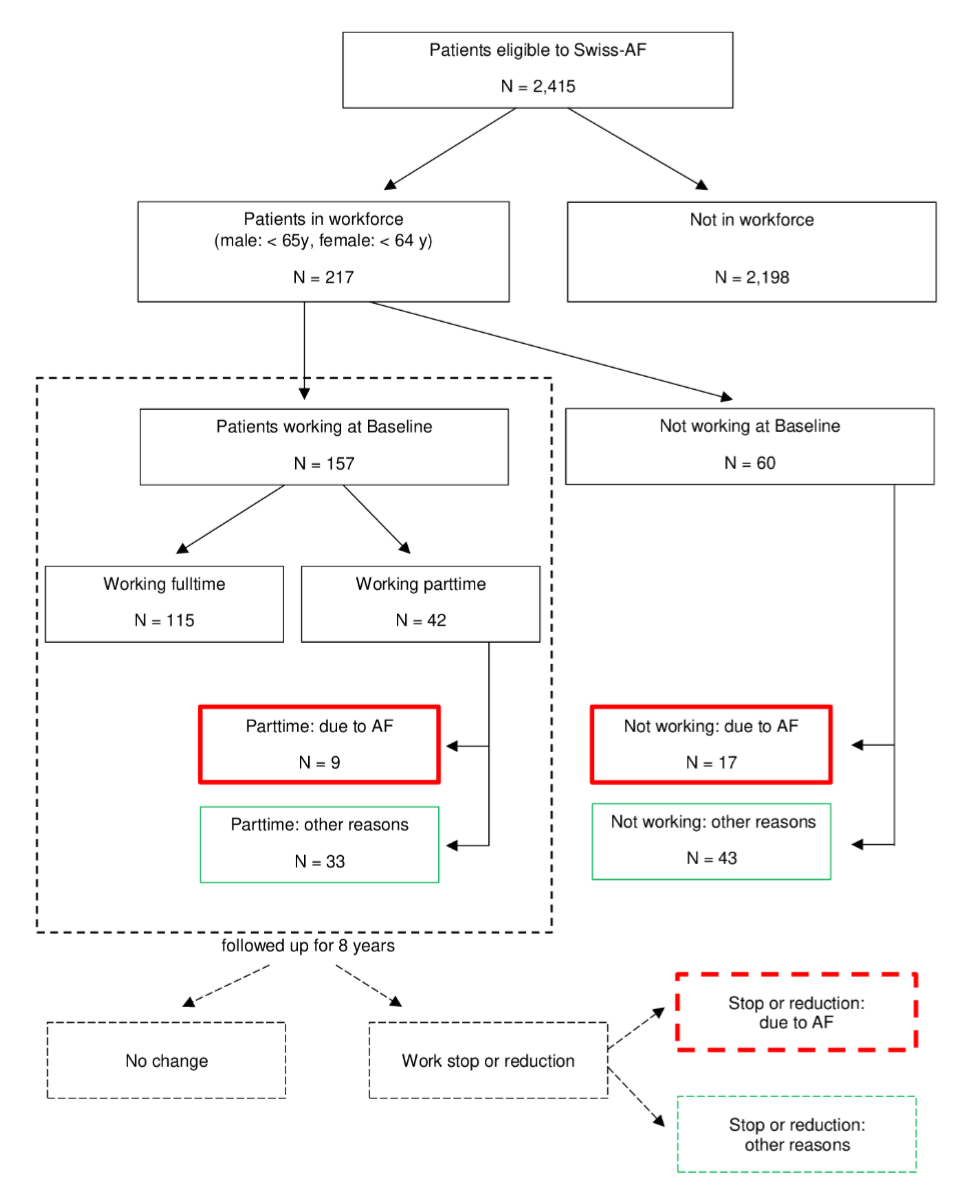

Figure 1Patient selection flowchart. AF: atrial fibrillation, Swiss-AF: Swiss Atrial Fibrillation prospective cohort study.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.3669

body mass index

risk of stroke for non-valvular atrial fibrillation (Congestive Heart failure, Hypertension, Age (2 points), Diabetes mellitus, Stroke (2 points), Vascular disease, Age, Sex category)

Swiss Federal Statistical Office

Swiss labour force survey

standardised mean difference

Swiss Atrial Fibrillation prospective cohort study

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common serious arrhythmia worldwide and is associated with a broad range of symptoms and complications, including major complications such as stroke, heart failure and dementia [1]. Depending on disease severity, atrial fibrillation-related symptoms or complications can substantially affect a patient’s daily life activities [2]. With regard to younger atrial fibrillation patients under the age of retirement, an important open question is whether and how atrial fibrillation symptoms and complications affect professional activity and employment, and cause indirect costs to society due to lost productivity.

A previous study from the US investigated the association of atrial fibrillation with productivity losses. Compared to employees without atrial fibrillation, employees with atrial fibrillation were shown to have significantly more annual days missed due to sick leave and short-term disability, but no difference was found for long-term disability [3].A Danish study estimated a 19.9% sex- and age-standardised probability of dismissal from employment within 6 months after atrial fibrillation patients had returned to work in their first year after diagnosis [4]. Overall, evidence on the impact on productivity specifically due to atrial fibrillation is scarce. Considering a broader range of conditions, a UK study showed that hypertension and cardiovascular diseases were associated with health-related job loss in men but not in women [5]. A Dutch study showed that circulatory system-related health problems predicted unemployment in employees aged 45–64 years [6]. To our knowledge, no data on the impact of atrial fibrillation on productivity is available for Switzerland.

The aim of the present study was to explore the impact of atrial fibrillation on productivity in working-age atrial fibrillation patients in Switzerland, using data from a cohort of patients aged 45–65 years at enrolment. Specific objectives were to quantify the evolution of productivity losses due to atrial fibrillation, and to estimate resulting indirect costs by comparison with a population-based, matched sample from the Swiss labour force survey (SLFS).

We analysed data from the prospective, multicentre, observational Swiss Atrial Fibrillation cohort study (Swiss-AF). Swiss-AF enrolled patients with documented atrial fibrillation between April 2014 and August 2017, across 14 clinical centres in Switzerland. The cohort comprised mainly patients aged 65 years or older. To assess the socioeconomic implications of atrial fibrillation in working-age adults, an additional group of 228 patients aged 45–65 years was enrolled, via the specialised clinical centres recruiting into Swiss-AF. From these 228 patients, productivity-related information was collected for up to 8 years; 11 of the patients were excluded from the present analysis because, while still working, they were already above the legal retirement age. In addition to a large variety of patient and clinical characteristics, Swiss-AF collected health economic data during yearly study visits, including data on changes in professional activity and absenteeism due to atrial fibrillation for these younger patients. The detailed study setup has been described earlier [7]. Patients were included in the present analysis if they had baseline data on their working status and were below the legal retirement age (65 for men, 64 for women). Patients reaching retirement age during follow-up were censored at the respective time point.

At baseline, working-age patients were asked if they were currently employed and, if yes, whether they worked part-time or full-time. Patients not employed or working part-time were further asked whether this was due to atrial fibrillation. During their yearly Swiss-AF follow-up visits, patients were asked if and how their professional activity level had changed since their previous visit. If there had been a change, they were further asked about the reason (atrial fibrillation, retirement or other reason). Additionally, they were asked how many days of work they had missed due to atrial fibrillation (without counting days missed for study visits) and how many hours they would have worked on the respective days. The reasons for changes in professional activity were self-reported and if a patient attributed such a change to atrial fibrillation, we considered it to be linked to the disease. To enable comparison of the Swiss-AF patients with the general population, anonymous data from the Swiss labour work survey was provided by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (SFSO). Cross-sectional SLFS data was available for the years 2014–2021. Since 1991, the SLFS carries out the SFSO every year with the aim of providing information on the structure of the labour force and employment patterns in Switzerland. Invited survey participants are randomly selected from the permanent resident population aged ≥15 (including apprentices), based on the SFSO’s sample register. SLFS participants are interviewed four times within one and a half years (with the exception of those aged over 75 years who are interviewed only once), leading to around 120,000 interviews yearly [8]. Questions cover, among other things, professional activity, reasons for non-activity, educational background, profession, place of work, degree of employment, working hours and salary level [9]. Variables included in the analysis were taken from the subpopulation that excluded apprentices.

After data preparation, consistently defined variables were extracted from the Swiss-AF and SLFS datasets and merged into one patient-level dataset. Using the variables age, sex and year, both populations were matched to assess atrial fibrillation-related indirect costs. Details of the statistical analyses are described below.

Our primary endpoint was the occurrence of a patient-reported, atrial fibrillation-related change in professional activity (stop or reduction) either prior to baseline or during the 8-year follow-up period. All patients who reported that they had stopped or reduced their professional activity but not due to atrial fibrillation were assigned to “Other reasons” (figure 1). A patient could be categorised as both.

Our secondary outcomes included the proportion of patients with a work stop, proportion of patients with a work reduction and days off work due to atrial fibrillation. To further characterise the societal impact of atrial fibrillation, we described differences between the Swiss-AF patients and the SLFS population representing the general population in terms of changes in professional activity (stop or reduction) and degree of professional activity. We planned to estimate average income differences, interpretable as indirect costs of atrial fibrillation, in case of relevant differences in professional activity between the Swiss-AF patients and the SLFS population.

Analyses were purely descriptive. Baseline characteristics of patients with and without an atrial fibrillation-related change in professional activity, occurrence and characteristics of changes in professional activity, and times off work due to atrial fibrillation were presented with mean and standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed variables, median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous non-normally distributed variables and n (%) for categorical variables. Evolution over the full observation period of atrial fibrillation-related vs Other reason-related professional activity changes was depicted in a bar chart. As a measure of effect size, the standardised mean difference (SMD) between the compared populations was used, defined as the difference between the group means divided by the standard deviation of the pooled groups. An SMD around 0.2 is generally considered as small, around 0.5 as medium and 0.8 or higher as large.

Time to first occurrence of an atrial fibrillation-related change in professional activity was depicted in dependence of disease duration and years before reaching retirement age. Days off work were calculated by the number of days missed multiplied by the hours the patient would have worked during those days. A Swiss average workday is 8.4 hours and was assumed for missing entries of working hours.

For each visit, members of the SLFS population were matched 10:1 to the Swiss-AF-patients, by year (i.e. if a Swiss-AF visit occurred in 2018, then matching partners were drawn from the 2018 SLFS dataset), age and sex. To ensure stable results, the matching was performed for different random seeds and results were compared for consistency. As a sensitivity analysis, education was added to the matching variables. The evolution of average degree of employment, proportion of the population working and average degree of employment of the population working across the full observation period were tabulated.

Data management, preprocessing and all statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.1 (64 bits). Details can be found on https://gitlab.uzh.ch/helena.aebersold/af-on-productivity-swiss-af-cohort.git

Swiss-AF was approved by Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz (2014-067, PB_2016-00793) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Use of the SLFS data was regulated by a contract with the SFSO, who determined that ethical approval was not required. The Swiss-AF study is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02105844).

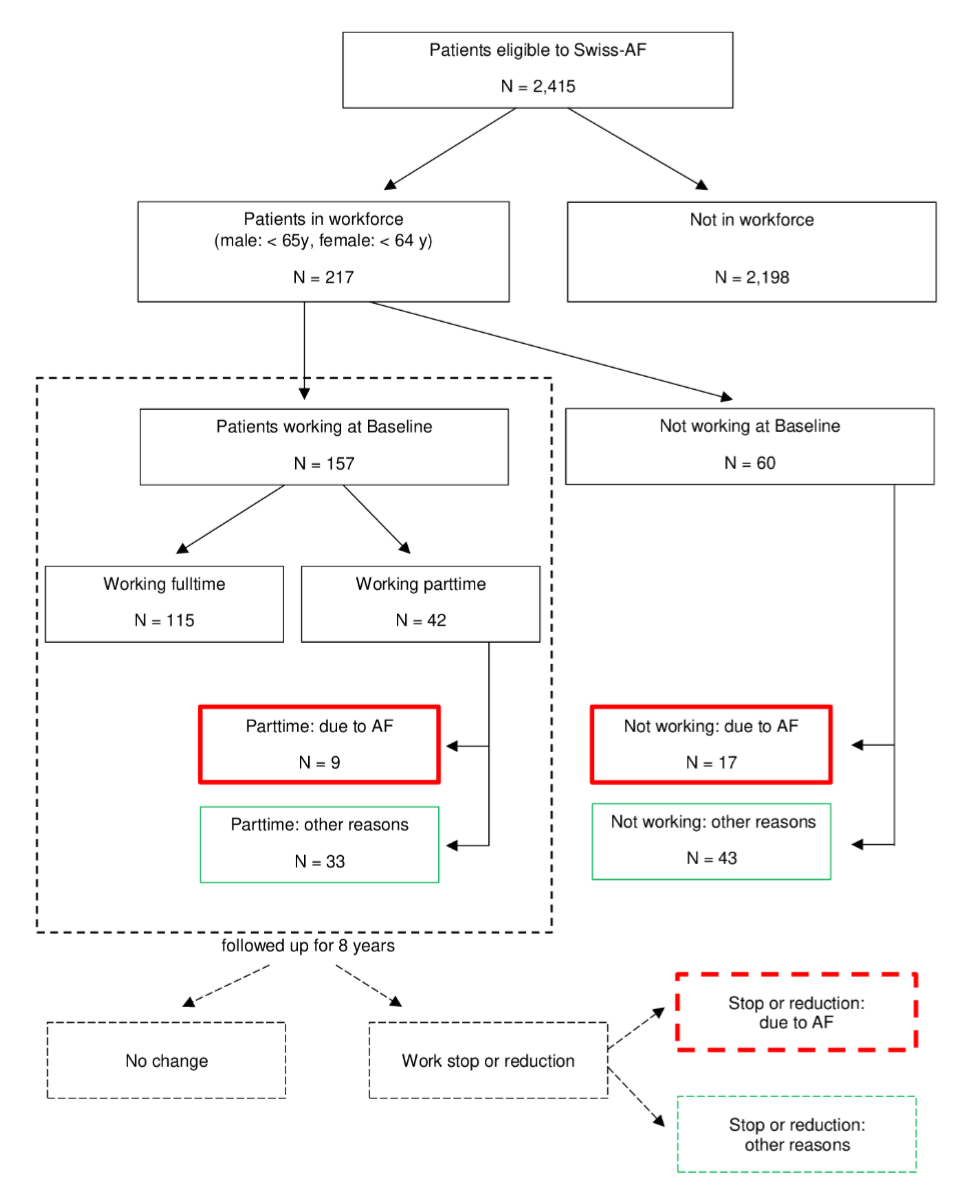

Of 2415 Swiss-AF patients, 217 (9.0%) were enrolled below the age of retirement and were included in the analysis (figure 1). Of these patients, 26 (12.0%) reported at enrolment (baseline) that they either did not work (n = 17 or 7.8%) or had reduced their work (n = 9 or 4.2%) due to atrial fibrillation (figure 2 “Baseline”). Overall, 32 patients, 14.7% of the analysed population, reported a professional activity change due to atrial fibrillation prior to or after baseline (20 reported at least one stop, 12 reported at least one reduction, 1 reported both). The total number of patients with a professional activity change for other reasons was 94 (43.3%; 48 stops, 46 reductions). For 76 (35.0%) patients, this change had already occurred prior to baseline (43 stops, 33 reductions). Of the 157 patients who were working at baseline (full- or part-time), 6 (3.8%) indicated a professional activity change due to atrial fibrillation (3 stops, 3 reductions) before they reached retirement age or the end of the observation period and 18 (11.6%) due to other reasons (5 stops, 13 reductions) (figure 2 “Follow-up 1 – Follow-up 8”).

Figure 1Patient selection flowchart. AF: atrial fibrillation, Swiss-AF: Swiss Atrial Fibrillation prospective cohort study.

Figure 2Evolution over time of atrial fibrillation (AF)-related professional activity change. Baseline includes all professional activity changes up to and including baseline. FU: follow-up.

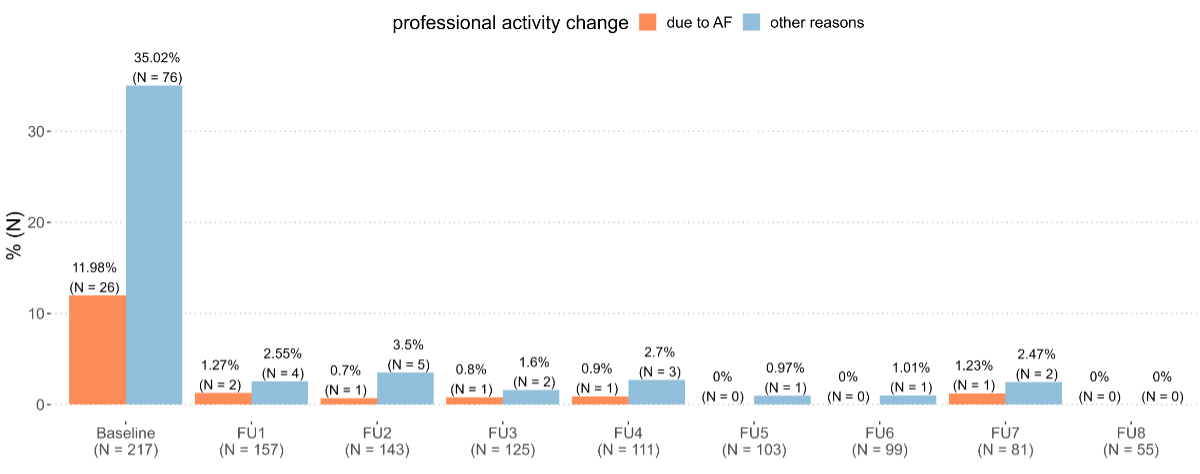

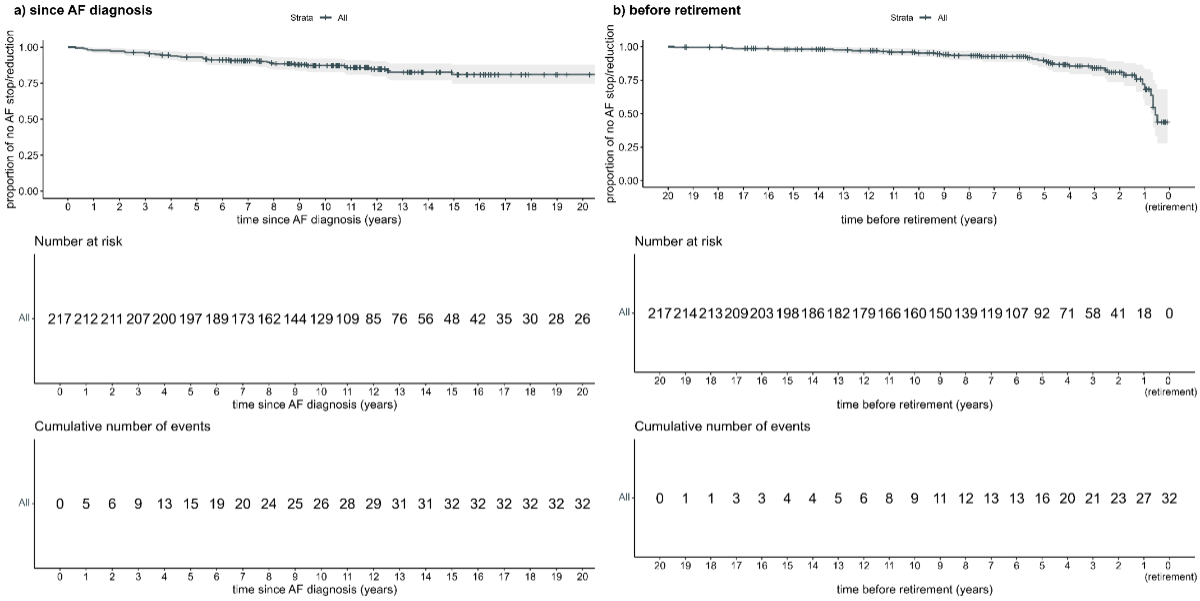

The occurrence of no professional activity change due to atrial fibrillation decreased slightly but constantly with increasing disease duration (appendix figure S1A). This means that the longer patients had had atrial fibrillation, the more likely they were to report an impact of atrial fibrillation on their professional activity. When looking at the occurrence of no professional activity change due to atrial fibrillation in relation to the years until retirement (appendix figure S1B), a steeper decrease was seen within six years before retirement. Patients were thus more likely to report a professional activity change due to atrial fibrillation in the years close to their retirement.

Table 1 compares patients with (n = 32) and without (n = 185) atrial fibrillation-related professional activity change. Patients with atrial fibrillation-related professional activity change had a higher BMI (median 30.6 [IQR 27.3–32.8] vs 27.7 [IQR 25.6–31.8]), a higher CHA₂DS₂-VASc Score (2.00 [1.00–3.00] vs 1.00 [0.00–2.00]) and were more likely to have sleep apnoea (40.6% vs 18.9%). With respect to medical therapy, they were more likely to be receiving statins (50.0% vs 28.6%) and diuretics (50.0% vs 29.7%). There were no differences in terms of age, sex, previous pulmary vein isolation or electroconversion and in a wide range of comorbidities and socioeconomic variables.

Table 1Baseline characteristics of patients with and without atrial fibrillation-related professional activity change. Physical activity: engagement in any regular physical activity (e.g. jogging, biking, aerobic). A standardised mean difference (SMD) around 0.2 is generally considered small, an SMD around 0.5 as medium and an SMD of 0.8 or higher is considered large.

| With | Without | |||

| n | 32 | 185 | Standardised mean difference (SMD) | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 59.45 (52.37–62.61) | 58.25 (54.71–61.67) | 0.008 | |

| Sex: Female, n (%) | 26 (81.2%) | 151 (81.6%) | 0.01 | |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 30.59 (27.26–32.78) | 27.67 (25.56–31.80) | 0.374 | |

| Type of atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 0.036 | |||

| Paroxysmal | 16 (50.0%) | 94 (50.8%) | ||

| Permanent | 4 (12.5%) | 21 (11.4%) | ||

| Persistent | 12 (37.5%) | 70 (37.8%) | ||

| Atrial fibrillation symptoms, n (%) | 23 (71.9%) | 141 (76.2%) | 0.099 | |

| Years since atrial fibrillation diagnosis, median (IQR) | 4.33 (2.29–7.54) | 4.56 (3.00–8.36) | 0.257 | |

| CHA₂DS₂-VASc, median (IQR) | 2.00 (1.00–3.00) | 1.00 (0.00–2.00) | 0.438 | |

| Previous history of major bleeding, n (%) | 2 (6.2%) | 5 (2.7%) | 0.172 | |

| Previous history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack, n (%) | 5 (15.6%) | 16 (8.6%) | 0.215 | |

| Previous history of systemic embolism, n (%) | 1 (3.1%) | 6 (3.2%) | 0.007 | |

| Previous history of heart failure, n (%) | 23 (71.9%) | 157 (84.9%) | 0.32 | |

| Previous history of myocardial infarction, n (%) | 2 (6.2%) | 12 (6.5%) | 0.01 | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 27 (84.4%) | 168 (90.8%) | 0.196 | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 11 (34.4%) | 85 (45.9%) | 0.238 | |

| Renal insufficiency, n (%) | 5 (15.6%) | 13 (7.0%) | 0.274 | |

| Sleep apnoea, n (%) | 13 (40.6%) | 35 (18.9%) | 0.489 | |

| Previous history of electroconversion, n (%) | 21 (65.6%) | 95 (51.4%) | 0.293 | |

| Previous history of pulmonary vein isolation, n (%) | 17 (53.1%) | 91 (49.2%) | 0.079 | |

| 0.477 | ||||

| No device or loop recorder | 25 (78.1%) | 169 (91.4%) | ||

| Pacemaker | 1 (3.1%) | 5 (2.7%) | ||

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator | 3 (9.4%) | 6 (3.2%) | ||

| Cardiac resynchronisation therapy (implantable cardioverter defibrillator) | 3 (9.4%) | 5 (2.7%) | ||

| Antiplatelet drug | 3 (9.4%) | 4 (2.2%) | 0.313 | |

| Aspirin | 4 (12.5%) | 14 (7.6%) | 0.165 | |

| Statin | 16 (50.0%) | 53 (28.6%) | 0.448 | |

| Diuretic | 16 (50.0%) | 55 (29.7%) | 0.423 | |

| Beta-blocker | 25 (78.1%) | 118 (63.8%) | 0.32 | |

| Digoxin | 2 (6.2%) | 3 (1.6%) | 0.24 | |

| Anticoagulant | 31 (96.9%) | 157 (84.9%) | 0.426 | |

| Education, n (%) | 0.324 | |||

| Basic | 2 (6.5%) | 17 (9.2%) | ||

| Middle | 20 (64.5%) | 90 (48.6%) | ||

| Advanced | 9 (29.0%) | 78 (42.2%) | ||

| Smoking, n (%) | 0.112 | |||

| Never | 12 (38.7%) | 75 (40.5%) | ||

| In the past | 13 (41.9%) | 82 (44.3%) | ||

| Active | 6 (19.4%) | 28 (15.1%) | ||

| Alcohol, drinks per day, mean (SD) | 0.53 (0.72) | 0.98 (1.46) | 0.392 | |

| Physical activity, n (%) | 11 (35.5%) | 93 (50.3%) | 0.302 | |

| Civil status, n (%) | 0.169 | |||

| Single | 4 (12.9%) | 29 (15.7%) | ||

| Married | 21 (67.7%) | 127 (68.6%) | ||

| Divorced | 5 (16.1%) | 27 (14.6%) | ||

| Widowed | 1 (3.2%) | 2 (1.1%) | ||

| Children: No, n (%) | 6 (19.4%) | 54 (29.2%) | 0.231 | |

| Greater reagion, n (%) | 0.405 | |||

| Zurich | 8 (25.0%) | 26 (14.3%) | ||

| Lake Geneva | 1 (3.1%) | 9 (4.9%) | ||

| Espace Mittelland | 10 (31.2%) | 46 (25.3%) | ||

| Northwestern Switzerland | 6 (18.8%) | 59 (32.4%) | ||

| Eastern Switzerland | 3 (9.4%) | 21 (11.5%) | ||

| Southern Switzerland | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Central Switzerland | 4 (12.5%) | 21 (11.5%) | ||

CHA₂DS₂-VASc: risk of stroke (for non-valvular atrial fibrillation); IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation.

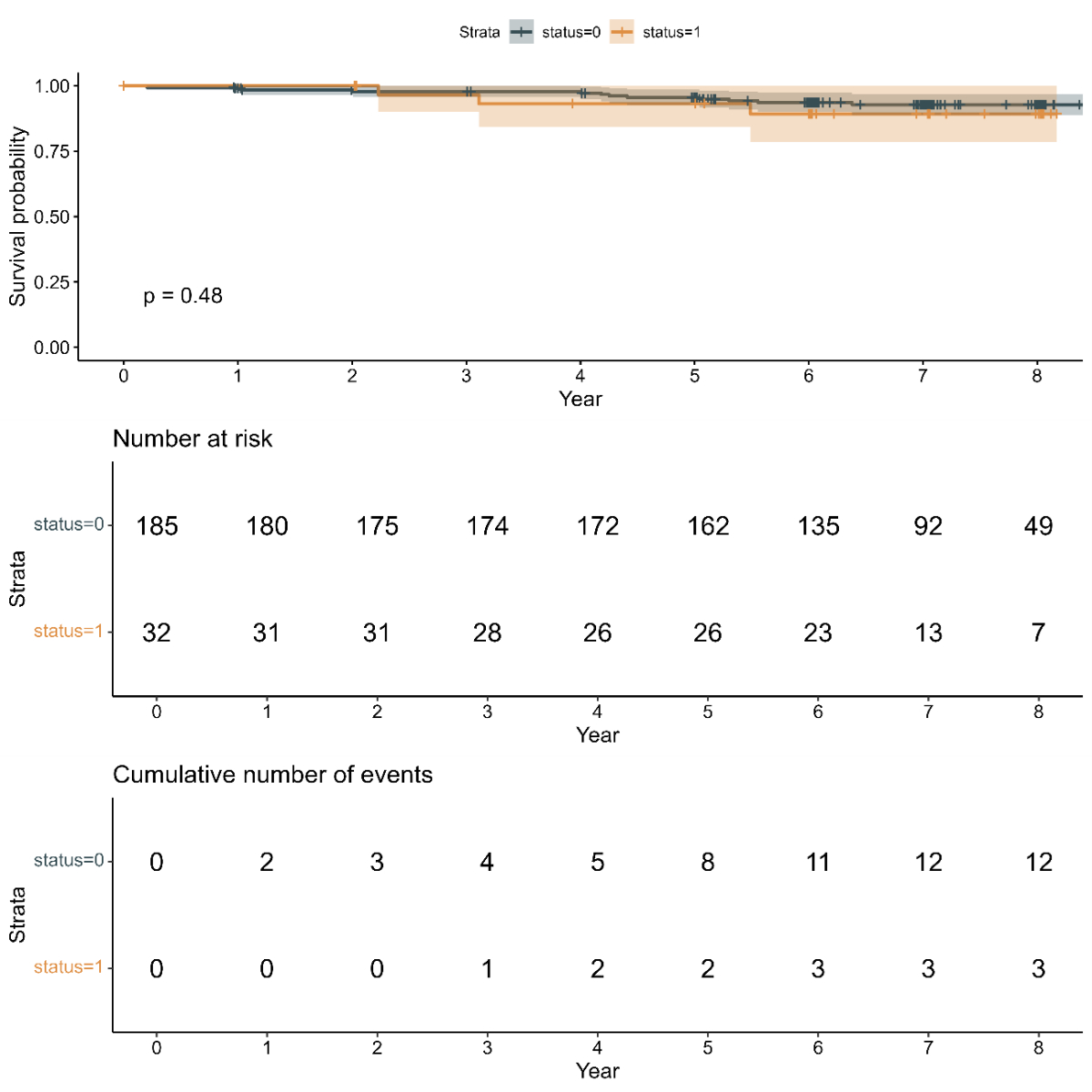

Comparing the survival probability for patients with and without atrial fibrillation-related professional activity change, no difference was observed over the full time period (appendix figure S2).

Of the 157 patients working at baseline, 48 patients reported a total of 696 days lost due to atrial fibrillation across 367 observed patient-years. This resulted in an average of 1.9 days per patient-year.

Table 2 shows the evolution of degree of employment across time, in comparison with the matched general population sample. Overall, slightly fewer Swiss-AF patients were employed (75%) compared to the general population (77%). However, if they were working, the degree of employment was higher (88% vs 83%). The higher degree of employment was present at all visits. The average degree of employment across all visits and including people not working was 65% for Swiss-AF patients and 63% for SLFS participants, with no apparent differences developing during follow-ups.

Table 2Evolution of degree of employment over time, and in comparison with the matched general population. Employment includes self-employed work. Calculation of average degree of employment across full population includes people not working. Follow-up 8 is missing due to the lack of Swiss labour force survey data for 2022 and 2023.

| Over all | Baseline | Follow-up 1 | Follow-up 2 | Follow-up 3 | Follow-up 4 | Follow-up 5 | Follow-up 6 | Follow-up 7 | ||

| Average degree of employment, % (95% CI) across full population | Swiss-AF | 65% (63–68%) | 63% (57–69%) | 62% (56–68%) | 66% (60–73%) | 66% (59–72%) | 65% (58–72%) | 70% (62–78%) | 76% (67–85%) | 65% (39–92%) |

| SLFS | 63% (63–64%) | 64% (63–66%) | 65% (63–66%) | 65% (63–67%) | 65% (63–67%) | 64% (62–66%) | 65% (63–68%) | 65% (62–68%) | 66% (60–73%) | |

| % of people working | Swiss-AF | 75% | 72% | 71% | 75% | 75% | 75% | 80% | 83% | 67% |

| SLFS | 77% | 78% | 78% | 78% | 78% | 78% | 78% | 79% | 81% | |

| Average degree of employment, % (95% CI) of the working population | Swiss-AF | 88% (86–89%) | 87% (83–90%) | 87% (83–91%) | 88% (84–92%) | 87% (82–91%) | 86% (82–91%) | 87% (82–93%) | 92% (88–96%) | 98% (93–103%) |

| SLFS | 83% (82–83%) | 83% (81–84%) | 83% (81–84%) | 82% (81–84%) | 83% (81–84%) | 83 (81–84%) | 84% (82–85%) | 82% (80–84%) | 82% (77–87%) | |

Swiss-AF: Swiss Atrial Fibrillation prospective cohort study (Swiss-AF); SLFS: Swiss labour force survey.

The comparison for baseline visit indicated that among all employed people, the proportion working full-time was higher in the Swiss-AF cohort than in the general population (Swiss-AF: 73% full-time and 27% part-time; general population: 62% full-time and 38% part-time). Sensitivity analyses with different seeds, or including education as a matching variable did not materially alter our findings.

Given the absence of relevant differences between the Swiss-AF patients and the general population, we did not perform the calculation of indirect costs. We found no indication of major indirect costs of atrial fibrillation arising from lost productivity.

Only a minority of Swiss-AF patients reported a negative impact of atrial fibrillation on their professional activity. Professional activity change for other reasons was reported more frequently. There were also no remarkable differences in comparison with the general population, thus no major work-related indirect costs incurred for atrial fibrillation patients.

While atrial fibrillation undoubtedly has an impact on a patient’s life, including work life, the combined effect of other factors on changes in professional activity seems to be more pronounced. Swiss-AF patients were treated as per guidelines and our group has previously shown that the health-related quality of life of the Swiss-AF patients was stable during at least five years of follow-up [2]. This suggested that the burden of atrial fibrillation on patients’ daily life remained relatively constant. We regard this as a consistent finding. When atrial fibrillation patients experience stable quality of life, they are also less likely to be adversely affected in their professional activity, i.e. tend to maintain their professional commitments and productivity. We observed this irrespective of sex, civil status and whether pulmonary vein isolation was performed. These findings suggest that well-treated atrial fibrillation patients can effectively manage their condition without significant professional activity-related setbacks. It underscores the importance of early diagnosis and effective treatment to minimise the impact of atrial fibrillation on an individual’s professional life. Numerical sociodemographic differences (i.e. a lower proportion of patients with advanced education and a higher proportion of patients with children in those with an atrial fibrillation-related professional activity change) might indicate effects but may as well have arisen from chance effects given the small sample size.

Our findings seem to be mainly consistent with the available, scarce literature. In our study, 3.8% of the working patients reported a professional activity change due to atrial fibrillation and 11.6% due to other reasons over the 8-year follow-up period. A study from the UK reported 6% health-related job losses over a 2-year follow-up period and 19% work stops due to other reasons [5]. The numbers are similar, but not directly comparable, since work losses included any health problems and the observation period was much shorter than in our study.

A Swedish study from 2007 reported that roughly 6% of all atrial fibrillation patients below 65 years had a sick leave longer than 14 days [10]. The comparability of this finding with our study is limited, as the Swedish study included only sick leaves longer than 14 days and due to any reason. In our study, we assessed the sum of days lost specifically due to atrial fibrillation, resulting in 1.9 days per patient-year for patients who had reported days lost.

Our comparison of the Swiss-AF patients with the general population indicated strong similarity of professional activity levels. This is principally compatible with the finding of no long-term disability in a retrospective database study of recently diagnosed and on average younger US patients covering the time period 2001–2008 [3]. In a more recent Danish study, atrial fibrillation patients incurred productivity losses worth €1176 due to atrial fibrillation within three years of atrial fibrillation diagnosis [11]. The highest costs were found in the first year (€824), with less impact thereafter (year 2: €191, year 3: €160). Setting these numbers into relation with the average annual full-time adjusted salary per employee in Denmark in 2017 (€58,700) [12], this would amount to 0.3–1.4% of a full-time position. Another study reported annual mean indirect costs for work reduction due to atrial fibrillation of €521 in Sweden and €392 in Germany in 2005 [13]. With an average annual full-time adjusted salary per employee of €32,900 in Sweden and €30,900 in Germany in 2005, this is equivalent to 1.6% and 1.3% of a full-time job respectively. Such a limited impact is not inconsistent with our finding of no relevant differences between Swiss-AF patients and the Swiss general population, all the more as the Danish findings were observed shortly after atrial fibrillation diagnosis.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the impact of atrial fibrillation on productivity in Swiss working-age patients. Due to the health economic data collection nested within the clinical Swiss-AF cohort study, we were able to analyse a wide range of patient and disease characteristics, and productivity parameters. However, as the inclusion of patients below 65 years was limited to a predetermined number of patients (228) by the study protocol, the number of patients for this analysis was rather low. A detailed analysis of influencing factors would have been subject to chance effects and not interpretable. This remains for further research. Additionally, given the focus of recruitment in specialised clinical centres, the results may not be fully generalisable to all working-age atrial fibrillation patients. Nevertheless, the long observation period of eight years enabled us to gather valuable insights into longer-term effects of atrial fibrillation on professional activity changes in working-age patients. Unfortunately, we had no detailed information on why patients had stopped or reduced work for reasons other than atrial fibrillation. We could therefore not distinguish whether or not the reasons may have been related to other health problems. A further limitation lies in the different data structures of the longitudinal Swiss-AF cohort and the SLFS. Given the cross-sectional structure of the SLFS, our analysis options for comparisons were restricted. Moreover, we cannot rule out that the control population included patients with atrial fibrillation. However, given the large number of SLFS participants available for the matching, and given that the prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the working-age population is rather low, it is unlikely that a relevant bias arose from this. Lastly, there was no information on days missed at work for the control population, restricting our comparison to degree of employment. However, longer-term impacts of illnesses tend to impact the professional activity levels and were thus captured.

In conclusion, our study indicates that well-treated atrial fibrillation patients may experience minimal disruptions to professional activity, even over an extended 8-year follow-up period. The comparison with the general population further highlights that the impact of atrial fibrillation on working life may be manageable. These findings underscore the importance of early diagnosis, effective treatment and consistent management to enable individuals with atrial fibrillation to lead productive, satisfying and sustainable work lives despite their medical condition.

The patient informed consent forms state that the data, containing personal and medical information, is exclusively available for research institutions in an anonymised form and is not allowed to be made publicly available. Researchers interested in obtaining the data for research purposes can contact the Swiss-AF scientific lead. Contact information is provided on the Swiss-AF website (http://www.swissaf.ch/contact.htm). Authorisation by the corresponding ethics committee is mandatory before the requested data can be transferred to external research institutions.

Swiss-AF investigators

University Hospital Basel and Basel University: Stefanie Aeschbacher, Steffen Blum, Leo H. Bonati, Désirée Carmine, David Conen, Urs Fischer, Corinne Girroy, Elisa Hennings, Philipp Krisai, Michael Kühne, Christine Meyer-Zürn, Pascal B. Meyre, Andreas U. Monsch, Christian Müller, Stefan Osswald, Rebecca E. Paladini, Raffaele Peter, Adrian Schweigler, Christian Sticherling, Gian Völlmin. Principal Investigator: Stefan Osswald; Local Principal Investigator: Michael Kühne.

University Hospital Bern: Faculty: Drahomir Aujesky, Juerg Fuhrer, Laurent Roten, Simon Jung, Heinrich Mattle; Research fellows: Seraina Netzer, Luise Adam, Carole Elodie Aubert, Martin Feller, Axel Loewe, Elisavet Moutzouri, Claudio Schneider; Study nurses: Tanja Flückiger, Cindy Groen, Lukas Ehrsam, Sven Hellrigl, Alexandra Nuoffer, Damiana Rakovic, Nathalie Schwab, Rylana Wenger, Tu Hanh Zarrabi Saffari. Local Principal Investigators: Nicolas Rodondi, Tobias Reichlin.

Stadtspital Triemli Zurich: Roger Dillier, Michèle Deubelbeiss, Franz Eberli, Christine Franzini, Isabel Juchli, Claudia Liedtke, Samira Murugiah, Jacqueline Nadler, Thayze Obst, Jasmin Roth, Fiona Schlomowitsch, Xiaoye Schneider, Peter Sporns, Katrin Studerus, Noreen Tynan, Dominik Weishaupt. Local Principal Investigator: Andreas Müller.

Kantonspital Baden: Corinne Friedli, Silke Kuest, Karin Scheuch, Denise Hischier, Nicole Bonetti, Alexandra Grau, Jonas Villinger, Eva Laube, Philipp Baumgartner, Mark Filipovic, Marcel Frick, Giulia Montrasio, Stefanie Leuenberger, Franziska Rutz. Local Principal Investigator: Jürg-Hans Beer.

Cardiocentro Lugano: Angelo Auricchio, Adriana Anesini, Cristina Camporini, Maria Luce Caputo, Rebecca Peronaci, Francois Regoli, Martina Ronchi. Local Principal Investigator: Giulio Conte.

Kantonsspital St. Gallen: Roman Brenner, David Altmann, Karin Fink, Michaela Gemperle. Local Principal Investigator: Peter Ammann.

Hôpital Cantonal Fribourg: Mathieu Firmann, Sandrine Foucras, Martine Rime. Local Principal Investigator: Michael Kühne.

Luzerner Kantonsspital: Benjamin Berte, Kathrin Bühler, Virgina Justi, Frauke Kellner-Weldon, Richard Kobza, Melanie Koch, Brigitta Mehmann, Sonja Meier, Myriam Roth, Andrea Ruckli-Kaeppeli, Ian Russi, Kai Schmidt, Mabelle Young. Local Principal Investigator: Michael Kühne.

Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale Lugano: Elia Rigamonti, Carlo Cereda, Alessandro Cianfoni, Maria Luisa De Perna, Jane Frangi-Kultalahti, Patrizia Assunta Mayer Melchiorre, Anica Pin, Tatiana Terrot, Luisa Vicari. Local Principal Investigator: Giorgio Moschovitis.

University Hospital Geneva: Georg Ehret, Hervé Gallet, Elise Guillermet, Francois Lazeyras, Karl-Olof Lovblad, Patrick Perret, Philippe Tavel, Cheryl Teres. Local Principal Investigator: Dipen Shah.

University Hospital Lausanne: Nathalie Lauriers, Marie Méan, Alessandra Pia Porretta, Sandrine Salzmann, Jürg Schläpfer. Local Principal Investigator: Michael Kühne.

Bürgerspital Solothurn: Andrea Grêt, Jan Novak, Sandra Vitelli. Local Principal Investigator: Frank-Peter Stephan.

Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale Bellinzona: Jane Frangi-Kultalahti, Augusto Gallino, Luisa Vicari. Local Principal Investigator: Marcello Di Valentino.

University of Zurich/University Hospital Zurich: Helena Aebersold, Fabienne Foster, Matthias Schwenkglenks.

Medical Image Analysis Center AG Basel: Marco Düring, Tim Sinnecker, Anna Altermatt, Michael Amann, Petra Huber, Manuel Hürbin, Esther Ruberte, Alain Thöni, Jens Würfel, Vanessa Zuber.

Clinical Trial Unit Basel: Michael Coslovsky (Head), Pia Neuschwander, Patrick Simon, Olivia Wunderlin.

Schiller AG Baar: Ramun Schmid, Christian Baumann.

This work is supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant numbers 105318_189195 / 1, 33CS30_148474, 33CS30_177520, 32473B_176178 and 32003B_197524), the Swiss Heart Foundation, the Foundation for Cardiovascular Research Basel (FCVR) and the University of Basel.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. Dr Aeschbacher received a speaking fee from Roche Diagnostics. Dr Auricchio is a consultant with Abbott, Boston Scientific, Backbeat, Cairdac, Corvia, EP Solutions, Medtronic, Microport CRM, Philips, XSpline; he participates in clinical trials sponsored by Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Microport CRM, Philips and XSpline; and has intellectual properties assigned to Boston Scientific, Biosense Webster and Microport CRM. Dr Beer reports grant support from the Swiss National Foundation of Science, The Swiss Heart Foundation and Stiftung Kardio; grant support, speaking and consultation fees to the institution from Bayer, Sanofi and Daichii Sankyo. Dr Bonati reports personal fees and nonfinancial support from Amgen, grants from AstraZeneca, personal fees and nonfinancial support from Bayer, personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, personal fees from Claret Medical, grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, grants from the University of Basel, grants from the Swiss Heart Foundation, outside the submitted work. Dr Conen received consulting fees from Roche Diagnostics and Trimedics, and speaking fees from Servier, all outside of the current work. Dr Kühne reports personal fees from Bayer, personal fees from Böhringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Pfizer BMS, personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, personal fees from Medtronic, personal fees from Biotronik, personal fees from Boston Scientific, personal fees from Johnson&Johnson, personal fees from Roche, grants from Bayer, grants from Pfizer, grants from Boston Scientific, grants from BMS, grants from Biotronik, grants from Daiichi Sankyo. Dr Giorgio Moschovitis has received advisory board or speaking fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Gebro Pharma, Novartis and Vifor, all outside of the submitted work. Dr Osswald received research grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation and from the Swiss Heart Foundation, research grants from the Foundation for CardioVascular Research Basel, research grants from Roche, educational and speaker office grants from Roche, Bayer, Novartis, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo and Pfizer. Dr Reichlin has received research grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Swiss Heart Foundation and the sitem insel support fund, all for work outside the submitted study; speaking/consulting honoraria or travel support from Abbott/SJM, AstraZeneca, Brahms, Bayer, Biosense-Webster, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Daiichi Sankyo, Medtronic, Pfizer-BMS and Roche, all for work outside the submitted study; support for his institution’s fellowship programme from Abbott/SJM, Biosense-Webster, Biotronik, Boston Scientific and Medtronic for work outside the submitted study. Dr Schwenkglenks reports grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, for the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from Amgen, grants from MSD, grants from Novartis, grants from Pfizer, grants from The Medicines Company, all outside the submitted work. Dr Serra-Burriel reports grants from the European Commission outside of the present work. Dr Sticherling has received speaker honoraria from Biosense Webster and Medtronic and research grants from Biosense Webster, Daiichi-Sankyo and Medtronic.

1. Morillo CA, Banerjee A, Perel P, Wood D, Jouven X. Atrial fibrillation: the current epidemic. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017 Mar;14(3):195–203.

2. Foster-Witassek F, Aebersold H, Aeschbacher S, Ammann P, Beer JH, Blozik E, et al.; Swiss‐AF Investigators. Longitudinal Changes in Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023 Nov;12(21):e031872. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.123.031872

3. Rohrbacker NJ, Kleinman NL, White SA, March JL, Reynolds MR. The burden of atrial fibrillation and other cardiac arrhythmias in an employed population: associated costs, absences, and objective productivity loss. J Occup Environ Med. 2010 Apr;52(4):383–91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181d967bc

4. Bernt Jørgensen SM, Gerds TA, Johnsen NF, Gislason G, El-Chouli M, Brøndum S, et al. Diagnostic group differences in return to work and subsequent detachment from employment following cardiovascular disease: a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2023 Jan;30(2):182–90. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwac249

5. Walker-Bone K, D’Angelo S, Linaker CH, Stevens MJ, Ntani G, Cooper C, et al. Morbidities among older workers and work exit: the HEAF cohort. Occup Med (Lond). 2022 Oct;72(7):470–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqac068

6. Leijten FR, van den Heuvel SG, Ybema JF, van der Beek AJ, Robroek SJ, Burdorf A. The influence of chronic health problems on work ability and productivity at work: a longitudinal study among older employees. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2014 Sep;40(5):473–82. doi: https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3444

7. Conen D, Rodondi N, Mueller A, Beer J, Auricchio A, Ammann P, et al. Design of the Swiss Atrial Fibrillation Cohort Study (Swiss-AF): structural brain damage and cognitive decline among patients with atrial fibrillation. Swiss Med Wkly. 2017 Jul;147(2728):w14467.

8. Swiss Labour Force Survey | Fact sheet | Federal Statistical Office. Accessed October 17, 2023. Available from: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/work-income/surveys/slfs.assetdetail.20565829.html

9. Swiss Labour Force Survey (SLFS) | Federal Statistical Office. Accessed October 17, 2023. Available from: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/work-income/surveys/slfs.html

10. Ericson L, Bergfeldt L, Björholt I. Atrial fibrillation: the cost of illness in Sweden. Eur J Health Econ. 2011 Oct;12(5):479–87. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-010-0261-3

11. Johnsen SP, Dalby LW, Täckström T, Olsen J, Fraschke A. Cost of illness of atrial fibrillation: a nationwide study of societal impact. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017 Nov;17(1):714. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2652-y

12. Statistics | Eurostat. Accessed October 26, 2023. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/NAMA_10_FTE__custom_8126687/default/table?lang=en

13. Jönsson L, Eliasson A, Kindblom J, Almgren O, Edvardsson N. Cost of illness and drivers of cost in atrial fibrillation in Sweden and Germany. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2010;8(5):317–25. doi: https://doi.org/10.2165/11319880-000000000-00000

Figure S1Time to first atrial fibrillation (AF)-related professional activity change: (A) time since atrial fibrillation diagnosis and (B) time before retirement. In (A) there is a slight decrease over time, meaning that patients were more likely to report an impact of atrial fibrillation on their professional activity the longer they had had atrial fibrillation. When looking at years until retirement, a steeper decrease is seen within 6 years before retirement. Patients were thus more likely to report a professional activity change due to atrial fibrillation in the years close to their retirement.

Figure S2Kaplan-Meier curve of survival for patients with and without atrial fibrillation-related professional activity change.