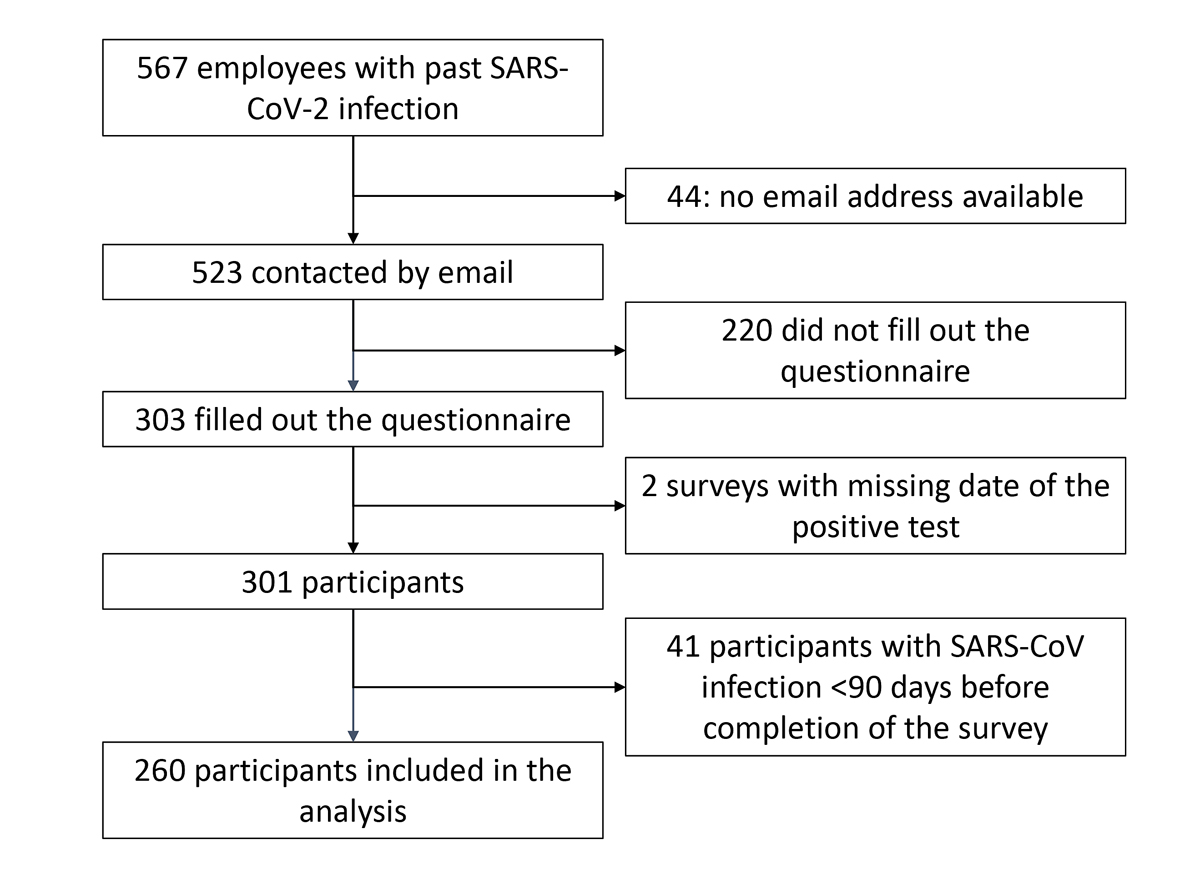

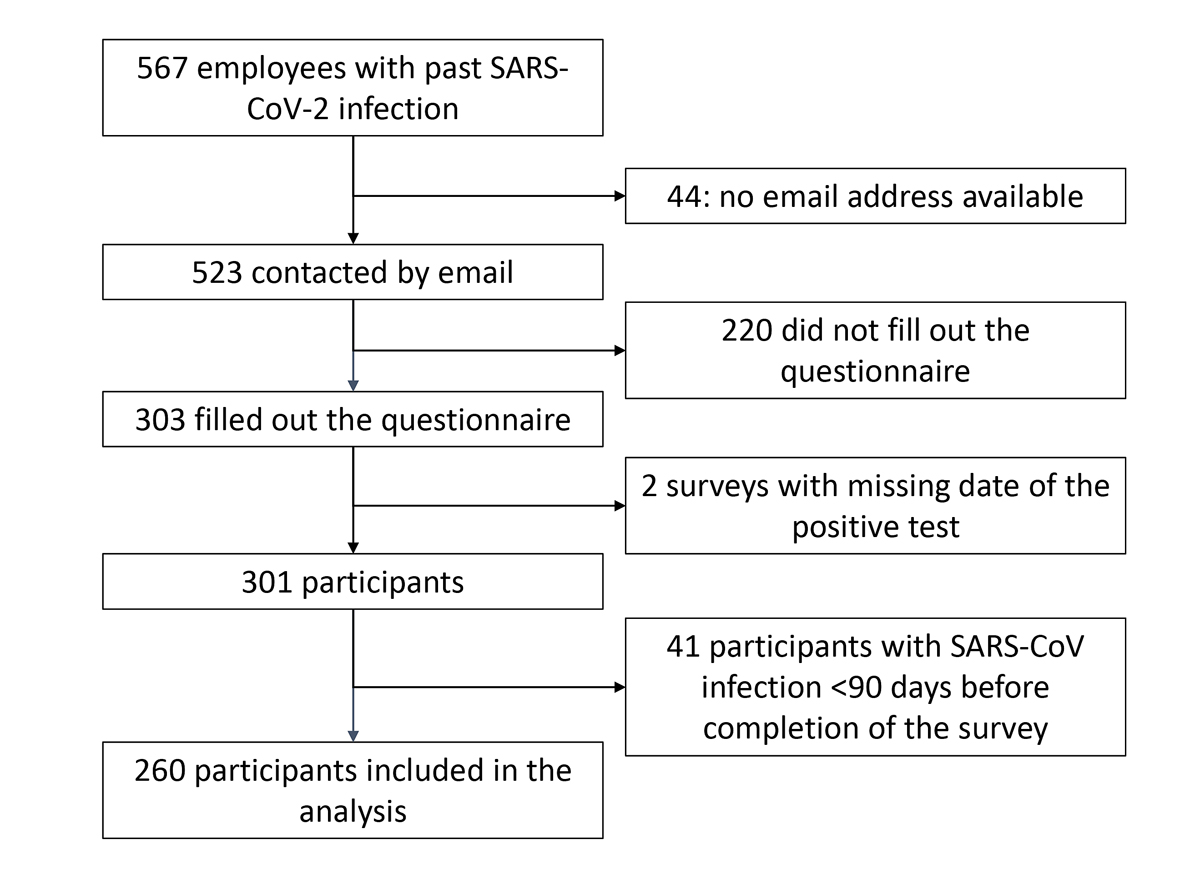

Figure 1 Study flow chart.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/SMW.2021.w30094

Reported rates of persisting symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection vary between 2.6% [1] and 76% [2], depending on the individual’s disease severity and comorbidity, as well as on the study methodology. A Swiss study reported that at least a third of ambulatory patients present persistent symptoms 30 to 45 days after diagnosis [3]. The most commonly reported symptoms were loss of taste or smell, cough, fatigue and headache. In a Norwegian survey-based study, 47% of female participants and 33% of male participants from a nonhospitalised cohort reported ongoing symptoms 1.5–6 months after COVID-19 [4]. The most commonly reported symptoms were dyspnoea and loss/disturbance of smell or taste.

Healthcare workers worldwide are at the forefront of the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic. They are at a particular risk of infection, acute disease and possible long-term consequences. Nevertheless, data on the long-term effects of COVID-19 on healthcare workers are scarce. In a Swedish study 26% and 15% of healthcare workers reported at least one moderate to severe symptom at 2 and 8 months after diagnosis, respectively [5]. To our knowledge, there are no data about long-lasting symptoms after COVID-19 in Swiss healthcare workers. This study aimed to assess the frequency of persisting symptoms after COVID-19 infection in healthcare workers at a university hospital in Switzerland.

This retrospective cohort study was conducted from 30 April 2021 to 3 June 2021 at the University Hospital Basel, enrolling employees with a reported SARS-CoV-2 infection between 1 March 2020 and 15 April 2021. The University Hospital Basel is a tertiary care centre in Switzerland with 855 beds, approximately 37,000 admissions per year and 7637 employees. To ensure rapid and adequate infection control measures in the case of in-hospital outbreaks, employees had to report to the Employee Health Service if they tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Further, the Staff Medical Service screened the hospital’s laboratory system on a daily basis for employees with a positive test.

On 30 April 2021, the Staff Medical Service sent a link to an online questionnaire to all employees who had a SARS-Cov-2 infection between 1 March 2020 and 15 April 2021. Seventeen days after the initial email a reminder was sent to all potential participants. The questionnaire could be answered up to 3 June 2021. Participation in the survey was voluntary and fully anonymous with questionnaires not being linked to the email address. To ensure anonymity, we did not collect identifying information such as exact age. The locally responsible Ethics Committee (Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz) granted a waiver for this online survey.

In the questionnaire, participants were asked about potential comorbidities, approximate date of the positive test, suspected place of infection, workdays missed, if admission was required and how long it took them to return to the same level of health as before the illness. Only participants who reported not having regained their usual level of health at the time they completed the survey were asked about their exact symptoms (checkboxes with suggestions and a possibility to insert free text) and what percentage of their pre-disease health they consider themselves to be at. See supplementary appendix for the full original questionnaire (in German) and an English translation.

Data were collected using REDCap electronic data capture tools. The main outcome variable of interest was presence of self-reported symptoms 90 days after COVID-19 diagnosis. The secondary variable of interest was self-reported symptom persistence for more than 12 months in participants for whom the infection took place more than 1 year ago. This was an explorative descriptive study without a specific hypothesis or sample-size determination. To describe the study population, continuous variables were summarised as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), categorical variables as counts and proportions. We used uni- and multivariable logistic regression to test for associations between participant baseline characteristics and reported symptom persistence. Due to a limited number of participants with persisting symptoms at day 90 (main variable of interest), we used a forward stepwise selection for the multivariable logistic regression. Baseline characteristics showing an association at a two-sided significance level <0.1 in univariate analysis were included into the multivariable model. Results from logistic regressions are reported in unadjusted odds-ratios (ORs) and adjusted ORs (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). All analyses were run on STATA version 15.1.

By 31 May 2021, 567 employees were registered in the Staff Medical Service database with a past SARS-CoV-2 infection. Among them 397 (70%) were male, and median age of these employees was 37 years (IQR 28–49). We could not contact 44 because they had changed workplace and thus the email address was not functional any more.

Of the remaining 523, 303 (57.9%) filled in the questionnaire. Six questionnaires were incomplete: four had only minor gaps, two were excluded because the date of the positive test was missing. Of the remaining 301 respondents, 260 had a SARS-CoV-2 infection ≥90 days previously and were included in the analysis (figure 1). The mean age range of these 260 participants was 30–39 years, 196 (75.4%) were female and 167 participants (64.2%) had direct patient contact at work. Only three (1.2%) participants had been hospitalised, none of them in intensive care.

Figure 1 Study flow chart.

Table 1 displays all baseline characteristics of participants, including the information about missing data.

Table 1Baseline characteristics of the patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection ≥90 days ago.

| n/N (%) or median (IQR) | ||

| Age group | 10–19 | 5/260 (2.3) |

| 2029 | 68/260 (26.2) | |

| 3039 | 66/260 (25.4) | |

| 4049 | 56/260 (21.5) | |

| 5059 | 52/260 (20.0) | |

| 6069 | 12/260 (4.6) | |

| Female gender | 196/260 (75.4) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.8 (21.526.7) | |

| Co-morbidities | Arterial hypertension* | 18/ 258 (7.0) |

| Asthma° | 27/259 (10.4) | |

| COPD* | 2/ 258 (0.8) | |

| Other lung disease° | 0/259 (0) | |

| Depression* | 5/258 (1.9) | |

| Active cancer* | 0/258 (0) | |

| Hypothyroidosis* | 12/258 (4. 7) | |

| History of myocardial infarction or stroke* | 1/258 (0.4) | |

| History of depression or state of exhaustion * | 23/258 (8.9) | |

| History of cancer* | 6/258 (2.3) | |

| Job type | Nursing staff | 123/260 (47.3) |

| Medical staff | 38/260 (14.6) | |

| Diagnostic staff | 14/260 (5.4) | |

| Therapeutic staff (e.g., physical therapy | 7/ 260 (2.7) | |

| House staff (cleaning, logistics..) | 15/260 (5.8) | |

| Administrative staff | 37/260 (14.2) | |

| Other | 26/260 (10.0) | |

| Days between positive test and completion of survey | 167.7 (142.7193.1) | |

| Hospitalized for COVID-19 | 3/260 (1.2) | |

| Hospitalized on ICU for COVID-19 | 0/260 (0) | |

IQR: interquartile range: ICU: intensive care unit; BMI: body mass index; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. * Value missing for two participants, °value missing for one participant.

Sixty-nine (26.5%) participants reported not having regained their usual level of health or having had a symptom duration of more than 3 months. Forty-five participants reported details about their symptoms. Symptoms most commonly reported were fatigue (31 participants, 68.9%), impaired sense of taste or smell (23 participants, 51.1%) and general weakness (21 participants, 46.7%). Table 2 displays all reported symptoms and their frequency among these 45 patients. Twenty-seven participants reported having regained ≥80% of their pre-SARS-CoV-2 level of health and only three participants reported not having regained at least 50% of their pre-COVID-19 level of health. Those with persisting symptoms for over 90 days reported 1412 cumulative missed workdays (median 15, IQR 10–21, no missing data). The 191 participants with a symptom duration of 90 days or less reported 1801 cumulative missed workdays (median 10 days, IQR 711). Data about lost workdays were missing in 5 of these 191 participants.

Thirty-seven participants reported the diagnosis of SARS-CoV infection to have been made more than 365 days previously. Among these, five (13.5%) reported not having regained their usual level of health. The most common reported symptoms among them were fatigue (5 participants, 100%), general weakness (4 participants, 80%) impaired sense of taste or smell and palpitations (3 participants, 60%). All these participants reported having regained at least 60% of their pre SARS-CoV-2 infection level of health. Those with persisting symptoms over 365 days reported 106 cumulative missed workdays (median 21, IQR 18–21, no missing data). The 32 patients who reported the diagnosis of SARS-CoV infection to have been made more than 365 days ago with a symptom duration of 365 days or less reported 303 cumulative missed workdays (median 10 days, IQR 5–10 days, no missing data).

In the univariate analysis, a history of depression or history of state of exhaustion (OR 4.36, 95% CI 1.64–10.56), older age and any lung disease (OR 3.80, 95% CI 1.70–8.49) were associated with symptom persistence for more than 90 days (table 3). These associations persisted in the multivariable analysis that included age, any lung disease, arterial hypertension and history of depression or of state of exhaustion (table 3).

Table 2Reported symptoms of the 45 participants with a symptom duration of more than 3 months who reported their symptoms. Only participants with ongoing symptoms at the time they completed the survey were asked about their symptoms. Participants could report more than one symptom.

| Symptom | Number (total = 45) | Percent |

| Fatigue | 31 | 68.9 |

| Loss/disturbance of smell or taste | 23 | 51.1 |

| General weakness | 21 | 46.7 |

| Concentration problems | 20 | 44.4 |

| Breathing problems | 19 | 42.2 |

| Sleep difficulties | 13 | 28.9 |

| Headache | 10 | 22.2 |

| Dizziness | 10 | 22.2 |

| Chest pain | 9 | 20.0 |

| Muscular pain | 9 | 20.0 |

| Loss of hair | 8 | 17.8 |

| Palpitations | 7 | 15.6 |

| Cough | 5 | 11.1 |

| Joint pain | 4 | 8.9 |

| Other | 4 | 8.9 |

| Feverish feeling | 3 | 6.7 |

| Decreased appetite | 3 | 6.7 |

| Digestive problems | 2 | 4.4 |

Gender, function in the hospital, e.g., nurse, physician, administration, and comorbidities did not show a significant association with symptom persistence at 3 months.

Table 3Characteristics of patients with positive test ≥90 days before completion of the survey with and without symptoms at day 90 after diagnosis.

| Characteristic | Total n/N (%) | With symptoms N/n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR | Adjusted p-Value | |

| Gender | Male | 64/260 (24.6) | 14/64 (21.9) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Female | 196/260 (75.4) | 55/196 (28.1) | 0.72 (0.37–1.40) | 0.332 | |||

| Age | <30 | 74 / 260 (28.5) | 10/74 (13.5) | Ref | Ref | ||

| 30–49.99 | 122/260 (46.9) | 34/122 (27.9) | 2.74 (1.145.37) | 0.022 | 2.83 (1.236.54) | 0.015 | |

| ≥50 | 64/260 (24.6) | 25/64 (39.1) | 4.1 (1.789.45) | 0.001 | 4.13 (1.6410.34) | 0.003 | |

| Any lung disease | 28/260 (10.8) | 15/28 (53.6) | 3.80 (1.708.49) | 0.001 | 3.78 (1.598.93) | 0.003 | |

| Arterial hypertension* | 18/258 (7.0) | 8/18 (44.4) | 2.45 (0.936.51) | 0.071 | 1.27 (0.433.75) | 0.663 | |

| Hypothyroidosis* | 12/258 (4.7) | 5/12 (41.7) | 2.12 (0.656.92) | 0.213 | |||

| History of depression or state of exhaustion * | 23/258 (8.9) | 13/23 (56.5) | 4.36 (1.8110.49) | 0.001 | 4.16 (1.6410.56) | 0.003 | |

| History of cancer* | 6/258 (2.3) | 2/6 (33.3) | n/a | n/a | |||

| Nursing staff | 123/260 (47.3) | 29/123 (23.6) | 0.75 (0.431.30) | 0.306 | |||

| BMI | <25 | 166/260 (63.9) | 39/166 (23.5) | Ref | |||

| 25–29.99 | 66/260 (25.4) | 20/66 (30.3) | 1.42 (0.752.67) | 0.284 | |||

| ≥30 | 28/260 (10.8) | 10/28 (35.7) | 1.81 (0.774.24) | 0.173 | |||

OR: odds ratio; aOR: adjusted odds ratio: CI: confidence interval, Ref: reference.

Multivariable model adjusted for: age group, any lung disease, hypertension and history of depression or state of exhaustion.

* Value missing for two participants

In this retrospective cohort study at a tertiary care hospital in Switzerland, 26.5% and 13.5% of healthcare workers with a history of mostly mild COVID-19 reported not having regained their usual level of health after 90 and 365 days, respectively. The most commonly reported persisting symptoms were fatigue, loss of sense of taste or smell and general weakness. Older age, history of depression or state of exhaustion and pre-existing lung disease were associated with symptom duration >90 days.

Our results are in line with a recent Swedish study, in which 26% of seropositive healthcare workers reported persisting symptoms 2 months after seroconversion [5]. In a Danish study, however, 40% of the participating healthcare workers reported symptoms at day 90 after diagnosis, although they were not asked about fatigue, which was among the most common symptoms in our study and in the Swedish study [6]. In this study participants were not asked whether they attributed their symptoms to their COVID-19 disease. Other studies showed an even higher prevalence of long-lasting symptoms [2, 7]. The higher proportions in other studies might be explained by the inclusion of more individuals with a severe course of COVID-19 or reporting of symptoms that were already present before the SARS-CoV-2 infection. In our study, the majority of participants with symptoms lasting longer than 3 months or 12 months reported only mild impairment of their perceived health state. Similarly, the median workdays lost are well below the reported symptom duration. This is in line with the Swedish study mentioned above [5] and a British study [8]. In the former, the majority of participants reporting symptoms lasting at least 2 months reported mostly a mild impairment in their work, social and home life using the Sheehan Disability Scale. In the latter, only 2% of healthcare workers who had ongoing symptoms 3–4 months after the suspected infection reported taking sick leave after recovering from the acute illness. Similarly, a large patient, and health insurance registry-based study showed only minor increases in healthcare system use and medication prescription in patients after COVID-19 [9]. However, the comparisons are limited due to differences in methodology and the length of time between the infection and the survey.

In our study, a history of depression or state of exhaustion, pre-existing lung disease and increasing age were associated with persisting symptoms 90 days after diagnosis. Previous studies reported older age and comorbidities including lung conditions – but not history of depression or state of exhaustion – as risk factors for persisting symptoms after COVID-19 [1,2].

Our study has several limitations. The study relied on participants’ ability to recall their health state 90 and 365 days after diagnosis. As participants reported events in the past, there is a risk for a recall bias. Although the response rate was good, we do not know whether differences between employees who responded to the survey introduced a selection bias. We asked participants about specific symptoms only if they reported not having reached their usual level of health. However, some subtle symptoms might evade these questions. We did not use a validated questionnaire. As there is no SARS-CoV-2 negative control group in our study, we cannot exclude the possibility that some of the described symptoms or the absence from work might not be related to the SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Finally, compared with all employees with a positive SARS-CoV-2 test, women were overrepresented among the respondents. The strength of our study is the inclusion of a relatively large number of participants from a defined, unselected group of including participants diagnosed more than 365 days previously with COVID-19.

In conclusion, our study shows that a relevant proportion of healthcare workers with mild COVID-19 report persisting symptoms over 3 and 12 months. Although in the majority of cases symptoms are mild, this study highlights the need for further research into causes and therapy.

We would like to thank the staff of the University Hospital Basel for taking part in this survey, thus making this study possible. Also we would like to thank the staff of the Division of Infectious Diseases and Hospital Epidemiology, Employee Health Service and Medical Outpatient Clinic of the University Hospital Basel for their valuable input to the design of this study.

This study had no specific funding and was part of the quality assessment for healthcare workers at the University Hospital Basel

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

1. Sudre CH , Murray B , Varsavsky T , Graham MS , Penfold RS , Bowyer RC , et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID [Internet]. Nat Med. 2021 Apr;27(4):626–31. [cited 2021 Mar 26] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33692530 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01292-y

2. Huang C , Huang L , Wang Y , Li X , Ren L , Gu X , et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021 Jan;397(10270):220–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8

3. Nehme M , Braillard O , Alcoba G , Aebischer Perone S , Courvoisier D , Chappuis F , et al. COVID-19 Symptoms: Longitudinal Evolution and Persistence in Outpatient Settings [Internet]. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Dec;M20–5926. [cited 2020 Dec 16] Available from: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M20-5926

4. Stavem K , Ghanima W , Olsen MK , Gilboe HM , Einvik G . Persistent symptoms 1.5-6 months after COVID-19 in non-hospitalised subjects: a population-based cohort study [Internet]. Thorax. 2021 Apr;76(4):405–7. [cited 2021 Aug 18] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33273028 https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216377

5. Havervall S , Rosell A , Phillipson M , Mangsbo SM , Nilsson P , Hober S , et al. Symptoms and Functional Impairment Assessed 8 Months After Mild COVID-19 Among Health Care Workers. JAMA [Internet]. 2021 Apr 7 [cited 2021 May 14]; Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2778528

6. Nielsen KJ , Vestergaard JM , Schlünssen V , Bonde JP , Kaspersen KA , Biering K , et al. Day-by-day symptoms following positive and negative PCR tests for SARS-CoV-2 in non-hospitalized healthcare workers: A 90-day follow-up study [Internet]. Int J Infect Dis. 2021 Jul;108:382–90. [cited 2021 Aug 20] Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1201971221004343?via%3Dihub https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.05.032

7. Carvalho-Schneider C , Laurent E , Lemaignen A , Beaufils E , Bourbao-Tournois C , Laribi S , et al. Follow-up of adults with noncritical COVID-19 two months after symptom onset. Clin Microbiol Infect [Internet]. 2020 Oct 5 [cited 2020 Dec 16]; Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1198743X20306066?pes=vor

8. Gaber TA , Ashish A , Unsworth A . Persistent post-covid symptoms in healthcare workers [Internet]. Occup Med (Lond). 2021 Jun;71(3):144–6. [cited 2021 Aug 20] Available from: https://academic.oup.com/occmed/article/71/3/144/6217385 https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqab043

9. Lund LC , Hallas J , Nielsen H , Koch A , Mogensen SH , Brun NC , et al. Post-acute effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection in individuals not requiring hospital admission: a Danish population-based cohort study [Internet]. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 Oct;21(10):1373–82. [cited 2021 May 31] Available from: www.thelancet.com/infectionPublishedonline https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00211-5

The appendix is available in the pdf version of the article.