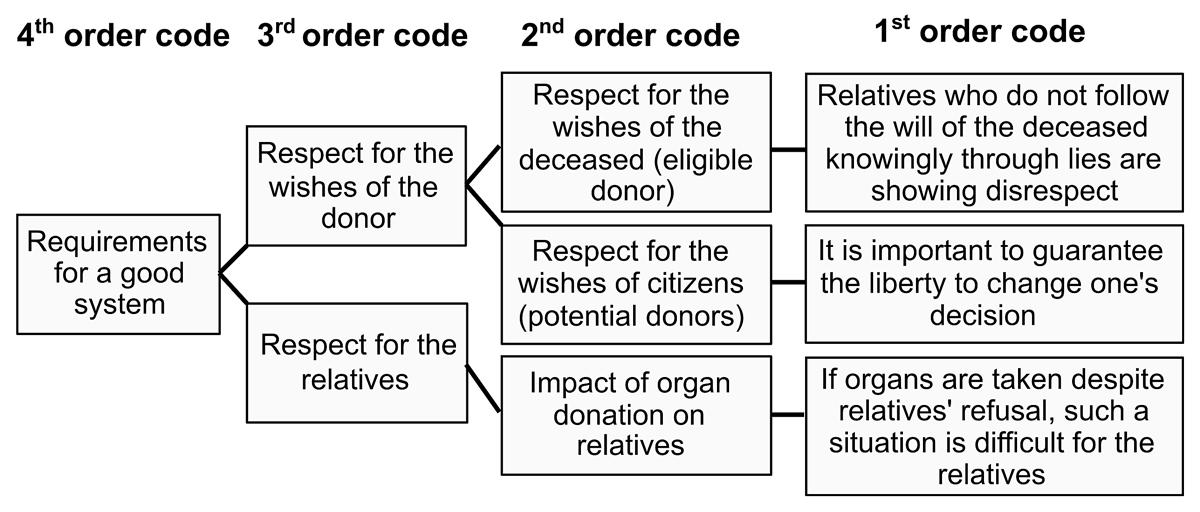

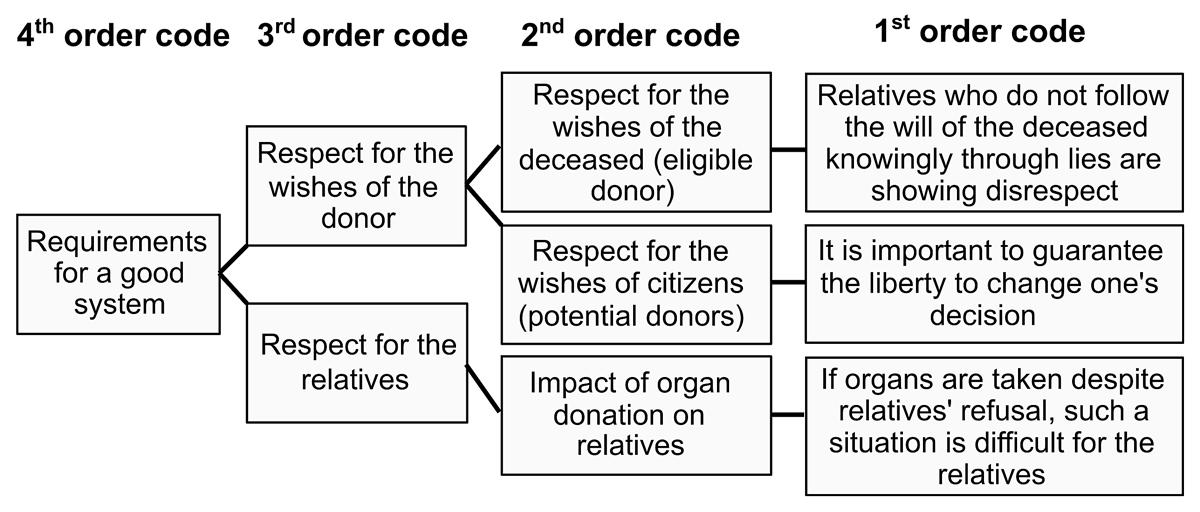

Figure 1 Examples of code hierarchy.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/SMW.2021.w30037

The current legal framework in Switzerland for organ donation is the explicit consent (opt-in) model: in theory, deceased citizens are non-donor unless they have expressed (verbally or in a written document) the wish to donate their organs [1]. In practice, the medical team makes contact with the relatives of the deceased persons in order to find out their presumed will; the relatives make the final decision. Unfortunately, the will of the deceased is often unknown: although 91% of Swiss citizens are favourably disposed towards organ donation, only 25% have clearly expressed their wishes during their lifetime on a donor-card or in their advance directives [2]. This absence of a will seems to deter relatives from agreeing to the donation: they refuse more than half of the requests [3, 4]. In international comparison, Switzerland ranks very low on organ donation, with 18.4 deceased donors per million inhabitants in 2019, compared with 49.6 in Spain, 30.3 in Belgium and 33.3 in France [5]. Every 4 days in Switzerland, a patient dies while on the organ donation waiting list [3].

In the hope of increasing the donation rate, and in reaction to the input of a citizens' initiative [6], the Swiss parliament has made a proposal for a soft presumed consent (opt-out) policy according to which citizens are presumed organ donors unless they have expressed their refusal (verbally or in a written document) during their lifetime. As in the opt-in system, the medical team makes contact with the relatives in order to find out the deceased’s presumed wishes: the relatives make the final decision.

This soft opt-out policy change was accepted by both chambers at the national level. However, it is likely to be challenged by a referendum which will give rise to a public vote. The opt-out policy does not meet with unanimous approval. One major concern is its efficacy [7, 8], because in the end, the relatives’ opinion remains the decisive decision factor. In contrast, a “hard” opt-out system, in which the views of the deceased’s relatives are not actively sought, may be more efficient, but it would also be more socially and ethically controversial. Both soft and hard opt-out systems have been rejected by the National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics [9] and the Catholic advisory board “Conférence des Évêques Suisses” [10]. These committees support the opt-in system combined with a legislative addendum: the “mandated choice” [11]. Such a policy would make it mandatory for citizens, by way of some administrative procedure, to make a choice during their lifetime between three options: registering as a donor, registering as non-donor, or deferring their decision. Note that the mandated choice can be combined with the opt-in or opt-out solutions, which then apply to eligible donors who have not expressed their choice during their lifetime.

Facing this complex web of legislative options, public and political debates promise to be complex and possibly confusing. Since citizens may have the final word in the Swiss democratic setting, it is important to identify the considerations and factors that are the most relevant to them when they evaluate the proposed policies. A public debate of quality should address the reasons that are of concern to the public, even if those reasons are debatable or unfounded (which is often due to biased or lack of information). This is why we aimed at exploring, with qualitative interviews, how ordinary citizens perceive these different organ donation policies and what are their fears or hopes regarding these options.

We conducted semi-structured taped interviews with ordinary French-speaking Swiss citizens socially integrated in the Geneva region. We made this choice of region and language for practical reasons: interviews were conducted by JK, a French speaking master student at Geneva University, during a time period devoted to her master thesis.

In order to obtain a variety of points of view, we planned to recruit citizens of various ages, gender, levels of education, with or without children, holding different political views, religious beliefs, having or not a personal experience with organ donation, and holding opposite opinions on organ donation.

We approached participants in public spaces and made an appointment with them in a quiet place. We reviewed the information sheet together, answered all questions and asked them to sign a consent form. We conducted taped interviews using a semi-structured interview grid (appendix 2) designed to elicit participants’ views on organ donation policies that could plausibly be implemented in Switzerland: the currently explicit consent system (opt-in), the presumed consent system (opt-out) in its soft and hard versions, and the “mandated choice” legislative addendum. To protect participants’ confidentiality, we did not ask them to identify themselves (they signed anonymous consent forms) and we deleted the recordings after transcription. The study protocol was approved by the Commission universitaire d’éthique de la recherche (decision CUREG.201908.07).

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis. In a first round of coding, transcripts were examined and single meaning elements were labelled with content codes. In the second stage, we assembled the initial codes into categories of second order codes and reiterated the process up to the fourth level when only three core codes remained (full table of codes in appendix 1 and example in figure 1). Some elements called for multiple codes. JK coded the whole dataset; 15% of the transcripts were double-coded by the co-supervisors (CC and SH). In regular meetings involving all authors, we compared and reviewed the coding and the resulting set of codes to ensure that concepts were clearly defined, appropriately derived from the data, and that codes were being used consistently. Throughout the analysis, we regularly checked the coherence between higher-level codes and the subsumed transcript elements. When necessary, we relabelled, fused or reallocated codes. We ended the recruitment when we reached data saturation, that is, when no new code emerged from the analysis, indicating that we would not obtain much more information with more participants.

Figure 1 Examples of code hierarchy.

Between October 2019 and March 2020, JK recruited and interviewed 15 citizens, a well-balanced sample in terms of socio-demographic characteristics (see table 1). However, it happened that none of our participants was opposed to organ donation. Because of time constraints due to the COVID-19 outbreak, and since we did not want to recruit a convenience sample, we gave up on that criterion. Interviews lasted between 20 and 60 minutes. We reached data saturation in our analysis at the 15th participant, and ended the recruitment at that stage. The following sections describe the main results of our analysis. Numbers of occurrences should be understood to indicate salience within the dataset rather than representative frequency.

Table 1Participant characteristics.

| Characteristics | Participants |

| Age (median / range) | 38 / 18–79 |

| Gender (nb) | |

| – Women | 8 |

| – Men | 7 |

| Level of education (nb) | |

| – High school | 1 |

| – Professional school | 4 |

| – Bachelor | 4 |

| – Master | 6 |

| Children (nb) | |

| – With | 7 |

| – Without | 8 |

| Political views (nb) | |

| – Right-wing | 6 |

| – Centre | 4 |

| – Left-wing | 4 |

| Religious beliefs (nb) | |

| – Catholic | 4 |

| – Protestant | 2 |

| – Jew | 1 |

| – Non-believer | 8 |

| Personal experience with organ donation (nb) | |

| – Yes | 5 |

| – No | 10 |

The first of three broad topics addressed by participants included all sorts of values, conditions, information and procedures that they considered as important for designing an acceptable and sustainable policy regulating organ donation. By far the most frequently mentioned issues referred to the notion of respect: first, respect for the deceased person’s wishes during their lifetime, and second, respect for the point of view of the grieving relatives. In addition, participants pointed out the importance of other moral values and optimisation criteria. Finally, they made their own proposals.

Most participants (n participants = 7; n occurrences = 31) explicitly stated that a good legislative system needs to respect donors’ wishes. Citizens should be able to express their wish during their lifetime and this wish should be followed. Some participants stated further that the deceased wish should be fulfilled even if it contradicts the relatives’ opinion.

“I think that [if I knew that this was his decision] I would be sure that I have respected his will, and this would be a way to honour him (...) but I would feel bad (...) guilty if I decided against his choice.” (Participant 1)

More fundamentally, what seemed important to many participants was citizens' liberty to decide (n participants = 7; n occurrences = 12). Some mentioned the importance of being allowed to change one's decision, and others mentioned that we should have the right not to express a choice on the matter.

All participants found it particularly relevant to discuss the extent to which relatives need to be respected (n participants = 15; n occurrences = 96). Compared with the respect for wishes of the deceased, which was unanimously evaluated as important to follow, we found more nuanced views related to relatives. Some participants highlighted the importance of considering the relatives’ view whereas others feared the risk that relatives have too much power and may decide against the deceased's wishes.

“Now, about the consent of the family, I think that it is pretty good, because they are the survivors, and they have to be comfortable with that too” (Participant 6)

“The positive side (...) [of this policy] is precisely that we ask to the relatives what was the point of view of the deceased and that is really good, well, now the relatives, the problem with the relatives (...) if the relatives did not share the deceased views or other, they may lie” (Participant 1)

Thus, it seems that relatives’ view needs to be respected primarily in virtue of the fact that they are the best informants about the deceased's wishes. Participants’ worries about the risk of misinterpretation or lying makes it clear that relatives’ power of decision should not override that of the deceased. In addition, some participants mentioned that a good system should alleviate the suffering of the grieving relatives when they have to make decisions, which are particularly difficult to make when the deceased have not expressed a clear opinion during their lifetime. These participants considered that a legislative system that encourages citizens to express their wishes would relieve the family and the medical team.

Participants made additional moral statements while assessing the different organ donation policies. One recurrent pattern of thought (n participants = 10; n occurrences = 21) was that it is a great good to dispose of more organs, and therefore, an organ donation policy should actively promote donation. Thus, organ donation should be a topic of discussion and become a social norm. Some participants, however, imposed limits to the promotion of organ donation: physicians should make sure not to abuse of their role as authority figure; it should be possible to keep our decision over organ donation confidential; it is important to actively search for the deceased’s will; if there is a transition from one policy to another, it should be enforced smoothly, etc.

Many participants (n participants = 8; n occurrences = 18) pointed out that in order to avoid organ loss, it is important to optimise the administrative procedures. Some stated that a good system should not be administratively burdensome as is the case with the current opt-in system, which requires one to actively express one’s wishes on the national register.

“In my view, either we have a strong conviction which motivates us to initiate this procedure [i.e. to express one’s wish on the organ donation register] or, because we forget, or because we have not been exposed to a situation of this sort, we do not necessarily initiate the procedure.” (Participant 2)

Other pointed out that in the Swiss opt-in system, it is a good idea to systematically ask relatives’ opinion because they may accept donation even though the deceased has not expressed her or his wishes. Other participants expressed the idea that the mandated choice system is an effective administrative procedure since all that is left to do is to follow the deceased's explicit directives. Participants also stated that effectiveness should not come at the cost of respect of individuals’ choices: thus, administrative procedures should remain flexible and allow people to take time to think over it and to easily change their view.

“The decision would be better reflected if the person had more time (...) That would allow the person to say ‘I don't know, I wait for the next year or two’ (...) In the meantime, what happened, maybe I changed my mind or maybe now I'm ready to say no. And that may allow us to make decisions that better meet the person's consent in the event of her death.” (Participant 7)

In a proactive mood, participants made a variety of suggestions (n occurrences=18): we could take inspiration on other countries, we could seek the opinion (and experience) of grieving families that have a story of organ donation, we could ask the question of organ donation every 5 years at the national level, we could advise primary care physicians to add the question to the routine annual check-up, we could make children express their opinion, etc. Several participants favoured even more extreme forms of organ legislation: make organ donation a mandate, or enforce a hard opt-out system in which relatives are not consulted.

The second broad topic of discussion is a counterpart to the previous one. Participants expressed a series of concerns that provide reasons to doubt the adequacy of given organ donation policies: they were mostly concerned with the risk of failing to respect the deceased wishes, of being too intrusive, of failing to motivate citizens to express their preferences, of failing to provide needed organs. Interestingly, some of these concerns cut across all different policies that were evaluated. By the end of the interviews, many participants recognised that no system is perfect and were in doubt about which one should be promoted.

Most participants (n participants = 13; n occurrences = 25) expressed their concern that the deceased's wishes may not be fulfilled or respected. This can happen if the relatives have no idea about the deceased's preferences and finally make a decision that does not match what she or he would have expressed while alive. For instance, when criticising the opt-in system, on participant noted:

“I think there would be more ‘no’ than ‘yes’ even if the person wanted [to give his organs], and you don’t really know if the person wanted or not, maybe you say no to respect this person.” (Participant 5)

Similarly, when criticising the opt-out system, another participant noted:

“Well there is another negative point, negative I don’t know but again if there is no real obligation [to register], this means that if we do nothing we are donors, but maybe there are people that are not willing to give their organs, but they won’t go register by themselves as non-donors.” (Participant 13)

Similarly, when criticising the mandated choice option, a participant noted that those who answer “no” to the question, “do you agree to be an organ donor?” may do so because they have not yet made a decision on the matter rather than because they are against donating:

“For me it's logical that the person should say no, while waiting to form their opinion (...) If the person suddenly dies, for example, then her answer is interpreted as ‘I don't want to be an organ donor’, although it is not necessarily the case.” (Participant 2)

Some participants feared that if relatives have too much decision power, they may be tempted to deceive and refuse donation despite knowing that the deceased wanted to be a donor.

“Absolutely, because easily, I am for example against organ donation, and one of my relatives says he wants to give his organs. Ok I hear you, we have a discussion and we agree to nothing. This relative dies and the doctor comes to me to ask. Easily I could say ‘no, don’t take his organs’ because it is my position, and not that of my relative.” (Participant 15)

Some participants also highlighted the possibility that too constraining policies may endanger (or be considered as endangering) citizens' rights and liberties (n occurrences = 18). For instance, some participants pointed out that the mandated choice policy may be considered as intrusive, even if it is an efficient policy in other respects: some people may not want to decide or have to think about it. Some participants also evaluated the strong opt-out policy as possibly too restrictive from the relatives’ point of view.

“If the doctors do not have the deceased's view and tell the family that they will take the organs, I think that this way of proceeding is too direct. We should still ask the family. Do you accept that we take the organs?” (Part icipant14)

Even the soft opt-out policy generated occasional concerns. One participant, for instance, feared that relatives’ right to be consulted will be less respected under that system:

“I don't know, I try to put myself in the mind of the person who is in shock. (...) I know and I'm sure that it [the discussion about taking the organs] takes place in conditions of respect for the person who is confronted to the situation, and respect for the family, but with a law like that [opt-out system], my fear would be that yes, we will ask, but we will act quickly.” (Participant 8)

Participants showed a great interest in promoting organ donation. They provided many arguments in favour of it (n participants = 11; n occurrences = 30) : it saves lives, gives organs a second life, etc. They tried to identify what would contribute to promoting organ donation. Based on the assumption that organ donation should be promoted, they evaluated the different policies. From this point of view, many participants recognised the limits of the existing opt-in system; when relatives are predominantly integrated in the decision process, there is the risk that they end up refusing donation. In contrast, many participants considered the opt-out system as an interesting way to facilitate donation (n participants = 9; n occurrences = 16). Alleviating the burden of expressing a view makes it easier for relatives to accept donation: if the deceased has not registered as a non-donor, it is a good sign that he or she was not fundamentally against donation.

“[The soft opt-out system] has a small added value, a slightly more positive aspect, it can lead, when we are in doubt [about the deceased position], (...) even without discussion, to say that if he did not take the administrative step, then he agreed [to donate]. When in doubt we [the family] say yes.” (Participant 2)

Some participants mentioned that we need a system that promotes the expression of people’s wishes during their lifetime. From this point of view, the mandated choice was considered as a good option: increasing knowledge about people’s wishes helps to speed up the organ donation procedures when death occurs and increases relatives’ acceptance of the donation.

Most participants discussed the difficulty of promoting decision-making (n participants = 10; n occurrences = 77) . Many mentioned that not enough citizens express their preferences regarding organ donation, either in writing or orally (n occurrences = 7). In light of this statement, the current opt-in system was judged as insufficient (n occurrences = 8). Some participants pointed out that citizens may not be adequately informed about the existing organ shortage, about what it means to wait on a list in the daily expectation of receiving an organ. Participants expressed the need for more awareness-raising measures. They actively explored what factors might help to promote open discussions and explicit decision-making. Some expressed the view that the opt-out system and the mandated choice system may motivate or even force people to think over their preferences. Some went so far as to state that in order to promote decision-making, the mandated choice system should not allow postponing one's decision (by allowing for a response of the sort “I will think about it and will respond at a later time”). Interestingly, however, many factors mentioned as decision-making enhancers were not linked to the choice of a particular legal system: choice about organ donation should become a matter of culture and education, shared personal experiences of organ shortage (either as a patient or as a healthcare professional) may impact on decision-making, the national register facilitates decision-making because it allows for recording ones’ choice in complete confidentiality.

“He may want to donate but not feel at ease to mention it within his family. It [the national register] would allow these individuals to express their wish nevertheless and make it clear enough. Thereafter, the family is freed a little bit from the choice to make [on behalf of the deceased loved one].” (Participant 10)

Most participants expressed their uncertainty about which is the most appropriate system, how to choose between them, and how to address some difficulties that cut across all systems (n participants = 11; n occurrences = 31). Some wondered whether the reason for the shortage of organs lies in relatives’ refusal. Other wondered whether a possible short-term positive effect may be obtained thanks to public discussions about the vote, but that effect may not last in the long run.

Participants often highlighted the fact that whatever system is enforced, one or another difficulty will remain. This is due to the fact that the road from death to transplantation is long and complex. It is also due to the lack of discussions within families, which should be stimulated with relevant public information. Moreover, participants also highlighted the fact that there is such a diversity of circumstances related to organ donation that no system seems optimal for all situations.

“Well, it’s true that these issues are very difficult. In fact, I think that we will never reach a perfect system. In fact, we will approach but never reach an optimal. I think that we simply have to accept it.” (Participant 7)

While reflecting about the relevance of various legislative systems, participants showed a strong interest in the variety of individual attitudes (their own or others) regarding donation. They imagined possible reasons for refusing donation, considered how representations of the body and death may vary between individuals, discussed contextual factors that may affect individual decisions, and reflected on the fact that people may not have a clear view on their preferences.

Participants showed great interest in attempting to explain why one may refuse organ donation (n participants = 14; n occurrences = 30). As explanatory factors, they mentioned religious beliefs, or burial customs, the fact that it is not a favourable time to ask for donation while the family is mourning, beliefs that the organs are not of good enough quality for transplantation, or strong negative emotional reactions to the prospect of a loved one’s body being dissected.

“It is hard for them [the family members] to make that decision and to imagine that we are going to skin the deceased in order to give him to others.” (Participant 11)

Participants addressed the topic of the body. Whereas some people find it important to preserve the integrity of the human body, others considered organ donation as a helpful form of reviving or even recycling.

“I still perceive the human as a machine, even if it's a very sophisticated machine, it is made of spare parts. Well, personally, If one day, I am no longer here, if my spare parts can be useful to someone, I don't need them any more.” (Participant 4)

Participants also reflected on the necessity to differentiate between different organs, some of which (e.g., cornea) are more difficult to donate. Finally, some mentioned that it might be difficult for relatives to accept the irreversibility of the death diagnosis.

Participants pointed out a great variety of external factors that may affect individual decisions to donate (n occurrences = 30): the tone of speech used by physicians while making the request, the timing of the request within the mourning process, the fact that the law facilitates the choice to donate (related to the opt-out system), or reversely, the counterproductive tensions generated when physicians need to follow the law against the views of the family.

Some participants thoughts that younger people might not be prepared to make a decision on such an important matter whereas others found it appropriate to address the issue because it helps to reach a higher level of maturity.

“A young person, who thinks she is eternal at her age, will she ask herself questions like these ? These are existential questions. At 20, will we say yeah, if something happens to me I don't want to, or yes, I would agree? I've never heard a young person talk like that.” (Participant 8)

Some participants mentioned that the mandated choice system should allow the possibility to delay the decision to donate or not.

Of the 15 participants interviewed, at the end of the interview, 14 stated that they wanted to give their organs and one was not ready for it although she was favourable to organ donation. Interestingly, however, the interview seemed to help them make their decision. While pondering, many participants noted that it is a complex issue.

“In the course of our lives we don't necessarily think about it [organ donation], (...) of course we all have a sense that we're going to die one day and all that, but maybe we don't necessarily think about what will happen to our organs or all those things. In any case, I personally hadn't thought about it.” (Participant 1)

Participants also expressed the fact that there are many reasons for not speaking out, including forgetfulness, lack of time, lack of interest, or even laziness. Many mentioned the need to feel concerned about the situation in order to take the time to reflect on it.

Three broad topics of discussion emerged from our code grouping analysis: participants expressed requirements that a good system of organ donation should fulfil, they discussed the difficulties and reasons to cast doubt about the adequacy or efficiency of any system, and they paid particular attention to personal attitudes regarding donation. A more fine-grained description of the subtopics allows identification of a series of major assumptions, worries, and values that cut across these three broad topics. In what follows, we highlight these elements.

Our participants strongly endorsed organ donation, and were concerned by the current organ shortage. They evaluated the current situation as not efficient enough, notably due to a lack of information, administrative burden, and lack of advanced directives, which increases the probability that families refuse the donation. They wished for improvements and actively tried to think of useful measures that could help increase organ donation.

All agreed that an effective legal framework should contribute to reducing organ shortage, but not by any means. Other values and worries need to be considered. Two connected moral values played a prominent role in participants’ reasoning: respect and liberty of decision. These values were by far the most frequently mentioned and were at the centre of participants’ evaluations of the various organ donation policies, both when they discussed the requirements for a good system and the difficulties and reasons to doubt about a system.

More specifically, along with medical ethics principles [12, 13], all participants valued respect for the deceased's wishes: it is important to seek advanced directives, ask relatives about the deceased’s presumed will, and make final decisions according to that will. Participants also evaluated the value of policies according to the extent to which they promote citizens’ lifetime thought, decision and expression of their preferences regarding organ donation.

Further, what seemed important to many participants was citizens’ liberty to decide. Thus, although advocating active promotion of decision-making, many participants expressed worries about too intrusive measures, which would endanger citizens’ right to postpone their decision, to make no decision, or to change their mind. Participants paid particular attention to the acceptable level of pressure that can be imposed on citizens, and to the easiness and flexibility of administrative procedures designed to record advanced directives.

The roles and the rights of relatives were important themes of discussion. Participants identified relatives as the tragic survivors who have a right to give their opinion, who may not share the deceased’s view, and who may have to make a choice under uncertainty about the deceased’s wishes (which is both distressing and conducive to refusal). These conflicting inputs generated divergent worries and opinions among participants. Overall, they thought that a good policy should optimise the information about the deceased's wishes, thereby alleviating the difficulty and psychological burden of making the final decision. Some participants pointed out that the soft opt-out system could alleviate families' burden of decision or optimise the decision-making process. Some participants were concerned about the possibility that relatives, despite being the best informants about the deceased's wishes, may decide to override them and refuse donation. Opinions diverged on the relevance of consulting relatives when the deceased had formally expressed their decision, or if an opt-out system is enforced.

Our analysis also shows a very interesting feature of participants’ way of thinking: they focused very much on “individuals”: their rights, and the reasons why they accept or refuse to donate. This focus not only emerged from our analysis as a third broad topic of discussion. It was also overwhelmingly present across discussions over what is a good system (e.g., it is important to motivate individual citizens to express their preferences during their lifetime) or what difficulties could impede or discredit a system (e.g., intrusive measures may constrain individual liberty to decide). Topics linked to justice, equity, or equal distribution of goods were only marginally present in participants’ lines of thought.

Less often, participants pointed out further difficulties relevant to deciding on organ donation policies: notably, they worried about respect for the integrity of the human body, and about the tensions generated if physicians need to follow the law against the view of the family.

Most participants evaluated the current opt-in policy as suboptimal, but many also recognised that there is such a diversity of situations related to organ donation that no system is perfect. Many were thus in doubt whether the opt-in or the soft opt-out policy should be promoted. The hard opt-out policy was generally evaluated as very intrusive. In accordance with other studies [14], most participants endorsed the additional mandated choice model because it is a direct response to one of their main concerns: the lack of advanced directives on organ donation. However, even regarding this model, they expressed worries regarding the possibility that it might be enforced in a way that would restrict individual liberties.

Participants spent a great deal of time discussing factors that are not tied to a given organ donation policy, which shows that a choice of legislation cannot resolve all difficulties. Notably, they elaborated on the need for more awareness-raising measures, for providing more information to citizens, for promoting discussion in society and in the educational system, on the fact that primary care physicians could ask the organ donation question during routine check-ups, on the importance of facilitating administrative procedures, on the timing of the request to the family when a deceased is identified as eligible, etc.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, we only recruited within the French-speaking Geneva population. It may be the case that German- or Italian-speaking citizens show different patterns of concerns. Moreover, our sample did not include participants who were strongly opposed to organ donation. Since less than 10% of Swiss citizens are opposed to organ donation [2] (despite the high refusal rate by families [3]), it is not a surprise that we failed to recruit a representative member of this minority group. Nevertheless, it important to keep in mind that our results are only applicable to a population favourable to organ donation. Citizens opposed to organ donation may have raised more issues than those reported in this article. Finally, as with all qualitative research, occurrences signify salience rather than frequency and should not be generalised as quantitatively representative.

To all participants, we offer our gratitude, respect and thanks.

This study was conducted without outside funding at the Institute for Ethics, History, and the Humanities at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Geneva.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. SH and CC are members of the Swiss national advisory commission on biomedical ethics, which has published a position on consent for organ donation. SH is a member of Swisstransplant. JK reports no potential conflict of interest.

1. The Federal Council [Internet]. Federal Act on the Transplantation of Organs, Tissues and Cells. of 8 October 2004 [Status as of 1 January 2019]. Available from: https://www.admin.ch/opc/fr/classified-compilation/20010918/index.html#a8%20

2. Swisstransplant [Internet]. Questionnaire représentatif de la population. 2015 [cited 2020 Dec 23]. Available from: https://www.swisstransplant.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Swisstransplant/Publikationen/Wissensch_Publikationen/DemoSCOPE_resultat_Swisstransplant_FR.pdf. French.

3. Swisstransplant [Internet]. Jahresbericht 2019. [cited 2020 Dec 23]. Available from: https://www.swisstransplant.org/en/swisstransplant/publications/annual-figures/

4. OFSP [Internet]. Chiffres relatifs au don et à la transplantation d’organes en Suisse. [Status as of 1 January 2019]. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/fr/home/zahlen-und-statistiken/zahlen-fakten-zu-transplantationsmedizin/zahlen-fakten-zur-spende-und-transplantation-von-organen.html. French.

5. International Registry in Organ Donation and Transplantation . Database [cited 2021 Mai 05]. Available from: https://www.irodat.org/?p=database

6. Jeune Chambre International Riviera [Internet].Pour sauver des vies en favorisant le don d’organes. [cited 2020 Dec 23]. Available from: https://www.initiativedondorganes.ch/ French.

7. Rosenblum AM , Horvat LD , Siminoff LA , Prakash V , Beitel J , Garg AX . The authority of next-of-kin in explicit and presumed consent systems for deceased organ donation: an analysis of 54 nations. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2012;27(6):2533–46. doi: https://https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfr619

8. Arshad A , Anderson B , Sharif A . Comparison of organ donation and transplantation rates between opt-out and opt-in systems. Kidney International 2019; 95:1453–1460. doi: https://https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2019.01.036

9. National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics [Internet]. Prise de position 31/2019. Don d’organes. Considérations éthiques sur les modèles d’autorisation du prélèvement d’organes. [cited 2020 Dec 23]. Available from: https://www.nek-cne.admin.ch/fr/publications/prises-de-position/ French.

10. Conférence des Évêques Suisses [Internet]. Prise de position - initiative et contre projet du Conseil fédéral pour le don d'organes. [cited 2020 Dec 23]. Available from: http://www.commission-bioethique.eveques.ch/nos-documents/prises-de-position/don-d-organes2/ French.

11. Shanmugarajah K , Villani V , Madariaga ML , Shalhoub J , Michel SG . Current progress in public health models addressing the critical organ shortage. International Journal of Surgery 2014;12(12):1363–8. doi: https://https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.11.011

12. Shaw D , Lewis P , Jansen N , Samuel U , Wind T , Georgieva D , et al. Family overrule of registered refusal to donate organs. Journal of the Intensive Care Society 2020; 21:179–182. doi:https://https://doi.org/10.1177/1751143719846416

13. Wilkinson TM . Individual and Family Decisions About Organ Donation. J Appl Philos. 2007;24(1):26–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5930.2007.00339 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5930.2007.00339.x

14. Lauerer M , Kaiser K , Nagel E . Organ Transplantation in the Face of Donor Shortage - Ethical Implications with a Focus on Liver Allocation. VIS 2016; 32:278–285. doi:https://https://doi.org/10.1159/000446382

Table S1Table of codes

| Number of occurrences | Second order codes | Third order codes | Fourth order code |

| 19 | Respect for the wishes of the deceased (eligible donor) | Respect for the wishes of the donor | Requirements for a good system |

| 12 | Respect for the wishes of citizens (potential donors) | “ | “ |

| 15 | Impact of organ donation on relatives | Respect for the relatives | “ |

| 63 | Role or relatives | “ | “ |

| 4 | Relatives play an important and positive decision role in the current organ donation policy | “ | “ |

| 14 | The strong opt-out restricts relatives’ decision power | “ | “ |

| 21 | Moral statement in favour of organ donation | Other moral statements | “ |

| 75 | Moral statement on the process of donation | “ | “ |

| 2 | Mandated choice's efficacy in administrative procedures | Optimisation of administrative procedures | “ |

| 5 | Administrative ease of the opt-out system | “ | “ |

| 5 | Current opt-in system is problematic from an administrative point of view | “ | “ |

| 6 | Adding administrative procedures to the mandated choice system reduces its efficacy | “ | “ |

| 1 | Active choice is better than passive choice | Proposals for a good system | “ |

| 2 | Proposals for alternative systems | “ | |

| 3 | Advices for how to put a system into practice | “ | “ |

| 2 | Proposals for decision aids | “ | “ |

| 13 | Relatives may ignor the wishes of the deceased | Risk of failing to respect the wishes of the deceased | Difficulties and reasons to reject a system |

| 1 | The opt-out system may go against the wish of the deceased | “ | " |

| 11 | Lack of respect of the wishes of the deceased | “ | " |

| 9 | Strong opt-out system: weight of law at cost of the wishes of individuals | Risk of being too intrusive | " |

| 1 | It's a problem to force reflection on the question | “ | “ |

| 6 | Statements that a system is intrusive | “ | “ |

| 30 | Arguments in favour of organ donation | Difficulty to provide the needed organs | “ |

| 11 | Factors that help promote donation | " | " |

| 4 | Why a relative accepts donation | " | " |

| 8 | Current opt-in system does not sufficiently promote donation | " | " |

| 16 | Opt-out system facilitates donation | " | " |

| 7 | Lack of knowledge of the wishes of the deceased | Difficulty to promote decision-making | “ |

| 9 | Need of awareness-raising measures | " | “ |

| 19 | Factors that help knowing the deceased's wishes | " | “ |

| 9 | 3rd option of mandated choice shouldn't be there | " | “ |

| 14 | Mandated choice makes the decision more easy | " | " |

| 4 | Opt-out system help knowing people's preferences | " | “ |

| 5 | Explanation of factors that impact on the decision | " | " |

| 10 | Explanation of own choice to give or not | " | " |

| 27 | Persisting difficulties | No system is perfect | “ |

| 4 | Uncertainty facing organ policies | " | “ |

| 6 | Uncertainty | People may not have a clear view on their preferences | Personal attitude regarding donation |

| 34 | Explanation for why people do not decide | " | “ |

| 3 | Participant's uncertainty about his/her own point of view | " | “ |

| 11 | Point of view on the human body | Participants' representations of the body and death | “ |

| 2 | Point of view on the diagnosis of death | " | “ |

| 13 | 3rd option of mandated choice is important | Impact of the context of the decision | “ |

| 4 | The role of the physician | " | “ |

| 3 | Maturity gained with age | " | “ |

| 10 | Impact of young age | " | “ |

| 14 | Reasons for relatives to refuse donation of their loved one's organs | Reasons for refusing donation | “ |

| 16 | Reasons against donation | " | “ |

The interview grid (original French version) is available in the PDF version of this article (appendix 2).