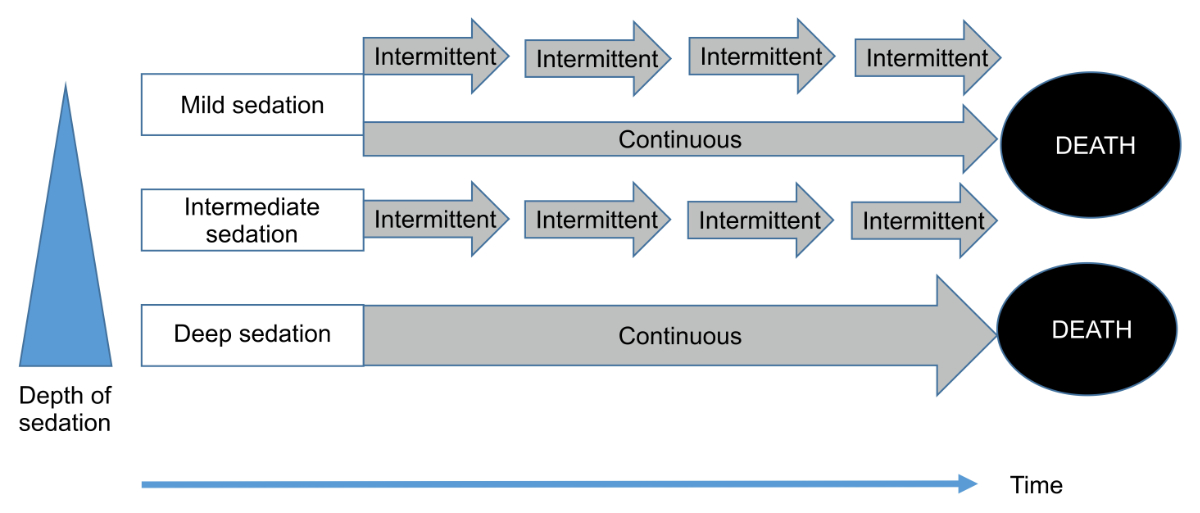

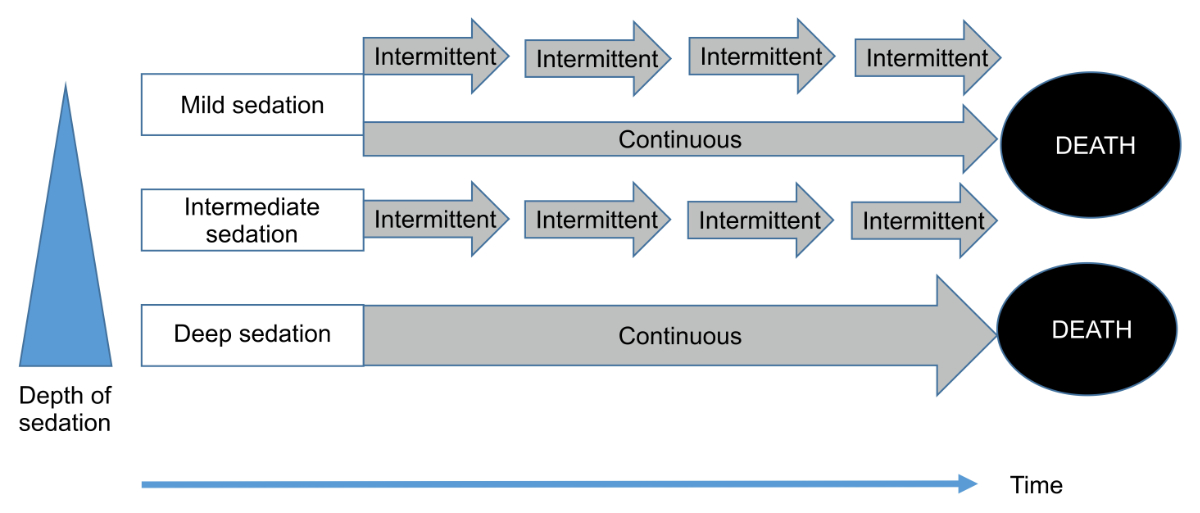

Figure 1Types of palliative sedation (depth and duration).

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.3590

Patients in the final phase of life often have to cope with both physical symptoms and psychosocial, spiritual, and existential distress that are refractory to all forms of relief despite optimal palliative care. This refractory distress may cause suffering that patients perceive as intolerable. Therefore, palliative sedation is an important medically and ethically acceptable intervention for these patients as an option to not consciously experience this suffering [1–6]. Various definitions and guidelines for palliative sedation have been described in the literature [7]. A systematic review identified and compared national and regional clinical practice guidelines for palliative sedation within the European Association of Palliative Care’s (EAPC) palliative sedation framework [8]. Standardised criteria for guideline development (AGREE II) were used to assess their quality [9]. Only three guidelines from Japan [10], the Netherlands [11], and Spain [12] met the quality criteria for the developmental process.

The EAPC defines palliative sedation in the context of palliative medicine as “an intervention aiming to alleviate intolerable suffering resulting from one or a combination of symptoms. It is an intervention that is monitored and deliberate, differentiating it from situations where sedation is a side effect of treatment” ([6], p. 1725).

Sedation is also used in palliative medicine in the following settings [1]:

It is important to mention that palliative sedation is distinguished by two essential clinical parameters: the depth and duration of palliative sedation (figure 1). The three depth levels are defined [2] as follows:

Figure 1Types of palliative sedation (depth and duration).

Regardless of depth, the duration of palliative sedation is defined as follows:

Some authors have recommended that (a) the depth of the sedation should be as low as possible to relieve patient suffering [1, 2, 6, 13, 14] and (b) palliative sedation should be intermittent, except for emergencies or if its intermittent cessation is inappropriate due to a very high likelihood of the patient suffering massive distress during its weaning.

The most reported refractory symptoms indicating the need for palliative sedation are delirium (41%–83%), pain (25%–65%), and dyspnea (16%–59%) [7]. The type and terminology of palliative sedation vary in the literature (e.g. proportional sedation, deep intermittent sedation, and continuous deep sedation until death) [7]. Therefore, clinicians should be aware that the wording and definitions vary considerably, and no universally accepted terminology currently exists [15–17].

The double effect, proportionality, and autonomy are the main ethical principles for palliative sedation therapy in the literature [18, 19].

The prevalence of palliative sedation has recently increased. The frequency of continuous sedation until death in the international literature increased from 3–10% between 2000 and 2006 [20] to 12–18% between 2006 and 2019 [21, 22].In Switzerland, the proportion of patients who died under a continuous deep sedation until death increased from 4.7% in 2001 to 17.5% in 2013 [22, 23]. Death preceded by continuous deep sedation occurred more frequently in the Italian-speaking region (34.4%) than in the French-speaking (26.9%) and German-speaking (24.4%) regions of Switzerland [23]. A cross-sectional death certificate study conducted in Switzerland in 2018 suggested that continuous deep sedation until death was strongly associated with potentially life-shortening medical end-of-life decisions [24]. Moreover, the rates of palliative sedation use varied significantly between different institutions in the same cultural and healthcare regions [17].

Sedation in other clinical settings has different aims. For example, in acute psychiatry, it is used as an option to temporarily bridge acute agitation situations that may lead to self-harming in the patients or to prevent severe violence against healthcare professionals or other patients. In contrast, in emergency, perioperative, and intensive care settings, it is used to facilitate the conduction of procedures (i.e. diagnostic or surgical interventions or invasive ventilation).

Uncertainties regarding the definitions and practice of palliative sedation may cause inadequately trained and inexperienced healthcare professionals to conduct incorrect or inappropriate palliative sedation [25, 26]. Therefore, the expert members of the Bigorio group and the authors of this manuscript believe that national recommendations should be published and made available to healthcare professionals to provide practical, terminological, and ethical guidance. The Bigorio group is the working group of the Swiss Palliative Care Society whose task is to publish clinical recommendations at a national level in Switzerland. These recommendations aim to provide guidance on the most critical questions and issues related to palliative sedation.

For many years, the Bigorio best practice recommendations have guided palliative care actors in a well-founded manner and thus promote the harmonisation of approaches in this palliative care field. The 2005 recommendations on palliative sedation are a four-page document based on the experience and expertise of a panel of palliative care professionals [27]. For historical reasons, like the other formerly developed Bigorio recommendations, the 2005 recommendations were developed at a yearly best practice conference by a small group of senior palliative care healthcare professionals in the monastery at Bigorio, Ticino. Above all, these documents were intended to be very practical, succinct, and based only on their authors’ personal experience and expertise. As such, a dedicated literature review did not precede the document’s development. Instead, a structured feedback process to include suggestions and criticism from professionals outside this writing committee and the writing board was chosen randomly and not officially mandated.

To overcome the potential for flaws of this traditional process and to allow for a more transparent and literature-based process, the current guidelines were intended to follow preliminarily developed, standardised proceedings, including the following steps.

First, the guidelines working group from the Swiss Society of Palliative Care established a writing board comprising three physicians (MB, JP, and MM), one ethicist (MT), and two academic (“national”) experts (SE and JG). Second, the framework of the revision paper was defined in an online conference of this writing board. Third, the writing board created a first draft based on a narrative literature review. Fourth, an internal review (n = 12) of the draft was conducted at five academic institutions (Lausanne, Geneva, Bern, Zürich, and Basel) and included the heads of all working groups of the Swiss Society of Palliative Care (Physicians, Nurses, Spiritual Care, Quality, Education, Research, and Financing). This final review included four topics: (i) relevance, (ii) appropriateness of the content, (iii) regional specificities, and (iv) problematic aspects and free text feedback. Four answers were received (response rate: 30%), including two with specific comments. Fifth, the comments from the internal review phase were reviewed and discussed in subsequent online meetings and, whenever possible, integrated into the current recommendations. All authors validated the final draft. The 2022 revision paper objectives bring several novelties: (a) a higher scientific level accounting for the latest articles on palliative sedation, (b) some chapters have been expanded (decision-making process, monitoring of palliative sedation, and communication with the family), and (c) a chapter dedicated to specific ethical issues with palliative sedation such as existential distress or associations with end-of-life decisions has been added.

High-quality clinical research on palliative sedation is limited [7, 8, 28]. Moreover, research on the decision-making process and guidelines before administering palliative sedation differ substantially across institutions, partly due to ambiguous and variable terminology [7, 16, 29, 30]. If palliative sedation is considered and judged to be adequate and feasible by the treating physician and the multi-professional team, consultation with a palliative care specialist is strongly recommended whenever feasible. The palliative care specialist can ensure that all available alternatives for alleviating symptoms and distress have been considered and that high-quality palliative sedation is administered if selected [6]. Most importantly, a shared decision-making process involving a multidisciplinary team should be instigated whenever possible before the decision to initiate palliative sedation. Palliative sedation and potential alternatives should be thoroughly explained and discussed with the patient and, depending on their priorities, with their family or significant others. The following parameters should be evaluated based on the clinical evaluation (medical history, physical examination, and relevant investigations) of the patient:

Figure 2The decision-making process for palliative sedation.

Many published guidelines recommend that palliative sedation only be used for patients with a limited life expectancy or “at the end of life”. The described ranges vary from some hours to a few days [1, 32, 33] before death. Some guidelines stipulate that a condition for deep and continuous sedation until death is that death must be expected within one to two weeks [2, 31].

The authors of this manuscript recommend that palliative sedation should only be given to patients whose life expectancy does not exceed four weeks. However, deep and continuous sedation until death should only be offered to patients whose life expectancy is estimated as a few hours to one week at most.

Outside of urgent and acute clinical situations, the aims, benefits, and risks of palliative sedation should be discussed and, whenever possible, anticipated before decision-making. Permission from a substitute decision-maker should be obtained if patients lack decision-making capacity and no advance directive exists. The assessment of decision-making capacity should follow available guidance from, for example, the Swiss Association of Medical Societies (SAMS) [34]. If the patient has not declared any advance directives and no substitute decision-maker is available, a team that includes palliative care specialists must reach a consensus that palliative sedation is the best clinical and ethical option.

Table 1Checklist of procedures before palliative sedation.

| Theme | Decision | |

| √ | Determine the duration of palliative sedation | Intermittent |

| Continuous | ||

| √ | Determine the depth of palliative sedation | Mild |

| Intermediate | ||

| Deep | ||

| √ | Determine the drug to initiate palliative sedation | Midazolam |

| Other | ||

| √ | Determine the type of monitoring | RASS-PAL |

| Other | ||

| √ | Determine whether to continue hydration/alimentation. | Yes |

| No | ||

| √ | Determine which drugs to stop. | … |

| √ | Determine which drugs to continue. | … |

| √ | Determine whether a bladder catheter would be helpful. | Yes |

| No | ||

| √ | Determine a support plan. | Family |

| Team |

RASS-PAL: Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale-Palliative.

Discuss and decide with the patient whether to introduce or suspend hydration or nutrition independent of palliative sedation.

Based on the required depth and duration of palliative sedation, properly define the type required as emergency, temporary, or continuous until death, based on the clinical setting (i.e. inpatient or community).

Define the drug(s) and the administration route; only use medication with a direct sedative effect.

Determine the depth of palliative sedation, depending on the type required. Deeper sedation should be administered only when mild sedation is ineffective. The depth of sedation should be based on the patient’s suffering. Note that suffering can sometimes be relieved without altering the patient’s ability to communicate.

Determine whether clinical monitoring is indicated and, if so, determine its type based on the situation and treatment goals. For temporary sedation, vital parameters (e.g. respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, heart rate, and blood pressure) should be monitored. When the care goal is to ensure comfort, deep sedation until death should be used, and only critical parameters relevant to the patient’s comfort should be monitored. Minimal monitoring should always include respiration rate and sedation depth.

Administer a test dose of midazolam to assess its immediate pharmacologic effects and the patient’s perception. This step may help demystify the negative perceptions of palliative sedation.

Always continue treatments for other symptoms (e.g. analgesic treatment).

Consider whether a bladder catheter is helpful to the patient.

Define which nursing activities should be performed during palliative sedation.

Plan support for the family and the team.

Document the palliative sedation in the health record, including the following issues:

When there is no time to follow the above guidelines, the consent process should be followed and documented retrospectively whenever possible. If sedation occurs unintentionally, the dose of the drug(s) causing sedation should be lowered so that the patient can regain consciousness, or the process (including the multi-professional team decision) should be followed retrospectively.

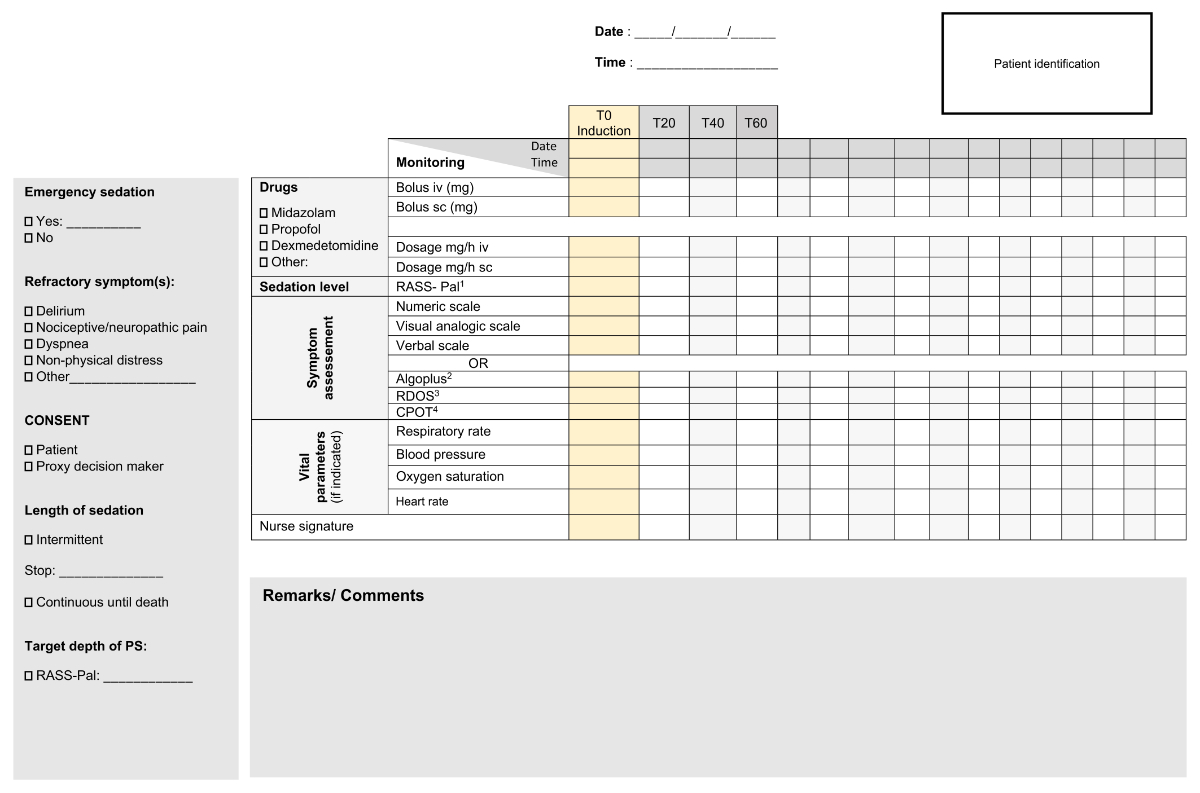

We strongly recommend documenting the conduct and monitoring of palliative sedation using a written/electronic monitoring protocol [6]. After administration of an initial bolus of the chosen sedative, the patient should be assessed continuously at the bedside by a skilled physician or nurse until the maximum drug effect is achieved according to the chosen administration route and the drug’s pharmacokinetics (i.e. 60 minutes for SC midazolam and dexmedetomidine). Thereafter, the patient should be monitored at least once every 20 minutes until their symptoms are relieved and then at least once daily to ensure adequate sedation levels.

The indicators for symptom control (i.e. facial expression and respiratory rate) and sedation depth should be monitored simultaneously. Palliative sedation should be maintained at a depth that enables relief from the targeted refractory symptom(s).

The following parameters should be monitored:

Table 2Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale.

| Score | Term | Description |

| +4 | Combative | Overtly combative, violent, immediate danger to staff (e.g. throwing items): with or without attempting to get out of the bed or chair. |

| +3 | Very agitated | Pulls or removes lines (e.g. IV/SC/oxygen tubing) or catheter(s); aggressive, with or without attempting to get out of the bed or chair. |

| +2 | Agitated | Frequent non-purposeful movements, with or without attempting to get out of the bed or chair. |

| +1 | Restless | Occasional non-purposeful movements, but movements are not aggressive or vigorous. |

| 0 | Alert and calm | |

| –1 | Drowsy | Not fully alert but has sustained awakening (eye opening/contact) to voice for at least 10 seconds. |

| –2 | Light sedation | Briefly awakens with eye contact to voice for less than 10 seconds. |

| –3 | Moderate sedation | Any movement (eye or body) or eye opening to voice but no eye contact. |

| –4 | Deep sedation | No response to voice, but any movement (eye or body) or eye opening to stimulation by light touch. |

| –5 | Not rousable | No response to voice or stimulation by light touch. |

Scales for monitoring patients with a decreased level of consciousness include the RASS developed for intensive care patients and recommended by the EAPC [1] and the RASS-PAL recommended by the authors [38]. Oral care, eye care, toileting, hygiene, pressure ulcer management, and other nursing activities should be performed according to the patient’s wishes and the estimated risks/harms relating to the care goals determined by the nursing team.

Figures 3 and 4 provide an example of a monitoring document for palliative sedation.

Figure 3Example monitoring sheet for palliative sedation (part 1).

Figure 4Example monitoring sheet for palliative sedation (part 2).

The family should be offered support, encouraged to ask questions, and allowed an opportunity to grieve. Regular meetings for mutual exchange and evaluation are essential. Families should be offered social work, psychosocial palliative care, or spiritual care support as needed.

The multidisciplinary team should anticipate the potential for staff distress and burnout [1, 4, 31]. All participating staff members should understand the rationale for palliative sedation and the care goals. The rationale for palliative sedation should be discussed at team meetings or case conferences before, during, and after the event whenever possible. Discussions should include professional and emotional issues related to palliative sedation decisions and how local procedures can be improved. A formal team debriefing can facilitate discussion of the psychological, social, and emotional impact of palliative sedation cases. Team support fosters a culture of sensitivity and self-care. The authors of these recommendations are aware that some of these resources may not be available in all settings and regions (i.e. home care).

Effective communication and shared decision-making are essential at the end of life, particularly in the decision-making process before and during palliative sedation [39]. Family caregivers should be involved according to the patient’s wishes, preferences, and values. Palliative sedation should be discussed with family members or other key persons in the patient’s life, focusing on the following elements: (a) respecting the patient’s choice, (b) preventing misinterpretation of emotional situations (i.e. palliative sedation is not euthanasia), and (c) clarifying that palliative sedation is for the suffering of the patient and not their family [39]. The patient’s family and significant others may become their voice during palliative sedation. The patient is often in a condition where death could occur at any moment. Well-tailored communication using clear, manageable, and jargon-free language is vital for maintaining a trusting relationship between healthcare professionals and the patient’s family.

Family communication should include several elements. First, the patient’s and family’s level of knowledge about the prognosis, wishes regarding the last days of life, and emotional status should be assessed. Second, the healthcare professional should discuss care goals and priorities, intolerable distress levels, and treatment options. Third, the patient and their family should be assured that cultural and personal wishes will be respected when ethically and legally feasible. Fourth, the aim, process, and risks of palliative sedation should be discussed. The distinction between palliative sedation, euthanasia, and assisted dying should be explained, and nursing care and medical treatment during sedation should be discussed. Lastly, it should be explained and strongly emphasised that the main aim of palliative sedation is to alleviate patient suffering and not to ease nursing or family needs (e.g. restlessness may not necessarily be a source of suffering for the patient, while it may be burdensome for accompanying family members and professional carers).

Immediately before initiating palliative sedation, families should have the opportunity to communicate and even say goodbye to the patient, if appropriate [39]. The family should be advised on how they can be involved in the palliative sedation process, how to communicate with the patient, how care will be provided to ensure the patient’s comfort, and the normal dying process. The family should be reassured about the patient’s comfort. If possible, intermittent palliative sedation is preferable to allow communication on the patient’s level of distress and to consider their changing wishes.

Opioids should not be used for palliative sedation but should be continued as needed to alleviate pain and breathlessness [2].

Midazolam is the first-line drug mentioned in most published guidelines [1, 2, 8, 9] as a single sedative for palliative sedation (monotherapy). It is usually administered via continuous intravenous or subcutaneous infusion. A systematic review of palliative sedation guidelines showed that drug dosing varies significantly in practice [10].

The authors recommend midazolam as the first-line drug for palliative sedation. If indicated, the starting dose forinduction should be a 0.5–1 mg intravenous injection, repeated every 3–4 min until the target depth of sedation is achieved. The dose should be reduced if severe renal and/or hepatic failure occurs or the patient is elderly. The patient’s tolerance should be determined after the first dose and adapted if required. Intolerance may be due to paradox effects such as anxiety or restlessness, but also that the patient simply does not experience the drug effect as pleasant (i.e. “dull” or “strange” feeling in the head). If an intravenous injection is impossible, 1–3 mg subcutaneous injections should be administered every 10–15 min. The maintenance dose (mg/h) should be 50% of the total cumulative dose administered during the induction. Initial midazolam doses are usually less than 50 mg/24 hours [7].

Alternative drugs mentioned in the literature include the following:

Dexmedetomidine: Dexmedetomidine is a selective α2 adrenergic receptor agonist approved for sedation during mechanical ventilation and perioperative anaesthesia. Case studies suggest that dexmedetomidine is effective in relieving intractable pain [40] and delirium [41, 42] and can be safely used in an inpatient palliative care setting [43, 44]. In addition to its analgesic properties, dexmedetomidine relieves agitation. Furthermore, dexmedetomidine delivers “arousable sedation”, as it was called by its developers and early researchers of its clinical properties, meaning that patients are easily awakened and are usually oriented and able to communicate their level and source of distress. Many relatives and healthcare professionals find conscious sedation helpful because they can communicate with and monitor the patient. Moreover, dexmedetomidine does not depress respiration like propofol, opioids, and benzodiazepines.

Levomepromazine: Levomepromazine was mentioned as a second-line drug for palliative sedation in previous Bigorio recommendations. It is no longer officially available in Switzerland in the parenteral form. However, it can be obtained from abroad and is still widely used in palliative care units, particularly for refractory delirium. In patients given neuroleptics like levomepromazine, hypoactive delirium or rigour may give the misleading impression of a “silent” and “comfortable” patient who is, in reality, unable to communicate their level of suffering. Nonetheless, some international guidelines mention levomepromazine and other neuroleptics as second-line drugs for treating severe agitation. Levomepromazine should be used cautiously when all other measures fail. However, for severe psychotic symptoms (i.e. hallucinations), other classic neuroleptics, such as haloperidol, should be used in addition to sedatives to treat the psychiatric symptoms.

Propofol: Limited reports (case series or reports) are available on using propofol for palliative sedation [45, 46]. They indicate that intravenous propofol is safe and effective if used in an acute palliative care unit by experienced physicians. We do not recommend propofol for sedation at home or in a nursing home.

Palliative sedation is a complex issue and often leads to difficult clinical and ethical questions. This section aims to explore two controversial indications for palliative sedation: non-physical distress, such as existential suffering, and the wish to hasten death. The general reflections presented below do not replace the clinical and ethical decisions made by the responsible physicians and teams for individual patients.

Palliative sedation is often used to treat physical symptoms. However, in rare situations, patients continue to suffer even when all their physical symptoms are relieved by therapies other than sedation. Non-physical distress may be due to psychological, existential, social, spiritual, or religious distress or all of them [47]. However, in certain situations of intolerable suffering at the end of life, the patient’s physical and non-physical components can be extremely difficult to distinguish. The forms of distress are not clearly defined in the literature [48–50], and no consensus on assessing their intensity and refractoriness has been reached [4]. Non-physical distress is a patient’s subjective perception [51].

If severe existential suffering prevails, patients and their caregivers should seek the advice of specialists, such as psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, spiritual health practitioners, or chaplains, especially if there are signs of demoralisation, social isolation, or withdrawal from communication. If conflicting values are evident, consultation with an ethicist or an ethics committee can be helpful [13, 52]. The integration of specialist palliative care is also strongly recommended. If non-physical distress is intolerable for the patient and refractory to treatment, palliative sedation may be considered. However, palliative sedation should only be initiated after thorough specialist palliative care interventions. Some guidelines state that existential suffering is not an indication for palliative sedation [53].

No consensus has been reached in the literature regarding the appropriate type of sedation for non-physical distress. However, several experts recommend intermittent rather than continuous sedation until death [1]. Temporary sedation is generally limited to 1–2 days, but some authors state that overnight sedation can be an important first step [51, 54]. Temporary sedation can be terminated to care for the patient and evaluate their distress. The EAPC states that continuous deep sedation until death should only be considered after repeated trials of respite sedation [1]. In conclusion, palliative sedation for solely non-physical distress must remain a possible but exceptional last resort that should not be initiated without the cooperation of a specialist palliative care team.

Palliative sedation is an important and necessary option to relieve the intolerable and refractory distress of a patient but should never be initiated to hasten death [1, 13, 52]. However, death may occur naturally during palliative sedation. The impact of palliative sedation on the length of survival has not been established due to the lack of randomised double-blinded studies for ethical reasons. While this issue has been addressed in several articles [55-57], the data analysis is often methodologically biased.

All international and national guidelines state that the intention and action of palliative sedation differ from medically assisted dying (euthanasia and assisted suicide) [1, 4, 13, 52]. Consequently, the use of palliative sedation to hasten death is an unacceptable deviation from normative ethical and legal clinical practices. In all cases, palliative sedation should only be offered in response to a patient’s distress, but not to comply with the patient’s or their family’s wish to hasten death. All available guidelines state that palliative sedation should never be used to hasten death.

Palliative sedation is a complex and controversial practice with many questions that are still being debated. In addition to the guidance provided above, the authors have noted several questions and controversial issues, as follows:

Occasionally, patients are unintentionally sedated during efforts to control acute symptoms. Examples of acute symptoms include a panic attack or acute pain resulting from muscle spasms. The authors do not consider these situations palliative sedation because reduced consciousness is not the primary intention. However, if sedation persists, retrospective follow-up and documentation of all aspects of the normal decision-making process before initiating palliative sedation, as described above, may be appropriate.

Delirium, a frequent and complex end-of-life symptom, is challenging to manage, and the best treatment for refractory delirium is unclear. In the last days of life, progressive organ failure often impacts cognition, vigilance, and emotions and precipitates delirium [58]. Up to 90% of patients become delirious at the end of life. However, these numbers may be overestimated due to the lack of tools to identify delirium at the end of life. The normal dying process may trigger false positives using the available delirium screening tools for hypoactive delirium [39, 59]. According to the literature, hyperactive delirium is the main indication for palliative sedation [7]. Agitation secondary to fear or distress from other symptoms should be excluded before initiating palliative sedation. Delirium, which is often associated with hallucinations, may also be drug-induced by opioids, benzodiazepines, and drugs with anticholinergic properties. Since benzodiazepines can exacerbate delirium and induce disorientation, palliative sedation with only midazolam can cause a vicious downward spiral of more confusion–more midazolam–more agitation–more midazolam, resulting in profound but unnecessary sedation. Notably, delirium cannot be successfully treated pharmacologically, but some especially pronounced symptoms of delirium demand medication (i.e. hallucinations: neuroleptics; fear and agitation: benzodiazepines) [60].

Palliative sedation guidelines were developed in the context of specialised palliative care. However, in Switzerland, only 8% of continuous deep sedation until death occurs in palliative care units and hospices [24]. Therefore, most palliative sedation occurs outside specialised palliative care units. Consequently, recommending that palliative sedation be practised only in specialised settings is unrealistic, even if such an environment is probably the best. While any physician can perform palliative sedation, the authors strongly recommend consulting a specialised palliative care team or even integrating a specialised palliative care team into the decision-making process and monitoring the progress of palliative sedation. Performing palliative sedation can be stressful for physicians/nurses and cause uncertainty about ethical and legal limits [61]. Training and interdisciplinary and multi-professional evaluation with colleagues to deal with prognostic uncertainties, refractory symptoms, palliative sedation guidelines, ethical considerations, and pharmacology are essential. Since palliative care specialists are trained in all aspects of palliative sedation, they can add significant value to this delicate process and should at least be available for non-palliative-care specialists.

Conducting palliative sedation successfully and safely at home is difficult but possible if the patient’s wish is clear and family support is available. In this situation, the authors recommend that a specialist palliative care team be available 24/7 for the first-line caregivers. A clearly defined, 24-hour accessible alternative destination (hospital or palliative care unit) is another mandatory requirement for successful palliative sedation at home.

Like many palliative sedation guidelines, this revision paper has a low level of evidence. The authors have, whenever possible, based their recommendations on scientific references, but their practice and clinical experience have strongly influenced the paper’s content. A structured Delphi process would have been helpful, but the project’s resources did not allow this. Therefore, the representativeness of all Swiss palliative care institutions is not optimal. Data collection from all practices of palliative sedation in Swiss palliative care institutions would have improved the validity of our revision paper.

Palliative sedation is clinically, communicatively, ethically, legally, and emotionally complex. It must be conducted with clinical and ethical accuracy and competency to avoid harm and ethically questionable practices. It must never be used as a means to hasten death, and its use for non-physical, existential suffering should remain a last resort. Specialist palliative care teams should be consulted before initiating palliative sedation to avoid overlooking other potential treatment options for the patient’s symptoms and suffering.

We hope that the Bigorio recommendations presented in this revision paper will provide helpful guidance for the decision-making process and use of palliative sedation. However, we are aware of the ethical and clinical complexity of palliative sedation, even within the palliative care specialist community in Switzerland. Beyond this vital step toward harmonisation of palliative sedation practices in Switzerland, continued dialogue and exchange among experts and stakeholders are needed to align opinions and attitudes regarding palliative sedation.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript was disclosed.

1. Cherny NI, Radbruch L; Board of the European Association for Palliative Care. European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) recommended framework for the use of sedation in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2009 Oct;23(7):581–93. 10.1177/0269216309107024

2. de Graeff A, Dean M. Palliative sedation therapy in the last weeks of life: a literature review and recommendations for standards. J Palliat Med. 2007 Feb;10(1):67–85. 10.1089/jpm.2006.0139

3. Tomczyk M, Viallard ML, Beloucif S. [Current status of clinical practice guidelines on palliative sedation for adults in French-speaking countries]. Bull Cancer. 2021 Mar;108(3):284–94. 10.1016/j.bulcan.2020.10.011

4. Cherny NI; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of refractory symptoms at the end of life and the use of palliative sedation. Ann Oncol. 2014 Sep;25 Suppl 3:iii143–52. 10.1093/annonc/mdu238

5. Handlungsempfhelung EINSATZ SEDIERENDER MEDIKAMENTE IN DER SPEZIALISIERTEN PALLIATIVVERSORGUNG. Forschungsverbund SedPall. DGP; 2021.

6. Surges SM, Garralda E, Jaspers B, Brunsch H, Rijpstra M, Hasselaar J, et al. Review of European Guidelines on Palliative Sedation: A Foundation for the Updating of the European Association for Palliative Care Framework. J Palliat Med. 2022 Nov;25(11):1721–31. 10.1089/jpm.2021.0646

7. Arantzamendi M, Belar A, Payne S, Rijpstra M, Preston N, Menten J, et al. Clinical Aspects of Palliative Sedation in Prospective Studies. A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021 Apr;61(4):831–844.e10. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.09.022

8. Abarshi E, Rietjens J, Robijn L, Caraceni A, Payne S, Deliens L, et al.; EURO IMPACT. International variations in clinical practice guidelines for palliative sedation: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017 Sep;7(3):223–9. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001159

9. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al.; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec;182(18):E839–42. 10.1503/cmaj.090449

10. Japanese Society for Palliative Medicine. Guidelines for sedation for pain relief., in http://www.jspm.ne.jp/guidelines/sedation/sedation01.pdf. 2015.

11. Committee on National Guideline for Palliative Sedation. Utrecht, Guideline for palliative sedation, in http://palliativedrugs.com/download/091110_KNMG_Guideline_for_Palliative_sedation_2009__2_[1].pdf. 2009.

12. Organización Médica Colegial (OMC) and Sociedad Española de Cuidados Paliativos. (SECPAL), Guía de Sedación Paliativa, in https://www.cgcom.es/sites/default/files/guia_sedacci. 2012.

13. Dean MM, Cellarius V, Henry B, Oneschuk D, Librach Canadian Society Of Palliative Care Physicians Taskforce SL. Framework for continuous palliative sedation therapy in Canada. J Palliat Med. 2012 Aug;15(8):870–9. 10.1089/jpm.2011.0498

14. Morita T, Bito S, Kurihara Y, Uchitomi Y. Development of a clinical guideline for palliative sedation therapy using the Delphi method. J Palliat Med. 2005 Aug;8(4):716–29. 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.716

15. Kremling A, Schildmann J. What do you mean by “palliative sedation”?: pre-explicative analyses as preliminary steps towards better definitions. BMC Palliat Care. 2020 Sep;19(1):147. 10.1186/s12904-020-00635-9

16. Kremling A, Bausewein C, Klein C, Schildmann E, Ostgathe C, Ziegler K, et al. Intentional Sedation as a Means to Ease Suffering: A Systematically Constructed Terminology for Sedation in Palliative Care. J Palliat Med. 2022 May;25(5):793–6. 10.1089/jpm.2021.0428

17. Stiel S, Nurnus M, Ostgathe C, Klein C. Palliative sedation in Germany: factors and treatment practices associated with different sedation rate estimates in palliative and hospice care services. BMC Palliat Care. 2018 Mar;17(1):48. 10.1186/s12904-018-0303-7

18. Morita T, Tei Y, Inoue S. Ethical validity of palliative sedation therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003 Feb;25(2):103–5. 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00635-8

19. Rousseau P. The ethics of palliative sedation. Caring. 2004 Nov;23(11):14–9.

20. Miccinesi G, Rietjens JA, Deliens L, Paci E, Bosshard G, Nilstun T, et al.; EURELD Consortium. Continuous deep sedation: physicians’ experiences in six European countries. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006 Feb;31(2):122–9. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.07.004

21. Heijltjes MT, van Thiel GJ, Rietjens JA, van der Heide A, de Graeff A, van Delden JJ. Changing Practices in the Use of Continuous Sedation at the End of Life: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020 Oct;60(4):828–846.e3. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.06.019

22. Bosshard G, Zellweger U, Bopp M, Schmid M, Hurst SA, Puhan MA, et al. Medical End-of-Life Practices in Switzerland: A Comparison of 2001 and 2013. JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Apr;176(4):555–6. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7676

23. Hurst SA, Zellweger U, Bosshard G, Bopp M; Swiss Medical End-of-Life Decisions Study Group. Medical end-of-life practices in Swiss cultural regions: a death certificate study. BMC Med. 2018 Apr;16(1):54. 10.1186/s12916-018-1043-5

24. Ziegler S, Schmid M, Bopp M, Bosshard G, Puhan MA. Continuous deep sedation until death in patients admitted to palliative care specialists and internists: a focus group study on conceptual understanding and administration in German-speaking Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2018 Aug;148:w14657. 10.4414/smw.2018.14657

25. Levy MH, Cohen SD. Sedation for the relief of refractory symptoms in the imminently dying: a fine intentional line. Semin Oncol. 2005 Apr;32(2):237–46. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.02.003

26. Hasselaar JG, Reuzel RP, van den Muijsenbergh ME, Koopmans RT, Leget CJ, Crul BJ, et al. Dealing with delicate issues in continuous deep sedation. Varying practices among Dutch medical specialists, general practitioners, and nursing home physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Mar;168(5):537–43. 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.130

27. palliative ch, Bigorio 2005, Recommandations "Sédation palliative", Consensus sur la meilleure pratique en soins palliatifs en Suisse., in https://www.palliative.ch/public/dokumente/was_wir_tun/angebote/bigorio_best_practice/BIGORIO_2005_-_Recommandations_Sedation_palliative.pdf. 2005: palliative.ch.

28. Beller EM, van Driel ML, McGregor L, Truong S, Mitchell G. Palliative pharmacological sedation for terminally ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jan;1(1):CD010206. 10.1002/14651858.CD010206.pub2

29. Belar A, Arantzamendi M, Menten J, Payne S, Hasselaar J, Centeno C. The Decision-Making Process for Palliative Sedation for Patients with Advanced Cancer-Analysis from a Systematic Review of Prospective Studies. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Jan;14(2):301. 10.3390/cancers14020301

30. Robijn L, Chambaere K, Raus K, Rietjens J, Deliens L. Reasons for continuous sedation until death in cancer patients: a qualitative interview study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2017 Jan;26(1):e12405. 10.1111/ecc.12405

31. Verkerk M, van Wijlick E, Legemaate J, de Graeff A. A national guideline for palliative sedation in the Netherlands. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007 Dec;34(6):666–70. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.01.005

32. The Italian Association for Palliative Care (SICP). Raccomandazioni della SICP sulla Sedazione Terminale/Sedazione Palliativa., in https://www.fondazioneluvi.org/wpcontent/uploads/2017/01/Sedazione-Terminale-Sedazione-Palliativa.pdf. 2012.

33. Joan Santamaria Semis GS, Rosselló Forteza C, et al. 2013., Guía de sedación paliativa: Recomendaciones para los profesionales de la salud de las Islas Baleares, in www.caib.es/sacmicrofront/archivopub.do?ctrl=MCRST3145ZI147433&id=147433. 2013.

34. Académie Suisse des Sciences Médicales (ASSM). La capacité de discernement dans la pratique médicale, in https://www.samw.ch/fr/Publications/Directives.html. 2019.

35. Gélinas C, Fillion L, Puntillo KA, Viens C, Fortier M. Validation of the critical-care pain observation tool in adult patients. Am J Crit Care. 2006 Jul;15(4):420–7. 10.4037/ajcc2006.15.4.420

36. Rat P, Jouve E, Pickering G, Donnarel L, Nguyen L, Michel M, et al. Validation of an acute pain-behavior scale for older persons with inability to communicate verbally: algoplus. Eur J Pain. 2011 Feb;15(2):198.e1–10.

37. Campbell ML, Templin T, Walch J. A Respiratory Distress Observation Scale for patients unable to self-report dyspnea. J Palliat Med. 2010 Mar;13(3):285–90. 10.1089/jpm.2009.0229

38. Bush SH, Grassau PA, Yarmo MN, Zhang T, Zinkie SJ, Pereira JL. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale modified for palliative care inpatients (RASS-PAL): a pilot study exploring validity and feasibility in clinical practice. BMC Palliat Care. 2014 Mar;13(1):17. 10.1186/1472-684X-13-17

39. Crawford GB, Dzierżanowski T, Hauser K, Larkin P, Luque-Blanco AI, Murphy I, et al.; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Electronic address: clinicalguidelines@esmo.org. Care of the adult cancer patient at the end of life: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. ESMO Open. 2021 Aug;6(4):100225. 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100225

40. Mupamombe CT, Luczkiewicz D, Kerr C. Dexmedetomidine as an Option for Opioid Refractory Pain in the Hospice Setting. J Palliat Med. 2019 Nov;22(11):1478–81. 10.1089/jpm.2019.0035

41. Hofherr ML, Abrahm JL, Rickerson E. Dexmedetomidine: A Novel Strategy for Patients with Intractable Pain, Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia, or Delirium at the End of Life. J Palliat Med. 2020 Nov;23(11):1515–7. 10.1089/jpm.2019.0427

42. Thomas B, Lo WA, Nangati Z, Barclay G. Dexmedetomidine for hyperactive delirium at the end of life: an open-label single arm pilot study with dose escalation in adult patients admitted to an inpatient palliative care unit. Palliat Med. 2021 Apr;35(4):729–37. 10.1177/0269216321994440

43. Roberts SB, Wozencraft CP, Coyne PJ, Smith TJ. Dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant analgesic for intractable cancer pain. J Palliat Med. 2011 Mar;14(3):371–3. 10.1089/jpm.2010.0235

44. Gaertner J, Fusi-Schmidhauser T. Dexmedetomidine: a magic bullet on its way into palliative care-a narrative review and practice recommendations. Ann Palliat Med. 2022 Apr;11(4):1491–504. 10.21037/apm-21-1989

45. McWilliams K, Keeley PW, Waterhouse ET. Propofol for terminal sedation in palliative care: a systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2010 Jan;13(1):73–6. 10.1089/jpm.2009.0126

46. Sulistio M, Wojnar R, Michael NG. Propofol for palliative sedation. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020 Mar;10(1):4–6. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-001899

47. Clark D. ‘Total pain’, disciplinary power and the body in the work of Cicely Saunders, 1958-1967. Soc Sci Med. 1999 Sep;49(6):727–36. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00098-2

48. Grech A, Marks A. Existential Suffering Part 1: definition and Diagnosis #319. J Palliat Med. 2017 Jan;20(1):93–4. 10.1089/jpm.2016.0422

49. Boston P, Bruce A, Schreiber R. Existential suffering in the palliative care setting: an integrated literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011 Mar;41(3):604–18. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.05.010

50. Rodrigues P, Crokaert J, Gastmans C. Palliative Sedation for Existential Suffering: A Systematic Review of Argument-Based Ethics Literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018 Jun;55(6):1577–90. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.01.013

51. Twycross R. Reflections on palliative sedation. Palliat Care. 2019 Jan;12:1178224218823511. 10.1177/1178224218823511

52. Imai K, Morita T, Akechi T, Baba M, Yamaguchi T, Sumi H, et al. The Principles of Revised Clinical Guidelines about Palliative Sedation Therapy of the Japanese Society for Palliative Medicine. J Palliat Med. 2020 Sep;23(9):1184–90. 10.1089/jpm.2019.0626

53. Ostgathe C. Einsatz sedierender Medikamente in der Spezialisierten Palliativversorgung, in https://www.dgpalliativmedizin.de/images/210422_Broschu%CC%88re_SedPall_Gesamt.pdf. 2021.

54. Song HN, Lee US, Lee GW, Hwang IG, Kang JH, Eduardo B. Long-Term Intermittent Palliative Sedation for Refractory Symptoms at the End of Life in Two Cancer Patients. J Palliat Med. 2015 Sep;18(9):807–10. 10.1089/jpm.2014.0357

55. Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Rosati M, Derni S, Fabbri L, Martini F, et al. Palliative sedation in end-of-life care and survival: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Apr;30(12):1378–83. 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.3795

56. Claessens P, Menten J, Schotsmans P, Broeckaert B. Palliative sedation: a review of the research literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008 Sep;36(3):310–33. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.10.004

57. Barathi B, Chandra PS. Palliative Sedation in Advanced Cancer Patients: Does it Shorten Survival Time? - A Systematic Review. Indian J Palliat Care. 2013 Jan;19(1):40–7. 10.4103/0973-1075.110236

58. Kirk TW, Mahon MM; Palliative Sedation Task Force of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Ethics Committee. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) position statement and commentary on the use of palliative sedation in imminently dying terminally ill patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010 May;39(5):914–23. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.01.009

59. Uchida M, Morita T, Akechi T, Yokomichi N, Sakashita A, Hisanaga T, et al.; Phase-R Delirium Study Group. Are common delirium assessment tools appropriate for evaluating delirium at the end of life in cancer patients? Psychooncology. 2020 Nov;29(11):1842–9. 10.1002/pon.5499

60. Gaertner J, Eychmueller S, Leyhe T, Bueche D, Savaskan E, Schlögl M. Benzodiazepines and/or neuroleptics for the treatment of delirium in palliative care?-a critical appraisal of recent randomized controlled trials. Ann Palliat Med. 2019 Sep;8(4):504–15. 10.21037/apm.2019.03.06

61. Vieille M, Dany L, Coz PL, Avon S, Keraval C, Salas S, et al. Perception, Beliefs, and Attitudes Regarding Sedation Practices among Palliative Care Nurses and Physicians: A Qualitative Study. Palliat Med Rep. 2021 May;2(1):160–7. 10.1089/pmr.2021.0022