Figure 1 Monte Carlo simulation based on number of patients with paediatric chronic pain (PCP) in the last 7 days.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/SMW.2022.w30194

Paediatric chronic pain (PCP) is an important public health issue, with prevalence estimates ranging from 11% to 38% worldwide [1]. It is defined as ongoing or recurrent pain for more than 3 months, associated with significant emotional distress or functional limitations [2]. Although chronic pain is frequently experienced in paediatric populations, it remains an under-recognised and undertreated condition [3]. Untreated chronic pain in childhood is associated with a higher risk for pain and psychological disorders later in life [4].

The recent inclusion of chronic pain as a diagnostic entity in the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11) [2, 5] may increase the recognition of the importance of PCP. Irrespective of the exact origin, PCP is best conceptualised in the biopsychosocial model, integrating biological or somatic, psychological and sociocultural factors that contribute to the development and maintenance of chronic pain, and that are important for its treatment [6–8]. Given the risk of reduced physical and psychosocial functioning [9–11] and poorer quality of life of children and adolescents with chronic pain [12–14], as well as the economic impact [15] associated with the condition, early detection and treatment of PCP is highly relevant and minimises adverse outcomes. A few longitudinal studies have shown that unresolved PCP in childhood can lead to increased pain-related morbidity and additional pain locations in adulthood [16]. Further, in adult populations with chronic pain, around 17% retrospectively report a history of chronic pain in childhood and adolescence, with almost 80% indicating that pain persisted through childhood into adulthood [4, 17, 18].

In Switzerland, little is known about the current prevalence of PCP, both in the general and clinical population. Data from the Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC) study yielded a high prevalence rate of self-reported chronic pain in 11- to 15-year-olds in Switzerland: 56% of adolescents declared monthly or more frequent headaches, 48% reported back-ache and 61.5% stomach-ache [19]. Most children with PCP are not treated in an inpatient setting, but are rather cared for by primary care paediatricians. Patients treated in specialised pain clinics report a mean pain duration of 24 months before they were referred to the clinic [20]. To the best of our knowledge, our study was the first to assess the prevalence of PCP presenting in primary care practices and institutions in Switzerland. Our aim was to estimate the prevalence of PCP, to assess paediatricians’ professional experience of and confidence with, and care provision for patients with PCP, and investigate associated sociodemographic and professional factors.

This was a cross-sectional online survey of all Swiss paediatricians registered with the Swiss Society of Paediatrics (SSP), the largest national professional organisation for paediatricians. The target sample was clinically active paediatricians. At the time of the survey, the SSP had approximately 2500 members. Paediatricians in training or retired were excluded, as far as this information was available in the registration data. The final mailing list contained the email addresses of 1595 paediatricians. The study was exempt from a full ethical review by the ethics commission of Zurich, Switzerland (Project ID: 2019-00111). As this project was part of a Master thesis (by MC), the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) at the University of Tromsø, Norway, evaluated the study proposal, questionnaire and invitation letters with regard to European data security regulations. The data collection took place over the course of 7 weeks between March and April 2019 with an online questionnaire using Questback’s UniPark tool [21]. The participants received two reminder emails.

The questionnaire was developed by the authors (HK, CL, JD, AW, MC and JK), with backgrounds in paediatrics, public health, and psychology. It was generated in German and translated into French and Italian by a professional translation office, and edited by paediatricians fluent in either language.

The questionnaire (see supplements 1, 2 and 3 in the appendix) asked for data on sociodemographic and professional characteristics, as well as information on paediatricians’ current workplace (i.e., primary care or hospital), date of receiving paediatric board certification, whether they worked full time or part-time, number of patients treated per 3 months (categorical answers <250, 250–500, 500–750, 750–1000, 1000–1500, >1500) and if other professionals (such as physiotherapists or psychologists) worked in the same practice.

Questions regarding PCP started with a definition of PCP (i.e., pain that persists or recurs for at least 3 months; see appendix) and assessed the perceived prevalence of children with chronic pain among their patients at their current workplace (categorial answers <1%, 1–5%, 5–10%, 10–20%, >20%) and number of children with PCP seen in the last 7 working days. Further, we asked about their experience with treating PCP, whether they feel confident in treating PCP, and previous training in PCP-specific diagnosis and treatment. Finally, we asked about the applied diagnostic tools (specifically related to the measurement of pain intensity), referral of children with PCP to other specialists or pain clinics, and reasons for not referring children with PCP.

In addition, we used a case vignette to qualitatively assess pain concepts of participants. These results will be reported elsewhere.

The characteristics of the study sample and referral patterns of patients with PCP to other medical specialists or specialised pain clinics were summarised using descriptive statistics. Exploratary logistic regression analyses were run to explore associations between sociodemographic and professional factors with paediatricians’ confidence and experience in treating patients with PCP. Outcome variables measured with Likert scales were dichotomised for the purpose of the logistic regression. Participants indicating that they feel confident or are more likely to feel confident treating patients with chronic pain were coded as "confident" and participants answering "partly true", "rather not true" were defined as "not confident". Similarly, for experience with the treatment of PCP, "a lot of experience" and "much experience" were defined as "experienced", while "some experience", "little experience" or "no experience" were recoded as "inexperienced". The 20 participants answering “I do not know” to any of the outcomes were excluded from the respective analysis. They did not differ significantly from the others, neither with respect to sex, age or year of passing the board examination, nor regarding their work place. All models controlled for age, gender and language region. The following covariates were sequentially included into the model and kept if the p-value was ≤0.20: workload, prevalence of PCP in practice, training and experience in PCP management and treatment, and year of specialisation.

The prevalence of patients with PCP in paediatric practices was estimated for all participants who reported working in a “single practice” or “group practice” based on the reported number of patients per 3 months (the open-ended category of ≥1500 patients was limited to 1999), and the number of patients with PCP seen in the last 7 days, both extrapolated to a year. Using ordinary least square regression analyses, and applying bootstrapping to account for small sample sizes, we estimated the number of patients and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs), and extrapolated the result to the number of patients seen per quarter or per year, respectively. Additionally, we ran Monte Carlo simulations [22] based on the reported number of patients seen per 7 days (deemed to be representative of a normal working week of the participants), mean values and variance after ordinary least square regression, and a random number of patients per 3 months within the given category assuming a normal distribution. The Monte Carlo simulation method uses a automatised random sampling of the available information and simulates possible outcomes given the uncertainty of the data. In total, 5000 simulations were performed. All analyses were performed in Stata 15 [23].

We invited 1595 members of the Swiss Society of Paediatrics (SSP), of whom 412 opened the online questionnaire. All information was anonymised and answers of 337 paediatricians were included in the analyses. See supplementary figure S1 in the appendix for the flow chart of study participation. More than two thirds of the participants were female (70.6%) and between 36 and 45 years of age (42.7%). About a third of the participants had received their specialist title in the past 10 years at the time of data collection (i.e., between 2008 and 2018), whereas two thirds had held their specialist title for more than 10 years. The majority of participants worked in the German-speaking part of Switzerland, followed by the French- and Italian-speaking parts. The majority worked in single paediatrician or group practices (table 1). Of these, the majority estimated a ≤5% prevalence of patients with PCP in their own practice (<1% prevalence 35.6% of participants; 1–5% prevalence 35.6% of participants; table 1). Higher prevalence categories were less frequently reported: >5–10% by 13.9% of participants, >10–20% by 4.7% of participants, and >20% by 3.2% of participants (table 1).

Table 1Sociodemographic and work-related characteristics of the sample (n = 337).

| N | % | ||

| Gender | Female | 238 | 70.6 |

| Male | 99 | 29.4 | |

| Age category | ≤35 years | 21 | 6.2 |

| 36–45 years | 144 | 42.7 | |

| 46–55 years | 109 | 32.2 | |

| 56–65 years | 59 | 17.5 | |

| >65 years | 4 | 1.2 | |

| Year of specialisation | 1980–1989 | 22 | 6.5 |

| 1990–1999 | 78 | 23.1 | |

| 2000–2009 | 119 | 32.3 | |

| 2010–2019 | 118 | 35 | |

| Language region of workplace* | German-speaking | 211 | 62.6 |

| French-speaking | 113 | 33.5 | |

| Italian-speaking | 19 | 5.3 | |

| Workplace* | Single practice | 54 | 16 |

| Group practice | 171 | 50.7 | |

| University hospital | 70 | 20.8 | |

| Cantonal hospital | 64 | 19 | |

| Regional hospital | 23 | 6.8 | |

| Other | 19 | 5.6 | |

| No. of patients seen quarterly (n = 209) | <205 patients | 27 | 12.9 |

| 250–500 patients | 51 | 24.4 | |

| 500–750 patients | 48 | 23.0 | |

| 750–1000 patients | 42 | 10.1 | |

| 1000–1500 patients | 35 | 16.7 | |

| >1500 patients | 6 | 2.9 | |

| Other professionals in practice (n = 214) | Paediatrician | 145 | 67.8 |

| Psychologist | 33 | 15.4 | |

| Physiotherapist | 15 | 7.0 | |

| Occupational therapist | 5 | 2.3 | |

| Medical specialist (other area) | 37 | 17.3 | |

| Not applicable | 45 | 21.0 | |

*Multiple answers possible

There was no statistically significant difference between gender or language of paediatricians regarding their assessment of prevalence rate. Paediatricians reported to have seen a total of 322 children or adolescents with PCP in the last week across all participants (i.e., single and group practice), corresponding to 1.6 patients with PCP per paediatrician (standard deviation [SD] 2.21) per week. In total, 60% of participants agreed that this number corresponds to the average number of patients with PCP seen during a normal week, whereas 26.2 % felt the number was below average and 14% above average (table 2).

Table 2Number of patients with paediatric chronic pain (PCP) seen and estimation of PCP prevalence.

| Number of patients with PCP seen in the last 7 days (n = 203) | Mean = 1.58 (SD = 2.21); sum over all pediatricians = 322 | ||

| N | % | ||

| Number of patients with PCP seen in the last 7 days: representative? (n = 205) | Yes | 124 | 60.5 |

| No, higher than average | 30 | 14.6 | |

| No, lower than average | 51 | 24.9 | |

| Estimated prevalence of patients with PCP (n = 205) | <1% | 78 | 38.1 |

| 1 to 5% | 80 | 53.9 | |

| > 5 to 10% | 24 | 11.7 | |

| > 10 to 20% | 8 | 3.9 | |

| > 20% | 3 | 1.5 | |

| No patients with PCP | 12 | 5.8 | |

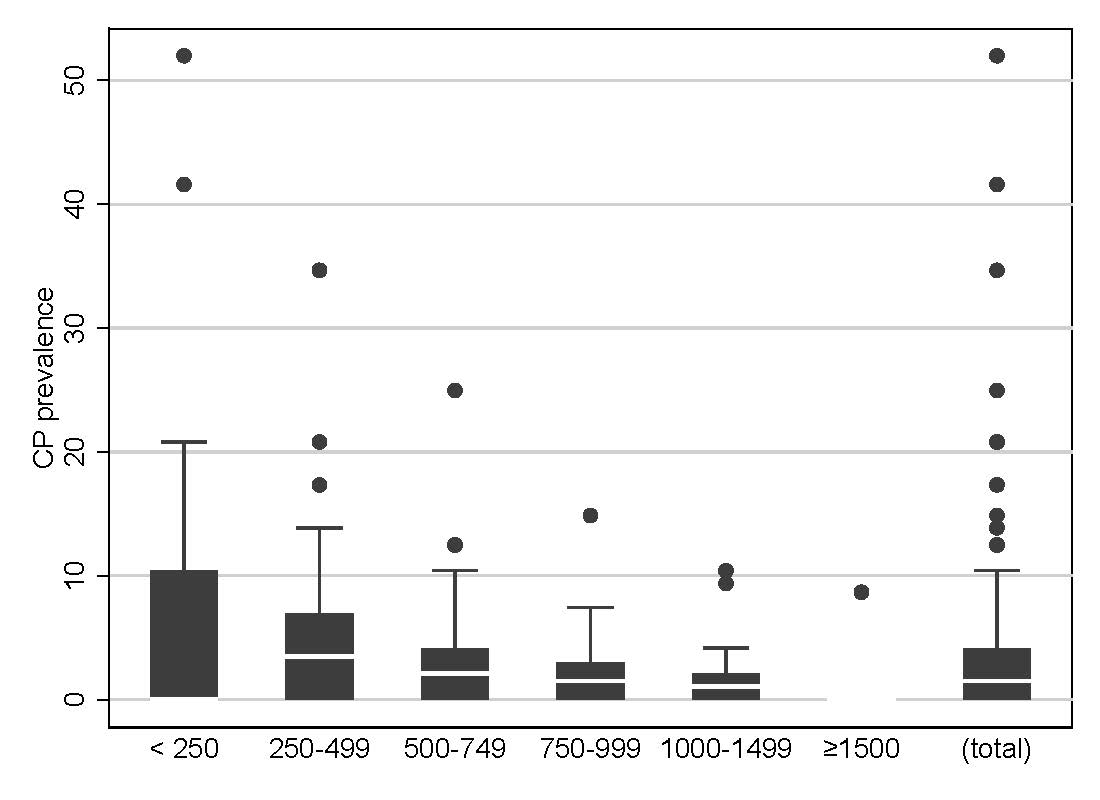

The Monte Carlo simulation estimated a mean number of 3.6 patients with PCP in the last 7 days, indicating 5194 patients with PCP per 3 months, and 20,777.6 per year, across single and group practices. Figure 1 shows the Monte Carlo simulations based on the number of patients with PCP in the last 7 days for those who considered this number to be representative.

Figure 1 Monte Carlo simulation based on number of patients with paediatric chronic pain (PCP) in the last 7 days.

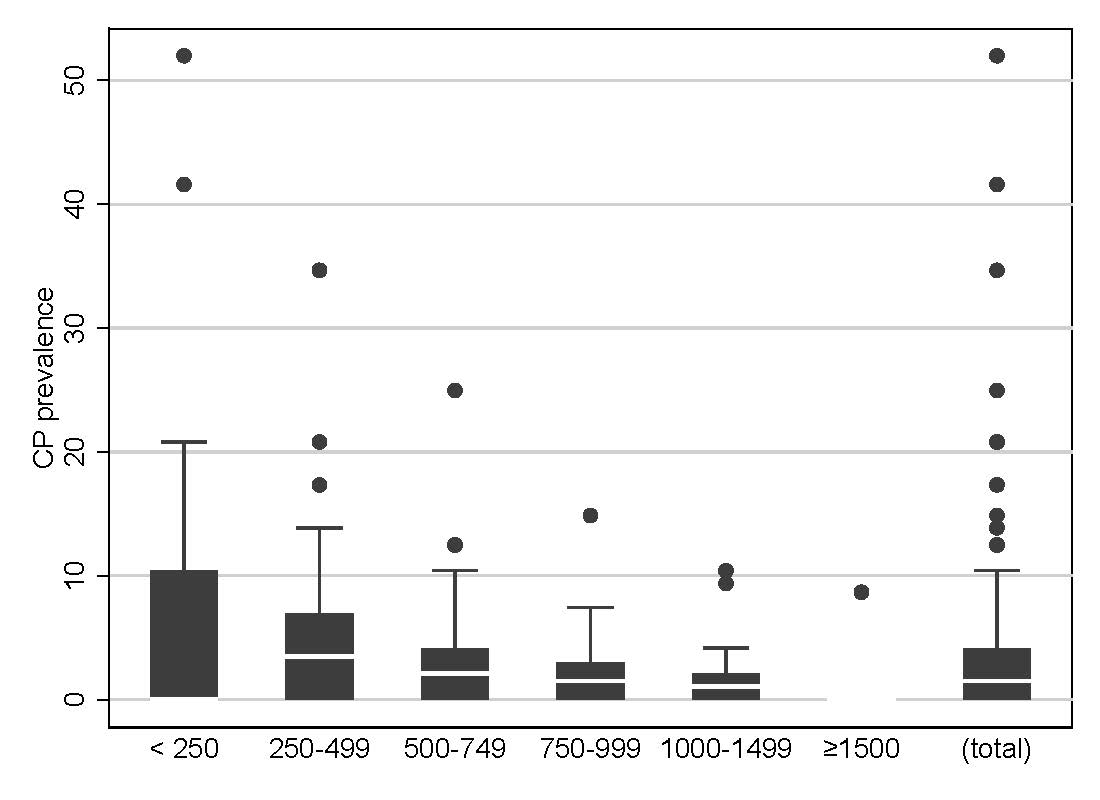

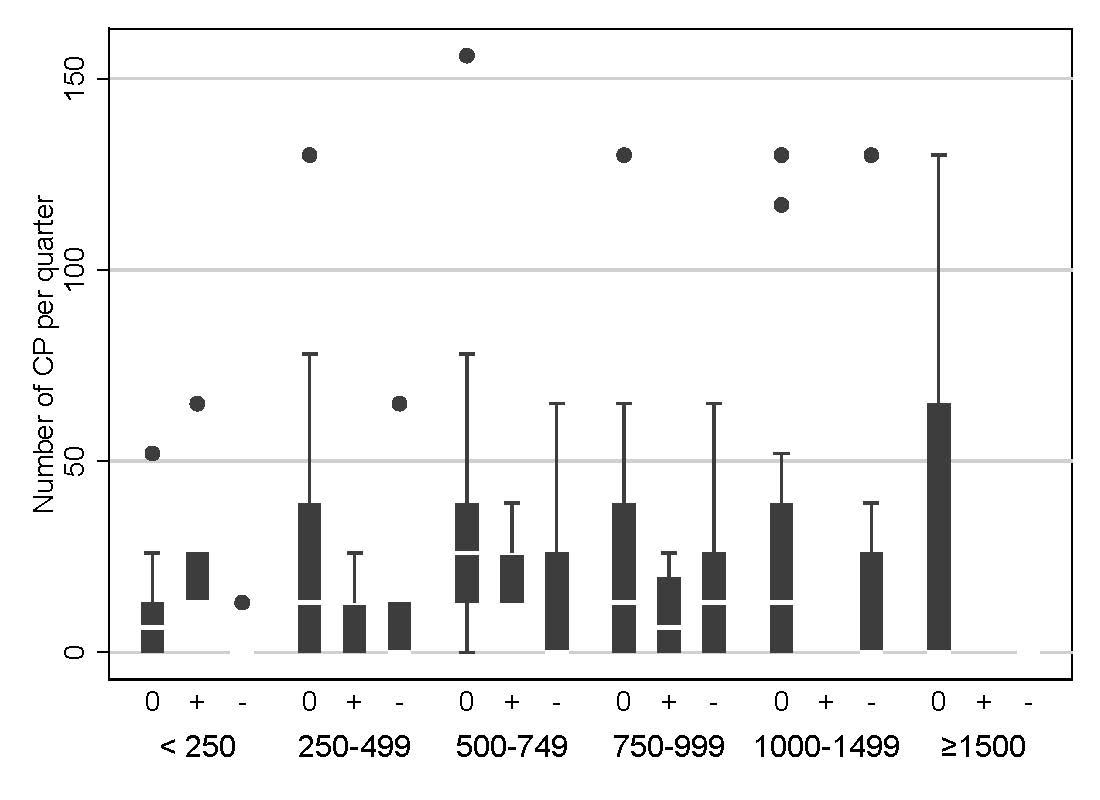

Figure 2 displays the Monte Carlo simulation based on the number of patients with PCP seen quarterly, calculated from the response to the categorical options (0–250, 250–500, 500–750, 750–1000, 1000–1500, >1500) and taking either the minimum, average or maximum value of each category. For the lowest category (<250 children seen in 3 months), 1 is used in the calculation of minimum sum. In the highest category (>1500 children seen in 3 months), 1999 was assumed to be the upper value.

Figure 2 Monte Carlo simulation based on the number of patients with paediatric chronic pain (PCP) seen quarterly.

Almost a fifth of the participants reported having "a lot of experience" or "much experience" in working with patients with PCP (a lot of experience = 2.5%, much experience = 16.4%), 39.7% had some experience and 41.3% considered themselves inexperienced (little experience 34.7%, no experience 6.6%). The statement “I feel confident when treating children with chronic pain” (i.e., number of participants who responded “applies” or “more likely to be true”) was endorsed by 20.5% of participants. Most participants reported not having received training specifically for PCP diagnosis and treatment (“no” = 78.5%, “don’t know” = 3.2%, “yes” = 18.3%). The explorative logistic regressions yielded gender differences regarding feeling confident with the treatment of PCP, with men having more than three times higher odds (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 3.33, 95% CI 0.01) of reporting “I feel confident when treating patients with chronic pain” compared with women (table 3). With regard to the outcome “experience”, logistic regressions yielded the following factors as significant: paediatricians’ estimated prevalence, increasing subjective experience with increasing prevalence, and time since board certification. For example, paediatricians who reported a 1–5% prevalence of PCP had 10 times higher odds of feeling experienced in the treatment of PCP compared with those who estimated a prevalence rate of <1% (reference category). Paediatricians who received their board certificate between 1990 and 1999 (AOR 13.5, 95% CI 1.679–108.940; p <0.014), or 2000 and 2009 (AOR 13.7, 95% CI 1.313–141.938; p <0.029) had a higher AOR for reporting experience with PCP treatment compared with those who received their board certification in the years between 1980 and 1989 (reference category; table 3).

Table 3Factors associated with confidence and experience in treating patients with paediatric chronic pain (PCP) (n = 294).

| Adjusted odds ratio | 95% CI | p -value | |||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Confidence a | |||||

| Gender | Female | Reference category | |||

| Male | 3.33 | 1.33 | 8.35 | 0.01* | |

| Experience | Unexperienced | Reference category | |||

| Experienced | 11.05 | 4.67 | 26.15 | <0.001* | |

| Experience b | |||||

| Estimated prevalence of PCP | <1% | Reference category | |||

| 1–5% | 10.31 | 2.74 | 38.74 | <0.001* | |

| 5–10% | 36.3 | 8.94 | 147.34 | <0.001* | |

| 10–20% | 50.71 | 9.21 | 279.16 | <0.001* | |

| >20% | 181.14 | 22.33 | 1469.5 | <0.001* | |

| Year of receiving specialist title | 1980–1989 | Reference category | |||

| 1990–1999 | 13.53 | 1.68 | 108.94 | 0.014* | |

| 2000–2009 | 13.65 | 1.31 | 141.94 | 0.029* | |

| 2010–2019 | 9.4 | .75 | 117.23 | 0.082 | |

*Significant at <0.001

a Model covariates: gender, age, language region, workload, prevalence of PCP in practice, training and experience in PCP management and treatment

b Model covariates: gender, age, language region, prevalence of PCP in practice, year of specialisation

All the other model covariates yielded nonsignificant associations with experience and confidence in the treatment of PCP.

Table S2 in the appendix shows the referral patterns of participants. Three quarters of participants had referred a patient with PCP to other specialists, with a mean of 5.3 children per participant being referred and an overall sum across participants of 1217 patients in the last year. Almost two thirds of participants had never referred a patient with PCP to a pain outpatient clinic specialised in children and adolescents. Those who had, had referred a mean of 2.1 children in the past year (total 233). Nine out of ten participants considered a pain outpatient service specialised in children and adolescents a therapeutic option for patients with PCP. Of those who did not, almost half did not know about any pain outpatient services, 16.7% found them to be too far away for their patients and a third answered that they had enough therapeutic resources themselves. Further reasons for non-referral included: there was no such service in the providers’ catchment area; they did not approve of the methods used by the ambulatory pain services; and they thought patients with PCP should be treated as normal paediatric patients. Participants who had referred patients with PCP most often referred them to other paediatric specialists, among whom gastroenterology and hepatology (n = 119), neuropaediatrics (n = 115), and orthopaedics (n = 99) were the most common. In addition, patients had been referred to other, non-paediatric pain specialists, specialists in internal medicine, rheumatology, neurology, psychiatry or anaesthesia. Many participants had also referred patients to hypnotists, acupuncturists and practitioners of alternative medicine.

This study was designed to explore PCP prevalence and current PCP care management in paediatric primary care practices in Switzerland. The question regarding care management encompasses paediatricians’ professional experience and confidence with, as well as care for, patients living with PCP. PCP is an important public health problem, with possible life-long consequences, affecting individuals, families and society directly and indirectly [15, 24–26]. In our study, based on the number of patients with PCP and the number of patients seen by paediatricians, we estimated an average PCP prevalence rate of 3.62% in single and group practices across Switzerland. This corresponds with the direct estimation of PCP prevalence reported by paediatricians participating in this survey. In contrast, the self-reported population data available in Switzerland indicates a much higher prevalence rate of up to 20% for the age range 11–15 years, depending on age group and gender [19]. Systematic estimates from the international literature range around 25% [1]. An epidemiological study from Germany estimated that 13% of children suffer from chronic pain [27], one from the Netherlands found prevalence rates as high as 25% [28], and rates were 44% in an international study using self-reported data [29]. This indicates that the prevalence rate based on assessment of paediatricians in our sample might significantly underestimate the actual number of affected children and adolescents, suggesting in substantial underreporting of PCP. Prevalence differences might partially be due to methodological differences (e.g., assessment and definition of PCP). Importantly, prevalence rates of many PCP conditions increase with age [1, 28, 30]. However, in our survey, we did not differentiate between children and adolescents when we asked paediatricians about the number of patients with PCP seen in their practice. Adolescents are seen by pediatricians less frequently than children, presumably because of fewer recommended visits or because they have been transitioning to a general practitioner. The accessibility to paediatricians differs across Switzerland, with low access in rural areas, which makes primary healthcare services provided by general practitioners important for these adolescents.

In terms of the current state of PCP care management, our results suggest that most Swiss paediatricians do not feel confident about treating children and adolescents with chronic pain. This is in line with an earlier study that showed self-rated confidence of paediatricians to be lowest when confronted with musculoskeletal complaints, including pain, compared with other body systems [31]. Notably, we found significant predictors in our data: having more experience with PCP and being of male gender were associated with an increased feeling of confidence in treating PCP. However, from a gender perspective, one could speculate whether this finding is a true difference between male and female paediatricians, or rather the result of a gendered self-confidence bias [32]. Overall, only very few paediatricians reported feeling experienced in PCP management.

Regarding why most paediatricians do not feel confident with the treatment of PCP, two additional findings of our study might be informative: first, the vast majority of participants reported that they received no training in PCP diagnosis and treatment; second, paediatricians reported a lack of knowledge of referral possibilities. This is concerning, especially because in our sample, about a third of the participants received their specialist title in the last 10 years, indicating that current medical training still does not incorporate these topics enough. Training could be offered in the form of short courses for medical students, as well as in the form of continuing professional development and workshops for practising paediatricians. Recently, a group of pain researchers developed a multidisciplinary pain education curriculum for paediatric residents in the US and found that upon completion of the training, residents indicated increased knowledge of the conceptualisation and management of pain, and feeling more confident with the topic [33]. In general, treatment for PCP should be improved by an evidence-based focus on diagnostic classification and assessment, as well as knowledge of treatment options, benefits, and harm reduction. National or international registries of children and adolescents treated for chronic pain would facilitate the exchange of experiences with PCP management [34].

Our study reveals that one significant barrier to paediatricians initiating referrals to pain outpatient clinics is that they are not aware of the services offered in Switzerland. They therefore do not refer patients to pain clinics, but rather to different professionals, most frequently to paediatricians specialised in the fields of gastroenterology and hepatology, neuropaediatrics and orthopaedics. Research indicates that, generally, the choice of referrals is associated with the most frequent differential diagnoses of chronic pain, namely headaches, abdominal pain syndromes, and musculoskeletal and joint pain [4]. In addition to referral to other medical specialists, participating paediatricians in our study also regularly referred patients with PCP to psychologists. On the one hand, this could be a good indicator of the presence of an interprofessional approach to PCP treatment in Switzerland. On the other hand, this might point to a potential conceptualisation of PCP as being shaped by primarily psychological factors, rather than the evidence-based biopsychosocial conceptualisation. Further, according to our findings, non-referral to paediatric pain outpatient clinics and services were also attributed to patients’ burden related to prolonged travel time. The four paediatric pain clinics in Switzerland are all in hospitals in urban areas. Research indicates that barriers such as time conflicts, transportation, treatment efficacy concerns and fear of pain can hinder families seeking specialised treatment [35].

The introduction of the ICD-11 will allow a more systematic assessment of PCP in the future: The classification system offers seven different diagnostic entities for chronic pain, among them chronic primary pain, i.e., pain in one or more anatomic regions that persists or recurs for 3 or more months and is associated with significant emotional distress and/or functional limitations [2, 5]. The inherent reconceptualisation of chronic pain that comes with the ICD-11 might help to strengthen a biopsychosocial approach to the diagnosis and the management of PCP across disciplines [36]. In addition, it is thought to support clinicians in having a helpful conversation with patients and their families about the origins of their pain and its treatment [37]. Importantly, though, the ICD-11 diagnostic categories have yet to be validated in paediatric samples [38].

This is the first study to investigate PCP in a population of Swiss general paediatricians and to provide first prevalence estimates for Switzerland. The response rate of approximately 20% is low; however, given the clinician workload, no reimbursement for study participation and the nonpersonal invitation, it is considered decent. It is in fact likely that the response rate was underestimated, since the address list was not accurate and recently retired paediatricians were included in the address list, but not eligible for our survey. The exact number could not be ascertained. Given the variance in participants’ experience and number of patients with PCP seen, alongside the fact that the three major language regions and a large age range and both male and female paediatricians were included in our sample, we do not suspect participation bias.

To date, we are aware of only one previous study, from the UK [39], that has investigated the prevalence of chronic pain in children with a questionnaire sent to paediatric practices. Therefore, we could not use a validated questionnaire or validated questions in the study. The questionnaires were developed specifically for this study by a multidisciplinary group of public health, paediatric, and psychological pain experts and pilot-tested on a small sample of paediatricians. Further, our study was not designed to estimate PCP in the overall population, but rather to gather preliminary information on prevalence estimates among paediatricians, as our results are based on a crude estimation method (i.e., the perceived prevalence of PCP). We therefore recommend that future studies include billing codes or rely on a representative sample of practices to prospectively capture chronic pain diagnoses based on the ICD-11 pain classification. Finally, it needs to be acknowledged that all our data are based on self-report and might therefore come with all biases associated with it.

This study was conducted as a first attempt to fill the data gap on the prevalence rate of PCP in Switzerland, and to gain a better understanding of the current state of care provision and professional experiences among Swiss paediatricians. The results highlight a much lower-than-expected prevalence, lack of experience and training of paediatricians, and hence low confidence to treat patients with PCP. This may be related to an under-recognition of PCP, especially as compared with prevalence data from other countries. Our study can contribute to a better recognition of the work that still needs to be done regarding the development of adequate identification, diagnosis, and treatment of PCP in Switzerland. Suggestions for future research include longitudinal studies based on ICD-11 diagnosis codes and cross-sectional representative studies in all age groups on self-reported PCP, which should be conducted to establish a Swiss national database for prevalence and diagnoses.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

1. King S , Chambers CT , Huguet A , MacNevin RC , McGrath PJ , Parker L , et al. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. Pain. 2011 Dec;152(12):2729–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.016

2. Treede RD , Rief W , Barke A , Aziz Q , Bennett MI , Benoliel R , et al. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain. 2015 Jun;156(6):1003–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000160

3. Palermo TM , Wilson AC , Peters M , Lewandowski A , Somhegyi H . Randomized controlled trial of an Internet-delivered family cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention for children and adolescents with chronic pain. Pain. 2009 Nov;146(1-2):205–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2009.07.034

4. Friedrichsdorf SJ , Giordano J , Desai Dakoji K , Warmuth A , Daughtry C , Schulz CA . Chronic Pain in Children and Adolescents: Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Pain Disorders in Head, Abdomen, Muscles and Joints [Internet]. Children (Basel). 2016 Dec;3(4):E42. [cited 2019 Feb 6] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5184817/ https://doi.org/10.3390/children3040042

5. Nicholas M , Vlaeyen JW , Rief W , Barke A , Aziz Q , Benoliel R , et al.; IASP Taskforce for the Classification of Chronic Pain . The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic primary pain. Pain. 2019 Jan;160(1):28–37. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001390

6. Gatchel RJ , Peng YB , Peters ML , Fuchs PN , Turk DC . The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull. 2007 Jul;133(4):581–624. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.581

7. Liossi C , Howard RF . Pediatric Chronic Pain: Biopsychosocial Assessment and Formulation. Pediatrics. 2016 Nov;138(5):e20160331. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-0331

8. Stinson J , Connelly M , Kamper SJ , Herlin T , Toupin April K . Models of Care for addressing chronic musculoskeletal pain and health in children and adolescents. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2016 Jun;30(3):468–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2016.08.005

9. Fisher E , Heathcote LC , Eccleston C , Simons LE , Palermo TM . Assessment of Pain Anxiety, Pain Catastrophizing, and Fear of Pain in Children and Adolescents With Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2018 Apr;43(3):314–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsx103

10. Palermo TM , Lewandowski AS , Long AC , Burant CJ . Validation of a self-report questionnaire version of the Child Activity Limitations Interview (CALI): the CALI-21. Pain. 2008 Oct;139(3):644–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2008.06.022

11. Soltani S , Kopala-Sibley DC , Noel M . The Co-occurrence of Pediatric Chronic Pain and Depression: A Narrative Review and Conceptualization of Mutual Maintenance. Clin J Pain. 2019 Jul;35(7):633–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000723

12. Gold JI , Mahrer NE , Yee J , Palermo TM . Pain, fatigue, and health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2009 Jun;25(5):407–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e318192bfb1

13. Kashikar-Zuck S , Zafar M , Barnett KA , Aylward BS , Strotman D , Slater SK , et al. Quality of life and emotional functioning in youth with chronic migraine and juvenile fibromyalgia. Clin J Pain. 2013 Dec;29(12):1066–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182850544

14. Varni JW , Seid M , Smith Knight T , Burwinkle T , Brown J , Szer IS . The PedsQLTM in pediatric rheumatology: Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Pediatric Quality of Life InventoryTM generic core scales and rheumatology module. Arthritis Rheum. 2002 Mar;46(3):714–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.10095

15. Groenewald CB , Essner BS , Wright D , Fesinmeyer MD , Palermo TM . The economic costs of chronic pain among a cohort of treatment-seeking adolescents in the United States. J Pain. 2014 Sep;15(9):925–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2014.06.002

16. Walker LS , Dengler-Crish CM , Rippel S , Bruehl S . Functional abdominal pain in childhood and adolescence increases risk for chronic pain in adulthood. Pain. 2010 Sep;150(3):568–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.018

17. Hassett AL , Hilliard PE , Goesling J , Clauw DJ , Harte SE , Brummett CM . Reports of chronic pain in childhood and adolescence among patients at a tertiary care pain clinic. J Pain. 2013 Nov;14(11):1390–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2013.06.010

18. Koechlin H , Beeckman M , Meier AH , Locher C , Goubert L , Kossowsky J , et al. Association of parental and adolescent emotion-related factors with adolescent chronic pain behaviors. PAIN [Internet]. 2021 Oct 20 [cited 2021 Oct 28]; Available from: https://journals.lww.com/pain/Abstract/9000/Association_of_parental_and_adolescent.97860.aspx

19. Ambord S , Eichenberger Y , Delgrande Jordan M. Gesundheit und Wohlbefinden der 11-15-jährigen Jugendlichen in der Schweiz im Jahr 2018 und zeitliche Entwicklung. Lausanne; 2020. (Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC)). Report No.: 113.

20. Schneider T , Pfister D , Wörner A , Ruppen W . Characteristics of children and adolescents at the Switzerland-wide first ambulatory interdisciplinary pain clinic at the University Children’s Hospital Basel - a retrospective study. Swiss Med Wkly. 2019 Apr;149:w20073. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2019.20073

21. Questback Gmb H . EFS Survey. Cologne: Questback GmbH; 2019.

22. Thomopoulos NT . Essentials of Monte Carlo Simulation: Statistical Methods for Building Simulation Models. Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. 184 p.

23. StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2017.

24. Eccleston C , Crombez G , Scotford A , Clinch J , Connell H . Adolescent chronic pain: patterns and predictors of emotional distress in adolescents with chronic pain and their parents. Pain. 2004 Apr;108(3):221–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2003.11.008

25. Palermo TM . Impact of recurrent and chronic pain on child and family daily functioning: a critical review of the literature. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2000 Feb;21(1):58–69. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004703-200002000-00011

26. Vos T , Flaxman AD , Naghavi M , Lozano R , Michaud C , Ezzati M , et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012 Dec;380(9859):2163–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2

27. Roth-Isigkeit A , Thyen U , Raspe HH , Stöven H , Schmucker P . Reports of pain among German children and adolescents: an epidemiological study. Acta Paediatr. 2004 Feb;93(2):258–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2004.tb00717.x

28. Perquin CW , Hazebroek-Kampschreur AA , Hunfeld JA , Bohnen AM , van Suijlekom-Smit LW , Passchier J , et al. Pain in children and adolescents: a common experience. Pain. 2000 Jul;87(1):51–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00269-4

29. Gobina I , Villberg J , Välimaa R , Tynjälä J , Whitehead R , Cosma A , et al. Prevalence of self-reported chronic pain among adolescents: evidence from 42 countries and regions. Eur J Pain. 2019 Feb;23(2):316–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1306

30. Stewart WF , Lipton RB , Celentano DD , Reed ML . Prevalence of migraine headache in the United States. Relation to age, income, race, and other sociodemographic factors. JAMA. 1992 Jan;267(1):64–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1992.03480010072027

31. Jandial S , Myers A , Wise E , Foster HE . Doctors likely to encounter children with musculoskeletal complaints have low confidence in their clinical skills. J Pediatr. 2009 Feb;154(2):267–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.08.013

32. Anderson RS , Levitt DH . Gender Self-Confidence and Social Influence: Impact on Working Alliance. J Couns Dev. 2015;93(3):280–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12026

33. Matthews J , Zoffness R , Becker D . Integrative pediatric pain management: Impact & implications of a novel interdisciplinary curriculum. Complement Ther Med. 2021 Jun;59:102721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2021.102721

34. Eccleston C , Fisher E , Cooper TE , Grégoire MC , Heathcote LC , Krane E , et al. Pharmacological interventions for chronic pain in children: an overview of systematic reviews. Pain. 2019 Aug;160(8):1698–707. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001609

35. Simons LE , Logan DE , Chastain L , Cerullo M . Engagement in multidisciplinary interventions for pediatric chronic pain: parental expectations, barriers, and child outcomes. Clin J Pain. 2010 May;26(4):291–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181cf59fb

36. Schechter NL . Functional pain: time for a new name. JAMA Pediatr. 2014 Aug;168(8):693–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.530

37. Koechlin H , Locher C , Prchal A . Talking to Children and Families about Chronic Pain: The Importance of Pain Education-An Introduction for Pediatricians and Other Health Care Providers. Children (Basel). 2020 Oct;7(10):E179. https://doi.org/10.3390/children7100179

38. Matthews E , Murray G , McCarthy K . ICD-11 classification of paediatric chronic pain referrals in Ireland with secondary analysis of primary vs. secondary pain conditions. Pain Med. 2021 Nov;22(11):2533–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnab116

39. Bhatia A , Brennan L , Abrahams M , Gilder F . Chronic pain in children in the UK: a survey of pain clinicians and general practitioners. Paediatr Anaesth. 2008 Oct;18(10):957–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2008.02710.x

The appendix is available in the pdf version of the article.