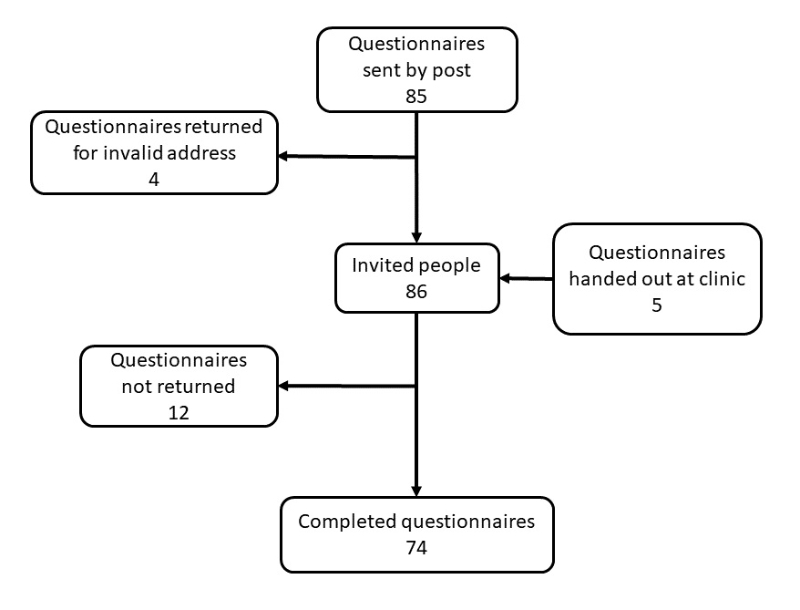

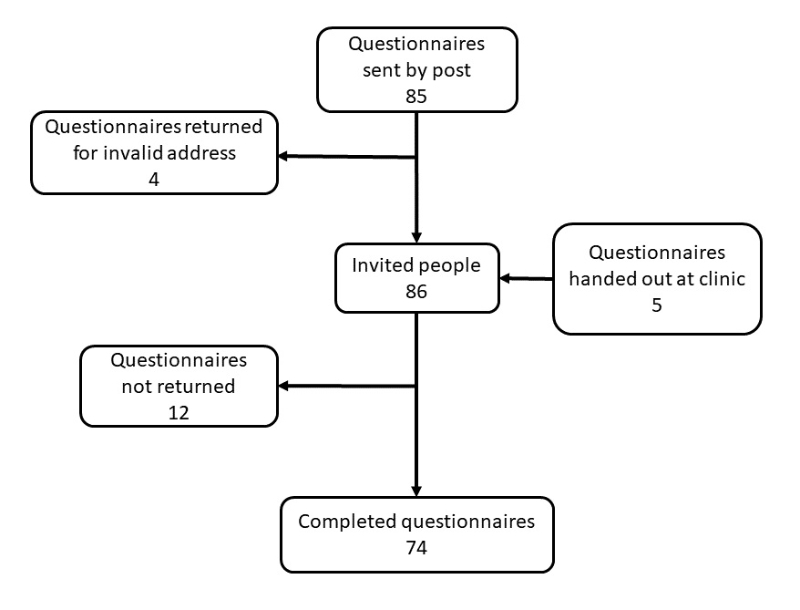

Figure 1 Flowchart of people with primary ciliary dyskinesia living in Switzerland and their parents who were invited and participated in the survey.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/SMW.2022.w30221

Due to increased respiratory workload, chronic respiratory diseases affect exercise capacity and nutritional status. These diseases are often complicated by recurrent infections that contribute further to increased metabolic demand [1–4]. Promoting a good level of physical activity and monitoring nutritional status are crucial for maintaining respiratory health; thus, they are important parts of managing chronic lung diseases. In the chronic lung disease primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD), genetic mutations cause structural and functional changes of motile cilia, which reduce mucociliary clearance [5]. Chronic respiratory symptoms and recurrent infections of the upper and lower airways are common in primary ciliary dyskinesia [6]. Therefore, among people with primary ciliary dyskinesia physical activity is recommended for improving airway clearance, in addition to specific respiratory physiotherapy practices [7–9]. We know from other chronic lung diseases, such as cystic fibrosis, that physical activity is associated with improved sputum expectoration. Particularly beneficial are higher intensity activities followed by respiratory physiotherapy [10, 11].

Yet we know little about patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia and their levels of physical activity, respiratory physiotherapy practices and nutritional status. So far, the few studies involving physical exercise among people with primary ciliary dyskinesia focused on muscle strength measurements and aerobic cardiorespiratory performance [12–15]. No studies examined the level of physical activity of people with primary ciliary dyskinesia in their everyday lives. Regarding nutritional status, no studies assessed appetite and nutritional advice given to people with primary ciliary dyskinesia. A large study from the international primary ciliary dyskinesia (iPCD) cohort reported that children younger than 9 years had lower body mass index (BMI) z-scores than healthy peers [16]. A single centre study of 43 children in the United Kingdom studied nutrition using impedance spectroscopy [17]. Both studies suggested patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia should receive nutritional advice to improve growth and delay lung disease progression [17, 18]. In Switzerland, where there is no centralised care for people with primary ciliary dyskinesia, we have no information about supportive care. Our study described physical activity, respiratory physiotherapy practices and nutritional status among people with primary ciliary dyskinesia in Switzerland, investigated how these vary by age and identified factors associated with regular physical activity.

Our national cross-sectional questionnaire survey was nested in the Swiss PCD registry (CH-PCD). CH-PCD is a population-based patient registry (www.clinicaltrials.gov; identifier NCT03606200) enrolling all people with confirmed or clinical diagnoses of primary ciliary dyskinesia in Switzerland [19]. Patients with a clinical primary ciliary dyskinesia diagnosis have a strong clinical suspicion, such as situs anomalies, persistent cough, persistent rhinitis, chronic or recurrent upper or lower respiratory infections and history of neonatal respiratory symptoms as term infants, but have not completed the diagnostic algorithm and have negative or ambiguous results for the tests performed so far [19–21].

Our reporting conforms with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement [22]. Detailed information about the study design is published elsewhere [23]. CH-PCD received ethical approval from the Cantonal Ethics Committee of Bern in 2015 (KEK-BE: 060/2015). We obtained written informed consent from participants or parents of participants younger than 14 years.

In February 2020, we sent a postal questionnaire to all people with primary ciliary dyskinesia enrolled in the CH-PCD. After we mailed the questionnaire by post, we distributed the questionnaire at the primary ciliary dyskinesia outpatient clinic in Bern to an additional five people newly enrolled in CH-PCD (fig. 1). After 2–3 weeks, we sent a reminder by post to everyone who had not yet returned questionnaires.

Figure 1 Flowchart of people with primary ciliary dyskinesia living in Switzerland and their parents who were invited and participated in the survey.

The questionnaire was based on the FOLLOW-PCD questionnaire (version 1.0), a PCD-specific standardised questionnaire, and part of a follow-up form developed by an international PCD expert group [24]. The FOLLOW-PCD questionnaire’s main domains included chronic respiratory symptoms from the past 3 months and health-related behaviours, such as physical activity during the past 12 months [23]. Our study used all original questions from the FOLLOW-PCD questionnaire and included additional questions about respiratory physiotherapy and nutritional intake. We added a section on respiratory physiotherapy based on the relevant clinical module from the FOLLOW-PCD form [24]. We reviewed the physiotherapy-related questions with respiratory physiotherapists in Switzerland to ensure they would be understandable by participants and relevant to local techniques. Lastly, we added more questions about nutritional advice in Switzerland based on expert suggestions.

We developed new questions in German, then a native French speaker with knowledge about primary ciliary dyskinesia translated them into French. Questionnaires were age-specific for adults (ages ≥18 years), adolescents (ages 14–17 years), and parents of children (ages 0–13 years) with primary ciliary dyskinesia, available in German and French [23].

We asked if participants performed sports, what type of sports and how many hours per week. For school-age children, we asked if they played school or any additional sports. We classified physical activity into five categories: aerobic activity, such as endurance or cardio activity; muscle strengthening; bone strengthening; balance activity; and flexibility activity [25]. If multiple types of physical activity were listed, we reported them all.

Since types of physical activity differ in intensity of cardiorespiratory exertion, we used metabolic equivalents (METs) to better reflect the intensity of reported activities. The MET of the adult compendium is described as the ratio of work metabolic rate to the resting metabolic rate [26]. One MET is defined as the amount of oxygen consumed sitting at rest; it is equivalent to 3.5 ml oxygen/kg body weight/min. We calculated the total MET per week based on participants’ activities. Since there is no standardised reference, we added a MET combination of gymnastics (3.8 MET) and children’s games (5.8 MET) to the total MET per week for children who always performed school sports. For children attending school sports sometimes or usually, we added one third or two thirds of the MET combination of gymnastics and children’s games, respectively. We categorised physical activity in three MET intensity categories: light (<3.0 METs), moderate (3.0–5.9 METs), and vigorous (≥6.0 METs) [27].

We assessed participant nutritional status by collecting information about appetite, physician advice for increasing caloric intake during the past 12 months and calculating participants' BMIs. If increasing caloric intake was recommended, we asked about specific recommendations, such as increases of energy-dense food, larger portion size, or meal frequency. Furthermore, we assessed if recommendations had been successful in increasing energy and if body weight stabilised or increased. Other questions revolved around intake of oral nutritional supplements.

To calculate BMI, we used height and weight data from the CH-PCD measured in the hospital or private practices closest to the time when participants completed the survey. We calculated BMI by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared (kg/m2). We classified BMI for adults as underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal (≥18.5 to <25), overweight (≥25.0 to <30) or obese (≥30.0 to <35) by World Health Organization (WHO) standards [28]. For children and adolescents aged 5–17 years, we calculated sex and age-specific BMI z-scores based on the 2007 WHO references [29]. We defined thinness (<—2 z-scores), normal (—2 to 1 z-scores), overweight (1 to 2 z-scores), and obesity (>2 z-scores).

We collected information on respiratory physiotherapy practices during the past three months, including if participants performed any physiotherapy; whether they had seen a professional physiotherapist; and which respiratory practices they used for upper and lower airway clearance, such as nose blowing, nasal rinsing, specific airway clearance techniques and use of breathing exercise aids. We asked about the use of inhalation for the upper and lower airways, particularly with isotonic (0.9% sodium chloride) or hypertonic (>0.9% sodium chloride) saline. Lastly, we asked how difficult airway clearance was for them during this period and if they felt any improvement of their respiratory symptoms after respiratory physiotherapy.

The questionnaire asked about several upper and lower respiratory symptoms and their frequency during the past 3 months. We defined symptoms as frequent if they were reported daily or often. Reported frequency of all symptoms ranged from daily, often, sometimes, and rarely to never [23].

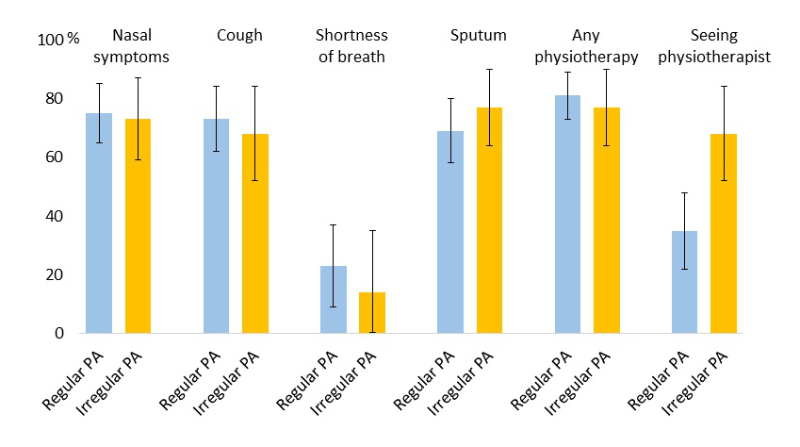

We categorised physical activity into regular (once a week or more) and irregular (less than once a week). We considered the following factors as possibly associated with regular physical activity: experiencing respiratory symptoms, such as chronic nasal symptoms, cough, shortness of breath and sputum production, that might influence physical activity performance; performing any physiotherapy; and seeing professional physiotherapists.

We described characteristics of the population, physical activity, respiratory physiotherapy practices, and nutritional status in the total population and separately among children (<18 years) and adults with primary ciliary dyskinesia. We also described possible differences in physical activity, and respiratory physiotherapy practices by sex and nutritional status, and in nutritional status by sex. For continuous variables, we used median and interquartile range (IQR); for categorical variables, we used numbers and proportions. We used Wilcoxon rank-sum and Pearson's Chi square to study differences between children and adults and factors possibly associated with regular physical activity. We calculated Wilson 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for proportions. Missing data were reported as such and were excluded from analyses. We performed all analyses with Stata version 16 (StataCorp LLC, Texa, USA).

We invited 86 people; 74 (86%) participants returned the questionnaire (fig. 1). The median age at survey completion was 23 years (IQR 15–51) and 38 (51%) were female. Among the participants, 24 were children or adolescents (referred as children from now onwards) of whom 17 attended school. Of the 50 adults, 42% were employed full-time (80–100%), whereas 18% were retired or on disability pension (table 1). In the past 12 months, most children and adults (64%) missed less than 1 week of school or work due to PCD-related symptoms; few adults (10%) missed more than 2 weeks. About half of participants (46%) lived in areas with little or no traffic. Age and sex did not differ between questionnaire respondents and non-respondents (supplementary table S1 in the appendix). Missing responses to individual survey questions were less than 5%.

Table 1Characteristics of people with primary ciliary dyskinesia in Switzerland participating in the survey, overall and by age group (n = 74).

| Total, n (%) | Children <18 y, n (%) | Adults ≥18 y, n (%) | p -value | |

| Number of participants | 74 (100) | 24 (100) | 50 (100) | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 23 (15–51) | 11 (6–15) | 32 (23–57) | |

| Sex, female | 38 (51) | 7 (29) | 31 (62) | 0.008 |

| Occupation | ||||

| Student/preschool | 29 (39) | 24 (100) | 5 (10) | |

| 81–100% employment | 21 (28) | - | 21 (42) | |

| 61–80% employment | 2 (3) | - | 2 (4) | |

| 41–60% employment | 5 (7) | - | 5 (10) | |

| ≤40% employment | 8 (11) | - | 8 (16) | |

| Retired/disability pension | 9 (12) | - | 9 (18) | |

| Missing (pre)school or work days due to primary ciliary dyskinesia in the past 12 months | 0.345 | |||

| 0–6 days | 46 (62) | 15 (63) | 31 (63) | |

| 1–2 weeks | 8 (11) | 4 (17) | 4 (8) | |

| >2 weeks | 5 (7) | 0 (0) | 5 (10) | |

| Not in school yet/ retired | 12 (16) | 3 (12) | 9 (18) | |

| Not reported | 3 (4) | 2 (8) | 1 (1) | |

| Area of residence | 0.949 | |||

| Street with dense traffic | 17 (23) | 6 (25) | 11 (22) | |

| Street with moderate traffic | 23 (31) | 7 (29) | 16 (32) | |

| Street with little or no traffic | 34 (46) | 11 (46) | 23 (46) | |

y: years. All characteristics are presented as n and column % with the exception of age presented as median and interquartile range (IQR).

Among all 74 participants, 48 (65%) performed sports regularly (table 2). All 17 schoolchildren attended school sports; 14 of them (82%) participated always. The seven children not yet in school were all physically active. Categories of sports did not differ by age. The most common type of physical activity were aerobic activities, for example, children played soccer or hockey (25%), whereas adults preferred jogging or walking (56%). We found children were vigorously active (median MET 9.1; IQR 7.9–9.6) and adults were moderately active (median MET 5.5; IQR 4.3–6.9). Adults spent more time (median 7 hours/week; IQR 3.5–12) performing light sports when compared with children who spent most of their time (median 4 hours/week; IQR 3–7) performing vigorous sports. We present the most reported physical activities in supplementary table S1 (appendix). We found no differences in physical activity by sex. Underweight and normal weight participants reported more frequently aerobic activities compared with overweight or obese individuals (supplementary table S3).

Table 2Physical activity of people with primary ciliary dyskinesia in Switzerland, overall and by age group (n = 74).

| Total, n (%) | Children <18 y, n (%) | Adults ≥18 y, n (%) | p -value | |

| Number of participants | 74 (100) | 24 (100) | 50 (100) | |

| Regular sports a | 48 (65) | 13 (54) | 35 (70) | 0.182 |

| School sports attendance | 17 (71) | NA | ||

| Always | 14 (59) | NA | ||

| Usually | 2 (8) | NA | ||

| Sometimes | 1 (4) | NA | ||

| Not yet in school | 7 (29) | NA | ||

| Sports categories b | ||||

| Aerobic activity | 37 (50) | 9 (38) | 28 (56) | 0.136 |

| Muscle strengthening | 21 (28) | 5 (21) | 16 (32) | 0.319 |

| Bone strengthening | 4 (5) | 2 (8) | 2 (4) | 0.440 |

| Balance | 5 (7) | 2 (8) | 3 (6) | 0.708 |

| Flexibility | 3 (4) | 1 (4) | 2 (4) | 0.973 |

| Total MET per week c | 6.8 (4.8–8.9) | 9.1 (7.9–9.6) | 5.5 (4.3–6.9) | <0.001 |

| Sports hours/week by MET categories d | ||||

| Light (<3.0 METs) | 7 (3.5–12) | 0 (0) | 7 (3.5–12) | |

| Moderate (3.0–5.9 METs) | 3 (2–3) | 2.5 (2–6) | 3 (2–3) | 0.336 |

| Vigorous (≥6.0 METs) | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–7) | 5 (3–5.5) | 0.198 |

y: years; NA: not applicable.

Characteristics are presented as n and column %, metabolic equivalent (MET = 1 kcal/kg/hour) described in median and interquartile range (IQR).

a For children, this refers to additional sports besides school sports.

b Sports categories were not mutually exclusive

c Average sports intensity per week in MET (median, IQR) including school sports for schoolchildren

d Reported hours per week participants spent performing sports by MET categories (median and IQR)

Overall, most participants (59; 80%) reported they performed some type of respiratory physiotherapy; of these, 18 children (75%) and 28 adults (56%), this was daily. Only 15 adults (30%) saw a professional physiotherapist in comparison with 18 children (75%) (p = 0.008). Regarding upper airway physiotherapy, 69% of the participants blew their noses, most daily (table 3). Over half of participants (61%) performed nasal rinsing, 8 children (33%) and 13 adults (26%) daily. Only 21 participants (28%) performed inhalations for the upper airways, eight children (33%) and five adults (10%) daily. Among all participants, 11 (17%) used saline for upper airway inhalation, 9 of them hypertonic (>0.9%) saline. We found no differences in upper airway physiotherapy practices between children and adults apart from nose blowing and nasal rinsing, which were more common in children.

Table 3Upper airway physiotherapy practices of people with primary ciliary dyskinesia in Switzerland, overall and by age group (n = 74).

| Total, n (%) | Children <18 y,n (%) | Adults ≥18 y, n (%) | p -value | |

| Number of participants | 74 (100) | 24 (100) | 50 (100) | |

| Nose blowing | 0.021 | |||

| Yes, daily | 37 (50) | 10 (42) | 27 (54) | |

| Yes, often | 8 (11) | 5 (21) | 3 (6) | |

| Yes, sometimes | 3 (4) | 2 (8) | 1 (2) | |

| Yes, rarely | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Yes, only during colds | 3 (4) | 3 (12) | 0 (0) | |

| No / not reported | 23 (31) | 4 (17) | 19 (38) | |

| Nasal rinsing | ||||

| Yes, daily | 21 (28) | 8 (33) | 13 (26) | 0.021 |

| Yes, often | 11 (15) | 4 (17) | 7 (14) | |

| Yes, sometimes | 6 (8) | 5 (21) | 1 (2) | |

| Yes, rarely | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 3 (6) | |

| Yes, only during colds | 4 (6) | 4 (17) | 0 (0) | |

| No / not reported | 29 (39) | 3 (12) | 26 (52) | |

| Inhalations for the upper airways | 0.146 | |||

| Yes, daily | 13 (18) | 8 (33) | 5 (10) | |

| Yes, often | 4 (5) | 1 (4) | 3 (6) | |

| Yes, sometimes | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 3 (6) | |

| Yes, rarely | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |

| Yes, only during colds | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| No / not reported | 53 (72) | 15 (63) | 38 (76) | |

| Upper airways inhalation with saline | 11 (15) | 7 (29) | 4 (8) | 0.237 |

| Isotonic (0.9% sodium chloride) | 2 (3) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | |

| Hypertonic (>0.9% sodium chloride) | 9 (12) | 5 (21) | 4 (8) | |

| Upper airways inhalation with other medication | 5 (7) | 3 (13) | 2 (4) | |

y: years. All characteristics are presented as nN and column %.

Regarding lower airway physiotherapy, 49 participants (67%) applied some airway clearance technique, such as autogenic drainage, 21 participants (28%) daily (table 4). The most common aid used for airway clearance was a flutter (19%) or positive expiratory pressure combined with flutter (7%). Overall, 65% performed inhalations for lower airways, 63% of children and 42% of adults daily, mainly with hypertonic saline. Nineteen participants (26%) reported difficulty clearing their lower airways; 13 children (54%) and 18 adults (36%) reported their lower respiratory symptoms improved after physiotherapy. Lower airway physiotherapy practices did not differ between children and adults.

Table 4Lower airway physiotherapy practices of people with primary ciliary dyskinesia in Switzerland, overall and by age group (n = 74).

| Total, n (%) | Children <18 y, n (%) | Adults ≥18 y, n (%) | p -value | |

| Number of participants | 74 (100) | 24 (100) | 50 (100) | |

| Airway clearance techniques a | 0.735 | |||

| Yes, daily | 21 (28) | 8 (33) | 13 (26) | |

| Yes, often | 8 (11) | 2 (8) | 6 (12) | |

| Yes, sometimes | 13 (18) | 4 (17) | 9 (18) | |

| Yes, rarely | 5 (7) | 3 (13) | 2 (4) | |

| Yes, only during colds | 2 (3) | 1 (4) | 1 (2) | |

| No / not reported | 25 (33) | 6 (25) | 19 (38) | |

| Use of aid for airway clearance | 0.565 | |||

| Flutter | 14 (19) | 5 (21) | 9 (18) | |

| PEP | 3 (4) | 2 (8) | 1 (2) | |

| Flutter and PEP | 5 (7) | 2 (8) | 3 (6) | |

| Blow in straw/nozzle | 3 (4) | 3 (13) | 0 (0) | |

| Vibrating device | 2 (3) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | |

| No / not reported | 47 (63) | 10 (42) | 37 (74) | |

| Inhalation for the lower airways | ||||

| Daily | 36 (49) | 15 (63) | 21 (42) | 0.233 |

| Often | 4 (5) | 1 (4) | 3 (6) | |

| Sometimes | 6 (8) | 0 (0) | 6 (12) | |

| Only during colds | 2 (3) | 1 (4) | 1 (2) | |

| No / not reported | 26 (35) | 7 (29) | 19 (38) | |

| Lower airways inhalation with saline | 0.515 | |||

| Yes | 35 (47) | 14 (58) | 21 (42) | |

| Isotonic (0.9% sodium chloride) | 4 (5) | 1 (4) | 3 (6) | |

| Hypertonic (>0.9% sodium chloride) | 31 (42) | 13 (54) | 18 (36) | |

| Lower airways inhalation with other medication | 28 (38) | 9 (38) | 19 (38) | |

| Difficulty of clearing lower airways | 0.581 | |||

| Easy | 42 (57) | 12 (50) | 30 (60) | |

| Difficult | 19 (26) | 8 (33) | 11 (22) | |

| I don’t know / not reported | 13 (17) | 4 (17) | 9 (18) | |

y: years; PEP: positive expiratory pressure. a Airway clearance techniques e.g., autogenic drainage. All characteristics are presented as n and column %.

We found no differences in upper and lower respiratory physiotherapy practices between males and females, as well as between underweight/normal weight and overweight/obese participants (supplement tables S4 and S5).

Weight and height information from clinical visits near survey completion (within 12 months, usually a few months apart) was available for 53 (72%) participants: 16 children and 37 adults. Median BMI was 22.3 kg/m2 (IQR 20.4–25.0) for adults and median BMI z-score was 1.0 (IQR 1.0–1.0) for children (table 5). Half of the participants had a normal BMI; only one child (4%) and two adults (4%) were underweight/thin. There was no difference between children and adults or between males and females in BMI categories (table 5 and supplementary table S6). Overall, seven people reported decreased appetite (9%). Physicians recommended increased caloric intake to three children (13%) and three adults (6%); three people (4%) ate larger meal portions, two increased their meal frequency, and one child received energy-dense food. Five adult participants reported ingesting hypercaloric drinks, four only during periods of increased physical activity or colds. Increased caloric intake and hypercaloric drinks helped four patients stabilise or gain weight. One child and two adults reported these measures increased their energy.

Table 5Nutritional information of people with primary ciliary dyskinesia in Switzerland, overall and by age group (n = 74).

| Total, n (%) | Children <18 y, n (%) | Adults ≥18 y, n (%) | p -value | |

| Number of participants | 74 (100) | 24 (100) | 50 (100) | |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 22.3 (20.4–25.0) | |||

| BMi z-score, median (IQR) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | |||

| BMI categories | 0.894 | |||

| Thinness/underweight | 3 (4) | 1 (4) | 2 (4) | |

| Normal weight | 37 (50) | 12 (50) | 25 (50) | |

| Overweight | 10 (14) | 2 (8) | 8 (16) | |

| Obesity | 3 (4) | 1 (4) | 2 (4) | |

| Missing | 21 (28) | 8 (34) | 13 (26) | |

| Physician recommendation to increase caloric intake by | ||||

| Energy-dense food | 1 (1) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Larger meal portions | 3 (4) | 1 (4) | 2 (4) | |

| Increased meal frequency | 2 (3) | 1 (4) | 1 (2) | |

| Use of hypercaloric drinks in the past 12 months | ||||

| Yes | 5 (7) | 0 (0) | 5 (10) | |

| Weight gained/stabilised due to increased caloric intake | ||||

| Yes | 3 (4) | 0 (4) | 3 (6) | |

y: years; BMI: body mass index. All characteristics are presented as n and column % with the exception of BMI and BMI z-score presented as median and interquartile range (IQR).

BMI was available for 16 children and 37 adults. BMI categories were based on the World Health Organization (WHO) 2007 standards, using BMI in kg/m2 for adults (underweight <18.5, normal weight ≥18.5 to <25, overweight ≥25.0 to <30, obesity ≥30.0 to <35), and calculating BMI z-scores based on the WHO references for children (thinness <—2 z-scores, normal weight —2 to 1 z-scores, overweight 1 to 2 z-scores, obesity >2 z-scores).

We found no difference in frequency of reported nasal symptoms, cough, shortness of breath and sputum production between participants who were regularly or less physically active (fig. 2). Respiratory physiotherapy was not associated with regular physical activity. However, regularly physically active people were less likely to see professional physiotherapists (p = 0.008).

Figure 2 Frequency and 95% confidence interval of reported respiratory symptoms and use of respiratory physiotherapy in the past three months in people with primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) in Switzerland who perform regular (at least once a week) physical activity (PA) compared with people who are less physically active.

Our study is the first to provide patient-reported data on physical activity, respiratory physiotherapy and nutrition for people with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Our results suggest people with primary ciliary dyskinesia in Switzerland are health-oriented, physically active and normal weight; they also perform respiratory physiotherapy.

A strength of our study includes our questionnaire. We based our survey on the PCD-specific standardised FOLLOW-PCD questionnaire [24], allowing for future comparisons with larger multicentre studies. We also developed additional questions based on input from experts, such as physiotherapists. Further, we nested our study in the national PCD registry, which provided objectively measured BMI data. Other strengths include a remarkable response rate of 86% and a low proportion of missing survey data.

Our study has several limitations. Although we invited all people enrolled in CH-PCD, selection bias is possible because primary ciliary dyskinesia in Switzerland is underdiagnosed [19]. The COVID-19 pandemic could have affected physical activity. However, since more than 75% of the questionnaires were returned by March 2020 before lockdown in Switzerland started, we expect any effect to be small. Furthermore, most participants reported outdoor activities, which were not affected by COVID-19 restrictions. As many questions referred to the last 12 months, there is a risk of recall bias. We expect answers reflected mostly health-related behaviours closer to date of survey completion. Since FOLLOW-PCD does not include validated physical activity questions, we calculated MET for reported activities to describe exercise intensity. So far, MET is standardised for adults only; however, to describe and compare the intensity of physical activity for the whole study population, we calculated it for all participants.

Previous studies among people with primary ciliary dyskinesia showed reduced physical fitness in hospital settings. For example, a recent single-centre study of 27 Turkish children with primary ciliary dyskinesia reported reduced muscle strength and endurance [15]. Another single-centre study with 22 Danish children with primary ciliary dyskinesia found reduced cardiopulmonary fitness [14]. Children in our study reported a median moderate to vigorous activity of 6.5 hours/week, which is lower than the average 7.5 hours/week among 10–14-year-old children and 6.5 hours/week among 15–19-year-old adolescents who perform additional sports besides attending school sports in Switzerland [30]. However, it is comparable to the level of recreational sports (median 3.0 hours/week, IQR 1–5) of children who survived cancer in Switzerland [31]. In a multicentre service evaluation of over 300 children with primary ciliary dyskinesia in England, all children were trained and advised to perform regular airway clearance physiotherapy [32]. In our population, most people reported doing respiratory physiotherapy but only 18 children (75%) and 28 adults (56%) on a daily basis. Despite having chronic respiratory symptoms, most people with primary ciliary dyskinesia in Switzerland have a normal BMI, which is lower than the national average of three people with overweight, and one person with obesity of every ten adults in Switzerland [33]. Our study included very few children younger than age 9 so it was not possible to see whether this group had a lower BMI z-score as in the large iPCD cohort study [18].

Most participants were physically active, despite reporting frequent respiratory symptoms. This might indicate that people with primary ciliary dyskinesia are accustomed to their chronic symptoms and exercise despite them. Or they use physical activity as a method for airway clearance to relieve symptoms, explaining why fewer people who exercised regularly saw a professional physiotherapist. People might replace respiratory physiotherapy with physical activity. Exercise is a recommended method of airway clearance for patients with cystic fibrosis. However, it remains unclear whether it can replace physiotherapy or to what extent for patients with cystic fibrosis or primary ciliary dyskinesia [8, 34]. Although physical activity aids in airway clearance of larger airways, peripheral airway dysfunction persists with mucus obstruction [35].

Our study is the first to provide patient-reported data on health-related behaviours of people diagnosed with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Our results highlight the importance of implementing exercise recommendations, professional respiratory physiotherapy, and nutritional advice that are currently missing in the routine care of people with primary ciliary dyskinesia in Switzerland. Multidisciplinary care in specialised centres by teams including physiotherapists and nutrition consultants could improve the daily lives of people with primary ciliary dyskinesia in Switzerland.

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the CH-PCD study team (pcd@ispm.ch) upon reasonable request.

We thank all people with primary ciliary dyskinesia and their families in Switzerland for participating in the survey and the CH-PCD. We are also grateful to the Swiss PCD support group that closely collaborates with us. We thank Eugenie Collaud (ISPM, University of Bern) for her contributions to the French translation of the questionnaire and Kristin Marie Bivens (ISPM, University of Bern) for her editorial assistance.

The current Swiss PCD research group includes (in alphabetical order): Juerg Barben (Children's Hospital of Eastern Switzerland), Sylvain Blanchon (University Hospital of Lausanne), Jean-Louis Blouin (University Hospitals of Geneva), Marina Bullo (University Children's Hospital Bern), Carmen Casaulta (University Children's Hospital Bern), Christian Clarenbach (University Hospital of Zurich), Myrofora Goutaki (ISPM, University of Bern), Nicolas Gürtler (University Hospital of Basel), Beat Haenni (Institute of Anatomy, University of Bern), Andreas Hector (University Children’s Hospital Zurich), Michael Hitzler (Children’s Hospital Lucerne), Andreas Jung (University Children’s Hospital Zurich), Lilian Junker (Hospital Thun), Elisabeth Kieninger (University Children's Hospital Bern), Claudia E. Kuehni (ISPM, University of Bern), Yin Ting Lam (ISPM, University of Bern), Philipp Latzin (University Children's Hospital Bern), Romain Lazor (University Hospital of Lausanne), Dagmar Lin (University Hospital Bern), Marco Lurà (Children’s Hospital Lucerne), Loretta Müller (University Children's Hospital Bern), Eva Pedersen (ISPM, University of Bern), Nicolas Regamey (Children’s Hospital Lucerne), Isabelle Rochat (University Hospital Lausanne), Daniel Schilter (Quartier Bleu Bern), Iris Schmid (Quartier Bleu Bern), Bernhard Schwizer (Quartier Bleu Bern), Andrea Stokes (University Children's Hospital Bern), Daniel Trachsel (University Children’s Hospital Basel), Stefan A. Tschanz (Institute of Anatomy, University of Bern), Johannes Wildhaber (Children'sHospital Fribourg), and Maura Zanolari (Hospital of Bellinzona).

Author contributions: MG and CEK developed the concept and designed the survey. YTL, MG, and LH organised the survey, then cleaned and standardised the data. YTL performed the statistical analyses supervised by MG and EP. YTL, MG, and EP drafted the manuscript. All authors commented and revised the manuscript. YTL and MG take final responsibility for the content.

This study is funded by a Swiss National Science Foundation Ambizione fellowship (PZ00P3_185923) and by a Swiss National Science Foundation project grant (320030B_192804). PCD research at the Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine (ISPM) at the University of Bern also receives funding by the Lung League Bern. The authors participate in the BEAT-PCD (Better experimental approaches to treat PCD) clinical research collaboration, supported by the European Respiratory Society, and they are supporting members of the PCD core of ERN-LUNG (European Reference Network on rare respiratory diseases). FNB is supported by Swiss Cancer Research (KFS-4722-02-2019).

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. CC received advisory fees from Roche, Novartis, Boehringer, GSK, Astra Zeneca, Sanofi, Vifor, OM Pharma, CSL Behring, Grifols, Daiichi Sankyo and Mundipharma within the last 36 months. PL received grants, honorary, for participation in data safety monitoring board or advisory board from Vertex, Vifor, OM Pharma, Polyphor, Santhera, Sanofi Aventis within the last 36 months. No other potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

1. Fernandes AC , Bezerra OM . Nutrition therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and related nutritional complications. J Bras Pneumol. 2006 Sep-Oct;32(5):461–71. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132006000500014

2. Cordova-Rivera L , Gibson PG , Gardiner PA , McDonald VM . Physical activity associates with disease characteristics of severe asthma, bronchiectasis and COPD. Respirology. 2019 Apr;24(4):352–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.13428

3. Urquhart DS . Exercise testing in cystic fibrosis: why (and how)? J R Soc Med. 2011 Jul;104(1_suppl Suppl 1):S6–14. https://doi.org/10.1258/JRSM.2011.S11102

4. Vogiatzis I , Zakynthinos G , Andrianopoulos V . Mechanisms of physical activity limitation in chronic lung diseases. Pulm Med. 2012;2012:634761. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/634761

5. Barbato A , Frischer T , Kuehni CE , Snijders D , Azevedo I , Baktai G , et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: a consensus statement on diagnostic and treatment approaches in children. Eur Respir J. 2009 Dec;34(6):1264–76. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00176608

6. Goutaki M , Meier AB , Halbeisen FS , Lucas JS , Dell SD , Maurer E , et al. Clinical manifestations in primary ciliary dyskinesia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2016 Oct;48(4):1081–95. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00736-2016

7. Valerio G , Giallauria F , Montella S , Vaino N , Vigorito C , Mirra V , et al. Cardiopulmonary assessment in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur J Clin Invest. 2012 Jun;42(6):617–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2362.2011.02626.x

8. Schofield LM , Duff A , Brennan C . Airway Clearance Techniques for Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia; is the Cystic Fibrosis literature portable? Paediatr Respir Rev. 2018 Jan;25:73–7.

9. Kuehni CE , Goutaki M , Rubbo B , Lucas JS . Management of primary ciliary dyskinesia: current practice and future perspectives In: Chalmers JD, Polverino E, Aliberti S, eds. Bronchiectasis (ERS Monograph). 2018.

10. Kriemler S , Radtke T , Christen G , Kerstan-Huber M , Hebestreit H . Short-Term Effect of Different Physical Exercises and Physiotherapy Combinations on Sputum Expectoration, Oxygen Saturation, and Lung Function in Young Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. Lung. 2016 Aug;194(4):659–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-016-9888-x

11. Nigro E , Polito R , Elce A , Signoriello G , Iacotucci P , Carnovale V , et al. Physical Activity Regulates TNFα and IL-6 Expression to Counteract Inflammation in Cystic Fibrosis Patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094691

12. Simsek S , Inal-Ince D , Cakmak A , Emiralioglu N , Calik-Kutukcu E , Saglam M , et al. Reduced anaerobic and aerobic performance in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur J Pediatr. 2018 May;177(5):765–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-018-3121-2

13. Madsen A , Green K , Buchvald F , Hanel B , Nielsen KG . Aerobic fitness in children and young adults with primary ciliary dyskinesia. PLoS One. 2013 Aug;8(8):e71409. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071409

14. Ring AM , Buchvald FF , Holgersen MG , Green K , Nielsen KG . Fitness and lung function in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia and cystic fibrosis. Respir Med. 2018 Jun;139:79–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2018.05.001

15. Firat M , Bosnak-Guclu M , Sismanlar-Eyuboglu T , Tana-Aslan A . Respiratory muscle strength, exercise capacity and physical activity in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia: A cross-sectional study. Respir Med. 2022 Jan;191:106719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106719

16. Goutaki M , Maurer E , Halbeisen FS , Amirav I , Barbato A , Behan L , et al.; PCD Italian Consortium; Swiss PCD Group; French Reference Centre for Rare Lung Diseases; Genetic Disorders of Mucociliary Clearance Consortium . The international primary ciliary dyskinesia cohort (iPCD Cohort): methods and first results. Eur Respir J. 2017 Jan;49(1):49. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01181-2016

17. Marino LV , Harris A , Johnstone C , Friend A , Newell C , Miles EA , et al. Characterising the nutritional status of children with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Clin Nutr. 2019 Oct;38(5):2127–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2018.08.034

18. Goutaki M , Halbeisen FS , Spycher BD , Maurer E , Belle F , Amirav I , et al.; PCD Israeli Consortium; Swiss PCD Group; French Reference Centre for Rare Lung Diseases . Growth and nutritional status, and their association with lung function: a study from the international Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Cohort. Eur Respir J. 2017 Dec;50(6):50. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01659-2017

19. Goutaki M , Eich MO , Halbeisen FS , Barben J , Casaulta C , Clarenbach C , et al.; Swiss PCD Registry (CH-PCD) Working Group . The Swiss Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia registry: objectives, methods and first results. Swiss Med Wkly. 2019 Jan;149:149.

20. Lucas JS , Barbato A , Collins SA , Goutaki M , Behan L , Caudri D , et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur Respir J. 2017 Jan;49(1):49. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01090-2016

21. Müller L , Savas ST , Tschanz SA , Stokes A , Escher A , Nussbaumer M , et al. On Behalf Of The Swiss Pcd Research G. A Comprehensive Approach for the Diagnosis of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia-Experiences from the First 100 Patients of the PCD-UNIBE Diagnostic Center. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;•••:11.

22. von Elm E , Altman DG , Egger M , Pocock SJ , Gøtzsche PC , Vandenbroucke JP ; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008 Apr;61(4):344–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008

23. Goutaki M , Hüsler L , Lam YT , Collaud E , Koppe H , Pedersen E , et al. Respiratory symptoms of Swiss people with Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia. Eur Respir J. 2021;58:OA2956.

24. Goutaki M , Papon JF , Boon M , Casaulta C , Eber E , Escudier E , et al. Standardised clinical data from patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia: FOLLOW-PCD. ERJ Open Res. 2020 Feb;6(1):6. https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00237-2019

25. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans . 2nd edition. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018. (Accessed 29.03.2022, at https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/index.htm)

26. Garber CE , Blissmer B , Deschenes MR , Franklin BA , Lamonte MJ , Lee IM , et al.; American College of Sports Medicine . American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011 Jul;43(7):1334–59. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb

27. Haskell WL , Lee IM , Pate RR , Powell KE , Blair SN , Franklin BA , et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007 Aug;39(8):1423–34. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616b27

28. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;894:i–xii.

29. WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group . WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2006 Apr;450:76–85.

30. Sport Schweiz 2020: Kinder- und Jugendbericht. 2021. (Accessed 29.03.2022, at https://www.admin.ch/gov/de/start/dokumentation/medienmitteilungen.msg-id-84993.html)

31. Schindera C , Weiss A , Hagenbuch N , Otth M , Diesch T , von der Weid N , et al.; Swiss Pediatric Oncology Group (SPOG) . Physical activity and screen time in children who survived cancer: A report from the Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020 Feb;67(2):e28046. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.28046

32. Rubbo B , Best S , Hirst RA , Shoemark A , Goggin P , Carr SB , et al.; English National Children’s PCD Management Service . Clinical features and management of children with primary ciliary dyskinesia in England. Arch Dis Child. 2020 Aug;105(8):724–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2019-317687

33. Das Gewicht der Schweiz . Eine quantitative Synthesestudie zum Body Mass Index und Bauchumfang sowie den damit verbundenen Kofaktoren bei erwachsenen Männern und Frauen in der Schweiz. 2020. at https://gesundheitsfoerderung.ch/public-health/ernaehrung-und-bewegung-bei-kindern-und-jugendlichen/produkte-dienstleistungen/rechner-body-mass-index-bmi.html)

34. Barak A , Wexler ID , Efrati O , Bentur L , Augarten A , Mussaffi H , et al. Trampoline use as physiotherapy for cystic fibrosis patients. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005 Jan;39(1):70–3. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.20133

35. Schofield LM , Horobin HE . Growing up with Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia in Bradford, UK: exploring patients experiences as a physiotherapist. Physiother Theory Pract. 2014 Apr;30(3):157–64. https://doi.org/10.3109/09593985.2013.845863

Table S1Characteristics of people with primary ciliary dyskinesia in Switzerland, respondents and non-respondents to the survey.

| Respondents, n (%) | Non-respondents, n(%) | p -value | |

| Number | 74 (100) | 12 (100) | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 23 (15–51) | 37 (20–46) | 0.449 |

| Sex, female | 38 (51) | 8 (67) | 0.324 |

y: years. Characteristics are presented as n and column % with the exception of age presented as median and IQR: interquartile range.

Table S2Top 10 most common types of physical activity of people with primary ciliary dyskinesia in Switzerland, overall and by age group. Some people reported multiple activities.

| Total | Children <18 y | Adults ≥18 y | |

| Number of participants | 74 | 24 | 50 |

| Training in gym | 17 | 0 | 17 |

| Walking | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| Cycling | 9 | 1 | 8 |

| Jogging | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Ice hockey | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Hiking | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Horseback riding | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Skiing/snowboarding | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Badminton | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Climbing | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Table S3Physical activity of people with primary ciliary dyskinesia in Switzerland, overall, by sex (n = 74), and BMI categories (n = 53).

| Total, n (%) | Female, n (%) | Male, n(%) | p -value | Normal weight / underweight, n (%) a | Overweight/obese,n (%) a | p -value | |

| Number of participants | 74 (100) | 38 (100) | 36 (100) | 40 (100) | 13 (100) | ||

| Regular sports b | 48 (65) | 24 (63) | 24 (67) | 0.752 | 25 (63) | 11 (85) | 0.100 |

| School sports attendance c | 0.660 | 0.110 | |||||

| Always | 14 (59) | 4 (11) | 10 (28) | 12 (30) | 2 (15) | ||

| Usually | 2 (8) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | ||

| Sometimes | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | ||

| Not yet in school | 7 (29) | 2 (5) | 5 (14) | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | ||

| Sports categories d | |||||||

| Aerobic activity | 37 (50) | 19 (50) | 18 (50) | 1.000 | 18 (45) | 10 (77) | 0.045 |

| Muscle strengthening | 21 (28) | 8 (21) | 13 (36) | 0.151 | 12 (30) | 4 (31) | 0.958 |

| Bone strengthening | 4 (5) | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 0.331 | 2 (5) | 1 (8) | 0.715 |

| Balance | 5 (7) | 4 (11) | 1 (3) | 0.184 | 2 (5) | 2 (15) | 0.218 |

| Flexibility | 3 (4) | 1 (3) | 2 (6) | 0.524 | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.411 |

| Total MET per week e | 6.8(4.8–8.9) | 6(4.3–8.5) | 7(4.8–9) | 0.464 | 7.9(4.8–9.5) | 6.6(4.8–9) | 0.449 |

| Sports hours/week by MET categories f | |||||||

| Light (<3.0 METs) | 7(3.5–12) | 7(3.5–14) | 3.5(2.5–10) | 0.367 | 7(4.8–13.5) | 8.8(3.5–14) | 0.199 |

| Moderate (3.0–5.9 METs) | 3 (2–3) | 2.8 (2–3) | 3 (2–4) | 0.336 | 3 (2.5–5) | 2.5 (2–3) | 0.611 |

| Vigorous (≥6.0 METs) | 4 (3–6) | 3 (3–5) | 5 (3–7.5) | 0.198 | 4.5 (3–7) | 5 (4–5.5) | 0.230 |

Characteristics are presented as n and column %, metabolic equivalent (MET = 1 kcal/kg/hour) described in median and IQR: interquartile range.

a BMI was available for 53 participants. BMI categories were based on the World Health Organization (WHO) 2007 standards, using BMI in kg/m2 for adults (underweight <18.5, normal weight ≥18.5 to <25, overweight ≥25.0 to <30, obesity ≥30.0 to <35), and calculating BMI z-scores based on the WHO references for children (thinness <-2 z-scores, normal weight -2–1 z-scores, overweight 1–2 z-scores, obesity >2 z-scores).

b For children, this refers to additional sports besides school sports. .

c Sports categories were not mutually exclusive

d Average sports intensity per week in MET (median, IQR) including school sports for schoolchildren

e Reported hours per week participants spent performing sports by MET categories (median and IQR).

Table S4Upper airway physiotherapy practices of people with primary ciliary dyskinesia in Switzerland, overall, by sex (n = 74), and BMI categories (n = 53).

| Total, n (%) | Female, n (%) | Male , n (%) | p -value | Normal weight / underweight, (%) a | Overweight/obese, n (%) a | p -value | |

| Number of participants | 74 (100) | 38 (100) | 36 (100) | 40 (100) | 13 (100) | ||

| Nose blowing | 0.214 | 0.336 | |||||

| Yes, daily | 37 (50) | 18 (48) | 19 (53) | 23 (57) | 7 (54) | ||

| Yes, often | 8 (11) | 2 (5) | 6 (17) | 3 (7) | 3 (23) | ||

| Yes, sometimes | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | ||

| Yes, rarely | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Yes, only during colds | 3 (4) | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | ||

| No / not reported | 23 (31) | 16 (42) | 7 (19) | 12 (30) | 3 (23) | ||

| Nasal rinsing | 0.719 | 0.664 | |||||

| Yes, daily | 21 (28) | 8 (21) | 13 (36) | 12 (30) | 4 (31) | ||

| Yes, often | 11 (15) | 5 (13) | 6 (17) | 6 (15) | 2 (15) | ||

| Yes, sometimes | 6 (8) | 4 (11) | 2 (6) | 5 (12) | 0 (0) | ||

| Yes, rarely | 3 (4) | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (8) | ||

| Yes, only during colds | 4 (6) | 2 (5) | 2 (6) | 2 (5) | 1 (8) | ||

| No / not reported | 29 (39) | 17 (45) | 12 (32) | 14 (35) | 5 (38) | ||

| Inhalations for the upper airways | 0.374 | 0.146 | |||||

| Yes, daily | 13 (18) | 3 (8) | 10 (28) | 6 (15) | 0 (0) | ||

| Yes, often | 4 (5) | 2 (5) | 2 (6) | 3 (7) | 0 (0) | ||

| Yes, sometimes | 3 (4) | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | 1 (8) | ||

| Yes, rarely | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | ||

| Yes, only during colds | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| No / not reported | 53 (72) | 31 (82) | 22 (60) | 28 (70) | 12 (92) | ||

| Upper airways inhalation with saline | 11 (15) | 2 (5) | 9 (25) | 0.461 | - | ||

| Isotonic (0.9% sodium chloride) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | ||

| Hypertonic (>0.9% sodium chloride) | 9 (12) | 2 (5) | 7 (19) | 6 (15) | 0 (0) | ||

| Upper airways inhalation with other medication | 5 (7) | 3 (8) | 2 (6) | 4 (10) | 1 (8) |

a BMI was available for 53 participants. BMI categories were based on the World Health Organization (WHO) 2007 standards, using BMI in kg/m2 for adults (underweight <18.5, normal weight ≥18.5 to <25, overweight ≥25.0 to <30, obesity ≥30.0 to <35), and calculating BMI z-scores based on the WHO references for children (thinness <–2 z-scores, normal weight –2–1 z-scores, overweight 1–2 z-scores, obesity >2 z-scores).

Table S5Lower airway physiotherapy practices of people with primary ciliary dyskinesia in Switzerland, overall, by sex (n = 74), and BMI categories (n = 53).

| Total, n (%) | Female. n (%) | Male, n (%) | p -value | Normal weight / underweight, (%) a | Overweight/obese, n (%) a | p -value | |

| Number of participants | 74 (100) | 38 (100) | 36 (100) | 40 (100) | 13 (100) | ||

| Airway clearance techniques | 0.130 | 0.119 | |||||

| Yes, daily | 21 (28) | 8 (21) | 13 (36) | 13 (32) | 2 (16) | ||

| Yes, often | 8 (11) | 1 (3) | 7 (19) | 2 (5) | 3 (23) | ||

| Yes, sometimes | 13 (18) | 7 (18) | 6 (17) | 7 (17) | 5 (38) | ||

| Yes, rarely | 5 (7) | 3 (8) | 2 (6) | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | ||

| Yes, only during colds | 2 (3) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | ||

| No / not reported | 25 (33) | 17 (45) | 8 (22) | 13 (33) | 3 (23) | ||

| Use of aid for airway clearance | 0.423 | 0.202 | |||||

| Flutter | 14 (19) | 7 (21) | 7 (18) | 5 (12) | 2 (15) | ||

| PEP | 3 (4) | 2 (8) | 1 (2) | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | ||

| Flutter and PEP | 5 (7) | 4 (8) | 1 (6) | 4 (10) | 1 (8) | ||

| Blow in straw/nozzle | 3 (4) | 2 (5) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | ||

| Vibrating device | 2 (3) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | ||

| No / not reported | 47 (63) | 21 (55) | 26 (72) | 25 (63) | 9 (69) | ||

| Inhalation for the lower airways | |||||||

| Daily | 36 (49) | 17 (45) | 19 (53) | 0.550 | 21 (53) | 8 (62) | 0.643 |

| Often | 4 (5) | 2 (5) | 2 (6) | 3 (7) | 0 (0) | ||

| Sometimes | 6 (8) | 3 (8) | 3 (8) | 5 (12) | 1 (8) | ||

| Only during colds | 2 (3) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | ||

| No / not reported | 26 (35) | 14 (37) | 12 (33) | 10 (25) | 4 (30) | ||

| Lower airways inhalation with saline | 0.316 | 0.393 | |||||

| Yes | 35 (47) | 17 (58) | 18 (42) | 23 (58) | 5 (38) | ||

| Isotonic (0.9% sodium chloride) | 4 (5) | 1 (4) | 3 (6) | 3 (8) | 0 (0) | ||

| Hypertonic (>0.9% sodium chloride) | 31 (42) | 16 (54) | 15 (36) | 20 (50) | 5 (38) | ||

| Lower airways inhalation with other medication | 28 (38) | 15 (39) | 13 (36) | 15 (38) | 8 (62) | ||

| Difficulty of clearing lower airways | 0.188 | 0.181 | |||||

| Easy | 42 (57) | 20 (53) | 22 (61) | 21 (53) | 9 (70) | ||

| Difficult | 19 (26) | 8 (21) | 11 (31) | 14 (35) | 2 (15) | ||

| I don’t know / not reported | 13 (17) | 10 (26) | 3 (8) | 5 (12) | 2 (15) |

a BMI was available for 53 participants. BMI categories were based on the World Health Organization (WHO) 2007 standards, using BMI in kg/m2 for adults (underweight <18.5, normal weight ≥18.5 to <25, overweight ≥25.0 to <30, obesity ≥30.0 to <35), and calculating BMI z-scores based on the WHO references for children (thinness <–2 z-scores, normal weight –2–1 z-scores, overweight 1–2 z-scores, obesity >2 z-scores).

Table S6Nutritional information of people with primary ciliary dyskinesia in Switzerland, overall, and by sex (n =74).

| Total, n (%) | Female, n (%) | Male N (%) | p -value | |

| Number of participants | 74 (100) | 38 (100) | 36 (100) | |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 22.1 (19.7–24.5) | 21.9 (19.2–24.0) | 0.389 | |

| BMI z-score, median (IQR) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | ||

| BMI categories | 0.863 | |||

| Thinness/underweight | 3 (4) | 1 (3) | 2 (6) | |

| Normal weight | 37 (50) | 20 (53) | 17 (47) | |

| Overweight | 10 (14) | 5 (13) | 5 (14) | |

| Obesity | 3 (4) | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | |

| Missing | 21 (28) | 9 (24) | 6 (17) | |

| Physician recommendation to increase caloric intake by | ||||

| Energy-dense food | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | |

| Larger meal portions | 3 (4) | 1 (3) | 2 (6) | |

| Increased meal frequency | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | |

| Use of hypercaloric drinks in the past 12 months | ||||

| Yes | 5 (7) | 1 (3) | 4 (11) | |

| Weight gained/stabilised due to increased caloric intake | ||||

| Yes | 3 (5) | 1 (4) | 2 (6) | |

y: years. BMI: body mass index. All characteristics are presented as n and column % with the exception of BMI and BMI z-score presented as median and IQR: interquartile range.

BMI was available for 28 females and 25 males. BMI categories were based on the World Health Organization (WHO) 2007 standards, using BMI in kg/m2 for adults (underweight <18.5, normal weight ≥18.5 to <25, overweight ≥25.0 to <30, obesity ≥30.0 to <35), and calculating BMI z-scores based on the WHO references for children (thinness <–2 z-scores, normal weight –2–1 z-scores, overweight 1–2 z-scores, obesity >2 z-scores).