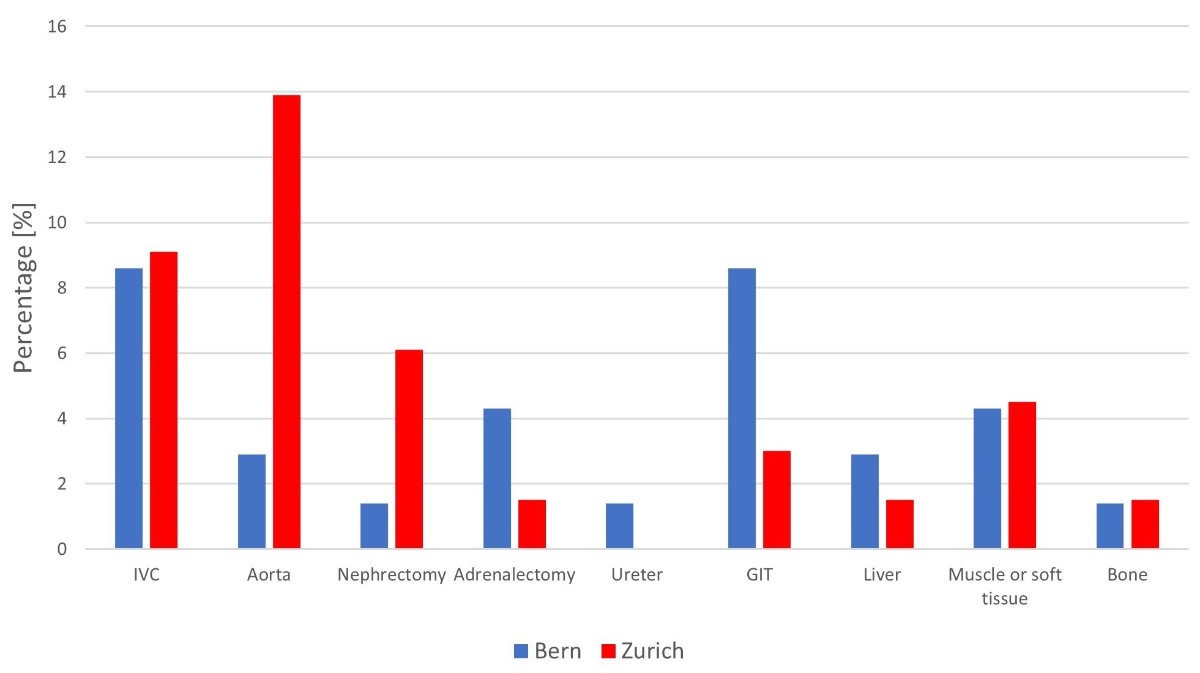

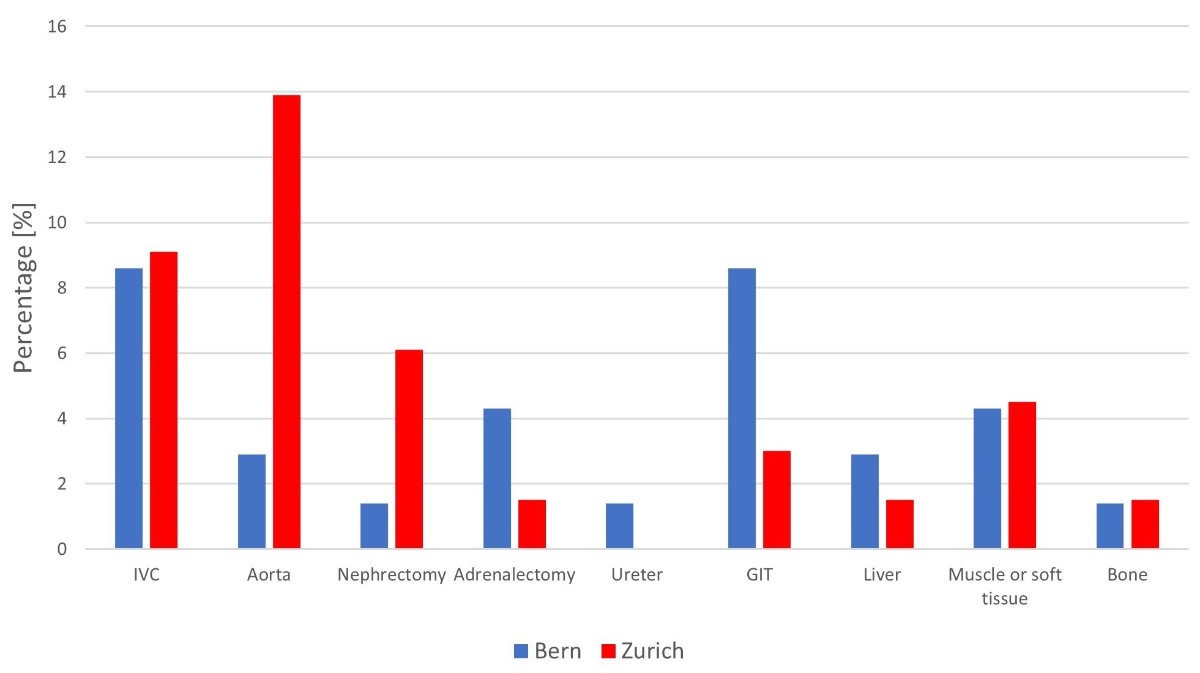

Figure 1 Additional procedures during post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection by centre (IVC: inferior vena cava; GIT: gastrointestinal tract).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.57187/smw.2023.40053

Germ cell tumours (GCT) are the most common solid malignancy in men 20 to 35 years of age and account for approximately 1% of all male malignancies [1]. An estimated 470 men were newly diagnosed with GCT every year in Switzerland between 2013 and 2017 [2].

Non-seminoma patients with metastatic disease are typically treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Nevertheless, 25% to 50% of these patients will have residual retroperitoneal masses after chemotherapy [3, 4]. Guidelines recommend post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymphnode dissections (PC-RPLND) of residual retroperitoneal masses >1 cm (post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection) for non-seminoma [5–7]. The rationale for PC-RPLND is to remove lymph nodes that may contain viable cancer in 15% and teratoma in 45% of patients [8]. Being resistant to chemotherapy, teratomas have the potential to grow, transform into malignancy, and relapse at a later time, if left unresected [9, 10]. The multidisciplinarity of this approach results in overall survival rates exceeding 90% and serves as a model for the treatment of other solid tumours [11].

Studies from high-volume centres report outcomes of PC-RPLND with complication rates ranging from 4% to 35% and a mortality rate of approximately 1% [12–18]. To our knowledge, there have been no such reports from Switzerland so far.

This study aimed to evaluate surgical complication rates and oncological outcomes after PC-RPLND at two university hospitals in Switzerland.

As a quality control measure at the two participating institutions, we performed a retrospective chart review of in- and outpatient admissions of newly diagnosed germ cell tumour patients, tumour board protocols and operating room schedules at the departments of urology of the university hospitals in Bern and Zürich to identify all patients who underwent post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for germ cell tumours from 2010 to 2020. Subsequently, we reviewed all medical records of identified patients to capture information at baseline, pre and post surgery, and at follow-up using structured paper-based case report forms. A list of variables captured in the case report forms can be obtained by the corresponding author. Attempts were made to obtain missing clinical information by contacting referring or follow-up institutions. Data from patients with a second PC-RPLND during the study period were also captured but not included in the final data analysis. All captured data was subsequently entered by one of the authors (MN) into a central SPSS database (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA, Version 28.0.1.1). Plausibility checks and extensive data cleaning to correct entry errors were performed by two of the authors (MN and JB) before analysis. The database was locked to entries on April 22nd 2022.

Baseline and pre-operative characteristics included the site and histology of the primary tumour, clinical staging information, the International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group (IGCCCG) prognostic classification, number of cycles and type of chemotherapy, and serum tumour marker levels pre-chemotherapy and pre-operatively. Normal serum tumour marker levels were defined as alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) less than 10 μg/l and human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) less than 5 U/l. The size of a retroperitoneal mass at diagnosis and before retroperitoneal lymph node dissection was determined by measuring the largest short-axis diameter of the retroperitoneal mass on computed tomography (CT) imaging. Measurements in the craniocaudal axis were not considered.

According to the guidelines of the European Germ Cell Cancer Consensus Group (EGCCCG), PC-RPLND was indicated in non-seminoma patients with residual retroperitoneal masses larger than 1 cm [5]. Surgical templates were chosen by the lead surgeon according to guidelines based on the sidedness of the primary tumour, the location and the size of the residual mass. Surgical reports were reviewed for information on the resection area (template), additional procedures and intraoperative complications. Further perioperative outcomes included intraoperative blood loss, operative time and length of hospital stay. Postoperative complications were recorded until the day of discharge and graded according to the classification by Clavien and Dindo [19]. If a patient had more than one complication, the highest grading was taken for further analysis. Postoperative ileus was radiologically confirmed, defined as the requirement for a nasogastric tube, or defined when the passage of flatus or stool and tolerance of an oral diet did not occur until day 4 postoperatively. [20]. All available records were analysed for late complications and readmission up to 90 days after surgery.

Outcomes of interest were the occurrence of intraoperative complications (defined as an estimated blood loss ≥1000 ml, any reported intraoperative injuries or the need for relaparotomy), the occurrence of any postoperative complication, increased resource demands (defined as a length of postoperative stay in the intensive care unit >1 day, total length of postoperative stay >7 days or readmission within 90 days) and oncological outcomes. Oncological outcomes consisted of type and localisation of relapse and progression-free and overall survival probabilities. Progression-free survival (PFS) started on the day of PC-RPLND and ended on the day of documented progression or death. Progression was defined as serological or radiological, whichever occurred first. Overall survival (OS) started on the day of PC-RPLND and ended on the day of the last follow-up visit. A patient was declared lost to follow-up if we were unable to obtain information about his follow-up status despite contacting follow-up institutions, or if he did not return to the follow-up institution for further visits. Patients lost to follow-up were censored at the time of their last contact. Missing data is indicated in the tables wherever appropriate. We undertook no measures to replace or do substitute calculations for any missing values.

Descriptive statistical analyses were performed on relevant parameters. Significance was tested using Pearson’s χ 2-test of independence and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U test for metric variables. PFS and OS probabilities were analysed using the Kaplan-Meier method. The significance of survival analyses was tested using the log-rank test. A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. All tests were performed using the SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA, Version 28.0.1.1) and STATA (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA, Version 10.1, 2008) software packages. Due to the design of the study, all statistical analyses must be considered hypothesis-generating.

The study was approved by the local ethical committee (BASEC ID 2020-02237). All patients gave written general consent.

A total of 136 patients were identified and included in the study: 70 patients from Bern and 66 patients from Zürich. They underwent a total of 141 PC-RPLND; 5 second PC-RPLNDs were excluded from the analysis.

The overall median (range) age at PC-RPLND was 31.3 (17.3–69.8) years; 101/136 (74.3%) of patients were <40 years old. The primary site of the tumour was the testis in 94.6% of patients, and 89.7% of histopathology results at orchiectomy revealed non-seminoma. PC-RPLND for patients with pure seminoma at initial diagnosis was performed in 10/136 (7.4%) patients. The histopathological results of the resected specimens of those 10 seminoma patients eventually showed teratoma in 2, seminoma in 2, and necrosis or fibrosis in the remaining 6.

All patients received systemic chemotherapy before RPLND consisting of a median (range) of 4 (1–18) treatment cycles: 118/136 (86.8%) received first-line chemotherapy, 15/136 (11.0%) had one additional salvage chemotherapy, 2 had a second salvage chemotherapy, and 1 was treated with a third salvage chemotherapy before PC-RPLND. Overall, 12/136 (8.8%) patients received high-dose chemotherapy, either upfront or in addition to conventional-dose chemotherapy. No significant association existed between treatment with high-dose chemotherapy and the occurrence of intra- or postoperative complications. The median time from the end of chemotherapy to PC-RPLND was shorter for Zürich than for Bern (2.1 months vs 6.2 months, p <0.001).

Overall, preoperative AFP levels were elevated in 16/136 (11.8%) patients, and HCG levels were elevated in 6/136 (4.4%) patients. Half of all the patients with elevated tumor markers had increasing markers before surgery.

The size of the residual retroperitoneal mass before PC-RPLND did not significantly differ between Bern and Zürich. Preoperative imaging studies showed increasing size in 38/136 (27.9%) of all patients compared to previously obtained images.

Data on patients’ baseline and preoperative characteristics are shown in table 1 and supplementary tables 1 and 2.

Table 1Patients’ baseline and preoperative characteristics.

| Bern | Zürich | Overall | |||

| n = 70 (51.5%) | n = 66 (48.5%) | n = 136 (100%) | |||

| Age at PC-RPLND (years), median (range) | 30.7 (17.3–63.8) | 31.8 (17.6–69.8) | 31.3 (17.3–69.8) | ||

| Body mass index at PC-RPLND (kg/m2), median (range) | 25.9 (17.7–39.5) | 25.5 (19.6–36.5) | 25.6 (17.7–39.5) | ||

| Site of primary tumour, number (%) | Gonadal | 67 (95.7) | 62 (93.9) | 129 (94.9) | |

| Primary retroperitoneal | 3 (4.3) | 4 (6.1) | 7 (5.1) | ||

| Histopathology subtype and pattern in primary tumour, number (%) | Pure seminoma | 7 (10.0) | 3 (4.5) | 10 (7.4) | |

| Non-seminoma/mixed germ cell tumour | 61 (87.1) | 61 (92.4) | 122 (89.7) | ||

| Non-seminoma with teratomatous elements | 35 (50.0) | 35 (53.0) | 70 (51.5) | ||

| Burned-out tumour/scar only | 2 (2.9) | 2 (3.0) | 4 (2.9) | ||

| Type of chemotherapy regimen before PC-RPLND, number (%) | Primary chemotherapy | 56 (80.0) | 62 (94.0) | 118 (86.8) | |

| First salvage chemotherapy | 13 (18.6) | 2 (3.0) | 15 (11.0) | ||

| Second and third salvage chemotherapy | 1 (1.4) | 2 (3.0) | 3 (2.2) | ||

| Time from end of chemotherapy to PC-RPLND (months), median (range) | 6.2 (0.5–54.2) | 2.3 (0.5–327.6) | 3.8 (0.5–327.6) | ||

| Serum tumour markers at PC-RPLND | AFP elevated (≥10 μg/l) | Number (%) | 9 (12.9) | 7 (10.6) | 16 (11.8) |

| Increasing marker levels | 5 (7.1) | 3 (4.5) | 8 (5.9) | ||

| Median (range) | 253.8 (19.7–853) | 48.0 (12.8–13,860) | 97.0 (12.8–13,860) | ||

| HCG elevated (≥5 U/l) | Number (%) | 4 (5.7) | 2 (3.0) | 6 (4.4) | |

| Increasing marker levels | 3 (4.3) | – | 3 (2.2) | ||

| Median (range) | 62.0 (5.0–691.0) | 157.5 (8.0–307.0) | 62.0 (5.0–691.0) | ||

| Largest diameter of retroperitoneal mass at PC-RPLND (mm), median (range)* | 33.0 (8–160) | 31.0 (8–126) | 32.0 (8–160) | ||

| Trend of retroperitoneal mass before PC-RPLND, number (%) | Increasing | 21 (30.0) | 17 (25.8) | 38 (27.9) | |

| Decreasing | 20 (28.6) | 37 (56.1) | 57 (41.9) | ||

| Stable | 29 (41.4) | 9 (13.6) | 38 (27.9) | ||

| Mixed response | – | 2 (3.0) | 2 (1.5) | ||

| Missing values | – | 1 (1.5) | 1 (0.7) | ||

PC-RPLND: post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection; AFP: alpha-fetoprotein; HCG: human chorionic gonadotropin

* Corresponds to the largest short-axis diameter (anterior–posterior [sagittal] and lateral [transverse] axis). Measurements in the craniocaudal (longitudinal) axis were not considered.

Overall, 77/136 (56.6%) patients had a stable partial response with negative tumour markers after chemotherapy. In 26/136 (19.1%) patients, a growing teratoma syndrome was suspected. Overall, 20/136 (14.7%) patients had a relapse more than 2 years after the initial remission and were considered a late relapse before surgery; 5/136 (3.7%) were treated as a redo procedure, i.e., they had undergone a previous retroperitoneal lymph node dissection before the study period elsewhere (see table 2).

Table 2Surgical data post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection.

| Bern | Zürich | Overall | ||

| n = 70 (51.5%) | n = 66 (48.5%) | n = 136 (100%) | ||

| Remission status/indication for PC-RPLND, number (%) | Partial response marker negative | 35 (50.0) | 42 (63.6) | 77 (56.6) |

| Progressive disease | 24 (34.3) | 20 (30.3) | 44 (32.3) | |

| – Suspected growing teratoma syndrome | 17 (24.3) | 9 (13.6) | 26 (19.1) | |

| Late relapse | 11 (15.7) | 9 (13.6) | 20 (14.7) | |

| Redo RPLND* | 2 (2.9) | 3 (4.5) | 5 (3.7) | |

| Modus of surgery, number (%) | Open | 69 (98.6) | 60 (90.9) | 129 (94.9) |

| Minimal invasive | 1 (1.4) | 6 (9.1) | 7 (5.1) | |

| Operative time (minutes), median (range) | 275 (140–740) | 310 (90–975) | 300 (90–975) | |

| Estimated intraoperative blood loss (ml), median (range) | 500 (30–21,500) | 500 (0–8000) | 500 (0–21,500) | |

| Patients with intraoperative blood transfusion, number (%) | 7 (10.0) | 6 (9.1) | 13 (9.6) | |

| Retroperitoneal histology, number (%) | Mature teratoma | 37 (52.9) | 33 (50.0) | 70 (51.5) |

| Fibrosis/necrosis | 21 (30.0) | 20 (30.3) | 41 (30.1) | |

| Vital GCT | 12 (17.1) | 13 (19.7) | 25 (18.4) | |

PC-RPLND: post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection; GCT: germ cell tumour

* Not including redo PC-RPLNDs of patients who underwent PC-RPLND twice in the study period

Open surgery was performed in 129/136 (94.9%) patients, with 1 robotic PC-RPLND in Bern and 4 laparoscopic and 2 robotic PC-RPLND in Zürich. No conversion to open surgery was required in those 7 patients. Overall, the median (range) operating time was 300 (90–975) minutes (275 minutes in Bern vs 310 minutes in Zürich, p = 0.014). In 26/136 (19.1%) patients, the intervention required ≥7 hours. The median (range) estimated intraoperative blood loss was 500 (0–21,500) ml. In 98/125 (78.4%) procedures, the blood loss was <1000 ml, resulting in 112/125 (89.6%) patients who did not need any red blood cell transfusions. Detailed information on the surgical variables is presented in supplementary tables 3 and 4.

Overall, 32/136 (23.5%) patients had a total of 52 major additional procedures during PC-RPLND (figure 1). Vascular resections of smaller vessels than the aorta or inferior vena cava (IVC) were not counted. More aortic resections and repairs were performed in Zürich than Bern (9/66 [13.6%] vs 2/70 [2.9%], p = 0.021). The rate of caval resection and repair was almost identical at the two centres (6/70 [8.6%] in Bern and 6/66 [9.1%] in Zurich). A nephrectomy was performed in 6/136 (4.4%) of patients.

Figure 1 Additional procedures during post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection by centre (IVC: inferior vena cava; GIT: gastrointestinal tract).

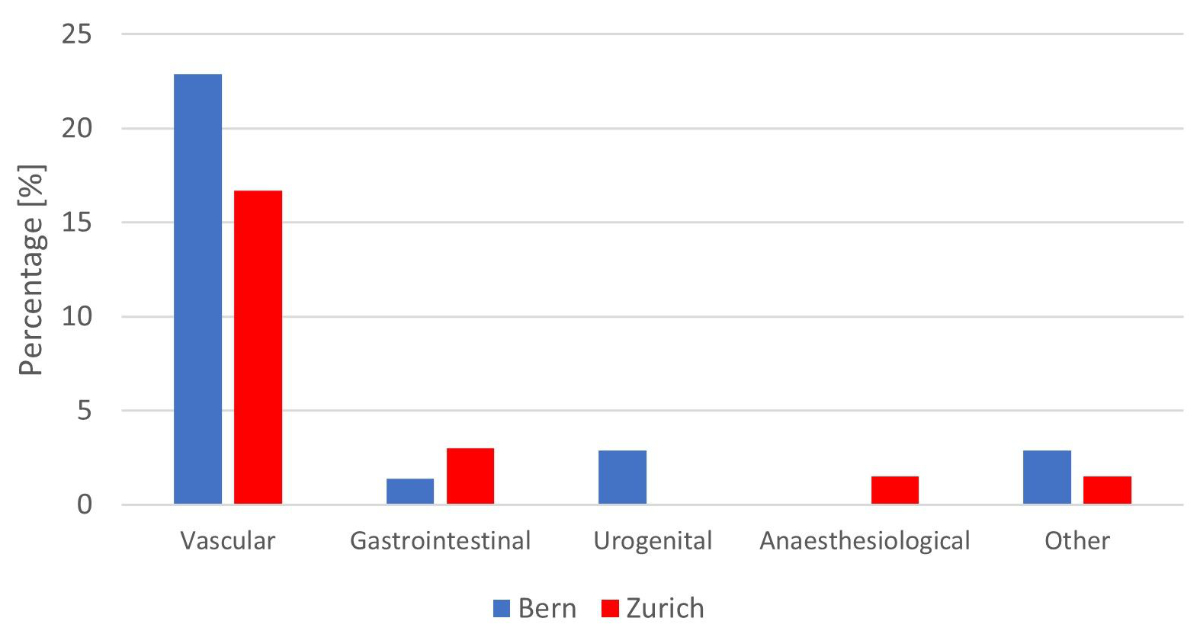

The most frequent intraoperative complication at both centres was a vascular injury (19.9% overall, 23.3% in Bern and 18.3% in Zürich; figure 2 and supplementary table 5). The most frequently injured vessel was the renal vein in 10/136 (7.4%) of patients, followed by the IVC in 7/136 (5.1%), and the aorta in 6/136 (4.4%). Gastrointestinal and urogenital injuries were rare, with overall rates of 2.3% and 1.6%, respectively. Overall, more intraoperative complications occurred in patients with a pre-operative retroperitoneal mass ≥50 mm (20/32 [62.5%] vs 31/93 [33.3%], p = 0.004) and those who underwent a bilateral template (27/49 [55.1%] vs 24/77 [31.2%], p = 0.008).

Figure 2 Intraoperative complications during post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection by centre.

The overall median (range) length of stay was 7 (2–60) days, with a median (range) of 1 (0–51) days in intermediate or intensive care. Overall, 9/136 (6.6%) patients were readmitted to the hospital within 90 days after PC-RPLND due to chylous ascites or lymphocele (n = 4), ileus (n = 3), sepsis (n = 1) and pain (n = 1; supplementary table 6).

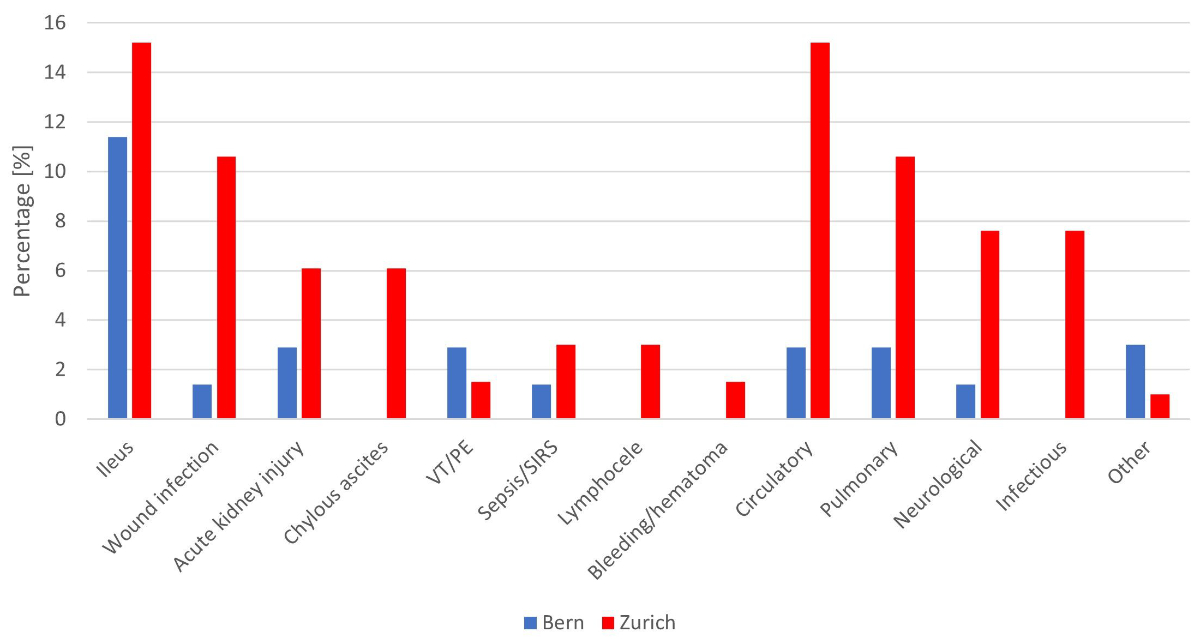

A total of 81 complications were reported in 42/136 (30.9%) patients (figure 3 and supplementary table 7). More patients had reported complications in Zürich than in Bern (28/66 [42.4%] vs 14/70 [20.0%], p = 0.005). However, 94/136 (69.1%) of all patients had no postoperative complications reported. The reported complications were classified as major (≥Clavien III) in 13/42 (31%) patients, the most common being a postoperative ileus.

Figure 3 Postoperative complications after post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection by centre (VT/PE: venous thromboembolism/pulmonary embolism; SIRS: systemic inflammatory response syndrome).

Three patients died of perioperative complications during their hospital stay, resulting in an overall mortality rate of 2.2%. One patient developed aspiration pneumonia and a central pulmonary embolism, one patient with wide resection of the aorta and inferior vena cava died from an infection of the vascular graft, and a third patient developed ventilator-associated pneumonia and fatal sepsis.

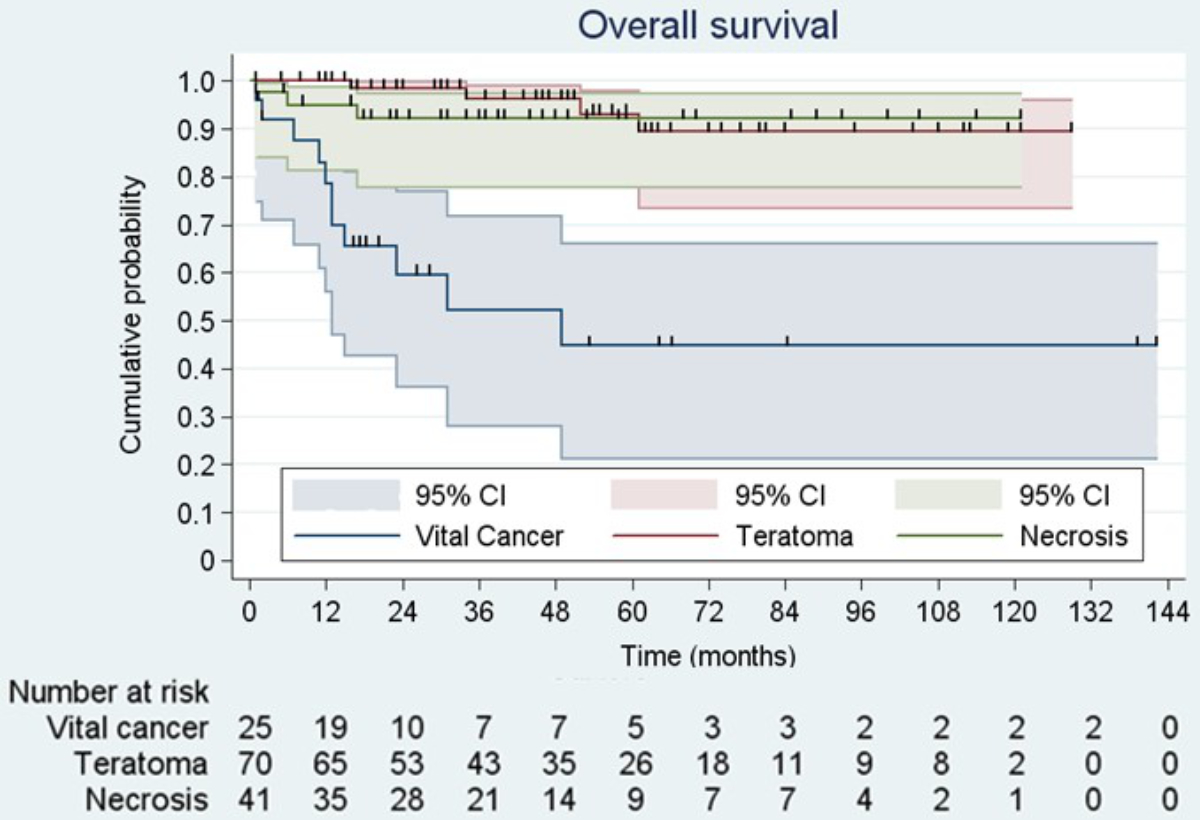

The histopathological report showed teratoma in 70 patients (51.5%), fibrosis or necrosis only in 41 (30.1%) patients, and viable cancer in 25 patients (18.4%; table 2), with no difference between the two centres. Teratoma was more frequently found in patients with a preoperative retroperitoneal mass ≥50 mm (25/33 [75.8%] vs 54/102 [52.9%], p = 0.021) and radiological progression of the mass prior to PC-RPLND (32/38 [84.2%] vs 48/98 [49.0%], p <0.001). Vital tumour occurred more frequently in patients with a preoperative retroperitoneal mass ≥50 mm (10/33 [30.3%] vs 15/102 [14.7%], p = 0.045) and elevated increasing serum tumour markers prior to RPLND (8/10 [80%] vs 17/126 [13.5%], p <0.001).

The median (range) follow-up was 37.2 (0.1–142.1) months, with no difference between Bern and Zürich. Until April 22nd 2022, 26 (19%) patients were lost to follow-up and censored at the time of last contact.

Relapses during follow-up occurred in 28/136 (20.6%) patients (see supplementary table 8); 14/136 (10.3%) had a retroperitoneal relapse (7 after bilateral template, 7 after unilateral template), of whom 12/14 (85.7%) were in the former surgical field (in-field relapse). Another 15/136 (11.0%) patients had a relapse outside the retroperitoneum, including the liver, thorax, lung or brain, or tumour marker progression only. Of relapsing patients, 13/28 (46.4%) died due to disease progression. The median (range) time to relapse was 5.8 (0.7–56.1) months, and 26/28 (92.9%) relapses occurred within 24 months after PC-RPLND.

The occurrence of relapse was associated with a preoperative retroperitoneal mass ≥50 mm (12/33 [36.4%] vs 16/102 [15.7%], p <0.011), PC-RPLND performed for a late relapse (10/20 [50.0%] vs 18/116 [15.5%], p = 0.001) and the occurrence of vital cancer in the resected specimen at PC-RPLND (14/25 [56.0%] vs 14/111 [12.6%], p <0.001).

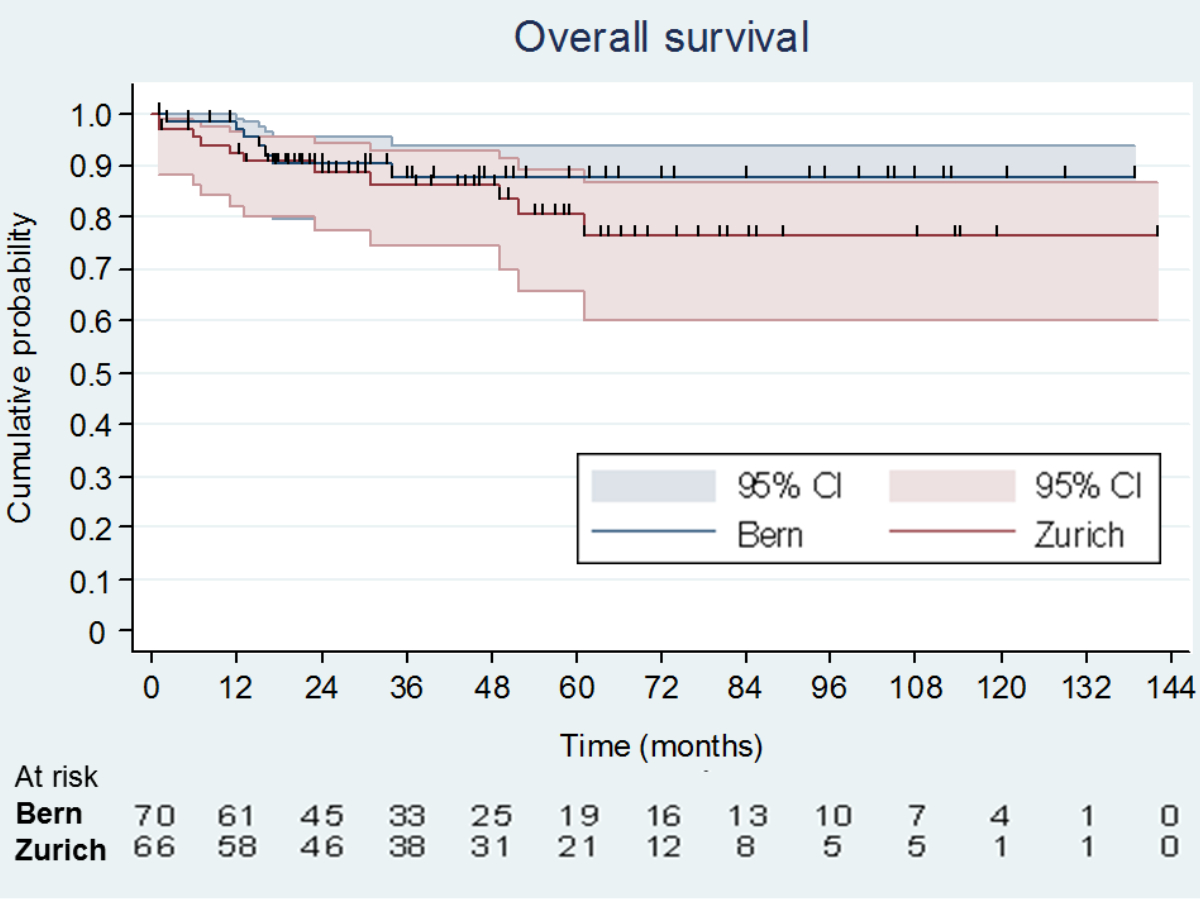

Overall survival and progression-free survival at 5 years were similar in Zürich and Bern (figure 4 and supplementary figure 1). Patients with progressive disease in the preoperative imaging or increasing elevated serum tumour markers before PC-RPLND had significantly inferior survival probabilities at 5 years compared to non-progressing patients (supplementary figures 2 to 5). The presence of teratoma in the resected specimens did not confer inferior survival probabilities compared to patients with necrosis or fibrosis, whereas patients with vital tumour had inferior progression-free and overall survival (figure 5 and supplementary figure 6). Patients who underwent RPLND for a late relapse also had significantly inferior progression-free and overall survival (supplementary figures 7 and 8).

Figure 4 Kaplan–Meier analysis of overall survival probabilities by centre. Bern overall survival at 5 years 88% (95% CI: 76–94%), Zürich overall survival at 5 years 77% (95% CI: 60–87%), p = 0.335 for difference.

Figure 5 Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival after stratification for histology in the resected specimen. Vital cancer overall survival at 5 years 45% (95% CI: 21–66%); teratoma overall survival at 5 years 90% (95% CI: 73–96%); necrosis overall survival at 5 years 93% (95% CI: 78–97%); p <0.001 for difference between teratoma or necrosis and vital cancer

Progression-free and overall survival were not statistically different in patients resected within 3 months after the end of chemotherapy compared to within 1 year among 74 patients with normal serum tumour markers and no radiological progression before surgery.

This is the first analysis reporting on perioperative morbidity and oncological outcomes of patients with germ cell tumours undergoing PC-RPLND at two high-volume centres in Switzerland. In accordance with published results, expert surgery contributed to high long-term progression-free and overall survival probabilities of 72% and 84% at 5 years, respectively. However, despite surgical expertise, a significant rate of around 30% perioperative complications at PC-RPLND and a mortality rate of 2% supports the centralisation of such procedures, as has been suggested previously [13, 16, 18].

Vascular injuries represent the largest group among intraoperative complications, in around 20% of patients. This is not surprising because lymph nodes in the retroperitoneum are in direct proximity to the major abdominal vessels, and residual nodal masses may invade local structures, including the aorta and vena cava. In addition, a possible severe desmoplastic reaction induced by chemotherapy can impair the meticulous dissection of the layers around the vessels during PC-RPLND [21]. Thus, when performing PC-RPLND, expertise and familiarity with the specific surgical techniques of this intervention are essential.

The complication rate was higher in patients with larger preoperative retroperitoneal masses >5 cm, which is in accordance with published data. Heidenreich et al. reported complication rates of up to 41.7% in a group of 25 patients with a median mass size of 186 mm [22]. All 25 patients in this series underwent additional procedures (vascular, skeletal, pancreaticoduodenal surgery). In the subgroup of patients who underwent additional procedures during PC-RPLND in our study cohort, the complication rate reached 56.3%.

Two systematic reviews have reported overall complication rates of 21.8% for PC-RPLND: 29% for unilateral and 52% for more extended bilateral template PC-RPLND, similar to our series [16, 23]. However, different definitions used by the various study groups, different grading of complications, and different accuracy in documenting the intra- and postoperative course may lead to variations in reporting of complications. This may have contributed to the observed differences in complication rates also at the two centres studied in our cohort [24].

Histopathological analysis of the resected specimen at PC-RPLND revealed vital cancer in 18.4% of patients, mature teratoma in 51.5%, and fibrosis or necrosis in 30.1%. Teratoma and viable cancer were more frequent in patients with large retroperitoneal masses before PC-RPLND and progression before PC-RPLND. Similar correlations have been identified by the German Testicular Cancer Study Group and others [25–29]. However, at present, no preoperative variable can be used safely to exclude patients with residual masses >1 cm from PC-RPLND.

Oncological outcomes at both institutions of the present cohort were similar and determined by preoperative risk factors and intraoperative histology. In contrast to teratoma or necrosis and fibrosis, vital cancer in the resected specimen was associated with significantly inferior survival probabilities, similar to patients with progressive disease before surgery and those undergoing PC-RPLND for late relapse. Therefore, according to guidelines, patients with residual masses >1 cm should be scheduled for PC-RPLND early and not later than 3 months after chemotherapy.

The quality of surgery and the meticulous dissection of the surgical template are of paramount importance for oncological outcomes but were difficult to measure in this retrospective analysis. Overall, 8.8% of patients experienced an in-field relapse. Enlarging the extent of resection would have potentially prevented a relapse in 2/14 patients who suffered abdominal relapses outside their initially chosen resection area (out-of-field-relapse).

A limitation of the present analysis is its retrospective nature. Particularly, adherence to published templates and the quality of surgery was difficult to assess retrospectively because we had to rely on written surgical reports, which did not always report all relevant information in a structured fashion. Furthermore, compared to published reports, patient numbers are small in Switzerland, making a more detailed comparison between the two centres difficult. In particular, the small sample size prevented a multivariable analysis, which would have been desirable to fully assess the contribution of individual variables impacting progression-free and overall survival. Follow-up data was incomplete in many patients, and 19.1% of patients had to be censored due to missing follow-up. Finally, we could not extract important quality-of-life data, such as retrograde ejaculation and long-term satisfaction with the procedure, which will be the subject of a prospective data collection.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated excellent oncological outcomes and acceptable rates of perioperative morbidity and mortality at two major urological centres in Switzerland, which were comparable to reports from major international centres.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

1. Siegel RL , Miller KD , Fuchs HE , Jemal A . Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 Jan;71(1):7–33. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21654

2. Bundesamt für Statistik / Nationale Krebsregistrierungsstelle. Krebs, Neuerkrankungen und Sterbefälle: Anzahl, Raten, Medianalter und Risiko pro Krebslokalisation. (2020).

3. de Wit R , Stoter G , Kaye SB , Sleijfer DT , Jones WG , ten Bokkel Huinink WW , et al. Importance of bleomycin in combination chemotherapy for good-prognosis testicular nonseminoma: a randomized study of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Genitourinary Tract Cancer Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol. 1997 May;15(5):1837–43. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1997.15.5.1837

4. Culine S , Kerbrat P , Kramar A , Théodore C , Chevreau C , Geoffrois L , et al.; Genito-Urinary Group of the French Federation of Cancer Center (GETUG T93BP) . Refining the optimal chemotherapy regimen for good-risk metastatic nonseminomatous germ-cell tumors: a randomized trial of the Genito-Urinary Group of the French Federation of Cancer Centers (GETUG T93BP). Ann Oncol. 2007 May;18(5):917–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdm062

5. Krege S , Beyer J , Souchon R , Albers P , Albrecht W , Algaba F , et al. European consensus conference on diagnosis and treatment of germ cell cancer: a report of the second meeting of the European Germ Cell Cancer Consensus Group (EGCCCG): part II. Eur Urol. 2008 Mar;53(3):497–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2007.12.025

6. Honecker F , Aparicio J , Berney D , Beyer J , Bokemeyer C , Cathomas R , et al. ESMO Consensus Conference on testicular germ cell cancer: diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018 Aug;29(8):1658–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy217

7. EAU Guidelines on Testicular Cancer. EAU Guidelines Office, Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2021.

8. C. T. Nguyen , A. J. Stephenson , Role of postchemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in advanced germ cell tumors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 25, 593-604, ix (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hoc.2011.03.002

9. Motzer RJ , Amsterdam A , Prieto V , Sheinfeld J , Murty VV , Mazumdar M , et al. Teratoma with malignant transformation: diverse malignant histologies arising in men with germ cell tumors. J Urol. 1998 Jan;159(1):133–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(01)64035-7

10. Oldenburg J , Alfsen GC , Waehre H , Fosså SD . Late recurrences of germ cell malignancies: a population-based experience over three decades. Br J Cancer. 2006 Mar;94(6):820–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603014

11. Tandstad T , Kollmannsberger CK , Roth BJ , Jeldres C , Gillessen S , Fizazi K , et al. Practice Makes Perfect: The Rest of the Story in Testicular Cancer as a Model Curable Neoplasm. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Nov;35(31):3525–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.73.4723

12. Mosharafa AA , Foster RS , Koch MO , Bihrle R , Donohue JP . Complications of post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for testis cancer. J Urol. 2004 May;171(5):1839–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000120141.89737.90

13. Subramanian VS , Nguyen CT , Stephenson AJ , Klein EA . Complications of open primary and post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for testicular cancer. Urol Oncol. 2010;28(5):504–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.10.026

14. Winter C , Raman JD , Sheinfeld J , Albers P . Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection after chemotherapy. BJU Int. 2009 Nov;104(9b 9 Pt B):1404–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08867.x

15. Heidenreich A , Albers P , Hartmann M , Kliesch S , Kohrmann KU , Krege S , et al.; German Testicular Cancer Study Group . Complications of primary nerve sparing retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the testis: experience of the German Testicular Cancer Study Group. J Urol. 2003 May;169(5):1710–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000060960.18092.54

16. Rosenvilde JJ , Pedersen GL , Bandak M , Lauritsen J , Kreiberg M , Wagner T , et al. Oncological outcome and complications of post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal surgery in non-seminomatous germ cell tumours - a systematic review. Acta Oncol. 2021 Jun;60(6):695–703. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2021.1905176

17. Wells H , Hayes MC , O’Brien T , Fowler S . Contemporary retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) for testis cancer in the UK - a national study. BJU Int. 2017 Jan;119(1):91–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.13569

18. Cary C , Masterson TA , Bihrle R , Foster RS . Contemporary trends in postchemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection: additional procedures and perioperative complications. Urol Oncol. 2015 Sep;33(9):389.e15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.07.013

19. Dindo D , Demartines N , Clavien PA . Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004 Aug;240(2):205–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae

20. Vather R , Trivedi S , Bissett I . Defining postoperative ileus: results of a systematic review and global survey. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013 May;17(5):962–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-013-2148-y

21. Macleod LC , Rajanahally S , Nayak JG , Parent BA , Ramos JD , Schade GR , et al. Characterizing the Morbidity of Postchemotherapy Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Dissection for Testis Cancer in a National Cohort of Privately Insured Patients. Urology. 2016 May;91:70–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2016.01.010

22. Heidenreich A , Haidl F , Paffenholz P , Pape C , Neumann U , Pfister D . Surgical management of complex residual masses following systemic chemotherapy for metastatic testicular germ cell tumours. Ann Oncol. 2017 Feb;28(2):362–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw605

23. Haarsma R , Blok JM , van Putten K , Meijer RP . Clinical outcome of post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in metastatic nonseminomatous germ cell tumour: A systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020 Jun;46(6):999–1005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2020.02.035

24. Cary C , Foster RS , Masterson TA . Complications of Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Dissection. Urol Clin North Am. 2019 Aug;46(3):429–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ucl.2019.04.012

25. Beck SD , Foster RS , Bihrle R , Ulbright T , Koch MO , Wahle GR , et al. Teratoma in the orchiectomy specimen and volume of metastasis are predictors of retroperitoneal teratoma in post-chemotherapy nonseminomatous testis cancer. J Urol. 2002 Oct;168(4 Pt 1):1402–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64458-8

26. Steyerberg EW , Vergouwe Y , Keizer HJ , Habbema JD , Group RS ; ReHiT Study Group . Residual mass histology in testicular cancer: development and validation of a clinical prediction rule. Stat Med. 2001 Dec;20(24):3847–59. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.915

27. Carver BS , Bianco FJ Jr , Shayegan B , Vickers A , Motzer RJ , Bosl GJ , et al. Predicting teratoma in the retroperitoneum in men undergoing post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection. J Urol. 2006 Jul;176(1):100–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00508-8

28. Albers P , Weissbach L , Krege S , Kliesch S , Hartmann M , Heidenreich A , et al.; German Testicular Cancer Study Group . Prediction of necrosis after chemotherapy of advanced germ cell tumors: results of a prospective multicenter trial of the German Testicular Cancer Study Group. J Urol. 2004 May;171(5):1835–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000119121.36427.09

29. Fosså SD , Qvist H , Stenwig AE , Lien HH , Ous S , Giercksky KE . Is postchemotherapy retroperitoneal surgery necessary in patients with nonseminomatous testicular cancer and minimal residual tumor masses? J Clin Oncol. 1992 Apr;10(4):569–73. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1992.10.4.569

The appendix is available in the pdf version of the article.