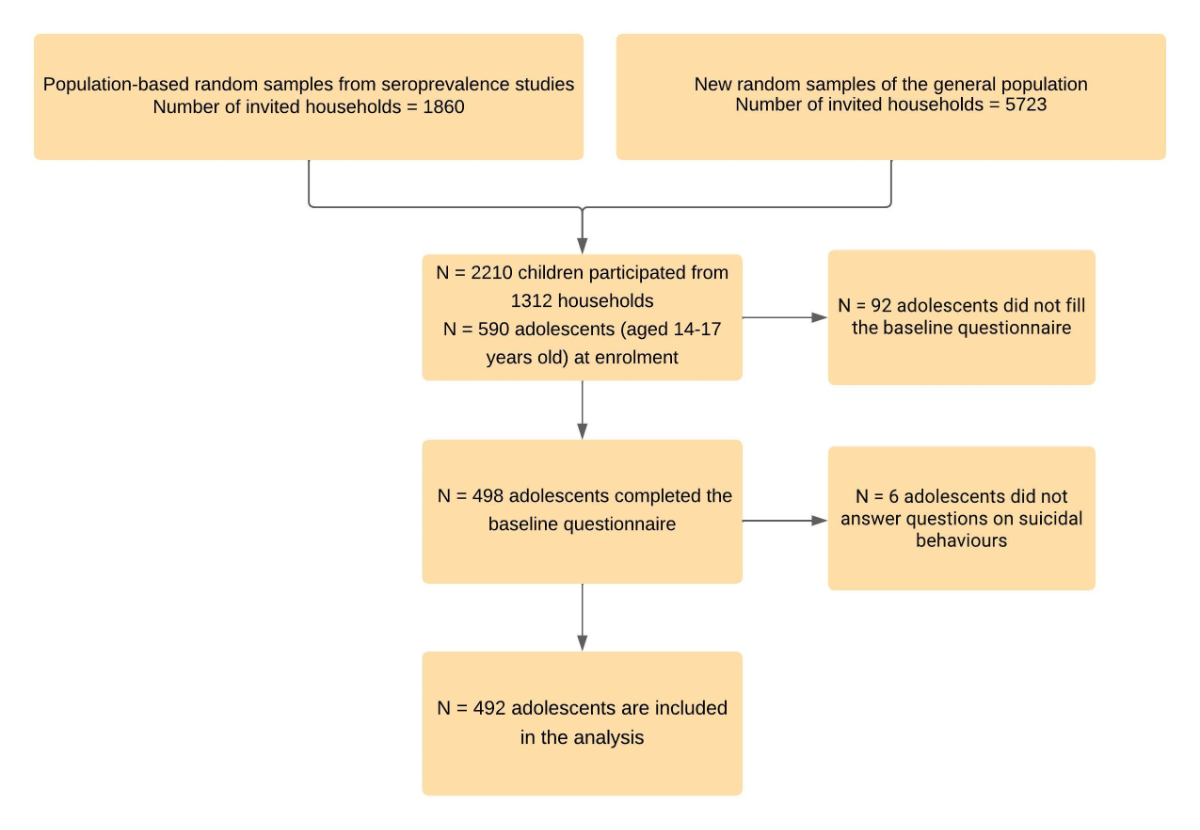

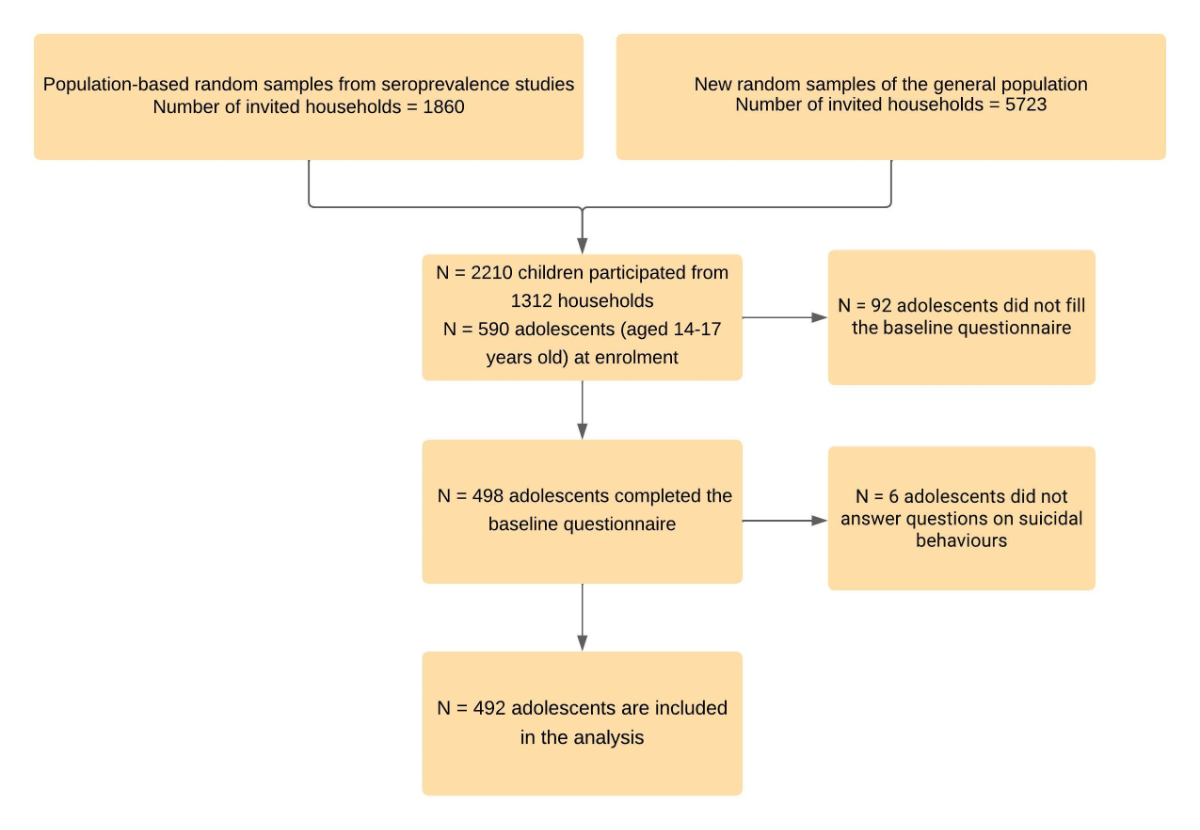

Figure 1Participant recruitment and inclusion in the analysis sample. The flowchart illustrates the process of recruitment and participation.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/s.3461

Suicide is the fourth leading cause of death of adolescents and young adults worldwide [1]. Suicidality represents a continuum of behaviours that span various levels of severity, encompassing suicidal ideation, suicide attempts and death by suicide [2]. Although strong associations have been established between the severity of suicidal thoughts and the risk of attempting suicide, it is important to acknowledge that only a minority of individuals proceed from suicidal thoughts to attempt. Different suicidal behaviours are associated with different risk factors, with specific study designs tailored to each type of behaviour [3].

Suicidal ideation often emerges during adolescence, a period marked by strong psychological and physical changes [4]. Despite being common among adolescents, there is a lack of comprehensive estimates that accurately depict its overall prevalence. A pre-pandemic comparison study, which included a sample of over 275,000 adolescents aged 12–17 years from 82 countries (including low-income, lower-middle-income, upper-middle-income and high-income countries) in 2003–2015 estimated the overall 12-month pooled prevalence of suicidal ideation to be 14% [5]. When stratified by regions, the highest prevalence was found in Africa (21.0%) and the lowest in Asia (8.0%), while the prevalence in Europe was 11%. The important heterogeneity in estimates was partially attributed to disparities in mental health care support, cultural factors and access to care.

The factors contributing to suicidal ideation in adolescents are complex and multifaceted. Previous studies highlight various risk factors such as female sex, older age, depressive symptoms, loneliness or substance use [6], being a migrant [7], identifying as a sexual minority [8], being bullied and addictive use of social media [9]. Although various risk factors have been identified, suicidal ideation remains a multifaceted phenomenon that involves intricate interactions among psychological, social and biological factors. Therefore, it is essential to employ appropriate statistical tools to understand these complexities. One such tool is network analysis, a powerful statistical method that can be used to examine the interactions between multiple risk factors and their relationship with suicidal ideation, enabling the identification of the most influential factors and an understanding of their interplay [10, 11].

The COVID-19 pandemic had a profound impact on the daily life of children and adolescents worldwide [12]. Suicidal behaviours may have increased due to the general pandemic environment, while risk factors may have been exacerbated due to pandemic-related general societal changes. Two meta-analyses based on general population data estimated the pooled prevalence of suicidal ideation since the beginning of the pandemic to be 12%, which appears slightly higher than the pre-pandemic prevalence in Europe [13]. Also, amid the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea, a serial cross-sectional survey conducted nationwide reported a surge in suicidal ideation among adolescents, with rates rising from 10.7% in 2020 to 12.5% in 2021 [14]. Pandemic-related risk factors for suicidal ideation were also identified, namely low social support, mental health difficulties, sleep disturbances, quarantine, exhaustion and loneliness [15].

While there is a substantial body of research examining this subject in adults, there has been limited investigation into suicidal thoughts among adolescents two years into the pandemic, particularly in studies based on representative samples including Switzerland. Recent local reports highlighted a worrying increase in psychiatric consultations among adolescents since the beginning of the pandemic [16], a finding that warrants further investigation in population-based studies.

The objective of the present analysis is two-fold: (1) to estimate the prevalence among adolescents of self-reported suicidal ideation over the previous 12 months and (2) to identify both direct and indirect risk factors associated with suicidal ideation in adolescents, two years after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data were collected from the SEROCoV-KIDS study, a population-based cohort aiming to assess mid- and long-term outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents living in the State of Geneva, Switzerland.

Eligibility criteria for the cohort included being aged between 6 months and 17 years and living in the canton of Geneva at the time of enrolment. For this analysis, only participants aged 14–17 years were considered. Eligible children were invited from (a) random samples from state registries,provided by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office,and (b) families who had previously been selected in state-wide population-based random samples of the general population (population-based seroprevalence studies conducted by our group) [17–20].

The baseline assessment was organised from December 2021 to June 2022. Children and adolescents were invited for a SARS-CoV-2 serology from a venous blood sample. Adolescents aged 14 years or older were asked to fill in a self-reported questionnaire in French evaluating multiple dimensions of their daily life and their pandemic-related experiences. Referent adults (parent or other legal guardian) were asked to complete a comprehensive health and sociodemographic questionnaire about themselves, their household and their child(ren). All questionnaires were completed online on the Specchio-COVID19 digital platform [21]. Informed written consent was obtained from one parent (or another legal guardian), while adolescents also gave informed written consent for themselves.

A flowchart is presented in figure 1. Data used in this analysis were self-reported by adolescents, unless stated otherwise.

Figure 1Participant recruitment and inclusion in the analysis sample. The flowchart illustrates the process of recruitment and participation.

A concise overview of the measurements is provided here, while further elaboration and additional details can be found in table S1 in the appendix.

Suicidal ideation

The primary outcome, suicidal ideation, was assessed based on the question: “In the past 12 months, have you thought about suicide?”. If the adolescent answered yes, four additional questions were asked: “Were there moments when you wanted to end your life through suicide?”, “Would you have killed yourself if you had had the chance?”, “Have you thought about the method you could have used to kill yourself?” and “Did you attempt suicide?”. These questions were adapted from previous studies by child psychiatrists and epidemiologists of the team [22].

Mental health and self-esteem

The Santé-Québec Psychological Distress Index was used to assess an individual’s psychological distress and emotional wellbeing over the last month using 10 items, with a good internal consistency (α = 0.91)[23].

Self-esteem was measured using Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem scale (RSE), a widely used scale with 10 items (α = 0.89) [24].

School difficulties

Adolescents reported their potential school difficulties including concentration problems, health or family problems affecting depreciating their school activities.

Social media addiction

Addictive social media use was identified using the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS), with an acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.75) [25].

Bullying and cyberbullying

Adolescents who were currently or had been a victim of bullying or cyberbullying were identified based on an affirmative answer to one of the statements presented in table S1 [26].

Social support and parent-adolescent relationship

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) was used to measure perceived social support from three sources: family, friends and significant others, with a good level of internal coherence (α = 0.89) [27]. Adolescents were also asked to describe their relationship with their parents on a 5-item Likert scale.

Health-compromising behaviours

Adolescents were asked about their current use of cigarettes, alcohol and drugs. They were considered users if their consumption was regular (i.e. every day or every week).

COVID-19 impact (parent-reported)

The Coronavirus impact scale [28] was used to evaluate the multidimensional impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, through parental reporting, in terms of routine, income, food access, physical and mental healthcare access, access to social and family support, stress and family discord on a 4-point Likert scale (no change, mild, moderate, severe). Parent-reported data allowed for a holistic view of the pandemic situation from a household perspective.

Other characteristics

Other variables included sociodemographic and health characteristics, such as age, sex, mother’s education, socioeconomic status (household financial status), migrant status (Swiss-born vs foreign-born), chronic condition, body mass index (BMI) and self-reported sexual orientation.

Descriptive analysis

We compared characteristics between adolescents who reported suicidal ideation over the last 12 months and those who did not, using Chi-squared and Student’s T tests, as appropriate.

Prevalences of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts were computed using binomial proportions and two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CI) and stratified by sex.

Network estimation

We used an undirected network analysis to investigate the relationship between suicidal ideation and the 20 risk factors mentioned earlier. The selection of covariates encompassing demographic, social, physical and psychological dimensions of adolescent life, in the suicidal ideation model was guided by their relevance to the research question, and was informed by a comprehensive literature review [10]. The network perspective enables the visualisation and quantification of multivariate interactions providing insights into how psychological, familial and environmental dimensions interact with one another and correlate with suicidal behaviours. The constructed network consisted of nodes representing risk factors and edges representing associations between these variables. The width of each edge in the visualised network represents the strength of the association while controlling for all the other nodes in the network. Thicker edges indicate stronger quantitative associations [29]. Unconnected nodes exhibit conditional independence given all or a subset of other nodes in the network. To estimate the network structure, we applied undirected Mixed Graphical Models (MGM) using the R package “mgm” [30]. In a mixed graphical model, which incorporates both continuous and categorical variables, the effects correspond to partial regression coefficients for continuous variables and to conditional log-odds ratios for categorical variables. These estimations quantify the relationship between variables, indicating the degree and direction of the relationship between the variables after accounting for other variables in the model. Larger effect sizes indicate stronger associations, while smaller effect sizes suggest weaker associations (supplementary material).

Network evaluation and clustering

In order to identify on which dimensions public health interventions would be more effective, we computed measures of node centrality to infer the relative influence of each variable on the rest of the network [31]. Three centrality metrics – strength, betweenness and closeness centrality – were used to measure the centrality of a node within the network’s topology. These metrics provided insights into the significance of a node based on its connections and positioning in the network. Further details on these centrality metrics are available in the supplementary material.

To identify communities within the network, we used the Spinglass clustering algorithm, defined in supplementary material.

Regression model

A logistic regression analysis was also performed as a complementary analysis, presenting both unadjusted and adjusted coefficients, while controlling for the covariates included in the network analysis.

Given that this analysis relies on a subset of the SEROCoV-KIDS study, comprising only 7% of adolescents from the same households, clustering effects were not considered in the modelling process.

Missing data

Participants with missing data in at least one of the covariates (n = 44 or 9%) were excluded from the models. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed 95% confidence level. All analyses were performed using R (version 4.0.3).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Geneva Cantonal Commission for Research Ethics approved the study (IDs 2020-00881 and 2021-01973). Parents of participants and adolescents aged 14 or older provided written informed consent. Children gave oral assent to participate.

Among 7583 invited households, 1312 participated in the SEROCoV-KIDS study (participation rate 17.3%) (figure 1). The final sample consisted of 492 adolescents from 450 households: their mean age was 15.4 years (standard deviation [SD]: 1.2) and 258 (52%) were girls (table 1). Overall, 71 (14.4%) adolescents reported having experienced suicidal ideation over the past 12 months. Results showed that girls were significantly more likely to experience suicidal ideation, as were adolescents who identified as lesbian, gay or bisexual (LGB) or who reported strong psychological distress, low self-esteem, low social support, school difficulties or suffering from bullying (table 1). Additionally, adolescents who reported an excessive use of social media, smoking, drinking alcohol or a severe pandemic impact had a higher prevalence of suicidal ideation.

Table 1Descriptive characteristics, stratified by suicidal ideation.

| Overall | Suicidal ideation | p value* | |||

| Yes | No | ||||

| n = 492 | n = 71 | n = 421 | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||

| Sex (n = 492) | Female | 258 (53%) | 53 (75%) | 205 (49%) | <0.001 |

| Male | 233 (47%) | 18 (25%) | 215 (51%) | ||

| Other | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | ||

| Mother’s education (n = 448) | 0.32 | ||||

| Tertiary | 331 (74%) | 42 (67%) | 289 (75%) | ||

| Secondary | 98 (21%) | 19 (30%) | 79 (20%) | ||

| Primary | 19 (5%) | 2 (3%) | 17 (5%) | ||

| Household financial situation (n = 457) | 0.31 | ||||

| Good | 345 (76%) | 45 (70%) | 300 (76%) | ||

| Average to poor | 79 (17%) | 16 (25%) | 63 (16%) | ||

| Did not want to answer | 33 (7%) | 3 (5%) | 30 (8%) | ||

| Migrant status | Foreign-born(n = 457) | 66 (14%) | 8 (13%) | 58 (15%) | 0.52 |

| Health characteristics | |||||

| Mental health chronic condition (n = 457) | 77 (17%) | 18 (28%) | 59 (15%) | 0.02 | |

| Physical chronic condition (n = 457) | 182 (40%) | 32 (50%) | 150 (38%) | 0.31 | |

| Other characteristics (n = 491) | |||||

| Sexual orientation | <0.001 | ||||

| Heterosexual | 350 (71%) | 34 (48%) | 316 (75%) | ||

| LGB | 62 (13%) | 25 (35%) | 37 (9%) | ||

| Did not know, Did not want to answer | 79 (16%) | 12 (17%) | 67 (16%) | ||

| Psychological characteristics (n = 492) | |||||

| Psychological distress | Psychological Distress Index – mean (SD) | 20.2 (15.0) | 37.5 (15.2) | 17.3 (12.9) | <0.001 |

| High psychological distress (score ≥30) | 118 (24%) | 48 (68%) | 70 (17%) | <0.001 | |

| Self-esteem | Rosenberg score – mean (SD) | 31.3 (6.2) | 24.5 (6.0) | 32.4 (5.4) | <0.001 |

| Low self-esteem (score ≤25) | 83 (17%) | 39 (55%) | 42 (10%) | <0.001 | |

| Social support | Score – mean (SD) | 5.7 (1.1) | 5.2 (1.1) | 5.8 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Low-to-moderate social support | 105 (21%) | 28 (39%) | 77 (18%) | <0.001 | |

| Schooling | |||||

| School difficulties(n = 492) | 83 (17%) | 21 (30%) | 62 (15%) | <0.001 | |

| Bullying (n = 490) | Suffer(ed) from bullying | 16 (3%) | 9 (13%) | 7 (2%) | <0.001 |

| Suffer(ed) from cyberbullying | 147 (30%) | 42 (56%) | 107 (25%) | <0.001 | |

| Overall bullying | 153 (31%) | 43 (61%) | 110 (26%) | <0.001 | |

| Social media addiction (n = 492) | |||||

| BSMAS score – mean (SD) | 10.9 (3.8) | 12.3 (3.8) | 10.6 (3.8) | <0.001 | |

| Severe social media addiction (score ≥15) | 94 (19%) | 21 (30%) | 73 (17%) | 0.005 | |

| Health-compromising behaviours (n = 492) | |||||

| Smoking | 35 (7%) | 16 (23%) | 19 (5%) | <0.001 | |

| Alcohol consumption | 24 (5%) | 8 (11%) | 16 (5%) | 0.04 | |

| Drug use | 6 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (1%) | >0.9 | |

| COVID-19 pandemic impact (n = 457) | |||||

| Severe | 74 (16%) | 21 (33%) | 53 (13%) | <0.001 | |

SD: standard deviation.

* Fisher’s exact, Pearson’s Chi-squared or Student’s T test, as appropriate.

Overall, 1 out of 7 (14.4%, 95% CI: 11.5–17.8) adolescents declared having had suicidal ideation in the past 12 months (table 2). Results show that prevalences of suicidal ideation and of suicide attempts were higher in females than in males, when stratifying by sex.

Table 2Prevalence of suicidal ideation, overall and stratified by sex.

| Suicidality | Among all participants (n = 492) | Among females (n = 258)* | Among males (n = 233) | Among adolescents who experienced suicidal ideation over the last 12 months (n = 71) |

| Adolescents reported that… | Number (Binomial proportion [95% confidence interval]) | |||

| …they had thought about suicide over the last 12 months. | 71 (14.4% [11.5–17.8%]) | 53 (20.5% [16.0–26.0%]) | 18 (7.7% [4.8–11.9%]) | 71 (100%) |

| …there were moments when they wanted to end their life through suicide. | 49 (10.0% [7.5–13.0%]) | 42 (16.2% [12.3–21.3%]) | 7 (3.0% [1.3–6.3%]) | 49 (69.0% [56.9–78.9%]) |

| …they would have killed themselves if they had had the chance. | 10 (2.0% [1.0–3.8%]) | 9 (3.5% [1.7–6.7%]) | 1 (0.4% [0.02–2.7%]) | 10 (14.0% [7.3–25.0%]) |

| …they had thought about the method they could have used to kill themselves. | 50 (10.1% [7.7–13.0%]) | 39 (15% [11.2–20.1%]) | 11 (4.7% [2.5–8.4%]) | 50 (70.4% [58.0–80.1%]) |

| …they had attempted suicide in the last 12 months | 5 (1.0% [0.4–2.5%]) | 5 (1.9% [0.7–4.7%]) | – | 5 (7.0% [2.6–16.0%]) |

| and that their family and friends knew about it. | 2 (0.4% [0.0–1.6%]) | 2 (0.8% [0.1–3.1%]) | – | 2 (2.8% [0.4–11.3%]) |

| …they had attempted suicide in their lifetime (including in the last 12 months). | 13 (2.6% [1.5–4.6%]) | 10 (3.9% [2.0–7.2%]) | 3 (1.2% [0.2–3.4%]) | 13 (18.3% [10.4–28.5%]) |

* One adolescent self-identified as “sex = other” and was excluded from the stratified analysis.

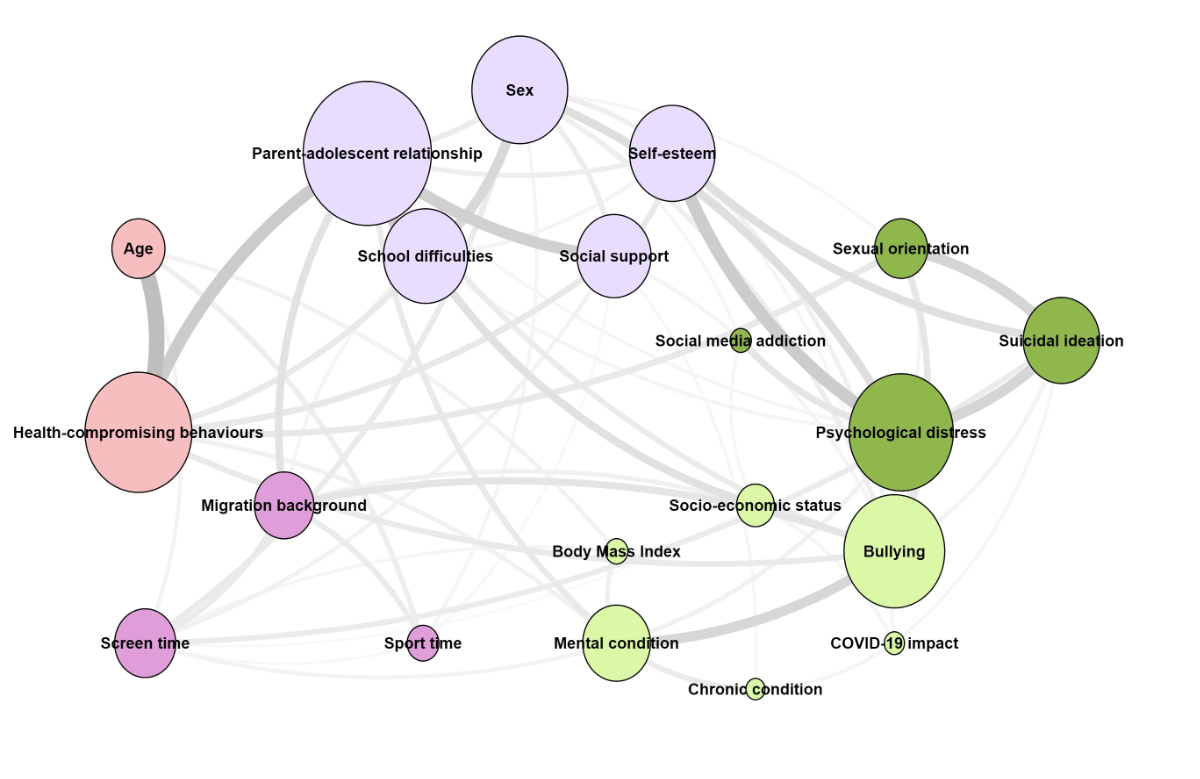

The network analysis revealed that high psychological distress, low self-esteem, identifying as LGB, experiencing bullying and excessive screen time were the main direct risk factors for suicidal ideation (figure 2). Furthermore, there was a moderate association (narrow edge) between COVID-19 pandemic negative impact and suicidal ideation.

Figure 2Network analysis of suicidal ideation and associated risk factors. Network of direct and indirect risk factors associated with suicidal ideation. The nodes in the network represent risk factors, with those directly connected to suicidal ideation identified as direct risk factors. These include psychological distress, sexual orientation, self-esteem, screen time, bullying and COVID-19 pandemic impact. The size of each node corresponds to the strength centrality, with the strongest being parent-adolescent relationship. The width of edges represents the strength of the association between risk factors, with thicker edges indicating stronger associations. Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection (LASSO) regularisation, which shrinks all parameter estimates towards zero and sets very small estimates to exactly zero was used to estimate parameters. Associations with low significance are not seen in the network. The clusters identified by the Spinglass algorithm are represented by different colours.

The analysis showed that psychological distress was primarily associated with female sex, low self-esteem and excessive use of social media, whereas sexual orientation was strongly related to bullying. Low self-esteem was related to psychological distress, low social support, female sex and moderately linked to parent-adolescent relationship, school difficulties, bullying and COVID-19 pandemic impact. Excessive screen time was associated with male sex and moderately with higher BMI, migration background, school difficulties, lower social support and low levels of physical activity. Parent-adolescent relationship was connected to social support, health-compromising behaviours, migration status and school difficulties. Socioeconomic characteristics were not directly associated with suicidal ideation, but were related to COVID-19 pandemic impact, school difficulties, migration status and mental health conditions.

The clustering algorithm identified four main clusters of risk factors in the network (represented by colours in figure 2). The cluster including suicidal ideation combined individuals sharing similar characteristics regarding sexual orientation, psychological distress and social media use. It highlights a group of individuals densely connected to each other and at a higher risk of exhibiting suicidal ideation.

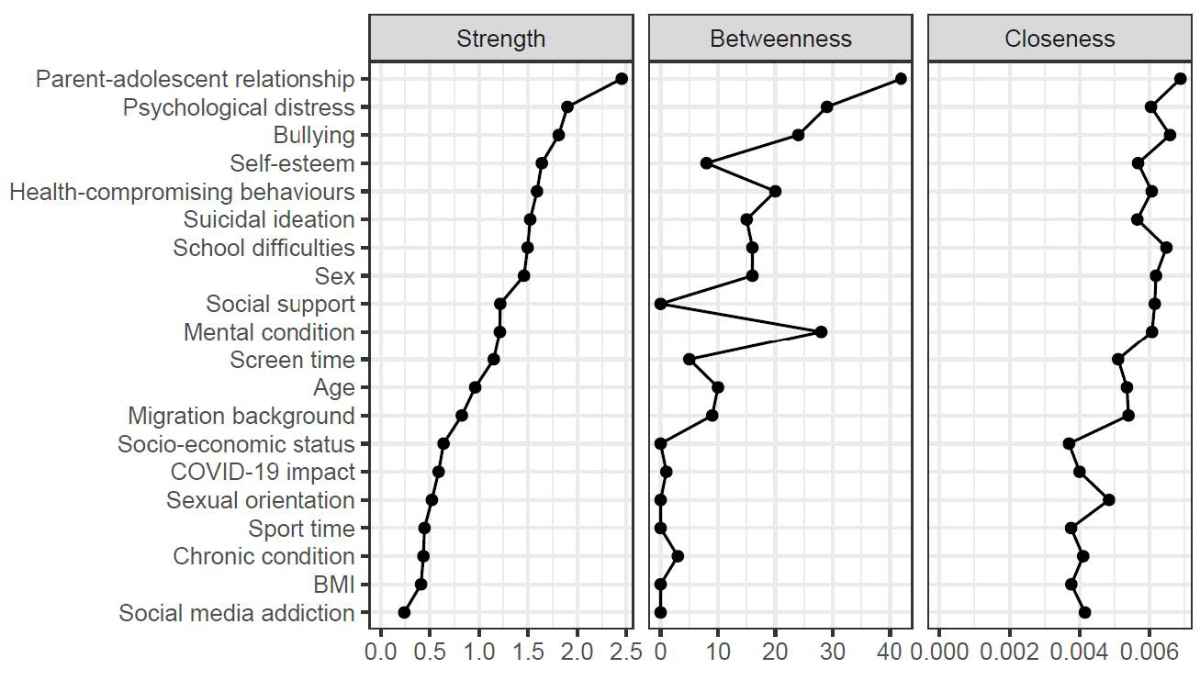

Figure S1 displays the plot for centrality metrics. The nodes with the strongest centrality (larger node’s size in figure 2) were parent-adolescent relationship, psychological distress, bullying, self-esteem and health-compromising behaviours, followed by suicidal ideation. These factors had a strong global influence on the overall network structure. Additional information on centrality measures can be found in figure S1 in the appendix. The stability of the edges is presented and commented on in figures S2, S3 and S4 in the appendix.

A logistic regression was also conducted (table 3) and confirmed the main risk factors for suicidal ideation: strong psychological distress (aOR 5.87, 95% CI: 2.73–13.07), low self-esteem (aOR 1.43, 95% CI: 1.01–4.20), identifying as LGB (aOR 2.52, 95% CI: 1.02–6.10) and excessive screen time (aOR 1.18, 95% CI: 1.04–1.33). We observed near-significance for experiencing bullying (aOR 1.60, 95% CI 0.96–3.34) and COVID-19 pandemic negative impact (aOR 1.48, 95% CI: 0.98–3.43).

Table 3Risk factors for suicidal ideation among adolescents using logistic regression.

| Suicidal ideation vs no suicidal ideation | Univariate model | Multivariate model | ||

| OR (95% CI, p value) | aOR (95% CI, p value) (n = 444) | |||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Sex | Female | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| Male | 0.32 (0.18–0.55, p <0.001) | 1.32 (0.57–3.08, p = 0.519) | ||

| Other | – | – | ||

| Age (years) | 1.15 (0.93–1.42, p = 0.196) | 0.92 (0.68–1.23, p = 0.566) | ||

| Household financial situation | Good | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | |

| Average to poor | 1.71 (0.89–3.16, p = 0.096) | 1.01 (0.39–2.29, p = 0.937) | ||

| No answer | 0.67 (0.16–1.99, p = 0.528) | 0.55 (0.09–2.65, p = 0.475) | ||

| Migrant status | No | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | |

| Yes | 0.86 (0.36–1.80, p = 0.706) | 0.76 (0.27–1.96, p = 0.586) | ||

| Health characteristics | Chronic health condition | No | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| Yes | 1.48 (0.89–2.46, p = 0.128) | 0.99 (0.47–2.02, p = 0.971) | ||

| Mental health problem | No | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | |

| Yes | 2.06 (1.11–3.70, p = 0.018) | 1.24 (0.51–2.86, p = 0.628) | ||

| Other characteristics | Sexual orientation | Heterosexual | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| LGB | 6.34 (3.41–11.79, p <0.001) | 2.52 (1.02–6.10, p = 0.041)* | ||

| Did not know | 1.68 (0.80–3.34, p = 0.151) | 1.15 (0.40–3.11, p = 0.791) | ||

| Parent-adolescent relationship | Bad | |||

| Good | 0.29 (0.16–0.54, p <0.001) | 0.83 (0.34–2.06, p = 0.680) | ||

| Psychological characteristics | Psychological distress | Low | ||

| High | 11.26 (6.47–20.23, p <0.001) | 5.87 (2.73–13.07, p <0.001)** | ||

| Self-esteem | High | |||

| Low | 8.48 (4.30–16.85, p <0.001) | 1.43 (0.97–4.20, p = 0.052) | ||

| Social support | Strong | |||

| Moderate to poor | 2.89 (1.68–4.92, p <0.001) | 2.13 (0.96–4.68, p = 0.059) | ||

| Schooling | School difficulties | No | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| Yes | 2.45 (1.36–4.32, p = 0.002) | 0.86 (0.33–2.08, p = 0.739) | ||

| Victim of bullying | No | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | |

| Yes | 4.37 (2.60–7.44, p <0.001) | 1.60 (0.96–3.34, p = 0.08) | ||

| Social media addiction | Social media addiction (score) | 1.12 (1.05–1.19, p = 0.001) | 1.03 (0.93–1.13, p = 0.581) | |

| Daily screen time | 1.18 (1.10–1.27, p <0.001) | 1.18 (1.04–1.33, p = 0.010)* | ||

| Health-compromising behaviours | Smoking | No | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| Yes | 6.19 (2.98–12.75, p <0.001) | 2.47 (0.76–7.84, p = 0.126) | ||

| Alcohol consumption | No | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | |

| Yes | 3.23 (1.26–7.67, p = 0.010) | 1.94 (0.38–8.78, p = 0.404) | ||

| Drug use | No | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | |

| Yes | 1.19 (0.06–7.55, p = 0.872) | 0.43 (0.01–7.46, p = 0.594) | ||

| COVID-19 pandemic impact | COVID-19 pandemic impact | No | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| Yes | 3.18 (1.73–5.73, p <0.001) | 1.48 (0.98–3.43, p = 0.07) | ||

* indicates p value <0.05.

** indicates p value <0.01.

In this population-based sample, 1 out of 7 adolescents reported having experienced suicidal ideation over the last 12 months. Through network analysis, we identified direct and indirect risk factors. Our analysis also revealed that parent-adolescent relationship, psychological distress and bullying had the highest centrality strength in the network, which underlined a substantial influence on the network information flow.

Our study estimated the prevalence of suicidal ideation in adolescents to be 14%, which is comparable with pre-pandemic estimates reported in the literature on suicidal ideation in this age range. Indeed, in a pre-pandemic comparison across 82 countries, the overall 12-month pooled prevalence of suicidal ideation among 12 to 17 year olds was 14.0% [5]. However, when stratifying per region, the prevalence in European adolescents was estimated to be 11.0%, which is slightly lower than our estimates. The SMASH Study conducted in Switzerland in 2002 reported a similar level of suicidal ideation in female adolescents, but a higher prevalence in males [22].

Adolescence is a critical developmental stage of life marked by rapid social, emotional and biological changes that can expose adolescents to mental health problems driven by social exclusion, bullying, violence, break-up of family relationships, educational difficulties and health-compromising behaviours [4]. Psychological distress was reported by 25% of adolescents in this sample, in line with estimates from the World Health Organization [32], and was identified as the main risk factor for suicidal ideation. In turn, the risk factors for psychological distress identified in our study, namely female sex, low self-esteem and excessive use of social media, are consistent with previous research [9, 33].

Our study also revealed that adolescents who self-identified as gay, lesbian or bisexual reported a significantly higher prevalence of suicidal ideation compared to adolescents who self-identified as heterosexual. This result sheds light on the strong disparities existing between heterosexual and LGB communities in terms of distress and suicidal behaviours, even at an early age. These disparities could be explained by minority stressors such as discrimination, social rejection, lower familial support and bullying [34], and are in line with reports showing that sexual minorities exhibit higher risks of poorer physical and psychological health [8]. Interestingly, the network also confirmed the strong relationship between identifying as LGB and bullying [35].

Another important vector of suicidal ideation and psychological distress identified in the network was self-esteem, including its social, academic, family, emotional and physical dimensions, highlighted by the cluster algorithm in figure 2 [36]. Overall, low self-esteem was reported by 8.3% of the sample. Causality could be bidirectional: low self-esteem could lead to depressive behaviours and, conversely, depressive behaviours could be the cause of negative self-evaluation. Thus, self-esteem and psychological distress during adolescence appear to be strongly associated and to have a reciprocal relationship. The network analysis also suggested that feeling surrounded by loved ones, having a positive relationship with parents and not experiencing school difficulties likely increase one’s self-esteem.

Excessive screen time was also identified as a strong risk factor for suicidal ideation in the network. With the increasing use of screens in daily life, including for school activities, the effects of prolonged screen time on adolescent mental and physical health [37] have become a growing concern, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic [38].

In accordance with recent research [39], addiction to social media has been identified as a strong risk factor for psychological distress in the network. The role of social media on adolescent wellbeing is complex. Excessive use of social media can reinforce poor self-esteem, narcissistic behaviours and loneliness, often triggered by comparison with others, isolation, decrease in face-to-face peer interactions and exacerbation of the “fear of missing out” feeling, also known as FOMO, which refers to the perception that others are living better lives or experiencing better things [40, 41]. It can also increase self-harm and psychological distress [42]. Additionally, intensive social media use can lead to greater exposure to cyberbullying, “trolling” and other abusive online behaviours with a potentially dramatic impact on adolescents’ lives, even leading to suicide [43, 44], as confirmed by the network in which bullying in general (cyberbullying and bullying) was identified as a major risk factor for suicidal ideation.

The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly affected the lives of many individuals, particularly young ones. However, the extent to which it has impacted suicidal behaviours remains unclear. Our network analysis highlights that adolescents who had been severely impacted by the pandemic reported more suicidal ideation, although the association was relatively moderate. Sanitary restrictions and successive lockdowns likely had a negative and sustained impact on known risk factors for lower psychological wellbeing, even more so in vulnerable and minority groups including children with chronic conditions, migrants and the LGBT+ community.

Even though an increase in demand for psychological services has been reported [16, 45], our prevalence estimate of suicidal ideation is comparable to pre-pandemic data. This suggests that suicidal ideation may not have increased over the last two years but remained as alarming as before the COVID-19 pandemic. The discrepancy between the frequencies of psychiatric consultations and suicidal ideation could be two-fold. First, it is possible that adolescents with psychiatric disorders were underrepresented in our sample, hence we might be underestimating suicidal ideation. Second, the pandemic raised awareness of adolescents’ mental health via extensive media coverage. This coverage may have encouraged parents and adolescents to call for psychological support [46].

This highlights the need to keep monitoring the prevalence of suicidal ideation over time, and to dedicate resources to prevention and screening for psychological distress [47]. Public effort is particularly needed in view of the current high and unmet demand for psychological services for young people. Timely detection of suicidal ideation and the early detection of high-risk subgroups could play a pivotal role in preventing suicide.

A number of strategies are already in place to try to reduce suicidal behaviours in youth such as online resources with healthcare professionals, or school and social media prevention campaigns [48]. Our analysis identified several highly influential domains, suggesting that preventive measures might be focused on improving parent-adolescent relationships, supporting victims of bullying and preventing health-compromising behaviours as these domains seem to be key in adolescence.

The major strength of our study is the population-based design, covering many life dimensions of 492 adolescents, and the use of validated psychometric scales. In addition, to the best of our knowledge, this is one of the few studies investigating suicidal ideation in population-based samples of adolescents since the beginning of the pandemic. Also, the use of network analysis based on mixed graphical models allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the complex relationships[10].Network analysis is a very powerful tool for visualising data and highlighting relevant associations, complementing the more classic regression analysis. Additionally, mixed graphical models enable robust parameter estimation, accommodating both continuous and discrete data. Our study also has several limitations. First, the measure of suicidal ideation used in the study might suffer from a measurement bias: some adolescents may have reported suicidal ideation but not seriously considered it. On the other hand, some adolescents might have not reported it due to social conformity and response bias. Also, we lack recent pre-pandemic data in the same population with similar study design to estimate how suicidal behaviours were impacted by the pandemic. Despite being an attractive tool for studying multivariate data [31], network analysis with mixed graphical estimation also presents limitations, including instability in data-driven estimated edges, selection of nodes, lack of causal interpretation, interpretability and computational challenges. These limitations were addressed with intensive literature review for node selection, careful interpretation of results and confirmation of the main results by a logistic regression model. Furthermore, our statistical power was limited by the sample size. Finally, as commonly observed in such studies, vulnerable adolescents, and those from households with lower socioeconomic conditions were less likely to participate in the study. Although no difference in suicidal ideation by household socioeconomic characteristics was observed, other social determinants of mental health play a substantial role and therefore the prevalence might be underestimated.

Our study highlights that 1 out of 7 adolescents in Geneva, Switzerland, reported suicidal ideation over the previous year. This estimate is comparable to pre-pandemic data. Preventive efforts are needed particularly among vulnerable and minority groups, who accumulate risk factors for suicidal ideation. Sustained monitoring is required to study long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, with a focus on improving parent-adolescent relationships.

Participants’ informed consent did not authorise data to be immediately publicly available. It does allow, however, for the data to be made available to the scientific community upon submission of a data request application to the investigator board via the corresponding author. A response will be provided to all requests for data within three months of submission.

SEROCoV-KIDS study group: Deborah Amrein, Andrew S Azman, Antoine Bal, Julie Berthelot, Patrick Bleich, Livia Boehm, Gaëlle Bryand, Viola Bucolli, Prune Collombet, Vladimir Davidovic, Carlos de Mestral Vargas, Paola D'Ippolito, Richard Dubos, Isabella Eckerle, Marion Favier, Nacira El Merjani, Natalie Francioli, Clément Graindorge, Séverine Harnal, Samia Hurst, Laurent Kaiser, Omar Kherad, Pierre Lescuyer, Arnaud G. L’Huillier, Chantal Martinez, Stéphanie Mermet, Mayssam Nehme, Natacha Noël, Javier Perez-Saez, Anne Perrin, Didier Pittet, Jane Portier, Géraldine Poulain, Caroline Pugin, Nick Pullen, Frederic Rinaldi, Jessica Rizzo, Deborah Rochat, Cyril Sahyoun, Irine Sakvarelidze, Khadija Samir, Hugo Alejandro Santa Ramirez, Stephanie Schrempft, Claire Semaani, Stéphanie Testini, Yvain Tisserand, Deborah Urrutia Rivas, Charlotte Verolet, Jennifer Villers, Guillemette Violot, Nicolas Vuilleumier, Sabine Yerly, Christina Zavlanou

Author Contributions: RD, IG, SS, and EL conceptualized and designed the study, carried out the initial analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. AL, MEZ, FP, VR, JL, HB designed the data collection instruments, collected data, carried out the initial analyses, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. DDR and GF carried out statistical analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, and revised the manuscript. RB and KPBcritically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have read, critically revised and approved the final version of this manuscript.

We thank the Jacobs foundation and the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) for supporting the project. We are grateful to the staff of the Unit of Population Epidemiology of the HUG Division of Primary Care Medicine, the SEROCoV-KIDS study group and all participants whose contributions were invaluable to the study. We also warmly thank Professor David Brent for his precious help in interpreting the results.

This project is funded by the Jacobs Foundation, the Federal Office of Public Health, the General Directorate of Health of the canton of Geneva and the Private Foundation of the Geneva University Hospitals.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript was disclosed.

1. Suicide worldwide in 2019: global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240026643

2. Klonsky ED, Qiu T, Saffer BY. Recent advances in differentiating suicide attempters from suicide ideators. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017 Jan;30(1):15–20. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000294

3. Klonsky ED, May AM. Differentiating suicide attempters from suicide ideators: a critical frontier for suicidology research. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014 Feb;44(1):1–5. 10.1111/sltb.12068

4. Sawyer SM, Afifi RA, Bearinger LH, Blakemore SJ, Dick B, Ezeh AC, et al. Adolescence: a foundation for future health. Lancet. 2012 Apr;379(9826):1630–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5

5. Biswas T, Scott JG, Munir K, Renzaho AM, Rawal LB, Baxter J, et al. Global variation in the prevalence of suicidal ideation, anxiety and their correlates among adolescents: A population based study of 82 countries. EClinicalMedicine. 2020 Jun;24:100395. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100395

6. McKinnon B, Gariépy G, Sentenac M, Elgar FJ. Adolescent suicidal behaviours in 32 low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2016 May;94(5):340–350F. 10.2471/BLT.15.163295

7. Donath C, Bergmann MC, Kliem S, Hillemacher T, Baier D. Epidemiology of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and direct self-injurious behavior in adolescents with a migration background: a representative study. BMC Pediatr. 2019 Feb;19(1):45. 10.1186/s12887-019-1404-z

8. Liu RT, Walsh RF, Sheehan AE, Cheek SM, Carter SM. Suicidal Ideation and Behavior Among Sexual Minority and Heterosexual Youth: 1995-2017. Pediatrics. 2020 Mar;145(3):e20192221. 10.1542/peds.2019-2221

9. Berryman C, Ferguson CJ, Negy C. Social Media Use and Mental Health among Young Adults. Psychiatr Q. 2018 Jun;89(2):307–14. 10.1007/s11126-017-9535-6

10. De Beurs D. Network analysis: a novel approach to understand suicidal behaviour. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(3):219. 10.3390/ijerph14030219

11. Suh WY, Lee J, Yun JY, Sim JA, Yun YH. A network analysis of suicidal ideation, depressive symptoms, and subjective well-being in a community population. J Psychiatr Res. 2021 Oct;142:263–71. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.08.008

12. Hoekstra PJ. Suicidality in children and adolescents: lessons to be learned from the COVID-19 crisis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020 Jun;29(6):737–8. 10.1007/s00787-020-01570-z

13. Farooq S, Tunmore J, Wajid Ali M, Ayub M. Suicide, self-harm and suicidal ideation during COVID-19: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2021 Dec;306:114228. 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114228

14. Woo HG, Park S, Yon H, Lee SW, Koyanagi A, Jacob L, et al. National Trends in Sadness, Suicidality, and COVID-19 Pandemic-Related Risk Factors Among South Korean Adolescents From 2005 to 2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 May;6(5):e2314838. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.14838

15. Dubé JP, Smith MM, Sherry SB, Hewitt PL, Stewart SH. Suicide behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis of 54 studies. Psychiatry Res. 2021 Jul;301:113998. 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113998

16. Engagement politique | Pro Juventute [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 5]. Available from: https://www.projuventute.ch/fr/fondation/actualite/engagement-politique

17. Stringhini S, Wisniak A, Piumatti G, Azman AS, Lauer SA, Baysson H, et al. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in Geneva, Switzerland (SEROCoV-POP): a population-based study. Lancet. 2020 Aug;396(10247):313–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31304-0

18. Stringhini S, Zaballa ME, Perez-Saez J, Pullen N, de Mestral C, Picazio A, et al.; Specchio-COVID19 Study Group. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies after the second pandemic peak. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 May;21(5):600–1. 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00054-2

19. Stringhini S, Zaballa ME, Pullen N, Perez-Saez J, de Mestral C, Loizeau AJ, et al.; Specchio-COVID19 study group. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies 6 months into the vaccination campaign in Geneva, Switzerland, 1 June to 7 July 2021. Euro Surveill. 2021 Oct;26(43):2100830. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.43.2100830

20. Zaballa ME, Perez-Saez J, de Mestral C, Pullen N, Lamour J, Turelli P, et al. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and cross-variant neutralization capacity after the Omicron BA. 2 wave in Geneva, Switzerland: A population-based study. Lancet Reg Heal. 2022;

21. Baysson H, Pennachio F, Wisniak A, Zabella ME, Pullen N, Collombet P, et al.; Specchio-COVID19 study group. Specchio-COVID19 cohort study: a longitudinal follow-up of SARS-CoV-2 serosurvey participants in the canton of Geneva, Switzerland. BMJ Open. 2022 Jan;12(1):e055515. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055515

22. Narring F, Tschumper A, Inderwildi Bonivento L, Jeannin A, Addor V, Bütikofer A, et al. Santé et styles de vie des adolescents âgés de 16 à 20 ans en Suisse (2002). SMASH 2002: swiss multicenter adolescent survey on health 2002. Lausanne: Institut universitaire de médecine sociale et préventive (IUMSP …; 2004.

23. Deschesnes M. Étude de la validité et de la fidélité de l’Indice de détresse psychologique de Santé Québec (IDPSQ-14), chez une population adolescente [Study of the validity and the reliability of The Quebec Health Department’s Psychological Distress Index (IDPSQ-14) in an adolescent population.]. Can Psychol Psychol Can. 1998;39(4):288–98. 10.1037/h0086820

24. Vallieres EF, Vallerand RJ. Traduction et validation canadienne-française de l’échelle de l’estime de soi de Rosenberg. Int J Psychol. 1990;25(2):305–16. 10.1080/00207599008247865

25. Schou Andreassen C, Billieux J, Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, Demetrovics Z, Mazzoni E, et al. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016 Mar;30(2):252–62. 10.1037/adb0000160

26. Lucia S, Stadelmann S, Ribeaud D, Gervasoni JP. Enquêtes populationnelles sur la victimisation et la délinquance chez les jeunes dans le canton de Vaud. Raisons Santé; 2015. p. 250.

27. Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

28. Stoddard J, Reynolds EK, Paris R, Haller S, Johnson S, Zik J, et al. The Coronavirus Impact Scale: construction, validation, and comparisons in diverse clinical samples. 2021; 10.31234/osf.io/kz4pg

29. Epskamp S, Waldorp LJ, Mõttus R, Borsboom D. The Gaussian graphical model in cross-sectional and time-series data. Multivariate Behav Res. 2018;53(4):453–80. 10.1080/00273171.2018.1454823

30. Haslbeck J, Waldorp LJ. mgm: Estimating time-varying mixed graphical models in high-dimensional data. ArXiv Prepr ArXiv151006871. 2015;

31. Borsboom D, Deserno MK, Rhemtulla M, Epskamp S, Fried EI, McNally RJ, et al. Network analysis of multivariate data in psychological science. Nat Rev Methods Primers. 2021;1(1):1–18. 10.1038/s43586-021-00055-w

32. Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, Rohde LA. Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015 Mar;56(3):345–65. 10.1111/jcpp.12381

33. Orth U, Robins RW. Understanding the link between low self-esteem and depression. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2013;22(6):455–60. 10.1177/0963721413492763

34. Fox KR, Choukas-Bradley S, Salk RH, Marshal MP, Thoma BC. Mental health among sexual and gender minority adolescents: examining interactions with race and ethnicity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2020 May;88(5):402–15. 10.1037/ccp0000486

35. Amos R, Manalastas EJ, White R, Bos H, Patalay P. Mental health, social adversity, and health-related outcomes in sexual minority adolescents: a contemporary national cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020 Jan;4(1):36–45. 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30339-6

36. Fiske ST, Gilbert DT, Lindzey G. Handbook of Social Psychology. Volume 2. John Wiley & Sons; 2010. 10.1002/9780470561119

37. Guo Y feng, Liao M qi, Cai W li, Yu X xuan, Li S na, Ke X yao, et al. Physical activity, screen exposure and sleep among students during the pandemic of COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–11.

38. Pandya A, Lodha P. Social connectedness, excessive screen time during COVID-19 and mental health: a review of current evidence. Front Hum Dyn; 2021. p. 3.

39. Beyens I, Pouwels JL, van Driel II, Keijsers L, Valkenburg PM. The effect of social media on well-being differs from adolescent to adolescent. Sci Rep. 2020 Jul;10(1):10763. 10.1038/s41598-020-67727-7

40. Andreassen CS, Pallesen S, Griffiths MD. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: findings from a large national survey. Addict Behav. 2017 Jan;64:287–93. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006

41. Barry CT, Sidoti CL, Briggs SM, Reiter SR, Lindsey RA. Adolescent social media use and mental health from adolescent and parent perspectives. J Adolesc. 2017 Dec;61(1):1–11. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.08.005

42. McCrae N, Gettings S, Purssell E. Social Media and Depressive Symptoms in Childhood and Adolescence: A Systematic Review. Adolesc Res Rev. 2017 Dec;2(4):315–30. 10.1007/s40894-017-0053-4

43. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Social influences on cyberbullying behaviors among middle and high school students. J Youth Adolesc. 2013 May;42(5):711–22. 10.1007/s10964-012-9902-4

44. Memon AM, Sharma SG, Mohite SS, Jain S. The role of online social networking on deliberate self-harm and suicidality in adolescents: A systematized review of literature. Indian J Psychiatry. 2018;60(4):384–92. 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_414_17

45. Berger G, Häberling I, Lustenberger A, Probst F, Franscini M, Pauli D, et al. The mental distress of our youth in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Swiss Med Wkly. 2022 Feb;152(708):152. 10.4414/SMW.2022.w30142

46. Radez J, Reardon T, Creswell C, Lawrence PJ, Evdoka-Burton G, Waite P. Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021 Feb;30(2):183–211. 10.1007/s00787-019-01469-4

47. Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Jun;7(6):547–60. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

48. MALATAVIE. où que tu sois, on entend ton appel | Malatavie [Internet]. [cited 2022 May 16]. Available from: https://www.malatavie.ch/

Table S1Description of main measurements.

| Measurements | Scale | Self- or parent-reported | Questions/items | Comments | |

| Socioeconomic characteristics | |||||

| Sex | Parent-reported | 1) Female, 2) Male, 3) Other | – | ||

| Mother’s education [1] | – | Parent-reported | 1) Primary education (compulsory schooling), 2) Secondary education (apprenticeship and high school), 3) Tertiary education (university) | – | |

| Household financial status | – | Parent-reported | 1) I cannot cover my needs with my income and I need external support, 2) I have to be careful with my expenses and an unexpected event could put me into financial difficulty, 3) My income covers my expenses and covers any minor contingencies, 4) I am comfortably off, money is not a concern and it is easy for me to save. | Household financial status was considered average to poor if the parent selected statements 1 and 2; otherwise it was considered good. | |

| Migration status [2] | – | Parent-reported | Born in Switzerland or not | – | |

| Health characteristics | |||||

| Body mass index (BMI) | – | Parent-reported | Weight, height | Adolescent’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in metres | |

| Chronic health condition | – | Parent-reported | Physical or mental condition diagnosed by a health professional that lasted (or was expected to last) longer than 6 months | ||

| Health behaviours | |||||

| Health-compromising behaviours [3] | – | Adolescent-reported | Adolescents were asked if they were currently smoking, drinking or taking drugs. | Yes when answers were every day or every week. | |

| Screen time | Adolescent-reported | Adolescent-reported number of hours spent with a screen per day. | – | ||

| Physical activity time | Adolescent-reported | Adolescent-reported number of hours spent doing physical activity per day. | – | ||

| School | |||||

| School difficulties | – | Adolescent-reported | I do not like to study | At least one item checked | |

| I have trouble concentrating | |||||

| I’m bored in class | |||||

| I have family problems | |||||

| There are financial difficulties in the family | |||||

| I have health problems | |||||

| I can’t see or hear well in class | |||||

| I can’t express myself as I would want | |||||

| I have problems understanding instructions in class | |||||

| I have the impression that the programme is going too fast in class | |||||

| I do not understand the language spoken in class well | |||||

| I feel uncomfortable in my class | |||||

| COVID-19 experience | |||||

| COVID-19 impact (EN) [4] | Coronavirus impact scale | Parent-reported | Pandemic impact in terms of routine, income, food access, physical and mental healthcare access, access to social and family support, stress and family discord on a 4-point Likert scale (no change, mild, moderate, severe). | We summed the 8 items of the Coronavirus impact scale, a higher score indicating a more severe impact. | |

| Serological test [5] | Roche Elecsys anti-SARS-CoV-2 N | Laboratory results | – | Roche Elecsys anti-SARS-CoV-2 N, detecting total Ig (including IgG) against the nucleocapsid protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Seropositivity was defined using the manufacturer’s cut-off index of ≥1.0. | |

| Psychological characteristics | |||||

| Psychological distress (FR) [6] | Psychological Distress Index | Adolescent-reported | 11 items | The score ranges from 0 to 70; scores over 30 suggest high psychological distress. | |

| Suicidal ideation (FR) [7] | – | Adolescent-reported | Over the last year, have you thought about suicide? | Yes/No | |

| Self-esteem (FR) [8] | Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem | Adolescent-reported | 6 items | The scale ranges from 10 to 40, and scores below 25 suggest low self-esteem. | |

| Perceived social support (FR) [9] | Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support | Adolescent-reported | 12 items | It is summarised as a mean score across 12 items; higher scores correspond to higher levels of social support. A score lower than 2.9 would be considered as having low social support; a score of 3.0 to 5.0 would be moderate support and 5.1 to 7 would be high support. | |

| Parent/adolescent relationship [10] | – | Adolescent-reported | Adolescents were asked to describe their relationship with their parents on a 5-point Likert scale. | The variable was dichotomised: if the adolescent answered “average”, “rather bad” or “bad” the relationship was defined as average to poor, while it was characterised as good for answers “good” and “very good”. | |

| Social media addiction | |||||

| Excessive social media (FR) [11] | Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale | Adolescent-reported | 6 items | It consists of six items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very rarely) to 5 (very often) assessing use of social media, overall rather than on one specific platform. | |

| Bullying | |||||

| Bullying [12] | – | Adolescent-reported | 6 items: 1) I have been excluded, ignored, false rumours about me have been spread, 2) I have been humiliated, 3) I have been pushed around/hit, 4) My things have been broken or stolen, 5) I have been threatened, 6) I have been sexually harassed. | At least one of the statements ever happened to them on a weekly or daily basis. | |

| Cyberbullying [13] | – | Adolescent-reported | 6 items: 1) Photos or videos of you have been posted online without your consent, 2) You have been approached online by a stranger with unwanted sexual intentions, 3) Someone has threatened you (e.g. message on Instagram/Facebook), 4) Unpleasant pictures or messages about you have been sent to your cell phone or computer, 5) Offensive or false information about you has been published on the Internet. | At least one of the statements ever happened to them on a weekly or daily basis. | |

| Other characteristics | |||||

| Sexual orientation | – | Adolescent-reported | (1) Heterosexual, (2) Lesbian, gay, bisexual (LGB), (3) No answer, for those who did not want to answer/did not know. | – | |

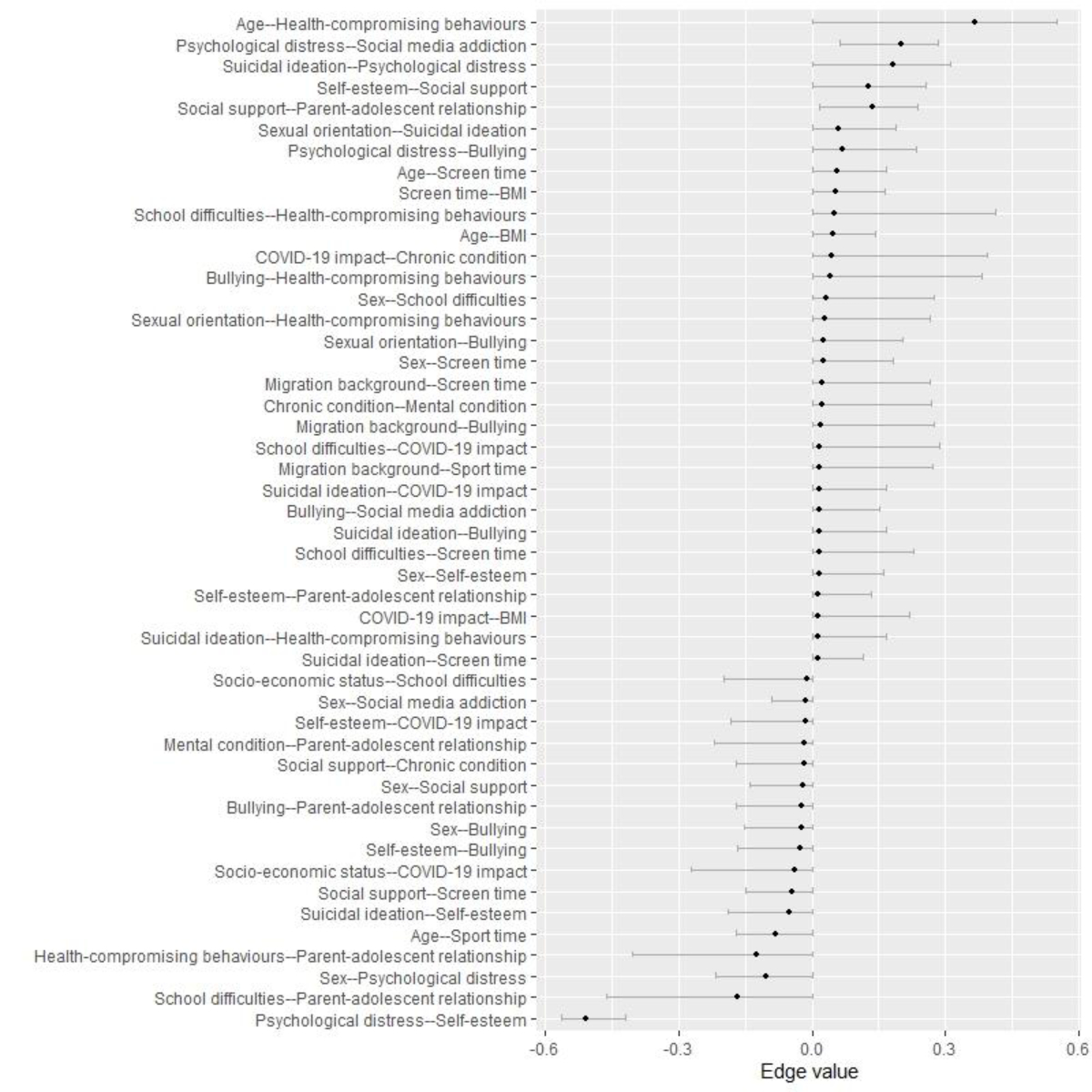

Figure S1Centrality plots of the network including suicidal ideation and related risk factors. Centrality measurements quantify the influence of nodes within a network. They estimate how central a node is given the network’s topology. Strength centrality measures the local influence of a node within a network. It is calculated as the sum of the absolute edge weights per node. In other words, it looks at the total weight of the edges coming into and out of a node. The nodes with the strongest strength centrality are parent-adolescent relationship, psychological distress and bullying, hence they have strong local influence on the overall network structure. Betweenness centrality is a measure of how often a node lies on the shortest path connecting any two other nodes, while normalising by the total number of possible paths between all other nodes. A node with high betweenness centrality is a bridge between different clusters of risk factors within the network. Parent-adolescent relationship, psychological distress and mental condition had the highest betweenness centrality measure. Closeness centrality is a measure of how close a node is to all other nodes in the network. It is calculated by averaging the shortest path length to all other nodes. A node with high closeness centrality indicates a node directly and indirectly well connected to all other nodes. Parent-adolescent relationship, bullying and school difficulties have the highest closeness centrality.

Figure S2Bootstrapping of robustness and edges of stability networks. The Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection (LASSO) regularisation was used to identify important edges in the network. The edges that were not set to zero indicate that the edge is strong enough to be included in the network. This figure also shows the accuracy of the edge weights and allows for comparison of edges. However, it should be noted that the majority of the edges have overlapping confidence intervals, meaning that it is difficult to determine the order of the edge weights. Thus, we cannot claim that one edge value is significantly larger than another, except for the edge between psychological distress and self-esteem, which shows a significantly negative connection.

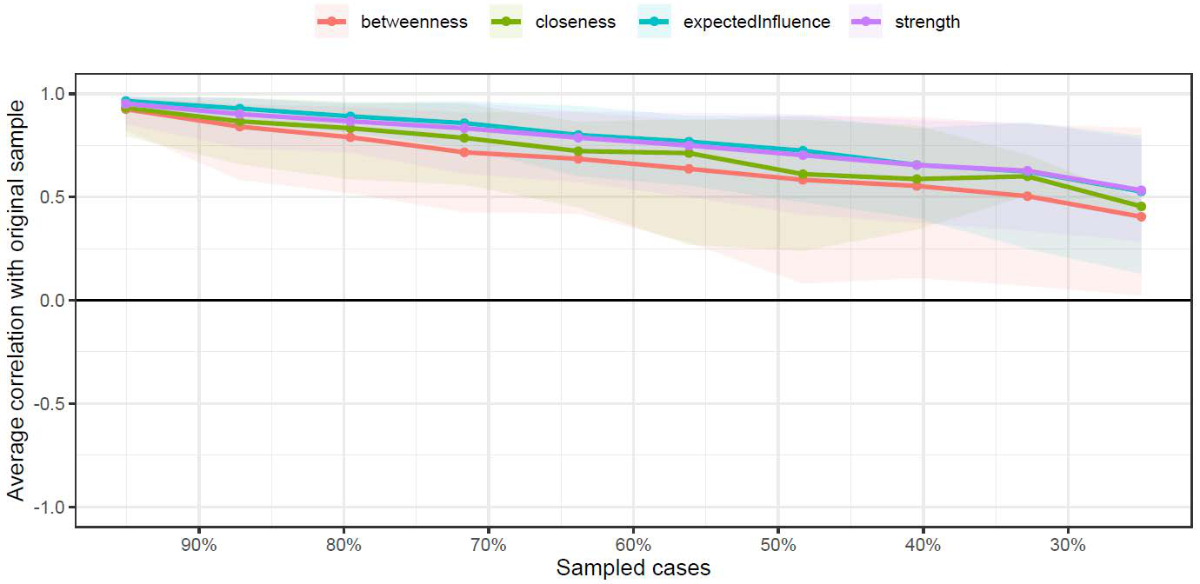

Figure S3Correlation-Stability (CS) coefficient. The figure illustrates the CS coefficient for the centrality measurements, which is used to assess how sensitive the centrality measures are to the proportion of dropped cases. The X axis shows the percentage of cases from the sample and the Y axis shows the correlation between the observed centrality measure and the computed centrality measure with the related proportion of dropped cases. The shaded area indicates 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals of correlation estimates. The centrality measures are considered stable if the CS at the correlation of 0.7 is equal or above 0.5 (i.e. that even by dropping 50% of cases we find a correlation of 0.7). In this case, the rule-of-thumb threshold is not reached, which calls for careful interpretation of the order of the centrality measures. However, it does not alter the interpretation of node centrality as centrality is highly dependent on edge weights, and LASSO regularisation ensures the existence of the edges. Moreover, the stability is affected by the sample size, and thus increasing the sample size may increase the stability of the centrality measures.

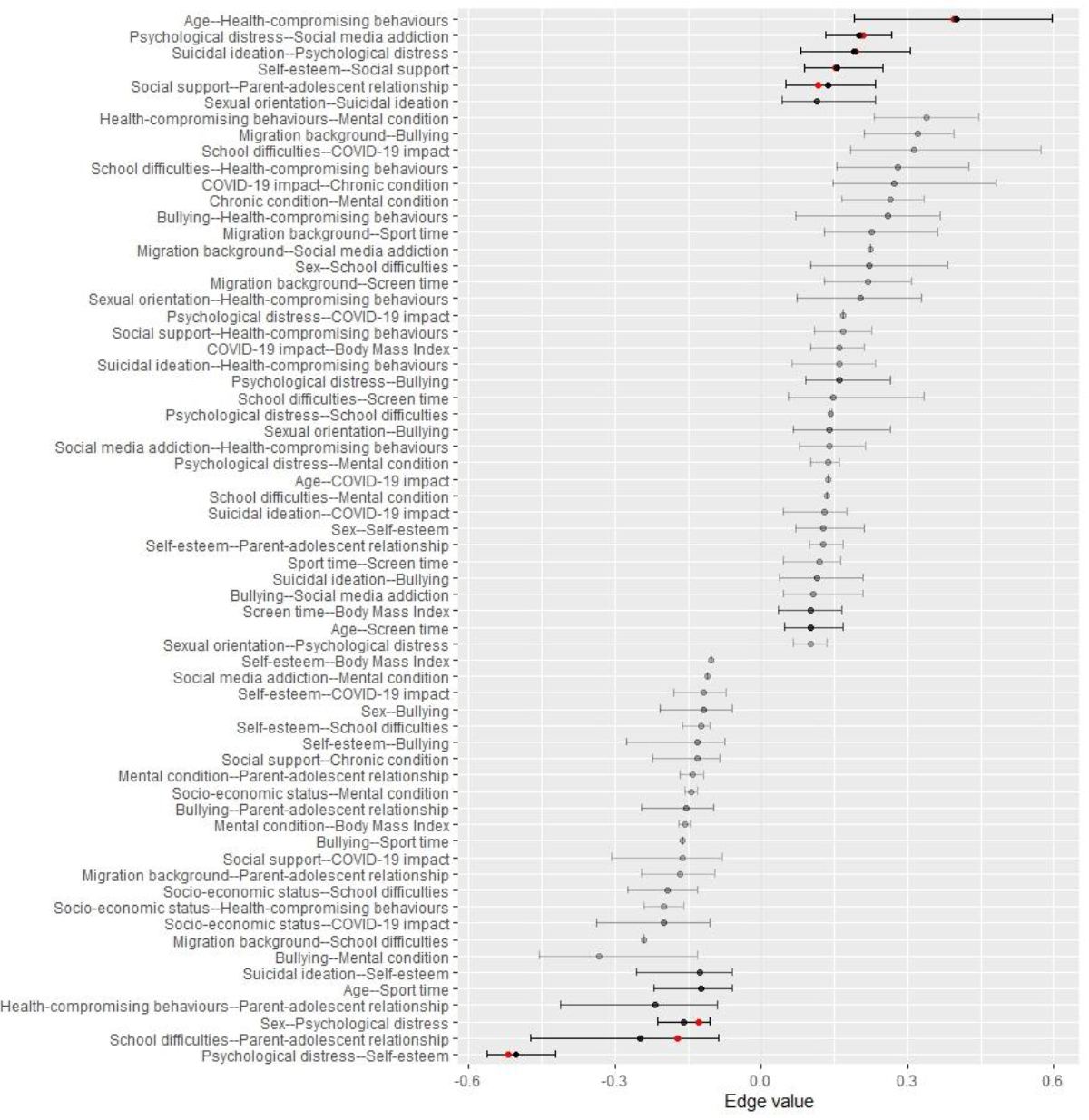

Figure S4Robustness of the estimated edge weights. This figure shows how robust the observed edge weights are when compared to the edge weights obtained through bootstrapping. The red dots indicate the observed edge weights and the black dots with the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) indicate the edge weights obtained through 800 bootstrapped simulations. The fact that the observed edge weights systematically fall within the CIs provides confidence in the accuracy of the measures. Edges equal to 0 were removed.