COVID-19 vaccination acceptance in the canton of Geneva: a cross-sectional population-based study

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/SMW.2021.w30080

Ania

Wisniakab, Hélène

Bayssona, Nick

Pullena, Mayssam

Nehmec, Francesco

Pennacchioa, María-Eugenia

Zaballaa, Idris

Guessouscd*, Silvia

Stringhiniade*, the Specchio-COVID19 study group

aUnit of Population Epidemiology, Division of Primary Care Medicine, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland

bInstitute of Global Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Geneva, Switzerland

cDivision and Department of Primary Care Medicine, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland

dUniversity Center for General Medicine and Public Health, University of Lausanne, Switzerland

eDepartment of Health and Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Geneva, Switzerland

*Contributed equally to this work.

Summary

OBJECTIVE: This study aimed to assess acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination as well as its sociodemographic and clinical determinants, 3 months after the launch of the vaccination programme in Geneva, Switzerland.

METHODS In March 2021, an online questionnaire was proposed to adults included in a longitudinal cohort study of previous SARS-CoV-2 serosurveys carried out in the canton of Geneva, which included former participants of a population-based health survey as well as individuals randomly sampled from population registries, and their household members. Questions were asked about COVID-19 vaccination acceptance, reasons for acceptance or refusal and attitudes to vaccination in general. Data on demographic (age, sex, education, income, professional status, living conditions) and health-related characteristics (having a chronic disease, COVID-19 diagnosis, smoking status) were assessed at inclusion in the cohort (December 2020). The overall vaccination acceptance was standardised according to the age, sex, and education distribution in the Geneva population.

RESULTS: Overall, 4067 participants (completion rate of 77.4%) responded to the survey between 17 March and 1 April 2021. The mean age of respondents was 53.3 years and 56.0% were women. At the time of the survey, 17.2% of respondents had already been vaccinated with at least one dose or had made an appointment to get vaccinated, and an additional 58.5% intended or rather intended to get vaccinated. The overall acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination standardised to the age, sex and education distribution of the population of Geneva was 71.8%, with a higher acceptance among men than women, older adults compared with younger adults, high-income individuals compared with those with a low income, and participants living in urban and semi-urban areas compared with rural areas. Acceptance was lower among individuals having completed apprenticeships and secondary education than those with tertiary education. The most common reasons reported by participants intending to get vaccinated were the desire to "get back to normal", to protect themselves, their community and/or society,and their relatives or friends against the risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2, as well as the desire to travel. Less than half (45.6%) of participants having children were willing or rather willing to have their children vaccinated against COVID-19 if it were recommended by public health authorities.

CONCLUSION: Although our study found a 71.8% weighted acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination, there were noticeable sociodemographic disparities in vaccination acceptance. These data will be useful for public health measures targeting hesitant populations when developing health communication strategies.

Introduction

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, unprecedented global efforts have enabled the development of several safe and effective vaccines only 1 year after the first COVID-19 case was diagnosed in Wuhan, China. Worldwide, the first COVID-19 vaccines tested in phase III trials were commercialised at the beginning of December 2020, with the messenger RNA-based Comirnaty® vaccine of Pfizer/BioNTech [1] being the first authorised in the United Kingdom on 3 December 2020. In addition to manufacturing and logistical challenges, vaccination campaigns worldwide have been challenged by diffuse distrust of the population regarding the safety and efficacy of these novel vaccines [2–6].

Vaccine hesitancy fuelled by misinformation campaigns has often been a threat to sufficient vaccine coverage over past decades, sometimes leading to resurgence of vaccine-preventable diseases [7–9]. This has led the World Health Organization to recognise vaccine hesitancy as a major threat to global health in 2019 [10]. International efforts to urgently deliver a safe and effective vaccine against COVID-19 have been faced with a growing anti-vaccination movement amplified by social media since the early phases of the pandemic, with the potential to negatively impact vaccination uptake in populations exposed to these campaigns [2, 5, 11–13].

By 23 December 2020, the date of the launch of COVID-19 vaccination, Switzerland had reported 4896 confirmed cases/100,000 inhabitants and 6406 deaths since the beginning of the pandemic [14]. In addition to the direct health consequences of COVID-19, social distancing measures and closure of nonessential services have led to negative social, psychological and economic consequences. In the canton of Geneva, a population-based serological survey has shown that by the end of December 2020, 21.1% of the canton’s population had been infected with SARS-CoV-2 since the start of the pandemic [15], suggesting a relatively slow rise in population immunity if social distancing measures preventing the collapse of healthcare systems were to be pursued. At the time of our survey, in March 2021, two mRNA-based vaccines were available in Switzerland – the Comirnaty® (BNT162b2) vaccine of Pfizer/BioNTech [1] and the COVID-19 vaccine (mRNA-1273) of Moderna [16]. At that time, in the canton of Geneva, vaccination priority was given to individuals aged 65 years and older, individuals deemed "particularly vulnerable to COVID-19", as well as health workers in close contact with at-risk patients [17]. Mass vaccination campaigns were carried out separately in each canton (i.e., state) of Switzerland. In the canton of Geneva, at the time of the study, COVID-19 vaccination was offered to pre-identified high-risk population groups through mass vaccination centres located throughout the canton, or at the workplace for health workers, and a mass vaccination communication campaign had not started yet.

Reaching sufficient coverage, however, is in large part dependent on the population’s willingness to get vaccinated. A national survey conducted in Switzerland shortly before the arrival of the first vaccines on the market revealed that only 56% of respondents were likely to accept vaccination against COVID-19, with a lack of trust in the security of the vaccines being the main reason for refusal [18]. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that vaccine hesitancy was associated to sociodemographic factors such as younger age, female gender, lower income and lower education [2, 19, 20]. In order to address vaccine hesitancy in a comprehensive way and deliver targeted interventions, reasons for accepting or refusing vaccination, as well as associated socioeconomic factors, should be explored in a regional context, as results found in other countries cannot be extended to all populations, as a result of cultural, political and organisational factors influencing vaccination acceptance. In addition, taking into account people’s positive or negative emotions about vaccination is essential to developing effective communication campaigns [21].

The aim of our study was (1) to assess the population’s willingness to get vaccinated against COVID-19 3 months after the launch of the vaccination programme in Geneva, Switzerland, (2) to explore individuals’ attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination and their reasons for accepting or declining the vaccination, and (3) to describe associations between socioeconomic or health-related factors and vaccine hesitancy.

Methods

Study design, setting and sample

This population-based cross-sectional study was embedded in a longitudinal digital cohort study called Specchio-COVID19, which was launched in December 2020 to follow up over time participants in serosurveys conducted in the canton of Geneva [22]. Serosurvey participants were randomly selected from the general population at two time points: (1) between April and June 2020, participants were enrolled from a previous general health survey (Bus Santé) representative of the population of the canton of Geneva aged between 20 and 75 years [23], and (2) between November and December 2020, participants were randomly selected from registries of the Canton of Geneva stratified by age and sex [15].

After a baseline serological test, all serosurvey participants were invited to join the Specchio-COVID19 study, which consists of a long-term follow up by collecting data through regular on-line questionnaires and serological follow-up. From the original 8904 adult serosurvey participants invited to be followed up longitudinally, 5282 enrolled in the digital cohort (participation rate 59.3%, not taking into account participants unreachable owing to false email addresses), of whom 30 withdrew their participation prior to the vaccination survey. Upon registration, an initial questionnaire assessed sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics and general health-related data. Self-reported SARS-CoV-2 infections and risk perception of COVID-19 are updated through monthly questionnaires. The questionnaire designed for this study was sent out to participants on 17 March 2021, with a reminder sent 2 weeks later. Data on the age, sex and education distribution in the population of the canton of Geneva were obtained from the Cantonal Office of Statistics of Geneva [24].

Data collected in the COVID-19 vaccination questionnaire

The “vaccination” questionnaire was based on a literature review and was validated by public health experts and physicians. Part of the content was developed in the framework of the Corona Immunitas research programme, a national programme aiming to coordinate regional SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence studies across Switzerland [25]. Outcomes measured in the vaccination questionnaire corresponded to the Specchio-COVID19 objective to “evaluate risk perception, the adoption of preventive behaviours and acceptance of COVID-19-related public health policies over time”.

The main outcome of this study was COVID-19 vaccination intention, defined as the combined answer to the following two questions: “Were you already vaccinated against COVID-19? (yes, no, scheduled appointment)” and “Do you intend to get vaccinated once you will be eligible for vaccination against COVID-19? (yes, rather yes, rather no, no, does not know).” Answers “yes” and “scheduled appointment” to the first question and answers “yes” and “rather yes” to the second question were later combined as willingness/intention to get vaccinated. Answers “no” and “rather no” to the second question were defined as no willingness/intention to get vaccinated.

Secondary outcomes included reasons to get vaccinated, reasons for refusing vaccination, vaccination-related beliefs (e.g., perceived efficacy, perceived safety, preference for natural immunity), perceived utility of COVID-19 vaccination and willingness to vaccinate one’s children against COVID-19.

The questionnaire also included three questions from a French study on vaccination hesitancy [26] adapted from the World Health Organization’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) definition of vaccine hesitancy [27], general attitudes regarding vaccination, and trust in public health authorities, pharmaceutical companies, scientists and researchers. These questions are described in more detail in the appendix. Two questions were additionally asked on the perception of immunity certificates for COVID-19, for which analyses were conducted and described in a separate paper submitted to the same journal.

We constructed the variable "vaccine hesitancy" (hesitant/not hesitant) based on the SAGE definition, categorising as "hesitant" participants who had at some point refused vaccination and/or delayed vaccination and/or accepted vaccination despite doubts on its effectiveness. Those who answered "no" to all three questions were considered "not vaccine hesitant".

Previous SARS-CoV-2 infection was defined as either being SARS-CoV-2 seropositive or having self-reported a positive polymerase chain-reaction (PCR) or antigenic test for SARS-CoV-2 in one of the monthly surveys.

Education was categorised as follows: (1) compulsory education or no formal education, (2) apprenticeships, (3) secondary school and specialised schools, and (4) tertiary education including universities, higher professional education and doctorates.

Income was categorised as "low" (below the first quartile of the general population of the canton of Geneva), "medium" (between the first and third quartiles) or "high" (above the third quartile), taking into account self-reported household income from the baseline questionnaire, as well as household composition (living alone with or without children, in a relationship with or without children, or in a shared apartment with other adults), and according to household income statistics for the same household composition categories within the canton of Geneva [28].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses included percentages with comparisons using chi-square tests for categorical variables. P-values were considered significant at p <0.05. The overall vaccination acceptance was standardised according to the age, sex, and education distribution in the Geneva population. Distribution of education within the population was only taken into account for individuals aged 25 years and older, as the information was not available for those aged 18–24 years.

Logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess the associations of demographic and health-related factors with COVID-19 vaccination intention. Participants having answered “I don’t know” to the question on vaccination intention were removed from the logistical regression model, as our aim was to evaluate associations of the participants’ characteristics with vaccination intention as opposed to vaccination refusal. Sex- and age-adjusted logistic models were run for all the following variables individually: sex, age, education, household income, residential area, employment status, living conditions, having a chronic disease, smoking status, previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, perception of COVID-19 severity and contagiousness, and vaccine hesitancy. For each variable, we also ran multivariable logistic regressions adjusting for age, sex, education and income. The intersex category as well as the “not available” (NA) categories for all variables were excluded from the logistical regression analysis because of low counts. Odds ratios and confidence intervals were calculated through exponentiation of estimated coefficients. Statistical significance was taken at the level of p <0.05 a priori. All analyses were conducted using R 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Ethical considerations

All participants of the Specchio-COVID19 digital platform provided informed and written consent upon enrolment in the study. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Cantonal Research Ethics Commission of Geneva, Switzerland (project number 2020-00881). The protocol of the overarching study (Specchio-COVID19) can be found at https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.07.14.21260489v1.

Results

Descriptive characteristics of the sample

Of the 5282 participants enrolled in the Specchio-COVID19 platform, 4067 (completion rate of 77.4%) responded to the vaccination survey between 17 March and 1 April 2021 (the study flow chart is presented as supplementary figure S1 in the appendix). The mean age of participants was 53.3 years (± standard deviation 14.4 years) and 56.0% were women. Most had completed a tertiary education (n = 2631; 64.7%) and over 60% were currently professionally active (as an independent or an employee). Overall characteristics are presented in the appendix (table S1). In comparison with the general population in the canton of Geneva, our participants were older (44.3% individuals aged 50 years and older in Geneva vs 60.5% in our sample) and had a higher education level (64.9% tertiary education in our sample vs 39.9% in the Geneva population) (table S2 in the appendix).

Compared with non-respondents, participants responding to the vaccination survey were older (mean age 53.3 ± 14.4 years vs 43.8 ± 14.4 years), more highly educated (64.7% vs 63.2% had tertiary education, 3.9% vs 6.8% had no formal education, p <0.001), had a higher income (12.9% vs 16.3% had low income, 64.8% vs 55.9% middle or high income, p <0.001), were more frequently retired (25.9% vs 9.8%) and less frequently students (4% vs 12%, p <0.001), and were less frequently current smokers (14.9% vs 19.2%, p <0.001). Sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of survey respondents compared with non-respondents are presented in table S1.

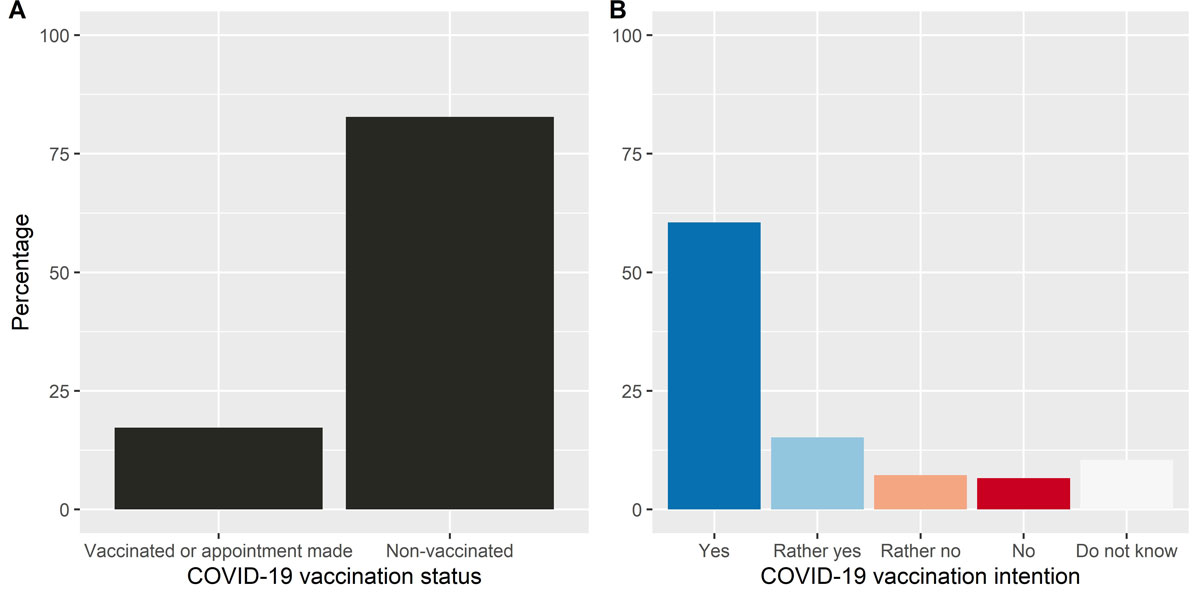

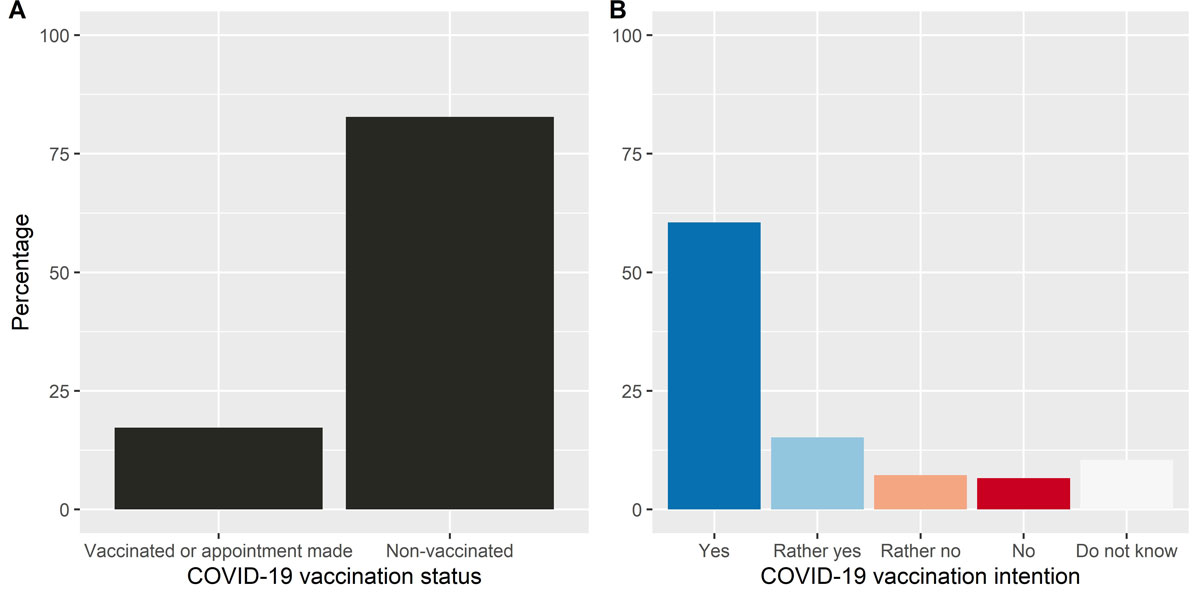

Vaccination status and intention

At the time of the survey, 17.2% of respondents had already been vaccinated with at least one dose or had made an appointment to get vaccinated. Moreover, 58.5% of participants intended or rather intended to get vaccinated, whereas only 13.8% did not or rather did not intend to get vaccinated, and 10.4% did not know if they intended to get vaccinated (fig. 1). The overall acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination (including those intending or rather intending to get vaccinated and those already vaccinated) standardised to the age, sex and education distribution of the population of Geneva was 71.8%.

Figure 1 A. Proportion of participants vaccinated / with appointment for vaccination versus participants not vaccinated against COVID-19. B. Intention to get vaccinated against COVID-19; "yes" combines those willing to get vaccinated and those already vaccinated or who have an appointment.

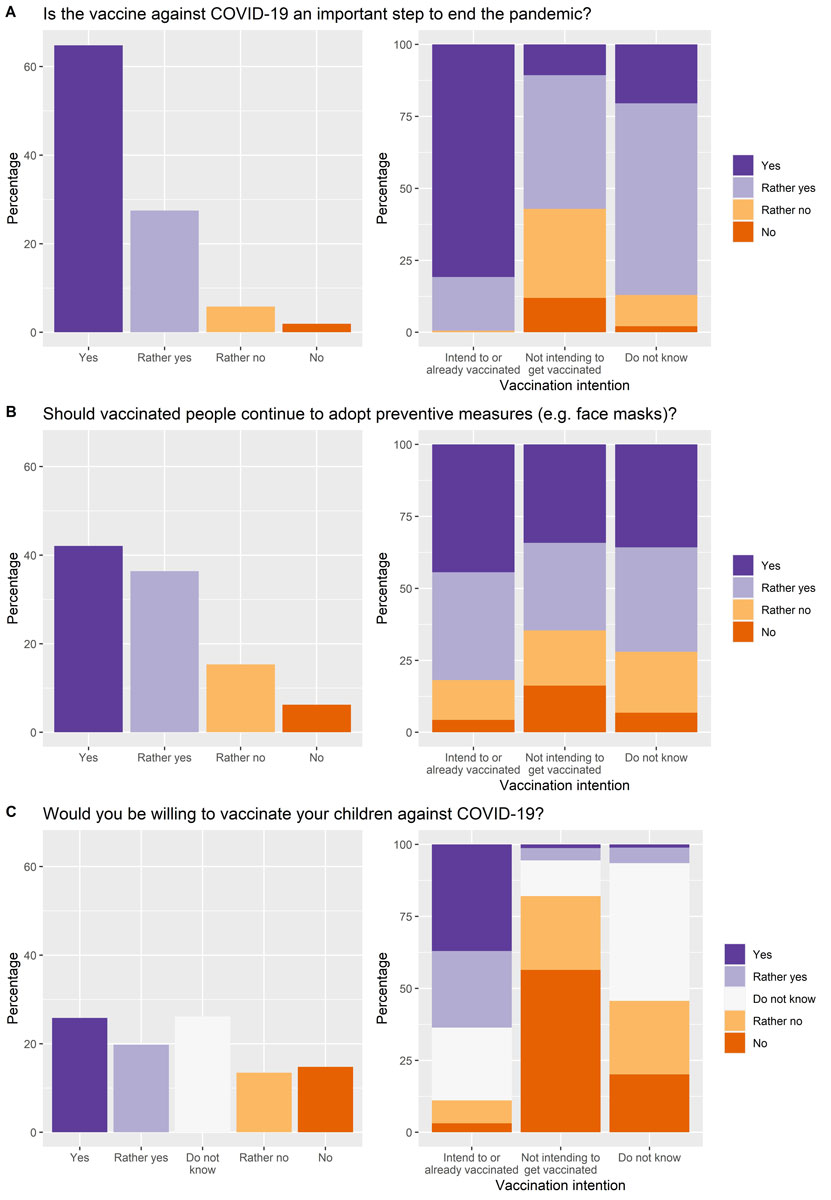

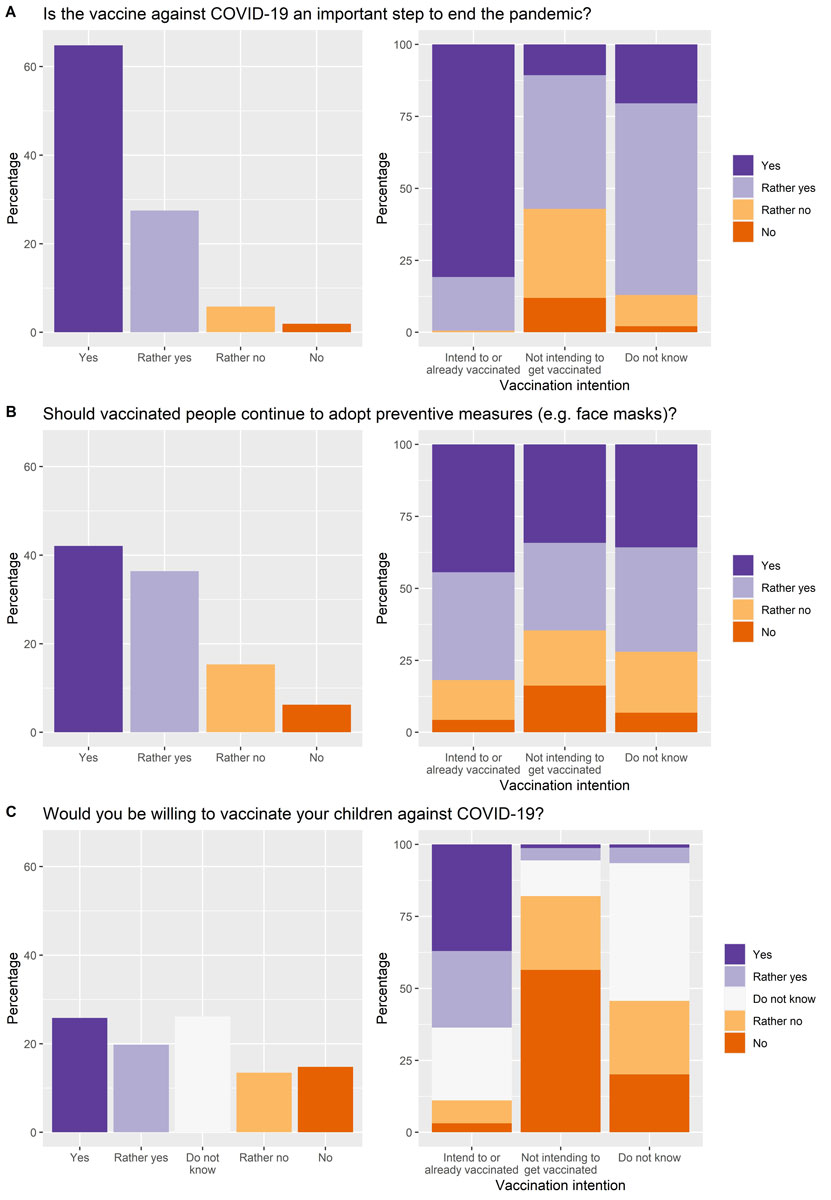

General perception of COVID-19 vaccination usefulness

A large majority (92.3%) agreed or rather agreed that COVID-19 vaccination was an important step to end the pandemic. When this was stratified by vaccination intention, those willing to or already vaccinated agreed the most with this statement (99.4%), although even of those not intending to get vaccinated, a majority (57.1%) acknowledged the importance of vaccination at (fig. 2A). Similarly, a majority of participants (78.5%) considered that vaccinated individuals should continue following preventive measures such as wearing face masks. Individuals willing to or already vaccinated were more likely to agree with this statement (81.9%) when compared with those not willing to get vaccinated (64.6%) (fig. 2B).

Figure 2 A. Proportion of participants agreeing that the COVID-19 vaccine is an important step to end the pandemic, in the overall sample (left) and stratified by vaccination intention (right). B. Proportion of participants agreeing that vaccinated individuals should continue to adopt preventive measures, in the overall sample (left) and stratified by vaccination intention (right). C. Proportion of participants willing to vaccinate their children, in the sample of participants with children under 18 years old (left) and stratified by vaccination intention (right).

Willingness to vaccinate children

Participants with children under the age of 18 (n = 1339) were asked whether they would be willing to have their children vaccinated against COVID-19 if it was recommended by public health authorities. Less than half (45.6%) agreed or rather agreed, and approximately one quarter did not know (fig. 2C). When these data were stratified by vaccination intention for oneself, those intending or rather intending to get vaccinated were mainly willing to have their children vaccinated (63.6%), whereas among participants not intending to get vaccinated or not yet sure, they were only 5.6% and 6.5%, respectively. Importantly, a high proportion of parents intending to get vaccinated (25.3%) and not yet sure about their intention (47.8%) were still undecided regarding vaccination of their children against COVID-19. These results were also stratified by parents’ education level and children’s age (the youngest child’s age was considered for parents with more than one child), showing the highest willingness rate for children’s vaccination among the most (50.5%) and the least (46.2%) educated, and an apparent gradient in willingness with increasing children’s age from 6 years old (between 38.6% for children aged 6 to 10, to 55.9% for children aged 16 to 18). These results are detailed in supplementary table S3.

Reasons for COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and refusal

Main reasons for intending to get vaccinated and for refusing vaccination are listed in table 1. The most common reasons reported by participants were the desire to "get back to normal" (78.4%), and to protect themselves (75.4%), as well as their community and/or society (70.1%) against the risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2.

Table 1

Reasons to get vaccinated, reasons for accepting or refusing vaccination, and reasons that might change participants’ minds.

|

Reasons to get vaccinated (if vaccination intention = yes / rather yes) (n = 2379

a

)

|

n (%)

|

| Desire to "get back to normal" |

1866 (78.4) |

| Protect myself against infection |

1794 (75.4) |

| Protect the community/society |

1667 (70.1) |

| Desire to travel |

1637 (68.8) |

| Protect those close to me |

1510 (63.5) |

| Adherence to public health recommendations |

1145 (48.1) |

| Living or working with vulnerable people |

311 (13.1) |

| At risk of infection at the workplace |

280 (11.8) |

| At risk of complications due to age |

206 (8.7) |

| At risk of complications due to health state |

138 (5.8) |

| Vaccine recommended by healthcare professional |

107 (4.5) |

| At risk for other reasons |

72 (3) |

| Employer required vaccination |

40 (1.7) |

|

Reasons for refusing vaccination (if vaccination intention = no / rather no) (n = 562)

|

n (%)

|

| Prefer waiting |

303 (53.9) |

| – Waiting for additional information |

162 (53.5) |

| – Give priority to more vulnerable people |

73 (24.1) |

| – Waiting for more people to get vaccinated |

47 (15.5) |

| – Waiting for my serological test result |

13 (4.3) |

| Not afraid of getting infected |

155 (27.6) |

| – Not at risk of complications |

88 (56.8) |

| – I protect myself |

25 (16.1) |

| – I have antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 |

20 (12.9) |

| – COVID-19 is a trivial disease |

13 (8.4) |

| Preference for other preventive measures |

154 (27.4) |

| – Preference for natural/traditional treatments |

50 (32.5) |

| – Preference for natural immunity |

46 (29.9) |

| – Preference for other means of protection |

40 (26) |

| Worried or afraid to get vaccinated |

137 (24.4) |

| – Afraid of long-term side effects |

71 (51.8) |

| – Vaccine developed too fast |

49 (35.8) |

| – Distrust in biological mechanism of the vaccine |

14 (10.2) |

| Feel protected because previously infected by SARS-CoV-2 |

133 (23.7) |

| Believe that vaccine doesn’t prevent transmission |

117 (20.8) |

| Against vaccines in general |

76 (13.5) |

| The pandemic situation is improving |

22 (3.9) |

| Can’t get vaccinated for medical reasons |

6 (1.1) |

|

If no / rather no, reasons that may change participants’ minds (n = 562)

|

|

| More reliable information on vaccine’s efficacy |

289 (51.4) |

| Scientific results showing low risk of side effects |

284 (50.5) |

| Mandatory vaccination for certain situations (e.g., travel) |

188 (33.5) |

| Deterioration of the pandemic situation |

69 (12.3) |

| Better communication by authorities |

54 (9.6) |

| Many people in Switzerland getting vaccinated |

24 (4.3) |

| Reassuring information in the media or social media |

21 (3.7) |

| Friends or relatives getting vaccinated |

13 (2.3) |

| Will not change mind |

69 (12.3) |

Among those not intending to get vaccinated, the most common reason was the "preference to wait", selected by 53.9% of participants. Other common reasons for refusing vaccination were not being afraid of being infected by SARS-CoV-2 (27.6%), the preference for other preventive measures (27.4%), worry or fear of getting vaccinated (24.4%), feeling protected by a previous infection with SARS-CoV-2 (23.7%) and believing that the vaccine does not prevent transmission of the virus (20.8%). Overall, 13.5% of participants not intending to get vaccinated stated being against vaccines in general.

Participants who did not intend to get vaccinated against COVID-19 were additionally asked which elements would change their minds in favour of vaccination. More than half indicated that more reliable information on vaccine efficacy and scientific results showing a low risk of side effects might make them more favourable towards getting vaccinated, and 33.5% reported that making vaccination mandatory in certain contexts (e.g., traveling) would have that effect. Overall, 12.3% of those not willing to get vaccinated stated that they would not change their minds.

Change in vaccination intention

Overall, in the 3 months preceding the questionnaire, 21.9% of all participants declared a change in intention to get vaccinated against COVID-19, with most becoming more favourable towards vaccination (19.8%) (table 2). Of note, those participants who declared still being ambivalent towards vaccination ("do not know") had mostly changed their minds in favour of vaccination (20.5% vs 5.2%), whereas those who did not intend to get vaccinated became more or less in favour of vaccination in more equal proportions (5.9% vs 6.8%, respectively).

Among the participants who changed their mind in the past 3 months, those more in favour of vaccination indicated the change in the pandemic situation (60.9%), information shared by public health authorities (49.1%) and new measures in place (e.g., regarding travel) (42.7%) as main reasons for this change. On the other hand, participants who became less in favour of vaccination did so mainly due to the information shared in the media (51.2%), by public health authorities (41.9%), as well as a change in the pandemic situation (33.7%) (table 3).

Table 2Change in intention to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in the past 3 months.

|

Vaccination intention

|

|

Change in intention to get vaccinated

|

Overall

(n = 4067), n (%)

|

Vaccinated or intend to get vaccinated,

n (%)

|

No intention to get vaccinated,

n (%)

|

Don’t know

,n (%)

|

| No |

3176 (78.1) |

2369 (76.9) |

491 (87.4) |

316 (74.3) |

| More in favour of vaccination |

805 (19.8) |

685 (22.2) |

33 (5.9) |

87 (20.5) |

| Less in favour of vaccination |

86 (2.1) |

26 (0.8) |

38 (6.8) |

22 (5.2) |

Table 3Reasons for change in vaccination intention in the past 3 months.

|

Reasons for change in intention

|

More in favour of vaccination (n = 805), n (%)

|

Less in favour of vaccination (n = 86), n (%)

|

| Change in the pandemic situation |

490 (60.9) |

29 (33.7) |

| Information shared by public health authorities |

395 (49.1) |

36 (41.9) |

| New measures in place (e.g., regarding travel) |

344 (42.7) |

18 (20.9) |

| Scientific developments |

313 (38.9) |

13 (15.1) |

| Information in the media |

190 (23.6) |

44 (51.2) |

| Advice from relatives or friends |

186 (23.1) |

12 (14) |

| Arrival of a new vaccine |

112 (13.9) |

12 (14) |

| Information in social media |

17 (2.1) |

11 (12.8) |

Drivers of vaccination intention

Vaccination intention differed by demographic characteristics, with men compared to women (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.44, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.16–1.80) and older adults compared to adults aged 18 to 34 years (aOR 1.80, 95% CI 1.222.63, and aOR 5.35, 95% CI 3.40–8.43, for 50–64 and 65 years and older, respectively) more likely to accept COVID-19 vaccination (table 4).

Table 4Association of sociodemographic and health-related factors with vaccination intention.

|

Sociodemographic characteristics

|

Intention to get vaccinated*

|

p-value

|

Age- and sex-adjusted OR

†

(95% CI)

|

p-value

‡

|

Multivariate OR

†

§

(95% CI)

|

p-value

‡

|

|

Yes / rather yes/ already vaccinated

(n = 3080),

n (%)

|

No / rather no

(n = 562),

n (%)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sex

1

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

| – Female |

1631 (53) |

357 (63.5) |

|

Ref |

|

Ref |

|

| – Male |

1440 (46.8) |

205 (36.5) |

|

1.42 (1.17–1.71)

|

<0.001 |

1.44 (1.16–1.80)

|

0.001 |

| – Intersex |

9 (0.3) |

0 (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age category

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

| – 18–34 |

285 (9.3) |

93 (16.5) |

|

Ref |

|

|

|

| – 35–49 |

803 (26.1) |

217 (38.6) |

|

1.21 (0.91–1.59) |

0.189 |

1.17 (0.79–1.70) |

0.423 |

| – 50–64 |

1081 (35.1) |

194 (34.5) |

|

1.78 (1.34–2.35)

|

<0.001 |

1.80 (1.22–2.63)

|

0.003 |

| – ≥ 65 |

911 (29.6) |

58 (10.3) |

|

4.94 (3.48–7.08)

|

<0.001 |

5.35 (3.40–8.43)

|

<0.001 |

|

Education

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

| – Tertiary |

2093 (68) |

315 (56) |

|

Ref |

|

|

|

| – Secondary |

387 (12.6) |

89 (15.8) |

|

0.65 (0.5–0.86)

|

0.002 |

0.65 (0.47–0.91)

|

0.010 |

| – Apprenticeship |

485 (15.7) |

135 (24) |

|

0.42 (0.33–0.53)

|

<0.001 |

0.53 (0.40–0.70)

|

<0.001 |

| – Compulsory/none |

109 (3.5) |

22 (3.9) |

|

0.69 (0.43–1.15) |

0.139 |

0.78 (0.44–1.50) |

0.435 |

|

Household income

2

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

| – Low |

347 (11.3) |

89 (15.8) |

|

Ref |

|

|

|

| – Middle |

1578 (51.2) |

286 (50.9) |

|

1.33 (1.01–1.74)

|

0.042 |

1.23 (0.93–1.62) |

0.147 |

| – High |

495 (16.1) |

46 (8.2) |

|

3.12 (2.13–4.64)

|

<0.001 |

2.59 (1.74–3.88)

|

<0.001 |

| – Don’t know/don’t wish to answer |

569 (18.5) |

107 (19) |

|

– |

– |

|

|

| – NA |

91 (3) |

34 (6) |

|

– |

– |

|

|

|

Chronic disease

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

| – Yes |

897 (29.1) |

96 (17.1) |

|

Ref |

|

|

|

| – No |

2183 (70.9) |

466 (82.9) |

|

0.62 (0.49–0.79)

|

<0.001 |

0.58 (0.44–0.76)

|

<0.001 |

|

Residential area

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

| – Rural |

483 (15.7) |

132 (23.5) |

|

Ref |

|

|

|

| – Semi–urban |

1088 (35.3) |

188 (33.5) |

|

1.6 (1.24–2.06)

|

<0.001 |

1.56 (1.15–2.09)

|

0.004 |

| – Urban |

1508 (49) |

242 (43.1) |

|

1.92 (1.5–2.44)

|

<0.001 |

1.96 (1.47–2.61)

|

<0.001 |

|

Employment status

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

| – Employee |

1554 (50.5) |

352 (62.6) |

|

Ref |

|

|

|

| – Retired |

935 (30.4) |

62 (11) |

|

1.55 (0.94–2.61) |

0.091 |

1.35 (0.77–2.45) |

0.310 |

| – Student |

120 (3.9) |

25 (4.4) |

|

1.76 (1.07–2.98)

|

0.031 |

1.98 (0.71–7.09) |

0.231 |

| – Independent |

229 (7.4) |

53 (9.4) |

|

0.83 (0.6–1.16) |

0.258 |

0.9 (0.62–1.35) |

0.603 |

| – Househusband or housewife |

131 (4.3) |

29 (5.2) |

|

1.07 (0.7–1.67) |

0.768 |

1.11 (0.66–1.93) |

0.713 |

| – Unemployed |

81 (2.6) |

33 (5.9) |

|

0.56 (0.37–0.87)

|

0.009 |

0.65 (0.39–1.10) |

0.098 |

| – Long–term sickleave |

29 (0.9) |

8 (1.4) |

|

0.79 (0.37–1.89) |

0.572 |

0.94 (0.38–2.66) |

0.898 |

|

Living conditions

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

| – Alone |

460 (14.9) |

79 (14.1) |

|

Ref |

|

|

|

| – Single parent with children |

145 (4.7) |

52 (9.3) |

|

0.7 (0.46–1.06) |

0.091 |

0.75 (0.48–1.20) |

0.224 |

| – With partner |

1051 (34.1) |

122 (21.7) |

|

1.26 (0.92–1.72) |

0.147 |

1.32 (0.93–1.86) |

0.113 |

| – With partner and children |

1213 (39.4) |

252 (44.8) |

|

1.22 (0.9–1.64) |

0.187 |

1.28 (0.91–1.79) |

0.152 |

| – Shared apartment |

210 (6.8) |

57 (10.1) |

|

1.11 (0.72–1.7) |

0.639 |

6.08 (1.66–39.5)

|

0.019 |

|

Smoking status

|

|

|

0.035 |

|

|

|

|

| – Current smoker |

426 (13.8) |

90 (16) |

|

Ref |

|

|

|

| – Former smoker |

1014 (32.9) |

155 (27.6) |

|

1.12 (0.84–1.5) |

0.443 |

1.01 (0.72–1.40) |

0.968 |

| – Never smoker |

1639 (53.2) |

317 (56.4) |

|

1.1 (0.84–1.42) |

0.483 |

0.98 (0.72–1.32) |

0.879 |

|

Previous SARS-CoV-2 infection

3

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

| – Negative |

2573 (83.5) |

408 (72.6) |

|

Ref |

|

|

|

| – Positive |

507 (16.5) |

154 (27.4) |

|

0.61 (0.49–0.76)

|

<0.001 |

0.62 (0.49–0.80)

|

<0.001 |

|

Perceived severity of COVID-19

4

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

| – Extremely severe |

158 (7) |

4 (1) |

|

Ref |

|

|

|

| – Very severe |

608 (27) |

27 (6.6) |

|

0.63 (0.18–1.66) |

0.402 |

0.17 (0.01–0.82)

|

0.084 |

| – Severe |

886 (39.3) |

117 (28.5) |

|

0.24 (0.07–0.58)

|

0.006 |

0.07 (0.00–0.30)

|

0.007 |

| – Rather severe |

570 (25.3) |

225 (54.7) |

|

0.08 (0.03–0.21)

|

<0.001 |

0.02 (0.00–0.10)

|

<0.001 |

| – Not at all severe |

33 (1.5) |

38 (9.2) |

|

0.03 (0.01–0.07)

|

<0.001 |

0.01 (0.00–0.04)

|

<0.001 |

|

Perceived contagiousness of COVID-19

4

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

| - Extremely contagious |

296 (13.1) |

12 (2.9) |

|

Ref |

|

|

|

| – Very contagious |

1273 (56.5) |

170 (41.4) |

|

0.3 (0.15–0.52)

|

<0.001 |

0.26 (0.12–0.51)

|

<0.001 |

| – Contagious |

448 (19.9) |

151 (36.7) |

|

0.12 (0.06–0.21)

|

<0.001 |

0.10 (0.04–0.20)

|

<0.001 |

| – Rather contagious |

236 (10.5) |

75 (18.2) |

|

0.13 (0.07–0.24)

|

<0.001 |

0.12 (0.05–0.26)

|

<0.001 |

| – Not at all contagious |

2 (0.1) |

3 (0.7) |

|

0.04 (0–0.26)

|

0.001 |

0.04 (0.00–0.42)

|

0.010 |

|

Vaccine hesitancy

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

| – Not hesitant |

2052 (66.6) |

277 (49.3) |

|

Ref |

|

|

|

| – Hesitant |

1028 (33.4) |

285 (50.7) |

|

0.44 (0.36–0.53)

|

<0.001 |

0.42 (0.34–0.53)

|

<0.001 |

People who had done apprenticeships (aOR 0.53, 95% CI 0.40–0.70) or had a secondary education (aOR 0.65, 95% CI 0.47–0.91) were less likely to intend to get vaccinated than people having completed tertiary education. The odds did not differ significantly for individuals with compulsory or no formal education. Further, the odds of vaccination willingness were higher in individuals with higher income compared with those with low income (aOR 2.59, 95% CI 1.74–3.88), and in participants residing in semi-urban (aOR 1.56, 95% CI 1.15–2.09) and urban (aOR 1.96, 95% CI 1.47–2.61) areas compared with rural areas. In the multivariable analysis, there was no association between employment status and vaccination intention.

Vaccination intention also differed by clinical characteristics, with people without any chronic disease less likely to intend to get vaccinated than those reporting at least one chronic disease (aOR 0.58, 95% CI 0.44–0.76), as well as individuals who had been infected by SARS-CoV-2 compared with those who had never had COVID-19 (aOR 0.62, 95% CI 0.49–0.80).

People who had a lower perception of the severity and contagiousness of COVID-19 were less likely to accept vaccination than those with a higher risk perception, with an decreasing trend of vaccination intention from those grading COVID-19 as "very severe" (aOR 0.17, 95% CI 0.01–0.82) to "not at all severe" (aOR 0.01, 95% CI 0.00–0.04) compared with "extremely severe", and from "very contagious" (aOR 0.26, 95% CI 0.12–0.51) to "not at all contagious" (aOR 0.04, 95% CI 0.00–0.42) compared with "extremely contagious". Finally, vaccine hesitancy was negatively associated with vaccination intention (aOR 0.42, 95% CI 0.34–0.53), although 33.4% of those intending to get vaccinated against COVID-19 were categorised as "vaccine hesitant", and almost half of those not intending to get vaccinated were not generally vaccine hesitant.

Discussion

This study carried out in the canton of Geneva showed an overall COVID-19 vaccination acceptance standardised to the age, sex and education distribution of the population of Geneva of 71.8%, including those already vaccinated, and those who intended or rather intended to get vaccinated once eligible. This rate of vaccine acceptance was consistent with previous studies carried out in other developed countries, such as the United states (67%) [29], Japan (62.1%) [30], Ireland (65%) and the United Kingdom (between 69% to 86% across studies) [31, 32]. However, the range of vaccine acceptance has been seen to vary widely between countries, from 29.4% reported in a study in Jordan, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, to 86% in the United Kingdom [32].

The most frequently provided reasons for intending to get vaccinated were to protect oneself, to protect the community and to return to a normal life. These reasons were similar to those obtained in other countries [32]. Interestingly, 80% of those willing to get vaccinated were of the opinion that vaccinated people should continue to follow preventive measures against viral spread. This may reflect a generally higher commitment of these participants to respecting public authority recommendations, which imposed the same preventive measures for vaccinated and non-vaccinated individuals alike at the time of the survey.

In our study, vaccination intentions differed depending on sociodemographic factors. Our results showed that men were more willing to get vaccinated than women. This is in line with previous studies on vaccination acceptance [32]. Indeed, women have been reported to adopt more negative opinions about vaccination, whereas men have been reported to perceive a higher risk of the disease and to be less easily influenced by rumours surrounding COVID-19 [32]. Only one study conducted in the United States reported a lower acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination in men than in women [33].

Consistent with previous findings, this study found that older individuals were more willing to get vaccinated against COVID-19 than younger individuals [32]. This could be attributed to the fact that older individuals are at increased risk of mortality and of severe forms of the disease, and had access to vaccination at the time of the survey. However, this finding could evolve rapidly over time as, since the time of this survey, COVID-19 vaccination has now been made available to all individuals aged over 5 years in Switzerland.

In addition, our study showed that high education level, high income status, and having a chronic disease were associated with higher vaccination acceptance, which is in line with previously published studies [32]. Residing in urban or semi-urban areas was associated with vaccination acceptance in our study, whereas other studies conducted in different settings showed conflicting results regarding residential area [32]. Although targeted communication directed at clinically vulnerable populations during the vaccination campaign seems to have been successful, with increased vaccination acceptance among participants with a chronic disease, our results suggest that tailored communication strategies should also focus on socially vulnerable populations [34].

Furthermore, participants who had already been infected with SARS-CoV-2 (assessed either by a serological test or a PCR test) were less willing to get vaccinated, even though vaccination was also recommended for previously infected individuals in Switzerland at the time of the survey. To our knowledge, this is the first survey to assess vaccination acceptance in association with serological status. Being aware of these associations may provide guidance for stakeholders and health professionals to target hesitant people and potentially adapt or better explain vaccination strategies.

Although 14% of participants in the current study expressed unwillingness to get vaccinated, 10% of participants remained undecided regarding their vaccination intention. Making up almost one fourth of all participants, this combined group represents a threat to the success of vaccination campaigns against COVID-19 and the achievement of a high immunisation coverage. The main reasons for participants’ refusal of vaccination were concerns about safety and efficacy, and a large proportion of those not intending to get vaccinated reported preferring to wait to have more data about potential side effects, including in the long term. Previous studies carried out worldwide have also identified doubts about the vaccine’s efficacy and safety among the main reasons for vaccine hesitancy [32, 35]. High media coverage of the vaccination campaign and increased use of social networks may have further fueled controversies such as the potential risk of thromboembolic events following vaccination, with a heavy impact on vaccination acceptance [36].

Our results show that, at the time of the survey, less than half of participants with children were willing to have their children vaccinated against COVID-19 if it were recommended by public health authorities. This is generally in line with results from other countries [37–40], which have shown parental acceptance varying between 36.3% in Turkey [39] and 60.4% in Canada [37]. Consistent with other studies, child vaccination intention varied according to children’s age [36], with acceptance increasing with the child’s age from 6 years old in our study, and to educational level [37–39], with a higher acceptance rate among parents with a tertiary education and those with a compulsory education only. Importantly, COVID-19 vaccination was not yet authorised in children under 16 years old at the time of the survey, whereas it is now recommended for those aged 5 years and older in Switzerland, which may strongly impact parental acceptance. Also, willingness to vaccinate one’s children may increase as more evidence is made available regarding potential long-term sequelae of COVID-19 in children and adolescents [41].

In our study, 33.4% of those intending to get vaccinated against COVID-19 or who were already vaccinated were categorised as generally "vaccine hesitant", whereas almost half of those not intending to get vaccinated were not generally vaccine hesitant. This result suggests that COVID-19 vaccination does not seem to be perceived in the same way as other recommended vaccines. Although it is already known that urgently released vaccines are received with greater scepticism than established or well-known vaccines [32], COVID-19 vaccines may trigger even higher distrust due to their unusually rapid development.

Implications for public health policies

Results from this study provide a clear insight of sociodemographic subgroups that remain hesitant about or refuse COVID-19 vaccination. Interestingly, more than half of those not intending to get vaccinated against COVID-19 agreed that the vaccine was an important step to end the pandemic. As suggested by our results, these individuals may be more likely to change their minds if reassured about the safey of vaccines. Although there is sufficient clinical evidence about the efficacy, safety and side effects of authorised COVID-19 vaccines, this evidence needs to be better communicated and disseminated among the general population in order to alleviate common concerns.

Further, our results showed that information shared by public health authorities could lead to change in intention both in favour and against vaccination in similar proportions. These results highlight the importance of improving communication at a population level. Fortunately, empirical data showed that building vaccination trust among hesitant individuals is possible with effective communication strategies, which could be based on social marketing campaigns at the population level [35,42] or on targeted campaigns tailored to specific subgroups [43]. Several mass information campaigns have already been carried out by health authorities in the canton of Geneva since the beginning of the vaccination programme. Our results highlight the importance of specifically targeting groups at higher risk of vaccine hesitancy, such as young adults and socially disadvantaged populations. Targeted vaccination campaigns in schools, universities and venues such as shopping malls or nightclubs, have the potential to increase vaccination rates in young adults. Types of communication should also be tailored to specific population subgroups. For instance, a study in Zurich, Switzerland, has shown that young people were more likely to respond positively to vaccination campaigns if they perceived information to be delivered in an objective and balanced manner [44].

Accordingly, public health organisations, healthcare professionals and digital platforms should collaborate to guarantee the availability of accessible and accurate information. In this regard, our results were presented to policy makers of the canton of Geneva in order to inform them of COVID-19 vaccination acceptance among the general population. This cross-sectional survey will be repeated over time to guide public health policies in case the COVID-19 vaccination rate reaches a plateau, particularly among sub-groups of the population.

Strengths and limitations

The main strengths of this study are its large sample size with all adult ages represented, as well as the availability of data on sociodemographic (age, sex, education level, income) and health-related characteristics (serological status, chronic diseases, smoking status), which allowed stratification of COVID-19 vaccination acceptance according to these factors. Very little research has been conducted on the drivers of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance now that vaccination is available to the general population. Indeed, most previous studies carried out globally were conducted in periods when COVID-19 vaccines were not available or accessible only to certain groups, such as healthcare workers or key workers [45, 46]. It is also of utmost importance to investigate the factors influencing perception of COVID-19 vaccination at the local level, as vaccination hesitancy may be widely influenced by regional and cultural factors.

Several limitations of our study should be acknowledged. Although the participation rate in this study was high, generalisation of the results presented here requires caution as our sample is not completely representative of the general population of the canton of Geneva. Our participants were generally older and more educated than the general population. This is expected as participation in surveys is generally skewed towards women, and older and more educated individuals [47]. Compared to other surveys, the fact that all participants originally came for a clinical visit may have reduced this bias. On the other hand, the fact that the sample underwent a double or triple selection from the original Bus Santé study into the Specchio-COVID19 cohort may have further selected health-conscious, higher educated participants. We mitigated this by standardising our main outcome to the age, sex and level of education distribution in the population of Geneva, and adjusted our results for important sociodemographic characteristics. However, participation required French literacy, internet access and digital literacy, potentially excluding part of the general population. Further, the self-administered online format of the questionnaire is at inherent risk of information bias.

The cross-sectional survey design represents a snapshot in time, rather than the evolving landscape of the public’s attitudes to COVID-19 vaccination. Vaccine hesitancy, perceptions and concerns may change over time. Our results should be interpreted with consideration of this specific time period when vaccination was only accessible to people aged above 65 years or to people with chronic diseases at risk of severe forms of COVID-19. Our survey will be repeated over time to provide updated information and adjust public health messages as appropriate. Furthermore, other factors potentially impacting vaccination hesitancy were not investigated, such as origin, and religious or political views, which are likely to influence individual perceptions and behaviour. Another aspect that could be worth exploring is the "imitation effect" or the influence of one’s social network on vaccination perception.

Finally, we need to keep in mind that acceptance or intent does not automatically translate into actual behaviour. Despite a high vaccination rate to date, with more than half of the population of the canton of Geneva vaccinated with at least one dose [48], there is a risk that the vaccination rate could reach a plateau, especially in the context of summer holidays and the slowdown of the pandemic in past months. Once vaccination against COVID-19 of all willing individuals has been achieved, increased efforts will have to be put in place to reach the more reluctant part of the population and those with less access to information about the vaccination campaign.

Conclusion

Our study found that 71.8% of the adult population the canton of Geneva would accept COVID-19 vaccination or was already vaccinated at the time of the survey. However, sociodemographic variations in rates of acceptance were evidenced that need to be carefully addressed. Policy makers and stakeholders should provide reassuring messages about side effects and effectiveness of the vaccination. This cross-sectional survey will be repeated approximately every 6 months in order to follow the level of COVID-19 vaccination acceptance over time, which may be influenced by new incentives such as the establishment of a COVID-19 vaccine certificate or new policies for traveling, as well as the pandemic progression and new outbreaks. These data may help policy makers to develop effective and targeted communication strategies.

Data availability statement

Individual study data that underlie the results reported in this article can be made available to the scientific community after deidentification and upon submission of a data request application to the investigator board via the corresponding author. The protocol of the overarching study (Specchio-COVID19) can be found at https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.07.14.21260489v1.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants, without whom this study would not have been possible.

Specchio-COVID19 study group: Isabelle Arm-Vernez, Andrew S Azman, Fatim Ba, Oumar Aly Ba, Delphine Bachmann, Jean-François Balavoine, Michael Balavoine, Hélène Baysson, Lison Beigbeder, Julie Berthelot, Patrick Bleich, Gaëlle Bryand, François Chappuis, Prune Collombet, Delphine Courvoisier, Alain Cudet, Carlos de Mestral Vargas, Paola D'Ippolito, Richard Dubos, Roxane Dumont, Isabella Eckerle, Nacira El Merjani, Antoine Flahault, Natalie Francioli, Marion Frangville, Idris Guessous, Séverine Harnal, Samia Hurst, Laurent Kaiser, Omar Kherad, Julien Lamour, Pierre Lescuyer, François Lhuissier, Fanny-Blanche Lombard, Andrea Jutta Loizeau, Elsa Lorthe, Chantal Martinez, Lucie Ménard, Lakshmi Menon, Ludovic Metral-Boffod, Benjamin Meyer, Alexandre Moulin, Mayssam Nehme, Natacha Noël, Francesco Pennacchio, Javier Perez-Saez, Giovanni Piumatti, Didier Pittet, Jane Portier, Klara M Posfay-Barbe, Géraldine Poulain, Caroline Pugin, Nick Pullen, Zo Francia Randrianandrasana, Aude Richard, Viviane Richard, Frederic Rinaldi, Jessica Rizzo, Khadija Samir, Claire Semaani, Silvia Stringhini, Stéphanie Testini, Guillemette Violot, Nicolas Vuilleumier, Ania Wisniak, María-Eugenia Zaballa

Author contributions: SS, IG and HB designed the study. HB, AW, MN and SS designed the questionnaire for the survey. MZ, FP, HB and AW were involved in participant recruitment and implementation of the survey. NP conducted statistical analyses of the data. AW and HB drafted the manuscript. All authors participated to analysis interpretation and approved the final manuscript.

Appendix

The supplementary material is available in the PDF version of the article.

Dr Ania Wisniak

Unit of Population Epidemiology

Geneva University Hospitals

Rue Gabrielle-Perret-Gentil 4

CH-1211 Genève

ania.wisniak[at]hcuge.ch

References

1.

Polack FP

,

Thomas SJ

,

Kitchin N

,

Absalon J

,

Gurtman A

,

Lockhart S

, et al.; C4591001 Clinical Trial Group

. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec;383(27):2603–15. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2034577

2.

Freeman D

,

Loe BS

,

Chadwick A

,

Vaccari C

,

Waite F

,

Rosebrock L

, et al.

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: the Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychol Med. 2020 Dec;•••:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720005188

3.

Eguia H

,

Vinciarelli F

,

Bosque-Prous M

,

Kristensen T

,

Saigí-Rubió F

. Spain’s Hesitation at the Gates of a COVID-19 Vaccine. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Feb;9(2):170. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9020170

4.

Afifi TO

,

Salmon S

,

Taillieu T

,

Stewart-Tufescu A

,

Fortier J

,

Driedger SM

. Older adolescents and young adults willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine: implications for informing public health strategies. Vaccine. 2021 Jun;39(26):3473–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.026

5.

Razai MS

,

Chaudhry UA

,

Doerholt K

,

Bauld L

,

Majeed A

. Covid-19 vaccination hesitancy. BMJ. 2021 May;373(1138):n1138. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1138

6.

Elhadi M

,

Alsoufi A

,

Alhadi A

,

Hmeida A

,

Alshareea E

,

Dokali M

, et al.

Knowledge, attitude, and acceptance of healthcare workers and the public regarding the COVID-19 vaccine: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2021 May;21(1):955. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10987-3

7.

Dreisinger N

,

Lim CA

. Resurgence of Vaccine-Preventable Disease: Ethics in the Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019 Sep;35(9):651–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001917

8.

Feemster KA

,

Szipszky C

. Resurgence of measles in the United States: how did we get here? Curr Opin Pediatr. 2020 Feb;32(1):139–44. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000845

9.

Papachrisanthou MM

,

Davis RL

. The Resurgence of Measles, Mumps, and Pertussis. J Nurse Pract. 2019 Jun;15(6):391–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2018.12.028

10.

World Health Organization

. Ten threats to global health in 2019 [Internet]. who.int. 2019 [cited 2021 May 3]. Available from: https://www.who.int/vietnam/news/feature-stories/detail/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019

11.

Kalichman SC

,

Eaton LA

,

Earnshaw VA

,

Brousseau N

. Faster than warp speed: early attention to COVD-19 by anti-vaccine groups on Facebook. J Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Apr 9 [cited 2021 Apr 19];(fdab093). Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab093

12.

Burki T

. The online anti-vaccine movement in the age of COVID-19. Lancet Digit Health. 2020 Oct;2(10):e504–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30227-2

13.

Johnson NF

,

Velásquez N

,

Restrepo NJ

,

Leahy R

,

Gabriel N

,

El Oud S

, et al.

The online competition between pro- and anti-vaccination views. Nature. 2020 Jun;582(7811):230–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2281-1

14. Maladie à coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). Rapport sur la situation épidémiologique en Suisse et dans la Principauté de Liechtenstein – semaine 51 (14.12-20.12.2020). Etat 23.12.2020. [Internet]. Switzerland: Federal Office of Public Health; 2020 Dec [cited 2021 May 3]. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/krankheiten/ausbrueche-epidemien-pandemien/aktuelle-ausbrueche-epidemien/novel-cov/situation-schweiz-und-international.html#-1680104524

15.

Stringhini S

,

Zaballa ME

,

Perez-Saez J

,

Pullen N

,

de Mestral C

,

Picazio A

, et al.; Specchio-COVID19 Study Group

. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies after the second pandemic peak. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 May;21(5):600–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00054-2

16.

Baden LR

,

El Sahly HM

,

Essink B

,

Kotloff K

,

Frey S

,

Novak R

, et al.; COVE Study Group

. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb;384(5):403–16. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2035389

17. Campagne de vaccination à Genève [Internet]. ge.ch. [cited 2021 May 25]. Available from: https://www.ge.ch/node/23775

18.

Knotz CM

,

Fossati F

,

Gandenberger M

,

Bonoli G

,

Trein P

,

Varone F

. De nombreux Suisses ne veulent pas être vaccinés contre la COVID-19 - le manque de confiance dans la sécurité des vaccins en est la cause principale - DeFacto [Internet]. DeFacto Plus que des opinions. 2020 [cited 2021 May 3]. Available from: https://www.defacto.expert/2020/12/22/de-nombreux-suisses-ne-veulent-pas-etre-vaccines-contre-la-covid-19-le-manque-de-confiance-dans-la-securite-des-vaccins-en-est-la-cause-principale/?lang=fr

19.

Detoc M

,

Bruel S

,

Frappe P

,

Tardy B

,

Botelho-Nevers E

,

Gagneux-Brunon A

. Intention to participate in a COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial and to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in France during the pandemic. Vaccine. 2020 Oct;38(45):7002–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.041

20.

Sallam M

,

Dababseh D

,

Eid H

,

Al-Mahzoum K

,

Al-Haidar A

,

Taim D

, et al.

High Rates of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Association with Conspiracy Beliefs: A Study in Jordan and Kuwait among Other Arab Countries [Internet]. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Jan;9(1):42. [cited 2021 May 3] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7826844/ https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9010042

21.

Chou WS

,

Budenz A

. Considering Emotion in COVID-19 Vaccine Communication: Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy and Fostering Vaccine Confidence. Health Commun. 2020 Dec;35(14):1718–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1838096

22.

Baysson H

,

Pennacchio F

,

Wisniak A

,

Zaballa M-E

,

Collombet P

,

Joost S

, et al.

The Specchio-COVID19 study cohort: a web-based prospective study of SARS-CoV-2 serosurveys participants in the canton of Geneva (Switzerland). Submitted. 2021 Jun;

23.

Stringhini S

,

Wisniak A

,

Piumatti G

,

Azman AS

,

Lauer SA

,

Baysson H

, et al.

Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in Geneva, Switzerland (SEROCoV-POP): a population-based study. Lancet. 2020 Aug;396(10247):313–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31304-0

24.

Office Cantonal des Statistiques (OCSTAT)

. Statistiques cantonales - République et canton de Genève [Internet]. [cited 2021 Sep 8]. Available from: https://www.ge.ch/statistique/

25.

West EA

,

Anker D

,

Amati R

,

Richard A

,

Wisniak A

,

Butty A

, et al.; Corona Immunitas Research Group

. Corona Immunitas: study protocol of a nationwide program of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence and seroepidemiologic studies in Switzerland. Int J Public Health. 2020 Dec;65(9):1529–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01494-0

26.

Rey D

,

Fressard L

,

Cortaredona S

,

Bocquier A

,

Gautier A

,

Peretti-Watel P

, et al.; On Behalf Of The Baromètre Santé Group

. Vaccine hesitancy in the French population in 2016, and its association with vaccine uptake and perceived vaccine risk-benefit balance. Euro Surveill. 2018 Apr;23(17). https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.17.17-00816

27.

Schuster M

,

Eskola J

,

Duclos P

; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy

. Review of vaccine hesitancy: Rationale, remit and methods. Vaccine. 2015 Aug;33(34):4157–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.035

28.

Office Cantonal des Statistiques (OCSTAT)

. T 20.02.7.01 - Statistique cantonale du revenu et de la fortune des ménages - Quantiles du revenu annuel brut des ménages selon le type de ménage en 2015-2017 - Canton de Genève. 2020.

29.

Malik AA

,

McFadden SM

,

Elharake J

,

Omer SB

. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine. 2020 Sep;26:100495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100495

30.

Machida M

,

Nakamura I

,

Kojima T

,

Saito R

,

Nakaya T

,

Hanibuchi T

, et al.

Acceptance of a COVID-19 Vaccine in Japan during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Mar;9(3):210. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9030210

31.

Murphy J

,

Vallières F

,

Bentall RP

,

Shevlin M

,

McBride O

,

Hartman TK

, et al.

Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Nat Commun. 2021 Jan;12(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20226-9

32.

Al-Jayyousi GF

,

Sherbash MA

,

Ali LA

,

El-Heneidy A

,

Alhussaini NW

,

Elhassan ME

, et al.

Factors Influencing Public Attitudes towards COVID-19 Vaccination: A Scoping Review Informed by the Socio-Ecological Model. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 May;9(6):548. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9060548

33.

Hursh SR

,

Strickland JC

,

Schwartz LP

,

Reed DD

. Quantifying the Impact of Public Perceptions on Vaccine Acceptance Using Behavioral Economics. Front Public Health. 2020 Dec;8:608852. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.608852

34.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

. Rapid literature review on motivating hesitant population groups in Europe to vaccinate [Internet]. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2015 [cited 2021 Jun 28]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/media/en/publications/Publications/vaccination-motivating-hesistant-populations-europe-literature-review.pdf

35.

Neumann-Böhme S

,

Varghese NE

,

Sabat I

,

Barros PP

,

Brouwer W

,

van Exel J

, et al.

Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Eur J Health Econ. 2020 Sep;21(7):977–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-020-01208-6

36.

Ward J

. Enquête COVIREIVAC : les français et la vaccination [Internet]. Inserm (Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale), ORS (Observatoire régional de la santé); 2021 Jun [cited 2021 Jun 21]. Available from: http://www.orspaca.org/sites/default/files/enquete-COVIREIVAC-rapport.pdf

37.

Hetherington E

,

Edwards SA

,

MacDonald SE

,

Racine N

,

Madigan S

,

McDonald S

, et al.

SARS-CoV-2 vaccination intentions among mothers of children aged 9 to 12 years: a survey of the All Our Families cohort. CMAJ Open. 2021 May;9(2):E548–55. https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20200302

38.

Brandstetter S

,

Böhmer MM

,

Pawellek M

,

Seelbach-Göbel B

,

Melter M

,

Kabesch M

, et al.; KUNO-Kids study group

. Parents’ intention to get vaccinated and to have their child vaccinated against COVID-19: cross-sectional analyses using data from the KUNO-Kids health study. Eur J Pediatr. 2021 Nov;180(11):3405–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-021-04094-z

39.

Yılmaz M

,

Sahin MK

. Parents’ willingness and attitudes concerning the COVID-19 vaccine: A cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pract. 2021 Sep;75(9):e14364. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.14364

40.

Wang Z

,

She R

,

Chen X

,

Li L

,

Li L

,

Huang Z

, et al.

Parental acceptability of COVID-19 vaccination for children under the age of 18 years among Chinese doctors and nurses: a cross-sectional online survey. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021 Oct;17(10):3322–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.1917232

41.

Hageman JR

. Long COVID-19 or Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults. Pediatr Ann. 2021 Jun;50(6):e232–3. https://doi.org/10.3928/19382359-20210519-02

42.

Opel DJ

,

Diekema DS

,

Lee NR

,

Marcuse EK

. Social marketing as a strategy to increase immunization rates. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009 May;163(5):432–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.42

43.

Jarrett C

,

Wilson R

,

O’Leary M

,

Eckersberger E

,

Larson HJ

; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy

. Strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy - A systematic review. Vaccine. 2015 Aug;33(34):4180–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.040

44.

Leos-Toro C

,

Ribeaud D

,

Bechtiger L

,

Steinhoff A

,

Nivette A

,

Murray AL

, et al.

Attitudes Toward COVID-19 Vaccination Among Young Adults in Zurich, Switzerland, September 2020. Int J Public Health [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 8];0. Available from: https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/ijph.2021.643486/full

45.

Holzmann-Littig C

,

Braunisch MC

,

Kranke P

,

Popp M

,

Seeber C

,

Fichtner F

, et al.

COVID-19 vaccination acceptance among healthcare workers in Germany. medRxiv. 2021 Apr 23;2021.04.20.21255794.

46.

Verger P

,

Scronias D

,

Dauby N

,

Adedzi KA

,

Gobert C

,

Bergeat M

, et al.

Attitudes of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 vaccination: a survey in France and French-speaking parts of Belgium and Canada, 2020 [Internet]. Euro Surveill. 2021 Jan;26(3): [cited 2021 Jun 21] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7848677/ https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.3.2002047

47.

Reinikainen J

,

Tolonen H

,

Borodulin K

,

Härkänen T

,

Jousilahti P

,

Karvanen J

, et al.

Participation rates by educational levels have diverged during 25 years in Finnish health examination surveys. Eur J Public Health. 2018 Apr;28(2):237–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckx151

48.

Federal Office of Public Health

. COVID-19 Switzerland Information on the current situation, as of 21 June 2021 - Vaccine doses. [Internet]. 2021 Jun [cited 2021 Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.covid19.admin.ch/en/epidemiologic/vacc-doses