Role distribution and collaboration between specialists and rural general practitioners in long-term chronic care: a qualitative study in Switzerland

DOI: https://doi.org/10.57187/smw.2022.40015

Rebecca

Tomaschekab, Armin

Gemperliabc, Michael

Baumbergerd, Isabelle

Debeckere, Christoph

Merloa, Anke

Scheel-Sailerbc, Christian

Studera, Stefan

Essiga

aCenter for Primary and Community Care, University of Lucerne, Switzerland

bDepartment of Health Sciences and Medicine, University of Lucerne, Switzerland

cSwiss Paraplegic Research, Nottwil, Switzerland

dSwiss Paraplegic Centre, Nottwil, Switzerland

eREHAB Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Summary

INTRODUCTION: This study explores general practitioners’ (GPs’) and medical specialists’ perceptions of role distribution and collaboration in the care of patients with chronic conditions, exemplified by spinal cord injury.

METHODS: Semi-structured interviews with GPs and medical specialists caring for individuals with spinal cord injury in Switzerland. The physicians we interviewed were recruited as part of an intervention study. We used a hybrid framework of inductive and deductive coding to analyse the qualitative data.

RESULTS: Six GPs and six medical specialists agreed to be interviewed. GPs and specialists perceived the role of specialists similarly, namely as an expert and support role for GPs in the case of specialised questions. Specialists’ expectations of GP services and what GPs provide differed. Specialists saw the GPs’ role as complementary to their own responsibilities, namely as the first contact for patients and gatekeepers to specialised services. GPs saw themselves as care managers and guides with a holistic view of patients, connecting several healthcare professionals. GPs were looking for relations and recognition by getting to know specialists better. Specialists viewed collaboration as somewhat distant and focused on processes and patient pathways. Challenges in collaboration were related to unclear roles and responsibilities in patient care.

CONCLUSION: The expectations for role distribution and responsibilities differ among physicians. Different goals of GPs and specialists for collaboration may jeopardise shared care models. The role distribution should be aligned according to patients’ holistic needs to improve collaboration and provide appropriate patient care.

Introduction

Collaboration between healthcare professionals (HCPs) is important for the effective and safe delivery of care. HCPs working together can tackle the burden of chronic diseases. Furthermore, each professional can add relevant skills and knowledge to assess patients [1]. In particular, good collaboration between specialists and general practitioners (GPs) is essential for meeting patients’ needs. GPs see persons with chronic health conditions often as the first point of contact for providing medical and psychosocial care, but patients also require specialised services and referrals. A lack of collaboration and coordination between primary and secondary care often leaves the patient as the only person to have an overview of services provided [2]. Factors that influence the quality of coordination and collaboration are often organisational, such as information exchange and communication between professionals. Especially in Switzerland, implementation of interprofessional and interdisciplinary information exchange technologies seems to be difficult [3]. Personal factors are related to individuals knowledge and skills and having a collaborative attitude [1, 4]. This list is not all-inclusive but highlights the complexity of collaborative care. Frequently, complex chronic conditions further complicate care. Patients might present a challenging interplay of health conditions and existing treatment approaches that need to be considered [2]. Therefore, patients crossing the primary-secondary care interface especially benefit from enhanced information exchange and simplified communication enabled by collaborative care between physicians [5]. Evidence for certain chronic conditions showed that collaborative care is superior to usual care [6].

Individuals with spinal cord injury are an excellent example of persons with chronic conditions requiring life-long primary and secondary care. Along with the functional impairments of the condition itself, secondary conditions such as spasticity, chronic pain, sexual dysfunction, bowel and bladder problems, and pressure injuries are often untreated [7]. Owing to medical advances, these individuals’ life expectancy has increased and in Switzerland their average age is 58 years [8, 9]. Especially in rural areas where specialist services are unavailable, individuals with spinal cord injury are more likely to substitute them with GP services [10]. However, GPs might lack knowledge specific to spinal cord injuries [11]. In line with research suggesting the introduction of small outpatient clinics or outreach services to meet healthcare needs [10], selected rural GPs might fill this gap. The GPs providing additional services do not need to become experts in spinal cord injury because this patient population is small [12]. However, GPs need to be well connected to specialised physicians and other HCPs who are more experienced in order to meet specific needs. Research shows that most GPs are inexperienced in spinal cord injury but care for most of the secondary conditions of this patient population [13–15].

This qualitative study explored the perceptions of GPs and medical specialists willing to engage in care of patients with chronic spinal cord injury on role distribution and collaboration. The study aimed to contribute to a better understanding of (1) the role distribution, (2) facilitators and barriers to collaboration and (3) potential improvement possibilities. The questions are applicable in care for patients with chronic conditions in general.

Methods

Setting and participants

We followed the 32-item COREQ checklist as a reporting guideline [16] which can be found in appendix table 1. Ethics approval was sought and awarded by the Ethics Committee of Northwest and Central Switzerland (EKNZ; # 2019-01527-2). We conducted individual semi-structured interviews with rural GPs and medical specialists for spinal cord injury participating in the SCI-CO intervention study. The study protocol for the intervention may be consulted for details [17]. In short, 120 GPs were asked to participate in the intervention study of whom we expected 10 to agree to participate. We expected 16 specialists employed in the four specialised centres to participate.

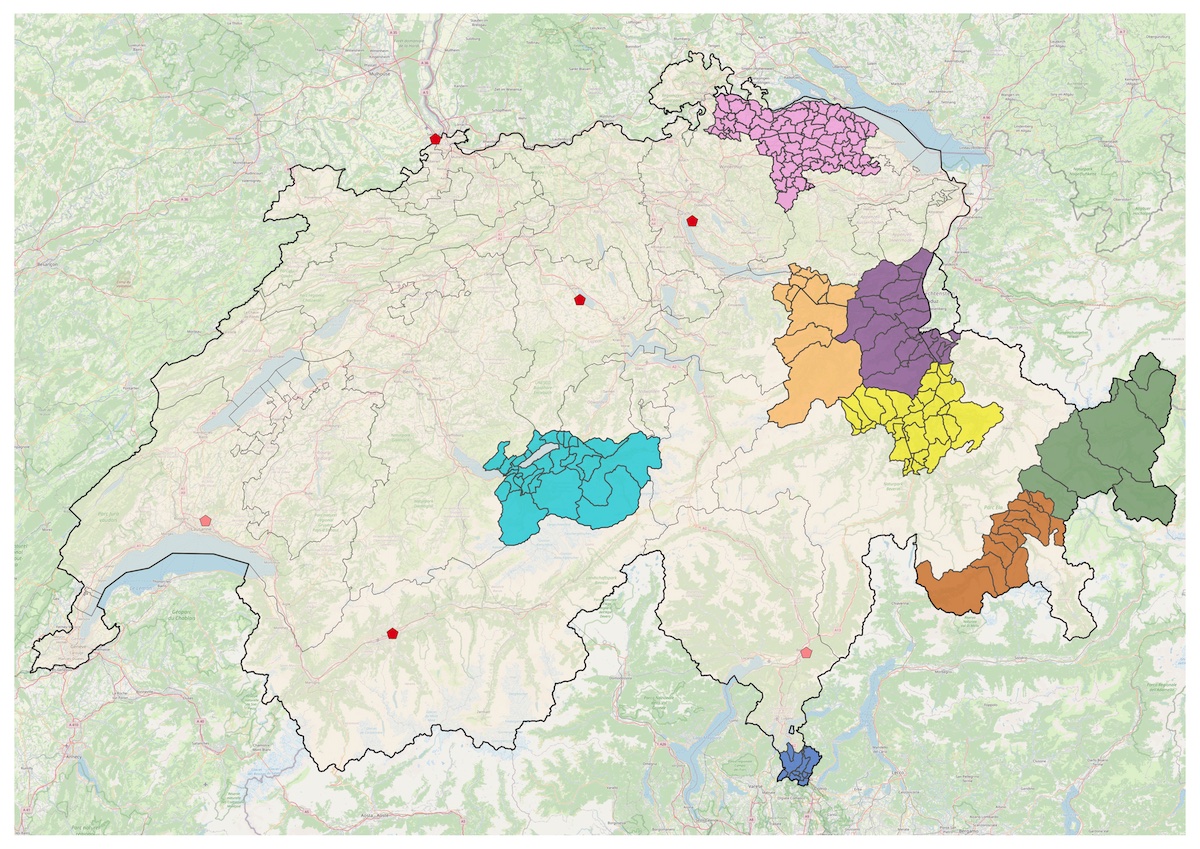

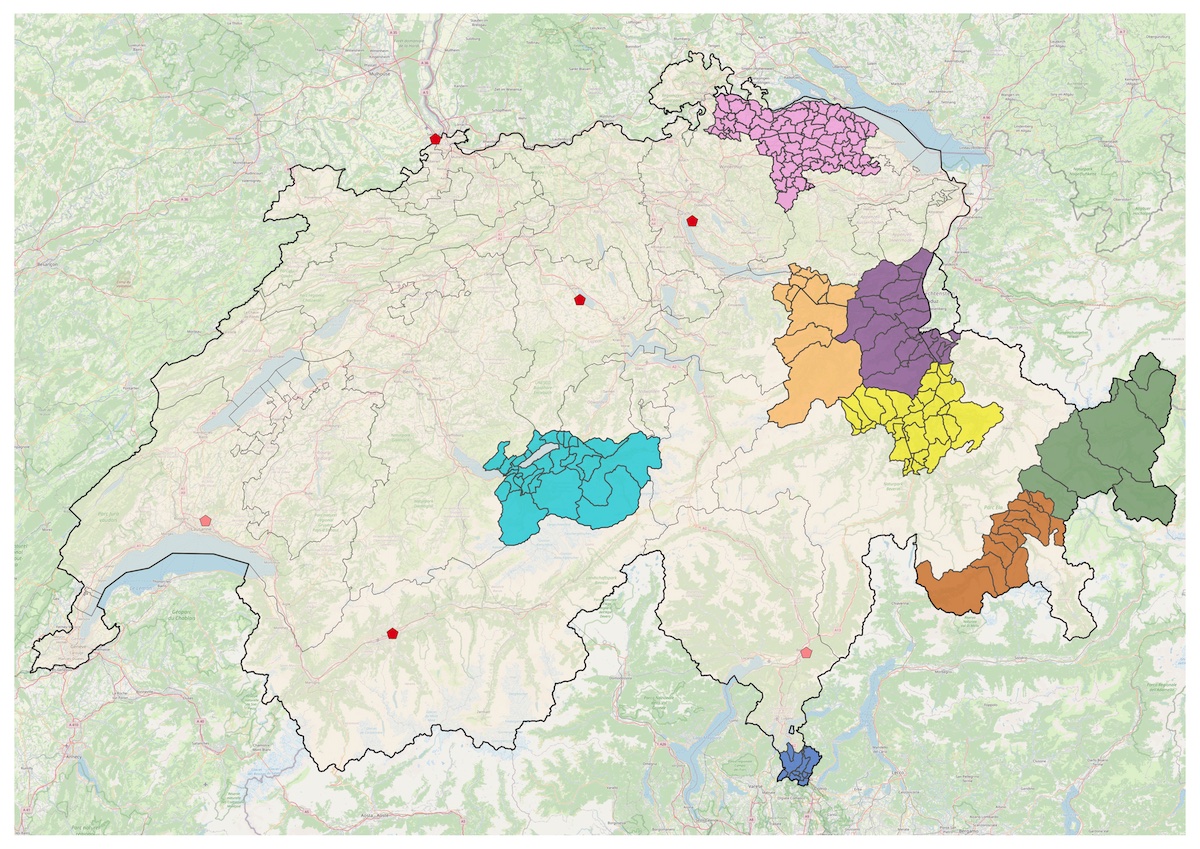

Figure 1 shows where the participating physicians were located. Eight GPs, who agreed to participate in the intervention, are shown with their catchment areas. All GP practices were located in rural, primarily alpine areas of Switzerland, with a minimum 60-minute journey by car to a specialised centre for spinal cord injury [18]. Six red pentagons on the map mark specialised centres for spinal cord injury care that offer inpatient and outpatient services. The 13 specialists who agreed to participate in the intervention study are employed in these centres.

Figure 1 Location of GP practices and specialised service providers for spinal cord injury in Switzerland. Colourful areas depict the participating practices’ catchment areas. Four red pentagons mark the specialised centres for spinal cord injury in Switzerland. Two faded red pentagons mark external ambulatory service units, where patients can receive outpatient services (e.g., annual check-ups) from specialists traveling regularly to these locations. Map data from OpenStreetMap.

Data collection

Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with an interview guide to explore experiences, perceptions, and opinions. As a framework, we followed the approach of Fereday, who developed an analysis based on “descriptive and interpretive theory of social action that explores subjective experience within the taken-for-granted, ‘common sense’ world of the daily life” [19]. The guide’s content was informed by other qualitative studies exploring collaboration between HCPs. Questions were taken from the studies’ questionnaires and adapted to our context. Our interview guide with its sources can be found in table 1.

Table 1Interview guide with templates from literature.

| Topics |

Templates from literature |

Study aim |

| 1. Role distribution of GP and specialist |

a. Description of role distributions |

[36–39] |

1 |

| b. Development of role distribution |

| c. Referral and counter-referral |

| d. Differences in role distribution for spinal cord injury care |

| 2. Perceptions of patients and other HCPs on role distribution |

[36, 39] |

Dropped from analysis |

| 3. Collaboration |

a. Positive and negative experiences for both general and spinal cord injury care |

[33] |

2 |

| b. Facilitators and barriers to collaboration |

| 4. Communication |

a. Communication channels |

[33, 40] |

2 |

| b. Information exchange |

| 5. Suggestions for improvement |

a. for role distribution |

[33, 36, 39, 41] |

3 |

| b. for collaboration |

| c. for spinal cord injury care specifically |

One researcher contacted the physicians by e-mail or telephone to inform them about the study’s aim and conducted the individual interviews. The interviews were conducted between 21 April 2020 and 3 May 2021. A doctoral student trained in qualitative research (RT) conducted the interviews in person and via video chat in German. The interview length ranged from 20 minutes to 60 minutes, with an average length of 37 minutes. At the beginning of the interview, the researcher informed participants about the study’s objective, the aim for recording the interview, and the measures taken to ensure confidentiality of the data. Participants gave verbal consent for participation and recording of the interviews. The interviews were transcribed verbatim from the audio recording.

Data analysis

The interviews with GPs and specialists were analysed successively. First, all transcripts were read in order to become familiar with the data. Second, a hybrid method of inductive and deductive coding, according to Fereday [19], was applied. MAXQDA software supported the organisation of data and coding. The researcher who conducted the interviews coded the transcripts and discussed them in meetings with the research team. The team constantly reviewed transcripts to ensure that the identified code sets were applied to all transcripts. Relevant codes for each physician group were then summarised, and sub-themes were formulated. Overarching themes similar to the structure of the interview guide were used to combine sub-themes of GPs and specialists. We chose to present the results in this manner to highlight any differences or similarities between the two groups in keeping with the purpose of this study. The quotes identified as the most meaningful by the researchers were translated into English.

Physicians brought up sub-themes that were not directly related to the structure of the interview guide. Examples of these sub-themes include: practising in rural areas and the impact on care; political and system-related factors that have influenced the development of primary care in Switzerland; and the impact of media and the internet on patient behaviour and preferences for care. The last two sub-themes did not provide information to answer our research questions. Thus, the data on these sub-themes were dropped.

Results

Participants

Six GPs, 75% of GPs participating in the intervention study and six medical specialists, 81% of specialists participating in the intervention study agreed to be interviewed. Time constraints were the reason for physicians to decline an interview. Two GPs and one medical specialist were female. Four of the six interviewed GPs were new to the topic of spinal cord injury and answered the questions based on their experiences with chronic conditions. The specialists had a background in general internal medicine with specialisations such as urology or physical medicine and rehabilitation. They had extensive experience in care for spinal cord injury and worked in specialised centres. More characteristics can be found in table 2. The results are structured according to the overarching themes. A detailed overview of overarching themes and sub-themes can be found in appendix table 2 and appendix table 3.

Table 2Physicians’ characteristics.

|

GPs (n = 6) |

Specialists (n = 6) |

| Age in years – mean (SD) |

52 (7.9) |

50 (9.9) |

| Female – n (%) |

2 (33.3) |

1 (17) |

| Issuing country of academic title, Switzerland – n (%) |

4 (67) |

2 (33) |

| Title – n (%) |

MD and university lecturer |

0 (0) |

1 (17) |

| MD |

6 (100) |

4 (67) |

| Practising physician |

0 (0) |

1 (17) |

| Medical focus – n (%) |

General internal medicine |

6 (100) |

4 (67) |

| Physical medicine and rehabilitation |

0 (0) |

3 (50) |

| Urology |

0 (0) |

1 (17) |

| Others |

2 (33) |

4 (67) |

| Self-employed – n (%) |

3 (50) |

– |

| Current position in specialised centre – n (%) |

Chief physician |

– |

2 (33) |

| Senior physician |

– |

2 (33) |

| Hospital physician |

– |

2 (33) |

| Years working at current place of work – mean (SD) |

7 (5.5) |

7 (9.7) |

| Percentage employed at current place of work – mean (SD) |

70 (35.2) |

93 (16.3) |

| Patients caring for in one month – mean (SD) |

500 (187.1) |

28 (7.5) |

| Using electronic medical records – n (%) |

6 (100) |

6 (100) |

| Distance GP practice to next hospital in km – mean (SD) |

16 (12.3) |

– |

| Number of HCPs in GP practice – median (min-max) |

Physicians |

2 (2–5) |

– |

| Medical practice assistants |

5 (4–14) |

– |

| Medical practice coordinators |

1 (1–1) |

– |

| Nurse |

1 (2–10) |

– |

| Physiotherapist |

3 (1–3) |

– |

| Occupational therapist |

1 (3–4) |

– |

| Speech therapist |

0 (0–1) |

– |

| Dietician |

0 (0–1) |

– |

| Psychologist |

0 (0–3) |

– |

Different perceptions on GPs’ roles and responsibilities

GPs perceived their role as holistic managers and guides. They considered this role important for their patients because “almost nobody knows what they need and where to get it in today’s medical jungle” (GP2). Accordingly, they had an overview of the social situation, comorbidities and medications, requiring broad medical knowledge. Due to this managerial role, most GPs were responsible for documenting information and sharing it with other HCPs. Additionally, GPs reported knowing patients’ expectations and their preferences for care. This knowledge seemed critical for them to fulfill their role as gatekeepers to specialised care. Accordingly, GPs used their holistic patient view and broad medical knowledge to decide whether to refer a patient to a specialist. Several GPs highlighted recognising the boundaries of their knowledge and the moments when a referral is necessary. “I perceive the GP to be the hub of everything. Because the specialist is usually only interested in the specialized field, I am the one who looks at everything. Moreover, in the end, I am the one with the most information and who coordinates. If there are others, I am not the one to command, but I know where threads come together and who does what” (GP5).

Specialists perceived the GPs role as the first contact person for patients with chronic spinal cord injury. As illustrated by this quote, many specialists reported that individuals with spinal cord injury value and trust their GP. “They [the patients] have a great relationship to the GP. Especially in rural areas, there still is the family doctor, and that is great” (SP3). Concerning the GPs responsibilities, this specialist explained that GPs should be contacted for general care. “You need to distinguish between ‘Is this issue directly related to the spinal cord injury?’ With these issues, GPs are overtaxed because they don’t have the specialised knowledge. And then I think there are health problems where the spinal cord injury doesn’t play a role” (SP3). This specialist perceived GPs to be gatekeepers “[…] to avoid having people call with trivial problems on a Sunday” (SP4). Furthermore, specialists wanted GPs to document patient information and to keep track of patients’ medication in particular. They described that it is helpful to receive a medication list before consulting a patient. Additionally, specialists explained that GPs should prescribe medication or therapeutic interventions such as physiotherapy and monitor patients’ progress. Some specialists illustrated arrangements with GPs in which expensive medication was prescribed by the specialist to not “weigh down” (SP5) the GPs’ budget.

Specialists as experts and support for GPs

All specialists perform regular check-ups for persons with a spinal cord injury in the specialised centres and are considered to be an information source of support for GPs. The specialists should be contacted for questions related to the spinal cord injury, for which they provide additional information or advice. “You are identified as the qualified person, who has the solution, but it is still within the competencies of the GP. And the only thing missing is the quick input on spinal cord injury” (SP3). On the contrary, the specialists’ responsibilities seemed to differ. Whereas most specialists reported caring for patients within the range of their medical discipline, this specialist specified that the role is more like a specialised GP. “I think it’s about being a GP for the specific population to care for special issues that the GPs don’t know anything about” (SP3).

All GPs explained that the decision to refer the patient to a specialist is related to their own skills and knowledge. This GP summarised the relation of the two roles as follows “There are aspects where I feel very confident, where I go very far with care and when I realise I reached my limit, […] I quickly seek the specialist’s advice” (GP6). GPs expected specialists they collaborate with to provide or confirm information. “It’s always good if you are confirmed in your approach, or if you are confirmed in your uncertainty […]” (GP4). Additionally, this GP explained that it is important to be informed about the patient after a referral. “If you think about the definition of a referral, then it is actually not only to support the patient but also to support the one who initiates the consultation, namely us, the GPs. This means that not only the patient and the specialist should continue working together, but the GP must also remain in the boat” (GP2).

Knowing each other as facilitator for collaboration

Both GPs and specialists concluded that patients could be best cared for collaboratively. Collaboration was essential in a highly complex situation requiring multidisciplinary or interprofessional care. “I think, the longer the patient is chronically ill or the higher the level of suffering, the better communication between physicians and therapists must be” (GP6). In addition, patients’ satisfaction with services and their care seemed to be a crucial aspect of physicians’ collaboration. As this GP explained, perceived satisfaction resulted from the physicians’ shared or agreed-upon care goals. “One can tell that the patient is satisfied because he/she sees that GP and specialist pull in the same direction” (GP4).

Physicians reported that knowing each other personally was the leading facilitator for good collaboration. Building a relationship led to an awareness of each other’s competencies, skills, and preferences. Therefore, knowing each other was a crucial component in allocating roles and tasks, as explained by this specialist. “I think it is more like a togetherness. However, it is not easy, if you don’t know somebody, to realise how much the colleague wants to do themselves and how much they want us to do. Moreover, I think this is an arrangement. It is difficult initially, but if it is sorted out, it is clear… everybody has a role, and it works” (SP5). Furthermore, GPs and specialists reported that knowing each other enriched communication, made communication easier, enabled discussions on an equal basis and enhanced cooperative behavior. “As a GP, this is the most important requirement to know that you have colleagues, with whom collaboration works, information exchange works and you do not dread to tell them ‘Hey, you are wrong and I see it totally differently’. And this needs to work cooperatively and without too much effort” (GP2).

Different communication styles and preferences

GPs and specialists used communication and chose the communication channel differently. While specialists saw it as necessary for appropriate patient care, GPs mentioned personal benefits from a direct exchange with specialists. This specialist elaborated what is valued in communication with the GP, namely the urgency and content of information. “It depends on how urgent the information is. If it truly is something that needs to happen the next day, we have to talk to each other; you have to call. But if it is not important, a letter is sufficient if one can do it within the next two or three weeks. […] A telephone call is a last resort” (SP2). It was valuable for GPs to receive a timely update from the specialist as part of the referral process, as well. This GP relied on medical reports and emphasised that they must be precise in providing services and recommendations for the next steps. “I don’t think there are any standards. I believe everybody does it as they think it is right, and one can feel if it fits for yourself or not. For example, I worked with two cardiologists. I always knew that one formulated rather vague statements, and the other gave exact and concise statements. And then you rather want to work with the one giving precise statements instead of the one who hides behind general propositions” (GP6).

Some GPs described direct communication (e.g., via telephone) as an important information exchange and discussion platform for which it is worth taking time and resources. This GP illustrated how specialists’ phone calls are incorporated into daily practice. “We have the order in the practice that specialists’ phone calls will always be put through. Even if I’m in a patient consultation, I just quickly go outside to my computer, I am updated, and I enter the information. Alternatively, the psychiatrist calls ‘I have seen this patient, and it doesn’t look too good.’ And then you might have a short exchange. Or you discuss medication changes if you want to prescribe a medication where the specialist knows a better alternative. This way you simultaneously learn something” (GP1). Whereas GPs wanted to learn from a direct exchange, this specialist described it as a tool to “align” GPs with their expectations or suggestions for the patients’ care plan. “I call [the GP] and explain why we did what we did, even if it was against the expectations, to ensure that the procedure is not stopped or changed in primary care. Therefore, it is great to contact the GPs and explain why something has to be done this way” (SP4).

Unclear role distributions and uncooperative behaviour as barriers to collaboration

Barriers to good collaboration described by physicians were related to challenges in the distribution of responsibilities and past collaborative experiences. Specialists explained that appreciation of a clear division of roles is needed to ensure that patients’ needs were met. Accordingly, the main barrier to collaborating was uncertainty about who would take on tasks and responsibilities. Two relevant barriers to collaboration for GPs were lack of information sharing and lack of counter-referrals by specialists. GPs reported that they value precise and timely information on the patients’ situation after a referral.

On the one hand, this included information on the services provided, their results, and specific suggestions. On the other hand, GPs expected a short update whenever the specialist referred the patient to another specialist. Without this update, this GP experienced losing the patient. “If a specialist refers to another specialist, and another specialist… and by the second specialist, the GP is no longer listed on the medical record and receives no information” (GP2).

Most GPs reported that past collaborative experiences influenced patient care. In particular, referring patients to a specialist again depended on previous experiences. If GPs lacked information or specialists did not counter-refer patients, GPs were unlikely to refer more patients to that specialist. “And we can say: All right, there are other competitors in neurology, whom we can refer our patients to and where it works better” (GP1). Multiple GPs reported experiences with specialists who did not counter-refer the patients. GPs hypothesised that the reasons might be selfish and pecuniary specialists, or specialists’ thoughts that the GP was not able to care for the patient. Regardless of the reasons, this GP described the consequences of this experience. “If that occurs, one talks to GP colleagues and these [specialists] will no longer get referrals. They are on their own with the patients they attracted for themselves” (GP1).

Rural practice locations influence collaboration and patient care

Although this sub-theme was not part of the questionnaire, both physician groups raised it. It is about practicing in rural areas of Switzerland, which seemed to have particular implications for care provision and collaboration. Firstly, one implication concerned the population’s perception of the GP. According to the GPs, patients from urban areas can seek second opinions easily and thus behave differently towards physicians. One GP explained that people from rural areas no longer have the “faith in the white coat any more, as it was 50 years ago” (GP2), but still value the GPs opinion, unlike city dwellers. As mentioned and confirmed before, specialists shared their patients’ experiences thinking highly of their GP. Secondly, some GPs and specialists mentioned that anonymity in a city contributes to uncooperative and competitive behaviour among HCPs.

In contrast, this GP illustrates the benefits of collaboration and patient care in rural primary care practice. “I think I am in quite a luxurious position. […] I know the whole medical offer throughout the whole canton. Moreover, many of the colleagues I know personally, and this is a totally luxurious situation regarding collaboration. The same goes for hospitals. Because we have a relatively small hospital, where physicians are practising long-term, and do not change every two years” (GP2). Thirdly, one specialist related the choice of communication channels to the degree of urbanity. This specialist observed that HCPs used the telephone more than in the urban hospital where the specialist previously worked.

Enhancing communication and continuing medical education as improvement strategies

Both GPs and specialists had ideas about improving collaboration and patient care. Specialists acknowledged that more direct communication with GPs would be beneficial, as this specialist explained. “Maybe we have to establish this from our side, that we call [the GP] a month after [discharge] and ask how it is going. […] It is quite common that we do not hear from the patients until the check-up three months after discharge, which is the first visit in the ambulatory unit. And maybe by then, it is already too late” (SP1). However, this specialist was not optimistic about establishing regular telephone communication with GPs. “Of course, one wishes an intensive contact, to get to know each other, but this is always a question of own resources, and the GPs’ resources” (SP6).

Specialists wanted the GPs to become more knowledgeable and suggested continuing medical education events. They highlighted that GPs should be aware of particular treatment approaches that, although evidence-based or proven successful in other patient populations, were counterproductive or even harmful in individuals with spinal cord injury. On the other hand, other aspects of care for individuals with spinal cord injury were no different from those of other patient groups. According to this specialist, persons with “a spinal cord injury have high blood pressure; they have diabetes, they are obese. All these widespread diseases occur in individuals with spinal cord injury. And these are traditional topics that are monitored by the GP” (SP2). While specialists wanted GPs to gain more medical knowledge, GPs also saw benefits in medical education events, namely getting to know each other at education events and establishing a network with long-term partners. This network was the basis of forming informal communication channels or new care models. In the case of this GP, even the possibility of work shadowing is considered. “If it is concerning highly specialised services, that I have never done before, I would like to say ‘I will come and do a work shadowing with you, to know how this works’” (GP3). Topics for medical education listed by the GPs were related to prevalent secondary conditions such as pressure injuries, bladder and bowel management, but also related to assistive devices such as wheelchair cushions.

Discussion

Summary of findings

This qualitative study explored the perceptions of specialists and rural GPs on role distribution and collaboration in the care of patients with chronic diseases in Switzerland. The role of the specialist was perceived similarly by GPs and specialists as an expert and support for GPs in specialised questions. There was a difference between specialists’ expectations of GP services and what is provided by GPs. Specialists saw the GPs’ role as complementary to their own responsibilities, namely as the first contact for patients and gatekeeper to specialised services. GPs saw themselves as care managers and guides with a holistic view of patients, connecting several HCPs. GPs were likely to search for relations between professionals and recognition by getting to know specialists better. Specialists viewed collaboration as somewhat distant and focused on processes and patient pathways. Challenges in collaboration were related to unclear roles and responsibilities in patient care.

Interpretation and comparison with existing literature

The roles and responsibilities of specialists we explored were similar to those described in other research. GPs in the study of Diamantidis and colleagues mentioned specialists’ confirmation of appropriate evaluation, additional evaluation and testing, and medication regimen advice as motivations for participating in collaborative care [20]. Furthermore, Forrest suggested categorisation of roles and responsibilities of specialists [21]. On the one hand, cognitive consultants provide advice to reduce clinical uncertainty. On the other hand, procedural consultants perform a technical or diagnostic procedure service. In contrast, the third type of specialist, co-managers, was much more involved in ongoing care and performed care management tasks. Our findings support the expected and self-perceived role of specialists to be consultants. The primary care physicians we interviewed did not explicitly distinguish between cognitive and procedural consultants but described the respective responsibilities as mentioned by Forrest. GPs rated timely communication with the GP as a crucial responsibility in Forrest’s and in our study [21]. These remarks underline the GPs’ role as system-wide care managers, gathering and sharing information with appropriate professionals and institutions.

We identified different perceptions among GPs and specialists for the role of the GP. The different perceptions confirmed that HCPs require organisational efforts to discuss their roles and instead take over responsibilities based on patients’ needs and the necessary professional skills to fulfil them [23]. As patients’ needs differ, role distributions and responsibilities might change and therefore different forms of interprofessional cooperation are conceivable [24]. However, to successfully adapt collaboration, HCPs might benefit from clarified role distributions and realistic expectations. As an example, Sampson et al. observed unrealistic expectations of service provision, and it caused frustration in patients and physicians simultaneously [5]. The differences in role perception could relate to power struggles as described by the emancipatory framework [25] and professional territoriality as observed in Swedish research [22]. Especially in situations where specialists feared that GPs expand their role, they defined a professional territory to secure their own role and status [22]. Additionally, the perspectives of the GPs we interviewed reinforced some observations made in other research on the power struggles between GPs and specialists. The specialists in our interviews were distant regarding collaboration but did not openly express dislike of GPs.

In comparison, specialists in a Dutch qualitative study stated that they could not learn anything from GPs, nor did they see them as equals in their working relationship [26]. The GPs we interviewed seemed to have had bad experiences but described measures to counteract uncooperative behaviour. Another explanation for the unclear role distribution among physicians in our study could be that spinal cord injury care is not a common health condition [12]. The GPs we interviewed were not highly experienced in collaboration specific to this condition. Unlike other health conditions, persons newly experiencing a spinal cord injury consult specialists first. Usually, GPs are informed about the injury after initial rehabilitation is completed and the patient is transitioning to the community. Therefore, the specialists for spinal cord injury take on a significant role [15].

In this study, physicians suggested organising shared continuing medical education events as a strategy to improve collaboration. While GPs wanted to get to know specialists at those events and form a relationship with them, specialists suggested education for GPs to improve their medical knowledge. In a study to initiate GP-specialist collaboration, the intervention was medical education, which improved satisfaction with communication and self-reported confidence and clinical practice [27, 28]. Additionally, quality circles for quality improvement in primary care have been shown to be an effective measure and seem to be widely accepted in Switzerland [29, 30]. These strategies are based on education and aim to improve the knowledge transfer between the two professions.

Further qualitative research observed physicians forming personal relationships at education events while exchanging information and experiences. The interviewed physicians acknowledged that getting to know each other and each other’s working environment would reduce unrealistic expectations about each other’s roles. Furthermore, a personal relationship was essential to building trust for the working relationship [5]. According to a typology by D’Amour and colleagues, a formalisation process supports physicians getting to know each other [1]. Formalisation can define core values and competencies and, therefore, a clear distribution of responsibilities [31]. This formalisation may be initiated at regular exchange meetings or educational events. Berendsen et al. supported this idea, as they found that GPs enjoyed working closely with specialists to increase their medical knowledge [32, 33]. The authors suggested education as a promising way to improve collaboration because medical specialists were willing to teach GPs and enjoyed making them enthusiastic about their work domain [26, 33].

We found indications that the rural GPs we interviewed are well-connected despite the rural location. They all established a network, particularly within their region, and have had few negative experiences in collaboration. This observation can be explained by other qualitative research showing that rural GPs had a greater appreciation of learning from specialists than their urban counterparts [5]. Furthermore, the specialists we interviewed illustrated that rural GPs are particularly valued and trusted by patients. Research has different approaches to explaining rural areas’ particular features, especially concerning the GP-patient relationship. Farmer argued that a long-term relationship is developed, simply because the patient is exposed to the same GP as there often is only one practice in rural areas [34]. The long-term connection leads to empathy and trust between physician and patient. Besides this long-term relationship, GP and patient are connected because they live close to each other and share a community. Knowing each other personally opens up additional opportunities for information exchange. Thus, the GP can receive personal information that might have been missed in consultations. Farmer explained that knowing personal or biographical information about the patient was associated with providing holistic care. As rural patients are more likely to face difficulties in accessing care, they especially value a continuous experience monitored by the GP, which was also proven to be true in the Swiss population [35]. Thus, a rural GP with a long-term connection to patients is likely to be trusted and appreciated.

Limitations

The physicians we interviewed were part of the SCI-CO intervention study and thus most probably more motivated than other physicians to improve collaboration. Furthermore, only a subset of physicians who are part of SCI-CO could be interviewed. Due to this selection and the small number of physicians, the generalisation of our findings is limited. However, we found that the results of the interviews were rich and insightful and that we were able to focus on them. Another limitation might be that spinal cord injury is a specific setting. Few GPs have experience in spinal cord injury care, and the patient population is small. Nonetheless, our findings are mostly applicable to general care for patients with chronic conditions, as individuals with spinal cord injury are very much concerned with general concepts of chronic conditions and their pitfalls. To add to our research, the perception of patients and relatives of the role distributions should be explored.

Implications

We believe that HCPs and researchers may learn from the concepts incorporated in delivering care for this complex patient population. Concepts of care delivery that are usually incorporated into spinal cord injury care include interprofessional and interdisciplinary care, shared decision-making and vertical integration of care. Multiple stakeholders want to incorporate these concepts into daily practice, but the implementation seems to be complicated. Spinal cord injury care might serve as a model to learn from.

The findings provide insights into the physicians’ motivation to collaborate. This might suggest that continuing medical education may be implemented to enhance collaboration. First, the GPs’ search for relationships can be met by getting to know each other at education events. Second, discussing patient pathways and processes should be part of patient case discussions. Third, a regular timeslot to communicate with each other must be provided. Furthermore, the roles of the GPs and specialists need to be addressed formally to ensure a clear and complementary distribution of tasks and responsibilities. The health system needs to reward healthcare professionals and enable them to establish collaboration. Appropriate information exchange technologies and resources for exchange need to be provided.

Conclusion

The expectations for role distribution and responsibilities differ among physicians. Different goals of GPs and specialists for collaboration may jeopardise shared care models. The role distribution should be aligned according to patients’ holistic needs to improve collaboration and provide appropriate patient care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the physicians for their time and thoughtful input. Furthermore, the authors thank Yvonne Kohler for her valuable contribution in visualizing the physicians’ locations in figure 1.

Rebecca Tomaschek, MA

Centre for Primary and Community Care

Department of Health Sciences and Medicine

University of Lucerne

Frohburgstrasse 2

CH-6002 Lucerne

rebecca.tomaschek[at]unilu.ch

References

1. D’Amour D, Goulet L, Labadie JF, Martín-Rodriguez LS, Pineault R. A model and typology of collaboration between professionals in healthcare organizations. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008 Sep;8(1):188. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-8-188

2. Koch G, Wakefield BJ, Wakefield DS. Barriers and facilitators to managing multiple chronic conditions: a systematic literature review. West J Nurs Res. 2015 Apr;37(4):498–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945914549058

3. Tandjung R, Rosemann T, Badertscher N. Gaps in continuity of care at the interface between primary care and specialized care: general practitioners’ experiences and expectations. Int J Gen Med. 2011;4:773–8. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S25338

4. Aller MB, Vargas I, Coderch J, Vázquez ML. Doctors’ opinion on the contribution of coordination mechanisms to improving clinical coordination between primary and outpatient secondary care in the Catalan national health system. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017 Dec;17(1):842. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2690-5

5. Sampson R, Barbour R, Wilson P. The relationship between GPs and hospital consultants and the implications for patient care: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016 Apr;17(1):45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-016-0442-y

6. Scherpbier-de Haan ND, Vervoort GM, van Weel C, Braspenning JC, Mulder J, Wetzels JF, et al. Effect of shared care on blood pressure in patients with chronic kidney disease: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2013 Dec;63(617):e798–806. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp13X675386

7. Brinkhof MW, Al-Khodairy A, Eriks-Hoogland I, Fekete C, Hinrichs T, Hund-Georgiadis M, et al.; SwiSCI Study Group. Health conditions in people with spinal cord injury: contemporary evidence from a population-based community survey in Switzerland. J Rehabil Med. 2016 Feb;48(2):197–209. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2039

8. Gross-Hemmi MH, Gemperli A, Fekete C, Brach M, Schwegler U, Stucki G. Methodology and study population of the second Swiss national community survey of functioning after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2021 Apr;59(4):363–72. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-00584-3

9. Lundström U, Wahman K, Seiger Å, Gray DB, Isaksson G, Lilja M. Participation in activities and secondary health complications among persons aging with traumatic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2017 Apr;55(4):367–72. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2016.153

10. Ronca E, Scheel-Sailer A, Koch HG, Essig S, Brach M, Munzel N, et al. Satisfaction with access and quality of healthcare services for people with spinal cord injury living in the community. J Spinal Cord Med. 2018:1–11.

11. Ho CH. Primary care for persons with spinal cord injury - not a novel idea but still under-developed. J Spinal Cord Med. 2016 Sep;39(5):500–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2016.1182696

12. Chamberlain JD, Ronca E, Brinkhof MW. Estimating the incidence of traumatic spinal cord injuries in Switzerland: using administrative data to identify potential coverage error in a cohort study. Swiss Med Wkly. 2017 May;147:w14430.

13. Hagen EM, Grimstad KE, Bovim L, Gronning M. Patients with traumatic spinal cord injuries and their satisfaction with their general practitioner. Spinal Cord. 2012 Jul;50(7):527–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2011.187

14. Zanini C, Lustenberger N, Essig S, Gemperli A, Brach M, Stucki G, et al. Outpatient and community care for preventing pressure injuries in spinal cord injury. A qualitative study of service users’ and providers’ experience. Spinal Cord. 2020 Aug;58(8):882–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0444-4

15. Touhami D, Brach M, Essig S, Ronca E, Debecker I, Eriks-Hoogland I, et al. First contact of care for persons with spinal cord injury: a general practitioner or a spinal cord injury specialist? BMC Fam Pract. 2021 Oct;22(1):195. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-021-01547-0

16. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International journal for quality in health care : journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-57.

17. Tomaschek R, Touhami D, Essig S, Gemperli A. Shared responsibility between general practitioners and highly specialized physicians in chronic spinal cord injury: study protocol for a nationwide pragmatic nonrandomized interventional study. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2021 Nov;24:100873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2021.100873

18. Ronca E, Scheel-Sailer A, Koch HG, Gemperli A; SwiSCI Study Group. Health care utilization in persons with spinal cord injury: part 2-determinants, geographic variation and comparison with the general population. Spinal Cord. 2017 Sep;55(9):828–33. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.38

19. Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(1):80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

20. Diamantidis CJ, Powe NR, Jaar BG, Greer RC, Troll MU, Boulware LE. Primary care-specialist collaboration in the care of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011 Feb;6(2):334–43. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.06240710

21. Forrest CB. A typology of specialists’ clinical roles. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Jun;169(11):1062–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.114

22. Stålhammar J, Holmberg L, Svärdsudd K, Tibblin G; Jan Stålhammar, Lars Holmberg, Kurt. Written communication from specialists to general practitioners in cancer care. What are the expectations and how are they met? Scand J Prim Health Care. 1998 Sep;16(3):154–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/028134398750003106

23. Schweizerische Akademie der Medizinischen Wissenschaften (SAMW). Charta 2.0 Interprofessionelle Zusammenarbeit im Gesundheitswesen. 2020.

24. Schmitz C, Atzeni G, Berchtold P. Challenges in interprofessionalism in Swiss health care: the practice of successful interprofessional collaboration as experienced by professionals. Swiss Med Wkly. 2017 Oct;147:w14525.

25. Haddara W, Lingard L. Are we all on the same page? A discourse analysis of interprofessional collaboration. Acad Med. 2013 Oct;88(10):1509–15. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a31893

26. Berendsen AJ, Benneker WH, Schuling J, Rijkers-Koorn N, Slaets JP, Meyboom-de Jong B. Collaboration with general practitioners: preferences of medical specialists—a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006 Dec;6(1):155. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-6-155

27. Adams SG, Pitts J, Wynne J, Yawn BP, Diamond EJ, Lee S, et al. Effect of a primary care continuing education program on clinical practice of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: translating theory into practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012 Sep;87(9):862–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.02.028

28. Pang J, Grill A, Bhatt M, Woodward GL, Brimble S. Evaluation of a mentorship program to support chronic kidney disease care. Can Fam Physician. 2016 Aug;62(8):e441–7.

29. Rohrbasser A, Harris J, Mickan S, Tal K, Wong G. Quality circles for quality improvement in primary health care: their origins, spread, effectiveness and lacunae- A scoping review. PLoS One. 2018 Dec;13(12):e0202616. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202616

30. Meyer-Nikolic V, Hersperger M. Q-Monitoring-Resultate schaffen Übersicht [Q-Monitoring-Results provide overview]. Schweiz Arzteztg. 2012;93(27-28):1036–8.

31. Hummers-Pradier E, Beyer M, Chevallier P, Eilat-Tsanani S, Lionis C, Peremans L, et al. Series: The research agenda for general practice/family medicine and primary health care in Europe. Part 2. Results: Primary care management and community orientation. Eur J Gen Pract. 2010 Mar;16(1):42–50. https://doi.org/10.3109/13814780903563725

32. Smith SM, O’Kelly S, O’Dowd T. GPs’ and pharmacists’ experiences of managing multimorbidity: a ‘Pandora’s box’. Br J Gen Pract. 2010 Jul;60(576):285–94. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp10X514756

33. Berendsen AJ, Benneker WH, Meyboom-de Jong B, Klazinga NS, Schuling J. Motives and preferences of general practitioners for new collaboration models with medical specialists: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007 Jan;7(1):4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-7-4

34. Farmer J. Connected care in a fragmented world: lessons from rural health care. Br J Gen Pract. 2007 Mar;57(536):225–30.

35. Kaufmann CF, Balthasar A. Zukünftige ambulante Grundversorgung: Einstellungen und Präferenzen der Bevölkerung (Obsan Bericht 04/2021). Neuchâtel: Schweizerisches Gesundheitsobservatorium; 2021.

36. Søndergaard E, Willadsen TG, Guassora AD, Vestergaard M, Tomasdottir MO, Borgquist L, et al. Problems and challenges in relation to the treatment of patients with multimorbidity: general practitioners’ views and attitudes. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015 Jun;33(2):121–6. https://doi.org/10.3109/02813432.2015.1041828

37. O’Malley AS, Reschovsky JD. Referral and consultation communication between primary care and specialist physicians: finding common ground. Arch Intern Med. 2011 Jan;171(1):56–65. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.480

38. Szafran O, Torti JM, Kennett SL, Bell NR. Family physicians’ perspectives on interprofessional teamwork: findings from a qualitative study. J Interprof Care. 2018 Mar;32(2):169–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1395828

39. Hudson CC, Gauvin S, Tabanfar R, Poffenroth AM, Lee JS, O’Riordan AL. Promotion of role clarification in the Health Care Team Challenge. J Interprof Care. 2017 May;31(3):401–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2016.1258393

40. Kim LY, Giannitrapani KF, Huynh AK, Ganz DA, Hamilton AB, Yano EM, et al. What makes team communication effective: a qualitative analysis of interprofessional primary care team members’ perspectives. J Interprof Care. 2019;33(6):836–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1577809

41. Saba GW, Villela TJ, Chen E, Hammer H, Bodenheimer T. The myth of the lone physician: toward a collaborative alternative. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(2):169–73. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1353

Appendix: Supplementary data

The appendix is available in the pdf version of the article.