Interdisciplinary Swiss consensus recommendations on staging and treatment of advanced

prostate cancer

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/smw.2023.40108

Arnoud J. Templetonab,

Aurelius Omlincd,

Dominik Bertholde,

Jörg Beyerf,

Irene A. Burgerg,

Daniel Eberlih,

Daniel Engeleri,

Christian Fankhauserj,

Stefanie Fischerk,

Silke Gillessenl,

Guillaume Nicolasm,

Stephanie Kroezen,

Anja Lorcho,

Michael Müntenerp,

Alexandros Papachristofilouq,

Niklaus Schaeferr,

Daniel Seilers,

Frank Stennert,

Petros Tsantoulisu,

Tatjana Vlajnicvw,

Thomas Zillix,

Daniel Zwahleny,

Richard Cathomasz

a Medical Oncology, St. Claraspital, Basel,

Switzerland / St. Clara Research Ltd., Basel, Switzerland

b Faculty of

Medicine, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

c Onkozentrum Zurich, University of Zurich

d Tumorzentrum Hirslanden Zurich,

Switzerland

e Medical Oncology, CHUV Lausanne, Vaud, Switzerland

f Medical Oncology, Inselspital, Universitätsspital,

Bern, Switzerland

g Department of Nuclear Medicine, Kantonsspital

Baden, Baden, Switzerland

h Department of Urology, Universitätsspital Zürich,

Zurich, Switzerland

i Department of Urology, Kantonsspital St. Gallen,

St. Gallen, Switzerland

j Department of Urology, Luzerner Kantonsspital,

Luzern, Switzerland

k Department of Medical Oncology and Hematology,

Kantonsspital St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland

l Medical Oncology, Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale

(EOC), Bellinzona, Switzerland

m Department of Nuclear Medicine, Universitätsspital

Basel, Basel, Switzerland

n Department of Radio-Oncology, Kantonsspital Aarau,

Aarau, Switzerland

o Medical Oncology and Hematology,

Universitätsspital Zürich, Zurich, Switzerland

p Department of Urology, Stadtspital Zürich Triemli,

Zurich, Switzerland

q Department of Radio-Oncology, Universitätsspital

Basel, Basel, Switzerland

r Department of Visceral Surgery, CHUV, Lausanne,

Vaud, Switzerland

s Department of Urology, Rotes Schloss Zürich,

Zurich, Switzerland

t Medical Oncology and Hematology,

Universitätsspital Basel, Basel, Switzerland

u Medical Oncology and Hematology, Université de

Genève (HUG), Geneva, Switzerland

v Institute of Pathology, Kantonsspital Graubünden,

Chur, Switzerland

w Institute of Medical Genetics and Pathology,

Universitätsspital Basel, Basel, Switzerland

x Department of Radio-Oncology, Ente Ospedaliero

Cantonale (EOC), Bellinzona, Switzerland

y Department of Radio-Oncology, Kantonsspital

Winterthur, Winterthur, Switzerland

z Division of Oncology/Hematology, Kantonsspital

Graubünden, Chur, Switzerland

Summary

The management of prostate

cancer is undergoing rapid changes in all disease settings. Novel imaging tools

for diagnosis have been introduced, and the treatment of high-risk localized,

locally advanced and metastatic disease has changed considerably in recent

years. From clinical and health-economic perspectives, a rational and optimal use

of the available options is of the utmost importance. While international

guidelines list relevant pivotal trials and give recommendations for a variety

of clinical scenarios, there is much room for interpretation, and several

important questions remain highly debated. The goal of developing a national

consensus on the use of these novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in

order to improve disease management and eventually patient outcomes has

prompted a Swiss consensus meeting. Experts from several specialties, including

urology, medical oncology, radiation oncology, pathology and nuclear medicine,

discussed and voted on questions of the current most important areas of

uncertainty, including the staging and treatment of high-risk localized

disease, treatment of metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC) and use

of new options to treat metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer

(mCRPC).

Introduction

Prostate

cancer remains the most common cancer diagnosed in men and a major cause of

cancer deaths in Switzerland, with around 6,500 men newly diagnosed and 1,400

men dying from prostate cancer

every year (www.krebs.bfs.admin.ch). In recent years, several new diagnostic

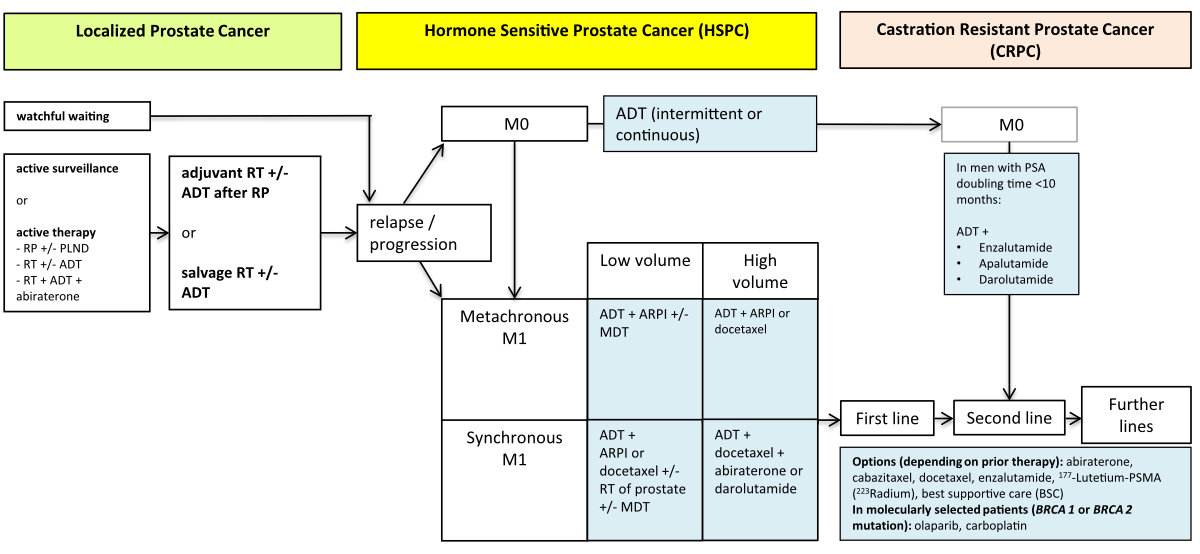

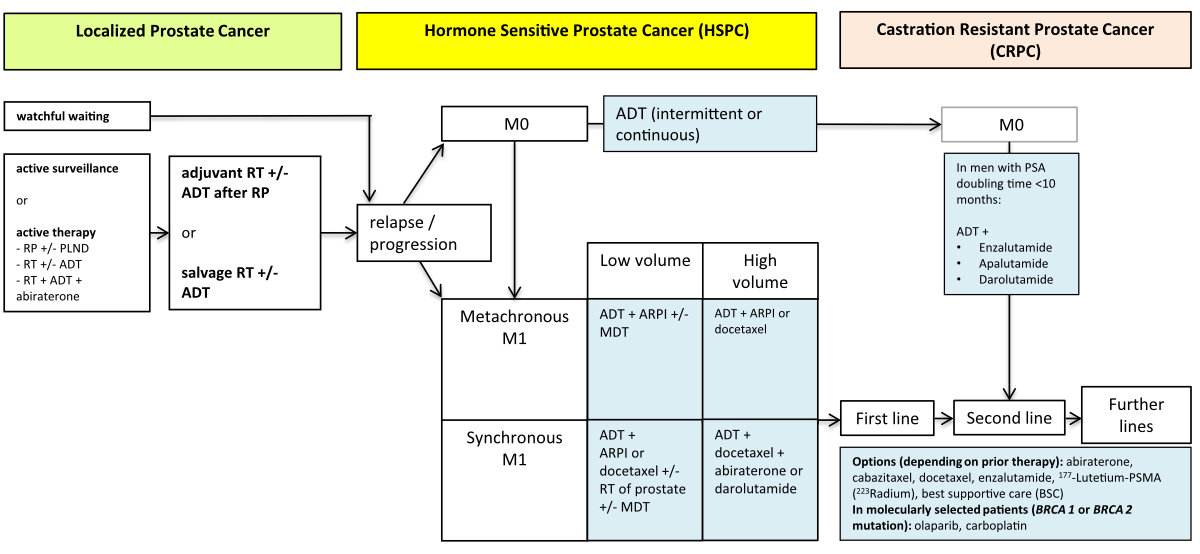

options and treatment strategies have emerged (figure 1). These are broadly

summarized in various international guidelines, but there is much room

for interpretation, and several important questions remain debated. To enhance

patient management and outcomes, a Swiss consensus meeting was held to promote

the coordinated use of innovative diagnostic and therapeutic approaches on a

national scale. The consensus discussion focused on the current most

important areas of uncertainty, including the staging and treatment of

high-risk localized disease, treatment of metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate

cancer (mHSPC) and use of new options to treat metastatic castration-resistant

prostate cancer (mCRPC).

Figure 1The

therapy landscape for prostate cancer, 2023. ADT, androgen deprivation (with LHRH

agonist or

antagonist or bilateral

orchiectomy); ARPI, androgen receptor pathway inhibitor (i.e. abiraterone,

apalutamide, enzalutamide); PLND, pelvic lymph node dissection; M0, no evidence

of distant metastases; M1 evidence of distant metastases; MDT, metastasis

directed therapy. Please refer to https://www.swissmedicinfo.ch for approved indications.

The meeting took place in Bern on November 24, 2022. Most questions were selected

from the 2022 international Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference (APCCC)

[1], but some questions were reformulated to facilitate discussion, and some new questions

were formulated by the corresponding authors. All questions were circulated to all

experts before the meeting to allow participants to prepare. All questions were discussed

and subsequently voted on. All votes were submitted electronically and anonymously.

Consensus was defined as at least 80% of votes favouring a specific answer.

This article summarizes the discussion and voting results and is intended to serve

as guidance for the formulation of recommendations by institutional multidisciplinary

tumour boards and as a basis for discussion with individual patients. However, these

recommendations are not compulsory regulations and cannot replace careful and interdisciplinary

shared decision making with patients while considering important individual-specific

factors (figure 2).

Figure 2Considerations for individual decisions regarding the treatment of metastatic

hormone-sensitive prostate cancer.

Composition of the

panel

The Swiss Group

for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) invited a total of 22 Swiss prostate cancer

experts from different specialties, including urology, radiation oncology,

nuclear medicine, pathology and medical oncology, to join the panel. Experts were

identified using the network of the SAKK project group for urogenital tumours.

Fifteen experts were able to participate in person at the meeting. Participants

were permitted to vote on all questions presented, regardless of possible

conflicts of interest (e.g., authorship of scientific work discussed).

The co-authors Irene A. Burger, Daniel Eberli, Stefanie Fischer, Silke Gillessen,

Guillaume Nicolas, Stephanie Kroeze, Niklaus Schaefer, Thomas Zilli, and Daniel Zwahlen

could not attend the

consensus meeting in person.

Staging of

localized prostate cancer

In the

first part of the consensus meeting, questions involving modern imaging (i.e.,

PSMA [prostate-specific membrane antigen] PET/CT and whole-body MRI) as staging modalities

in localized prostate cancer were

addressed. The possibility of staging at diagnosis using PSMA PET/CT was the centre

of the discussion. There was consensus (86%) that staging with PSMA PET/CT is

indicated in cases of very high-risk or high-risk localized disease, according

to NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network)

definitions (table 1), and one-third of panellists also recommended this method

of staging in cases of unfavourable intermediate risk.

Table 1 Risk stratification according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).

| Risk group |

Clinical/pathological features |

| Very low |

Has all of the following: |

cT1c |

| Gleason 6 (ISUP Grade Group 1) |

| PSA <10 ng/ml |

| <3 prostate

biopsy fragments/cores positive, ≤50% cancer in each fragment/core |

| PSA density <0.15 ng/ml/g |

| Low |

Has all of the

following but does not qualify for very low risk: |

cT1–cT2a |

| Gleason 6 (ISUP

Grade Group 1) |

| PSA <10 ng/ml |

| Intermediate |

Has all of the following: |

No high-risk group features |

| No very high-risk group

features |

| Has one or more intermediate

risk factors: |

cT2b–cT2c |

| Gleason 7 (7a = 3 + 4 or 7b

= 4 + 3) (ISUP Grade Group 2 or 3) |

| PSA 10–20 ng/ml |

| Favourable intermediate |

Has all of the following: |

1 intermediate-risk feature |

| Gleason 6 or 7a (ISUP Grade

Group 1 or 2) |

| <50% biopsy cores

positive (e.g., <6 of 12 cores) |

| Unfavourable intermediate |

Has one or more of the

following: |

2 or 3 intermediate-risk

features |

| Gleason 7b (ISUP

Grade Group 3) |

| ≥50% biopsy cores

positive (e.g., ≥6 of 12 cores) |

| High |

Has no very high-risk

features and has exactly one high-risk feature: |

cT3a OR |

| Gleason 8–10 (ISUP Grade

Group 4 or 5) OR |

| PSA >20 ng/ml |

| Very high |

Has at least one of the

following: |

cT3b–cT4 |

| Primary Gleason

pattern 5 |

| 2 or 3 high-risk features |

| >4 cores with Gleason 8–10

(ISUP Grade Group 4 or 5) |

The

discussion highlighted that the problem of balancing false positive or

ambiguous findings on one hand and sensitivity for locoregional lymph node

metastasis (cN1) and/or distant metastases (cM1) on the other hand is difficult

given that these findings prompt the determination of a curative versus

palliative treatment strategy. Based on the available literature, the

sensitivity and specificity of 18F-PSMA-1007 PET/CT (the tracer most

often used in Swiss institutions) for detection of locoregional lymph node

metastases are 54% and 97%, respectively [2].

A comparative study of conventional staging, both whole-body MRI and 18F-PSMA-1007

PET/CT showed a higher sensitivity and better inter-reader agreement for staging prostate cancer, despite the known

limitation of unspecific bone uptake (UBU) [3,

4]. There are very limited data on the comparison of 18F-PSMA-1007

and 68Ga-PSMA-11, and both radiotracers are used in routine clinical

practice.

The panel

discussed how to proceed in patients with high-risk prostate cancer for whom

radical local treatment (radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy) of the primary

tumour is planned and who have up to three lesions in the bone with low

uptake (as defined by the institution) evident on an upfront 18F-PSMA

PET/CT without a correlate on the CT component. The majority of experts (71%)

felt that, in general, no further investigations are needed in this case. The rationale

is to avoid undertreatment in the case of false positive findings (i.e.,

inadequate local treatment in the case of wrongly assuming distant metastatic

disease). In fact, a recent PSMA PET/CT–guided biopsy study confirmed that

the majority of such lesions are caused by false positive uptake [5]. In contrast,

in the case of intense

uptake (as defined by the institution), only 13% of experts considered this approach

appropriate, whereas two-thirds recommended correlative imaging (usually targeted

MRI), and 20% recommended a biopsy. There was consensus (93%) not to use whole-body

MRI instead of PSMA PET/CT for initial staging.

Initial treatment

of very high-risk localized prostate cancer

Active

treatment with curative intent encompasses radical prostatectomy or external

beam radiation in combination with androgen deprivation therapy. A recent

report from the STAMPEDE platform protocol [6]

found that the addition of abiraterone/prednisone (for 2 years) and androgen

deprivation therapy (for 3 years) to local radiotherapy led to a 9% increase in the

6-year absolute survival

rate in men with locally advanced disease (definition according to STAMPEDE

protocol: cN1 cM0 disease; or cN0 cM0 disease with at least two of the following:

clinical stage T3 or T4, Gleason score

8–10 and prostate-specific antigen [PSA] concentration ≥40 ng/ml). When asked

about the relative preference of surgery versus radiotherapy plus androgen deprivation

therapy and abiraterone in men with cN0 disease with at least two high-risk

criteria, experts showed no preference (40% for both options). If these

patients are treated surgically, experts recommended that this be considered a

first step of a multimodal approach with a high likelihood that postoperative

radiation therapy will be required. In the case of radiotherapy, there was consensus

(87%) to include pelvic lymph nodes in the radiation volume. For men with cN1

cM0 disease detectable by modern imaging, a majority of experts

(60%) favoured radiotherapy with androgen deprivation therapy and abiraterone, whereas

40% opted for surgery with or without

radiotherapy. Notably, three out of four urologists present preferred the

combination of radiotherapy, androgen deprivation therapy and abiraterone in

this situation, possibly reflecting the perceptions that this treatment is best

supported by data and that cN1 likely reflects systemic disease that requires

both local and systemic treatment.

In the

prostate cancer community, there is some controversy regarding further

management in the case of proven lymph node involvement (pN1) following radical

prostatectomy and undetectable PSA. In the absence of high-risk features

(i.e., Gleason 8–10, positive margins [R1] or pT3), there was consensus (92%) to monitor

PSA

and only initiate salvage radiotherapy to the prostate bed and pelvic lymph

node drainage area in cases of PSA increase. In the case of the presence of two

or three of these high-risk features, however, only 43% of experts opted for

monitoring and salvage radiotherapy in cases of PSA increase, whereas 57% were

in favour of adjuvant radiotherapy, and a minority (21%) of those experts suggested

radiotherapy in combination with androgen deprivation therapy. In the case of

three or more positive lymph nodes, the latter approach was favoured by 50% of

experts in the absence and 67% in the presence of high-risk features. When

asked specifically about management of patients following radical prostatectomy (R0)

and extended pelvic

lymph node dissection without lymph node involvement (pN0) and an undetectable

postoperative PSA with a high risk of relapse (i.e., both Gleason 8–10 and pT3b/4

but negative

margins [R0]), the majority of experts (72%) opted

for monitoring and early salvage radiotherapy with or without androgen

deprivation therapy in cases of rising PSA. In a similar scenario but with R1,

53% of the participants opted for adjuvant radiotherapy with or without androgen

deprivation therapy as soon as the patient has regained continence after

surgery. Generally, in cases of monitoring, restaging should be performed with

PSMA PET/CT early, i.e., before PSA rises >0.5ng/ml. For patients treated

with radiotherapy after surgery (adjuvant/additive or salvage), 47% of experts

advocated the use of androgen deprivation therapy for 6 months, 33% for 12–24 months

and 20% not at all.

This result reflects a pragmatic interpretation of somewhat conflicting results

from the RADICALS-HD trial, which found that, in men receiving postoperative

radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy, 24 months of androgen deprivation

therapy improved metastasis-free survival (MFS) compared to 6 months of

androgen deprivation therapy, while 6 months of androgen deprivation therapy did

not improve MFS compared to no androgen deprivation therapy [7]. Treatment recommendations

should therefore

be individualized based on patient-specific risk factors. The results of the

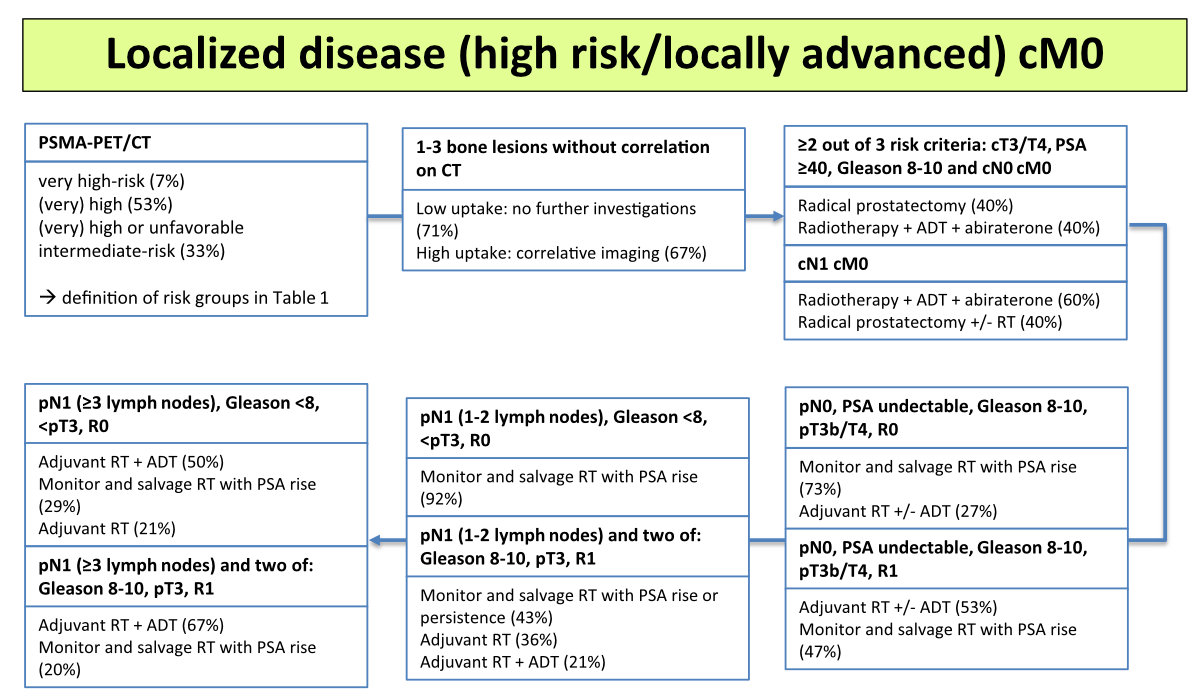

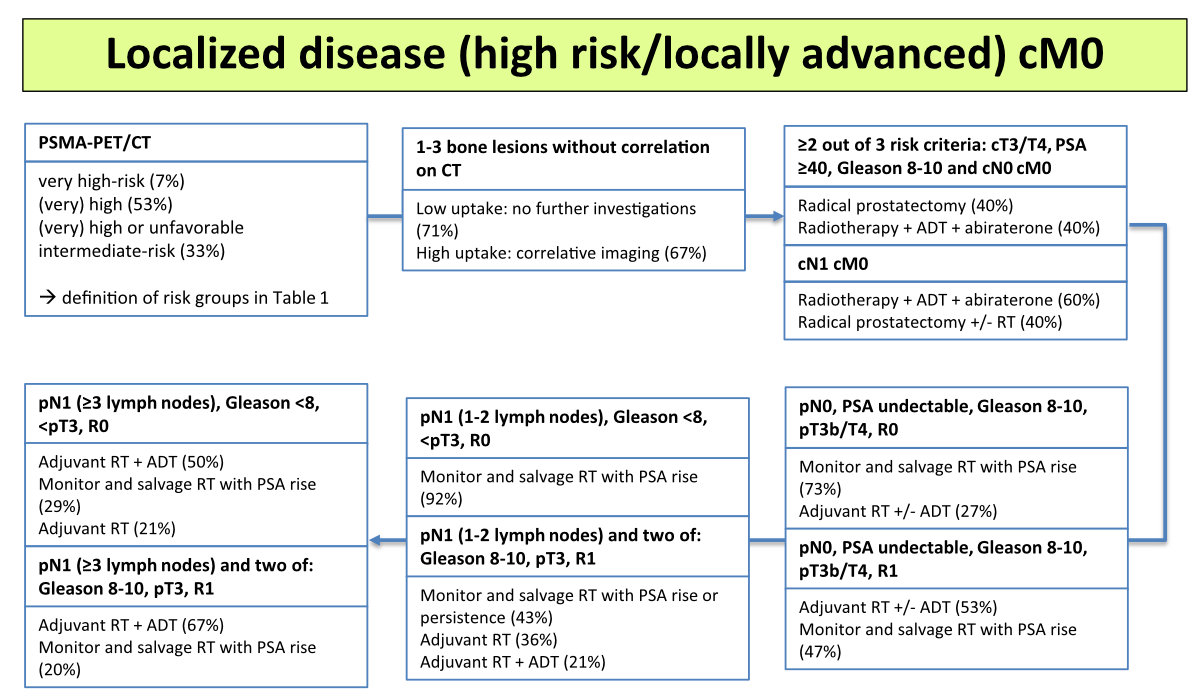

clinically most relevant votes are summarized in figure 3.

Figure 3Staging and treatment of (very) high-risk localized and locally advanced

disease (no distant metastasis), with percentages indicating the voting

results. ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; cM0, no distant metastases;

cN0, no locoregional lymph node metastases; CT, computed tomography; PSA,

prostate-specific antigen; PET, positron emission tomography; PSMA, prostate-specific

membrane antigen; RT,

radiotherapy. Please refer to https://www.swissmedicinfo.ch for approved indications.

Treatment of metastatic

hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC)

Around 5–10% of men with prostate cancer are

found to have metastatic disease at first presentation, i.e., have synchronous

or de novo metastatic (M1) disease [8].

This initial presentation with M1 disease contrasts with metastatic disease recurring

after prior local therapy of the prostate, i.e., metachronous metastatic

disease. The latter presents a more favourable prognosis than synchronous

metastatic disease [9]. Furthermore, the extent

of metastatic disease, namely the presence of visceral disease (e.g.,

metastases in the liver), and the number and localization of bone metastases

are prognostic factors [10]. As a result,

in 2015 high volume disease was defined as the presence of visceral

metastatic disease and/or the presence of at least four bone metastases, of

which at least one was not in the spine or pelvis (with low volume

disease representing all situations in which this high volume definition is not

met) [10]. However, it should be noted

that volume definitions are based on conventional imaging and may be adjusted

in the future with the use of novel imaging (such as PSMA-PET or whole-body

MRI). Median overall survival in cases of synchronous high volume mHSPC is

around 3 years, while median overall survival in cases of metachronous low

volume disease is around 8 years [9, 11].

In recent years, early treatment intensification, with the addition of any of

the novel androgen receptor pathway inhibitors (ARPI: abiraterone, apalutamide

or enzalutamide) or of docetaxel to androgen deprivation therapy, has become the

standard of care for most men with mHSPC, depending on the timing of diagnosis

and extent of disease [12]. In 2022, two

randomized phase 3 studies investigated a triple combination of androgen

deprivation therapy, docetaxel and an ARPI (abiraterone in the PEACE-1 study [13]

and darolutamide in the ARASENS study [14]). Most men in these studies had de novo

mHSPC (all in PEACE-1 and 86% in ARASENS). The addition of either abiraterone or

darolutamide to androgen deprivation therapy and docetaxel was associated with

longer survival; in the PEACE-1 study this result was restricted to men with

high volume disease, for whom median overall survival was prolonged by approximately

1.6 years [13]. A post hoc

analysis of the ARASENS study also demonstrated an increased benefit for high volume

patients [15]. The panel voted on the

question of treatment recommendations for men with synchronous high volume

mHSPC: 60% were in favour of a triplet therapy, and 33% recommended doublet

therapy (i.e., androgen deprivation therapy plus docetaxel or ARPI). In cases

of synchronous low volume disease, there was consensus (80%) for the use

of androgen deprivation therapy plus ARPI (while 20% of experts recommended androgen

deprivation therapy plus docetaxel or ARPI). For men with metachronous high

volume mHSPC, 47% of experts recommended triplet therapy, 27% androgen

deprivation therapy plus ARPI and 27% androgen deprivation therapy plus

docetaxel or ARPI. For men with metachronous low volume mHSPC, experts

reached consensus (93%) for the use of androgen deprivation therapy plus ARPI.

In the latter situation, 50% were in favour of treatment until progression (as

in the pivotal studies), whereas 29% opted for holding both androgen

deprivation therapy and ARPI in the case of a favourable response (i.e., PSA

<0.2 ng/ml) after 2 years with rechallenge upon progression (21% recommended

discontinuing the ARPI only with rechallenge at progression). In the case of

triplet therapy, 40% and 20% of experts were in favour of using darolutamide and

abiraterone, respectively, while the remaining 40% had no preference.

Low volume

mHSPC (defined as up to four bone metastases) has been shown to be predictive of

benefits from local radiotherapy of the prostate, with an 8% gain in absolute overall

survival after 3 years [16]. However,

none of the participants in this trial had received an ARPI, so it remains

uncertain whether a combination of both modalities is needed. Of all Swiss panellists,

47% recommended radiation therapy of the primary tumour in addition to ARPI for

the majority of patients, while 47% recommended this approach only in select

patients (e.g., younger patients), and 7% did not recommend radiation of the

prostate in addition to ARPI.

Metastasis-directed

therapy (MDT)

A majority of

experts (73%) agreed that treatment recommendations for MDT should not be based

on conventional imaging (i.e., CT plus a bone scan) only. In cases of

synchronous low volume mHSPC with one to three bone lesions on PSMA PET/CT, 57%

of panellists favoured systemic therapy plus local treatment of the primary tumour

plus MDT, while 36% voted for systemic therapy plus local treatment of the

primary tumour only. In a similar scenario with metachronous disease, 53% of

experts recommended systemic therapy plus MDT, while 27% favoured MDT without

systemic treatment, and 20% favoured systemic treatment alone. Clear consensus

(93%) was reached regarding the type of MDT, namely radiotherapy. For men with

synchronous low volume mHSPC and one to three PSMA PET/CT–positive retroperitoneal

lymph nodes,

there was no preference (47% of the votes each) for systemic therapy plus local

treatment of the primary tumour or systemic therapy plus local treatment of the

primary tumour plus MDT. The

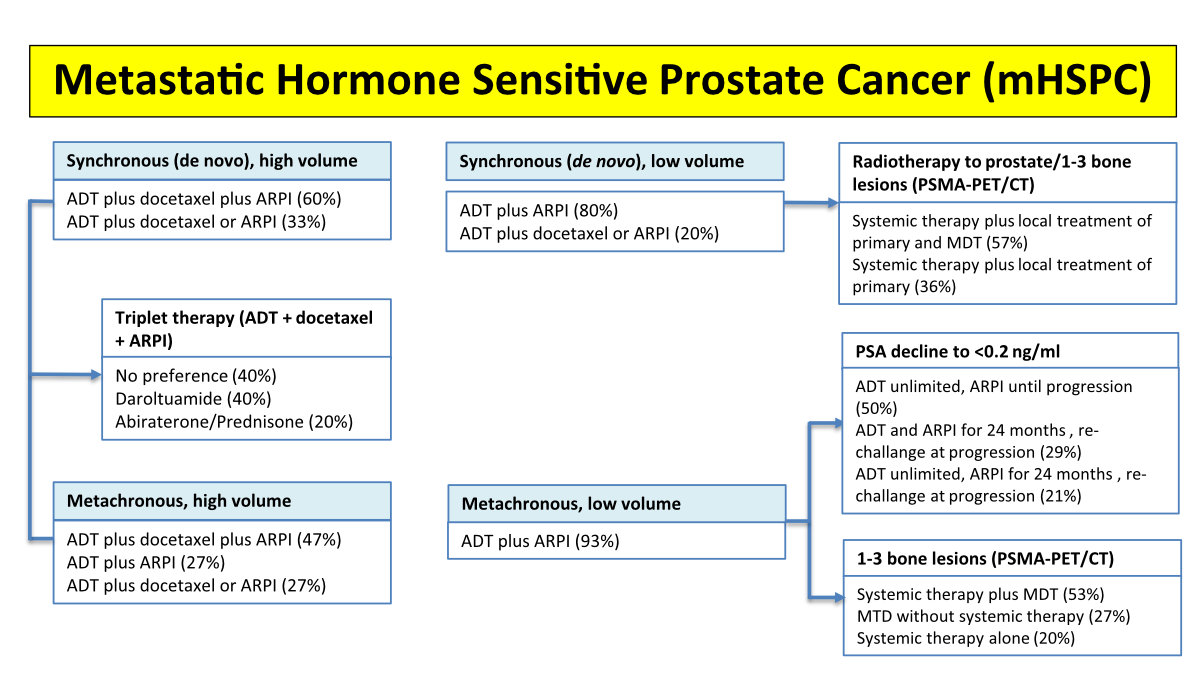

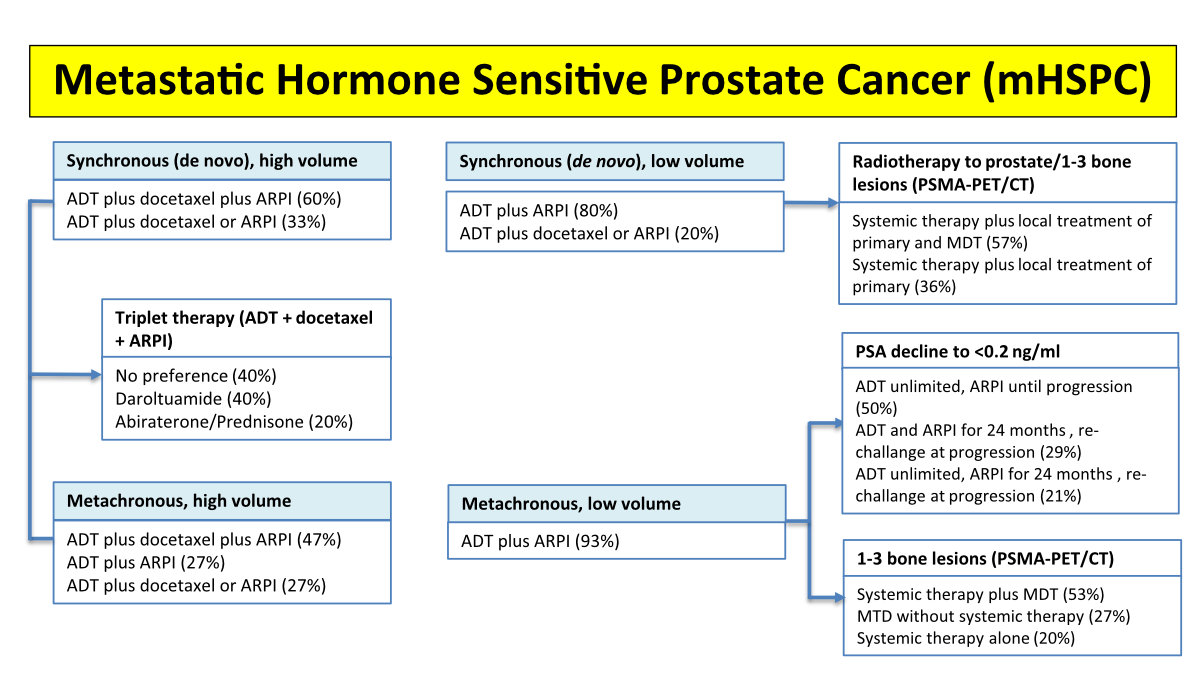

results of relevant votes are summarized in figure 4. Importantly, the evidence

for the effectiveness of MDT in these patients is currently based on small

phase 2 trials and is not supported by large trials showing improvement of

relevant oncological outcomes.

Figure 4Treatment of metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC), with

percentages indicating the voting results. High volume: visceral

disease and/or at least 4 bone metastasis of which at least one outside the

pelvis and vertebral column. Low volume: high volume criteria not met. ADT,

androgendeprivation therapy; ARPI, androgen receptor pathway inhibitor (abiraterone,

enzalutamide, apalutamide, darolutamide); CT, computed tomography; MTD,

metastasis directed therapy; PET, positron emission tomography; PSA,

prostate-specific antigen; PSMA, prostate-specific membrane antigen; RT,

radiotherapy. Please refer to https://www.swissmedicinfo.ch for approved indications.

Additional investigations

and follow-up in mHSPC patients

There was

consensus (87%) that molecular tests (i.e., next-generation sequencing) would

not influence the decision of the first-line treatment for mHSPC, even if

available without restrictions. Given the lack of high-quality data on

follow-up modalities and intervals during the treatment of mHSPC, the following

questions were discussed. In the absence of symptoms, 47% of experts recommended

regular imaging, e.g., every 6–12 months, regardless of PSA, while 33% recommended

imaging after about

6–12 months and

then no more imaging until confirmed PSA progression, and 20% recommended imaging

prompted only by rising PSA. As for imaging modality, 53% of panellists opted

for conventional imaging (CT with or without a bone scan), whereas 27% and 13% favoured

PET/CT and whole-body MRI, respectively. Again, there is very limited evidence for

how to interpret, e.g., PSMA PET/CT in patients responding to systemic therapy,

and, in fact, in Switzerland PSMA PET/CT is not approved or reimbursed in this situation.

Metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC)

Selection of first-line

therapy and treatment sequence

In the

absence of alterations of DNA damage response and repair (DDR) genes, all

experts (100%) recommended an ARPI as a first-line therapy for mCRPC in men who

received androgen deprivation therapy as monotherapy for mHSPC. In cases of

time to castration resistance of less than 6 months (i.e., progression within 6

months of the start of androgen deprivation therapy), the use of ARPI or

chemotherapy was considered adequate (both options were recommended by 47% of

experts). For men treated with an ARPI in the case of mHSPC, all panellists

(100%) recommend a switch to chemotherapy, irrespective of time to castration resistance.

Most

experts (64%) did not recommend a switch to another ARPI therapy in the

majority of patients who have received one line of ARPI and then have progressed.

By contrast, 29% deemed a switch appropriate in select patients who had a prior

response to abiraterone and subsequently progressed. The basis for the latter

recommendation is a study showing a PSA response rate of 19% in this situation [17],

while, e.g., abiraterone after

enzalutamide was associated with a very low PSA response rate of around 1% [18].

PARP inhibition

In around 10%

of mCRPC cases, tumours harbour a pathogenic BRCA1/2 alteration (around

half of which is germ line) [19, 20] that

is predictive of benefits from PARP inhibition. Recently, studies combining new

endocrine therapies (e.g., abiraterone or enzalutamide) with PARP inhibitors (e.g.,

olaparib, niraparib or talazoparib) have reported longer radiographic

progression-free survival with the combination, irrespective of DDR status, at

the cost of increased toxicity and no improvement in overall survival for

unselected populations [21–23]. In

all these studies, in most cases castration resistance had occurred in patients

receiving androgen deprivation therapy as monotherapy. There was consensus

(93%) not to combine ARPI with a PARP inhibitor as first-line therapy for mCRPC,

irrespective of DDR status. However, for men with mCRPC with a pathogenic BRCA1/2

alteration who developed castration resistance during androgen deprivation

therapy and an ARPI (with or without docetaxel), 38% of experts recommended a switch

to PARP inhibitor monotherapy, whereas others favoured a switch to chemotherapy

(31%) or the addition of a PARP inhibitor to continued ARPI (31%). In cases of

other (i.e., not BRCA1/2) pathogenic DNA repair gene alterations, there

was consensus (86%) to switch to chemotherapy.

Radionuclide

therapy

The use of 177Lu-PSMA

has led to an overall survival benefit in patients with mCRPC and pretreatment

with ARPI and docetaxel if PSMA avidity has been demonstrated on a staging PSMA

PET/CT [24]. In men with symptomatic

mCRPC who met criteria for treatment with both 223Ra and 177Lu-PSMA,

there was consensus (80%) in favour of using 177Lu-PSMA, while 13%

of experts had no preference. Furthermore, there was consensus (93%) to

recommend 177Lu-PSMA after prior treatment with docetaxel and an ARPI.

Imaging and

follow-up for mCRPC patients

The majority

of the panel (73%) recommended imaging every 3–6 months for men being treated for

mCRPC, regardless of PSA and in the absence of new symptoms. In terms of

imaging modality, 47% of panellists favoured CT scans (with or without a bone

scan), while 29%, 14% and 7% opted for a CT scan plus a bone scan, whole-body

MRI and PET/CT, respectively.

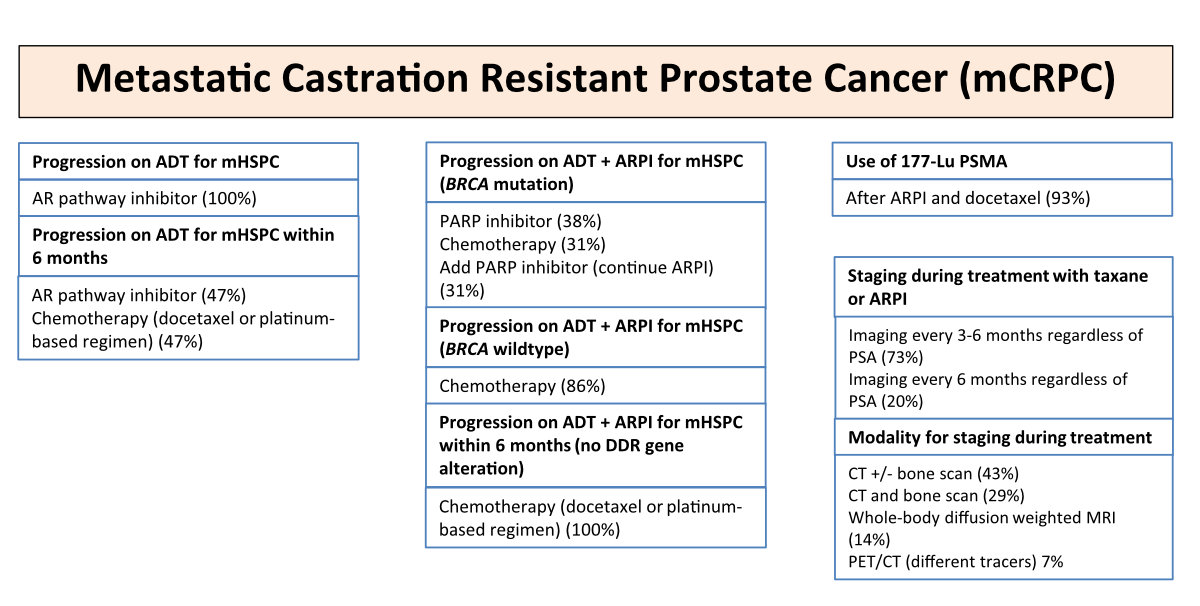

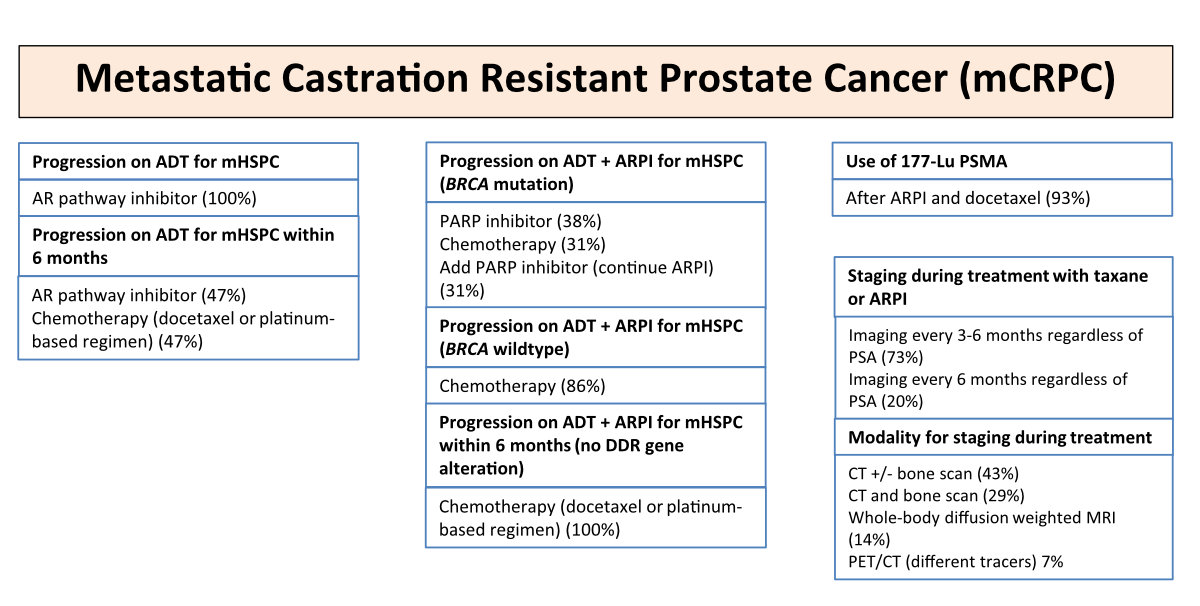

The results

of relevant votes are summarized in figure 5.

Figure 5Treatment and staging of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer

(mCRPC), with percentages indicating the voting results. ADT,

androgendeprivation therapy; AR, androgen receptor; ARPI, androgen receptor

pathway inhibitor; BRCA, breast cancer gene; DDR, DNA Damage Response and Repair;

Lu, Lutetium; mHSPC,

metastatic hormone sensitive prostate cancer; CT, computed tomography; MRI,

magnet resonance imaging; PARP, Poly ADP-Ribose Polymerase; PET, positron

emission tomography; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; PSMA,

prostate-specific membrane antigen. Please refer to https://www.swissmedicinfo.ch for approved indications.

Health-economic

aspects

Concerns

about the availability and costs of modern therapies were prevalent among the

participants in the consensus meeting. When asked whether financial cost to the

health care system should be considered when making treatment decisions or recommendations,

89% of experts responded “yes, absolutely” and 11% “no, not at all”. It remains

to be determined how this can be achieved in daily practice while ensuring

optimal treatment for all our patients. First steps might be using generic

drugs, if available; de-escalation strategies; and strict adherence to the

principle that diagnostic procedures must have a therapeutic consequence.

Acknowledgements

The authors

would like to thank Fabienne Trattner from Medtoday Switzerland and Nadja Burri

from the Swiss Group of Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) in Bern for their great

administrative support in organizing the meeting.

PD Dr. Arnoud Templeton

Medical Oncology

Claraspital Basel

CH-4058 Basel

arnoud.templeton[at]claraspital.ch

PD Dr. Richard Cathomas

Division of Oncology/Hematology

Kantonsspital

Graubünden

CH-7000

Chur

richard.cathomas[at]ksgr.ch

References

1. Gillessen S, Bossi A, Davis ID, de Bono J, Fizazi K, James ND, et al. Management of

Patients with Advanced Prostate Cancer. Part I: Intermediate-/High-risk and Locally

Advanced Disease, Biochemical Relapse, and Side Effects of Hormonal Treatment: Report

of the Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference 2022. Eur Urol. 2022.

2. Ingvar J, Hvittfeldt E, Trägårdh E, Simoulis A, Bjartell A. Assessing the accuracy

of [18F]PSMA-1007 PET/CT for primary staging of lymph node metastases in intermediate- and

high-risk prostate cancer patients. EJNMMI Res. 2022 Aug;12(1):48. 10.1186/s13550-022-00918-7

3. Anttinen M, Ettala O, Malaspina S, Jambor I, Sandell M, Kajander S, et al. A Prospective

Comparison of 18F-prostate-specific Membrane Antigen-1007 Positron Emission Tomography Computed Tomography,

Whole-body 1.5 T Magnetic Resonance Imaging with Diffusion-weighted Imaging, and Single-photon

Emission Computed Tomography/Computed Tomography with Traditional Imaging in Primary

Distant Metastasis Staging of Prostate Cancer (PROSTAGE). Eur Urol Oncol. 2021 Aug;4(4):635–44.

10.1016/j.euo.2020.06.012

4. Grünig H, Maurer A, Thali Y, Kovacs Z, Strobel K, Burger IA, et al. Focal unspecific

bone uptake on [18F]-PSMA-1007 PET: a multicenter retrospective evaluation of the distribution, frequency,

and quantitative parameters of a potential pitfall in prostate cancer imaging. Eur

J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021 Dec;48(13):4483–94. 10.1007/s00259-021-05424-x

5. Vollnberg B, Alberts I, Genitsch V, Rominger A, Afshar-Oromieh A. Assessment of malignancy

and PSMA expression of uncertain bone foci in [18F]PSMA-1007 PET/CT for prostate cancer-a single-centre experience of PET-guided biopsies.

Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022 Sep;49(11):3910–6. 10.1007/s00259-022-05745-5

6. Attard G, Murphy L, Clarke NW, Cross W, Jones RJ, Parker CC, et al.; Systemic Therapy

in Advancing or Metastatic Prostate cancer: Evaluation of Drug Efficacy (STAMPEDE)

investigators. Abiraterone acetate and prednisolone with or without enzalutamide for

high-risk non-metastatic prostate cancer: a meta-analysis of primary results from

two randomised controlled phase 3 trials of the STAMPEDE platform protocol. Lancet.

2022 Jan;399(10323):447–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02437-5

7. Parker CC, Clarke N, Cook A, Catton C, Cross WR, Kynaston H, et al. Duration of androgen

deprivation therapy (ADT) with post-operative radiotherapy (RT) for prostate cancer:

First results of the RADICALS-HD trial (ISRCTN40814031). Annals of Oncology 2022;33

(suppl_7):S808-S69. 10.1016/annonc/annonc89 (LBA 9).

8. Rebello RJ, Oing C, Knudsen KE, Loeb S, Johnson DC, Reiter RE, et al. Prostate cancer.

Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021 Feb;7(1):9. 10.1038/s41572-020-00243-0

9. Francini E, Gray KP, Xie W, Shaw GK, Valença L, Bernard B, et al. Time of metastatic

disease presentation and volume of disease are prognostic for metastatic hormone sensitive

prostate cancer (mHSPC). Prostate. 2018 Sep;78(12):889–95. 10.1002/pros.23645

10. Sweeney CJ, Chen YH, Carducci M, Liu G, Jarrard DF, Eisenberger M, et al. Chemohormonal

Therapy in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug;373(8):737–46.

10.1056/NEJMoa1503747

11. Gravis G, Boher JM, Chen YH, Liu G, Fizazi K, Carducci MA, et al. Burden of Metastatic

Castrate Naive Prostate Cancer Patients, to Identify Men More Likely to Benefit from

Early Docetaxel: Further Analyses of CHAARTED and GETUG-AFU15 Studies. Eur Urol. 2018 Jun;73(6):847–55.

10.1016/j.eururo.2018.02.001

12. Cornford P, van den Bergh RC, Briers E, Van den Broeck T, Cumberbatch MG, De Santis M,

et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Part II-2020 Update:

Treatment of Relapsing and Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol. 2021 Feb;79(2):263–82.

10.1016/j.eururo.2020.09.046

13. Fizazi K, Foulon S, Carles J, Roubaud G, McDermott R, Fléchon A, et al.; PEACE-1 investigators.

Abiraterone plus prednisone added to androgen deprivation therapy and docetaxel in

de novo metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (PEACE-1): a multicentre,

open-label, randomised, phase 3 study with a 2×2 factorial design. Lancet. 2022 Apr;399(10336):1695–707.

10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00367-1

14. Smith MR, Hussain M, Saad F, Fizazi K, Sternberg CN, Crawford ED, et al.; ARASENS

Trial Investigators. Darolutamide and Survival in Metastatic, Hormone-Sensitive Prostate

Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022 Mar;386(12):1132–42. 10.1056/NEJMoa2119115

15. Hussain M, Tombal B, Saad F, Fizazi K, Sternberg CN, Crawford ED, et al. Darolutamide

Plus Androgen-Deprivation Therapy and Docetaxel in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate

Cancer by Disease Volume and Risk Subgroups in the Phase III ARASENS Trial. J Clin

Oncol. 2023 Jul;41(20):3595–607. 10.1200/JCO.23.00041

16. Parker CC, James ND, Brawley CD, Clarke NW, Hoyle AP, Ali A, et al.; Systemic Therapy

for Advanced or Metastatic Prostate cancer: Evaluation of Drug Efficacy (STAMPEDE)

investigators. Radiotherapy to the primary tumour for newly diagnosed, metastatic

prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018 Dec;392(10162):2353–66.

10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32486-3

17. de Bono JS, Chowdhury S, Feyerabend S, Elliott T, Grande E, Melhem-Bertrandt A, et

al. Antitumour Activity and Safety of Enzalutamide in Patients with Metastatic Castration-resistant

Prostate Cancer Previously Treated with Abiraterone Acetate Plus Prednisone for ≥24

weeks in Europe. Eur Urol. 2018 Jul;74(1):37–45. 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.07.035

18. Attard G, Borre M, Gurney H, Loriot Y, Andresen-Daniil C, Kalleda R, et al.; PLATO

collaborators. Abiraterone Alone or in Combination With Enzalutamide in Metastatic

Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer With Rising Prostate-Specific Antigen During

Enzalutamide Treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Sep;36(25):2639–46. 10.1200/JCO.2018.77.9827

19. Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu YM, Schultz N, Lonigro RJ, Mosquera JM, et al. Integrative

clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015 May;161(5):1215–28. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.001

20. de Bono J, Mateo J, Fizazi K, Saad F, Shore N, Sandhu S, et al. Olaparib for Metastatic

Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020 May;382(22):2091–102. 10.1056/NEJMoa1911440

21. Clarke NW, Armstrong AJ, Thiery-Vuillemin A, Oya M, Shore N, Loredo E, et al. Abiraterone

and Olaparib for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. NEJM Evid. 2022;2022(9):1.

10.1056/EVIDoa2200043

22. Chi KN, Rathkopf DE, Smith MR, Efstathiou E, Attard G, Olmos D, et al. Phase 3 MAGNITUDE

study: First results of niraparib (NIRA) with abiraterone acetate and prednisone (AAP)

as first-line therapy in patients (pts) with metastatic castration-resistant prostate

cancer (mCRPC) with and without homologous recombination repair (HRR) gene alterations.

Journal/ASCO GU abstract #12 2022;

23. Pfizer. Pfizer Announces Positive Topline Results from Phase 3 TALAPRO-2 Trial 2022

(Press release on Oct 4);

24. Sartor O, de Bono J, Chi KN, Fizazi K, Herrmann K, Rahbar K, et al.; VISION Investigators.

Lutetium-177-PSMA-617 for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N Engl

J Med. 2021 Sep;385(12):1091–103. 10.1056/NEJMoa2107322