Bunch TJ, Steinberg BA. Rhythm Matters When It Comes to Brain Perfusion. JACC. Clinical electrophysiology. 2022;8(11):1378-1380.

36. Saglietto A, Scarsoglio S, Canova D, Roatta S, Gianotto N, Piccotti A, et al. Increased beat-to-beat variability of cerebral microcirculatory perfusion during atrial fibrillation: a near-infrared spectroscopy study. Europace. 2021 Aug;23(8):1219–26.

37. Savelieva I, Fumagalli S, Kenny RA, Anker S, Benetos A, Boriani G, et al. EHRA expert consensus document on the management of arrhythmias in frailty syndrome, endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), Latin America Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS), and Cardiac Arrhythmia Society of Southern Africa (CASSA). Europace. 2023 Apr;25(4):1249–76.

38. Aeschbacher S, Blum S, Meyre PB, Coslovsky M, Vischer AS, Sinnecker T, et al. Blood Pressure and Brain Lesions in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. Hypertens (Dallas, Tex 1979). 2021 Feb;77(2):662-671. doi: .

39. Lane DA, Raichand S, Moore D, Connock M, Fry-Smith A, Fitzmaurice DA; Steering Committee. Combined anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy for high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2013 Jul;17(30):1–188.

The appendix is available in the pdf version of the article at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.4059.