The funding of specialised paediatric palliative care in Switzerland: a conceptualisation

and modified Delphi study on obstacles and priorities

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.3498

Stefan

Mitterera,

Karin

Zimmermannab,

Günther Finkc,

Michael Simona,

Anne-Kathrin

Gerbera,

Eva

Bergsträsserb

a Institute of Nursing Science, Department of Public Health, University

of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

b Paediatric

Palliative Care and Children’s Research Center, University Children’s Hospital

Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

c Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, University of Basel, Basel,

Switzerland

Summary

BACKGROUND: Effective

funding models are key for implementing and sustaining critical care delivery

programmes such as specialised paediatric palliative care (SPPC). In

Switzerland, funding concerns have frequently been raised as primary barriers

to providing SPPC in dedicated settings. However, systematic evidence on

existing models of funding as well as primary challenges faced by stakeholders

remains scarce.

AIMS: The

present study’s first aim was to investigate and conceptualise the funding of

hospital-based consultative SPPC programmes

in Switzerland. Its second aim was to identify obstacles to and priorities for

funding these programmes sustainably.

METHODS: A 4-step process, including a document analysis, was used to conceptualise

the funding of hospital-based consultative SPPC programmes in Switzerland. In

consultation with a purposefully selected panel of experts in the subject, a 3-round

modified Delphi study was conducted to identify funding-relevant obstacles and

priorities regarding SPPC.

RESULTS: Current

funding of hospital-based consultative specialised paediatric palliative care

programmes is complex and fragmented, combining funding from public, private

and charitable sources. Overall, 21 experts participated in the first round of

the modified Delphi study, 19 in round two and 15 in round three. They identified

23 obstacles and 29 priorities. Consensus (>70%) was obtained for 12

obstacles and 22 priorities. The highest level of consensus (>90%) was achieved

for three priorities: the development of financing solutions to ensure

long-term funding of SPPC programmes; the provision of funding and support for

integrated palliative care; and sufficient reimbursement of inpatient service

costs in the context of high-deficit palliative care patients.

CONCLUSION: Decision-

and policy-makers hoping to further develop and expand SPPC in Switzerland should

be aware that current funding models are

highly complex and that SPPC funding is impeded by many obstacles. Considering

the steadily rising prevalence of children with life-limiting conditions and

the proven benefits of SPPC, improvements in funding models are urgently needed

to ensure that the needs of this highly vulnerable population are adequately

met.

Introduction

The prevalence

of children (aged 0–19 years) with life-limiting conditions has been rising steadily

in recent years [1, 2]. Extrapolating from hospital admission data from England

[2], an estimated 11,400 such children currently live in Switzerland. However,

if more comprehensive data from Germany are applied, this number could be as

high as 42,400 [3]. While advances in life-extending medical care and

technology can partially explain the steady increase [4, 5], improvements in

medical coding practice may also have had an effect [2]. Many of these children

and their families can benefit from paediatric palliative care (PPC). Generally,

palliative care aims to improve the quality of life of patients with severe

health-related suffering across all ages, as well as that of their families and

caregivers [6]. As a needs-based approach, PPC includes physical, emotional,

social and spiritual elements that continue throughout the patient’s life and

beyond [6, 7].

Although

new paediatric palliative care programmes have been implemented in recent

years, nationwide access remains limited in Switzerland [8, 9]. Recognising the

complexity of care involved, the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health defines PPC

as

specialised palliative care [10]. Commonly provided by consultative

hospital-based programmes, specialised paediatric palliative care (SPPC) is

delivered in dedicated settings, i.e. the team works exclusively in PPC [11]. Ideally,

these teams are comprised of physicians, nurses, therapists and other

professionals specialised in PPC [11, 12].

Specialised

paediatric palliative care offered within a consultative model of care

contributes to primary care provision and incorporates elements of medical

treatment, care coordination, psychosocial support and other consultative services

[13]. Care and support is offered as and where necessary – both in and out of

hospitals (mobile services such as home visits), through the phases of

palliation, end of life and bereavement to patients, their families, primary

care teams and other healthcare professionals [13]. The level of mobile support

offered varies between programmes, depending on service mandates and available

resources [14]. Additionally, SPPC teams may engage in paediatric palliative

care-related education, training and research [13].

Although

federal healthcare laws and regulations apply [15, 16] and most cantons have

formally recognised the promotion and provision of palliative care [17], specialised

paediatric palliative care is currently much less established than adult palliative

care [8]. In the context of the Swiss healthcare system’s complexity, for which

federal and cantonal bodies assume different tasks, ongoing resource shortages are

likely to challenge the full provision of SPPC. In the Swiss healthcare

system, resources to pay for eligible services, including palliative care, are

collected mostly through compulsory insurance premiums and taxes [18]. In

addition, patients who use insured services are subject to cost-sharing in the

form of deductibles and co-payments [18]. And while patients under the age of

18 are exempt from deductible payments, their families are still liable for co-payments

[19].

Activity-based

funding is the dominant payment method for reimbursing healthcare providers in

Switzerland [18]. While inpatient services are reimbursed via Diagnosis-Related

Group (DRG) payments, outpatient medical services are reimbursed via the tarif

médical (TARMED), a fee-for-service system [18]. Reimbursement of inpatient

costs is subject to cost-sharing between cantons (at least 55%) and health

insurers (at most 45%) [18]. Under certain circumstances, e.g. when a child has

a birth defect, Swiss disability insurance covers part of the related

healthcare expenses [20]: it reimburses 80% of inpatient treatment costs, with

the canton of residence bearing the remaining 20% [21]. Payments for medical

devices and items, laboratory and diagnostic services and medications are

specified in standard fee schedules (i.e. so-called positive lists) [18]. Although reimbursement via standardised

payment systems, e.g. SwissDRG and TARMED, may work well in most healthcare

settings, this is not always the case for hospital-based consultative specialised

paediatric palliative care programmes. Considering the complexity of these

programmes, with care and support provided in various settings and across the

phases of palliation, end of life and bereavement, adequate reimbursement of

related costs may constitute a major challenge.

Information

on models of specialised paediatric palliative care funding and their practical

implementation remains scarce. Even in adult palliative care, few studies

describe such models [22]. The available evidence suggests both that

reimbursement mechanisms tend to undervalue care input and that funding models

are often characterised by a combination of public, private and philanthropic

funding [22]. However, it has been recognised that analyses of payment and

financial strategies based on programme types and funding systems are highly

important to this field’s progress [23]. Therefore, this study’s primary aim

was to develop a conceptual model describing the funding of hospital-based

consultative specialised paediatric palliative care programmes in Switzerland.

Its second aim was to identify obstacles to and priorities for funding these

programmes sustainably.

Materials and methods

In this

study, two separate methodological approaches were employed to address each of

the study’s objectives. First, to develop a conceptual model describing the

funding of hospital-based consultative SPPC programmes in Switzerland, we

followed a 4-step conceptualisation process, including a document analysis.

Second, to identify obstacles and priorities regarding SPPC funding, we

conducted a 3-round modified Delphi study.

Conceptualisation

process

Conceptual models

provide visual illustrations of causal linkages (often visualised as arrows) among

sets of concepts (often visualised as boxes) believed to relate to particular target

points [24, 25]. To conceptualise the funding of hospital-based consultative specialised

paediatric palliative care programmes in Switzerland, we used a 4-step process:

(1) define a target point, (2) choose a conceptual basis, (3) conduct a literature

search and (4) propose a conceptual model [24].

Target point

For this conceptualisation,

we decided to set the focus on hospital-based consultative SPPC programmes, as

they are a common model for providing paediatric palliative care and have been implemented

at several children’s hospitals throughout Switzerland [8, 9].

Conceptual basis

Deber et al.’s

blended service and funding flow model [26] provided the theoretical basis upon

which we conceptualised the funding of hospital-based consultative SPPC

programmes in Switzerland. Their model illustrates the complex relationship

between provider organisations, service providers, service recipients and

third-party payers, all of which are connected by payment and reimbursement

structures [26]. To design our model, we focused on assessing the current

sources of funding, systems of payment and mechanisms of reimbursement in terms

of direct financial flows and funding arrangements.

Document analysis

To explore

and describe the funding of Swiss specialised paediatric palliative care

programmes, we performed a document analysis. Such analyses are widely used in

health policy research to review documents, provide context and supplement

other data types [27]. The aim of the document analysis was to identify funding

sources, payment systems and reimbursement mechanisms and to uncover areas

where challenges to SPPC programmes’ funding are encountered.

Due to the

limited number of specialised paediatric palliative care-specific documents and

the fact that healthcare financing policies do not distinguish between palliative

care for children and adults, we widened our search to include documents on the

funding of palliative care in general. The READ approach (Ready materials;

Extract data; Analyse data; and Distil findings) for document analysis in

health policy research provided the necessary methodology for this document

analysis [28].

Documents

were identified by conducting web searches (Google search engine) for grey

literature, browsing for documents on institutions’ and non-governmental

organisations’ web pages and tracking references. The search was conducted in

German between 6and 20 August 2021 by the first author (SM) and

discussed with two other authors (KZ and EB). Documents about palliative care

funding in Switzerland were included if they reported funding sources, payment

systems and reimbursement mechanisms and/or areas where challenges to that

funding are encountered. To account for the implementation of SwissDRG, documents

had to be published in 2012 or later. Documents reporting solely on the funding

of non-hospital-based palliative care programmes (e.g. geriatric long-term

care, home care agencies) were excluded. Included documents were analysed using

qualitative content analysis [27]. Information was coded, summarised and

tabulated into three predefined categories: funding sources; payment systems

and reimbursement mechanisms; and challenging areas.

Conceptual model

The findings

of the document analysis were used to visualise the funding of hospital-based

consultative specialised paediatric palliative care programmes in Switzerland.

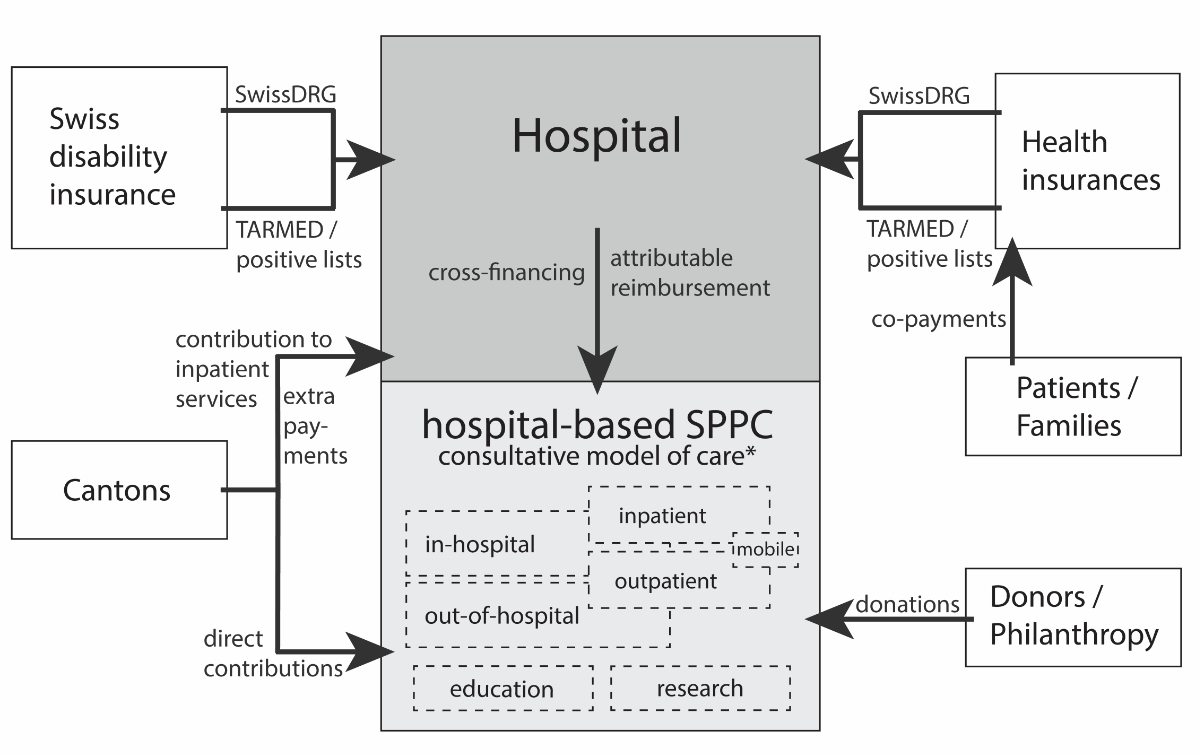

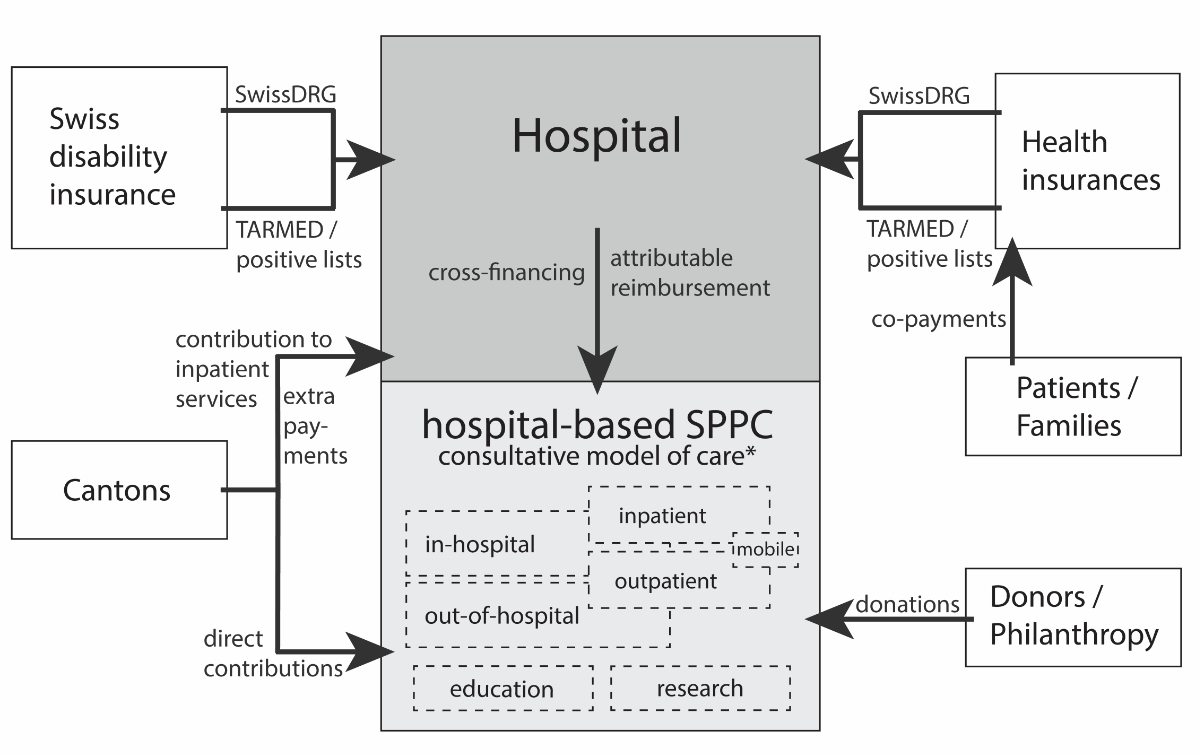

The resulting conceptual model is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1Conceptualisation

of direct financial flows and funding arrangements regarding hospital-based

consultative specialised paediatric palliative care programmes in Switzerland.

* The consultative model of care refers to the provision of medical treatment,

care coordination, psychosocial support and other consultative services that

contribute to primary care provision. Care and support is provided to families,

primary care teams and other professionals in and out of hospitals, i.e.

inpatient, outpatient/mobile services. Specialised paediatric palliative care

teams may engage in paediatric palliative care-related research and education.

Modified Delphi

study

To identify

obstacles and priorities in the funding of Swiss SPPC programmes, we used a 3-round

modified Delphi approach [29]. The Delphi technique is a well-established,

iterative series of steps to survey experts on a particular issue and develop

individual opinions into a group consensus [30–34]. Since its inception in the

1950s, numerous versions of the Delphi technique have been developed, differing

mainly in how consensus was reached or measured [35]. In this study, consensus

was measured by asking participating experts to indicate their agreement or

disagreement with specific statements on a 4-point Likert scale.

Procedures

Before

study start, we purposefully compiled an initial list of experts. We selected potential

participants based on two inclusion criteria: either they had professional

experience in establishing, managing or leading Swiss SPPC programmes (e.g.

programme directors) or they had direct professional knowledge about sources of

funding, payment systems or reimbursement mechanisms related to palliative care

funding in Switzerland (e.g. researchers, health economists, public health

officials, insurance professionals). All eligible experts were first invited via

e-mail to participate in this study, then asked to name two to three other

experts who might also qualify for participation. The modified Delphi study

took place between 23 May and 3 October 2022. Online questionnaires were

provided in German via Google Forms. Reminders were sent towards the end of

each round.

Round one

All experts

who had consented to study participation received a link to an online

questionnaire. This asked them to provide minimal demographic data (i.e.

profession, affiliation) and, using free-text fields, to list and describe

obstacles and priorities regarding SPPC funding. To provide the necessary

context for their responses, challenging areas identified via the document analysis

were provided. In discussion with two study team members (KZ and EB), the first

author (SM) compiled, summarised and merged the expert’s answers into two

lists, one of obstacles, the other of priorities.

Round

two

In round

two, the generated and anonymised lists were sent to everyone who had participated

in round one. Experts were encouraged to comment on identified obstacles and

priorities, as well as specify any more that might have emerged or occurred to

them during the second round. Their answers were again compiled, summarised and

merged. The results were used to update the lists of obstacles and priorities.

Round

three

To measure

consensus, the updated lists were sent to all experts who had participated in the

first two rounds. In the third questionnaire, experts were asked to indicate

their agreement or disagreement with each identified obstacle and priority on a

4-point Likert scale: strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree. In

cases where participating experts did not feel adequately informed on a topic

to indicate agreement or disagreement, they were given the option to answer

“Don’t know”. In addition, each respondent was asked to indicate what they

considered the three most pressing obstacles and the three most urgent priorities.

Data

analysis

Descriptive

statistics (i.e. counts and percentages) were used to provide an overview of

the characteristics of participating experts and to analyse consensus. Analyses

were performed in Microsoft Excel. The thresholds of consensus vary widely between

Delphi studies, with 75% being the median [36]. Considering the diversity of our

participants, we chose a slightly lower cut-off, defining consensus as >70%

agreement (“Strongly agree” and “Agree”).

Ethical

considerations

As no

health-related personal data were collected, the study was not under the

jurisdiction of the Swiss Human Research Act and no ethical approval was

obtained.

Results

Document analysis

and conceptual model

We included

a total of 15 documents in our analysis: 10 reports [8, 9, 14, 16, 17, 37–41],

three technical articles [42–44], one directive [45] and one review [46].

Twelve were obtained through web searches and three by backward reference

tracking. Only two were paediatric-specific; the other 13 focused on palliative

care in general. An overview of included documents is provided as a supplementary

resource (see appendix). Figure 1 shows our conceptual model of hospital-based

consultative specialised paediatric palliative care programme funding in

Switzerland.

Funding sources

Figure 1

illustrates how the Swiss disability insurance fund, health insurance funds,

cantons, donors and philanthropists, patients (i.e. their families) and

hospitals all hold stakes in the funding of hospital-based consultative specialised

paediatric palliative care programmes [8, 9, 14, 16, 17, 41]. Alongside

curative and preventive services, compulsory health insurance covers inpatient

and outpatient palliative care services, at least partially [16]. Depending on

patient characteristics (e.g. age, diagnosis) and service type (e.g. medical

aid, treatment), certain costs are reimbursed (partially) either by the Swiss

disability insurance fund or by health insurers [14, 16].

In addition

to partially reimbursing inpatient service costs and providing financial grants

to service providers (e.g. extra payments, deficit coverage), some cantons

provide direct financial contributions to fund palliative care [8, 9, 14, 16, 17].

In these cantons, special service mandates with hospitals regulate palliative

care provision and related cantonal funding [17]. For instance, the canton of Vaud

commissioned a cantonally funded consultative mobile specialised paediatric

palliative care programme to provide care in various settings, e.g. hospitals,

long-term care institutions, patients’ homes [8, 9, 16].

Very

limited information is reported about payments made by patients or families (in

case of children). Leaving aside their tax payments and insurance premiums,

however, they are also involved in the financing of palliative care services

through their co-payments [14].

For

hospital-based palliative care programmes, hospitals act as both funders and

distributors of funds generated through service provision [41], i.e. payments

made by the Swiss disability insurance fund, health insurance funds and cantons

are collected at the hospital level and distributed under the sovereignty of

the hospital [41]. Our document analysis showed budget deficits of palliative

care programmes had to be either cross-financed by their operating hospitals [37,

46] or covered by donations and philanthropic contributions [8, 17, 37, 46].

Payment systems and reimbursement mechanisms

In terms of

the payment systems and reimbursement mechanisms outlined in figure 1, the reviewed

documents primarily reported on SwissDRG and TARMED. The responsibility for

further developing, adjusting and maintaining the SwissDRG system belongs to SwissDRG

AG, a nonprofit public organisation and joint institution of healthcare

provider associations, health insurers and cantons [42]. Within the National

Strategy for Palliative Care 2010–2015 [40], SwissDRG AG was commissioned to

develop a national tariff structure for reimbursing inpatient palliative care

services [42]. Via a multiyear process, they developed Swiss Classification of

Operations (CHOP) codes for palliative care procedures [16, 41–43, 46]. In this

context, to ensure uniform, high-quality service provision, minimum structural

and personnel requirements were set as performance criteria [16, 41–43]. Only

when these criteria are met can a hospital code and bill for the associated palliative

care procedure codes [41, 42].

Despite

these provisions, analyses showed that certain characteristics of palliative

care patients were not being considered optimally regarding reimbursement [42].

For instance, in terms of length of stay, treatment costs and number of

hospitalisations, palliative care patients differed significantly from other

patients in the same DRGs [42]. Therefore, SwissDRG AG conducted a fundamental

“grouper” restructuring and classified palliative care as a pre-Major

Diagnostic Category [9, 16, 42]. By the end of 2016, palliative care had been

allocated a separate diagnosis group – one independent of the patient’s main

diagnosis, with its own DRG codes (codes A97A–G) – defined in terms of medical

treatment, procedure, length of stay and other criteria [42–44]. Concerns about

adverse incentives regarding inappropriately shortened hospital stays were

addressed by a two-pronged strategy: on the one hand, additional payments were

allowed for extended hospitalisations [45]; on the other, case consolidations

were prevented by recognising readmissions as new, separate hospitalisations [16,

43].

Outpatient

medical palliative care services are reimbursed on a fee-for-service basis via TARMED

[14, 41]. Services listed in this tariff structure are covered by compulsory

healthcare insurance. However, our document analysis suggests that certain palliative

care services, e.g. care coordination and case management, are not fully reimbursable

via TARMED [16, 41]. Alongside TARMED, standard fee schedules – positive lists – regulate

and ensure

the reimbursement of diagnostic and laboratory services, medical devices and

items, medications and other expenses (e.g. therapies) [16]. Our document

analysis also drew our attention to essential palliative care services, including

support and relief for relatives and social counselling, that were not covered

by formal payers [14, 16, 41]. Instead, these services must be financed by

public service contracts, grants, donations or cross-financing [14].

Challenging areas

The reviewed

documents indicate that funding challenges are a major barrier to the implementation,

sustainability and further development of specialised paediatric palliative

care programmes [8, 40]. Difficulties attached to charging for services/covering

costs lead to deficits and funding gaps [8, 9, 17, 46]. Areas where funding challenges

are encountered include both the SwissDRG and the TARMED system [9, 14, 16, 37,

38, 40, 41, 43, 44]. Our document analysis suggests that variations between

cantonal funding regulations hinder the provision of inter-cantonal mobile palliative

care services [17, 37, 40]. In addition, dependencies on external funding (e.g.

donations, philanthropic contributions) pose a risk to long-term financial

stability [17, 41].

Modified Delphi study

Thirty-one

experts were invited for study participation, of whom 22 had been purposefully

identified by the study team and 9 recommended by initially contacted experts. Overall,

21 experts participated in the first Delphi round (68% response rate), 19 in

the second (10% dropout rate) and 15 in the third (21% dropout rate). Demographic

characteristics of the original 21 participating experts are presented in table

1. The participants were mostly female (n = 11, 52%), aged 50–69 years (n = 11,

52%) and working in (university) hospitals, clinics or other healthcare

providers (n = 14, 67%). Ten (48%) worked in medical/clinical professions,

including specialised paediatric palliative care programme leadership.

Table 1Demographic characteristics of participating

experts.

| Characteristics |

Experts, n = 21 |

| Sex, no (%) |

Female |

11 (52%) |

| Male |

10 (48%) |

| Age, no (%) |

30–49 |

10 (48%) |

| 50–69 |

11 (52%) |

| Primary

profession, no (%) |

Medical, clinical, specialised paediatric palliative

care programme leadership |

10

(48%) |

| Health policy, health economics, public health |

5

(24%) |

| Specialist in medical coding, payment systems,

service reimbursement |

4

(19%) |

| Research |

2

(10%) |

| Primary place of employment, no (%) |

(University) hospital, clinic, healthcare provider |

14

(67%) |

| Federal office, (semi-)governmental organisation |

3

(14%) |

| Association

(e.g. hospital / insurance association) |

2

(10%) |

| Other |

2

(10%) |

At the end

of round one, one list each of obstacles (n = 22) and priorities (n = 28)

regarding the funding of specialised paediatric palliative care programmes was

generated. After additional obstacles and priorities suggested in round two, round

three began with lists of 23 obstacles and 29 priorities. Obstacles and priorities

were grouped inductively into six categories: (1) Political and structural, (2)

Funding and tariff structures in general, (3) Inpatient tariff structures, (4) Outpatient

tariff structures, (5) Mobile palliative care and (6) Other. All identified obstacles

and priorities are presented in tables 2 and 3 respectively.

Table 2List of obstacles encountered in the funding of specialised

paediatric palliative care, sorted by category and most-to-least pressing.

| Category |

Obstacles encountered in the funding of specialised paediatric palliative care |

Most-to-least pressing |

| Political and structural |

1. No holistic health policy approach to the financing and funding of palliative care* |

6× |

| 2. Fragmentation of palliative care* funding rendering the establishment and maintenance

of integrated and well-performing treatment pathways more difficult |

4× |

| 3. Lack of guaranteed funding to develop and implement specialised paediatric palliative

care programms |

4× |

| 4. Lack of legal definition of palliative care* (e.g. services, providers and funding

needed to meet patients' palliative care*demand) |

3× |

| 5. Dependency on charitable funding, compromising long-term continuity and sustainability

of specialised paediatric palliative care programmes |

2× |

| 6. Cantonal differences regarding palliative care* service mandates and cost coverage

(e.g. financial contributions, coverage of residual costs) |

1× |

| Funding and tariff structures in general |

7. Gaps in palliative care* funding when patients transition between care settings

(e.g. inpatient, outpatient, home, rehabilitation) |

3× |

| 8. Insufficient compensation, billing limitations and lack of tariffs regarding certain

palliative care* services (e.g. roundtable meetings, case management, care coordination,

support for relatives) |

2× |

| 9. Patient classification and reimbursement difficulties arising from existing tariff

structures that fail to recognise the heterogeneity, multimorbidity and complexity

of the palliative care* population |

– |

| Inpatient tariff structures |

10. Insufficient reimbursement of inpatient service costs in the context of hight-deficit

palliative care* cases or palliative care* patients with complex case constellations

(i.e. high-deficit outliers) |

1× |

| 11. Difficulties in meeting the minimum criteria required for the palliative care

Complex Codes of the Swiss Classification of Operations (CHOPs) |

1× |

| 12. Funding challenges due to gaps between remuneration and hospital operating costs

in view of above-average operating costs, non-optimised processes, low base rates

or gaps in tariff structures |

– |

| Outpatient tariff structures |

13. Lack of palliative care*-specific reimbursement codes in outpatient tariff structures |

2× |

| 14. No reimbursement of bereavement support services or follow-up home visites to

bereaved families and caregivers |

2× |

| 15. Time limitations in the reimbursement of outpatient palliative care* services

(i.e. consultation time limits in TARMED for cases not reimbursed via the Swiss disability,

accident or military social insurance funds) |

– |

| 16. Lack of clarity on whether TARDOC, as a potential successor of TARMED, will improve

palliative care* service reimbursement (TARDOC contains tariff positions for palliative

care services provided by general practitioners and paediatricians) |

– |

| Mobile palliative care |

17. Difficulties in funding mobile palliative care* services, particularly non-direct

patient services (e.g. care coordination, consultations with other healthcare professionals) |

3× |

| Other |

18. Lack of financial support and relief for families and informal caregivers |

3× |

| 19. Challenges to palliative care* service reimbursement in long-term and home-care

settings |

2× |

| 20. Inconsistent definitions of palliative care cases and populations (e.g. neonates,

children, adolescents, adults, elderly) in discussions of funding issues |

1× |

| 21. Lack of educational and training opportunities in specialised paediatric palliative

care |

1× |

| 22. Insufficient evidence on specialised paediatric palliative care's (cost-)effectiveness

in the Swiss setting |

1× |

| 23. Lack of national regulations about the inclusion, status and funding of (paediatric)

hospices |

– |

Table 3List of priorities in the funding of specialised

paediatric palliative care, sorted by category and most-to-least urgent.

| Category |

Priorities in the funding of specialised paediatric palliative care |

Most-to-least urgent |

| Political and structural |

1. Harmonisation of palliative care* regulations (e.g. service mandates, financing)

and closer inter-cantonal cooperation and coordination in palliative care* provision |

5× |

| 2. Funding and support for integrated palliative care* programmes, well-performing

treatment pathways and closer cooperation and coordination among service providers |

4× |

| 3. Development of specific, feasible and viable funding solutions to ensure long-term

funding of specialised paediatric palliative care programmes |

4× |

| 4. Legislative integration of palliative care* into the Swiss Federal Health Insurance

Act (KVG) and the Swiss Health Care Benefits Ordinance (KLV) |

4× |

| 5. Initiation of a nationwide working group (including decision-making bodies) for

securing long-term funding in specialised paediatric palliative care |

3× |

| 6. Provision of financial resources (initial funding, core funding) to establish specialised

paediatric palliative care programmes and facilitate nationwide coverage |

2× |

| 7. Comprehensive analysis of palliative care* demand, supply and funding, including

the identification and disclosure of potential gaps |

2× |

| 8. Establishment of a legal framework for the reimbursement of consultative palliative

care* services |

1× |

| Funding and tariff structures in general |

9. Amendment of palliative care* services (including psychosocial, spiritual services)

as standard benefits in the Swiss Statutory Health Insurance (OKP) scheme |

1× |

| 10. Clarification of open questions regarding the reimbursement of palliative care*

services provided when patients transition between care settings (e.g. inpatient,

outpatient, home, rehabilitation) |

1× |

| 11. Revision, further development and supplementation of services provided in the

patient’s absence in established tariff structures (e.g. interprofessional meetings,

case management, care coordination) |

– |

| 12. A comprehensive, palliative care-specific revision of payment systems and reimbursement

mechanisms to improve palliative care* funding conditions in the medium term |

– |

| 13. A flexible application of tariff rules, explicitly approved by formal payers,

to improve palliative care* funding conditions in the short term (e.g. via analogous

positions)

|

– |

| Inpatient tariff structures |

14. Sufficient reimbursement of inpatient service costs in the context of high-deficit

palliative care* cases or palliative care* patients with complex case constellations

(i.e. high-deficit outliers) |

1× |

| 15. Assuring the quality of data supplied by service providers to SwissDRG AG (when

adequate data becomes available, palliative care* patient and service classification

improvements in inpatient tariff structures can be realised through system maintenance) |

– |

| 16. Broader application of palliative care DRG complex codes through the respective

certification (quality label) of specialised paediatric palliative care programmes |

– |

| 17. Consideration of structural factors not currently considered regarding SwissDRG

at the hospital and patient level in setting base rates |

– |

| Outpatient tariff structures |

18. Sufficient, cost-covering reimbursement of outpatient palliative care* services

(e.g. interprofessional meetings, travel time for home visits) |

2× |

| 19. Reduction of quantity and time limitations in the reimbursement of outpatient

palliative care* services (e.g. reduction of consultation time limits in TARMED) |

2× |

| 20. Introduction of palliative care*-specific counselling and coordination fees in

outpatient tariff structures (i.e. tariff codes for palliative care* case management) |

1× |

| 21. Reimbursement for bereavement support services provided to families and caregivers |

1× |

| Mobile palliative care |

22. Establishment of mobile palliative care* funding regulations in all cantons |

– |

| 23. Funding of mobile palliative care* services based on the area’s palliative care*

demand, not contingent on fluctuating case numbers |

– |

| Other |

24. Establishment of a valid nationwide database on palliative care* provision, in

coordination with the Spitalstationäre Gesundheitsversorgung (SpiGes) project of the Federal Office of Public Health and the Federal Statistical

Office |

4× |

| 25. Financial support/relief for palliative care* patients’ families and informal

caregivers |

3× |

| 26. Development of educational and training opportunities in the field of palliative

care* (including medical curricula) |

2× |

| 27. Facilitation of research on specialised paediatric palliative care's (cost-)effeciveness |

1× |

| 28. Furthering knowledge and understanding of tariff structures to optimise the coding

and billing of palliative care*services |

1× |

| 29. Ensuring cost-covering financing of palliative care* services in non-hospital

settings (e.g. hospices, psychiatric clinics, long-term institutions) |

– |

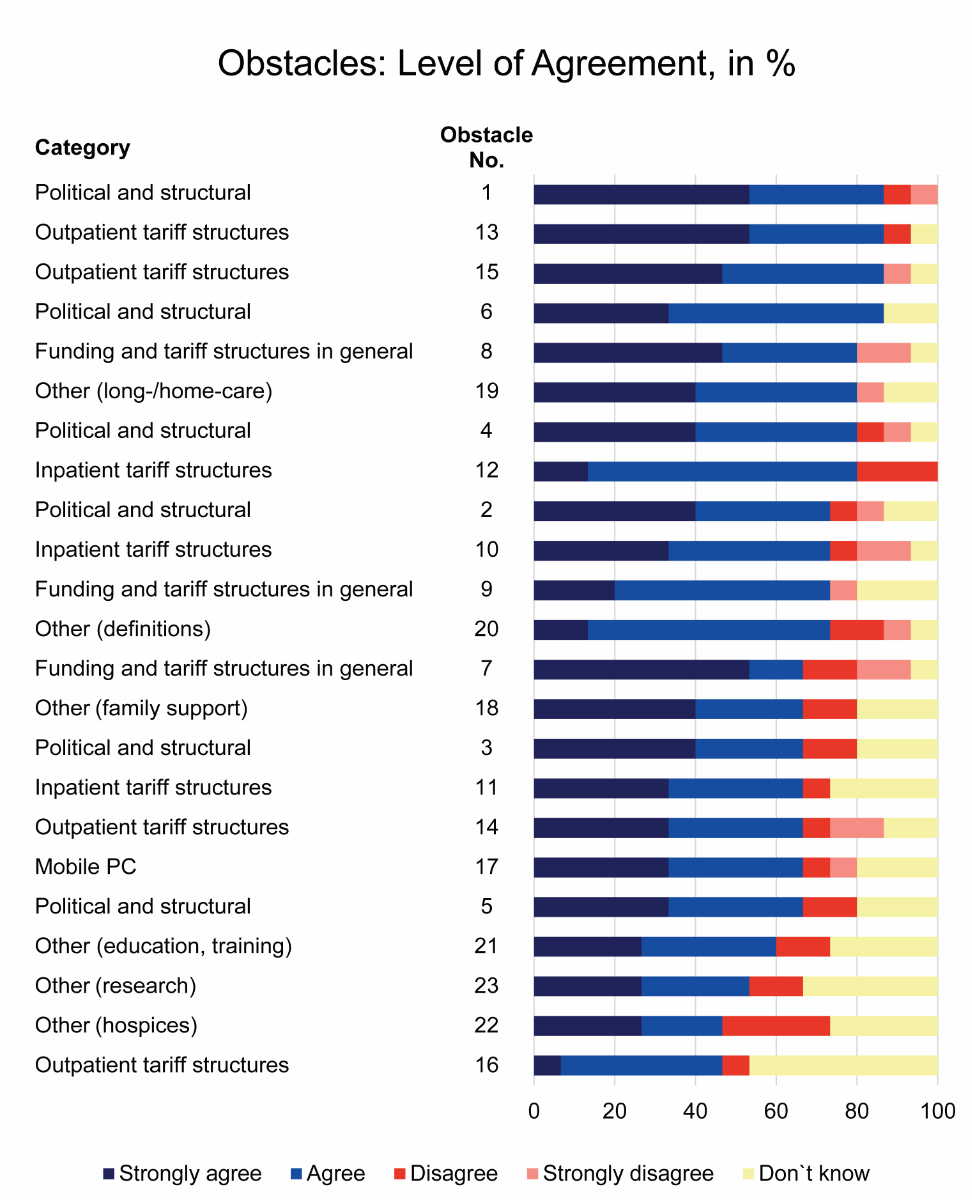

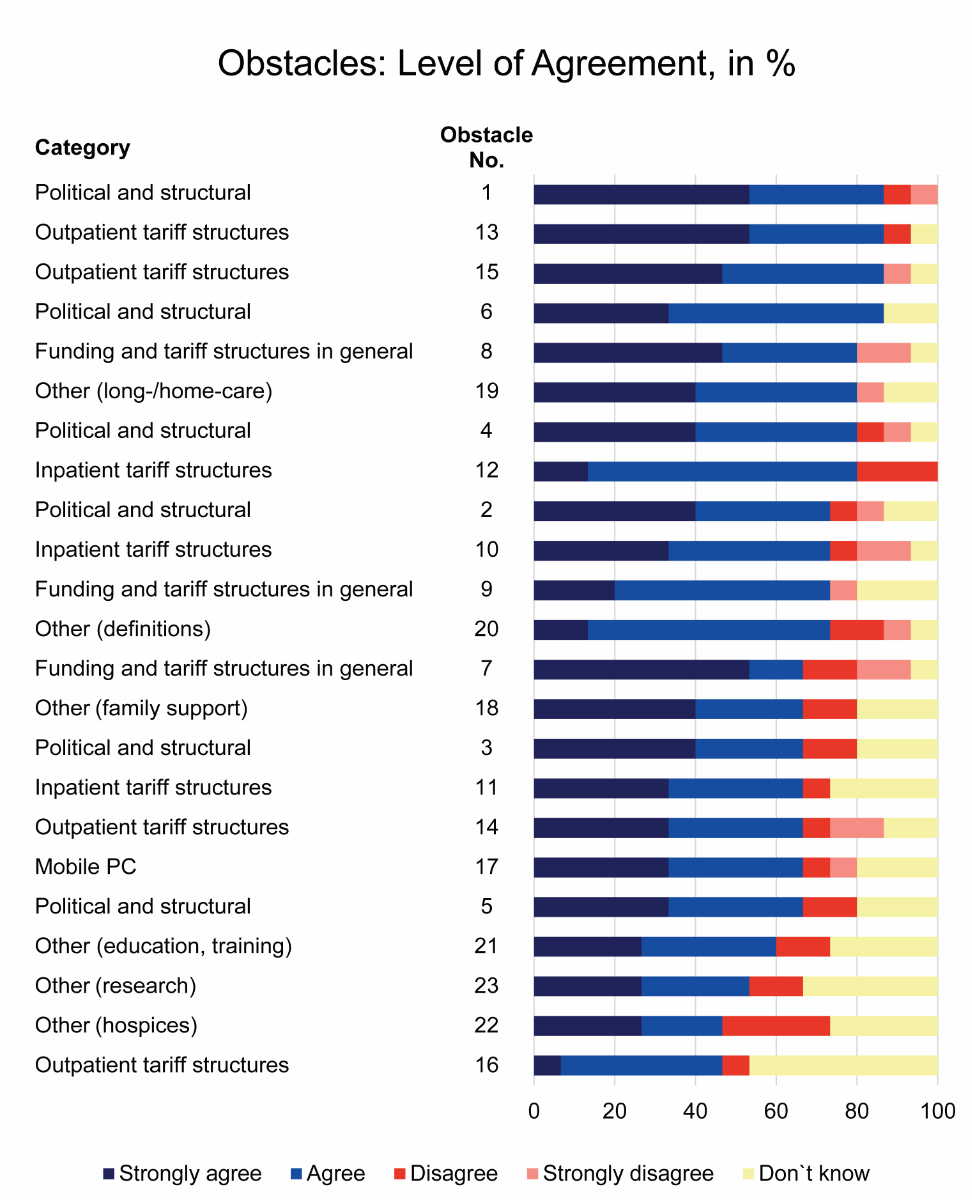

Obstacles

Using our

predefined consensus definition of >70% of experts either strongly agreeing

or agreeing (level of agreement), consensus was obtained on 12 of the 23 identified

obstacles. A level of agreement of >85% was obtained for four obstacles: “Absence

of a holistic health policy approach”, “Cantonal differences in service

mandates and cost coverage”, “Lack of palliative care-specific reimbursement

codes in outpatient tariff structures” and “Existent consultation time

limitations in the reimbursement of certain palliative care outpatient services

in TARMED”. Zero disagreement was recorded regarding difficulties arising from

cantonal differences in palliative care service mandates and cost coverage. The

distribution of the level of agreement of identified obstacles is shown in figure

2.

Figure 2Distribution

of the level of agreement of identified obstacles encountered in specialised

paediatric palliative care funding in Switzerland, sorted by level of

agreement. Obstacle numbers refer to the numbered obstacles provided in table

2. PC: palliative

care.

Asked to

indicate the three most pressing obstacles, participating experts indicated 18

obstacles as most pressing at least once. The obstacle most frequently named – six

times – was “Absence of a holistic health policy approach”. “Fragmentation of palliative

care funding” and “Lack of guaranteed funding for developing and implementing new

specialised paediatric palliative care programmes” were indicated four times each.

Obstacles indicated as one of the most pressing fell predominantly within the

political and structural category (table 2).

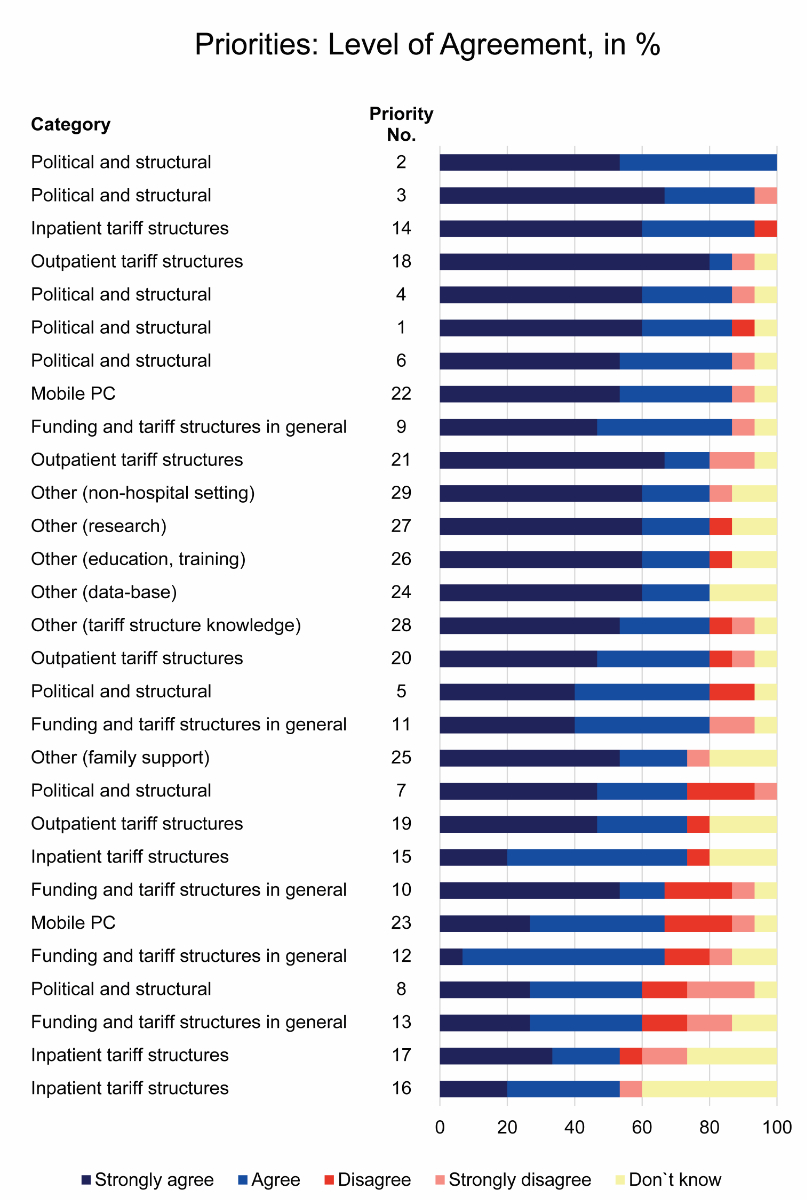

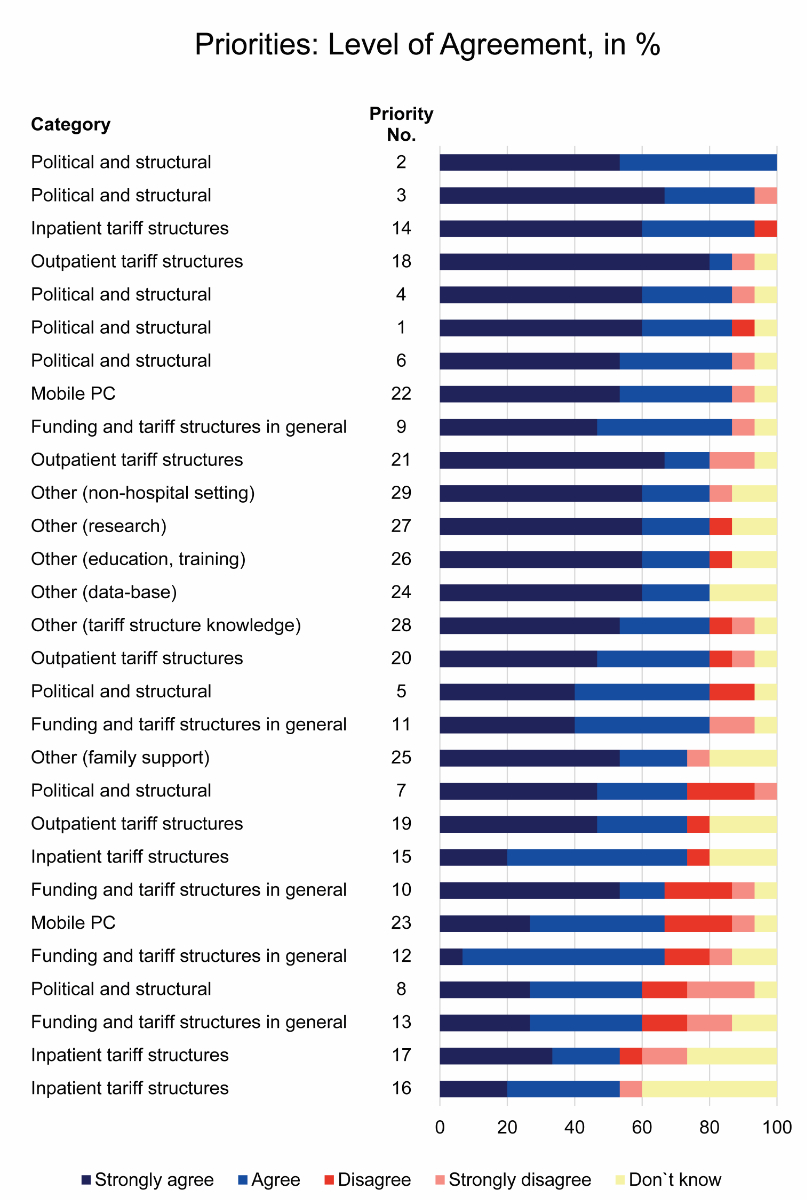

Priorities

A level of

agreement >70% was measured for 22 of the 29 identified priorities. Three priorities

had consensus rates of >90%: “The development of financing solutions to

ensure the long-term funding of specialised paediatric palliative care

programmes”, “The provision of funding and support for integrated palliative

care programmes” and “Sufficient reimbursement of inpatient service costs in

the context of high-deficit palliative care cases”. Zero disagreement was

recorded for two priorities: “Establishing a valid nationwide database on palliative

care provision and offering funding and support for integrated palliative care

programmes, well-performing treatment pathways” and “Closer cooperation and

coordination among service providers”. The distribution of agreement levels of

identified priorities is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3Distribution

of the level of agreement of identified priorities for specialised paediatric

palliative care funding in Switzerland, sorted by level of agreement. Priority

numbers refer to the numbered priorities provided in table 3. PC: palliative

care.

When asked

to indicate what they considered the three most urgent priorities, participating

experts noted a wide range of priorities (n = 20). Most experts’ top priorities

fall within the political and structural category: “Inter-cantonal harmonisation

of palliative care regulations” was indicated five times; “Development of

financing solution to ensure long-term funding of specialised paediatric

palliative care services”, “Legislative integration of palliative care” and “Financing

and support of integrated palliative care programmes” were indicated four times

each. Additionally, experts indicated four times that they considered the

establishment of a valid nationwide database on palliative care provision one

of the most urgent priorities (table 3).

Discussion

Our

conceptualisation of the funding of hospital-based consultative specialised

paediatric palliative care programmes in Switzerland (figure 1) shows that funding

flows and financial arrangements surrounding the provision of SPPC are highly fragmented.

In many cases, donations and philanthropic contributions are required to

supplement funding from formal structures. Several obstacles impede the funding

of SPPC. Overall, our modified Delphi study identified 23 obstacles and 29 priorities

regarding SPPC funding. Consensus was reached on 12 of the obstacles and 22 of

the priorities. The large numbers of both identified obstacles and priorities are

notable, as both lists are samples of issues encountered in the funding of

hospital-based consultative SPPC programmes. The contributing experts considered

many of both lists as very pressing, suggesting that, while no single specific

obstacle or priority emerged as most important, a set of each require urgent

action.

This study’s

findings also bolster the results of a previous investigation on funding models

in palliative care [22]. It was shown that a high degree of fragmentation in

funding sources can increase administrative complexities and create ambiguity

in responsibilities [22]. The fragmentation in funding sources, payment systems

and reimbursement mechanisms has several important implications for the

development, implementation and sustainability of specialised paediatric

palliative care programmes.

First, high

levels of administrative complexity associated with SPPC funding are likely to hinder

the development and implementation of new SPPC programmes and may, at least

partially, explain why nationwide coverage of SPPC has not yet been achieved in

Switzerland [8, 9]. Stable funding, with a streamlined system of payment and

reimbursement, may greatly facilitate the establishment of new programmes [47].

Second,

reliance on annual grants to cover operating costs can actually endanger a

programme’s long-term survival. For example, as both charitable foundations’

and cantonal governments’ budgets can freeze or dry up, dependence on either

can pose serious risks to the long-term sustainability of SPPC programmes.

Third, fragmentation

and complexity in funding of specialised paediatric palliative care programmes may

make it more difficult to estimate how and where funding sources, payment

systems and reimbursement mechanisms act as policy levers. Palliative care

funding has recently become the focus of growing political attention in

Switzerland [41]. In June 2021, parliamentary motion no 20.4264 on palliative

care financing was passed, instructing the Federal Council to establish a statutory

basis to guarantee needs-based palliative and end-of-life treatment and care

for all people [48].

Politically

and structurally, the findings of our modified Delphi study suggest that

further legislative integration and specification regarding palliative care

funding is needed. Parliamentary motion no 20.4264 [48] provides a unique

opportunity to clarify open legal questions. Moreover, participating experts

agreed that a nationwide working group should initiate work on securing

long-term funding for SPPC. When executing parliamentary motion no

20.4264 [48], the Federal Office of Public Health established two dedicated

working groups: one for palliative care supply and demand, the other for palliative

care financing. Ideally, these groups will commission a comprehensive analysis

of SPPC demand, supply and funding. In addition to identifying potential gaps

in SPPC supply, such an analysis would facilitate development of viable

long-term funding solutions.

Additionally,

experts participating in our modified Delphi study agreed that differences in

service mandates and funding regulations among Swiss cantons are an obstacle. Although

most cantons have established legislation to promote palliative care [17], the

details of these measures are rather heterogenous. Therefore, even though tailored

canton-level solutions for specialised paediatric palliative care funding may

provide flexibility in establishing new programmes, local differences may hamper

the provision of inter-cantonal SPPC services (e.g. mobile SPPC teams).

Our

findings also indicate that charitable sources contribute disproportionately to

the current funding of hospital-based consultative specialised paediatric

palliative care programmes in Switzerland: a recent report suggests that donations

and philanthropic contributions cover up to 50% of annual SPPC programme budgets

[8]. In our study, participating experts warned that reliance on donations and

philanthropic contributions compromises long-term continuity and sustainability.

Regarding

inpatient tariff structures, participating experts agreed that, in the context

of high-deficit palliative care cases, i.e. high-deficit outliers, improvements

in the reimbursement of inpatient stay costs are required. Generally, compared

with the total number of hospitalised patients, high-deficit outliers are a

small number of patients that cause a substantial proportion of total inpatient

stay costs [49–51]. Considering that specialised paediatric palliative care cases

are often highly complex [52], high-deficit outliers can be expected to be more

prevalent in this patient population. Sufficient reimbursement of these

patients’ treatment costs should thus be ensured.

Several

obstacles and priorities identified in this study further indicate that certain

palliative care activities are reimbursed insufficiently. These include but are

not limited to care coordination, case management, consultations of other

healthcare professionals and psychosocial and spiritual support. Previous

research suggests that insufficient financing mechanisms constrain access to specialised

paediatric palliative care [53, 54]. This issue is particularly evident in

outpatient palliative care. One identified obstacle is that certain palliative

care services are only partially billable, if at all, via outpatient tariff

structures. Besides the services outlined above, those provided to family

members and other informal caregivers, including psychosocial and bereavement

support, are especially prone to reimbursement failures. Related issues regarding

these services have also been documented previously [14, 16, 38, 41]. Whether

TARDOC, as a potential successor of TARMED, will improve the reimbursement of

outpatient services provided by hospital-based consultative SPPC programmes

remains unclear.

Strengths and

limitations

The

conceptual model developed provides a systemic understanding of how

hospital-based consultative specialised paediatric palliative care programmes are

funded. While informing clinical and administrative leaders regarding the

development and implementation of new SPPC programmes, it serves as a point of

reference regarding funding issues, e.g. how to address them through policies

and regulations. Given that, with high levels of agreement among experts, we

have identified a broad spectrum of obstacles, we believe that our findings accurately

reflect the issues encountered in SPPC funding. Initiatives aiming to improve SPPC

funding models should focus on addressing the priorities identified above.

Several

notable limitations affect this study. First, it was not always possible to

strictly distinguish between specialised paediatric palliative care and overall

palliative care information. Therefore, we included documents on the funding of

both SPPC and palliative care in general in our document analysis. Second, several

experts participating in the modified Delphi study were experts not in SPPC but

in palliative care funding. Third, our approach to conducting the modified

Delphi study precluded us from defining the identified obstacles and priorities

in greater detail. As a result, a number of obstacles and priorities are stated

rather broadly. In addition, as this study aimed to quantify neither funding

flows nor the financial impacts of identified obstacles and priorities, we

recommend both topics as the subjects of further research. Future research may

also explore funding issues in other paediatric palliative care settings, e.g.

home care or children’s hospices.

Conclusion

Current

funding of hospital-based consultative SPPC programmes in Switzerland is highly

fragmented and characterised by a complex combination of public, private and charitable

funding. With new SPPC programmes currently being developed and implemented, a comprehensive

review of current funding structures and actual funding requirements is

urgently needed.

We hope

that the obstacles and priorities identified in this study will help

researchers and policymakers develop funding and reimbursement schemes that

will appropriately support specialised paediatric palliative care provision in

the future.

Data sharing

statement

The data

that support the findings of this study are available on request from the first

author, stefan.mitterer [at]unibas.ch.

Acknowledgments

We warmly

thank all the experts who participated in our modified Delphi study for their

valuable time and expertise. Furthermore, we would like to thank Chris Shultis

for his editorial assistance.

Karin

Zimmermann, PhD, RN

Institute

of Nursing Science

Department

of Public Health

University

of Basel

CH-4000 Basel

karin.zimmermann[at]unibas.ch

References

1. Fraser LK, Miller M, Hain R, Norman P, Aldridge J, McKinney PA, et al. Rising national

prevalence of life-limiting conditions in children in England. Pediatrics. 2012 Apr;129(4):e923–9.

10.1542/peds.2011-2846

2. Fraser LK, Gibson-Smith D, Jarvis S, Norman P, Parslow RC. Estimating the current

and future prevalence of life-limiting conditions in children in England. Palliat

Med. 2021 Oct;35(9):1641–51. 10.1177/0269216320975308

3. Jennessen S, Burgio NM. Erhebung der Prävalenz von Kindern und Jugendlichen mit lebensbedrohlichen

und lebensverkürzenden Erkrankungen in Deutschland (PraeKids). 2022. https://doi.org/10.18452/24740. accessed 08.11.2022. https://edoc.hu-berlin.de/handle/18452/25451

4. Norman P, Fraser L. Prevalence of life-limiting conditions in children and young people

in England: time trends by area type. Health Place. 2014 Mar;26:171–9. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.01.002

5. Nageswaran S, Hurst A, Radulovic A. Unexpected Survivors: Children With Life-Limiting

Conditions of Uncertain Prognosis. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018 Apr;35(4):690–6. 10.1177/1049909117739852

6. Radbruch L, De Lima L, Knaul F, Wenk R, Ali Z, Bhatnaghar S, et al. Redefining Palliative

Care-A New Consensus-Based Definition. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020 Oct;60(4):754–64.

10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.027

7. World Health Organization. Integrating palliative care and symptom relief into paediatrics:

a WHO guide for health-care planners, implementers and managers. 2018. pp. 5–9. [],

https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274561

8. Gesundheitsobservatorium S. Gesundheit in der Schweiz - Kinder, Jugendliche und junge

Erwachsene: Nationaler Gesundheitsbericht 2020. 2020: p. 323. accessed 29.03.2022.

https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home.assetdetail.14147105.html

9. Amstad H. Palliative Care für vulnerable Patientengruppen: Konzept zuhanden der Plattform

Palliative Care des Bundesamtes für Gesundheit. 2020. accessed 14.04.2022. https://www.plattform-palliativecare.ch/arbeiten/zugang-zu-palliative-care-fuer-vulnerable-gruppen-verbessern

10. Bundesamt für Gesundheit und Schweizerische Konferenz der kantonalen Gesundheitsdirektorinnen

und -direktoren, Rahmenkonzept Palliative Care Schweiz. Eine definitorische Grundlage

für die Umsetzung der «Nationalen Strategie Palliative Care». 2014. accessed 09.01.2023.

https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/strategie-und-politik/nationale-gesundheitsstrategien/strategie-palliative-care/grundlagen-zur-strategie-palliative-care/rahmenkonzept-palliative-care.html

11. Benini F, Papadatou D, Bernadá M, Craig F, De Zen L, Downing J, et al. International

Standards for Pediatric Palliative Care: From IMPaCCT to GO-PPaCS. J Pain Symptom

Manage. 2022 May;63(5):e529–43. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.12.031

12. Feudtner C, Womer J, Augustin R, Remke S, Wolfe J, Friebert S, et al. Pediatric palliative

care programs in children’s hospitals: a cross-sectional national survey. Pediatrics.

2013 Dec;132(6):1063–70. 10.1542/peds.2013-1286

13. Bergsträsser E, Abbruzzese R, Marfurt K, and Hošek M, Konzept Pädiatrische Palliative

Care University Children’s Hospital Zurich. 2010. Version 2015. accessed 17.10.2022.

https://docplayer.org/29201365-Konzept-paediatrische-palliative-care-autoren-palliative-care-pd-dr-med-eva-bergstraesser-und-ppc-team.html

14. Wächter M, Bommer A. Mobile Palliative-Care-Dienste in der Schweiz - Eine Bestandsaufnahme

aus der Perspektive dieser Anbieter. 2014. accessed 21.09.2021. https://www.palliative.ch/de/fachbereich/aktuell/grundlagendokumente/

15. Bundesamt für Gesundheit und Schweizerische Konferenz der kantonalen Gesundheitsdirektorinnen

und -direktoren, Nationale Strategie Palliative Care 2010–2012. 2009. accessed 12.01.2022.

https://www.bag.admin.ch/dam/bag/de/dokumente/nat-gesundheitsstrategien/strategie-palliative-care/nationale-strategie-palliative-care-2010-2012.pdf.download.pdf/10_D_Nationale_Strategie_Palliative_Care_2010-2012.pdf

16. Furrer MT, Grünig A, Coppex P. Finanzierung der Palliative-Care-Leistungen der Grundversorgung

und der spezialisierten Palliative Care (ambulante Pflege und Langzeitpflege). 2013.

accessed 06.08.2021. https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/strategie-und-politik/nationale-gesundheitsstrategien/strategie-palliative-care/versorgung-und-finanzierung-in-palliative-care/finanzierung-der-palliative-care.html

17. Liechti L, Künzi K. Stand und Umsetzung von Palliative Care in den Kantonen: Ergebnisse

der Befragung der Kantone und Sektionen von palliative ch 2018. 2019. accessed 06.08.2021.

https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/strategie-und-politik/nationale-gesundheitsstrategien/strategie-palliative-care/grundlagen-zur-strategie-palliative-care/befragung-der-kantone-zu-palliative-care.html

18. De Pietro C, Camenzind P, Sturny I, Crivelli L, Edwards-Garavoglia S, Spranger A,

et al. Switzerland: health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2015;17(4):1–288.

19. Bundesamt für Gesundheit. Health insurance: Co-payment for persons resident in Switzerland. 2020 accessed 14.01.2022; Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/versicherungen/krankenversicherung/krankenversicherung-versicherte-mit-wohnsitz-in-der-schweiz/praemien-kostenbeteiligung/kostenbeteiligung.html

20. Invalidenversicherung, Leistungen der Invalidenversicherung (IV) für Kinder und Jugendliche.

2022. 4.16-22/01-D. accessed 14.01.2022. https://www.ahv-iv.ch/p/4.16.d

21. Bundesgesetz über die Invalidenversicherung. Art. 14 Kostenvergütung für stationäre

Behandlungen. 1959 (01.01.2022). accessed 14.01.2022. https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/1959/827_857_845/de

22. Groeneveld EI, Cassel JB, Bausewein C, Csikós Á, Krajnik M, Ryan K, et al. Funding

models in palliative care: lessons from international experience. Palliat Med. 2017 Apr;31(4):296–305.

10.1177/0269216316689015

23. Feudtner C, Faerber JA, Rosenberg AR, Kobler K, Baker JN, Bowman BA, et al. Prioritization

of Pediatric Palliative Care Field-Advancement Activities in the United States: Results

of a National Survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021 Sep;62(3):593–8. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.01.007

24. Earp JA, Ennett ST. Conceptual models for health education research and practice.

Health Educ Res. 1991 Jun;6(2):163–71. 10.1093/her/6.2.163

25. Brady SS, Brubaker L, Fok CS, Gahagan S, Lewis CE, Lewis J, et al.; Prevention of

Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) Research Consortium. Development of Conceptual

Models to Guide Public Health Research, Practice, and Policy: Synthesizing Traditional

and Contemporary Paradigms. Health Promot Pract. 2020 Jul;21(4):510–24. 10.1177/1524839919890869

26. Deber R, Hollander MJ, Jacobs P. Models of funding and reimbursement in health care:

a conceptual framework. Can Public Adm. 2008;51(3):381–405. 10.1111/j.1754-7121.2008.00030.x

27. Bowen GA. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual Res J. 2009;9(2):27–40.

10.3316/QRJ0902027

28. Dalglish SL, Khalid H, McMahon SA. Document analysis in health policy research: the

READ approach. Health Policy Plan. 2021 Feb;35(10):1424–31. 10.1093/heapol/czaa064

29. Okoli C, Pawlowski SD. The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations

and applications. Inf Manage. 2004;42(1):15–29. 10.1016/j.im.2003.11.002

30. Dalkey N, Helmer O. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of

experts. Manage Sci. 1963;9(3):458–67. 10.1287/mnsc.9.3.458

31. Barrett D, Heale R. What are Delphi studies? Evid Based Nurs. 2020 Jul;23(3):68–9.

10.1136/ebnurs-2020-103303

32. Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique.

J Adv Nurs. 2000 Oct;32(4):1008–15. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.t01-1-01567.x

33. Loughlin KG, Moore LF. Using Delphi to achieve congruent objectives and activities

in a pediatrics department. J Med Educ. 1979 Feb;54(2):101–6. 10.1097/00001888-197902000-00006

34. Whitman NI. The committee meeting alternative. Using the Delphi technique. J Nurs

Adm. 1990;20(7-8):30–6. 10.1097/00005110-199007000-00008

35. McKenna HP. The Delphi technique: a worthwhile research approach for nursing? J Adv

Nurs. 1994 Jun;19(6):1221–5. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01207.x

36. Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, Pencharz PB, Ling SC, Moore AM, et al. Defining

consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi

studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014 Apr;67(4):401–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002

37. Degen E, Liebig B, Reeves E, Schweighoffer R. Palliative Care in der Schweiz. Die

Perspektive der Leistungserbringenden. 2020. accessed 13.08.2021. https://www.palliative.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/palliative/fachwelt/B_Aktuell/200608_Palliative_Care_in_der_Schweiz_-_die_Perspektive_der_Leistungserbringenden.pdf

38. Bundesamt für Gesundheit und Schweizerische Konferenz der kantonalen Gesundheitsdirektorinnen

und -direktoren, Stand und Umsetzung von Palliative Care in den Kantonen Ende 2011.

2012. accessed 21.09.2021. https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/suche.html#kantone%20stand%20umsetzung%20palliative%20care%202012

39. Wyss N, Coppex P. Stand und Umsetzung von Palliative Care in den Kantonen 2013. 2013.

accessed 21.09.2021. https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/suche.html#kantone%20stand%20umsetzung%20palliative%20care%202012

40. Bundesamt für Gesundheit und Schweizerische Konferenz der kantonalen Gesundheitsdirektorinnen

und -direktoren, Nationale Strategie Palliative Care 2013–2015. 2012. accessed 13.08.2021.

https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/strategie-und-politik/nationale-gesundheitsstrategien/strategie-palliative-care.html#-163315092

41. Bundesamt für Gesundheit. Bessere Betreuung und Behandlung von Menschen am Lebensende:

Bericht des Bundesrates in Erfüllung des Postulates 18.3384 der Kommission für soziale

Sicherheit und Gesundheit des Ständerats (SGK-SR) vom 26. April 2018. 2020. accessed

06.08.2021. https://www.bag.admin.ch/dam/bag/de/dokumente/cc/bundesratsberichte/2020/bessere-betreuung-am-lebensende.pdf.download.pdf/200918_Bericht_Po_183384_Lebensende.pdf

42. Franziska S. Das SwissDRG-System und die Finanzierung der palliativmedizinischen Versorgung.

palliative ch - Finanzierung, 2016. 2-2016. accessed 13.08.2021. https://www.palliative.ch/de/fachbereich/zeitschrift/archiv/

43. Gudat H. Ist das Vergütungssystem der SwissDRG AG für spezialisierte Palliative Care

geeignet? Die Pro-Position. palliative ch - Finanzierung, 2016. 02-2016. accessed

13.08.2021. https://www.palliative.ch/de/fachbereich/zeitschrift/archiv/

44. Borasio GD. Ist das Vergütungssystem der SwissDRG AG für spezialisierte Palliative

Care geeignet? Die Kontra-Position. palliative ch - Finanzierung, 2016. 2-2016. accessed

13.08.2021. https://www.palliative.ch/de/fachbereich/zeitschrift/archiv/

45. Swiss DR. Beschluss des Verwaltungsrats der SwissDRG AG: Abbildung der palliativmedizinischen

Behandlung im SwissDRG Tarifsystem. 2016. accessed 13.08.2021. https://www.swissdrg.org/de/ueber-uns/verwaltungsrat/kommunikation

46. Gudat H. Der Wert des Lebensendes: am Beispiel der Finanzierung der stationären spezialisierten

Palliative Care in der Schweiz. Ther Umsch. 2018 Jul;75(2):127–34. 10.1024/0040-5930/a000978

47. Pelant D, McCaffrey T, Beckel J. Development and implementation of a pediatric palliative

care program. J Pediatr Nurs. 2012 Aug;27(4):394–401. 10.1016/j.pedn.2011.06.005

48. Motion 20.4264. Für eine angemessene Finanzierung der Palliative Care. 2020. accessed

13.10.2022. https://www.parlament.ch/de/ratsbetrieb/suche-curia-vista/geschaeft?AffairId=20204264

49. Pirson M, Dramaix M, Leclercq P, Jackson T. Analysis of cost outliers within APR-DRGs

in a Belgian general hospital: two complementary approaches. Health Policy. 2006 Mar;76(1):13–25.

10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.04.008

50. Cots F, Mercadé L, Castells X, Salvador X. Relationship between hospital structural

level and length of stay outliers. Implications for hospital payment systems. Health

Policy. 2004 May;68(2):159–68. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2003.09.004

51. Mehra T, Müller CT, Volbracht J, Seifert B, Moos R. Predictors of High Profit and

High Deficit Outliers under SwissDRG of a Tertiary Care Center. PLoS One. 2015 Oct;10(10):e0140874.

10.1371/journal.pone.0140874

52. Baumann F, Hebert S, Rascher W, Woelfle J, Gravou-Apostolatou C. Clinical Characteristics

of the End-of-Life Phase in Children with Life-Limiting Diseases: Retrospective Study

from a Single Center for Pediatric Palliative Care. Children (Basel). 2021 Jun;8(6):523.

10.3390/children8060523

53. Haines ER, Frost AC, Kane HL, Rokoske FS. Barriers to accessing palliative care for

pediatric patients with cancer: A review of the literature. Cancer. 2018 Jun;124(11):2278–88.

10.1002/cncr.31265

54. Williams-Reade J, Lamson AL, Knight SM, White MB, Ballard SM, Desai PP. Paediatric

palliative care: a review of needs, obstacles and the future. J Nurs Manag. 2015 Jan;23(1):4–14.

10.1111/jonm.12095

Appendix: Overview of included documents

| Type (year) |

Publisher; author(s) |

Title |

Content category |

| Funding sources |

Payment

systems and reimbursement mechanisms |

Areas of challenges |

| Report (2020) |

Swiss Health Observatory; Peter C.,

Diebold M., Delgrande Jordan M., Dratva J., Kickbusch I., Stronski S. |

Gesundheit in der Schweiz – Kinder,

Jugendliche und junge Erwachsene: Nationaler Gesundheitsbericht 2020 [8] |

X |

|

X |

| Report (2020) |

Amstad H. |

Palliative Care für vulnerable

Patientengruppen: Konzept zuhanden der Plattform Palliative Care des

Bundesamtes für Gesundheit [9] |

X |

X |

X |

| Report / Strategy Paper (2012) |

Bundesamt für Gesundheit BAG,

Schweizerische Konferenz der kantonalen Gesundheitsdirektorinnen und

-direktoren GDK |

Nationale Strategie Palliative Care

2013–2015: Bilanz «Nationale Strategie Palliative Care 2010–2012» und

Handlungsbedarf 2013–2015 [40] |

|

|

X |

| Report (2020) |

Bundesamt für Gesundheit BAG |

Bessere Betreuung und Behandlung von

Menschen am Lebensende: Bericht des Bundesrates in Erfüllung des Postulates

18.3384 der Kommission für soziale Sicherheit und Gesundheit des Ständerats

(SGK-SR) [41] |

X |

X |

X |

| Report (2019) |

Bundesamts für Gesundheit; Liechti L.,

Künzi K., Büro für arbeits- und sozialpolitische Studien BASS |

Stand und Umsetzung von Palliative Care

in den Kantonen: Ergebnisse der Befragung der Kantone und Sektionen von

palliative ch 2018 [17] |

X |

|

X |

| Report (2013) |

Bundesamt für Gesundheit BAG,

Schweizerische Konferenz der kantonalen Gesundheitsdirektorinnen und

-direktoren GDK; Furrer M.T., Grünig A., Coppex P. |

Finanzierung der

Palliative-Care-Leistungen der Grundversorgung und der spezialisierten

Palliative Care (ambulante Pflege und Langzeitpflege) [16] |

X |

X |

X |

| Review (2018) |

Gudat H. |

Der Wert des Lebensendes: am Beispiel der

Finanzierung der stationären spezialisierten Palliative Care in der Schweiz [46] |

X |

X |

X |

| Directive (2016) |

SwissDRG AG |

Beschluss des Verwaltungsrats der

SwissDRG AG: Abbildung der palliativmedizinischen Behandlung im SwissDRG

Tarifsystem [45] |

|

X |

|

| Report (2020) |

Degen E., Liebig B., Reeves E.,

Schweighoffer R. |

Palliative Care in der Schweiz: Die

Perspektive der Leistungserbringenden [37] |

X |

X |

X |

| Article (2016) |

palliative ch; Schlägel F. |

Das SwissDRG-System und die Finanzierung

der palliativmedizinischen Versorgung [42] |

|

X |

|

| Article (2016) |

palliative ch; Gudat H. |

Ist das Vergütungssystem der SwissDRG AG

für spezialisierte Palliative Care geeignet? Die Pro-Position [43] |

|

X |

X |

| Article (2016) |

palliative ch; Borasio G.D. |

Ist das Vergütungssystem der SwissDRG AG

für spezialisierte Palliative Care geeignet? Die Kontra-Position [44] |

|

X |

X |

| Report (2014) |

Wächter M., Bommer A. |

Mobile Palliative-Care-Dienste in der

Schweiz - Eine Bestandsaufnahme aus der Perspektive dieser Anbieter [14] |

X |

X |

X |

| Report (2012) |

Bundesamt für Gesundheit BAG,

Schweizerische Konferenz der kantonalen Gesundheitsdirektorinnen und

-direktoren GDK |

Stand und Umsetzung von Palliative Care

in den Kantonen Ende 2011 [38] |

|

|

X |

| Report (2013) |

Bundesamt für Gesundheit BAG,

Schweizerische Konferenz der kantonalen Gesundheitsdirektorinnen und

-direktoren GDK; Wyss N., Coppex P. |

Stand und Umsetzung von Palliative Care in

den Kantonen 2013 [39] |

|

|

X |