Development of a value-based healthcare delivery model for sarcoma patients

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/SMW.2021.w30047

Bruno

Fuchsabcd, Gabriela

Studerab, Beata

Bodee, Hanna

Wellauerc, Annika

Freic, Carlo

Theusb, Guido

Schüpferb, Jan

Plockf, Hubi

Windeggerc, Stefan

Breitensteinc, for the SwissSarcomaNetwork

aUniversity of Lucerne, Switzerland

bKantonsspital Luzern, Lucerne, Switzerland

cKantonsspital Winterthur, Switzerland

dUniversitätsspital Zürich, Zurich, Switzerland

ePatho Enge, Zurich, Awitzerland

fKantonsspital Aarau, Switzerland

Summary

The urgent need to restructure healthcare delivery to address rising costs has been recognised. Value-based health care aims to deliver high and rising value for the patient by addressing unmet needs and controlling costs. Sarcoma is a rare disease and its care is therefore usually not organised as an institutional discipline. It comprises a set of various diagnostic entities and is highly transdisciplinary. A bottom-up approach to establishing sarcoma integrated practice units (IPUs) faces many challenges, but ultimately allows the scaling up of quality and outcomes of patient care, specific knowledge, experience and education. The key for value-based health care – besides defining the shared value of quality – is an integrated information technology platform that allows transparency by sharing values, brings all stakeholders together in real-time, and offers the opportunity to assess quality of care and outcomes, thereby ultimately saving costs. Sarcoma as a rare disease may serve as a model of how to establish IPUs through a supraregional network by increased connectivity, to advance patient care, to improve science and education, and to control costs in the future, thereby restructuring healthcare delivery. This article describes how the value-based health care delivery principles are being adopted and fine-tuned to the care of sarcoma patients, and already partially integrated in seven major referral hospitals in Switzerland.

Starting point

Cost explosion in health care is a global issue. In 2018, many western countries spent roughly 10% – the USA even 17.7% – of their gross domestic product (GDP) on health care [1]. There is global consensus that the value per spent dollar needs to be optimised [2, 3]. Value-based health care (VBHC) aims to deliver high and rising value for the patient, addressing unmet needs and controlling costs. Sarcoma care deals with a rare disease and is therefore usually not organised as an institutional discipline; it comprises a set of various diagnostic entities and is highly transdisciplinary.

Value-based healthcare delivery model

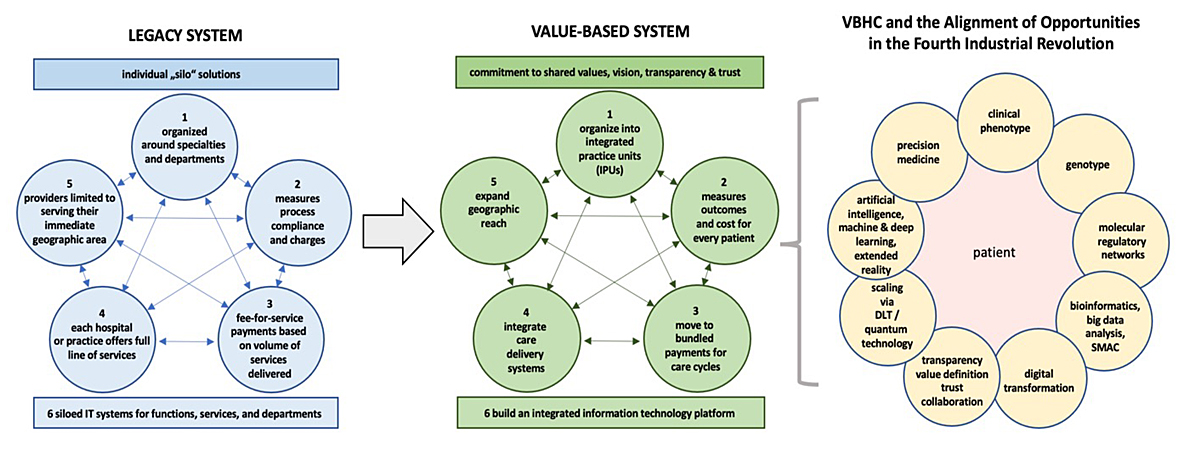

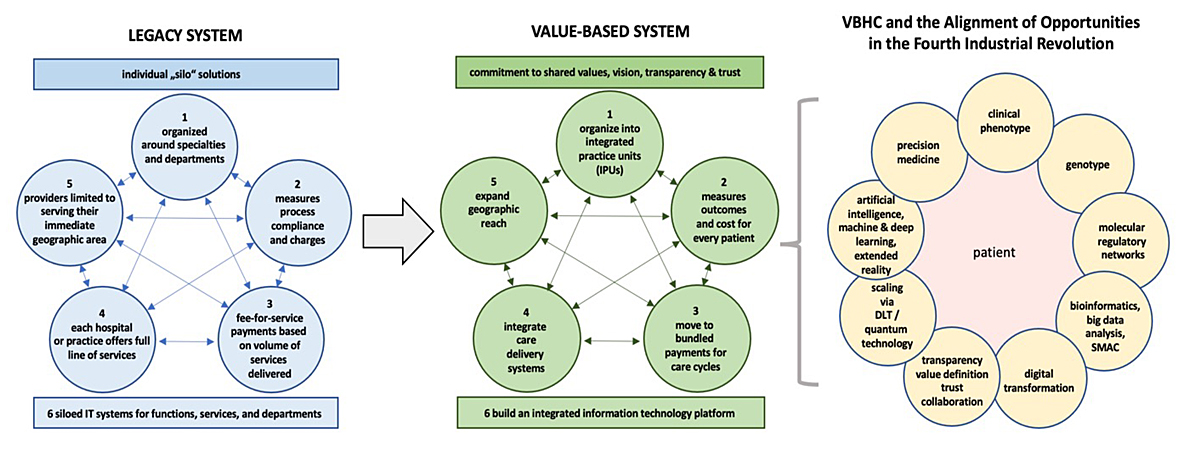

Porter et al. described a healthcare legacy structure, which emerged over decades [4–8]. Such a siloed system is organised within disciplines and institutions, provides fee-for-service and measures process compliance, without extramural exchange (fig. 1).

Figure 1 The legacy system evolved over decades and is based on individual silo solutions of single institutions without exchange. The value-based system builds on shared commitment to defining and assessing quality and outcome using a shared information technology platform. Such an integrated system will prepare our health system to meet the opportunities of the fourth industrial revolution.

Such systems allow various stakeholders to succeed, but not necessarily the patient. Many support the concept of regionalisation of care based only on patient volume as a key strategy for quality and outcome improvement, specifically for surgical disciplines. However, high volume by itself does not guarantee good outcomes, especially when bad processes are being reinforced by high-volume repetition, without assessing quality indicators [9, 10]. Simply advancing structural changes without process improvements is like pushing on a string [11]. The fundamental purpose and goal of health care is to deliver high and rising value for patients, with value being defined as the outcomes and quality of care over the total costs of delivering these outcomes throughout the entire health cycle [3, 12]. The key for VBHC – besides defining the shared value of quality – is an integrated information technology platform that allows transparency by sharing values, brings all stakeholders together in real-time, establishes transparency and offers the opportunity to assess quality of care and outcomes, and thereby ultimately saving costs.

Integrated practice units

For the implementation of a VBHCD-based system, the following key steps are required:

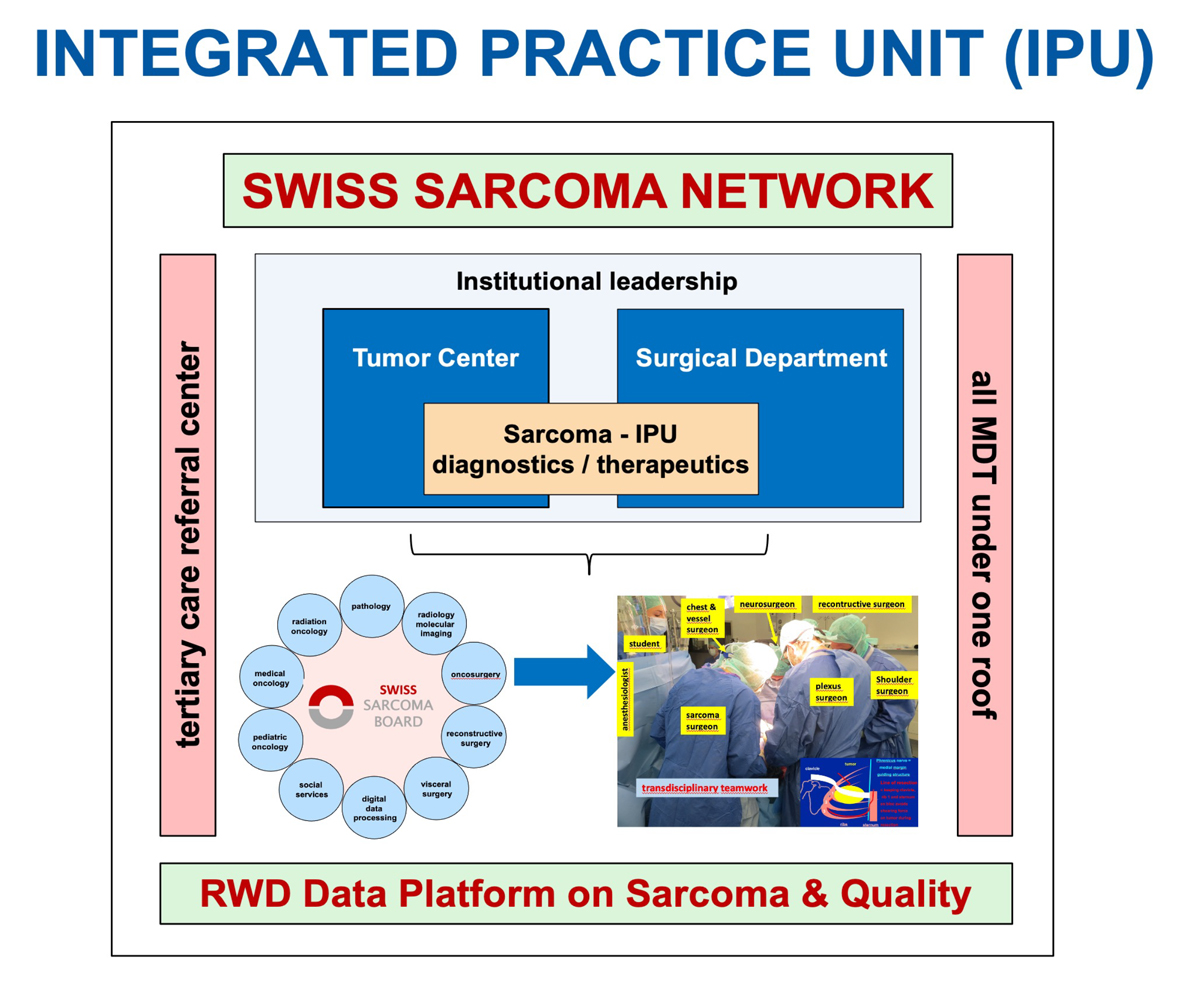

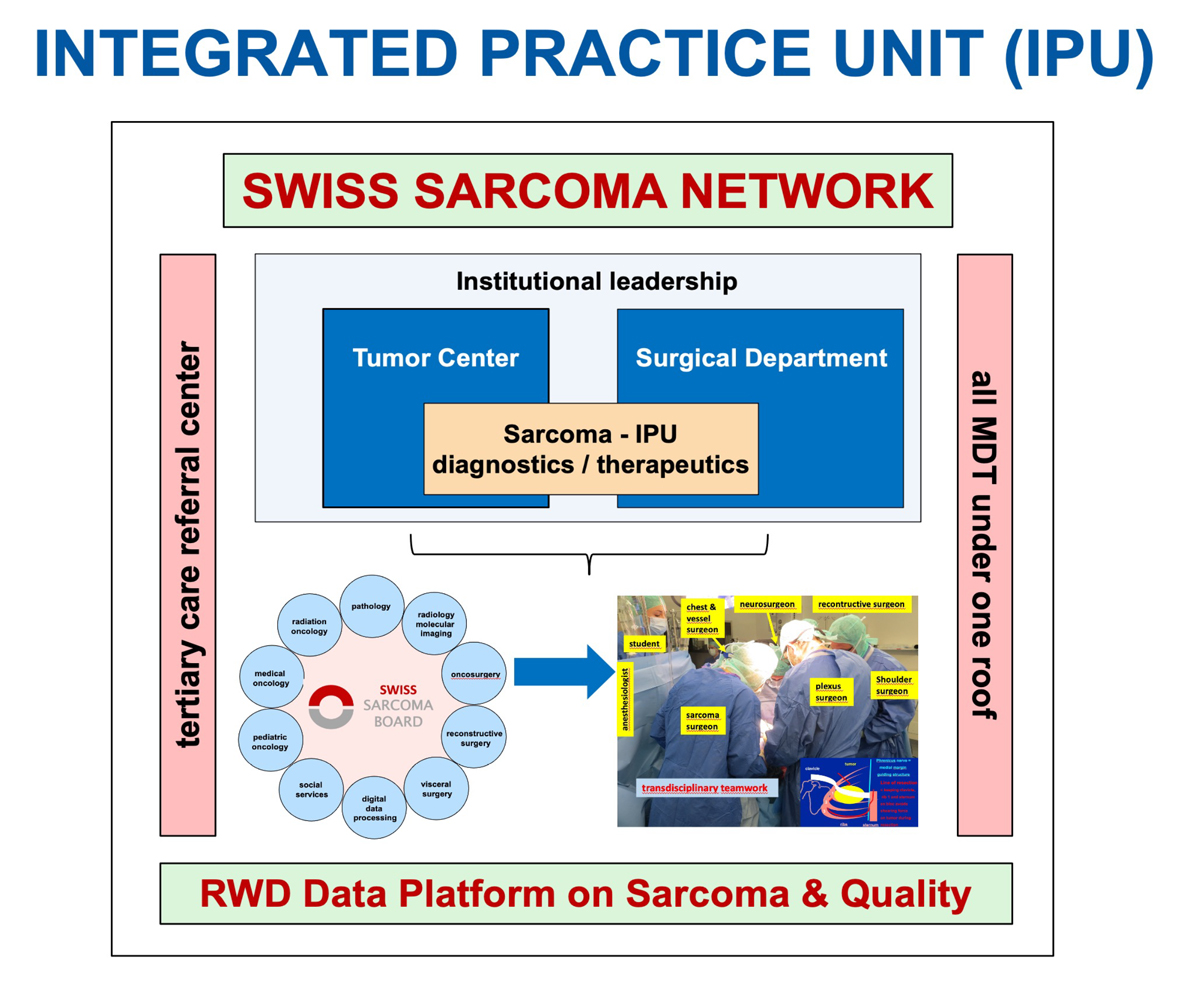

(1.) Structuring of an integrated practice unit (IPU) organised around a medical condition by delivering care in a transdisciplinary team whose members devote a significant amount of time to the condition (fig. 2) [13]. An IPU works in dedicated multidisciplinary facilities including all disciplines under one roof, and takes responsibility for the full cycle of care. Within the IPU, outcomes, costs, care processes and patient experience are routinely measured and shared on a common platform. The team accepts joint accountability for outcomes and costs, and meets regularly, formally and informally, to discuss and improve care plans, results and processes.

Figure 2 Sarcoma not being a discipline, the sarcoma IPU is built from the surgical transdisciplinary teams and the tumour centre with its associated disciplines. Sharing a common information technology real-world data platform, the sarcoma IPUs can be scaled up across the country.

(2.) Outcome measurement with value: Outcomes are measured by condition, not for specialties or procedures, and measurement covers the full cycle of care. They are multidimensional and include what matters most to patients, not just to physicians. Initial conditions and risk factors are standardised for each condition and are measured in the line of care.

(3.) Alignment of reimbursement with value:

(4.) Systems integration aims to shift the current confederation of stand-alone units/facilities to clinically integrated care-delivery systems.

(5.) Geographic expansion: The strategic principles for the geographic and value model organise care by condition in IPU hubs, where services are allocated across the care cycle to sites based on capabilities, care complexity, patient risk, cost and patient convenience, while incorporating telemedicine, home services and affiliated provider sites [14]. The IPU develops a formal system to direct patients to the most appropriate site.

(6.) Integrated technology platform: Attributes of a value-based information technology platform include all types of data for the full care cycle using standardised definitions and terminology, allowing storage and extraction from a common warehouse, with the capability to aggregate, extract, run analytics and display data in real-time by condition and over time. The warehouse enables the capture and aggregation of outcomes, costing parameters, and billing capacities for bundled payments.

Opportunities

Traditional sarcoma centres function in institutional silos at best, without a common language for exchange between centres or in the referral network, and therefore not specifically referring to a definition of patient value in terms of outcome and quality over the full cycle of care. They also do not provide the opportunity for patient-centred cost alignment. Conversely, the sarcoma IPU importantly highlights the need to focus on the patient as the centre around whom the entire care cycle needs to be organised in order to explicitly define and assess quality and outcome, entailing adoption of the proposed system change.

What does the future of patient care look like? Medicine’s most fundamental element remains the relationship between the patient and the physician, which must therefore be at the heart of health care and which has been a constant across cultures and centuries [15]. Team work with a coordinating physician leader is the bedrock principle for success, and is strengthened through the introduction of a sarcoma IPU.

Challenges

Current structures aim to geographically centralise patient volumes independent of quality indicators, and there is continued debate regarding an organisational shift towards networks [16]. Whereas it is undoubtedly correct to centralise care of complex patients, territorial centralisation has the downside of separating the centre from the periphery. The DKG (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft), for example, has established process-based criteria for the definition of sarcoma centres which ultimately allow at best only two thirds of all sarcoma patients to be treated at such a centre (www.krebsgesellschaft.de). The largest existing dataset from the National Cancer database shows that only 3310 patients were treated in high-volume centers (defined as centres treating >20 soft tissue sarcoma patients only per year!), whereas 22,000 patients were treated in low-volume centres [10]. Various demographic and socio-cultural reasons obviously prevent patients from travelling, and as long as there are no networks – in which surgical complexity allows centralisation – covering the entire country, these numbers will remain unchanged. The inclusion of all sarcoma patients must be the goal, and therefore collaboration in a network is indispensable [17].

Digital opportunities enable unprecedented connectivity and transparency, which above all will advance the knowledge and experience of all network experts without geographic exclusion. Digital connectivity also allows the spread of a common language with aligned definitions on every aspect of disease and therapy. Such a system allows the definition of quality and complexity care indicators based on which centralisation to units with the most experience (and not for territorial reasons) for the patient’s needs will become possible, which is the base of personalised medicine.

Today, 21st century medical technology is often delivered with 19th century organisational structures, management practices and pricing models. The consumer cannot fix the dysfunctional structure of the current system. Healthcare workers are caught within the system, and various incentives prevent current structures from changing and improving. A reset is required, and value-based delivery provides the horizon. The driver to alignment of all unmet needs is the digital real-world data platform, providing a common language for all quality indicators and value definitions to enable transparency, operational efficiency and effectiveness, with instant real-time access for all involved stakeholders.

Outlook

Healthcare transformation is well underway. Value-based thinking is restructuring the organisation of care, outcome measurement, personalised payment models and health system strategy. Standardised outcome measure sets and new costing practices ultimately accelerate value improvement. Government and legal bodies will have a critical role in this process. They can require universal measurement and reporting of provider health outcomes, help shift the reimbursement systems to bundled payments for cycles of care instead of payments for discrete treatments or services, remove obstacles to the restructuring of healthcare delivery around the integrated care of medical conditions, open up competition among providers and across the country, and set policies to encourage greater responsibility of individuals for their health and their health care. Physicians have to define quality indicators and start measuring outcome indices for all medical conditions, thereby providing the base for a value-based healthcare system.

Where are we in Switzerland?

The members of the SwissSarcomaNetwork (SSN; www.swiss-sarcoma.net) comprise all institutions that are willing to consecutively assess and share their transdisciplinary sarcoma data within a prospective real-world data platform (prospective RWD Sarcoma Registry of Quality). Within this national network, transdisciplinary sarcoma care is being organised in IPUs across the country. On the international level, SSN is an official member of SELNET, a Sarcoma European and Latin American network which is supported by a Horizon 2020 framework programme of the European Union, and is thereby embedded in the largest existing sarcoma network of multidisciplinary clinical and translational sarcoma experts aiming to improve diagnosis and clinical care in sarcomas.

Together with an international advisory board of world-renowned sarcoma experts from the world sarcoma network, sarcoma quality indicators of work-up, of the weekly Sarcomaboard/MDT tumour conference, of the complexity of treatment, of the outcome as well as of PROMS/PREMS are being defined, totalling more than 70 parameters. These quality metrics and results of their descriptive analysis are automatically generated from the registry and visualised in real-time on an interactive website for all SSN members, thereby enabling the quality management system which has been required by law in Switzerland since April 2021. With such a set-up, predictive outcome analysis becomes ultimately possible. As a next step in the future, a cost tag will be attributed to each structured data parameter in the registry to assess the costs over the entire healthcare cycle, thereby letting VBHC become a reality. To further extend the quality efforts internationally, the Sarcoma Academy (www.sarcoma.academy) was founded to facilitate exchange between international sarcoma experts through sarcoma webinars and forums.

Bruno Fuchs, MD PhD

Chair SwissSarcomaNetwork, University of Lucerne

Brauerstrasse 15

CH-8401 Winterthur

office[at]sarcoma.surgery

References

1.

Hartman M

,

Martin AB

,

Espinosa N

,

Catlin A

; The National Health Expenditure Accounts Team

. National Health Care Spending In 2016: Spending And Enrollment Growth Slow After Initial Coverage Expansions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018 Jan;37(1):150–60. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1299

2.

Scholer M

. Wenn wir so weitermachen, fahren wir das System an die Wand. Schweiz Arzteztg. 2017;98(15-16):495-7.

3.

Noseworthy J

. Why Mayo Clinic, despite its five-star rating, believes it’s time to rethink how quality is graded. Mod Healthc. 2016 Oct;46(43):29.

4.

Porter ME

,

Teisberg EO

. Redefining competition in health care. Harv Bus Rev. 2004 Jun;82(6):64–76.

5.

Porter ME

,

Pabo EA

,

Lee TH

. Redesigning primary care: a strategic vision to improve value by organizing around patients’ needs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013 Mar;32(3):516–25. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0961

6.

Porter ME

. A strategy for health care reform—toward a value-based system. N Engl J Med. 2009 Jul;361(2):109–12. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp0904131

7.

Porter ME

,

Lee TH

. From Volume to Value in Health Care: The Work Begins. JAMA. 2016 Sep;316(10):1047–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.11698

8.

Porter ME

. Value-based health care delivery. Ann Surg. 2008 Oct;248(4):503–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818a43af

9.

Lin CC

,

Smeltzer MP

,

Jemal A

,

Osarogiagbon RU

. Risk-Adjusted Margin Positivity Rate as a Surgical Quality Metric for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017 Oct;104(4):1161–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.04.033

10.

Lazarides AL

,

Kerr DL

,

Nussbaum DP

,

Kreulen RT

,

Somarelli JA

,

Blazer DG 3rd

, et al.

Soft Tissue Sarcoma of the Extremities: What Is the Value of Treating at High-volume Centers? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019 Apr;477(4):718–27. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.blo.0000533623.60399.1b

11.

Osarogiagbon RU

. Volume-Based Care Regionalization: pitfalls and Challenges. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Oct;38(30):3465–7. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.02269

12.

Swensen SJ

,

Dilling JA

,

Harper CM Jr

,

Noseworthy JH

. The Mayo Clinic Value Creation System. Am J Med Qual. 2012 Jan-Feb;27(1):58–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860611410966

13.

Porter ME

,

Lee TH

. Integrated Practice Units: A Playbook for Health Care Leaders. NEJM Catal. 2021;2(1):CAT.20.0237. https://doi.org/10.1056/CAT.20.0237

14.

Porter ME

,

Lee TH

,

Murray AC

. The Value-Based Geography Model of Care. NEJM Catal. 2020;1(2):CAT.19.1130. https://doi.org/10.1056/CAT.19.1130

15.

Noseworthy J

. The Future of Care - Preserving the Patient-Physician Relationship. N Engl J Med. 2019 Dec;381(23):2265–9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr1912662

16.

Andritsch E

,

Beishon M

,

Bielack S

,

Bonvalot S

,

Casali P

,

Crul M

, et al.

ECCO Essential Requirements for Quality Cancer Care: Soft Tissue Sarcoma in Adults and Bone Sarcoma. A critical review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017 Feb;110:94–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.12.002

17.

Blay JY

,

Soibinet P

,

Penel N

,

Bompas E

,

Duffaud F

,

Stoeckle E

, et al.

Improved survival using specialized multidisciplinary board in sarcoma patients. Ann Oncol. 2017 Nov;28(11):2852–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx484