Figure 1 Methodology diagram.

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57187/smw.2023.40064

Family medicine as an academic discipline is no longer a novelty. As early as 1998, the WHO emphasised the importance of creating a department of family medicine in faculties of medicine for the purposes of offering high-quality family medicine teaching, in particular by providing practical clinical training in an family medicine setting [1]. In 2014, the European Academy of Teachers in General Practice/Family Medicine (EURACT) highlighted the key principles for homogenising family medicine education in its “Statement on Family Medicine Undergraduate Teaching” [2]. These included a need to set up a specific family medicine curriculum at the undergraduate level that favours teaching in small groups and clinical practice in family medicine practices.

In Switzerland in 2012, Bischoff et al. pointed out the important changes necessary for the practice of family medicine in view of the central place it should occupy in an effective and efficient care system [3]. The authors advocated that the core values of the profession should continue to be based on the current definitions of family medicine, including those of the World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA, table 1) after the transition [4]. In short, the goal is that future family medicine doctors will benefit from new training approaches to prepare them for the skills and roles expected in a changing healthcare environment while retaining the founding principles of the profession.

In recent years, Swiss medical schools, like other ones abroad, have developed new teaching models based on the competencies required by future doctors to meet the health requirements of society and patients [5–8]. Switzerland recently introduced a new framework for pre-graduate medical education called PROFILES (Principal Relevant Objectives and Framework for Integrative Learning and Education in Switzerland) [7, 9–13]. This framework defines the main learning objectives (General Objectives or GOs) required by doctors, the professional activities that can be entrusted at a sufficient level of autonomy by the end of the studies (Entrustable Professional Activities or EPAs) and the common clinical situations (Situations as Starting Points or SSPs) that young doctors should be able to handle. PROFILES is designed to be adapted to today's medicine, and prioritises acquisition of balanced skills so that doctors are ready to practice the profession under supervision at the end of their studies [9]. This new frame of reference is therefore a real opportunity for Swiss medical schools to adapt their teaching objectives and methods.

Indeed, in the context of implementing PROFILES at the Faculty of Biology and Medicine of the University of Lausanne, the Department of Family Medicine received a mandate to strengthen and adapt the teaching of family medicine. This directive forms the basis of our two objectives for remodelling family medicine teaching at the University of Lausanne: to determine the priority themes for teaching family medicine at the University of Lausanne and to collect expert opinions on the best ways of teaching family medicine. We further aimed to produce a coherent family medicine teaching programme encompassing the specificities of family medicine as well as the future challenges facing medicine in general, such as the management of chronic diseases, prevention and health promotion, the impacts of climate change on health and the integration of new models of care including interprofessional collaborative practice.

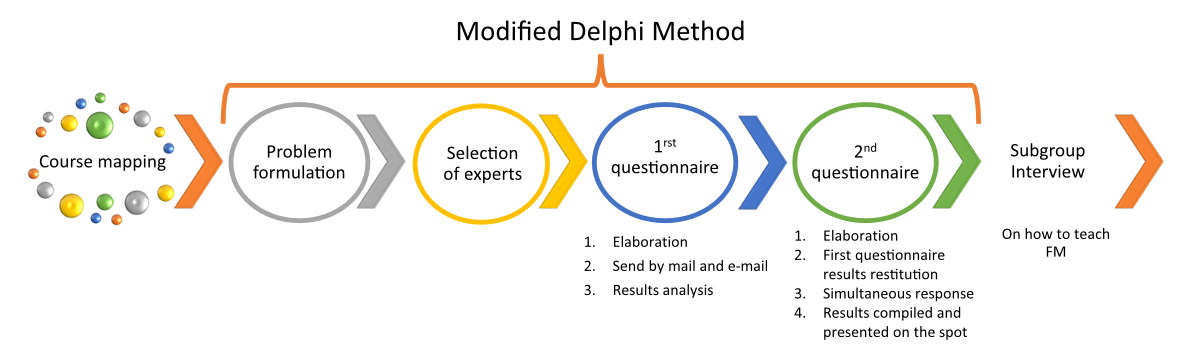

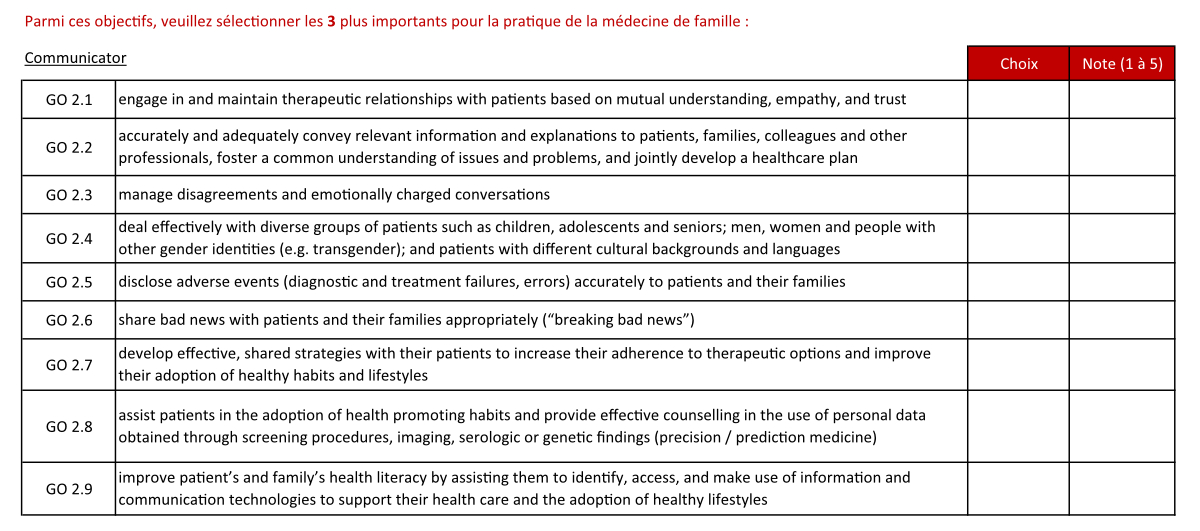

First, we mapped out the current family medicine courses at the Faculty of Biology and Medicine to obtain an overview of the current priorities of the learning objectives and teaching content (figure 1).

Figure 1 Methodology diagram.

We classified and analysed the lessons using the PROFILES grid and the principles of family medicine described by the World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA) (table 1).

Table 1The six core competencies of the family doctor according to the European WONCA definition of family medicine [3, 4].

| Primary care management |

| Person-centred care |

| Specific problem-solving skills |

| Comprehensive approach |

| Community orientation |

| Holistic approach |

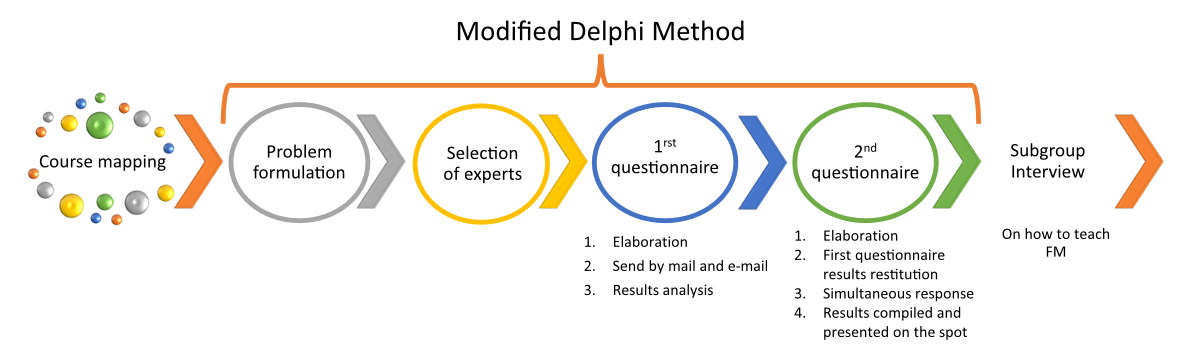

We used a modified Delphi method. As expressed by Bourrée et al., “the objective of most applications of the Delphi method is to provide expert insight into areas of uncertainty, with a view to assisting decision making” [14–16] (figure 2). The expert consensus approach was chosen to provide expert guidance on a new family medicine programme.

Figure 2 Prioritisation of family medicine teaching according to a modified Delphi method.

Step 1: Formulate the problem

The survey was based on the following problem: the methods used by family medicine teachers and clinicians to teach family medicine had developed gradually and sporadically within the medical curriculum. Following a request for family medicine accreditation by the Lausanne Medical School in 2018, the certifying body felt that the current medical course was too focused on the practice of hospital medicine and in order to restructure the family medicine teaching curriculum, researchers and teachers of the Department of Medicine must set priorities for teaching family medicine in Lausanne.

Step 2: Select the panel

We chose a panel of experts and stakeholders with different backgrounds to bring a diversity of views. We invited 33 people to join our panel (table 2). Among them, 24 were experts in their field involved and active in medical education in the French-speaking part of Switzerland. These experts had varied professional backgrounds ranging from family medicine practice to hospital-based general internal medicine; 3 experts had advanced training in medical education (CAS or Master's degree) and 2 were involved in the development of family medicine teaching at the Universities of Geneva and Fribourg. The invitees also included 5 specialist non-family medicine physicians in order to obtain the opinions of key stakeholders in medical education regarding their expectations of future family physicians.

Table 2Profile of invited participants (modified Delphi method).

| Experts | Stakeholders | ||||||

| Expert in medical pedagogy | Senior hospital doctor (GIM* specialty) | Senior hospital doctor (other medical specialty) | Family doctors involved in family medicine teaching | Registrars (GIM* specialty) | Resident | Total | |

| Invited to participate | 3 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 33 |

| Respondent in 1st round | 3 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 26 |

| Respondent in 2nd round | 3 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 20 |

* General Internal Medicine (Swiss specialty)

Step 3: Design the questionnaire

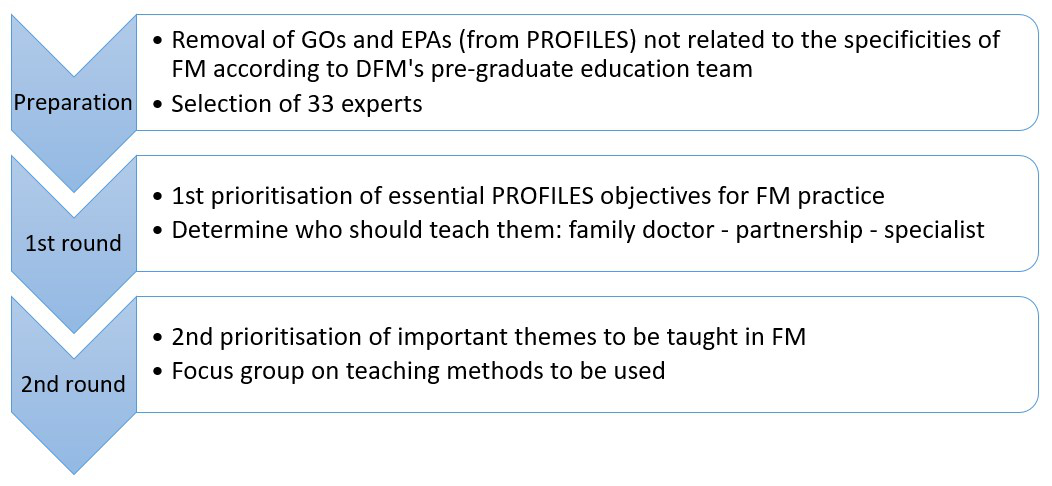

For the first round, we started with a questionnaire using the 67 general objectives (GOs) and 80 entrustable professional activities (EPAs) of PROFILES. We removed 17 GOs and 28 EPAs with no obvious link to the practice of family medicine (e.g. resuscitation of a newborn). Experts gave their opinion on the 92 remaining items (40 GOs and 52 EPAs) by answering the questionnaire received by mail and e-mail. For each item, the experts were asked to rate on a 9-point Likert scale whether they considered the item essential for family medicine practice and, if so, whether it should be taught by family doctors only, by family doctors in partnership with specialists or by other specialists only (figure 3).

Figure 3 Example of a round 1 question. For each PROFILES item, experts were asked two questions. The first was “This objective is essential to the practice of family medicine” and experts responded on a 9-point scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 9 (“strongly agree”). The second was “This objective should be taught by” and a 9-point scale was provided for the response, with 1 being “by other specialists only”, 5 being “by family doctorsand specialists in partnership” and 9 being “by family physicians only”.

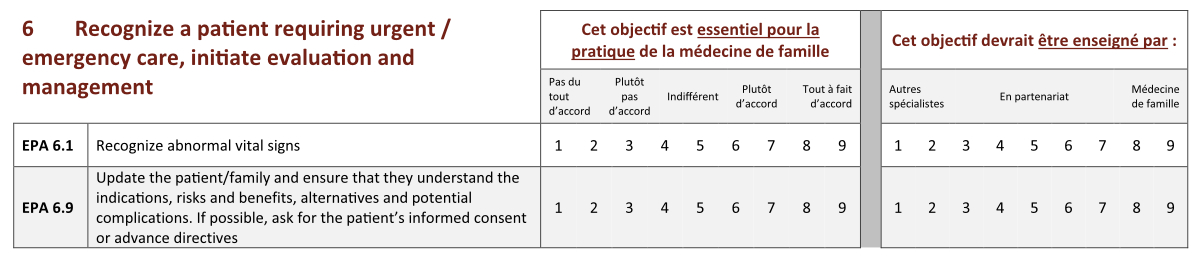

The goal of the second round was to determine which objectives are the most important for the teaching of family medicine (figure 4). Due to the high degree of consensus among the experts in the first round (strong agreement on the themes of family medicine education), it was decided to adapt the method of the second round in order to better rank the teaching priorities. The second questionnaire included GOs and EPAs with strong agreement in round 1 (individual agreement >7 and overall agreement (median) ≥7). To classify the selected items, the original subsections of the PROFILES GOs and EPAs were retained (e.g. EPA 1 - take a medical history). Each expert was asked to identify the most important items in each subsection, retaining only one third of them. For the selected items, they were asked to assign a score from 1 to 5, 1 being “important” and 5 “most important”. The purpose of this modified selection method was to allow us to identify the 20 preferential teaching objectives of family medicine (items with the highest scores).

Figure 4 Example of a round 2 question. For the “communicator” subgroup of PROFILES, the experts were asked to choose the three objectives that they felt were most important for the practice of family medicine from the nine objectives identified in the first round. They were asked to rate each of these three objectives from 1 to 5, 1 being “important” and 5 being “most important”.

For the second round, experts met in an online meeting. After hearing the results of the first round, they had 30 minutes to respond synchronously to the second questionnaire. Once completed, a member of the research team immediately compiled the results. The top 20 GOs and EPAs were identified as priority themes for family medicine education. In the same meeting, the results were presented to the experts and their impressions collected.

Given that the GOs and EPAs of PROFILES overlap and are not practical to work with in our family medicine teaching setting, the research team grouped the 20 selected items into 10 clear and recognisable themes.

Step 4: Conduct interviews

For further input in redesigning the family medicine curriculum, we asked the experts which educational methods seemed most appropriate to them for teaching the identified priority teaching objectives, as follows:

After the presentation of the results of the second questionnaire, three online discussion groups were formed: one of the three medical education experts was assigned to moderate each group and the remaining experts were assigned randomly. In each group, we conducted a semi-structured discussion on which one of the three most common methods should be used to teach family medicine at the University of Lausanne: lectures; small teaching groups; teaching in a family medicine practice setting. The moderators collected ideas and opinions and grouped them by theme. A plenary presentation of each group’s discussion was given to the other groups in order to bring out other ideas and to validate the conclusions of the moderator of each discussion group.

The various steps of the modified Delphi method were carried out from October 2020 to April 2021.

The mapping of family medicine teaching yielded a scheme of the yearly medical curriculum of the University of Lausanne taught by teaching staff of the Department of Family Medicine. Instruction by family medicine doctors in a family practice setting takes place in the 2nd and 3rd years of the Bachelor's programme (B2 and B3) and in the 1st year of the Master's programme (M1). The practical module of the 3rd year of the Master's programme (M3) consists of a compulsory one-month placement in a family medicine practice.

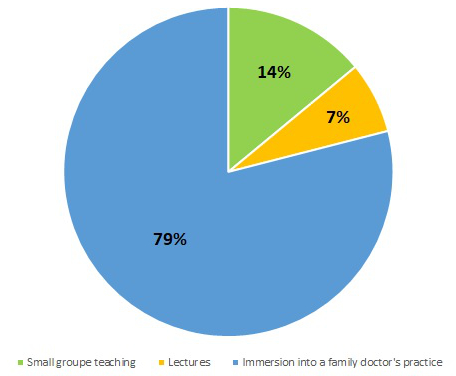

Teaching formats are diverse (figure 5), and include immersion in a family doctor's practice and teaching both in small groups and lectures. Total on-site teaching (excluding placements at family medicine practices) covers 36 hours over the whole study period and most of the specificities and diversity of family medicine are covered albeit to varying degrees. Optional courses (seminars and elective courses) are also offered.

Figure 5 Family medicine teaching methods at the University of Lausanne (% of total number of family medicine teaching hours received).

In analysing all the data collected by the mapping, all members of the research team noticed a certain lack of coherence and visibility of the family medicine courses included in the basic medical teaching curriculum. The research team found that all topics were covered but that there was a lack of consistency in the content progression of the family medicine teaching curriculum.

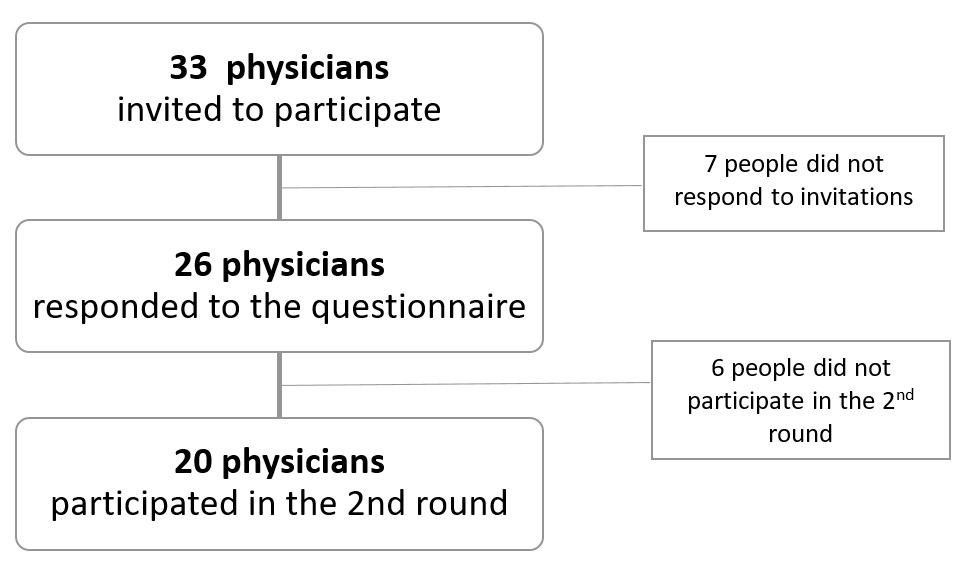

Of the 33 experts invited to participate, 26 (79% response rate) responded to the questionnaire (figure 6). The experts had individual and collective agreement ≥7 for all GOs and EPAs preselected by the department of famil medicine team. All were important to family medicine practice except for one (EPA 5.5: “Manage common post-procedural complications”), which was removed from the second questionnaire. Experts believed with moderate to strong consensus that 26 (28%) of the 92 initial GOs and EPAs essential to family medicine practice should be taught primarily by a family doctor and 66 (72%) should be taught in partnership with other specialists. Experts considered that none of the priority objectives should be taught exclusively by non-family doctor specialists.

We invited all 26 respondents from the first round to participate in the second round, answering the secondquestionnaire and participating in an online discussion group. Twenty (77% response rate) accepted (figure 6).

Figure 6 Study participants.

The second round allowed us to identify the top 20 teaching objectives (GOs and EPAs combined), i.e. those that had received the highest ratings from the experts (table 3). Results from the 20 objectives were analysed and merged into the following 10 priority themes for teaching family medicine at the University of Lausanne (from highest priority to lowest):

Table 3Priority objectives for family medicine education based on expert consensus using the modified Delphi method.

| Priority | EPA/GO | Heading | Themes |

| 1 | EPA 2.1 | Perform an accurate and clinically relevant physical examination in a logical and fluid sequence, with a focus on the purpose and the patient’s expectations, complaints and symptoms, in persons of all ages | Clinical examination |

| 2 | EPA 1.1 | Obtain a complete and accurate history in an organised fashion, taking into account the patient’s expectations, priorities, values, representations and spiritual needs; explore complaints and situations in persons of all ages; adapt to linguistic skills and health literacy; respect confidentiality | Take a medical history / doctor-patient relationship / patient-centred care |

| 3 | EPA 3.1 | Synthesize essential data from previous records, integrate the information derived from history, meaningful physical and mental symptoms and physical exam; provide initial diagnostic evaluations; take into account the age, gender and psychosocial context of the patient as well as social determinants of health | Clinical reasoning |

| 4 | GO 3.1 | Optimise healthcare delivery by identifying and understanding the roles and responsibilities of individuals such as physicians from other disciplines, nurses, pharmacists, physiotherapists, psychologists, dietitians, social workers, religious ministers and, when appropriate, the patient him/herself | Interprofessional collaboration |

| 5 | EPA 7.1 | Establish a management plan that integrates information gathered from the history, the physical examination, laboratory tests and imaging as well as the patient’s preference; incorporate the prescription of medications, physiotherapy and physical rehabilitation, dietary and lifestyle advice, psychological support, social and environmental measures into the management plan | Care planning |

| 6 | EPA 7.3 | Adopt a shared decision-making approach when establishing the management plan; take into account patients’ preferences in making orders; take into account an indication or request for complementary medicine; deal with treatment refusal; demonstrate an understanding of the patient’s and family’s current situation, beliefs and wishes, and consider any physical dependence or cognitive disorders; proceed appropriately when the patient lacks autonomous decision-making capacity | Shared decision-making |

| 7 | GO 2.1 | Engage in and maintain therapeutic relationships with patients based on mutual understanding, empathy and trust | Communication and doctor-patient relationship |

| 8 | EPA 4.1 | Recommend first-line, cost-effective diagnostic evaluations for patients with an acute or chronic disorder or as part of routine health maintenance | Cost-effective care |

| 9 | GO 1.9 | Establish a patient-centred, shared management plan and deliver high-quality cost-effective preventive and curative care, especially when the patient is vulnerable and/or multimorbid (elderly) or has a terminal illness | Care planning |

| 10 | EPA 6.1 | Recognise abnormal vital signs | Assessment of urgency |

| 11 | GO 1.7 | Analyse and interpret data to establish a differential and a working diagnosis (clinical reasoning) | Clinical reasoning |

| 12 | GO 5.2 | Incorporate health surveillance activities into interactions with individual patients (discussion of lifestyle, counselling). Such activities include screening, immunisation and disease prevention, risk and harm reduction measures and health promotion. | Health promotion |

| 13 | EPA 8.1 | Document and record the patient’s chart; filter, organise, prioritise and synthesize information; comply with requirements and regulations | File documentation |

| 14 | EPA 2.4 | Identify, describe, document and interpret abnormal findings of a physical examination. Assess vital signs (temperature, heart and respiratory rate, blood pressure) | Clinical examination |

| 15 | GO 3.2 | Communicate with respect for and appreciation of team members, and include them in all relevant interactions; establish and maintain a climate of mutual respect, dignity, integrity and trust | Interprofessional collaboration |

| 16 | EPA 1.3 | Use patient-centred, hypothesis-driven interview skills; be attentive to patient’s verbal and nonverbal cues, patient/family culture, concepts of illness; check need for interpreting services; approach patients holistically in an empathetic and non-judgmental manner | Patient-centred care / Doctor-patient relationship |

| 17 | EPA 3.2 | Assess the degree of urgency of any complaint, symptom or situation | Assessment of urgency |

| 18 | GO 2.2 | Accurately and adequately convey relevant information and explanations to patients, families, colleagues and other professionals; foster a common understanding of issues and problems; and jointly develop a healthcare plan | Doctor-patient relationshipInterprofessional collaboration |

| 19 | GO 7.5 | Recognise that the patient’s wishes and preferences are central to medical decision-making (“shared decision-making”) | Shared decision-making |

| 20 | GO 1.6 | Conduct an effective general or specific physical examination | Clinical examination |

Regarding the different teaching formats, the relevant points emerging from the three discussion groups are detailed below.

Immersion in a family doctor's practice

For this mode of teaching, the experts thought that students should be better prepared before the practice placements in order to benefit fully from them. They also thought it useful to offer family doctor teachers some flexibility in developing their own in-house curriculum for teaching processes that take into account student needs and expectations. They recommended offering special support for students with difficulties. For family medicine teachers, they indicated the necessity of understanding the student competences required by the university as they progress through the curriculum to help the students to better specify and achieve their personal goals.

Another proposal was that each student should have a single family medicine supervisor as mentor throughout the curriculum. This method would have the advantage of providing a strong role model, favouring a humanistic and continuous relationship. On the other hand, for some, this type of mentoring might bring a somewhat less inspiring approach with less diverse educational experience.

Finally, to engage successfully in a family doctor's practice, the in-practice teaching should be structured, coherent and continuous.

Lecture courses

According to the expert discussion groups, the traditional teaching format should be maintained in order to stimulate student interest in family medicine. Lectures provide an opportunity to prepare students for placement in a family medicine practice. Lectures should address specific family medicine themes (uncertainty, unexplained symptoms, shared decision-making, for example), foster partnerships with other specialists and health professionals in the form of joint courses and finally, patient partners. The experts indicated that the lecture course format should start earlier in the curriculum (currently it is mainly at the Master’s level).

Teaching in small groups

Experts thought small group teaching should be structured and follow the prior knowledge of the students ((based on students' existing body of knowledge?)). Diverse and less common teaching formats should be favoured in these groups such as problem-based learning, flipping classrooms (a teaching method in which students work on the material before coming to class) and simulations. Lessons in small groups could also be an opportunity to mix with other medical specialists, for example using video conferencing. Experts also suggested that team-based learning should be avoided at the beginning of student education. The content of group lessons should focus on realistic topics relevant to family medicine and aim to recognise situations requiring specialist skills.

The mapping of family medicine courses at the University of Lausanne allowed us to visualise that the content of the current programme is suitable and consistent with the key teaching principles proposed by EURACT [2]. However, we can raise concerns about the lack of definition, visibility and coherence of the courses, which are delivered in a scattered and fragmented manner over time and sometimes only reach some of the students (via seminars and electives). In addition, most of the theoretical aspects of family medicine arrive too late in the curriculum and it is likely that small group learning would be more effective with this theoretical content, currently provided in already existing lectures [17]. Finally, our research team showed that there was pedagogical interest for certain teaching methods that are not used; these include simulations, problem-based learning, team-based learning and self-learning (e.g. e-learning).

In general, family medicine teaching should be organised better and be consistent and coordinated throughout the curriculum, both for students and teachers. This means a redefinition of family medicine teaching to offer a longitudinal learning experience throughout the medical curriculum. Personalised teaching would allow understanding and meet specific student needs. Experts pointed out the need for students to be better prepared on the specificities of family medicine before the immersion in a doctor's practice. This could be done throughout the existing lectures and in small group learning.

The early involvement of medical students directly in a medical practice from the 2nd year of the Bachelor's degree and repeated in B3 and M1 years of the family medicine curriculum at the University of Lausanne is a clear benefit to family medicine teaching, in agreement with the literature [18]. To strengthen and standardise family medicine teaching in practices, it seems essential to improve the quality and increase the frequency of evaluation of these practical learning experiences. In this respect, efforts should be continued to provide systematic continuous education in medical pedagogy, allowing family medicine physician teachers to acquire specific teaching skills [19, 20]. For example, the College of Family Physicians of Canada has developed a framework for faculty development [21] describing the fundamental teaching activities of family medicine. Adopting such a tool for physician teachers seems essential for consistent and high-quality family medicine teaching.

Using the modified Delphi method, we were able to identify priority topics for family medicine education and define a way to teach them. A limitation of our study was the difficulty in ranking the important themes given that all the experts had agreed on the importance of all GOs and EPAs proposed; for this reason, the researchers had to modify the second-round questionnaire in order to force the experts to prioritise the objectives of family medicine teaching. On the other hand, via the use of semi-structured interviews in small discussion groups, we obtained qualitative estimates from experts concerning their favoured teaching methods for family medicine and also their suggestions for improving existing teaching modes.

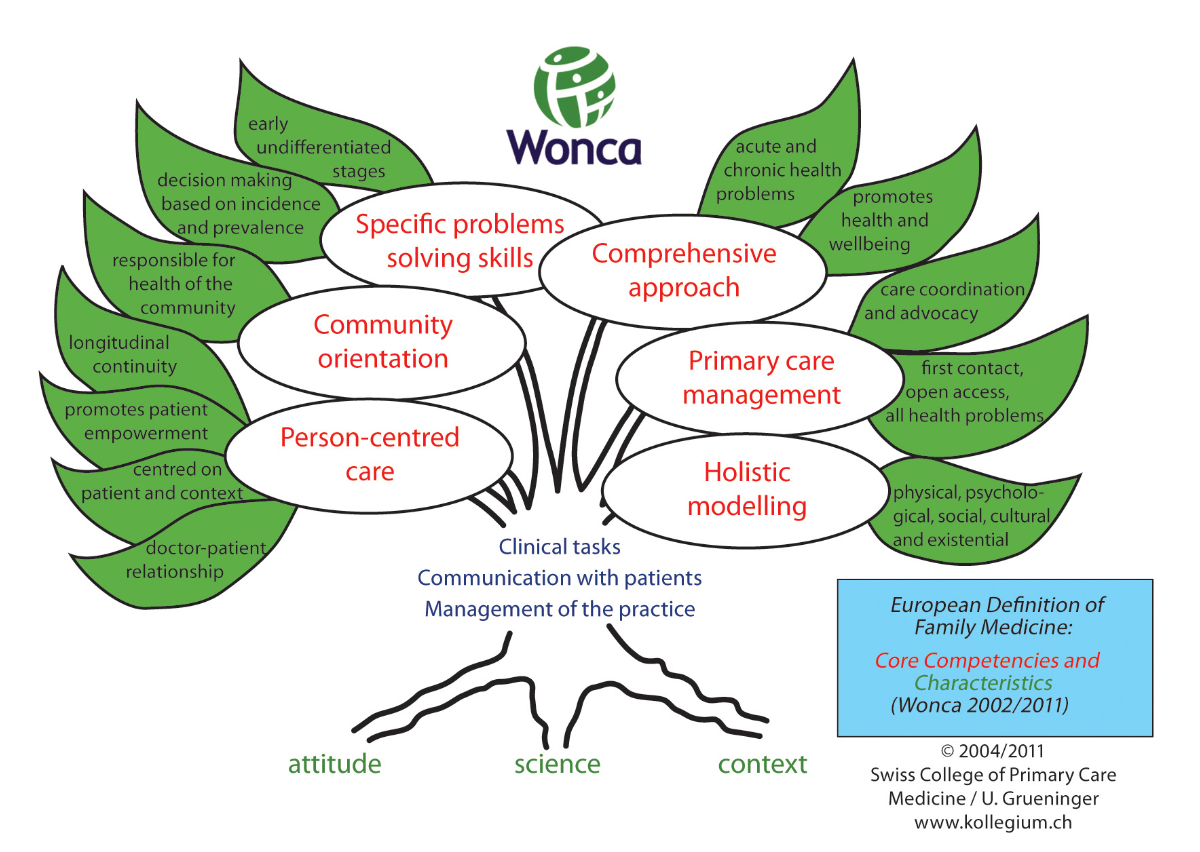

Some of the teaching objectives prioritised by our expert group —namely teaching how to take medical histories and perform clinical examinations, communication skills, doctor-patient relationship skills ability and clinical reasoning— correspond to the WONCA [4] definition of family medicine, traditionally represented by a tree (figure 7). The tree illustrates the characteristics of the family medicine profession and the necessary skills of a family doctor; its strong trunk symbolises a rigorous clinical approach and good communication with the patient.

Figure 7 The WONCA tree representing the European definition of family medicine [4].

Further links can also be made to the European WONCA definition of family medicine, including person-centred care, continuity of care and a holistic approach in managing acute and chronic problems and ensuring health promotion. It is interesting to note however that our expert group did not prioritise community orientation or management of family medicine practices, which we believe is important for primary care in the future. On the other hand, they clearly mentioned teaching interprofessional collaboration as a priority for family medicine education, although this objective is not a primary concern in WONCA's definition of family medicine. The priority accorded to teaching interprofessional collaboration by our expert group is fully consistent with the current teaching strategy of the Faculty of Biology and Medicine and of many other medical schools around the world. Indeed, the Department of Family Medicine received a mandate from the Faculty of Biology and Medicine to include the teaching of interprofessional collaborative practice in the primary care setting.

The group of experts were generally in favour of increasing joint teaching between family doctors and other specialists. In particular, they felt that clinical examination should be taught in partnership. This combining of skills, whatever the teaching method, would be particularly useful for students to refine their perception of differences in the clinical examination between specific medical specialties and family medicine, thereby promoting interdisciplinary work and cooperation. Currently, several family medicine lectures at the University of Lausanne are already taught as a specialist/family doctor pair and this seems to be highly appreciated by students, according to feedback we have received from them. A structured review process should be done to confirm the interest in this model.

A reference teacher or role model has been shown to influence learner behaviour, professional attitude and career choices [22, 23]. Giving students the opportunity to identify strongly with family medicine teachers via frequent placements in family medicine practices during their studies is an option that the Department of Family Medicine teaching team intends to implement. The introduction of this type of mentorship could invigorate the motivation of students and provide them with an opportunity to acquire high-quality family medicine skills for those intending to pursue a career in family medicine.

Despite the identified limitation, the use of the modified Delphi method allowed us to clarify the current family medicine teaching programme at the Faculty of Biology and Medicine and to collect information that paves the way for restructuring and improving family medicine education. The priority themes for family medicine teaching, selected by a panel of experts and stakeholders, can be used to define learning objectives for lectures, small group teaching and practical clinical placements. The future family medicine curriculum will be more structured and visible, which might help to build higher-quality family medicine teaching.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

1. WHO Europe , Framework for professional and administrative development of general practice / family medicine in Europe. 1998.

2. Carelli F . EURACT statement on family medicine undergraduate teaching EURACT: european Academy of Teachers in general practice/family medicine. Eur J Gen Pract. 2014 Sep;20(3):238–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/13814788.2014.946009

3. Bischoff T , et al. [Tomorrow’s family doctor]. Rev Med Suisse. 2012;8:1033–41.

4. Commission of the Council of Wonca Europe , The european definition of general practice / family medicine. 2011.

5. Carraccio CL , Englander R . From Flexner to competencies: reflections on a decade and the journey ahead. Acad Med. 2013 Aug;88(8):1067–73. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318299396f

6. Frank JR , Mungroo R , Ahmad Y , Wang M , De Rossi S , Horsley T . Toward a definition of competency-based education in medicine: a systematic review of published definitions. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):631–7. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.500898

7. Sohrmann M , Berendonk C , Nendaz M , Bonvin R ; Swiss Working Group For Profiles Implementation . Nationwide introduction of a new competency framework for undergraduate medical curricula: a collaborative approach. Swiss Med Wkly. 2020 Apr;150(1516):w20201. https://doi.org/10.57187/smw.2020.20201

8. Walsh A , Koppula S , Antao V , Bethune C , Cameron S , Cavett T , et al. Preparing teachers for competency-based medical education: fundamental teaching activities. Med Teach. 2018 Jan;40(1):80–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1394998

9. Cornuz J , Bochud M , Bodenmann P , Senn N , Staeger P . Quels seront les profiles des médecins généralistes et de santé publique de demain? Rev Med Suisse. 2019 Oct;15(669):1959–60. https://doi.org/10.53738/REVMED.2019.15.669.1959

10. Michaud, P., P. Jucker-Kupper, and Members of the Profiles working group, PROFILES; Principal Objectives and Framework for Integrated Learning and Education in Switzerland. Bern: Joint Commission of the Swiss Medical Schools; 2017.

11. Michaud PA , Jucker-Kupper P , The P ; The Profiles Working Group . The “Profiles” document: a modern revision of the objectives of undergraduate medical studies in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2016 Feb;146:w14270. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2016.14270

12. Joint Commission of the Swiss Medical Schools . Principal Relevant Objectives and Framework for Integrated Learning and Education in Switzerland. 2017; Available from: http://profilesmed.ch/

13. Bart PA , Monti M , Gachoud D , Félix S , Turpin D , Marino L , et al. [PROFILES: typical portrait of the future Swiss doctors]. Rev Med Suisse. 2020 Jan;16(678):133–7. https://doi.org/10.53738/REVMED.2020.16.678.0133

14. Bourrée F , Michel P , Salmi LR . Méthodes de consensus: revue des méthodes originales et de leurs grandes variantes utilisées en santé publique. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2008 Dec;56(6):415–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respe.2008.09.006

15. Dalkey N . An experimental study of group opinion: the delphi method. Futures. 1969;1(5):408–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-3287(69)80025-X

16. Letrilliart L , Vanmeerbeek M . A la recherche du conensus: quelle méthode utiliser? Exercer. 2011;99:170–7.

17. Burgess A , van Diggele C , Roberts C , Mellis C . Facilitating small group learning in the health professions. BMC Med Educ. 2020 Dec;20(S2 Suppl 2):457. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02282-3

18. Turkeshi E , Michels NR , Hendrickx K , Remmen R . Impact of family medicine clerkships in undergraduate medical education: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015 Aug;5(8):e008265. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008265

19. Audétat MC , et al. Superviser un-e étudiant-e au cabinet du médecin généraliste, quels enjeux? Prim Hosp Care. 2022;22(1):24–8.

20. Srinivasan M , Li ST , Meyers FJ , Pratt DD , Collins JB , Braddock C , et al. “Teaching as a Competency”: competencies for medical educators. Acad Med. 2011 Oct;86(10):1211–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c5b9a

21. Le Collège des médecins de famille du Canada. Activités pédagogiques fondamentales en médecine de famille: un référentiel pour le développement professoral. 2015; Available from: https://medfam.umontreal.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/FTA_GUIDE_MC_FRE_Apr_REV.pdf

22. Jochemsen-van der Leeuw HG , van Dijk N , van Etten-Jamaludin FS , Wieringa-de Waard M . The attributes of the clinical trainer as a role model: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013 Jan;88(1):26–34. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318276d070

23. Lemire F . Role modeling in family medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2018 Oct;64(10):784.