Exploring the real-world management of catheter-associated

urinary tract infections by Swiss general practitioners and urologists:

insights from an online survey

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.3933

Iris Züntiab,

Emilio Arbelaezab,

Sarah Tschudin-Sutterbc,

Andreas Zellerbd,

Florian S. Halbeisenbe,

Hans-Helge

Seifertab,

Kathrin Bauschab

a Department of Urology, University Hospital Basel,

Basel, Switzerland

b University

of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

c Division

of Infectious Diseases and Hospital Epidemiology, University Hospital Basel,

Basel, Switzerland

d Centre

for Primary Health Care, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

e Surgical Outcome Research Center, Department of

Clinical Research, University Hospital Basel and University of Basel, Basel,

Switzerland

Summary

AIM: To assess and compare the real-world

management of catheters and catheter-associated urinary tract infections

(CAUTI) among Swiss general practitioners and urologists, encompassing diagnosis,

treatment and prophylaxis.

METHODS: An anonymised online

questionnaire was distributed among Swiss general practitioners and urologists between

January

and October 2023 via the networks of Sentinella and the Swiss Association of

Urology. The questionnaire consisted of questions on catheter management,

including diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of CAUTI. Analysis was performed

by discipline. Fisher’s exact test was applied for comparisons (statistical

significance with p <0.05).

RESULTS: Out of 175 participating physicians,

the majority were involved in catheter management. Urologists exhibited

significantly higher levels of competence as compared to general practitioners (67.1%

vs 20.9%).

Although no significant differences were observed regarding diagnostic

approaches between disciplines, unrecommended diagnostic methods were

frequently applied. general practitioners reported that they treated non-febrile CAUTI

for longer

durations, while urologists indicated that they treated febrile CAUTI longer.

Additionally, the use of fluoroquinolones was more prevalent among general practitioners

compared

to urologists, while prophylactic measures were more frequently applied by

urologists.

CONCLUSIONS: Catheter and CAUTI management

entail significant uncertainty for general practitioners. CAUTI management varied

notably between

general practitioners and urologists in terms of treatment and prophylaxis. The use

of non-recommended

diagnostic approaches and drugs was common. This trend, along with

inappropriate diagnostic methods and prophylaxis, may increase antimicrobial

resistance and CAUTI morbidity. The study emphasises the necessity for diagnostic

and antimicrobial stewardship interventions, and proper training in CAUTI

management for general practitioners and urologists.

Abbreviations

- CAUTI:

-

catheter-associated urinary tract infections

- EAU:

-

European Association of Urology

- EAUN:

-

European Association of

Urology Nurses

Introduction

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are one of the

most common diseases, affecting more than 150 million people worldwide every

year [1]. Urinary tract infections rank among the top four most prevalent

nosocomial infections; 70–80% of urinary tract infections are catheter-associated

urinary tract infections

(CAUTIs) [2], which significantly increases morbidity and

mortality [3]. This imposes a substantial burden on the

healthcare system, leading to prolonged hospital stays and escalated costs [3].

Presence of a urinary catheter and duration of

catheterisation are the main risk factors for catheter-associated complications

[4]. Furthermore, studies indicate that between 21%

and 65% of all catheter insertions are not necessary [5, 6] and that prolonged catheterisation

without

indication is common [7].

Interventions such as confirming the need for catheterisation,

daily evaluation of this need and education on catheter management

significantly decrease catheter utilisation and non-infectious complications in

the hospital setting [2, 4]. These measures have also contributed to the

reduction of CAUTIs [2, 8]. However, there are patients in whom permanent

catheterisation is indicated but in whom such measures cannot be applied. This

cohort of patients is usually frail and has additional risk factors for infectious

complications such as immunosuppression, diabetes, advanced age or immobilisation

[9]. Therefore, comprehensive guidelines and

corresponding training for catheter and CAUTI management are urgently needed.

This patient cohort is primarily cared for by

general practitioners and urologists. Their decision-making is usually

guided by experience und guideline recommendations. Adherence to guideline

recommendations and antimicrobial stewardship programmes significantly reduce

the use of antimicrobials and the development of antimicrobial resistance [10]. Currently

there are various

guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of uncomplicated urinary tract

infection [11–13] but only a few target urinary tract infections in catheterised

patients [11, 14–16]. Compared to urinary tract infections, the real-world management

of CAUTI is complicated by atypical symptoms, misleading diagnostic measures,

unclear guidance for treatment decisions and a lack of evidence on prophylaxis [17].

To establish a foundation for future antimicrobial stewardship

programmes and recommendations, our study aimed to

assess and compare real-world management of catheters and CAUTIs among Swiss

general practitioners and urologists encompassing diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis.

Material and methods

Study design and setting

A web-based, anonymous survey was conducted

among general practitioners and urologists across Switzerland. In January 2023, the

survey,

hosted on the REDCap platform, was disseminated via the networks of Sentinella,

a surveillance system operated by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (Bundesamt

für Gesundheit) for gathering epidemiological data in family medicine [18], and the Swiss Association

of Urology (Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Urologie) through email. Participants were encouraged to

further distribute the survey within their respective institutions of general practitioners

and urologists,

with a follow-up reminder sent two weeks later.

The questionnaire comprised 6 demographic

questions, 3 about catheter management in general and 15 about CAUTIs.

Responses were structured with predefined options for most questions, while

some allowed for individual or multiple selections. The questionnaire was

provided in German, French and Italian, with the English version available in the

appendix.

Following the collection of baseline characteristics, participants

were queried about their involvement in catheter management. If respondents indicated

not being involved in catheter management, subsequent questions were omitted.

Incomplete questionnaires of participants who were involved in catheter

management were still included in the analysis. Participation was voluntary,

and to maintain anonymity no personal identifiers or written informed consent

were obtained from participants. Given the focus on general practitioners and urologists

and the absence

of patient data collection, ethical committee approval was deemed unnecessary

for this study. A study protocol has not been published or registered before.

The dataset can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Statistical analysis

We conducted descriptive statistical analyses

to summarise the collected data. Categorical variables were presented as counts

and corresponding proportions, while appropriate descriptive statistics were

chosen for continuous variables based on data distribution; given the

non-normal distribution, we reported median and range.

To compare

characteristics between disciplines, two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were

applied for continuous variables, while two-sided Fisher’s exact tests were used

for categorical variables to detect significant differences in proportions

between urologists and general practitioners. Furthermore, Fisher’s exact tests were

separately

applied to each survey question to uncover discipline-specific variations in

responses, with separate tests conducted for each answer category in questions

with multiple options.

We considered a p-value less than 0.05 as

statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R

statistical software (version 4.2.2, The R Foundation for Statistical

Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

In total, 175 questionnaires (93 general practitioners

and 82 urologists) were completed and 80% of them had no missing data. Seventeen

general practitioners indicated not being involved in catheter management and were

excluded from

further analysis. Urologists were younger than participating general practitioners

(table 1). The

majority of general practitioners and urologists reported that they replaced catheters

every 1–3

months, with urologists treating a higher number of patients with

catheter-related issues and more instances of CAUTIs (table 1). While

urologists generally expressed confidence in catheter management, over a

quarter of general practitioners did not feel competent in this area (table 1).

| Characteristic |

General practitioner (n = 93) |

Urology (n = 82) |

p-value |

Missing data |

| Age, median and range |

55 |

18–77 |

48 |

28–70 |

0.001 |

0 |

| Years of experience as a medical professional, median and range |

25 |

1–50 |

20 |

2–45 |

0.006 |

0 |

| Sex, n and % |

|

|

|

|

0.411 |

0 |

|

Female |

31 |

33.3% |

22 |

26.8% |

|

|

|

Male |

62 |

66.7% |

60 |

73.2% |

|

|

| Medical facility where you work, n and % |

|

|

|

|

<0.001* |

0 |

| General practitioner

practice |

93 |

100% |

|

|

|

|

|

Urological practice |

|

|

37 |

45.1% |

|

|

|

District hospital |

|

|

9 |

11.0% |

|

|

|

Cantonal hospital |

|

|

21 |

25.6% |

|

|

|

University hospital |

|

|

8 |

9.8% |

|

|

|

Rehabilitation hospital |

|

|

4 |

4.9% |

|

|

|

Other |

|

|

3 |

3.7% |

|

|

| Do you look after patients who are permanently supplied with a

urinary catheter? n and % |

|

|

|

|

<0.001* |

0 |

|

No |

17 |

18.3% |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Rarely |

40 |

43.0% |

1 |

1.2% |

|

|

|

Yes |

10 |

10.8% |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Yes and I change

transurethral |

5 |

5.4% |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Yes and I change

suprapubic |

1 |

1.1% |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Yes and I change both |

20 |

21.5% |

81 |

98.8% |

|

|

| At what interval do you usually perform catheter changes in

asymptomatic patients? n and % |

|

|

|

|

<0.001* |

17 |

|

<2 weeks |

|

|

1 |

1.2% |

|

|

|

2–4 weeks |

6 |

7.9% |

2 |

2.4% |

|

|

|

1–2 months |

33 |

43.4% |

41 |

50.0% |

|

|

|

2–3 months |

22 |

29.0% |

38 |

46.3% |

|

|

|

>3 months |

4 |

5.3% |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Only if needed |

11 |

14.5% |

0 |

|

<0.001* |

|

| During the past 12 months, how many patients with transurethral

and/or suprapubic catheters did you see on average per week for

catheter-related concerns? n and % |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<1 |

61 |

80.2% |

10 |

12.2% |

|

17 |

|

1–5 |

14 |

18.4% |

34 |

41.5% |

|

|

|

5–10 |

1 |

1.3% |

28 |

34.2% |

|

|

|

11–25 |

0 |

|

9 |

11.0% |

|

|

|

>50 |

0 |

|

1 |

1.2% |

|

|

| How often do you diagnose an urinary tract infection in a catheterised patient per

year? n and % |

|

|

|

|

0.089* |

24 |

|

<1/year |

19 |

25.7% |

14 |

18.2% |

|

|

|

1/year |

22 |

29.7% |

22 |

28.6% |

|

|

|

2–3/year |

22 |

29.7% |

19 |

24.7% |

|

|

|

4–5/year |

4 |

5.4% |

2 |

2.6% |

|

|

|

>5/year |

7 |

9.5% |

20 |

26.0% |

|

|

| Do you feel competent in managing catheters and recurrent

urinary tract infections in catheterised patients? n and % |

|

|

|

|

<0.001* |

25 |

|

No |

3 |

4.5% |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Rather no |

16 |

23.9% |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Rather yes |

34 |

50.8% |

24 |

32.9% |

|

|

|

Yes |

14 |

20.9% |

49 |

67.1% |

|

|

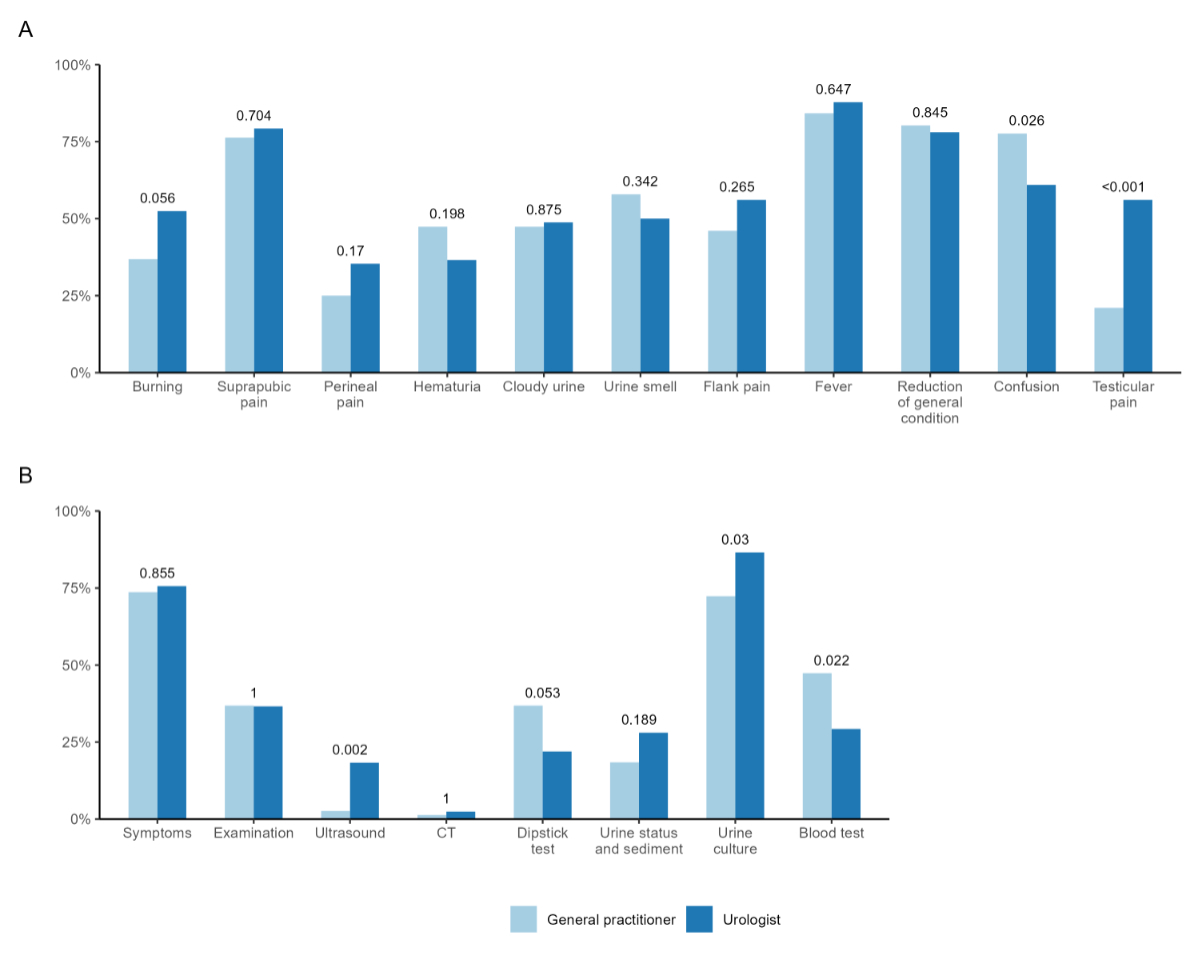

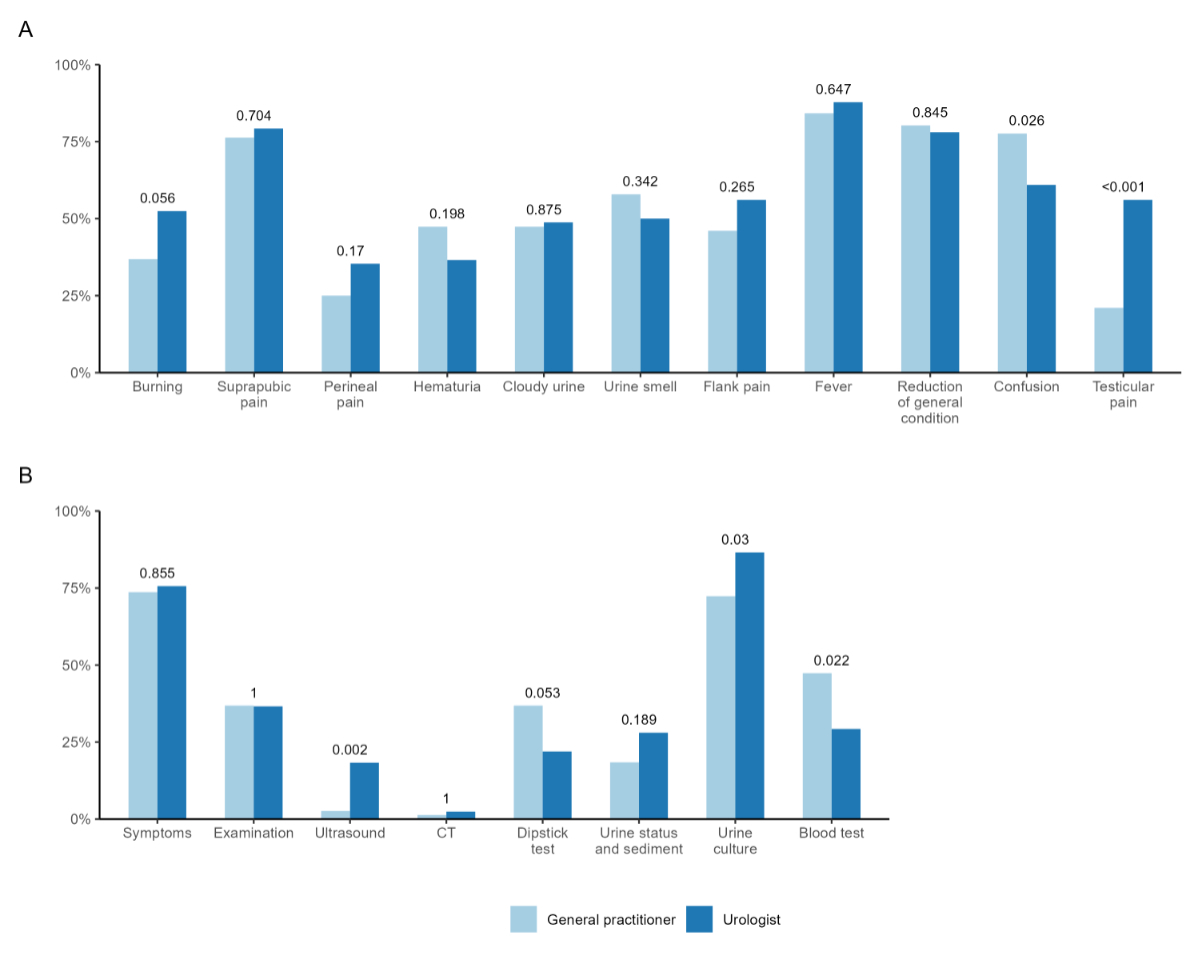

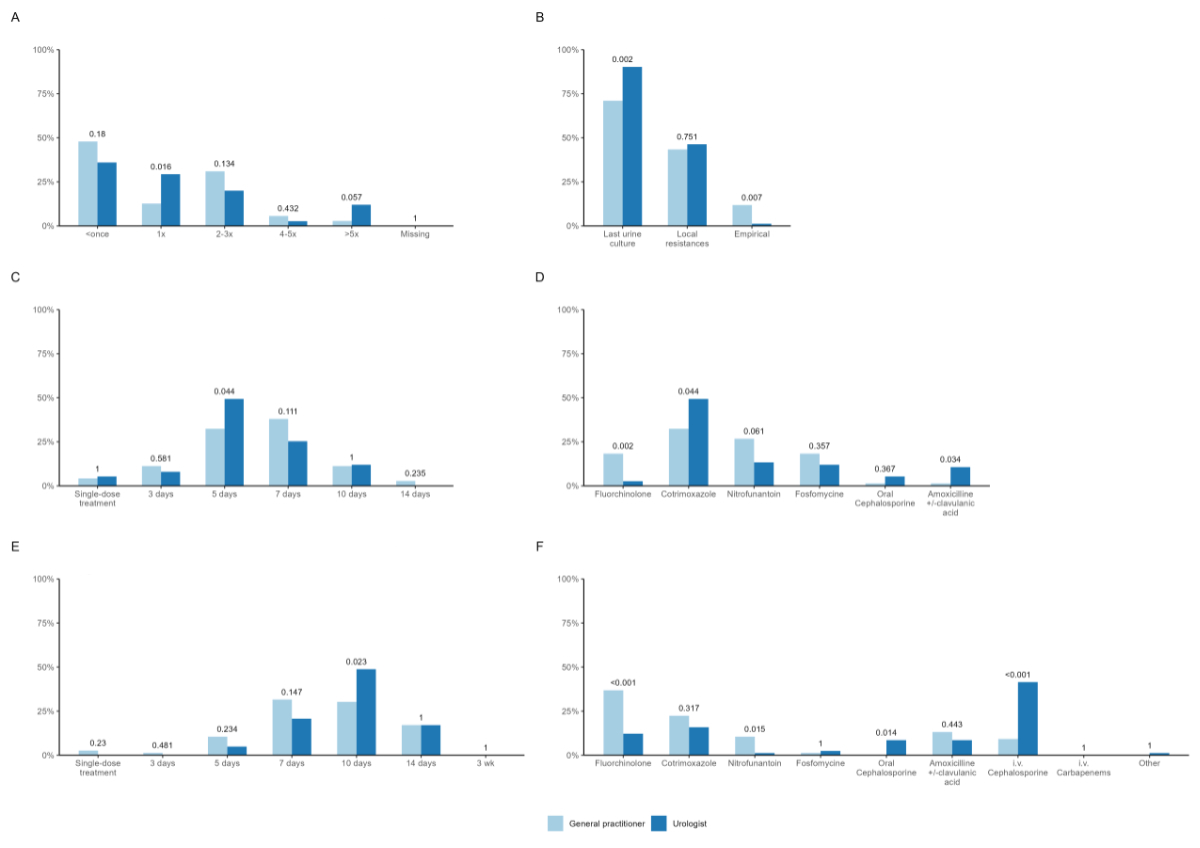

Figure 1 shows responses regarding CAUTI

diagnosis and compares respective disciplines. In terms of CAUTI symptoms,

there were only a few differences between disciplines except for confusion,

which was more frequently considered symptomatic by general practitioners, and testicular

pain,

which was seen as a typical symptom by urologists (figure 1A). The most

frequent methods used to diagnose CAUTI were symptoms and urine culture. In

both disciplines, dipstick test and urine status/sediment were often used to

diagnose CAUTI (figure 1B).

Figure 1Diagnosis of CAUTI. (A) Which signs/symptoms do you usually base your diagnose of an urinary tract infection

in a catheterised patient on? (B) How do you usually diagnose an urinary tract infection in a catheterised patient?

Answers depicted

by discipline (light blue, general practitioner; dark blue, urologists).

P-value based on available data, considered significant if ≤0.05. CT:

computed tomography.

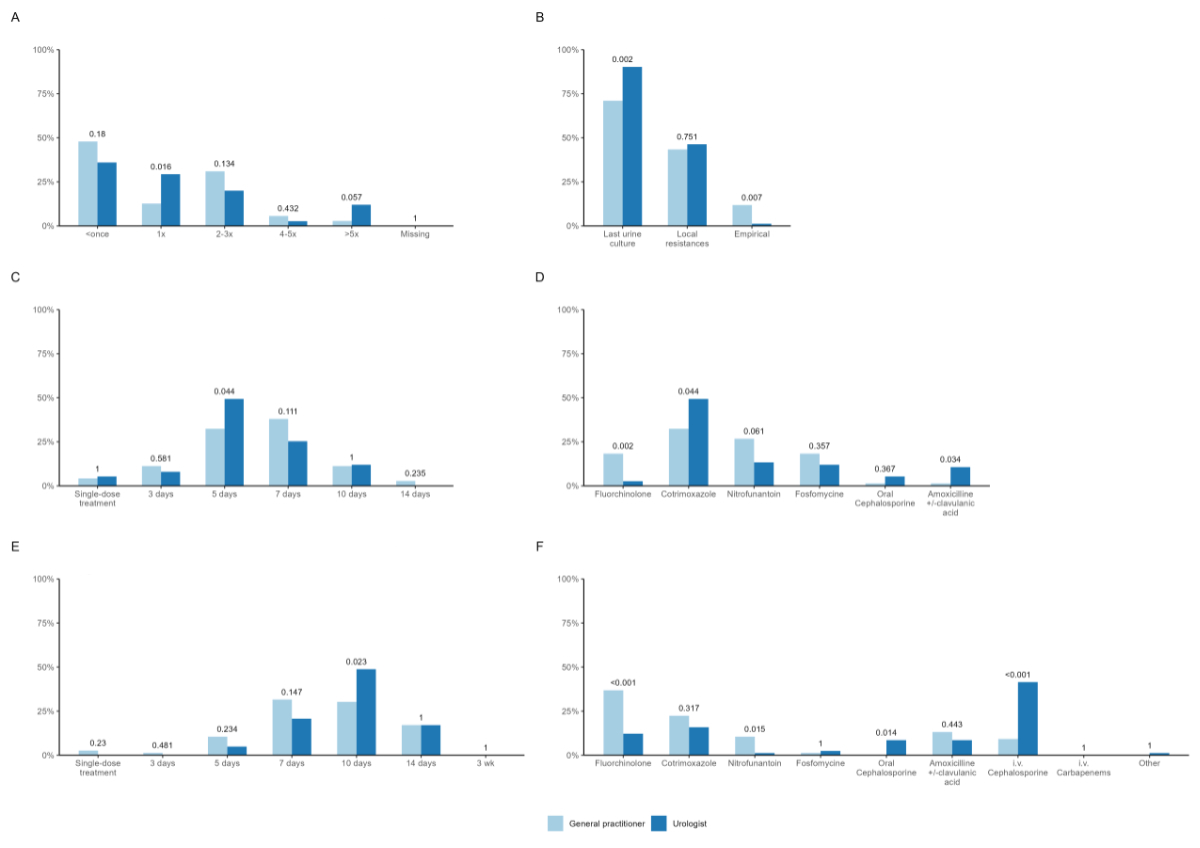

Regarding CAUTI treatment, the majority of urologists

and general practitioners stated that they treated a catheterised patient less than

once per year

with antibiotics (figure 2A). Choice of antibiotic was primarily based on the

last urine culture by both disciplines (figure 2B). In non-febrile CAUTI,

urologists indicated that they favoured treating patients for 5 days, while general

practitioners

indicated 7 days (figure 2C). Co-trimoxazole was reported to be the mainly

prescribed antibiotic by both disciplines. While fluoroquinolones were still

frequently applied by general practitioners (17.1%), they were barely used by urologists

(2.4%) (figure

2D). In febrile CAUTI, general practitioners declared that they treat for around 7–10

days and

urologists preferred to treat for 10 days (figure 2E). In contrast to

urologists, fluoroquinolones were reported to be the most frequently prescribed

antibiotics for febrile CAUTI by general practitioners (36.8%). Urologists’ main choice

was intravenous

(i.v.) cephalosporins (figure 2F).

Figure 2Treatment of CAUTI. (A) How often do you prescribe an antibiotic for an urinary tract infection per catheterised

patient per year? (B) How do you choose the antibiotic for empiric therapy? (C) How long do you usually treat catheterised patients with an antibiotic for a non-febrile

urinary tract infection in average? (D) Which antibiotic do you usually choose for the empirical therapy of a non-febrile

urinary tract infection? (E) How long do you usually treat catheterised patients with an antibiotic for a febrile

urinary tract infection in average? (F) Which antibiotic do you usually choose for the empirical therapy of a febrile urinary

tract infection? Answers depicted

by discipline (light blue, general practitioner; dark blue, urologists).

P-value based on available data, considered significant if ≤0.05. i.v.: intravenous.

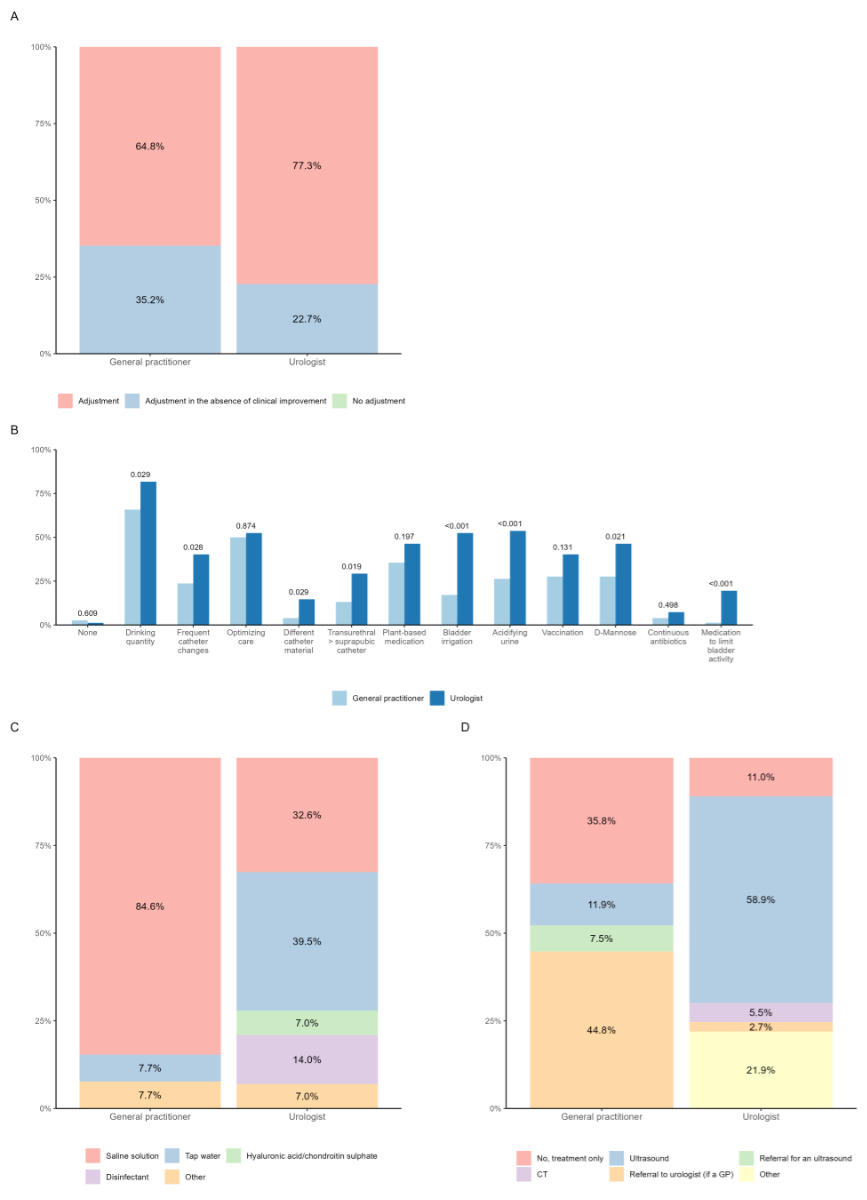

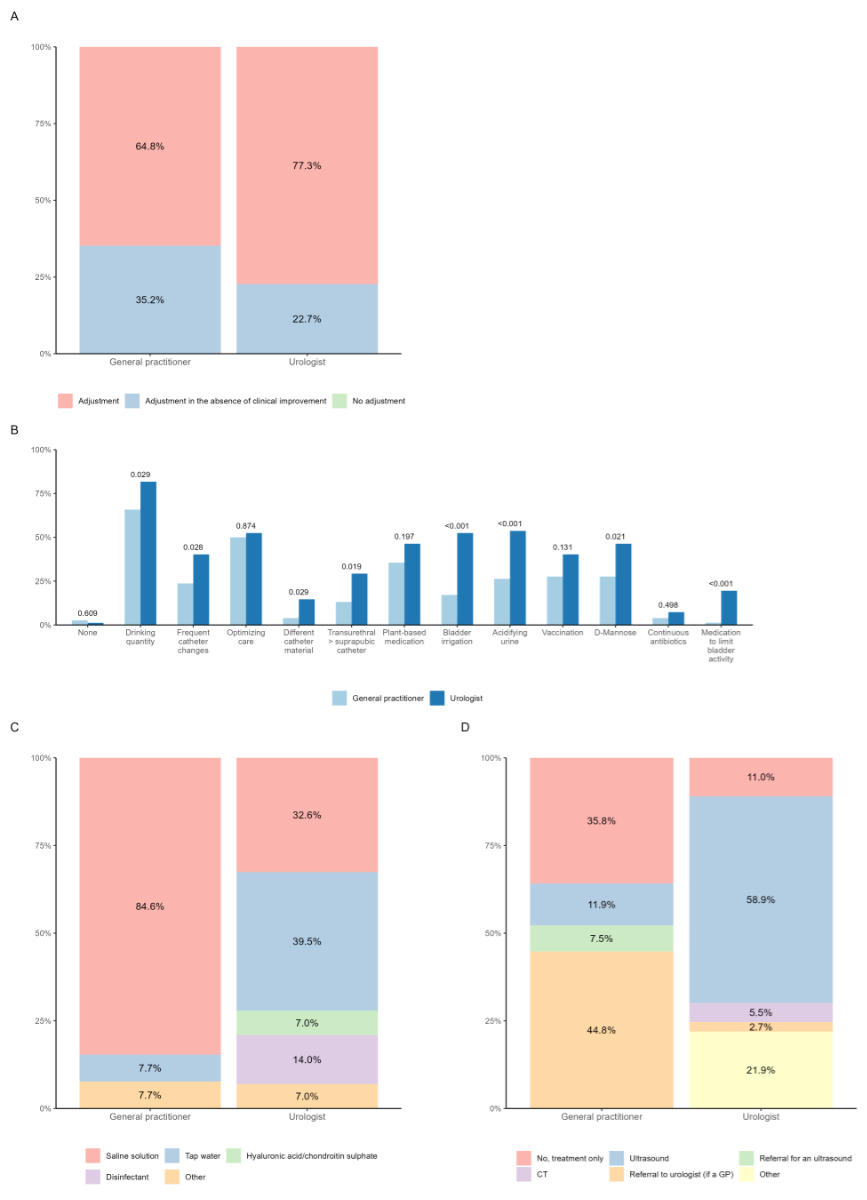

After empirical treatment, most questionees

would adjust the administered antibiotic according to urine culture (figure 3A,

table S1). Increasing fluid intake emerged as the primary prophylactic measure

(see figure 3B). With the exception of optimising catheter care and

vaccination, urologists statistically applied all prophylactic measures more

frequently (see figure 3B). If bladder irrigation was performed, general practitioners

reported preferring

saline solution and urologists tap water (figure 3C, table S2). General practitioners

indicated that

they refer patients to urologists for further management. Urologists performed

an ultrasound instead (figure 3D, table S3).

Figure 3Prophylaxis of CAUTI. (A) What do you usually do after receiving the results of the urine culture when the

detected germ proves to be resistant to the antibiotic administered? (B) Do you usually enact additional measures to reduce recurrent urinary tract infection

in catheterised patients? (C) If you perform regular bladder irrigation, which fluid do you use for this? (D) Do you initiate further diagnostic measures for recurrent urinary tract infection

in catheterised patients? Answers

depicted by discipline (light blue, general practitioner; dark blue, urologist).

P-value based on available data, considered significant if ≤0.05. CT:

computed tomography; GP: general practitioner.

Discussion

This study is the first real-world assessment of catheter and

CAUTI management among Swiss general practitioners and urologists. It reveals that

despite

uncertainties among general practitioners regarding CAUTI management, the diagnostic

approach for

CAUTI is similar between general practitioners and urologists. However, it also underlines

differences in CAUTI treatment and prophylaxis between the disciplines.

The inhomogeneity may stem from varying levels

of professional experience, training and decision-making between general practitioners

and

urologists. Guideline recommendations are a key basis for decision-making. A

handbook on urological diseases, including CAUTI, was recently published for

Swiss general practitioners but has not gained widespread recognition, partly because

it was not

endorsed by medical societies [19]. Furthermore, general practitioners, like urologists,

could

refer to international guidelines such as those from the European Association

of Urology (EAU), which summarise CAUTI management [11]. Additionally, the European

Association of

Urology Nurses (EAUN) recently issued recommendations on catheterisation,

defining CAUTI as a syndrome involving an indwelling catheter for over two days,

a positive urine culture for at least one pathogen and symptoms like fever,

flank pain or dysuria [16].

Other national European guidelines either lack

recommendations regarding catheter management and CAUTI [13] or contradict those of

the EAU and EAUN, as

seen in discrepancies regarding aspects such as the timing of urine sampling

and catheter changes, the duration of treatment and the choice of antimicrobial

agents [16, 20]. For example, the EAU and EAUN recommend taking

the urine sample after changing the catheter, treatment as recommended for

complicated urinary tract infections and choosing a corresponding antibiotic adjusted

to local

resistance patterns following the evidence-based medicine (EBM) recommendations.

[11, 12, 16, 21]. Whereas, for example, the French urological

guidelines recommend taking the sample from the indwelling catheter and

changing it 24 hours later [20]. While the EAU guidelines do not specify a

routine catheter replacement interval, the EAUN suggests that silicone catheters

can remain in place for up to 12 weeks according to manufacturer

recommendations. However, they emphasise that the decision should be

individualised based on factors like encrustation or CAUTIs [11, 16]. Ultimately,

in day-to-day practice,

especially for general practitioners, actively seeking out various guidelines proves

challenging.

They see, diagnose and manage a wide array of diseases and the workload

would simply be overwhelming.

Antimicrobial stewardship interventions, particularly

guideline adherence, reduce hospital stays, morbidity, antimicrobial use and

resistance rates [22, 23]. The absence of or discrepancies in these

recommendations can create uncertainty, as observed among general practitioners in

this study,

potentially leading to unnecessary treatment, increased morbidity and the

development of antimicrobial resistance in CAUTI management.

Good clinical practice relies not only on

guideline adherence but also on clinical routine. In this study, nearly half of

the general practitioners reported limited involvement in catheter management, with

urologists

handling more catheter-related cases and CAUTIs, which may contribute to the

higher level of uncertainty among general practitioners. Despite their relatively

limited

experience, general practitioners and urologists showed similarities in practices,

aligning with EAU

and EAUN guidelines, such as changing catheters every 3 months and basing

diagnoses on symptoms and urine culture [11, 16]. Surprisingly, both disciplines frequently

chose smelly urine and cloudy urine as diagnostic symptoms, even though it is

explicitly mentioned in guidelines that odorous or cloudy urine is neither a

sign for CAUTI nor urinary tract infection [11, 20, 23]. Interestingly, even rather

atypical symptoms

such as reduction of general condition and confusion were frequently considered

by both disciplines as being suggestive of CAUTI or urinary tract infection. Both

general practitioners and

urologists appear to recognise the importance of atypical CAUTI symptom

assessment in this frail patient cohort, understanding – [24, 25], as recommended

by EAUN guidelines [16] – that it extends beyond merely assessing

voiding symptoms.

Similarities between general practitioners and urologists were

also seen in the frequent use of dipstick and urine sediment, even though they

are highly unspecific in catheterised patients due to common asymptomatic

bacteriuria (ABU), pyuria and microhaematuria [11, 23]. Catheterisation leads to bacterial

colonisation

of the catheter and bladder within a few days, resulting in ABU. However, the

mere presence of ABU without symptoms indicative of an infection should not be

misinterpreted as a CAUTI. Basing decision-making for CAUTI treatment on these

diagnostic measures can lead to antibiotic treatment when not necessary, does

not provide benefits [23, 26] and can even harm due to side effects and the

development of antimicrobial resistance [27].

This study identified significant differences

in antimicrobial choices for CAUTI treatment. Both disciplines use co-trimoxazole

as the primary antibiotic for non-febrile CAUTIs, despite it not being a

first-line recommendation for complicated UTIs by the EAU. Urologists primarily

treat febrile CAUTIs with i.v. cephalosporins, aligning with EAU

recommendations and the logistical ease within a hospital setting [11]. General practitioners

frequently use fluoroquinolones for both

non-febrile and febrile CAUTIs. While the EAU still recommends fluoroquinolones

for complicated UTIs in non-hospitalised patients, the European Commission’s restriction

on fluoroquinolone use calls for highly restrictive application, especially in

frail, permanently catheterised patients due to rising antimicrobial resistance

and severe adverse events [28–30].

General practitioners and urologists reported different

durations of treatment, varying between 5–7 days for non-febrile and 7–10 days

for febrile CAUTIs. Guidelines recommend treatment for 7–14 days and indicate

that duration should be closely related to the underlying abnormality. If a

patient is haemodynamically stable and the prostate is not involved, a shorter

course of treatment can be considered [11].

In cases where empirical treatment proves to

be resistant, more than one-third of general practitioners and nearly a quarter of

urologists only

adjust treatment in the absence of clinical improvement. It is one of the

principles of antimicrobial stewardship to adjust to a less broader antibiotic [12]

and in case of resistant bacteria to minimise

early reinfection and selection of antimicrobial resistance [31–33].

An increase in drinking quantity was the

primary prophylactic measure chosen. However, urologists implemented more

prophylactic measures than general practitioners, potentially because they are more

familiar with

managing prophylaxis in recurrent urinary tract infections. To date there are no recommended

prophylactic measures specific to CAUTI, which is reflected in the

inhomogeneity of our results. However, recently published EAUN guidelines

recommend an increase in drinking quantity to decrease catheter encrustation

whereas bladder irrigation is not recommended for preventing CAUTI [16]. Bladder irrigation

is commonly performed as

standard management of long-term urinary catheters, but it remains a

controversial method. A Cochrane review based on studies of poor methodological

quality found inconclusive evidence for the role of bladder irrigation in

preventing CAUTIs [34]. Even though not recommended by guideline

recommendations, bladder irrigation (with tap water) is frequently used in

Switzerland. A recent study showed that bladder irrigation with tap water

reduced CAUTI occurrence and antibiotic use [35].

In case of recurrent CAUTI, general practitioners usually referred

patients to urologists and urologists performed an ultrasound. According to "EbM Guidelines"

[12],

an ultrasound is the main diagnostic measure for recurrent CAUTI in order to

check for causative pathologies such as bladder stones. In 2005, a study showed that

approximately

one third of general practitioners had an ultrasound available [36]. This together

with the uncertainty in CAUTI

management could explain why general practitioners refer patients to the specialist.

One limitation of our study was

that it was not based on direct observations, which did not allow accounting

for recall and reporting biases. Further, our survey results may not adequately

represent CAUTI practices among general practitioners and urologists, as the overall

response

rate cannot be reproduced and was potentially low. However, it is conceivable

that compliance with CAUTI guidelines in non-respondents is not considerably

higher than in those respondents who are less interested in this topic. Lastly,

the CAUTI literature is highly heterogeneous, and even if the recommendations

are classified as strong, many critical clinical questions are not addressed,

which complicates the interpretation of

the study results regarding these recommendations.

In the real-world management of catheters and CAUTIs, similarities

and differences between general practitioners and urologists are evident. Some of

these align

with common recommendations and antimicrobial stewardship principles, while

others deviate from them. Catheter and CAUTI management entail significant

uncertainty for general practitioners. Even urologists, the presumed specialists,

do not always

act in accordance with recommendations and antimicrobial stewardship

principles.

CAUTI management varied notably between general practitioners and urologists in

terms of treatment and prophylaxis. Use of drugs not recommended by guidelines was

common. This trend, along with inappropriate diagnostic methods and prophylaxis, may

increase antimicrobial

resistance and CAUTI morbidity. general practitioners and urologists might benefit

from closer

collaboration and exchange of knowledge. Joint

training sessions could be organised in which specific clinical questions from

routine practice are discussed between the two specialties. Collaborative

conferences could be held, general practitioners could gain access to guidelines from

other

specialties and shared professional literature could be published. The study emphasises

the necessity for diagnostic

and antimicrobial stewardship interventions, and proper training in CAUTI

management for general practitioners and urologists.

PD. Dr. med.

Kathrin Bausch

Department of Urology

University Hospital Basel

Spitalstrasse

21

CH-4031 Basel

kathrin.bausch[at]usb.ch

References

1. Öztürk R, Murt A. Epidemiology of urological infections: a global burden. World J

Urol. 2020 Nov;38(11):2669–79. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-019-03071-4

2. Schweiger A, Maag J, Marschall J. CAUTI Surveillance Teilnehmerhandbuch. Available

from: https://www.swissnoso.ch/fileadmin/module/cauti_surveillance/Dokumente_D/240101_Swissnoso_CAUTI_Surveillance_Handbuch_V2.1.pdf

3. Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Richards CL Jr, Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Pollock DA, et al. Estimating

health care-associated infections and deaths in U.S. hospitals, 2002. Public Health

Rep. 2007;122(2):160–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/003335490712200205

4. Schweiger A, Kuster SP, Maag J, Züllig S, Bertschy S, Bortolin E, et al. Impact of

an evidence-based intervention on urinary catheter utilization, associated process

indicators, and infectious and non-infectious outcomes. J Hosp Infect. 2020 Oct;106(2):364–71.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2020.07.002

5. Munasinghe RL, Yazdani H, Siddique M, Hafeez W. Appropriateness of use of indwelling

urinary catheters in patients admitted to the medical service. Infect Control Hosp

Epidemiol. 2001 Oct;22(10):647–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/501837

6. Jain P, Parada JP, David A, Smith LG. Overuse of the indwelling urinary tract catheter

in hospitalized medical patients. Arch Intern Med. 1995 Jul;155(13):1425–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1995.00430130115012

7. Tiwari MM, Charlton ME, Anderson JR, Hermsen ED, Rupp ME. Inappropriate use of urinary

catheters: a prospective observational study. Am J Infect Control. 2012 Feb;40(1):51–4.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2011.03.032

8. Saint S, Greene MT, Krein SL, Rogers MA, Ratz D, Fowler KE, et al. A Program to Prevent

Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection in Acute Care. N Engl J Med. 2016 Jun;374(22):2111–9.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1504906

9. Jahromi MS, Mure A, Gomez CS. UTIs in patients with neurogenic bladder. Curr Urol

Rep. 2014 Sep;15(9):433. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11934-014-0433-2

10. Cai T, Verze P, Brugnolli A, Tiscione D, Luciani LG, Eccher C, et al. Adherence to

European Association of Urology Guidelines on Prophylactic Antibiotics: An Important

Step in Antimicrobial Stewardship. Eur Urol. 2016 Feb;69(2):276–83. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2015.05.010

11. Bonkat G, Bartoletti R, Bruyère F, Cai T, Geerlings SE, Kranz J, et al. EAU Guidelines

on Urological Infections 2023. Uroweb - European Association of Urology. Available

from: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/urological-infections/chapter/the-guideline

12. Wuorela M. (HWI). In: Rabady S, Sönnichsen A, Kunnamo I (eds.) EbM-Guidelines. Evidenzbasierte

Medizin für Klinik und Praxis. 2023. Available from: https://www.ebm-guidelines.com/dtk/ebmde/avaa?p_artikkeli=ebd00206&p_haku=harnwegsinfekt

13. Leitlinienregister AW. Available from: https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/043-044

14. CAUTI Guidelines | Guidelines Library | Infection Control | CDC. 2019. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/cauti/index.html

15. Bruyere F, Goux L, Bey E, Cariou G, Cattoir V, Saint F, et al. Infections urinaires

de l’adulte : comparaison des recommandations françaises et européennes. Par le Comité

d’infectiologie de l’Association française d’urologie (CIAFU). Prog Urol. 2020;30(8-9):472–81.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.purol.2020.02.012

16. Geng V. Indwelling catheterisation in adults – Urethral and suprapubic. European Association

of Urology Nurses - EAUN. Available from: https://nurses.uroweb.org/guideline/indwelling-catheterisation-in-adults-urethral-and-suprapubic/

17. Hidron AI, Edwards JR, Patel J, Horan TC, Sievert DM, Pollock DA, et al.; National

Healthcare Safety Network Team; Participating National Healthcare Safety Network Facilities.

NHSN annual update: antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated

infections: annual summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network

at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006-2007. Infect Control Hosp

Epidemiol. 2008 Nov;29(11):996–1011. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/591861

18. BAG B für G. Sentinella Meldesystem. Available from: https://www.sentinella.ch/de/info

19. Pro Medicus Gmb H. In a Nutshell - Urologie in der Hausarztpraxis. Available from:

https://www.inanutshell.ch/module/urologie-in-der-hausarzt-praxis/

20. Urofrance | Révision des recommandations de bonne pratique pour la prise en charge

et la prévention des Infections Urinaires Associées aux Soins (IUAS) de l’adulte.

- Urofrance. Available from: https://www.urofrance.org/recommandation/revision-des-recommandations-de-bonne-pratique-pour-la-prise-en-charge-et-la-prevention-des-infections-urinaires-associees-aux-soins-iuas-de-ladulte/

21. Kouri T. Harndiagnostik und Bakterienkultur. In: Rabady S, Sönnichsen A, Kunnamo I

(eds.) EbM-Guidelines. Evidenzbasierte Medizin für Klinik und Praxis. 2023. Available

from: https://www.ebm-guidelines.com/dtk/ebmde/avaa?p_artikkeli=ebd00205&p_haku=uti

22. Goebel MC, Trautner BW, Grigoryan L. The Five Ds of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship

for Urinary Tract Infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2021 Dec;34(4):e0000320. doi: https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00003-20

23. Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, Colgan R, Geerlings SE, Rice JC, et al.; Infectious

Diseases Society of America. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated

urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines

from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Mar;50(5):625–63.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/650482

24. Wojszel ZB, Toczyńska-Silkiewicz M. Urinary tract infections in a geriatric sub-acute

ward-health correlates and atypical presentations. Eur Geriatr Med. 2018;9(5):659–67.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-018-0099-2

25. Dutta C, Pasha K, Paul S, Abbas MS, Nassar ST, Tasha T, et al. Urinary Tract Infection

Induced Delirium in Elderly Patients: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2022 Dec;14(12):e32321.

doi: https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.32321

26. Köves B, Cai T, Veeratterapillay R, Pickard R, Seisen T, Lam TB, et al. Benefits and

Harms of Treatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

by the European Association of Urology Urological Infection Guidelines Panel. Eur

Urol. 2017 Dec;72(6):865–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2017.07.014

27. Krzyzaniak N, Forbes C, Clark J, Scott AM, Mar CD, Bakhit M. Antibiotics versus no

treatment for asymptomatic bacteriuria in residents of aged care facilities: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2022 May;72(722):e649–58. doi: https://doi.org/10.3399/BJGP.2022.0059

28. Bausch K, Bonkat G. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics - what we shouldn’t forget two years

after the restriction by the European Commission. Swiss Med Wkly. 2022 Jan;152(0304):w30126–30126.

doi: https://doi.org/10.4414/SMW.2022.w30126

29. Classifying antibiotics in the WHO Essential Medicines List for optimal use—be AWaRe

- The Lancet Infectious Diseases. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(17)30724-7/abstract

30. Humanmedizin R. ANRESIS. Available from: https://www.anresis.ch/de/antibiotikaresistenz/resistance-data-human-medicine/

31. Holmes AH, Moore LS, Sundsfjord A, Steinbakk M, Regmi S, Karkey A, et al. Understanding

the mechanisms and drivers of antimicrobial resistance. Lancet. 2016 Jan;387(10014):176–87.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00473-0

32.Core Elements of Antibiotic Stewardship for Health Departments | Antibiotic Use |

CDC. 2023. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/core-elements/health-departments.html

33. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, MacDougall C, Schuetz AN, Septimus EJ, et al. Implementing

an Antibiotic Stewardship Program: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of

America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 May;62(10):e51–77.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw118

34. Shepherd AJ, Mackay WG, Hagen S. Washout policies in long-term indwelling urinary

catheterisation in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Mar;3(3):CD004012. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004012.pub5

35. van Veen FE, Den Hoedt S, Coolen RL, Boekhorst J, Scheepe JR, Blok BF. Bladder irrigation

with tap water to reduce antibiotic treatment for catheter-associated urinary tract

infections: an evaluation of clinical practice. Front Urol. 2023 Apr;3:1172271. Available

from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/urology/articles/10.3389/fruro.2023.1172271/full 10.3389/fruro.2023.1172271

36. Tschudi P, Rosemann T. Die Zukunft der Hausarztmedizin! Wie finden wir den Nachwuchs?

Womit können wir junge Ärztinnen und Ärzte für das Weiterbildungsziel «Hausärztin»

motivieren? 2010 Mar; Available from: https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/33323

Appendix

Supplementary tables

Table S1What do

you usually do after receiving the results of the urine culture when the

detected germ proves to be resistant to the antibiotic administered?

|

n total |

General practitioner |

% |

Urologist |

% |

p-value |

| Adjustment |

104 |

46 |

64.8% |

58 |

77.3% |

0.136 |

| Adjustment in the

absence of clinical improvement |

42 |

25 |

35.2% |

17 |

22.7% |

|

| No adjustment |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Table S2If

you perform regular bladder irrigation, which fluid do you use for this?

|

n total |

General practitioner |

% |

Urologist |

% |

p-value |

| Saline solution |

25 |

11 |

84.6% |

14 |

32.6% |

0.018 |

| Tap water |

18 |

1 |

7.7% |

17 |

39.5% |

|

| Hyaluronic acid / chondroitin sulphate |

3 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

7% |

|

| Disinfectant |

6 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

14% |

|

| Other |

4 |

1 |

7.7% |

3 |

7% |

|

Table S3Do

you initiate further diagnostic measures for recurrent urinary tract infections in

catheterised

patients?

|

n total |

General practitioner |

% |

Urologist |

% |

p-value |

| No, treatment only |

32 |

24 |

35.8% |

8 |

11% |

<0.001 |

| Ultrasound |

51 |

8 |

11.9% |

43 |

58.9% |

|

| Referral for an

ultrasound |

5 |

5 |

7.5% |

0 |

0 |

|

| Computed tomography |

4 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

5.5% |

|

| Referral to urologist

(if a general practitioner) |

32 |

30 |

44.8% |

2 |

2.7% |

|

| Other |

16 |

0 |

0 |

16 |

21.9% |

|

Questionnaire

Questions and answer options in

brackets

- Which

country do you work in? [ Austria | France | Germany | Switzerland ]

- Age

[ Free-text answer ]

- Years of experience as a medical professional [ Free-text

answer ]

- Sex

[ Female | Male ]

- Which

type of medical facility do you work in? [ Urological practice | District

hospital | Cantonal hospital | University hospital | Rehabilitation hospital | Other

]

- Do

you care for patients using a permanent urinary catheter? [ No | Rarely | Yes |

Yes and I change transurethral | Yes and I change suprapubic | Yes and I change

both ]

- At

what interval do you usually perform catheter changes in asymptomatic patients?

[ <2 weeks | 2–4 weeks | 1–2 months | 2–3 months | >3 months | Only if

needed ]

- During

the past 12 months, how many patients with transurethral and/or suprapubic

catheters did you see on average per week for catheter-related concerns? [ <

1 | 1–5 | 5–10 | 11–25 | 26–50 | >50 ]

- How

often do you diagnose an urinary tract infection in a catheterised patient per year?

[ <1/year | 1/year

| 2–3/year | 4–5/year | >5/year ]

- Do

you feel competent in managing catheters and recurrent urinary tract infections in

catheterised

patients? [ Somewhat no | Somewhat yes |

Yes ]

- On

which signs/symptoms do you usually base your diagnosis of an urinary tract infection

in a catheterised

patient? [ Burning | Suprapubic pain | Perineal pain | Haematuria | Cloudy

urine | Urine smell | Flank pain | Fever | Reduction of general condition | Confusion

| Testicular pain ]

- How

do you usually diagnose an urinary tract infection in a catheterised patient? [ Symptoms | Examination

| Ultrasound | CT | Dipstick test | Urine status and sediment | Urine culture |

Blood test ]

- How

often do you prescribe an antibiotic for an urinary tract infection per catheterised

patient per

year? [ <1 | 1× | 2–3× | 4–5× | >5× ]

- How

do you choose the antibiotic for empirical therapy? [ Last urine culture | Local

resistances | Empirical ]

- On

average, how long do you usually treat catheterised patients with an antibiotic

for a non-febrile urinary tract infection? [ Single-dose treatment | 3 days | 5 days | 7 days | 10

days | 14 days ]

- Which

antibiotic do you usually choose for the empirical therapy of a non-febrile

urinary tract infection? [ fluoroquinolone | co-trimoxazole | nitrofurantoin | fosfomycin | oral cephalosporin

| amoxicillin ± clavulanic acid ]

- On

average, how long do you usually treat catheterised patients with an antibiotic

for a febrile urinary tract infection? [ Single-dose treatment | 3 days | 5 days | 7 days | 10 days

| 14 days | 3 weeks ]

- Which

antibiotic do you usually choose for the empirical therapy of a febrile urinary tract

infection? [ fluoroquinolone

| co-trimoxazole | nitrofurantoin | fosfomycin | oral cephalosporin | amoxicillin

± clavulanic acid | i.v. cephalosporin | i.v. carbapenems | other ]

- What

do you usually do after receiving the results of the urine culture when the

detected germ proves to be resistant to the antibiotic administered? [ Adjustment

| Adjustment in the absence of clinical improvement | No adjustment ]

- Do

you usually take additional measures to reduce recurrent urinary tract infections

in catheterised

patients? [ None | Drinking quantity | Frequent catheter changes | Optimising

care | Different catheter material | Transurethral -> suprapubic catheter | Plant-based

medication | Bladder irrigation | Acidifying urine | Vaccination | D-Mannose | Continuous

antibiotics | Medication to limit bladder activity ]

- If

you perform regular bladder irrigation, which fluid do you use for this? [ Saline

solution | Tap water | Hyaluronic acid/chondroitin sulphate | Disinfectant | Other

]

- Do

you initiate further diagnostic measures for recurrent urinary tract infections in

catheterised

patients? [ No | Treatment only | Ultrasound | Referral for an ultrasound | CT

| Referral to urologist (if a general practitioner) | Other ]