Burden of disease in patients hospitalised with COVID-19 during the first and second pandemic wave in Switzerland: a nationwide cohort study

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/smw.2023.40068

Claudia

Gregorianoa, Kris

Rafaiszab, Philipp

Schuetzab, Beat

Muellerab, Christoph A.

Fuxac, Anna

Conenac, Alexander

Kutzad

a Medical University Department, Division of General

Internal and Emergency Medicine, Cantonal Hospital Aarau, Aarau, Switzerland

b Department

of Clinical Research, University Hospital Basel, University of Basel, Basel,

Switzerland

cDepartment of Infectious Diseases and Infection Prevention, Cantonal Hospital Aarau,

Aarau, Switzerland

d Division

of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Department of Medicine, Brigham

and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

*

Equally contributing first authors

Summary

AIM OF THE STUDY: The first and second waves of

the COVID-19 pandemic led to a tremendous burden of disease and influenced

several policy directives, prevention and treatment strategies as well as lifestyle

and social behaviours. We aimed to describe trends of hospitalisations with

COVID-19 and hospital-associated outcomes in these patients during the first

two pandemic waves in Switzerland.

METHODS: In this nationwide retrospective cohort

study, we used in-hospital claims data of patients hospitalised with COVID-19

in Switzerland between January 1st and December 31st, 2020. First, stratified

by wave (first wave: January to May, second wave: June to December), we

estimated incidence rates (IR) and rate differences (RD) per 10,000

person-years of COVID-19-related hospitalisations across different age groups

(0–9, 10–19, 20–49, 50–69, and ≥70 years). IR was calculated by counting the

number of COVID-19 hospitalisations for each patient age stratum paired with the

number of persons living in Switzerland during the specific wave period. Second,

adjusted odds ratios (aOR) of outcomes among COVID-19 hospitalisations were

calculated to assess the association between COVID-19 wave and outcomes,

adjusted for potential confounders.

RESULTS: Of 36,517 hospitalisations with

COVID-19, 8,862 (24.3%) were identified during the first and 27,655 (75.7%)

during the second wave. IR for hospitalisations with COVID-19 was highest

during the second wave and among patients above 50 years (50–69 years: first

wave: 31.49 per 10,000 person-years; second wave: 62.81 per 10,000 person-years;

RD 31.32 [95% confidence interval [CI]: 29.56 to 33.08] per 10,000 person-years;

IRR 1.99 [95% CI: 1.91 to 2.08]; ≥70 years: first wave: 88.59 per 10,000

person-years; second wave: 228.41 per 10,000 person-years; RD 139.83 [95% CI: 135.42

to 144.23] per 10,000 person-years; IRR 2.58 [95% CI: 2.49 to 2.67]). While

there was no difference in hospital readmission, when compared with the first

wave, patients hospitalised during the second wave had a lower probability of death

(aOR 0.88 [95% CI: 0.81 to 0.95], ARDS (aOR 0.56 [95% CI: 0.51 to 0.61]), ICU

admission (aOR 0.66 [95% CI: 0.61 to 0.70]), and need for ECMO (aOR 0.60 [95%

CI: 0.38 to 0.92]). LOS was –16.1 % (95% CI: –17.8 to –14.2) shorter during

the second wave.

CONCLUSION: In this nationwide cohort study,

rates of hospitalisations with COVID-19 were highest among adults older than 50

years and during the second wave. Except for hospital readmission, the

likelihood of adverse outcomes was lower during the second pandemic wave, which

may be explained by advances in the understanding of the disease and improved treatment

options.

Introduction

In 2020, Switzerland faced two waves of the

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic in spring

and winter, respectively. At the beginning of the first wave, many European

countries reached their capacity limits of acute and/or intensive care beds for

COVID-19 affected patients requiring inpatient care [1]. Therefore, hospitals

throughout Europe were forced to restore their capacity by postponing elective

treatments and non-emergency surgeries [2, 3]. To address the threat, Swiss authorities

introduced public health demands and restrictions to limit the spread of the

new virus. While during the first wave, policy interventions included

non-pharmacological mitigation measures such as national closures of borders,

schools, non-essential stores and businesses with a nationwide lockdown mid of March

2020, [4] during the second wave, the main non-pharmacological measures

included social distancing, increased testing, and restricted mobility [5, 6].

With cumulating evidence during the second

wave, the antiviral remdesivir was prescribed more frequently [7–9]. In

addition, dexamethasone was prescribed to most hospitalised patients needing

oxygen therapy during the second wave [10]. Moreover, different strategies were

applied regarding the hospitalisation of infected people. While, during the

first wave, most infected people were hospitalised, even with only minor

symptoms, this was no longer the case during the second wave, where criteria

for hospitalisation were far more restrictive and based on clinical parameters [11].

Regardless, given the many infected people, the absolute number of hospitalisations

during the second wave were higher.

As both the

number of hospitalisations with COVID-19 and treatment options varied substantially

between the first and second wave [12], we sought to evaluate epidemiological trends

of COVID-19 related hospitalisations and corresponding in-hospital outcomes across

different age groups using clinical routine data from Switzerland.

Methods

Study design

This

analysis was conducted using a nationwide cohort of patients hospitalised with COVID-19

in Switzerland between January 1st and December 31st

2020. Hospitalisation data was provided by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office

(FSO, Neuchâtel, Switzerland), based on a nationwide compulsory full census of

Swiss hospitals. The dataset includes all Swiss inpatient discharge records

from general hospitals for acute somatic care. Individual-level data on patient

demographics, healthcare utilisation, hospital typology, medical diagnoses, clinical

procedures, and in-hospital patient outcomes were provided. A multi-step anonymisation

procedure ensured patient confidentiality, and an unique patient identifier was

used to ascertain rehospitalisations. Medical diagnoses were coded using the

International Classification of Disease version 10, German Modification

(ICD-10-GM) codes. Open-source census data from the FSO on the Swiss population

size, stratified by age and year, and data from the Swiss Federal Office of

Public Health (FOPH) on the number of positive tests for SARS-CoV-2, stratified

by age and period were obtained to calculate population-based incidence rates (IR)

of hospitalisation with COVID-19. The institutional review board of

Northwestern and Central Switzerland (EKNZ) waived the need for an ethical authorisation

due to the use of exclusively anonymised data (EKNZ Project-ID:

Req-2021-01397). This study adheres to the “Strengthening The Reporting of Observational

Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)” statement [13].

Case ascertainment and study variables

For this

analysis, we included all hospitalisations that were treated with or for COVID-19.

Hospitalisations in special clinics (psychiatric clinics, rehabilitation

clinics, and other special clinics) were excluded. To identify hospitalisations

with COVID-19, we used the following International Statistical Classification

of Diseases and Related Health Problems, German Modification (ICD-10-GM) discharge

codes at any position: U07.1 and U07.2. Details on all ICD-10-GM codes and

Swiss operation classification (CHOP) codes used for the analysis are summarised

in Table S1-S3 in the appendix. Comorbidities were measured using the

Elixhauser Comorbidity Index [14], and frailty was measured using the Hospital

Frailty Score [15].

Outcomes

The

primary outcome was the IR of hospitalisation with COVID-19 per 10,000

person-years (PY) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) during the

first and second waves across the age spectrum. Secondary outcomes comprised of

the occurrence of the following in-hospital outcomes during the first and second

wave: all-cause in-hospital mortality, acute respiratory distress syndrome

(ARDS), length of hospital stay (LOS), intensive care unit (ICU) admission,

length of ICU stay, mechanical ventilation, duration of mechanical ventilation,

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and 30-day all-cause hospital

readmission. Hospitalisation with COVID-19 and ARDS was defined using ICD-10-GM

codes, and the need for ECMO was defined using CHOP codes (table S1-S3 in the appendix).

The remaining outcomes were applicable in the dataset provided by the FSO. Analyses

of hospital outcomes were stratified by different age groups (0–9, 10–19, 20–49,

50–69, and ≥70 years).Out-of-hospital mortality data was not

available in the dataset and could not be linked to the national death

registry.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistic was calculated for

patient demographics, including age, sex, nationality, and insurance status.

All baseline characteristics are expressed as mean (standard deviation [SD]),

median (interquartile range [IQR]), or frequency (%). Graphical illustration of

hospitalisation IR over age spectrum was performed using locally estimated

scatterplot smoothing (LOESS). Stratified by waves (first wave: January to May,

second wave: June to December), we estimated IR per 10,000 PY with 95% CI, rate

differences (RD), and incidence rate ratios (IRR). IR was calculated, allowing

multiple hospitalisations for a single person (more than 95% of the patients

were hospitalised only once) [16]. These estimates were calculated as the

number of individuals with a COVID-19 hospitalisation divided by the sum of “person-time”

population at risk in Switzerland, represented by the population size

multiplied by the 5-month follow-up during the first wave and by the 7-month

follow-up, according to age. To assess the IR of hospitalisation among the

overall Swiss population, the denominator was the standard population in 2020

during the first or second waves, respectively. We used the number of people living in

Switzerland at the end of 2020 as a surrogate. This information is publicly

available and published by the FSO [17]. We aggregated COVID-19 hospitalisations

per year of patient age. In detail, we counted the number of COVID-19 hospitalisations

for each patient age stratum paired with the published number of persons during

the respective wave in Switzerland. Thus, we assumed 5/12 of one person-year for every resident during the first wave and 7/12 of one person-year for every resident during

the second wave, ignoring people dying or moving in and out of the country. IR of hospitalisation among those who had a proven SARS-CoV-2 infection

were calculated using the overall positively tested population in the

denominator. These analyses were performed within the above-mentioned age

groups, and the first wave was denoted as a reference.

To explore differences in binary hospital

outcomes between the waves and by age groups, we estimated adjusted odds ratios

(aOR) and corresponding 95% CIs using a multivariable logistic regression

model. For continuous right-skewed outcomes, we assessed changes in percentage

and corresponding 95% CIs using a multiple linear generalised log-gamma

regression model. All models were adjusted for age, sex and Elixhauser

comorbidity index. The selection of covariates was based on the research

question at hand and on knowledge such as what was important to guide hospitalisation

criteria during the waves in Switzerland.

We evaluated for heterogeneity in OR

estimates across age groups using the Wald test for homogeneity. We performed a

risk factor analysis for mortality using univariable and multivariable analyses.

All p-values are two-sided and have not been adjusted for multiple testing.

Results were considered statistically significant at p <0.05. Statistical

analyses were performed with STATA 15.1 (STATA Corp., College Station, TX,

USA).

Results

Characteristics of the cohort

From January 1st to December 31st

2020, we identified 36,517

hospitalisations with COVID-19, 8862 (24.3%) during

the first and 27,655 (75.7%) during the second wave. Baseline characteristics

of the eligible study population stratified by age groups are shown in table 1.

Baseline characteristics stratified by waves are summarised in table S4 in the appendix.

Overall, the median age was 72 years (IQR, 58 to 82), 57.3% were male, 74.8% were

Swiss residents, and 13.8% had supplementary health care insurance. The

majority of hospitalisations was observed in patients aged older than 45 years.

Among those, we observed an overall high burden of comorbidities, with similar

distribution during the first and second waves.

Table 1Baseline characteristics stratified by age

groups.

| |

<10 years

|

10–19 years

|

20–49 years

|

50–69 years

|

≥70 years

|

| Hospitalisations, n |

297 |

275 |

4,338 |

11,278 |

20,329 |

| Wave, n (%)

|

First wave |

73 (24.6) |

72 (26.2) |

1333 (30.7) |

2974 (26.4) |

4410 (21.7) |

| Second wave |

224 (75.4) |

203 (73.8) |

3005 (69.3) |

8304 (73.6) |

15,919 (78.3) |

| Demographics |

Age, median (IQR)

[years] |

0 (0, 2) |

16 (14, 18) |

40 (32, 46) |

61 (56, 65) |

80 (75, 86) |

| Male sex, n (%) |

161 (54.2) |

133 (48.4) |

2321 (53.5) |

7244 (64.2) |

11,052 (54.4) |

| Swiss nationality,

n (%) |

181 (60.9) |

178 (64.7) |

2277 (52.5) |

7622 (67.6) |

17,058 (83.9) |

| Supplementary

insurance, n (%) |

20 (6.7) |

32 (11.6) |

308 (7.1) |

1248 (11.1) |

3432 (16.9) |

| Admission data |

Emergency

admission, n (%) |

215 (72.4) |

221 (80.4) |

3692 (85.1) |

9831 (87.2) |

16,576 (81.5) |

| Admission from

home, n (%) |

277 (93.3) |

246 (89.5) |

3857 (88.9) |

9617 (85.3) |

14,675 (72.2) |

| Admission to tertiary

care hospital: university hospital, n (%) |

116 (39.1) |

122 (44.4) |

1472 (33.9) |

2803 (24.9) |

4507 (22.2) |

| Admission to tertiary

care hospital: non-university hospital, n (%) |

168 (56.6) |

119 (43.3) |

2190 (50.5) |

6338 (56.2) |

11,657 (57.3) |

| Admission to secondary

care hospital, n (%) |

13 (4.4) |

34 (12.4) |

676 (15.6) |

2137 (18.9) |

4165 (20.5) |

| Comorbidities, n

(%) |

Hypertension |

2 (0.7) |

4 (1.5) |

444 (10.2) |

4596 (40.8) |

12,481 (61.4) |

| Dyslipidemia |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

128 (3.0) |

1731 (15.3) |

4119 (20.3) |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30.0

kg/m2) |

2 (0.7) |

6 (2.2) |

197 (4.5) |

612 (5.4) |

559 (2.7) |

| Coronary artery

disease |

2 (0.7) |

1 (0.4) |

63 (1.5) |

1220 (10.8) |

4336 (21.3) |

| Atrial fibrillation |

0 (0.0) |

1 (0.4) |

31 (0.7) |

820 (7.3) |

5269 (25.9) |

| Congestive heart

failure |

6 (2.0) |

9 (3.3) |

64 (1.5) |

476 (4.2) |

3094 (15.2) |

| Peripheral arterial

disease |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

5 (0.1) |

181 (1.6) |

1012 (5.0) |

| Cerebrovascular

disease |

1 (0.3) |

2 (0.7) |

43 (1.0) |

357 (3.2) |

1233 (6.1) |

| Chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

17 (0.4) |

582 (5.2) |

1889 (9.3) |

| Bronchial asthma |

9 (3.0) |

12 (4.4) |

247 (5.7) |

557 (4.9) |

618 (3.0) |

| Obstructive sleep

apnoea syndrome |

1 (0.3) |

1 (0.4) |

95 (2.2) |

669 (5.9) |

889 (4.4) |

| Chronic kidney disease

stage 3 & 4 |

0 (0.0) |

1 (0.4) |

36 (0.8) |

458 (4.1) |

4066 (20.0) |

| Chronic kidney disease

stage 5 & hemodialysis |

1 (0.3) |

1 (0.4) |

42 (1.0) |

294 (2.6) |

495 (2.4) |

| Solid organ

transplant recipient |

1 (0.3) |

4 (1.5) |

64 (1.5) |

199 (1.8) |

84 (0.4) |

| Solid tumour |

5 (1.7) |

3 (1.1) |

88 (2.0) |

560 (5.0) |

1296 (6.4) |

| Liver disease,

including cirrhosis |

2 (0.7) |

6 (2.2) |

202 (4.7) |

693 (6.1) |

660 (3.2) |

| Diabetes mellitus

type 2 |

0 (0.0) |

1 (0.4) |

231 (5.3) |

2584 (22.9) |

5172 (25.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus

type 1 |

1 (0.3) |

11 (4.0) |

27 (0.6) |

57 (0.5) |

45 (0.2) |

| Haematological

malignancy |

8 (2.7) |

7 (2.5) |

60 (1.4) |

216 (1.9) |

367 (1.8) |

| Rheumatoid

arthritis |

0 (0.0) |

1 (0.4) |

22 (0.5) |

131 (1.2) |

324 (1.6) |

| Human

immunodeficiency virus infection |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

31 (0.7) |

78 (0.7) |

32 (0.2) |

| Elixhauser

comorbidity index, median (IQR) |

0 (0, 1) |

0 (0, 1) |

1 (0, 2) |

2 (1, 3) |

3 (2, 4) |

| Hospital frailty score,

n (%) |

<5 points |

275 (92.6) |

249 (90.5) |

3870 (89.2) |

8390 (74.4) |

9647 (47.5) |

| 5–15 points |

21 (7.1) |

26 (9.5) |

445 (10.3) |

2642 (23.4) |

8987 (44.2) |

| >15 points |

1 (0.3) |

0 (0.0) |

23 (0.5) |

246 (2.2) |

1695 (8.3) |

| Outcomes |

In-hospital

mortality, n (%) |

2 (0.7) |

0 (0.0) |

39 (0.9) |

526 (4.7) |

3725 (18.3) |

| ICU admission, n

(%) |

23 (7.7) |

29 (10.5) |

479 (11.0) |

2012 (17.8) |

2080 (10.2) |

| ICU LOS, median

(IQR) [days] |

3.5 (1.7, 7.6) |

2.1 (0.8, 5.8) |

3.8 (1.5, 10.5) |

6.9 (2.5, 15.7) |

4.9 (1.6, 12.6) |

| Need for mechanical

ventilation, n (%) |

14 (4.7) |

11 (4.0) |

282 (6.5) |

1484 (13.2) |

1430 (7.0) |

| Duration of mechanical

ventilation, median (IQR) [days] |

2.2 (1.0, 7.5) |

2.0 (1.0, 6.3) |

7.0 (2.7, 12.3) |

8.7 (3.7, 16.0) |

6.7 (2.0, 14.3) |

| 30-days rehospitalisation,

n (%) |

17 (5.7) |

13 (4.7) |

203 (4.7) |

485 (4.3) |

1049 (5.2) |

Hospitalisation rates of patients with COVID-19

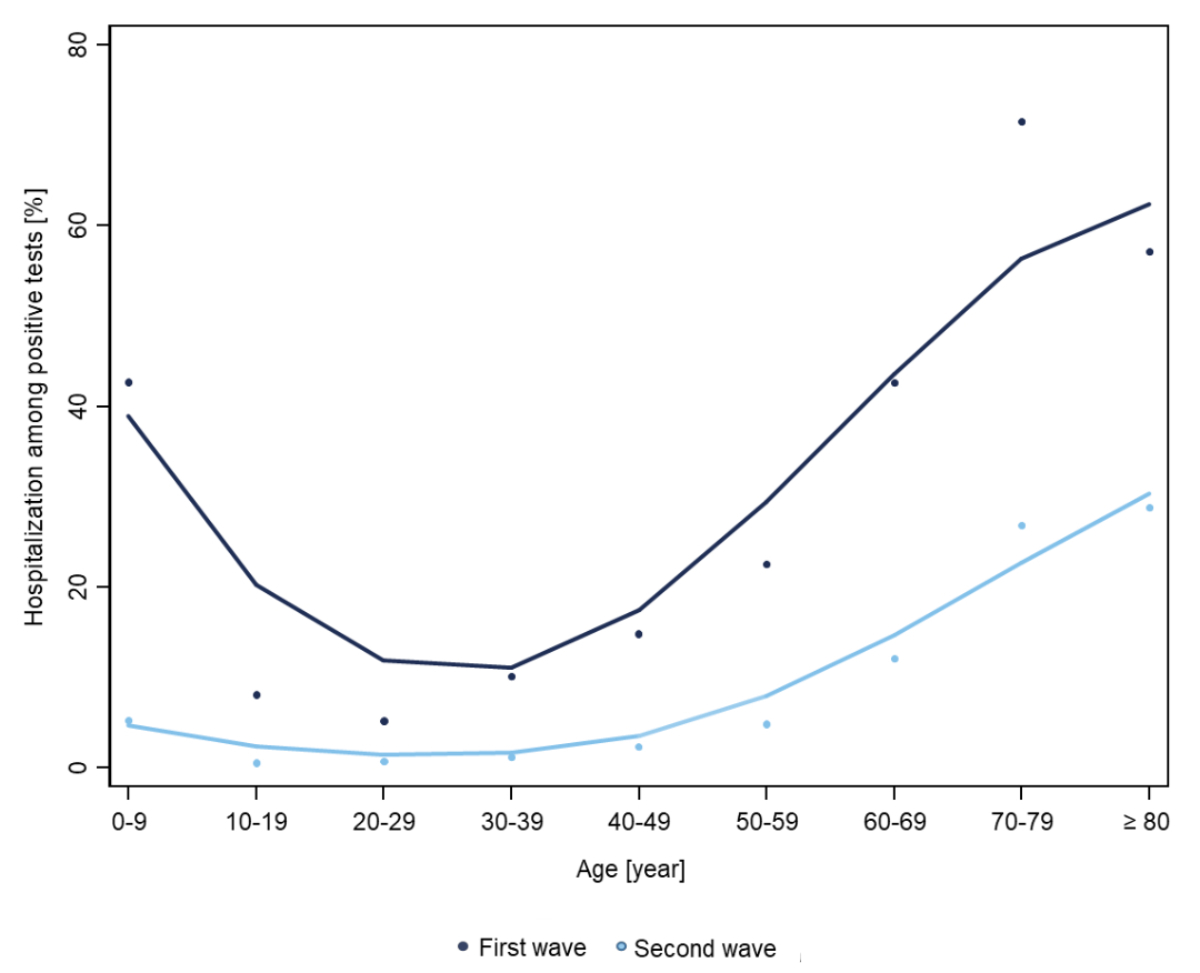

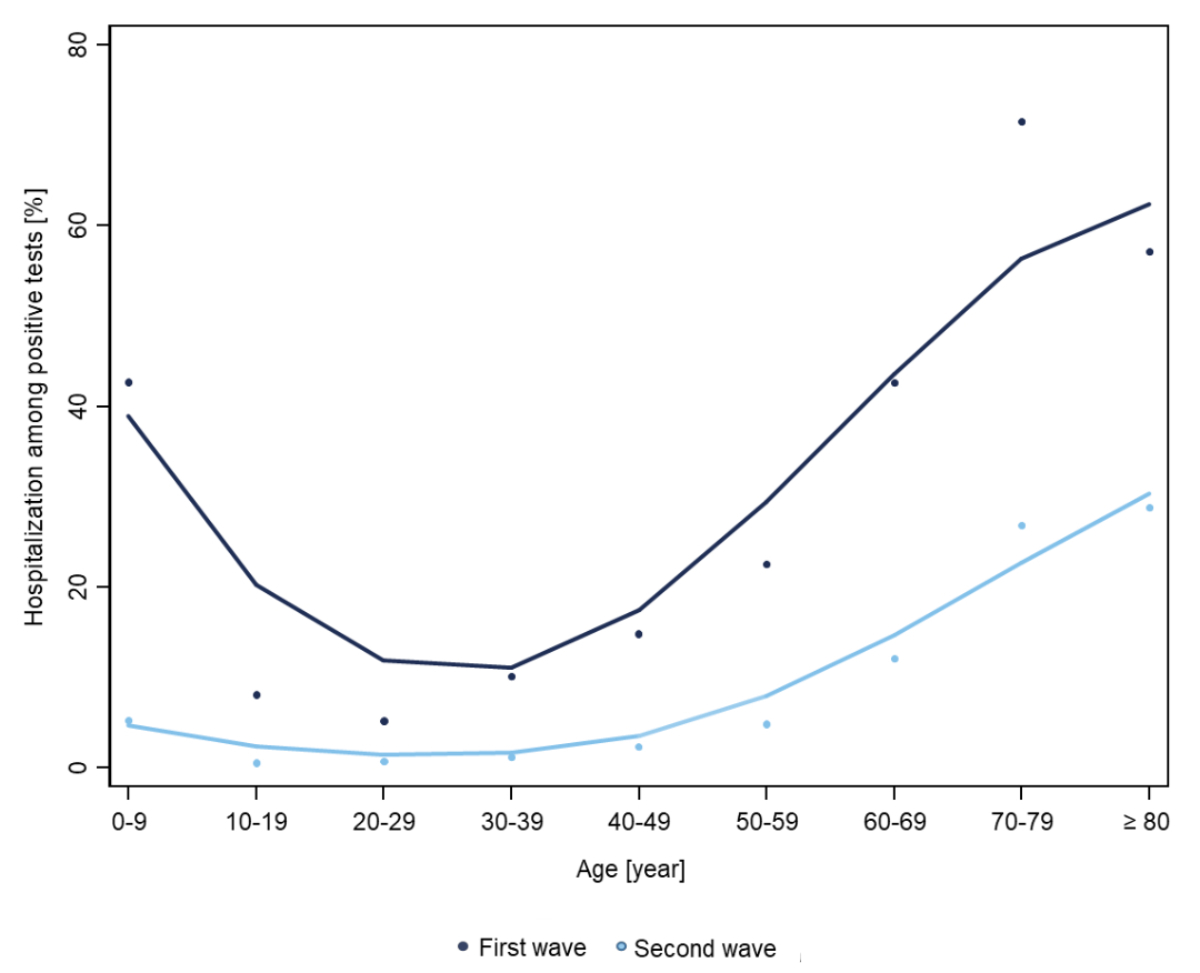

While IR of hospitalisations during the

first and second waves were generally low in children and adolescents, they

increased at around the age of 40 years, with a peak in older patients during

both waves (figure 1a).

Figure 1a Age-dependent

incidence rates for hospitalisations for COVID-19 among the overall Swiss population

per 10,000 person-years during the first wave (dark blue) and second wave

(light blue), using locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS).

Figure 1b Age-dependent

incidence rates for hospitalisations for COVID-19 among the overall SARS-CoV-2

positive tested population per 10,000 person-years during the first wave (dark

blue) and second wave (light blue), using locally estimated scatterplot

smoothing (LOESS).

Considering the overall standard population in the

denominator, IR were higher during the second wave compared with the first wave.

COVID-19 hospitalisation rates were highest in patients above 50 years (50–69

years: first wave: 31.49 per 10,000 person-years; second wave: 62.81 per 10,000 person-years; RD 31.32 [95% CI: 29.56 to 33.08] per 10,000 person-years;

≥70 years: first wave: 88.59 per 10,000 person-years; second wave: 228.41 per 10,000 person-years; RD 139.83 [95% CI: 135.42 to 144.23] per 10,000 person-years)

with a strong

predominance during the second wave (table 2).

Table 2Differences in

absolute and relative risk between the first and second COVID-19 waves across

age groups.

|

|

Age 0–9

years

|

Age 10–19

years

|

Age 20–49

years

|

Age 50–69

|

Age ≥70

|

p of

interaction

|

| First

wave |

Second

wave |

First

wave |

Second

wave |

First

wave |

Second

wave |

First

wave |

Second

wave |

First

wave |

Second

wave |

|

| Hospitalisations,

n |

73 |

224 |

72 |

203 |

1333 |

3005 |

2974 |

8304 |

4410 |

15,919 |

|

| Person-years |

365,335 |

511,468 |

353,958 |

495,541 |

1,451,184 |

2,031,657 |

944,334 |

1,322,068 |

497,815 |

696,941 |

|

| Incidence

rate per 10,000 PY |

1.99 |

4.38 |

2.03 |

4.10 |

9.19 |

14.79 |

31.49 |

62.81 |

88.59 |

228.41 |

|

| Incidence

rate difference (95% CI) |

Ref. |

2.38 (1.65

to 3.12) |

Ref. |

2.06 (1.32

to 2.80) |

Ref. |

5.61 (4.88

to 6.33) |

Ref. |

31.32 (29.56

to 33.08) |

Ref. |

139.83 (135.42

to 144.23) |

p <0.001 |

| Incidence

rate ratio (95% CI) |

Ref. |

2.19 (1.65

to 3.12) |

Ref. |

2.01 (1.53

to 2.67) |

Ref. |

1.61 (1.51

to 1.72) |

Ref. |

1.99 (1.91

to 2.08) |

Ref. |

2.58 (2.49

to 2.67) |

p <0.001 |

Illustration of hospitalisation IR

across the age spectrum among those who were tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 showed

different patterns for the first and second wave, with a first peak of

hospitalisations among children aged 0 to 9 year and a second peak with a

continuous increase of hospitalisations among adults beyond age 50 (figure 1b).

While rates of hospitalisation among the overall Swiss population were higher

during the second wave (figure 1a), the proportion of hospitalised people among

positively tested individuals was higher during the first wave (figure 1b).

In-hospital outcomes between the first

and second wave

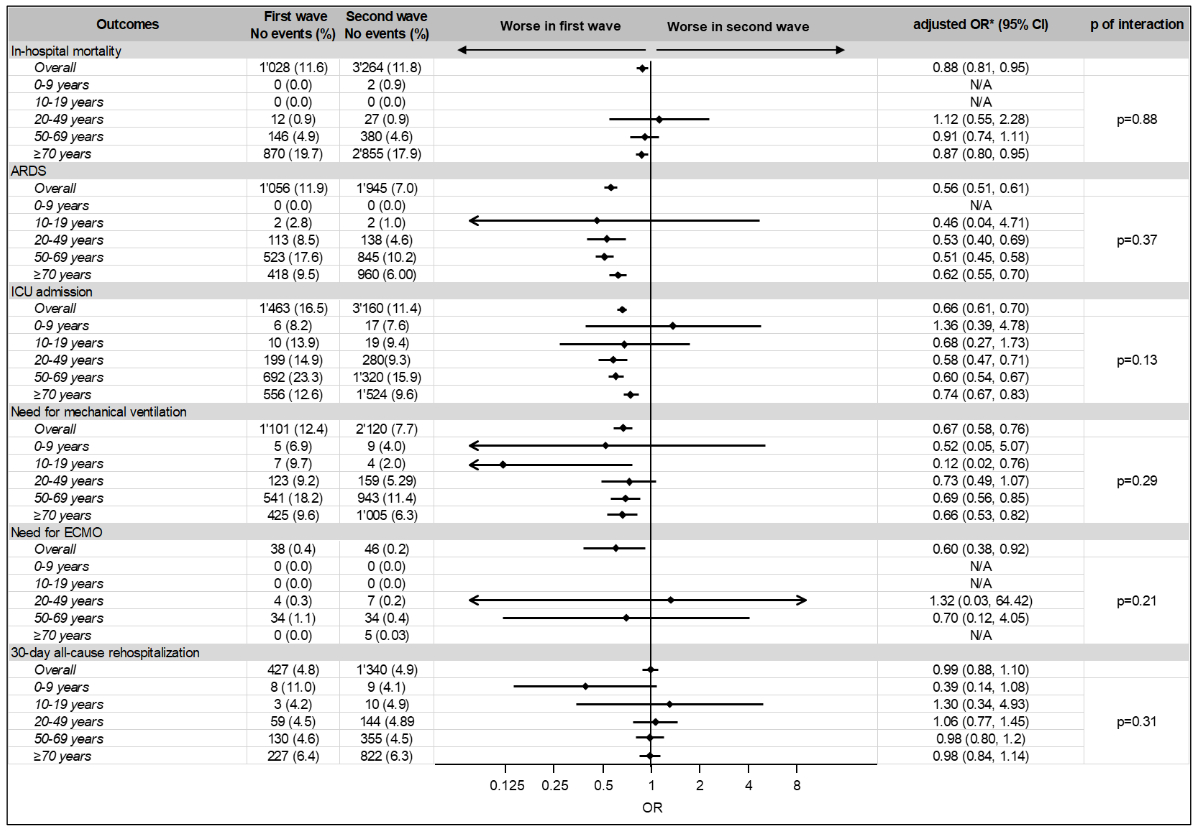

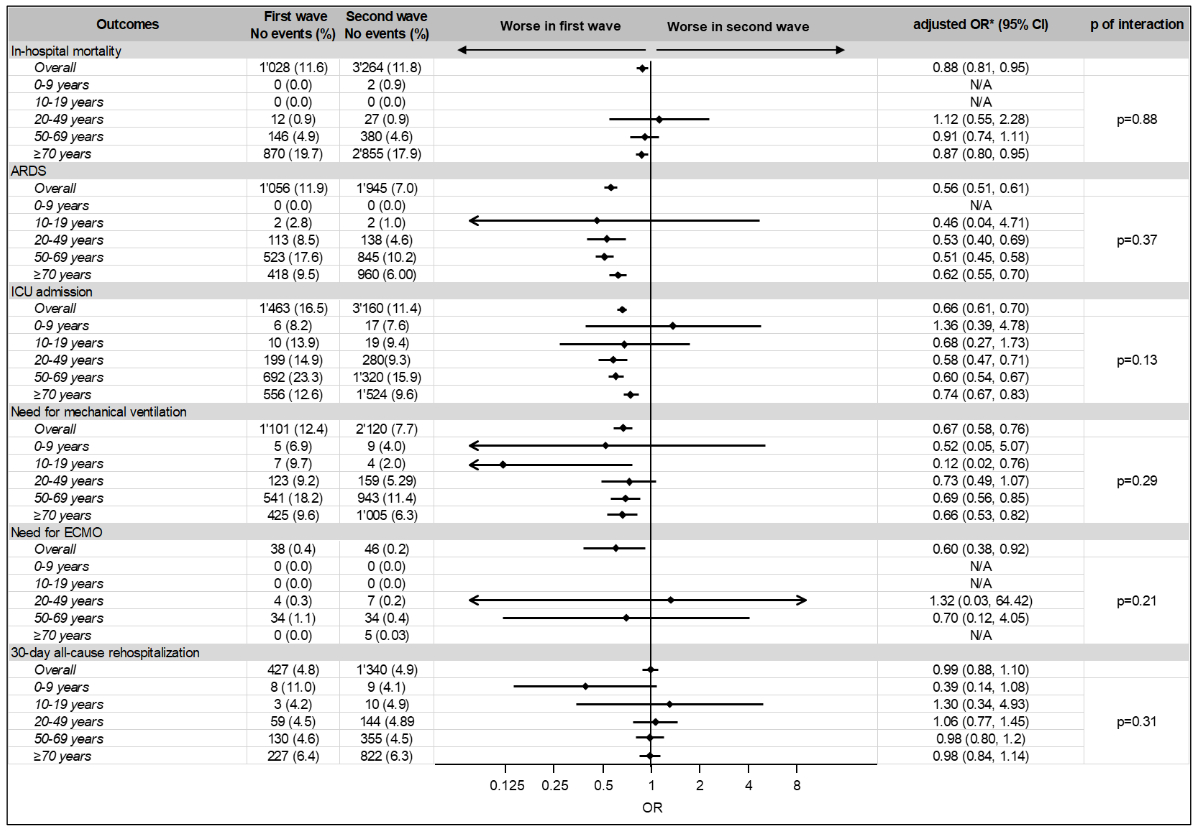

Among the overall population, 1028 (11.6%)

died in hospital during the first wave and 3264 (11.8%) during the second wave,

corresponding to lower odds of in-hospital mortality during the second wave

(aOR 0.88 [95% CI: 0.81 to 0.95]). Similarly, compared with the first wave, we

observed lower numbers of patients with ARDS (1056 [11.9%] vs. 1945 [7.0%], aOR

0.56 [95% CI: 0.51 to 0.61]), ICU admission (1463 [16.5%] vs. 3160 [11.4%], aOR

0.66 [95% CI: 0.61 to 0.70]), in need for mechanical ventilation (1101 [12.4%]

vs. 2120 [7.7%], aOR 0.67 [95% CI: 0.58 to 0.78]), and in need for ECMO (38 [0.4%]

vs. 46 [0.2%], aOR 0.60 [95% CI: 0.38 to 0.92]) during the second wave. The odds

for 30-day all-cause hospital readmission remained similar during the first and

second wave (427 [4.8%] vs. 1340 [4.9%], aOR of 0.99 [95% CI: 0.88 to 1.10])

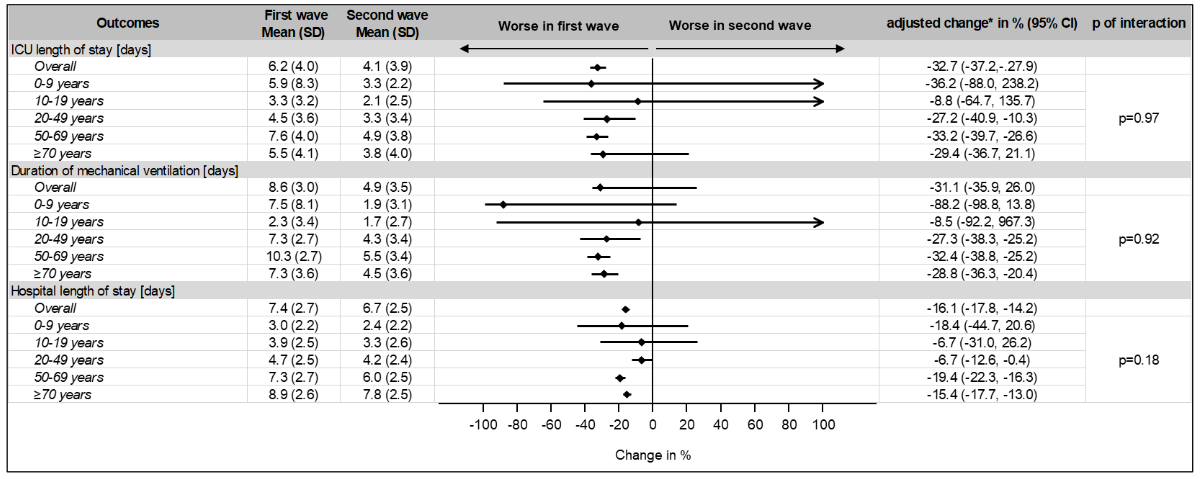

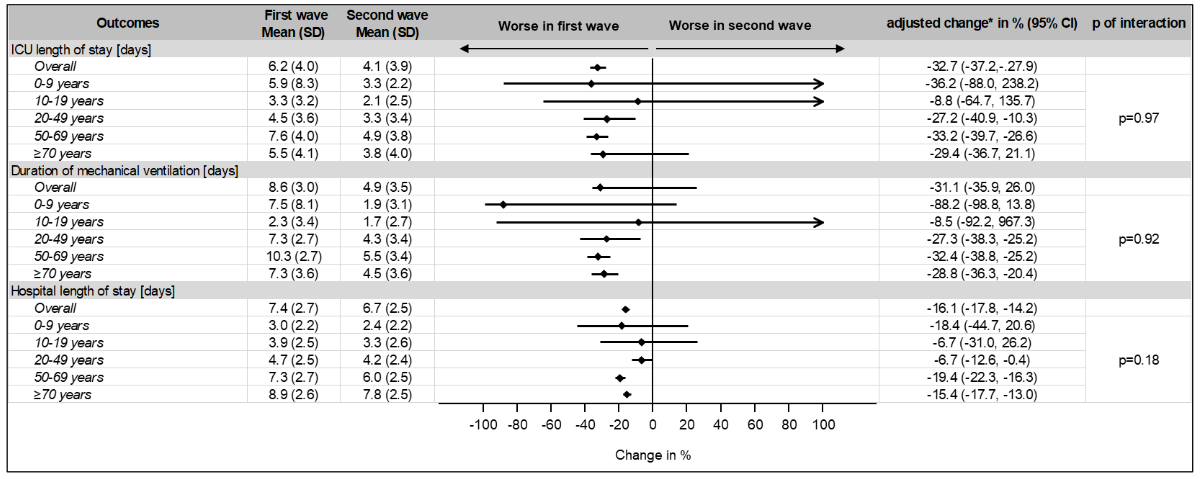

(figure 2). Compared with the first wave, LOS (7.4 [SD 2.7] vs. 6.7 [SD 2.5]) and

ICU LOS (6.2 [SD 4.0] vs. 4.1 [SD 3.9]) were shorter during the second wave with

a reduction of –16.1% (95% CI: –17.8 to –14.2) and –32.7% (95% CI: –37.2 to –27.9),

respectively (figure 3). There was no evidence for effect modification by age

for all hospital outcomes of interest (p of interaction >0.05).

Figure 2 Odds ratios and 95%

confidence intervals for adverse outcomes in prespecified age subgroups. First wave was chosen as a reference. There was no

evidence for effect modification by age for all hospital outcomes of interest

(p of interaction >0.05).

* adjusted for age, sex and Elixhauser comorbidity Index

ARDS: acute respiratory distress

syndrome; CI: confidence interval; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation;

ICU: intensive care unit; N/A: not applicable; no: number; OR: odds ratio

Figure 3 Changes in frequency

for adverse outcomes in prespecified age subgroups.

First wave was chosen as a reference. There was no

evidence for effect modification by age for all hospital outcomes of interest

(p of interaction >0.05).

* adjusted for age, sex and Elixhauser comorbidity Index

CI: confidence interval; ICU: intensive

care unit; SD: standard deviation

Predictors for mortality

Table 3 and 4 show baseline risk factors for in-hospital mortality during

the first and second waves. Among the adjusted regression analysis, the main

risk factors were the prevalence of chronic kidney disease stage 5 and/or

hemodialysis (first wave: aOR 3.26 [95% CI: 2.47 to 4.31), p <0.001];

second wave: aOR 4.02 [95% CI: 3.31 to 4.89], p <0.001) and haematological

malignancy (first wave: aOR 3.03 [95% CI: 1.97 to 4.66)], p <0.001; second

wave: aOR 2.39 [95% CI: 1.92 to 2.98], p <0.001).

Table 3Risk factor

analysis for in-hospital mortality during the first pandemic wave.

|

Factor

|

Survivors

(n = 7,834)

|

Non-survivors

(n = 1,028)

|

Unadjusted

OR (95% CI), p-value

|

Adjusted

OR* (95% CI), p-value

|

| Demographics |

Age,

median (IQR) [years] |

67

(54,78) |

81

(73,86) |

1.07

(1.06, 1.08), p <0.001

|

1.07 (1.06, 1.08), p

<0.001

|

| Male

sex, n (%) |

4493

(57.4) |

700

(68.1) |

1.59

(1.38, 1.82), p <0.001

|

1.96 (1.69, 2.28), p

<0.001

|

| Swiss

nationality, n (%) |

5750

(73.4) |

836

(81.3) |

1.58

(1.34, 1.86), p <0.001

|

0.97 (0.81, 1.16),

p = 0.728 |

| Supplementary

insurance, n (%) |

952

(12.2) |

109

(10.6) |

0.86

(0.70, 1.06), p = 0.151 |

0.74 (0.60, 0.93), p

= 0.008

|

| Admission

data |

Emergency

admission, n (%) |

6410

(81.8) |

883

(85.9) |

1.35

(1.12, 1.63), p = 0.001

|

1.68 (1.38, 2.04), p

<0.001

|

| Admission

from home, n (%) |

5988

(76.4) |

724

(70.4) |

0.73

(0.64, 0.85), p <0.001

|

1.16 (1.00, 1.36),

p = 0.054 |

| Admission

to tertiary care hospital: University

hospital, n (%) |

2520

(32.2) |

287

(27.9) |

0.82

(0.71, 0.94), p = 0.006

|

0.84 (0.72, 0.98), p

= 0.027

|

| Admission

to tertiary care hospital: Non-university

hospital, n (%) |

3789

(48.5) |

562

(54.7) |

1.28

(1.12, 1.46), p <0.001

|

1.29 (1.12, 1.48), p

<0.001

|

| Admission

to secondary care hospital, n (%) |

1516

(19.4) |

179

(17.4) |

0.88

(0.74, 1.04), p = 0.137 |

0.84 (0.70, 1.00),

p = 0.055 |

| Comorbidities,

n (%) |

Hypertension,

n (%) |

3437

(43.9) |

579

(56.3) |

1.65

(1.45, 1.88), p <0.001

|

0.67 (0.57, 0.78), p

<0.001

|

| Dyslipidemia,

n (%) |

1256

(16.0) |

178

(17.3) |

1.10

(0.92, 1.30), p = 0.294 |

0.74 (0.61, 0.88), p

= 0.001

|

| Obesity

(BMI ≥30.0 kg/m2), n (%) |

241

(3.1) |

34

(3.3) |

1.08

(0.75, 1.55), p = 0.688 |

1.39 (0.94, 2.07),

p = 0.100 |

| Coronary

artery disease, n (%) |

971

(12.4) |

253

(24.6) |

2.31

(1.97, 2.70), p <0.001

|

1.21 (1.02, 1.43), p

= 0.030

|

| Atrial

fibrillation, n (%) |

1043

(13.3) |

296

(28.8) |

2.63

(2.27, 3.06), p <0.001

|

1.15 (0.97, 1.37),

p = 0.104 |

| Congestive

heart failure, n (%) |

604

(7.7) |

223

(21.7) |

3.32

(2.80, 3.93), p <0.001

|

1.47 (1.21, 1.80), p

<0.001

|

| Peripheral

arterial disease, n (%) |

210

(2.7) |

56

(5.4) |

2.09

(1.55, 2.83), p <0.001

|

0.89 (0.64, 1.23),

p = 0.488 |

| Cerebrovascular

disease, n (%) |

305

(3.9) |

81

(7.9) |

2.11

(1.64, 2.72), p <0.001

|

1.35 (1.03, 1.77), p

= 0.029

|

| Chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) |

467

(6.0) |

114

(11.1) |

1.97

(1.59, 2.44), p <0.001

|

1.20 (0.95, 1.51),

p = 0.132 |

| Bronchial

asthma, n (%) |

379

(4.8) |

19

(1.8) |

0.37

(0.23, 0.59), p <0.001

|

0.52 (0.32, 0.85), p

= 0.008

|

| Obstructive

sleep apnoea syndrome, n (%) |

361

(4.6) |

68

(6.6) |

1.47

(1.12, 1.92), p = 0.005

|

1.37 (1.03, 1.83), p

= 0.029

|

| Chronic

kidney disease stage 3 & 4, n (%) |

649

(8.3) |

196

(19.1) |

2.61

(2.19, 3.11), p <0.001

|

1.02 (0.84, 1.24),

p = 0.851 |

| Chronic

kidney disease stage 5 & hemodialysis, n (%) |

212

(2.7) |

93

(9.0) |

3.58

(2.78, 4.61), p <0.001

|

3.26 (2.47, 4.31), p

<0.001

|

| Solid

organ transplant recipients, n (%) |

65

(0.8) |

8 (0.8) |

0.94

(0.45, 1.96), p = 0.864 |

1.42 (0.65, 3.13),

p = 0.389 |

| Solid

tumor, n (%) |

328

(4.2) |

97

(9.4) |

2.38

(1.88, 3.02), p <0.001

|

1.87 (1.44, 2.42), p

<0.001

|

| Liver

disease including cirrhosis, n (%) |

427

(5.5) |

85

(8.3) |

1.56

(1.23, 1.99), p <0.001

|

1.86 (1.43, 2.42), p

<0.001

|

| Diabetes

mellitus type 2, n (%) |

1447

(18.5) |

265

(25.8) |

1.53

(1.32, 1.78), p <0.001

|

0.97 (0.82, 1.15),

p = 0.758 |

| Diabetes

mellitus type 1, n (%) |

27

(0.3) |

4 (0.4) |

1.13

(0.39, 3.23), p = 0.821 |

1.75 (0.56, 5.44),

p = 0.335 |

| Haematological

malignancy, n (%) |

98

(1.3) |

34

(3.3) |

2.70

(1.82, 4.01), p <0.001

|

3.03 (1.97, 4.66), p

<0.001

|

| Rheumatoid

arthritis, n (%) |

81

(1.0) |

16

(1.6) |

1.51

(0.88, 2.60), p = 0.133 |

1.45 (0.82, 2.56),

p = 0.203 |

| Human

immunodeficiency virus infection, n (%) |

37

(0.5) |

2 (0.2) |

0.41

(0.10, 1.71), p = 0.221 |

0.67 (0.16, 2.91),

p = 0.597 |

| Elixhauser

comorbidity index, median (IQR) |

2 (1,

4) |

3 (2,

5) |

1.27

(1.24, 1.31), p <0.001

|

1.13 (1.10, 1.17), p

<0.001

|

| Hospital

frailty score |

<5 points, n (%) |

5061

(64.6) |

449

(43.7) |

0.42

(0.37, 0.48), p <0.001

|

0.92 (0.79, 1.08),

p = 0.304 |

| 5–15 points,

n (%) |

2377

(30.3) |

507

(49.3) |

2.23

(1.96, 2.55), p <0.001

|

1.22 (1.06, 1.41),

p = 0.006

|

| >15

points, n (%) |

396

(5.1) |

72

(7.0) |

1.41

(1.09, 1.83), p = 0.009

|

0.64 (0.49, 0.85), p

= 0.002

|

Table 4Risk factor

analysis for in-hospital mortality during the second pandemic wave.

|

Factor

|

Survivors

(n = 24,391)

|

Non-Survivors

(n = 3,264)

|

unadjusted

OR (95% CI),

p-value

|

adjusted

OR* (95% CI), p-value

|

| Demographics |

Age,

median (IQR) [years] |

71

(58,81) |

82 (75,

87) |

1.07

(1.06, 1.07), p <0.001

|

1.07 (1.06, 1.07), p

<0.001

|

| Male

sex, n (%) |

13,595

(55.7) |

2123

(65.0) |

1.48

(1.37, 1.59), p <0.001

|

1.79 (1.65, 1.94), p

<0.001

|

| Swiss

nationality, n (%) |

18,069

(74.1) |

2661

(81.5) |

1.54

(1.41, 1.69), p <0.001

|

0.94 (0.85, 1.04),

p = 0.238 |

| Supplementary

insurance, n (%) |

3448

(14.1) |

531

(16.3) |

1.18

(1.07, 1.30), p = 0.001

|

0.94 (0.85, 1.05),

p = 0.310 |

| Admission

data |

Emergency

admission, n (%) |

20,420

(83.7) |

2822

(86.5) |

1.24

(1.12, 1.38), p <0.001

|

1.48 (1.33, 1.66), p

<0.001

|

| Admission

from home, n (%) |

19,609

(80.4) |

2351

(72.0) |

0.63

(0.58, 0.68), p <0.001

|

0.91 (0.83, 0.99),

p = 0.031

|

| Admission

to tertiary care hospital |

|

|

|

|

| University

hospital, n (%) |

5555

(22.8) |

658

(20.2) |

0.86

(0.78, 0.94), p = 0.001

|

0.92 (0.84, 1.01),

p = 0.093 |

| Non-university

hospital, n (%) |

14,087

(57.8) |

2025

(62.0) |

1.20

(1.11, 1.29), p <0.001

|

1.16 (1.07, 1.25), p

<0.001

|

| Admission

to secondary care hospital, n (%) |

4749

(19.5) |

581

(17.8) |

0.90

(0.81, 0.99), p = 0.023

|

0.87 (0.79, 0.96), p

= 0.006

|

| Comorbidities,

n (%) |

Hypertension,

n (%) |

11,700

(48.0) |

1811 (55.5) |

1.35

(1.26, 1.46), p <0.001

|

0.58 (0.53, 0.63), p

<0.001

|

| Dyslipidemia,

n (%) |

4008

(16.4) |

536

(16.4) |

1.00

(0.91, 1.10), p = 0.998 |

0.69 (0.62, 0.76), p

<0.001

|

| Obesity

(BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2), n (%) |

968

(4.0) |

133

(4.1) |

1.03

(0.85, 1.24), p = 0.771 |

1.08 (0.89, 1.33),

p = 0.430 |

| Coronary

artery disease, n (%) |

3563

(14.6) |

835

(25.6) |

2.01

(1.84, 2.19), p <0.001

|

1.13 (1.03, 1.25), p

= 0.008

|

| Atrial

fibrillation, n (%) |

3703

(15.2) |

1079

(33.1) |

2.76

(2.54, 3.00), p <0.001

|

1.27 (1.16, 1.39), p

<0.001

|

| Congestive

heart failure, n (%) |

2050

(8.4) |

772

(23.7) |

3.38

(3.08, 3.70), p <0.001

|

1.63 (1.46, 1.81), p

<0.001

|

| Peripheral

arterial disease, n (%) |

752

(3.1) |

180

(5.5) |

1.83

(1.55, 2.17), p <0.001

|

0.90 (0.75, 1.07),

p = 0.224 |

| Cerebrovascular

disease, n (%) |

1015

(4.2) |

235

(7.2) |

1.79

(1.54, 2.07), p <0.001

|

1.11 (0.95, 1.30),

p = 0.184 |

| Chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) |

1528

(6.3) |

379

(11.6) |

1.97

(1.74, 2.21), p <0.001

|

1.26 (1.11, 1.43), p

<0.001

|

| Bronchial

asthma, n (%) |

962

(3.9) |

83

(2.5) |

0.64

(0.51, 0.80), p <0.001

|

0.67 (0.53, 0.85), p

= 0.001

|

| Obstructive

sleep apnoea syndrome, n (%) |

1068

(4.4) |

158

(4.8) |

1.11

(0.94, 1.32), p = 0.229 |

0.98 (0.82, 1.18),

p = 0.870 |

| Chronic

kidney disease stage 3 & 4, n (%) |

2891

(11.9) |

825

(25.3) |

2.52

(2.30, 2.75), p <0.001

|

1.07 (0.97, 1.18),

p = 0.201 |

| Chronic

kidney disease stage 5 & hemodialysis, n (%) |

328

(1.3) |

200

(6.1) |

4.79

(4.00, 5.73), p <0.001

|

4.02 (3.31, 4.89), p

<0.001

|

| Solid

organ transplant recipients, n (%) |

252

(1.0) |

27

(0.8) |

0.80

(0.54, 1.19), p = 0.270 |

1.21 (0.80, 1.84),

p = 0.368 |

| Solid

tumor, n (%) |

1201

(4.9) |

326

(10.0) |

2.14

(1.88, 2.44), p <0.001

|

1.61 (1.40, 1.85), p

<0.001

|

| Liver

disease including cirrhosis, n (%) |

861

(3.5) |

190

(5.8) |

1.69

(1.44, 1.99), p <0.001

|

1.88 (1.57, 2.25), p

<0.001

|

| Diabetes

mellitus type 2, n (%) |

5366

(22.0) |

910

(27.9) |

1.37

(1.26, 1.49), p <0.001

|

0.95 (0.87, 1.05),

p = 0.321 |

| Diabetes

mellitus type 1, n (%) |

104

(0.4) |

6 (0.2) |

0.43

(0.19, 0.98), p = 0.045

|

0.61 (0.26, 1.43),

p = 0.253 |

| Haematological

malignancy, n (%) |

402

(1.6) |

124

(3.8) |

2.36

(1.92, 2.89), p <0.001

|

2.39 (1.92, 2.98), p

<0.001

|

| Rheumatoid

arthritis, n (%) |

324

(1.3) |

57

(1.7) |

1.32

(0.99, 1.75), p = 0.055 |

1.07 (0.80, 1.44),

p = 0.655 |

| Human immunodeficiency

virus infection, n (%) |

98

(0.4) |

4 (0.1) |

0.30

(0.11, 0.83), p = 0.020

|

0.56 (0.20, 1.56),

p = 0.271 |

| Elixhauser

comorbidity index, median (IQR) |

2 (1,

4) |

3 (2,

5) |

1.27

(1.25, 1.29), p <0.001

|

1.16 (1.14, 1.18), p

<0.001

|

| Hospital

frailty score

|

<5

points, n (%) |

15,645

(64.1) |

449

(43.7) |

0.36

(0.33, 0.39), p <0.001

|

0.70 (0.64, 0.76), p

<0.001

|

| 5–15

points, n (%) |

7551

(31.0) |

1686

(51.7) |

2.38

(2.21, 2.57), p <0.001

|

1.40 (1.29, 1.51),

p = 0.006

|

| >15

points, n (%) |

1195

(4.9) |

302

(9.3) |

1.98

(1.73, 2.26), p <0.001

|

0.97 (0.84, 1.12), p

= 0.678

|

Discussion

This nationwide cohort study of hospitalised

COVID-19 patients in Switzerland revealed several key findings: First, hospitalisation

rates in patients with COVID-19 were highest among adults older than 50 years

and more pronounced during the second wave. Second, while the hospitalisation rate was higher

among the overall Swiss population during the second wave, it was lower among

positively tested individuals during the same period. Third, except for readmission, the risk for hospital-associated adverse

outcomes was lower during the second wave, irrespective of patient age.

The highest hospitalisation rates among

the overall Swiss population were observed in patients aged 50 years and older,

both during the first and second wave. However, the peak of hospitalisations during

the second wave was much higher than the first wave. These results are

plausible since we observed significantly more infections during the second

wave, resulting in more hospitalisations. Although data must be interpreted

carefully, as hospitalisation and test criteria differed between the two waves,

we observed a lower proportion of hospitalised people among the overall

positively tested population during the second wave.

Improvement of patient management was a

further important key component which was achieved during the second wave. Overall,

the odds of adverse outcomes decreased during the second wave, except for hospital

readmission. The expected decrease of in-hospital adverse events during the

second wave is probably explained by the improved understanding of the treating

physicians and nursing staff about the management of COVID-19 patients [18]. Importantly,

the widespread administration of dexamethasone during the second wave may have contributed

to a stronger reduction in in-hospital mortality, as already shown by previous

studies [19]. Consistent with other studies [20–24], we observed a lower risk of

in-hospital mortality during the second wave (aOR 0.88 [95% CI: 0.81 to 0.95]).

While, as compared with findings from clinical trials, a relative risk

reduction of 12% may seem small, hospitalised patients during the second wave tended

to be older and more comorbid, both characteristics known to independently increase

the risk of COVID-19-related mortality [25–28].

Similarly, corticosteroids may also have

reduced the rate of progression to severe COVID-19 due to an attenuation of the

inflammation, resulting in lower rates of ARDS, admission to ICU, need for mechanical

ventilation and ECMO support as well as a 16% shorter LOS of 7.4 vs. 6.7 days [29].

In addition, the reduction in LOS during the second wave could also be due to improved

discharge processes and earlier transfer to rehabilitation facilities. This was

possible since many rehabilitation facilities were obligated to unburden acute

care hospitals by accepting still-infectious COVID-19 patients [30].

We did not observe a change in readmission

rates between the two waves. This can be explained by the fact that COVID-19 is

an acute disease and may not lead to readmissions per se, whereas the burden of comorbidities as a potential driver for

readmission tended to be higher during the second wave and may have diluted any

beneficial effect on hospital readmission. These data must be interpreted in

the context of the study design. As COVID-19 hospitalisations were identified

using ICD-10-GM codes used for billing purposes, thus, misclassification and

underreporting are possible, especially during the beginning of the pandemic when

no specific ICD-10 codes were available. In line, the

database provided by the FSO revealed larger numbers of hospitalisations as

compared with data from the CH-SUR database. Since algorithms based on the U07.1 code had high

sensitivity among hospitalised patients but at the expense of low specificity [31],

it is likely that the number of hospitalisation

with COVID-19 as provided by the FSO might be overestimated. However, it can

also not be excluded that some hospitalisations with COVID-19 in the FSO-database

were not lab-confirmed during the hospital stay but diagnosed based on an

out-of-hospital test or clinical features. Second,

unmeasurable confounding like smoking status, genetic susceptibility or home

medication must be considered, as the used dataset does not include any

information in this regard. Third, due to the study’s retrospective design, no

causal inference is possible. Fourth, we did not account for potential

within-patient/hospital clustering. However, we do not think that accounting for clustering

relevantly changes the conclusion of our manuscript, as the number of clusters

(hospitals, hospital admissions per patient) were comparable between the first

and second waves of the pandemic. Fifth, medical

treatments received during the hospitalisation for COVID-19 could not be analysed,

as this information is missing in the analysed dataset. However, there are

several strengths of note. This analysis was based on nationwide hospital care

data with high external validity, strong statistical power and high generalisability

across all regions in Switzerland. Moreover, this study provides insights into

different age groups that were not comprehensively addressed in earlier studies

in Switzerland.

Conclusion

In this nationwide cohort study, hospitalisation

rates of COVID-19 patients were highest among adults older than 50 years and

during the second wave. Except for readmission, the risk of hospital adverse

outcomes was decreased during the second wave, regardless of the patient`s age.

Data sharing statement

The data supporting this study’s findings

are available upon request from the Swiss Federal Statistical Office

(Neuchâtel, Switzerland). Restrictions apply to the availability of these data,

which were used under license for this study. Data are available as part of the

data on “Medizinische Statistik der Krankenhäuser” with the permission of the

Swiss Federal Statistical Office, Section Health Services and Population

Health.

Acknowledgement

We

thank the Swiss Federal Statistics Office (Neuchâtel, Switzerland) for the

acquisition and provision of data.

Claudia Gregoriano, PhD

Medical University Department of Medicine

Kantonsspital Aarau

Tellstrasse 25

CH-5001 Aarau

c.gregoriano[at]gmail.com

References

1.

Verelst F

,

Kuylen E

,

Beutels P

. Indications for healthcare surge capacity in European countries facing an exponential increase in coronavirus disease (COVID-19) cases, March 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020 Apr;25(13):2000323. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.13.2000323

2.

Winkelmann J

,

Webb E

,

Williams GA

,

Hernández-Quevedo C

,

Maier CB

,

Panteli D

. European countries’ responses in ensuring sufficient physical infrastructure and workforce capacity during the first COVID-19 wave. Health Policy. 2022 May;126(5):362–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.06.015

3.

Webb E

,

Hernández-Quevedo C

,

Williams G

,

Scarpetti G

,

Reed S

,

Panteli D

. Providing health services effectively during the first wave of COVID-19: A cross-country comparison on planning services, managing cases, and maintaining essential services. Health Policy. 2022 May;126(5):382–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.04.016

4.

Zimmermann BM

,

Fiske A

,

McLennan S

,

Sierawska A

,

Hangel N

,

Buyx A

. Motivations and Limits for COVID-19 Policy Compliance in Germany and Switzerland. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2021 Apr;11(8):1342–53. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2021.30

5.

Salathé M

,

Althaus CL

,

Neher R

,

Stringhini S

,

Hodcroft E

,

Fellay J

, et al.

COVID-19 epidemic in Switzerland: on the importance of testing, contact tracing and isolation. Swiss Med Wkly. 2020 Mar;150:w20225. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2020.20225

6.

Flaxman S

,

Mishra S

,

Gandy A

,

Unwin HJ

,

Mellan TA

,

Coupland H

, et al.; Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team

. Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature. 2020 Aug;584(7820):257–61. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2405-7

7.

Cao B

,

Wang Y

,

Wen D

,

Liu W

,

Wang J

,

Fan G

, et al.

A Trial of Lopinavir-Ritonavir in Adults Hospitalized with Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 May;382(19):1787–99. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001282

8.

Boulware DR

,

Pullen MF

,

Bangdiwala AS

,

Pastick KA

,

Lofgren SM

,

Okafor EC

, et al.

A Randomized Trial of Hydroxychloroquine as Postexposure Prophylaxis for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 Aug;383(6):517–25. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2016638

9.

Wang Y

,

Zhang D

,

Du G

,

Du R

,

Zhao J

,

Jin Y

, et al.

Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020 May;395(10236):1569–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9

10.

Horby P

,

Lim WS

,

Emberson JR

,

Mafham M

,

Bell JL

,

Linsell L

, et al.; RECOVERY Collaborative Group

. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb;384(8):693–704. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2021436

11.

Biswas M

,

Rahaman S

,

Biswas TK

,

Haque Z

,

Ibrahim B

. Association of Sex, Age, and Comorbidities with Mortality in COVID-19 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Intervirology. 2020 Dec;1–12.

12.

Bundesamt für Statistik

. Auswirkungen der Covid-19-Pandemie auf die Gesundheitsversorgung im Jahr 2020. 2021.

13.

von Elm E

,

Altman DG

,

Egger M

,

Pocock SJ

,

Gøtzsche PC

,

Vandenbroucke JP

; STROBE Initiative

. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007 Oct;335(7624):806–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD

14.

Elixhauser A

,

Steiner C

,

Harris DR

,

Coffey RM

. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998 Jan;36(1):8–27. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004

15.

Gilbert T

,

Neuburger J

,

Kraindler J

,

Keeble E

,

Smith P

,

Ariti C

, et al.

Development and validation of a Hospital Frailty Risk Score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: an observational study. Lancet. 2018 May;391(10132):1775–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30668-8

16.

Bundesamt für Gesundheit (BAG)

. Coronavirus: Monitoring [Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/krankheiten/ausbrueche-epidemien-pandemien/aktuelle-ausbrueche-epidemien/novel-cov/situation-schweiz-und-international/monitoring.html#19385953 ], last access: 23.12.2022.

17.

Bundesamt für Statistik

. Permanent resident population by age, sex and category of citizenship, 2010-2021 2010-2021 [Available from: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/bevoelkerung/stand-entwicklung/alter-zivilstand-staatsangehoerigkeit.assetdetail.23064709.html ], last access: 23.12.2022.

18.

World Health Organization (WHO)

. Clinical management of COVID-19: Living guideline, 23 June 2022 2022 [Available from: WHO-2019-nCoV-Clinical-2022.1-eng.pdf.], last access, 23.12.2022.

19.

van Paassen J

,

Vos JS

,

Hoekstra EM

,

Neumann KM

,

Boot PC

,

Arbous SM

. Corticosteroid use in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis on clinical outcomes. Crit Care. 2020 Dec;24(1):696. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03400-9

20.

Oladunjoye O

,

Gallagher M

,

Wasser T

,

Oladunjoye A

,

Paladugu S

,

Donato A

. Mortality due to COVID-19 infection: A comparison of first and second waves. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2021 Nov;11(6):747–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/20009666.2021.1978154

21.

Saito S

,

Asai Y

,

Matsunaga N

,

Hayakawa K

,

Terada M

,

Ohtsu H

, et al.

First and second COVID-19 waves in Japan: A comparison of disease severity and characteristics. J Infect. 2021 Apr;82(4):84–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.10.033

22.

Di Fusco M

,

Shea KM

,

Lin J

,

Nguyen JL

,

Angulo FJ

,

Benigno M

, et al.

Health outcomes and economic burden of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in the United States. J Med Econ. 2021;24(1):308–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2021.1886109

23.

Mallow PJ

,

Belk KW

,

Topmiller M

,

Hooker EA

. Outcomes of Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients by Risk Factors: Results from a United States Hospital Claims Database. J Health Econ Outcomes Res. 2020 Sep;7(2):165–74. https://doi.org/10.36469/jheor.2020.17331

24.

Iftimie S

,

López-Azcona AF

,

Vallverdú I

,

Hernández-Flix S

,

de Febrer G

,

Parra S

, et al.

First and second waves of coronavirus disease-19: A comparative study in hospitalized patients in Reus, Spain. PLoS One. 2021 Mar;16(3):e0248029. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248029

25.

Hothorn T

,

Bopp M

,

Günthard H

,

Keiser O

,

Roelens M

,

Weibull CE

, et al.

Assessing relative COVID-19 mortality: a Swiss population-based study. BMJ Open. 2021 Mar;11(3):e042387. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042387

26.

Williamson EJ

,

Walker AJ

,

Bhaskaran K

,

Bacon S

,

Bates C

,

Morton CE

, et al.

Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020 Aug;584(7821):430–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4

27.

Bravi F

,

Flacco ME

,

Carradori T

,

Volta CA

,

Cosenza G

,

De Togni A

, et al.

Predictors of severe or lethal COVID-19, including Angiotensin Converting Enzyme inhibitors and Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers, in a sample of infected Italian citizens. PLoS One. 2020 Jun;15(6):e0235248. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235248

28.

Maximiano Sousa F

,

Roelens M

,

Fricker B

,

Thiabaud A

,

Iten A

,

Cusini A

, et al.; Ch-Sur Study Group

. Risk factors for severe outcomes for COVID-19 patients hospitalised in Switzerland during the first pandemic wave, February to August 2020: prospective observational cohort study. Swiss Med Wkly. 2021 Jul;151(2930):w20547. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2021.20547

29.

Ye Z

,

Wang Y

,

Colunga-Lozano LE

,

Prasad M

,

Tangamornsuksan W

,

Rochwerg B

, et al.

Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids in COVID-19 based on evidence for COVID-19, other coronavirus infections, influenza, community-acquired pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2020 Jul;192(27):E756–67. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.200645

30.

Liebl ME

,

Gutenbrunner C

,

Glaesener JJ

,

Schwarzkopf S

,

Best N

,

Lichti G

, et al.

Early Rehabilitation in COVID-19 – Best Practice Recommendations for the Early Rehabilitation of COVID-19 Patients. Phys Med Rehabilmed Kurortmed. 2020 Jun;30(3):129–34. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1162-4919

31.

Brown CA

,

Londhe AA

,

He F

,

Cheng A

,

Ma J

,

Zhang J

, et al.

Development and Validation of Algorithms to Identify COVID-19 Patients Using a US Electronic Health Records Database: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin Epidemiol. 2022 May;14:699–709. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S355086

Appendix

Table S1ICD-10 codes for inclusion criteria.

|

Name

|

ICD-10 diagnosis code

|

Code position

|

| COVID-19, virus confirmed |

U071 |

Any |

| COVID-19, virus not confirmed |

U072 |

Any |

Table S2ICD-10 codes for baseline characteristics

(comorbidities) and outcomes.

|

Name of group

|

ICD-10 diagnosis code

|

Code position: comorbidities

|

| Hypertension |

I10–I13, I15, I674 |

Any |

| Dyslipidemia |

E78 |

Any |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2) |

E65–E66

|

Any |

| Coronary artery disease |

I20–I25 |

Any |

| Congestive heart failure |

I50, I110, I130, I132 |

Any |

| Peripheral arterial disease |

I702 |

Any |

| Cerebrovascular disease |

I60–I67, I69 |

Any |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

J44 |

Any |

| Bronchial asthma |

J45–J46 |

Any |

| Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome |

G473

|

Any |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome |

J80 |

Any |

| Chronic kidney disease stage 3 & 4 |

N183–N184 |

Any |

| Chronic kidney disease stage 5 &

hemodialysis |

N185, T824, T8571,Z491–Z492, Z992 |

Any |

| Solid organ transplant recipients |

T861–T864, T8681–T8682, T8688, T869, Z940–Z944,

Z9488, Z949

|

Any |

| Solid tumor |

C0–C7 |

Any |

| Liver disease including cirrhosis |

K7, K703, K717, K744, K746 K7470–K7472 |

Any |

| Diabetes mellitus type 1 |

E10

|

Any |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 |

E11 |

Any |

| Haematological malignancy |

C81–88, C90–C96) |

Any |

| Rheumatoid

arthritis |

M05–M06, M08 |

Any |

| Human immunodeficiency virus infection |

B20–B24, F024, O987, U60–U61, U85, Z21 |

Any |

Table S3CHOP codes baseline characteristics

(comorbidities) and outcomes.

|

Name

|

CHOP code

|

Code position

|

| Haemo- and peritoneal dialysis |

3895, 3927, 3942–3943, 39951–39954, 3995I1–3995I2, 5498 |

Any |

| Solid organ transplant |

0091*–0093*,335*–336*,

3751*,4194*,4697*,505*,528*,556* |

Any |

| Installation and revision of portosystemic

shunt |

391100, 391199 |

Any |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

37698*, 3769A*, 376A61*– 376A62*, 376A71*–376A73*,

376B61*– 376B62*, 376B71*–376B73*, 376C61*, 376C62*, 376C71*–376C73*, 376D*,

376D31*, 376D41* |

Any |

Table S4Baseline characteristics stratified by waves.

| |

First wave

|

Second wave

|

p-value

|

| Hospitalisations, n |

8862 |

27,655 |

|

| Demographics |

Age, median (IQR)

[years] |

69 (55, 80) |

73 (60, 82) |

<0.001 |

| Age groups, n (%) |

|

|

|

| <10 years |

73 (0.8) |

224 (0.8) |

<0.001 |

| 10–19 years |

72 (0.8) |

203 (0.7) |

|

| 20–49 years |

1333 (15.0) |

3005 (10.9) |

|

| 50–69 years |

2974 (33.6) |

8304 (30.0) |

|

| ≥70 years |

4410 (49.8) |

15,919 (57.6) |

|

| Male sex, n (%) |

5,193 (58.6) |

15,718 (56.8) |

0.004 |

| Swiss nationality,

n (%) |

6586 (74.3) |

20,730 (75.0) |

0.23 |

| Supplementary

insurance, n (%) |

1061 (12.0) |

3979 (14.4) |

<0.001 |

| Admission data |

Emergency

admission, n (%) |

7293 (82.3) |

23,242 (84.0) |

<0.001 |

| Admission from

home, n (%) |

6712 (75.7) |

21,960 (79.4) |

<0.001 |

| Admission to tertiary

care hospital, n (%) |

|

|

<0.001 |

| University hospital |

2807 (31.7) |

6213 (22.5) |

|

| Non-university

hospital |

4360 (49.2) |

16,112 (58.3) |

|

| Admission to secondary

care hospital, n (%) |

1695 (19.1) |

5330 (19.3) |

|

| Comorbidities, n

(%) |

Hypertension |

4016 (45.3) |

13,511 (48.9) |

<0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia |

1434 (16.2) |

4544 (16.4) |

0.58 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30.0

kg/m2) |

275 (3.1) |

1101 (4.0) |

<0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease |

1224 (13.8) |

4398 (15.9) |

<0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation |

1339 (15.1) |

4782 (17.3) |

<0.001 |

| Congestive heart

failure |

827 (9.3) |

2822 (10.2) |

0.017 |

| Peripheral arterial

disease |

266 (3.0) |

932 (3.4) |

0.090 |

| Cerebrovascular

disease |

386 (4.4) |

1250 (4.5) |

0.52 |

| Chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease |

581 (6.6) |

1907 (6.9) |

0.27 |

| Bronchial asthma |

398 (4.5) |

1,045 (3.8) |

0.003 |

| Obstructive sleep

apnea syndrome |

429 (4.8) |

1226 (4.4) |

0.11 |

| Chronic kidney

disease stage 3 & 4 |

845 (9.5) |

3716 (13.4) |

<0.001 |

| Chronic kidney

disease stage 5 & hemodialysis |

305 (3.4) |

528 (1.9) |

<0.001 |

| Solid organ

transplant recipients |

73 (0.8) |

279 (1.0) |

0.12 |

| Solid tumor |

425 (4.8) |

1527 (5.5) |

0.008 |

| Liver disease including

cirrhosis |

512 (5.8) |

1051 (3.8) |

<0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus

type 2 |

1712 (19.3) |

6276 (22.7) |

<0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus

type 1 |

31 (0.3) |

110 (0.4) |

0.53 |

| Haematological

malignancy |

132 (1.5) |

526 (1.9) |

0.011 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis |

97 (1.1) |

381 (1.4) |

0.041 |

| Human

immunodeficiency virus infection |

39 (0.4) |

102 (0.4) |

0.35 |

| Elixhauser

comorbidity index, median (IQR) |

2 (1, 4) |

2 (1, 4) |

<0.001 |

| Hospital frailty score,

n (%) |

<5 points |

5510 (62.2) |

16,921 (61.2) |

0.25 |

| 5–15 points |

2884 (32.5) |

9237 (33.4) |

|

| >15 points |

468 (5.3) |

1497 (5.4) |

|

| Outcomes |

In-hospital

mortality, n (%) |

1028 (11.6) |

3264 (11.8) |

0.61 |

| ICU admissions, n

(%) |

1463 (16.5) |

3160 (11.4) |

<0.001 |

| ICU LOS, median

(IQR) [days] |

8.3(2.1, 18.3) |

4.9 (1.8, 11.7) |

<0.001 |

| Need for mechanical

ventilation, n (%) |

1101 (12.4) |

2120 (7.7) |

<0.001 |

| Duration of mechanical

ventilation, median (IQR) [days] |

10.7 (5.0, 18.3) |

6.3 (2.0, 13.0) |

<0.001 |

| 30-days rehospitalisation,

n (%) |

427 (4.8) |

1340 (4.8) |

0.92 |