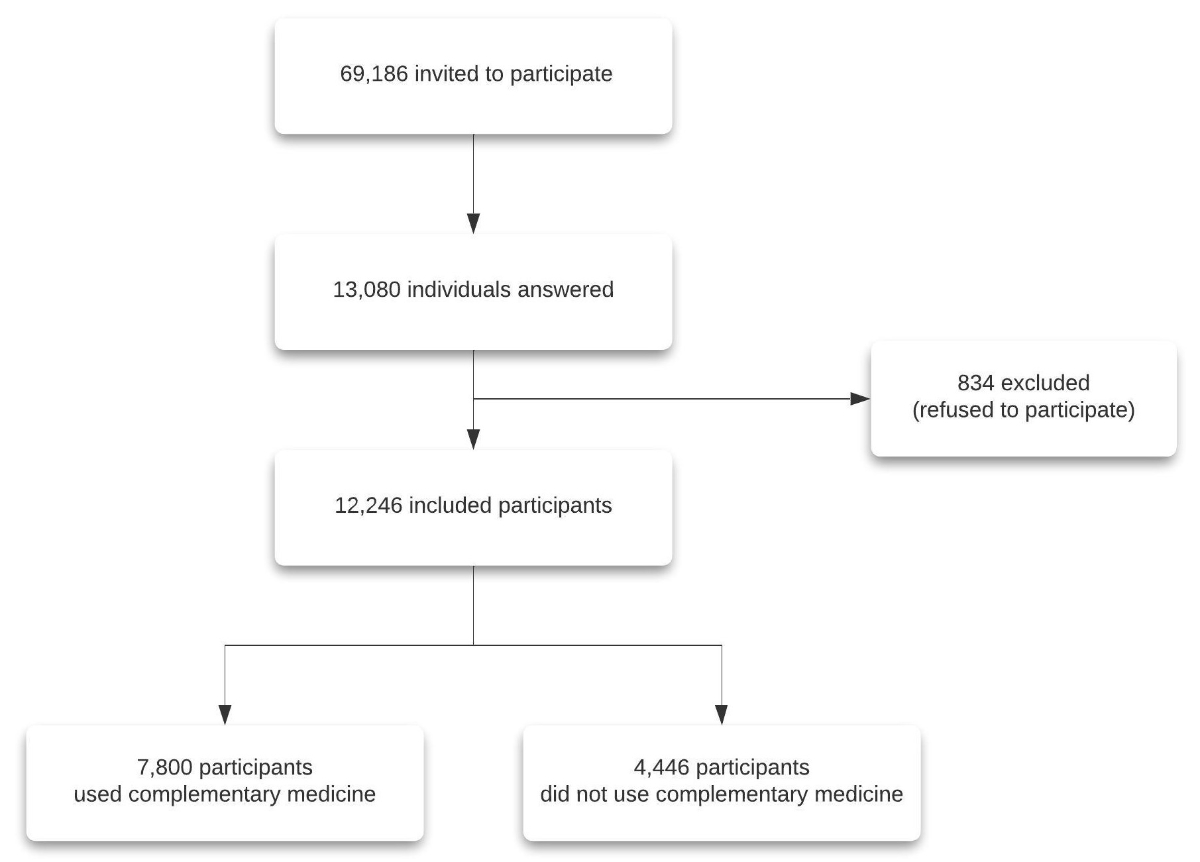

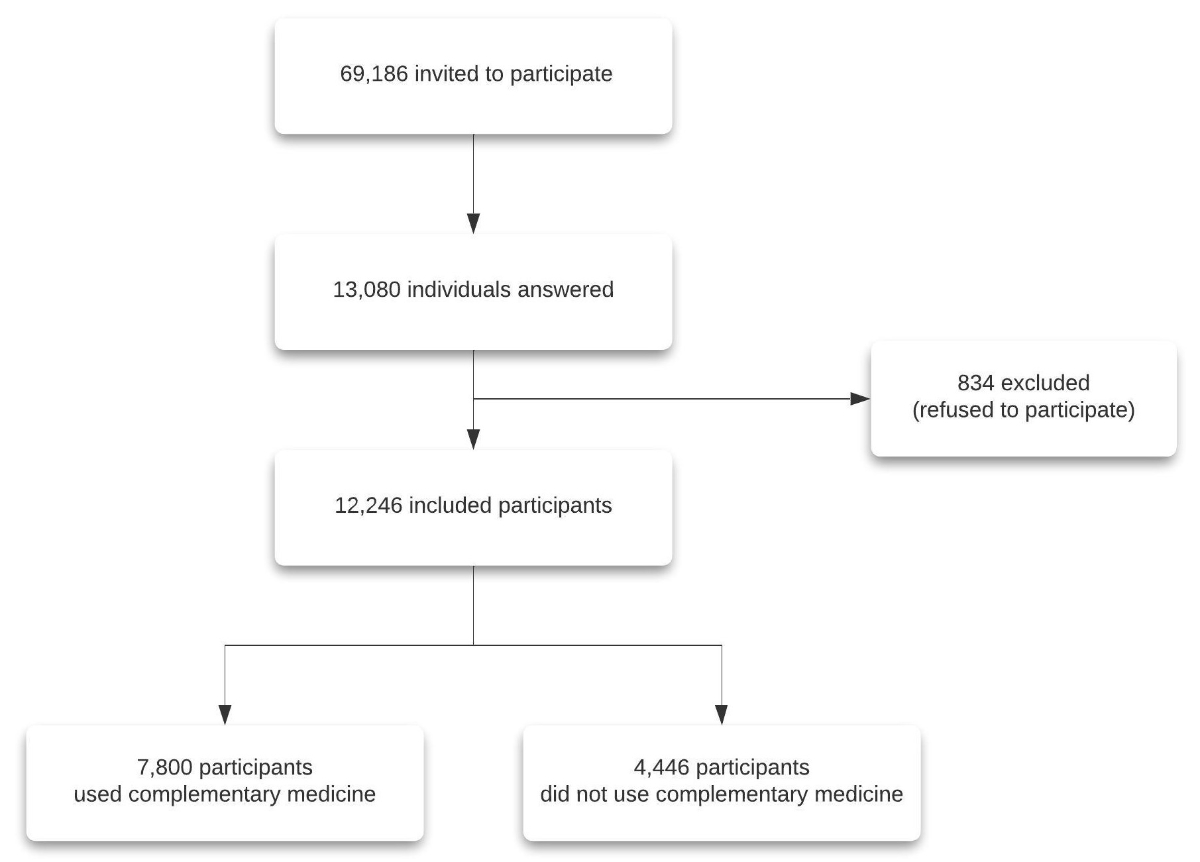

Figure 1Flowchart.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.3505

The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health defines integrative health [1] as combining conventional and complementary approaches in a coordinated manner. Complementary medicine is not typically part of conventional medical care or may have origins outside usual Western practice [1]. Complementary medicine use is widespread in outpatient and inpatient care [2], depending on the approaches considered, and more so in specific diseases such as cancer or other chronic diseases [3–6]. Complementary medicine can complement conventional medicine and be used to treat illnesses, reduce side effects, and maintain well-being [7]. A small proportion of individuals (8% of complementary medicine users in Europe in 2014) used complementary medicine exclusively instead of conventional medicine [8].

Complementary medicine use was shown to be significant during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, depending on the therapies and populations. A recent meta-analysis of 62 studies showed that 64% of individuals used complementary medicine [9], with some statistical heterogeneity that should be explored further. Some low-quality studies limited this meta-analysis. Complementary medicines were used for acute symptomatic treatment [10], as potential prevention approaches [11, 12], and to treat post-COVID-19 symptoms [10, 13]. In Switzerland, a recent study showed that 76% of consultations with traditional Chinese medicine physicians and therapists were related to COVID-19, primarily for recovery from or preventing this disease [14]. Individuals also used complementary medicine approaches to treat long-term health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic and improve overall well-being [15]. Individuals used therapies such as massage, acupuncture, reflexology, self-help practices, homoeopathy, natural remedies, and vitamins and minerals. The use of vitamins and minerals was particularly common, including vitamin B, vitamin C, vitamin D, magnesium, calcium, iron, zinc, and selenium [15].

In general, the use of complementary medicine, nutrition, and supplementation strategies has often been debated in medical approaches. A recent evidence report by the United States Preventive Services Task Force reviewed 84 studies to assess the potential benefits of vitamin use in lowering the incidence of diseases. Vitamin use was associated with little to no benefit in preventing cancer, cardiovascular disease, and death [16]. However, another recent meta-analysis found cardiovascular health benefits with some nutrients [17].

There is little evidence that patients consulted their physicians when using or considering complementary medicine approaches for COVID-19 [18]. Patients could consider these therapies separate from conventional medicine and thus do not feel the need to discuss them with their physicians or potentially consider their physician insufficiently informed or authoritative about them. Patients could also feel some prejudice and refrain from informing their physician about complementary medicine use. Additionally, physicians may not initiate this conversation, potentially leading to misunderstandings or harmful behaviours.

Complementary medicine use is common in individuals with chronic diseases and can be associated with positive health behaviours focusing on well-being [7]. However, in some cases, it can also be associated with rejecting conventional medicine [8], including vaccination. Studies have shown that complementary medicine use was associated with a tendency towards vaccine hesitancy or rejection [19–21], considered more as a conventional medicine approach. Misinformation about COVID-19 vaccination was shown to correlate with vaccine hesitancy [22]. Integrating complementary medicine and improving information are needed to achieve a truly integrative medicine approach. The role of primary care physicians is vital in advising patients on complementary medicine use as a potential adjunct to conventional therapy and not as a substitute.

Vaccination against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been one of the main factors associated with improved outcomes during the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection and related to the post-COVID condition [23]. Vaccination remains one of the most effective preventative measures for decreasing disease or reducing adverse outcomes for individuals and society. Therefore, vaccination status is an important element to consider, especially when dealing with a pandemic. COVID-19 vaccines received much attention, some of which stopped their use. Vaccine hesitancy increased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic due to media-fed controversies about using mRNA-based vaccines, with more than a quarter of the global population reporting being unwilling to be vaccinated against COVID-19 [24]. In Switzerland, vaccine uptake was shown to be multifactorial and influenced by sociodemographic factors [25]. In Geneva, Switzerland, vaccine hesitancy was associated with younger age, female sex, and highly skilled jobs [26]. One question that should be considered is the role of complementary medicine as an alternative to conventional medicine in such contexts and its association with general vaccine uptake.

Therefore, this study evaluated the use and initiation of complementary medicine during the COVID-19 pandemic and its association with vaccination status by age, sex, profession, educational status, SARS-CoV-2 infection, and comorbidities.

Outpatients tested at the Geneva University Hospitals were routinely followed by the CoviCare program, which evaluates symptom persistence, functional capacity, treatment, and healthcare utilisation in individuals positive or negative for SARS-CoV-2 [27]. The CoviCare program has been previously described [27]. Briefly, the CoviCare program follows all participants who tested positive or negative for SARS-CoV-2 at the Geneva University Hospitals (outpatient testing). Initially, only five centres were open for testing in Geneva, Switzerland, during the pandemic, of which the Geneva University Hospitals were the largest, ensuring a higher representativeness of the population. Testing was accessible everywhere in the canton by April 2021, and the representativeness of the general population might have decreased even though the Geneva University Hospitals offered the highest availability of appointments and welcomed the most individuals for testing in the canton. Between April and December 2021, individuals in the general population with a positive or negative COVID-19 reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT PCR) test as outpatients were contacted 12 months after being tested. All participants provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the Cantonal Research Ethics Commission of Geneva, Switzerland (protocol number: 2021-00389).

The follow-up questionnaire was distributed to participants as a personalised link sent via email. It included questions about baseline characteristics, profession, education, comorbidities, vaccination status, the evolution of symptoms since testing, treatment (including a list of pharmacological and non-pharmacological options), healthcare utilisation (hospitalisations and visits to their primary care physician or other specialists), and functional capacity.

Age categories were defined as <40, 40–59, and ≥60 years based on previous studies suggesting that middle age may predict persistent symptoms [28]. Participants were considered unvaccinated if they received no vaccine doses against SARS-CoV-2. Education was categorised as follows: “primary” included compulsory education and no formal education; “apprenticeship” included apprenticeships; “secondary” included secondary school and specialised schools; and “tertiary” included universities, higher professional education, and doctorates. Occupation was categorised as follows: “unskilled workers” were qualified employees practising manual labour, craftsmen, traders, farmers, and employees without specific training; “skilled workers” were qualified employees (non-manual labour); “highly-skilled workers” were employees in a profession requiring intermediate training; “professional managers” were managers in companies with >10 employees or individuals in a profession requiring university training; “independent workers” were individuals who worked as consultants, were independent, or were managers in companies with <10 employees.

Treatment-related questions included chronic treatment over the past 12 months for all participants (not necessarily associated with COVID-19) and acute treatment during the first 10 days after the SARS-CoV-2 test (positive or negative). Therapies were evaluated, including complementary medicine approaches. Complementary medicine use as part of acute and chronic treatment was evaluated and still considered when used in combination with conventional medicine therapies. Complementary medicine approaches included the following therapies: zinc, vitamin D, vitamin C, vitamin B12, selenium, any other vitamins or minerals, or a mix of vitamins/minerals, oligo-elements, probiotics, essential oils, herbal therapy, specific diet, osteopathy, acupuncture, meditation, hypnosis, shiatsu, reflexology, traditional Chinese medicine, and luminotherapy. Participants were asked whether they started treatment before or after a SARS-CoV-2 infection and whether the treatment was associated with COVID-19 prevention or therapy. Participants were also asked whether their symptoms improved due to the treatment using a five-point Likert scale: “Yes”, “Somewhat yes”, “Indifferent”, “Somewhat no”, and “No”. The “Yes/Somewhat yes” and “No/Somewhat no” options were subsequently combined. The survey instrument is available in the appendix, table S1.

Data were collected using REDCap (v11.0.3) and analysed using the Stata statistical software (version 16.0; StataCorp). The data are presented as numbers (percentages) and were compared between groups using the chi-square test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Complementary medicine use was stratified by age, sex, education, profession, and SARS-CoV-2 infection status. Missing data were considered missing at random since the variables considered in the models had few missing data points (all participants had known sex, age, and SARS-CoV-2 infection status; 12,207 participants had known education; and 11,188 participants had known profession). Logistic regression models were used to evaluate associations between COVID-19 vaccination status and the use of complementary medicine and specific therapies such as zinc, vitamin D, or vitamin C supplementation. Multivariable regression models were used to calculate adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI). The aORs were adjusted for age, sex, education, profession, SARS-CoV-2 infection status, and pre-existing comorbidities. Pre-existing comorbidities included being obese or overweight, headache disorders, sleep disorders, hypertension, anxiety, depression, cognitive disorders, respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and chronic pain, including fibromyalgia. Factors for adjustment were chosen based on the distribution of complementary medicine use. A subgroup analysis evaluated the association between COVID-19 vaccination status and the use of complementary medicine and specific therapies such as zinc, vitamin D, or vitamin C supplementation among participants who reported taking them for COVID-19 prevention or treatment. Effect modification was assessed for SARS-CoV-2 infection status as an effect modifier in the association between complementary medicine use and COVID-19 vaccination status.

This study enrolled 12,246 individuals in the follow-up (participation proportion = 17.7%; figure 1). Their mean age was 42.8 (standard deviation [SD] 14.8) years, 59.4% were women, 65.2% had a tertiary education, and half were highly skilled workers or professional managers. Notably, 31.6% of the complementary medicine users and 21.1% of the non-complementary medicine users had complementary insurance. Overall, 26.2% of the participants had at least one positive SARS-CoV-2 test. The mean time from testing to follow-up was 285 (SD 74) days. At the time of follow-up, 82.0% of the participants were vaccinated. Half of the participants had received the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine and half the Moderna COVID-19 (mRNA-1273) vaccine. The participants’ baseline characteristics are shown in table 1.

Figure 1Flowchart.

Table 1Participants’ baseline characteristics (n = 12,246)*.

| Total | Use of complementary medicine | No use of complementary medicine | p-value | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age category (years) | 0.033 | |||

| <40 | 5582 (45.6) | 3488 (44.7) | 2094 (47.1) | |

| 40–59 | 5037 (41.1) | 3269 (41.9) | 1768 (39.8) | |

| ≥60 | 1627 (13.3) | 1044 (13.4) | 583 (13.1) | |

| Sex | <0.001 | |||

| Male | 4968 (40.6) | 2528 (32.4) | 2440 (54.9) | |

| Female | 7278 (59.4) | 5273 (67.6) | 2005 (45.1) | |

| Education (n = 12,207) | <0.001 | |||

| Primary | 529 (4.3) | 253 (3.3) | 276 (6.2) | |

| Apprenticeship | 1229 (10.1) | 690 (8.9) | 539 (12.2) | |

| Secondary | 1712 (14.0) | 1085 (13.9) | 627 (14.2) | |

| Tertiary | 7955 (65.2) | 5275 (67.8) | 2680 (60.6) | |

| Other | 531 (4.3) | 342 (4.4) | 189 (4.3) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 251 (2.1) | 139 (1.8) | 112 (2.5) | |

| Profession (n = 11,188) | <0.001 | |||

| Unskilled workers | 2161 (19.3) | 1397 (19.4) | 764 (19.2) | |

| Skilled workers | 2489 (22.2) | 1757 (24.4) | 732 (18.4) | |

| Highly skilled workers | 3738 (33.4) | 2405 (33.4) | 1333 (33.4) | |

| Professional managers | 1872 (16.7) | 1145 (15.9) | 727 (18.2) | |

| Other | 267 (2.4) | 162 (2.2) | 105 (2.6) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 661 (5.9) | 336 (4.7) | 325 (8.2) | |

| Complementary insurance | 3401 (27.8) | 2464 (31.6) | 937 (21.1) | <0.001 |

| SARS-CoV-2 vaccinated** | 10,123 (82.5) | 6419 (82.0) | 3704 (83.3) | 0.079 |

| SARS-CoV-2 infection | 3237 (26.2) | 2159 (27.5) | 1078 (24.1) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalisation | 1230 (10.0) | 905 (11.5) | 325 (7.3) | <0.001 |

| Due to COVID-19 | 128 (1.0) | 93 (1.2) | 35 (0.8) | 0.035 |

| SARS-CoV-2 reinfection | 158 (1.3) | 123 (1.6) | 35 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Obese or overweight | 1862 (15.1) | 1257 (16.0) | 605 (13.5) | <0.001 |

| Headache disorders | 1603 (13.0) | 1272 (16.2) | 331 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| Sleep disorders | 1609 (13.0) | 1281 (16.3) | 328 (7.3) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1030 (8.3) | 840 (10.7) | 190 (4.2) | 0.001 |

| Anxiety | 1030 (8.3) | 840 (10.7) | 190 (4.2) | <0.001 |

| Cognitive disorders | 801 (6.5) | 653 (8.3) | 148 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 766 (6.2) | 594 (7.6) | 172 (3.8) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory disease | 532 (4.3) | 389 (4.9) | 143 (3.2) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease*** | 291 (2.4) | 208 (2.6) | 83 (1.9) | 0.006 |

| Diabetes | 89 (0.7) | 64 (0.8) | 25 (0.6) | 0.559 |

| Cancer | 89 (0.7) | 64 (0.8) | 25 (0.6) | 0.108 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 42 (0.6) | 33 (0.9) | 9 (0.3) | 0.004 |

| Hypothyroidism | 141 (2.1) | 103 (2.7) | 38 (1.3) | <0.001 |

| Chronic pain, including fibromyalgia | 77 (1.1) | 71 (1.9) | 6 (0.2) | <0.001 |

* Complementary medicine.

** Vaccinated is considered receiving at least one vaccine dose against SARS-CoV-2.

*** Cardiovascular disease excluded hypertension.

Some form of complementary medicine was used by 63.7% of participants: 62.4% for chronic treatment and 17.9% for acute treatment.

In addition, 38.9% of the participants used dietary supplements for chronic treatment within the 12 months before the questionnaire: 14.1% used zinc, 29.9% used vitamin D, and 23.6% used vitamin C. The participants also used therapies such as vitamin B12 (13.8%), a mix of minerals/vitamins (13.5%), selenium (2.5%), essential oils (8.1%), probiotics (8.7%), herbal medicine (7.0%), specific diets (4.4%), homoeopathy (2.5%), traditional Chinese medicine (1.9%), osteopathy (20.7%), acupuncture (8.3%), meditation (8.1%), hypnosis (3.3%), reflexology (3.4%), and luminotherapy (1.1%). Moreover, 17.8% of the participants used dietary supplements for acute treatment within 10 days of testing: 7.1% used zinc, 12.4% used vitamin D, and 13.2% used vitamin C.

Complementary medicine use was higher in women, those aged 40–60 years, those with a higher education level, those who were more highly skilled, those with a prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, and those who had pre-existing comorbidities. Treatment distributions by sex, age, education, profession, and SARS-CoV-2 infection status are described in the appendix, tables S2–S5.

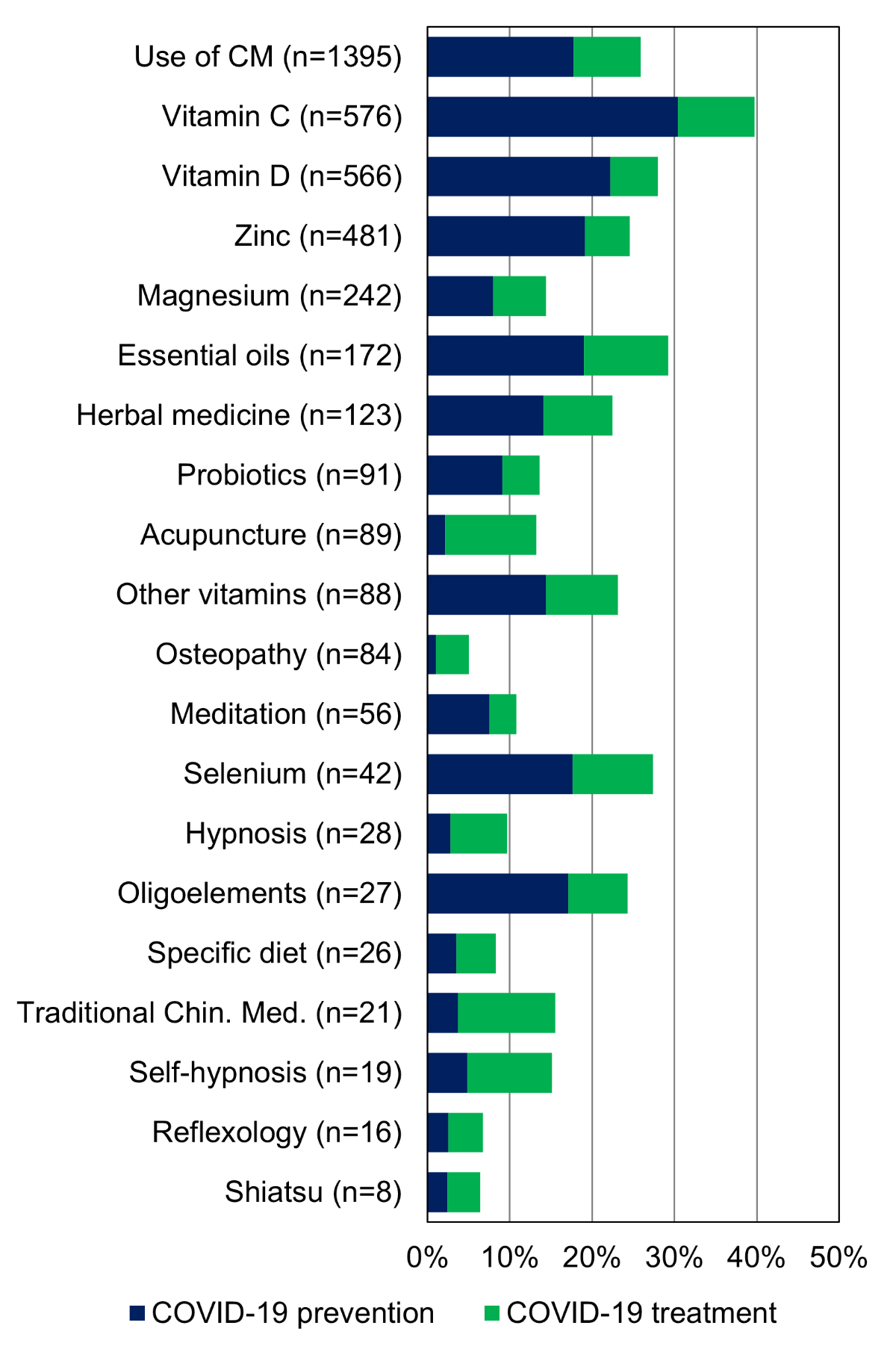

Figure 2 shows the proportion of participants who started complementary medicine therapy specifically for COVID-19 prevention or treatment. Between 10%–30% of participants started the therapy for COVID-19. Almost 25% of participants started zinc for COVID-19 (19.1% for prevention), 30% started vitamin D for COVID-19 (22.4% for prevention), and 40% started vitamin C for COVID-19 (30.4% for prevention). Other treatments initiated to treat or prevent COVID-19 were essential oils, herbal medicine, hypnosis, selenium, and oligo-elements. Most participants reported that the treatment improved their COVID-19 symptoms.

Figure 2The proportion of participants who used complementary medicine (CM) to prevent or treat COVID-19.

Traditional Chin. Med.: Traditional Chinese Medicine

Only 461 (3.8%) participants had discussed complementary medicine therapies with their primary care physician, of which 418 used complementary medicine (5.4% discussed these therapies with their primary care physician), and 43 did not use complementary medicine (1.0% discussed these therapies with their primary care physician).

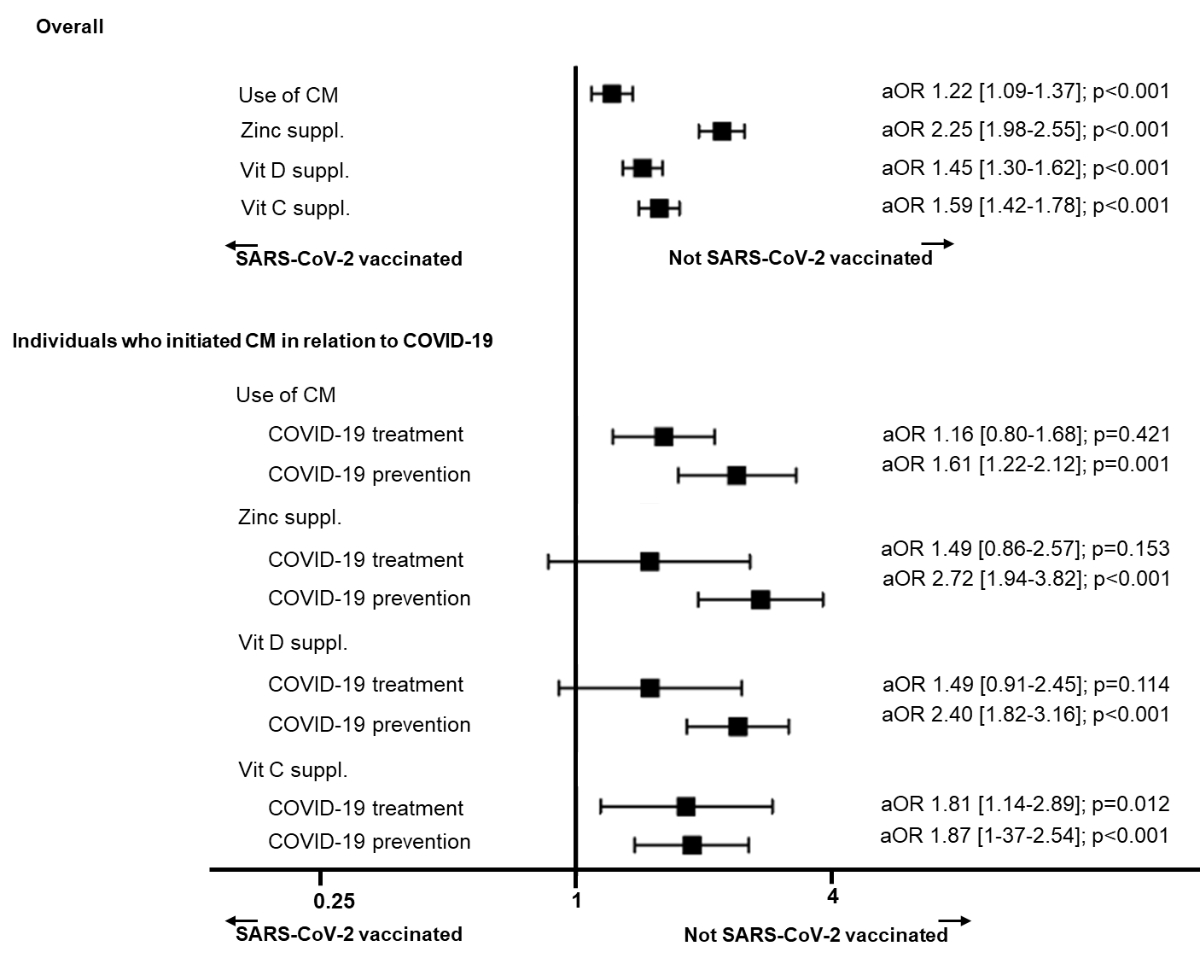

Being unvaccinated was independently associated with general complementary medicine use (aOR 1.22 [1.09–1.37]), zinc use (aOR 2.25 [1.98–2.55]), vitamin D use (aOR 1.45 [1.30–1.62]), and vitamin C use (aOR 1.59 [1.42–1.78]). These associations were significant after adjusting for age, sex, education, profession, SARS-CoV-2 infection status, and pre-existing comorbidities. A subgroup analysis of participants who used complementary medicine therapies for COVID-19 was conducted. In this subgroup, being unvaccinated was strongly associated with using complementary medicine, zinc, vitamin D, or vitamin C for COVID-19 prevention. In addition, being unvaccinated was associated with using complementary medicine or vitamin C but not zinc or vitamin D for COVID-19 treatment. SARS-CoV-2 infection status did not modify the association between complementary medicine use and COVID-19 vaccination. Figure 3 shows the adjusted odds ratios and associations between being unvaccinated and using complementary medicine therapies.

Figure 3Associations between COVID-19 vaccination status and complementary medicine (CM) use with a subgroup analysis of individuals who started CM therapy for COVID-19.

aOR: adjusted odds ratios, adjusted for age, sex, education, profession, SARS-CoV-2 infection, and having persistent symptoms; Suppl: supplementation.

Over two-thirds of participants used complementary medicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. Women, those aged 40–59 years, and those who were highly educated were the most likely to use some of these therapies. Up to a third of participants started these therapies for COVID-19. Notably, using general complementary medicine or zinc, vitamin D and vitamin C supplements was associated with being unvaccinated.

Complementary medicine use doubled during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the 2017 Swiss Health Survey [7], when approximately 28.9% of individuals used complementary medicine. This increase was especially associated with taking vitamins and minerals. However, complementary medicine, excluding vitamins and minerals, was still used by 32.9%, showing an overall increase in the use of these therapies. Complementary medicine therapies are most often used by women, those aged 40–59 years, and highly skilled individuals. Women are more open to complementary medicine [29], and its use has been higher in populations with higher education levels and socio-economic status [29]. These groups might be searching for alternative treatment options and potentially choose to avoid paternalistic approaches in medicine by looking for information and adopting carefully selected therapies [30–32]. In addition, without confirmed treatments (e.g. post-COVID-19), individuals may try unconventional therapies using a precautionary principle.

Almost a third of participants started complementary medicine therapy for COVID-19, especially vitamins or minerals. While most had started the therapies to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection, some also started them as acute or chronic treatment for COVID-19. Studies have shown a mitigated response to the usefulness of these therapies in the acute COVID-19 infection phase [33]. Some studies have shown the benefit of complementary medicine [10], especially in patients with persistent symptoms due to COVID-19 or post-COVID-19 syndrome [13]. However, greater caution is warranted when using it as a preventive measure against COVID-19 alone [34–36] and not adjunct to conventional medicine.

Our results are consistent with studies showing a surge in complementary medicine use during the COVID-19 pandemic [10, 37, 38]. In addition to showing similar results, our study strengthens the body of knowledge on this subject by showing the prevalence of complementary medicine use directly associated with COVID-19 prevention or treatment. This increase in complementary medicine use associated with COVID-19 is potentially driven by the lack of treatment options at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and to improve overall well-being [12].

Our results showed that individuals who used complementary medicine, especially to prevent COVID-19, were less likely to be vaccinated. Notably, the vaccination campaign was launched in Geneva, Switzerland, in December 2020. In May 2021, vaccination was open to all adults regardless of comorbidities or age. To date, 80% of Geneva residents aged 16–64 years and 90% of residents aged ≥65 years have received at least one vaccine dose against COVID-19 [39]. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination has been shown to be highly effective against acute and long-term complications, including the risk of developing post-COVID-19 syndrome [23]. Our study chose to define and evaluate specific dietary supplements, including zinc, vitamin D, and vitamin C, and their association with COVID-19 vaccination status based on published studies and their use during COVID-19. Due to their frequent use during the COVID-19 pandemic, the National Institute of Health issued guidelines and data on the level of evidence (or sometimes the lack thereof) behind the use of zinc, vitamin D, and vitamin C [34–36]. While zinc, vitamin D, and vitamin C might have some immune-modulating or antiviral properties [10–12, 40–42], they should not be considered an either/or approach regarding vaccination. Individuals who would like to adopt complementary medicine should not choose one therapy over another, and an integrative approach is recommended in these cases. Information campaigns on vaccines should consider how to reach and better inform this population. Our results are similar to pre-pandemic studies showing reduced vaccine uptake among individuals who use complementary medicine therapies [19–21, 43–45], both for vaccines in general and specifically for the flu vaccine [20]. These results are more significant now than ever, impacting individual and public health in situations such as pandemics or increased risks of respiratory and other viruses.

Only 3.8% of all participants had discussed complementary medicine use with their primary care physician (5.4% of complementary medicine users and 1.0% of non-complementary medicine users), showing limited communication with physicians. This lack of discussion reduces physicians’ ability to advise individuals for or against specific treatments and integrate them into their overall care. Individuals might then choose one type of medicine over another based on misinformation. Misinformation has been shown to be associated with vaccine hesitancy [22], and the latter is associated with distrust of conventional medicine [44]. Trust in doctors predicted vaccination behaviours and attitudes [43]. Therefore, primary care physicians should initiate the discussion and lead the conversation around vaccination and complementary medicine use [45]. Complementary medicine therapies can have benefits, and participants in our study reported a subjective improvement in their symptoms. Therefore, there is an urgent need to train and provide more knowledge to primary care physicians on complementary medicine in general and vaccine-related topics [46] to improve factual information transfer and general communication. Considering their potential influence on patients’ decisions, complementary medicine practitioners should also be included in vaccination and information campaigns [47].

The limitations of our study included potential reverse causality and indication biases, not knowing whether complementary medicine use was initiated before or after COVID-19 vaccination. These biases were mitigated by adjusting for pre-existing comorbidities and SARS-CoV-2 infection, among other factors. The self-reported nature of the follow-up and the subjective improvement in symptoms limit the general interpretation of our results. The benefits of complementary medicine therapies cannot be confirmed, and efficacy outcomes were not studied. However, participants did report feeling better, which is important in overall well-being. Another limitation was the lack of information on why patients and physicians did not discuss complementary medicine use; this insight could be helpful in the future to improve the conversation between patients and physicians. A further limitation was the classification of occupational status based on training and manual compared to non-manual labour. While this categorisation has its limitations with potential ascertainment bias, it follows the same categorisations used in other cohort studies in Geneva. A final limitation was that the population was mostly educated professionals, with higher response rates from women and individuals answering by email and in French, limiting the generalizability of our results.

The prevalence of using complementary medicine during the COVID-19 pandemic was high, and there was an increased uptake associated with COVID-19 prevention or treatment. Complementary medicine use varied by age, sex, education, and profession. Individuals using complementary medicine, especially for prevention, were less likely to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Despite their high use, there was a lack of communication about complementary medicine therapies with the primary care physician. The role of physicians in advising and helping patients make their choices is important. Further research should explore the potential fears and barriers to communication about complementary medicine use between patients and primary care physicians. After considering all the risks and benefits, choosing complementary medicine can be a shared decision, complementing or integrating with conventional management.

Our data are available to researchers upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, including de-identified participant data or other additional related documents.

Consortium CoviCare Study Team: Mayssam Nehme, Olivia Braillard, Pauline Vetter, Delphine S. Courvoisier, Frederic Assal, Frederic Lador, Lamyae Benzakour, Kim Lauper, Matteo Coen, Ivan Guerreiro, Gilles Allali, Basile N. Landis, Philippe Meyer, Christophe Graf, Jean-Luc Reny, Thomas Agoritsas, Silvia Stringhini, Hervé Spechbach, Frederique Jacquerioz, Julien Salamun, Guido Bondolfi, Dina Zekry, Stéphane Genevay, Nana Kwabena Poku, Marwène Grira, Simon Regard, Camille Genecand, Aglaé Tardin, Laurent Kaiser, François Chappuis, Idris Guessous

Leenaards foundation.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript was disclosed.

1. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. NCCIH. Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s In a Name? https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name [Last updated April 2021].

2. Carruzzo P, Graz B, Rodondi PY, Michaud PA. Offer and use of complementary and alternative medicine in hospitals of the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2013 Sep;143:w13756.

3. Shen J, Andersen R, Albert PS, Wenger N, Glaspy J, Cole M, et al. Use of complementary/alternative therapies by women with advanced-stage breast cancer. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2002 Aug;2(1):8.

4. Richardson MA, Sanders T, Palmer JL, Greisinger A, Singletary SE. Complementary/alternative medicine use in a comprehensive cancer center and the implications for oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2000 Jul;18(13):2505–14.

5. Navo MA, Phan J, Vaughan C, Palmer JL, Michaud L, Jones KL, et al. An assessment of the utilization of complementary and alternative medication in women with gynecologic or breast malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Feb;22(4):671–7.

6. Lee AH, Ingraham SE, Kopp M, Foraida MI, Jazieh AR. The incidence of potential interactions between dietary supplements and prescription medications in cancer patients at a Veterans Administration Hospital. Am J Clin Oncol. 2006 Apr;29(2):178–82.

7. Meier-Girard D, Lüthi E, Rodondi PY, Wolf U. Prevalence, specific and non-specific determinants of complementary medicine use in Switzerland: Data from the 2017 Swiss Health Survey. PLoS One. 2022 Sep;17(9):e0274334.

8. Kemppainen LM, Kemppainen TT, Reippainen JA, Salmenniemi ST, Vuolanto PH. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in Europe: health-related and sociodemographic determinants. Scand J Public Health. 2018 Jun;46(4):448–55. 10.1177/1403494817733869

9. Kim TH, Kang JW, Jeon SR, Ang L, Lee HW, Lee MS. Use of Traditional, Complementary and Integrative Medicine During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 May;9:884573.

10. Jeon SR, Kang JW, Ang L, Lee HW, Lee MS, Kim TH. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) interventions for COVID-19: an overview of systematic reviews. Integr Med Res. 2022 Sep;11(3):100842.

11. Kretchy IA, Boadu JA, Kretchy JP, Agyabeng K, Passah AA, Koduah A, et al. Utilization of complementary and alternative medicine for the prevention of COVID-19 infection in Ghana: A national cross-sectional online survey. Prev Med Rep. 2021 Dec;24:101633.

12. Seifert G, Jeitler M, Stange R, Michalsen A, Cramer H, Brinkhaus B, et al. The Relevance of Complementary and Integrative Medicine in the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Review of the Literature. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020 Dec;7:587749.

13. Kim TH, Jeon SR, Kang JW, Kwon S. Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Long COVID: Scoping Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2022 Aug;2022:7303393.

14. Bourqui A, Rodondi PY, El May E, Dubois J. Practicing traditional Chinese medicine in the COVID-19 pandemic in Switzerland - an exploratory study. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2022 Sep;22(1):240.

15. Kristoffersen AE, Jong MC, Nordberg JH, van der Werf ET, Stub T. Safety and use of complementary and alternative medicine in Norway during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic using an adapted version of the I-CAM-Q; a cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2022 Sep;22(1):234.

16. O’Connor EA, Evans CV, Ivlev I, Rushkin MC, Thomas RG, Martin A, et al. Vitamin and Mineral Supplements for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022 Jun;327(23):2334–47.

17. An P, Wan S, Luo Y, Luo J, Zhang X, Zhou S, et al. Micronutrient Supplementation to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Dec;80(24):2269–85.

18. Parvizi MM, Forouhari S, Shahriarirad R, Shahriarirad S, Bradley RD, Roosta L. Prevalence and associated factors of complementary and integrative medicine use in patients afflicted with COVID-19. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2022 Sep;22(1):251.

19. Attwell K, Ward PR, Meyer SB, Rokkas PJ, Leask J. “Do-it-yourself”: vaccine rejection and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Soc Sci Med. 2018 Jan;196:106–14.

20. Kohl-Heckl WK, Schröter M, Dobos G, Cramer H. Complementary medicine use and flu vaccination - A nationally representative survey of US adults. Vaccine. 2021 Sep;39(39):5635–40.

21. Jones L, Sciamanna C, Lehman E. Are those who use specific complementary and alternative medicine therapies less likely to be immunized? Prev Med. 2010 Mar;50(3):148–54.

22. Neely SR, Eldredge C, Ersing R, Remington C. Vaccine Hesitancy and Exposure to Misinformation: a Survey Analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2022 Jan;37(1):179–87.

23. Antonelli M, Penfold RS, Merino J, Sudre CH, Molteni E, Berry S, Canas LS, Graham MS, Klaser K, Modat M, Murray B, Kerfoot E, Chen L, Deng J, Österdahl MF, Cheetham NJ, Drew DA, Nguyen LH, Pujol JC, Hu C, Selvachandran S, Polidori L, May A, Wolf J, Chan AT, Hammers A, Duncan EL, Spector TD, Ourselin S, Steves CJ. Risk factors and disease profile of post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK users of the COVID Symptom Study app: a prospective, community-based, nested, case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 Sep 1:S1473-3099(21)00460-6. doi: . Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34480857; PMCID: PMC8409907.

24. Lazarus JV, Wyka K, White TM, Picchio CA, Rabin K, Ratzan SC, et al. Revisiting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy around the world using data from 23 countries in 2021. Nat Commun. 2022 Jul;13(1):3801.

25. Heiniger S, Schliek M, Moser A, von Wyl V, Höglinger M. Differences in COVID-19 vaccination uptake in the first 12 months of vaccine availability in Switzerland - a prospective cohort study. Swiss Med Wkly. 2022 Apr;152(1314):w30162. 10.4414/SMW.2022.w30162

26. Nehme M, Baysson H, Pullen N, Wisniak A, Pennacchio F, Zaballa ME, et al.; Specchio-COVID19 study group. Perceptions of vaccination certificates among the general population in Geneva, Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2021 Nov;151(4748):w30079. 10.4414/SMW.2021.w30079

27. Nehme M, Braillard O, Chappuis F, Courvoisier DS, Kaiser L, Soccal PM, et al.; CoviCare Study Team. One-year persistent symptoms and functional impairment in SARS-CoV-2 positive and negative individuals. J Intern Med. 2022 Jul;292(1):103–15. ; Epub ahead of print.

28. Carvalho-Schneider C, Laurent E, Lemaignen A, Beaufils E, Bourbao-Tournois C, Laribi S, et al. Follow-up of adults with noncritical COVID-19 two months after symptom onset. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021 Feb;27(2):258–63.

29. Kristoffersen AE, Stub T, Salamonsen A, Musial F, Hamberg K. Gender differences in prevalence and associations for use of CAM in a large population study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014 Dec;14(1):463.

30. Shen HN, Lin CC, Hoffmann T, Tsai CY, Hou WH, Kuo KN. The relationship between health literacy and perceived shared decision making in patients with breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2019 Feb;102(2):360–6.

31. Meyer SB, Ward PR, Jiwa M. Does prognosis and socioeconomic status impact on trust in physicians? Interviews with patients with coronary disease in South Australia. BMJ Open. 2012 Oct;2(5):e001389.

32. Fjær EL, Landet ER, McNamara CL, Eikemo TA. The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in Europe. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020 Apr;20(1):108.

33. Thomas S, Patel D, Bittel B, Wolski K, Wang Q, Kumar A, et al. Effect of High-Dose Zinc and Ascorbic Acid Supplementation vs Usual Care on Symptom Length and Reduction Among Ambulatory Patients With SARS-CoV-2 Infection: The COVID A to Z Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Feb;4(2):e210369.

34. National Institutes of Health. COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines, Zinc Supplementation and COVID-19. 2021. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/therapies/supplements/zinc/ [Last accessed January, 15, 2023].

35. National Institutes of Health. COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines, Vitamin D. 2021. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/therapies/supplements/vitamin-d/ [Last accessed January 15, 2023].

36. National Institutes of Health. COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines, Vitamin C. 2021. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/therapies/supplements/vitamin-c/ [Last accessed January 15, 2023].

37. Paudyal V, Sun S, Hussain R, Abutaleb MH, Hedima EW. Complementary and alternative medicines use in COVID-19: A global perspective on practice, policy and research. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2022 Mar;18(3):2524–8.

38. Dehghan M, Ghanbari A, Ghaedi Heidari F, Mangolian Shahrbabaki P, Zakeri MA. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in general population during COVID-19 outbreak: A survey in Iran. J Integr Med. 2022 Jan;20(1):45–51.

39. Département de la sécurité, de la population et de la santé (DSPS). COVID-19 : Chiffres et campagne de vaccination à Genève. https://www.ge.ch/document/covid-19-chiffres-campagne-vaccination-geneve. Last updated January 23, 2023.

40. Overbeck S, Rink L, Haase H. Modulating the immune response by oral zinc supplementation: a single approach for multiple diseases. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2008;56(1):15–30. 10.1007/s00005-008-0003-8

41. te Velthuis AJ, van den Worm SH, Sims AC, Baric RS, Snijder EJ, van Hemert MJ. Zn(2+) inhibits coronavirus and arterivirus RNA polymerase activity in vitro and zinc ionophores block the replication of these viruses in cell culture. PLoS Pathog. 2010 Nov;6(11):e1001176. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001176

42. Read SA, Obeid S, Ahlenstiel C, Ahlenstiel G. The Role of Zinc in Antiviral Immunity. Adv Nutr. 2019 Jul;10(4):696–710.

43. Soveri A, Karlsson LC, Mäki O, Antfolk J, Waris O, Karlsson H, et al. Trait reactance and trust in doctors as predictors of vaccination behavior, vaccine attitudes, and use of complementary and alternative medicine in parents of young children. PLoS One. 2020 Jul;15(7):e0236527.

44. Hornsey MJ, Lobera J, Díaz-Catalán C. Vaccine hesitancy is strongly associated with distrust of conventional medicine, and only weakly associated with trust in alternative medicine. Soc Sci Med. 2020 Jun;255:113019.

45. Braillard O, Guessous I, Gaspoz JM. Dialoguer au sujet de la vaccination à l’ère de la post-vérité. Rev Med Suisse. 2017 Sep 27;13(576):1635. French. PMID: 28953331.

46. Lucas Ramanathan P, Baldesberger N, Dietrich LG, Speranza C, Lüthy A, Buhl A, et al. Health Care Professionals’ Interest in Vaccination Training in Switzerland: A Quantitative Survey. Int J Public Health. 2022 Nov;67:1604495.

47. Frawley JE, McKenzie K, Forssman BL, Sullivan E, Wiley K. Exploring complementary medicine practitioners’ attitudes towards the use of an immunization decision aid, and its potential acceptability for use with clients to reduce vaccine related decisional conflict. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021 Feb;17(2):588–91.

The appendix is available in the pdf version of the article at https://doi.org/10.57187/s.3505.