Outcomes of coronary artery aneurysms: insights from the Coronary Artery Ectasia and

Aneurysm Registry (CAESAR)

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.3857

Alessandro Candrevaab,

Jessica Huwilerc,

Diego Gallob,

Victor Schweigerc,

Thomas Gilhofera,

Roberta Leonea,

Michael Würdingera,

Maurizio Lodi Rizzinib,

Claudio Chiastrab,

Julia Stehlia,

Jonathan

Michela,

Alexander Gotschya,

Barbara E. Stähliac,

Frank Ruschitzkaac,

Umberto Morbiduccib,

Christian Templinde

a Department of Cardiology,

Zurich University Hospital, Zurich, Switzerland

b PolitoBIO Med

Lab, Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Politecnico di Torino,

Torino, Italy

c University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

d Department of Cardiology and Internal Medicine B, University Medicine Greifswald,

Greifswald, Germany

e Swiss CardioVascularClinic, Private Hospital Bethanien, Zurich, Switzerland

Summary

BACKGROUND: Coronary artery ectasias and aneurysms

(CAE/CAAs) are among the less common forms of coronary artery disease, with

undefined long-term outcomes and treatment strategies.

AIMS: To assess the clinical characteristics, angiographic patterns, and

long-term outcomes in patients with CAE, CAA, or both.

METHODS: This 15-year (2006–2021) retrospective

single-centre registry included 281 patients diagnosed with CAE/CAA via

invasive coronary angiography. Major adverse cardiovascular events included

all-cause death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, unplanned ischaemia-driven

revascularisation, hospitalisation for heart failure, cerebrovascular events,

and clinically overt bleeding. Time-dependent event risks for the CAE and CAA

groups were assessed using Cox regression models and Kaplan-Meier curves.

RESULTS: CAEs (n = 161, 57.3%) often had a multi-district distribution

(45.8%), while CAAs (78, 27.8%) exhibited a single-vessel pattern (80%). The co-existence

of CAAs and CAE was observed in 42 cases (14.9%), and multi-vessel obstructive coronary

artery disease was prevalent (55.9% overall). Rates of major adverse

cardiovascular events were 14.3% in-hospital and 38.1% at a median follow-up of

18.9 (interquartile range [IQR] 6.0–39.9) months. The presence of CAAs was associated

with increased major adverse cardiovascular events risk in comparison to CAE (hazard

ratio [HR] = 2.26, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.38–3.69, p

= 0.001), driven by a higher hazard ratio of non-fatal myocardial infarctions (HR

= 5.00, 95% CI 1.66–15.0, p = 0.004) and unplanned ischaemia-driven revascularisation

in both dilated (HR = 3.23, 95% CI 1.40–7.45, p = 0.006) and non-dilated

coronary artery segments (HR 3.83, 95% CI 2.08–7.07, p = 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS: Overlap between obstructive and dilated coronary artery disease is

frequent. Among the spectrum of dilated coronary artery disease, the presence

of a CAA was associated with worse long-term outcomes.

Abbreviations

- CAA:

-

coronary artery aneurysm

- CAE:

-

coronary artery ectasia

Introduction

Expansive (or positive) coronary artery

remodelling occurs in the initial phase of atherosclerotic plaque formation [1].

The migration of leukocytes, foam cell formation in the vessel wall, and

subsequent extracellular matrix degradation are considered the fundamental

mechanisms underpinning this process [1]. This remodelling can maintain the

diameter of the vessel lumen, potentially acting as an early compensatory

mechanism to prevent luminal narrowing. However, dysregulation of the inflammatory

response and proteolysis of extracellular matrix proteins [2] might lead to reverse

remodelling with plaque deposition and luminal narrowing or a further increase

in the vessel’s lumen, locally enlarging the vessel’s diameter to the point where

it reaches the criteria for coronary ectasia [3]. Degradation or injury to any

of the vessel layers, particularly the media, can lead to the formation of an aneurysm

[4].

Coronary artery ectasias and aneurysms

(CAE/CAAs) have typically been defined as a diffuse or focal coronary dilation that

exceeds the diameter of normal adjacent segments or the diameter of the

patient’s largest coronary vessel by 1.5 times [5]. CAE/CAAs are uncommon forms

of coronary artery disease and have been diagnosed with increasing frequency since

the introduction of coronary angiography. Their incidence has been reported to

vary from 1.5% to 5.0%, with a suggested male predominance [6]. Although

several causes have been proposed, atherosclerosis accounts for more than 50%

of CAAs in adults [7]. Reported complications include thromboses and distal

embolisations, vasospasms, and ruptures that produce ischaemia, heart failure,

or arrhythmias [2]. The natural progression of CAE/CAAs and their long-term

outcomes remain uncertain due to the scarcity of definitive data, which are

often skewed by varying anatomical definitions and inclusion criteria.

Furthermore, a direct comparison between the two forms of dilated coronary

artery disease is lacking. Controversies also persist over the use of medical

treatment (such as anti-thrombotic therapy) or interventional/surgical

procedures.

Therefore, in this study, we aimed to delineate

the clinical and angiographic characteristics of patients presenting with CAE,

CAA or both, confirmed using invasive coronary angiography. Moreover, clinical

outcomes were assessed over an extended period, allowing for a more

comprehensive understanding of these conditions.

Methods

Study design

The coronary artery ectasia and aneurysm

registry (CAESAR) is a monocentric, retrospective registry that includes

all-comer patients with angiographical evidence of CAE or CAA based on invasive

coronary catheterisation.

Retrospective patient recruitment consisted

of (a) a clinical database query for a CAE/CAA diagnosis dating from January 1,

2006 to December 31, 2021 (see appendix),

(b) manual screening of electronic medical records and a review of

angiographies, and (c) visual confirmation of the diagnosis and classification of

CAE, CAA and CAA-CAE (if combined), performed by catheterisation laboratory

personnel. Any ambiguities were resolved through group consensus.

CAA was visually defined as a focal

dilation of coronary segments of at least 1.5 times the adjacent normal

segment, whereas CAE was associated with a more diffuse dilatation (>20 mm

in length). Morphologically, CAAs were defined as “saccular” if the transverse diameter exceeded the longitudinal

diameter, “fusiform” in the opposite

case, and “giant” if the transverse

diameter exceeded 20 mm. CAEs were defined as “diffuse” if they involved more than one vessel segment and “focal” if confined within one vessel

segment. CAE “types” were defined

according to the combination of diffuse and focal components [2]:

- Type I: diffuse ectasia involving two or three vessels

- Type II: diffuse disease in one vessel accompanied by localized disease in another

vessel

- Type III: diffuse ectasia confined to one vessel

- Type IV: localized ectasia

We excluded patients with

lesions localised in a bypass graft, those upstream of a chronically occluded

vessel (CTO), or patients presenting a stent within the vessel dilation at the

time of the index coronary angiography. Patients without coronary angiograms

available for visual inspection were also excluded. Coronary artery disease was

identified and defined as a visual diameter stenosis above 50%.

Hospital records were screened for baseline

clinical characteristics and co-morbidities (including inflammatory and

oncologic diseases) as well as for cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular (i.e.

the de novo diagnosis of infectious, inflammatory and oncologic diseases) outcomes

for each enrolled patient, starting from the index invasive coronary

angiography. Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) were defined as a composite

of any incidental all-cause death, non-fatal myocardial infarctions or acute

coronary syndromes (ACSs), unplanned ischaemia-driven percutaneous coronary

interventions (PCIs), re-hospitalisation for heart failure (HF), acute

cerebrovascular events and clinically overt bleeding (Bleeding Academic

Research Consortium [Bleeding Academic Research Consortium] ≥2). Follow-up data

collection ended on December 31, 2022.

The study protocol conformed to the ethical

guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local

ethics committee (BASEC 2021-01119). Retrospective patient inclusion was

possible for patients who signed the general consent for research at the

University Hospital of Zurich and provided an informed written agreement for

clinical data usage for research purposes. Approval by the Data Governance

Board of the University Hospital of Zurich was obtained for database queries

and extractions.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed at

a per-patient level to compare the three classification groups (CAE, CAA and

CAA-CAE). Continuous variables with normal distributions are presented as mean

± standard deviation (SD), and non-normally distributed variables as medians

(interquartile range [IQR]). Categorical variables are presented as

percentages. The Chi-squared test was used for comparing categorical variables,

while the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for continuous variables. Time-to-event

data are presented as Kaplan-Meier estimates. Follow-up calculations were based

on the time from the index invasive coronary angiography to the occurrence of a

major adverse cardiovascular event or the last follow-up date. Censoring events

included patients who were lost to follow-up or had not experienced a major

adverse cardiovascular event by the end of the study period. Cox

proportional-hazards regression models were used to compare the risk of incident

events by CAA or CAE. To avoid ambiguity, the CAA-CAE group was omitted from the

time-to-event and event prediction analyses. Anatomical and functional

variables presenting a univariate relationship with incident events were

included in the Cox proportional-hazards regression models. The proportional

hazards assumption was verified as part of the Cox regression analysis and the Schoenfeld

residual test. All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 29 (IBM Corp.

Armonk, NY, USA) and MATLAB (Version R2022, MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA).

Results

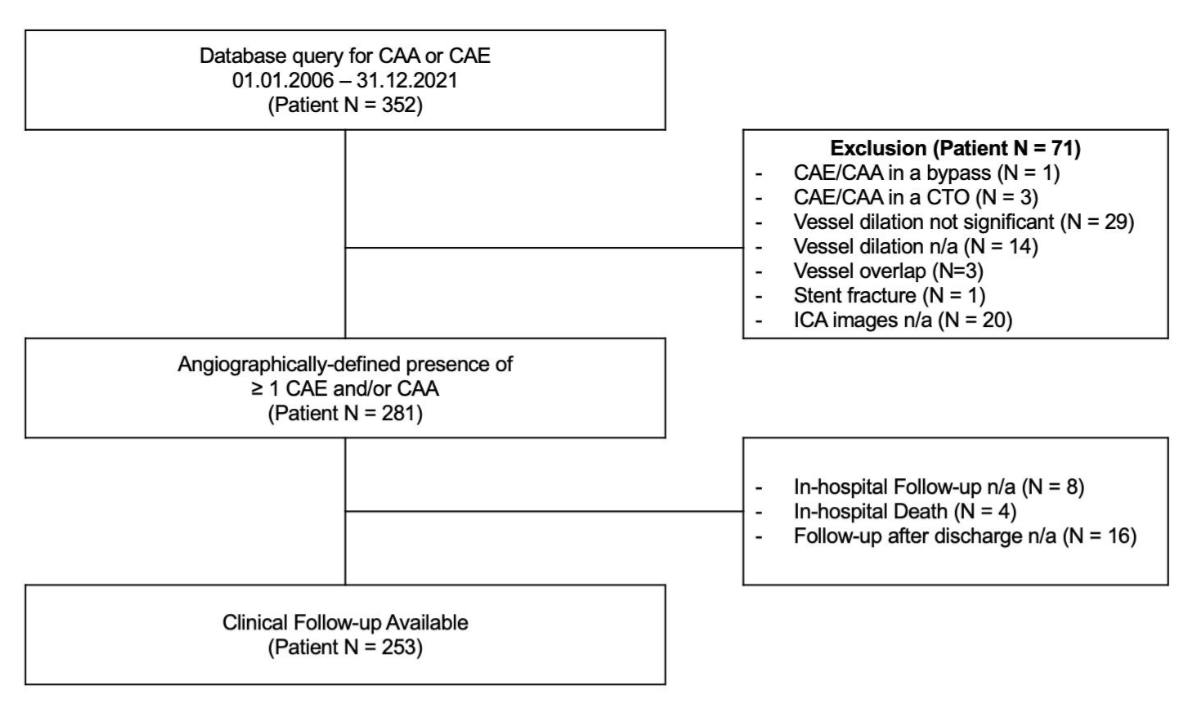

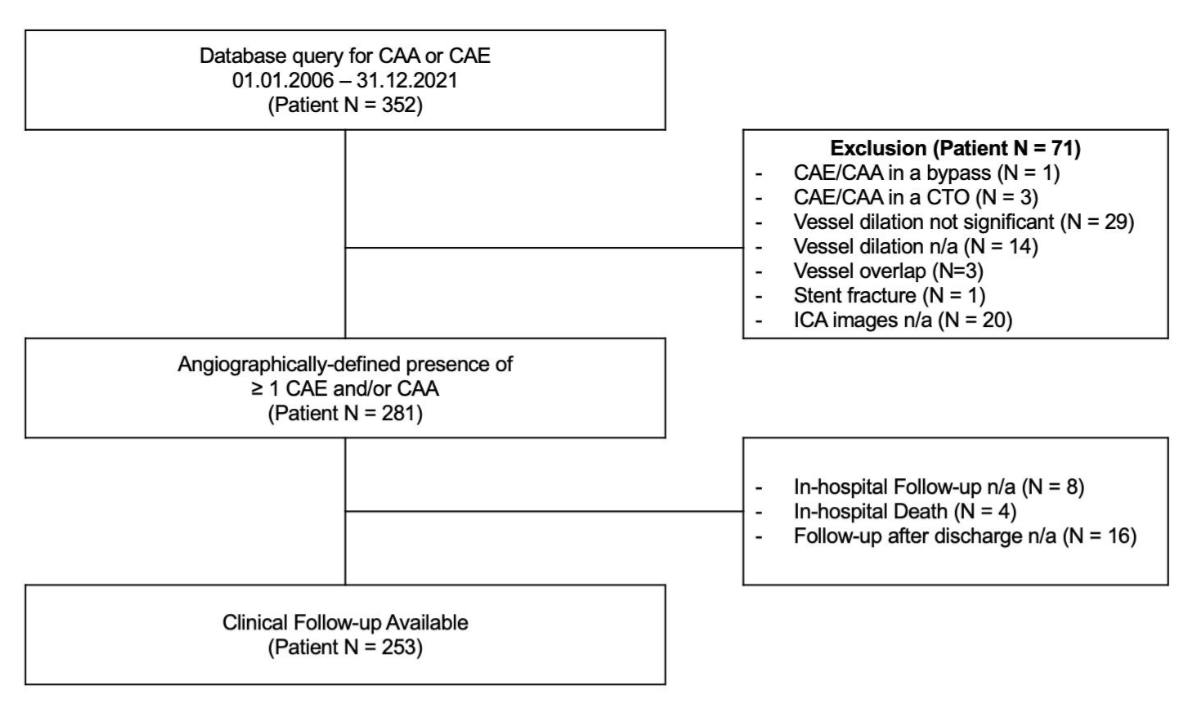

Over 15 years (figure 1), a total of 281

patients presented with either a CAA (27.8%), a CAE (57.3%) or both (14.9%).

Figure 1Study flowchart. From the initial

352 patients presenting with a coronary aneurysm or ectasia according to the

database query, 71 met the study exclusion criteria, and 281 were included in

the study. Clinical follow-up was available in 253 cases. CAA: coronary artery

aneurysm; CAE: coronary artery ectasia; CTO: chronic total occlusion; ICA:

invasive coronary angiography; n/a: not available.

Clinical characteristics

Patients were predominantly male (87.9%),

with a median age of 66 (57.7–74.5) years. The CAA group had a higher percentage

of female patients (19.2% vs 10.6%, p = 0.045) and a higher median age

(70.9 vs 65.4 years, p = 0.077), see table 1. The CAA group also had a lower prevalence

of ST segment

elevation myocardial infarctions (STEMIs) at the index event than the CAA-CAE

and the CAE groups (7.7% vs 26.2% vs 14.3%, p = 0.022,

respectively). Among the 40 patients presenting with STEMI, the causal lesion

could be identified in 11 cases with an ectatic segment and in 3 cases with an

aneurysmatic segment. Approximately one-fourth of the patients were admitted

with symptoms or signs of acute heart failure (23.1% overall), while more than half

had a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (median = 53% overall). Nearly

one-third of the patients presented ectatic or aneurysmatic vessels in other

body areas. CAA patients were more likely to have undergone previous cardiac

surgery (19.2% vs 0.0% vs 8.1%, p = 0.002). No differences were found regarding previous

occurrences of cancer (19.9% overall) or inflammatory diseases among the groups

(11.7% overall). High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) concentration at baseline

was comparable between the groups (3.30 mg/l overall), see appendix table S1.

Table 1Baseline clinical characteristics.

|

Total |

“CAA” |

“CAA-CAE” |

“CAE” |

p-value |

| Patient n = 281 |

Patient n = 78 |

Patient n = 42 |

Patient n = 161 |

2-sided |

| Age, years |

66.1 (57.7–74.5) |

70.9 (58.4–76.3) |

63.01 (58.5–71.5) |

65.4 (57.2–73.2) |

0.077 |

| Female, n (%) |

34 (12.1) |

15 (19.2) |

2 (4.76) |

17 (10.6) |

0.045 |

| BMI, kg/m2 |

28.0 (24.9–31.3) |

28.31 (24.8–30.5) |

27.99 (25.2–32.7) |

27.85 (24.9–31.5) |

0.710 |

| Chest pain, n (%) |

183 (65.1) |

49 (62.8) |

37 (88.1) |

97 (60.3) |

0.003 |

| Dyspnoea, n (%) |

|

148 (52.7) |

47 (60.3) |

17 (40.5) |

84 (52.2) |

0.115 |

| NYHA class ≥III, n (%) |

62 (22.1) |

19 (24.4) |

8 (19.1) |

35 (21.7) |

0.666 |

| Stabile angina, n (%) |

65 (23.1) |

15 (19.2) |

11 (26.2) |

39 (24.2) |

0.608 |

| Acute coronary syndrome, n (%) |

|

115 (40.9) |

30 (38.5) |

23 (54.8) |

62 (38.5) |

0.142 |

| STEMI, n (%) |

40 (14.2) |

6 (7.7) |

11 (26.2) |

23 (14.3) |

0.022 |

| NSTEMI, n (%) |

59 (21.0) |

20 (25.6) |

10 (23.8) |

29 (18.0) |

0.354 |

| Unstable angina, n (%) |

16 (5.69) |

4 (5.13) |

2 (4.76) |

10 (6.21) |

0.907 |

| Acute heart failure, n (%) |

65 (23.1) |

21 (26.9) |

8 (19.1) |

36 (22.4) |

0.583 |

| LVEF, % |

53 (40–59) |

55 (42–60) |

55 (45–58) |

51 (39–58) |

0.497 |

| eGFR <30 ml/min, n (%) |

14 (4.98) |

5 (6.41) |

0 (0.00) |

9 (5.59) |

0.272 |

| Ectasia or aneurysm in other body

districts* |

|

84 (29.9) |

29 (37.2) |

11 (26.1) |

44 (27.3) |

0.252 |

| Thorax |

47 |

12 |

6 |

29 |

|

| Abdomen |

37 |

15 |

5 |

17 |

|

| Other |

14 |

7 |

1 |

6 |

|

| Hypertension, n (%) |

197 (70.1) |

55 (70.5) |

27 (64.3) |

115 (71.4) |

0.664 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) |

178 (63.4) |

50 (64.1) |

26 (61.9) |

102 (63.4) |

0.972 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus, n (%) |

81 (28.8) |

22 (28.2) |

8 (19.1) |

51 (31.7) |

0.271 |

| Smoking, n (%) |

186 (66.2) |

52 (66.7) |

31 (73.8) |

103 (64.0) |

0.484 |

| Positive family history, n (%) |

98 (34.9) |

30 (38.5) |

13 (31.0) |

55 (34.2) |

0.697 |

| History of coronary artery disease, n (%) |

94 (33.5) |

30 (38.5) |

11 (26.2) |

53 (32.9) |

0.388 |

| History of cardiac surgery, n (%) |

28 (10.0) |

15 (19.2) |

0 (0.00) |

13 (8.07) |

0.002 |

| History of peripheral artery disease, n

(%) |

23 (8.19) |

10 (12.8) |

3 (7.14) |

10 (6.21) |

0.216 |

| History of cerebrovascular insult, n (%) |

21 (7.47) |

6 (7.69) |

2 (4.76) |

13 (8.07) |

0.759 |

| History of cancer, n (%) |

56 (19.9) |

14 (18.0) |

8 (19.0) |

34 (21.1) |

0.837 |

| History of inflammatory disease, n (%) |

33 (11.7) |

9 (11.5) |

8 (19.1) |

16 (9.9) |

0.263 |

Angiographic characteristics and treatment strategies

at the index event

At the angiographical evaluation, CAAs were

primarily found in a single vessel (80%), with a relatively low incidence in

all three coronary arteries (6.7%), as reported in table 2. Fusiform aneurysms were

the most common CAA type (65.8%).

The co-occurrence of fusiform and saccular CAAs within the same patient was

rare (5.0%). In contrast, CAE demonstrated a multi-district distribution in

nearly half of the cases (45.8%), with types 2 and 4 being the most frequently

observed (21.0% and 20.6%, respectively).

Table 2Angiographic characteristics at the

index coronary angiography.

|

Any CAA |

“CAA” |

“CAA-CAE” |

“CAE” |

p-value |

| Patient n = 120 |

Patient n = 78 |

Patient n = 42 |

Patient n = 161 |

2-sided |

| Number of coronary arteries presenting

CAA, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

0.621 |

| One |

96 (80.0) |

64 (82.1) |

32 (76.2) |

– |

| Two |

16 (13.3) |

10 (12.8) |

6 (14.3) |

– |

| Three |

8 (6.67) |

4 (5.13) |

4 (9.52) |

– |

| CAA type, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Saccular |

35 (29.2) |

25 (32.1) |

10 (23.8) |

– |

| Fusiform |

79 (65.8) |

48 (61.5) |

31 (73.8) |

– |

| Combined |

6 (5.0) |

5 (6.41) |

1 (2.38) |

– |

|

Any CAE |

“CAA” |

“CAA-CAE” |

“CAE” |

p-value |

| Patient n = 203 |

Patient n = 78 |

Patient n = 42 |

Patient n = 161 |

2-sided |

| Number of coronary arteries presenting

CAE, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

0.291 |

| One |

110 (54.2) |

– |

27 (64.3) |

83 (51.6) |

| Two |

62 (30.5) |

– |

11 (26.2) |

51 (31.7) |

| Three |

31 (15.3) |

– |

4 (9.52) |

27 (16.8) |

| CAE type, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Type 1 |

39 (13.9) |

– |

7 (16.7) |

32 (19.9) |

| Type 2 |

59 (21.0) |

– |

23 (54.7) |

36 (22.4) |

| Type 3 |

47 (16.7) |

– |

0 (0.00) |

47 (29.2) |

| Type 4 |

58 (20.6) |

– |

12 (28.6) |

46 (28.6) |

Over half of the patients (55.9%) exhibited

multi-vessel coronary artery disease, with a trend towards reduced prevalence

in those with CAE (absence of coronary artery disease: CAA 15.4% vs CAE

23.0%), although the differences between the three groups were not significant

(p = 0.061), as shown in table 3.

Table 3Coronary artery disease prevalence

and treatment strategy at the index coronary angiography.

|

|

Total |

“CAA” |

“CAA-CAE” |

“CAE” |

|

| Patient n = 281 |

Patient n = 78 |

Patient n = 42 |

Patient n = 161 |

2-sided |

| Number of coronary arteries presenting coronary

artery disease, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

0.061 |

| One |

73 (26.0) |

17 (21.8) |

10 (23.8) |

46 (28.6) |

| Two |

68 (24.2) |

22 (28.2) |

14 (33.3) |

32 (19.9) |

| Three |

89 (31.7) |

27 (34.6) |

16 (38.1) |

46 (28.6) |

| No coronary artery disease |

51 (18.2) |

12 (15.4) |

2 (4.8) |

37 (23.0) |

| Any percutaneous coronary intervention, n

(%) |

122 (43.4) |

32 (41.0) |

24 (57.2) |

66 (41.0) |

0.166 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention of

CAE/CAA, n (%) |

|

57 (20.3) |

19 (24.4) |

15 (35.7) |

23 (14.3) |

0.853 |

| With BMS, n (%) |

3 (1.1) |

1 (1.3) |

1 (2.3) |

1 (0.6) |

0.954 |

| With drug-eluting stent, n (%) |

47 (16.7) |

15 (19.2) |

12 (28.6) |

20 (12.4) |

0.948 |

| With a covered stent, n (%) |

3 (1.1) |

2 (2.6) |

1 (2.3) |

0 (0.0) |

0.302 |

| With plain old balloon angioplasty, n (%) |

4 (1.4) |

1 (1.3) |

1 (2.3) |

2 (1.2) |

0.909 |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting, n (%) |

32 (11.4) |

13 (16.7) |

4 (9.52) |

15 (9.30) |

0.172 |

| Conservative treatment, n (%) |

127 (45.2) |

33 (42.3) |

14 (33.3) |

80 (49.7) |

0.138 |

A percutaneous coronary intervention was

conducted in 43.4% of the cases during the initial procedure, with no

significant distinctions between groups (p = 0.166), table 4. Interventions targeting

dilated coronary segments

occurred more frequently in CAA and CAA-CAE patients compared to those with CAE

alone (24.4% vs 35.7% vs 14.3%, p = 0.853, respectively) and

drug-eluting stents (DES) were generally used (47/57 of cases, p = 0.948). Patients

with CAE had the highest prevalence of conservative medical treatment (49.7%, p

= 0.138). Illustrated case examples of percutaneous coronary interventions on

dilated coronary arteries are presented in appendix figures S1–S6.

At the vessel level, both saccular and

fusiform CAAs were frequently identified in the left anterior descending (LAD)

artery (33.0% and 40.5%, p <0.001, respectively), whereas three out of the

four giant CAAs (75.0%, p <0.001) were localised in the right coronary

artery (RCA). CAEs were often detected in the right coronary artery (46.9%),

with type 2 being the most common CAE subtype (33.6%), as illustrated in appendix

table S2.

In-hospital and long-term outcomes

Clinical adverse events were documented in

80 cases (28.3%) prior to hospital discharge, with no significant differences between

the groups (33.8% vs 21.1% vs 29.1%, p = 0.369, respectively). Rates

were primarily driven by periprocedural bleeding (5.49%, p = 0.223) and acute

heart failure (6.23%, p = 0.841), as shown in appendix table S3.

Over a median follow-up period of 18.9

months (IQR 6.0–39.9), the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events was

substantial (CAA 44.0%, CAA-CAE 40.5% and CAE 34.5%; p = 0.367). Patients

with the mixed disease form exhibited a higher rate of percutaneous coronary

interventions targeting the dilated coronary segment (10.7%, 27.0% and 9.7%; p

= 0.014), which was driven by a higher acute coronary syndrome rate (6.7%,

18.9% and 7.6%; p = 0.070), as detailed in table 4. Among the twelve reported patients

with

in-stent restenosis, four occurred in stents deployed in a dilated coronary

artery segment (two cases in CAA vessels, one case in a CAE vessel, and one in

a vessel presenting a mixed form). Only one stent thrombosis occurred in a

dilated coronary artery (an aneurysmatic vessel). The detection of de novo

cancers, inflammatory diseases and infectious diseases was reported in 8.2%,

3.1%, and 16.7% of cases for CAA, CAA-CAE, and CAE, respectively, with no

significant differences between the groups (p >0.05 in all groups), appendix table

S4.

Table 4Events at follow-up.

|

Total |

“CAA” |

“CAA-CAE” |

“CAE” |

p-value |

| Patient n = 257 |

Patient n = 75 |

Patient n = 37 |

Patient n = 145 |

2-sided |

| Follow-up event, n (%) |

149 (58.0) |

44 (58.7) |

25 (67.6) |

80 (55.2) |

0.391 |

| Follow-up duration, days |

568 (180–1197) |

713 (225–1305) |

428 (182–1220) |

543 (161–1155) |

0.378 |

| Re-coronary angiography, n (%) |

96 (37.4) |

26 (34.7) |

17 (45.9) |

53 (36.6) |

0.487 |

| Major adverse cardiovascular events, n

(%) |

98 (38.1) |

33 (44.0) |

15 (40.5) |

50 (34.5) |

0.367 |

| All-cause death, n (%) |

49 (19.1) |

20 (26.7) |

5 (13.5) |

24 (16.6) |

0.126 |

| Cardiac death, n (%) |

10 (3.9) |

3 (4.0) |

1 (2.7) |

6 (4.1) |

0.920 |

| Acute coronary syndrome, n (%) |

23 (8.9) |

5 (6.7) |

7 (18.9) |

11 (7.6) |

0.070 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention, n (%) |

59 (23.0) |

17 (22.7) |

12 (32.4) |

30 (20.7) |

0.316 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention of

CAE/CAA, n (%) |

32 (12.5) |

8 (10.7) |

10 (27.0)* |

14 (9.7) |

0.014 |

| In-stent restenosis, n (%) |

12 (4.7) |

4 (5.3) |

4 (10.8) |

4 (2.8) |

0.111 |

| Stent thrombosis, n (%) |

3 (1.2) |

1 (1.3) |

0 (0.0) |

2 (1.4) |

0.774 |

| Cerebrovascular event, n (%) |

7 (2.7) |

2 (2.7) |

1 (2.7) |

4 (2.8) |

0.999 |

| Re-hospitalisation for heart failure, n

(%) |

9 (3.5) |

5 (6.7) |

1 (2.7) |

3 (2.1) |

0.205 |

| Bleeding, n (%) |

30 (11.7) |

7 (9.3) |

6 (16.2) |

17 (11.7) |

0.566 |

| Medication upon admission |

Single anti-platelet therapy, n (%) |

30

(11.7) |

9

(12.0) |

3

(8.1) |

18

(12.4) |

0.763 |

| Dual anti-platelet therapy, n (%) |

26

(10.1) |

7

(9.3) |

5

(13.5) |

14

(9.7) |

0.758 |

| Oral anticoagulant, n (%) |

17

(6.6) |

4

(5.3) |

4

(10.8) |

9

(6.2) |

0.524 |

| Dual anti-thrombotic therapy, n (%) |

13

(5.1) |

3

(4.0) |

1

(2.7) |

9

(6.2) |

0.606 |

| Triple anti-thrombotic therapy, n (%) |

2

(0.8) |

1

(1.3) |

0

(0.0) |

1

(0.7) |

0.739 |

| Medication at discharge |

Single anti-platelet therapy, n (%) |

14

(5.4) |

5

(6.7) |

1

(2.7) |

8

(5.5) |

0.684 |

| Dual anti-platelet therapy, n (%) |

43

(16.7) |

12

(16.0) |

8

(21.6) |

23

(15.9) |

0.690 |

| Oral anticoagulant, n (%) |

9

(3.5) |

1

(1.3) |

2

(5.4) |

6

(1.4) |

0.446 |

| Dual anti-thrombotic therapy, n (%) |

11

(4.3) |

3

(4.0) |

2

(5.4) |

6

(1.4) |

0.934 |

| Triple anti-thrombotic therapy, n (%) |

13

(5.1) |

4

(5.3) |

1

(2.7) |

8

(5.5) |

0.778 |

| Bleeding classification |

|

|

|

|

|

0.642 |

| BARC 1, n (%) |

2

(0.8) |

1

(1.3) |

0

(0.0) |

1

(0.7) |

|

| BARC 2, n (%) |

6

(2.3) |

2

(2.7) |

0

(0.0) |

4

(2.8) |

|

| BARC 3a, n (%) |

3

(1.2) |

1

(1.3) |

0

(0.0) |

2

(1.4) |

|

| BARC 3b, n (%) |

5

(1.9) |

1

(1.3) |

2

(5.4) |

2

(1.4) |

|

| BARC 3c, n (%) |

7

(2.7) |

2

(2.7) |

3

(8.1) |

2

(1.4) |

|

| BARC 4, n (%) |

1

(0.4) |

0

(0.0) |

0

(0.0) |

1

(0.7) |

|

| BARC 5a, n (%) |

1

(0.4) |

0

(0.0) |

0

(0.0) |

1

(0.7) |

|

| BARC 5b, n (%) |

5

(1.9) |

0

(0.0) |

1

(2.7) |

4

(2.8) |

|

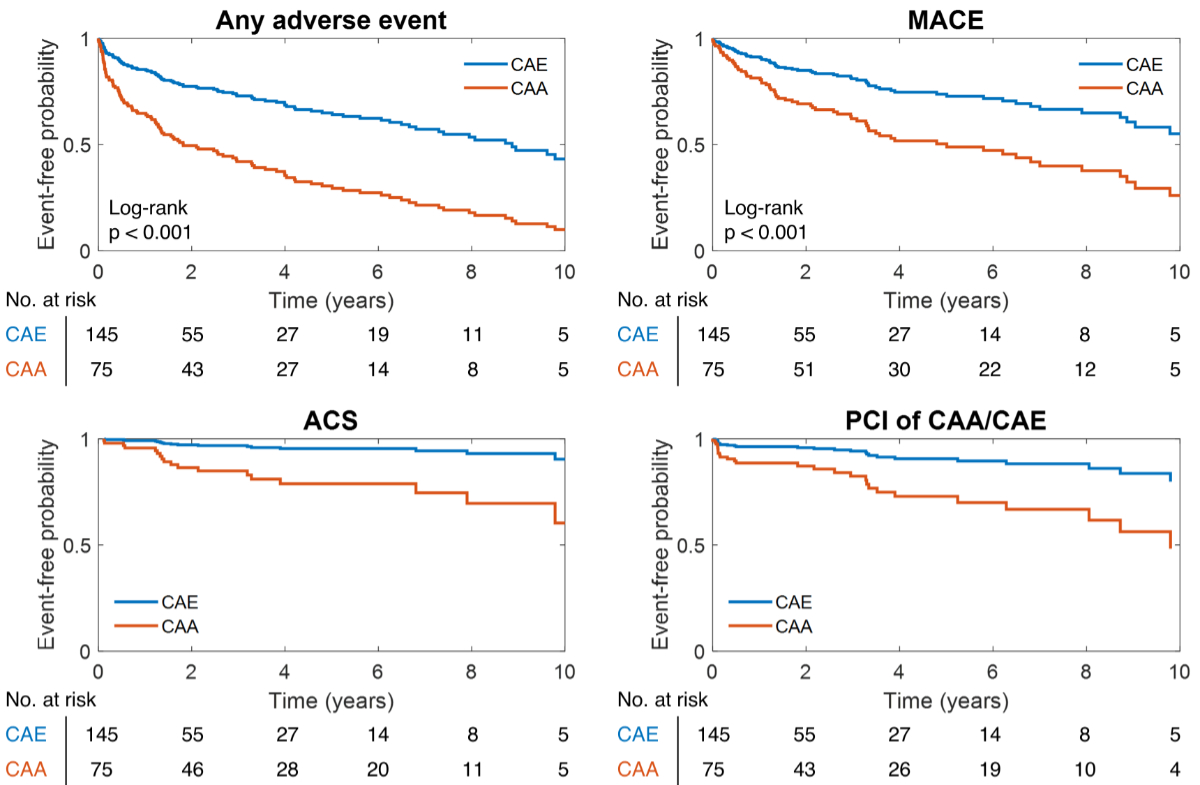

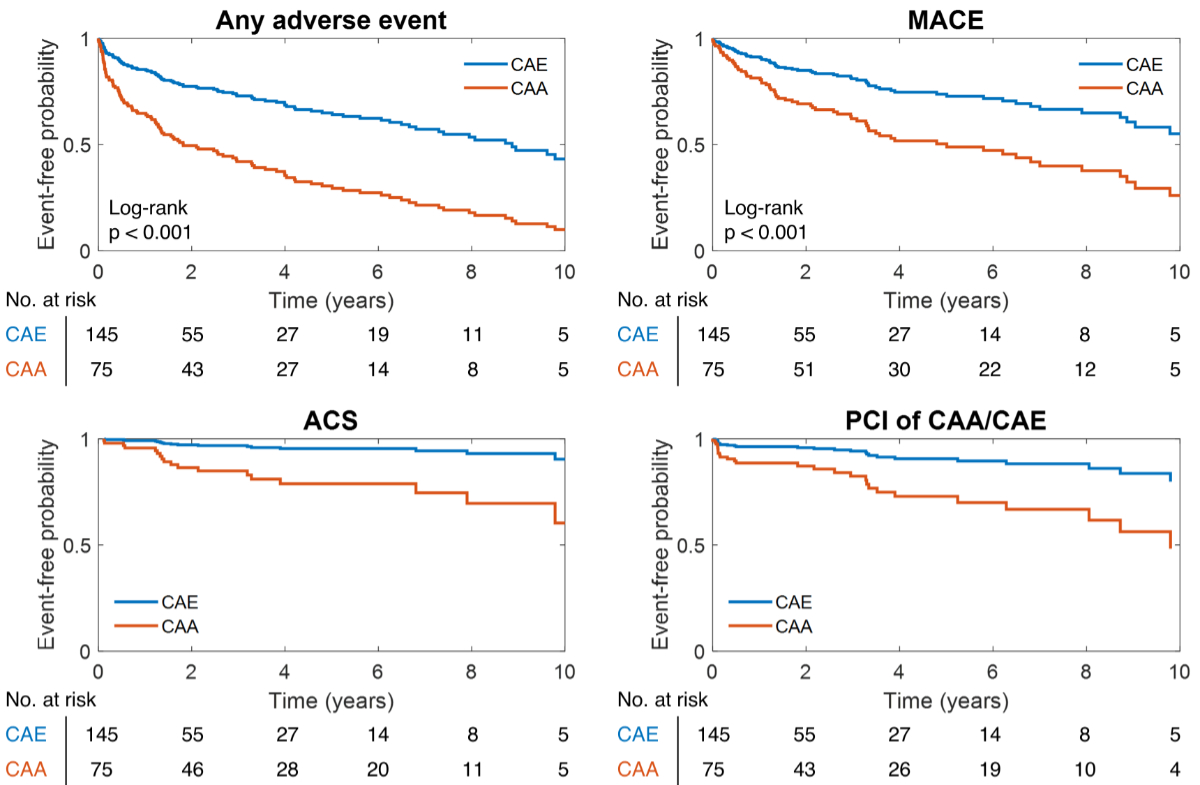

Longitudinally, patients with

angiographically identified CAA exhibited worse clinical outcomes than those with

CAE, which reflected a higher incidence of acute coronary syndrome at follow-up

and higher rates of coronary re-intervention (either at the level of the

dilated coronary segment or in any normal coronary artery segment), figure 2 and appendix

figure S7.

Figure 2Event incidence at the long-term

follow-up. Patients presenting either coronary artery ectasia (CAE) or coronary

artery aneurysm (CAA) showed an elevated incidence of adverse events at the

long-term follow-up. ACS: acute coronary syndrome; MACE: major adverse

cardiovascular events; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

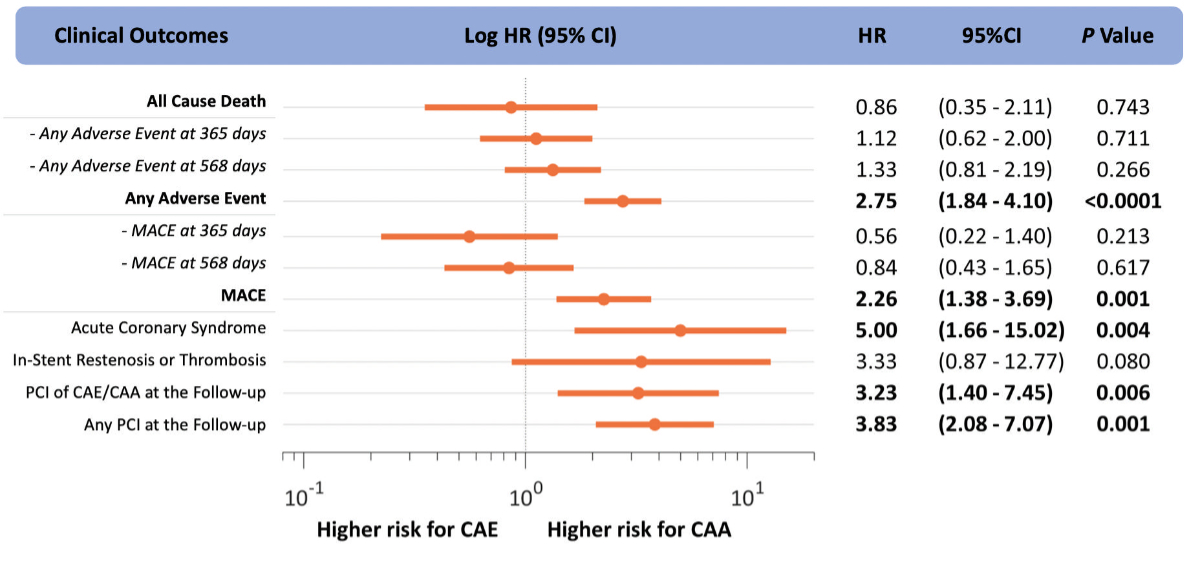

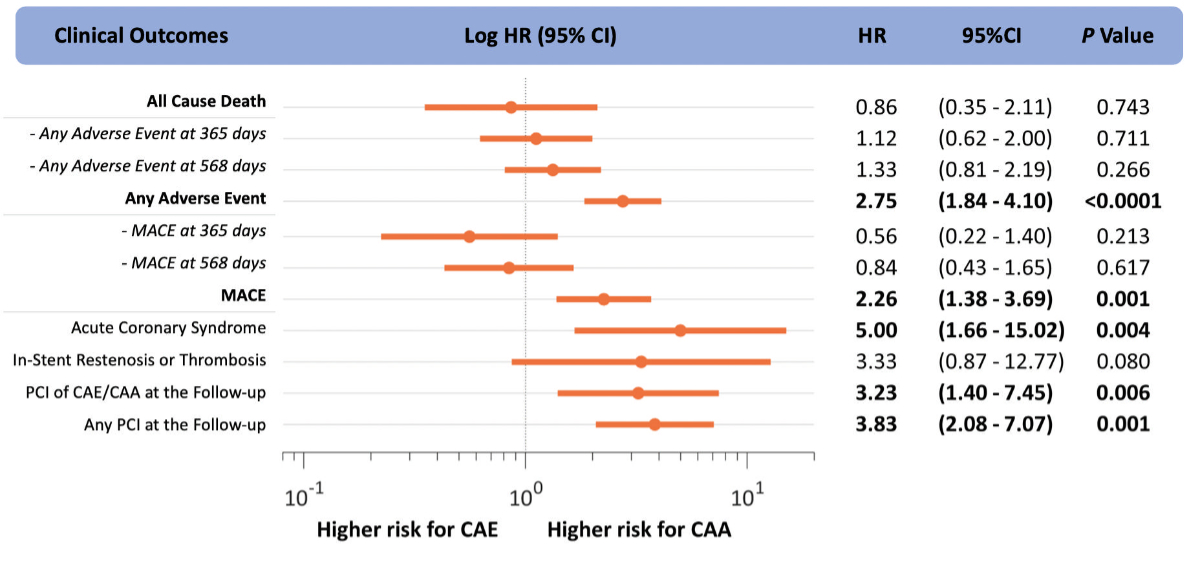

The Cox proportional hazards regression

analysis found that aneurysmatic coronary artery segments exhibited a higher

risk of adverse events compared to CAE (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.75, 95%

confidence interval [CI] 1.84–4.10), p <0.0001) and major adverse

cardiovascular events (HR = 2.26, 95% CI 1.38–3.69, p = 0.001), driven by a

higher acute coronary syndrome hazard (HR = 5.00, 95% CI 1.66–15.02, p = 0.004)

and percutaneous coronary intervention hazard (in a dilated coronary segment:

HR 3.23, 95% CI 1.40–7.45, p = 0.006; in any coronary segment: HR 3.83, 95% CI

2.08–7.07, p = 0.001), figure 3 and figure

S8 in the appendix. The presence of obstructive coronary artery disease

did not significantly influence the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events

at the follow-up in CAA or CAE patients, appendix figure S9.

Figure 3Time-dependent event risk. Results

of the Cox models for coronary artery ectasia (CAE) or coronary artery aneurysm

(CAA) and the time-dependent hazard ratio (HR) of adverse events. In dash,

the shorter-term outcomes with respect to the one reported in bold (maximum

follow-up time). MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events; PCI:

percutaneous coronary intervention.

Discussion

In this study, a total of 281 patients with

dilated coronary artery disease were investigated, and clinical characteristics,

angiographic patterns and the long-term adverse outcomes of patients presenting

with CAE and CAA were described. The main results of the study were: (a) CAE

demonstrated a multi-district distribution, while CAAs were primarily isolated

to a single coronary segment; (b) multi-vessel obstructive coronary artery

disease was prevalent in more than half of the patients; (c) clinical adverse

events were common in-hospital and at the long-term follow-up; and (d) aneurysmatic

coronary artery segments were associated with a higher risk of adverse events

and major adverse cardiovascular events, which was driven by higher hazards of acute

coronary syndrome and percutaneous coronary intervention at the follow-up.

The spectrum of coronary artery remodelling

The initial phase of atherosclerotic plaque

formation involves leukocyte migration, foam cell formation, and extracellular

matrix degradation, leading to expansive coronary remodelling that maintains

lumen diameter and prevents narrowing [1]. Dysregulation of these mechanisms by

injury or degradation of the vessel layers, especially the media, can cause

either reverse remodelling with luminal narrowing or further dilation,

resulting in coronary ectasia and aneurysm formation [2–4]. As such, both

obstructive and dilative coronary artery disease can co-exist within the same

coronary artery tree. In our analysis, only a small percentage of the vessels

included in the study failed to exhibit a (significant) obstructive coronary

artery disease form (18.2%). Instead, extensive three-vessel disease was the

most common coronary artery disease variant associated with either CAA (34.6%)

or CAE (28.6%). This, coupled with the high prevalence of traditional

cardiovascular risk factors in both dilative coronary artery disease subgroups,

supports the theory of a significant overlap in the pathobiology between

obstructive and dilative coronary artery disease [8]. Notably, this disease

form appears to predominantly affect males (ca. 88% of male patients in our

cohort), a trend consistent with the literature [9].

Coronary aneurysms and ectasia as two different biological

conditions

While sharing a similar pathophysiology, in

our analysis, CAAs and CAEs appeared to be distinct entities with marginally overlapping

clinical characteristics. In the study population, coronary aneurysms and

ectasia co-existed, however, only 14.9% of patients presented with both

conditions. The CAA group had a higher proportion of female patients, was older,

and was more likely to have undergone cardiac surgery than the CAE group. A similar

prevalence of inflammatory and oncological conditions was found in both groups.

A trend toward higher hs-CRP in the CAA group was also found, suggesting a higher

prevalence of residual inflammatory risk [10, 11].

Angiographic characteristics also varied

among groups. CAAs were primarily localised in a single vessel, whereas CAE

exhibited a multi-district distribution in nearly half of the cases. The

distribution of CAA was relatively balanced among the three major coronary

arteries, except for the giant form, which was almost invariably located in the

right coronary artery. Conversely, CAE was most frequently located in the right

coronary artery (46.9% of cases). Furthermore, CAAs had a more extensive

representation along the coronary tree, also appearing at the level of diagonal

and marginal side branches, a trait not observed in CAE cases. Nevertheless,

coronary ectasia had, in 79.0% of cases, a diffuse manifestation (i.e. type 1,

type 2 or type 3) with the involvement of more than one segment along the epicardial

vessel.

Coronary aneurysms and ectasia present different clinical

and risk profiles

The scientific literature regarding

clinical outcomes in patients with dilated coronary artery disease is typically

sparse, often biased by varying anatomical definitions and inclusion criteria,

and marked by controversial conclusions. Luo et al. demonstrated a lower

coronary flow (quantified in terms of TIMI frame counts) in patients with CAA

compared to those with CAE, suggesting that impaired intravascular haemodynamics

could lead to ischaemia [12]. Núñez-Gil et al. reported that morbidity and

mortality rates in large European and North American populations with CAA

exceeded 30% and 15%, respectively [9]. Several studies have indicated worse

post-procedural outcomes in the form of dilated coronaropathy than obstructive coronary

artery disease [2]. However, a comprehensive comparison of long-term clinical

outcomes in patients presenting with either CAA or CAE has not been adequately

addressed.

Our longitudinal analysis of patient

outcomes specifically underscored the distinct clinical behaviour of CAAs and

CAEs. In our cohort, patients with angiographically identified CAAs

demonstrated worse clinical outcomes than those with CAEs. This was not only

indicated by a higher incidence of acute coronary syndrome during follow-up but

also by an increased rate of coronary re-interventions involving dilated

coronary segments and other normal coronary artery segments. The Cox

proportional hazards regression analysis further corroborated these findings,

revealing that aneurysmal coronary artery segments were associated with a

significantly higher risk of adverse events and major adverse cardiovascular

events, predominantly driven by a higher incidence of acute coronary syndrome

and a subsequent requirement for a percutaneous coronary intervention during

follow-up. This was observed in a mixed, real-world study population where

patients were equally treated operatively and conservatively at baseline.

Elevated rate of stent failure in dilated coronary

disease

The high rates of in-stent restenosis and

stent thrombosis in our cohort were noteworthy. Considering only the sub-group

of patients who underwent a percutaneous coronary intervention at the baseline

coronary angiography, the rates of in-stent restenosis and stent thrombosis

were recorded at 9.8% and 2.5%, respectively, over a median follow-up period of

18.9 months. In particular, one-third of the recorded stent failures occurred

in stents positioned within a dilated coronary artery segment, where in-stent

restenosis and stent thrombosis rates reached 22.2% and 1.8%, respectively. The

causes of stent failure within an enlarged vessel segment may be secondary to

procedural factors, such as sub-optimal stent apposition, stent fracture or

edge dissection due to forceful post-dilation or a lack of post-procedural

imaging control [13]. Aneurysm ceilings with covered stents were rare, performed

in two out of nineteen treated CAAs. However, the reasons for the increased

risk in non-dilated coronary artery segments are less clear. Potential factors

could be alterations in intra-coronary haemodynamics, such as a decreased flow

speed downstream of a coronary aneurysm or secondary flow patterns with blood

re-circulation and platelet activation [14–16]. Alongside these factors, the

presence of a biologically favourable environment with heightened

pro-inflammatory activity – as the registered elevated hs-CRP levels might

suggest – could also play a role in affecting the long-term performance of

stents in these patients [17]. Larger studies are needed to substantiate the

evidence of an elevated stent failure rate in this population and to properly

address its aetiology.

Limitations

This study acknowledges several

limitations. Firstly, patient selection was executed using a comprehensive

system query based on pre-defined keywords rather than a visual examination of

each coronary angiography performed at our institution. Nevertheless,

considering the extensive timeframe for patient inclusion (15 years) and the numerous

operators performing angiography procedures, the risk of selection bias is

minimal. Secondly, the classification of CAA or CAE was based on visual

assessments of the coronary angiograms rather than intravascular imaging (e.g.

intravascular ultrasound or optical coherence tomography). Consequently, the

precision of the assessment may be impaired, and the inadvertent inclusion of

coronary pseudoaneurysms cannot be ruled out. However, the implemented

methodology better represents current routine clinical practice. Third, the

study lacks a comparative analysis with a control group with obstructive coronary

artery disease without CAA/CAE. However, it should be noted that obstructive coronary

artery disease prevalence in the investigated cohort was large. This fact, in

conjunction with the high prevalence of traditional risk factors for coronary

artery disease, implies a significant overlap between the two types of coronary

diseases, making a direct comparison less informative. Finally, the observed

increased risk associated with CAA could be partially attributed to the longer

follow-up period for this group (a median follow-up duration of 713 days)

compared to the CAE group (a median follow-up duration of 543 days), highlighting

the importance of considering the follow-up duration when interpreting these

results.

Conclusions

Aneurysmatic coronary segments presented a

more aggressive clinical course compared to coronary ectasia, emphasising the

need for a nuanced approach to patient management that also accounts for the

different manifestations of dilative coronary artery disease. Further research

is necessary to elucidate the mechanisms behind these divergent outcomes and to

develop targeted therapeutic strategies for patients presenting with either

form of dilated coronary artery disease.

Prof. Christian Templin, MD, PhD, FESC

Department of Cardiology and Internal Medicine B

University Medicine Greifswald

Ellernholzstraße 1/2

DE-17489 Greifswald

ch.templin[at]gmx.de

References

1. Stary HC. Natural history and histological classification of atherosclerotic lesions:

an update. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000 May;20(5):1177–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/01.ATV.20.5.1177

2. Kawsara A, Núñez Gil IJ, Alqahtani F, Moreland J, Rihal CS, Alkhouli M. Management

of Coronary Artery Aneurysms. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018 Jul;11(13):1211–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2018.02.041

3. Falk E. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Apr;47(8 Suppl):C7–12.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.068

4. Antoniadis AP, Chatzizisis YS, Giannoglou GD. Pathogenetic mechanisms of coronary

ectasia. Int J Cardiol. 2008 Nov;130(3):335–43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.05.071

5. Scott DH. Aneurysm of the coronary arteries. Am Heart J. 1948 Sep;36(3):403–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-8703(48)90337-8

6. Núñez-Gil IJ, Nombela-Franco L, Bagur R, Bollati M, Cerrato E, Alfonso E, et al.;

CAAR Investigators. Rationale and design of a multicenter, international and collaborative

Coronary Artery Aneurysm Registry (CAAR). Clin Cardiol. 2017 Aug;40(8):580–5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.22705

7. Syed M, Lesch M. Coronary artery aneurysm: a review. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1997;40(1):77–84.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-0620(97)80024-2

8. Vergallo R, Crea F. Atherosclerotic Plaque Healing. N Engl J Med. 2020 Aug;383(9):846–57.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra2000317

9. Núñez-Gil IJ, Cerrato E, Bollati M, Nombela-Franco L, Terol B, Alfonso-Rodríguez E,

et al.; CAAR investigators. Coronary artery aneurysms, insights from the international

coronary artery aneurysm registry (CAAR). Int J Cardiol. 2020 Jan;299:49–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.05.067

10. Carrero JJ, Andersson Franko M, Obergfell A, Gabrielsen A, Jernberg T. hsCRP Level

and the Risk of Death or Recurrent Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Myocardial

Infarction: a Healthcare-Based Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019 Jun;8(11):e012638. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.012638

11. Candreva A, Matter CM. Is the amount of glow predicting the fire? Residual inflammatory

risk after percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur Heart J. 2022 Feb;43(7):e10–3.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy729

12. Luo Y, Tang J, Liu X, Qiu J, Ye Z, Lai Y, et al. Coronary Artery Aneurysm Differs

From Coronary Artery Ectasia: Angiographic Characteristics and Cardiovascular Risk

Factor Analysis in Patients Referred for Coronary Angiography. Angiology. 2017 Oct;68(9):823–30.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0003319716665690

13. Esposito L, Di Maio M, Silverio A, Cancro FP, Bellino M, Attisano T, et al. Treatment

and Outcome of Patients With Coronary Artery Ectasia: Current Evidence and Novel Opportunities

for an Old Dilemma. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022 Feb;8:805727. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.805727

14. Fan T, Zhou Z, Fang W, Wang W, Xu L, Huo Y. Morphometry and hemodynamics of coronary

artery aneurysms caused by atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2019 May;284:187–93.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.03.001

15. Kuramochi Y, Ohkubo T, Takechi N, Fukumi D, Uchikoba Y, Ogawa S. Hemodynamic factors

of thrombus formation in coronary aneurysms associated with Kawasaki disease. Pediatr

Int. 2000 Oct;42(5):470–5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1442-200x.2000.01270.x

16. Burns JC, Glode MP, Clarke SH, Wiggins J Jr, Hathaway WE. Coagulopathy and platelet

activation in Kawasaki syndrome: identification of patients at high risk for development

of coronary artery aneurysms. J Pediatr. 1984 Aug;105(2):206–11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3476(84)80114-6

17. Niccoli G, Montone RA, Ferrante G, Crea F. The evolving role of inflammatory biomarkers

in risk assessment after stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010 Nov;56(22):1783–93.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2010.06.045

Appendix

The appendix is available in the pdf version of the article at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.3857.