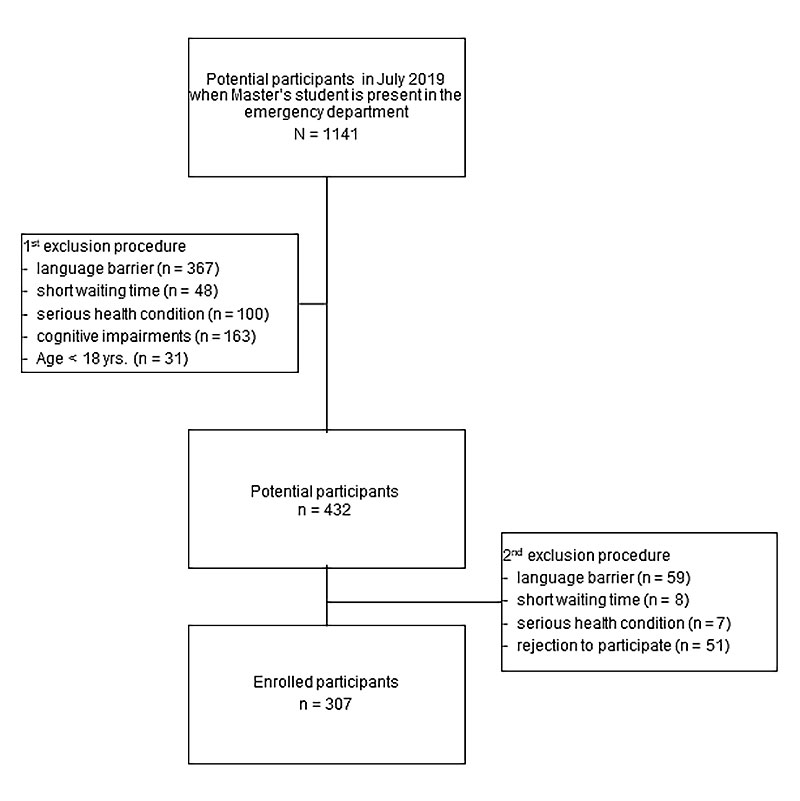

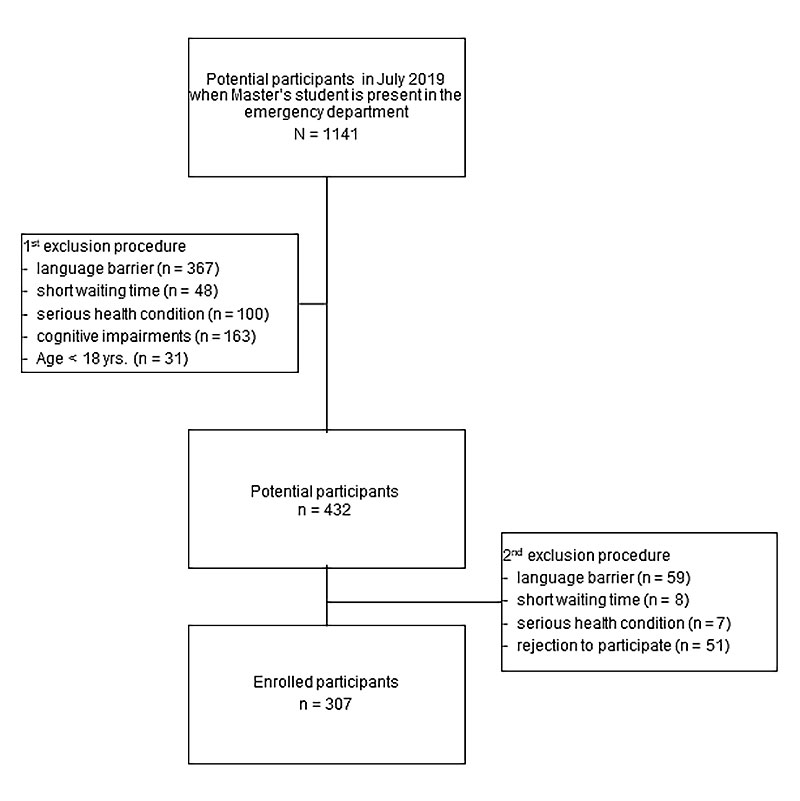

Figure 1 Flow chart.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/SMW.2022.w30100

At the end of 2020, about 1.5% of Swiss residents were registered in the National Organ Donor Registry (NODR) [1, 2]. More than 50% of the registered people were female and they had a median age of 42 years [1]. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting delay in surgery and transplants across the country, there were 146 deceased people who donated organs in 2020 [1] and, therefore, eleven persons fewer than the year before [1]. The number of living organ donors was significantly lower (83 vs 110) in 2020 than in 2019, probably as a result of the pandemic [1].

In 2020, 519 patients received an organ in Switzerland [1]. In total 2124 patients needed an organ and were on the waiting list in 2020 [1]. Seventy-two patients on the waiting list died owing to the organ shortage in 2020; most of them were waiting for a liver transplant [1]. There were many more people who needed an organ than people willing to donate one. Therefore, 43 organs (9%) had to be imported outside from Switzerland, mostly from France, and this number was still not sufficient [1]. This disproportion of patients needing an organ and available organs is the subject of ongoing discussion.

Currently, it is not mandatory for Swiss citizens to donate their organs after death, even if they did not express their opposition during their lifetime. In Switzerland, there is a so-called opt-in policy for deceased organ donation. In the opt-in system, individuals need to clearly express their preference for organ donation. Unfortunately, many Swiss people do not have an opinion on organ donation and therefore have not expressed their preferences in an organ donor card or the National Organ Donor Registry. Therefore, there is an organ shortage and a possible solution will be decided by a federal referendum on a proposal that every single Swiss resident should be a regular organ donor, unless he or she explicitly rejects organ donation (so-called opt-out policy). The Federal Council has made a counter-proposal, which states that the relatives can continue to refuse organ donation despite the new opt-out policy if the wishes of the deceased are not documented [3]. For this, the term "extended objection solution" is used. At the beginning of May 2021, the National Council approved the counter-proposal and thus the paradigm shift in organ donation [4]. After the parliament approved the Federal Council's indirect counter-proposal, the initiative committee conditionally withdrew the initiative at the beginning of October 2021. Thus, the referendum period for the indirect counter-proposal runs until end of January 2022. If there is no referendum, the indirect counter-proposal will be accepted without a popular vote [22]. With the background of the current organ shortage and political discussions, we evaluated among the emergency department (ED) population whether they have an organ donor card or are registered in the Swiss NODR and which factors were associated with being an organ donor.

In a prospective anonymised survey, we consecutively enrolled patients who visited a Swiss tertiary care ED in July 2019. The time period for patient enrollment was set a priori as follows: during one week from 8:00 to 18:00, two weeks from 14:00 to 23:00 and one week from 23:00 to 8:00.

All included patients were 18 years or older and had completed an anonymised, written, standardised and self-administrated questionnaire while waiting in the ED. Patients were excluded if they were less than 18 years old, had language barriers, refused to participate, had cognitive impairments and diseases, which might yield unreliable answers, or were unable to read and/or write.

A final ethical approval was not required after submission of the study proposal to the local ethics committee owing to anonymisation and according to the legal requirements in Switzerland.

The anonymised survey was performed in a tertiary care ED with an annual load of more than 45,000 adult patients suffering from various disorders of different severities. The ED offers a full interdisciplinary and inter-professional emergency service around the clock. The service area of the ED is the greater region of Zurich and covers highly specialised services for patients with an indication for centre transfer, such as cranio-cerebral trauma or transplant patients, in almost the entire German-speaking area of Switzerland.

The prospective and anonymised survey was conducted by a medical Master’s degree student in collaboration with and under the supervision of a senior ED epidemiologist. Because of limited staff resources, the Master’s student conducted the survey on a regular basis from Monday to Friday. However, in order to include as representative a patient population as possible, participants were interviewed in the first week from 8:00 to 18:00, during the following two weeks the enrollment was performed from 14:00 to 23:00 and in the fourth and final week from 23:00 to 8:00. The Master’s student made the initial contact with every ED patient in the waiting area of the ED and checked the in- and exclusion criteria in all ED patients. After the ED patients had agreed to participate in the survey and signed the informed consent form, they completed an anonymised paper-based, standardised and easily self-administered survey. The questionnaire could be completed independently in less than 15 minutes. If there were any questions or support was needed, the student was always available.

The survey was based on a previously developed and validated questionnaire and was adjusted to our national circumstances [5]. For this reason, some questions were added, for example, on the knowledge of the existence of the National Organ Donor Registry or on the upcoming national referendum on the new transplantation law. Furthermore, a qualified English translator and the native English-speaking Master’s student independently translated the questionnaire in a forward (from English to German) and afterwards in a backward (from German to English) translation procedure to ensure that the proper meaning of the survey questions was being conveyed.

The questionnaire included some person-related parameters such as age, gender, nationality, family status, religion, level of education, presence of any chronic diseases and previous organ donation (appendix). The survey focused on the knowledge and availability of organ donations and organ donor cards, and on knowledge of a National Organ Donor Registry and whether organ donation had been discussed with family members and/or the general practitioner. Furthermore, the reasons for deciding to donate or not to donate an organ, as well as the absence of an organ donor card, were assessed. Additionally, we asked about the willingness to donate living organs, reasons if living donation was not considered and who would benefit from living organ donation. The survey also included other questions, such as how participants would decide if a family member died and the question of organ donation came up. Finally, participants were also asked whether they would accept organ donation if they needed an organ for medical reasons.

As a first endpoint, we examined the frequency of organ donor card holders or being registered in the Swiss NODR. Secondarily, we evaluated the frequency of willingness of organ donation and factors associated with being an organ donor.

Parameters were tested for normality with the Kolmogorow-Smirnow test and performed quantile-quantile plots of dependent variables. In thecase of normally distributed parameters, means and standard deviation (SD) were reported. If the parameters not normally distributed, medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were expressed.

The primary endpoint (prevalence of organ donor card holders or registeration) as well as all categorical variables and question answers were presented as proportions.

To identify potential factors associated with having an organ donor card or being registered in the Swiss NODR, a stepwise backward multivariable regression model was used. After identifying potential factors, a uni- as well as a multivariable logistic regression analysis, adjusted for potential confounders such as age, gender (male/female) and the presence of any underlying chronic disease (no/yes), was run. The potential confounding factors were a priori defined according to the literature and clinical expertise.

For all results, we reported point estimates, 95% confidence intervals and p-values (<0.05 considered significant). We conducted the statistical analyses using the statistical program STATA SE (version 16, Stata Corp., College Station, Texas).

During the survey period, the Master’s student evaluated in total 1141 potential participants during his ED presence in July 2019. In the first selection step, 709 patients had to be excluded according to the exclusion criteria (fig. 1). Finally, 432 ED patients were evaluated in a second step for potential participation and further 74 patients (17.1%) needed to be excluded because of factors such as: language barrier, which were not obvious in the first step of exclusion, or lack of adequate time because of short waiting time in the ED, or recommendations by the care team not to conduct the interview due to serious or even life-threatening health conditions. Furthermore, 51 patients (11.8%) were excluded because they rejected to participate in the survey (fig. 1).

Figure 1 Flow chart.

Finally, 307 ED patients were enrolled, of whom 62 (20.2%) were organ donor card holders or were registered in the Swiss NODR. Of these, 53 (85.5%) would be willing to donate organs. The remaining nine participants (14.5%) with an organ donor card were not willing to donate an organ; the reasons for this were very heterogeneous.

The entire survey population included 129 females (42%) and had a median age of 41 years (IQR 28–59). More than every fourth participant (26.7%) suffered from an underlying chronic disease and seven patients (2.3%) had experienced an organ transplantation in the past. Four of these seven transplant patients had an organ donor card and were willing to donate organs. Five patients (1.6%) already had a history of stem cell or bone marrow donation (table 1).

Table 1Patients’ characteristics.

| Survey participants, n = 307 | Neither organ donor card holder nor registered, n = 245 (79.8%) | Organ donor card holder or registered in the NODR, n = 62 (20.2%) | ||

| Age* (yrs.), median (IQR ) | 41 (28–59) | 41 (29–59.5) | 37 (28–55) | |

| Gender, female (%) | 129 (42%) | 98 (40%) | 31 (50%) | |

| Chronic disease (%) | 82 (26.7%) | 66 (26.9%) | 16 (25.8%) | |

| History of organ transplantation (%) | 7 (2.3%) | 3 (1.2%) | 4 (6.5%) | |

| History of blood donation (%) | 130 (42.4%) | 98 (40%) | 32 (51.6%) | |

| History of previous stem cell or bone marrow donation (%) | 5 (1.6%) | 2 (0.8%) | 3 (4.8%) | |

| Sociodemographic parameters | ||||

| Nationality (%) | Swiss | 175 (57.0%) | 135 (55.1%) | 40 (64.5%) |

| Others | 118 (38.4%) | 97 (39.6%) | 21 (33.9%) | |

| Double nationality (incl. Swiss) | 14 (4.6%) | 13 (5.3%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| Marital status (%) | Single | 133 (43.3%) | 99 (40.4%) | 34 (54.8%) |

| Married / in partnership | 131 (42.7%) | 110 (44.9%) | 21 (33.9%) | |

| Divorced | 27 (8.8%) | 22 (9.0%) | 5 (8.1%) | |

| Widowed | 15 (4.9%) | 13 (5.3%) | 2 (3.2%) | |

| Missing answer | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0% | |

| Highest achieved education (%) | Compulsory schooling | 33 (10.7%) | 28 (11.4%) | 5 (8.1%) |

| Vocational training | 125 (40.7%) | 105 (42.9%) | 20 (32.3%) | |

| University degree | 147 (47.9%) | 110 (44.9%) | 37 (59.7%) | |

| Missing answers | 2 (0.7%) | 2 (0.8%) | 0% | |

| Religion (%) | Christian | 160 (52.1%) | 129 (52.7%) | 31 (50%) |

| Muslim | 17 (5.5%) | 17 (6.9%) | 0% | |

| Buddhist | 4 (1.3%) | 2 (0.8%) | 2 (3.2%) | |

| Hindu | 4 (1.3%) | 3 (1.2%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| None | 108 (35.2%) | 80 (32.7%) | 28 (45.2%) | |

| Others | 14 (4.6%) | 14 (5.7%) | 0% | |

IQR: interquartile range; NODR: National Organ Donor Registry

Participants having an organ donor card or being registered in the NODR were more often Swiss (64.5% vs 55.1%), singles (54.8% vs 40.4%), more often had a university degree (59.7% vs 44.9%) and reported more often not belonging to a religious community (45.2% vs 32.7%) compared with participants without an organ donor card or were not registered in the Swiss NODR (table 1). Further sociodemographic results are shown in table 1.

The majority of the organ donor card holders (79%) had a paper-based organ donor card. Whereas 14.5% were registered in the National Organ Donor Registry, 6.5% were registered either digitally as well as on the traditional system by holding a paper-based card. A minority of 67 participants (28.4%) of the total survey population were aware of the existence of the new National Organ Donor Registry. Of all, 257 participants (83.7%) knew what organ donation or an organ donor card is and had already discussed the topic with family members in 50.2% (n = 154) and with primary care physicians in 11.9% (n = 36) (table 2). Organ donor card holders discussed this issue more often with family members and primary care physicians (table 2).

Table 2Knowledge and information about the organ donation.

| Survey participants, n = 307 | Neither organ donor card holder nor registered, n = 245 (79.8%) | Organ donor card holder or registered in the NODR, n = 62 (20.2%) | |

| Know what an organ donor card is (%) | 257 (83.7%) | 197 (80.4%) | 62 (100%) |

| Spoke with family members about the topic of organ donation (%) | 154 (50.2%) | 99 (40.4%) | 55 (88.7%) |

| Spoke with a doctor about the topic of organ donation (%) | 36 (11.9%) | 21 (8.7%) | 15 (24.2%) |

NODR = National Organ Donor Registry

Among the sub-population of those who were willing to donate organs, the two leading reasons for the willingness to donate organs were: to help after death (94.3%) and to discharge relatives from the task to take the decision for them (43.4%). Further reasons are presented in table 3.

Table 3Reasons for organ donation.

| Why have you decided to donate your organs? | Willing to donate organs, n = 53 (17.3%) |

| A way to help after my death | 50 (94.3%) |

| I want to spare my family/friends the stresses of having to decide on my behalf | 23 (43.4%) |

| Motivated through fellow humans | 11 (20.8%) |

| I want to be able to decide what happens to my body after my death | 10 (18.9%) |

| Public discourse | 7 (13.2%) |

| One day I'll be in need of organs myself | 4 (7.5%) |

| Religious reasons | 2 (3.8%) |

| Others1 | 8 (15.1%) |

More than one answer was possible; 1 Others were reasons for positive organ donation such as organ transplantation in the family or own experience.

From the remaining 245 participants who did not have an organ donor card or were not registered, the majority (34.3%) had a lack of knowledge in this topic, 26.5% have not yet thought about it and 20.8% had not had time to deal with this issue. Further reasons are shown in table 4.

Table 4Reasons for neither having an organ donor card nor being registered.

| What are the reasons you don't have an organ donor card? | Neither organ donor card holder nor registered, n = 245 (79.8%) |

| Not informed well enough or even no knowledge | 84 (34.3%) |

| Haven't thought about this topic yet | 65 (26.5%) |

| Haven't had time to take care of it yet | 51 (20.8%) |

| Organ(s) are also damaged | 34 (13.9%) |

| Don't want to decide yet | 30 (12.2%) |

| Bodily integrity | 15 (6.1%) |

| My family already knows my wishes | 14 (5.7%) |

| Afraid of misuse of organs | 12 (4.9%) |

| I'm too young | 10 (4.1%) |

| Family/friends should decide on my behalf | 9 (3.7%) |

| Worried I will not receive all medical therapeutic options if I decide to donate my organs | 7 (2.9%) |

| I don't remember why | 5 (2.0%) |

| Religious reasons | 4 (1.6%) |

| My wish doesn't count anyway | 3 (1.2%) |

| No advantage for me/family | 2 (0.8%) |

| Others* | 22 (9.0%) |

More than one answer was possible

* Others were reasons for not having an organ donor card e.g., infection, taking regular medicaments and not being from Switzerland with plan to go back to the country of origin.

Factors associated with a higher likelihood of having an organ donor card or being registered were a positive history of regular blood donation (odds ratio [OR] 2.1, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1–3.9; p = 0.018), a university degree (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.013.2; p = 0.049), and having received an organ transplantation as a patient in the past (OR 5.6, 95% CI 1.225.5; p = 0.027) (table 5).

Table 5Factors associated with a higher likelihood of having an organ card or being registered in the National Organ Donor Registry

| Neither organ donor card holder nor registered, n = 245 (79.8%) | Organ donor card holder or registered, n = 62 (20.2%) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI, p-value) | Adjusted OR (95% CI, p-value) | |

| History of previous organ transplantation (%) | 3 (1.2%) | 4 (6.5%) | 5.6 (1.2–25.5, 0.027) | 6.1 (1.3–29.1, p=0.023) |

| History of previous blood donation (%) | 98 (40%) | 32 (51.6%) | 1.6 (0.9–2.8, p=0.10) | 2.1 (1.1–3.9, p=0.018) |

| Having a university degree (%) | 110 (44.9%) | 37 (59.7%) | 1.8 (1.01–3.2, p=0.044) | 1.8 (1.003–3.2, p=0.049) |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval. Results are adjusted for possible confounders such as age, sex and the presence of underlying chronic diseases (yes/no).

In addition, the study population was asked about living organ donation (table 6). More than one third of respondents (34.9%) had never thought about this possibility and 27 participants (8.8%) had never heard about living organ donation (table 6). One hundred and twenty-nine participants (42.0%) were willing to be living organ donors. Organ donor card holders were more likely to be willing to be living organ donors (61.3% vs 37.1%) than no organ donor card holders (table 6). The majority of the respondents were willing to be living organ donors for close family members such as a child or grandchild (38.4%), spouse (34.5%) or parents (31.3%). A lower willingness to donate organs was found for friends (25.7%) and for unknown persons (17.9%) (table 6).

Table 6Living organ donation.

| Survey participants, n = 307 | Neither organ donor card holder nor registered, n = 245 (79.8%) | Organ donor card holder or registered in the NODR, n = 62 (20.2%) | ||

| Willing to be a living organ donor (%) | Never thought about this | 107 (34.9%) | 93 (38.0%) | 14 (22.6%) |

| Never heard of this | 27 (8.8%) | 23 (9.4%) | 4 (6.5%) | |

| Yes, I would be willing for certain people | 129 (42.0%) | 91 (37.1%) | 38 (61.3%) | |

| I am not willing to donate organs while alive | 44 (14.3%) | 38 (15.5%) | 6 (9.7%) | |

| Which organs for living organ donation* (%) | Bone marrow / stem cells | 119 (38.8%) | 81 (33.1%) | 38 (61.3%) |

| Part of liver | 96 (31.3%) | 65 (26.5%) | 31 (50.0%) | |

| Kidney | 95 (30.9%) | 68 (27.8%) | 27 (43.5%) | |

| Whom willing to donate organ* (%) | Child/grandchild | 118 (38.4%) | 85 (34.7%) | 33 (53.2%) |

| Partner | 106 (34.5%) | 73 (29.8%) | 33 (53.2%) | |

| Spouse | 96 (31.3%) | 62 (25.3%) | 34 (54.8%) | |

| Grandparents | 64 (20.8%) | 41 (16.7%) | 23 (37.1%) | |

| Other family members | 104 (33.9%) | 70 (28.6%) | 34 (54.8%) | |

| Friends | 79 (25.7%) | 50 (20.4%) | 29 (46.8%) | |

| Unknown person | 55 (17.9%) | 37 (15.1%) | 18 (29.0%) | |

* More than one answer was possible.

NODR: National Organ Donor Registry

Table 7 presents survey results on how the respondents would decide about organ donation in the event of a relative’s death. If the will of the deceased were not known, almost 60% of the respondents would choose (31.9%) or most likely choose (27.0%) to donate an organ. A clear group difference emerged, in that organ donor card holders or those who are registered would be less likely to decline the organ donation.

Table 7The decision about organ donation in the event of a relative’s death.

| Survey participants, n = 307 | Neither organ donor card holder nor registered, n = 245 (79.8%) | Organ donor card holder or registered in the NODR, n = 62 (20.2%) | ||

| If you were asked to decide on a relative's behalf whether their organs can be donated and their will is not known, what would you decide? | No | 47 (15.3%) | 44 (18.0%) | 3 (4.8%) |

| More likely no | 55 (17.9%) | 47 (19.2%) | 8 (12.9%) | |

| More likely yes | 83 (27.0%) | 64 (26.1%) | 19 (30.6%) | |

| Yes | 98 (31.9%) | 70 (28.5%) | 28 (45.2%) | |

| No answer | 24 (7.8%) | 20 (8.2%) | 4 (6.5%) | |

| If you were asked to decide on a relative's behalf whether their organs can be donated and you knew that their will was to donate their organs, what would you decide? | No | 18 (5.9%) | 16 (6.5%) | 2 (3.2%) |

| More likely no | 9 (2.9%) | 8 (3.3%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| More likely yes | 33 (10.7%) | 32 (13.1%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| Yes | 233 (75.9%) | 176 (71.8%) | 57 (91.9%) | |

| No answer | 14 (4.6%) | 13 (5.3%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| If you were asked to decide on a relative's behalf whether their organs can be donated and their will was to not donate organs, what would you decide? | No | 182 (59.3%) | 150 (61.2%) | 32 (51.6%) |

| More likely no | 45 (14.7%) | 36 (14.7%) | 9 (14.5%) | |

| More likely yes | 28 (9.1%) | 23 (9.4%) | 5 (8.1%) | |

| Yes | 39 (12.7%) | 25 (10.2%) | 14 (22.6%) | |

| No answer | 13 (4.2%) | 11 (4.5%) | 2 (3.2%) | |

| Do you believe there is a certain risk associated with the will to donate organs in the sense that the medical staff might not pursue all therapeutic medical options? | No | 141 (45.9%) | 109 (44.5%) | 32 (51.6%) |

| More likely no | 86 (28.0%) | 66 (26.9%) | 20 (32.3%) | |

| More likely yes | 40 (13.0%) | 34 (13.9%) | 6 (9.7%) | |

| Yes | 14 (4.6%) | 13 (5.3%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| No answer | 26 (8.5%) | 23 (9.4%) | 3 (4.8%) | |

| If your life could only be saved by means of organ transplantation, would you accept an organ? | No | 25 (8.1%) | 21 (8.6%) | 4 (6.5%) |

| More likely no | 20 (6.5%) | 19 (7.7%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| More likely yes | 59 (19.2%) | 51 (20.8%) | 8 (12.9%) | |

| Yes | 192 (62.5%) | 144 (58.8%) | 48 (77.4%) | |

| No answer | 11 (3.6%) | 10 (4.1%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

NODR: National Organ Donor Registry

The decision to answer the question was easier if the will of the deceased was known and the person was willing to donate an organ. In this case, 75.9% (n = 233) of respondents decided in favour of organ donation and 10.7% (n = 33) were more likely to donate. Organ donor card holders or those who are registered were significantly more likely to be in favour of organ donation when asked this question (table 7).

If the deceased person did not wish an organ donation after death, 20% of the respondents decided to donate the organs of the relative after all. Almost one in three of the organ donor card holders would even decide against the wish of the deceased (table 7).

Nearly three quarters of participants had confidence that medical staffwould pursue all therapeutic options and not stop any treatment too soon simply because the patient is an organ donor (table 7).

More than 80% of participants (n = 251) would accept organ donation for themselves should they need an organ. This also applied to respondents who did not have an organ donor card at the time of the survey (table 7).

Finally, the participants were also asked about their opinion on the upcoming federal referendum regarding the amendment of the transplantation act by changing the current system from an opt-in to an opt-out policy. If federal referendum had been held at the time of the survey, 198 respondents (64.5%) would have opted for a change in the law. Especially, holders of an organ donor card or those who are registered in the Swiss NODR supported the amendment significantly more often (83.9% vs 59.6%) than those without an organ donor card or registration. At the time of the survey, 51 participants (16.6%) had not yet made an opinion.

In summary, only one in five ED patients had a fully completed organ donor card or were registered in the Swiss NODR. Of these, the great majority were willing to donate organs. Most of the ED patients who did not have an organ donor card or were not registered lacked knowledge and information about the topic, had not yet thought about it or had not had time to deal with this issue. Factors such as blood donation and organ transplantation in the past or having a university degree were associated with being an organ donor card holder.

In many European countries, opt-out policies with presumed consent for deceased organ procurement are common strategies to address the organ shortage for years. Such countries are for example Austria or Spain. The positive impact of an opt-out policy on organ availability is well illustrated by the example of Wales. In early December 2015, Wales introduced a soft opt-out policy for organ donation, where consent for organ donation was presumed unless the person had opted out. The impact of the Welsh opt-out policy was highlighted by Madden et al., who reported that the likelihood of consenting to organ donation was 2.1 times higher in Wales than in England [6]. The convincing results of the opt-out policy in Wales led England and Scotland to also introduce the opt-out system in May 2020 and March 2021, respectively, in the hopes of addressing organ shortages. The UK Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation Activity Report 2020/21 desribed an increase in opt-out registrations across the UK, with two million people on the organ donor registry by March 2021 [7]. Other European countries, such as Switzerland or Germany, have the opt-in policy that the removal of organs and tissues after death is only permissible if the deceased people consented to it during their lifetime or if the relatives consented on their behalf. Which organ donation model (opt-out or opt-in) is the more effective is still controversial. There is some literature clearly supporting the opt-out policy because this system leads to a larger pool of organs for transplantation [6, 8–11]. On the other hand, there is also some literature that disagrees with the opt-out regulation [12–16]. Owing to this controversy, Molina-Pérez et al. performed a systematic review in 2019 [17]. It showed that the consent to organ donation in countries with an opt-in policy is higher than in opt-out countries [17]. Hansen et al. postulated a public campaign that better informs about and sensitises the population to the organ shortage and the possibility of organ donation as the reason for the higher approval of the opt-in strategy [18]. They also showed that enhanced education and better knowledge about the transplantation system is associated with an increased willingness to donate organs [18]. These results are supported by our survey findings. The current survey also showed an increased willingness to donate organs when participants had a university degree. Additionally, the majority of the survey respondents who were not organ donor card holders or were not registered in the Swiss NODR lacked knowledge and information about the topic. In addition, more than one in three did not know about the possibility of living donation, which again indicates that there is a large gap in knowledge and information.

Despite the fact that the opt-out policy seems to provide a larger pool of organs, there are some ethical and legal issues. Organ donation rates in opt-out countries seem to be higher only when the public is less informed about the law and its requirements [12]. This is seen as coercion and disrespect for individual autonomy over the body, mind and spirit, which is a clear ethical problem with opt-out policies [19, 20]. In contrast, proponents of the opt-out strategy argue that with this policy, each individual's freedom of choice and individual responsibility are still preserved, and one can refuse organ donation by registering the refusal in national registries [21]. However, the systematic review by Molina-Pérez et al. showed that people from countries with opt-out policies were insufficiently informed about the possibility of actively excluding themselves as potential organ donors [17]. This is clearly reflected by the current survey result that people who had already been previously transplanted are very well informed about the procedures and are more likely to be potential organ donors, pointing out that insufficient information and knowledge about transplantation is the reason for higher organ donation rates in opt-out countries.

The participants of the current survey were also asked about their opinion on the upcoming federal referendum on the amendment of the transplantation act changing the current system from opt-in to an opt-out policy. The majority of respondents were in favour of a change to an opt-out system, notably over 80% of organ donor card holders or those who are registered in the Swiss NODR. This high level of support for the opt-out policy could be due to the increased public awareness campaign that the opt-out system can solve the problem of organ shortage.

Regardless of which system (opt-out or opt-in) is better, both systems show that regular education, investment in knowledge and training, and the resulting transfer of information to the population increases willingness to donate organs. Hence, we recommend that each individual voter compare the personal pros and cons of each system (current opt-in vs new opt-out) in the upcoming referendum and choose the right option for him or herself.

Therefore, we recommend, whether or not the current system remains or is replaced by the opt-out strategy, that the general population continues to be informed, that school classes are educated about the issue and that people talk about organ donation. It must no longer be a taboo subject, because only in this way can people develop their own opinion, act on their own responsibility and increase the number of organ donations.

In the last part of the current survey on how the respondents would decide about organ donation in the event of a relative’s death, we showed that there can be differences between the respondent's decision and the last will of the deceased person. Especially in cases where the deceased was in favour of organ donation, about 10% of respondents would decide against the wish of the deceased person and refuse organ removal. Additionally, almost 30% of the organ donor card holders would allow organ removal even if the deceased did not wish to donate organs. These survey results may indicate huge problems in communication and acceptance of the decisions among family members, friends and the loved ones. Therefore, each individual should have an advance directive filled out during their lifetime and plan the further procedures by means of advance care planning. The possible donation of organs after death is just as much a part of advance care planning as the wishes about further therapy measures in critical or palliative situations. Furthermore, every single person has the chance, independent of the current transplantation act, to officially register their organ donation willingness (yes or no) in the National Organ Donation Registry. Additionally, close relatives must be informed about the advance care planning, so that in the event of death the close relatives are informed and can act as well as decide based on the will of the deceased person.

The survey has some limitations. We were not able to obtain consecutive enrollment (24/7) of all ED patients during the four weeks of observation because of limited staff resources (Master’s student thesis). Furthermore, critically ill patients and many patients with language barriers had to be excluded. Nevertheless, the survey results are similar to the existing literature and are therefore generalisable.

A strength of this survey is the prospective design and enrollment of participants during all 24/7 ED work-shifts. Furthermore, the response rate was rather high and the rejection rate was only about 11%. An additional strength is that we were missing information on marital or educational status from only three participants. This success was based on the active one-site ED presence of the Master thesis student and the study team.

Only every fifth ED patient had a fully completed organ donor card or were registered in the Swiss NODR. Of these, the great majority were willing to donate organs. Most of the ED patients who did not have an organ donor card or were not registered in the Swiss NODR lacked knowledge and information about the topic, had not yet thought about it or had not had time to deal with this issue.. Factors such as a positive history of blood donation, organ transplantation or having a university degree were associated with having an organ donor card.

Regardless of which organ donation system (opt-out or opt-in) is better, with regular education, investment in knowledge and training, and the resulting transfer of information to the population an increase in the willingness to donate organs can be achieved.

There was no no funding.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

1. Jahresbericht Swisstransplant . 2020 [cited 2021 Jun 4]. Available from: https://wwwswisstransplantorg/fileadmin/user_upload/Bilder/Home/Swisstransplant/Jahresbericht/Jahresbericht_2020_DEpdf

2. Swisstransplant. Nationales Organspenderegister. [cited 2021 Jun 4]. Available from: https://registerswisstransplantorg/pages/public/registrationWizardxhtml?lang=de

3. Bundesamt für Gesundheit BAG [cited 2021 Jun 16]. Available from: https://wwwbagadminch/bag/de/home/medizin-und-forschung/transplantationsmedizin/rechtsetzungsprojekte-in-der-transplantationsmedizin/indirekter-gegenvorschlag-organspende-initiativehtml

4. Die Bundesversammlung — Das Schweizer Parlament Nationalrat stimmt Paradigmenwechsel bei der Organspende zu, May 05, 2021 [cited 2021 Jun 16]. Available from: https://www.parlament.ch/de/services/news/Seiten/2021/20210505154341785194158159038_bsd139.aspx(last

5. Nordfalk F , Olejaz M , Jensen AM , Skovgaard LL , Hoeyer K . From motivation to acceptability: a survey of public attitudes towards organ donation in Denmark. Transplant Res. 2016 May;5(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13737-016-0035-2

6. Madden S , Collett D , Walton P , Empson K , Forsythe J , Ingham A , et al. The effect on consent rates for deceased organ donation in Wales after the introduction of an opt-out system. Anaesthesia. 2020 Sep;75(9):1146–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15055

7. Acitivty Report NH . Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation.2020/21 [cited 2021 Sept 14]. Available from: https://nhsbtdbeblobcorewindowsnet/umbraco-assets-corp/23461/activity-report-2020-2021pdf

8. Gimbel RW , Strosberg MA , Lehrman SE , Gefenas E , Taft F . Presumed consent and other predictors of cadaveric organ donation in Europe. Prog Transplant. 2003 Mar;13(1):17–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/152692480301300104

9. Johnson EJ , Goldstein D . Medicine. Do defaults save lives? Science. 2003 Nov;302(5649):1338–9. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1091721

10. Mossialos E , Costa-Font J , Rudisill C . Does organ donation legislation affect individuals’ willingness to donate their own or their relative’s organs? Evidence from European Union survey data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008 Feb;8(1):48. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-8-48

11. Shepherd L , O’Carroll RE , Ferguson E . An international comparison of deceased and living organ donation/transplant rates in opt-in and opt-out systems: a panel study. BMC Med. 2014 Sep;12(1):131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0131-4

12. Rithalia A , McDaid C , Suekarran S , Myers L , Sowden A . Impact of presumed consent for organ donation on donation rates: a systematic review. BMJ. 2009 Jan;338 jan14 2:a3162. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a3162

13. Fabre J , Murphy P , Matesanz R . Presumed consent: a distraction in the quest for increasing rates of organ donation. BMJ. 2010 Oct;341 oct18 2:c4973. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c4973

14. Fabre J . Presumed consent for organ donation: a clinically unnecessary and corrupting influence in medicine and politics. Clin Med (Lond). 2014 Dec;14(6):567–71. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.14-6-567

15. Willis BH , Quigley M . Opt-out organ donation: on evidence and public policy. J R Soc Med. 2014 Feb;107(2):56–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076813507707

16. McCartney MN . HOLDS BARRED Margaret McCartney: when organ donation isn’t a donation. BMJ. 2017;•••:356.

17. Molina-Pérez A , Rodríguez-Arias D , Delgado-Rodríguez J , Morgan M , Frunza M , Randhawa G , et al. Public knowledge and attitudes towards consent policies for organ donation in Europe. A systematic review. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2019 Jan;33(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trre.2018.09.001

18. Hansen SL , Eisner MI , Pfaller L , Schicktanz S . “Are You In or Are You Out?!” Moral Appeals to the Public in Organ Donation Poster Campaigns: A Multimodal and Ethical Analysis. Health Commun. 2018 Aug;33(8):1020–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2017.1331187

19. MacKay D . Opt-out and consent. J Med Ethics. 2015 Oct;41(10):832–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2015-102775

20. MacKay D , Robinson A . The Ethics of Organ Donor Registration Policies: Nudges and Respect for Autonomy. Am J Bioeth. 2016 Nov;16(11):3–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2016.1222007

21. Hamm D , Tizzard J . Presumed consent for organ donation. BMJ. 2008 Feb;336(7638):230. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39475.498090.80

22. Federal Office of Public Health FOPH . Bundesrat und Parlament wollen bei der Organspende die Widerspruchslösung einführen. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/medizin-und-forschung/transplantationsmedizin/rechtsetzungsprojekte-in-der-transplantationsmedizin/indirekter-gegenvorschlag-organspende-initiative.html

The questionnaire is available in the PDF version of the article.