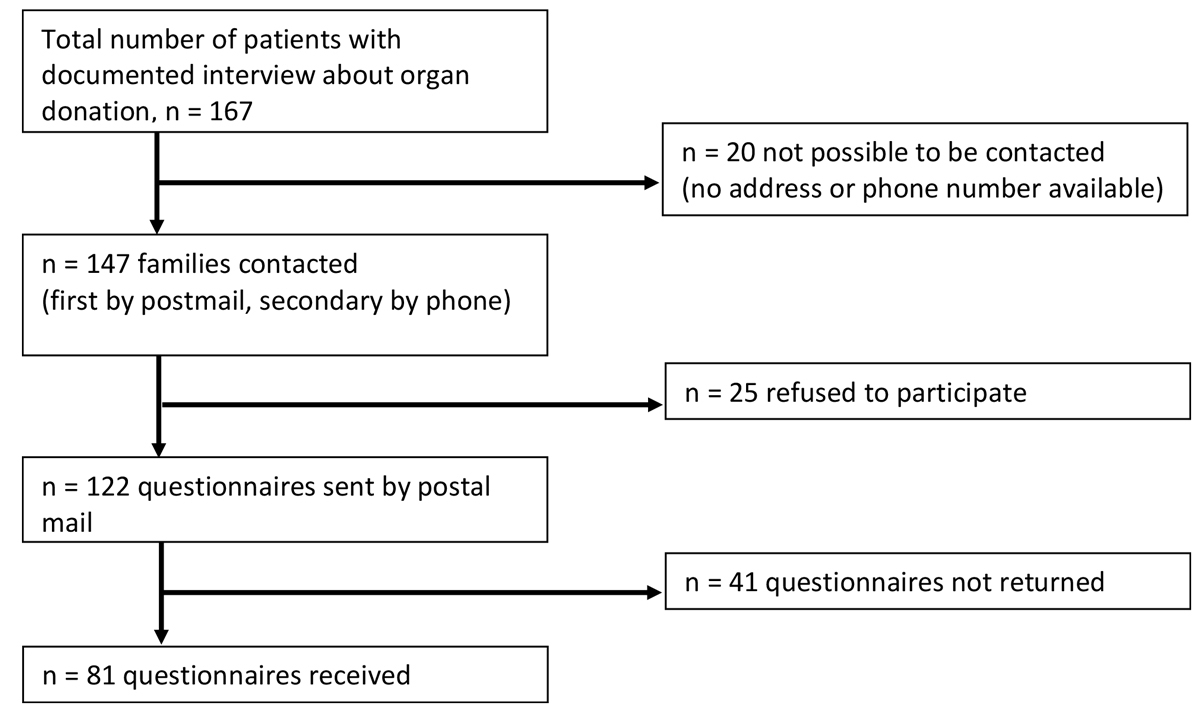

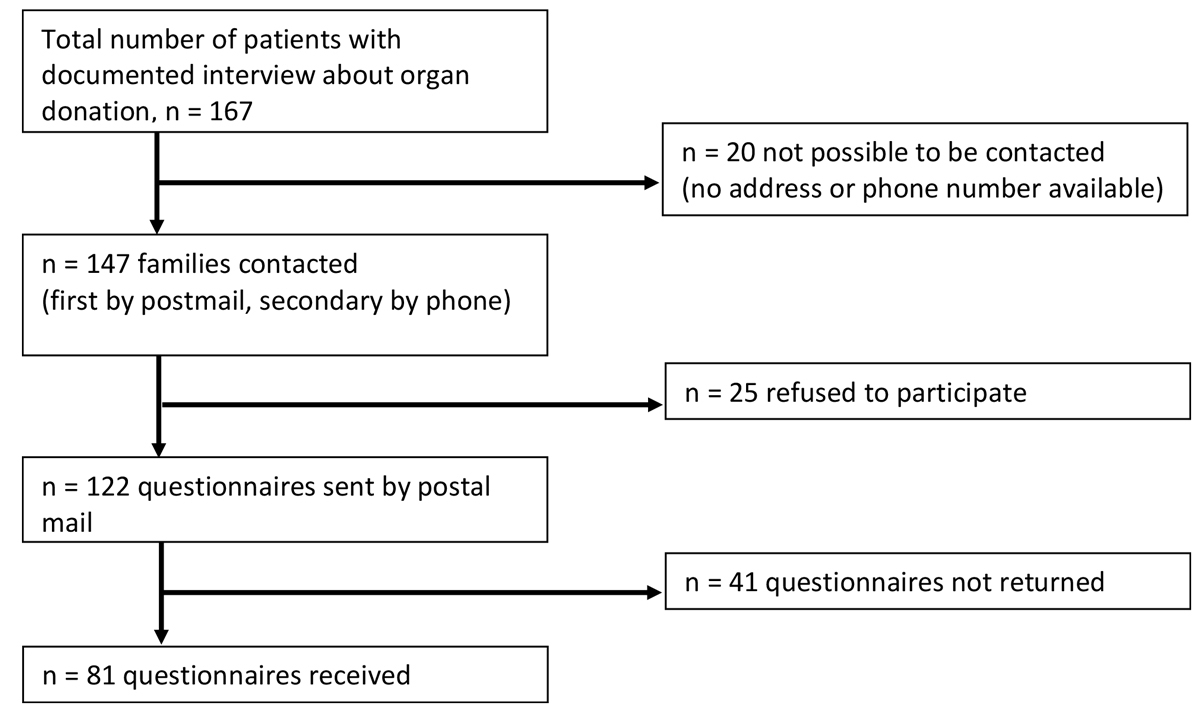

Figure 1 Study flow chart illustrating the sequence of next of kin contact and questionnaire delivery.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2021.20515

AIM OF THE STUDY: In the Swiss population, attitudes to organ donation are mostly positive. However, a high refusal rate by the next of kin may be observed. We aimed to investigate potential underlying reasons.

METHODS: In two independent Swiss tertiary care academic centres 167 next of kin were confronted with potential organ donation, over a period of 18 to 24 months. Of these, 147 could be contacted and were asked ≥6 months later to participate in a post-hoc survey (72-item questionnaire). Aspects related to conversations, time and care in the intensive care unit (ICU), underlying concepts for organ donation, impact on mourning, and other potential influencing factors were addressed.

RESULTS: The overall return rate was 66%. Seventy four of 77 (96%) next of kin stated that the request for organ donation was appropriate and they agreed to address the issue. Personal attitudes of next of kin regarding organ donation correlated with the decision for or against organ donation (p <0.0001). Thirteen percent (8/62) reported that conversations with ICU physicians changed their decision. In 56% (18/32) of reports when organ donation was refused, the next of kin stated that presence of a documented will might have changed their decisions. Mourning was reported to be impaired by the request for organ donation in 8% (6/71), facilitated in 14% (10/71) and not affected in 77% (55/71) of cases. Twenty-seven percent (16/59) indicated that an opt-out policy for organ donation would subjectively have facilitated their decision and 81% (34/42) of consenting next of kin stated that an objection law should be put into place (p <0.0001).

CONCLUSIONS: In this observational study, the majority of the next of kin stated that addressing organ donation did not affect mourning. Presence of a presumed will could likely facilitate grief and provide comfort for affected families. (Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov. Identifier: NCT 03612024. Date of registration: 24 July 2018.)

Solid organ transplantation is an established therapy for end-stage organ failure [1, 2]. In Switzerland, federal law regulates organ and tissue transplantation, as well as organ donation via an opt-in system [3]. It is common sense that next of kin are always asked for consent to organ donation, even in the presence of a presumed positive patient will for organ donation. In clinical practice, an existing written or known presumed will of the patient is usually adhered to by the next of kin. In the case of a potential donor without written consent to organ donation and no next of kin available for consenting, organ donation is unlawful.

There is a growing mismatch between the limited number of donated organs and the increasing number of patients on transplantation waiting lists [4]. In Switzerland, the organ donation rate per million population (pmp) was 17.2 in 2017 [5]. Apart from Germany (9.7 pmp), all neighbouring countries have substantially higher rates: Austria 24.7 pmp, France 28.7 pmp, Italy 28.5 pmp [6]. Thus, a Swiss national action plan was implemented by the Federal Department of Health in 2014 to improve education/training, to establish national guidelines / checks, to clarify financial structures and to conduct public campaigns with the ultimate goal of increasing donation rates [7].

Refusal rates following a request for organ donation are high [4]. Interestingly, surveys on general attitudes towards organ donation in Switzerland reveal an acceptance rate of 92%, and 81% are willing to donate organs posthumously [8], whereas a consent rate of only about 30–40% is observed in many Swiss hospitals [9], including the participating institutions. As the underlying reasons are unclear, we collected answers and experiences from families confronted with organ donation after brain death (DBD) via a questionnaire-based investigation. Aspects related to conversations, time and care in the intensive care unit (ICU), underlying concepts (including the concept of brain death), impact on mourning, and other potential factors that might influence decision making were addressed.

The questionnaire was developed in Bern and offered to the five Organ Donation Networks in Switzerland. Data were collected in the adult ICUs of two Swiss tertiary care academic centres (Department of Intensive Care Medicine, University Hospital of Bern and Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Lausanne University Hospital [CHUV]), with a catchment area of about 3–3.5 million inhabitants. At the time of the study, a donation after brain death (DBD) programme, but not donation after cardiac death (DCD), was established in Bern, whereas in Lausanne, both programmes were implemented. The 72-item questionnaire (German and French versions available) was designed in an exploratory manner by the team in Bern with the support of an external psychologist. The questionnaire addressed issues regarding conversations, time and care in the ICU, underlying concepts (including the concept of brain death), impact on mourning, and other potential factors relevant for decision-making (the questionnaires provided in the appendix in the PDF version of the manuscript).

All deaths in the ICU over a period of 18 months (Bern January 2016 to June 2017 and Lausanne July 2016 to December 2017) were screened for whether or not organ donation (DBD) was requested. In the event of a request, contact details of the primary contact person (next of kin) were recorded. At least 6 months after the death and following provision of written information, next of kin were contacted by telephone by an intensivist or by transplant coordinating staff, who requested permission to send the anonymous questionnaire. Subsequently the questionnaire was mailed in paper form to each family. If no contact by telephone was possible after several attempts (usually three times), the questionnaire was sent with an additional explanatory letter. No reminders were sent. No financial benefits applied. The need of approval by the local competent ethics committee of human research was waived in Bern (Nr. KEK-2017-00943). In accordance with the recommendations of the ethics committee of Canton de Vaud, no approval was required in Lausanne.

The following clinical routine applied to potential organ donors in both institutions: according to guidelines and federal law, the family was first informed about the medical condition of the patient, including disclosure of the futile prognosis, or even brain death. In a second family meeting, the concept of brain death was explained as a prerequisite for organ donation. If the patient’s will regarding organ donation was available in written form, the next of kin were informed. In situations where written consent existed but the next of kin disagreed with organ donation, no organ was donated, although federal law places the patient’s will higher than that of next of kin . In these circumstances, organ donation is considered inadmissible and may complicate the next of kin grieving process.

If brain death had not yet occurred, the next of kin were informed that maintenance of ICU care would be established for a maximum of 48 hours. From the moment of brain death, another 12–20 hours are typically required for organ evaluation and allocation, and planning of solid organ retrieval.

For statistical analysis, GraphPad Prism 6, GraphPad Software, USA was used. Data are presented as numeric values (n) or means with percentages, as appropriate. Contingency tables were analysed using a chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. A two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

As shown (figure 1), a total of 167 interviews on organ donation were analysed. Twenty next of kin could not be contacted for technical reasons (invalid address / telephone number, or death). A total of 147 families were contacted. Twenty-five next of kin refused to participate and 122 questionnaires were sent. Eighty-one questionnaires were returned and analysed, corresponding to a retrieval rate of 66% (fig. 1). Detailed data are given (table 1). Sixty-three percent (22/35) of the next of kin consenting to organ donation returned the questionnaire, and 68% (59/87) of next of kin refusing organ donation did so. Responses were analysed according to availability (see appendix in the PDF version of the manuscript). Most participants were female (n = 44, 54%). The following relationships to the deceased person applied: husband/spouse n = 34 (42%), parent n = 23 (28%), sibling n = 12 (15%), daughter/son n = 11 (14%), not specified n = 1 (1%). The personal attitude towards organ donation was declared as: consenting 55 (68%), dismissive in 10 (12%) and undecided in 14 (17%); 2 gave no response (2%). Out of all questionnaires, 49 (60%) covered next of kin who consented to organ donation and 32 (40%) were from next of kin who refused organ donation. The presumed will of the deceased patient was known in 50 cases (62%), comprising 15 written documents (donor card, patient directive) and 41 volitions; multiple answers were possible to this question. In 72% of cases (n = 58), the final next of kin decision on organ donation corresponded to the presumed will, whereas in one single case the decision taken by the next of kin did not match the presumed patient will. In that case, the next of kin declared that the patient was not aware that waiting for brain death would prolong treatment on the ICU. In Lausanne, fewer next of kin rejecting organ donation participated in the survey (only French-speaking) compared with Bern (German- and French-speaking): Lausanne 18 consenting, 5 refusing; Bern 31 consenting, 27 refusing. All results of the questionnaire are provided in the appendix in the PDF version of the manuscript.

Figure 1 Study flow chart illustrating the sequence of next of kin contact and questionnaire delivery.

Table 1 Characteristics and numbers of the interviews with next of kin regarding consent/refusal of organ donation.

| Lausanne | Bern | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers of deaths in ICU | 506 | 503 | 1009 | |

| Consent to organ donation |

All interviews | 53 | 114 | 167 |

| Yes | 27 | 32 | 59 | |

| No | 26 | 82 | 108 | |

| Missing contact data |

Total | 6 | 14 | 20 |

| Yes | 0 | 3 | 3 | |

| No | 6 | 11 | 17 | |

| Refuse to participate |

Total | 12 | 13 | 25 |

| Yes | 4 | 3 | 7 | |

| No | 8 | 10 | 18 | |

| Questionnaire mailed |

Total | 35 | 87 | 122 |

| Yes | 24 | 26 | 50 | |

| No | 11 | 61 | 72 | |

| Returned questionnaire | Total | 22 | 59 | 81 |

Ninety percent of next of kin (72/80) reported that they were provided with sufficient time to be with their loved one during the ICU stay. Further, 94% (75/80) felt well cared for during the time in the ICU. Thirty-eight percent (30/78) claimed that, at least partly, the period of waiting to see the patient was too long. Additionally, 40% (32/80) indicated that the waiting period until they could talk to an ICU physician was at least partly too long. This perception appeared significantly more often in the group refusing organ donation (p = 0.0028). In 83% (66/80) the aspect of potential organ donation was first addressed in the ICU, whereas in 11 cases (14%) the issue was first addressed either by the emergency department (n = 5) or by telephone (n = 6). In 41/79 (52%) of cases, potential organ donation was discussed in the first meeting with physicians. Forty-seven percent (35/74) of the organ donation requests occurred during off-hours, in the evening or during the night-time.

Ninety-six percent (74/77) of the next of kin reported that it was appropriate that organ donation was addressed. Ninety-nine percent (66/67) stated that they agreed with the physician’s obligation to address the issue of organ donation. Sixteen of 59 (27%) indicated that an opt-out policy to organ donation would have facilitated their decision and 34/38 (89%) who consented to organ donation stated that an objection law should be put into place. This was statistically significantly different (p <0.0001; Fisher’s exact test) from the group not consenting to organ donation (in this group, eight responses [35%] were in favour of an opt-out policy).

In 10/79 cases (13%), the next of kin were still hoping for medical improvement at the time of the organ donation request. Twenty-eight of 77 (36%) stated their surprise that organ donation was asked for and in 13/77 cases (17%) they felt upset by this question. With regard to the concept of brain death, 71/78 (91%) agreed that explanations were necessary. Fifty-nine percent (44/75) were convinced that a person who is declared “brain dead” has in fact actually died / is dead.

Five of 71 (7%) reported that the request impaired their mourning process, whereas 10/71 (14%) felt that it facilitated mourning and 55/71 (77%) reported no effect on mourning. In one case the mourning process was considerably impaired by the organ donation request. Details on consenting vs non-consenting next of kin are given in table 2. No significant differences were observed concerning mourning with regard to consenting and the knowledge of the presumed will of the deceased person (table 3).

Table 2 Comparison of the groups consenting / refusing organ donation (according to available data, no answer in italics).

|

Consent yes

n = 49 |

Consent no

n = 32 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The question regarding organ donation did upset me | |||

| – Yes | 4 / 8% | 9 / 32% | 0.0109* |

| – No | 45 / 92% | 19 / 68% | |

| – No answer | 0 | 4 | |

| Do you believe that a person who has been declared braindead is really dead? | |||

| – Fully applies | 30 / 68% | 14 / 45% | 0.1327† |

| – Partly applies | 12 / 27% | 14 / 45% | |

| – Does not apply | 2 / 5% | 3 / 10% | |

| – No answer | 5 | 1 | |

| The request for organ donation affected my mourning process: the process was… | |||

| …considerably impaired | 0 / 0% | 1 / 4% | 0.1507† |

| …impaired | 3 / 7% | 2 / 7% | |

| …not impaired | 32 / 73% | 23 / 85% | |

| …facilitated | 9 / 20% | 1 / 4% | |

| – No answer | 5 | 5 | |

Available data (percentages) are given. * Fisher’s exact test; † chi-square test

Table 3 Effect of consent, personal attitude towards organ donation and presumed will (if available) on the mourning process (71 answers, no answer = 10).

| Mourning process impaired | Mourning process facilitated | Mourning process not impaired | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consent to / rejection of organ donation process: (no answer = 0) | ||||

| – Consent | 3 / 50% | 9 / 90% | 32 / 58% | 0.133* |

| – Rejection | 3 / 50% | 1 / 10% | 23 / 42% | |

| Personal attitude towards organ donation: (no answer = 2) | ||||

| – I would donate | 2 / 50% | 10 / 100% | 38 / 84% | 0.003* |

| – I wouldn’t donate | 1 / 25% | 0 / 0% | 7 / 16% | |

| – I don’t know | 1 / 25% | 0 / 0% | 0 /0% | |

| The presumed will of the deceased person was… (no answer = 0) | ||||

| …known | 4 / 67% | 8 / 80% | 33 / 60% | 0.475* |

| …not known | 2 / 33% | 2 / 20% | 22 / 40% | |

Data available (percentages) are given. * Chi-square test.

Fifty-four of 62 next of kin (87%) reported that conversations with ICU physicians did not influence their decision regarding organ donation, whereas 8/62 (13%) indicated that it did change their decision. In cases of rejection of organ donation (n = 32), 4/32 responses (13%) signalled that having more time could have influenced their decision, and 6/32 (19%) stated that better explanation of the organ donation process might have changed their decision. In 18/32 cases (56%), the next of kin stated that an existing documented will of the deceased person might have changed the decision. Knowledge of the presumed will of the deceased patient and/or the language did not significantly affect consenting; however, personal attitudes regarding organ donation differed significantly between the groups with/without organ donation (table 4).

Table 4 Language, personal attitude, knowledge of presumed will of the next of kin, and correspondence of the final decision with the presumed will.

|

Consent yes

n = 49 |

Consent no

n = 32 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| German speaking | 21 / 47% | 24 / 53% | 0.006* |

| French speaking | 28 / 78% | 8 / 22% | |

| Personal attitude towards organ donation: | |||

| – I would donate | 44 / 92% | 11 / 35% | <0.0001† |

| – I wouldn't donate | 0 / 0% | 10 / 32% | |

| – I don't know | 4 / 8% | 10 / 32% | |

| – No answer | 1 | 1 | |

| The presumed will of the patient was… | |||

| …known | 32 / 64% | 18 / 36% | 0.4858* |

| …unknown | 17 / 55% | 14 / 45% | |

| Did the final decision correspond to the presumed will: | |||

| – Yes | 37 / 79% | 21 / 68% | 0.3198† |

| – No | 0 / 0% | 1 / 3% | |

| – Not known | 10 / 21% | 9 / 29% | |

| – No answer | 2 | 1 | |

Data available (percentages) are given. * Fisher’s exact test; † chi-square test.

The current study aimed to investigate in a detailed fashion next of kin decision making in regard to organ donation. In Bern, the refusal rate was higher than in Lausanne, with more interviews conducted in Berne (10.5% of deaths in Lausanne compared with 22.7% in Bern). In the light of potential differences in concepts of when to approach families, we rather focused on next of kin responses and not on potential centre-specific differences, which may be particular challenging to interpret. After analysing questionnaire-based responses from two independent academic centres in a descriptive fashion, we observed that the vast majority of the next of kin reported that being asked for organ donation was acceptable and did not affect mourning. They judged that the presence of a presumed will facilitated grief and provided help for families confronted with a decision as to whether to donate. Furthermore, we identified potential intra-hospital organisational aspects that might affect the final decision.

Previous investigations have pointed to the fact that “in-hospital reasons” may be at least partly responsible for increased refusal rates [10–13]. We found that prolonged waiting time, i.e., time from first contact of the next of kin to meeting a physician, appeared as a potential factor that might affect refusal rates. In general, time until a treating physician was available for consultation consistently appeared in the survey as an important and potentially related factor. Thus, it appeared that the underlying communication concept of organ donation may be important, and this could also be reflected by the fact that in some cases, next of kin decisions changed during the process of considering organ donation. Although the exact underlying reasons remain unclear due to the observational nature of this investigation, we demonstrated that the final decision to donate may not be static for some next of kin. The scientific concept of brain death and potential organ donation may be viewed as important to next of kin confronted with the request for organ donation [14–16].

We observed that the existence of a presumed will may have facilitated decision making, and that this could influence the mourning process and might provide comfort to the next of kin. A considerable number stated that the decision whether to donate might have been different if a known presumed will had existed (56%, n = 18, of all those rejecting organ donation in the interview). Thus, it appeared that presence of a presumed will may lead to both increased organ donation rates and family relief. As the presented data are – to the best of our knowledge – the only currently available data for Switzerland, we speculate that an opt-out policy on organ donation would affect donation rates [17, 18].

Our study has important limitations that deserve discussion. First, the retrieval rate of the (not formally validated) questionnaire was 66%, which might impose a bias on our findings. Also, the group consenting to organ donation taking part in the survey was larger than the group refusing organ donation. Second, the study was performed in two academic centres and had an observational design, with all the inherent limitations driven by study design. Centre-specific differences in procedures and the proportions of participants might impact on our results. However, the questionnaire might be adopted by additional centres, enabling future multicentre comparisons. Also, excluding next of kin confronted with donation after cardiac death might be problematic, as the proportion of such donors in Switzerland increased in recent years and comparison with donation after brain death may be difficult. Third, and importantly, we deliberately designed the analysis in an anonymised fashion to provide participants with the highest level of data protection. However, this prevented us from drawing conclusions on exact patient-related factors, such as age, ethnicity or underlying pathologies leading to brain death. This was considered out of the scope of the current analysis and might be pursued in subsequent studies.

In this observational study including the primary next of kin of deceased individuals who qualified for potential organ donation, the majority stated that addressing the question of organ donation did not impact the mourning process. Furthermore, we identified potential intra-hospital organisational aspects such as waiting time that might affect the final decision. Finally, the next of kin judged that existence of a presumed will would have facilitated grief and might have provided help for families confronted with a request for organ donation.

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files in the appendix in the PDF version of the manuscript.

The following files are included in the PDF version of this article:

Supplementary file 1: Table providing all responses to the questionnaire.

Supplementary file 2: Questionnaire in English.

Supplementary file 3: Questionnaire in German.

Supplementary file 4: Questionnaire in French.

We are indebted to all ICU staff for their dedicated care for patients and the next of kininvolved in the process of end of life and potential organ donation. We furthermore thank Viviana Abati for her support as a psychologist during development of the questionnaire.

MN, AB, and JCS (full institutional disclosure) report grants from Orion Pharma, Abbott Nutrition International, B. Braun Medical AG, CSEM AG, Edwards Lifesciences Services GmbH, Kenta Biotech Ltd, Maquet Critical Care AB, Omnicare Clinical Research AG, Nestle, Pierre Fabre Pharma AG, Pfizer, Bard Medica S.A., Abbott AG, Anandic Medical Systems, Pan Gas AG Healthcare, Bracco, Hamilton Medical AG, Fresenius Kabi, Getinge Group Maquet AG, Dräger AG, Teleflex Medical GmbH, Glaxo Smith Kline, Merck Sharp and Dohme AG, Eli Lilly and Company, Baxter, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, CSL Behring, Novartis, Covidien, Philips Medical, Prolong Pharmaceuticals, Phagenesis Ltd. and Nycomed outside of the submitted work. The money went into departmental funds. No personal financial gain applied. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

1 Kittleson MM , Kobashigawa JA . Cardiac Transplantation: Current Outcomes and Contemporary Controversies. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5(12):857–68. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2017.08.021

2 Black CK , Termanini KM , Aguirre O , Hawksworth JS , Sosin M . Solid organ transplantation in the 21st century. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6(20):409. doi:.https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2018.09.68

3BAG. Federal Act on the Transplantation of Organs, Tissues and Cells [Internet]. 2017; [cited 2018 Dec 20] Available from https://www.admin.ch/opc/en/classified-compilation/20010918/index.html

4 Weiss J , Coslovsky M , Keel I , Immer FF , Jüni P ; Comité National du Don d’Organes. Organ donation in Switzerland--an analysis of factors associated with consent rate. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e106845. Published online September 11, 2014. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106845

5Federal Department of Health: Numbers and facts on transplantation medicine [Internet]. 2018; [cited 2019 Dec 31] Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/zahlen-und-statistiken/zahlen-fakten-zu-transplantationsmedizin.html

6IRODaT Database [cited 2019 Dec 31] Available from: www.irodat.org.

7 Weiss JH , Keel I , Immer FF , Wiegand J , Haberthür C , Comité N ; Comité National du Don d’Organes (CNDO). Swiss Monitoring of Potential Organ Donors (SwissPOD): a prospective 12-month cohort study of all adult ICU deaths in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2014;144:w14045. doi:.https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2014.14045

8 Weiss J , Shaw D , Schober R , Abati V , Immer FF ; Comité National du Don d’Organes Cndo. Attitudes towards organ donation and relation to wish to donate posthumously. Swiss Med Wkly. 2017;147:w14401. doi:.https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2017.14401

9Swisstransplant: SwissPOD Reporting [Internet]. 2018; [cited 2018 Dec 20] Available from: https://www.swisstransplant.org/de/infos-material/statistiken/swisspod-reporting/

10 Berntzen H , Bjørk IT . Experiences of donor families after consenting to organ donation: a qualitative study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2014;30(5):266–74. Published online May 13, 2014. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2014.03.001

11 Birtan D , Arslantas MK , Dincer PC , Altun GT , Bilgili B , Ucar FB , et al. Effect of Interviews Done by Intensive Care Physicians on Organ Donation. Transplant Proc. 2017;49(3):396–8. Published online March 28, 2017. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2017.01.030

12 Lloyd-Williams M , Morton J , Peters S . The end-of-life care experiences of relatives of brain dead intensive care patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(4):659–64. Published online September 16, 2008. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.04.013

13 de Moraes EL , Dos Santos MJ , de Barros E Silva LB , de Lima Pilan LAS , de Lima EAA , de Santana AC , et al. Family Interview to Enable Donation of Organs for Transplantation: Evidence-based Practice. Transplant Proc. 2018;50(3):705–10. Published online March 25, 2018. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2018.02.056

14 Simpkin AL , Robertson LC , Barber VS , Young JD . Modifiable factors influencing relatives’ decision to offer organ donation: systematic review. BMJ. 2009;338(apr21 2):b991. Published online April 23, 2009. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b991

15 Franz HG , DeJong W , Wolfe SM , Nathan H , Payne D , Reitsma W , et al. Explaining brain death: a critical feature of the donation process. J Transpl Coord. 1997;7(1):14–21. doi:.https://doi.org/10.7182/prtr.1.7.1.287241p35jq7885n

16 Siminoff LA , Burant C , Youngner SJ . Death and organ procurement: public beliefs and attitudes. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2004;14(3):217–34. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1353/ken.2004.0034

17 Shepherd L , O’Carroll RE , Ferguson E . An international comparison of deceased and living organ donation/transplant rates in opt-in and opt-out systems: a panel study. BMC Med. 2014;12(1):131. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0131-4

18 Willis BH , Quigley M . Opt-out organ donation: on evidence and public policy. J R Soc Med. 2014;107(2):56–60. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076813507707

Equally contributing first authors

MN, AB, and JCS (full institutional disclosure) report grants from Orion Pharma, Abbott Nutrition International, B. Braun Medical AG, CSEM AG, Edwards Lifesciences Services GmbH, Kenta Biotech Ltd, Maquet Critical Care AB, Omnicare Clinical Research AG, Nestle, Pierre Fabre Pharma AG, Pfizer, Bard Medica S.A., Abbott AG, Anandic Medical Systems, Pan Gas AG Healthcare, Bracco, Hamilton Medical AG, Fresenius Kabi, Getinge Group Maquet AG, Dräger AG, Teleflex Medical GmbH, Glaxo Smith Kline, Merck Sharp and Dohme AG, Eli Lilly and Company, Baxter, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, CSL Behring, Novartis, Covidien, Philips Medical, Prolong Pharmaceuticals, Phagenesis Ltd. and Nycomed outside of the submitted work. The money went into departmental funds. No personal financial gain applied. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.