Figure 1Annual counts of complementary and integrative medicine-specific DRG A96A and A96B use in Switzerland since 2019.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/smw.2023.40130

On 1 January 2012, Switzerland adopted a nationwide prospective payment system based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) for inpatients in acute somatic care facilities and birth centres. This case-based reimbursement system implies a grouping algorithm to allocate cases to their respective DRGs. The SwissDRG algorithm is built on diagnosis codes in the German Modification of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10-GM); procedure codes in the Swiss Classification of Operations (CHOP); and well-defined patient-related data such as age, sex, and admission type. Each DRG has its resource utilisation score called a cost weight. The fixed amount per case to be billed is thus obtained by multiplying the cost weight by the hospital’s base rate. The latter represents a fixed conversion factor in Swiss franc (CHF) that is usually renegotiated yearly [1].

The Swiss case-based prospective payment system sets incentives for hospitals to treat inpatients cost-efficiently and allows them to compare their performance (benchmarking). The cost weights are nationwide and calculated based on the average costs of inpatients within the same DRG from a previous billing period. However, Mehra et al. highlighted the challenges of achieving robust cost-weight estimates for rare DRGs [2]. Moreover, a fair assessment of medical innovation and new medical services can be costly for providers, who will see reimbursement adjusted to costs only after 2–3 years of processed medico-economic data.

In Switzerland, access to innovative medical services is governed by the Federal Law on Basic Health Insurance (LAMal), which came into force in 1996. New medical services are framed by the “principle of trust”. Therefore, it is assumed that services provided by physicians or hospitals meet the criteria of effectiveness, appropriateness, and efficiency for coverage by the compulsory Swiss health insurance scheme. In case of doubt, a medical service can be challenged by anyone with a legitimate interest [3]. The case of complementary and integrative medicine is one example of a new service introduced into the Swiss healthcare system in 2012 [4] and increasingly adopted by clinics and hospitals, including, more recently, academic centres. However, medical coding and reimbursement are encountering significant difficulties in ensuring harmonious deployment nationwide.

Specific complementary interventions have shown benefits to patients while offering cost-saving opportunities when applied in the hospital care context [5]. Complementary and integrative medicine has been successfully integrated in academic centres and also appears to be of greater utility among patients with serious, chronic, or recurrent illnesses [6]. The first academic centre of its kind in Romandie, the Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), began its clinical activity in the field after a pilot project in the oncology department supported by philanthropic foundations between 2017 and 2019 [7]. Today, the CHUV’s Centre for Integrative and Complementary Medicine (CEMIC) delivers structured, specialised inpatient care to about 500 patients annually.

SwissDRGs specific to complementary and integrative medicine are DRG A96A (complex complementary medicine treatment, without surgical procedure, from 26 treatment sessions) and DRG A96B (complex complementary medicine treatment, without surgical procedure, from 10 treatment sessions). A session is defined as 30 minutes of therapy that includes procedures from the following five areas: anthroposophic medicine, homeopathy, phytotherapy, acupuncture, and Chinese traditional medicine pharmacotherapy [4]. Moreover, therapies must be delivered by a multidisciplinary team with specific qualifications [8].

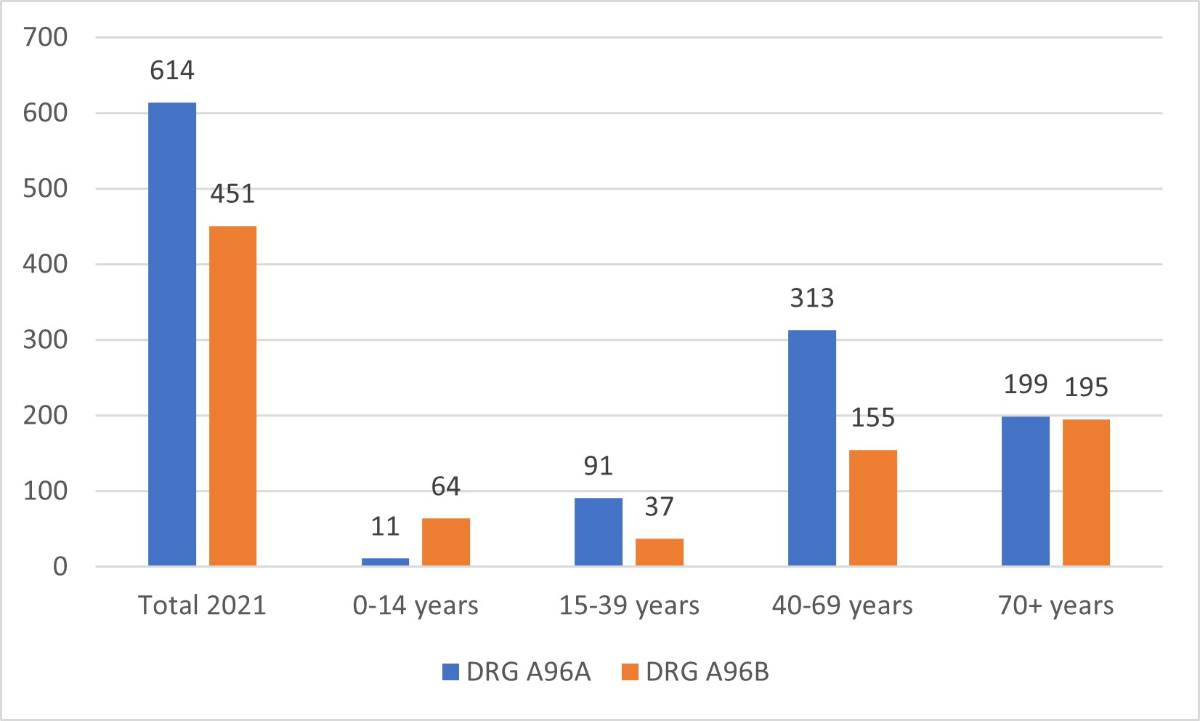

Nationwide, hospitals billed 1,439,968 cases through the SwissDRG prospective payment system in 2021, of which 614 were assigned to DRG A96A (0.04%) and 451 to DRG A96B (0.03%) [9] (figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1Annual counts of complementary and integrative medicine-specific DRG A96A and A96B use in Switzerland since 2019.

Figure 2Counts of complementary and integrative medicine-specific DRG A96A and A96B use by age category in 2021.

The procedure codes related to complementary and integrative medicine services were introduced into the CHOP in 2015. The 2023 revision of the CHOP includes specific codes related to the number of treatment sessions: code 99.BC.11 (up to 9 complex complementary medicine sessions per hospital stay), 99.BC.12 (complex complementary medicine treatment from 10 to 25 sessions per hospital stay), 99.BC.13 (complex complementary medicine treatment from 26 to 49 sessions per hospital stay), and 99.BC.14 (equal or more than 50 sessions complex complementary medicine sessions per hospital stay). Notably, the SwissDRG grouping algorithm never considers the CHOP code 99.BC.11 when classifying a case into a DRG, meaning that a minimum of 10 sessions of complementary and integrative medicine therapies per stay are needed for the service to be relevant to the grouping algorithm.

One task of the SwissDRG grouping algorithm is to classify each case into a Major Diagnostic Category (MDC) based on the case’s primary diagnostic code. However, there are some exceptions where the case is not classified based on its primary diagnostic code but on a particular procedure. In this situation, the case is grouped into a pre-MDC. Pre-MDC DRGs are mainly due to specific procedures driving the costs of the stay (e.g. artificial ventilation for >999 hours). Complementary and integrative medicine-specific DRGs (A96A and A96B) belong to the pre-MDC group and are classified there due to the complementary and integrative medicine CHOP code 99.BC.12, 99.BC.13, or 99.BC.14.

Rodondi et al. [7] reported that barriers to implementing complementary medicine are mainly due to the reimbursement strategy. The SwissDRG algorithm’s classification method is accurate when patients are admitted specifically for complementary and integrative medicine management, such as in a rehabilitation clinic. In this case, the complementary and integrative medicine procedure will cause the case to be classified into DRG A96A or A96B, depending on the number of treatment sessions. However, increasing evidence shows additional benefits when such treatments are implemented as integrative care for more complex patients treated in academic centres for acute/life-threatening illnesses [6].

In 2023, the inlier cost weights for DRG A96A and A96B were 1.526 and 0.956 points, respectively [1]. Therefore, the situation is balanced, provided the case falls into a DRG with a cost weight of less than or equal to this complementary and integrative medicine DRG. Consequently, the costs of the inpatient stay are mainly covered by the reimbursement. However, complex cases may have a cost weight of >5 points and thus be costly for the provider if a complementary and integrative medicine CHOP code is assigned. Deployed in the Oncology Department of the CHUV [7], complementary and integrative medicine is currently dispensed to patients undergoing complex chemotherapy schemes. These patients tend to be classified into the DRG R50B (highly complex chemotherapy) with an inlier cost weight of 6.842 points in 2023. Adding a complementary and integrative medicine CHOP code 99.BC.12 (complex complementary medicine treatment from 10 to 25 sessions per hospital stay) to such a case would classify it into the DRG A96B, which has an inlier cost weight of 0.956. The result is a loss of 5.886 points of cost weight, corresponding to a loss of over CHF 60,000 for the institution for this particular case.

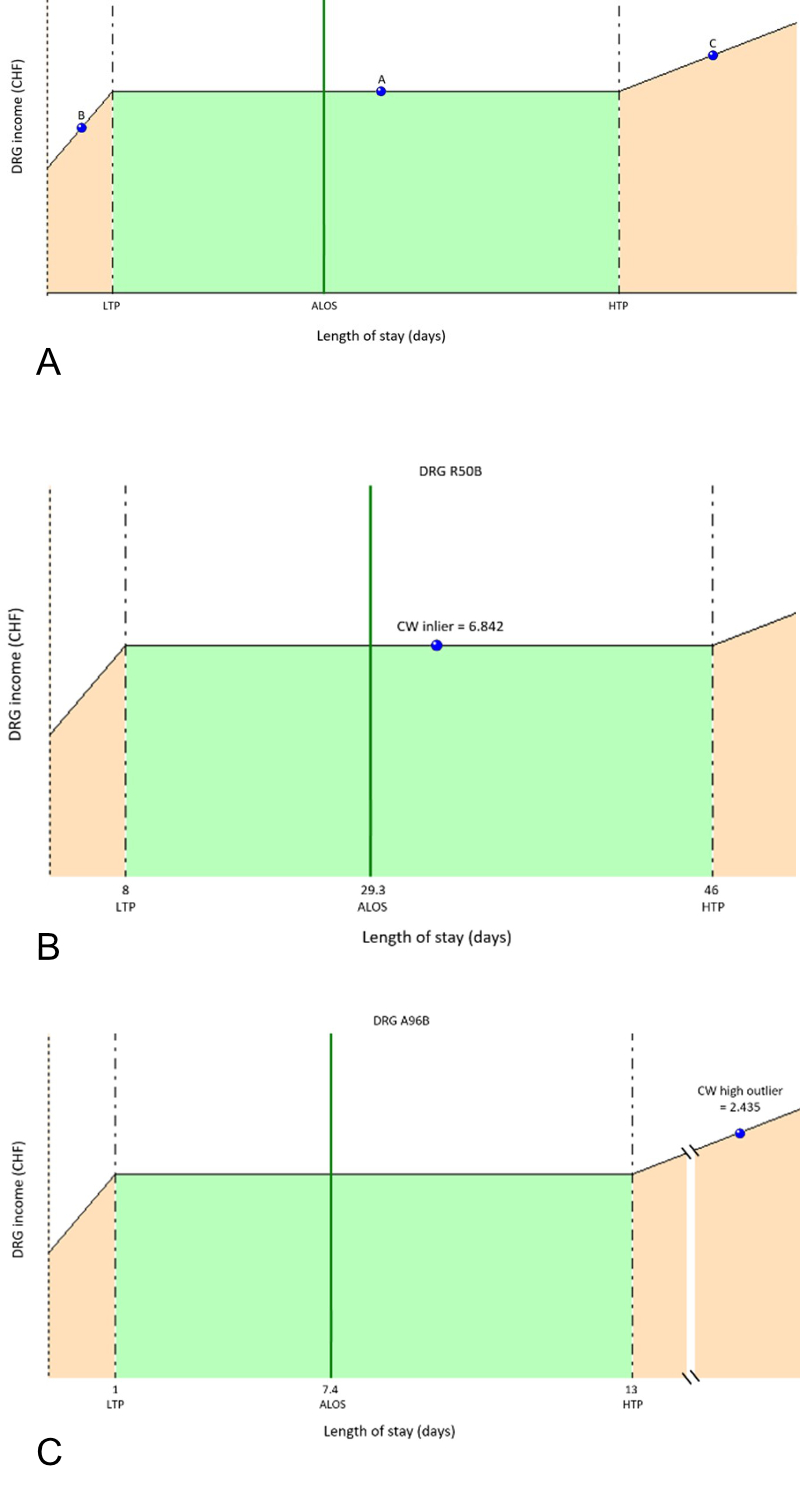

Inlier cases of DRG R50B (highly complex chemotherapy) have an average stay length of 30 days. Therefore, even the high outlier compensation mechanism, triggered from the 13th day for DRG A96B, does not compensate for the loss (figure 3).

Figure 3DRG chart: Inlier and outliers reimbursement. (A) Generally, a case falling in the above DRG chart is inlier for a defined DRG if its length of stay is between the lower (LTP) and upper (HTP) limit set for that DRG.

A: Inlier example: There is no deduction or surcharge on the base amount of the invoice; B: Low outlier example: There is a deduction taken from the base invoice of the considered DRG; C: High outlier example: There is a surcharge to be added to the basic invoice sent to the payer. ALOS: average length of stay.

(B and C) From SwissDRG R50B inlier to DRG A96B high outlier: A case falling in DRG R50B (complex chemotherapy) with a length of stay of 30 days and an inlier CW of 6.842 (B) is converted into DRG A96B by the SwissDRG grouping algorithm when the complementary and integrative medicine CHOP code 99.BC.12 is added (C). The cost weight supplement beginning on the 13th day corresponds to 0.087 points per day (0.087 × 17 days with supplement until the 30th day = 1.479). Therefore, the high outlier cost weight of DRG A96B for a stay of 30 days is 2.435 (0.956 + 1.479). The high outlier supplement mechanism does not compensate for the situation by more than 4 cost weight points or CHF 47,000.

Under normal circumstances, cost weight represents the costs incurred by providers, so going from a cost weight of 6 to a cost weight close to 1 means dividing the assessment of costs by a factor of 6. This change makes complementary and integrative medicine services prohibitively expensive for many complex and severe cases without a support fund.

There are many possible consequences at this stage. First, there is a risk of unequal access to complementary and integrative medicine therapies supported by evidence-based medicine. Second, since the CHOP code is prohibitively expensive in some cases, the interpretation of Swiss medical statistics could be skewed if hospitals providing these services do not enter the specific complementary and integrative medicine CHOP code. Finally, adjusting DRG A96A and A96B cost weights to the costs transmitted by hospitals will be unable to reflect reality in the long run since the costs transmitted by providers will not be associated with the services provided.

Cases with a surgical procedure code and those falling into MDC 14 (pregnancy, birth, and post-natal care) are already excluded from grouping based on a complementary and integrative medicine CHOP code.Therefore, the proposal at this stage would be to extend the exclusion to all DRGs with a cost weight greater than the A96 code. This approach would not affect the current fair reimbursement of cases deserving a cost weight from the DRGs dedicated to complementary and integrative medicine services. However, it would stop the drastic cost-weight reduction related to complex cases. All hospitals motivated to invest time and resources in delivering and justifying their complementary and integrative medicine services will be able to do so at their discretion. Finally, the costs transmitted by these hospitals will help define a fair reimbursement strategy in the future.

Lastly, administering <10 sessions during a stay does not yet influence the DRG assigned by the grouping algorithm. However, this does not imply that ≤9 sessions are not beneficial [10]. In such cases, verifying that the incentive is appropriate is important. In other words, the cost of complementary and integrative medicine therapies is compensated by the reduced costs related to a shorter stay length or less drug consumption.

A prospective payment system such as the SwissDRG system sets incentives for hospitals to treat patients cost-efficiently. Adverse economic incentives threatening patient care and the development of new and established therapeutic strategies with cost-saving potential must be avoided. Therefore, it is vital to monitor and respond quickly to these threats.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript was disclosed.

1. Swiss DRG. Les forfaits par cas dans les hôpitaux suisses. https://www.swissdrg.org/fr (accessed June 7, 2023).

2. Mehra T, Müller CT, Volbracht J, Seifert B, Moos R. Predictors of high profit and high deficit outliers under SwissDRG of a tertiary care center. PLoS One. 2015 Oct;10(10):e0140874.

3. Med TR. (MTRC) Report. Innovative payment schemes for medical technologies and in-vitro diagnostic tests in Europe. June 2018. https://www.medtecheurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/2018_MTE_MTRC-Research-Paper-Innovative-Payment-Schemes-in-Europe.PDF (accessed June 26, 2023).

4. Quelles prestations des médecines complémentaires pratiquées par des médecins sont prises en charge par l’assurance obligatoire des soins (AOS)? OFSP. https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/fr/home/versicherungen/krankenversicherung/krankenversicherung-leistungen-tarife/Aerztliche-Leistungen-in-der-Krankenversicherung/Aerztliche-Komplementaermedizin.html (accessed June 26, 2023)

5. Dusek JA, Griffin KH, Finch MD, Rivard RL, Watson D. Cost savings from reducing pain through the delivery of integrative medicine program to hospitalized patients. J Altern Complement Med. 2018 Jun;24(6):557–63.

6. Vohra S, Feldman K, Johnston B, Waters K, Boon H. Integrating complementary and alternative medicine into academic medical centers: experience and perceptions of nine leading centers in North America. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005 Dec;5(1):78.

7. Rodondi PY, Lüthi E, Dubois J, Roy E, Burnand B, Grass G. Complementary medicine provision in an academic hospital: evaluation and structuring project. J Altern Complement Med. 2019 Jun;25(6):606–12.

8. Classification suisse des interventions chirurgicales (CHOP). Index systématique – Version 2023, p.424. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/sante/nomenclatures/medkk/instruments-codage-medical.assetdetail.23085960.html (accessed June 2023)

9. Office fédéral de la statistique OFS. Statistique médicale des hôpitaux : nombre de cas par classe d’âge, selon la classification par groupes de patients SwissDRG. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home.assetdetail.23727896.html (accessed December 23, 2022).

10. Wu MS, Chen KH, Chen IF, Huang SK, Tzeng PC, Yeh ML, et al. The efficacy of acupuncture in post-operative pain management: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016 Mar;11(3):e0150367.