Figure 1Different methodological steps in analyzing cantonal OAT authorisation implementation.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.3629

Opioid agonist treatment (OAT) is the gold standard for treating opioid use disorders in Switzerland and abroad [1–4]. Long-acting opioid agonists, such as methadone, levomethadone, buprenorphine, and slow-release morphine, create a state of protective tolerance, allowing the person in OAT to reduce heroin use or stop taking it altogether while initiating and maintaining further medical or psychosocial care [5].

Historically, Switzerland, most European countries, Canada, the United States, Australia, and others, have had regulatory requirements for OAT that are stricter than those applicable to treatment with other pharmaceutical products, including controlled medicines [6, 7]. Internationally, the requirements are diverse; they range from national registries for persons in OAT to national waivers authorizing physicians to prescribe OAT medications [6–8].

A 2017 Council of Europe report established guiding principles on legislation and regulation and emphasized countries’ duties to ensure a coherent OAT framework [8]. However, the academic literature shows that international regulations have not been implemented uniformly and that the national laws and clinical practices are disparate [9–11]. Thus, coherence is not ensured. Studies have shown that policies can create administrative barriers, thereby affecting OAT availability and access [7, 12].

Switzerland has long been heralded as a pioneer for its drug policy (in particular, the “four-pillar policy” of prevention, therapy, harm reduction, and sanctions); it is often described as a model for other countries. However, Switzerland is a federalist country in which authority is shared among the Federal government, 26 cantons (a canton is equivalent to a state in the United States), and approximately 2000 communes (see figure S1 in the appendix). The Swiss Narcotics Act (NarcA) requires the cantons to execute certain tasks [13]. As such, laws, ordinances, and guidelines regarding OAT at the cantonal level detail the responsibilities and relevant procedures.

In 1975, the Federal NarcA had already required cantonal authorisation to treat opioid use disorders (Art. 15a NarcA, in force since 1 Aug. 1975). More precisely, a licence issued by the canton was required to prescribe, dispense, and administer narcotics intended to treat persons dependent on narcotics [14]. In 2011, the OAT authorisation requirement was specified further in an ordinance [15].

In 2020, Switzerland counted over 16,000 persons receiving OAT with a cantonal authorisation [16]. The number of people in Swiss OAT has remained mostly stable for 20 years, with a slight decrease since 2018 [16]. Around 60% of OAT treatments are administered by general practitioners [17]. Approximately two-thirds of people in Swiss OAT receive methadone (59.8%), less than one-third receive slow-release morphine (27.5%), and only a minority receive buprenorphine (8.5%), levomethadone (3.0%) or other molecules (1.2%) [18].

Treatment with diamorphine prescription (pharmaceutical heroin) is subject to specific regulatory requirements. It is subject to restricted control and requires a federal authorisation from the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH). In 2019, the programme serviced 1400 people [19]. In this publication, we exclude these authorisations because they are federal authorisations following (mostly) uniform rules.

Our study is exploratory and aims to investigate the various cantonal provisions deriving from NarcA regarding OAT. For cantonal OAT authorisations, we focused on the authorisation type, the renewal, the procedure and collected data, third-party involvement, and the requirements imposed on treating physicians. Our primary objective was to determine how these legal requirements are, on the one hand, implemented and, on the other hand, perceived in each canton. This includes a collection of implemented solutions, their results, and challenges. We hypothesised that we would see a heterogeneous implementation, as the systems have developed independently from each other for decades; moreover, there is little pressure to harmonise among cantons. Based on our interview results, we highlighted the differences between the current practices and collected suggestions for improving CM legislation (our secondary objective).

To our knowledge, our research is the first attempt to describe the implementation of the cantonal OAT requirement. The vast divergence among implementation strategies makes Switzerland the perfect microcosm for analyzing OAT regulation. Our critical review and recommendations reveal the need to evaluate different approaches to improve OAT regulation and implementation.

Our research project started with an extensive literature review, which had already been published in an article on the pilot phase [20] and in another article analyzing cantonal legislation [21]. This paper presents the entirety of our empirical results regarding OAT authorisations.

Our data collection method was based on a two-step approach [20]. We conducted an extensive cantonal legal and document analysis to prepare for our interviews, which were held with cantonal physicians and cantonal pharmacists. This enabled us to optimise our time in the interviews, which we conducted to verify whether the OAT guidelines and documents published online had been applied and to complete any missing data.

The interviews covered tasks implemented by the cantons according to NarcA. In this publication, we present only the results regarding cantonal OAT authorisations. As mentioned above, we excluded federally regulated treatments with diamorphine prescription.

Figure 1Different methodological steps in analyzing cantonal OAT authorisation implementation.

From 2020 to 2021, CAB and CSK collected the relevant cantonal legal texts using the internet platform http://www.lexfind.ch (keyword search: “Betäubungsmittel” and “Sucht”). Only texts on laws and guidelines in force when we conducted the analysis were included. We identified the applicable cantonal articles and regulations, highlighting inconsistencies between federal law and cantonal specificifications.

CAB and CSK completed the document analysis by searching for forms and guidelines on the cantonal health officials’ websites. We looked specifically for cantonal OAT guidelines and “OAT contracts”.

CAB and CSK discussed the findings for each canton. We summarised the findings in a database, thus facilitating a comparison across cantons. This enabled us to establish canton-specific questions, including about a lack of existing guidelines, to ask during the interviews.

If we could not find specific information in advance, during the interviews, we verified that there was indeed a dearth of available documentation.

We chose to interview the cantonal physicians and cantonal pharmacists (i.e., inclusion criteria). They are the cantonal officials who are generally responsible for administering the tasks designated by NarcA (specifically articles 3e, 11 1bis, and 16–18 NarcA). As such, they are at the forefront of implementing federal and cantonal legislation. Additionally, cantonal physicians and cantonal pharmacists shape implementation through their oversight and advisory roles.

Cantonal physicians and cantonal pharmacists can also nominate deputies to participate in their stead.

We did not include officials responsible solely for narcotics regulation in veterinary use.

The interview guide (see supplementary materials in appendix) was adapted differently for each canton based on the document and legal text analysis described above. The topics detailed in the interview guide were gradually refined and simplified in a pilot study conducted in four cantons (Vaud, Geneva, Fribourg, and Valais). In 2021, we published the process through which we refined our interview guide in this pilot phase [20].

The interview guide is comprised of three sections: (1) warm-up questions pertaining primarily to the participants’ background, (2) questions regarding implementing the different legal provisions, and (3) personal (i.e., subjective) opinions expressed by the cantonal physicians and cantonal pharmacists on their roles as dictated by NarcA.

Table 1Interview guide module OAT with follow-up questions, which were asked only when applicable.

| Topic | Subtopics |

| OAT authorisation request | Using substitution–online tool or cantonal form |

| Patient data required | |

| Duration/renewal of authorisation granted | |

| Training requirements for physicians or pharmacists | |

| OAT treatment guidelines and recommendations | Treatment of underaged (<18 years) persons |

| Substance restrictions | |

| Co-medications (e.g. Benzodiazepines, Ritalin): authorisation, reporting requirements or restrictions | |

| Urine tests | |

| OAT dispensing guidelines and recommendations | Visual control of the person taking OAT required |

| Methadone formulation restrictions | |

| Recommendation regarding added syrup | |

| Possible dispensation sites | |

| Acceptance of persons in OAT by dispensing pharmacies | |

| Cooperating with other cantons | Double treatments |

| Exchanging experiences | |

Participants were recruited by contacting the cantonal offices of the cantonal physicians and cantonal pharmacists. The invitation was sent via e-mail and included the project letter with additional information and a link to the project website. If no response was received, the offices were contacted by phone. Participants were not asked to prepare for the interview to ensure similar conditions for all.

Upon confirming the interview’s date and time, participants were informed about the interview’s general themes and structure. We explained that the questions are “official” in the first part of the interview and that the coded personal data (but not their statements) would be linked to the canton. In addition, participants were sent a consent form at the latest one day before the interview so they could review it beforehand.

The participants were interviewed one-on-one in semi-structured interviews, ranging in duration from 1 to 1.5 hours. The interviews were conducted in either French or German, depending on the individual participant’s preference. Depending on COVID-19 restrictions and participant preferences, interviews were administered in person, via Zoom, or over the telephone.

If a participant explicitly agreed, the interview was audio-recorded so a transcript could be generated for the qualitative data analysis. To ensure that all interviews were conducted in the same environment and to safeguard confidentiality, they were carried out separately for the cantonal physicians and cantonal pharmacists.

If, after the interview, data were missing, we called or e-mailed to obtain follow-up answers.

More details regarding the interview procedure and data processing can be found in the supplementary materials (see appendix).

CSK and SB coded and analysed the interview transcripts using an analytical framework approach with content analysis using MaxQDA [22–25]. We decided on an essentially deductive approach, namely because our research seeks to describe differences and similarities among cantons. Furthermore, our analysis only presents participants’ actual words (manifest analysis). We used a preliminary matrix based on insights from the legal analysis, which preceded interviews and structural codes. We chose an unrestrained categorisation matrix to allow for the creation of subcodes with inductive content analysis when necessary [26]. In practice, the interviews were coded first with main codes, that is, structural codes corresponding to questions in the interview guide, e.g., “OAT authorisation type”. The main code text was categorised, e.g., subcode “OAT authorisation specific to a person in treatment”. If no suitable code existed, creating a new code with inductive content analysis was considered, e.g., subcode “Involvement of addiction counsellor”.

The interviewed cantonal officials were informed about the research’s aim and to what extent the resulting data will be made available. Informed consent was obtained from all the study’s subjects involved. Participants could request a copy of the written transcript of their interview. Finally, this article’s draft was sent to every interviewed participant for review.

We do not believe there are sensitive ethical issues in interviewing cantonal officials regarding their professional activities. However, during the interviews, participants were asked for their opinions, and some explained their stance regarding addiction politics or critiqued authorities. Therefore, the data are not publicly available; this is to maintain strict anonymity of the participants. Moreover, it is impossible to fully anonymise the data; based on the complete dataset, it is comparatively easy to infer participants’ identities (e.g., large canton vs small canton). However, the data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. A re-identification waiver will be required to access the interview transcripts.

The research protocol was approved by the University of Lausanne Research Ethics Commission (Commission d’Ethique de la Recherche de l’Université de Lausanne; Project number: E_FBM_022021_00001).

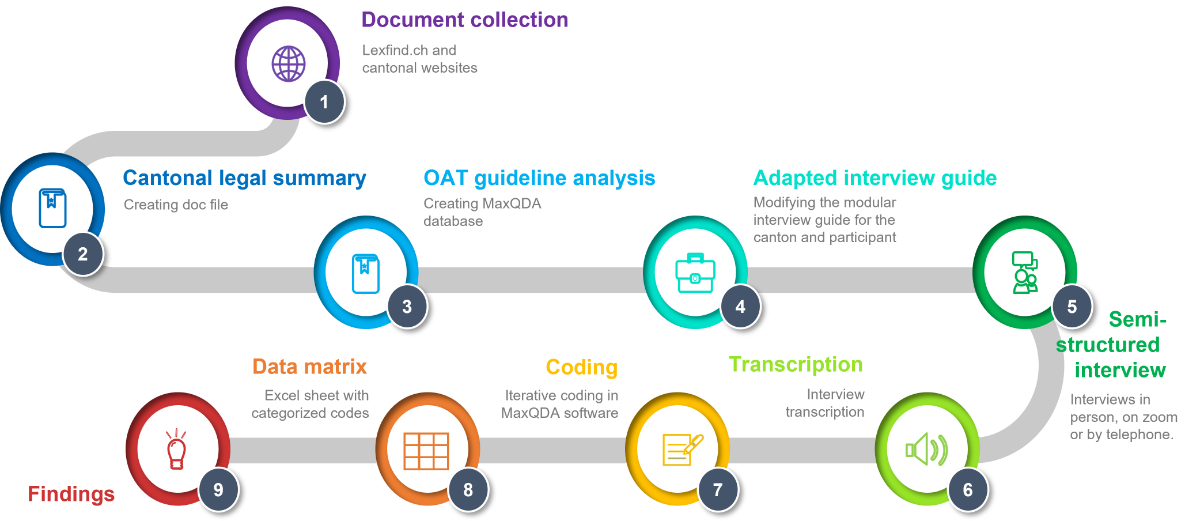

In total, we reviewed 263 cantonal legal texts that contained our word searches. However, our areas of interest were generally covered within a single cantonal law or ordinance. We collected and compared 21 OAT guidelines (see figure 2A and table S1 in the appendix). They differed in structure, depth, and topic. For example, one OAT guideline might detail rules applicable when patients go on holiday, whereas another might not mention holidays at all. Furthermore, during the interviews, we learned that 2 (10%) guidelines were outdated and 5 (24%) were about to be updated. Hence, a sole textual analysis of these guidelines cannot be conclusive.

We will now present the interview results which reflect actual OAT implementation at the cantonal level.

Figure 2Implementation variation of cantonal opioid agonist treatment (OAT) authorisations. A: OAT guideline availability and status; B: Period after which the cantonal OAT authorisation must be renewed; C: Training requirements general practitioners prescribing OAT must fulfil.

We contacted all cantonal physicians and cantonal pharmacists (27 for OAT). The cantonal physician of Appenzell-Innerrhoden did not respond to our e-mails or calls (5 attempts in total). Appenzell-Innerrhoden is a small canton with only one cantonal physician and no cantonal pharmacist; additionally, it reports only two people in OAT, so we excluded the canton from our analysis.

We conducted 26 interviews regarding OAT with the overseeing cantonal officials (24 cantonal physicians and 2 cantonal pharmacists) between July 2020 and July 2022. Of the 26 participants, 13 (50%) were female. Eight (31%) were deputy cantonal physicians. The range of experience in their current position varied from 4 months (lowest) to 23 years (highest). Three participants (12%) had less than one year of experience as a cantonal physician, and 7 (27%) had between 1 and 3 years of experience (mainly COVID-19 pandemic years).

Cantonal physicians (or their deputies) grant cantonal OAT authorisations in all cantons except Thurgau and Valais, where the cantonal pharmacists perform this function. Graubünden's cantonal physician is also responsible for Glarus.

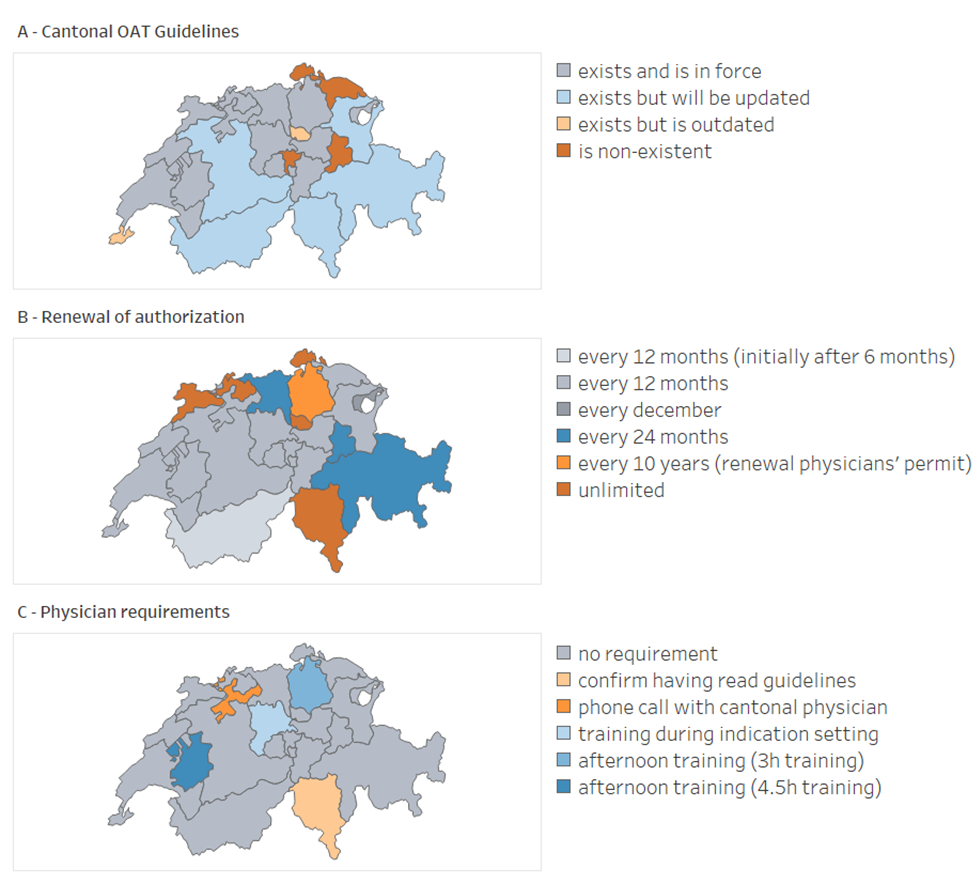

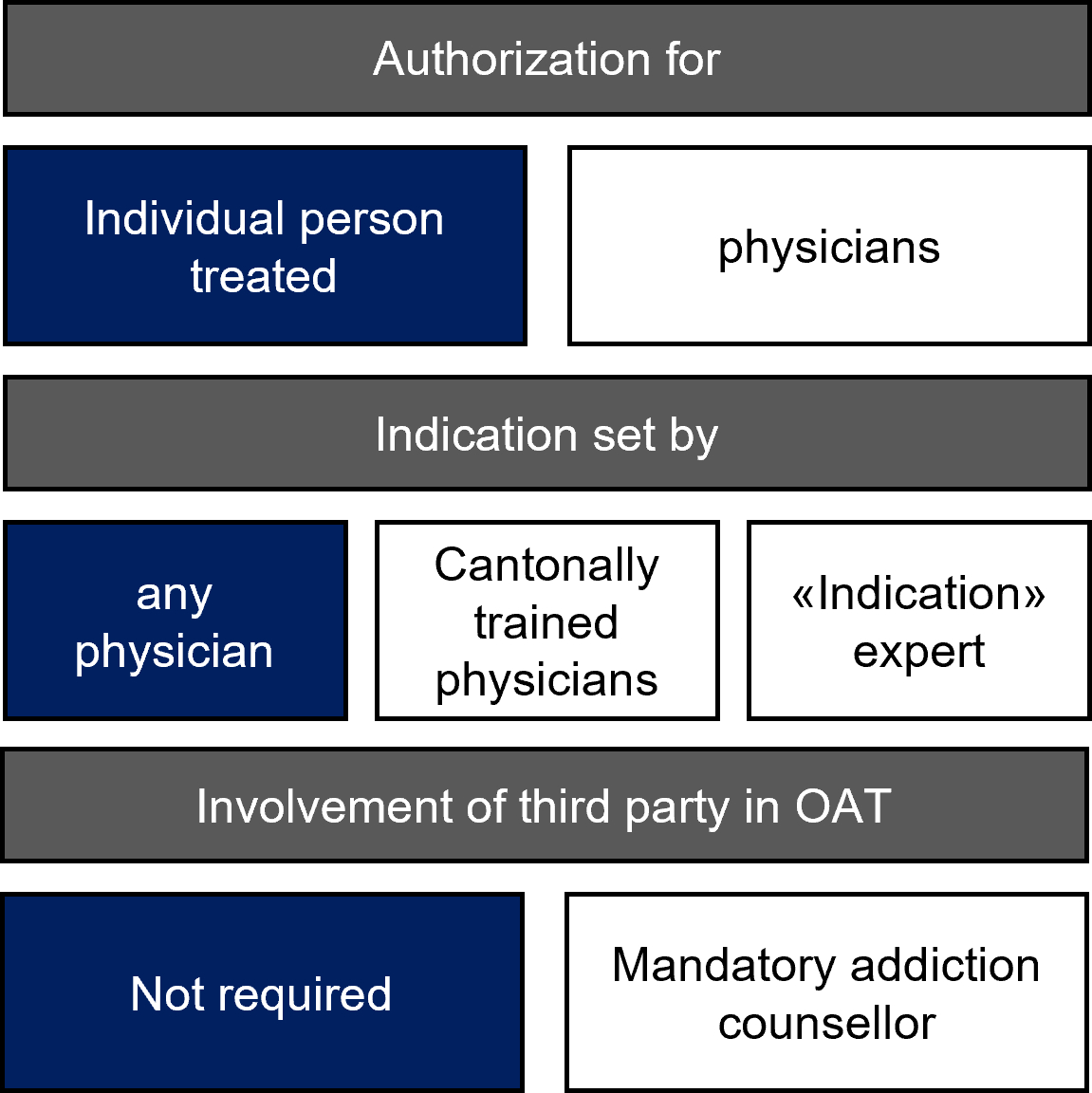

In the majority of cantons (21/25; 84%), OAT authorisation is specific to the person being treated (figure 3, table S1). This means that cantonal authorisation is given to a physician for an individual person in treatment. The authorisation can be requested by any physician with a professional licence (a permit for the independent practice of medicine) in that canton. In practice, it is mainly general practitioners that offer OAT in the ambulatory sector [17].

However, Ticino, Zürich, and Zug give a general OAT authorisation to the physician without any specific reference to a person in treatment (table S1). In Zürich, to be granted a general OAT licence, the physician must already have his or her professional licence and have already attended an introductory OAT course. In Zug, a physician will be granted an OAT licence based on her further or advanced training, which she would have had to disclose when applying for her professional licence. In Ticino, the physician must confirm that he or she has read and will comply with OAT guidelines and regulations and that he or she will provide the required data. In the next step, the OAT-licenced physician in these cantons discloses the treated persons’ identities only to the cantonal physician.

Fribourg has a double authorisation system. In addition to having a first, general OAT licence, the licenced physician must request an additional authorisation for each person in OAT from the cantonal physicians.

Figure 3A graphic representation of differences in authorisation systems of opioid agonist treatments (OAT). Dark blue: most cantons; white: the alternatives.

Federal legislation does not specify if the cantonal authorisation is for only a limited time. Nevertheless, most cantons with OAT authorisations specific to treated persons issue them for one year (15/22; 68%; figure 2B, table S1). Two cantonal physicians issue OAT authorisations for two years (Aargau, Graubünden, Glarus; 3/22; 14%). Four cantons (Basel-Land, Basel-Stadt, Jura, Schaffhausen) issue unlimited authorisations (4/22; 18%). Similarly, in the three cantons that offer general authorisation (Ticino, Zug, Zürich), for the physician, the notification of persons in treatment is valid without a time limit or as long as the physician's professional licence is valid. However, a yearly follow-up occurs for statistical data. Some cantonal health officials have implemented systematic reminders for physicians to renew their licences, or they use a web platform to send reminders. In contrast, Appenzell Ausserrhoden bundles the process by requiring renewal annually in December for the following calendar year.

When there are treatment modifications, such as switching to another substance, the administering physician is generally required to request a new authorisation, despite federal law not requiring this.

Since its development in 2014, an increasing number of cantons has joined the web-based “substitution-online.ch” platform to manage OAT authorisations [16]. This web-based application allows physicians to request OAT autorisations and cantonal health officials to grant and manage these authorisations. Moreover, pharmacists see the names of the person in OAT to whom they are dispensing. The platform issues – in theory – an alarm if there is double treatment; it also stores data used to publish yearly statistics.

As of 2022, 21 of the 26 cantons (81%) had switched to this platform, but some still receive and manage OAT authorisations by means of paper, PDF forms (Basel-Land, Basel-Stadt, Zug, Zürich), or an earlier software (Luzern) [16].

The federal narcotics addiction ordinance specifies that to grant an OAT authorisation, the cantonal authority must receive the name, sex, and address of the person seeking OAT, as well as the treating physician’s address [27]. However, all cantons collect much more data than required (e.g. socio-economic and health data), and cantonal physicians and cantonal pharmacists often report that they specifically check the requested medicine molecule and dosage [28].

The substitution.ch platform offers cantons a choice among three types of questionnaires, each varying in length. The majority have chosen the short questionnaire (19/26; 73%). Nevertheless, three decided on the long questionnaire (Aargau, Fribourg, Nidwalden), and two opted for the medium-length version (Graubünden, Glarus). Vaud has its own questionnaire on the platform. The other cantonal forms are either versions adapted from the short questionnaire or, if still using paper, they are even shorter.

Third-party involvement

In Valais, Uri, Nidwalden, Obwalden, and Schwyz (5/25; 20%), an “addiction counsellor” must be involved in every OAT treatment (table S1). These counsellors are state workers whose tasks are similar to those of social workers. However, they perform a moderating function between the person in treatment and his or her physician; they also issue a yearly report. They are generally the ones who enter data into the above-mentioned web-based platform. In Valais, addiction counsellors are part of a private foundation mandated by the canton to provide continued social support for persons with any addiction, including opioid use disorders. They are heavily involved in the person’s treatment and even sign a document listing patient, physician, pharmacist and counsellor duties regarding OAT called “multipartite OAT contract” [29].

Federal ordinance states that only qualified persons can provide OAT [30], but it is unclear what exactly this means for physicians.

Many cantons require training for physicians who want to prescribe OAT (figure 2C, table S1).

In Zürich, only physicians who have received their cantonal professional licence and attended the introduction training stipulated by the cantonal physician can request the OAT licence. There is no follow-up training. In Fribourg, the cantonal physician requires attending his introduction to OAT training and then a regular follow-up training every two years. In Ticino, a physician applying for general OAT authorisation must confirm having read the cantonal OAT laws and guidelines and may be required to have a phone call with the cantonal physician. Physicians offering OAT must participate in an afternoon course by Ticino’s cantonal physician annually. In Solothurn, only a phone call with the cantonal physician is required.

Five cantonal OAT guidelines (Bern, Basel-Stadt, Jura, Obwalden, Uri) mention that granting an OAT authorisation can be linked to proof of further training (5/21; 24%). Seven (Bern, Basel-Stadt, Jura, Neuchâtel, Obwalden, Sankt Gallen, Uri) expect that physicians offering OAT are interested in this area and regularly attend trainings on the topic (7/21; 33%). However, based on our interviews, neither requirement is actively applied or enforced.

In the majority of cantons, any physician with a valid professional licence can set the indication and decide on the treatment (21/25; 84%). In the context of OAT, this means choosing the molecule, dose, location, and frequency of dispensation.

However, in Schwyz, Basel-Stadt, and Basel-Land, setting the indication for OAT is limited to indication centres (table S1). Hence, a general practitioner diagnosing an opioid use disorder must send the person to the indication centre. This centre is a specialised unit, usually the cantonal hospital’s addiction service. At the indication centre, physicians determine the treatment and decide on all its aspects. In this system, the indication centre requests an OAT authorisation for each individual seeking OAT. After the indication setting, the patient can remain in treatment at the centre or can receive the indicated treatment from his or her general practitioner. In essence, in this system, every person in OAT must be seen by an addiction specialist.

Luzern created a variation of the above described indication centre system. In this canton, a general practitioner can only set an OAT indication under the centre’s supervision. Once a physician has completed three supervised indication settings (deciding substance, dose, etc.), he or she no longer requires supervision, as the physician is deemed “trained and approved”. Such physicians are called “indication physicians”, and the centre maintains a register of them. The authorisation requirement for each patient remains for both the centre and the indication physicians’.

We identified the following issues that cantonal physicians and cantonal pharmacists are facing regarding OAT:

Several (7 out of 11) cantonal physicians and cantonal pharmacists expressed the desire for physicians to be better trained in OAT and addiction in general, while ceding that not every physician is suited for offering OAT, or even wants to. At the same time, nor do they wish to require too much from physicians so as not to discourage those offering OAT.

Some (9 out of 16) cantonal physicians also mentioned difficulties finding young general practitioners willing to offer OAT because persons in OAT might not be the “easiest” patients. The problem might worsen as the older generation of physicians offering OAT retires. However, other cantons reported that they do not face this problem.

When asked, most cantonal physicians and pharmacists (23 out of 23) reported that OAT access is easy in their canton, with no perceivable cantonal differences in their answers. Nevertheless, cantonal physicians and cantonal pharmacists admitted having no indicators to assess ease of access. Independently, we could not find published data on this issue in Switzerland.

Except for one, all cantons not yet using the substitution-online platform expressed interest in using it in the future, hoping that it would reduce the administrative workload, improve the follow-up of persons in OAT, and provide them with a more comprehensive picture of the cantonal situation overall. They were nonetheless wary of the changes and work entailed in such a switch.

None said they would invest more resources, should they get them, into OAT. They stated that they had other responsibilities requiring resources first.

Cantonal physicians seem to accept authorizing OAT as a task that is naturally theirs. One cantonal physician questioned, without being prompted, the authorisation system in its entirety.

In general, we learnt that there is little exchange among cantonal officials regarding OAT. Moreover, when there were any such exchanges, then it would be mainly person-specific (i.e., because the person in OAT, the physician, or the dispensation site are in different cantons). Furthermore, there is little to no interest in harmonizing OAT cantonal practices. Some cantonal physicians and cantonal pharmacists explained that the current systems are too divergent to be harmonised, while others stated that they are only the law’s executors, not legislators.

OAT authorisations should be straightforward, based on the NarcA. However, our study shows that there are significant divergences among cantons. We find that the authorisations are mainly specific to the person in OAT (21/25), are granted by the cantonal physicians (23/25), and require renewal every 12 months (15/25). Furthermore, most cantons use the web-application https://www.substitution-online.ch to manage OAT authorisations (21/26) and allow OAT indication to be done by any physician with a professional licence (21/25).

Apart from vague statements regarding the need to prevent for medicine diversion, there are no explanations why cantons chose different systems. Furthermore, we could not detect any patterns; it could not be explained by different linguistic regions or a canton’s rural or urban geography.

These divergences are important as they could directly affect persons in OAT, an already vulnerable demographic. Furthermore, the differences could adversely affect cantonal health officials’ workload, bearing in mind that they already have many other demanding duties.

Cantonal divergences multiply the workload. Specifically, it consumes cantonal officials’ time and resources to issue and update OAT guidelines. Furthermore, difficulties emerge, and clarifications must be made whenever the physician, the person treated, or the dispensation site are not in the same canton. Overall, whether these differences are still desirable or appropriate should be questioned. Indeed, OAT has become an established gold standard therapy, and the medications used in OAT are approved by Swissmedic for this specific indication.

Indirectly, such divergences indicate the failure of creating a coherent OAT framework in Switzerland. Notably, no cantonal system could convince all cantons to adopt it. This is best illustrated by the variation observed in the duration of authorisations: A duration too short creates unnecessary bureaucracy and carries the risk of treatment interruption when the treating physician fails to renew the authorisation in time. An unlimited authorisation, however, generates unreliable data regarding the end of treatments; this means that statistical data are not necessarily up to date. Anticipating this conflict, the federal authority recommended limiting authorisations to two years [31], yet only a few cantons have complied.

Currently, there are neither reliable indicators nor data for measuring the impact of the differing regulation and implementation. Despite this dearth of data, we can nevertheless question the adequacy of the authorisation requirement.

During our interviews, one participant questioned the entire authorisation system. In our assessment, this is a critical question, which we will now discuss in detail. To this purpose, we will first identify the possible aims of the requirement and then review alternative ways to reach the same goal.

When the cantonal authorisation for OAT was introduced in the NarcA, the federal Parliament mentioned preventing abuse as a justification [32, 33]. The main objectives listed in the cantonal documents are to ensure therapy standards and quality, prevent double treatments, and collect statistical data [34, 35].

Regarding the first aim, i.e., ensuring therapy standards, it should not be the cantonal physicians’ responsibility to create medical standards [21]. They lack the medical expertise and the time to gather the scientific data supporting a medical consensus. This task belongs to medical societies, and they have performed it – at least in part [36, 37]. Cantonal physicians also lack access to the medical dossier of the person in OAT; thus, they cannot truly verify the suitability of an individual treatment.

Variations in training requirements for physicians requesting an OAT authorisation is surprising. Different standards are required and various trainings offered, the most rigid regime being indication centre systems. Such overly restrictive systems are likely against the original intent of federal authorities. Indeed, the commentary of the federal narcotics addiction ordinance explained in 2011 that OAT is a standard medical practice [31].

For the second goal, i.e., preventing double treatments, national statistics show that double treatments still occur annually [16]. We argue that, without strong inter-cantonal collaboration, this aim cannot be achieved. For instance, a Swiss-wide simple declaration system could be considered via a secured online central database.

Regarding the third objective, i.e., collecting data for statistical purposes: currently, the collected statistical data are not fully exploitable due to different data formats [16]. Although most cantons now use the substitution-online platform, the yearly published statistics only consistently provide the most basic information, such as age and sex of the person and the molecule used in OAT [18]. The situation is worsened by the fact that Zürich, which accounted for 17.8% of all persons in OAT in 2020 [18], does not use the platform. Together with Basel-Landschaft, Basel-Stadt, Luzern, and Zug, the cantons not using substitution.ch comprise almost one-third of Switzerland’s OAT treatments.

It is well known that epidemiological data are crucial for sound public health policymaking. However, the simultaneous collection of data for administrative and scientific reasons is questionable:

We did not compare our results with other countries. Three issues restricted us from doing so. First, our initial literature review did not reveal other countries’ OAT implementation data; we confirmed this lack of information with the EMCDDA and Pompidou Group network. Second, we noted that the implementation of OAT regulations in Switzerland’s neighbouring countries (e.g., France and Germany) is more centralised [38]. Last, a comparison made with another federalist country, such as Belgium, would be difficult because OAT legislation would differ overall.

The obvious recommendation would be to harmonise OAT regulations across cantons. This would reduce bureaucracy, work duplication, and incoherence.

However, is harmonisation actually the most effective approach? Considering the lack of data supporting positive effects of an authorisation requirement, and in accordance with the Pompidou Group [8], we recommend removing the authorisation requirement, while simultaneously improving epidemiologic data on OAT and opioid use disorders. The Pompidou Group, the Council of Europe’s drug policy co-operation platform, called for the abolition of prior authorisation schemes in a 2017 report on guiding principles for OAT. [8].

The authorisation system dates back to an earlier period when OAT treatments were off-label and not supported by randomised controlled trials as a gold standard [8]. In other words, today’s context is nothing like the situation in 1975, when there was no scientific evidence. For over 20 years, OAT has been based on medicines approved by oversight agencies; methadone and buprenorphine have been on the model list of essential medicines since 2006 [39]. We thus argue that OAT has become a standard medical treatment for a chronic disease and should be treated as such.

We agree with the Pompidou Group that eliminating authorisation requirements would improve treatment availability, accessibility, and acceptability [8]. The complicated authorisation systems and the attached administrative constraints can limit the number of physicians and pharmacies willing to offer OAT. Removing such authorisations would certainly alleviate the current lengthy bureaucratic processes. For the person in OAT, being subject to burdensome constraints that compromise his or her privacy can discourage the person from even searching for treatment. Furthermore, removing the licencing requirement would likely reduce stigma for an already vulnerable demographic. To anticipate critics who fear double treatments (i.e., a person receiving OAT treatment twice), implementing a simpler declaration mechanism should be considered [8].

The apprehension that removing authorisation stipulations would lead to diversion can be assuaged by the fact that the cantons with the slimmest regulation have, to their and our knowledge, not experienced more adverse consequences — at least when compared to the cantons with the strictest regulations. Again, there is no study, to date, that indicates an authorisation system impacts the diversion of medicines. Additionally, the substances prescribed in OAT are also used as analgesics without requiring any authorisation at all; yet the supposed risk of diversion also exists in this context.

Removing the authorisation requirement would reinforce the message that treating opioid use disorders and offering OAT is a basic responsibility of all healthcare professionals and simply part of routine medical care. It will also be crucial to maintain support for prescribers and dispensers to maintain high OAT quality. OAT training should be part of the standard medical curriculum, and training on addictions, in general, should be encouraged. Furthermore, it should be made easy for general practitioners to obtain an expert opinion when faced with difficult situations.

A fundamental limitation of our methodology is the limited time we had during interviews to cover various topics, including OAT with the cantonal physicians and cantonal pharmacists. Had we had more time, we could have gone into greater detail about the reasoning underlying certain processes. Further research is required to understand why cantons have implemented the regulation the way they have.

Our study is a snapshot in time. Cantonal physicians and cantonal pharmacists, but also cantonal regulations and OAT guidelines, might have now changed. In addition, our study was conducted during the COVID-19 global pandemic, meaning that the cantonal physicians and cantonal pharmacists had a demanding workload related to the pandemic.

No data available could be used to compare the impact of cantonal regulations regarding OAT access, availability, and acceptability.

Moreover, we interviewed only the cantonal physicians and cantonal pharmacists responsible for administering OAT. Further studies are needed to gather reliable data and feedback from general practitioners and pharmacists, who must comply with cantonal regulations.

Likewise, we did not study specifically the impact that these different systems have on physicians, pharmacists, and persons in OAT. Better quality and comparable data would be required for that.

In conclusion, although most cantons use the same web-based platform to manage authorisations, the practices and regulations still differ. We found diverging rules and practices regarding OAT authorisations concerning the type of authorisation (specific person treated vs general), administrative procedures, and who can set the indication – despite there being no scientific evidence supporting these varying approaches. The most obvious rectification would be to harmonise cantonal systems and to gather uniform data. However, as we contend, the entire system’s adequacy must be questioned.

The data presented in this study are available to other researchers on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available to maintain participant anonymity. It is necessary to keep data confidential, even in anonymised format, because it might be comparatively easy to ascertain participant identity. A re-identification waiver will thus be required to access the data.

We would like to thank the cantonal health officials for taking the time, during a global pandemic, to participate in the interviews and openly answer our questions.

Author contributions: Caroline Schmitt-Koopmann: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualisation. Carole-Anne Baud: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing, Project administration. Stéphanie Beuriot: Formal analysis, Writing – Review & Editing. Barbara Broers: Writing – Review & Editing. Valérie Junod: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Olivier Simon: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration

This research was funded by Schweizerische Nationalfonds zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung (Swiss National Science Foundation, SNSF), grant number 182477.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript was disclosed.

1. Nordt C, Vogel M, Dey M, Moldovanyi A, Beck T, Berthel T, et al. One size does not fit all-evolution of opioid agonist treatments in a naturalistic setting over 23 years. Addiction. 2019 Jan;114(1):103–11. 10.1111/add.14442

2. Santo T Jr, Clark B, Hickman M, Grebely J, Campbell G, Sordo L, et al. Association of Opioid Agonist Treatment With All-Cause Mortality and Specific Causes of Death Among People With Opioid Dependence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021 Sep;78(9):979–93. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0976

3. Stotts AL, Dodrill CL, Kosten TR. Opioid dependence treatment: options in pharmacotherapy. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009 Aug;10(11):1727–40. 10.1517/14656560903037168

4. Strang J, Volkow ND, Degenhardt L, Hickman M, Johnson K, Koob GF, et al. Opioid use disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020 Jan;6(1):3. 10.1038/s41572-019-0137-5

5. World Health Organization. Guidelines for the psychosocially assisted pharmacological treatment of opioid dependence [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009 [cited 2021 Aug 23]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43948

6. Nicholas R. Opioid Agonist Therapy in Australia: A History [Internet]. Adelaide: National Centre for Education and Training on Addiction (NCETA), Flinders University; 2022 [cited 2022 Aug 31]. Available from: http://www.connections.edu.au/opinion/opioid-agonist-therapy-australia-history#

7. Priest KC, Gorfinkel L, Klimas J, Jones AA, Fairbairn N, McCarty D. Comparing Canadian and United States opioid agonist therapy policies. Int J Drug Policy. 2019 Dec;74:257–65. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.01.020

8. Expert group on the regulatory framework for the treatment of opioid dependence syndrome and the prescription of opioid agonist medicines. Opioid agonist treatment. Guiding principles for legislation and regulations [Internet]. Strasbourg: Groupe Pompidou/Conseil de l’Europe; 2017 p. 14,15. Available from: https://idpc.net/fr/publications/2018/08/traitements-agonistes-opioides-principes-directeurs-pour-les-legislations-et-reglementations

9. Amey L, Brunner N. Traitement de substitution à la dépendance aux opioïdes - Etude de la réglementation de quelques pays francophones. Neuchâtel; 2013 p. 20, 21, 24, 25, 37.

10. Casselman J, Meuwissen K, Opdebeeck A. Legal Aspects of Substitution Treatment: An Insight into nine EU Countries [Internet]. EMCDDA; 2003. Available from: https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/html.cfm/index10273EN.html

11. Jin H, Marshall BD, Degenhardt L, Strang J, Hickman M, Fiellin DA, et al. Global opioid agonist treatment: a review of clinical practices by country. Addiction. 2020 Dec;115(12):2243–54. 10.1111/add.15087

12. Prathivadi P, Sturgiss EA. When will opioid agonist therapy become a normal part of comprehensive health care? Med J Aust. 2021 Jun;214(11):504–505.e1. 10.5694/mja2.51095

13. Art. 29d BetmG [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/1952/241_241_245/en#art_29_d

14. Art. 3e para.1-2 BetmG [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/1952/241_241_245/en#art_3_e

15. BetmSV - Verordnung vom 25. Mai 2011 über Betäubungsmittelsucht und andere suchtbedingte Störungen (Betäubungsmittelsuchtverordnung, SR 812.121.6) [Internet]. May 25, 2011. Available from: https://fedlex.data.admin.ch/eli/cc/2011/364

16. Labhart F, Maffli E. Nationale Statistik der Substitutionsbehandlungen mit Opioid-Agonisten – Ergebnisse 2020. Lausanne: Sucht Schweiz; 2021.

17. Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH). Substitution-assisted treatments in case of opioid dependence [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Aug 18]. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/gesund-leben/sucht-und-gesundheit/suchtberatung-therapie/substitutionsgestuetzte-behandlung.html

18. Jährliche Statistik Substitution. 2020 [Internet]. [cited 2022 Aug 25]. Available from: https://www.substitution.ch/de/jahrliche_statistik.html&year=2020&full

19. Gmel G, Labhart F, Maffli E. Heroingestützte/ diacetylmorphingestützte Behandlung in der Schweiz - Resultate der Erhebung 2019 (Forschungsbericht Nr. 118) [Internet]. Lausanne: Sucht Schweiz; 2020 Sep p. 39. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/dam/bag/de/dokumente/npp/sucht/hegebe/erhebungen/hegebe_schweiz_2019.pdf.download.pdf/HeGeBe-Jahresbericht_2019.pdf

20. Schmitt-Koopmann C, Baud CA, Junod V, Simon O. Switzerland’s Narcotics Regulation Jungle: Off-Label Use, Counterfoil Prescriptions, and Opioid Agonist Therapy in the French-Speaking Cantons. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Dec;18(24):13164. 10.3390/ijerph182413164

21. Baud CA, Junod V, Schmitt-Koopmann C, Simon O. Rôle des cantons en matière de traitements de la dépendance. Jusletter [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Feb 13];(1140). Available from: https://jusletter.weblaw.ch/juslissues/2023/1140/role-des-cantons-en-_6d593f126e.html__ONCE&login=false 10.38023/7b1358f3-0990-429a-bb33-297ffb9c10b2

22. Bengtsson M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open. 2016 Jan;2:8–14. 10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001

23. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013 Sep;13(1):117. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

24. Plus MA. 2022 [Internet]. Berlin: VERBI Software; 2022. Available from: www.maxqda.com

25. Patton MQ. Qualitative Analysis and Interpretation. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Sage publications; 2014. pp. 519–649.

26. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008 Apr;62(1):107–15. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

27. Art. 9 para.1 BetmSV [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/2011/364/de#art_9

28. See for example: État de Fribourg. Traitement de substitution formulaire d'admission. https://www.fr.ch/sites/default/files/contens/smc/_www/files/pdf88/kt-fr_start_fr.pdf

29. Valais - Mehrparteientherapievertrag für die Substitutionsbehandlung opiatabhängiger Personen. no longer online accessible.

30. Art. 8 para.2 BetmSV [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/2011/364/de#art_8

31. Bundesamt für Gesundheit. Erläuterungen zu den Verordnungen BetmKV und BetmSV (Commentaires sur Ordonnances OAStup et OCStup) [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2020 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.admin.ch/ch/f/gg/pc/documents/1698/Berichte_1_2.pdf

32. BO 1974 IV 1444 [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 12]. Available from: https://www.amtsdruckschriften.bar.admin.ch/viewOrigDoc/20003209.pdf?ID=20003209

33. BO 1974 V 596 [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 12]. Available from: https://www.amtsdruckschriften.bar.admin.ch/viewOrigDoc/20003534.pdf?ID=20003534

34. LU - Vademecum Betäubungsmittelgestützte Behandlung im Kanton Luzern. («Substitutionstherapie») [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2021 Jan 5]. Available from: https://gesundheit.lu.ch/-/media/Gesundheit/Dokumente/Heilmittel/Vademecum_Substitutionstherapie.pdf?la=de-CH

35. NE - Recommandations du médecin cantonal concernant la prescription de stupéfiants destinés au traitement de personnes dépendantes [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2021 Mar 18]. Available from: https://www.ne.ch/autorites/DFS/SCSP/medecin-cantonal/Documents/RecommMethadone_2017.pdf

36. Hämmig R, Société Suisse de Médecine de l’Addiction (SSAM). Substitutionsgestützte Behandlungen (SGB): neue Empfehlungen/Traitements basés sur la substitution (TBS): nouvelles recommandations. 2014 Nov 6; Fribourg.

37. Praxis-Suchtmedizin [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jul 27]. Available from: https://praxis-suchtmedizin.ch/index.php/de/

38. Muscat R. Pompidou Group. Treatment systems overview [Internet]Strasbourg: Council of Europe Pub.; 2010.[ [cited 2019 Oct 4]], Available from https://rm.coe.int/1680746114

39. World Health Organization. World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. World Health Organization; 2019.

The appendix is available in the pdf version of the article at https://doi.org/10.57187/smw.s.3629.