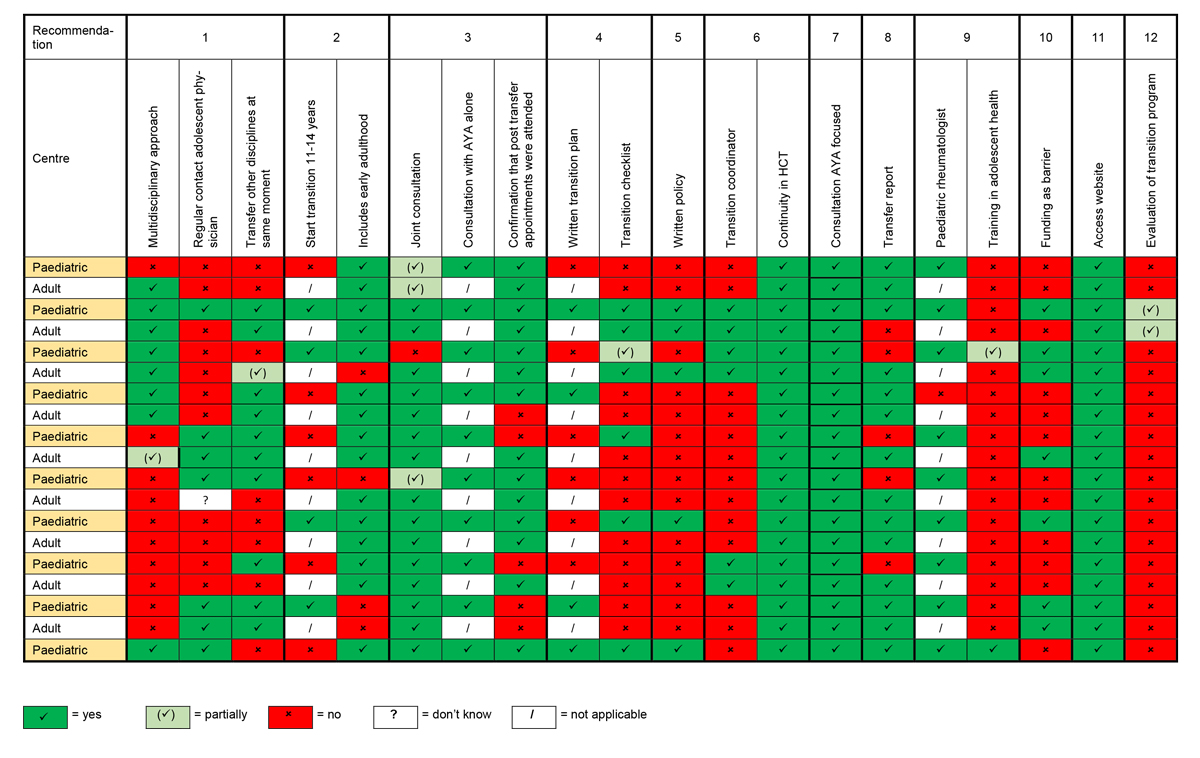

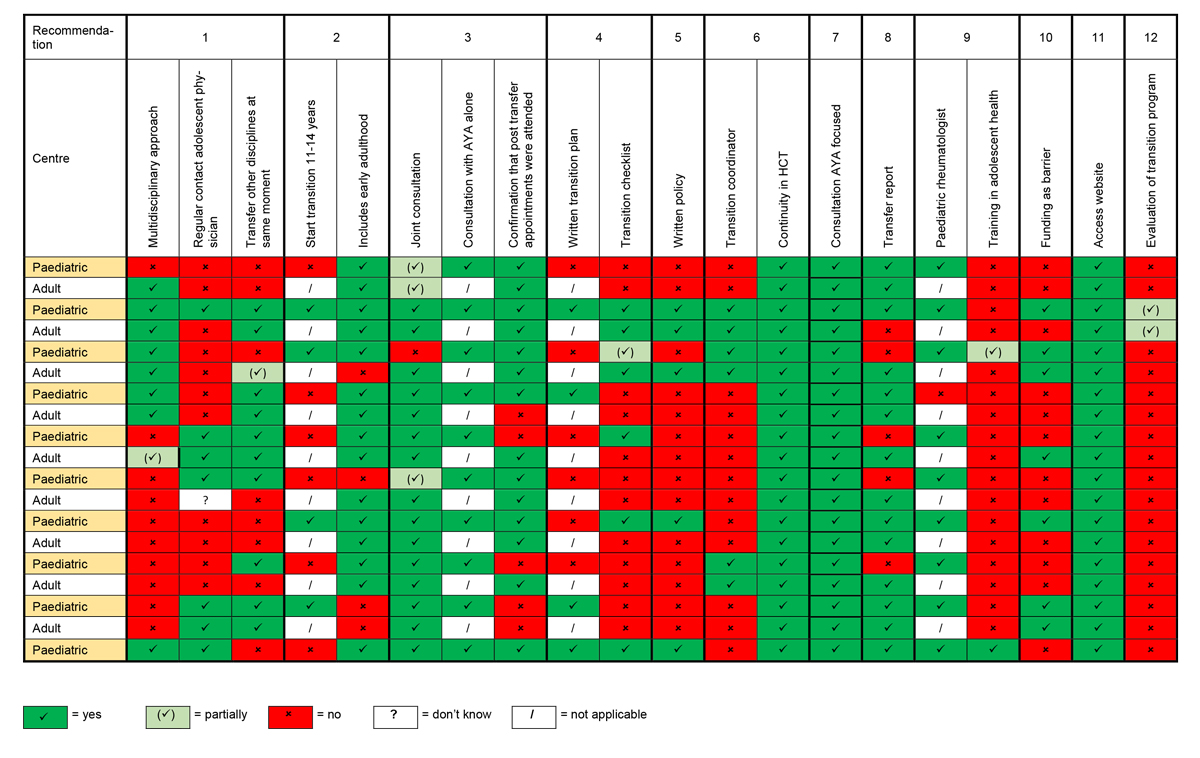

Figure 1 Overview recommendations implemented by centre.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/SMW.2021.w30046

Paediatric rheumatic diseases comprise a heterogeneous group of rare diseases, most often juvenile idiopathic arthritis, systemic vasculitis, and connective tissue and autoinflammatory diseases [1]. Some of these conditions diagnosed during childhood and cared for by a specialised paediatric rheumatology team will resolve before the young people become adults; however, up to half of the patients with paediatric rheumatic diseases will need continuous medical care into adulthood [2]. In Switzerland, an estimated 2500 to 3000 children and adolescents suffer from a rheumatic disease [3]. Consequently, this group of patients will experience a change from a paediatric to an adult healthcare team. This change mostly occurs during adolescence, which is defined as the lifespan between 10 and 19 years of age, and is one of the most challenging periods in a person’s life [4]. Indeed, during adolescence many aspects of a human’s physical, psychological and social condition, as well as their environment will undergo major changes [5]. The chronicity of systemic inflammation from rheumatic diseases represents a risk for significant organic and psychological morbidities and sequelae in adulthood [6]. Consequently, adolescents and young adults (AYAs) suffering from paediatric rheumatic diseases are vulnerable at the time of transfer to adult medicine [5, 7]. If not conducted carefully, the transfer from paediatric to adult healthcare services can have serious repercussions affecting short- and long-term disability, psychosocial development, and educational and vocational achievement, which can have a life-long impact on the patient [8–10]. Specifically, a poorly managed transfer of AYAs is associated with negative outcomes including health deterioration, decreased quality of life, medication non-adherence, missed appointments, loss to follow-up, and increased hospital admissions and emergency room visits [5, 7, 9, 11]. In a lupus cohort study including AYAs, there was a significant increase in the proportion of patients suffering from depression and anxiety after transfer to the adult setting [9]. Furthermore, the majority of the patients (72%) in this cohort study had at least one missed appointment after transition [9]. The increased awareness amongst clinicians of these negative outcomes after a poorly organised transfer has led to the development of transition programmes from paediatric into adult health services. Transitional care (TC) has been defined by the Society for Adolescent Medicine as “the purposeful, planned movement of adolescents and young adults with chronic physical and medical conditions from child-centred to adult-oriented healthcare systems” (12). Current evidence shows that a transition for patients built on an individualised, structured management plan is associated with improved clinical outcomes [13], quality of life [13–15]) and satisfaction with care [15–17], less loss to follow-up [16], and increased illness-related knowledge [14, 15], as well as better parental outcomes [15] such as reduction in behavioural control and increased promotion of independence [14]. However, Clemente and colleagues showed in a systematic review that few transition programmes used evaluation tools and, consequently, comparing effectiveness between the programmes was not possible [18].

In 2017, the European League against Rheumatism (EULAR) and Paediatric Rheumatology European Society (PReS) published recommendations for successful TC in rheumatology [10]. These standards can be used to guide the development of transitional care services and benchmark the quality of transition practice among settings. Using Delphi methodology, the expert panel reached consensus on the following 12 recommendations: (1) high-quality, coordinated, multidisciplinary care; (2) starting in early adolescence; (3) direct communication between key participants; (4) individual transition process and progress; (5) written, agreed and regularly updated transition policies between paediatric and adult settings; (6) written description of multi-professional teams involved in , including a transition coordinator; (7) AYA-focused care that is developmentally appropriate; (8) having a transfer document; (9) appropriate training in generic adolescent care and childhood-onset rheumatic disease; (10) secure funding to offer TC; (11) accessible electronic-based platform for recommendations, standards and resources; and (12) evidence-based knowledge and practice to improve outcomes for AYAs (10). Yet, despite the evidence supporting the importance of a structured transition programme, many, if not most, centres do not completely follow these recommendations. An assessment of the clinical practices of paediatric providers in Europe showed that less than 25% have a written transition policy for their patients, which they adhere to most of time in their centre [5]. For Switzerland, no data are available on the extent to which the EULAR/PReS recommendations are implemented in the care of patients with paediatric rheumatic diseases. The aim of this study was therefore to describe the current provision of TCin Swiss paediatric and adult rheumatology centres, to identify possible barriers to TC in the context of rare rheumatic conditions and to assess healthcare professionals’ self-judgement concerning their performance in TC.

In this cross-sectional study, all 10 paediatric rheumatology centres in Switzerland were invited to participate. Each of these centres routinely collaborates with one adult rheumatology centre, to which they transfer the vast majority of their patients. The paediatric physician named the adult rheumatologist to whom they transfer their AYAs. Those adult centres were also invited to participate. The adult centre is in the same hospital or within short distance of the paediatric centre. The physician in each centre was contacted to participate in the interview. If that individual was not available to participate, another clinician familiar with the practice was identified to participate in the interview.

Between 16 March and 13 June 2020, one rheumatologist from each centre was asked to participate in an interview using a structured manual. In one paediatric centre the nurse also participated in the interview.

To collect data about the transition processes in the centres, a structured interview manual based on the EULAR/PReS recommendations [10] was drafted by one of the co-authors (NS). The draft was reviewed by all members of the core research team (LB, AW, TD, MLD, NS) and revised several times to create the final survey (see appendix).To facilitate the interview and the collection of demographic data about the practice site (e.g., number of patients), the healthcare professional received the interview manual before the interview. Since all participating clinicians were familiar with their practice site, they provided estimates for the number of AYAs in the practice as well as the number in transition. Participants were asked to respond to the survey items in relation to all AYAs in their practice even if not currently in the transition process.

The interviews were conducted by telephone or video call, depending on the preference of the healthcare professional, by a medical doctoral student (NS). The interviews were digitally recorded and free text answers were transcribed.

For data analysis IBM SPSS version 24 [19] was used. Data were analysed using descriptive statistics: frequencies and, where appropriate, the median and range were calculated. Given the small sample size and the distribution of variables, the median and ranges were calculated for all continuous variables. For questions with an "other" answer option, the frequencies of the various responses were counted.

Prior to the interview, the purpose of the study was explained verbally by one of the two last authors (TD and AW). After agreeing to participate, the doctoral student (NS) contacted the identified healthcare professionals by email to schedule the interview. Before starting the interview, the healthcare professionals were asked if they were still willing to participate. Informed consent was implied by participating in the interview. Participants were identified by unique IDs only, names were not recorded on surveys. Data were stored on a password-protected computer. Data from the survey were transferred into an Excel file and doubled check for accuracy. The paper file was then destroyed by shredder.

All 10 paediatric and 9 of 10 adult rheumatology centres participated in this survey. One paediatric centre had to be excluded as the physician had only recently started his clinical activity in this hospital and no AYAs in transition had been followed at the time of interview. All participating rheumatologists are board certified. Most participating paediatric and adult rheumatologists were experienced in TC with a median of 10 years of experience (range 3–40 years). The number of patients currently receiving care in the paediatric rheumatology centres ranged from 50 to 363 (median 140), of whom between 0 and 111 patients in each centre were currently in the process of transition to an adult care setting (median 13). A median of 11 AYAs (range 4–55) had been transferred to adult healthcare services during the prior 2 years in these centres. Adult centres reported that a median of 99% AYAs kept their first appointment (range 82–100%), and 99% (range 77–100%) kept their second appointment. The characteristics of the participating centres are summarised in table 1.

Table 1Basic characteristics of the centres, transitional care practice.

| Paediatric (n = 10) | Adult (n = 9) | ||

| Type of setting, n | University Hospital | 4 | 3 |

| Cantonal hospital | 6 | 4 | |

| Regional hospital | 0 | 1 | |

| Private practice | 0 | 1 | |

| Years working in transitional care, median (range) | 10 (3-40) | Not assessed | |

| Current number of patients, median (range) | 140 (50-363) | Not assessed | |

| Current number of AYAs <18 years, median (range) | 60 (25-160) | 5.5 (0-82)a | |

| Current number of young adults aged 18 to 25 years, median (range) | 9 (0-36) | 30 (10-51)b | |

| Current number of AYAs in process of transition, median (range) | 13 (0-111) | Not assessed | |

| Current number of AYAs who completed transfer to adult healthcare in 2018/2019, median (range) | 11 (4-55) | Not assessed | |

| Having transition coordinator Yes, n | 3 | 3 | |

| Age initiating transition process, number of centres | Early adolescence (11-13 years) | 2 | Not assessed |

| Early to mid-adolescence (11-16 years) | 2 | ||

| Mid adolescence (14-16 years) | 1 | ||

| Mid to late adolescence (14-18 years) | 2 | ||

| Mid adolescence to young adulthood (14-25 years) | 1 | ||

| Late adolescence (17-18 years) | 1 | ||

| Late adolescence to young adulthood (17-25 years) | 1 | ||

| Schedule first appointment in adult practice, number of centres, n | By transition coordinator only | 2 | 3 |

| By paediatric centre only | 3 | 2 | |

| By adult rheumatologist only | 1 | 2 | |

| By patients only | 2 | 1 | |

| By patients (50%) or transition coordinator (50%) | 1 | 0 | |

| By patients (90%) or paediatric centre (10%) | 1 | 0 | |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | |

| Clinician confirmation that AYA attended transition appointments after transfer in adult setting, n | Never | 3 | 1 |

| Rarely | 0 | 1 | |

| Half of the time | 0 | 0 | |

| Often | 1 | 0 | |

| Always | 6 | 7 | |

| Topics often or always discussed /taught during consultations, n (%) | Vocational issues | 9 | 8 |

| Effects of nicotine, caffeine, alcohol on disease/treatment | 10 | 6 | |

| Medication knowledge | 10 | 6 | |

| Effect of illegal substances on disease/treatment | 9 | 4 | |

| Impact of disease/treatment on sexuality, fertility and pregnancy | 8 | 7 | |

| Disease knowledge | 7 | 2 | |

| Booking own appointments | 2 | 3 | |

AYA: adolescent and young adult; a n = 8 (data missing from 2 adult centres); b n= 7 (data missing from 1 adult centre)

The implementation of EULAR/PReS recommendations was heterogeneous across the centres (fig. 1).

Figure 1 Overview recommendations implemented by centre.

Whereas some recommendations (continuity in healthcare team, consultations AYA focused, joint consultations between the paediatric and adult rheumatologists) were implemented in all centres, other recommendations (training in adolescent health, having a transition policy, and evaluation of the transition programme) were implemented in only a few centres. The findings in relation to implementation of the recommendations are summarised below and in fig. 1.

Recommendation 1: AYAs should have access to highly coordinated TC, delivered through partnership with healthcare professionals, AYAs and their families, to address the needs on individual basis. Eight centres (four paediatric and four adult) used a multidisciplinary approach for TC, defined as a minimum of three healthcare professions directly involved in the process. However, in four paediatric and three adult centres, only the physician performed.

When the AYA was also receiving care from another specialist (e.g., cardiologist, dermatologist), six of the paediatric rheumatology centres reported that they often or always checked with the other specialist(s) to see if they were also transferring the AYA to an adult provider. No data were collected in relation to the other specialists’ perception of transition readiness.

Recommendation 2: Transition process should start as early as possible; in early adolescence or directly after the diagnosis in adolescent-onset disease. Nine of 10 paediatric centres did not define a specific age for starting the transition process. One centre reported always starting the transition process at the age of 13 years. In all other centres, the start of transition varied between the ages of 11 and 20. AYA’s adherence to medications and appointments, and disease activity followed by chronological age and the AYA’s wish were rated as the most important factors used to determine initiation of the transition process. Most paediatric centres (n = 9) reported transferring the AYA to the adult centre between 15 and 20 years of age, whereas one centre transfers AYAs between the age of 20 to 25 years. After transfer, all of the adult rheumatologist reported that parents continued to accompany AYAs to their visits, although the proportion varied by centre.

Recommendation 3: Direct contact between key participants. Fifteen centres (seven paediatric and eight adult) always organise a joint consultation with the paediatric rheumatologist, the adult rheumatologist, the AYAs and their parent(s) before transfer of the AYAs. One centre reported transferring patients to a private practice without joint consultation. Separate consultations with the AYA alone take place in all centres.

Recommendation 4: Individual transition processes and progress should be carefully documented in the medical records and planned with AYAs and their families. Six of the ten paediatric centres reported never or rarely having a written transition plan. A transition checklist (a list with themes to be addressed during the transition process in order to ensure that the AYA gains the knowledge and skills to manage their condition) is used in four paediatric and two adult centres.

Recommendation 5: Every rheumatology service must have a written, agreed and regularly updated transition policy. Three paediatric and two adult centres reported having a written policy for TC. Twelve centres (eight paediatric and four adult) reported having a consistent approach; however, they have no official document.

Recommendation 6: There should be a clearly written description of the multi-disciplinary team involved in TC, locally and in the clinical network. This recommendation also states that ideally the team should include a transition coordinator. Six centres (three paediatric and three adult) reported having a designated transition coordinator; however, this individual also had additional job responsibilities. In order to assure continuity of care, AYAs are often or always seen by the same rheumatologist. In the case of an emergency around the transfer time, all paediatric centres designate a contact person. Seven of the adult centres identify a contact person.

Recommendation 7: Transition services must be AYA focused, be developmentally appropriate and address the complexity of AYA development. Whereas in the paediatric setting the effects of nicotine, caffeine and alcohol, and knowledge about their disease were discussed most often, during the adult consultations vocational issues and effects of the disease/treatment on sexuality, fertility and pregnancy where the most common topics discussed (see Table 1). Communication channels used between healthcare professionals and AYAs in all centres included email and phone calls. SMS or WhatsApp was used in six paediatric and in six adult centres. One adult centre used its own centre’s digital application, and one paediatric centre used an existing app.

Recommendation 8: There must be a transfer document. Fourteen (six paediatric and eight adult) centres reported that they always have a transfer report. However, collaborating paediatric/adult centres did not always provide a consistent response in relation to this recommendation, i.e., sending and receiving transfer reports.

Recommendation 9: Healthcare teams involved in transition and AYA care must have appropriate training in generic adolescent health and childhood-onset rheumatic disease. One paediatric rheumatologist reported having specific training in TC. The participating nurse reported attending a 1-week course in adolescent health.

Recommendation 10: There must be secure funding for dedicated resources to provide uninterrupted clinical care and transition services for AYAs entering adult care. Two paediatric and six adult rheumatologists did not identify funding as an important barrier to implementing a transition process. Healthcare professionals are reimbursed by either the hospital or the healthcare insurance. Issues related to reimbursement mentioned by a majority of the centres were that nurses currently cannot bill for their work and during joint consultations only one physician can bill for the visit.

Recommendation 11: There must be a freely accessible electronic-based platform to host the recommendations, standards and resources for TC. All centres have access to the EULAR as well as to the PReS website. No further information was assessed concerning this recommendation.

Recommendation 12: Increased evidence-based knowledge and practice is needed to improve outcomes for AYA with childhood-onset rheumatic diseases. None of the centres formally evaluated their transition practice. Twelve centres (nine paediatric and three adult) reported contributing to the evidence base of childhood-onset rheumatic diseases by entering patient data into a registry. Centres most often reported recording data in the Juvenile Inflammatory Rheumatism (JIR) network’s JIRCohort platform.

We asked the participating healthcare professionals to rate themselves on their performance regarding TC in general, their communication with the AYA, success in achieving AYAs independence in taking medication, success in achieving AYAs adherence to appointments and success in achieving AYAs knowledge about their disease. Nine paediatric (one missing) and seven adult healthcare professionals (two missing) responded to the first two items, whereas the last three items were answered by eight paediatric (two missing) and seven adult healthcare professionals (two missing). Overall, paediatric healthcare professionals rated themselves better compared with their adult colleagues. For their TC performance in general, eight of the paediatric and six of the adult clinicians rated themselves as good to excellent. For all other statements, all the paediatric clinicians rated their performance as good to excellent, whereas five adult clinicians reported success in achieving independence in medication taking and AYA knowledge about their disease, andsix for communication with patients and success in achieving adherence to appointments.

All participants responded to the questions about barriers. Overall, the paediatric centres reported more barriers to the implementation of a transition policy than the adult centres. Shortage of staff was the most important barrier identified by the paediatric clinicians (70% vs 22.2% for the adult clinicians), followed by lack of time (50% vs 11.1%), and funding difficulties (paediatric centres 50%, adult centres 33.3%) The availability of rooms for the consultations was reported as a fairly to very important barrier by 30% of the paediatric and 22.2% of the adult clinicians. The shortage of adult rheumatologists was a very important barrier for one paediatric centre. Another paediatric centre identified their small size as a barrier to implementing a transition programme. The distance to the paediatric centre, especially the limited public transportation available, was reported as a barrier by an adult centre.

Some centres reported ambivalence of patients about the moment of transfer. Other issues were loss of follow-up, especially in patients not taking systemic medications; parents rather than the AYA taking the lead during the consultation; and missed TC consultations.

This study describes the current practice of in Swiss paediatric and adult rheumatology centres vis-a-vis EULAR/PReS recommendations. All participating centres followed parts of the EULAR/PReS recommendations in their clinical practice. Yet none of the centres implemented all recommendations. This varied not only across the paediatric and adult healthcare settings, but also between the local collaborating paediatric and adult centres. The recommendations with the largest discrepancy between the centres were the presence of a multi-disciplinary approach, starting age for TC (paediatric centres only) and having a transition plan. Despite these findings, most centres rated their performance as very good. We did not identify any pattern in this heterogeneity based on language region, centre size or location.

Understanding the unique needs of AYAs is critical to ensure a smooth transition from paediatric to adult care. A UK-wide survey questioning 613 adult trainees from 23 adult specialities reported that the most significant barriers to provide good care to AYAs was the lack of knowledge about how to deal with AYAs issues [20]. The training gap in adolescent health exists for both paediatric and adult healthcare professionals [21]. In Switzerland, no focused postgraduate education is available for adolescent medicine. Most medical and nursing education programmes have limited content about adolescent health, resulting in a knowledge deficit about this vulnerable patient population. Some countries, such as France, offer a 2-year training programme in adolescent medicine for healthcare professionals [22]. There is currently only one short programme offered on an ongoing basis in Switzerland, EuTEACH (European training in effective adolescent care and health) as a yearly 1-week summer school in Lausanne, Switzerland [23]. Only one of the physicians and the transition nurse included in our study reported having attended this course. Education about transition is even more limited. In the above-mentioned UK survey, three out of four participants rated their training in transition as minimal or nonexistent [20]. This lack of specific knowledge of transitional care may be the reason why transfer as the act of handing over the AYA to the adult healthcare professional was confused with the term transition by some healthcare professionals. However, lack of training does not necessarily mean that the follow-up is less young person-oriented, as most of the units have small teams with close personal patient contact enabling them to know their patients and their needs.

Colver and colleagues assessed the implementation of a number of TC service features that are expected to improve outcomes in an UK longitudinal cohort study of AYAs with type 1 diabetes, cerebral palsy or autism spectrum disorders with an associated health problem [24, 25]. Overall 40% of the participants in Colver’s study reported meeting with the adult team before transfer. By definition this could have been a joint appointment or just meeting with the adult clinician. In our study we specifically assessed whether the centres offered joint consultations with both the paediatric and adult rheumatologist participating; 15 of the 19 centres always offer joint consultations. Our findings were similar to those of Colver et al. [24, 25] in relation to the availability of a transition plan (70% and 60%, respectively) and having a key worker / coordinator available in only few centres in both studies.

Although it is recommended that initiation of starts at early adolescence (between 11 and 13 years of age), only two centres reported starting in this age group, and two centres had a larger age range of early adolescence to mid adolescence (between 11 and 16 years of age). All other centres started when the AYA was 14 years or older. A study by McDonagh et al. [15], which evaluated a coordinated evidence-based programme, showed the importance of initiating the process in early adolescence. Twelve months after implementing the programme, the youngest group (age 11 years) showed greater improvements in arthritis-related knowledge, increase in self-medicating and improved satisfaction with rheumatology care [15].

The absence of a written policy in 80% of the participating centres might lead to loss of consistency between individual TC pathways. This in turn might result in confusion for the patients and their families and reduced quality indicators (e.g., quality of life, patient satisfaction with care) for a successful transition of AYAs. The results of our survey are in accordance with the results of a European survey assessing current clinical practice and resources in paediatric rheumatology across Europe, with an only 20% prevalence of having a written policy for TC [5]. The EULAR/PReS only list recommendations; there is no template. The availability of a template that can be used to develop a transition policy and transfer document would be helpful to clinicians.

As is the case with many paediatric rare diseases in Switzerland, the small patient number in some centres may be a limiting factor for building up established structures for TC. The small size of some clinics and pressure on the limited resources is compounded by the fact that clinical TC activities are not reimbursed in Switzerland, making it unrealistic for them to have the time to develop a tansition policy.

In recent years, there has been increasing pressure to reduce the time for patient consultation appointments; this has resulted in a lack of time for focused activities, including preparing young people for their transition and consequently, imposing a substantial barrier for state-of-the-art TC in rare paediatric diseases. When we consider these various aspects, it is not surprising that ambulatory hospital departments do not focus on establishing TC in most of the Swiss centres. In this context, the heterogeneity of our results also question the applicability of the EULAR/PReS recommendations to Swiss rheumatology centres. Indeed, Foster et al. [10] recognised differences between healthcare systems that result in the need for recommendations to be reviewed for applicability in different settings.

Although the EULAR/PReS recommendations are widely accepted, they are based on expert opinions and may not be valid in every country. A group of 27 paediatric and adult rheumatologists reviewed the EULAR/PReS recommendations for their applicability in the Italian healthcare setting [26]. Using Delphi methodology, they reached the consensus threshold for only 4 of the 12 recommendations. According to Ravelli and colleagues [26], the reasons for the poor agreement with the EULAR/PReS recommendations are the paucity of Italian centres with both a paediatric and an adult rheumatologist on site, disagreement about the optimal age to start TC, different definitions for the role of transition coordinator, diversity between paediatric and adult assessments, and lack of financial and administrative support. With the goal of implementation of nation-wide TC practice for AYAs in Italy, the rheumatologists formulated 25 additional country-specific statements. These statements mainly focused on a number of practical issues that need to be addressed. First of all, Ravelli and colleagues state they had to identify which centres were willing to implement a TC practice and to improve the knowledge and skills about TC of the healthcare professional [26]. The results of this study highlight the importance of evaluating the recommendations for country-specific suitability.

The existence of a structured evaluation of the local transition programme was the least frequently reported recommendation by centres in our study. The EULAR/PReS recommend that centres measure outcomes of the TC practice, but they do not specify what the outcomes should be. We identified two studies that used Delphi methodology to determine which outcomes should be measured to evaluate the success of transition programmes [27, 28]. In the study of Suris and Akre [27], one indicator (patient not lost to follow-up) was rated as essential by all 37 experts. Seven indicators were rated as very important or essential by the experts: attending scheduled visits in adult care, building a trusting relationship with the adult provider, continuing attention to self-management, the patient’s first visit in adult care no later than 3–6 months after transfer, the number of emergency room visits for regular care in the past year, patient and family satisfaction with care, and maintaining/improving standard for disease control evaluation. Ninety-three experts identified 10 outcome indicators in the study of Fair et al. (2016) [28], where quality of care was rated as the most important outcome followed by self-management of the condition, understanding of the characteristics of the condition and complications, knowledge of medications, adherence to medications and/or treatment, attending medical appointments, having a medical home, avoiding unnecessary hospitalisations, understanding health insurance, and having a social network. McDonagh [29] points out that “existing outcome measures still fail to reflect all aspects of TC: biological (disease), psychological, social and educational/vocational.”

A main strength of this study is that all paediatric rheumatology centres participated. There are a number of limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. One potential limitation of this study is the data collection procedure. Because of the restrictions concerning SARS-CoV-2 in March 2020 we were not able to collect data by observation or to conduct face-to-face interviews. Nevertheless, we were able to conduct all interviews within 4 months. Although the clinicians participating in this study were selected because of their familiarity with the centre, it is possible that the numbers provided (e.g., number of patients currently in and number transferred in the past 2 years) where over- or underestimates. As data were not collected anonymously, there is a possibility of social desirability bias. It is also likely that the paediatric and adult clinicians were evaluating success from their perspective and probably not the entire process. We did not assess the years adult rheumatologist work in or the number of AYAs still in transition in the adult site. Finally, the current process was only assessed from the perspective of the healthcare professional. A next step will be the assessment of the AYAs and their parent’s perception of the current practice, as well as collection of suggestions to improve TC. Furthermore, patient-reported outcomes (e.g., quality of life, satisfaction with care) as well as disease related outcomes (e.g., disease activity) and their relationship to the implementation of the recommendations will be examined. The results of the studies examining these relationships will determine the need for future intervention studies to improve transitional care in Swiss rheumatology centres.

Recently, the Swiss healthcare system has set a political focus on patients with rare diseases across all ages. In the following structured process, clinical specialists for rare diseases may have the opportunity to formulate procedures that improve quality of .

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

1. Oen K , Malleson PN , Cabral DA , Rosenberg AM , Petty RE , Cheang M . Disease course and outcome of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis in a multicenter cohort. J Rheumatol. 2002 Sep;29(9):1989–99.

2. Conti F , Pontikaki I , D’Andrea M , Ravelli A , De Benedetti F . Patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis become adults: the role of transitional care. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018 Nov-Dec;36(6):1086–94.

3. Roethlisberger S , Jeanneret C , Saurenmann T , Cannizzaro E , Bolt I , Sauvain MJ , et al. Pediatric Rheumatology in Switzerland. Paediatrica. 2015;26(2):22.

4. World Health Organisation . Adolescent Health https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health/#tab=tab_1 [cited 2020, July 27].

5. Clemente D , Leon L , Foster H , Carmona L , Minden K . Transitional care for rheumatic conditions in Europe: current clinical practice and available resources. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2017;15(1):49. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-017-0179-8. PubMed PMID: 28599656; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5466791.

6. Hersh A , von Scheven E , Yelin E . Adult outcomes of childhood-onset rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7(5):290-5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2011.38. PubMed PMID: 21487383; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3705738.

7. Ardoin SP . Transitions in Rheumatic Disease: Pediatric to Adult Care. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2018 Aug;65(4):867–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2018.04.007

8. Hilderson D , Westhovens R , Wouters C , Van der Elst K , Goossens E , Moons P . Rationale, design and baseline data of a mixed methods study examining the clinical impact of a brief transition programme for young people with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: the DON'T RETARD project. BMJ Open. 2013;3(12):e003591. Epub 2013/12/05. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003591. PubMed PMID: 24302502; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3856617.

9. Son MB , Sergeyenko Y , Guan H , Costenbader KH . Disease activity and transition outcomes in a childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus cohort. Lupus. 2016;25(13):1431-9. Epub 2016/03/26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203316640913. PubMed PMID: 27013665; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5035166.

10. Foster HE , Minden K , Clemente D , Leon L , McDonagh JE , Kamphuis S , et al. EULAR/PReS standards and recommendations for the transitional care of young people with juvenile-onset rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Apr;76(4):639–46. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210112

11. Varty M , Popejoy LL . A Systematic Review of Transition Readiness in Youth with Chronic Disease. West J Nurs Res. 2020;42(7):554-66. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945919875470. PubMed PMID: 31530231; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7078024.

12. Blum RW , Garell D , Hodgman CH , Jorissen TW , Okinow NA , Orr DP , et al. Transition from child-centered to adult health-care systems for adolescents with chronic conditions. A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 1993 Nov;14(7):570–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/1054-139x(93)90143-d https://doi.org/10.1016/1054-139X(93)90143-D

13. Liang L , Pan Y , Wu D , Pang Y , Xie Y , Fang H . Effects of Multidisciplinary Team-Based Nurse-led Transitional Care on Clinical Outcomes and Quality of Life in Patients With Ankylosing Spondylitis. Asian Nurs Res. 2019 May;13(2):107–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2019.02.004

14. Hilderson D , Moons P , Van der Elst K , Luyckx K , Wouters C , Westhovens R . The clinical impact of a brief transition programme for young people with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results of the DON’T RETARD project. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016 Jan;55(1):133–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kev284

15. McDonagh JE , Southwood TR , Shaw KL ; British Society of Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology . The impact of a coordinated transitional care programme on adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007 Jan;46(1):161–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kel198

16. Walter M , Kamphuis S , van Pelt P , de Vroed A , Hazes JMW . Successful implementation of a clinical transition pathway for adolescents with juvenile-onset rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2018;16(1):50. Epub 2018/08/05. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-018-0268-3. PubMed PMID: 30075795; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6091100.

17. Shaw KL , Southwood TR , McDonagh JE ; British Society of Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology . Young people’s satisfaction of transitional care in adolescent rheumatology in the UK. Child Care Health Dev. 2007 Jul;33(4):368–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00698.x

18. Clemente D , Leon L , Foster H , Minden K , Carmona L . Systematic review and critical appraisal of transitional care programmes in rheumatology. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016 Dec;46(3):372–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.06.003

19. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows . Version 24.0 [Internet]. Released 2016.

20. Wright RJ , Howard EJ , Newbery N , Gleeson H . 'Training gap' - the present state of higher specialty training in adolescent and young adult health in medical specialties in the UK. Future Healthc J. 2017;4(2):80-95. Epub 2017/06/01. doi: https://doi.org/10.7861/futurehosp.4-2-80. PubMed PMID: 31098440; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6502624.

21. Michaud PA , Jansen D , Schrier L , Vervoort J , Visser A , Dembinski L . An exploratory survey on the state of training in adolescent medicine and health in 36 European countries. Eur J Pediatr. 2019;178(10):1559-65. Epub 2019/08/30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-019-03445-1. PubMed PMID: 31463767; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6733827.

22. Société Française de Pédiatrie . [cited 2020 November 4]. Available from: https://www.sfpediatrie.com/formation-enseignement/diu-medecine-et-sante-de-ladolescent

23. European Training in Effective Adolescent Care and Health (EuTEACH) . Lausanne, Switzerland [cited 2020 November 4]. Available from: https://www.unil.ch/euteach/en/home.html

24. Colver A , McConachie H , Le Couteur A , Dovey-Pearce G , Mann KD , McDonagh JE , et al. A longitudinal, observational study of the features of transitional healthcare associated with better outcomes for young people with long-term conditions. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):111. Epub 2018/07/24. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1102-y. PubMed PMID: 30032726; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6055340.

25. Colver A , Pearse R , Watson RM , Fay M , Rapley T , Mann KD , et al. How well do services for young people with long term conditions deliver features proposed to improve transition? BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):337. Epub 2018/05/10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3168-9. PubMed PMID: 29739396; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5941647.

26. Ravelli A , Sinigaglia L , Cimaz R , Alessio M , Breda L , Cattalini M , et al.; Italian Paediatric Rheumatology Study Group and the Italian Society of Rheumatology . Transitional care of young people with juvenile idiopathic arthritis in Italy: results of a Delphi consensus survey. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019 Nov-Dec;37(6):1084–91.

27. Suris JC , Akre C . Key elements for, and indicators of, a successful transition: an international Delphi study. J Adolesc Health. 2015 Jun;56(6):612–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.02.007

28. Fair C , Cuttance J , Sharma N , Maslow G , Wiener L , Betz C , et al. International and Interdisciplinary Identification of Health Care Transition Outcomes. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(3):205-11. Epub 2015/12/01. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3168. PubMed PMID: 26619178; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6345570.

29. McDonagh JE , Farre A . Are we there yet? An update on transitional care in rheumatology. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20(1):5. Epub 2018/01/13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-017-1502-y. PubMed PMID: 29325599; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5765652.

The questionnaire is available in the pdf version of this article.