Core stories of physicians on a Swiss internal medicine ward during the first COVID-19

wave: a qualitative exploration

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.3760

Vanessa Kraegea,

Amaelle Gavinb,

Julieta Norambuenac,

Friedrich Stiefeld*,

Marie Méane*,

Céline Bourquind*

a Division of Internal medicine, Medical Directorate

and Innovation and Clinical Research Directorate, Lausanne University Hospital,

Lausanne, Switzerland

b Psychiatric Liaison Service, Lausanne

University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland

c Division of Internal medicine, Lausanne

University Hospital, Lausanne,Switzerland

d Psychiatric

Liaison Service, Lausanne University Hospital, and University of Lausanne, Lausanne,

Switzerland

e Division

of Internal medicine, Lausanne University Hospital, and University of Lausanne,

Lausanne, Switzerland

* This authors contributed

equally as co-last authors

Summary

INTRODUCTION: The first COVID-19 wave (2020), W1, will remain extraordinary due to

its novelty and the uncertainty on how to handle the pandemic. To understand

what physicians went through, we collected narratives of frontline physicians

working in a Swiss university hospital during W1.

METHODS: Physicians in the Division of Internal Medicine of Lausanne

University Hospital (CHUV) were invited to send anonymous narratives to an

online platform, between 28 April and 30 June 2020. The analysed material

consisted of 13 written texts and one audio record. They were examined by means

of a narrative analysis based on a holistic content approach, attempting to

identify narrative highlights, referred to as foci, in the texts.

RESULTS: Five main foci were identified: danger and threats, acquisition of

knowledge and practices, adaptation to a changing context, commitment to the

profession, and sense of belonging to the medical staff. In physicians’

narratives, danger designated

a variety of rather negative feelings and emotions, whereas threats were experienced as being

dangerous for others, but also for oneself. The acquisition of knowledge and practices focus referred to the

different types of acquisition that took place during W1. The narratives that

focused on adaptation reflected how physicians coped with W1 and private

or professional upheavals. COVID-19 W1 contributed to revealing a natural commitment

(or not) of physicians towards the profession and patients, accompanied by the

concern of offering the best possible care to all. Lastly, sense of

belonging referred to the team and its reconfiguration during W1.

CONCLUSIONS: Our study deepens the understanding of how physicians experienced

the pandemic both in their professional and personal settings. It offers

insights into how they prepared and reacted to a pandemic. The foci reflect

topics that are inherent to a physician’s profession, whatever the context. During

a pandemic, these foundational elements are particularly challenged.

Strikingly, these topics are not studied in medical school, thus raising the

general question of how students are prepared for the medical profession.

Introduction

Physicians work in an emotionally demanding

and stressful environment [1, 2], with a

lower overall quality of life compared to the general population [2–7]. Over the last

decades, studies have

shown an alarming decrease in physicians’ wellbeing [2, 3, 8, 9], which also impacts

quality and functioning of

healthcare [10–12].

The rise in health emergencies caused by

viral outbreaks such as SARS (2002), H1N1 influenza (2009–2010) and COVID-19 (since

2020) has shown that physicians involved in crisis response are particularly

exposed. Depending on the intensity of the upheaval, they can subsequently

suffer from psychological disorders [13–17].

If not properly apprehended, these disorders can become chronic [13, 14, 18]. Previous

studies have attempted

to identify stressors and coping strategies for healthcare professionals’

mental health during viral outbreaks [13, 14,

16, 19–24]. These studies mostly used multiple-choice questionnaires or

standardised forms focusing on specific outcomes, such as prevalence of

post-traumatic stress disorder [20, 25]

or coping strategies [26], burnout [20, 25, 26], anxiety or depressive symptoms

(HADS) [25], leaving little room for the

expression of personal experiences.

The first COVID-19 wave (2020), W1, will

remain extraordinary due to its novelty, the uncertainties it brought about how

to handle the pandemic and the societal upheavals it caused. Despite the

importance of comprehending what physicians and other healthcare professionals

went through, only very few qualitative studies were conducted across the

world.

We hereby briefly summarise the results of

relevant studies with regard to ours. At the very beginning of the pandemic

(February 2020), Liu et al. [27] analysed

semi-structured telephone interviews of nurses and physicians in China. They

identified three main thematic categories: the sense of tremendous professional

responsibility, having to adapt to a completely new context and associated

feelings, and the role of support in resilience. In

Italy, De Leo et al. [28] focused on

protective and risk factors in nurses and physicians and identified three

levels: a personal history level (intrinsic/ethical motivation and role

flexibility versus extrinsic

motivation and role staticity), an interpersonal level (perception of

supportive relationships with colleagues, patients and family versus poor relationships) and an organisational

level (good leadership and sustainable work purpose versus absence of managerial support and undefined or confused

tasks). In Iran, Ardebili et al. [29]

identified four main themes based on the analysis of semi-structured interviews

of a wide variety of healthcare professionals: working in the pandemic era and

associated experiences; changes in personal life and enhanced negative affect; gaining

experience, normalisation and adaptation to the pandemic; and mental health

considerations. Parsons et al. [30]

investigated Canadian physicians’ perceptions and experiences in the context of

the pandemic. They found that resources were strained by continuously evolving

pandemic conditions, which not only gave rise to safety concerns and practice

changes, but also had personal and professional implications [30]. In the United Kingdom,

Bennett et al. [31]

collected experiences of frontline NHS workers during COVID-19 W1 through a

website, where physicians, nurses and physiotherapists left a story. A central

aspect of their findings was the experience and psychological consequences of

trauma.

The main themes identified by these studies

can thus be categorised into (a) positive and negative individual experiences

and ways in which healthcare workers coped and adapted (their “inner world”), (b)

the role of relationships in this sanitary crisis (their “relational” or

“interpersonal world”), both professional and private

and (c) considerations regarding the context (institutional organisation and

healthcare system or their “outer world”).

Given that physicians’ experiences are also

influenced by the healthcare context and cultural determinants [31], we considered

it important to conduct a

qualitative study aiming to explore what frontline physicians went through

during W1, using narratives of physicians working in a Swiss university hospital.

Indeed, to the best of our knowledge, the only other Swiss qualitative study,

by Merlo et al., focused exclusively on physicians’ acceptance of triage

guidelines during the pandemic [32],

whereas other Swiss studies were mostly based on surveys [19, 33].

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted in Lausanne

University Hospital (CHUV; www.chuv.ch),

one of the five medical teaching hospitals of Switzerland. The CHUV has over 1400

beds and 45,000 hospitalisations

per year. The Division of Internal Medicine treats approximately 6200 patients

per year in non-pandemic times and has 165 beds organised in eight wards, each

staffed with one attending physician, one senior physician and up to three

medical residents. During the first wave, it had up to 216 patients simultaneously.

By 30 June 2020, 540 COVID-19 patients had been hospitalised at the CHUV, of whom

two thirds had been looked after in the Internal Medicine Division. To put

these numbers into perspective, on 26 June 2020, the five Swiss university

hospitals had a total COVID-19 bed capacity of 2423 beds and had treated 2175 COVID-19

patients [34].

Data collection

Data were collected between 28 April and 30

June 2020. During W1 of the COVID-19 pandemic, 136 physicians (i.e. residents,

senior and attending physicians) were working in the Internal

Medicine Division, where they provided care to approximately 600 COVID-19 patients

as well as non-COVID-19 patients. Whether they took care of COVID-19 patients

or not, or whether they were originally employed on the ward as internists or

had come from other specialty wards to help during the pandemic, they all

received invitations to participate in the study by email (initial email on 27 April

2020, followed by three

reminders on 8 May, 12 June and 26 June), flyers or during personal

encounters with two of the authors (VK, MM). The PENbank team (three of the authors:

AG, FS, CB)

implemented a temporary online platform, as part of a larger project (at

the time, still in development) of a permanent repository for CHUV physicians’

narratives of experience (see below) [35].

This platform served to collect internal medicine physicians’ narratives. The software

Sphinx IQ2 allowed secure and anonymous transfer

of files (narratives); participants were instructed to avoid people’s names, be

they of colleagues, patients or themselves. Physicians were invited to recount

their experiences of the COVID-19 crisis, without any other imposed themes or

guidelines on how to proceed. Several formats were possible: written texts

(typed, photographed/scanned handwritten texts), audio recordings (using a

voice changer application if desired) and artistic representations

(photographed/scanned paintings, drawings or photos). File size had to be less

than 13 Mb, which corresponds to approximately 15 to 20 minutes of audio.

Optional information included function (resident, senior or

attending physician), sex and age group.

PENbank

In brief, the PENbank project was funded by

a Spark grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF CRSK-3_190887/1).

PENbank is a bank for narratives specifically dedicated to physicians’

experiences of medicine and of being a physician. It is a unique means to collect

and organise narrative material on a large scale and over time. PENbank

serves as an observatory providing a voice and visibility to physicians’

experiences and feedback to hospital management authorities, as well as a data

resource for researchers.

Since 2021, PENbank has taken the form of a

website (https://penbankchuv.ch/)

allowing physicians from the CHUV and Unisanté (Lausanne Center for Primary

Care and Public Health) to securely and anonymously send oral, written or

visual narratives, recounting their experiences.

Data analysis

Written data, including verbatim transcriptions

of audio recordings, were examined by means of a narrative analysis based on a

holistic content approach [36]. Lieblich

et al. developed a framework which distinguishes between holistic and categorical

analysis of narratives as well as between content and form [36, 37]. In this study, we adopted a holistic

approach putting the focus on the individual story of each participant, and

considering each story as a whole, which implies interpreting the parts within

it relative to other parts of the story [36, 37].

The “content” dimension of the approach means that attention was centred on

what was put into play in the narrative (vs on the structure of narratives) [36].

The entire interdisciplinary team – which

consisted of three internists (VK, JN, MM), a senior liaison psychiatrist (FS),

a research psychologist (AG) and a social scientist (CB) – carried out the

analysis. Following the analytical process described by Lieblich et al. [36], the

team read the material iteratively

until foci of content of the entire narratives were identified. Foci are nodal

points of the narratives or, to put it differently, the “core stories”. For

Lieblich, “A special focus is frequently distinguished by the space devoted to

the theme in the text, its repetitive nature, and the number of details the

teller provides about it. However, omissions of some aspects in the story, or

very brief reference to a subject, can sometimes also be interpreted as indicating

the focal significance of the topic” [36].

The foci were then reviewed and further described and defined, based on their

significance (repetitive nature, level of detail provided, devoted space in the

text, etc.). Team discussions, in small (FS, CB, AG) or

large groups, were conducted throughout the study, to fine-grain the analysis

and perform the interpretive work.

Informed consent

The call for narratives was accompanied by

a detailed participation information form. Participants were advised that by

submitting an anonymous narrative, they consented to their text being stored in

PENbank and used for research and in publications. The Ethics Committee of the

Canton of Vaud exempted the study from ethical review. The study protocol was

not registered in any registry.

Results

The collected material consisted of 14

photographs, 13 texts and one audio-recorded narrative in French; we

transcribed the audio-recorded narrative verbatim. As photo analysis cannot be

carried out in the same way as text analysis, nor answer the same research

questions, this material will be used as part of another study. The length of

the 14 included narratives ranged from 39 to 3556 words, with a median word count

of 248. They were more often by senior residents or attending physicians aged between

30 and 40 years and originated as much from women as from men (see table 1).

Table 1Characteristics of participating physicians

and of the narrative material.

| General characteristics |

Total

narratives received |

Excluded narratives |

Included narratives |

| Total |

28 |

14 photos |

14 (13 texts; 1 audio) |

| Sex |

Female |

20 (71%) |

13 (93%) |

7 (50%) |

| Male |

8 (29%) |

1 (7%) |

7 (50%) |

| Age |

20–30 |

2 (7%) |

0 |

2 (14%) |

| 30–40 |

20 (72%) |

8 (57%) |

12 (86%) |

| Not specified |

6 (21%) |

6 (43%) |

0 |

| Experience

level |

Students

working as residents & Residents |

6 (21%) |

1 (7%) |

5 (36%) |

| Senior

residents & Attending

Physicians |

22 (79%) |

13 (93%) |

9 (64%) |

Five main or “core” foci were identified in

the narratives: danger and threats; acquisition of knowledge and practices; adaptation

to a changing context; commitment to the profession; and sense of belonging to

the medical staff. The foci are described below, illustrated and supported by

verbatim quotes. For the purposes of this publication, one of the authors (VK),

a native English speaker, translated the narratives that appear below into English

Danger and threats

When the focus of physicians’ narratives

referred to danger, it designated a

variety of rather negative feelings and emotions, such as fear, worry, anxiety

and vulnerability. Threats were

experienced as being dangerous for others, but also for oneself. “Others” were

close relatives (family, friends) or acquaintances such as neighbours:

A plague-stricken person, who precisely because of this work is […]

at risk of being a carrier of THE virus. And therefore, a persona non grata.

It’s a very particular feeling to feel excluded, rejected, unwelcome, when one

has done nothing. (Narrative 5)

When danger concerned the narrating

physicians themselves, emotions and feelings were conveyed, triggered by

uncertainty and/or the threat, and coloured by a feeling of helplessness facing

an inevitable, unavoidable, incoming catastrophe.

So, here we go. It’s the beginning of the wave. On 23.03.2020, the

exponential hospitalisations that we had been expecting all week arrive at the

hospital: 7014 cases confirmed in the country before noon, 1676 cases in our

region, 91 hospitalised here, 14 of them in intensive care, meaning 20

hospitalisations in 24 hours. They doubled in 48 hours and we expect them to

double again in less than 12 hours.[…] We’ve been admitting patients like crazy since

this weekend.

I think it’s about time to stop fooling around and to stay home for good. Avoid

kissing your parents, because for those who will be ill in 2 weeks’ time, it

may well be tense! (Narrative 5)

Anticipatory fear and anxiety, coming from the media who convey

dramatic images from China, Italy or elsewhere... At the beginning of the

crisis, I cannot deny that there was some fear, some anxiety. One must not

forget that the media regularly reported the death of health professionals.

Thus, one could see tributes on social networks paid to these professionals who

died in combat. So many portraits, so many names of colleagues working a few

hundred kilometres from “home”. In these conditions, my fear was legitimate

because I was convinced that I would catch the disease sooner or later. (Narrative 10)

Strategies deployed by physicians to

reassure themselves and prepare to face and manage the danger, were also part

of these narratives. The analogy drawn between preparing for the arrival of the

COVID-19 virus and its patients, and getting ready for a battle, war or a

natural disaster, is reflected for instance in this story:

From that day on, there was this phase, a little bit – very strange

(.) It was as if I felt like I was some kind of army waiting for the arrival of

the enemy, we were building our trenches, we were emptying some units. […] it

was very weird to see those empty floors and – and at that point, I think at

least a week passed during which I did not see any COVID patients, I didn’t

even know what they could look like. But

(.) But I – but we – we were getting ready. And then, uh, I think it lasted a

week, a very stressful phase for me because we didn’t know what to expect, I

think that from one day to the next I said to myself “but what will we – I end up

doing… I don’t know, me, in the

overflowing floors, with patients everywhere filling the hospital, in a sort of

disaster.” (Narrative 11)

Narratives were also about warning others

of the danger:

And then – then, I think it was a phase for me when, when really,

when I said to everyone “be careful because it’s a dangerous disease, don’t try

and act smart but stay home”. For me, it was, it had become clear, it was

almost militant. (Narrative 11)

Another strategy was rationalisation, which

aimed to keep the danger at bay. In these narratives, we find statements

saying, for example, that as the situation had been anticipated, everything

would be fine, or that a sort of “Swiss invincibility” would prevail. Danger

was linked to emotions other than fear, such as anger or guilt, when faced with

the behaviour of others confronted with danger or with flaws in one’s own

behaviour or strategies:

Catching damn COVID without really knowing how, reconsidering one’s

own hospital and personal hygiene, and especially spending 10 days of

confinement being afraid of having generously gifted it to colleagues over the

last few days. (Narrative 13)

Acquisition of knowledge and practices

Acquisition

of knowledge and practices, as a focus, refers to

the different types of acquisition that took place during W1, such as learning

new daily life routines, both in professional and personal settings. For

example, priority lanes were set up for hospital staff to enter the hospital,

badge checks put into place and mask distribution introduced, together with

constant reminders of the importance of barrier gestures. At home, advanced

hygiene measures and social distancing suddenly became the new norm.

Gradually, we enter a new work routine. We carefully avoid public

transport. We observe these new rituals of tireless hand disinfection,

sometimes until they nearly burn. We put on our mask, think about what we touch

and try to avoid the unfortunate act that would make us fall sick. Rituals and

procedures repeat themselves, take time and tire us over time. They are taken

home. Clean area, dining area. Separate laundry. Separate rooms also to limit

contact with one’s own spouse, believing it possible to fall ill oneself

without contaminating one’s loved ones… Contrasting feelings: binding rituals

but also purifying. (Narrative 10)

Acquisition also concerned lessons learnt

about life in general. Narratives depicted the crisis as a revealer of usually

invisible mechanisms and behaviours, both positive and negative. They mentioned

eye-opening discoveries on unshakable age-old hospital administrative

constraints but also on colleagues’ characters. These life lessons allow for a

more informed and critical gaze at hospital organisation, co-workers and human

behaviour.

Lots of fine words at the start of the crisis, but ultimately, in

reality, the “me I” often dominated. […] Other more discreet people […] did

everything they could to help and enquire about how their colleagues were

doing. All the more touching. Certain people’s abilities and qualities were

revealed, amplified and made to stand out. On the contrary, a feeling that

others could not find their place, did not know what to do, were completely

overwhelmed, and remained as discreet and withdrawn as possible so as not to be

noticed, sometimes only to resurface with their complaints at the end of the

crisis. Amplification of incompetence / operating problems that were usually camouflaged

and ignored. (Narrative 15)

The COVID-19 experience also brought along

thoughts on societal awareness, such as the limits of globalisation,

self-introspection and priorities that guide life choices.

Deep questioning on our way of living, on the priorities that we

give (health, work, family), on the way in which the world struggles, is organised,

conducts clinical trials, publishes the results of research, on information and

disinformation. (Narrative 12)

Finally, acquisition may concern a new

personal philosophy for everyday life:

I’m living this period of time at a standstill, day by day. Alone,

of course, but day by day, and I think I appreciate it. It’s a life philosophy

that I have tried to acquire over the past few months.

Carpe Diem. Live the present day, for the past cannot be changed and

the future is filled with potential opportunities that nothing can anticipate,

despite what one would like to believe. (Narrative

5)

Adaptation to a changing context

The narratives that focus on adaptation

reflect the different ways in which physicians coped with W1 and private or

professional upheavals.

The foci adaptation and acquisition

refer to distinct phenomena. Indeed, while the acquisition of knowledge or

skills mobilise cognitive and practical processes, adaptation also depends on

psychological processes such as coping or defence mechanisms.

The stories fall between the recounting of experiences

of successful evolution and the recollection of failed adaptation. Adaptation

can be experienced as an evolution from a first phase, full of uncertainties,

stress and psychological fatigue, to one of a tamed situation, having thus

reduced stress.

A second phase, after adaptation and acceptance of constraints. I

tamed relationships through video conferences, physical distancing and changes

in interaction modes. Improving knowledge about the virus allowed me to reduce

my stress in my clinical management. (Narrative 1)

Conversely, in some stories, boredom,

intellectual understimulation, jealousy and frustration alluded to

non-adaptation or an inability to adapt.

A frustrating and uncomfortable situation, because the population

sees us a bit like heroes, while in the field, the organisational work was

intense but carried out by a small group of people. But our daily work is not

worth such applause.

Frustrating to see some colleagues working a lot in organising/reorganising

and therefore learning a lot. (Narrative 2)

Certain narratives also took a particularly

optimistic turn with the underlying idea of a certain improvement thanks to

COVID-19, with more solidarity between people, and public support for hospitals

and health professionals. Adaptation also included positive increase of

awareness due to the crisis, both as a professional and as a society, for

example in relation to the climate crisis.

Dear Coronavirus,

[…] And yet, the optimist that I am cannot help but notice the

positivity in this crisis: solidarity in my neighbourhood, support for

hospitals and, strangely enough, we could even say belatedly but also

foolishly, recognition for the daily and flawless work of healthcare teams

[...] So thank you coronavirus for having shaken up the obvious, thank you for

also questioning our economic, spiritual and ecological certainties… in the end

I think we needed it a bit. (Narrative 4)

Commitment to the profession

For some physicians, an exceptional

situation, such as COVID-19 W1, is needed to reveal a

natural/obvious/self-evident commitment (or not) towards the profession and

patients, accompanied by the concern of offering the best possible care to all.

I like my job and I do it with the same commitment whether in COVID

or non-COVID times, and, like me, hundreds of thousands of other caregivers do

so. For us, this is a certainty, but for others apparently it wasn’t... (Narrative 4)

This commitment, which seems obvious,

transcended distance: some physicians, even prior to the beginning of the

crisis, did everything they could to join their colleagues in the COVID-19

units. Commitment also transcended fear, as illustrated in this extract:

Despite the fear, I never doubted the role I had to play, I never

doubted for a second the need to commit myself on the wards, at patients’

bedside and within the teams. After all, no one else doubted. Everyone in our

teams responded, regardless of the media’s alarm signals. (Narrative 10)

Moreover, the various expressions of the public’s

gratitude expressed during W1 (applause, “Thank you” notes and gifts sent to

hospitals) as well as the accompanying heroification of health professionals,

also triggered commitment. Finally, some physicians resented being treated like

heroes, as they considered that they were only doing their job.

Sense of belonging to the medical staff

Sense of belonging refers to the team and

its reconfiguration during W1. In some narratives, the feeling of not having

been part caused frustration and envy/jealousy towards the “elected”, who

experienced the crisis intensely and learnt a lot. In other narratives, views

on team membership and roles played are more settled and less emotional,

reflecting an ability to “get on with it”.

In line with the sense of belonging or not,

some physicians felt less deserving according to the position they held, with

two different scenarios: (a) I am not deserving because I was not chosen to be

part of the frontline group, and (b) I fulfilled my tasks, but in my opinion, this

is nothing special and

I find it hard to think of myself as especially deserving.

During that time, I stay in my unit. My “usual” patients need

someone with my skills to take care of them and my role will be to stay at my

post, that’s how it is. From a distance I will see my colleagues at the front

scramble with the wave of patients and novelties,

while I am spared […] How can we welcome the applause and messages of support

if we do nothing for the collective effort? (Narrative

6)

The COVID-19 crisis also implied recalling people

who were no longer part of the team (specialists, physicians from private

practices, etc). We thus found narratives about fellowship and a galvanising

sense of collective belonging, to face this historical event together:

Returning to medicine after two years of specialty training was a

pleasure, full of nice memories, of a department that taught me so much on all

levels... It was a great pleasure to be part of this historic event in the

fight against this virus! (Narrative 3)

Discussion

Our study of accounts by frontline

physicians working during W1 in a Swiss university hospital, examined by means

of a narrative analysis based on a holistic content approach, highlights five

main foci: danger and threats; acquisition of knowledge and practices; adaptation

to a changing context; commitment to the profession; and sense of belonging to

the medical staff.

Given their different aims, designs and

methods, it is somewhat difficult to compare the findings of qualitative studies

on clinicians’ W1 COVID-19 experiences. Moreover, some studies include all

healthcare professionals, whereas others (the overwhelming majority) concentrate

on either nurses or physicians [38–43]. In

this regard, Villa et al., who examined the experience of healthcare providers

using a longitudinal approach, emphasised the importance of understanding the “profession-specific

experiences”

during the COVID-19 outbreak [44].

More specifically, some studies focus on frontline physicians

fighting the pandemic, while others on those with less contact with COVID-19

patients. There are however core areas of experiences concerning the inner, the

interpersonal and the outer world of physicians, which run through these

studies and the narratives we collected.

Indeed, we found experiences related to

physicians’ inner world (foci: danger, acquisition, adaptation and commitment);

in the literature on experiences of healthcare staff caring for patients with

COVID-19, special attention was paid to the risk of burnout and compassion

fatigue and to the need to both build resilience among professionals [45, 46] and

mitigate the repeated trauma

exposure [47]. In our study, we also

found experiences connected to the interpersonal world (focus: belonging). Existing

qualitative studies highlighted important changes in personal life due to

working in a pandemic era [48], such as

social connection deterioration and inability to manage family obligations [49]. On

a professional level, Gonzales et al. shed

light on the importance for physicians to be involved by their leadership in

the decision-making processes [50]. More

positively, studies demonstrated the impact of gratitude, solidarity and faith on

the personal and professional life of physicians [51]. At the same time, a new need

for personal fulfilment emerged [51]. Research also showed that frontline

healthcare workers’ experiences during COVID-19 resonated with experiences of

previous epidemics/pandemics [52].

However, unlike in other studies, the

institutional and healthcare contexts were rarely mentioned in our narratives,

or rather in a positive way (Swiss preparedness for the pandemic). This may be

explained by a relatively well-staffed Swiss healthcare system due to the

comfortable economic situation of the country [53].

In contrast, studies conducted for instance in Pakistan [54], Bangladesh [55] or

Jordan [45] offer lessons and address organisational/administrative

challenges for hospitals in

low- or middle-income countries. This illustrates the need to consider the

local and national context when investigating physicians’ experiences.

A specificity of our study was that all

physicians who were working in the Internal Medicine Division during W1 were

invited to participate, whether they were in charge of COVID-19 patients or

not. This is reflected in the material, as not all narratives recount

experiences of physicians overwhelmed by the gravity of patient situations and

outcomes, allowing other dimensions to emerge. An important contribution of

this study relies on the fact that data consisted of (almost)

“naturally-occurring narratives”, and were not framed by investigators’

questions, thus revealing matters of interest, satisfaction and concern of

physicians during W1. A similar approach was adopted by Lackman-Zeman et al., [46]

who used web-enabled audio diaries.

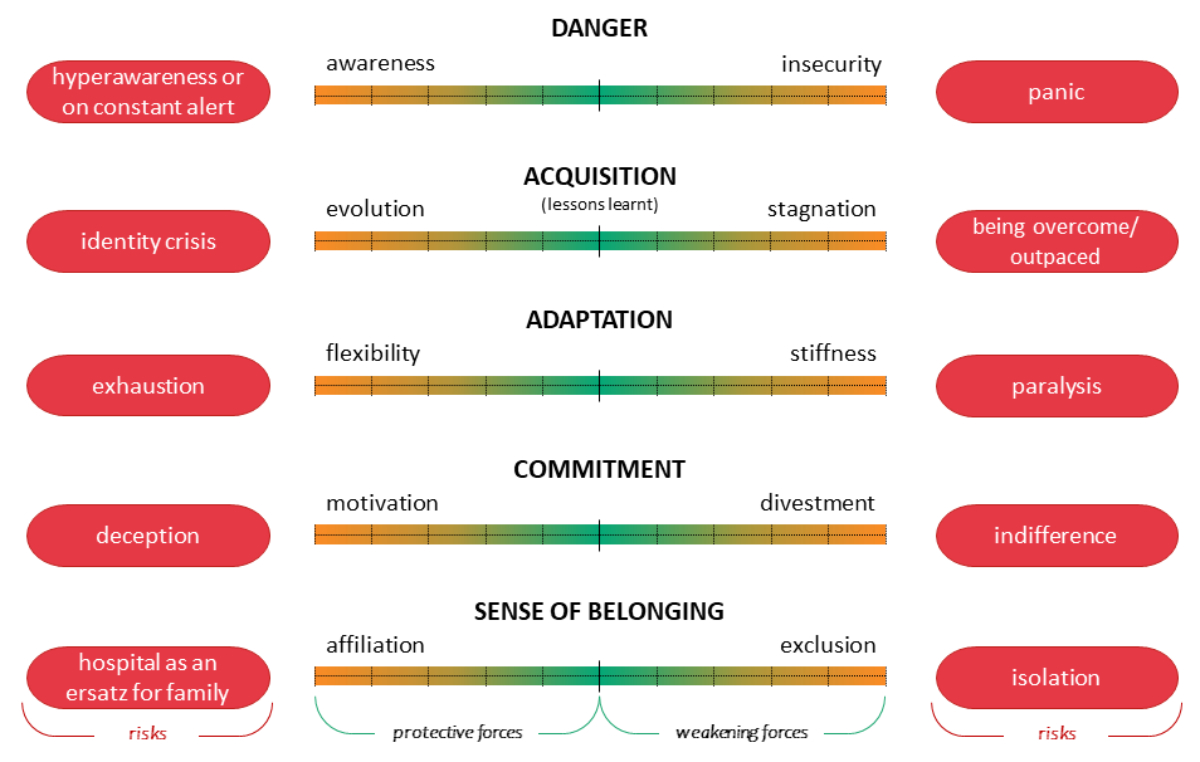

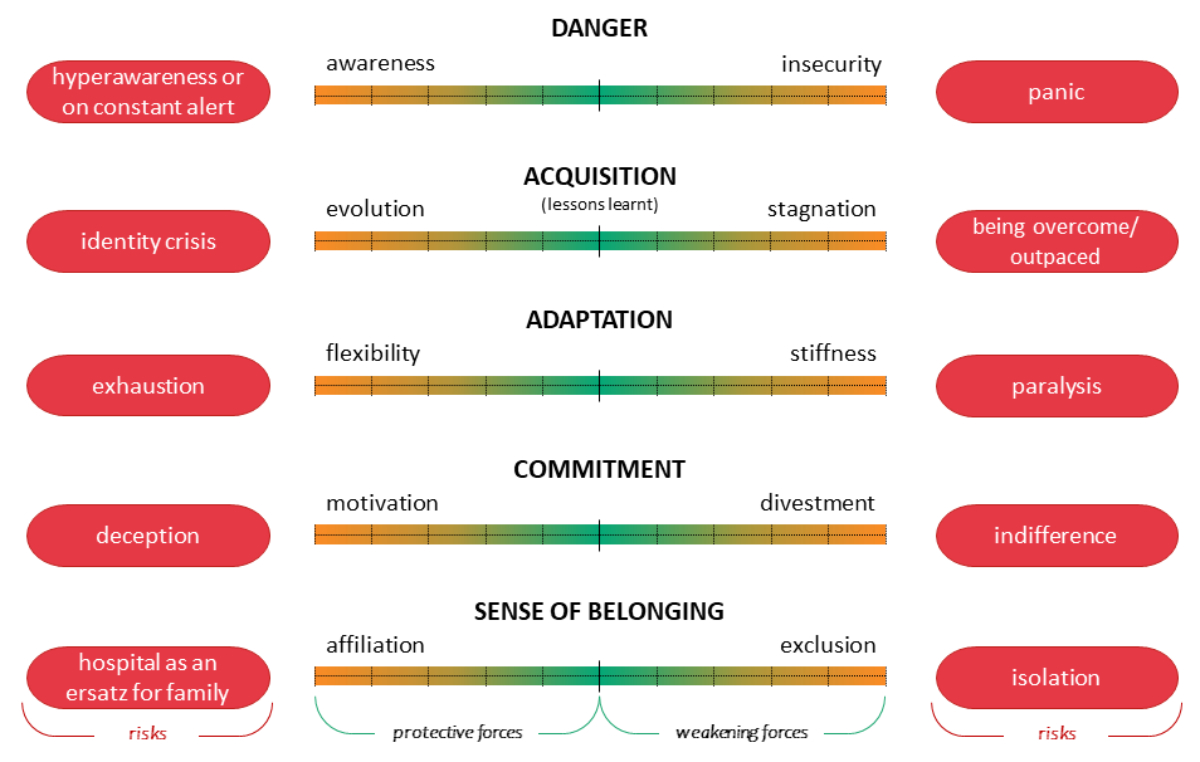

To reflect the clinical relevance of our

results and to provide field feedback to the senior staff members of the CHUV Internal

Medicine Division, a grid (see figure 1) based on the results was developed in

an attempt to situate physicians’ reactions to this crisis. The five foci were

considered to illustrate the transformational effect of the crisis on as many

levels. We also assumed that physicians’ narratives conveyed something about

the stances that they adopted or considered adopting. Seen like this, danger

oscillated between adequate awareness and a justified feeling of insecurity on

their part. Some physicians felt they were evolving by acquiring knowledge and

practical experiences, whereas others felt that they were stagnating. Challenged

by the need to adapt, physicians displayed varying levels of flexibility and of

rigidity. In some, the crisis triggered motivation, whereas in others, disengagement

prevailed. Lastly, regarding the interpersonal dimensions, physicians could

either feel increased affiliation or exclusion. These polarised stances were

represented on a spectrum in the grid.

Figure 1Physicians’ experiences during the first

COVID-19 wave. The grid shows a spectrum for each of the 5 foci. The greener

the colour, the better the equilibrium. The more orange the colour, the greater

the risk of an unbalanced equilibrium, which can reach the extreme

polarisations in red.

This grid can be a means to explore the

experiences of clinicians who seem to be doing well but who may be silently

drifting towards the poles of the spectrum of one or more reactions. Indeed,

experiences that feel positive (left side of the figure) also harbour the

danger of turning into problematic attitudes (see red boxes in figure 1). This

grid could also be used to explore clinicians’ experiences in ordinary times, especially

when entering the profession and facing multiple challenges and demands.

Ultimately, the foci reflect topics that

are inherent to a physician’s profession, whatever the context, such as lifelong

never-ending learning, adjustment to every single patient or situation,

commitment to a prosocial job, feeling of belonging to a medical corporation or

guild, and care for safety and risk management, underlining the omnipresence of

danger. In times of tension, as in a pandemic, these foundational elements are

particularly challenged. Strikingly, these topics are not studied in medical

school, thus raising the general question of how students are prepared for the

medical profession, which surpasses the application of clinical skills, and how

young physicians are supervised and mentored. Conveying knowledge is of utmost

importance, but transmitting experience of how to cope with the challenges of

the profession is fundamental.

Our study presents the following

limitations. It is monocentric and focuses on “only” 14 narratives, by

physicians on an internal medicine ward during W1. However, it allowed

qualitative in-depth exploration of experiences reported by physicians at the

beginning of this unprecedented sanitary crisis. Moreover, the material was

solid, giving voice to physicians with different levels of responsibility and a

detailed description

of their experiences. Furthermore, data saturation was reached with the

collected material.

Conclusion

Our study deepens understanding of how

physicians experienced the pandemic both in professional and personal settings.

It offers insights into the manner in which they prepared for a pandemic, coped

with danger, needed to acquire new knowledge and to adapt, and felt a sense of

belonging and of commitment.

Lessons learnt from the COVID-19 pandemic

should nourish reflections about other existing and most likely accelerating

crises, such as the climate and energy crises. Indeed, whatever the crisis, fragilisation

is a consequence,

leading to polarised reactions, as we showed in this study.

Open Science

Physicians who uploaded narratives

anonymously did not consent to share them openly. We deposited the dataset with

restricted access on Zenodo [DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.8318857],

the platform used by the Faculty of Biology and

Medicine of the CHUV. Access can be requested by contacting Celine.Bourquin[at]chuv.ch.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Céline

Maglieri for her help with the bibliography.

Author contributions: Design and conception of the study: Céline Bourquin, Friedrich

Stiefel, Vanessa Kraege, Marie Méan. Methodology: Céline Bourquin, Friedrich

Stiefel, Amaelle Gavin. Analyses: Vanessa Kraege, Céline Bourquin, Friedrich Stiefel,

Amaelle Gavin, Marie Méan, Julieta Norambuena. Manuscript drafting: Vanessa

Kraege, Céline Bourquin, Amaelle Gavin, Friedrich Stiefel, Julieta Norambuena. Manuscript

revision: Vanessa Kraege, Céline Bourquin, Amaelle Gavin, Friedrich Stiefel,

Marie Méan.

Vanessa Kraege

Medical Directorate

Lausanne University Hospital

BU-21-06-247

Rue du

Bugnon 21

CH-1011

Lausanne

vanessa.kraege[at]chuv.ch

References

1.Kumar S. Burnout and Doctors: Prevalence, Prevention and Intervention. Healthcare

(Basel). 2016 Jun;4(3):37. 10.3390/healthcare4030037

2.Raj KS. Well-Being in Residency: A Systematic Review. J Grad Med Educ. 2016 Dec;8(5):674–84.

10.4300/JGME-D-15-00764.1

3.Pulcrano M, Evans SR, Sosin M. Quality of Life and Burnout Rates Across Surgical Specialties:

A Systematic Review. JAMA Surg. 2016 Oct;151(10):970–8. 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.1647

4.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, et al. Burnout

and career satisfaction among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2009 Sep;250(3):463–71.

10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ac4dfd

5.Ding J, Jia Y, Zhao J, Yang F, Ma R, Yang X. Optimizing quality of life among Chinese

physicians: the positive effects of resilience and recovery experience. Qual Life

Res. 2020 Jun;29(6):1655–63. 10.1007/s11136-020-02414-8

6.Tyssen R, Hem E, Gude T, Grønvold NT, Ekeberg O, Vaglum P. Lower life satisfaction

in physicians compared with a general population sample : a 10-year longitudinal,

nationwide study of course and predictors. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009 Jan;44(1):47–54.

10.1007/s00127-008-0403-4

7.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D, et al. Burnout and satisfaction

with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population.

Arch Intern Med. 2012 Oct;172(18):1377–85. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199

8.Van Ham I, Verhoeven AA, Groenier KH, Groothoff JW, De Haan J. Job satisfaction among

general practitioners: a systematic literature review. Eur J Gen Pract. 2006;12(4):174–80.

10.1080/13814780600994376

9.Zumbrunn B, Stalder O, Limacher A, Ballmer PE, Bassetti S, Battegay E, et al. The

well-being of Swiss general internal medicine residents. Swiss Med Wkly. 2020 Jun;150(2324):w20255.

10.4414/smw.2020.20255

10.Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Trojanowski L. The relationship between physician burnout

and quality of healthcare in terms of safety and acceptability: a systematic review.

BMJ Open. 2017 Jun;7(6):e015141. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015141

11.Tawfik DS, Scheid A, Profit J, Shanafelt T, Trockel M, Adair KC, et al. Evidence Relating

Health Care Provider Burnout and Quality of Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.

Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct;171(8):555–67. 10.7326/M19-1152

12.Scheepers RA, Boerebach BC, Arah OA, Heineman MJ, Lombarts KM. A Systematic Review

of the Impact of Physicians’ Occupational Well-Being on the Quality of Patient Care.

Int J Behav Med. 2015 Dec;22(6):683–98. 10.1007/s12529-015-9473-3

13.Stuijfzand S, Deforges C, Sandoz V, Sajin CT, Jaques C, Elmers J, et al. Psychological

impact of an epidemic/pandemic on the mental health of healthcare professionals: a

rapid review. BMC Public Health. 2020 Aug;20(1):1230. 10.1186/s12889-020-09322-z

14.Serrano-Ripoll MJ, Meneses-Echavez JF, Ricci-Cabello I, Fraile-Navarro D, Fiol-deRoque MA,

Pastor-Moreno G, et al. Impact of viral epidemic outbreaks on mental health of healthcare

workers: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020 Dec;277:347–57.

10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.034

15.Maunder R, Hunter J, Vincent L, Bennett J, Peladeau N, Leszcz M, et al. The immediate

psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital.

CMAJ. 2003 May;168(10):1245–51.

16. Maunder, R., et al., The experience of the 2003 SARS outbreak as a traumatic stress

among frontline health-care workers in Toronto: lessons learned. SARS: a case study

in emerging infections, 2005: p. 96-106. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198568193.003.0013

17.Huang CL. Underrecognition and un-dertreatment of stress-related psychiatric disorders

in physicians: Determinants, challenges, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

World J Psychiatry. 2023 Apr;13(4):131–40. 10.5498/wjp.v13.i4.131

18.Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Balderson KE, Bennett JP, Borgundvaag B, Evans S, et al. Long-term

psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS

outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006 Dec;12(12):1924–32. 10.3201/eid1212.060584

19.Spiller TR, Méan M, Ernst J, Sazpinar O, Gehrke S, Paolercio F, et al. Development

of health care workers’ mental health during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in Switzerland:

two cross-sectional studies. Psychol Med. 2022 May;52(7):1395–8. 10.1017/S0033291720003128

20.Lee SM, Kang WS, Cho AR, Kim T, Park JK. Psychological impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak

on hospital workers and quarantined hemodialysis patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2018 Nov;87:123–7.

10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.10.003

21.Fukuti P, Uchôa CL, Mazzoco MF, Corchs F, Kamitsuji CS, Rossi L, et al. How Institutions

Can Protect the Mental Health and Psychosocial Well-Being of Their Healthcare Workers

in the Current COVID-19 Pandemic. Clinics (São Paulo). 2020 Jun;75:e1963. 10.6061/clinics/2020/e1963

22.Zaka A, Shamloo SE, Fiorente P, Tafuri A. COVID-19 pandemic as a watershed moment:

A call for systematic psychological health care for frontline medical staff. J Health

Psychol. 2020 Jun;25(7):883–7. 10.1177/1359105320925148

23.Demartini K, Konzen VM, Siqueira MO, Garcia G, Jorge MS, Batista JS, et al. Care for

frontline health care workers in times of COVID-19. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2020;53:e20200358.

10.1590/0037-8682-0358-2020

24.Ganguli I, Chang Y, Weissman A, Armstrong K, Metlay JP. Ebola risk and preparedness:

a national survey of internists. J Gen Intern Med. 2016 Mar;31(3):276–81. 10.1007/s11606-015-3493-1

25.Lancee WJ, Maunder RG, Goldbloom DS; Coauthors for the Impact of SARS Study. Prevalence

of psychiatric disorders among Toronto hospital workers one to two years after the

SARS outbreak. Psychiatr Serv. 2008 Jan;59(1):91–5. 10.1176/ps.2008.59.1.91

26.Phua DH, Tang HK, Tham KY. Coping responses of emergency physicians and nurses to

the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. Acad Emerg Med. 2005 Apr;12(4):322–8.

10.1197/j.aem.2004.11.015

27.Liu Q, Luo D, Haase JE, Guo Q, Wang XQ, Liu S, et al. The experiences of health-care

providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: a qualitative study. Lancet Glob Health.

2020 Jun;8(6):e790–8. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30204-7

28.De Leo A, Cianci E, Mastore P, Gozzoli C. Protective and risk factors of Italian healthcare

professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak: a qualitative study. Int J Environ

Res Public Health. 2021 Jan;18(2):453. 10.3390/ijerph18020453

29.Eftekhar Ardebili M, Naserbakht M, Bernstein C, Alazmani-Noodeh F, Hakimi H, Ranjbar H.

Healthcare providers experience of working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative

study. Am J Infect Control. 2021 May;49(5):547–54. 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.10.001

30.Parsons Leigh J, Kemp LG, de Grood C, Brundin-Mather R, Stelfox HT, Ng-Kamstra JS,

et al. A qualitative study of physician perceptions and experiences of caring for

critically ill patients in the context of resource strain during the first wave of

the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021 Apr;21(1):374. 10.1186/s12913-021-06393-5

31.Bennett P, Noble S, Johnston S, Jones D, Hunter R. COVID-19 confessions: a qualitative

exploration of healthcare workers experiences of working with COVID-19. BMJ Open.

2020 Dec;10(12):e043949. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043949

32.Merlo F, Lepori M, Malacrida R, Albanese E, Fadda M. Physicians’ acceptance of triage

guidelines in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Front Public

Health. 2021 Jul;9:695231. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.695231

33.Aebischer O, Weilenmann S, Gachoud D, Méan M, Spiller TR. Physical and psychological

health of medical students involved in the coronavirus disease 2019 response in Switzerland.

Swiss Med Wkly. 2020 Dec;150(4950):w20418. 10.4414/smw.2020.20418

34. Bureaux du secrétariat général Médecine Universitaire Suisse, Pandémie de coronavirus

: le bilan des cinq hôpitaux universitaires de Suisse 2020.

35.Bourquin C, Gavin A, Stiefel F. La liaison psychiatrique I : clinique. Rev Med Suisse.

2022 Feb;18(769):261–4. 10.53738/REVMED.2022.18.769.261

36.Lieblich A, Tuval-Mashiach R, Zilber T. Narrative research: Reading, analysis, and interpretation. Vol. 47. 1998: Sage. 10.4135/9781412985253

37.Beal CC. Keeping the story together: a holistic approach to narrative analysis. J

Res Nurs. 2013;18(8):692–704. 10.1177/1744987113481781

38.Copel LC, Lengetti E, McKeever A, Pariseault CA, Smeltzer SC. An uncertain time: clinical

nurses’ first impressions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Res Nurs Health. 2022 Oct;45(5):537–48.

10.1002/nur.22265

39.Deliktas Demirci A, Oruc M, Kabukcuoglu K. ‘It was difficult, but our struggle to

touch lives gave us strength’: the experience of nurses working on COVID-19 wards.

J Clin Nurs. 2021 Mar;30(5-6):732–41. 10.1111/jocn.15602

40.Firouzkouhi M, Abdollahimohammad A, Rezaie-Kheikhaie K, Mortazavi H, Farzi J, Masinaienezhad N,

et al. Nurses’ caring experiences in COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review of qualitative

research. Health Sci Rev (Oxf). 2022 Jun;3:100030. 10.1016/j.hsr.2022.100030

41.Polinard EL, Ricks TN, Duke ES, Lewis KA. Pandemic perspectives from the frontline-The

nursing stories. J Adv Nurs. 2022 Oct;78(10):3290–303. 10.1111/jan.15306

42.Specht K, Primdahl J, Jensen HI, Elkjaer M, Hoffmann E, Boye LK, et al. Frontline

nurses’ experiences of working in a COVID-19 ward-A qualitative study. Nurs Open.

2021 Nov;8(6):3006–15. 10.1002/nop2.1013

43.Xu H, Stjernswärd S, Glasdam S. Psychosocial experiences of frontline nurses working

in hospital-based settings during the COVID-19 pandemic - A qualitative systematic

review. Int J Nurs Stud Adv. 2021 Nov;3:100037. 10.1016/j.ijnsa.2021.100037

44.Villa G, Dellafiore F, Caruso R, Arrigoni C, Galli E, Moranda D, et al. Experiences

of healthcare providers from a working week during the first wave of the COVID-19

outbreak. Acta Biomed. 2021 Oct;92 S6:e2021458.

45.Nazzal MS, Oteir AO, Jaber AF, Alwidyan MT, Raffee L. Lived experience of Jordanian

front-line healthcare workers amid the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. BMJ

Open. 2022 Aug;12(8):e057739. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057739

46.Lackman Zeman L, Roy S, Surnis PP, Wasserman JA, Duchak K, Homayouni R, et al. Paradoxical

experiences of healthcare workers during COVID-19: a qualitative analysis of anonymous,

web-based, audio narratives. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2023 Dec;18(1):2184034.

10.1080/17482631.2023.2184034

47.Harris S, Jenkinson E, Carlton E, Roberts T, Daniels J. “It’s Been Ugly”: A Large-Scale

Qualitative Study into the Difficulties Frontline Doctors Faced across Two Waves of

the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Dec;18(24):13067. 10.3390/ijerph182413067

48.Eftekhar Ardebili M, Naserbakht M, Bernstein C, Alazmani-Noodeh F, Hakimi H, Ranjbar H.

Healthcare providers experience of working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative

study. Am J Infect Control. 2021 May;49(5):547–54. 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.10.001

49.Mehedi N, Ismail Hossain M. Experiences of the Frontline Healthcare Professionals

Amid the COVID-19 Health Hazard: A Phenomenological Investigation. Inquiry. 2022;59:469580221111925.

10.1177/00469580221111925

50.Gonzalez CM, Hossain O, Peek ME. Frontline Physician Perspectives on Their Experiences

Working During the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Gen Intern Med. 2022 Dec;37(16):4233–40.

10.1007/s11606-022-07792-y

51.Adams GC, Reboe-Benjamin M, Alaverdashvili M, Le T, Adams S. Doctors’ Professional

and Personal Reflections: A Qualitative Exploration of Physicians’ Views and Coping

during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Mar;20(7):5259.

10.3390/ijerph20075259

52.Billings J, Ching BC, Gkofa V, Greene T, Bloomfield M. Experiences of frontline healthcare

workers and their views about support during COVID-19 and previous pandemics: a systematic

review and qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021 Sep;21(1):923. 10.1186/s12913-021-06917-z

53. OECD. Revenue Statistics, The Impact of Covid-19 on OECD Tax Revenues, 1965-2021.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development; 2022.

54.Shahil Feroz A, Pradhan NA, Hussain Ahmed Z, Shah MM, Asad N, Saleem S, et al. Perceptions

and experiences of healthcare providers during COVID-19 pandemic in Karachi, Pakistan:

an exploratory qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2021 Aug;11(8):e048984. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-048984

55.Das Pooja S, Nandonik AJ, Ahmed T, Kabir ZN. “Working in the Dark”: Experiences of

Frontline Health Workers in Bangladesh During COVID-19 Pandemic. J Multidiscip Healthc.

2022 Apr;15:869–81. 10.2147/JMDH.S357815