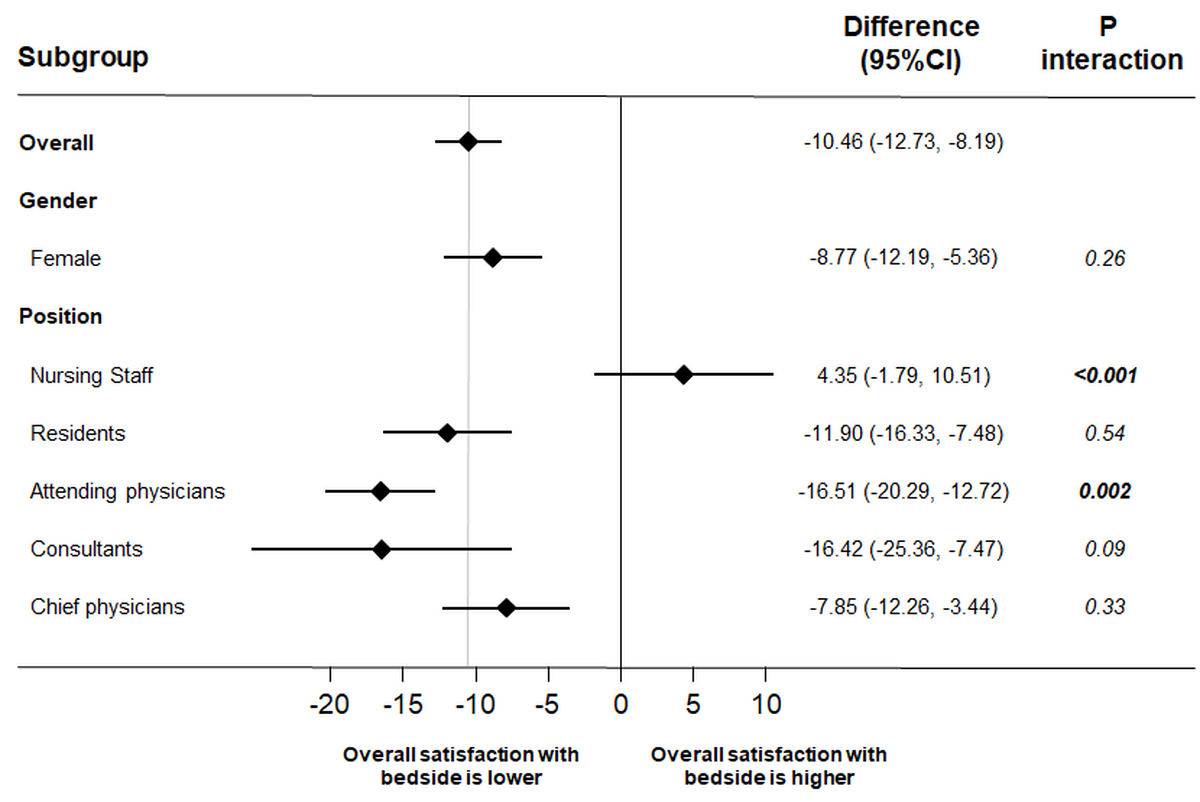

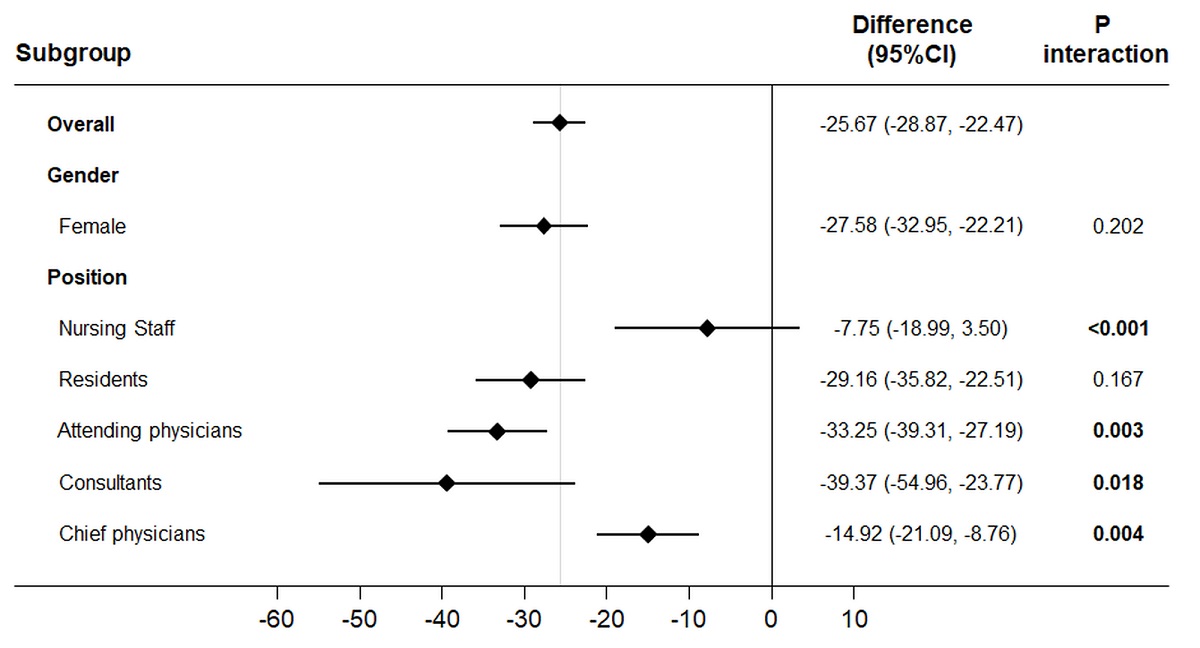

Figure 1 Satisfaction with ward rounds in different subgroups. All differences calculated with multivariate linear regression models for continuous data.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/SMW.2022.w30112

Patient involvement during medical ward rounds is important for patient-centred medicine, since it ensures the direct participation of patients in medical discussions and the decision-making process [1–4]. One element of ward rounds is the exchange of patient-related knowledge among professionals. This exchange can take place at the patients’ bedside or outside the room. As both are currently used in medical practice, depending on the preference of the medical team, a better understanding of patients’, physicians’ and nursing teams’ perceptions and preferences is needed. A systematic literature search and meta-analysis including five randomised controlled trials and 655 participants found no differences between groups regarding patients’ satisfaction and understanding of disease [5]. However, overall trial quality was moderate, and trial sequential analysis indicated power to be low. Recently, our research team conducted a large, randomised controlled trial in three Swiss teaching hospitals to compare effects of presentations at the bedside or outside the room regarding patients’ average knowledge of three dimensions of their medical care: understanding of their disease, the therapeutic approach being used, and plans for future care [6]. Our data indicated that, compared with outside the room case presentation, bedside presentation was shorter and resulted in similar patient knowledge, but sensitive topics were more often avoided and patient confusion was higher. However, similarly to previous studies, we primarily focused on patient outcomes in our initial report. What was lacking, however, was a description of healthcare workers’ perceptions and preferences. This might be an important aspect, since the satisfaction and well-being of physicians have been linked to delivery of higher quality care [7]. One study revealed that nursing staff prefer outside the room over bedside presentations [8]#Wang-Cheng,%201989). Further, there are controversial findings about residents’ and attending physicians’ preferences [8–11]. However, these studies had limited sample sizes. Also, there are no studies from recent years.

Here, as an ancillary project of the BEDSIDE-OUTSIDE trial, we systematically compared satisfaction and preferences of physician and nursing staff concerning bedside versus outside the room ward rounds.

We conducted an ancillary project to the BEDSIDE-OUTSIDE trial [6] looking at physicians’ and nurses’ satisfaction with ward rounds, when comparing beside case discussions with outside the room case discussions. In brief, the initial study was a pragmatic, investigator-initiated, open-label, non-commercial, multicentre randomised controlled trial conducted in the general internal medicine departments of three Swiss teaching hospitals (University Hospital Basel, Cantonal Hospital Aarau and Cantonal Hospital Basel-Land) between July 2017 and October 2019. The study was pre-registered at clinicaltrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03210987) and approved by the local Ethics Committee (Northwest and Central Switzerland, EKNZ, project ID: 2017-00991).

The work-flow of the routine ward rounds was similar in the participating hospitals and comparable to most Swiss and many European hospitals. In addition to daily morning rounds by a resident, and then supervised by an attending physician, “consultant ward rounds” are conducted once a week. Here, a consultant (e.g., the head of service or one of his/her deputies) joins the morning round together with the medical team and the responsible nurse. Patients’ cases are presented to the team by the resident followed by a detailed discussion including diagnostic and therapeutic measures complemented by further plans of care. In our main trial we specifically investigated a patient’s first consultant ward round, which also sets the framework for this ancillary project.

We included consecutive adult patients newly admitted to medical wards for inpatient care who had their first once-a-week consultant ward round. Of all eligible patients only one per room was randomly selected for study inclusion. We excluded patients with cognitive or hearing impairment, patients who were unable to understand the local language(s) and patients who had previously been included in the study. All included patients provided written informed consent.

Patients were randomly assigned to the “bedside group” or the “outside the room group” in a 1:1 ratio stratified for the trial site. In both groups the ward round followed the usual practice in each participating hospital.

In the bedside presentation group, case presentations, discussions and clinical examination took place at the bedside in front of the patient. In the outside the room group, patient case presentation and discussions were primarily held in the hallway, without the patient being present. Afterwards, the team entered the room, the patient was given a short summary of the discussion outside the room, then completed the gathering of medical information, examined the patient as needed, answered questions and discussed the next steps.

Every weekly internal medicine consultant ward round was accompanied by a member of the investigation team collecting the email addresses of all participating healthcare workers. The data collection was implemented using LimeSurvey. Healthcare workers were informed about receiving a link to a survey via email after the ward round assessing their satisfaction, perception and preferences regarding the ward round. We sent individual reminders to participants who did not reply to the survey. There was no detailed description of the purpose of this study to avoid bias.

Patients, study coordinators and treating clinicians were not blinded to allocation. However, study investigators who were involved in a patient’s outcome assessment were blinded to the patient’s trial allocation.

The primary endpoint was staff mean satisfaction with the ward round measured on a visual analogue scale (VAS) of 0–100 with 0 indicating lowest and 100 highest possible satisfaction.

Secondary endpoints included further outcomes regarding satisfaction (i.e. satisfaction with time management, staff team interaction and team-patient interaction), perception of time management during ward round (i.e. sufficient time, being rushed, ward round as planned, ward round terminated on time), perception of how sensitive topics were addressed during ward round (i.e. discussion of sensitive topics, all important matters discussed) and discomfort during ward round (i.e. feeling insecure, feeling uncomfortable, affected, unpleasant incidents), each rated on a VAS 0–100 with 0 indicating lowest and 100 highest possible expression. Further secondary endpoints were preferences within different professions in terms of six ward round related aspects (i.e. being informative for patients, being instructive for staff, economical, efficient, patient comfort, healthcare workers’ comfort) each rated on a VAS 0–100 with 0 indicating bedside preference and 100 outside the room preference.

Additionally, within the survey there was the opportunity to provide qualitative feedback using free text remarks within the survey.

For primary and secondary analyses, staff satisfaction with the ward round was compared between randomisation arms using Student’s t-test. We also calculated multivariable hierarchical models adjusted for age, gender and centre. As some physicians and nurses completed several questionnaires, we used hierarchical regression models to control for participants as a random effect.

We further conducted subgroup analyses within the different professions. We used STATA 15.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA) for all statistical analyses.

Between July 2017 and October 2019, 919 patients were included in the trial and we received 891 responses (nurses: 138 [15.6%], residents 237 [26.8%], attending physicians 261 [29.6%], consultants 69 [7.8%] and chief physicians 178 [20.2%] from a total of 76 nurses, 88 residents, 45 attending physicians, 26 consultants and 9 chief physicians). There were a total of 486 reports of bedside and 405 outside the room ward rounds. Baseline characteristics were similar between groups (table 1). Mean age was 38 years, 35 years among nursing staff, 31 years among residents, 37 among attending physicians, 52 among consultants and 47 among chief physicians. The average professional experience was 12 years, and 51% of the staff were female.

Table 1Characteristics of the participants stratified by location of ward rounds.

| n | All | Outside the room | Bedside | p-value | ||

| n = 891 | n = 405 | n = 486 | ||||

| Work-related factors | Reports on ward rounds, n (%) | 883 | ||||

| Nurses | 138 (15.6%) | 60 (15.0%) | 78 (16.2%) | 0.76 | ||

| Residents | 237 (26.8%) | 112 (27.9%) | 125 (25.9%) | |||

| Attending physicians | 261 (29.6%) | 118 (29.4%) | 143 (29.7%) | |||

| Consultants | 69 (7.8%) | 35 (8.7%) | 34 (7.1%) | |||

| Chief physicians | 178 (20.2%) | 76 (19.0%) | 102 (21.2%) | |||

| Professional experience (years) mean ± SD | 884 | 11.6 ± 9.1 | 11.6 ± 9.2 | 11.6 ± 9.0 | 0.91 | |

| Socio-demographic factors | Age all (years) mean ± SD | 872 | 38.36 ± 9.75 | 38.30 ± 9.75 | 38.41 ± 9.77 | 0.87 |

| Age nurses | 138 | 35.35 ± 12.08 | 35.25 ± 12.08 | 35.42 ± 12.16 | 0.93 | |

| Age residents | 234 | 30.61 ± 2.98 | 30.76 ± 3.03 | 30.48 ± 2.94 | 0.48 | |

| Age attending physicians | 255 | 37.21 ± 5.27 | 37.05 ± 5.07 | 37.34 ± 5.45 | 0.66 | |

| Age consultants | 69 | 51.68 ± 3.83 | 51.63 ± 3.69 | 51.74 ± 4.02 | 0.91 | |

| Age chief physicians | 176 | 46.86 ± 5.26 | 46.99 ± 5.04 | 46.77 ± 5.44 | 0.79 | |

| Gender, n (%) | 881 | 0.53 | ||||

| Female | 451 (51.2%) | 197 (49.1%) | 254 (52.9%) | |||

| Male | 419 (47.6%) | 199 (49.6%) | 220 (45.8%) | |||

| No answer | 11 (1.2%) | 5 (1.2%) | 6 (1.3%) | |||

SD: standard deviation

Descriptive statistics of the sample where n refers to the cumulative number of questionnaires returned.

Univariable regression analyses revealed that mean ± standard deviation (SD)satisfaction of staff members was higher with outside the room than with bedside ward rounds (78.03 ± 16.96 versus 68.25 ± 21.10; difference –10.11, 95% confidence interval [CI] –12.36 to –7.85; p <0.001). These results stayed significant in multivariable analyses adjusted for age, gender and center (adjusted difference of –10.46, 95% CI –12.73 to –8.19; p <0.001) (table 2).

Table 2Primary and secondary outcomes.

| Staff satisfaction with ward round (VAS 0–100) | n all | All (n = 891) | Outside the room (n = 405) | Bedside (n = 486) | p-value | Univariable regression coefficient (95% CI) | p-value | Multivariable regression coefficient (95% CI), adjusted for age, gender, centre | p-value |

| Primary endpoint: Staff satisfaction with ward round (VAS 0100) | |||||||||

| Satisfaction with ward round, mean (SD) | 891 | 72.69 ± 19.92 | 78.03 ± 16.96 | 68.25 ± 21.10 | <0.001 | –10.11 (–12.36, –7.85) | <0.001 | –10.46 (–12.73, –8.19) | <0.001 |

| Secondary endpoints | |||||||||

| Satisfaction with time management of the ward round, mean ± SD) | 889 | 70.03 ± 24.54 | 73.19 ± 23.23 | 67.39 ± 25.32 | <0.001 | –6.16 (–9.06, –3.27) | <0.001 | –6.51 (–9.45, –3.58) | <0.001 |

| Satisfaction with staff team interaction during ward round, mean ± SD) | 888 | 73.65 ± 23.74 | 80.48 ± 19.93 | 67.93 ± 25.15 | <0.001 | –13.05 (–15.69, –10.41) | <0.001 | –13.52 (–16.18, –10.86) | <0.001 |

| Satisfaction with patient interaction during ward round, mean ± SD) | 886 | 74.46 ± 22.34 | 78.31 ± 19.66 | 71.27 ± 23.90 | <0.001 | –7.17 (–9.87, –4.47) | <0.001 | –7.49 (–10.22, –4.76) | <0.001 |

| Staff perception of time management during ward round (VAS 0–100) | |||||||||

| Having sufficient time for ward round, mean ± SD) | 865 | 78.09 ± 22.33 | 81.00 ± 21.25 | 75.66 ± 22.94 | <0.001 | –5.44 (–7.96, –2.91) | <0.001 | –5.76 (–8.31, –3.22) | <0.001 |

| Feeling of being rushed during ward round, mean ± SD) | 866 | 25.27 ± 27.92 | 22.34 ± 27.15 | 27.72 ± 28.34 | 0.005 | 5.42 (2.29, 8.55) | 0.001 | 5.47 (2.34, 8.60) | 0.001 |

| Being able to carry out ward round as planned, mean ± SD) | 866 | 77.61 ± 24.45 | 80.94 ± 23.57 | 74.82 ± 24.84 | <0.001 | –6.02 (–8.79, –3.26) | <0.001 | –6.22 (–9.03, –3.40) | <0.001 |

| Being able to end ward round on time, mean ± SD) | 866 | 70.66 ± 28.44 | 72.39 ± 28.17 | 69.22 ± 28.60 | 0.10 | –3.62 (–6.99, –0.26) | 0.035 | –3.88 (–7.31, –0.46) | 0.026 |

| Staff perception of sensitive topics during ward round (VAS 0–100) | |||||||||

| Being able to discuss sensitive topics during ward round, mean ± SD) | 855 | 70.68 ± 29.21) | 84.26 ± 20.85) | 59.34 ± 30.36) | <0.001 | –25.29 (–28.48, –22.10) | <0.001 | –25.67 (–28.87, –22.47) | <0.001 |

| Being able to openly discuss all important matters during ward round, mean ± SD) | 855 | 77.96 ± 26.02 | 87.55 ± 19.01 | 69.95 ± 28.29 | <0.001 | –17.77 (–20.72, –14.81) | <0.001 | –18.01 (–20.99, –15.02) | <0.001 |

| Staff discomfort during ward round (VAS 0–100) | |||||||||

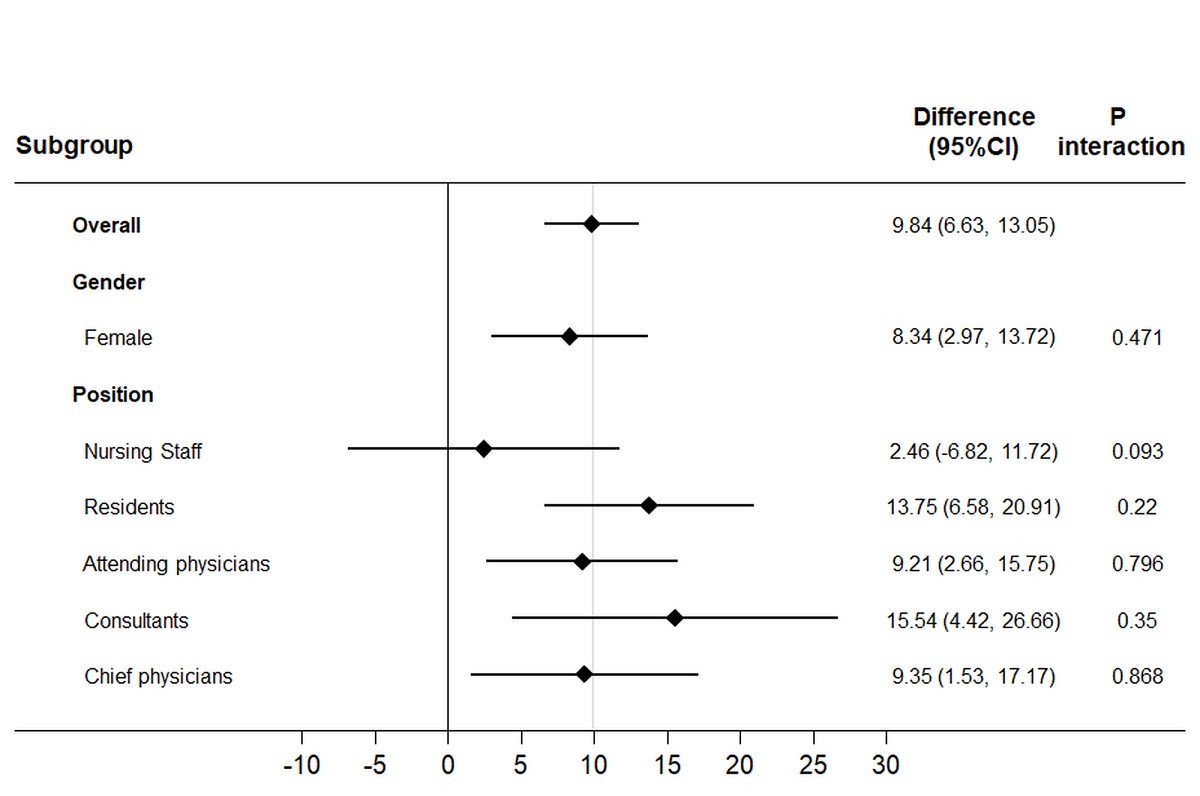

| Feeling insecure during ward round, mean ± SD) | 846 | 24.34 ± 26.81 | 18.92 ± 25.05 | 28.84 ± 27.41 | <0.001 | 9.76 (6.58, 12.94) | <0.001 | 9.84 (6.63, 13.05) | <0.001 |

| Feeling uncomfortable during ward round, mean ± SD) | 846 | 18.38 ± 24.60 | 13.68 ± 21.06 | 22.28 ± 26.60 | <0.001 | 8.55 (5.69, 11.41) | <0.001 | 8.45 (5.59, 11.30) | <0.001 |

| Being affected during conversation with patients, mean ± SD) | 846 | 27.42 ± 30.00 | 27.09 ± 30.76 | 27.70 ± 29.37 | 0.77 | 1.18 (–1.91, 4.26) | 0.455 | 1.30 (–1.81, 4.41) | 0.412 |

| Incidence of unpleasant situations with patients during ward round, mean ± SD) | 846 | 19.98 ± 25.45 | 15.21 ± 22.57 | 23.94 ± 27.01 | <0.001 | 9.01 (5.93, 12.10) | <0.001 | 9.59 (6.51, 12.68) | <0.001 |

All differences calculated with linear regression models for continuous data; CI: confidence interval; VAS: visual analogue scale; SD: standard deviation

Subgroup analyses by profession revealed mean ± SD satisfaction of nurses to be higher with bedside ward rounds (69.20 ± 20.32 versus 65.32 ± 20.92; adjusted difference 4.35, 95% CI –1.79 to 10.51; p <0.001) and satisfaction of attending physicians to be higher with outside the room ward rounds (66.59 ± 21.82 versus 82.63 ± 13.87; adjusted difference –16.51, 95% CI –20.29 to –12.72; p = 0.002) (fig. 1). Further subgroup analyses for secondary outcomes are provided as supplementary data in the appendix.

Figure 1 Satisfaction with ward rounds in different subgroups. All differences calculated with multivariate linear regression models for continuous data.

Regarding secondary endpoints, staff perception of time management during ward rounds as well as staff perception of addressing sensitive topics during ward rounds were lower for bedside presentation. Staff discomfort during ward rounds was higher in the bedside group than the outside group (table 2).

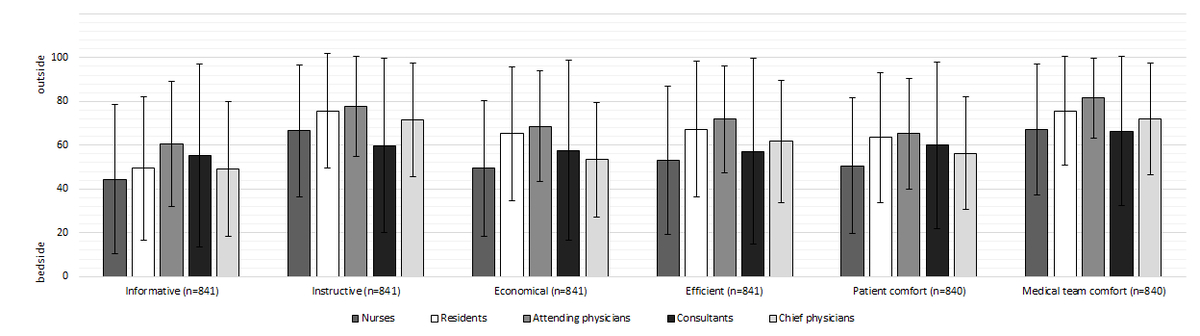

Figure 2 shows mean preferences within different professions in terms of six ward round-related aspects. We found that attending physicians preferred outside the room presentations in all aspects and nursing staff prefer bedside presentation in terms of being more informative for patients.

Figure 2 Healthcare workers mean preferences concerning different ward round related aspects. Means of preferences by profession measured on a visual analogue scale (0 [bedside] to 100 [outside]).

Table 3 presents selected comments of the qualitative remarks of the healthcare workers. Overall, there were 306 comments reported. It revealed that the main concerns of attending physicians and nurses included patients’ confusion due to medical jargon at the bedside ward round. Nurses also stated perceived lack of interprofessional communication by the patients during ward rounds. All physicians, but especially consultants, commented on their reluctance to address sensitive topics (e.g., lack of treatment adherence, substance abuse) at the bedside ward round because of potential negative reactions from patients or to avoid violation of confidentiality in multi-bedrooms.

Table 3Examples of healthcare workers’ comments on ward rounds.

| Profession | Category of comment | Comment | Condition |

| Chief physicians | Sensitive topics | We did not address patient's lack of adherence as other patients were present during the ward round. | Bedside |

| We did not bring up patient's alcohol abuse since we did not want to embarrass him in front of another patient. | Bedside | ||

| Patient confusion | We did not discuss that the patient's diagnosis was unclear as we did not want to upset him. | Bedside | |

| I did not want to correct my colleagues’ therapeutic approach in front of the patient, undermining the patient's trust. | Bedside | ||

| Consutants | Sensitive topics | Other patients in the room were listening closely when the patient's addiction issues were discussed. | Bedside |

| We avoided addressing the patient's secondary gain and potential differential diagnoses due to time constraints and language barriers. Further, other patients were present during the ward round. | Bedside | ||

| During the patient case presentation the patient passively lay in bed. We did not talk with but about the patient. | Bedside | ||

| Attending physicians | Sensitive topics | I was uncomfortable with talking about the issue that the patient was ready for discharge but did not want to leave the hospital. | Bedside |

| We could not openly discuss the reason for referring the patient to a hospice because it would have been too disturbing. A patient case presentation outside the room would have been better. | Bedside | ||

| Patient confusion | The team members of the ward round turned their back on the patient during case presentation. The patient might have picked up some medical terminology without any explanation. | Bedside | |

| Differential diagnoses were not clearly vocalised to avoid patient's confusion. | Bedside | ||

| I prefer outside the room case presentation. You should not discuss the whole medical history in front of the patient – that makes him even sicker and more confused. | Bedside | ||

| When having eye contact with the patient, I repeatedly observed confusion. | Bedside | ||

| Time management | Hasty discussion, patient's questions were not answered. | Bedside | |

| Therapeutic approach was explained too swiftly. | Bedside | ||

| Residents | Sensitive topics | Social and addiction issues were not addressed as other patients were present. | Bedside |

| In general I think the patient case presentation should take place at the bedside. However, certain sensitive topics should be prediscussed in the hallway. | Outside | ||

| Patient confusion | The decision for the treatment was made at the bedside which was disturbing for the patient. | Bedside | |

| Time management | Doctors were rushing through the whole medical history. | Bedside | |

| Patient-physician communication | The team should make sure that the patient is also involved in the case presentation during bedside rounds. | Bedside | |

| Interprofessional communication | Interdisciplinary discussions are impeded if nurses do not know the patient well or if they are not properly prepared for the ward round. | Bedside | |

| Disclosure of bad news | Tumour disease was not mentioned at the bedside as the diagnosis had not been disclosed with the patient yet. | Bedside | |

| Nurses | Sensitive topics | Lack of treatment adherence was not addressed as it appeared unpleasant for us to criticise the patient. | Bedside |

| Patient confusion | Inexperienced residents are noticeably overwhelmed and often look for backup. This might affect patients' trust negatively. | Bedside | |

| I prefer outside the room case presentation as medical terminology is confusing for patients. | Outside | ||

| I got the impression that the older generation is intimidated and many elderly do not comprehend the medical information. | Bedside | ||

| Time management | During outside the room case presentation the medical history was discussed more extensively. Although this it is important and interesting to me, it is also time consuming and meanwhile I cannot pursue my other duties and responsibilities as I might have to answer any questions. | Outside | |

| Hallway discussions take far too long and teaching of residents makes up a large part of it, leading to long waiting periods in which nurses are being left out. | Outside | ||

| Patient-physician communication | Patient was given little opportunity to express his own issues. | Bedside | |

| Interprofessional communication | I, as a nurse, felt ignored. I had to impose my requests. I did not get the impression that I was heard as my concerns were not addressed. | Bedside | |

| There was no place for my topics. | Bedside | ||

| Ward rounds often take place between doctors and nurses are being left out. It's difficult to actively participate as a nurse. | Outside |

In this ancillary project within a multicentre randomised controlled trial, we evaluated staff satisfaction with bedside and outside the room ward rounds. Results suggested overall higher satisfaction with outside the room ward rounds. This was also true for the secondary outcomes, where higher ratings were found in the outside the room group for staff perception of time management, discussion of sensitive topics and discomfort during ward rounds. Importantly, we also found a marked difference between physicians and nurses, with nursing staff members preferring bedside presentation. Several points of this survey provide important information.

First, there are several explanations for differences between nurses and physicians in satisfaction with the two types of ward round. Outside the room case discussions may be more theoretical and academic, they focus on education demands of residents and less on practical aspects of patient care. Thus, nurses may have less opportunity to join discussions outside the room, whereas at the bedside nurses may be more involved in patient-centred discussions. The finding that nurses’ contribution is under-represented in ward rounds has previously been described. Weber and Stöckli [12] described the content of patient-physician-nurse interactions during 90 internal medicine ward rounds by analysing audio recordings using a validated coding system for medical interactions [13]. They found that nurses contributed significantly less to the ward round than patients and physicians. The authors concluded that this is a potential deficiency since nurses see patients performing in daily activities. In addition, an American cross-sectional study of 90 internal medicine ward rounds found that 64.9% of interprofessional communication between nurses and physicians during ward rounds took place at the bedside, whereas only 35.1% occurred in other locations (including conference rooms, hallways and doorways) [14]. In line with this, our qualitative analysis revealed that for nurses, ward rounds pre-discussed outside the room are less useful. For example, one nurse commented that hallway discussion takes far too long and teaching of residents makes up a large part of it, leading to long waiting periods in which nurses are being left out (table 3).

Second, although results of the overall trial indicate that bedside presentation is more time efficient and results in similar knowledge by patients, in this survey physicians reported lower satisfaction with bedside presentation. There are few data about physicians’ perceptions of ward round preferences. In one trial examining the effect of 56 bedside and non-bedside presentations on Japanese residents by structured interviews, 95% of the residents preferred non-bedside patient case presentation, claiming that freedom of discussion and patients' comfort was ensured only in the absence of the patient [9]. Chauke et al. (2006) allocated 74 ward rounds in a South African academic hospital either to bedside or a conference room without patient visits, and afterwards conducted structured interviews with students, attending physicians and consultants to ascertain their preferences with regard to the types of rounds [10]. All physicians preferred bedside ward rounds, claiming that physical signs could be missed when conducting conference room ward rounds; 27% of students preferred the conference room, with arguments including freedom of discussion and not upsetting the patient with academic activities. Gonzalo et al. (2009) highlights the impact of ward rounds transitioning from bedside to the hallway and conference rooms [11]. In a cross-sectional, web-based survey 102 medical students and 51 residents were asked about their experiences and attitudes toward ward rounds. Gonzalo et al. concluded that time spent at the bedside is waning despite learners’ beliefs that bedside learning is important for professional development and suggest the necessity to re-examine current teaching methods in internal medicine services.

Third, despite methodical limitations such as the small sample size, the currently available evidence suggests two major motivations of physicians for preferring outside the room presentations: the possibility to discuss sensitive topics and the chance to avoid patient confusion [9, 10]. In line with this, in our trial several physicians commented on these aspects (table 3). Notably, attending physicians’ main concern was possible confusion of patients and thus less knowledge. In our initial report of this trial, we suggested that patients have similar knowledge of their medical care, regardless of whether rounds were conducted exclusively at the bedside or pre-discussed outside the room [6]. This was true both when measured subjectively through patients’ self-reporting and objectively when comparing patient recall of information with information retrieved from medical charts. However, team discussions at the bedside led to more confusion and uncertainty in some patients, particularly when younger patients were confronted with medical jargon [6]. Thus, physicians’ concerns about patients’ confusion shown in this analysis are partly justified, specifically in younger patients – but the similar knowledge of patients reassures that bedside rounds are feasible. Our previous analysis suggested that in the bedside presentation group, sensitive topics were less frequently discussed. This ancillary analysis confirms physicians’ concerns about not being able to address sensitive topics at the bedside. Here, two things must be considered. On the one hand the qualitative feedback suggests that the number of patients per bedroom might be crucial and negatively affect physicians in addressing sensitive topics. On the other hand, the special situation of the consultant ward round must be taken into account. Unlike daily ward rounds, it represents a challenging situation for residents who need to perform under supervision of both the attending and the chief physician. Thus, the team may choose to address sensitive topics with the patient on another, more private, occasion. Although we do not have specific information why sensitive topics were avoided, our data call for efforts to further study how to best address sensitive topics during ward rounds and how to train physicians in this regard. Further, our previous trial [6] showed that bedside presentation was more efficient and duration was about 2.5 minutes shorter compared with outside the room. However, this was perceived differently by the healthcare workers reporting lower satisfaction with time management of the bedside ward round.

There are several limitations to this secondary analysis of a randomised trial. First, we included only Swiss teaching hospitals, limiting generalisability of the findings. Second, using a pragmatic approach, ward rounds in the three participating hospitals were not standardised, in order to reflect clinical practice and ensure external validity. Consequently, this might reduce the internal validity. Third, to assess the healthcare workers’ perceptions we created a customised questionnaire that has, however, not been validated. Specifically, the main outcome – satisfaction with the ward round – was assessed on a VAS and has not been validated previously for this specific purpose. Fourth, due to the data collection via a mailed online survey, there was a limited response rate causing selection bias. Fifth, healthcare workers were not blinded which causes bias regarding the outcomes in question.

While bedside ward rounds are considered more patient centred and preferred by the nursing staff, physicians prefer outside the room presentation of patients during ward rounds due to the perceived better discussion of sensitive topics, subjectively better time management and less discomfort. Future studies need to further evaluate the underlying reasons for physicians’ and nurses’ different preferences regarding outside the room and bedside ward rounds. Moreover, our trial suggests a need to evaluate how to better involve nursing staff in outside the room ward round discussions in the future. Further, our trial brings into question how to best teach on addressing sensitive topics with the patient. Improving experience, continuous training including medical as well as interprofessional communication techniques may help to increase the satisfaction of physicians with bedside ward rounds.

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

1. Ward Rounds in Medicine: Principles for Best Practice: a Joint Publication of the Royal College of Physicians and the Royal College of Nursing, October 2012. 2012.

2. O’Mahony S , Mazur E , Charney P , Wang Y , Fine J . Use of multidisciplinary rounds to simultaneously improve quality outcomes, enhance resident education, and shorten length of stay. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Aug;22(8):1073–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0225-1

3. Pucher PH , Aggarwal R , Darzi A . Surgical ward round quality and impact on variable patient outcomes. Ann Surg. 2014 Feb;259(2):222–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000000376

4. Zwarentein M , Goldman J , Reeves S. Interprofessional collaboration : effects of practice-based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2009(3).

5. Gamp M , Becker C , Tondorf T , Hochstrasser S , Metzger K , Meinlschmidt G , et al. Effect of Bedside vs. Non-bedside Patient Case Presentation During Ward Rounds: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2019 Mar;34(3):447–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4714-1

6. Becker C , Gamp M , Schuetz P , Beck K , Vincent A , Hochstrasser S , et al.; BEDSIDE-OUTSIDE Study Group . Effect of Bedside Compared With Outside the Room Patient Case Presentation on Patients’ Knowledge About Their Medical Care : A Randomized, Controlled, Multicenter Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2021 Sep;174(9):1282–92. https://doi.org/10.7326/M21-0909

7. Wallace JE , Lemaire JB , Ghali WA . Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. Lancet. 2009 Nov;374(9702):1714–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61424-0

8. Wang-Cheng RM , Barnas GP , Sigmann P , Riendl PA , Young MJ . Bedside case presentations: why patients like them but learners don’t. J Gen Intern Med. 1989 Jul-Aug;4(4):284–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02597397

9. Seo M , Tamura K , Morioka E , Shijo H . Impact of medical round on patients’ and residents’ perceptions at a university hospital in Japan. Med Educ. 2000 May;34(5):409–11. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00516.x

10. Chauke HL , Pattinson RC . Ward rounds — bedside or conference room? S Afr Med J. 2006 May;96(5):398–400.

11. Gonzalo JD , Masters PA , Simons RJ , Chuang CH . Attending rounds and bedside case presentations: medical student and medicine resident experiences and attitudes. Teach Learn Med. 2009 Apr-Jun;21(2):105–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401330902791156

12. Weber H , Stöckli M , Nübling M , Langewitz WA . Communication during ward rounds in internal medicine. An analysis of patient-nurse-physician interactions using RIAS. Patient Educ Couns. 2007 Aug;67(3):343–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2007.04.011

13. Roter D , Larson S . The Roter interaction analysis system (RIAS): utility and flexibility for analysis of medical interactions. Patient Educ Couns. 2002 Apr;46(4):243–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00012-5

14. Stickrath C , Noble M , Prochazka A , Anderson M , Griffiths M , Manheim J , et al. Attending rounds in the current era: what is and is not happening. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Jun;173(12):1084–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6041

Table S1Staff survey.

| Personal details | ||||

| Age | Years | |||

| Gender | female | |||

| male | ||||

| not specified | ||||

| Your job position in the hospital? | Nurse | |||

| Resident | ||||

| Attending physician | ||||

| Consultant | ||||

| Chief physician | ||||

| How many years of clinical work experience do you have? | I have _ years clinical of work experience | |||

| Questions on the ward rounds | ||||

| Today I joined _ [number] of bedside case presentations | ||||

| Today I joined _ [number] of case presentations outside the room | ||||

| Today I joined _ [number] of case presentation that were not part of the study | ||||

| Please reply to each of the following questions separately for the ward rounds with bedside case presentation and ward rounds with outside the room case presentation. Enter a number from 0 to 100, depending on how much you agree or disagree with statements. | ||||

| bedside case presentations | outside the room case presentations | |||

| 0 not at all satisfied | 100 very satisfied | 0 not at all satisfied | 100 very satisfied | |

| How satisfied were you with todays ward round? | _ [0-100] | _ [0-100] | ||

| How satisfied were you with the time management of the ward round? | _ [0-100] | _ [0-100] | ||

| How satisfied were you with the medical team interaction during ward round? | _ [0-100] | _ [0-100] | ||

| How satisfied were you with the patient interaction during the ward round? | _ [0-100] | _ [0-100] | ||

| bedside case presentations | outside the room case presentations | |||

| 0 strongly disagree | 100 strongly agree | 0 strongly disagree | 100 strongly agree | |

| I had sufficient time for ward round | _ [0-100] | _ [0-100] | ||

| I felt rushed during ward round | _ [0-100] | _ [0-100] | ||

| I was able to carry out ward round as planned | _ [0-100] | _ [0-100] | ||

| I was able to end ward round on time | _ [0-100] | _ [0-100] | ||

| bedside case presentations | outside the room case presentations | |||

| 0 strongly disagree | 100 strongly agree | 0 strongly disagree | 100 strongly agree | |

| I was able to discuss sensitive topics during ward round | _ [0-100] | _ [0-100] | ||

| I was able to openly discuss all important matters during ward round | _ [0-100] | _ [0-100] | ||

| ↳ If <= 50: Which topics could not be discussed openly? For what reason? | ||||

| bedside case presentations | outside the room case presentations | |||

| 0 strongly disagree | 100 strongly agree | 0 strongly disagree | 100 strongly agree | |

| Feeling insecure during ward round, mean (SD) | _ [0-100] | _ [0-100] | ||

| Feeling uncomfortable during ward round, mean (SD) | _ [0-100] | _ [0-100] | ||

| Being affected during conversation with patients, mean (SD) | _ [0-100] | _ [0-100] | ||

| Incidence of unpleasant situations with patients during ward round, mean (SD) | _ [0-100] | _ [0-100] | ||

| Enter a number from 0 to 100, depending on how much you agree or disagree with statements. | ||||

| Ward rounds are… | 0 …bedside | 100 …outside the room | ||

| … more informative for patients when patient case presentation conducted… | _ [0-100] | |||

| … more instructive for the team when patient case presentation conducted… | _ [0-100] | |||

| … more economical when patient case presentation conducted… | _ [0-100] | |||

| … more efficient when patient case presentation conducted… | _ [0-100] | |||

| … more comfortable for patients when patient case presentation conducted ... | _ [0-100] | |||

| … more comfortable for the team when patient case presentation conducted ... | _ [0-100] | |||

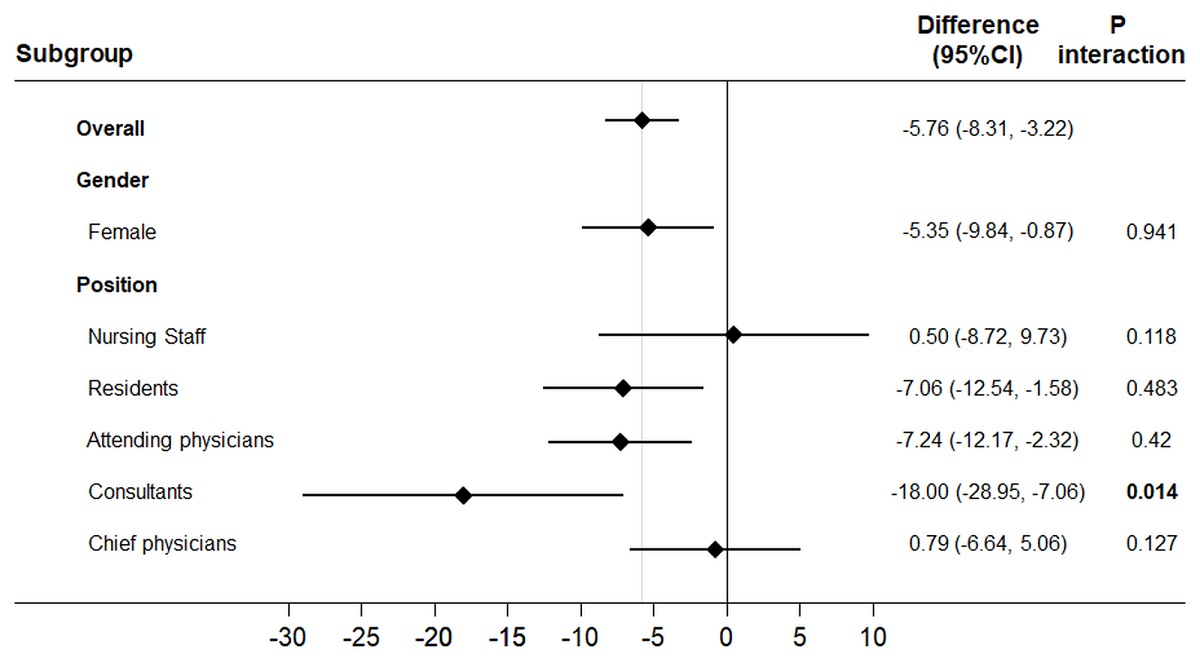

Figure S1 “Having sufficient time for ward round” in different subgroups. All differences calculated with multivariate linear regression models for continuous data.

Figure S2 “Being able to discuss sensitive topics” in different subgroups. All differences calculated with multivariate linear regression models for continuous data.

Figure S3 “Feeling insecure during ward round” in different subgroups. All differences calculated with multivariate linear regression models for continuous data.