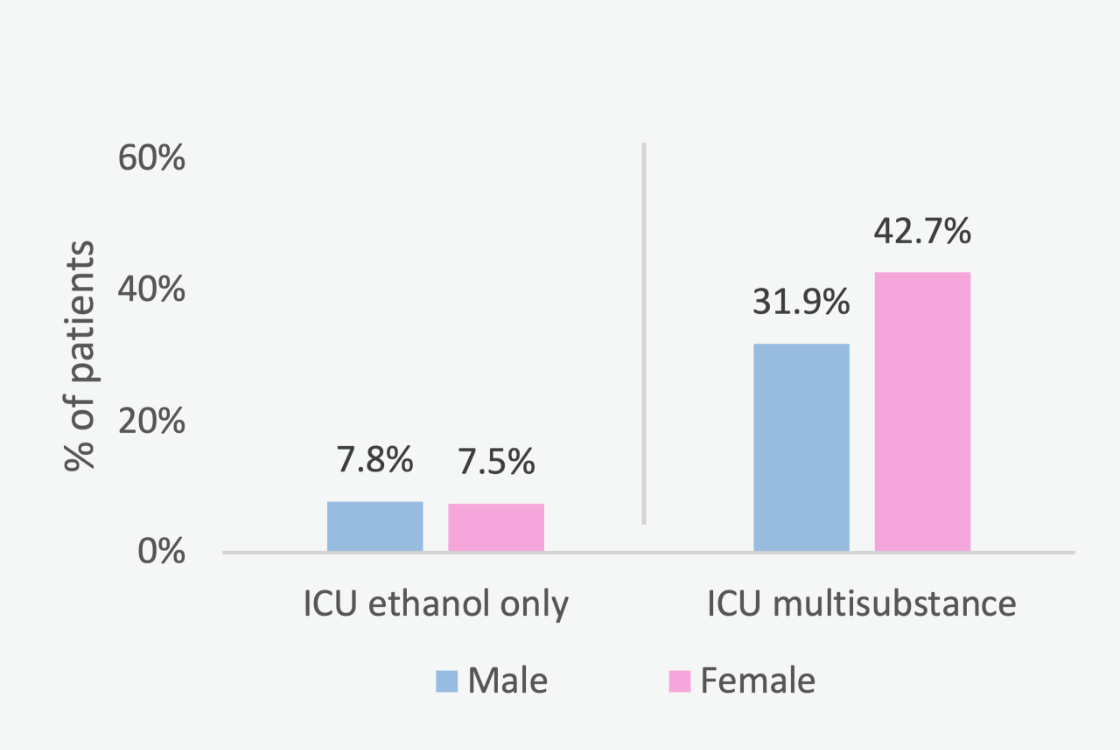

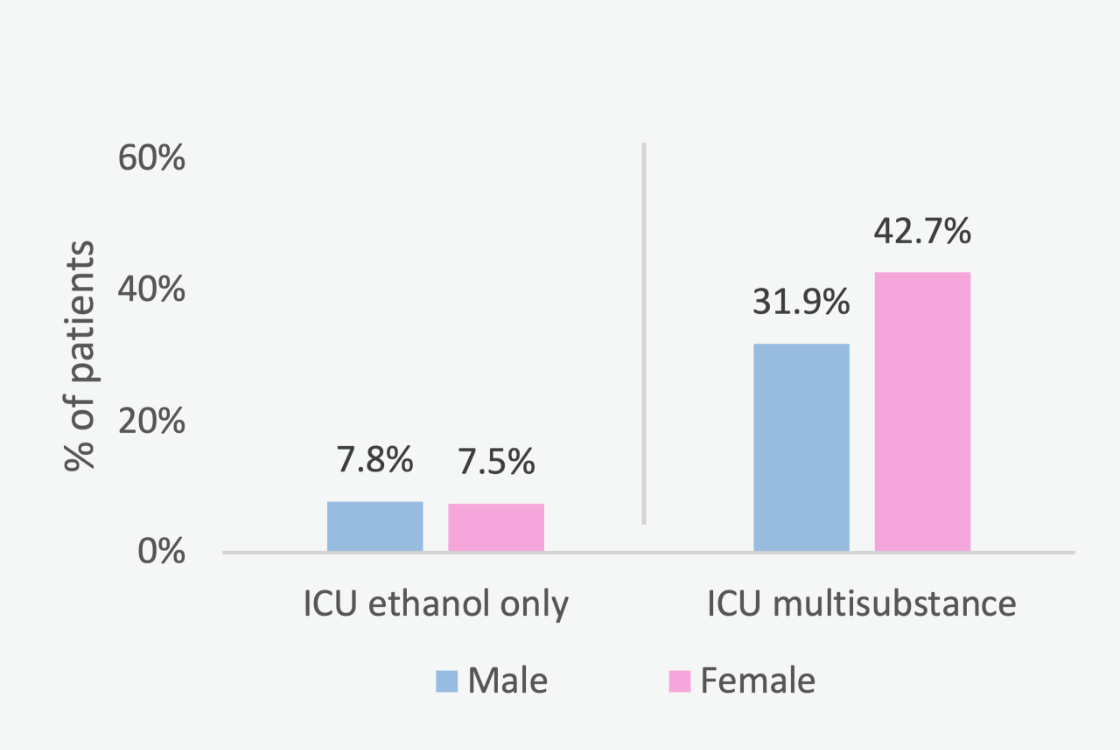

Figure 1 Transfer of ethanol-only patients to the intensive care unit, male vs female (p = 1); transfer of multisubstance patients to the intensive care unit, male vs female (p = 0.158).

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/smw.2023.40061

Ethanol intoxication is a global problem that affects all age groups, from teenagers to the elderly [1–3]. As the frequency and length of ethanol-related emergency department visits are increasing, costs relating to ethanol intoxication are escalating owing to greater demand for medical resources [46].

Intoxication from ethanol, whether alone or in combination with other substances, can result in various complications that use resources such as hospital and intensive care unit beds, medications, staff and imaging facilities in emergency departments [4, 7–9]. Time-consuming treatment of ethanol patients can intensify workload and overcrowding in emergency departments and may result in poorer medical care for other patients [4, 10, 11]. Interactions between ethanol and other compounds, along with their degradation products, may occur, affecting the absorption, distribution, metabolism and pharmacological effects of each. For example, sedative substances aggravate respiratory depression and hypotension in patients with ethanol ingestion [7, 8]. As a result, multisubstance abuse cases may be more complex, requiring additional investigation and resources.

Other Swiss studies have already shown that emergency department admissions due to ethanol intoxication is a growing phenomenon [5], often associated with multisubstance abuse [12, 13] and high numbers of referrals to psychiatry [12]. However, patients who ingested ethanol only were not distinguished from patients who presented with multisubstance abuse, and gender differences were not addressed.

Gender differences have significant implications for daily medical practice, outcomes and the impact of therapies. However, most guidelines do not take gender differences into consideration. Gender-specific medicine allows for targeted use of resources, better risk assessment and individualised follow-up [14-16]. Gender differences are of particular interest for psychiatry referrals among patients with ethanol intoxication. National U.S. surveys (2008–2010) found that female binge drinkers experienced significantly more mentally unhealthy days than males, based on the Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) questionnaire [17, 18]. A Swiss study showed that the prevalence of psychiatric disorders (major and other depressive syndromes, panic and other anxiety syndromes, bulimia nervosa and other eating disorders) in females with ethanol intoxication was significantly higher than in males after a follow-up of 7 years [19].

To the best of our knowledge, no Swiss data have been published on the intensive care unit transfer rate among ethanol intoxication patients. Although a previous Swiss study showed that the intubation rate of this patient group is relatively low, 2.3% [12], we suspected a substantially higher intensive care unit transfer rate.

Given the above points, we therefore investigated gender differences in patients with ethanol intoxication focusing on the most common ethanol-related comorbidities, intensive care unit transfers and psychiatric ward referrals.

Our retrospective analysis included all patients with signs or symptoms of ethanol intoxication (confirmed by measurement of blood ethanol concentration) admitted to the Emergency Department of the GZO Zurich Regional Health Centre. The primary aim was to provide real data from a regional hospital gender-specific differences in comorbidities, multisubstance abuse, in-hospital complications, intensive care unit transfers and referrals to psychiatric wards of these patients. Our study was approved by the Zurich Cantonal Ethics Committee (KEK- 2019-00073).

From January 2011 to December 2018, data of all emergency department patients with ethanol intoxication and a positive blood ethanol test (routine measurement) were prospectively filed in a database. Urine drug screening for cocaine, cannabis, benzodiazepines and amphetamines was performed in all patients with presumed ethanol intoxication. Subsequently, all these reports were reviewed manually, and ethanol intoxication was verified. In addition to urine drug screening results, we identified additional drug use during ethanol consumption on the basis of patient self-reporting, available information from bystanders or witnesses and the diagnosis of the physicians who examined the patient at the emergency department. Ethanol intoxication patients were assigned to the ethanol-only or the multisubstance subgroup according to whether or not they had consumed one or more of the above-mentioned additional substances. Patients who had ingested drugs that could not be classified (intake confirmed, but identity of the substance not clear) were excluded. In the case of repeat admissions of a patient, only the first admission in the given period was included in the statistical analysis. All recurrence cases were marked and excluded.

Our data were reviewed by three authors, all of whom were GCP-trained and non-blinded. All authors had to strictly follow the method protocol, which provided a clear framework for decision-making. As a result, there were no missing data. REDCap was used as the data collection software.

The cases in the ungrouped database were then retrospectively analysed according to the following prespecified criteria:

The sums and percentages of the aforementioned categorical variables were presented in PivotTables by gender in the two subgroups (ethanol-only, multisubstance). In addition, we plotted bar graphs of the percentages of intensive care unit transfers, inpatients and referrals to psychiatric wards by gender in the subgroups. For the continuous variables (age, blood ethanol concentration, hospital stay in days and ICU stay in days), we calculated the median and interquartile range (IQR).

Fisher’s exact test was performed for categorical variables on gender differences in the two subgroups. This test is suitable for small and large groups and is classified as conservative; p values are usually larger than those of the chi-squared test. Furthermore, Fisher's exact test is not based on approximations like the similar chi-squared test; it is exact [20]. For continuous variables (age, blood ethanol concentration, hospital stay in days and ICU stay in days), we conducted the Wilcoxon rank sum test for gender differences. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Several analyses were performed, but only between males and females. Therefore, no correction for multiple comparisons was necessary. All analyses were performed with R (version 3.6.1).

Name of the Ethics Committee: Kantonale Ethikkommission Zürich,approval Number/ID: 2019-00073.

The GZO Regional Hospital has general consent for the anonymous analysis of patient data. In 2019, the cantonal ethics committee confirmed this form of consent in the ethics approval.

The study cohort included 409 patients (only first admissions, with 64 recurrence cases having been excluded) aged 13 to 88 years (median age 37 years [IQR 22–49]). There were more male (n = 233, 57%) than female (n = 176, 43%) patients in the dataset. There were 236 (58%) patients in the ethanol-only subgroup and 173 (42%) in the multisubstance subgroup.

In the ethanol-only subgroup, the gender distribution was 60% males (n = 142) and 40% females (n = 94). The median age of these patients was 38 years [IQR 22–54] for males and 40 years [IQR 23–50] for females (p = 0.773). On admission, median blood ethanol levels were 2.7 g/kg [IQR 1.9–3.6] in males and 2.5 g/kg [IQR 2.0–3.1] in females (p = 0.264).

The multisubstance subgroup consisted of 53% (n = 91) males and 47% (n = 82) females. Among these patients, the median age was 32 years [IQR 23–47] for males and 35 years [IQR 23–46] for females (p = 0.433). On admission, median blood ethanol concentration measured for multisubstance patients was 1.8 g/kg [IQR 1.1–2.9] in males and 1.5 g/kg [IQR 1.0–2.2] in females (p = 0.157).

In the ethanol-only patients, the most common comorbidities were chronic ethanol abuse (47% males, 45% females; p = 0.789) followed by smoking (39% males, 42% females; p = 0.787) and psychiatric disorders (30% males, 36% females; p = 0.320). Liver diseases (13% males, 9% females; p = 0.299), lung diseases (11% males, 10% females; p = 1) and drug addiction (9% males, 10% females; p = 1) were also frequently found. Other comorbidities such as coronary heart disease, history of cancer or dementia were rare. There were no significant gender differences (table 1).

Table 1Comorbidities, ethanol-only subgroup.

| Comorbidity | # (%), total subgroup (n = 236) | # (%), subgroup males (n = 142) | # (%), subgroup females (n = 94) | p |

| Chronic ethanol abuse | 109 (46.2) | 67 (47.2) | 42 (44.7) | 0.789 |

| Smoking | 95 (40.3) | 56 (39.4) | 39 (41.5) | 0.787 |

| Psychiatric disorder | 76 (32.2) | 42 (29.6) | 34 (36.2) | 0.320 |

| Liver disease | 27 (11.4) | 19 (13.4) | 8 (8.5) | 0.299 |

| Lung disease | 24 (10.2) | 15 (10.6) | 9 (9.6) | 1 |

| Drug addiction | 22 (9.3) | 13 (9.2) | 9 (9.6) | 1 |

| Coronary heart disease | 8 (3.4) | 7 (4.9) | 1 (1.1) | 0.150 |

| History of cancer | 5 (2.1) | 2 (1.4) | 3 (3.2) | 0.389 |

| Dementia | 4 (1.7) | 4 (2.8) | 0 (0) | 0.153 |

In females with multisubstance abuse, the most frequently reported comorbidities were psychiatric disorders (61%) followed by smoking (50%), chronic ethanol abuse (32%) and drug addiction (17%). Also common were lung diseases (12%) and liver diseases (9%). Coronary heart disease, history of cancer and dementia were rare. The three most frequent comorbidities in males showed significant gender-specific differences: chronic ethanol abuse (55%, p = 0.002), drug addiction (44%, p = 0.001) and psychiatric disorders (43%, p = 0.022). For the other comorbidities, no significant gender differences were found (table 2).

Table 2Comorbidities, multisubstance subgroup.

| Comorbidity | # (%), total subgroup (n = 173) | # (%), subgroup males (n = 91) | # (%), subgroup females (n = 82) | p |

| Chronic ethanol abuse | 76 (43.9) | 50 (55.0) | 26 (31.7) | 0.002 |

| Smoking | 86 (49.7) | 45 (49.5) | 41 (50.0) | 1 |

| Drug addiction | 54 (30.6) | 40 (44.0) | 14 (17.1) | 0.001 |

| Psychiatric disorder | 89 (51.5) | 39 (42.9) | 50 (61.0) | 0.022 |

| Liver disease | 23 (13.3) | 16 (17.6) | 7 (8.5) | 0.076 |

| Lung disease | 16 (9.3) | 6 (6.6) | 10 (12.2) | 0.293 |

| Coronary heart disease | 2 (1.2) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.2) | 1 |

| History of cancer | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Dementia | 3 (1.7) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.4) | 0.604 |

The three most common additional substances in multisubstance cases revealed significant gender differences: benzodiazepines (35% males, 43% females; p = 0.014), cannabis (45% males, 24% females; p = 0.006) and cocaine (24% males, 6% females; p = 0.001). Opiates, the fourth most reported substance, showed no gender difference (table 3).

Table 3Substances in multisubstance subgroup.

| Substances | # (%), total subgroup (n = 173) | # (%), subgroup males (n = 91) | # (%), subgroup females (n = 82) | p |

| Benzodiazepines | 67 (38.8) | 32 (35.2) | 45 (42.7) | 0.014 |

| Cannabis | 61 (35.3) | 41 (45.1) | 20 (24.4) | 0.006 |

| Cocaine | 27 (15.6) | 22 (24.2) | 5 (6.1) | 0.001 |

| Opiates | 21 (12.1) | 11 (12.1) | 10 (12.2) | 1 |

| Amphetamine | 17 (9.8) | 13 (14.3) | 4 (4.9) | 0.043 |

| Paracetamol | 12 (6.9) | 6 (6.6) | 6 (7.3) | 1 |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug | 15 (8.7) | 12 (13.2) | 3 (3.7) | 0.031 |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | 8 (4.2) | 4 (4.4) | 4 (4.4) | 1 |

| Tetracyclic antidepressants | 5 (2.9) | 1 (1.1) | 5 (6.1) | 0.102 |

| Lysergic acid diethylamide | 4 (2.3) | 4 (4.4) | 0 (0) | 0.122 |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | 3 (1.7) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.4) | 0.604 |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 1 |

In the ethanol-only subgroup, 8% (n = 11) of male and 8% (n = 7) of female patients (gender difference: p = 1) were transferred to the ICU. For males and females, the median length of stay in the ICU was one day (a Wilcoxon rank sum test could not be performed for gender differences since no ICU stay exceeded one day). Seizures occurred in 2% of cases in both genders (3 males, 2 females; p = 1). There was one case of intubation / mechanical ventilation and one case of aspiration pneumonia among males, none among females (p = 1, for both).

In multisubstance cases, 32% (n = 29) of male and 43% (n = 35) of female patients (gender difference: p = 0.157) were referred to the ICU. The median length of stay in the ICU was one day for males (IQR 1–1) and females (IQR 1–2) (p = 0.141). 8% (n = 7) of males and 9% (n = 7) of females with multisubstance abuse received intubation / mechanical ventilation (p = 1). Three cases of aspiration pneumonia were reported for each gender (p = 1). Seizures occurred in 1% (n = 1) of males and 4% (n = 3) of females (p = 0.346).

The overall intubation rate across all 409 ethanol intoxication patients was 3.7%. There were no severe arrythmias (ventricular tachycardia / ventricular fibrillation / torsade des pointes) or deaths in ethanol-only or multisubstance patients (figure 1).

Figure 1 Transfer of ethanol-only patients to the intensive care unit, male vs female (p = 1); transfer of multisubstance patients to the intensive care unit, male vs female (p = 0.158).

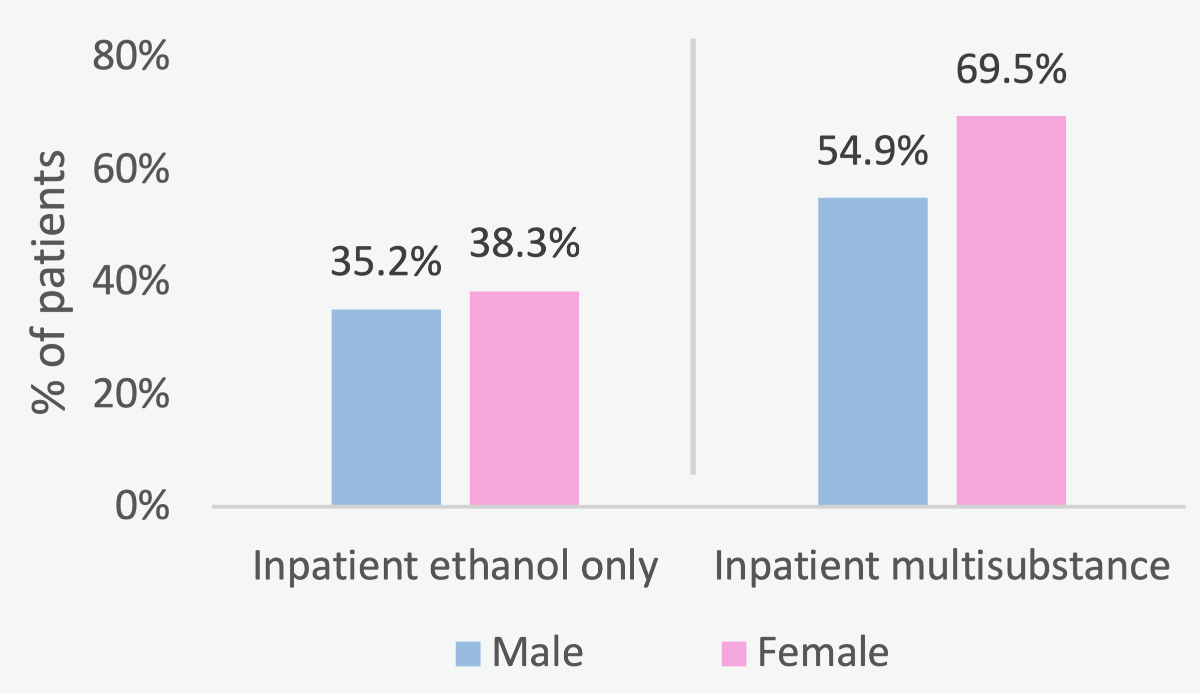

In the ethanol-only subgroup, 35% of males and 38% of females were managed as inpatients (gender difference: p = 0.679). In the multisubstance subgroup, 55% of males and 70% of females were inpatients (p = 0.060). The median length of hospital stay for ethanol-only males [IQR 1–1] and females [IQR 1–1] was one day (p = 0.273). Multisubstance inpatients, males [IQR 1–2] and females [IQR 1–2], also stayed in the hospital for a median of one night (p = 0.879) (figure 2).

Figure 2 Ethanol-only inpatients, male vs female (p = 0.679); Multisubstance inpatients, male vs female (p = 0.060).

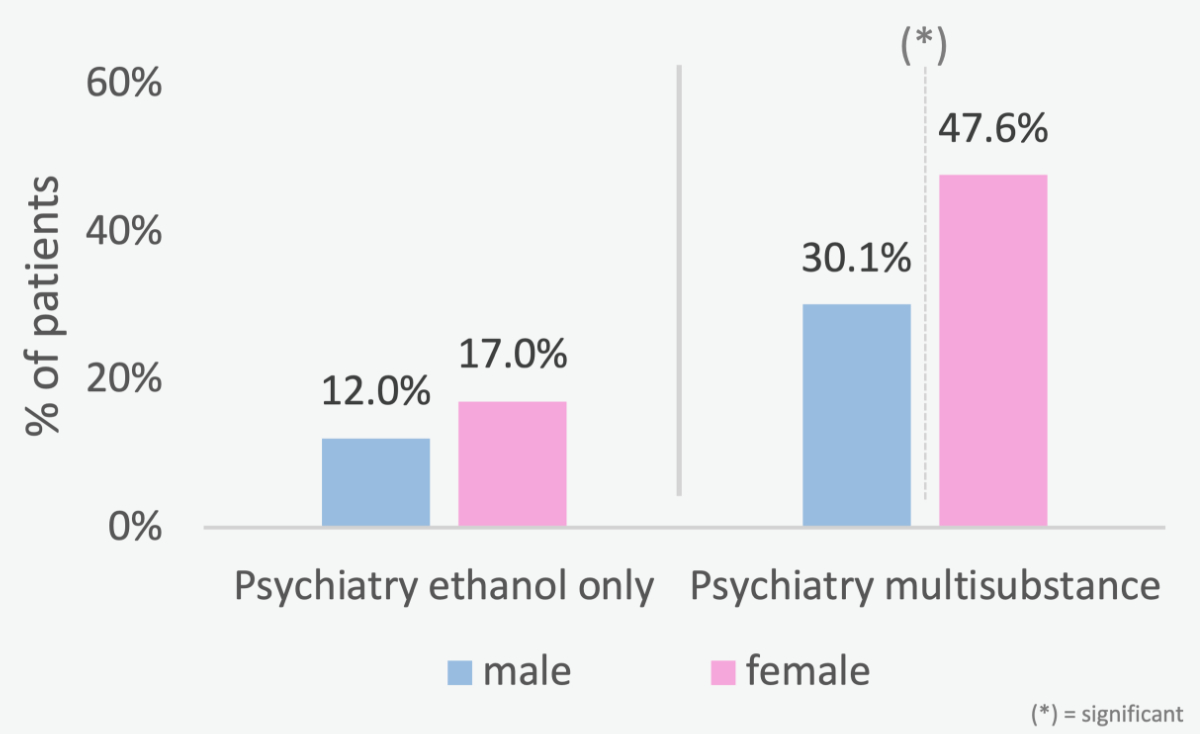

Male (30%) and female (48%) patients with multisubstance abuse showed a significant gender difference (p = 0.028) for psychiatric referral rates. This gender difference was not found among ethanol-only patients (12% males, 17% females; p = 0.338). The psychiatry ward referral rate across all 409 patients (both subgroups) was 24% (tables 4 and 5, figure 3).

Table 4Outcomes, ethanol-only subgroup.

| Outcome | # (%), total subgroup (n = 236) | # (%), subgroup males (n = 142) | # (%), subgroup females (n = 94) | p |

| Discharge home | 171 (72.5) | 106 (74.7) | 68 (72.3) | 0.762 |

| Referral to psychiatric ward | 33 (14.0) | 17 (12.0) | 16 (17.0) | 0.338 |

| Outpatient | 150 (63.6) | 92 (64.8) | 58 (61.7) | 0.679 |

| Inpatient | 86 (36.4) | 50 (35.2) | 36 (38.3) | 0.679 |

Table 5Outcomes, multisubstance subgroup.

| Outcome | # (%), total subgroup (n = 173) | # (%), subgroup males (n = 91) | # (%), subgroup females (n = 82) | p |

| Discharge home | 86 (49.7) | 51 (56.0) | 35 (42.7) | 0.092 |

| Referral to psychiatric ward | 67 (38.7) | 28 (30.1) | 39 (47.6) | 0.028 |

| Outpatient | 66 (38.2) | 41 (45.1) | 25 (30.5) | 0.060 |

| Inpatient | 107 (61.8) | 50 (54.9) | 57 (69.5) | 0.060 |

Figure 3 Ethanol-only referrals to psychiatric wards, male vs female (p = 0.338); Multisubstance referrals to psychiatric wards, male vs female (p = 0.028).

This study addressed gender-specific differences in comorbidities, multisubstance abuse, in-hospital complications, intensive care unit transfers and referrals to psychiatric wards of emergency department patients with ethanol intoxication.

Our study cohort included more males than females and the median age was slightly under 40 years, which is consistent with other studies from Switzerland [5, 12, 21]. After separation into two subgroups, ethanol-only and multisubstance, it was observed that the median age in multisubstance patients was just over 30. This is comparable to other studies that examined recreational drug use in Switzerland [22, 23]. We therefore assume that there is a substantial number of young recreational drug users in the latter subgroup. Importantly, however, our study was not designed to address recreational drug use in emergency department patients. The study addressed co-ingestion of other substances in patients admitted to the emergency department with confirmed ethanol intoxication.

A recent study from Lausanne collected all positive emergency department blood ethanol concentrations over a period of 9 years and calculated a mean of 2.11 g/kg [5].

The blood ethanol concentrations in our study were comparable.

To the best of our knowledge, no comparable data have been published on gender differences in comorbidities and outcomes of ethanol intoxication patients, with a distinction made between ethanol-only and multisubstance abuse. However, it is precisely this classification that is crucial when studying gender differences. While no gender differences were detected for ethanol-only intoxications, there were significant differences between males and females in the multisubstance group for most comorbidities studied (ethanol abuse, drug addiction and psychiatric disorders). Males with multisubstance abuse are more likely to be ethanol-dependent patients (55%) with drug co-use and/or drug dependence (44%). On the other hand, females in the multisubstance group show a higher likelihood for psychiatric disorders (61%). In ethanol-only patients, we do not see these gender differences. It can be speculated whether this observation reflects a possibly greater proportion of binge drinkers in this subgroup. Gender differences in binge drinkers are narrowing, while still significantly more males are addicted to drugs, according to a U.S. review [24].

Benzodiazepines, cannabis and cocaine were common additional substances in multisubstance cases. This is consistent with previous findings, since cocaine and cannabis are the most common everyday drugs in Switzerland [22, 25, 26]. A recent European study of recreational drugs in emergency department patients showed no differences in cocaine and cannabis use between males and females [27]. In our cohort and a recent Swiss study on emergency department ethanol intoxications [19], these differences were significant, with greater cocaine and cannabis co-use among males. Benzodiazepines act synergistically with ethanol and are the most common recreationally used / abused prescription drugs in Switzerland [13, 28, 29]. A U.S. study showed that benzodiazepine use is twice as common in females than in males [30]. In our findings, the gender difference in benzodiazepine use was smaller (35% males, 43% females), but still significant (p = 0.014). The higher psychiatric comorbidity in females with multisubstance abuse may imply that many of the benzodiazepines used / abused were prescribed by psychiatrists. However further studies are needed in this context.

No significant gender differences were found in ICU transfer rates of ethanol-only and multisubstance patients. For multisubstance patients, a significant difference could probably be found with a larger study cohort. The ICU transfer rates of ethanol-only patients (8%) are comparable to those for patients with recreational drug intoxication [23]. However, the ICU transfer rates in multisubstance patients are substantially higher (32% males, 43% females), a finding which we attribute to metabolic and pharmacological interactions including synergistic respiratory depressant effects [31]. These compounded effects of ethanol and other drugs such as opioids or benzodiazepines increase the risk for mechanical ventilation [7]. In our study, the intubation rate in multisubstance patients was approximately 8%. Nevertheless, the intubation rate was still lower than the ICU transfer rate, indicating that many patients were transferred to the ICU for monitoring and other interventions rather than primarily for intubation. Our study’s intubation rate of 3.7% among all 409 patients is comparable (2.3%) with a recent Swiss study on emergency department patients with ethanol intoxication which included patients with multisubstance abuse [12].

The psychiatric ward referral rate is remarkable, with a significant sex difference (p = 0.028) in male (30%) and female (48%) patients with multisubstance abuse. Reasons for this gender difference could be the higher proportion of psychiatric disorders in females with multisubstance abuse and the fact that binge drinking females have more mentally unhealthy days than males, as suggested in a U.S. survey [17]. A Swiss study assessed the health of emergency department ethanol intoxication patients 7 years after the related admission and found that the prevalence of psychiatrist consultation was significantly higher in women [19]. The psychiatry referral rate for all 409 patients is similar (24%) as in the other Swiss study [12].

Data were collected from 409 patients at a single hospital centre. The monocentric setting affects the power of the statistical analyses. Moreover, there may be a relevant bias because patients who had ingested ethanol but were admitted with severe trauma, respiratory or circulatory failure, for example, may have been missed. Furthermore, physicians may have decided against blood ethanol concentration measurements despite signs of ethanol intoxication; such patients were not included in our study. A larger number of patients would be required to address relevant differences regarding ICU transfers. Additionally, all psychiatric disorders (depression, anxiety disorders, personality disorders and psychotic disorders) were grouped together under one variable in our study design. There is potential for further studies addressing gender differences in distinct psychiatric disorders in patients with ethanol intoxication. Another factor that may have influenced our outcomes is the substantial number of patients with a history of multisubstance abuse.

In our study, all patients with a primary diagnosis of alcohol intoxication were included. Due to the emergency setting, no specific distinction was made between binge drinkers and non-binge drinkers. Larger multicentre studies of a region would be needed to obtain a complete picture of binge drinkers based on recurrence data. As part of our methodology, we decided to consider information from bystanders and witnesses in case of additional drug use. This can lead to bias, as this information does not have the same quality as a patient statement. Furthermore, each doctor takes an individual approach to writing patient reports. A prospective study could help to eliminate such factors. During data collection, the authors were non-blind.

Our data can only be compared with data from other large emergency departments and hospitals. The aim was not to be generalisable, but to provide the real-life numbers of a regional hospital with gender difference for further larger studies.

Gender differences in comorbidities, substance use and psychiatric ward referrals were highly evident for patients with ethanol intoxication who presented with multisubstance abuse. ICU transfers for patients with ethanol intoxication are substantial for both sexes, reflecting relevant disease burden and resource demand, as well as the need for further preventive efforts.

This study offers approaches for better personalisation of medicine on a gender basis in ethanol intoxication. Larger multicentre studies are needed for generalisability.

Funded by the Young Investigator Fund of the GZO Regional Health Center, Wetzikon

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

1. Rehm J , Mathers C , Popova S , Thavorncharoensap M , Teerawattananon Y , Patra J . Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009 Jun;373(9682):2223–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7

2. Gilvarry E . Substance abuse in young people. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000 Jan;41(1):55–80. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021963099004965

3. Hapke U . V.d.L. E, and B. Gaertner [Alcohol consumption, at-risk and heavy episodic drinking with consideration of injuries and alcohol-specific medical advice: results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56(5-6):809–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-013-1699-0

4. Mullins PM , Mazer-Amirshahi M , Pines JM . Alcohol-Related Visits to US Emergency Departments, 2001-2011. Alcohol Alcohol. 2017 Jan;52(1):119–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agw074

5. Bertholet N , Adam A , Faouzi M , Boulat O , Yersin B , Daeppen JB , et al. Admissions of patients with alcohol intoxication in the Emergency Department: a growing phenomenon. Swiss Med Wkly. 2014 Aug;144:w13982. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2014.13982

6. Bouchery EE , Harwood HJ , Sacks JJ , Simon CJ , Brewer RD . Economic costs of excessive alcohol consumption in the U.S., 2006. Am J Prev Med. 2011 Nov;41(5):516–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.045

7. Vonghia L , Leggio L , Ferrulli A , Bertini M , Gasbarrini G , Addolorato G ; Alcoholism Treatment Study Group . Acute alcohol intoxication. Eur J Intern Med. 2008 Dec;19(8):561–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2007.06.033

8. Wetterling T , Junghanns K . Alkoholintoxikierte in der Notfallmedizin. Med Klin Intensivmed Notf Med. 2019;114(5):420–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00063-018-0404-3

9. Rauscher S , Lomberg L , Schilling T . Alkoholpatienten als Risikopatienten. Notf Rettmed. 2016;19(1):28–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10049-015-0120-y

10. Pines JM , Iyer S , Disbot M , Hollander JE , Shofer FS , Datner EM . The effect of emergency department crowding on patient satisfaction for admitted patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2008 Sep;15(9):825–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00200.x

11. Mullins PM , Pines JM . National ED crowding and hospital quality: results from the 2013 Hospital Compare data. Am J Emerg Med. 2014 Jun;32(6):634–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2014.02.008

12. Sauter TC , Rönz K , Hirschi T , Lehmann B , Hütt C , Exadaktylos AK , et al. Intubation in acute alcohol intoxications at the emergency department. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2020 Feb;28(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-020-0707-2

13. Scholz I , Schmid Y , Exadaktylos AK , Haschke M , Liechti ME , Liakoni E . Emergency department presentations related to abuse of prescription and over-the-counter drugs in Switzerland: time trends, sex and age distribution. Swiss Med Wkly. 2019 Jul;149:w20056. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2019.20056

14. Regitz-Zagrosek V , Seeland U . Sex and gender differences in clinical medicine. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2012;(214):3–22.

15. Mauvais-Jarvis F , Bairey Merz N , Barnes PJ , Brinton RD , Carrero JJ , DeMeo DL , et al. Sex and gender: modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. Lancet. 2020 Aug;396(10250):565–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31561-0

16. Tanaka E . Gender-related differences in pharmacokinetics and their clinical significance. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1999 Oct;24(5):339–46. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2710.1999.00246.x

17. Wen XJ , Kanny D , Thompson WW , Okoro CA , Town M , Balluz LS . Binge drinking intensity and health-related quality of life among US adult binge drinkers. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E86. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd9.110204

18. Wilsnack RW , Wilsnack SC , Gmel G , Kantor LW . Gender Differences in Binge Drinking. Alcohol Res. 2018;39(1):57–76.

19. Adam A , Faouzi M , Yersin B , Bodenmann P , Daeppen JB , Bertholet N . Women and Men Admitted for Alcohol Intoxication at an Emergency Department: Alcohol Use Disorders, Substance Use and Health and Social Status 7 Years Later. Alcohol Alcohol. 2016 Sep;51(5):567–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agw035

20. Kim HY . Statistical notes for clinical researchers: chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test. Restor Dent Endod. 2017 May;42(2):152–5. https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2017.42.2.152

21. Haberkern M , Exadaktylos AK , Marty H . Alcohol intoxication at a university hospital acute medicine unit—with special consideration of young adults: an 8-year observational study from Switzerland. Emerg Med J. 2010 Mar;27(3):199–202. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2008.065482

22. Liakoni E , Dolder PC , Rentsch K , Liechti ME . Acute health problems due to recreational drug use in patients presenting to an urban emergency department in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2015 Jul;145:w14166. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2015.14166

23. Liakoni E , Müller S , Stoller A , Ricklin M , Liechti ME , Exadaktylos AK . Presentations to an urban emergency department in Bern, Switzerland associated with acute recreational drug toxicity. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2017 Mar;25(1):26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-017-0369-x

24. McHugh RK , Votaw VR , Sugarman DE , Greenfield SF . Sex and gender differences in substance use disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018 Dec;66:12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.012

25. Vogel M , Nordt C , Bitar R , Boesch L , Walter M , Seifritz E , et al. Cannabis use in Switzerland 2015-2045: A population survey based model. Int J Drug Policy. 2019 Jul;69:55–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.03.008

26. Baggio S , Studer J , Mohler-Kuo M , Daeppen JB , Gmel G . Profiles of drug users in Switzerland and effects of early-onset intensive use of alcohol, tobacco and cannabis on other illicit drug use. Swiss Med Wkly. 2013 Jun;143:w13805. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2013.13805

27. Miró Ò , Waring WS , Dargan PI , Wood DM , Dines AM , Yates C , et al.; Euro-DEN Plus Research Group . Variation of drugs involved in acute drug toxicity presentations based on age and sex: an epidemiological approach based on European emergency departments. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2021 Oct;59(10):896–904. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2021.1884693

28. Liang J , Olsen RW . Alcohol use disorders and current pharmacological therapies: the role of GABA(A) receptors. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2014 Aug;35(8):981–93. https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2014.50

29. Liakoni E , Walther F , Nickel CH , Liechti ME . Presentations to an urban emergency department in Switzerland due to acute γ-hydroxybutyrate toxicity. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016 Aug;24(1):107. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-016-0299-z

30. Olfson M , King M , Schoenbaum M . Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 Feb;72(2):136–42. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1763

31. Yost DA . Acute care for alcohol intoxication. Be prepared to consider clinical dilemmas. Postgrad Med. 2002 Dec;112(6):14–6. https://doi.org/10.3810/pgm.2002.12.1361