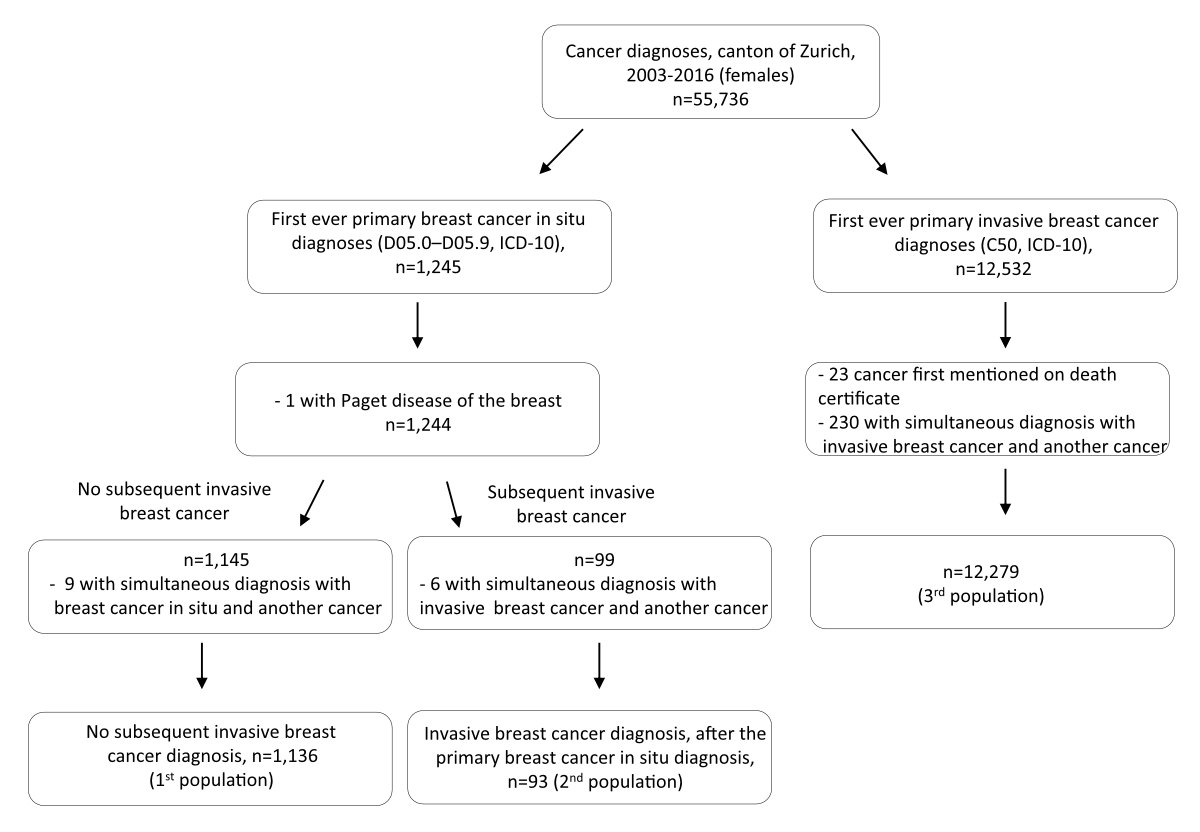

Figure 1Schematic representation of the populations used in the study.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/smw.2023.40087

Breast carcinoma in situ is a heterogeneous group of intraepithelial lesions that have malignant potential. Most studies in the existing literature consider breast carcinoma in situ either a non-obligatory precursor or a potential risk factor for invasive breast cancer, depending on the morphological subtype studied. The majority of in situ breast tumours are detected via mammography, given that breast carcinoma in situ patients seldom report symptoms before their diagnosis [1].

The natural course of breast carcinoma in situ and the prognosis of breast carcinoma in situ patients have not been extensively investigated [2, 3]. The existing literature suggests that the incidence of breast carcinoma in situ is increasing worldwide [4–6] and women with breast carcinoma in situ are at a higher risk of developing a subsequent invasive breast and possibly non-breast cancer compared to the general population [7–12]. However, good survival outcomes are reported for breast carcinoma in situ patients, who do not have higher mortality from breast cancer than the general population [7, 13–15].

One of the main difficulties in reporting cancer-specific survival outcomes, whether using population-based data (e.g. cancer registries) or other types of data, is that the cause of death needs to be identified and correctly classified as cancer-specific or not. Due to the considerable uncertainty in distinguishing between the two, the cause of death may be misidentified or misclassified and therefore inaccurate [16–20]. Estimating survival within a relative survival framework is one way of overcoming this difficulty, since it does not rely on information on cause of death.

We aimed to investigate the differences between invasive breast tumour characteristics, based on whether or not the patients had a previous, recorded breast carcinoma in situ diagnosis. Furthermore, we estimated and compared the net survival of patients diagnosed with different breast tumours (breast carcinoma in situ, invasive cancer, or breast carcinoma in situ and then invasive cancer) using a relative survival framework.

Data were obtained from the cancer registry of each of the cantons of Zurich, Zug, Schaffhausen and Schwyz. Given that the registries of the cantons of Zug, Schaffhausen and Schwyz became operational much later (2011 and 2020), only data from the canton of Zurich were used. To be included in the study, women had to be living in the canton of Zurich at the time of diagnosis, even if they were being treated in another canton. Compulsory reporting to the cantonal cancer registry was approved by the Zurich Government Council in 1980; a national law on compulsory reporting came into effect in 2020. The cancer registry receives cancer-related notifications from laboratories, hospitals and physicians as well as death certificates from the Swiss Federal Statistical Office. All women included in our study were diagnosed with cancer between 2003 and 2016, and the latest possible date of follow-up was 31 December 2017.

A schematic presentation of the study populations is shown in figure 1. The first population of interest included women whose first ever cancer diagnosis was primary breast carcinoma in situ (D05.0 to D05.9 in International Classification of Diseases 10th edition [ICD-10]) who did not develop primary invasive breast cancer (C50 in ICD-10) during the study period (2003–2016; n = 1136). From this population of interest were excluded: women diagnosed with another type of cancer before breast carcinoma in situ; women diagnosed with Paget disease of the breast; and women in whom another cancer (including invasive breast cancer) was diagnosed at the same time as breast carcinoma in situ (i.e. with the same cancer incidence date). The first study population consisted of women who did not develop primary invasive breast cancer (C50 in ICD-10) during the study period. Women with primary breast carcinoma in situ who met the aforementioned inclusion criteria and who later, during the study period, developed primary invasive breast cancer were considered the second population of interest (n = 93).

The third population of interest consisted of women whose first ever cancer diagnosis was invasive breast cancer (C50 in ICD-10) diagnosed between 2003 and 2016 (n = 12,279). From this population of interest were excluded: women diagnosed with another type of cancer before the invasive breast cancer; women for whom invasive breast cancer was first mentioned in their death certificate; and women for whom another cancer was diagnosed simultaneously (i.e. with the same cancer incidence date) with the invasive breast cancer.

Since the cause of death information can be inaccurately reported, as previously mentioned, we decided to assess the cause-specific survival of our populations of interest in terms of net survival. In the relative survival framework, net survival corresponds to the hypothetical situation where cancer is the only possible cause of death for the cancer population [21].

The assumptions underlying the relative survival framework are: a) that mortality from other causes in the cancer population is comparable to that of the general population; and b) the cancer is rare, thus the cancer-specific deaths in the general population are negligible.

If these assumptions are met, the term excess hazard can be used to describe the hazard due to the disease in the following equation:

observed hazard = population hazard + excess hazard [21]

The survival function derived from the excess hazard alone is the net survival. The differences in survival between the cancer population and the general population are then considered to be attributable to the cancer diagnosis (net survival).

In our study, women were followed from the date of their tumour diagnosis (first primary tumour diagnosis for women diagnosed with breast carcinoma in situ or invasive breast cancer; second primary tumour diagnosis for women diagnosed with breast carcinoma in situ and invasive breast cancer) until the date of emigration, date of death or end of follow-up (up to 5 years after cancer diagnosis or 31 December 2017), whichever came first. The follow-up was conducted by obtaining information on women’s vital status from the Citizen Services Department of the canton of Zurich.

When looking at treatment, we only focused on the first treatment received after an invasive breast cancer diagnosis. Treatment options were grouped as follows: breast-conserving surgery including quadrantectomy and tumourectomy, with or without lymph node dissection; mastectomy; other surgery; chemotherapy; radiotherapy; hormonal therapy; other therapy including immunotherapy and natural compounds; treatment of metastases; and unknown therapy.

Regarding oestrogen and progesterone receptor status, positive receptor status was defined as ≥10% cells stained, similarly to previous publications [22].

The invasive tumour was staged using the TNM classification. The pathological stage was used when available; otherwise the clinical stage was used. Cases up to 2009 were coded according to TNM 6, cases from 2010 onward according to TNM 7. We set clinical M to zero if missing. Missing N and T were set to missing if both clinical and pathological N/T were missing. In stratified analyses, the stage was dichotomised as early-stage (stages I and II) or late-stage (stage III, IV or unknown).

Age at cancer diagnosis was dichotomised around 65 years (<65 or ≥65) as in Howlader et al. [14]. For women diagnosed with breast carcinoma in situ who later developed invasive breast cancer (second study population), we used the age at diagnosis of invasive breast cancer; for women who developed only breast carcinoma in situ (first study population) or invasive breast cancer (third study population) during our study period, we used age at their primary tumour diagnosis.

Differences in the characteristics of invasive breast tumours diagnosed in women with (second study population, as shown in figure 1) or without (third study population) a previously recorded breast carcinoma in situ tumour were explored descriptively. Since we believe that descriptive analyses should not be tested for statistical significance, no tests were performed.

Figure 1Schematic representation of the populations used in the study.

We performed net survival analyses in a relative survival framework using the nonparametric Pohar Perme estimator (relsurv package in R [23]), using the population life tables for the canton of Zurich as the comparator population. The life tables were produced by the National Institute for Cancer Epidemiology and Registration (NICER) and reported the estimated probability of dying for ages 0 to 99. The estimated probability of dying was reported separately for each sex and was available from 2003 to 2017. Since the package relsurv required the yearly probability of death until 110 years of age for the calculations, we assigned the probability of dying corresponding to 99 years old to ages between 100 and 110 for each calendar year within our study period. Results were presented as net survival and its corresponding confidence intervals (CI).

Analyses were performed in R (Version 3.5.0, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Cancer cases in the canton of Zurich are reported to the registry with both consent and recording presumed on the basis of a decision by the Zurich Government Council in 1980 and the general registry approval by the Federal Commission of Experts for professional secrecy in medical research in 1995. All data were used anonymously in this analysis, so approval was not required from the Ethical Committee of the canton of Zurich.

The characteristics of invasive breast tumours diagnosed in women with or without a previously recorded breast carcinoma in situ tumour are presented in table 1. While no important difference was observed in the age at invasive breast tumour diagnosis, invasive breast tumours diagnosed in women with a previously recorded breast carcinoma in situ tumour were detected at an earlier stage and had less missing information for tumour-specific variables (e.g. oestrogen- or progesterone-receptor status) compared to invasive tumours diagnosed in women without a previously recorded breast carcinoma in situ.

Table 1Differences in invasive breast tumour characteristics based on whether or not they were preceded by a recorded breast cancer in situ in the canton of Zurich, Switzerland, 2003–2016.

| Invasive breast tumour preceded by a recorded breast cancer in situ (n = 93) | Invasive breast tumour not preceded by a recorded breast cancer in situ (n = 12279) | ||

| Patient’s age at invasive tumour diagnosis, mean ± standard deviation | 60.3 ± 12.7 | 61.8 ± 14.4 | |

| Treatment of the invasive tumour, n (%) | Breast-conserving surgery | 49 (52.7) | 5634 (45.9) |

| Mastectomy | 31 (33.3) | 2236 (18.2) | |

| Other surgery | 3 (3.2) | 421 (3.4) | |

| Chemotherapy | 4 (4.3) | 590 (4.8) | |

| Radiotherapy | 3 (3.2) | 1,173 (9.6) | |

| Hormonal therapy | 1 (1.1) | 1589 (12.9) | |

| Other therapy (including immunotherapy and natural compounds) | 1 (1.1) | 191 (1.6) | |

| Treatment of metastases | – | 20 (0.2) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1.1) | 425 (3.5) | |

| Stage of the invasive tumour, n (%) | I | 55 (59.1) | 4140 (33.7) |

| II | 14 (15.1) | 4787 (39.0) | |

| III | 11 (11.8) | 1907 (15.5) | |

| IV | 5 (5.4) | 751 (6.1) | |

| Unknown | 8 (8.6) | 694 (5.7) | |

| Oestrogen receptor status, n (%) | Positive | 64 (68.8) | 5399 (44.0) |

| Negative | 4 (4.3) | 947 (7.7) | |

| Unknown | 25 (26.9) | 5933 (48.3) | |

| Progesterone receptor status, n (%) | Positive | 50 (53.8) | 4616 (37.6) |

| Negative | 18 (19.4) | 1725 (14.0) | |

| Unknown | 25 (26.9) | 5938 (48.4) | |

| HER2 receptor status, n (%) | Overexpressed | 12 (12.9) | 948 (7.7) |

| Not overexpressed | 55 (59.1) | 5312 (43.3) | |

| Unknown | 26 (28.0) | 6019 (49.0) | |

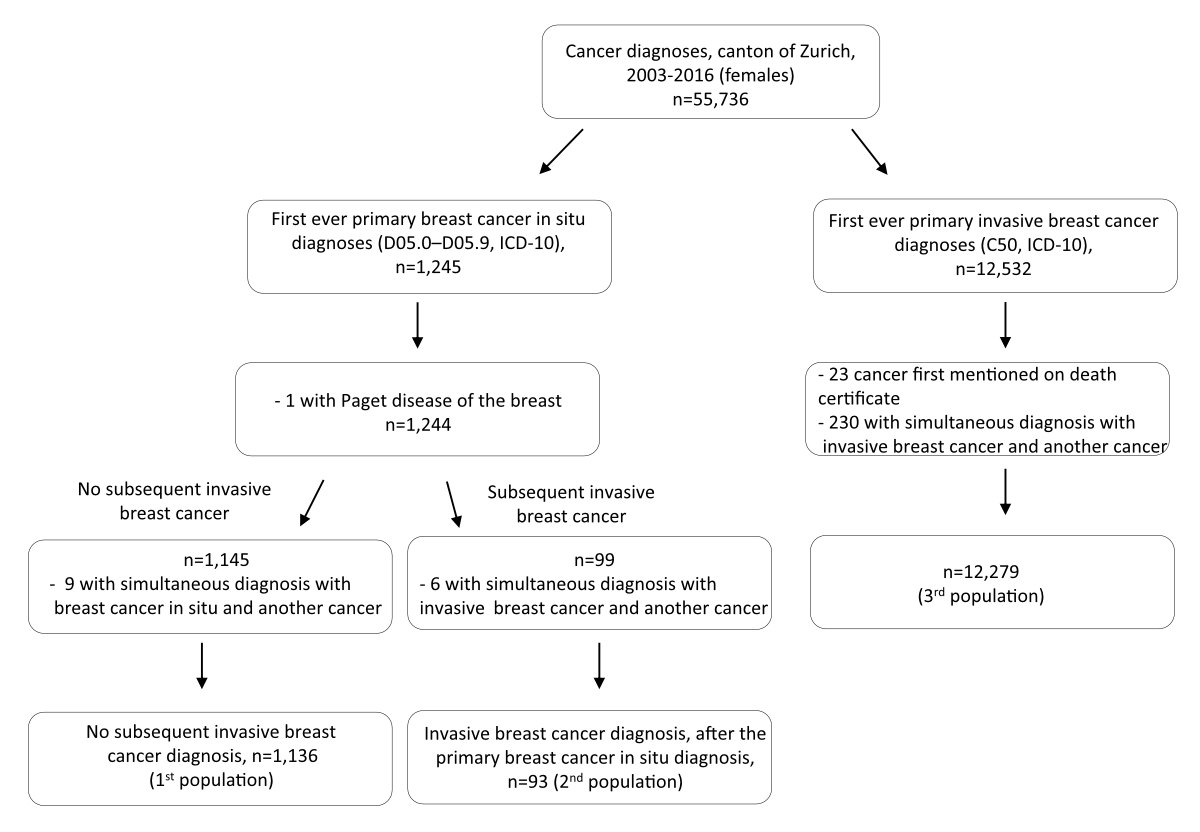

The overall 5-year net survival in the three study populations is shown in figure 2. breast carcinoma in situ patients had a net survival of 1.02 (95% CI: 1.01–1.03), whereas invasive breast cancer patients without a previous recorded breast carcinoma in situ had a net survival of 0.89 (95% CI: 0.88–0.90). Patients diagnosed with breast carcinoma in situ and then invasive breast cancer had a 5-year net survival of 0.92 (95% CI: 0.85–1.01). However, the confidence intervals of the net survival estimates between the study populations were overlapping.

Figure 25-year net survival according to cancer type (in situ breast cancer [n = 1136], invasive breast cancer not preceded by a recorded in situ breast cancer [n = 12,279], invasive breast cancer preceded by a recorded in situ breast cancer [n = 93]). The dotted lines represent the estimated 95% confidence interval for each study population.

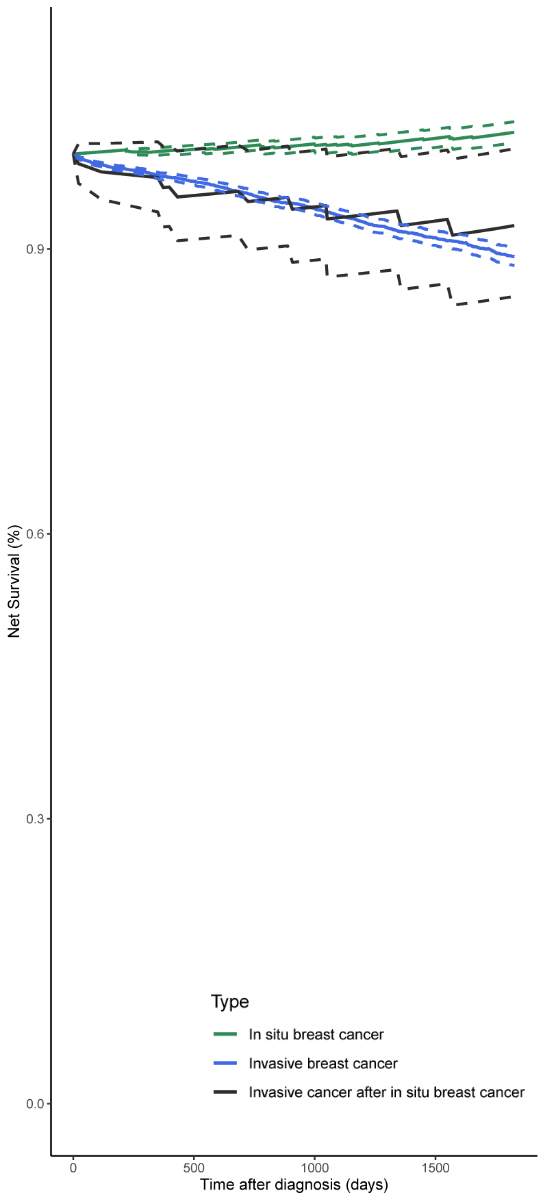

The 5-year net survival according to age at cancer diagnosis (<65 vs ≥65) is presented in figure 3. Breast carcinoma in situ patients diagnosed at an older age had higher net survival compared to those diagnosed younger (net survival≥65: 1.07, 95% CI: 1.04–1.11 vs net survival<65: 1.00, 95% CI: 1.00–1.01; figure 3a). In patients diagnosed with invasive breast cancer, net survival was slightly higher for older patients diagnosed with breast carcinoma in situ and then invasive breast cancer (net survival≥65: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.81–1.10 vs net survival<65: 0.91, 95% CI: 0.82–1.00; figure 3b). In those diagnosed with invasive breast cancer without a previously recorded breast carcinoma in situ, younger patients showed better net survival (net survival≥65: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.84–0.88 vs net survival<65: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.91–0.93; figure 3c). However, the confidence intervals of the net survival estimates in the study populations overlapped.

Figure 35-year net survival according to age at cancer diagnosis and cancer type: (a) In situ breast cancer (n<65 = 830, n≥65 = 306); (b) Invasive breast cancer preceded by a recorded in situ breast cancer (n<65 = 58, n≥65 = 35); (c) Invasive breast cancer not preceded by a recorded in situ breast cancer (n<65 = 6889, n≥65 = 5390). The dotted lines represent the estimated 95% confidence interval for each study population and age group.

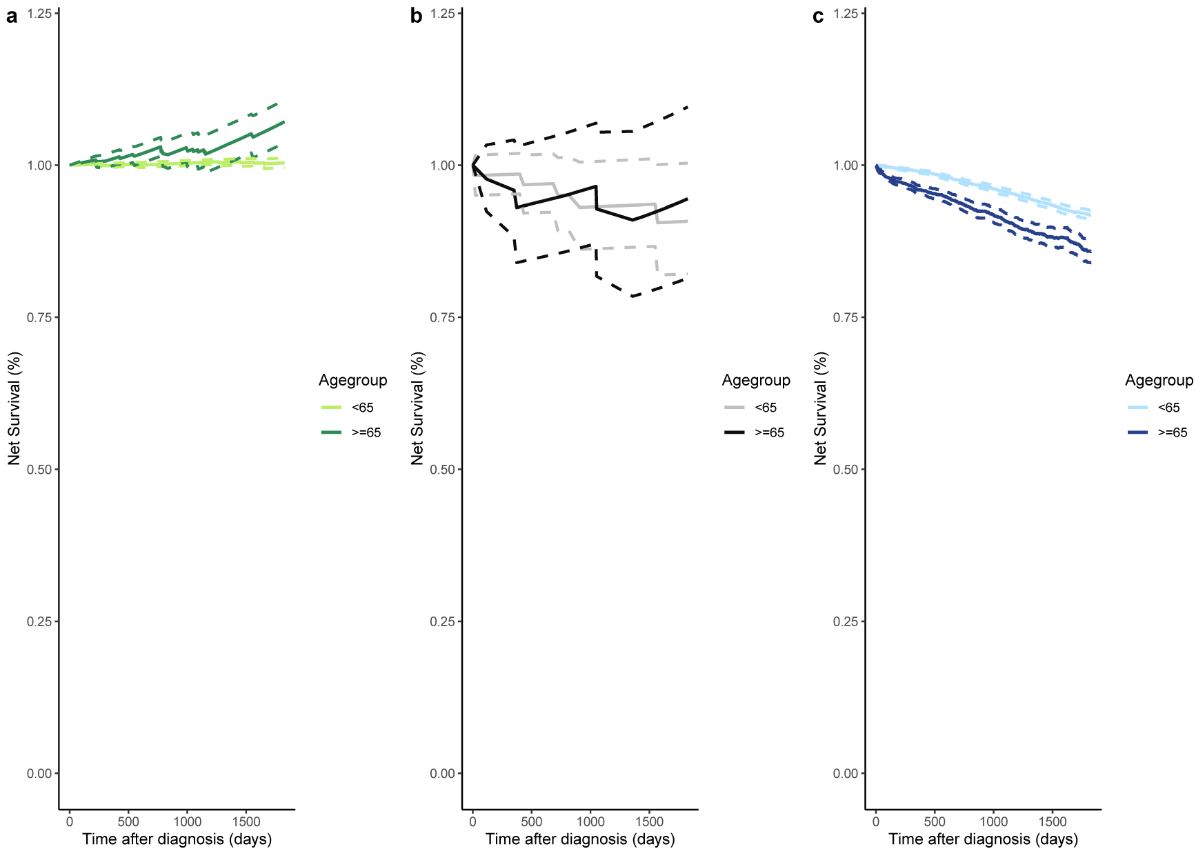

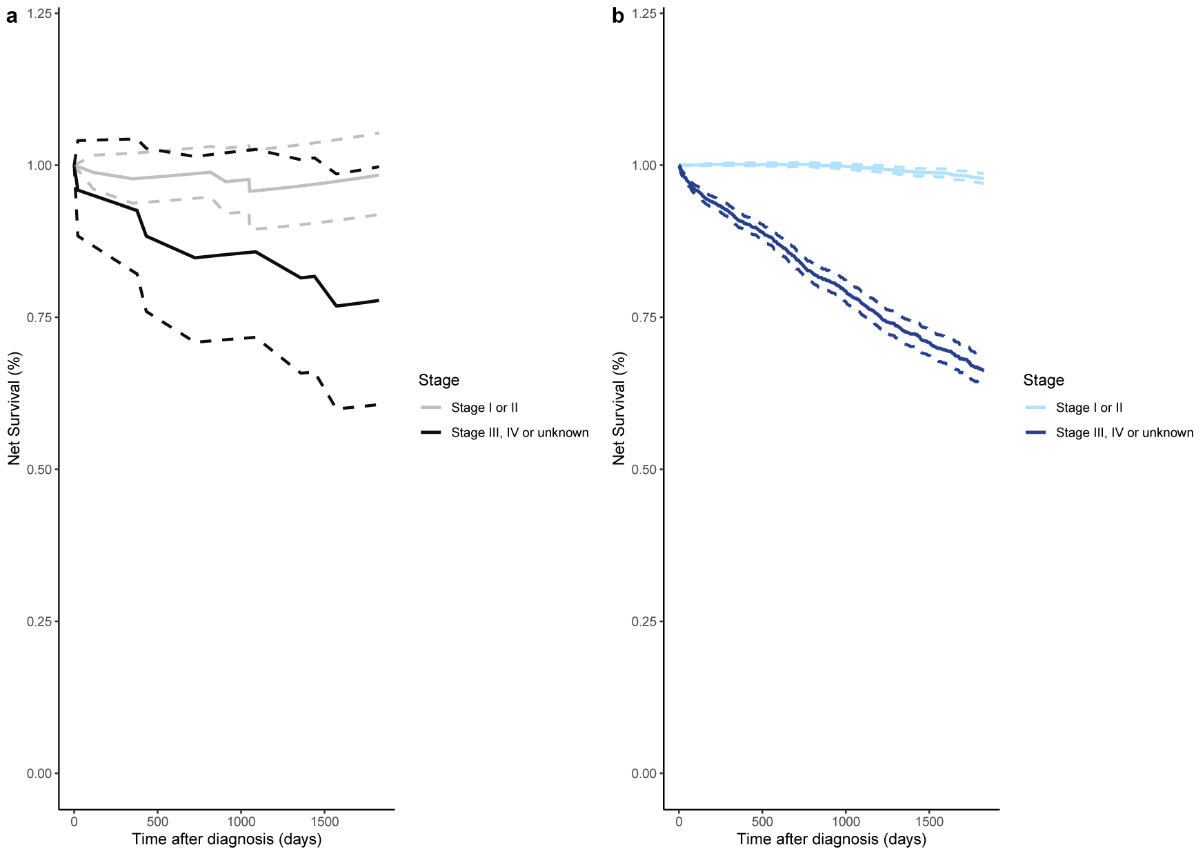

Differences in 5-year net survival based on the stage of invasive breast cancer are presented in figure 4. As expected, net survival was better for patients with early-stage compared to late-stage invasive breast tumours, irrespective of whether these were preceded by a recorded breast carcinoma in situ. In patients diagnosed with early-stage invasive breast cancer (stage I or II), the net survival was comparable between those who had had an earlier breast carcinoma in situ (0.98, 95% CI: 0.92–1.05; figure 4a) and those who had not (0.98, 95% CI: 0.97–0.99; figure 4b). However, in patients diagnosed with late-stage invasive breast cancer (stage III, IV or unknown), 5-year net survival was higher in those who had had an earlier breast carcinoma in situ (0.78, 95% CI: 0.61–1.00 vs 0.66, 95% CI: 0.64–0.69), although the confidence intervals overlapped.

Figure 45-year net survival according to stage of invasive breast cancer: (a) Invasive breast cancer preceded by a recorded in situ breast cancer (nearly = 69, nlate = 24); (b) Invasive breast cancer not preceded by a recorded in situ breast cancer (nearly = 8927, nlate = 3352). The dotted lines represent the estimated 95% confidence interval for each study population and cancer stage group.

Our findings demonstrated differences in invasive breast tumour characteristics according to whether or not the patients had previously been diagnosed with breast carcinoma in situ. Additionally, we showed that the net survival of breast carcinoma in situ patients in the 5 years following their diagnosis was very high. Differences were detected between the three populations of interest (breast carcinoma in situ patients; invasive breast cancer patients without a previously recorded breast carcinoma in situ; and patients diagnosed with invasive breast cancer following a breast carcinoma in situ diagnosis), as well as according to the age at diagnosis and the cancer stage. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report on the survival of breast carcinoma in situ patients in Switzerland.

The proportion of stage I invasive breast cancers diagnosed after breast carcinoma in situ in our study (59%) was similarly high in a previous study: Romero and colleagues reported that 51% of invasive breast cancers diagnosed after breast carcinoma in situ were stage I [15]. This finding might indicate that the monitoring of breast carcinoma in situ patients is more intensive after their initial diagnosis and treatment.

Given that cause of death information can be inaccurately reported in cancer patients, we assessed the cause-specific survival of our populations of interest in terms of net survival [24]. In the relative survival framework, breast carcinoma in situ patients in our study showed very good 5-year net survival outcomes (net survival 1.02, 95% CI: 1.01–1.03), most probably indicating that breast carcinoma in situ patients do not die of their cancer. These results are comparable to breast cancer-specific estimates reported in the literature of approximately 1% breast cancer-specific mortality 5 years after breast carcinoma in situ diagnosis [25, 26].

Patients diagnosed with invasive breast cancer after an initial breast carcinoma in situ diagnosis in our study exhibited high 5-year net survival. Our results are comparable to the 5-year estimates of previous studies reporting 80–90% breast cancer-specific survival in breast carcinoma in situ patients after subsequent breast cancer diagnosis [13, 27]. Studies with longer follow-up reported that the 10-year breast cancer-specific survival of breast carcinoma in situ patients subsequently diagnosed with invasive breast cancer ranged between 60% and 85% [13, 15, 28]. Most of the aforementioned studies were either randomised controlled trials with the comparison between treatment regimens as their primary endpoint or single hospital assessments in which all patients followed the same treatment regimen. The advantage of our study, which overcomes the lack of detailed information on cause of death, is the ability to capture the events of the entire female population in the canton of Zurich irrespective of treatment centre or treatment regimen administered.

The majority of studies reported that women who were diagnosed with invasive breast cancer after breast carcinoma in situ had higher overall and breast cancer-specific mortality risk, compared to those who were diagnosed with invasive breast cancer without a previous breast carcinoma in situ [25, 27, 29, 30]. Our results showed similar net survival for patients diagnosed with invasive breast cancer after breast carcinoma in situ and those with invasive breast cancer without a previous breast carcinoma in situ, with the 95% CIs of the two groups overlapping.

Comparison of the survival of patients diagnosed with breast carcinoma in situ is complicated by the fact that studies use different inclusion criteria (only ductal carcinoma in situ or even specific morphological subtypes of ductal carcinoma in situ compared to the inclusion of both ductal carcinoma in situ and lobular carcinoma in situ in our study), analytical strategies (relative survival, net survival or cause-specific survival), study durations and comparator populations. Despite these differences, all studies agree that survival of breast carcinoma in situ patients later diagnosed with invasive breast cancer is lower compared to that of breast carcinoma in situ patients without a subsequent invasive diagnosis [25, 27, 29, 30]. Our results are in line with these publications. Breast carcinoma in situ patients without a subsequent invasive diagnosis had better survival than those who were later diagnosed with invasive breast cancer.

Our stratified results showed differences in net survival based on age at cancer diagnosis. Our age-stratified findings are comparable to the breast-cancer specific survival reported by Howlader and colleagues (≥65: 98.6, 95% CI: 98.4–98.8 vs <65: 99.7, 95% CI: 99.6–99.8) [14], even though our estimates indicate slightly increased cancer-specific survival in both age groups. This difference could be due to our division of the breast carcinoma in situ population into those with or without a subsequent invasive breast cancer diagnosis.

Studies have attributed the higher relative survival of breast carcinoma in situ patients to differences between them and the general population included in the life tables [14]. Similarly, favourable relative survival outcomes have also been reported for other early-stage cancers, including prostate cancer [31]. Studies consider breast carcinoma in situ patients to be healthier and have longer life expectancy than the general population [14]. Interestingly, however, a study found little positive lifestyle modifications (smoking cessation) in breast carcinoma in situ patients after diagnosis. Breast carcinoma in situ patients tended to gain weight and showed little difference in fruit and vegetable consumption or in alcohol intake after diagnosis, compared to their retrospectively assessed pre-diagnostic habits [32].

Our study had several strengths. Given the high registry coverage in the canton of Zurich, we are confident that we captured almost all incident breast cancer events in the canton during the study period [33]. Additionally, medical and treatment information as well as patient and tumour characteristics were available for a high proportion of our study populations, allowing us to stratify our net survival analyses and to compare the main tumour characteristics between invasive breast tumours according to whether or not they had been preceded by a recorded breast carcinoma in situ. Estimation of the net survival in a relative survival framework meant that information on cause of death was not required and thus potential biases due to uncertainties of death certification were avoided.

Our study also had some weaknesses. The low number of patients diagnosed with invasive breast cancer following a breast carcinoma in situ diagnosis did not allow us to investigate potential differences between invasive tumours diagnosed in the ipsilateral or the contralateral breast or explore the results by the morphology of the initial breast carcinoma in situ tumour (ductal carcinoma in situ compared to lobular carcinoma in situ). However, previous research reported similar mortality in women diagnosed with ipsilateral or contralateral invasive breast cancer after breast carcinoma in situ [30]. Additionally, the low number of patients diagnosed with invasive breast cancer following a breast carcinoma in situ diagnosis did not allow us to investigate the potential impact of different treatment regimens on survival. We cannot exclude the possibility that some breast carcinoma in situ cases were not reported to the cancer registry, were diagnosed before 2003 or in a different part of Switzerland or abroad, or went undetected due to lack of symptoms, before an invasive breast tumour diagnosis.

Invasive breast tumours that were preceded by a recorded breast carcinoma in situ diagnosis exhibited more-favourable tumour characteristics (including earlier stage at diagnosis and fewer missing values) than those that were not. Breast carcinoma in situ patients have overall very good net survival outcomes 5 years after their diagnosis. The 5-year net survival of patients diagnosed with invasive breast tumours was relatively high, irrespective of whether the patient had a previously recorded breast carcinoma in situ. Larger studies should aim to further investigate the survival of breast carcinoma in situ patients who later develop invasive breast cancer, as well as factors associated with better breast cancer-specific survival outcomes.

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available since they are stored with personal identifiers but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer

Where authors are identified as personnel of the European Food Safety Authority, the authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy or views of the European Food Safety Authority.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualisation: NK and SR; data acquisition: ML, DK and MW; formal analysis: NK and EM; writing – original draft preparation: NK; writing – review and editing: NK, EM, ML, DK, MW and SR; visualisation: NK and EM; supervision: SR; funding acquisition: SR. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Krebsforschung Schweiz under Grant KFS-4114-02-2017 to SR. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

1. Ward EM, DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Kramer JL, Jemal A, Kohler B, et al. Cancer statistics: breast cancer in situ. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(6):481–95.

2. Leonard GD, Swain SM. Ductal carcinoma in situ, complexities and challenges. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(12):906–20.

3. Groen EJ, Elshof LE, Visser LL, Emiel JT, Winter-Warnars HA, Lips EH, et al. Finding the balance between over-and un-der-treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Breast. 2017;31:274–83. 10.1016/j.breast.2016.09.001

4. Karavasiloglou N, Matthes KL, Berlin C, Limam M, Wanner M, Korol D, et al. Increasing trends in in situ breast cancer incidence in a region with no population-based mammographic screening program: results from Zurich, Switzerland 2003-2014. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019 Mar;145(3):653–60.

5. Bordoni A, Probst-Hensch N, Mazzucchelli L, Spitale A. Assessment of breast cancer opportunistic screening by clinical–pathological indicators: a population-based study. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(11):1925–31. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605378

6. Virnig BA, Tuttle TM, Shamliyan T, Kane RL, Outcomes JN. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a systematic review of incidence, treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(3):170–8.

7. Falk RS, Hofvind S, Skaane P, Haldorsen T. Second events following ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a register-based cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129(3):929–38.

8. Franceschi S, Levi F, La Vecchia C, Randimbison L, Te VC. Second cancers following in situ carcinoma of the breast. Int J Cancer. 1998;77(3):392–5. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19980729)77:3<392::AID-IJC14>3.0.CO;2-A

9. Levi F, Randimbison L, Te VC, La Vecchia C. Invasive breast cancer following ductal and lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast. Int J Cancer. 2005;116(5):820–3.

10. Sackey H, Hui M, Czene K, Verkooijen H, Edgren G, Frisell J, et al. The impact of in situ breast cancer and family history on risk of subsequent breast cancer events and mortality-a population-based study from Sweden. Breast Cancer Res. 2016;18(1):105. 10.1186/s13058-016-0764-7

11. Soerjomataram I, Louwman WJ, van der Sangen MJ, Roumen RM, Coebergh JW. Increased risk of second malignancies after in situ breast carcinoma in a population-based registry. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(3):393–7.

12. Karavasiloglou N, Matthes KL, Pestoni G, Limam M, Korol D, Wanner M, et al. Risk for Invasive Cancers in Women With Breast Cancer In Situ: Results From a Population Not Covered by Organized Mammographic Screening. Front Oncol. 2021 Mar;11:606747.

13. Donker M, Litiere S, Werutsky G, Julien JP, Fentiman IS, Agresti R, et al. Breast-conserving treatment with or without ra-diotherapy in ductal carcinoma in situ: 15-year recurrence rates and outcome after a recurrence, from the EORTC 10853 randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(32):4054–9. 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.5077

14. Howlader N, Ries LA, Mariotto AB, Reichman ME, Ruhl J, Cronin KA. Improved estimates of cancer-specific survival rates from population-based data. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(20):1584–98. 10.1093/jnci/djq366

15. Romero L, Klein L, Ye W, Holmes D, Soni R, Silberman H, et al. Outcome after invasive recurrence in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Am J Surg. 2004;188(4):371–6. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.06.034

16. Mieno MN, Tanaka N, Arai T, Kawahara T, Kuchiba A, Ishikawa S, et al. Accuracy of death certificates and assessment of factors for misclassification of underlying cause of death. J Epidemiol. 2016;26(4):191–8. 10.2188/jea.JE20150010

17. Sarfati D, Blakely T, Pearce N. Measuring cancer survival in populations: relative survival vs cancer-specific survival. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(2):598–610. 10.1093/ije/dyp392

18. Lloyd-Jones DM, Martin DO, Larson MG, Levy D. Accuracy of death certificates for coding coronary heart disease as the cause of death. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(12):1020–6. 10.7326/0003-4819-129-12-199812150-00005

19. Modelmog D, Rahlenbeck S, Trichopoulos D. Accuracy of death certificates: a population-based, complete-coverage, one-year autopsy study in East Germany. Cancer Causes Control. 1992;3(6):541–6.

20. Smith Sehdev AE, Hutchins GM. Problems with proper completion and accuracy of the cause-of-death statement. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(2):277–84.

21. Perme MP, Stare J, Estève J. On estimation in relative survival. Biometrics. 2012;68(1):113–20. 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2011.01640.x

22. James RE, Lukanova A, Dossus L, Becker S, Rinaldi S, Tjønneland A, et al. Postmenopausal serum sex steroids and risk of hormone receptor–positive and-negative breast cancer: a nested case–control study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2011;4(10):1626–35. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0090

23. Perme MP, Pavlic K. Nonparametric relative survival analysis with the R package relsurv. J Stat Softw. 2018;87(1):1–27. 10.18637/jss.v087.i08

24. Nagamine CM, de Goulart BN, Ziegelmann PK. Net Survival in Survival Analyses for Patients with Cancer: A Scoping Review. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(14):3304.

25. Elshof LE, Schmidt MK, Emiel JT, Rutgers FE, Wesseling J, Schaapveld M. Cause-specific mortality in a population-based cohort of 9799 women treated for ductal carcinoma in situ. Ann Surg. 2018;267(5):952–8. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002239

26. Wärnberg F, Bergh J, Holmberg L. Prognosis in women with a carcinoma in situ of the breast: a population-based study in Sweden. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8(9):769–74.

27. Sopik V, Nofech-Mozes S, Sun P, Narod SA. The relationship between local recurrence and death in early-stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;155(1):175–85. 10.1007/s10549-015-3666-y

28. Yun KW, Kim J, Lee JW, Lee SB, Kim HJ, Chung IY, et al. Long-term Follow-up of Pure Ductal Carcinoma in situ after Breast-Conserving Surgery. J Breast Dis. 2019;7(2):73–80. 10.14449/jbd.2019.7.2.73

29. Narod SA, Iqbal J, Giannakeas V, Sopik V, Sun P. Breast cancer mortality after a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(7):888–96. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2510

30. Wapnir IL, Dignam JJ, Fisher B, Mamounas EP, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, et al. Long-term outcomes of invasive ipsilateral breast tumor recurrences after lumpectomy in NSABP B-17 and B-24 randomized clinical trials for DCIS. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(6):478–88. 10.1093/jnci/djr027

31. Matthes KL, Limam M, Dehler S, Korol D, Rohrmann S. Primary treatment choice over time and relative survival of prostate cancer patients: influence of age, grade, and stage. Oncol Res Treat. 2017;40(9):484–9. 10.1159/000477096

32. Sprague BL, Trentham-Dietz A, Nichols HB, Hampton JM, Newcomb PA. Change in lifestyle behaviors and medication use after a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;124(2):487–95. 10.1007/s10549-010-0869-0

33. Wanner M, Matthes KL, Korol D, Dehler S, Rohrmann S. Indicators of Data Quality at the Cancer Registry Zurich and Zug in Switzerland. BioMed Res Int. 2018;2018:7656197.