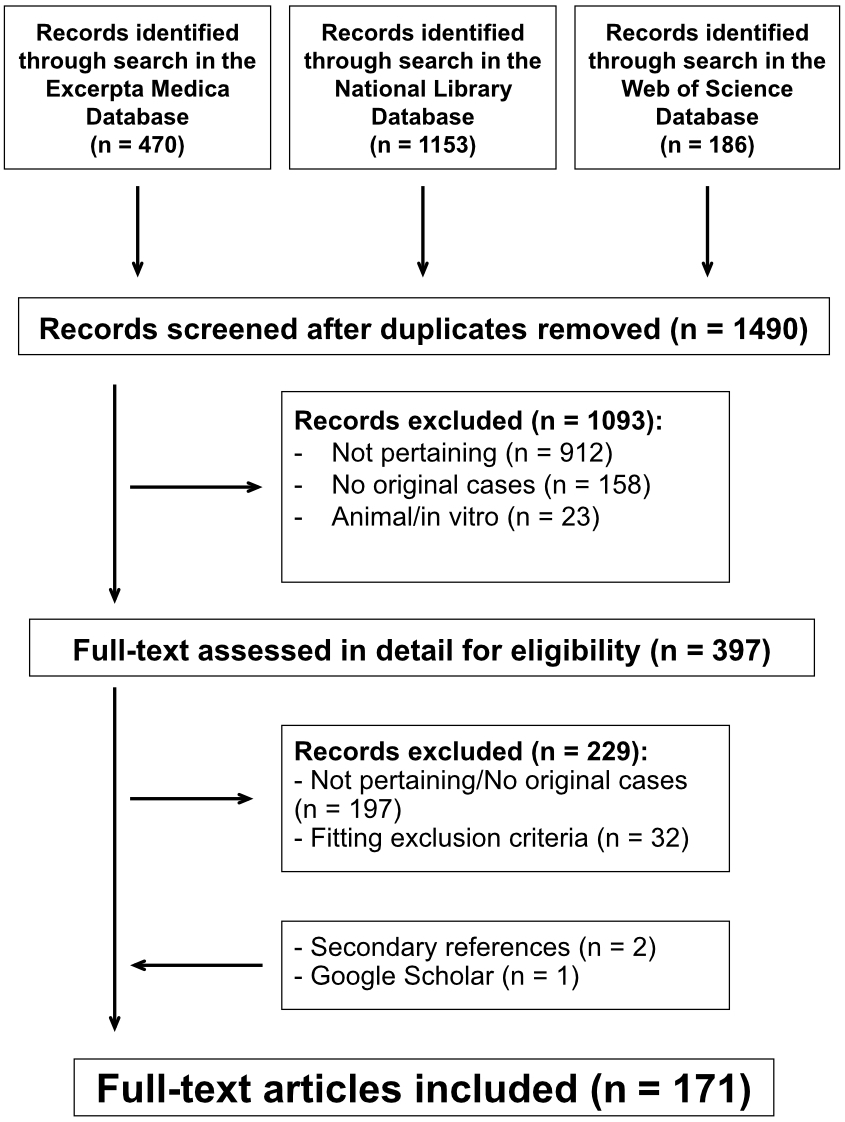

Figure 1Splenic rupture or infarction associated with Epstein-Barr virus infectious mononucleosis. PRISMA flow chart of the literature search.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/smw.2023.40081

Epstein-Barr virus, also known as herpesvirus 4, is one of the most common human viruses [1, 2]. Primary infectious mononucleosis, the best-known presentation of this virus, typically affects adolescents and young adults; presents with fatigue, malaise, sore throat and enlarged cervical lymph nodes, liver or spleen; and generally spontaneously resolves over a few weeks [1, 2].

The spleen is always involved in mononucleosis. Although not always palpable, splenomegaly is detected by ultrasound in all affected individuals [1–3]. The splenic architecture is distorted because the parenchyma is infiltrated by atypical lymphocytes that compromise the fibrous support system and thin the capsule. Splenomegaly and the distorted architecture predispose to rupture, which is often not associated with a notable trauma but perhaps exclusively heralded by triggers such as coughing, sneezing, straining during defecation or muscular exertion [1, 2, 4]. It is also traditionally assumed that rupture may result from vigorous palpation [4]. There might be an increased tendency to splenic infarction as well [5].

Surgical spleen removal has been the traditional management of both traumatic and atraumatic splenic injury [6–8]. However, since spleen removal may result in immune deficiency and invasive infections due to encapsulated bacteria, which occur especially in children and teenagers [6–9], strategies to conserve splenic function by avoiding total splenectomy have been increasingly proposed [6–9].

The features of mononucleosis-associated splenic rupture and infarction have not been comprehensively investigated in the recent past. Furthermore, it is currently unclear whether spleen-preserving management is considered a viable alternative to splenectomy.

Since mononucleosis-associated splenic rupture and infarction are rare, available knowledge on these complications is mainly based on case reports. To address these issues, we carried out a systematic review of the literature.

This review was pre-registered in the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42022370268) and carried out in agreement with the second edition of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations [10]. Data sources included Excerpta Medica, the United States National Library of Medicine, and Web of Science from 1 January 1970, without any further limitation. The search strategy incorporated the following terms entered in separate pairs: (Epstein-Barr virus OR glandular fever OR infectious mononucleosis OR herpesvirus 4) AND (hematoperitoneum OR splenic hematoma OR splenic infarction OR splenic rupture). Articles listed within reference lists of the retrieved records, reports published in Google Scholar and articles already known to the authors were also considered. Searches were conducted in April 2022 and repeated before article submission.

Patients had to meet three criteria to be included: (i) an individually documented case who presented with a positive Paul-Bunnell-Davidsohn test, a specific acute Epstein-Barr virus serology response or both [1, 2]; (ii) having clinical features of primary mononucleosis; and (iii) either a splenic rupture or a splenic infarction. Cases with splenic rupture or infarction not supported by serological evidence of an existing Epstein-Barr virus infection were excluded.

For each case, the following information was extracted in a pilot-tested spreadsheet: (a) relevant past and recent medical history with emphasis on any pre-existing haematological diseases, recent abdominal trauma or vigorous abdominal palpation; (b) the clinical features of mononucleosis [1, 2], i.e. fever (38.0 °C or more), fatigue, malaise, sore throat, yellowish scleral discolouration (referred to as “jaundice” in the remainder of this article), cervical adenopathy (lymph nodes felt to be 1 cm or larger in diameter), hepatomegaly or splenomegaly (a palpable liver edge or spleen); and (c) clinical and laboratory features of splenic rupture or infarction at presentation, including blood pressure, heart rate and signs of haemodynamic instability (shortness of breath, prolonged capillary refill time, mottling of cool and moist extremities, peripheral cyanosis, altered mentation), pain (classified as diffuse abdominal pain, left upper abdominal pain or left shoulder pain), a full blood count (with leucocyte differential) [11], enzyme values (aminotransferases and lactate dehydrogenase) and imaging studies.

The diagnosis of splenic rupture or splenic infarction was suspected clinically and always confirmed by means of appropriate imaging studies or, in haemodynamically unstable cases, a diagnostic laparotomy. The time elapsed from onset of symptoms of mononucleosis to the diagnosis of splenic rupture or infarction was recorded. The diagnosis of mild mononucleosis was made in cases with two or fewer of the following five typical features: cervical adenopathy, fever, malaise, sore throat, splenomegaly. The diagnosis of mononucleosis-associated transaminitis was made in cases with a more than 2-fold elevation in aminotransferase ratio compared to the laboratory’s reference value. It has been speculated that in mononucleosis a more than 2-fold elevation in lactate dehydrogenase ratio indicates splenic infarction [5]. Consequently, the value of the latter test was verified. Cases with a platelet count of 20–70 × 109/l or <20 × 109/l were recorded.

The clinical and imaging data of each case of mononucleosis-associated splenic rupture was used to score the rupture as minor, moderate or severe according to the spleen trauma classification recommended in 2017 by the World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) [12]. This classification takes into account both the anatomy of splenic lesions and the patient’s haemodynamic condition and has proved to be a reliable tool in the decision-making process in splenic trauma treatment [12]. The management was stratified using the following well-established terminology [6–8]: “operative management” was used for cases of splenic rupture who underwent an immediate surgical splenectomy; “failure of non-operative management ” for cases who underwent a surgical splenectomy after an initial unsuccessful conservative approach; “non-operative management” for the remaining patients — this term was used both for cases with conservative care alone and for cases with an adjunctive treatment such as transcatheter arterial embolisation.

The comprehensiveness of included cases was evaluated using the following seven components: 1. Characterisation of the patient; 2. Clinical presentation; 3. Disease duration; 4. Vital parameters; 5. Full blood count; 6. Haemodynamic instability; 7. Management and outcome. Each component was rated as 0, 1 or 2 and the reporting quality was graded according to the sum of each item as satisfactory, good or excellent [13].

Two authors (JMAT/BG) separately and in duplicate performed the literature search, selected studies for inclusion, extracted data and evaluated the comprehensiveness of each case. Any disagreements were discussed, and a senior author (MGB) was consulted to resolve any outstanding issues. One author (JMAT) entered the data into a pre-defined worksheet and another (BG) verified the accuracy of data entry.

Pairwise deletion was used to handle missing data. Categorical variables are presented as proportions and continuous variables as medians with interquartile range. Dichotomous categorical variables were compared using the Fisher exact test; ordered categorical variables using the Kruskal-Wallis test and the post-hoc Tukey correction; and continuous variables using the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Linear regressions with the Spearman non-parametric coefficient of correlation rs were also calculated. A two-sided significance level of 0.05 was used. GraphPad Prism 9.5.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA) was used for statistics.

The study was a systematic review and as such did not require specific ethics approval at our institutions.

The analysis included 171 articles published between 1970 and 2022 [14–184] (figure 1). The languages of these 171 reports were English (130), Spanish (19), German (12), French (6) and Italian (4). The reports originated from the following continents (countries): 86 from Europe (United Kingdom: 23, Spain: 15, Germany: 13, Italy: 7, Switzerland: 7, France: 6, Belgium: 5, Greece: 3, Ireland: 2, Netherlands: 2, Portugal: 2, Czechia: 1), 62 from the Americas (United States of America: 55, Canada: 3, Chile: 2, Mexico:1, Peru: 1), 17 from Asia (Japan: 5, Israel: 3, South Korea: 3, India: 2, China: 2, Pakistan: 1, Saudi Arabia: 1) and 6 from Oceania (Australia: 5, New Zealand: 1). The 171 reports addressed cases of mononucleosis complicated by splenic rupture (144 reports), cases complicated either by rupture or infarction (1) or cases complicated by infarction (26). The reports documented 215 patients (one patient in 148 reports, two patients in 11 reports, three patients in 7 reports, four patients in 4 reports and eight patients in 1 report): 186 with splenic rupture [14–158] and 29 with infarction [158–184]. Reporting comprehensiveness was satisfactory in 1 case, good in 125 and excellent in 89.

Figure 1Splenic rupture or infarction associated with Epstein-Barr virus infectious mononucleosis. PRISMA flow chart of the literature search.

The characteristics of the 215 patients are presented in table 1. A positive Paul-Bunnell-Davidsohn test (n = 90), a specific acute Epstein-Barr virus serology response (n = 87) or both a Paul-Bunnell-Davidsohn test and a specific Epstein-Barr virus serology response (n = 30) supported the diagnosis of mononucleosis in 207 cases. The diagnosis of mononucleosis was made uniquely on a histological basis (spleen showing largenumbers of atypical lymphocytes) in the remaining 8 cases, who died within hours after admission. A pre-existing haematological disease was significantly more frequent (p = 0.001) in splenic infarction as compared to splenic rupture. The prevalence of recent history of abdominal trauma was not statistically different between rupture and infarction patients. In no cases was rupture or infarction preceded by overeager palpation. As compared to cases affected by splenic infarction, cases with splenic rupture presented less frequently with fever or fatigue (table 1). Furthermore, left shoulder pain and haemodynamic instability were more frequent in the splenic rupture group (p = 0.001). A transaminitis was significantly more common in the splenic infarction group (p = 0.001). The prevalence of cases with lactatedehydrogenase level ≥600 U/l was similar in patients with splenic rupture and in those with splenic infarction. The tendency towards a platelet count 20–70 × 109/l or <20 × 109/l was not statistically different in the two study groups.

Table 1Characteristics of 215 patients (82 females and 133 males) with Epstein-Barr virus mononucleosis complicated by splenic rupture or infarction. Results are presented as frequency (and percentage) or as median (with interquartile range). Significant p values are given in bold.

| Splenic rupture | Splenic infarction | p value | |||

| n | 186 | 29 | |||

| Females:Males, n (%) | 73 (40): 113 (60) | 9 (30): 20 (70) | 0.538 | ||

| Age | Years | 20 [17–25] | 19 [17–22] | 0.136 | |

| <16 years, n (%) | 17 (9.1) | 5 (17) | 0.189 | ||

| Pre-existing haematological disease, n (%) | 1 (0.5) | 6 (21) | 0.001 | ||

| History | Fever, n (%) | 95 (51) | 26 (90) | 0.001 | |

| Malaise, n (%) | 107 (58) | 16 (55) | 0.842 | ||

| Fatigue, n (%) | 40 (22) | 13 (45) | 0.010 | ||

| Sore throat, n (%) | 99 (53) | 21 (72) | 0.070 | ||

| Nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea n (%) | 51 (27) | 11 (38) | 0.273 | ||

| Previous abdominal trauma*, n (%) | 17 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 0.137 | ||

| Vigorous abdominal palpation, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.999 | ||

| Examination | Abdominal pain | No abdominal pain, n (%) | 14 (7.5) | 2 (6.9) | 0.999 |

| Diffuse abdominal pain, n (%) | 172 (93) | 27 (93) | 0.904 | ||

| Left upper quadrant pain, n (%) | 112 (60) | 19 (66) | 0.684 | ||

| Left shoulder pain, n (%) | 68 (37) | 2 (6.9) | 0.001 | ||

| Enlarged cervical lymph nodes, n (%) | 97 (52) | 13 (45) | 0.550 | ||

| Jaundice, n (%) | 8 (4.3) | 8 (28) | 0.001 | ||

| Hepatomegaly, n (%) | 25 (13) | 8 (28) | 0.091 | ||

| Splenomegaly, n (%) | 152 (83) | 25 (86) | 0.794 | ||

| Mild presentation, n (%) | 38 (20) | 1 (3.4) | 0.035 | ||

| Haemodynamic parameters | Heart rate, bpm | 105 [90–122] | 105 [86–115] | 0.887 | |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 102 [90–115] | 126 [115–130] | 0.009 | ||

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 60 [53–70] | 70 [64–81] | 0.034 | ||

| Haemodynamic instability, n (%) | 58 (31) | 0 (0) | 0.001 | ||

| Laboratory findings | Haemoglobin (g/l) | 105 [90–122] | 123 [78–134] | 0.425 | |

| Platelet count | 109/l | 170 [101–230] | 190 [135–309] | 0.290 | |

| <20 × 109/l, n (%) | 3 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 0.999 | ||

| 20–70 × 109/l, n (%) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (6.9) | 0.088 | ||

| Leucocyte count (109/l) | 13.1 [9.9–17.2] | 11.0 [6.4–14.0] | 0.011 | ||

| % lymphocytes | 50 [37–69] | 59 [51–70] | 0.238 | ||

| % atypical lymphocytes | 25 [10–47] | 18 [5–93] | 0.678 | ||

| C-reactive protein (mg/l) | 49 [42–67] | 18 [5–93] | 0.254 | ||

| Transaminitis, n (%) | 38 (20) | 17 (59) | 0.001 | ||

| Lactate dehydrogenase ≥2 upper limit of normal, n (%) | 7** (41) | 12*** (67) | 0.181 | ||

* injury while playing contact sports (n = 9), minor fall on the left side (n = 4), major fall (n = 3), heavy lifting (n = 1)

** assessed in 17 cases

*** assessed in 18 cases

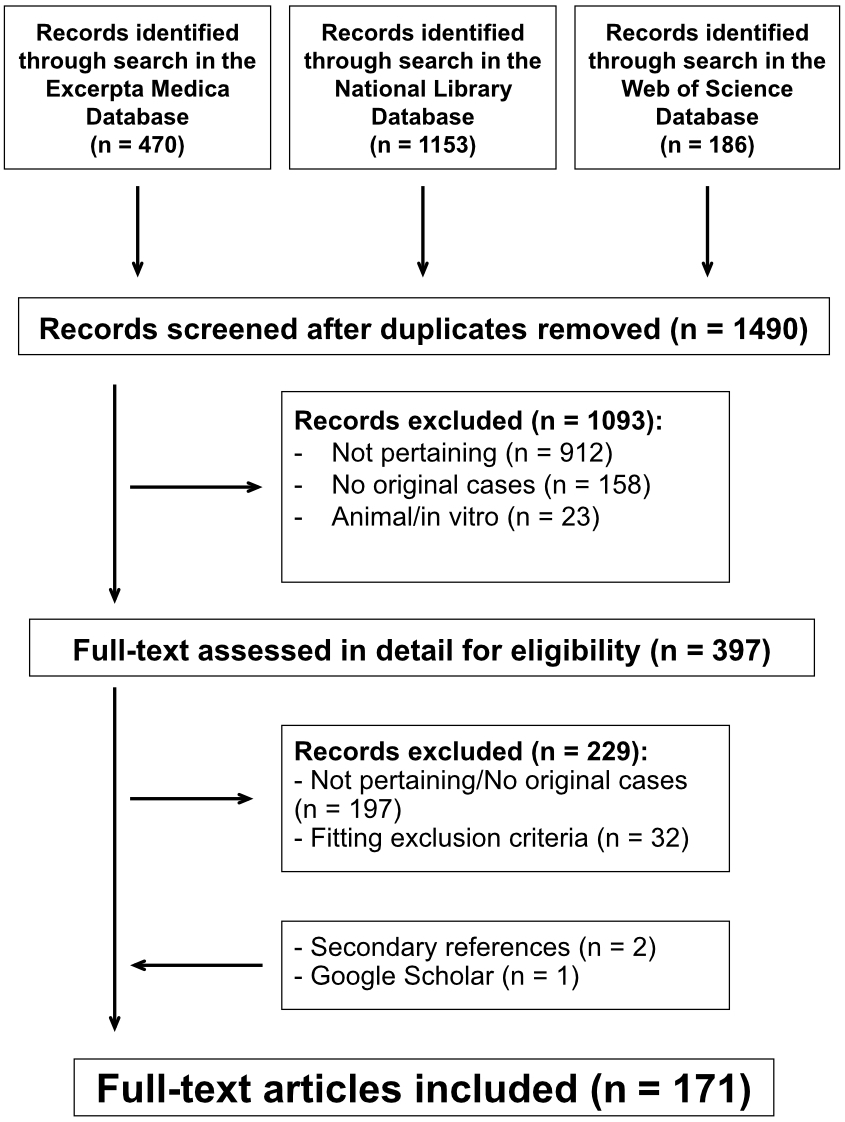

Information on the elapsed time between onset of mononucleosis symptoms and signs of splenic disease was available for 145 cases with rupture (54 females and 91 males; 20 [17–25] years) and 26 cases with infarction (8 females and 18 males; 19 [17–20] years) (figure 2). At least 80% of all cases occurred within three weeks after the onset of mononucleosis symptoms. The mentioned time interval was on average slightly but significantly longer for rupture than for infarction (8 [6–14] vs 7 [4–10] days; p = 0.034). In approximately 10% of cases, the splenic disease occurred four weeks or more after the clinical presentation of mononucleosis.

Figure 2Time from onset of symptoms of Epstein-Barr virus infectious mononucleosis and onset of symptoms of splenic rupture or infarction.

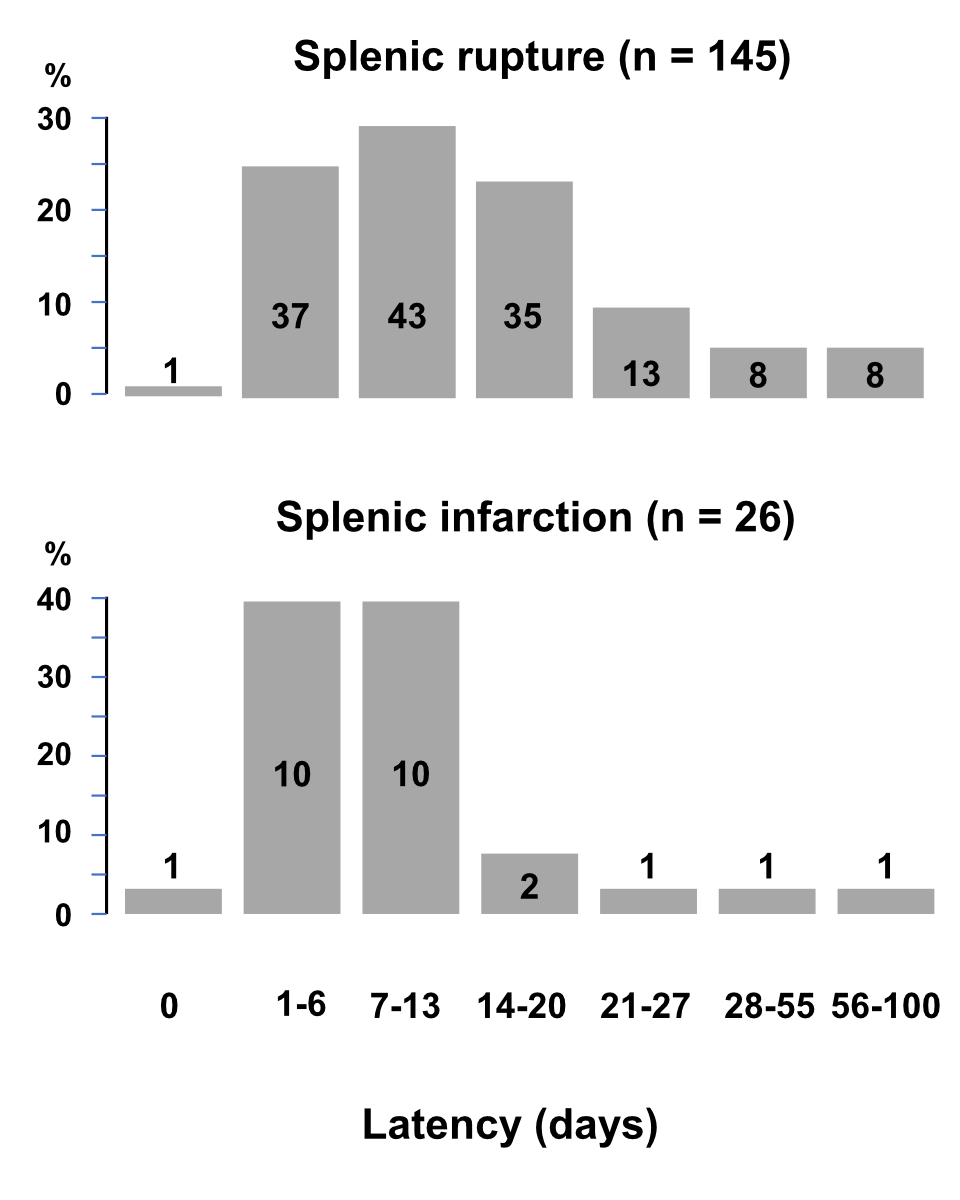

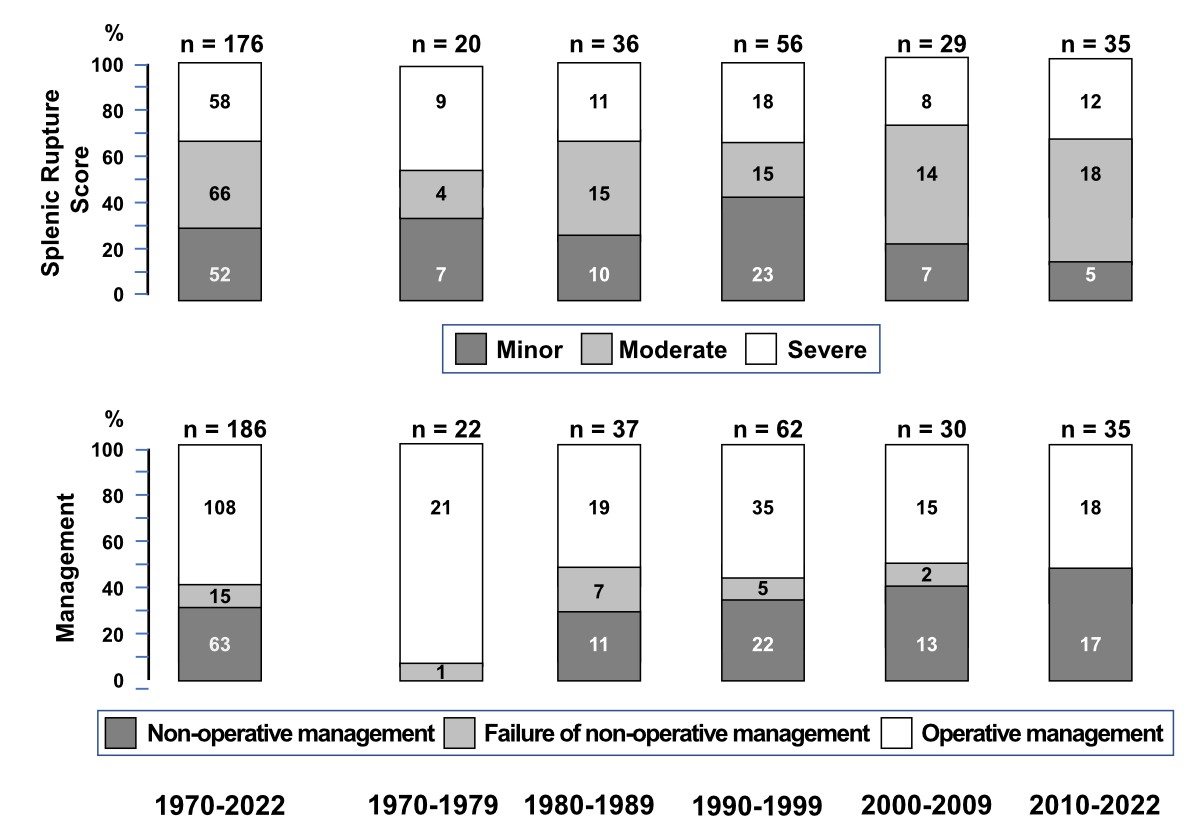

The relationship between the World Society of Emergency Surgery splenic rupture score and management in patients with splenic rupture is shown in table 2. While almost 85% of cases with a severe rupture score were splenectomised, this figure was about 50% for cases with a minor or moderate rupture score (p = 0.001).

Table 2Relationship between World Society of Emergency Surgery splenic rupture score and management in patients with mononucleosis-associated splenic rupture.

| World Society of Emergency Surgery splenic rupture score | |||||

| All | Minor | Moderate | Severe | Unknown | |

| n | 186 | 53 | 68 | 55 | 10 |

| Operative, n (%)* | 108 (58) | 26 (49) | 35 (51) | 41 (75) | 6 (60) |

| Failure of non-operative management, n (%)* | 14 (7.5) | 1 (1.8) | 8 (12) | 5 (9.0) | 0 (0) |

| Non-operative, n (%) | 64 (34) | 26 (49) | 25 (37) | 9 (16) | 4 (40) |

* While 46 out of 55 cases with a severe rupture score were splenectomised, this figure (70 out of 121 cases) was lower (p = 0.001) for cases with a minor or moderate rupture score.

The severity of splenic rupture and its management were analysed over five periods: 1970–1979, 1980–1989, 1990–1999, 2000–2009 and 2010–2022 (figure 3). The splenic rupture was classified as minor in 52 (30%), moderate in 66 (38%) and severe in 58 (33%) of the 176 cases with this information. The splenic rupture classification score was not statistically different in the five periods (p = 0.415).

Figure 3World Society of Emergency Surgery splenic rupture score in patients with splenic rupture associated with Epstein-Barr virus infectious mononucleosis.

Splenectomy, either immediate (operative management; n = 108) or after failure of non-operative (failure of operative management; n = 15) management was the most common treatment strategy. In the remaining 63 patients, the management was non-operative: expectant strategy alone (n = 52), transcatheter embolisation (n = 5), partial splenectomy (n = 2), splenic repair (n = 2) and ultrasound-guided haematoma aspiration (n = 2). The prevalence of cases managed non-operatively significantly (p = 0.0134) increased over the five periods: while no case was managed non-operatively in 1970–1979, this strategy was successfully applied in slightly less than 50% of cases in 2010–2022 (figure 3).

Nine patients with a severe splenic rupture score (6 female and 3 male subjects aged 15 to 29 years, median 20 years) died [30, 43, 70, 83, 93, 101, 126, 129]: six had been admitted with signs of irreversible circulatory shock; the other three died after initial fluid resuscitation and urgent splenectomy. Fatal cases were temporally distributed as follows: 0 in 1970–1979, 2 in 1980–1989, 4 in 1990–1999, 1 in 2000–2009 and 2 in 2010–2022.

An underlying haematological disease was observed in 6 (21%) of the 29 patients with splenic infarction: hereditary spherocytosis in 4 and sickle cell trait in 2. One patient had coeliac disease. Furthermore, one patient concomitantly had Crohn’s disease, sacroiliitis and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Finally, one female subject was taking hormonal contraception. Interestingly, a transient elevation of the antiphospholipid level was noted in one patient.

The management was non-operative in all 29 patients. A splenectomy was performed one month or more after diagnosis in two patients with spherocytosis and in one patient with long-lasting abdominal pain and fatigue. None of the 29 patients died.

This systematic review of the literature focuses on two complications of mononucleosis [1–3]: splenic rupture and splenic infarction. The results may be summarised as follows. Both rupture and infarction predominantly occur in males, usually 15 to 30 years of age, and present one to three weeks after the onset of mononucleosis symptoms (which are mild in about 20% of cases) with acute abdominal pain, which is mostly diffuse (but often predominates in the left upper quadrant), and left shoulder pain. Haemodynamic instability secondary to a circulatory shock occurs in approximately one-third of cases of splenic rupture, which is still potentially fatal. Moreover, cases with infarction quite frequently have a pre-existing haematological condition such as spherocytosis or sickle cell trait. Finally, and especially clinically relevant, a spleen-preserving treatment is nowadays a viable alternative to splenectomy in mononucleosis-associated splenic rupture.

The cases included in this review were categorised as minor, moderate or severe on the basis of the three-point scoring system recommended by the World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) for patients with splenic trauma [12]. In the patients with Epstein-Barr virus-associated splenic rupture included in this analysis, this scoring system, which is simpler than the five-point spleen injury scale endorsed by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma and includes both clinical and imaging data [185], correlates well with required management.

Given the rarity of mononucleosis-associated splenic rupture, there is no clear consensus on treatmentstrategy. Non-operative management of haemodynamically stable cases, i.e. with a minor or moderate WSES rupture score, is currently the standard of care. In addition to an expectant attitude, non-operative management currently includes splenic artery embolisation [6–8, 117, 186]. Partial splenectomy and splenic repair are no longer recommended [187]. The recommended treatment must be approached with caution given the risk of ongoing bleeding and the potential for late rupture. These patients should be cared for by an experienced multidisciplinary team, with physical activity restriction after discharge. Specifically, no activity more vigorous than walking is recommended until splenomegaly has resolved on clinical examination, followed by a period of no contact sports for six months or until the splenic architecture normalises on imaging evaluation. In view of radiation concerns with CT scans, ultrasound should be the main imaging modality in children, adolescents and women of childbearing age [188].

In splenectomised patients, prevention of infections is crucial. Recommended methods to decrease the infection risk include patient education, vaccination and antimicrobial prophylaxis [7, 9]. Although this review challenges the long-standing belief [4, 28] that palpation may induce mononucleosis-associated splenic rupture, it still seems judicious to avoid vigorous abdominal palpation in this setting.

Generally, splenic infarction is an uncommon diagnosis [5, 189]. Thromboembolism ―either of cardiovascular origin or as the result of a thrombophilia― and a rapidly enlarging spleen ―such as in the case of oncological or non-oncological haematological diseases and acute infections― are the main causes. The results of our review suggest that mononucleosis-associated splenic infarction is often not caused by the Epstein-Barr virus infection alone but also by a pre-existing haematological condition. A high index of suspicion for splenic infarction is appropriate in subjects with the mentioned predisposing conditions presenting with left upper abdominal pain, with or without associated left shoulder pain. The data of this review does not support the use of the lactatedehydrogenase test as a diagnostic tool in cases with suspected infarction. The most appropriate diagnostic imaging is CT with intravenous contrast [5]. Regrettably, Doppler ultrasound is of limited diagnostic value.

The main limitation of this systematic review relates to the rarity of these two complications. Hence, we collected information from cases published between 1970 and 2022, which were sometimes not thoroughly documented. Three well-accepted databases and Google Scholar were used for our literature search. It seems to us highly improbable that substantially different results would have been obtained if additional databases had been searched. Furthermore, the recommended treatment strategy does not arise from well-designed studies but is mainly extrapolated from current guidelines on the management of traumatic splenic rupture [6–8]. The main strength of the study relates to the relatively high number of included cases. Furthermore, this is the first report which investigates the literature on mononucleosis-associated splenic infarction.

In conclusion, this systematic review of the literature documents that, like with traumatic splenic rupture, splenic preservation is increasingly common in the management of mononucleosis-associated splenic rupture, with mainly good success. The treatment strategy is dictated by haemodynamic parameters. Sadly, even in the third millennium, this disease is still occasionally fatal.

The data supporting the current analysis can be found on the data repository Zenodo (https://zenodo.org/record/7711236).

JMAT, BG, MGB, GPM, SAGL and PC designed and contributed to the systematic review; JMAT and BG performed the literature search, the selection of cases, the data extraction and the evaluation of comprehensiveness; JMAT entered the data into a worksheet, BG verified the accuracy of data entry; JMAT and BG performed the data analysis; GPM supervised the literature search, the selection of cases, the data extraction, the evaluation of comprehensiveness, data entry, accuracy of data entry and data analysis; JMAT, BG, IH, MGB and SAGL drafted the article, all other authors critically reviewed the article before submission.

SAGL is the current recipient of research grants from Fonds de perfectionnement, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne, Switzerland; Fondation SICPA, Prilly, Switzerland; Fondazione Dr. Ettore Balli, Bellinzona, Switzerland; Fondazione per il bambino malato della Svizzera italiana, Bellinzona, Switzerland; and Frieda Locher-Hofmann Stiftung, Zürich, Switzerland.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

1. Jenson HB. Epstein-Barr virus. Pediatr Rev. 2011 Sep:375–83. 10.1542/pir.32.9.375

2. Vouloumanou EK, Rafailidis PI, Falagas ME. Current diagnosis and management of infectious mononucleosis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2012 Jan:14–20.

3. Renzulli P, Hostettler A, Schoepfer AM, Gloor B, Candinas D. Systematic review of atraumatic splenic rupture. Br J Surg. 2009 Oct:1114–21. 10.1002/bjs.6737

4. Jenson HB. Acute complications of Epstein-Barr virus infectious mononucleosis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2000 Jun:263–8.

5. Antopolsky M, Hiller N, Salameh S, Goldshtein B, Stalnikowicz R. Splenic infarction: 10 years of experience. Am J Emerg Med. 2009 Mar:262–5. 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.02.014

6. Cocanour CS. Blunt splenic injury. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2010 Dec:575–81.

7. Williamson J. Splenic injury: diagnosis and management. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2015 Apr:204–6.

8. Hildebrand DR, Ben-Sassi A, Ross NP, Macvicar R, Frizelle FA, Watson AJ. Modern management of splenic trauma. BMJ. 2014 Apr; apr02 3:g1864.

9. Squire JD, Sher M. Asplenia and hyposplenism: an underrecognized immune deficiency. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2020 Aug:471–83.

10. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann T, Mulrow CD, et al. Mapping of reporting guidance for systematic reviews and meta-analyses generated a comprehensive item bank for future reporting guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020 Feb;:60–8.

11. Shapiro MF, Greenfield S. The complete blood count and leukocyte differential count. An approach to their rational application. Ann Intern Med. 1987 Jan:65–74.

12. Coccolini F, Fugazzola P, Morganti L, Ceresoli M, Magnone S, Montori G, et al. The World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) spleen trauma classification: a useful tool in the management of splenic trauma. World J Emerg Surg. 2019 Jun:30.

13. Vismara SA, Lava SA, Kottanattu L, Simonetti GD, Zgraggen L, Clericetti CM, et al. Lipschütz’s acute vulvar ulcer: a systematic review. Eur J Pediatr. 2020 Oct:1559–67.

14. Buonocore E. Case report. Angiographic findings in splenic rupture secondary to infectious mononucleosis. J Tenn Med Assoc. 1970 Jul:576–8.

15. Rawsthorne GB, Cole TP, Kyle J. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in infectious mononucleosis. Br J Surg. 1970 May:396–8.

16. Hyun BH, Varga CF, Rubin RJ. Spontaneous and pathologic rupture of the spleen. Arch Surg. 1972 May:652–7.

17. Seibold H, Rasin L, Michot F. Spontane Milzruptur bei infektiöser Mononukleose [Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis] [German.]. Med Klin. 1972 Dec:1623–5.

18. Srivastava KP, Quinlan EC, Casey TV. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen secondary to infectious mononucleosis. Int Surg. 1972 Feb:171–3.

19. Daneshbod K, Liao KT. Hyaline degeneration of splenic follicular arteries in infectious mononucleosis: histochemical and electron microscopic studies. Am J Clin Pathol. 1973 Apr:473–9.

20. Gillet M, Pages C, Barbier A, Narboni G, Camelot G, Grandmottet P. Rupture de rate et mononucléose infectieuse [Splenic rupture and infectious mononucleosis]. Med Chir Dig. 1974:105–7.

21. McCurdy JA Jr, Major. Life-threatening complications of infectious mononucleosis. Laryngoscope. 1975 Sep:1557–63.

22. Lee PW, Whittaker M, Hall TJ. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in infectious mononucleosis. Postgrad Med J. 1976 Nov:725–6.

23. Bourgeois H, Baudoux M, Guillan J. Rupture spontanée de rate révélatrice d’une mononucléose infectieuse [Spontaneous rupture of the spleen revealing infectious mononucleosis]. Nouv Presse Med. 1977 Nov:3642.

24. McMahon MJ, Lintott JD, Mair WS, Lee PW, Duthie JS. Occult rupture of the spleen. Br J Surg. 1977 Sep:641–3.

25. Aung MK, Goldberg M, Tobin MS. Splenic rupture due to infectious mononucleosis. Normal selective arteriogram and peritoneal lavage. JAMA. 1978 Oct:1752–3.

26. Gray R. Rupture of the spleen in a patient with a perforated duodenal ulcer and infectious mononucleosis. Postgrad Med J. 1978 Jan:51–5.

27. Pace T. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen complicating infectious mononucleosis—a GP’s view. J R Nav Med Serv. 1978:162–6.

28. Rutkow IM. Rupture of the spleen in infectious mononucleosis: a critical review. Arch Surg. 1978 Jun:718–20.

29. Enck RE, Woll JE. Splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis with circulating histiocytes. N Y State J Med. 1979 Jan:96–7.

30. Bell JS, Mason JM. Sudden death due to spontaneous rupture of the spleen from infectious mononucleosis. J Forensic Sci. 1980 Jan:20–4. 10.1520/JFS10930J

31. Johnson MA, Cooperberg PL, Boisvert J, Stoller JL, Winrob H. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis: sonographic diagnosis and follow-up. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1981 Jan:111–4.

32. Hallstrom SW, Bonnabeau RC Jr. Rupture of the spleen in infectious mononucleosis. Am Fam Physician. 1981 Jul:135–6.

33. Lovaas M. Ruptured spleen in a boxer with infectious mononucleosis. Minn Med. 1981 Aug:461–2.

34. Miller KB, Kuligowska E, Rich DH. Ultrasonic demonstration of splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. J Clin Ultrasound. 1981:519–20.

35. Miranti JP, Rendleman DF. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen as the presenting event in infectious mononucleosis. J Am Coll Health Assoc. 1981 Oct:96.

36. Holt P, Reis I, Benson EA. Rupture of the spleen in infectious mononucleosis. J Infect. 1982 Jan:87–8. 10.1016/S0163-4453(82)91365-2

37. Mobley HB. Infectious mononucleosis with splenic rupture: a surgical dilemma. Tex Med. 1982 Dec:66–7.

38. Patel JM, Rizzolo E, Hinshaw JR. Spontaneous subcapsular splenic hematoma as the only clinical manifestation of infectious mononucleosis. JAMA. 1982 Jun:3243–4. 10.1001/jama.1982.03320480059027

39. Scheele C, Döhrmann D. Spontanruptur der Milz bei infektiöser Mononucleose [Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in infectious mononucleosis] [German.]. Chirurg. 1984 Jul:480–1.

40. Vezina WC, Nicholson RL, Cohen P, Chamberlain MJ. Radionuclide diagnosis of splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Clin Nucl Med. 1984 Jun:341–4.

41. Heldrich FJ, Sainz D. Infectious mononucleosis with splenic rupture [articolo J>inserito]. Md State Med J. 1984 Jan:40–1.

42. Höfig G, Dettbarn M. Spontanruptur der Milz bei infektiöser Mononukleose [Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in infectious mononucleosis] [German.]. Zentralbl Chir. 1985:1471–3.

43. Jones TJ, Pugsley WG, Grace RH. Fatal spontaneous rupture of the spleen in asymptomatic infectious mononucleosis. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1985 Dec:398.

44. Peters RM, Gordon LA. Nonsurgical treatment of splenic hemorrhage in an adult with infectious mononucleosis. Case report and review. Am J Med. 1986 Jan:123–5.

45. Stahlknecht T, Majewski A. Das asymptomatische subkapsuläre Milzhämatom bei der infektiösen Mononukleose (M. Pfeiffer) [Asymptomatic subcapsular splenic hematoma in infectious mononucleosis (Pfeiffer disease)] [German.]. Rontgenblatter. 1986 Sep:264–5.

46. Frecentese DF, Cogbill TH. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Am Surg. 1987 Sep:521–3.

47. McLean ER Jr, Diehl W, Edoga JK, Widmann WD. Failure of conservative management of splenic rupture in a patient with mononucleosis. J Pediatr Surg. 1987 Nov:1034–5. 10.1016/S0022-3468(87)80512-2

48. Murat J, Kaisserian G, Boustani R, Grossetti D. Rupture spontanée tardive de rate au cours d’une mononucléose infectieuse [Late spontaneous rupture of the spleen in infectious mononucleosis]. Presse Med. 1987 Sep:1487.

49. Rotolo JE. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Am J Emerg Med. 1987 Sep:383–5. 10.1016/0735-6757(87)90386-X

50. Wallmann P, Hablützel K, Baudenbacher R, Kehl O. Traumatische Milzruptur bei infektiöser Mononukleose: milzerhaltende Therapie [Traumatic splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis: spleen-preserving therapy] [German.]. Schweiz Rundsch Med Prax. 1987 Nov:1260–1.

51. Moolenaar W, Peters WG, Bolk JH. Fever, lymphadenopathy and shock in a 16-year-old girl. Neth J Med. 1988 Aug:37–40.

52. Ormann W, Hopf G. Spontane Milzruptur bei infektiöser Mononucleose - Organerhaltende Operation mittels Fibrinklebung [Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis--organ-sparing operation using fibrin glue]. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1988;373(4):240-242. German. doi: .

53. Vitello J. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in infectious mononucleosis: a failed attempt at nonoperative therapy. J Pediatr Surg. 1988 Nov:1043–4. 10.1016/S0022-3468(88)80024-1

54. Brown J, Marchant B, Zumla A. Spontaneous subcapsular splenic haematoma formation in infectious mononucleosis. Postgrad Med J. 1989 Jun:427–8.

55. Gauderer MW, Stellato TA, Hutton MC. Splenic injury: nonoperative management in three patients with infectious mononucleosis. J Pediatr Surg. 1989 Jan:118–20. 10.1016/S0022-3468(89)80314-8

56. Konvolinka CW, Wyatt DB. Splenic rupture and infectious mononucleosis. J Emerg Med. 1989:471–5.

57. Neudorfer H, Hesse H, Simma W. Spontane Milzruptur bei infektiöser Mononukleose [Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in infectious mononucleosis] [German.]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1989 Dec:2006–7.

58. Azzario G, Clerico G, Veglio M, Bosco L. Rottura spontanea di milza in corso di mononucleosi infettiva [Spontaneous rupture of the spleen during infectious mononucleosis]. Minerva Chir. 1990 Apr:611–3.

59. Martínez Ruiz M, Boned J, Toral JR, Llobell G, Peralba JI. Tratamiento conservador en la rotura espontánea de bazo por mononucleosis infecciosa [Conservative treatment in spontaneous splenic rupture due to infectious mononucleosis]. Med Interna. 1990:578–80.

60. Safran D, Bloom GP. Spontaneous splenic rupture following infectious mononucleosis. Am Surg. 1990 Oct:601–5.

61. Witte D, Gammill SL. Radiology case of the month. Spontaneous splenic rupture in a patient with infectious mononucleosis. J Tenn Med Assoc. 1990 Apr:189.

62. Fengler JD, Baumgarten R, Jacob H, Kopp S. Milzruptur bei infektiöser Mononukleose [Splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis] [German.]. Z Arztl Fortbild (Jena). 1991 Jul:663–5.

63. Fleming WR. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Aust N Z J Surg. 1991 May:389–90.

64. Radford PJ, Wheatley T, Clark C. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Br J Clin Pract. 1991:293. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.1991.tb08880.x

65. Lin JH, Cespedes E. Splenic rupture as an infectious mononucleosis complication. Kao Hsiung I Hsueh Ko Hsueh Tsa Chih. 1992 Jun:332–7.

66. Pasieka JL, Preshaw RM. Conservative management of splenic injury in infectious mononucleosis. J Pediatr Surg. 1992 Apr:529–30. 10.1016/0022-3468(92)90357-D

67. Purkiss SF. Splenic rupture and infectious mononucleosis-splenectomy, splenorrhaphy or non operative management? J R Soc Med. 1992 Aug:458–9. 10.1177/014107689208500812

68. Putterman C, Lebensart P, Almog Y. Sonographic diagnosis of spontaneous rupture of the spleen in infectious mononucleosis: case report and review of the literature. Isr J Med Sci. 1992 Nov:801–4.

69. Torné Cachot J, Encinas X, Alarcón JL, Blanch J. Rotura espontánea del bazo en la mononucleosis infecciosa [Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in infectious mononucleosis]. Rev Clin Esp. 1992 May:428–9.

70. Ali J. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in patients with infectious mononucleosis. Can J Surg. 1993 Feb:49–52.

71. Evrard S, Mendoza-Burgos L, Mutter D, Vartolomei S, Marescaux J. Management of splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Case report. Eur J Surg. 1993 Jan:61–3.

72. Mortelmans L, Populaire J. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Acta Chir Belg. 1993:193–5.

73. Nicholl JE, McAdam G, Donaldson DR. Three cases of early spontaneous splenic rupture associated with acute viral infection. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1993 Dec:351–2.

74. Baldonedo Cernuda RF, Alvarez Pérez JA, Pérez Alvarez S, Palacios Fernández E, Monte Colunga C. Rotura patológica de bazo por mononucleosis infecciosa [Pathologic rupture of the spleen caused by infectious mononucleosis]. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1994 Dec:927–9.

75. Garcia-Diaz Jde D, Martel J. Hematoma esplénico como complicación de mononucleosis infecciosa. Evolución favorable con actitud conservadora [Splenic hematoma as a complication of infectious mononucleosis. A favorable evolution with a conservative approach]. Med Interna. 1994:464–5.

76. Basan B, Lafrenz M, Ziegler K, Klemm G. Milzrupture bei infektiöser Mononukleose [Splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis] [German.]. Z Arztl Fortbild (Jena). 1995 Dec:725–8.

77. Gálvez MC, Collado A, Díez F, Laynez F. Rotura esplénica espontánea en el seno de mononucleosis infecciosa. Resolución con tratamiento conservador [Spontaneous splenic rupture during infectious mononucleosis. Resolution with conservative treatment]. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 1995:440–1.

78. Gordon MK, Rietveld JA, Frizelle FA. The management of splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Aust N Z J Surg. 1995 Apr:247–50.

79. MacGowan JR, Mahendra P, Ager S, Marcus RE. Thrombocytopenia and spontaneous rupture of the spleen associated with infectious mononucleosis. Clin Lab Haematol. 1995 Mar:93–4.

80. Paar WD, Look MP, Robertz Vaupel GM, Kreft B, Hirner A, Sauerbruch T. Non-operative management in a case of spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis [sarticolo completo J inserito]. Z Gastroenterol. 1995 Jan:13–4.

81. Schuler JG, Filtzer H. Spontaneous splenic rupture. The role of nonoperative management. Arch Surg. 1995 Jun:662–5.

82. Tosato F, Passaro U, Vasapollo LL, Folliero G, Paolini A. Subcapsular splenic hematoma due to infectious mononucleosis. Riv Eur Sci Med Farmacol. 1995:157–9.

83. Birkinshaw R, Saab M, Gray A. Spontaneous splenic rupture: an unusual cause of hypovolaemia. J Accid Emerg Med. 1996 Jul:289–91.

84. Reyes Cerezo M, Muñoz Boo JL, García Ferris G, Escudero Marchante JM, Jiménez Gonzalo FJ, Medina Pérez M. Rotura espontánea del bazo en la mononucleosis infecciosa [Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis]. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1996 Mar:230–1.

85. Semrau F, Kühl RJ, Ritter K. Ruptured spleen and autoantibodies to superoxide dismutase in infectious mononucleosis. Lancet. 1996 Apr:1124–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90326-8

86. Asgari MM, Begos DG. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis: a review. Yale J Biol Med. 1997:175–82.

87. Baraké H, Guillaume MP, Mendes da Costa P. Traitement chirurgical conservateur d’une rupture spontanée de la rate au décours d’une mononucléose infectieuse. Rapport d’un cas et revue de la littérature [Conservative surgical treatment of a spontaneous splenic rupture during infectious mononucleosis. Case report and literature review]. Rev Med Brux. 1997 Dec:381–4.

88. Conthe P, Cilleros CM, Urbeltz A, Escat J, Gilsanz C. Ruptura esplénica espontánea: tratamiento quirúrgico o conservador? [Spontaneous splenic rupture: surgical or conservative treatment?]. Med Interna. 1997:625–6.

89. Nouri M, Nohra R, Nouri M. Rupture spontanée de la rate et mononucléose infectieuse [Spontaneous rupture of the spleen and infectious mononucleosis]. Ann Fr Anesth Réanim. 1997:53–4. 10.1016/S0750-7658(97)84278-5

90. Blaivas M, Quinn J. Diagnosis of spontaneous splenic rupture with emergency ultrasonography. Ann Emerg Med. 1998 Nov:627–30. 10.1016/S0196-0644(98)70046-0

91. Chen CC, Hsiao CC, Huang CB. Spleen rupture in infectious mononucleosis: report of one case. Zhonghua Min Guo Xiao Er Ke Yi Xue Hui Za Zhi. 1998:198–9.

92. Lambotte O, Debord T, Plotton N, Roué R. Hématome splénique au cours d’une mononucléose infectieuse: abstention chirurgicale [Splenic hematoma during infectious mononucleosis: non-operative treatment]. Presse Med. 1998 Feb:209.

93. Lippstone MB, Sekula-Perlman A, Tobin J, Callery RT. Spontaneous splenic rupture and infectious mononucleosis in a forensic setting. Del Med J. 1998 Oct:433–7.

94. Pullyblank AM, Currie LJ, Pentlow B. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen as a result of infectious mononucleosis in two siblings. Hosp Med. 1999 Dec:912–3.

95. Schwarz M, Zaidenstein L, Freud E, Neuman M, Ziv N, Kornreich L, et al. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis: conservative management with gradual percutaneous drainage of a subcapsular hematoma. Pediatr Surg Int. 1999:139–40.

96. Steiner-Linder A, Ballmer PE, Haller A. Konservatives Management bei spontaner Milzruptur als Komplikation einer Mononucleosis infectiosa: zwei Fallberichte und Literaturübersicht [Conservative management of spontaneous splenic rupture as a complication of infectious mononucleosis: two case reports and literature review] [German.]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 2000 Nov:1695–8.

97. Illescas T J, Tagle A M, Castro P E, Casttle J, Scavino Levy Y, Valdez F L. Ruptura espontánea del bazo por mononucleosis: reporte de un caso [spontaneous spleen rupture in mononucleosis infectious disease]. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2000:434–9.

98. Badura RA, Oliveira O, Palhano MJ, Borregana J, Quaresma J; Robert A. Badura, Olivia Oliveira. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen as presenting event in infectious mononucleosis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2001:872–4.

99. Jesús Redondo M, Angel Sánchez L, Oleaga A, Elorza R, Luis Ferrero O. Síncope y anemia aguda en mujer joven con fiebre y adenopatías [Syncope and acute anemia in a young woman with fever and lymph node enlargement]. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2001 Feb:75–6. 10.1016/S0213-005X(01)72564-5

100. Roscoe M. Managing a rare cause of death in infectious mononucleosis. JAAPA. 2001 Jul:52–5.

101. Rothwell S, McAuley D. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Emerg Med (Fremantle). 2001 Sep:364–6.

102. Chapman AL, Watkin R, Ellis CJ. Abdominal pain in acute infectious mononucleosis. BMJ. 2002 Mar:660–1.

103. Al-Mashat FM, Sibiany AM, Al Amri AM. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2003 May:84–6.

104. Campos Franco J, Alende Sixto R, Pazos González G, Bustamante Montalvo M, Rey García J, González Quintela A. Evolución favorable con tratamiento conservador de la rotura esplénica espontánea durante una mononucleosis infecciosa [Favorable evolution with conservative therapy in spontaneous spleen rupture during infectious mononucleosis]. Rev Clin Esp. 2003 Jan:50.

105. Carrillo Herranz A, Ramos Sánchez N, Sánchez Pérez I, Lozano Giménez C. Rotura espontánea de bazo secundaria a mononucleosis infecciosa [Spontaneous splenic rupture secondary to infectious mononucleosis]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2003 Feb:199–200. 10.1157/13042965

106. Coulier B, Sergeant L, Horgnies A. Spontaneous splenic capsule rupture complicating infectious mononucleosis. JBR-BTR. 2003:243.

107. Delle Monache G, Orlando D, Frassanito S, Sciarra R, Rinaldi MT. Rottura spontanea di milza come complicanza di mononucleosi infettiva: caso clinico [Spontaneous splenic rupture as complication of infective mononucleosis: a clinical case]. Ann Ital Med Int. 2003:104–6.

108. Gayer G, Zandman-Goddard G, Kosych E, Apter S. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen detected on CT as the initial manifestation of infectious mononucleosis. Emerg Radiol. 2003 Apr:51–2.

109. Greco L, De Gennaro E, Degara A, Papa U. Rottura splenica spontanea in corso di mononuleosi infettiva acuta: descrizione di un caso [Spontaneous splenic rupture due to infectious acute mononucleosis: case report]. Ann Ital Chir. 2003:589–91.

110. Halkic N, Jayet C, Pezzetta E, Mosimann F. Spontaneous splenic haematoma in a teenager with infectious mononucleosis. Chir Ital. 2003:929–30.

111. Kwok AM. Atraumatic splenic rupture after cocaine use and acute Epstein-Barr virus infection: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2019 Dec:433–42.

112. Stockinger ZT. Infectious mononucleosis presenting as spontaneous splenic rupture without other symptoms. Mil Med. 2003 Sep:722–4. 10.1093/milmed/168.9.722

113. Warwick RJ, Wee B, Kirkpatrick D, Finnegan OC. Infectious mononucleosis, ruptured spleen and Cullen’s sign. Ulster Med J. 2003 Nov:111–3.

114. Dieter RA Jr. Infectious mononucleosis (IM) associated rupture of the spleen. Mil Med. 2004 Jan:v.

115. Halkic N, Vuilleumier H, Qanadli SD. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis treated by embolization of the splenic artery. Can J Surg. 2004 Jun:221–2.

116. Statter MB, Liu DC. Nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury in infectious mononucleosis. Am Surg. 2005 May:376–8. 10.1177/000313480507100502

117. Stephenson JT, DuBois JJ. Nonoperative management of spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2007 Aug:e432–5.

118. Wallis S. It started with a kiss (perhaps). Lancet. 2007 Dec:2068.

119. Khoo SG, Ullah I, Manning KP, Fenton JE. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2007 May:300–1. 10.1177/014556130708600518

120. Shah M, Muquit S, Azam B. Infective splenic rupture presenting with symptoms of a pulmonary embolism. Emerg Med J. 2008 Dec:855–6.

121. Sweat JA, Dort JM, Smith RS. Splenic embolization for splenic laceration in a patient with mononucleosis. Am Surg. 2008 Feb:149–51. 10.1177/000313480807400213

122. Suffin DM, Jayasingam R, Melillo NG, Sensakovic JW. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Hosp Physician. 2009;:29–32.

123. Toderescu P, García Rioja Y. Toderescu P García Rioja Y. Rotura esplénica: una de las complicaciones más graves de la mononucleosis infecciosa. A propósito de un caso [Splenic rupture: one of the most serious complications of infectious mononucleosis. A case report] [Spanish]. Semergen. 2009:55–6.

124. Akinli AS, Leriche C, Pauls S, Haenle MM, Kratzer W. Hemorrhage into a preformed splenic cyst as a rare complication of epstein-barr virus infection. Ultraschall Med. 2010 Oct:522–4.

125. Bonsignore A, Grillone G, Soliera M, Fiumara F, Pettinato M, Calarco G, et al. Rottura splenica “occulta” in paziente con mononucleosi infettiva [Occult rupture of the spleen in a patient with infectious mononucleosis]. G Chir. 2010 Mar:86–90.

126. Pfäffli M, Wyler D. Letale atraumatische Milzruptur infolge infektiöser Mononukleose [Lethal atraumatic splenic rupture due to infectious mononucleosis] [German.]. Arch Kriminol. 2010:195–200.

127. Martínez Lesquereux L, Rojo Y, Martínez Castro J, Gamborino Caramés E, Beiras Torrado A. Rotura esplénica espontánea como manifestación inicial de una mononucleosis infecciosa [Spontaneous rupture of the spleen as a first sign of infectious mononucleosis]. Cir Esp. 2011 Apr:250–1.

128. Bouliaris K, Karangelis D, Daskalopoulos M, Spanos K, Fanariotis M, Giaglaras A. Hemorrhagic shock as a sequela of splenic rupture in a patient with infectious mononucleosis: focus on the potential role of salicylates. Case Rep Med. 2012;:497820.

129. Rinderknecht AS, Pomerantz WJ. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012 Dec:1377–9.

130. Won AC, Ethell A. Spontaneous splenic rupture resulted from infectious mononucleosis. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2012:97–9.

131. Jenni F, Lienhardt B, Fahrni G, Yuen B. Nonsurgical management of complicated splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Am J Emerg Med. 2013 Jul:1152.e5–6.

132. Sivakumar P, Dubrey SW, Goel S, Adler L, Challenor E. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen resulting from infectious mononucleosis. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2013 Nov:652.

133. Koebrugge B, Geertsema D, de Jong M, Jager G, Bosscha K. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. JBR-BTR. 2013:234–5.

134. Landmann T, Charisius C. Patient hat Halsschmerzen und leichtes Fieber: Wie dramatisch das ist, verrät die Sonografie [Patient with sore throat and mild fever: how dramatic this is, ultrasound diagnosis clarifies]. MMW Fortschr Med. 2013;155 Spec No 1(1):7. German.

135. Busch D, Hilswicht S, Schöb DS, von Trotha KT, Junge K, Gassler N, et al. Fulminant Epstein-Barr virus - infectious mononucleosis in an adult with liver failure, splenic rupture, and spontaneous esophageal bleeding with ensuing esophageal necrosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014 Feb:35.

136. Lam GY, Chan AK, Powis JE. Possible infectious causes of spontaneous splenic rupture: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014 Nov:396.

137. Ng E, Lee M. Splenic rupture: a rare complication of infectious mononucleosis. Med J Aust. 2014 Oct:480.

138. Raman L, Rathod KS, Banka R. Chest pain in a young patient: an unusual complication of Epstein-Barr virus. BMJ Case Rep. 2014 Mar; mar31 1:bcr2013201606.

139. Sergent SR, Johnson SM, Ashurst J, Johnston G. Epstein-Barr virus-associated atraumatic spleen laceration presenting with neck and shoulder pain. Am J Case Rep. 2015 Oct;:774–7. 10.12659/AJCR.893919

140. Barnwell J, Deol PS. Atraumatic splenic rupture secondary to Epstein-Barr virus infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2017 Jan;:bcr2016218405.

141. Cortés-González AS, García-Torres V, Vázquez-Martínez RM, Cortés-Trujillo NY. Suarez-Cruz Uziel. (2017). Splenic rupture associated with thrombocytopenic purpura caused by infectious mononucleosis. Case report. Case Rep. 2017:70–6.

142. Dessie A, Binder W. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen due to infectious mononucleosis. R I Med J (2013). 2017;100(7):33-35.

143. Ioannides D, Davies M, Kluzek S. Confusion and abdominal symptoms following a rugby tackle. BMJ Case Rep. 2017 Sep;:bcr2017222160.

144. Martín-Lagos Maldonado A, Gallart-Aragón T. Rotura esplénica atraumática [Atraumatic splenic rupture]. Rev Andal Patol Digest. 2018:55–6.

145. Baker CR, Kona S. Spontaneous splenic rupture in a patient with infectious mononucleosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2019 Sep:e230259.

146. Frank EA, LaFleur JR, Okosun S. Nontraumatic splenic rupture due to infectious mononucleosis. J Acute Care Surg. 2019:69–71.

147. Gilmartin S, Hatton S, Ryan J. Teenage kicks: splenic rupture secondary following infectious mononucleosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2019 May:e229030.

148. Mk S, S S, H VN. S S, H VN. Spontaneous splenic rupture in a case of infectious mononucleosis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2019 Jul:90–2.

149. Tanael M, Saul S. Navigating the management of an F-16 pilot following spontaneous splenic rupture. Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 2019 Dec:1061–3.

150. Halliday M, Ingersoll J, Alex J. Atraumatic splenic rupture after weight lifting in a patient presenting with left shoulder pain. Mil Med. 2020 Dec:e2918–2200.

151. Ruymbeke H, Schouten J, Sermon F. EBV: not your everyday benign virus. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2020:485–7.

152. Solar MC, Benoit E, Cerda MF, Agüeroa R. Rotura del bazo espontánea en mononucleosis infecciosa: revisión de la literatura a partir de un caso clínico [Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in infectious mononucleosis: review of the literature and a case report]. Rev Confl. 2020:161–4.

153. Gatica C, Soffia P, Charles R, Vicentela A. [Spontaneous splenic rupture secondary to infectious mononucleosis]. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2021 Apr:292–6.

154. Hicks J, Boswell B, Noble V. Traumatic splenic laceration: A rare complication of infectious mononucleosis in an athlete. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2021 May:250–1.

155. Chóliz-Ezquerro J, Allué-Cabañuz M, Martínez-Germán A. Hypovolemic shock due to nontraumatic splenic rupture in adolescent patient. A rare complication of infectious mononucleosis [English.]. Cir Cir. 2021:844–5.

156. Brichkov I, Cummings L, Fazylov R, Horovitz JH. Nonoperative management of spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis: the role for emerging diagnostic and treatment modalities. Am Surg. 2006 May:401–4. 10.1177/000313480607200507

157. Tchouankeo S, Gérard AC, Colin IM. Spontaneous Spleen Rupture: An Unexpected Consequence of Infectious Mononucleosis - A Case Report. Front Med Case Rep. 2020:1–10.

158. Farley DR, Zietlow SP, Bannon MP, Farnell MB. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen due to infectious mononucleosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1992 Sep:846–53. 10.1016/S0025-6196(12)60822-2

159. Khan S, Saud S, Khan I, Prabhu S. Epstein Barr Virus-induced Antiphospholipid Antibodies Resulting in Splenic Infarct: A Case Report. Cureus. 2019 Feb:e4119.

160. Trevenzoli M, Sattin A, Sgarabotto D, Francavilla E, Cattelan AM; Marco Trevenzoli, Andrea Sattin, Di. Splenic infarct during infectious mononucleosis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2001:550–1.

161. García-Vázquez J, Plácido Paias R, Portillo Márquez M. Splenic infarction due a common infection. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2018;36(9):593-595. English, Spanish. doi: . 10.1016/j.eimce.2018.07.002

162. Thida AM, Ilonzo I, Gohari P. Multiple splenic infarcts: unusual presentation of hereditary spherocytosis associated with acute Epstein-Barr virus infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2020 Jul:e235131.

163. Pervez H, Tameez Ud Din A, Khan A. A mysterious case of an infarcted spleen due to kissing disease: a rare entity. Cureus. 2020 Jan:e6700.

164. Suzuki Y, Shichishima T, Mukae M, Ohsaka M, Hayama M, Horie R, et al. Splenic infarction after Epstein-Barr virus infection in a patient with hereditary spherocytosis. Int J Hematol. 2007 Jun:380–3.

165. Gang MH, Kim JY. Splenic infarction in a child with primary Epstein-Barr virus infection. Pediatr Int. 2013 Oct:e126–8.

166. Bhattarai P, Pierr L, Adeyinka A, Sadanandan S. Splenic Infarct: A Rare Presentation in a Pediatric Patient. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2014:1017–9. 10.31729/jnma.2805

167. Symeonidis A, Papakonstantinou C, Seimeni U, Sougleri M, Kouraklis-Symeonidis A, Lambropoulou-Karatza C, et al. Non hypoxia-related splenic infarct in a patient with sickle cell trait and infectious mononucleosis. Acta Haematol. 2001:53–6.

168. Li Y, George A, Arnaout S, Wang JP, Abraham GM. Splenic Infarction: An Under-recognized Complication of Infectious Mononucleosis? Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018 Feb:ofy041.

169. Machado C, Melo Salgado J, Monjardino L. The unexpected finding of a splenic infarction in a patient with infectious mononucleosis due to Epstein-Barr virus. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Nov;:bcr2015212428.

170. Suzuki Y, Kakisaka K, Kuroda H, Sasaki T, Takikawa Y. Splenic infarction associated with acute infectious mononucleosis. Korean J Intern Med (Korean Assoc Intern Med). 2018 Mar:451–2.

171. Mackenzie DC, Liebmann O. Identification of splenic infarction by emergency department ultrasound. J Emerg Med. 2013 Feb:450–2.

172. Heo DH, Baek DY, Oh SM, Hwang JH, Lee CS, Hwang JH. Splenic infarction associated with acute infectious mononucleosis due to Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Med Virol. 2017 Feb:332–6.

173. Li Y, Pattan V, Syed B, Islam M, Yousif A. Splenic infarction caused by a rare coinfection of Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014 Sep:636–7.

174. Gavriilaki E, Sabanis N, Paschou E, Grigoriadis S, Mainou M, Gaitanaki A, et al. Splenic infarction as a rare complication of infectious mononucleosis due to Epstein-Barr virus infection in a patient with no significant comorbidity: case report and review of the literature. Scand J Infect Dis. 2013 Nov:888–90.

175. Jeong JE, Kim KM, Jung HL, Shim JW, Kim DS, Shim JY, et al. Acute gastritis and splenic infarction caused by Epstein-Barr Virus. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2018 Apr:147–53.

176. Naviglio S, Abate MV, Chinello M, Ventura A. Splenic infarction in acute infectious mononucleosis. J Emerg Med. 2016 Jan:e11–3.

177. Nofal R, Zeinali L, Sawaf H. Splenic infarction induced by epstein-barr virus infection in a patient with sickle cell trait. J Paediatr Child Health. 2019 Feb:249–51.

178. Benz R, Seiler K, Vogt M. A surprising cause of chest pain. J Assoc Physicians India. 2007 Oct;:725–6.

179. Kim KM, Kopelman RI. Medical mystery: abdominal pain—the answer. N Engl J Med. 2005 Sep:1421–2.

180. Patruno JV, Milross L, Javaid MM. Not Quite a Mono Spot Diagnosis. Splenic Infarction Complicating Infectious Mononucleosis. Am J Med. 2020:S0002-9343(20)31020-31022. doi: .

181. Breuer C, Janssen G, Laws HJ, Schaper J, Mayatepek E, Schroten H, et al. Splenic infarction in a patient hereditary spherocytosis, protein C deficiency and acute infectious mononucleosis. Eur J Pediatr. 2008 Dec:1449–52.

182. Nishioka H, Hayashi K, Shimizu H. Splenic infarction in infectious mononucleosis due to Epstein-Barr virus infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021 Nov:623–5.

183. Reichlin M, Bosbach SJ, Minotti B. Splenic infarction diagnosed by contrast-enhanced ultrasound in infectious mononucleosis – an appropriate diagnostic option: a case report with review of the literature. J Med Ultrasound. 2022 Jan:140–2. 10.4103/jmu.jmu_87_21

184. Ma Z, Wang Z, Zhang X, Yu H. Splenic infarction after Epstein-Barr virus infection in a patient with hereditary spherocytosis: a case report and literature review. BMC Surg. 2022 Apr:136.

185. Kozar RA, Crandall M, Shanmuganathan K, Zarzaur BL, Coburn M, Cribari C, et al.; AAST Patient Assessment Committee. Organ injury scaling 2018 update: Spleen, liver, and kidney [Erratum in: J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;87(2]. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018 Dec:1119–22.

186. Stephenson JT, DuBois JJ. Nonoperative management of spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2007 Aug:e432–5.

187. Ko A, Radding S, Feliciano DV, DuBose JJ, Kozar RA, Morrison J, et al. Near disappearance of splenorrhaphy as an operative strategy for splenic preservation after trauma. Am Surg. 2022 Mar:429–33.

188. Puchalski AL, Magill C. Imaging Gently. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2018 May:349–68.

189. Jaroch MT, Broughan TA, Hermann RE. The natural history of splenic infarction. Surgery. 1986 Oct:743–50.